INTRODUCTION

Internal medicine (IM) residents often begin training with little prior outpatient medicine experience and are less comfortable treating ambulatory conditions than inpatient conditions.1–3 We developed, implemented, and evaluated an interactive intern ambulatory medicine bootcamp to improve early IM interns’ knowledge of core ambulatory topics.

METHODS

Residents at our institution spend one full-day in clinic weekly for 4 weeks, every other month. In our 3-year ambulatory curriculum, one clinical topic is presented as a 45-min case-based discussion during each clinic day. Following a literature review and needs assessment survey of faculty and senior residents at our institution, we identified six topics for inclusion in a bootcamp for early-year interns: diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, obesity, asthma, and COPD.

All categorical IM interns were excused from clinical duties to participate in the 7-h bootcamp in fall 2021. Six topics were presented over four sessions as a 10-min lecture followed by 40 min of case-based, small group discussion (Table 1). Faculty facilitators, all core ambulatory educators, received detailed answer keys in advance to guide discussion. Residents utilized partially completed handouts during each session to aid learning. Additional sessions were included in the bootcamp but knowledge related to these was not assessed (Table 1). Bootcamp participants provided feedback via a short questionnaire after participation.

Table 1.

Overview of the Topics, Learning Objectives, and Format for the Intern Ambulatory Bootcamp

| Topic and learning objectives | Format | |

|---|---|---|

| Morning schedule 8am–12 pm |

Type 2 diabetes 1. Describe how to choose an “A1C goal” 2. Name the screening tests needed for all patients with DM2 3. Identify key side effects of DM2 treatments 4. Identify how DM2 treatments impact risks of ASCVD, CHF, and DKD 5. Describe an algorithm for selecting medications for treatment of DM2 |

10-min lecture 40-min small-group discussion |

|

Hyperlipidemia and hypertension 1. Recognize the diagnosis of hypertension based on 2018 ACC/AHA criteria 2. Name strategies for non-pharmacologic blood pressure management 3. Apply knowledge of preferred blood pressure agents to individual patients 4. Identify screening guidelines and diagnosis of hyperlipidemia 5. Demonstrate choice of appropriate cholesterol management strategies |

10-min lecture 40-min small-group discussion |

|

|

Obesity management 1. Name five pillars of weight management 2. Assist patients in setting attainable weight loss goals 3. Counsel patients on diet, exercise, and behavioral interventions 4. Name four FDA-approved weight loss medications and list the main side effects and contraindications for each one 5. Demonstrate the ability to choose appropriate weight loss medications 6. Identify uses and benefits of very low calorie diets |

10-min lecture 40-min small-group discussion |

|

|

“Jeopardy”—vaccinations and cancer screening Jeopardy-style question and answer format Excluded from knowledge assessment |

60 min | |

|

Lunch with senior residents—Clinic Q + A Excluded from knowledge assessment |

60 min | |

| Afternoon schedule 1 pm–3 pm |

COPD and asthma 1. List the treatment options according to the different GOLD groups 2. Describe potential risks/benefits of inhaled corticosteroid use in COPD, and identify individuals for whom inhaled corticosteroids are indicated 3. List available non-pharmacologic treatments for COPD 4. Describe the diagnostic approach when there is concern for asthma despite normal baseline spirometry 5. Describe the step-wise approach for asthma treatment 6. Compare and contrast the asthma treatment approach with the COPD treatment approach, and identify key differences |

10-min lecture 40-min small-group discussion |

|

Knee exam 1. Develop an approach to history and physical examination for knee pain 2. Appropriately employ provocative maneuvers in the knee examination to differentiate common causes of knee pain 3. Discuss 4 common causes of knee pain Excluded from knowledge assessment |

Interactive 60-min workshop |

ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; DM2, type 2 diabetes; FDA, Federal Drug Administration; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

Four months after the bootcamp, interns completed a knowledge assessment containing 20 MKSAP questions, 16 of which corresponded to the six bootcamp topics and were included in our final analysis. Four questions on pain management were excluded from the analysis as this topic was not included in the bootcamp due to time constraints. We also included questions pertaining to primary care experiences in medical school. We compared intervention intern knowledge scores with those of a historical control group of interns at the same timepoint during the prior academic year who participated in standard ambulatory education and took an identical 20-item MKSAP test. Total knowledge scores (based on the 16 questions covered in the bootcamp) and topic-specific scores were calculated as the percentage of correct responses. Scores were compared between intervention and historical control groups using two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum tests (SAS 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) with significance at p < 0.05. Regression analysis evaluated predictors of differences in performance between the groups, adjusting for gender, participation in the residency generalist track, and time since last outpatient medical school rotation. This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Thirty-six of 51 interns (71%) participated in the bootcamp, of which 32 (89%) participants completed the post-bootcamp feedback questionnaire. All participants rated training quality as very good (4) or excellent (5) on a 1–5 scale.

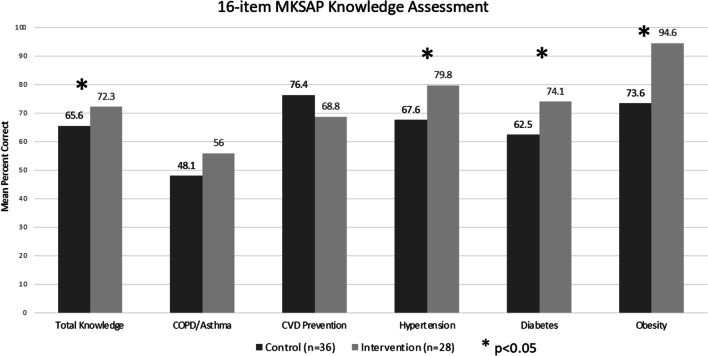

Twenty-eight of 51 (55%) interns in the intervention group attended the bootcamp and completed the knowledge assessment. Thirty-six of 53 (68%) control group interns completed the knowledge assessment. The mean assessment score was significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group (72.3% vs 65.6% correct, p = 0.03), and significant differences in knowledge were seen in diabetes-, hypertension-, and obesity-specific questions (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1). Performance on four pain-management questions did not differ between groups (63.2% vs 65.8% correct, p = 0.70). In an adjusted regression analysis, receipt of the bootcamp training remained a significant predictor of improved performance on diabetes and obesity questions (p = 0.036, p = 0.006), but not others.

Figure 1.

Mean percent correct on a 16-question MKSAP knowledge assessment comparing intervention interns who participated in the educational bootcamp 4 months prior and control interns, who did not participate in the educational bootcamp but were at the same point in their educational training at the time of the assessment.

DISCUSSION

A 1-day bootcamp early in internship can improve knowledge of core ambulatory topics compared to standard ambulatory education. Bootcamp topics reflected high-yield and commonly encountered conditions. The bootcamp was easy to implement without supplemental funding, but required protected time for faculty and residents. Our multimodal educational approach included active learning principles.

Given the importance but underemphasis of outpatient training in medical school, innovative methods for improving early ambulatory knowledge are important.1,4 Esch et al. implemented a 2-day ambulatory bootcamp for early IM interns and demonstrated immediate post-curriculum knowledge improvement.5 We demonstrate that the bootcamp model can lead to knowledge gains 4 months after the intervention, suggesting a durable impact.

Our study is limited by the single institution approach and use of MKSAP questions as a proxy for clinical knowledge. Next steps include exploring the impact of similar training on higher order trainee and clinical outcomes. This model can be adapted at other institutions seeking to improve residents’ knowledge of ambulatory medicine.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to contributions to curriculum development and delivery: Drs. Allie Dakroub, Anita Ganti, Marc Gauthier, Sarah Jones, Agnes Koczko, Corinne Kliment, Sarah Merriam, and Ruth Preisner. Funding was provided by Division of General Internal Medicine Fellow and Faculty Award through the University of Pittsburgh Division of General Internal Medicine.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nath J, Oyler J, Bird A, Overland MK, King L, Wong CJ, Shaheen AW, Pincavage AT. Time for clinic: fourth-year primary care exposure and clinic preparedness among internal medicine interns. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(10):2929–2934. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06562-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sisson SD, Boonyasai R, Baker-Genaw K, Silverstein J. Continuity clinic satisfaction and valuation in residency training. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1704–1710. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0412-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiest FC, Ferris TG, Gokhale M, Campbell EG, Weissman JS, Blumenthal D. Preparedness of internal medicine and family practice residents for treating common conditions. JAMA. 2002;288(20):2609–2614. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.20.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pincavage AT, Fagan MJ, Osman NY, Leizman DS, DeWaay D, Curren C, Ismail N, Szauter K, Kisielewski M, Shaheen AW. A national survey of undergraduate clinical education in internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(5):699–704. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04892-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esch LM, Bird AN, Oyler JL, Lee WW, Shah SD, Pincavage AT. Preparing for the primary care clinic: an ambulatory boot camp for internal medicine interns. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:29702. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.29702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]