Abstract

Background:

Today, bariatric surgeons face the challenge of treating older adults with class III obesity. The indications and outcomes of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) versus sleeve gastrectomy (SG) also constitute a controversy.

Methods:

PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus were searched to retrieve systematic reviews/meta-analyses published by 1 March 2022. The selected articles were qualitatively evaluated using A Measurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR).

Results:

An umbrella review included six meta-analyses retrieved from the literature. The risk of early-emerging and late-emerging complications decreased by 55% and 41% in the patients underwent SG than in those receiving RYGB, respectively. The chance of the remission of hypertension and obstructive sleep apnoea, respectively increased by 43% and 6%, but type-2 diabetes mellitus decreased by 4% in the patients underwent RYGB than in those receiving SG. RYGB also increased excess weight loss by 15.23% in the patients underwent RYGB than in those receiving SG.

Conclusion:

Lower levels of mortality and early-emerging and late-emerging complications were observed in the older adults undergoing SG than in those receiving RYGB, which was, however, more efficient in term of weight loss outcomes and recurrence of obesity-related diseases

Keywords: bariatric surgery, obesity, older adults, Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, umbrella review

Introduction

Highlights

Complications were more in the older adults undergoing sleeve gastrectomy than Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB).

RYGB was more efficient in term of weight loss outcomes in older adults.

RYGB reduced the risk of remission of type-2 diabetes mellitus.

The social burden of severe obesity in older adults turns heavier1–3 with the globally-growing prevalence of obesity with age4–7.

Aging coupled with lack of exercise is associated with overall poor health through gradually lowering muscle proteins, increasing visceral fat and resistance to insulin, and causing atherosclerosis, nutritional deficiency, cognitive decline and frailty. Bariatric and metabolic surgeries (BMS) appear the most promising solution to the comorbidities inflicted upon different age groups, especially geriatric populations with class III obesity8.

Over the past decade, the frequency of BMS in older adults has increased by three-fold to 10% of the total bariatric procedures performed annually9,10. Bariatric surgeons face the challenge of treating class III obesity, especially in older adults11,12.

Although sleeve gastrectomy (SG) is the most common BMS around the world13, there is no consensus on SG, as the first choice in elderly patients with severe obesity.

Both Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and SG with low risk for complications can decrease weight, treat obesity-associated disorders and improve quality of life14, even in older adults15. Nevertheless, differences between SG and RYGB in terms of middle- and long-term postoperative outcomes have yet to be elucidated in this age group16. There are some concerns about BMS in this population and the outcomes are still debated17 and there is a lack of studies due to issues in this age group compared to the younger adults.

Research suggests a higher mortality caused by BMS and fewer benefits such as weight loss in older adults compared to the young18–20. Systematic reviews of pooled analyses, however, reported low rates of mortality and complications and successful weight loss outcomes in patients older than 60–65 years21,22. Given the concern over the indications and outcomes of RYGB in older adults with class III obesity, comparative analyses are required to be conducted using other procedures in different age groups23,24.

The meta-analyses so far conducted to compare RYGB with SG8,25,26 have failed to determine definitive guidelines and optimal procedures for comparing the two methods in terms of safety and efficacy in older adults. The present umbrella review and meta-analysis was conducted to systematically evaluate the context and quality of relevant articles and compare SG with RYGB in terms of safety, weight loss and obesity-associated disorders in aged patients requiring bariatric surgery.

Materials and methods

This umbrella review was performed according to the guidelines stipulated by the Joanna Briggs Institute27. This work has been reported in line with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and Assessing the methodological quality of systematic reviews (AMSTAR) Guidelines28. The study protocol was registered at the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). In addition, this review was registered in Research Registry UIN.

Search strategy

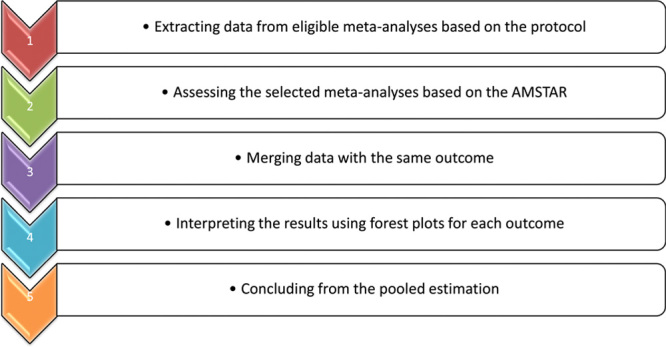

The keywords used to search in the titles and abstracts of the systematic reviews/meta-analyses published by 1 March 2022 in PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus comprised “severe obesity”, “obesity surgery”, “sleeve gastrectomy”, “bariatric surgery”, “Roux-en Y Gastric Bypass”, “older adults”, “meta-analysis” and their combination. The bibliography of all the selected articles was hand searched to find the eligible articles. After removing duplicate articles, qualitatively evaluating the remaining ones by two of the reviewers yielded an AMSTAR score of at least 1029 (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the umberella review.

Table 1.

AMSTAR score for included meta-analyses.

| AMSTAR Items | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Uses elements of PICO | A priori research design | Explained selection of the study designs | Comprehensive literature search | Study selection in duplicate | Dual data extraction | Excluded study list provided | Included studies described | Funding sources reported | Quality assessed | Quality used appropriately | Satisfactory discussion of heterogeneity | Conflicts of interest reported | AMSTAR score |

| Giordano et al.31 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Giordano et al.32 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 10 |

| Marczuk et al.26 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Shenoy et al.33 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 |

| Chenxin Xu et al.12 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 |

| Vallois et al.34 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11 |

PICO, Population, intervention, comparison, outcome.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the umberella review.

Statistical analysis

The pooled odds ratios (ORs) of the outcomes of bariatric surgeries, that is RYGB and SG, were considered the main measure of the effect/effect size. Cochrane’s Q test and I2 used to compare the articles respectively showed a significant heterogeneity in the meta-analyses and heterogeneity of 0–100%. The random-effects model was used to estimate the dichotomous outcome and pooled ORs as the main index at a 95% CI. The mean difference (MD) was also used to obtain excess weight loss (EWL) based on the DerSimonian-Laird approach. A forest plot was employed to present the pooled ORs of the outcomes of RYGB and SG and Begg’s test to assess publication bias. The number of articles being below 10 made meta-regression and funnel plots inapplicable to publication bias assessments30. The data were analyzed in Stats13 by reporting only the mean quantitative variables. The umbrella review was performed through weighting each study by their sample size.

Data extraction

The data independently extracted from the articles by two reviewers included author names, year of publication, number of primary studies, sample size, early complications, late morbidity, total complications, mortality, early readmission, reoperation, total weight loss, EWL, obstructive sleep apnoea, hypertension and type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). A third investigator independently resolved potential conflicts between the findings of the two reviewers (Tables 2, 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies included in umbrella meta-analysis.

| First Author and subject | Year | No. primary studies | Sample size | Perioperative morbidity (early complications) (95% CI) | Late morbidity (95% CI) | Total complication (95% confidence interval) | Mortality (95% CI) | early readmission (95% CI) | Reoperation (95% CI) | %TWL (95% CI) | %EWL (95% CI) | OSA (95% CI) | HTN (95% CI) | T2DM(95% CI) | DLP (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shenoy (SG vs. RYGB on young vs. elderly)33 | 2020 | 9 | 2240 | 0.71 [0.44, 1.13] | 0.35 [0.19, 0.65] | — | 0.50 [0.15–1.70] | — | — | — | 7.79 [−23.96, 8.38] | 1.14 [0.55, 2.34] | 0.57 [0.35, 0.93] | 1.02 [0.63, 1.66] | — | |

| Chenxin Xu(RYGB vs. SG on Young vs. Elderly)12 | 2020 | 19 | 31941 | 1.75 [1.51, 2.04] | 1.63 [1.41, 1.88] | — | early: 2.23 [1.37–3.64],Late:1.22 [0.18, 8.06] | 1.75 [1.48–2.06] | 2.16 [1.67–2.81] | 2 year 6.26 [−1.33, 13.85], 3 year 4.97 [−2.34, 12.27] | 1 year 19.55 [14.65, 24.46], 2 year 16.56 [0.05, 33.08] | 1.31 [0.60, 2.81] | 1.73 [1.02, 2.93] | 0.89 [0.37–2.13] | — | |

| Giordano (SG on elderly vs. younger)32 | 2020 | 11 | 2259 | — | — | 1.71 [0.76, 3.83] | — | — | — | — | is −7.63 [−13.19, −2.08] | 0.81 [0.69, 0.95] | — | — | — | |

| Giordano (RYGB on elderly vs. younger)31 | 2018 | 7 | 3128 | — | — | 1.51 [1.07–2.11] | 6.12 [1.08–34.43] | — | — | — | is -3.44 [−5.20 to 1.68] i2:0, p:0.77 | — | 1 year 0.57 [0.42, 0.76] | — | 1 year 0.61 [0.45, 0.83] | |

| Marczuk (RYGB on elderly vs. younger)26 | 2019 | 9 | 4391 | — | — | 1.88 [1.07, 3.30] | 4.38 [1.25, 15.31] | — | — | is -5.86 [−9.15, −2.56] | — | 0.33 [0.14–0.74] | 0.64 [0.42, 0.97] | — | ||

| Vallois34 | RYGB on elderly vs. younger | 2020 | 11 | 6638 | — | — | 1.70 [0.98, 2.94] | — | — | — | — | 1 year is −5.28 [−7.49, −3.07] | 0.97 [0.58, 1.65] | 0.42 [0.06, 2.89] | 0.51 [0.30, 0.87] | — |

| SG on elderly vs. younger | 2020 | 9 | 26,118 | — | — | 1.49 [1.28, 1.75] | — | — | — | — | 1 year is −4.49 [−6.98, −2.01] | 3.36 [0.58, 19.43] | 1.13 [0.74, 1.74] | 1.69 [0.79, 3.61] | 1.37 [0.85, 2.19] | |

EWL, excess weight loss; HTN, hypertension; SG, sleeve gastrectomy; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; T2DM, type-2 diabetes mellitus.

TWL, total weight loss; DLP, dyslipidemia; OSA, Obstructive sleep apnea.

Table 3.

Tabular representation of the reported outcomes of the meta-analyses.

| Outcome | Meta-analysis | Studies | Patients | ES | 95% lower CI | 95% upper CI | I2, % | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early complications | Shenoy et al.33 | 9 | 2240 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 1.13 | 38 | 0.012 |

| Chenxin Xu et al.12 | 19 | 31 941 | 1.75 | 1.51 | 2.04 | 0 | 0.69 | |

| Late complication | Shenoy et al.33 | 9 | 2240 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.65 | 0 | 0.46 |

| Chenxin Xu et al.12 | 19 | 31 941 | 1.63 | 1.41 | 1.88 | 0 | 0.48 | |

| Total complication | Vallois et al.34 for RYGB | 11 | 6638 | 1.70 | 0.98 | 2.94 | 76 | 0.001 |

| Vallois et al.34 for SG | 9 | 26 118 | 1.49 | 1.28 | 1.75 | 48 | 0.04 | |

| Giordano et al.32 | 11 | 2259 | 1.71 | 0.76 | 3.83 | 83 | <0.001 | |

| Giordano et al.31 | 7 | 3128 | 1.51 | 1.07 | 2.11 | 0 | 0.99 | |

| Marczuk et al.26 | 9 | 4391 | 1.88 | 1.07 | 3.30 | 50 | 0.05 | |

| Mortality | Shenoy et al.33 | 9 | 2240 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 1.70 | 0 | 0.45 |

| Chenxin Xu et al.12 | 19 | 31 941 | Early: 2.23; late: 1.22 | Early: 1.37; late: 0.18 | Early: 3.64; late: 8.06 | Early: 37; late: 56 | Early: 0.19; late: 0.10 | |

| Giordano et al.31 | 7 | 3128 | 6.12 | 1.08 | 34.43 | 44 | 0.13 | |

| Marczuk et al.26 | 9 | 4391 | 4.38 | 1.25 | 15.31 | 18 | 0.3 | |

| Early readmission | Chenxin Xu et al.12 | 19 | 31 941 | 1.75 | 1.48 | 2.06 | 0 | 0.53 |

| Reoperation | Chenxin Xu et al.12 | 19 | 31 941 | 2.16 | 1.67 | 2.81 | 12 | 0.34 |

| %TWL | Chenxin Xu et al.12 | 19 | 31 941 | 2 years: 6.26; 3 years: 4.97 | 2 years: −1.33; 3 years: 13.85 | 2 years: 2.34; 3 years: 12.27 | 2 years: 80; 3 years: 95 | 2 years: 0.03; 3 years: <0.001 |

| %EWL | Shenoy et al.33 | 9 | 2240 | 7.79 | −23.96 | 8.38 | 90 | <0.001 |

| Chenxin Xu et al.12 | 19 | 31 941 | 1 year 19.55; 2 years: 16.56 | 1 year 14.65; 2 years: 0.05 | 1 year 24.46; 2 years: 33.08 | Early: 28; late: 80 | Early: 0.24; late: 0.02 | |

| Giordano et al.32 | 11 | 2259 | −7.63 | −13.19 | −2.08 | 84 | <0.001 | |

| Giordano et al.31 | 7 | 3128 | −3.44 | −5.20 | −1.68 | 0 | 0.87 | |

| Marczuk et al.26 | 9 | 4391 | −5.86 | −9.15 | −2.56 | 0 | 0.77 | |

| Vallois et al.34 for RYGB | 11 | 6638 | −5.28 | −7.49 | −3.07 | 0 | 0.71 | |

| Vallois et al.34 for SG | 9 | 26 118 | −4.49 | −6.98 | −2.01 | 0 | 0.74 | |

| DLP | Giordano et al.31 | 7 | 3128 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.83 | 0 | 0.54 |

| Vallois et al.34 for SG | 9 | 26 118 | 1.37 | 0.85 | 2.19 | 46 | 0.15 | |

| T2DM | Shenoy et al.33 | 9 | 2240 | 1.02 | 0.63 | 1.66 | 0 | 0.66 |

| Chenxin Xu et al.12 | 19 | 31 941 | 0.89 | 0.37 | 2.13 | 57 | 0.10 | |

| Marczuk et al.26 | 9 | 4391 | 0.64 | 0.42 | 0.97 | 0 | 0.54 | |

| Vallois et al.34 for RYGB | 11 | 6638 | 0.51 | 0.30 | 0.87 | — | — | |

| Vallois et al.34 for SG | 9 | 26,118 | 1.69 | 0.79 | 3.61 | 82 | <0.001 | |

| HTN | Shenoy et al.33 | 9 | 2240 | 0.57 | 0.35 | 0.93 | 0 | 0.58 |

| Chenxin Xu et al.12 | 19 | 31 941 | 1.73 | 1.02 | 2.93 | 0 | 0.38 | |

| Giordano et al.31 | 7 | 3128 | 0.57 | 0.42 | 0.76 | 42 | 0.14 | |

| Marczuk et al.26 | 9 | 4391 | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.74 | 61 | 0.08 | |

| Vallois et al.34 for RYGB | 11 | 6638 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 2.89 | — | — | |

| Vallois et al.34 for SG | 9 | 26 118 | 1.13 | 0.74 | 1.74 | 39 | 0.16 | |

| OSA | Shenoy et al.33 | 9 | 2240 | 1.14 | 0.55 | 2.34 | 0 | 0.70 |

| Chenxin Xu et al.12 | 19 | 31 941 | 1.31 | 0.60 | 2.81 | 0 | 0.56 | |

| Giordano et al.32 | 11 | 2259 | 0.81 | 0.69 | 0.95 | 0 | 0.96 | |

| Vallois et al.34 for RYGB | 11 | 6638 | 0.97 | 0.58 | 1.65 | 91 | <0.001 | |

| Vallois et al.34 for SG | 9 | 26 118 | 3.36 | 0.58 | 19.43 | — | — |

EWL, excess weight loss; HTN, hypertension; SG, sleeve gastrectomy; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; T2DM, type-2 diabetes mellitus.

TWL, total weight loss; DLP, dyslipidemia; OSA, Obstructive sleep apnea.

Results

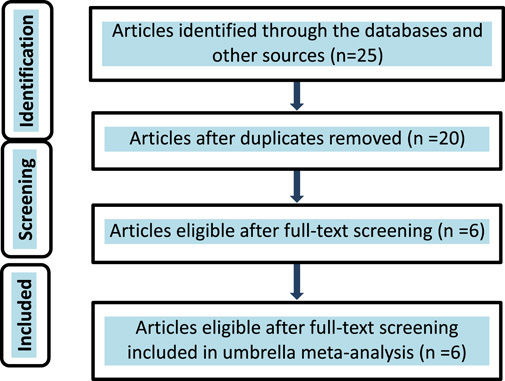

Twenty records were found from our literature search. Of these, 14 were excluded after full-text screening. Totally, we selected six meta-analyses to run umbrella meta-analysis (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

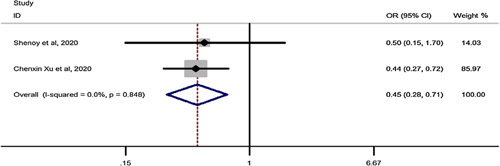

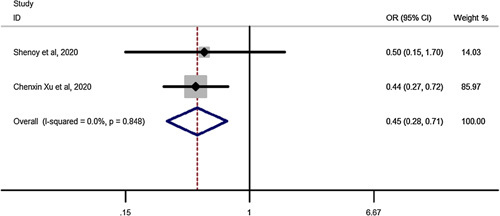

Early complications for SG vs. RYGB in elderly

Pooled estimation of a meta-analysis of odds ratio studies reported an OR of 0.45, that is in patients undergoing SG, the chance of early complications decrease by 55% (OR: 0.45, CI 95%: 0.28–0.71) compared to RYGB (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot to show risk of early complications for sleeve gastrectomy vs. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in elderly. OR, odds ratio; OSA, Obstructive sleep apnea.

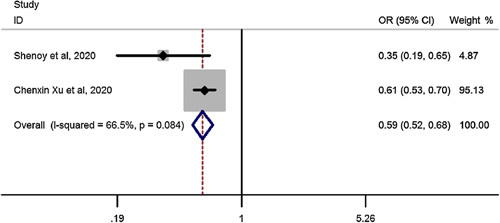

Late complications for SG vs. RYGB in elderly

Pooled estimation of a meta-analysis of odds ratio studies reported an OR of 0.59, meaning that in patients undergoing SG, the risk of late complications decreases by 41% (OR: 0.59, CI 95%: 0.52–0.68) compared to RYGB (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot to show risk of late complications for sleeve gastrectomy vs. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in elderly. OR, odds ratio.

Mortality for SG vs. RYGB in elderly

Pooled estimation of a meta-analysis of odds ratio studies reported an OR of 0.45, that is in patients undergoing SG, the chance of mortality decrease by 55% (OR: 0.45, CI 95%: 0.28–0.71) compared to RYGB (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot to show risk of mortality for sleeve gastrectomy vs. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in elderly. OR, odds ratio.

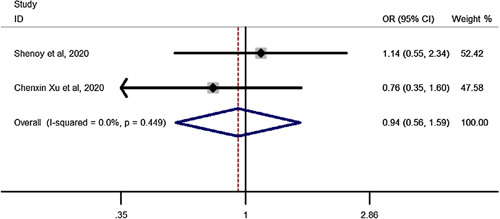

OSA remission after SG vs. RYGB in elderly

Pooled estimation of a meta-analysis of odds ratio studies reported an OR of 0.94, that is in patients undergoing SG, the chance of Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) remission decreases by 6% (OR: 0.94, CI 95%: 0.56–1.59) compared to RYGB but it was not significant showing no difference between SG and RYGB on OSA remission (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot to show chance of OSA remission for sleeve gastrectomy vs. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in elderly. OR, odds ratio.

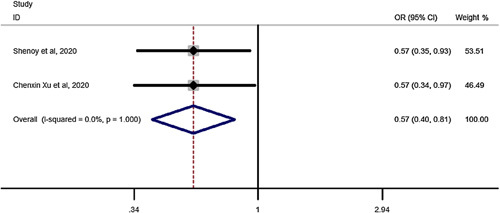

Hypertension (HTN) remission after SG vs. RYGB in elderly

Pooled estimation of a meta-analysis of odds ratio studies reported an OR of 0.57, that is in patients undergoing SG, the chance of HTN remission decreases by 43% (OR: 0.57, CI 95%: 0.40–0.81) compared to RYGB (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Forest plot to show chance of hypertension remission for sleeve gastrectomy vs. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in elderly. OR, odds ratio.

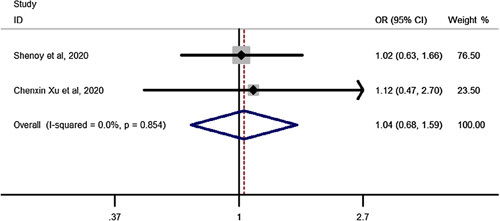

T2DM remission after SG vs. RYGB in elderly

Pooled estimation of a meta-analysis of odds ratio studies reported an OR of 1.04, that is in patients undergoing SG the chance of T2DM remission increases by 4% (OR: 1.04, CI 95%: 0.68–1.59) compared to RYGB but was not significant (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Forest plot to show chance of type-2 diabetes mellitus remission after sleeve gastrectomy vs. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in elderly. OR, odds ratio.

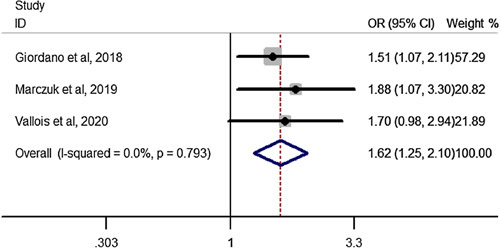

Total complications after RYGB in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years

Pooled estimation of a meta-analysis of odds ratio studies reported an OR of 1.62, that is in patients undergoing RYGB bariatric surgery, the chance of total complication increase by 62% (OR: 1.62, CI 95%: 1.25–2.10) in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years(Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Forest plot to show total complications after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years. OR, odds ratio.

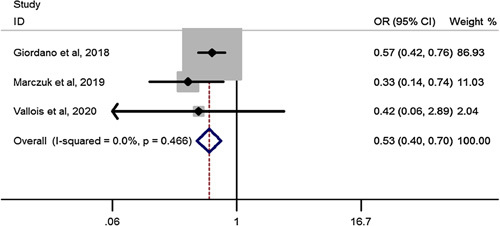

HTN remission after RYGB in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years

Pooled estimation of a meta-analysis of odds ratio studies reported an OR of 0.53, that is in patients undergoing RYGB bariatric surgery, the chance of HTN remission decrease by 47% (OR: .53, CI 95%: 0.40–0.70) in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years(Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Forest plot to show hypertension remission after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years. OR, odds ratio.

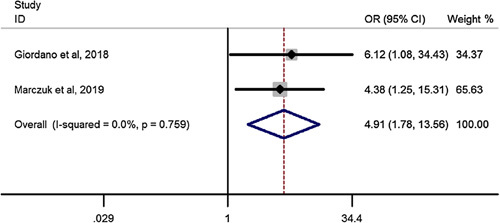

Mortality after RYGB in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years

Pooled estimation of a meta-analysis of odds ratio studies reported an OR of 4.91, that is in patients undergoing RYGB, the chance of mortality increases by 4.91 times (OR: 4.91, CI 95%: 1.78–13.56) in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Forest plot to show mortality after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years. OR, odds ratio.

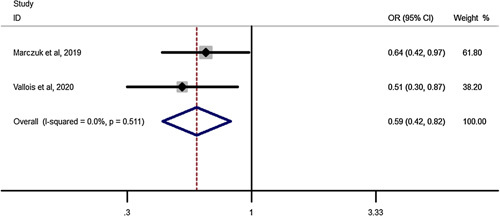

T2DM remission after RYGB in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years

Pooled estimation of a meta-analysis of odds ratio studies reported an OR of 0.59, that is in patients undergoing RYGB, the chance of T2DM remission decreases by 41% (OR: .59, CI 95%: 0.42–0.82) in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years(Fig. 12).

Figure 12.

Forest plot to show type-2 diabetes mellitus remission after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in elderly compared to Youngers than 60 years. OR, odds ratio.

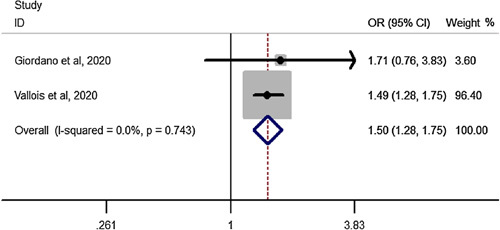

Total complications after SG in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years

Pooled estimation of a meta-analysis of odds ratio studies reported an OR of 1.5, that is in patients undergoing SG, the chance of total complications increase by 50% (OR: 1.50, CI 95%: 1.28–1.75) in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years (Fig. 13).

Figure 13.

Forest plot to show total complications after sleeve gastrectomy in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years. OR, odds ratio.

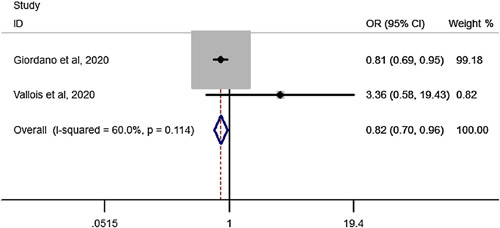

OSA remission after SG in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years

Pooled estimation of a meta-analysis of odds ratio studies reported an OR of .82, that is in patients undergoing SG, the chance of OSA remission decreases by 18% (OR: .82, CI 95%: 0.70–0.96) in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years (Fig. 14).

Figure 14.

Forest plot to show OSA remission after sleeve gastrectomy in elderly compared to youngers than 60 years. OR, odds ratio; OSA, Obstructive sleep apnea.

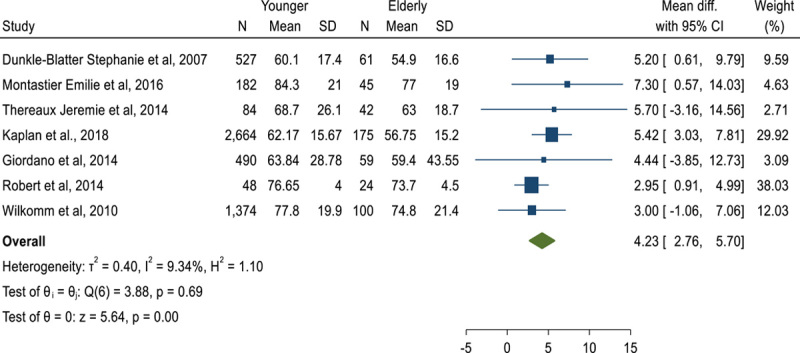

%EWL following RYGB in youngers than 60 years compared to elderly23,25,35,36,37,38,39

MD of %EWL after RYGB showed that youngers experience an extra 4.23%EWL compared to elderly people following RYGB (MD: 4.23, CI 95%: 2.76–5.70) (Fig. 15).

Figure 15.

Forest plot to show %excess weight loss mean difference following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in youngers than 60 years compared to elderly.

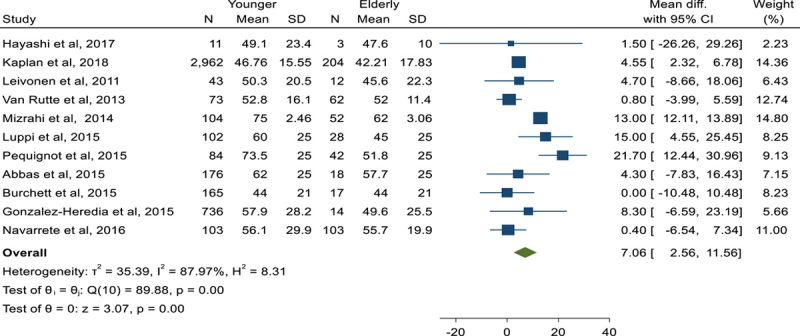

%EWL following SG in youngers than 60 years compared to elderly8,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48

MD of %EWL following SG showed that youngers experience an extra 7.06%EWL compared to elderly people following SG (MD: 7.06, CI 95%: 2.56–11.56) (Fig. 16).

Figure 16.

Forest plot to show %excess weight loss mean difference following sleeve gastrectomy in youngers than 60 years compared to elderly.

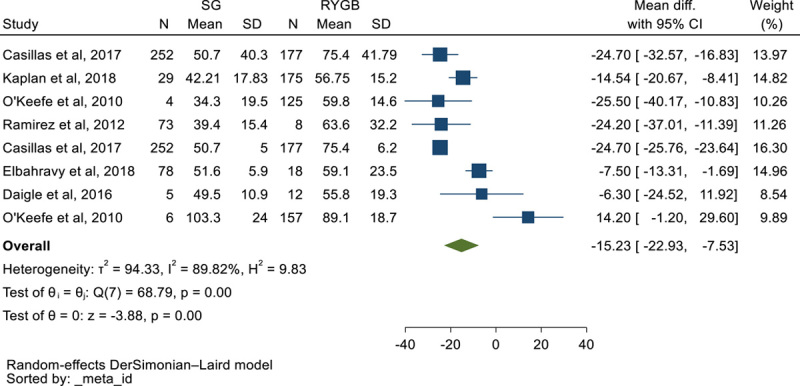

%EWL following SG vs. RYGB in elderly10,39,49,50,51,52

MD of %EWL following SG vs. RYGB, showed that the patients experience an extra 15.23%EWL following RYGB compared to SG (MD: −15.23, CI 95%: −22.93, −7.53), in other word SG leads to 15.23%EWL less than RYGB (Fig. 17) (Figure 18).

Figure 17.

Forest plot to show %excess weight loss mean difference in elderly following sleeve gastrectomy vs. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

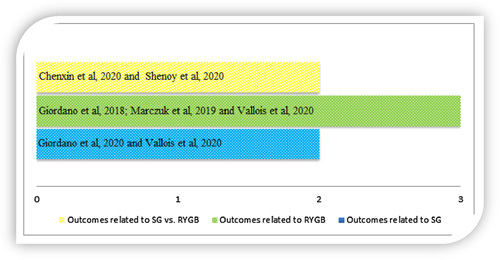

Figure 18.

List of meta-analyses reporting outcomes related to only sleeve gastrectomy (SG), only Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and comparing SG vs. RYGB.

Discussion

In the last decades life expectancy has significantly increased in the most developed countries, where the rates of obesity are also constantly growing53,54. Moreover, the diffusion of minimally invasive procedures and the improvement of perioperative anaesthetic management allowed to perform bariatric interventions in older patients.

For these reasons, there is currently a consistent body of literature proving that BMS can be safely and effectively performed in patients older than 60 years55. Some evidences seem to suggest that BMS has comparable results in younger and older patients56, while other studies have proved longer hospital stay and lower weight loss among patients older than 60 years57. Moreover, no consensus has been reached regarding the best procedure in terms of risks and outcomes.

SG is the most commonly performed procedure worldwide58, and a recent article has demonstrated that in older patients is as effective as in those younger than 60 years in terms of weight loss and improvement of comorbidities up to 5 years of follow-up59. Also, the meta-analysis of Giordano et al.32 has underlined the comparable results in terms of safety between older and younger patients, even if lower weight loss was recorded for the elderly ones.

On the other hand, a recent retrospective multi-institutional study from France showed that 90-day complication rate maybe higher for older patients undergoing RYGB when compared to younger ones3. Other articles did not find that older age was related to higher risks after RYGB but lower weight loss was demonstrated3.

A prospective trial3 has also evaluate 1-year outcomes of SG and RYGB in patients 65 years or older showing better weight loss after the RYGB. Currently, only one paper is available on one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) in this class of patients showing that the one anastomosis bypass can be a good choice because of its shorter operative time, higher efficacy and low complication rate60.

Serious morbidity following bariatric surgery is uncommon. Since laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is associated with less adverse 30-day outcomes in comparison to RYGB59 in younger patients similar outcomes could be expected in the elder population. Indeed, our analysis showed that SG significantly decreases the risk of early and late complications and mortality in patients older than 60 when compared to RYGB.

However, despite the vast body of literature on BMS in elder patients, there are conflicting reports on complications. While some studies have demonstrated that patients younger than 65 and older than or equal to 65 years had similar perioperative morbidity and mortality after bariatric surgery61, other articles17 have reported that elderly patients have higher 30-day odds of serious complications and 30-day mortality. The present umbrella study further demonstrates that SG and RYGB both have higher rates of complications and mortality in patients with older than 65 years. In light of these increased risks, it is noteworthy that SG decreases the percentage of late complications and death when compared to RYGB suggesting that restrictive surgery maybe more appropriate in this class of individuals.

Moreover, little evidence has been published in septuagenarians confirming slightly higher rates of postoperative complications compared with a younger population62,63. Considering these outcomes, updated guidelines on BMS64 concluded that there is no upper patient-age limit to BMS and those older individuals who could benefit from BMS should be considered for surgery after careful assessment of comorbidities and frailty.

In terms of metabolic outcomes, our umbrella research confirmed that both remissions from diabetes and weight loss were effective in patients older than 65 years, but younger patients had better results.

Longer duration of diabetes60 causes an irreversible loss of beta-cells. Thus, the metabolic mechanism of the RYGB is predictably less effective in the older age when compared to younger patients. Interestingly, only HTN was significantly improved after RYGB when compared to LSG in our study, while no different effect was noted on OSAS and TD2M.

Several studies17,61 have clearly demonstrated that the RYGB provides better short and long-term weight loss than the LSG and this finding was also confirmed for older patients by our umbrella analysis.

Weight loss and maintenance is undoubtedly related to a regular physical activity after BMS62,63 and older individuals tend to experience early fatigue and to exercise less regularly than younger patients. However, all the available evidence and our meta-analysis show that BMS is still effective even if it induces lower %EWL results in the elderly population when compared to subjects younger than 60 years.

Although this evidence needs to be confirmed by prospective trials and have been partially previously reported by previous single studies and meta-analysis, to the best of our knowledge, we performed the first umbrella meta-analysis on this topic. The umbrella construction allows drawing an overall conclusion over conflicting results of previous meta-analyses.

The updated findings of this study provide insights into the current state of the literature, based on a total of 75 elderly patients included. A major constraint of this study is that the weight loss outcomes and remission of comorbidities may have been influenced by the varying operative techniques used for both RYGB and SG. For instance, research has demonstrated that creation a longer length of the biliopancreatic loop during RYGB can result in greater weight loss and a higher likelihood of remission from obesity-related medical problems65. Another limitation was that only three out of the six included meta-analyses had investigated the effect of both LSG and RYGB on elderly patients. Moreover, not all the outcome measures were studied in the included papers, therefore all the forest plots include a number of studies less than or equal to 3, and 10 of them include only 2 articles. Subsequently, despite the overall large sample size provided by the “umbrella meta-analysis”, the results of this paper mainly rely on the outcomes of 3 previous meta-analyses.

Conclusion

This umbrella meta-analysis aims to settle different results of previous single meta-analysis on MSB in patients older than 60 years. Our outcomes suggest that BMS provides satisfactory outcomes in patients older than 60 years but with higher risks of complications. In the elderly population, SG is a safer surgical option than RYGB, which on the contrary induces better weight loss and remission of HTN.

Ethical approval

No applicable (review of the literature).

Source of funding

None.

Author contribution

M.K.: conceived the idea for the topic, data gathering, consulting and writing. M.M.: consulting and reviewing. R.V.: statistics and methodology. S.S.S.: data gathering, consulting and reviewing. A.V.: data gathering, consulting and reviewing. M.M. and R.V.: organization leadership, data gathering, consulting and writing.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

None.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Name of the registry: Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO).

Unique Identifying number or registration ID: CRD42022318906.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): CRD42022318906 (Available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=318906) Dear colleague: The above mentioned link can be checked, it is correct but maybe due to the policy of the PROSPERO it cannot be hyperlinked, please check it, maybe you can slove it, thanks a lot.

Guarantor

Rohollah Valizadeh and Mario Musella.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Data availability statement

All authors declare that data of this meta-analysis were retrieved from published literature where they are available.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that maybe relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Published online 4 October 2023

Contributor Information

Mohammad Kermansaravi, Email: mkermansaravi@yahoo.com.

Antonio Vitiello, Email: antoniovitiello_@hotmail.it.

Rohollah Valizadeh, Email: rohvali4@gmail.com.

Shahab Shahabi Shahmiri, Email: shshahabi@yahoo.com.

Mario Musella, Email: mario.musella@unina.it.

References

- 1.Gomez-Cabello A, Pedrero-Chamizo R, Olivares PR, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in non-institutionalized people aged 65 or over from Spain: the elderly EXERNET multi-centre study. Obes Rev 2011;12:583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jésus P, Guerchet M, Pilleron S, et al. Undernutrition and obesity among elderly people living in two cities of developing countries: prevalence and associated factors in the EDAC study. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2017;21:40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pajecki D, Dantas ACB, Tustumi F, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in the elderly: 1-year preliminary outcomes in a randomized trial (BASE Trial). Obes Surg 2021;31:2359–2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloom D, Canning D, Fink G. Implications of population ageing for economic growth. Oxford Rev Econ Policy 2010;26:583–612. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lutz W, Sanderson W, Scherbov S. The coming acceleration of global population ageing. Nature 2008;451:716–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agha M, Agha R. The rising prevalence of obesity: part A: impact on public health. Int Jf Surg Oncol 2017;2:e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, et al. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA 2012;307:491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbas M, Cumella L, Zhang Y, et al. Outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in patients older than 60. Obes Surg 2015;25:2251–2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gebhart A, Young MT, Nguyen NT. Bariatric surgery in the elderly: 2009-2013. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015;11:393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elbahrawy A, Bougie A, Loiselle SE, et al. Medium to long-term outcomes of bariatric surgery in older adults with super obesity. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric. Surgery 2018;14:470–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathus-Vliegen EM. Obesity and the elderly. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012;46:533–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu C, Yan T, Liu H, et al. Comparative safety and effectiveness of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy in obese elder patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2020;30:3408–3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kermansaravi M, Parmar C, Chiappetta S, et al. Best practice approach for redo-surgeries after sleeve gastrectomy, an expert’s modified Delphi consensus. Surg Endosc 2023;37:1617–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1567–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterli R, Borbély Y, Kern B, et al. Early results of the Swiss Multicentre Bypass or Sleeve Study (SM-BOSS): a prospective randomized trial comparing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Ann Surg 2013;258:690–694; discussion 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pajecki D, Dantas ACB, Kanaji AL, et al. Bariatric surgery in the elderly: a randomized prospective study comparing safety of sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (BASE Trial). Surg Obes Relat Dis 2020;16:1436–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albacete S, Verhoeff K, Mocanu V, et al. A 5-year characterization of trends and outcomes in elderly patients undergoing elective bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc 2023;37:5397–5404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Contreras JE, Santander C, Court I, et al. Correlation between age and weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2013;23:1286–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scozzari G, Passera R, Benvenga R, et al. Age as a long-term prognostic factor in bariatric surgery. Ann Surg 2012;256:724–728; discussion 8-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giordano S, Victorzon M. Laparoscopic Roux-En-Y gastric bypass in elderly patients (60 years or older): a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Scand J Surgery 2017;107:6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giordano S, Victorzon M. Bariatric surgery in elderly patients: a systematic review. Clin Intervent Aging 2015;10:1627–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch J, Belgaumkar A. Bariatric surgery is effective and safe in patients over 55: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2012;22:1507–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giordano S, Victorzon M. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is effective and safe in over 55-year-old patients: a comparative analysis. World J Surg 2014;38:1121–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chow A, Switzer NJ, Gill RS, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in the elderly: a systematic review. Obes Surg 2016;26:626–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robert M, Pasquer A, Espalieu P, et al. Gastric bypass for obesity in the elderly: is it as appropriate as for young and middle-aged populations? Obes Surg 2014;24:1662–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marczuk P, Kubisa MJ, Święch M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in elderly patients-systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2019;29:361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, et al. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthcare 2015;13:132–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clin Res ed) 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clin Res ed) 2017;358:j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page MJ, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews of biomedical research: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giordano S, Victorzon M. Laparoscopic Roux-En-Y gastric bypass in elderly patients (60 years or older): a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Scand J Surg 2018;107:6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giordano S, Salminen P. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is safe for patients over 60 years of age: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech Part A 2020;30:12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shenoy SS, Gilliam A, Mehanna A, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in elderly bariatric patients: safety and efficacy-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2020;30:4467–4473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vallois A, Menahem B, Alves A. Is laparoscopic bariatric surgery safe and effective in patients over 60 years of age? An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2020;30:5059–5070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willkomm CM, Fisher TL, Barnes GS, et al. Surgical weight loss >65 years old: is it worth the risk? Surg Obes Relat Dis 2010;6:491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thereaux J, Poitou C, Barsamian C, et al. Midterm outcomes of gastric bypass for elderly (aged ≥ 60 yr) patients: a comparative study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015;11:836–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montastier E, Becouarn G, Bérard E, et al. Gastric bypass in older patients: complications, weight loss, and resolution of comorbidities at 2 years in a matched controlled study. Obes Surg 2016;26:1806–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunkle-Blatter SE, St, Jean MR, Whitehead C, et al. Outcomes among elderly bariatric patients at a high-volume center. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2007;3:163–169; discussion 9-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaplan U, Penner S, Farrokhyar F, et al. Bariatric surgery in the elderly is associated with similar surgical risks and significant long-term health benefits. Obes Surg 2018;28:2165–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayashi A, Maeda Y, Takemoto M, et al. Outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in elderly obese Japanese patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2017;17:2068–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luppi CR, Balagué C, Targarona EM, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in patients over 60 years: impact of age on weight loss and co-morbidity improvement. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015;11:296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pequignot A, Prevot F, Dhahri A, et al. Is sleeve gastrectomy still contraindicated for patients aged≥60 years? A case-matched study with 24 months of follow-up. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric. Surgery 2015;11:1008–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leivonen MK, Juuti A, Jaser N, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in patients over 59 years: early recovery and 12-month follow-up. Obes Surg 2011;21:1180–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mizrahi I, Alkurd A, Ghanem M, et al. Outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in patients older than 60 years. Obes Surg 2014;24:855–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Rutte PW, Smulders JF, de Zoete JP, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy in older obese patients. Surg Endosc 2013;27:2014–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burchett MA, McKenna DT, Selzer DJ, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is safe and effective in elderly patients: a comparative analysis. Obes Surg 2015;25:222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzalez-Heredia R, Patel N, Sanchez-Johnsen L, et al. Does Age Influence Bariatric Surgery Outcomes? Bariatr Surg Pract Patient Care 2015;10:74–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Navarrete A, Corcelles R, Del Gobbo GD, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy in the elderly: a case-control study with long-term follow-up of 3 years. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2017;13:575–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casillas RA, Kim B, Fischer H, et al. Comparative effectiveness of sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for weight loss and safety outcomes in older adults. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2017;13:1476–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Keefe KL, Kemmeter PR, Kemmeter KD. Bariatric surgery outcomes in patients aged 65 years and older at an American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Center of Excellence. Obesity surgery 2010;20:1199–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daigle CR, Andalib A, Corcelles R, et al. Bariatric and metabolic outcomes in the super-obese elderly. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2016;12:132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramirez A, Roy M, Hidalgo JE, et al. Outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients >70 years old. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric. Surgery 2012;8:458–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sabayan B, Bonneux L. Dementia in Iran: how soon it becomes late! Arch Iran Med.2011;14:290–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jahn H. Memory loss in Alzheimer's disease. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2013;15:445–54. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arolfo S, Salzano A, Dogliotti S, et al. Bariatric surgery in over 60 years old patients: is it worth it?. Updat Surg 2021;73:1501–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Molero J, Olbeyra R, Vidal J, et al. A propensity score cohort study on the long-term safety and efficacy of sleeve gastrectomy in patients older than age 60. J Obes 2020;2020:8783260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Athanasiadis DI, Hernandez E, Monfared S, et al. Bariatric surgery outcomes: is age just a number? Surg Endosc 2021;35:3139–3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. Erratum to: bariatric surgery and endoluminal procedures: IFSO Worldwide Survey 2014. Obes Surg 2017;27:2290–2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fernández-Ananín S, Ballester E, Gonzalo B, et al. Is sleeve gastrectomy as effective in older patients as in younger patients? A comparative analysis of weight loss, related comorbidities, and medication requirements. Obes Surg 2022;32:1909–1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gholizadeh B, Makhsosi BR, Valizadeh R, et al. Safety and efficacy of one anastomosis gastric bypass on patients with severe obesity aged 65 years and above. Obes Surg 2022;32:1610–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iranmanesh P, Boudreau V, Ramji K, et al. Outcomes of bariatric surgery in elderly patients: a registry-based cohort study with 3-year follow-up. Int J Obes 2022;46:574–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Al-Kurd A, Grinbaum R, Mordechay-Heyn T, et al. Outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy in septuagenarians. Obes Surg 2018;28:3895–3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith ME, Bacal D, Bonham AJ, et al. Perioperative and 1-year outcomes of bariatric surgery in septuagenarians: implications for patient selection. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2019;15:1805–1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eisenberg D, Shikora SA, Aarts E, et al. 2022. American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg 2023; 33:3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kermansaravi M, Davarpanah Jazi AH, Shahabi Shahmiri S, et al. Revision procedures after initial Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, treatment of weight regain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Updat Surg 2021;73:663–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All authors declare that data of this meta-analysis were retrieved from published literature where they are available.