Abstract

Two novel insertion sequence elements, ISLhe1 and ISLhe15, were located upstream of the genes encoding the β-galactosidase enzyme in Lactobacillus helveticus commercial starter strains. Strains with the IS982 family element, ISLhe1, demonstrated reduced β-galactosidase activity compared to the L. helveticus type strain, whereas strains with the ISLhe15 element expressed β-galactosidase in the absence of lactose.

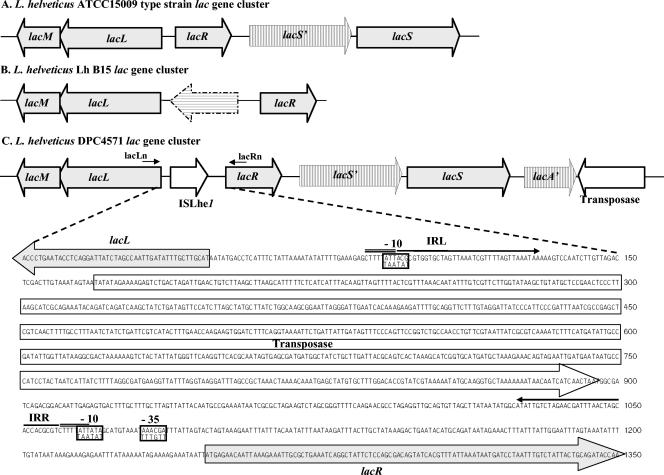

Lactobacillus helveticus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii are traditionally grouped as thermophilic starter cultures due to their use in the manufacture of “cooked” Swiss and Italian cheeses (2). The genetic elements required to metabolize the primary milk sugar, lactose, has been characterized in both L. delbrueckii subspecies, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis (8), and has recently been described for the type strain of L. helveticus (4). The lactose genes in L. helveticus and L. delbrueckii comprise a lactose antiport permease (lacS), a regulator (lacR), and a β-galactosidase (lacLM or lacZ). In L. helveticus, the lacLM genes are divergently transcribed from lacR and lacS, which are separated by 2 kb of DNA encoding the remnants of another permease gene (4). In the L. delbrueckii subspecies, the β-galactosidase (lacZ), regulator, and permease occur in the order lacSZR and are flanked by multiple insertion sequence (IS) elements (8). The genes are regulated by lacR in L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis, but the genetically unstable L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus lac operon is constitutively expressed due to mutations that inactivate the lacR gene.

L. helveticus DPC 4571 was isolated from Swiss cheese and has been thoroughly investigated as a starter and adjunct culture. The strain demonstrates a number of highly desirable traits including rapid autolysis, reduced bitterness, and increased flavor notes in cheese (6, 7). In this study, the lac genes of DPC 4571 were found to differ from those in the type strain in that an IS element was located in the lacL promoter region of DPC 4571 and the activity of the lacLM gene product, the β-galactosidase enzyme, was reduced. Screening of 40 L. helveticus isolates from both culture collections and industrial sources revealed a third genotype associated with the lac operon that was associated with lactose-independent β-galactosidase activity.

Organization of the L. helveticus DPC 4571 lactose gene cluster.

The sequence data for the lactose operon of L. helveticus DPC 4571 were obtained as part of an ongoing genome-sequencing project (unpublished data). Sequence data was imported into the Kodon software package (Applied-Maths, St-Marten-Latem, Belgium), and the locus corresponding to the L. helveticus ATCC 15009 type strain lac operon (GenBank accession numbers AJ512877 to AJ512880) was identified. The lacMLRS gene products were found to be identical (99% identity at the amino acid level) to those of the L. helveticus ATCC 15009 type strain, and the gene order was also conserved in DPC 4571 (Fig. 1). However, the DPC 4571 lac operon differed significantly in the distance between the ATG start codons of the lacL and lacR genes. Further inspection of the intergenic region revealed that it encoded a homologue (75% identity at the nucleotide sequence level) of the IS element designated ISLh1 by Mahillon and Chandler (10) and originally described as part of the L. helveticus cryptic plasmid, pLH3 (11). ISLh1 belongs to the IS982 family of insertion sequences, which is named for an IS element first described in another dairy starter culture, Lactococcus lactis (12). The right end of the ISLh1-like element, named ISLhe1 following the convention of the IS database (www.is.biotoul.fr/is.html), is located 47 bp upstream of the lacL start codon and significantly alters the sequence and spacing of the predicted −10 and −35 promoter hexamers of the gene (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the various lac gene clusters of L. helveticus. (A) lac operon of the L. helveticus ATCC 15009 type strain. Adapted from reference 4. (B) lac operon of L. helveticus Lh B15. (C) lac operon of L. helveticus DPC 4571 with details of the lacLR intergenic region, showing the start of the lacL and lacR genes (shaded arrows) and the transposase gene (open arrow). The inverted repeats (IRL and IRR) are overlined with an arrow, and the direct repeats are double overlined. The putative −10 and −35 sequences are boxed, with the corresponding type strain hexamers (4) aligned below the DPC 4571 sequence. Regions encoding fragments of a permease gene (lacS'), β-galactosidase (lacA'), and transposase (dashed outline) are indicated by hatched arrows. The positions of the lacLc and LacRn primers are indicated above the DPC 4571 gene cluster.

In addition to the novel insertion element, the sequence surrounding the lac genes was extended downstream of the lacS gene reported for the ATCC 15009 type strain (Fig. 1). An open reading frame (ORF) encoding a product of 321 amino acids was identified with significant similarity to the N terminus (50% identity for the first 300 amino acids) of the characterized β-galactosidase of a psychrophilic Planococcus strain (GenBank accession number AAF75984) and the predicted β-galactosidase of several other microorganisms (data not shown). The L. helveticus operon therefore contains a truncated β-galactosidase gene in addition to a number of short ORFs between the lacR and lacS genes that appear to be derived from the fragmentation of a lacS permease gene by nonsense codons (Fig. 1). A further ORF downstream of the truncated β-galactosidase gene had significant similarity to the transposase gene of ISL6 (45% identity at the amino acid level) found in the lac operon of L. delbrueckii (GenBank accession number AAK83661). The presence of the apparently redundant lactose permease, β-galactosidase gene, and the transposases suggests that the lactose operon of L. helveticus has undergone extensive rearrangement.

Variation of the lacRL intergenic region among L. helveticus strains.

The difference between the type strain and DPC 4571 prompted us to investigate the lacLR intergenic region in other L. helveticus strains. Chromosomal DNA was extracted from 40 L. helveticus strains present in the Dairy Products Research Centre, Moorepark, culture collection (Table 1) by using shearing with glass beads as described previously (1). The lacLR region was amplified using primers lacLn (5′-GACCCTGAATACCTCAGG-3′) and lacRn (5′-TTCAGCGCATCTCGCTCT-3′) with Taq polymerase (Bioline, London, England). Thirty strains, including the ATCC 15009 type strain, produced a 0.5-kb product with the lacRn and lacLn primers (Table 1). Eight strains, including DPC 4571, produced a 1.5-kb band, indicating the presence of the same IS element as in DPC 4571. The remaining three strains produced a larger band of approximately 2 kb. To determine the reason for the larger amplification product, the 2-kb fragment from one of the three strains, LhB15, was sequenced directly on both strands by using the MWG sequencing service (Ebersberg, Germany). Analysis of the sequence data revealed that the intergenic region of these strains contains another putative 1,596-bp IS element, designated ISLhe15. Direct 12-bp repeats of target DNA were identified, flanked by 23-bp imperfect inverted-repeat (IR) sequences. The IS element contains two ORFs that may be subject to programmed translational frameshifting since a −1 frameshift (at position 736) would produce a single ORF with significant similarity (31% identity at the amino acid level) to the putative transposase encoded by the 1,504-bp IS element in the vanSB2 gene of Streptococcus gallolyticus 4-C11 (GenBank accession number AY035712). Programmed translational frameshifting is a mechanism by which IS element transposases have been shown to control their transposition activity (10). In contrast to DPC 4571, the IS element in LhB15 was positioned 90 bp upstream of lacL translational start site and the predicted promoter elements of lacL were unaffected.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Size of lacLR PCR product (kb) | Strain sourcea |

|---|---|---|

| L. helveticus DPC 4571 | 1.5 | DPC |

| L. helveticus NCDO 257 | 0.5 | NCDO |

| L. helveticus NCDO 1209 | 0.5 | NCDO |

| L. helveticus NCDO 1243 | 1.5 | NCDO |

| L. helveticus NCDO 1244 | 0.5 | NCDO |

| L. helveticus NCDO 2 | 0.5 | NCDO |

| L. helveticus NCDO 1697 | 0.5 | NCDO |

| L. helveticus NCDO 1748 | 0.5 | NCDO |

| L. helveticus 303 | 0.5 | J. P. Accolas, INRA |

| L. helveticus Lb 7 | 1.5 | Wisby |

| L. helveticus L 103 | 0.5 | E. Parente, Italy |

| L. helveticus L 206 | 0.5 | E. Parente, Italy |

| L. helveticus L 207 | 0.5 | E. Parente, Italy |

| L. helveticus L 208 | 0.5 | E. Parente, Italy |

| L. helveticus L 220 | 0.5 | E. Parente, Italy |

| L. helveticus L 604 | 0.5 | E. Parente, Italy |

| L. helveticus L 611 | 0.5 | E. Parente, Italy |

| L. helveticus L 617 | 0.5 | E. Parente, Italy |

| L. helveticus LMG 6413/ATCC 15009T | 0.5 | LMG |

| L. helveticus LMG 6894 | 0.5 | LMG |

| L. helveticus LMG 11445 | 0.5 | LMG |

| L. helveticus LMG 11446 | 0.5 | LMG |

| L. helveticus LMG 11447 | 0.5 | LMG |

| L. helveticus LMG 11448 | 0.5 | LMG |

| L. helveticus LMG 11474 | 0.5 | LMG |

| L. helveticus LMG 13522 | 0.5 | LMG |

| L. helveticus 21PA | 0.5 | G. Scolari, Italy |

| L. helveticus L89b | 0.5 | G. Scolari, Italy |

| L. helveticus LH1 | 0.5 | Chr. Hansen |

| L. helveticus LH B01 (Hb01) | 0.5 | Chr. Hansen |

| L. helveticus LH B02 (Hb02) | 1.5 | Chr. Hansen |

| L. helveticus Lh B1 | 0.5 | Chr. Hansen |

| L. helveticus Lh B10 | 2 | Chr. Hansen |

| L. helveticus Lh B11 | 2 | Chr. Hansen |

| L. helveticus Lh B15 | 2 | Chr. Hansen |

| L. helveticus Lh B18 | 1.5 | Chr. Hansen |

| L. helveticus Lh B20 | 1.5 | Chr. Hansen |

| L. helveticus Lh B21 | 1.5 | Chr. Hansen |

| L. helveticus LH CH1 | 0.5 | Chr. Hansen |

| L. helveticus LH CH5 | 0.5 | Chr. Hansen |

| L. helveticus HL2 HL2 | 1.5 | Chr. Hansen |

DPC, Dairy Products Research Center, Moorepark, Ireland. LMG, Culture Collection Laboratorium Mikrobiologie, Gent, Belgium; NCDO, National Collection of Dairy Organisms, National Institute for Research in Dairying, Shinfield, England; Chr. Hansen, Chr. Hansens Laboratory Ireland Ltd., Little Island, Cork, Ireland; Wisby: Wisby starter cultures and media, Danisco Cultor Niebüll, GmbH.

Regulation of β-galactosidase activity in vivo.

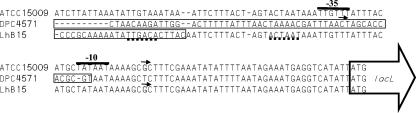

To determine the effect of the various genotypes of the lacLR locus on β-galactosidase activity, assays were performed with representative cultures for each of the three genotypes grown in MRS broth (3) prepared without glucose and the appropriate sugar was added postautoclaving. Assays were performed with 100-μl samples harvested at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of circa 0.5 and resuspended in 500 μl of LacZ buffer [50 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2 PO4, 10 mM HCl, 1 mM MySO4 (7H2O)]. Cells were permeabilized with chloroform, and 100 μl of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (0.04 mg/ml) was added. The reaction was stopped with 400 μl of 1 M sodium carbonate. Activities were calculated as follows: activity = (OD420 × d × 1,000)/(3.5 × t × OD600), where 3.5 is the millimolar extinction coefficient of the o-nitrophenol, d is the dilution factor, and t is the reaction time. In agreement with the transcription analyses of the lac operon of the L. helveticus type strain (4), ATCC 15009 β-galactosidase activity was dependent on the presence of lactose in the medium (Table 2). It was also noted that enzyme activity was repressed but not eliminated with lactose and glucose in the medium. For the three strains with the DPC 4571 lac operon genotype (DPC 4571, LH B02, and Lh B20), the β-galactosidase activity induced by lactose was significantly lower than that for the type strain (Table 2). The IS element altered the predicted −35 and −10 promoter elements upstream of lacL in these strains (Fig. 2), and to determine if this directly affected transcription, the transcription start sites of the type strain and DPC4571 lacL genes were mapped using rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) analysis (5). Total RNA was extracted from 20 ml of L. helveticus culture grown to an OD600 between 0.4 and 0.5 in MRS supplemented with the appropriate sugar. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 1 ml of TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) with 0.7 g of acid-washed glass beads (<106 μm; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.), and disrupted in a bead beater. Following centrifugation, the aqueous phase was extracted twice with TRIzol and chloroform. The 5′-RACE analysis was performed with the 5′/3′ RACE kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) as specified by the manufacturer. Transcription of the type strain was found to have initiated 37 bp upstream of the lacL start codon (Fig. 2), which fitted with the previously predicted −10 and −35 sequences (4). In contrast, the start of the lacL transcript in DPC 4571 was located a further 24 bp upstream of the type strain start site and originated within the inverted repeat of the IS element (Fig. 2). In the mesophilic starter culture L. lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis, an IS982 element upstream of the citQRP genes, required for citrate uptake, also influences the expression of downstream genes (9). A new promoter composed of a −35 hexamer 12 bp from the right end of the IS982 element and the −10 hexamer from the resident sequence was responsible for 20% of the citP transcript; the remainder was still derived from the native promoter. Many IS elements possess outwardly directed −35 promoter hexamers in their terminal IRs and can create new promoters capable of driving the expression of neighboring genes when placed (by transposition) at the correct distance from a resident −10 hexamer (10). However, the transcript for the DPC 4571 lacL gene originated within the IS element, indicating that the promoter elements are carried solely by the ISLhe1 element. Interestingly, a citP transcript originating from within the IS element was also reported, but it was not found in its native host, L. lactis; rather, it was detected when the genes were cloned in a heterologous host, Escherichia coli (9).

TABLE 2.

β-Galactosidase activities detected for L. helveticus strains representing the three lac operon genotypes

| L. helveticus strain | IS element (kb)a | β-Galactose activity (units) withb:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5% Glucose | 0.5% Lactose | 0.5% glucose + 0.5% lactose | ||

| DPC 4571 | 1.5 | 59 ± 8 | 333 ± 12 | 296 ± 36 |

| LH B02 | 1.5 | 32 ± 0 | 317 ± 0 | 423 ± 15 |

| Lh B20 | 1.5 | 24 ± 0 | 586 ± 23 | 640 ± 8 |

| ATCC 15009 | None | 0 | 1,672 ± 86 | 625 ± 26 |

| Lh B1 | None | 48 ± 0 | 1,023 ± 23 | 992 ± 19 |

| Lh B15 | 2 | 541 ± 32 | 1,042 ± 33 | 710 ± 24 |

| Lh B10 | 2 | 568 ± 13 | 400 ± 0 | 755 ± 22 |

| Lh B11 | 2 | 429 ± 48 | 794 ± 38 | 561 ± 26 |

Distance between the lacLR genes in the lac operon indicating the presence of an IS element.

Strains cultured in MRS broth with 0.5% glucose and/or 0.5% lactose instead of 2% glucose.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the promoter regions of the lacL gene from the L. helveticus ATCC 15009 type strain, L. helveticus DPC 4571, and L. helveticus Lh B15. The translational start site of lacL is indicated by a large arrow, and the transcriptional start sites are indicated by small arrows above the corresponding nucleotide. The IS element sequence is boxed, and the putative −10 and −35 sequences are overlined. The alternative promoter elements in the Lh B15 sequence are underlined with a dashed line.

For the three strains with the novel ISLhe15 element, significant β-galactosidase activity was measured in the presence of glucose (Table 2). This activity was detected in strain Lh B15 even though the strain contains the same 48 bp of sequence upstream of lacLM as the glucose-repressed DPC 4571 promoter (Fig. 2). A possible explanation for the deregulated activity was that transcription was controlled by a second putative promoter upstream of lacLM composed of an outwardly directed −35 hexamer, located 5 bp upstream from the end of the IS element, and a resident −10 hexamer (Fig. 2). However, mapping of the start site determined that transcription of lacLM in strain Lh B15 initiated at the same site as the type strain in the presence of both glucose and lactose (Fig. 2). This result argued against the alternative promoter controlling lacLM expression. Another possibility was that the LacR repressor homologue was not active. In a similar study of the L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus lac operon (8), mutations that introduced premature stop codons in the lacR gene were shown to result in constitutive expression of β-galactosidase activity. Sequencing of the Lh B15 lacR gene revealed that, in contrast to L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, the predicted product of the Lh B15 lacR gene was identical to the type strain LacR protein (data not shown). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the mechanism of lacLM gene regulation in Lh B15 differs from that in other Lactobacillus species; further investigation of the lactose regulon in strain Lh B15 is required to account for the inability of the strain to repress β-galactosidase in the absence of lactose.

Conclusion.

Genetic variation occurs in the lac operon among L. helveticus strains due to the presence of either an IS982 family element, ISLhe1, or a larger novel IS element, ISLhe15, upstream of lacLM. The IS982 element is associated with reduced β-galactosidase activity, whereas strains with the ISLhe15 element show lactose-independent enzyme activity. These IS elements are associated predominantly with strains from commercial sources (Table 1), which suggests that selection of L. helveticus strains for use as commercial starter cultures may favor strains with alternative β-galactosidase expression.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence of the L. helveticus DPC 4571 lactose genes and the IS element in the lacLR intergenic region of L. helveticus Lh B15 have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers AY616518 and AY616519, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Olive Kenny for L. helveticus chromosomal DNA samples.

This work was funded in part by the Department of Agriculture and Food, Ireland, under the Food Institutional Research Measure, project reference number 01/R&D/TD/191.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coakley, M., R. P. Ross, and D. Donnelly. 1996. Application of the polymerase chain reaction to the rapid analysis of brewery yeast strains. J. Inst. Brew. 102:349-354. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cogan, T. M. 1996. History and taxonomy of starter cultures, p. 1-20. In T. M. Cogan and J.-P. Accolas (ed.), Dairy starter cultures. VCH Publishers, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 3.De Man, J. C., M. Rogosa, and M. E. Sharpe. 1960. A medium for cultivation of lactobacilli. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 23:130-135. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fortina, M. G., G. Ricci, D. Mora, S. Guglielmetti, and P. L. Manachini. 2003. Unusual organization for lactose and galactose gene clusters in Lactobacillus helveticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3238-3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frohman, M. A. 1994. On beyond classic RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends). PCR Methods Appl. 4:S40-S58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hannon, J. A., M. G. Wilkinson, C. M. Delahunty, J. M. Wallace, P. A. Morrissey, and T. P. Beresford. 2003. Use of autolytic starter systems to accelerate the ripening of Cheddar cheese. Int. Dairy J. 13:313-323. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiernan, R. C., T. P. Beresford, G. O'Cuinn, and K. N. Jordan. 2000. Autolysis of lactobacilli during Cheddar cheese ripening. Irish J. Agric. Food Res. 39:95-106. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapierre, L., B. Mollet, and J. E. Germond. 2002. Regulation and adaptive evolution of lactose operon expression in Lactobacillus delbrueckii. J. Bacteriol. 184:928-935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez de Felipe, F., C. Magni, D. de Mendoza, and P. Lopez. 1996. Transcriptional activation of the citrate permease P gene of Lactococcus lactis biovar diacetylactis by an insertion sequence-like element present in plasmid pCIT264. Mol. Gen. Genet. 250:428-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahillon, J., and M. Chandler. 1998. Insertion sequences. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:725-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pridmore, D., T. Stefanova, and B. Mollet. 1994. Cryptic plasmids from Lactobacillus helveticus and their evolutionary relationship. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 124:301-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu, W., I. Mierau, A. Mars, E. Johnson, G. Dunny, and L. L. McKay. 1995. Novel insertion sequence-like element IS982 in lactococci. Plasmid 33:218-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]