Abstract

Purpose of Review

Many factors influence disease management and glycemic levels in children with type 1 diabetes (T1D). However, these concepts are hard to examine in children using only a qualitative or quantitative research paradigm. Mixed methods research (MMR) offers creative and unique ways to study complex research questions in children and their families.

Recent Findings

A focused, methodological literature review revealed 20 empirical mixed methods research (MMR) studies that included children with T1D and/or their parents/caregivers. These studies were examined and synthesized to elicit themes and trends in MMR. Main themes that emerged included disease management, evaluation of interventions, and support. There were multiple inconsistencies between studies when reporting MMR definitions, rationales, and design.

Summary

Limited studies use MMR approaches to examine concepts related to children with T1D. Findings from future MMR studies, especially ones that use child-report, may illuminate ways to improve disease management and lead to better glycemic levels and health outcomes.

Keywords: Type 1 diabetes, Mixed methods research, Children, Diabetes management, Socio-ecological framework

Introduction

Many children with type 1 diabetes (T1D) have difficulty achieving and maintaining glycemic targets despite intensive insulin therapy [1–3]. This challenge may be related to other factors that influence glycemic levels, such as nuances in daily management, which is a challenging concept to study, given variations in individual treatment regimens and daily fluctuations in diabetes care. MMR approaches may help researchers and clinicians better understand nuances in daily management by using both quantitative data, such as glycemic levels, and qualitative methods, such as interviews and focus groups, to elicit child and parent perceptions of living with diabetes. Furthermore, MMR provides a more holistic picture of the daily management of T1D in children.

Mixed methods research (MMR) strategies offer unique solutions to understand complex research questions. MMR is the collection, analysis, and integration of qualitative and quantitative strands of data in a single study to produce inferences [4]. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) describes MMR as “a methodological approach that focuses on research questions that call for real-life contextual understandings, multi-level perspectives, and socio-cultural influences” (p.3). It is often used when one singular approach (qualitative or quantitative) is inadequate to answer complex research questions [5].

Best practices in MMR include using standardized terminology and rationales to support the use of mixed methods in a single research study. Furthermore, the integration of qualitative and quantitative strands to validate and explain findings is extremely important and a critical component of MMR. However, the quality of MMR studies varies. While MMR is a promising methodology to better understand complex concepts by using multiple sources and types of data [5], the use of MMR in studies with children with T1D is limited. Furthermore, it is unclear how researchers design, conduct, and interpret MMR in this population. The goal of this focused review is to identify and synthesize studies that used mixed methods designs to investigate diabetes management in children with T1D.

Methods

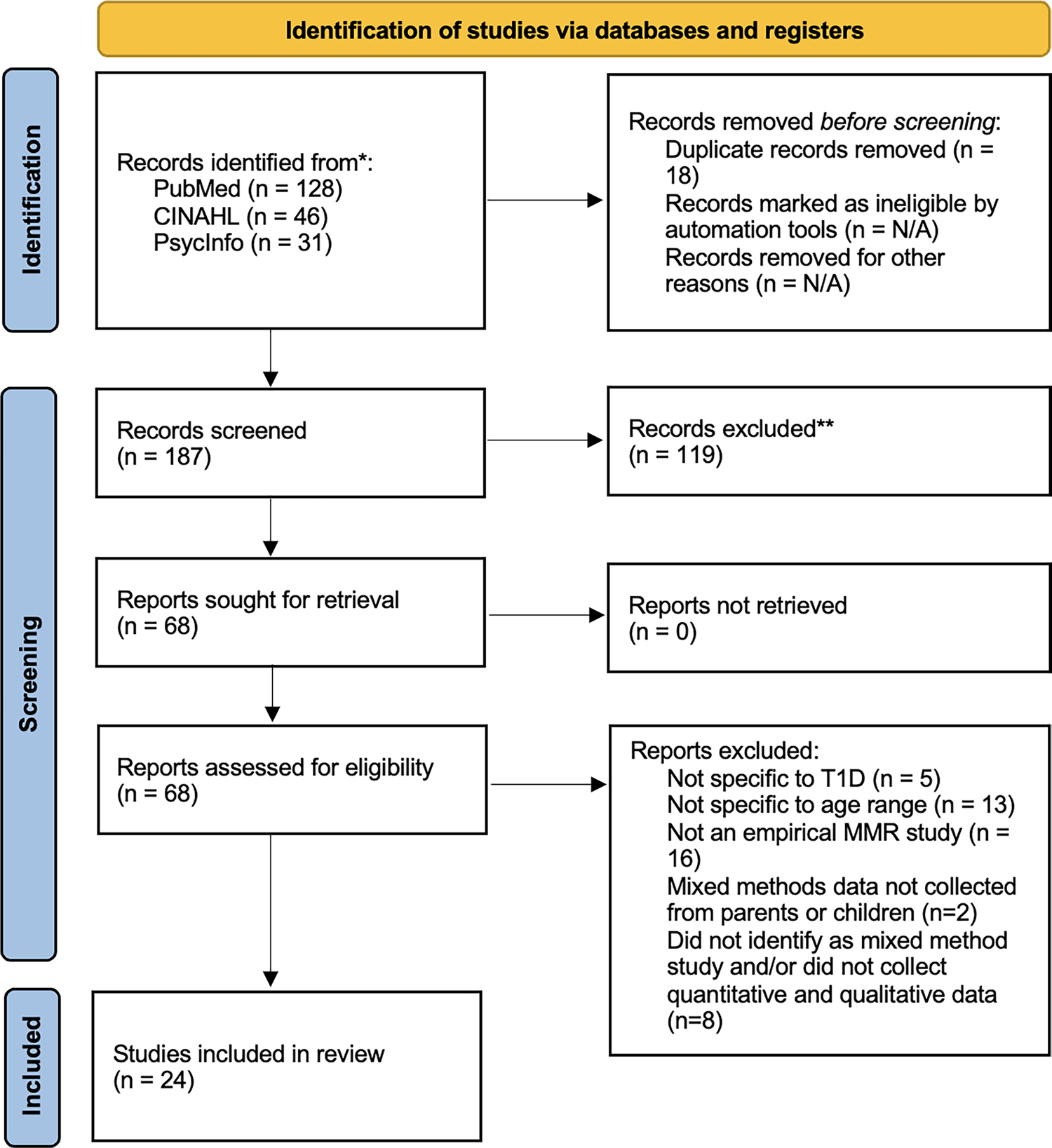

We conducted a focused literature review to identify empirical MMR studies performed with children with T1D (0–19 years old) internationally. Databases searched included PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. Search terms, including Boolean operators, included mixed methods, multimethod, multiple methods, qualitative and quantitative, pediatric, child, adolescent, diabetes, and type 1 diabetes. Search limitations included access to full text and the English language. Book chapters, commentaries, and letters to the editor were excluded. Studies were excluded if they did not self-identify as mixed methods or if they did not specify the use of qualitative and quantitative methods. Mixed method systematic reviews and study protocols were also excluded. Studies were included if they were empirical MMR studies and collected mixed methods data from children (0–19 years old) with T1D and/or their parents/caregivers. Since MMR studies on children with T1D are limited, and limited studies self-identify as mixed methods or specify the use of qualitative and quantitative methodologies, we included studies from 2007 to 2022 to better understand the use and evolution of MMR in this specific population. Initial results identified 73 articles by screening titles and abstracts, and full-text versions of these articles were retrieved. Screening and inclusion of articles for the current review can be found in a PRISMA diagram in Fig. 1. Twenty-four studies were identified for the current review (see Table 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram detailing review strategy

Table 1.

Studies using MMR to examine children with T1D

| Authors, date, and origin | Study purpose | Sample | MMR definition | MMR rationale | MMR design and other methods | Methods | Integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Disease management | |||||||

|

Lehmkuhl et al., 2009 USA |

To assess perceptions of disease management in children with T1D and their peers | N = 70 adolescents ages 11–16 attending a diabetes camp (45 had T1D; 25 were peers) | “Mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative data) approach” | “This type of mixed methods approach provides the most comprehensive picture of children’s attitudes and opinions about sensitive topics such as having a chronic illness like diabetes” Heary & Hennessy (2002) cited |

Mixed method, concurrent approach Quan + Qual |

Surveys that included multiple choice and open-ended questions with constant comparative analysis | Integration of data occurred after individual analysis of strands “the present study incorporated quantitative data about children’s perceptions in order to augment the qualitative” |

|

Patton et al., 2016 USA |

To examine knowledge of and perceived barriers to dietary management in parents of young children with T1D | N = 23 families with a child 1–6 years old with T1D | “The mixed methods design of this study integrated parents’ qualitative perceptions of healthful eating and a quantitative assessment of their child’s diet and mealtime behavior to identify specific targets for nutrition-focused components of diabetes education programs for families of young children.” Not cited |

“A significant contribution of this study is its presentation of both quantitative and qualitative data, allowing for integration of parents’ reported beliefs and behaviors and their personal narratives, perceptions, and opinions related to diet and mealtimes.” | Concurrent Quan + QUAL |

Demographic questionnaire, surveys, 3-day food diary with measured servings, semi-structured interview | “integrated parents’ qualitative perceptions of healthful eating and a quantitative assessment of their child’s diet and mealtime behavior” |

|

Erie et al., 2018 USA |

To explore continuous glucose monitoring practices in homes and schools in caregivers of children with T1D | N = 33 parents and 17 daytime caregivers of children 2–17 (x = 9.1, sd = 4) | Uses “mixed methods” terminology but does not define or cite with MMR literature | No rationale for using mixed methods design provided | Concurrent Quan + Qual |

Surveys with multiple choice and open-ended questions. Grounded theory was used to analyze qualitative data | Used mixed methods analysis to examine data |

|

Oser et al., 2020 USA |

To understand barriers and facilitators, including self-management challenges and successes, to raising a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and T1D |

Phase 1: N = 1398 blog posts Phase 2: N = 12 caregivers of children with T1D and ASD |

Uses “mixed methods” in the title but does not explicitly define or cite in the article | “This 2-step approach allowed further exploration of initial themes identified from the secondary data analysis of web-based content, with the advantage of being able to ask follow-up questions.” “utilizes a qualitative component to allow further exploration of the lived experience of raising a child with both T1D and ASD. We also sought to gather some exploratory information.” |

Sequential QUAL ↓ QUAL + quan |

Phase 1: thematic analysis of blog and forum posts Phase 2: Semi-structured interviews with thematic analysis and demographic surveys |

“The themes generated from this study were used to create an interview guide that was used in phase 2” |

|

Stanek et al., 2020 USA |

To examine the impact of stressful life events on diabetes management in the first year of diagnosis | N = 128 families of children 5–9 years old with recent-onset T1D | Uses “mixed methods” terminology but does not define or cite | No rationale for using MMR; “The objectives of this study were to examine the impact of stressful life events on T1D characteristics of school-age children with recent-onset T1D, and to identify family psychological stressors correlated with greater numbers of stressful life events using a mixed methods design.” | Longitudinal, MMR design QUAN + qual |

Surveys, open-ended questions No clear qualitative methodology |

No clear integration |

|

Faulds et al., 2021 Faulds et al., 2020 USA |

To understand adolescents’ self-management behaviors, including barriers and facilitators, when using diabetes technologies | Phase 1: N = 80 children ages 10–18 with T1D Phase 2: N = 10 children ages 10–18 with T1D |

Uses “mixed methods” terminology but does not define or cite | Cites Happ et al. (2006) to justify the approach used in the MMR study | Sequential, mixed method study Quan → Qual |

Phase 1: Surveys; health outcomes data Phase 2: Semi-structured interviews with a qualitative descriptive approach |

Phase 1 findings were used to recruit participants for phase 2 “Selected quantitative outcomes from the larger descriptive study were contrasted and compared to further dimensionalize main themes and patterns” |

|

Morone et al., 2021 USA |

To understand social determinants of health that act as barriers to diabetes management, especially in single-parent black households | Phase 1: N = 4/16 parents Phase 2: 9 parents Phase 3: 105 parents |

Uses “mixed methods” terminology but does not define or cite with MMR literature | “sequential, exploratory design... to ensure that parents generated, prioritized, and explained their own study ideas.” | Sequential, exploratory, 3-phase mixed methods study Qual → Quan |

Phase 1: Focus group and NGT sessions Phase 2: semi-structured interviews Phase 3: Survey development and administration |

Each phase of data informed subsequent phases Qualitative data from phases 1 and 2 were used to develop the survey administered in phase 3 |

| Support | |||||||

| Rearick et al., 2011 USA | To explore peer support in parents of children newly diagnosed with T1D following the Social Support to Empower Parents (STEP) intervention |

N = 21 parents completed interviews N = 11 parents completed surveys |

Uses “mixed methods” terminology but does not explicitly define “concurrent nested mixed-methods study—with qualitative inquiry as the core component (ie, the interview) and with quantitative inquiry as the nested component” Flemming (2007) cited |

“The use of a mixed-methods approach can provide a more balanced perspective of experience, moving toward holism” | Concurrent, nested QUAL(quan) |

Framework-informed interviews with content analysis, survey (family measurement measure) | Integration during interpretation of qualitative and quantitative data |

|

Hayes et al., 2017 UK |

To understand what creates a supportive school environment and how school environments may contribute to diabetes management; specifically looked at perceived stress, resiliency, and perceived social support | Phase 1 = 54 students 11–16 years old with T1D Phase 2 = 6 children |

Uses “mixed methods” terminology but does not explicitly define Creswell et al. (2002) & Robson (2011) are cited |

Not explicitly explained but appears to be confirmatory with emphasis placed on one strand to highlight and strengthen findings of the other strand “The qualitative data built on the findings of the quantitative data and pupils’ views highlighted important themes related to resilience and managing T1D in a UK school setting” |

Sequential, explanatory strategy QUAN → qual | Phase 1: Surveys including the Resiliency Scale for Children & Adolescents Phase 2: semi-structured interviews with thematic analysis |

Scores from the Resiliency Scale for Children & Adolescents in phase 1 were used to select participants to complete phase 2 |

| Development and evaluation of interventions/measures | |||||||

|

Carroll et al., 2007 USA |

To evaluate user satisfaction with a pilot study using an integrated phone system | N = 10 adolescents 13–18 years old | Refers to mixed methods in abstract but does not define, cite, or use terminology in the article | “...mixed quantitative and qualitative methods to evaluate user satisfaction with the integrated system” | Qual—> QUAN | focus groups, surveys | Qualitative findings were used in intervention design/feedback; the quantitative sample was a subsample of the qualitative sample |

|

Monaghan et al., 2011 USA |

To assess parent satisfaction of a 5-session intervention to enhance parent mastery of diabetes management | Phase 1: N = 12 parents of children ages 1–6 years with T1D Phase 2: N = 4 parents of children ages 1–6 years with T1D |

“Mixed-methods research strategies can be employed to learn both to what degree and how and why an intervention works (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009).” |

“Program evaluation, an integral component of clinical trial research, incorporates quantitative and qualitative methods, with qualitative methods being particularly useful in modifying existing interventions, evaluating intervention delivery, determining for whom the intervention is most beneficial, and assessing what components may be downsized or enhanced” Sandelwoski (2000) cited |

Sequential, MMR design QUAN → qual Program evaluation |

Phase 1: Surveys Phase 2: in-depth interviews with thematic analysis |

“Results from qualitative analyses were integrated with quantitative findings to identify possible program enhancements and maximize effectiveness of an intervention program for parents of young children with T1D.” |

|

Frøisland et al., 2012 Norway |

To pilot test 2 mobile phone applications to explore how mobile phones can be used for follow-up with adolescents with T1D, and guide future interventions | N = 12 adolescents ages 13–19 years old with T1D | Uses “mixed methods” in the title but does not explicitly define or cite in the article | Triangulation: “This study used triangulation of methods to provide details about the phenomenon studied that would not be available with the use of one method alone.” | QUAL + quan | Surveys and semi-structured interviews with field notes were performed at completion of the 3-month intervention | Integration of data took place after individual analysis of strands Quantitative data were used to support qualitative findings |

|

Barnard et al., 2014 UK |

To explore experiences of adolescents and their parents who participated in a pilot closed-loop insulin delivery study |

N = 15 adolescents (12–18 years old) N = 13 parents |

“Mixed methods psychosocial evaluation... using qualitative and quantitative research methods.” | “A mixed methods psychosocial evaluation was conducted to determine the utility of the device in terms of participants’ perceptions of lifestyle change, diabetes management, and fear of hypoglycemia.” | Concurrent Qual + Quan |

Pre- and post-intervention surveys, semi-structured interviews | Quantitative and qualitative strands were analyzed individually and integrated in discussion findings |

|

Jaser et al., 2014 USA |

To develop and test feasibility of a positive psychology intervention | N = 39 adolescents 13–17 years old and their parents | Does not define, cite, or use mixed method terminology, but uses “quantitative and qualitative data” | “...used quantitative and qualitative methodology to evaluate the intervention” | Longitudinal, pilot study QUAN (multiple timepoints) ↓ quan + qual (evaluation) |

Clinical data, surveys, semi-structured interviews | For evaluation, quantitative and qualitative strands were analyzed individually and integrated in discussion findings |

|

Cooper et al., 2014 UK |

To develop and test the Adolescent Diabetes Needs Assessment Tool | N = 171 children 12–18 years old | Uses “mixed methods” terminology but does not define or cite | No rationale for using mixed methods design provided | Qual—> QUAN | Literature search w/ secondary framework analysis, item review, reliability, and validity testing | Themes elicited from qualitative literature review were used to develop items |

|

Cooper et al., 2018 UK |

An evaluation study to assess feasibility of using an app, the Adolescent Diabetes Needs Assessment Tool | While there were 89 adolescents aged 12–18 years old with T1D who participated in the intervention, evaluation measures were completed with providers in the clinic | Uses “mixed methods” terminology but does not explicitly define or cite | No explicit MMR rationale but suggest that MMR is helpful to determine methodological recommendations for a future, large-scale study and to assess for overlap between strand findings to help explain outcomes | Non-randomized, mixed method design Quan + Qual |

Data collected from the app, and surveys and 3 focus group interviews at the completion of the intervention | Integration of data took place after individual analysis of strands |

|

Mitchell et al., 2018 Mitchell et al., 2016 UK |

To examine feasibility of an intervention to improve physical activity in children with T1D |

N = 20 children aged 7–16 years with T1D (10 in the RCT group/10 in the control group). 16 children completed qualitative interviews |

Uses “mixed methods” terminology but does not define or cite | No explicit MMR rationale; “The Medical Research council (MRC) framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions strongly advises carrying out feasibility and pilot work prior to running a full-scale trial; therefore, in keeping with phases 1 and 2 of the MRC framework, the aim of this study was to use a mixed-method study design” | Pilot RCT with mixed method study design Quan + QUAL Qualitative interviews followed intervention completion |

Surveys, anthropometric measures, accelerometer data, and semi-structured interviews analyzed with 6-stage thematic process | Integration of data took place after individual analysis of strands and qualitative data was used to explain quantitative findings |

|

Whittemore et al., 2018 USA |

To understand experiences of parenting adolescents with T1D and develop a prototype for an eHealth program | Phase 1: N = 21 parents of adolescents ages 12–18 Phase 2: N = 16 providers Phase 3: N = 53 parents and 27 providers |

“multiphase method was used generating both qualitative and quantitative data at multiple time points” | No clear rationale, but states “mixed-methods evaluation” | Phase 1: (Qual) Phase 2: prototype development Phase 3: mixed methods evaluation (QUAL + quan) |

Semi-structured interviews, focus groups, surveys | Findings from phase 1 used to inform Phase 2. Phase 3 evaluated the prototype developed in Phase 2. Some of the sample from Phase 1 also completed Phase 3 |

|

Albanese-O’Neill et al., 2019 USA |

To design and evaluate online, mobile diabetes education for fathers of children with T1D to improve diabetes knowledge and self-efficacy | Phase 1: N = 30 fathers of children ages 6–17 with T1D Phase 3: N = 33 fathers who did not participate in Phase 1 |

Uses “mixed methods” terminology but does not explicitly define Cites Creswell (2008) |

Rationale provided for the use of the evaluation design, but not for specific MMR methodology: “...study design was informed by the small but growing field of literature on the best practices for eHealth tool development.” | Multiyear, mixed method study with 3 phases Quan + Qual ↓ Website design ↓ QUAN + qual |

Phase 1: Exploratory research with semi-structured interviews and surveys Phase 2: Website/subdomain development Phase 3: Evaluation |

Integration of data at each phase of data collection. Findings from individual phases used to inform subsequent phases |

|

Connan et al., 2019 Canada |

To design, develop and refine an online education module |

N = 18 children N = 15 caregivers *in children < 8 parent-report only & in children > 16 child-report only |

Uses the phrase “mixed-methods usability testing approach,” but does not define or cite | “...to determine usability and further refine the e-module prototype” | Quan + Qual | 2 iterative cycles: semi-structured interviews, observation, surveys | Quantitative and qualitative strands were analyzed individually and integrated in discussion findings |

|

Kaya Meral & Yildirim, 2020 Turkey |

To assess the effects of psychodrama group therapy on quality of life, depression, and adaptive skills in mothers of children with T1D | N = 14 mothers of children with T1D | “A mixed research method that included qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis process. The design classification of the research was a convergent parallel design.” Not cited |

The rationale for using MMR design was not explicitly stated | Convergent, parallel, MMR design Concurrent Quan + Qual *Fig. 1 details the research design |

Randomized pre and posttest control group design with surveys Phenomenological methods with group records, Moreno’s social atom directive |

Integration of data took place after individual analysis of strands |

|

Versloot et al., 2021 Canada |

To describe the implementation and evaluation of a 4-step care model related to quality of life in adolescents with T1D | N = 236 adolescents 13–17 years old | “mixed quantitative and qualitative methods” | “...a mixed quantitative and qualitative evaluation of a pilot implementation project to gain insights into the concerns reported by adolescents with T1D on...” | 4-step iterative process followed with evaluation Quan + Qual |

Focus groups, semi-structured interviews, medical records, surveys, HbA1c | For evaluation, quantitative and qualitative strands were analyzed individually and integrated in discussion findings |

|

Hilliard et al., 2022 USA |

To develop and test a family behavioral intervention | Phase 1: N = 500 + families of children < 7 with T1D; N = 79 families with children < 8 years old Phase 2 and 3: N = 50 (intervention group) N = 40 (crossover group) |

“mixed methods (i.e., survey data, qualitative research)” | No clear rationale provided, but mixed methods used to inform intervention development | 3 phases with mixed methods assessment Quan—> Qual ↓ Intervention delivery ↓ QUAN + qual |

Analysis of data from T1D database, semi-structured interviews, surveys with open-ended questions | “Experts in behavioral health and diabetes ... designed the FBI targets, materials, and protocol based on these mixed-methods results.” |

| Education/communication | |||||||

|

Howe et al., 2015 USA |

To understand and explore health literacy and communication experiences with diabetes educators in parents of children with T1D |

N = 162 parents that completed surveys N = 24 parents that completed interviews |

Uses “mixed methods” terminology but does not define or cite | “We used a mixed methods design with the intention that the quantitative and qualitative data sets would be complementary to more fully explain the communication processes between parents and diabetes educators.” | Sequential Quan—> Qual |

Surveys, semi-structured interviews with content analysis | Survey findings for health literacy were used to select parents with high and low literacy scores to participate in interviews Mixing occurred in the interpretation phase |

Identified studies were reviewed using Plano Clark and Ivankova’s socio-ecological framework for mixed methods research [6]. This framework provides a guide to evaluate the dynamic and complex relationships that may be found in MMR while considering personal, interdisciplinary, and social contexts. These interrelated contexts may influence every aspect of the MMR process and include things such as the researchers’ personal beliefs, researcher-participant interactions, and acceptance of research methodology within specific disciplines [6]. For this review, the socio-ecological framework, particularly the use of MMR definitions, rationales, design, integration, and supporting literature, was used to guide the evaluation of MMR quality. Authors SD and MR organized the studies by theme and then evaluated the studies in consideration of MMR process and context per Plano Clark and Ivankova’s socio-ecological framework.

Findings

Four major themes emerged from the review. These include diabetes management, support, development and evaluation of interventions/measures, and communication. In addition to these themes, frequently noted concepts, such as education and emotional health, were also identified.

Themes

Development and Evaluation of Interventions/Measures

The most common theme identified centered on the development and evaluation of interventions and measures. Fourteen (58%) studies focused on interventions related to T1D. Interventional research included evaluation of the intervention design, feasibility, and outcomes, as well as patient and parent satisfaction with interventions. Interventions that were evaluated included online education and eHealth programs [7–9], mobile phone and phone app interventions [10–12], and educational, behavioral, and training-focused interventions [13–17]. Other studies focused on care delivery [18, 19] or measurement development [20].

Online education interventions tended to focus on parents rather than children. While Connan and colleagues used feedback from parents (n = 18) and children (n = 15) through interviews, observations, and surveys to evaluate online education modules for parents and children [8], other studies focused on the development and evaluation of parent-centered online education programs using fathers (n = 30) of children with T1D [7], or providers (n = 27) and parents (n = 53) of adolescents with T1D [9]. Conversely, interventions focused on mobile phones and phone apps were more likely to be child-centered to increase diabetes knowledge and assist children in self-management [10–12]. Cooper and colleagues used surveys, interviews, focus groups, and data downloaded from the app to examine self-management in 89 adolescents aged 12–18 years old [11], while Frøisland and colleagues used surveys, interviews, and field notes in 12 adolescents ages 13–19 years old with T1D [12].

Several educational, behavioral, and training-focused interventions were represented as well. For example, Hilliard and colleagues used mixed methods with multiple data sources to develop and evaluate a family behavioral intervention using data from a national database, semi-structured interviews, and surveys with open-ended questions [21]. Other educational, behavioral, and training-focused included the Supporting Parents intervention which used social-cognitive theory to improve skills and knowledge to help parents (n = 12) manage T1D in their child ages 1–6 years [17], the ActivPals intervention to improve physical activity in children and adolescents 7–16 years old with diabetes [22], and an unnamed psychodrama group therapy intervention to help mothers of children with T1D process and role play feelings surrounding disease management [15]. Overall, a variety of interventions focused on education, self-management, and support that were developed and evaluated using MMR methodology with data collected from both parents and children.

Diabetes Management

The second theme that emerged focused on disease management. Seven of the 24 studies (29%) examined various concepts, such as dietary management [23] and glucose monitoring [24] associated with disease management. Of these seven, two studies centered their focus on disease management in children and adolescents [25, 26], while five looked at disease management in parents, caregivers, and families of children with T1D [23, 24, 27–29]. When examining diabetes management, many researchers sought to identify and understand various barriers and facilitators of disease management [23, 25, 27, 28, 30]. For example, using food diaries, surveys, and interviews with parents (n = 23), Patton and colleagues found that barriers to healthy eating included picky eating, limited time to prepare healthy meals, perceived costs of healthy food, and peer influence on food choices in families of children 1–6 years old [23]. Similarly, Oser and colleagues examined children with concurrent T1D and autism spectrum disorder using blog posts (n = 1,398) and semi-structured interviews (n = 12) to identify and better understand barriers to disease management [28]. They identified barriers including lack of support, challenges navigating multiple providers, and sensory issues that made it difficult to monitor glucose levels and administer insulin.

In addition to general barriers and facilitators to disease management, researchers also focused on more specific aspects of diabetes management, such as continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) [24, 30]. In examining CGM, Erie and colleagues found that parents of children ages 2–17 (n = 33 parents; 17 daytime caregivers) expected daytime caregivers to respond to and treat low blood glucose levels and that this was facilitated by CGM [24]. Relatedly, Faulds and colleagues examined barriers and facilitators to using diabetes technology, such as CGM, in adolescents aged 10–18 using surveys (n = 80) and semi-structured interviews (n = 10) [25, 30]. They found that on days when adolescents had better glucose levels, they performed less self-management, while on days when they had poorer glucose levels, they performed more self-management.

Diabetes management was also examined in the context of social determinants of health (SDOH) [27] and stressful life events (SLEs) [29]. Using nominal group technique (NGT)—focus groups in which participants develop and rank themes—(n = 20), semi-structured interviews (n = 9), and surveys (n = 105), Morone and colleagues noted that SDOH can either act as a barrier or facilitator to disease management and found that Black, single-parent families faced numerous challenges related to SDOH [27]. Social determinants of health specific to the sample included under-resourced schools, unsafe neighborhoods, structural racism, lack of social capital, and economic and emotional impact of diabetes management. Similarly, barriers to diabetes management related to SLEs and emotional health were examined in the first year following diagnosis in 128 families of children 5–9 years old using surveys with open-ended questions [29]. Findings indicated that parents experienced more depression, worse coping, and had more parent–child conflict when families experienced more SLEs. Although most studies examined day-to-day activities, there were a wide variety of factors that were included when examining disease management in children. These factors varied from access to food, to navigating health care services, to glucose monitoring, and more.

Support

Support was another primary theme identified in studies [31, 32]. Rearick and colleagues focused on parental peer support following diagnosis with TID in a concurrent, nested MMR study [32]. Parents completed interviews (n = 21) and surveys (n = 11). The investigators found that structured, peer-support systems were beneficial for parents and that parents found the availability, practical tips, and common ground shared by peer mentors to be helpful when managing T1D in children.

Relatedly, Hayes and colleagues focused on support specific to children in school settings [31]. Specifically, they used child-report to better understand what children perceive as supportive behaviors and environments. The researchers found that personal resilience was related to perceived support and perceived stress in children ages 11–16 (n = 54) with T1D [31]. Survey responses were further explained using semi-structured interviews with children (n = 6). Support was especially noted through interactions with other students, understanding the roles of others when managing T1D, and finding a balance between disease management, school, and life outside of school. Most studies examining support focused on support from peers and within school settings.

Communication

A final theme, although only the primary focus of one article, was communication. Howe and colleagues examined health literacy and communication experiences in parents when interacting with diabetes educators using surveys (n = 162) and interviews (n = 24). They found that health literacy dictated what forms of communication parents preferred [33]. This may be helpful when designing interventions supporting the daily management of diabetes.

Concepts Frequently Noted

Several concepts also emerged that were related to the intervention or outcomes in multiple studies. One concept that appeared throughout studies was emotional health. Many studies assessed emotional health concepts, such as depression, anxiety, stress, and quality of life, although they were not the main theme or focus of the study [14, 15, 19, 29, 31]. Education was another common concept in many studies [7–9, 23, 26, 33]. Similar to emotional health, education focused on the adult experience with the exception of Connan and colleagues who included child feedback in addition to parental feedback of educational experiences [8].

MMR Definitions, Rationales, and Design

In addition to examining studies by theme, consideration was also given to the MMR process. This includes definitions, rationales, and designs chosen by researchers when planning and implementing a MMR study. These components are important to consider because they may alter how researchers integrate data from qualitative and quantitative strands, and thus form conclusions from study findings [6]

MMR Definitions

MMR definitions address how researchers conceptualize and apply mixed methods design to their research [6]. Less than half of the studies explicitly defined [9, 15, 17, 18, 21, 26] or cited MMR literature [7, 31, 32] to highlight their conceptualization of MMR. Other researchers simply use terms of qualitative and quantitative data/methods to emphasize a mixed methods approach [14, 19]. Monaghan and colleagues were the only researchers to provide an explicit definition of MMR and cite MMR literature [17, 34, 35]. The definition provided by Monaghan and colleagues emphasizes a community of research practice and is commonly found in social psychology [6]. Of the other studies that include a definition, most defined MMR by the inclusion of qualitative and quantitative data in the study. These definitions tend to coincide either with a method perspective of MMR (the mixing of qualitative and quantitative methods) or a methodology perspective of MMR (mixing qualitative and quantitative approaches through the research process) [6].

MMR Rationales

MMR rationales provide justification for why researchers use a specific approach to answer unique research questions [6]. Ten of the 24 studies (42%) provided a rationale specific to the use of MMR in the study [12, 17, 23, 26–28, 30–33]. Only 3 of the 12 used MMR literature to support their rationale [17, 26, 30]. Lack of MMR rationales was especially noted in intervention development studies and studies that integrated MMR with other methodologies [7, 11, 16]. Rather, these studies focused on the rationale for the primary study design, rather than a rationale for the MMR design. Other studies hinted or suggested rationales for use of the MMR design, but mainly focused on the significance of the study. For example, many researchers imply the use of mixed methods (of quantitative and qualitative data) is needed for evaluation purposes or to answer research questions [8–11, 14, 18, 19, 29], but the connection between the research questions and MMR design is not explicit.

MMR Design

There are several design typologies that a researcher considers when selecting a MMR design that may impact timing, priority, sequencing, and integration of study strands [6]. Most studies followed a sequential or concurrent MMR design. Although no studies specified priority given to each strand, it was possible to interpret which strand (qualitative vs quantitative) was given priority through the evaluation of methods, analysis, and discussion of the findings. Only one study [15] included a procedural diagram to depict the flow of MMR activities that highlighted when data were collected, analyzed, and integrated during the research process.

While most data were collected in one or two phases of a study, some researchers used multiple phases (especially in interventional design and evaluation studies) and incorporated unique steps such as NGT sessions (Morone et al., 2021) to enhance study findings. A few studies integrated MMR with other methods, including program evaluation [17], pilot randomized and non-randomized control trials [11, 14, 16, 22], and embedding [32]. Additionally, many of the studies that focused on intervention were integrated with other research designs, and definitions and rationales were excluded. One exception to this is Monaghan and colleagues who cited Teddlie and Tashakkori [35] and Sandelowski [34] in the definition, rationale, and application of MMR [17].

Application of the study design may directly impact the quality of study findings. Most studies assured quality by evaluating quality specific to qualitative and quantitative strands separately. While several studies gave separate, but equitable, consideration to different strands, a few studies focused more on concepts related to the quality of one strand or the other [28, 32]. One study used triangulation methods—a method to validate data collected from different sources through convergence [6]—to verify findings and ensure MMR quality[12], while a third study noted that triangulation would strengthen study findings[31]. Similarly, other researchers spoke to the strength of inferences and interpretation of varying results between qualitative and quantitative data findings [15, 17, 27, 33].

Discussion

The most common theme underlying MMR studies in children with T1D was development and evaluation or interventions/measures, most of which were related to disease management. These studies tended to focus on day-to-day activities such as dietary management, insulin administration, and glucose monitoring. The use of mixed methods is not surprising considering the intense regimens that must be followed to achieve and maintain glycemic targets [1, 3, 36]. Additionally, it is recommended that mixed methods are used when developing evidenced-based interventions and measurement tools [37]. However, despite intensive insulin regimens and daily management of the disease, many children still have difficulty maintaining glucose levels within the target range [2].

A multitude of factors have been shown to negatively impact glycemic levels in children with T1D including disparities in access to care related to race, socioeconomic status, and/or diabetes education [38, 39]. Additionally, compared to children without diabetes, children with T1D experience higher levels of emotional and mental health disturbances that may impair their ability to maintain glycemic targets [36, 40]. However, mental health and emotional well-being are personal concepts. Measurement of these concepts, such as depression, stress, anxiety, resilience, and more, can be difficult, especially in younger children, but self-report data from the child’s perspective is vital in research. Less than half of the studies included child-reported data; most relied on parent and caregiver-report. Of the studies that used child-report, few included children younger than 11 [8, 22]. However, evidence supports that children are able to reliably self-report mental health concepts, such as stress, as young as 7 [41]. Furthermore, most studies focused on the experiences, perceptions, challenges, and well-being in parents/caregivers of children with T1D. While parents and caregivers have primary responsibility for disease management, especially in younger children, the input of the child should not be overlooked. The creativity that MMR offers in study design [6], may offer unique solutions to include the child’s voice in research, especially when studying personal topics such as mental health and well-being. Furthermore, collection from the child and the parent may allow triangulation of data to validate study findings.

In addition to considering how data are collected, and who data are collected from, it is important to consider how MMR studies are described and disseminated. For example, Faulds and colleagues reported findings from phase 1 and phase 2 of their study in separate papers [25, 30]. Similarly, Mitchell and colleagues summarized a subset of qualitative data collected as part of a larger MMR study [22] and reported the protocol and methods in a separate paper [16]. In these studies, the description of definitions, rationales, design, and integration of strands in the MMR process was limited. These limitations and inconsistencies make it somewhat difficult to assess the quality of the study since reports were focused on only one strand of data collection and findings, and data collection and findings from the other strand were reported elsewhere.

Lack of consistent guidelines to conduct and disseminate MMR has also made it somewhat difficult to evaluate MMR studies. This may explain why few studies cited MMR literature or provided MMR definitions and rationales for the study. The lack of MMR rationales was especially noted in studies which examined the feasibility and effectiveness interventions or performed interventional research. However, this is not necessarily unexpected. Many times, MMR techniques are embedded as a part of the evaluation research or other research methodology [6] and therefore researchers rely on rationales for the primary research methodology to guide the study. Although not specifically identified in individual studies [11, 17, 22], the integration of MMR in other research practices, such as RCT and program evaluation, suggest the use of advanced applications in mixed methods design including mixed methods experiments and mixed method evaluation [6].

Similarly, there was also inconsistency in what was considered to be a MMR study. Two studies included in this review used mixed method terminology to describe the study but did not readily appear to use an explicit mixed methods design [28, 29]. Instead, they may be better classified as a multiphase qualitative [28] or quantitative [29] study. Additional consideration should be given to the terminology to describe MMR practice and process since inconsistent terminology is used to describe MMR [6]. This may be confounded by the translation of some studies to English[15] and the failure to include key concepts in the MMR process, such as definitions and rationales, since specific terminology may be lost in translation. Journal guidelines and academic expectations (i.e., “publish or perish”) may have also played a role in how MMR findings were disseminated by limiting or emphasizing components of the study that are able to be published due to page limits and reviewer feedback on the study. Page limitations may have contributed to lack of MMR-specific information, such as MMR definitions, rationales, and/or integration of qualitative and quantitative strands, as well as resulted in different strands (qualitative and quantitative) of the MMR study being reported in different papers, or limited summaries of MMR data from a larger study being published.

Considerations for Research and Practice

The current review highlights several considerations for research and practice. For example, many of the MMR studies reviewed examined the implementation of various interventions to improve education and management related to T1D. The use of MMR to assess the strengths and weaknesses of interventions improves the applicability of the intervention in practice by evaluating feasibility and acceptability in a more robust way. Feedback from participants that includes both quantitative and qualitative data provides better guidance on how to improve and implement the intervention in various populations. While results from many of these interventions were still being evaluated, preliminary findings suggest their applicability in clinical settings, and practitioners may consider the incorporation of some interventions, or components of interventions, to improve health outcomes in children with T1D.

Additionally, this review highlights the need for future MMR studies in children with T1D. While many of the MMR studies in this review focused on the parent or caregiver of children with T1D, directly involving children in the data collection process will provide valuable information that may alter how practitioners care for children with T1D. MMR is a promising method to involve children in research, by allowing researchers to use the combined strengths of qualitative and quantitative methods to enhance understanding of complex concepts from multiple perspectives [42]. Similarly, MMR offers unique ways to answer different research questions, to elicit and understand unexpected results, and to verify or explain findings 43. This is especially true as researchers seek to better understand the complex concepts of SDOH and stress in children with T1D.

External factors, such as funding priorities and grants, may impact MMR through social contexts. Most studies included in this review disclosed funding for research. Sources of funding included national/public grants, institutional/academic grants, foundation grants, and industry grants. Since grant funding is usually awarded on the priorities of the funder, this may impact the way MMR is designed and conducted. Additionally, many studies were funded by multiple grants and grant mechanisms [7, 12, 24, 27, 30, 32, 33]. Multiple funding sources, and thus multiple funding priorities, may create conflict in study design and implementation, ultimately altering the MMR process. This will be an important consideration as researchers and practitioners seek funding for research and practice.

Conclusion

This review highlighted MMR studies pertaining to children with T1D. Overall, MMR studies that examined children with T1D were limited and tended to focus on parents of children with T1D. Major themes identified in MMR studies included disease management, support, development and evaluation of interventions/measures, and communication. Additionally, this review highlighted inconsistencies in what was considered to be a MMR study, and how reports of MMR involving children with T1D vary in the literature. While there is limited consistency in MMR studies, MMR offers a promising solution to examine complex concepts in children with T1D by offering creative and unique methods to answer multiple research questions. Findings from future MMR studies, especially ones focused on complex concepts such as mental health and disease management, may illuminate ways to mitigate stress and distress in children with T1D and lead to improved glycemic levels and better health outcomes. Future studies should include MMR design and data collection in children when attempting to examine complex research questions in children with T1D.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Gail Kouame, MLIS, and Justin Robertson, MLIS, for their assistance in the literature search.

Funding

Dr. Davis’ efforts to this work were supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number KL2TR003097. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declarations

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Hood KK, Peterson CM, Rohan JM, Drotar D. Association between adherence and glycemic control in pediatric type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1171–9. 10.1542/peds.2009-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller KM, Foster NC, Beck RW, et al. Current state of type 1 diabetes treatment in the U.S.: updated data from the T1D Exchange Clinic Registry. Dia Care. 2015;38(6):971–8. 10.2337/dc15-0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orchard TJ, Nathan DM, Zinman B, et al. Association between 7 years of intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes and long-term mortality. JAMA. 2015;313(1):45. 10.1001/jama.2014.16107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tashakkori A, Creswell JW. Editorial: The new era of mixed methods. J Mixed Methods Res. 2007;1(1):3–7. 10.1177/2345678906293042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences. Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. 2nd ed. National Institutes of Health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plano Clark VL, Ivankova NV. Mixed methods research: a guide to the field. SAGE; 2016. 10.4135/9781483398341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albanese-O’Neill A, Schatz DA, Thomas N, et al. Designing online and mobile diabetes education for fathers of children with type 1 diabetes: mixed methods study. JMIR Diabetes. 2019;4(3):e13724. 10.2196/13724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connan V, Marcon MA, Mahmud FH, et al. Online education for gluten-free diet teaching: Development and usability testing of an e-learning module for children with concurrent celiac disease and type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2019;20(3):293–303. 10.1111/pedi.12815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whittemore R, Zincavage RM, Jaser SS, et al. Development of an eHealth program for parents of adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2018;44(1):72–82. 10.1177/0145721717748606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll AE, Marrero DG, Downs SM. The HealthPia Gluco-Pack Diabetes phone: a usability study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2007;9(2):158–64. 10.1089/dia.2006.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper H, Lancaster GA, Gichuru P, Peak M. A mixed methods study to evaluate the feasibility of using the Adolescent Diabetes Needs Assessment Tool App in paediatric diabetes care in preparation for a longitudinal cohort study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018;4:13. 10.1186/s40814-017-0164-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frøisland DH, Arsand E, Skårderud F. Improving diabetes care for young people with type 1 diabetes through visual learning on mobile phones: mixed-methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(4):e111. 10.2196/jmir.2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilliard ME, Perlus JG, Clark LM, et al. Perspectives from before and after the pediatric to adult care transition: a mixed-methods study in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(2):346–54. 10.2337/dc13-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaser SS, Patel N, Rothman RL, Choi L, Whittemore R. Check it! A randomized pilot of a positive psychology intervention to improve adherence in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2014;40(5):659–67. 10.1177/0145721714535990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaya Meral D, Yıldırım EA. The effect of psychodrama group therapy on the role skills, adaptation process, quality of life and depression applied to mothers of children with type 1 diabetes: a mixed methods study. JAREN Published online. 2020. 10.5222/jaren.2020.23500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell F, Kirk A, Robertson K, Reilly JJ. Development and feasibility testing of an intervention to support active lifestyles in youths with type 1 diabetes—the ActivPals programme: a study protocol. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2016;2(1):66. 10.1186/s40814-016-0106-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monaghan M, Sanders RE, Kelly KP, Cogen FR, Streisand R. Using qualitative methods to guide clinical trial design: Parent recommendations for intervention modification in Type 1 diabetes. J Fam Psychol. 2011;25(6):868–72. 10.1037/a0024178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnard KD, Wysocki T, Allen JM, et al. Closing the loop overnight at home setting: psychosocial impact for adolescents with type 1 diabetes and their parents. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2014;2(1):e000025. 10.1136/bmjdrc-2014-000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Versloot J, Ali A, Minotti SC, et al. All together: Integrated care for youth with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(6):889–99. 10.1111/pedi.13242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper H, Spencer J, Lancaster GA, et al. Development and psychometric testing of the online Adolescent Diabetes Needs Assessment Tool (ADNAT). J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(2):454–68. 10.1111/jan.12235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilliard ME, Commissariat PV, Kanapka L, et al. Development and delivery of a brief family behavioral intervention to support continuous glucose monitor use in young children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2022;23(6):792–8. 10.1111/pedi.13349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell F, Wilkie L, Robertson K, Reilly JJ, Kirk A. Feasibility and pilot study of an intervention to support active lifestyles in youth with type 1 diabetes: the ActivPals study. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(3):443–9. 10.1111/pedi.12615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patton SR, Clements MA, George K, Goggin K. “I don’t want them to feel different”: a mixed methods study of parents’ beliefs and dietary management strategies for their young children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(2):272–82. 10.1016/j.jand.2015.06.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erie C, Van Name MA, Weyman K, et al. Schooling diabetes: Use of continuous glucose monitoring and remote monitors in the home and school settings. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(1):92–7. 10.1111/pedi.12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faulds ER, Hoffman RP, Grey M, et al. Self-management among pre-teen and adolescent diabetes device users. Pediatr Diabetes. 2020;21(8):1525–36. 10.1111/pedi.13131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehmkuhl HD, Merlo LJ, Devine K, et al. Perceptions of type 1 diabetes among affected youth and their peers. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009;16(3):209–15. 10.1007/s10880-009-9164-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morone JF, Teitelman AM, Cronholm PF, Hawkes CP, Lipman TH. Influence of social determinants of health barriers to family management of type 1 diabetes in Black single parent families: a mixed methods study. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(8):1150–61. 10.1111/pedi.13276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oser TK, Oser SM, Parascando JA, et al. Challenges and successes in raising a child with type 1 diabetes and autism spectrum disorder: mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e17184. 10.2196/17184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanek KR, Noser AE, Patton SR, Clements MA, Youngkin EM, Majidi S. Stressful life events, parental psychosocial factors, and glycemic management in school-aged children during the 1 year follow-up of new-onset type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2020;21(4):673–80. 10.1111/pedi.13012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faulds ER, Grey M, Tubbs-Cooley H, et al. Expect the unexpected: adolescent and pre-teens’ experience of diabetes technology self-management. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(7):1051–62. 10.1111/pedi.13249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes B, Lopez L, Price A. Resilience, stress and perceptions of school-based support for young people managing diabetes in school. Journal of Diabetes Nursing. 2017;21(6):212–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rearick EM, Sullivan-Bolyai S, Bova C, Knafl KA. Parents of children newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes: experiences with social support and family management. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37(4):508–18. 10.1177/0145721711412979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howe CJ, Cipher Daisha J, LeFlore J, Lipman TH. Parent health literacy and communication with diabetes educators in a pediatric diabetes clinic: a mixed methods approach. J Health Communic. 2015;20(2):50–9. 10.1080/10810730.2015.1083636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandelowski M Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-method studies. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(3):246–55. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teddlie C, Tashakkori A. Foundations of mixed methods research: integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. SAGE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiang JL, Maahs DM, Garvey KC, et al. Type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Dia Care. 2018;41(9):2026–44. 10.2337/dci18-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Why mixed methods? Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://publichealth.jhu.edu/academics/academic-program-finder/training-grants/mixed-methods-research-training-program-for-the-health-sciences/about-the-program/why-mixed-methods [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rechenberg K, Whittemore R, Grey M, Jaser S. Contribution of income to self-management and health outcomes in pediatric type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2016;17(2):120–6. 10.1111/pedi.12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valenzuela JM, Seid M, Waitzfelder B, et al. Prevalence of and disparities in barriers to care experienced by youth with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr. 2014;164(6):1369–1375.e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Helgeson VS, Palladino DK, Reynolds KA, Becker DJ, Escobar O, Siminerio L. Relationships and health among emerging adults with and without Type 1 diabetes. Health Psychol. 2014;33(10):1125–33. 10.1037/a0033511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lynch T, Davis SL, Johnson AH, et al. Definitions, theories, and measurement of stress in children. J Pediatr Nurs. 2022;66:202–12. 10.1016/j.pedn.2022.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morgan DL. Integrating qualitative and quantitative methods: a pragmatic approach. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2014. 10.4135/9781544304533 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryman A Barriers to integrating quantitative and qualitative research. J Mixed Methods Res. 2007;1(1):8–22. 10.1177/2345678906290531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]