Abstract

Ellipsometric measurements were used to monitor the formation of a bacterial cell film on polarized metal surfaces (Al-brass and Ti). Under cathodic polarization bacterial attachment was measured from changes in the ellipsometric angles. These were fitted to an effective medium model for a nonabsorbing bacterial film with an effective refractive index (nf) of 1.38 and a thickness (df) of 160 ± 10 nm. From the optical measurements a surface coverage of 17% was estimated, in agreement with direct microscopic observations. The influence of bacteria on the formation of oxide films was monitored by ellipsometry following the film growth in situ. A strong inhibition of metal oxide film formation was observed, which was assigned to the decrease in oxygen concentration due to the presence of bacteria. It is shown that the irreversible adhesion of bacteria to the surface can be monitored ellipsometrically. Electrophoretic mobility is proposed as one of the factors determining bacterial attachment. The high sensitivity of ellipsometry and its usefulness for the determination of growth of interfacial bacterial films is demonstrated.

There is a wide interest in bacterial attachment to surfaces since this strongly influences many natural and industrial processes. Besides optical microscopic observations (4) important new advances have been made in the investigation of bacterial attachment, employing modern optical techniques. Evanescent field Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy has been extensively used for monitoring bacterial colonization of surfaces (36, 37), for instance, by following an amide band as a marker for biofilm biomass (38). Importantly, Suci et al. (43) have demonstrated that complementary data can be obtained from attenuated total reflection–Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy and reflected differential interference contrast microscopy for the in situ observation of hydrodynamic effects on the chemistry and architecture of biofilms.

Bacterial adhesion to metal surfaces and formation of biofilms is known to lead to the enhancement of corrosion rates (15, 17, 29, 30, 33), and localized corrosion is usually observed as a consequence of bacterial surface colonization. The mechanisms by which bacteria recognize and approach metal surfaces are not clear, but positive chemotaxis in the presence of heavy metal ion gradients from a corroding metal has been demonstrated (16). Once bacteria reach a solid surface both reversible and time-dependent irreversible adhesion processes take place (32). Primary events in substrate-bacteria interaction are well predicted by the Derjaguin, Landau, Verwey, and Overbeek (DLVO) theory of colloidal systems on hydrophobic low-energy surfaces, for instance, on polymers. In this case, long-range interactions (van der Waals) seem to play a major role in surface recognition (6, 45). Also, interactions with hydrophilic high-energy surfaces, such as those of metals, are significantly influenced by short-range double-layer effects (20) since most bacteria bear a negative surface charge.

Ellipsometry is a form of reflectance spectroscopy which measures the changes in amplitude and in degree of polarization of light reflected from a surface. These changes are expressed in terms of two so-called ellipsometric angles, Δ and Ψ (3, 22, 35). Δ gives the difference in the phase shift experienced by the reflected light beam for p and s optical polarization (p and s polarization are parallel and perpendicular, respectively, to the plane of light incidence), whereas tan Ψ is the ratio of the attenuation of the amplitude on reflection for p and s polarized light. Recent developments in ellipsometric equipment and software (25) have greatly simplified the measurement of these angles and the establishing of their relationship to the properties of the surface under investigation. In particular, since ellipsometry is a very sensitive surface technique, it can be conveniently used for the analysis of films on substrates. In the present work the effects of bacterial attachment at polarized and nonpolarized metal surfaces have been monitored by this technique and theoretical models have been used to determine interfacial optical properties of bacterial and oxide films.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Equipment and cells.

Ellipsometric measurements were conducted with a computer-controlled Gaertner L126 ellipsometer with a helium-neon laser (λ = 632.8 nm) at an angle of incidence of 70°. The electrochemical cell used has been previously described (8); it had appropriate entrances for counter and reference electrodes. The working electrode was placed at the bottom of the cell, and the cell body was secured to the cell base by side screws. Flat working electrodes of 2-cm2 exposed area were first abraded with 600 grit carborundum paper, polished with 0.05-μm alumina (type B; Buehler Ltd.), and finally rinsed with distilled water. The metal surfaces investigated were from materials commonly used in seawater heat exchangers: aluminum brass (ASTM B111) and titanium (99.6+%; Goodfellow, T1000431). All the experiments were performed in a 3.5% NaCl (BDH; AnalaR) solution, close to the chloride concentration of seawater. A KCl-saturated calomel electrode (SCE; Radiometer) was used as the reference electrode; the counterelectrode was made of a platinum wire immersed in the solution under study.

Biological material.

A pure culture of a Pseudomonas sp. strain isolated from a copper base alloy heat exchanger tube (5) was used. Cultures were grown at 32°C until the mid-exponential phase, as determined by the absorbance at 600 nm (A600) (12). A nutrient broth containing 0.1% meat extract (Difco), 0.2% yeast extract (β Lab), and 0.5% Bacto Peptone MC24 (Lab M) in artificial seawater (pH 8) was employed (9). The cells were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 9,300 rpm in a Sorvall RC 5B refrigerated centrifuge, washed with 3.5% NaCl at a pH of 7.2, centrifuged again, and resuspended in the same solution. In order to ensure an equal bacterial concentration for each experiment the absorbance of the test solution was set to an A600 of 0.150 (approximately 105 bacteria cm−3) by appropriate dilutions with 3.5% NaCl.

For the experiments to determine the influence of possible charge reversal of the cell wall by adsorption of Cu2+ ions (9) on attachment rate, CuCl2 was added to bacterial suspensions to a final concentration of 1 mM. After an incubation period of 10 min the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 9,300 rpm in the Sorvall centrifuge and resuspended in 3.5% NaCl at a pH of 7.2.

Ellipsometric measurements.

The ellipsometric angles Δ and Ψ were measured at constant time intervals, and the data were stored in a microcomputer (24). Before each experiment, the electrodes were prereduced by keeping them for 10 min at −0.6 V in the NaCl solution in order to obtain a reproducible bare substrate as a starting point for the measurements. A total of 2 ml of bacterial suspension was added to the cell, and measurements were taken every 30 s. In the charge reversal experiments 2 ml of the Cu2+-treated bacterial suspension was used. For the oxide growth experiments, the electrode was first kept at −0.6 V for approximately 30 min in the bacterial suspension. After this time, the potentiostat was disconnected and the electrode was allowed to reach the corrosion potential where oxide growth takes place. Measurements of the ellipsometric angles were taken at least for an extra 20 min and all ellipsometric calculations were carried out with commercial software (23).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Optical properties of the substrate.

Ellipsometric measurements of thin films require a well-characterized substrate (39). For copper and its alloys the rapid growth of oxide films in air after sample polishing results in a scatter of the initial measured values of Δ and Ψ. For this reason, it is better to use changes of the ellipsometric angles (δΔ and δΨ), relative either to the bare substrate or to a reproducible surface condition, for calculating film parameters (8).

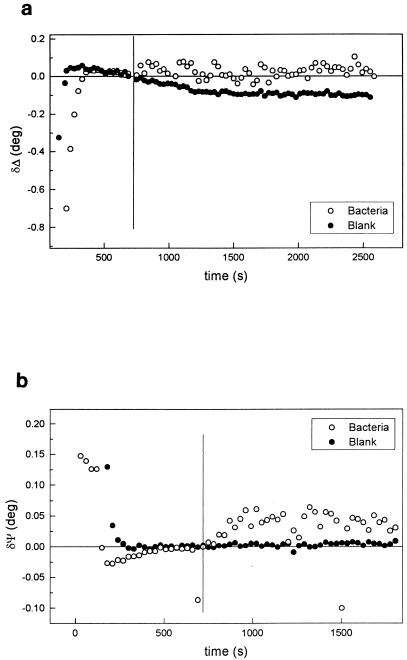

δΔ and δΨ values for blank experiments on Al-brass surfaces polarized at −0.6 V are shown in Fig. 1. Both Δ and Ψ rapidly reach constant values, but significant changes in Δ with time were observed after approximately 500 s from the time of applying the potential. The properties of corroding surfaces are variable during the initial phase of exposure to the corrosive medium. For this reason, the values of δΔ and δΨ were different for different samples during the first ∼500 s of exposure. After this period, steady-state properties were observed. The complex refractive index, ns = n − ksi, for the metal in contact with the solution was computed from the data for which Δ and Ψ were constant. Taking the refractive index of the solution as nsol = 1.378, and using commercial software (22), a value for ns of 0.645 − 3.35i was calculated. A full description of the ellipsometric equations used in these calculations can be found in references 3 and 35.

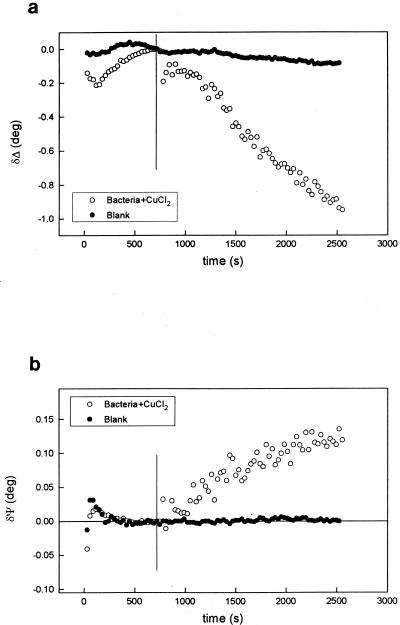

FIG. 1.

Variations of Δ (a) and Ψ (b) during cathodic polarization of Al-brass in 3.5% NaCl in the absence (•) and presence (○) of bacteria. The potential was kept constant at E = −0.6 V. The vertical lines show the times at which bacteria were added.

The real component of the index is very sensitive to the surface composition of the alloy and/or to the presence of surface oxides. However, the decrease observed cannot be due to surface dealloying since the value of Δ would increase if a layer of copper is present on the alloy surface as a consequence of minor surface dealloying. For example, it was calculated that a 1-nm layer of copper with ncu = 0.14 − 3.45i (8) increases Δ by 0.1 deg (23). In contrast, the same calculations based on the assumption of the presence of Cu2O (8) or ZnO (48) films lead to a strong decrease of Δ with coverage. Therefore, the observed long-term decrease of Δ with time (Fig. 1a) probably results from the formation of an oxide submonolayer, as previously observed for copper (8). The value of ns obtained at times between 200 and 500 s was used in the following calculations. As will be seen further on, the main conclusions are not affected by this choice.

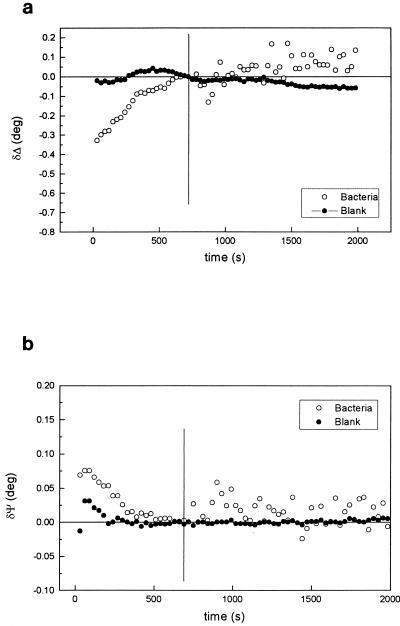

The corresponding changes of Δ and Ψ with time for titanium can be seen in Fig. 2. The refractive index of the metal was calculated in the same way as for Al-brass, and a complex refractive index for the substrate of ns = 2.49 − 3.09i was obtained. An ns value of 3.23 − 3.62i has been previously obtained at 632.8 nm for electropolished titanium in a sulfuric acid solution (39). The difference in the optical constants found in the present work could be accounted for by the surface coverage of the metal by TiO2.

FIG. 2.

Variations of Δ (a) and Ψ (b) during cathodic polarization of titanium in 3.5% NaCl in the absence (•) and presence (○) of bacteria. E = −0.6 V. The vertical lines show the times at which bacteria were added.

Formation of a bacterial film.

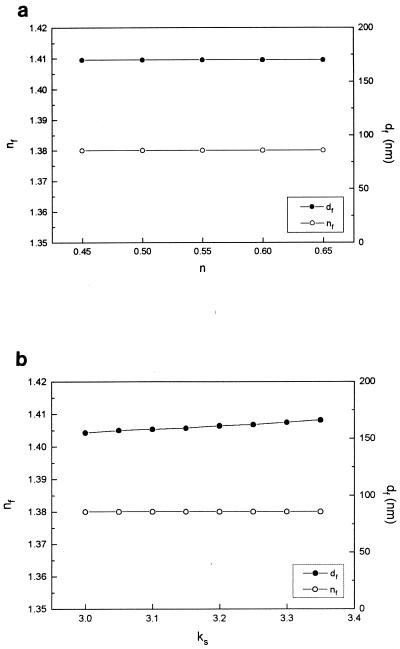

As can be seen in Fig. 1, Δ reaches an almost constant value when bacteria are present, whereas the slow formation of an oxide submonolayer is observed for the blank. The addition of bacteria to the solution causes changes in Δ and Ψ of approximately ∼0.15 and ∼0.05°, respectively, for Al-brass (Fig. 1). These changes fitted well a single-film model for a transparent film (with a value of kf, the imaginary component of the film refractive index [3] of 0 at 632.8 nm) (34) with an effective thickness for a film (df) of 160 nm and an effective refractive index for a film (nf) of 1.38. The sensitivities of the calculated values of df and nf to the optical constants of the substrate used in the calculations are shown in Fig. 3 for different values of ns. No significant changes in the calculated values of nf or df for the bacterial film are observed for a wide range of optical constants of the substrate. Only ks has a minor effect on the calculated film thickness, and it can be concluded that the bacterial film thickness is 160 ± 10 nm. Similar results were obtained with titanium.

FIG. 3.

Influence of the substrate optical constants on the calculated bacterial film refractive index and thickness for ks = 3.35 (a) and ns = 0.645 (b).

It is recognized that the initial step of bacterial adhesion to solid surfaces is a reversible adsorption phase (6, 21, 31, 32, 45). The DLVO theory predicts a secondary energy minimum suitable for reversible adsorption (6, 32, 45) which is the result of the balance between long-range attractive forces and the repulsive overlap between the ionic double layers of the charged interacting surfaces. In these experiments the metal surface is negatively charged since the potential of zero charge for copper in chloride solutions is −0.26 V (SCE), i.e., it is very positive with respect to the potential of −0.6 V maintained during the adsorption experiments (42). The bacteria also carry a negative charge on the cell wall (9) and therefore will experience an electrostatic repulsion on approaching the metal surface. However, the high-salt concentration used places the secondary energy minimum very close (∼0.5 nm) to the surface, thus allowing bacterial adsorption to take place in spite of short-range electrostatic repulsion (45). These phenomena are well known from colloidal chemistry (1, 46). Figure 1 and subsequent analysis (see below) also indicate that bacterial adsorption occurs on a submonolayer oxidized surface (8).

Optical model for the bacterial films.

It is proposed that the observed changes in Δ and Ψ are a consequence of the adsorption of a bacterial layer, and in order to validate this assumption a model describing the changes in the interfacial optical properties due to bacterial attachment was considered. Coverage of the metal surface can be calculated assuming a layer of constant thickness and variable refractive index (44). The cells of the Pseudomonas sp. strain used are rod shaped and can be regarded as cylinders of constant width, capped with hemispherical poles (11). Previous studies of Pseudomonas adsorption have shown that the cells are attached with an orientation either perpendicular or parallel to the surface, with no intermediate angles (18). Optical microscopy revealed a parallel orientation and the cell width was found to be approximately 1 μm. This was taken as the thickness of the bacterial film layer, and its refractive index was calculated by using an effective medium theory. Since the filling factor, i.e., the volume fraction of bacteria in the interfacial film volume, as observed by optical microscopy (see below) is very low, the simple Maxwell-Garnett approximation corresponding to noninteracting particles can be used for modeling the optical properties of the film. The nf for a film consisting of particles immersed in a medium of refractive index nm is given as follows (2):

|

1 |

where f is the filling factor, i.e., the volume fraction of particles with a refractive index for suspended bacteria (nb) present in the film. nm represents the refractive index of the other film component, which in the present case has been taken as the bulk solution.

Morel et al. (34) showed that the real component of nb is 1.05 times the refractive index of the surrounding solution. A more recent study by Walthman et al. (47) gave a value for nb of (1.064 ± 0.015) nm, from which an average nb of 1.47 ± 0.02 was estimated. The imaginary component of the index to be considered is negligible (34). From this and the nf value of 1.38 fitted to the data of Fig. 1, a filling factor corresponding to a coverage of 17% ± 4% was obtained from equation 1. This is equivalent to an average film thickness of 174 nm, a result in good agreement with the previous calculation of df = (160 ± 10) nm obtained assuming a uniform film. The difference between the two calculations is that a more detailed model has been considered in the former, using an independent estimate of the refractive index of the bacteria. To confirm these values, the coverage was measured at the end of the ellipsometric experiments using photographs (×1,000) from an optical microscope. Coverages ranging from 12 to 16% were obtained, which are in good agreement with the filling factors calculated from the ellipsometric data. Thus, the three approaches used, simple average film thickness considerations directly fitted from ellipsometric data, an effective medium model, and direct microscopical observations, lead to similar results, giving confidence in the use of ellipsometry to monitor bacterial attachment to metal surfaces.

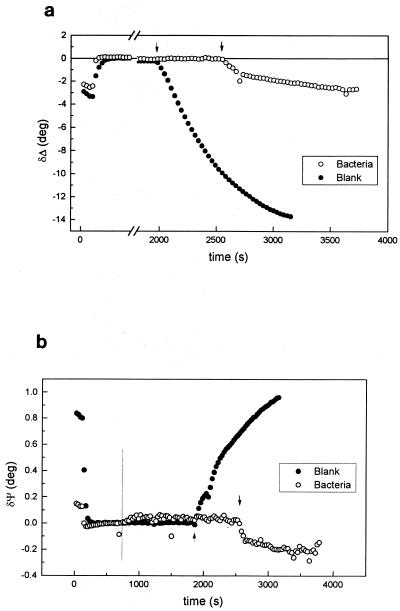

Effect of bacteria on oxide formation.

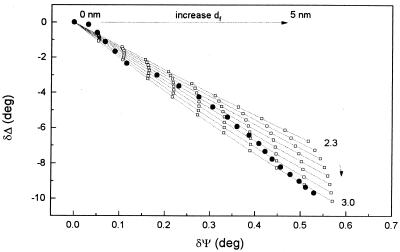

In order to investigate the influence of the presence of bacteria at the metal-solution interface on oxide film formation, bacterial growth on Al-brass was monitored at the end of each experiment by allowing the sample to reach the corrosion potential where oxide film growth is known to occur (41). The results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 4. In the absence of bacteria a strong decrease in Δ accompanied also by an increase in Ψ are indicative of the rapid formation of an oxide film at the corrosion potential (12). The dependence of Δ on Ψ could not be fitted to a single-film model with a constant nf value. Figure 5 shows a comparison between the observed changes of Δ and Ψ (filled points) and theoretical calculations obtained using a one-oxide film model; the effect of variations of nf and df on the Δ-Ψ signature are also shown. This is a convenient way of visualizing the variations of ellipsometric angles for different refractive indices and film thicknesses. It can be seen in this figure that the experimental Δ-Ψ signature is comprised within an envelope of values for nf between 2.3 and 3 and an oxide film thickness from 0 to 5 nm. kf was taken as zero (26). The optical constants for the Al-brass substrate were the same as those used above. It is noteworthy that an increment in the value of nf was observed during the growth of the film (Fig. 5). This can be related to different time-dependent growth rates of the oxides of the alloying metals. During the initial oxide growth period zinc is preferentially oxidized (28) and the variations of Δ and Ψ are primarily due to the formation of a ZnO layer (nf = 2.019) (48). The later growth of Cu2O (n = 2.8) (8) into this oxide film leads to the observed increase in the value of nf.

FIG. 4.

Variations of Δ (a) and Ψ (b) with the growth of an oxide film on Al-brass in 3.5% NaCl at the free corrosion potential in the absence (•) and presence (○) of bacteria. Arrows indicate the times when the potential was allowed to reach its free corrosion value. The vertical line in b shows the time at which bacteria were added.

FIG. 5.

Variations of Δ and Ψ with the growth of an oxide film on Al-brass in 3.5% NaCl. •, experimental data (from Fig. 4) from the initial phase of oxide growth at the free potential; □, calculated data (16) for nf values of 2.3 to 3.0 in 7 steps (the arrow indicates the direction of increase) and for df values of 0 to 5 nm in 10 steps. kf = 0.

Figure 4 shows that there are two distinct oxide growth rates at the corrosion potential in the presence of adsorbed bacteria. During an initial oxide growth phase of ∼170 s at the corrosion potential, a fast decrease of Δ is observed; this is followed by a further slow decrease at longer times. The rate of decrease of Δ is proportional to the oxide film growth kinetics (8), and from a comparison of the oxide growth with and without bacteria, it is apparent (Fig. 4a) that oxide growth is inhibited by the presence of bacteria. The rate of oxide formation at the free corrosion potential is controlled by the concentration of electroactive species in solution constituting the cathodic reaction of the corrosion couple. For copper alloys in chloride solutions the latter is the reduction of oxygen (14, 15), and the lower oxide growth rate observed can therefore result from the lower oxygen concentration present at the surface as a consequence of cell respiration both in the solution and within the absorbed layer. Both effects should be considered; the first would certainly decrease the amount of O2 available for the corrosion reaction. The second proposal relates to the well-known behavior of ultramicroelectrodes and reaction centers at surfaces in electrochemical systems (19, 40). Although the coverage is less than 1/5 of the total surface, the nature of the diffusional fields of O2 must be taken into account. The bacteria adsorbed on the surface behave like ultramicroelectrodes for which hemispherical diffusional fields prevail. For this diffusional geometry the distance for which deprivation of electroactive reagent occurs is approximately five times the ultramicroelectrode diameter (40). Therefore, oxygen deprivation of the surface will take place with the consequent decrease of the rate of metal oxidation. In addition, local acidification can result from the metabolic activity of the cells, which would also lead to a lower oxide thickness.

The practical consequences of the above require further consideration. A model proposed for the structure of aerobic biofilms (13) describes a complex structure, consisting of microbial cell clusters and interstitial voids, which strongly influences oxygen distribution. In particular, the cathodic reaction becomes diffusionally controlled in this case (15). In addition, low-oxygen concentrations are present underneath the cell clusters (13). For this situation, the results in Fig. 4a and b suggest that the thickness of the passivating film under the cell clusters of a biofilm will be less than under the voids in the biofilm structure.

Significant changes were observed in the Ψ values during oxide film growth (Fig. 4b) in the presence of bacteria. In contrast with the increase in Ψ for the sterile control, a fast decrease in this angle was observed during the first 120 s at the corrosion potential, followed by a slower decrease, which is similar to that observed for Δ. It is important to note that, in general, Ψ increases and Δ decreases with the growth of a transparent oxide film (22). The decrease observed in Ψ is unusual considering that the calculations in Fig. 5 clearly show the growth of an oxide with the characteristic increase in Ψ and a slope dΔ/dΨ as predicted for kf = 0.

Irreversible bacterial adhesion.

It is proposed that the changes in the time dependence of δΔ and δΨ during the growth of the oxide film in the presence of bacteria (Fig. 4) are consequences of the change from reversible to irreversible in the adhesion of the cells to the surface undergoing oxidation. Ellipsometry is a very sensitive technique for the study of interfacial films and this behavior can be related to a small change in the number of bacteria present in the film, as calculated below. The Ψ signature for nonabsorbing films is determined by the refractive index of the films present, and Ψ variations in Fig. 4b must be related to a decrease in the value of nf for the bacterial film and/or that of the oxide layer. The influence of bacterial attachment and of oxide composition changes, or growth, will be analyzed separately since all these processes can take place.

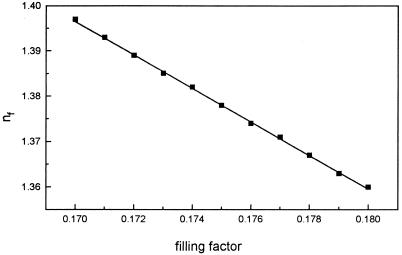

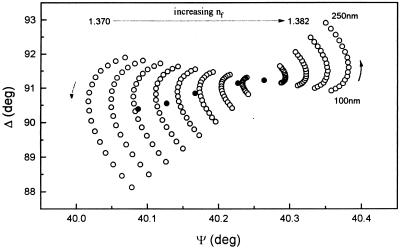

The refractive index of the bacterial film is very sensitive to the value of the filling factor (f), as is shown in Fig. 6 where a linear decrease of the calculated values of nf (equation 1) with an increase in f can be observed. A minor increase in the number of attached bacteria of less than 1% in f can produce a large decrease of the refractive index of the film due to the large film thickness being considered. The significance of such variations can be appreciated from the calculations shown in Fig. 7 where each point (open circles) corresponds to a different value of the bacterial film thickness and refractive index. Superimposed on these data are experimental δΔ and δΨ values obtained during the first 150 s after the metal is placed at the free corrosion potential in the presence of bacteria (Fig. 4). Considering only at first bacterial film changes, the experimental results could be an indication of a change in nf of ∼0.01 and a progressive increase in the average bacterial film thickness from the initial adsorption value of 160 to 190 nm. In this case, the changes in interfacial conditions (i.e., decreased electrostatic repulsion) when the metal is placed at the free potential induce an increase in the number of bacteria present in the film.

FIG. 6.

Variation of the effective refractive index for a bacterial film with the filling factor corresponding to the interfacial model in equation 1.

FIG. 7.

Δ-Ψ signature corresponding to a one-film model on Al-brass with nf values of 1.37 to 1.382 in 0.001 steps and df values of 100 to 250 nm in 10-nm steps (○) and experimental δΔ and δΨ values from the first 150 s at the free corrosion potential (•). The arrows indicate the direction of increase.

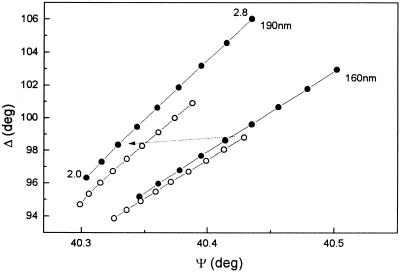

The decrease of Ψ (Fig. 4b) when bacteria are present can also be related to changes in the oxide layer. The presence of a Cu2O submonolayer during polarization at −0.6 V (8) was observed (Fig. 1a), but as was previously discussed, zinc oxide is preferentially formed during the initial oxide growth when the metal is allowed to reach its free corrosion potential (28). Changes in oxide layer composition after allowing the material to reach the free corrosion potential can account for the decrease in nf from the value corresponding to that of Cu2O (2.8) to a value that approaches that of ZnO (2.02). Figure 8 shows the Δ-Ψ signature for a two-film model when the refractive index of the oxide is decreased from 2.8 to 2.0, simultaneously with the optical changes introduced by an increase of the bacterial film thickness from 160 to 190 nm. The rationale for these calculations is the need to account for both a smaller decrease in Δ and a decrease, instead of an increase, in Ψ when comparing oxide growth in the presence and absence of bacteria. Although changes in oxide thickness will occur, the main features of the Δ-Ψ dependence can only be modeled on the basis of an oxide film with a bacterial layer attached on top of it. Any other combination leads to an actual increase in Ψ against experimental observations. The influence of an increase in the thickness of the oxide layer on the changes of Δ and Ψ is also considered in the analysis in Fig. 8 (filled circles). From these results it is proposed that the variations in Δ and Ψ when the metal is allowed to reach its corrosion potential (Fig. 4) are the product of at least two combined processes, the increase of the filling factor of the bacterial film (Fig. 6 and 7) and the decrease in the refractive index of the oxide layer due to its enrichment with ZnO (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Changes in the Δ-Ψ signature for a two-film model composed of a bacterial film (refractive index of 1.38, as previously found) over an oxide film on Al-brass. The values of nf for the oxide film are changed from 2.8 to 2.0 in eight steps and the calculations were carried out for bacterial film thicknesses of 160 and 190 nm. ○, 1-nm oxide film thickness; •, 1.5-nm oxide film thickness. The arrow indicates the direction of change of Ψ giving values comparable with the experimental results.

The full analysis of the unusual response of Δ and Ψ when the material is allowed to reach its free corrosion potential is obviously extremely complex and, with only two measured parameters, only general features can be depicted. It is quite clear, however, that the simple one-film model implied in the Δ-Ψ plane representation given in Fig. 7 is an oversimplification. A more physically realistic two-film model (Fig. 8) gives a better interpretation of the results, considering that the optical constants of all the film compounds and of the substrate are known. The calculated bacterial film thickness can only be regarded as tentative, although the microscopic observations give support to the values quoted.

Electrophoretic migration.

Irreversible adsorption of bacteria as predicted by the DLVO theory is only possible if the energy barrier determined by electrostatic repulsion does not exceed a few kT units (45). Four possible situations for irreversible adhesion have been described by van Loosdrecht et al. (45): (i) the surface is positively charged, (ii) both the metal and the bacterial surfaces are hydrophobic and carry a low surface charge density, (iii) a high concentration of electrolyte is present, and (iv) bacteria have special surface appendages that can bridge the distance between the cell wall and the metal surface.

When the electrode is allowed to reach the free corrosion potential, the shift to positive potentials reduces the negative surface charge density of the metal. In addition, both the high ionic strength employed, which reduces the width of the electrical double layer, and a reversal of bacterial wall surface charge density, due to the presence of Cu(I) in the diffusional field close to the metal surface, can enhance irreversible adhesion. Collins et al. (9) reported a change in bacterial electrophoretic mobility to positive values in the presence of heavy metal ions such as Cu2+, Zn2+, and Ni2+ at neutral pH. The ability of bacteria to sense metal ions at considerable distances from a corroding electrode is very intriguing (16). Besides a biological chemotaxis mechanism previously discussed (16), adsorption of metal ions on the bacterial cell walls through coordination to surface groups can lead to charge reversal. To check this possibility cells were treated with 1 mM CuCl2 in 3.5% NaCl solution for 10 min and their behavior on titanium was studied by ellipsometry. Titanium was used in preference to the Cu alloy to avoid the presence of copper metal ions due to metal corrosion. It was expected that by using this approach the influence of bacterial charge effects on the attachment rate could be observed. Cells extracted after treatment with CuCl2 showed a similar viability to that of untreated cells. Similar survival resistances to surface coordination by heavy metal ions leading to charge reversal have been observed for other bacteria (10).

Figure 9 shows the results of these experiments after addition of bacteria at −0.6 V. These results have to be compared with those obtained in the absence of bacteria (Fig. 2). A large linear decrease in Δ and a corresponding increase in Ψ were observed. In these Cu(II) surface-derivatized bacterial preparations the cell walls bear a net positive charge (9). Although a full analysis is not possible at present and a biological process might be operative, the increased rate of adsorption of Cu-treated bacteria on the surface indicates that electrophoretic migration can represent an important mechanism by which bacteria are attached to the metal surface. Similar charge effects have been proposed by Jucker et al. for the adhesion of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia 70401 to negatively charged glass surfaces (27).

FIG. 9.

Variations of Δ (a) and Ψ (b) during cathodic polarization of titanium in 3.5% NaCl in the absence (•) and presence (○) of Cu-treated bacteria. E = −0.6 V. The vertical lines show the times at which bacteria were added.

Conclusions.

The usefulness of ellipsometric techniques applied to the study of the formation of interfacial bacterial films has been highlighted. It has been shown that bacterial adhesion can be followed by this method and reliable information can be obtained by the use of an appropriate interfacial model. The experimental evidence indicates that bacterial adsorption occurs at polarized metal surfaces. From the ellipsometric results a coverage of adsorbed bacteria, in an orientation parallel to the surface, of 17% has been calculated, and these results have been confirmed from direct microscopic observations.

The kinetics of oxide growth is inhibited by the presence of bacteria. This is probably due either to local acidification at the bacterial film-metal solution interface or to the restricted diffusion of oxygen through the bacterial film, which results in a lower oxide film thickness. It is important to note that in practical applications differences in the thickness of the passivating film as a product of the unequal distribution of oxygen through a biofilm structure can lead to severe corrosion effects resulting from localized differential aeration of the corroding surface (13).

The rate of irreversible attachment of bacteria to metal surfaces can be increased by adsorption of metal ions on their surface walls, which results in charge reversal which both decreases the energy barrier for attachment and introduces an electrophoretic mobility component to the rate of surface colonization. These effects also occur during oxide growth at the free potential by the establishment of a metal ion gradient in the proximity of the corroding surface.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The financial support from The British Council (British Council-Fundación Antorchas program) for staff exchanges is gratefully acknowledged.

We thank Clementina Gomis Bas for help with the ellipsometric data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albery W J, Fredlain R A, O’Shea G J, Smith A L. Colloidal deposition under conditions of controlled potential. Faraday Discuss Chem Soc. 1990;90:223–234. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aspens D E, Theeten J B. Investigation of effective-medium models of microscopic surface roughness by spectroscopic ellipsometry. Phys Rev B. 1979;20:3292–3302. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azzan R M A, Bashara N M. Ellipsometry and polarized light. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: North Holland; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakke R, Olsson P Q. Biofilm thickness measurements by light microscopy. J Microbiol Methods. 1986;5:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busalmen, J. P., M. A. Frontini, and S. R. de Sánchez. Microbial corrosion: effect of the microbial catalase on the oxygen reduction. In F. C. Walsh and S. A. Campbell (ed.), Recent developments in marine corrosion. Royal Society of Chemistry, London, United Kingdom, in press.

- 6.Busscher H J, Weerkamp A H. Specific and non-specific interactions in bacterial adhesion to solid substrata. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1987;46:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butcher E C, Dyer A J, Gilbert N E. Ellipsometric measurements of oxide films on copper. Brit J Appl Phys. 1968;1:1673–1678. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ceré S, de Sánchez S R, Schiffrin D J. Potential dependence of the optical properties of the cooper/aqueous borax interface. J Electroanal Chem. 1995;386:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins Y E, Stotzky G. Heavy metals alter the electrokinetic properties of bacteria, yeasts, and clay minerals. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1592–1600. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.5.1592-1600.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins Y E, Stotzky G. Changes in the surface charge of bacteria caused by heavy metals do not affect survival. Can J Microbiol. 1996;42:621–627. doi: 10.1139/m96-085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper S. Bacterial growth and division. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1991. p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis B D, Dulbecco R, Eisen H N, Ginsberg H S, editors. Microbiology—1980. Philadelphia, Pa: Harper & Row; 1980. p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Beer D, Stoodley P, Roe F, Lewandowski Z. Effects of biofilm structures on oxygen distribution and mass transport. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1994;43:1131–1138. doi: 10.1002/bit.260431118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Sánchez S R, Schiffrin D J. Flow corrosion mechanism of copper alloys in sea water in the presence of sulphide contamination. Corros Sci. 1982;22:585–607. [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Sánchez S R, Schiffrin D J. The effect of pollutants in the corrosion of copper base alloys by sea water. Corrosion. 1985;4:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Sánchez S R, Schiffrin D J. Bacterial chemo-attractant properties of metal ions from dissolving electrode surfaces. J Electroanal Chem. 1996;409:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dexter S C. Biofouling and biocorrosion. Bull Electrochem. 1996;12:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Escher A, Characklis W C. Modelling of initial events in biofilm accumulation. In: Characklis W C, Marshall K C, editors. Biofilms. New York, N.Y: Wiley Press; 1990. pp. 445–486. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleischmann M, Pons S, Rolison D R, Schmidt P P, editors. Ultramicroelectrodes. Morganton, N.C: Datatech Systems Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fletcher M, Loeb G I. Influence of substratum characteristics on the attachment of a marine pseudomonad to solid surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;37:67–72. doi: 10.1128/aem.37.1.67-72.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frymier P L, Ford R M, Berg H C, Cummings P T. Three-dimensional tracking of motile bacteria near a solid planar surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6195–6199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.6195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greef R. Ellipsometry. In: White R E, Bockris J O’M, Conway B E, Yeager E, editors. Comprehensive treatise of electrochemistry. Vol. 8. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1980. pp. 339–369. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greef R. ELLGRAPH software. Southampton, United Kingdom: Optochem; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greef R. TDELPSI software. Southampton, United Kingdom: Optochem; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greef R. FILMFIT software. Southampton, United Kingdom: Optochem; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Habraken F H P M, Gijzeman O L J, Bootsma G A. Ellipsometry of clean surfaces, submonolayer and monolayer films. Surf Sci. 1980;96:482–507. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jucker B A, Harms H, Zehnder A J B. Adhesion of the positively charged bacterium Stenotrophomonas (Xanthomonas) maltophilia 70401 to glass and teflon. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5472–5479. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5472-5479.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim B S, Hoier S N, Park S M. In situ spectro-electrochemical studies on the oxidation mechanism of brass. Corros Sci. 1995;22:557–570. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Little B, Wagner P, Mansfeld F. An overview of microbiologically influenced corrosion. Electrochim Acta. 1992;37:2185–2194. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Little B J, Wagner P A, Characklis W G, Lee W. Microbial corrosion. In: Characklis W C, Marshall K C, editors. Biofilms. New York, N.Y: Wiley Press; 1990. pp. 635–670. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marshall K C, Cruickshank R H. Cell surface hydrophobicity and the orientation of certain bacteria at interfaces. Arch Mikrobiol. 1973;91:29–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00409536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall K C, Stout R, Mitchell R. Mechanism of the initial events in the sorption of marine bacteria to surfaces. J Gen Microbiol. 1971;68:337–348. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mollica A, Ventura G, Traverso E, Scotto V. Cathodic behavior of nickel and titanium in natural seawater. Int Biodeterior Bull. 1988;24:221–230. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morel A, Ahn Y H. Optical efficiency factors of free-living marine bacteria: influence of bacterioplankton upon the optical properties and particulate organic carbon in oceanic waters. J Mar Res. 1990;48:145–175. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller R H. Optical techniques in electrochemistry. Adv Electrochem Electrochem Eng. 1973;9:167–226. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naumann D, Helm D, Labischinski H. Microbiological characterization by FT-IR spectroscopy. Nature. 1991;351:81–82. doi: 10.1038/351081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nichols P D, Henson J M, Guckert J B, Nivens D E, White D C. Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopic methods for microbial ecology: analysis of bacteria, bacteria-polymer mixtures and biofilms. J Microbiol Methods. 1985;4:79–94. doi: 10.1016/0167-7012(85)90023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nivens D E, Chambers J Q, Anderson T R, Tunlid A, Smit J, White D C. Monitoring microbial adhesion and biofilm formation by attenuated total reflection/Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. J Microbiol Methods. 1993;17:199–213. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ord J L, De Smet D J, Beckstead D J. Electrochemical and optical properties of anodic oxide films on titanium. J Electrochem Soc. 1989;136:2178–2184. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scharifker B R, Mostany J. Three dimensional nucleation with diffusion controlled growth. J Electroanal Chem. 1984;177:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shanley C W, Hummel R E, Verink E D., Jr Differential reflectometry—a new optical technique to study corrosion phenomena. Corros Sci. 1980;20:467–480. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sokolowski J, Lzajkowski J M, Turowska M. Zero charge potential measurements of solid electrodes by inversion immersion methods. Electrochim Acta. 1990;35:1393–1398. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suci P A, Siedlecki K J, Palmer R J, Jr, White D C, Geesey G G. Combined light microscopy and attenuated total reflection Fourier transform spectroscopy for integration of biofilm structure, distribution, and chemistry at solid-liquid interfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4600–4603. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4600-4603.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tadjeddine A. Optical-response of the ideally polarizable electrode—application to the quantitative determination of the interactions in the interface. J Electroanal Chem. 1984;169:129–144. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Loosdrecht M C M, Lyklema J, Norde W, Zehnder A J B. Bacterial adhesion: a physicochemical approach. Microb Ecol. 1989;17:1–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02025589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vold R D, Vold M J. Colloid and interface chemistry. London, United Kingdom: Addison-Wesley; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walthman C, Boyle J, Ramey B, Smit J. Light scattering and adsorption caused by bacterial activity in water. Appl Optics. 1994;33:7536–7540. doi: 10.1364/AO.33.007536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weast R C, editor. CRC handbook of chemistry and physics. 68th ed. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]