Abstract

BACKGROUND

Posttraumatic intradural hematomas of the cervical spine are rare findings that may yield significant neurological deficits if they compress the spinal cord. These compressive hematomas require prompt surgical evacuation. In certain instances, intradural hematomas may form from avulsion of cervical nerve roots.

OBSERVATIONS

The authors present the case of a 29-year-old male who presented with right upper-extremity weakness in the setting of polytrauma after a motor vehicle accident. He had no cervical fractures but subsequently developed right lower-extremity weakness. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a compressive hematoma of the cervical spine that was initially read as an epidural hematoma. However, intraoperatively, it was found to be a subdural hematoma, eccentric to the right, stemming from an avulsion of the right C6 nerve root.

LESSONS

Posttraumatic cervical subdural hematomas require rapid surgical evacuation if neurological deficits are present. The source of the hematoma may be an avulsed nerve root, and the associated deficits may be unilateral if the hematoma is eccentric to one side. Surgeons should be prepared for the possibility of an intradural hematoma even in instances in which MRI appears consistent with an epidural hematoma.

Keywords: cervical spinal cord, cervical spine, intradural hematoma, nerve root avulsion, spine trauma

ABBREVIATIONS: BLE = bilateral lower extremity, LUE = left upper extremity, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, RLE = right lower extremity

Posttraumatic spinal hematomas are possible after even minor trauma.1 In many cases, these hematomas, whether intradural or epidural, may remain asymptomatic and require no additional intervention.2 That said, compressive hematomas of the spinal cord can have devastating neurological consequences. In the largest review to date, 4.4% of traumas involving a vertebral fracture and 5.4% of traumas without fractures were associated with spinal hematomas causing spinal cord compression.1 In instances in which compressive hematoma is suspected, prompt surgical evacuation of the hemorrhage via decompressive laminectomy is indicated to prevent further neurological decline. When hematomas are intradural but extramedullary, careful opening of the thecal sac is also required for evacuation.3

Most posttraumatic spinal hematomas are epidural in nature (as high as 75% in some of the literature).1,4 Thus, intradural hematomas, which can include subdural, subarachnoid, or intramedullary hemorrhages, are rare entities overall but can be seen in a variety of settings. Prior studies have examined spinal intradural hematomas as a result of trauma, iatrogenic causes, spinal anesthesia, or coagulopathy, though the exact etiology for these hemorrhages can remain unknown in a nontrivial percentage of cases.1,5–9 Furthermore, the distribution of hematoma location follows a relatively bimodal distribution, clustering in the cervical spine and the lower thoracic spine.1 To our knowledge, an example of cervical intradural hematoma associated with traumatic nerve root avulsion has not been published since 1980.10 Herein, we detail a case of right-sided paraplegia due to subdural hemorrhage stemming from an avulsed cervical nerve root.

Illustrative Case

A 29-year-old male with no past medical history presented to the emergency department as a polytrauma case after a motor vehicle accident. He had sustained extensive skull and appendicular fractures as well as an L3 burst fracture (with minimal retropulsion). He did not have any cervical spine fractures, but air was noted within the cervical spinal canal (Fig. 1). On initial examination, he was intubated with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 10T. He would open his eyes to voice and follow commands in his left upper extremity (LUE). He could move his bilateral lower extremities (BLEs) spontaneously antigravity. He had no movement in his right upper extremity (RUE).

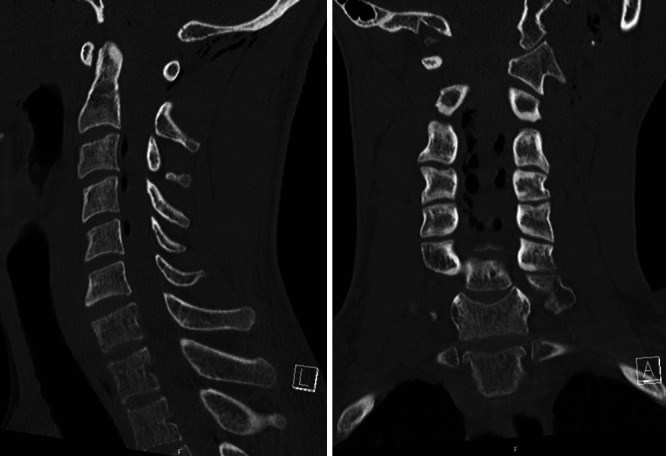

FIG. 1.

Cervical computed tomography (CT) scans demonstrating air in the cervical spinal canal but no fractures of the cervical spine.

He was admitted to the surgical intensive care unit. Approximately 12 hours after admission, he developed new acute weakness in his right lower extremity (RLE), now without any movement to noxious stimuli. He was still unable to move his RUE. Emergent MRI of the cervical spine demonstrated what appeared to be a dorsal epidural hematoma spanning from C3 to C6 causing critical spinal canal stenosis (Fig. 2). He was promptly taken to surgery for evacuation of this hematoma. He underwent C3–5 laminectomies, but no epidural blood was visualized after decompression. Moreover, the thecal sac appeared to be distended, particularly on the right side, with areas of dark coloration seen under the dura. Intraoperative ultrasound was used to visualize a subdural hematoma underlying the decompressed levels.

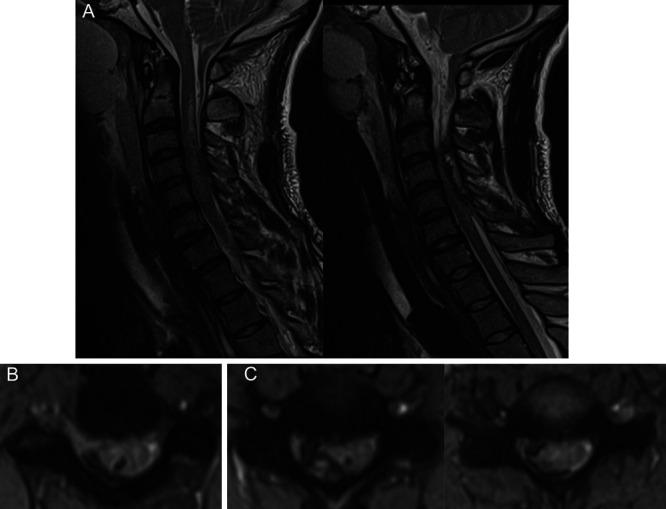

FIG. 2.

Cervical spine MRI demonstrating what was initially read as a dorsal epidural hematoma, including a midline sagittal T2 turbo inversion recovery magnitude (TIRM) image (A), sagittal TIRM image showing the hematoma eccentric to the right (B), and axial TIRM images from the levels of C3–4, C4–5, and C5–6 (C).

The dura was incised. Immediately, a firm clot was expressed from within the thecal sac (Fig. 3). As this hematoma was evacuated, cerebrospinal fluid began to flow more obviously around the spinal cord. Furthermore, it appeared that the hematoma extended down to the right C6 nerve root, which appeared to be avulsed with active bleeding from the radicular vessels, likely venous in origin given the lack of brisk pulsatile flow (Fig. 3). Meticulous hemostasis was obtained at this level. Ultimately, though most of the hematoma was successfully removed, there was clot tracking distally along the avulsed C6 nerve root that was not pursued. The nerve root itself was not addressed. Furthermore, there was a small amount of intramedullary hemorrhage that could not be safely addressed surgically.

FIG. 3.

Intraoperative images of removal of intradural hematoma (left) and active extravasation appearing to originate from an avulsed right C6 nerve root (right).

The dura and the wound were closed in the standard fashion. Placement of a lumbar drain was attempted after closure to aid in clearing additional blood from the thecal sac, but the drain catheter was unable to be successfully passed through the needle, likely because of his L3 fracture with associated hematoma. This lumbar drain was eventually placed the following day under fluoroscopic guidance and was removed on postoperative day 9. Postoperatively, the patient regained a trace amount of strength in his RLE but remained plegic in his RUE. He was ultimately discharged to inpatient rehabilitation on postoperative day 24.

At his most recent postoperative follow-up, more than 2 months from surgery, the patient had regained a small amount of strength in the right triceps (2/5 strength) and wrist extension (3/5 strength), although he remained profoundly weak in these areas. He still had 0/5 strength in the right biceps. His RLE strength had improved to 4/5. MRI of the right brachial plexus at this time demonstrated increased signal within the nerve roots, trunks, divisions, and cord of the brachial plexus, particularly within the contributions from C5 to C7. MRI of the cervical spine was hardly able to visualize the right C5 and C6 nerve roots, even with specialized T2-weighted sequences, which was consistent with nerve root avulsion (Fig. 4). Subsequent electromyography and nerve conduction study showed a right pan-brachial plexopathy with no volitional motor units in the muscles innervated by the upper and middle trunks.

FIG. 4.

Follow-up postoperative magnetic resonance images demonstrating the absence of a right C6 nerve root, consistent with nerve root avulsion.

Patient Informed Consent

The necessary patient informed consent was obtained in this study.

Discussion

Observations

This case illustration is the second published instance of acute spinal cord compression from a cervical intradural hematoma caused by traumatic nerve root avulsion. In addition to the unique etiology of the intradural hemorrhage, multiple other aspects of this case are also noteworthy. This hematoma was eccentric to the right and causing primarily right-sided cord compression. Moreover, this case highlighted the difficulty in discerning intradural from epidural spinal hematomas. Evacuation of a subdural hematoma required a more involved surgery than originally anticipated. Therefore, surgeons should be prepared to enter the dura when addressing what appears to be an epidural hematoma, and the use of intraoperative ultrasound is recommended if the hematoma location is ambiguous.

Compressive hematomas of the spine are relatively rare complications of spinal trauma.1,2 Of the possible types of posttraumatic spinal hematomas, epidural hematomas are by far the most common.1 Intradural hematomas comprise a minority of posttraumatic hematomas, with subarachnoid hematomas being more common than subdural ones.4 Traumatic hematomas of the cervical spine are especially infrequent, with epidural hematomas found in only 2.5% of posttraumatic cervical spine injuries.2 A prior review has shown that at least 30% to 40% of patients who experience these hematomas have an underlying coagulopathy, although the patient in our case had no prior medical conditions or medication use and no evidence of coagulopathy on his preoperative/posttraumatic laboratory tests. MRI is the ideal imaging modality for differentiating subdural and epidural spinal hematomas. The two can be discerned by the signal of epidural fat: an epidural hematoma will obscure normal fat signal, whereas this fat signal will be preserved for subdural hematomas.11 Pneumorrhachis (air in the spinal canal), as seen in this patient, may be another indirect sign of significant occult injury.12

A similar report by de Andrada Pereira et al.3 detailed a case of traumatic cervical subarachnoid hemorrhage that presented as right-sided Brown-Sequard syndrome. The patient underwent C3–5 posterior decompression and fusion with a midline durotomy to evacuate the hemorrhage. Intraoperatively, the surgeons noted severe compression and edema of the C4 nerve root. They suspected that tearing of radicular vessels near where the nerve root exited the spinal cord allowed hemorrhage to enter the subarachnoid space. Spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage, in contrast to intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage, may form a discrete clot and thus create cord compression. In our case, the hemorrhage was subdural rather than subarachnoid, as clot was expressed immediately after opening the dura without having to excise the arachnoid. However, given the hematoma tracking along the avulsed right C6 nerve root, our case also serves to highlight the role that trauma to nerve roots and surrounding vasculature can play in compressive cervical hematomas. The patient in the case study by Andrada Pereira et al.3 did not experience neurological improvement after surgery.

The only other published work detailing an analogous case to this current illustration is a report from 1980 by Russell and Mangan10 in which they summarize an instance of compressive cervical subarachnoid and subdural hematoma after left-sided brachial plexus avulsion. Here, the patient was a sailor who had experienced an accident during which his left C5, C6, and C7 nerve roots were avulsed. Preoperatively, he had weak movement in his RUE but no movement in his LUE and BLEs. The authors describe intraoperative findings of subarachnoid hematoma that had ruptured through the arachnoid to extend into the subdural space. They performed laminectomies from C1 to C6, irrigated the hematoma, and closed the patient with the dura remaining open. Postoperatively, the patient retained weak strength in the RUE and voluntary movement in his BLEs (not antigravity) but no movement in the LUE.

Unfortunately, as detailed by these two previously discussed case reports, as well as our case illustration, improvements in neurological deficits after cervical hematoma evacuation can be minimal or absent. Indeed, postoperative recovery after surgery for compressive hematomas in general remains exceedingly difficult to predict. Even though the patient in our illustration was taken to the operating room in a timely fashion, he remains with limited (although improved) RUE strength. Fortunately, his RLE movement has significantly improved. At our institution, carefully selected patients are candidates for peripheral nerve transfers in the setting of spinal cord injury.13–15 This patient, given his limited RUE movement and evidence of prior nerve root avulsion, may be a suitable candidate for this type of treatment in the future.

Lessons

Posttraumatic cervical intradural hematomas require rapid surgical evacuation when causing neurological deficits. These deficits may be unilateral in nature if a hematoma is eccentric to one side. Importantly, surgeons should be prepared for the possibility of an intradural hematoma even in instances in which MRI appears consistent with epidural hematoma. When searching for posttraumatic sources of intradural hematoma, hemorrhage from an avulsed nerve root may be the source. Despite prompt surgical intervention, improvements in neurological deficits may be minimal. Surgeons may consider nerve transfer surgery in select cases.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Yahanda, Connor, Desai, Gupta, Cadieux. Acquisition of data: Yahanda, Connor, Desai, Giles, Gupta. Analysis and interpretation of data: Yahanda, Desai, Gupta, Cadieux. Drafting the article: Yahanda, Connor. Critically revising the article: all authors. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: Yahanda, Desai, Giles, Gupta, Cadieux. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Yahanda. Study supervision: Ray, Cadieux.

References

- 1. Kreppel D, Antoniadis G, Seeling W. Spinal hematoma: a literature survey with meta-analysis of 613 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2003;26(1):1–49. doi: 10.1007/s10143-002-0224-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ricart PA, Verma R, Fineberg SJ, et al. Post-traumatic cervical spine epidural hematoma: incidence and risk factors. Injury. 2017;48(11):2529–2533. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Andrada Pereira B, Meyer BM, Alvarez Reyes A, Orenday-Barraza JM, Brasiliense LB, Hurlbert RJ. Traumatic cervical spine subarachnoid hemorrhage with hematoma and cord compression presenting as Brown-Séqüard syndrome: illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons. 2022;4(23):CASE22431. doi: 10.3171/CASE22431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al Ani AH, Alhurrat MAD, Al kasabreh MA, Khalil SI. Traumatic cervical spine intradural hematoma: a case report and review of literature. Interdiscip Neurosurg. 2020;21:100779. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruce-Brand RA, Colleran GC, Broderick JM, et al. Acute nontraumatic spinal intradural hematoma in a patient on warfarin. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(5):695–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mehta SH, Shah KA, Werner CD, White TG, Lo SL. Ventral spinal cord herniation causing spinal intradural hematoma and subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14(8):e28349. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sath S, Kalidindi KKV, Manghwani J, Chhabra HS. Spinal epidural hematoma post evacuation of spontaneous spinal intradural hematoma. World Neurosurg. 2020;135:160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.11.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ji JY, Ahn JM, Chung JH, et al. Spinal intradural hematoma after spinal anesthesia in a young male patient: case report and review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4845. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19084845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reidy J, Mobbs R. Spinal subdural hematoma: rare complication of spinal decompression Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2022;158:114–117. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.10.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Russell NA, Mangan MA. Acute spinal cord compression by subarachnoid and subdural hematoma occurring in association with brachial plexus avulsion. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1980;52(3):410–413. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.52.3.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moriarty HK, O Cearbhaill R, Moriarty PD, Stanley E, Lawler LP, Kavanagh EC. MR imaging of spinal haematoma: a pictorial review. Br J Radiol. 2019;92(1095):20180532. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20180532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oertel MF, Korinth MC, Reinges MHT, Krings T, Terbeck S, Gilsbach JM. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of pneumorrhachis. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(suppl 5):636–643. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0160-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dibble CF, Khalifeh JM, VanVoorhis A, Rich JT, Ray WZ. Novel nerve transfers for motor and sensory restoration in high cervical spinal cord injury. World Neurosurg. 2019;128:611–615.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.04.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khalifeh JM, Dibble CF, Van Voorhis A, et al. Nerve transfers in the upper extremity following cervical spinal cord injury. Part 2: Preliminary results of a prospective clinical trial. J Neurosurg Spine. 2019;31(5):1–13. doi: 10.3171/2019.4.SPINE19399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Javeed S, Dibble CF, Greenberg JK, et al. Upper limb nerve transfer surgery in patients with tetraplegia. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2243890. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.43890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]