Abstract

Introduction: Educational attainment, widely used in epidemiologic studies as a surrogate for socioeconomic status, is a predictor of cardiovascular health outcomes.

Methods: A two-stage genome-wide meta-analysis of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), and triglyceride (TG) levels was performed while accounting for gene-educational attainment interactions in up to 226,315 individuals from five population groups. We considered two educational attainment variables: “Some College” (yes/no, for any education beyond high school) and “Graduated College” (yes/no, for completing a 4-year college degree). Genome-wide significant (p < 5 × 10−8) and suggestive (p < 1 × 10−6) variants were identified in Stage 1 (in up to 108,784 individuals) through genome-wide analysis, and those variants were followed up in Stage 2 studies (in up to 117,531 individuals).

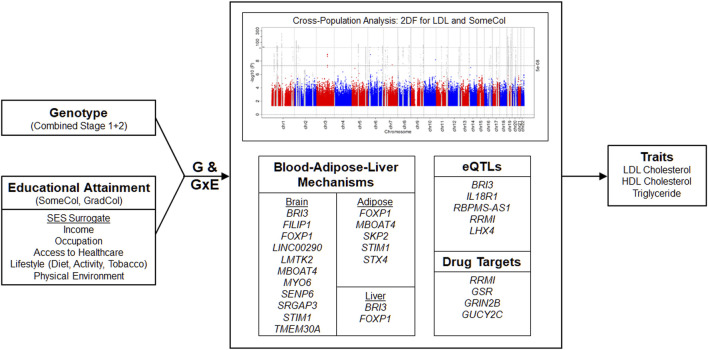

Results: In combined analysis of Stages 1 and 2, we identified 18 novel lipid loci (nine for LDL, seven for HDL, and two for TG) by two degree-of-freedom (2 DF) joint tests of main and interaction effects. Four loci showed significant interaction with educational attainment. Two loci were significant only in cross-population analyses. Several loci include genes with known or suggested roles in adipose (FOXP1, MBOAT4, SKP2, STIM1, STX4), brain (BRI3, FILIP1, FOXP1, LINC00290, LMTK2, MBOAT4, MYO6, SENP6, SRGAP3, STIM1, TMEM167A, TMEM30A), and liver (BRI3, FOXP1) biology, highlighting the potential importance of brain-adipose-liver communication in the regulation of lipid metabolism. An investigation of the potential druggability of genes in identified loci resulted in five gene targets shown to interact with drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration, including genes with roles in adipose and brain tissue.

Discussion: Genome-wide interaction analysis of educational attainment identified novel lipid loci not previously detected by analyses limited to main genetic effects.

Keywords: educational attainment, lipids, cholesterol, triglycerides, genome-wide association study, meta-analysis

1 Introduction

Educational attainment is widely used in epidemiologic studies as an index of socioeconomic status (SES) (Kaplan and Keil, 1993). Many studies have identified educational level and other indices of SES as predictors of health outcomes (Hamad et al., 2019), coronary heart disease (CHD) risk factors (Hamad et al., 2019), and lifestyle choices such as consumption of an atherogenic diet (Shea et al., 1993). Although educational level may not capture a holistic representation of SES (Braveman et al., 2005), higher educational attainment has been shown to have a positive impact on all-cause mortality (Kaplan and Keil, 1993) and cardiovascular risk traits (Leino et al., 1999) such as blood pressure and hypertension (Leng et al., 2015), coronary artery disease (Matthews et al., 1989), coronary calcification (Gallo et al., 2001), metabolic syndrome (Matthews et al., 1989), and lipid levels (Matthews et al., 1989; Metcalf et al., 1998). However, the mitigating effects of higher education on health outcomes are often attenuated in minoritized groups (Braveman et al., 2005; Assari and Bazargan, 2019), even after controlling for other indices of SES (Metcalf et al., 1998). This differential effect raises the possibility that interactions between educational attainment and genetics contribute to the association with health outcomes.

There has been relatively little focus on genetic interactions with educational attainment as determinants of health outcomes, particularly cardiovascular health, although genetic influences on education level itself (Okbay et al., 2016) have been explored. We have previously reported novel blood pressure loci by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that explicitly modeled genetic interactions with educational attainment (Basson et al., 2014; de las Fuentes et al., 2020). Other studies have identified evidence of gene-environment interactions for a variety of disease traits including neuropsychiatric disorders (Assary et al., 2018; Werme et al., 2021), systemic lupus erythematosus, (Woo et al., 2022), and lung function (Melbourne et al., 2022).

There has been no comprehensive assessment of interactions between genetic variation and educational attainment on lipid levels. Dyslipidemia, a leading contributor to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, exhibits significant disparity among population groups. Consideration of educational attainment as a genetic modifier may allow identification of novel lipid loci and offer insights into the biological mechanisms that may serve to identify new therapeutic targets. Here, by combining cohorts available in the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) Gene-Lifestyle Interactions Working Group (Rao et al., 2017), we performed genome-wide meta-analysis of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), and triglyceride (TG) levels while accounting for gene-educational attainment interactions, used as a surrogate for socioeconomic status.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participating studies

We performed analyses in two stages (Supplementary Figure S1). A total of 41 cohorts including 108,784 men and women (aged 17–80 years) from European (EUR), African (AFR), East Asian (EAS), Hispanic admixed (HIS), and Brazilian admixed (BRZ) populations contributed to Stage 1 genome-wide interaction analyses (Supplementary Table S1); populations were defined by individual cohorts. An additional 42 cohorts (Supplementary Table S2) including 117,531 individuals contributed to Stage 2 analyses of most promising genetic variants [mostly single nucleotide variants (SNVs), also including a small number of insertions and deletions (indels)] selected from Stage 1. Participating studies are described in the Supplementary Material. Each study obtained informed consent from participants and approval from the appropriate institutional and/or ethical review boards.

2.2 Lipid and educational attainment variables

Both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies were included. In longitudinal cohorts that had multiple clinic visits for each subject, a single visit was chosen that maximized the sample size. Three lipid traits were considered for analyses: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), and triglyceride (TG) (all mg/dL). LDL was directly assayed or calculated via the Friedewald equation (LDL = TC−HDL−[TG/5]) for those with fasting TG ≤ 400 mg/dL (Friedewald et al., 1972). If fasting TG > 400 mg/dL or if TG is non-fasting, LDL was set to missing unless directly assayed. LDL concentrations were adjusted for statin use as described elsewhere (Peloso et al., 2014). Either fasting or non-fasting HDL was acceptable for analysis. Non-fasting TG levels were set to missing. HDL and TG concentrations were natural log-transformed for analysis. Descriptive statistics for these lipid traits are presented in Supplementary Tables S3, S4. For educational attainment, two dichotomous variables were defined in a way that made it possible to harmonize the variable in most cohorts, thereby maximizing the sample size. The first variable, “Some College” (SomeCol), was coded as 1 if the subject received any education beyond high school (i.e., 12 years of combined primary and secondary education), including vocational school, and as 0 if no education beyond high school. The second variable, “Graduated College” (GradCol), was coded as 1 if the subject completed at least a 4-year college degree (i.e., post-secondary or tertiary education, at least 16 years of formal education), and as 0 for any education less than a 4-year degree. Subjects with missing data for lipid levels, educational attainment, or any covariates were excluded from analysis.

2.3 Genotype data

Genotyping was performed by each participating study using Illumina (San Diego, CA, United States) or Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA, United States) genotyping arrays. Imputation was performed using the 1000 Genomes Project (1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al., 2012) Phase I Integrated Release Version 3 Haplotypes (2010-11 data freeze, 2012-03-14 haplotypes) as a reference panel by most cohorts. Information on genotype platform and imputation for each study is presented in Supplementary Tables S5, S6 and as described in the Supplementary Material.

2.4 Analysis methods

Each study performed population-specific association analyses using the following Model 1 (joint model) that includes the effects of G, educational attainment, and their interaction (see below):

| (1) |

where Y is the lipid variable (LDL, HDL, or TG), “Education” is the educational variable (SomeCol or GradCol), and G is the dosage of the imputed variant coded additively from 0 to 2. The vector of adjustment covariates (C) includes age, sex, indicators of field center (for multi-center studies), and principal components (as many as deemed necessary by study personnel to adjust for population stratification). In addition, studies in Stage 1 performed association analysis using the following Model 2 that includes the effects of G and educational attainment (but not their interaction):

| (2) |

For model 1, each study provided the estimated variant effect (βG), estimated variant-educational attainment interaction effect (βGE), their robust standard errors, and a robust estimate of the covariance between βG and βGE. We considered the 1 degree of freedom (DF) test of the interaction effect (βGE) and 2 DF joint test of both variant (βG) and interaction effects (βGE) (Kraft et al., 2007). Population-specific and cross-population inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis was performed for the 1 DF test and joint 2 DF test (Manning et al., 2011), both using METAL (Willer et al., 2010). In Stage 1, EUR, AFR, EAS meta-analyses, variants were included if they were available in more than 5,000 samples or at least 3 cohorts (these filters were not applied to BRZ or HIS because of the limited number/size of the available cohorts included in these meta-analyses). We applied genomic control correction (Devlin and Roeder, 1999) twice in Stage 1, first for study-specific GWAS results and again for meta-analysis results. Genome-wide significant (p < 5 × 10−8) and suggestive (p < 1 × 10−6) variants in Stage 1 were taken forward into Stage 2 analysis. Genomic control correction was not applied to the Stage 2 results as association testing was performed for only selected variants. Results presented reflect meta-analyses combining Stages 1 and 2. Loci were defined by physical distance (±1 Mb around the lead variant of the respective locus).

Extensive quality control was performed, as described in the Supplementary Material. For Stages 1 and 2, to remove unstable study-specific results that reflected small sample size, low minor allele count (MAC), or low imputation quality, we excluded variants for which the “approximate DF” (defined as the minimum of [MAC0, MAC1] × imputation quality) < 20, where MAC0 and MAC1 are the MAC in the two educational attainment strata per exposure variable.

2.5 Characterization of functional roles

Loci were characterized as known (previously reported, as defined in the Supplementary Methods) or novel. A suite of tools implemented in Functional Mapping and Annotation (FUMA) of Genome-Wide Association Studies (Watanabe et al., 2017) (version 1.3.5; described in detail in the Supplementary Material) were used to identify functional roles for the lead variants and nearby variants in linkage disequilibrium (LD; r2 ≥ 0.2) in each of the novel lipid loci. LD information was obtained from the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 3 reference genome for the population with the most significant population-specific association. If the most significant association was in cross-population analyses (CPA), the reference genome for “1000G Phase 3 ALL” was used (Ward and Kellis, 2012). Two lead insertion/deletion loci were not identified in the reference genomes by FUMA and therefore not detailed. Nearest gene annotations were limited to protein coding, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) within 10 kb of lead variants and variants in LD (r2 ≥ 0.2) with the lead variant (Wang et al., 2010).

For the lead and LD variants, we used FUMA to report the RegulomeDB score, Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) scores, the 15-core chromatin state (ChromHMM), and expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs). Using nearest-gene annotations, FUMA was used to generate tissue-specific gene expression data (GTEx V8 dataset, 53 tissue types).

3 Results

3.1 Overview

We performed a two-stage meta-analysis of gene-educational attainment interactions on lipid traits considering two educational attainment variables, as previously described (Supplementary Figure S1) (de las Fuentes et al., 2020) Herein, we report our findings based on up to 227,850 individuals from five populations. In Stage 1, we pursued genome-wide interrogation in 108,784 individuals of European (EUR; n = 80,379), African (AFR; n = 12,295), East Asian (EAS; n = 11,002), Hispanic/Latino admixed (HIS; n = 1,455), and Brazilian admixed (BRZ; n = 3,653) populations (Supplementary Table S1). We performed genome-wide meta-analyses of approximately 18.8 million SNVs and indels variants imputed using the 1000 Genomes Project reference panel (QQ plots, Supplementary Figures S2A–E). Through the 1 DF test of the interaction effect and the 2 DF joint test of the SNV and interaction effects, we identified 13,851 genome-wide significant (p < 5 × 10−8) and 6,835 suggestive (p < 1 × 10−6 and ≥5 × 10−8) variants in known or novel loci that were associated with any lipid trait in any population or educational attainment analysis. These were followed-up in 117,531 additional individuals of EUR (n = 92,690), AFR (n = 6,630), EAS (n = 6,589), and HIS (n = 11,622) populations in Stage 2 (Supplementary Table S2).

We then performed meta-analyses combining Stages 1 and 2 (Figure 1; Manhattan Plots; Supplementary Figures S3A–F) and identified 128 significant loci (p < 5 × 10−8): 18 were novel loci and 110 loci were known (previously reported) loci, although the specific index variant often varied based on population (Supplementary Table S7). The majority of the associations with known loci were detected for EUR (99 loci) and cross-population analyses (CPA; 107 loci), reflecting the European-centric composition of prior studies, although known loci were also detected for the other populations: AFR (20 loci), EAS (15 loci), BRZ (3 loci), and HIS (22 loci). Four LDL and five HDL known loci were only identified by CPA. Eight of the 110 known loci were significantly associated with two lipid traits.

FIGURE 1.

Overview. A two-stage meta-analysis of gene-educational attainment interactions on lipid traits considering two educational attainment (a surrogate for socioeconomic status) was performed. Subsequently, a meta-analysis combining results of Stages 1 and 2 was performed to identify known and novel loci for lipid traits. Identified loci include genes with known or suggested roles in brain, adipose, and liver biology. Functional annotation, expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), and potential druggability of targets was explored. In the Manhattan plot, known and novel loci are depicted in gray and red/blue, respectively. GxE, gene-environment interaction; GradCol, graduated college; SES, socioeconomic status; SomeCol, some college.

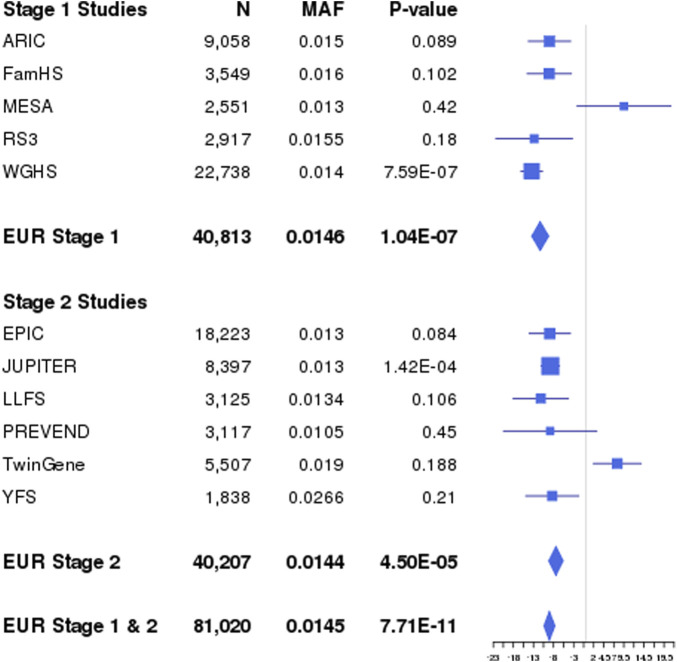

Across the lipid fractions, educational exposures, and populations, we identified 18 novel (p < 5 × 10−8) loci located at least 1 Mb away from any known lipid loci (Table 1) using the 1 DF and/or the 2 DF tests. Of these 18 loci, seven were identified by Stage 1 analyses only as Stage 2 analyses did not meet the filter threshold of an “approximate DF” ≥ 20. Among the 18 loci, one was identified only through 1 DF interaction-effect analyses (locus 6), 14 through 2 DF analyses, and three through both 2 DF and 1 DF interaction-effect only analyses (loci 4, 12, and 15). The four loci with significant 1 DF interaction effects include lead variants in or adjacent to forkhead box P1 (FOXP1), long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 290 (LINC00290), general transcription factor IIE subunit 2 (GTF2E2)-membrane bound O-acyltransferase domain containing 4 (MBOAT4), and stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1). For example, at STIM1 (locus 15), we observed an opposite genetic effect between higher and lower education: the minor allele C was associated with a 0.14 mmol/L lower LDL in higher education (GradCol = 1), whereas it was associated with a 0.09 mmol/L higher LDL in lower education (GradCol = 0), for a combined interaction effect of −0.22 mmol/L (Figure 2).

TABLE 1.

Summary of novel loci.

| Locus | rsID a | Chr | Pos (hg19) | Coded allele | Coded allele Freq b | Beta0 c | Beta1 d | 2 DF P e | 1 DF G × E P f | N | Genes g | RefPop-trait-Exp h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rs139845754 | 1 | 180,258 167 | A | 0.052 | −0.101 | −0.06 | 3.40E-08 | 2.00E-01 | 10,913 | LHX4; RP5-11 80C10.2; ACBD6 ; XPR1; KIAA1614; STX6 | AFR-TG-SomeCol |

| 2 i | rs7567133 | 2 | 103,239 356 | C | 0.031 | 0.102 | 0.021 | 1.72E-08 | 1.16E-03 | 6,361 | IL1RL1; IL18R1; IL18RAP; SLC9A4; SLC9A2; MFSD9; TMEM182 | AFR-HDL-GradCol |

| 3 | rs79367750 | 3 | 9,096 107 | C | 0.096 | 1.251 | −10.279 | 3.99E-08 | 1.94E-04 | 8,855 | SRGAP3 | EAS-LDL-SomeCol |

| 4 i | rs147731578 | 3 | 70,605 665 | ATTATT | 0.018 | −0.145 | 0.034 | 1.39E-09 | 3.51E-09 | 15,584 | MITF; FOXP1 | EUR-HDL-SomeCol |

| 5 i | rs74620279 | 4 | 179,620 483 | C | 0.025 | −12.24 | 11.59 | 4.67E-08 | 1.39E-06 | 5,669 | SNORD65 | AFR-LDL-SomeCol |

| 6 | rs77249395 | 4 | 181,181 245 | G | 0.035 | 0.006 | −0.026 | 3.17E-06 | 2.41E-08 | 134,413 | LINC00290 | TA-HDL-GradCol EUR-HDL-GradCol |

| 7 i | rs11132093 | 4 | 182,664 815 | A | 0.061 | −1.65 | 15.84 | 5.04E-09 | 4.10E-07 | 2,809 | RP11-540E16.2; TENM3 | EAS-LDL-GradCol |

| 8 | rs190502162 | 5 | 37,160 808 | C | 0.013 | 9.266 | −0.715 | 3.35E-08 | 4.04E-07 | 48,467 | SKP2; NADK2; RANBP3L; SLC1A3; NIPBL; CPLANE1 ; NUP155; WDR70; GNDF | EUR-LDL-SomeCol |

| 9 | rs192718305 | 5 | 82,514 005 | G | 0.025 | 3.481 | 19.901 | 2.05E-08 | 1.60E-03 | 5,664 | RP11-343L5.2; TMEM167A; XRCC4 | AFR-LDL-SomeCol |

| 10 i | rs147892694 | 6 | 76,693 587 | G | 0.034 | −0.037 | −0.087 | 8.61E-09 | 1.20E-01 | 8,599 | TMEM30A; FILIP1; SENP6; MYO6; IMPG1 | AFR-HDL-SomeCol |

| 11 | rs7015 | 7 | 97,920 623 | A | 0.203 | −1.142 | −0.526 | 4.56E-08 | 6.18E-02 | 157,929 | LMTK2; TECPR1; BRI3 ; BAIAP2L1; NPTX2 | CPA-LDL-SomeCol |

| 12 j | rs77655002 | 8 | 30,437 023 | C | 0.042 | −9.97 | 10.73 | 5.52E-09 | 7.65E-08 | 7,166 | MBOAT4; RBPMS-AS1; RBPMS; GTF2E2 ; GSR; TEX15 | AFR-LDL-GradCol CPA-LDL-GradCol |

| 13 | rs144190766 | 10 | 108,927 076 | C | 0.03 | −0.015 | −0.103 | 2.52E-08 | 5.64E-03 | 9,677 | SORCS1; RNA5SP326 | AFR-HDL-SomeCol |

| 14 | rs116562538 | 10 | 129,845 329 | A | 0.028 | −4.573 | −9.049 | 6.79E-09 | 4.82E-02 | 20,939 | PTPRE | CPA-LDL-SomeCol |

| 15 | rs35287906 | 11 | 4,041 010 | C | 0.014 | 3.405 | −5.247 | 1.53E-09 | 7.71E-11 | 81,020 | PGAP2; RHOG; STIM1 ; RRM1; OR55B1P; RP11-23F23.3 | EUR-LDL-GradCol |

| 16 | rs11230661 | 11 | 55,451 313 | A | 0.185 | 0.01 | 0.007 | 3.15E-10 | 3.90E-01 | 151,320 | TRIM48; TRIM51; 87 Olfactory Receptor Genes; APLNR | EUR-HDL-GradCol EUR-HDL-SomeCol |

| 17 i | rs148063115 | 12 | 14,221 135 | T | 0.026 | 0.022 | 0.222 | 4.86E-08 | 4.35E-03 | 6,168 | GRIN2B; RP11-72J9.1; RP11-298E10.1; RN7SL676P; GUCY2C | AFR-TG-GradCol |

| 18 i | rs190746034 | 13 | 101,418 063 | G | 0.022 | −0.002 | −0.158 | 1.26E-08 | 1.06E-05 | 6,361 | RP11-151A6.4; TMTC4; NALCN-AS1 ; ARF4P3 | AFR-HDL-GradCol |

Notes:

rsID, based on dbSNP, build 146.

Coded allele frequency.

Effect size (beta) of the unexposed group.

Effect size (beta) of the exposed group.

GWAS, 2 DF p-value of the significant lead SNP, for this locus.

GWAS, 1 DF, genetic-educational attainment interaction p-value of the significant lead SNP, for this locus.

Nearest gene of all SNVs, in LD (r2>0.2) with lead variant; if SNV, not in FUMA, gene or nearest flanking coding genes noted. Bolded genes reflect intragenic lead SNV.

The reference panel used in FUMA, to obtain functional annotations-trait-exposure; if more than one RefPop-Trait-Exp listed, the data provided is for the more significant association which is listed first.

Only significant in Stage I analyses.

2DF p = 1.83E-08, 1 DF G×E p = 4.14E-08 in CPA-LDL-GradCol analyses.

AFR, african population; EAS, east asian population; EUR, european population; GradCol, graduated college; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; CPA, cross-population analyses; TG, triglyceride.

FIGURE 2.

Interaction effects of Locus 15 (rs35287906; STIM1) identified through combined Stage 1 and Stage 2 interaction effects with GradCol for LDL in EUR and CPA. Forest plots show β values (95% confidence intervals) and p-values (1 DF) for the rs35287906 × GradCol interaction term in linear regression models of LDL adjusted for age, sex, field center (for multi-center studies), and principal components. Results shown are for each EUR study, as well as the population-specific combined Stage 1 and 2 meta-analysis results. The interaction effect βG Educ corresponds to the difference in genetic effects between higher (βG1 = −5.25 mg/dL per minor allele) and lower education (βG0 = 3.41 mg/dL per minor allele), for a combined interaction effect of −8.66 mg/dL. AF, coded allele frequency; N, sample size.

Among the 18 novel loci, nine were found in LDL analyses, seven in HDL analyses, and two in TG analyses; none of the novel loci reached genome-wide significance for more than one lipid trait. Considering the 17 novel loci that were significant in 2 DF tests, six loci were identified considering “Graduated College” (GradCol), 10 were identified considering “Some College” (SomeCol), and one locus was significant for both “Graduated College” and “Some College” (locus 16). Examining the 17 loci for evidence of support for the non-significant educational attainment exposure (Supplementary Table S8), nine loci had at least nominal significance (p < 0.05; loci 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, 14, and 17), four did not have at least nominal significance (p ≥ 0.05; loci 10, 12, 15, and 18), and three did not have data available for the other educational attainment exposure trait (loci 5, 9, and 13) because of failure to meet filter thresholds (i.e., ≥20 copies of the minor allele in the exposed group).

The LocusZoom plots of these novel loci are presented in Supplementary Figure S4.

3.2 Ancestry-specific and cross-population analyses

Novel loci were identified through separate analyses of AFR (nine loci), EUR (three loci), EAS (two loci), CPA (two loci), and in both EUR and CPA (two loci). Among the 18 novel loci, two loci were identified only through CPA, as none of the population-specific analyses reached genome-wide significance. For example, the SNV (rs7015, locus 11) was only nominally associated with LDL in EUR (p = 3.04 × 10−4), HIS (p = 9.96 × 10−3), EAS (p = 1.99 × 10−2), and AFR (p = 2.81 × 10−2). However, in cross-population analysis combining these four populations, the association reached genome-wide significance (p = 4.56 × 10−8). This SNV resides in the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of an alternatively expressed transcript of brain protein I3 (BRI3).

3.3 Functional annotation and eQTL evidence

To obtain functional annotations for the lead variants and nearby variants in linkage disequilibrium (LD; r2 ≥ 0.2), we used FUMA (Watanabe et al., 2017). Among the 18 lead variants representing our novel loci, eight variants were intronic to coding genes, one variant was exonic to a non-coding RNA (ncRNA), one variant was intronic-ncRNA, one variant was in a 3′UTR, and five variants were intergenic; two additional variants were indels without available annotation in FUMA. Of the 1,733 annotated variants that include both the lead variants and variants in LD (r2 > 0.2) with available FUMA functional annotation, the majority were intergenic (64%). Among those variants annotated to gene regions (n = 619), 72% were intronic. 8.2% were exonic, and the remaining variants were in UTR and flanking regions (Supplementary Table S9).

Of the 1,769 LD variants, 25 had RegulomeDB scores better than or equal to 3a (17 in AFR, three in EUR, and five in CPA loci), suggesting at least moderate evidence for involvement in transcription regulation (Supplementary Table S9). Sixty-five variants have CADD scores ≥10, representing the top 10% of predicted deleteriousness for SNVs genome-wide (35 in AFR, 22 in EUR, three in EAS, and five in CPA loci). Eight variants in the Chromosome 11 locus including an olfactory receptor cluster have CADD scores ranging 21.2–37.0, placing them in the top 1% of predicted deleteriousness. Two additional variants are notable for high CADD scores, an exonic variant in glutathione-disulfide reductase (GSR; CADD score 25.5) and a variant in the BRI3 3′UTR region (CADD score 21.4).

The 15-core chromatin state (ChromHMM) was assessed for 127 epigenomes in the 16 lead variants available in FUMA (Supplementary Table S9). Of the lead variants, two had histone chromatin markers consistent with active or flanking active transcription start sites, and three were in regions associated with strong transcription in relevant tissues including brain, adipose tissue, and liver. Among all 1,769 LD variants, 91 had histone chromatin markers characteristic of active or flanking active transcription start sites, 218 had markers consistent with strong transcription, and 57 were in enhancer regions. Among the LD variants, those in five loci were identified as being highly significant cis-acting expression trait loci (eQTLs) in the GTEx V8 database: 65 variants in BRI3 (including index rs7015 SNV in locus 11) expressed in liver [false discovery rate (FDR) p-values 2.27 × 10−24], subcutaneous adipose tissue (FDR p-values 9.46 × 10−50), and brain (FDR p-values range 3.75 × 10−18 to 5.82 × 10−19); eight SNVs in interleukin 18 receptor 1 (IL18R1; including index SNV rs7567133 in locus 2) expressed in brain (FDR p-values range 8.30 × 10−20 to 5.89 × 10−36) and subcutaneous adipose tissue (FDR p-values 4.48 × 10−7); one SNV in RBPMS antisense RNA 1 (RBPMS-AS1; locus 12) expressed in subcutaneous adipose tissue (FDR p-value 5.71 × 10−28); seven SNVs in ribonucleotide reductase catalytic subunit M1 (RRM1; locus 15) expressed in subcutaneous adipose tissue (FDR p-values 1.36 × 10−44), and three SNVs in LIM homeobox 4 (LHX4; locus 1) expressed in brain (FDR p-values 8.73 × 10−10) and subcutaneous adipose tissue (FDR p-values range 1.36 × 10−9 to 4.50 × 10−13).

3.4 Druggability targets

The potential druggability of the identified gene targets was investigated using an integrative approach as previously described (Kavousi et al., 2022). We queried high- and medium-priority candidate gene targets using the Drug-Gene Interaction database (DGIdb), which identified 17 genes annotated as clinically actionable or members of the druggable genome (Supplementary Table S10). We identified eight genes with reported drug interactions and an additional four genes with active ligand interactions in the ChEMBL database. Among these, five gene targets were shown to interact with drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that have been evaluated in late-stage clinical trials using DrugBank and ClinicalTrials.gov databases (Supplementary Table S11). Among drug targets identified, RRM1 and GSR are both involved in glutathione metabolism and are targets of drugs used to treat various neoplasms; glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA type subunit 2B (GRIN2B) is involved in long-term neuronal potentiation; and guanylate cyclase 2C (GUCY2C) modulates gut cyclic GMP signaling. GRIN2B, which encodes a N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor GluN2B subunit, is a target of memantine, used to treat moderate to severe dementia in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. These results suggest that there are potential drug repurposing opportunities as novel therapies for lipid management.

4 Discussion

4.1 Overview

This study reports a genome-wide meta-analysis of data from up to 226,315 individuals from five population groups. In this study, educational attainment was used as a multidimensional surrogate of SES reflective of a variety of environmental factors such as occupation, wealth, access to quality healthcare, diet, lifestyle, and physical activity. We identified 18 novel loci for LDL, HDL, and TG at genome-wide significance when accounting for gene-educational attainment interactions. The majority of novel loci (nine of 18 loci) were identified in AFR, likely reflecting a lack of population diversity in prior large-scale genome-wide studies. Many of these novel loci include genes with biologic roles in adipose, brain, and hepatic tissue.

Adipose tissue serves a critical role in sequestering circulating free fatty acids as inert triglycerides lipid droplets. Processes that limit the differentiation or subsequent function of adipocytes may contribute to abnormal lipid metabolism. Adipose tissue is also an active endocrine organ that elaborates a variety of adipokines (Ahima, 2006), such as tissue necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), interleukins (IL)-6, IL-1, leptin, adiponectin, and others. Dysfunctional adipose tissue and pro-inflammatory adipokines can trigger ectopic deposition of fatty acids in other tissues, such as skeletal muscle and liver (Jung and Choi, 2014; Shulman, 2014), which can lead to a variety of metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, non-alcohol fatty liver disease, and dyslipidemia (Franssen et al., 2011; Jung and Choi, 2014). Increased hepatic fatty acid uptake stimulates synthesis of TG-rich very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol particles that are converted in the bloodstream to small-dense LDL particles through a process that also lowers circulating HDL (Bays et al., 2013). Whereas most of the LDL cholesterol is taken up again by the liver, a small fraction is removed from circulation by endocytosis via LDL receptors located in extrahepatic tissues, including the brain. Brain-adipose-liver communication pathways help maintain homeostasis by integrating peripheral metabolic signals; (Franssen et al., 2011; Gliozzi et al., 2021); miscommunication leads to central dysregulation and metabolic disorders (Yi and Tschop, 2012). For example, in rodents, insulin acts in the brain to enhance hepatic TG secretion via VLDL synthesis (Scherer et al., 2016). There is additional evidence to suggest that circulating plasma cholesterol concentration may play a role in neurodegeneration in susceptible individuals (Dietschy and Turley, 2001). A high-fat, high-cholesterol diet has also been associated with impaired cognition and memory (Ledreux et al., 2016) through mechanisms that may involve brain inflammation (Pistell et al., 2010).

4.2 Novel lipid loci include genes expressed in adipose tissue

Given the important role played by adipose tissue in regulating lipid metabolism, it is notable that two novel loci were identified that include genes with known roles in adipocyte differentiation and/or function. For example, syntaxin 6 (STX6; Table 1, locus 1, TG locus in AFR) has been shown to play a role in mediating insulin-stimulated translocation of the glucose transporter-4 (Glut4) in adipose tissue (Perera et al., 2003). After feeding, transgenic mice that overexpress Glut4 in adipose tissue show reduced activity of lipoprotein lipase (Gnudi et al., 1996), the rate-limiting step for clearing plasma TG (Wang and Eckel, 2009). S-phase kinase associated protein 2 (SKP2; locus 8, LDL locus in EUR) plays a role in adipocyte differentiation (Okada et al., 2009); transgenic Skp2 knock-out mice have a 50% reduction in both subcutaneous and visceral adipocyte numbers (Cooke et al., 2007).

4.3 Novel lipid loci include genes expressed in the brain

Nine novel lipid loci have been identified that include genes responsible for vital functions in the central nervous system. For example, the gene products of lemur tyrosine kinase 2 (LMTK2; locus 11, LDL locus in CPA) and myosin VI (MYO6; locus 10, HDL locus in AFR) both bind with kinesin-1 light chain in neurons to mediate axonal transportation of a wide variety of cargo including mitochondria and neurotransmitter-containing vesicles, and participate in glutamate receptor endocytosis on the pre-synaptic membrane (Li et al., 2020). Genes with similar functions are often clustered along chromosomes where shared regulatory domains mediate coexpression (Semon and Duret, 2006). Such may be the case for the locus on chromosome 6 (locus 10, HDL locus in AFR) where a series of genes are expressed in the hippocampus of the brain [transmembrane protein 30A (TMEM30A) (Xu et al., 2012), filamin A interacting protein 1 (FILIP1), (LoTurco and Bai, 2006), SUMO specific peptidase 6 (SENP6), (Loriol et al., 2013), and MYO6 (Tamaki et al., 2008)]. The hippocampus is responsible for consolidating short-term into long-term memory; modeling of interactions with educational attainment may have facilitated the detection of this novel locus. In murine models, knock-down of TMEM30A by small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) reduced neurite outgrowth in the hippocampus (Xu et al., 2012). The expression of FILIP1, which produces a negative regulator of filamin A, is required for appropriate neocortical cell migration (LoTurco and Bai, 2006). An LDL locus in EAS (locus 3) includes SLIT-ROBO Rho GTPase activating protein 3 (SRGAP3), a SLIT-ROBO activating protein that guides the growth of dendritic spines on cortical neurons (Blockus and Chedotal, 2014). Limited data from a candidate-gene association study also suggest that this locus is associated with total cholesterol, HDL, and apolipoprotein A1 in Maonan Chinese (Miao et al., 2017).

GRIN2B (locus 17, TG locus in AFR), which encodes a N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunit, is highly expressed in the hippocampus where it plays critical roles in memory consolidation. Murine models of aging show that transgenic overexpression of Grin2b improves learning and memory function (Cao et al., 2007). Notably, individuals with missense mutations in GRIN2B develop rare autosomal dominant forms of encephalopathy characterize by intellectual disability, impaired learning, and behavior phenotypes (Swanger et al., 2016; Fedele et al., 2018). Further preclinical and translational studies are warranted to determine the mechanisms by which interactions with educational attainment may modulate lipid levels in humans.

Some novel loci include several genes that are differentially expressed under a variety of conditions that may relate to altered environmental exposures in humans. For example, MYO6 (Tamaki et al., 2008) (locus 8, LDL locus in EUR) expression is upregulated in animal models of stress; and transmembrane protein 167A (TMEM167A; locus 9, LDL locus in AFR) is differentially expressed in the hippocampus of depressed murine models (Zhang et al., 2018). Of additional interest is the long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) LINC00290 (locus 6, HDL in CPA) which has been proposed as a “human-accelerated element” contributing to primate evolutionary shifts that lead to higher-order human capabilities such as complex language, advanced learning, and long-term planning (Kamm et al., 2013). Given evidence for expression in brain tissues, it is notable that the LINC00290 locus was only identified through interaction analyses with educational attainment.

4.4 Novel lipid loci include genes with roles in both adipose and brain tissues

There are four additional loci containing genes that have plausible biologic roles in both adipocyte function and in the brain. For example, in locus 12 (LDL locus in AFR), MBOAT4 has been called a “master switch” for the ghrelin system (Romero et al., 2010). Ghrelin, which is secreted by gastric endocrine cells, is made biologically active when acylated by MBOAT4. In addition to playing critical roles in adipogenesis, lipogenesis, and glucose homeostasis, ghrelin also stimulates food intake through actions in the brain (Pradhan et al., 2013). In locus 15 (LDL locus in EUR), the expression of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) negatively regulates adipocyte differentiation, impairing their ability to accumulate lipids (Graham et al., 2009). Stim1 is also a calcium sensor that plays a critical role in the formation of dendritic spines in developing murine hippocampal cells (Kushnireva et al., 2020). In transgenic mice, overexpression of Stim1 leads to improved contextual learning and decreased depression- and anxiety-like behaviors (Majewski et al., 2017). solute carrier family 1 member 3 (SLC1A3; locus 8, LDL locus in EUR) encodes a high-affinity glutamate reuptake channel in brain astrocytes that terminates excitatory neurotransmission; Slc1a3 knock-out mice have abnormal sociability (Zhou and Danbolt, 2014). SLC1A3 is also expressed in adipocytes, although its role in this tissue is not well understood (Krycer et al., 2017).

4.5 Gene with roles in adipose, brain, and liver tissues

Two loci contain genes with plausible biologic roles in adipose, brain, and hepatic tissues. In the brain, BRI3 (locus 11, LDL locus in CPA) has been implicated in neuronal survival following ischemia/reperfusion injury (Yang et al., 2015) and may be a protective regulator against Alzheimer disease (Matsuda et al., 2009). Several SNVs in this locus are significant eQTLs for BRI3 expression in both the liver and subcutaneous fat. A variant in BRI3 is notable for a CADD score predictive of being deleterious. FOXP1 (locus 4, HDL locus in EUR) is involved in adipocyte differentiation (Liu et al., 2019). In the brain, the transcription factor, FOXP1, heterodimerizes with its paralog, forkhead box P2 (FOXP2), to form a transcription factor; rare mutations in FOXP2 have been reported in multiple cases of intellectual disability and language impairment (Bacon and Rappold, 2012). In murine models of diabetes, hepatic FOXP1 expression, a regulator of gluconeogenic gene expression, is downregulated (Zou et al., 2015).

4.6 Limitations

Several limitations are inherent in the design of large-scale multi-population genome-wide association studies such as this one. First, we were unable to validate seven of the 18 novel loci (one EUR, one EAS, and five AFR), largely due to the limited number of non-EUR cohorts available in Stage 2 and variants/cohorts failing to meet quality control thresholds; these loci need further validation. Second, 16 of the 18 novel loci were notable for having minor allele frequencies <0.10 which increases the possibility for type 1 and type 2 errors. Third, the interpretation of educational attainment as a proxy for SES may vary according to gender, population, region, country, and/or birth cohort (Tyroler, 1989; Sorel et al., 1992; Kaplan and Keil, 1993; Metcalf et al., 1998) and dichotomization may fail to capture more nuanced population differences, in particular for non-minoritized populations. For example, in developing countries where diets are becoming progressively westernized, men and women from higher SES strata are at higher risk for dyslipidemia (Espirito Santo et al., 2019). Fourth, the practice of adjusting LDL concentrations for statin use is based on a method derived from a meta-analysis of largely European-population cohorts (Baigent et al., 2005) which may not be appropriate for other populations. Finally, genome-wide association studies are largely hypothesis generating in scope; findings of association warrant validation in biological systems. While we attempted to enhance potential relevance by reporting of functional annotation and druggability of candidate gene targets, biologic plausibility was extrapolated primarily from animal and in vitro data that may not be relevant in human lipid metabolism.

Despite these limitations, this study has multiple strengths such as a sufficiently large sample size of cohorts inclusive across the lifespan and sex and representing diverse populations, the majority which were not selected for lipid abnormalities. Furthermore, consideration of educational attainment is a novel strategy designed to enhance discovery of novel lipid loci. Whereas GWAS studies traditionally identify variants that explain only a fraction of trait variability, even loci associated with modest changes in gene expression or protein function may lay the groundwork for identifying novel drug targets and/or repurposing of existing drugs for lipid management.

4.7 Conclusions

In conclusion, this multi-population meta-analysis of LDL, HDL, and TG identified 18 novel loci by consideration of gene-educational attainment interactions; one locus was identified only through evidence for interaction with educational attainment. Several of the loci include genes with known or suggested roles in adipocyte, brain, and/or liver biology. While findings of gene-environment interactions have generally not yet been translated to clinical practice, the results of this study may identify novel potential therapeutic targets for lipid management, especially those involving central control of lipid metabolism.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of CAM, JMS, and DMB posthumously.

Funding Statement

This project was largely supported by two grants from the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the National Institutes of Health, R01HL118305 and R01HL156991. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health (AB). An NHLBI career development award (K25HL121091) enabled YS to play an important role on this project. The full set of study-specific funding sources and acknowledgments appear in the Supplementary Material.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: 83 US and international cohorts participated in this study, each subject to different regulations regarding sharing of data. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to LF, lfuentes@wustl.edu.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Washington University School of Medicine, Human Research Protections Office and by the appropriate institutional and/or ethical review board for each participating cohort (see Supplementary Material). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LF wrote the first draft of the manuscript. ARB, CLM, KLS, MRB, PBM, TWW, YJS contributed substantially to the revision of the manuscript and share first authorship. DKA, DCR, WJG, C-TL, ACM, JIR, MF share senior authorship of the manuscript. ACM, CAM, CB, CMB, CMD, CS, C-YC, DH, DIC, DMB, DWB, EB, EST, GG, GHa, GW, HJS, HS, IJD, JBJ, JIR, JMS, J-MY, KC, KEN, LEW, MAI, MF, MH, MKW, MMP, MS, NJS, NK, OTR, PKM, RM, RMD, RR, RSC, SCH, SEH, SFW, SKM, SLK, SSR, TAL, TF, TKR, TL, TR, TTP, TW, TYW, UF, VG, W-BW, W-PK, XS, XZ, and YXW participated in the study concept and design. ARB, AC, ACM, ACP, APe, ARH, AWM, BHS, BIF, BMP, BOT, BP, BS, CAM, CB, CGi, CHC, CMB, C-TL, CY, DH, DKA, DMB, DOM, DRW, DWB, DX, EBW, EL, ERF, EST, GHa, GW, HJS, HV, IJD, IR, JAS, JBJ, JDF, JEK, JIR, JM, DJR, JMS, J-MY, KC, KEN, KLe, KLi, LRY, LCS, MA, MRB, MC, MFF, MH, MK, MKW, MMP, MN, MRB, MS, MW, NJS, NV, OTR, PAP, PF, PH, PJS, PK, PKM, PMR, PWF, RM, RM, RMD, RR, RSC, SA, SCH, SEH, SFW, SKM, SLK, SP, SS, SSR, TE, TF, TL, TM, TR, TTP, UF, VF, VG, W-BW, W-PK, WZhe, XCha, X-OS, XZ, KL, YL, YM, and YXW participated in the phenotype data acquisition and/or quality control. ARB, ABZ, AC, ACM, ACP, AGU, ARH, BHS, BIF, BMP, BOT, CB, CCK, CDL, CGa, CKH, CPN, C-TL, CY, DEA, DIC, DKA, DMB, DOM, DRW, DX, EB, EBW, EL, F-CH, FG, FPH, GHo, GW, IJD, IK, IMN, IN, JAB, JAS, JD, JDF, JEK, JFC, JIR, JLiu, JMS, KDT, KEN, KLe, KLS, KNC, KLS, LFB, L-PL, LRY, LCS, MA, MRB, MC, MF, MFF, MH, MMP, MP, MPC, MRB, MYT, NA, NDP, NJS, NK, NV, OP, PBM, PF, PH, PKM, RDo, RM, RN, SA, SEH, SH, SKM, SLK, SP, SSR, TAL, TE, TKR, TL, TR, TS, UF, VF, WZha, WZhe, X-OS, XS, XZ, Y-DIC, YF, and YJS participated in the genotype data acquisition and/or quality control. ACM, ACP, AD, AKM, APo, AR, ARB, ARH, AVS, BIF, BK, BMP, BOT, CB, CCG, CDL, CGa, CGi, CLM, CPN, C-TL, CY, C-YC, DIC, DKA, DMB, DV, DX, EBW, EL, ERF, F-CH, FG, FL, FPH, FT, GW, HA, IMN, IN, JAB, JAS, JBJ, JD, JDF, JEK, JFC, JLia, JRO, JSF, J-MY, KEN, KLe, KLS, KR, LF, LFB, L-PL, LRY, MA, MAR, MRB, MF, MFF, MH, MKE, MP, MR, MRB, MS, NDP, NV, PAP, PH, PJM, PK, PKM, PSV, RDo, RM, RN, RSC, SA, SEH, SFW, SH, SKM, SLK, TMB, TOK, TR, TW, TWW, TYW, UB, UF, VF, W-BW, WJG, WW, WZha, XChe, XG, XL, XS, YJS, YXW, and YZ participated in data analysis and interpretation. All authors have provided approval for publication of the contents and agree to be accountable for the content of the work.

Conflict of interest

IN is now employed by Celgene. BMP serves on the Steering Committee of the Yale Open Data Access Project funded by Johnson & Johnson. SA is employed by and holds equity in 23andMe, Inc. Authors BK, MW, and CGa were employed by Helmholtz Zentrum München.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2023.1235337/full#supplementary-material

References

- Ahima R. S. (2006). Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Obes. (Silver Spring) 14, 242S–249S. Suppl 5. 10.1038/oby.2006.317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S., Bazargan M. (2019). Minorities' diminished returns of educational attainment on hospitalization risk: national health interview survey (nhis). Hosp. Pract. Res. 4 (3), 86–91. 10.15171/HPR.2019.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assary E., Vincent J. P., Keers R., Pluess M. (2018). Gene-environment interaction and psychiatric disorders: review and future directions. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 77, 133–143. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon C., Rappold G. A. (2012). The distinct and overlapping phenotypic spectra of FOXP1 and FOXP2 in cognitive disorders. Hum. Genet. 131 (11), 1687–1698. 10.1007/s00439-012-1193-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baigent C., Keech A., Kearney P. M., Blackwell L., Buck G., Pollicino C., et al. (2005). Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 366 (9493), 1267–1278. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson J., Sung Y. J., Schwander K., Kume R., Simino J., de las Fuentes L., et al. (2014). Gene-education interactions identify novel blood pressure loci in the Framingham Heart Study. Am. J. Hypertens. 27 (3), 431–444. 10.1093/ajh/hpt283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bays H. E., Toth P. P., Kris-Etherton P. M., Abate N., Aronne L. J., Brown W. V., et al. (2013). Obesity, adiposity, and dyslipidemia: a consensus statement from the National Lipid Association. J. Clin. Lipidol. 7 (4), 304–383. 10.1016/j.jacl.2013.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blockus H., Chedotal A. (2014). The multifaceted roles of Slits and Robos in cortical circuits: from proliferation to axon guidance and neurological diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 27, 82–88. 10.1016/j.conb.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P. A., Cubbin C., Egerter S., Chideya S., Marchi K. S., Metzler M., et al. (2005). Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA 294 (22), 2879–2888. 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Cui Z., Feng R., Tang Y. P., Qin Z., Mei B., et al. (2007). Maintenance of superior learning and memory function in NR2B transgenic mice during ageing. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25 (6), 1815–1822. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke P. S., Holsberger D. R., Cimafranca M. A., Meling D. D., Beals C. M., Nakayama K., et al. (2007). The F box protein S phase kinase-associated protein 2 regulates adipose mass and adipocyte number in vivo . Obes. (Silver Spring) 15 (6), 1400–1408. 10.1038/oby.2007.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de las Fuentes L., Sung Y. J., Noordam R., Winkler T., Feitosa M. F., Schwander K., et al. (2020). Gene-educational attainment interactions in a multi-ancestry genome-wide meta-analysis identify novel blood pressure loci. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 2111–2125. 10.1038/s41380-020-0719-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin B., Roeder K. (1999). Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics 55 (4), 997–1004. 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00997.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietschy J. M., Turley S. D. (2001). Cholesterol metabolism in the brain. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 12 (2), 105–112. 10.1097/00041433-200104000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espirito Santo L. R., Faria T. O., Silva C. S. O., Xavier L. A., Reis V. C., Mota G. A., et al. (2019). Socioeconomic status and education level are associated with dyslipidemia in adults not taking lipid-lowering medication: a population-based study. Int. Health 14, 346–353. 10.1093/inthealth/ihz089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele L., Newcombe J., Topf M., Gibb A., Harvey R. J., Smart T. G. (2018). Disease-associated missense mutations in GluN2B subunit alter NMDA receptor ligand binding and ion channel properties. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 957. 10.1038/s41467-018-02927-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franssen R., Monajemi H., Stroes E. S., Kastelein J. J. (2011). Obesity and dyslipidemia. Med. Clin. North Am. 95 (5), 893–902. 10.1016/j.mcna.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald W. T., Levy R. I., Fredrickson D. S. (1972). Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 18 (6), 499–502. 10.1093/clinchem/18.6.499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo L. C., Matthews K. A., Kuller L. H., Sutton-Tyrrell K., Edmundowicz D. (2001). Educational attainment and coronary and aortic calcification in postmenopaUnited Statesl women. Psychosom. Med. 63 (6), 925–935. 10.1097/00006842-200111000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genomes Project Consortium, Abecasis G. R., Auton A., Brooks L. D., DePristo M. A., Durbin R. M., et al. (2012). An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature 491 (7422), 56–65. 10.1038/nature11632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gliozzi M., Musolino V., Bosco F., Scicchitano M., Scarano F., Nucera S., et al. (2021). Cholesterol homeostasis: researching a dialogue between the brain and peripheral tissues. Pharmacol. Res. 163, 105215. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnudi L., Jensen D. R., Tozzo E., Eckel R. H., Kahn B. B. (1996). Adipose-specific overexpression of GLUT-4 in transgenic mice alters lipoprotein lipase activity. Am. J. Physiol. 270, R785–R792. 4 Pt 2. 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.4.R785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S. J., Black M. J., Soboloff J., Gill D. L., Dziadek M. A., Johnstone L. S. (2009). Stim1, an endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ sensor, negatively regulates 3T3-L1 pre-adipocyte differentiation. Differentiation 77 (3), 239–247. 10.1016/j.diff.2008.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamad R., Nguyen T. T., Bhattacharya J., Glymour M. M., Rehkopf D. H. (2019). Educational attainment and cardiovascular disease in the UNITED STATES: a quasi-experimental instrumental variables analysis. PLoS Med. 16 (6), e1002834. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung U. J., Choi M. S. (2014). Obesity and its metabolic complications: the role of adipokines and the relationship between obesity, inflammation, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15 (4), 6184–6223. 10.3390/ijms15046184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamm G. B., Pisciottano F., Kliger R., Franchini L. F. (2013). The developmental brain gene NPAS3 contains the largest number of accelerated regulatory sequences in the human genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 (5), 1088–1102. 10.1093/molbev/mst023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan G. A., Keil J. E. (1993). Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: a review of the literature. Circulation 88, 1973–1998. 4 Pt 1. 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavousi M., Bos M. M., Barnes H. J., Lino Cardenas C. L., Wong D., O’Donnell C. J., et al. (2022). Multi-ancestry genome-wide analysis identifies effector genes and druggable pathways for coronary artery calcification. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.02.22273844v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kraft P., Yen Y. C., Stram D. O., Morrison J., Gauderman W. J. (2007). Exploiting gene-environment interaction to detect genetic associations. Hum. Hered. 63 (2), 111–119. 10.1159/000099183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krycer J. R., Fazakerley D. J., Cater R. J., Naghiloo S., Burchfield J. G., (2017). The amino acid transporter, SLC1A3, is plasma membrane-localised in adipocytes and its activity is insensitive to insulin. FEBS Lett. 591 (2), 322–330. 10.1002/1873-3468.12549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnireva L., Korkotian E., Segal M. (2020). Calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 regulate different calcium functions in cultured hippocampal neurons. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 12, 573714. 10.3389/fnsyn.2020.573714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledreux A., Wang X., Schultzberg M., Granholm A. C., Freeman L. R. (2016). Detrimental effects of a high fat/high cholesterol diet on memory and hippocampal markers in aged rats. Behav. Brain Res. 312, 294–304. 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leino M., Raitakari O. T., Porkka K. V., Taimela S., Viikari J. S. (1999). Associations of education with cardiovascular risk factors in young adults: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 28 (4), 667–675. 10.1093/ije/28.4.667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng B., Jin Y., Li G., Chen L., Jin N. (2015). Socioeconomic status and hypertension: a meta-analysis. J. Hypertens. 33 (2), 221–229. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Xiong G. J., Huang N., Sheng Z. H. (2020). The cross-talk of energy sensing and mitochondrial anchoring sustains synaptic efficacy by maintaining presynaptic metabolism. Nat. Metab. 2 (10), 1077–1095. 10.1038/s42255-020-00289-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Huang S., Ling S., Xu S., Wang F., Zhang W., et al. (2019). Foxp1 controls brown/beige adipocyte differentiation and thermogenesis through regulating β3-AR desensitization. Nat. Commun. 10 (1), 5070. 10.1038/s41467-019-12988-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loriol C., Khayachi A., Poupon G., Gwizdek C., Martin S. (2013). Activity-dependent regulation of the sumoylation machinery in rat hippocampal neurons. Biol. Cell 105 (1), 30–45. 10.1111/boc.201200016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoTurco J. J., Bai J. (2006). The multipolar stage and disruptions in neuronal migration. Trends Neurosci. 29 (7), 407–413. 10.1016/j.tins.2006.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewski L., Maciag F., Boguszewski P. M., Wasilewska I., Wiera G., Wojtowicz T., et al. (2017). Overexpression of STIM1 in neurons in mouse brain improves contextual learning and impairs long-term depression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1864 (6), 1071–1087. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning A. K., LaValley M., Liu C. T., Rice K., An P., Liu Y., et al. (2011). Meta-analysis of gene-environment interaction: joint estimation of SNP and SNP × environment regression coefficients. Genet. Epidemiol. 35 (1), 11–18. 10.1002/gepi.20546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda S., Matsuda Y., D'Adamio L. (2009). BRI3 inhibits amyloid precursor protein processing in a mechanistically distinct manner from its homologue dementia gene BRI2. J. Biol. Chem. 284 (23), 15815–15825. 10.1074/jbc.M109.006403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews K. A., Kelsey S. F., Meilahn E. N., Kuller L. H., Wing R. R. (1989). Educational attainment and behavioral and biologic risk factors for coronary heart disease in middle-aged women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 129 (6), 1132–1144. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melbourne C. A., Mesut Erzurumluoglu A., Shrine N., Chen J., Tobin M. D., Hansell A. L., et al. (2022). Genome-wide gene-air pollution interaction analysis of lung function in 300,000 individuals. Environ. Int. 159, 107041. 10.1016/j.envint.2021.107041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf P. A., Sharrett A. R., Folsom A. R., Duncan B. B., Patsch W., Hutchinson R. G., et al. (1998). African American-white differences in lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins, by educational attainment, among middle-aged adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 148 (8), 750–760. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao L., Yin R. X., Wu J. Z., Yang S., Lin W. X., Pan S. L. (2017). The SRGAP2 SNPs, their haplotypes and G × E interactions on serum lipid traits. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 11626. 10.1038/s41598-017-10950-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M., Sakai T., Nakamura T., Tamamori-Adachi M., Kitajima S., Matsuki Y., et al. (2009). Skp2 promotes adipocyte differentiation via a p27Kip1-independent mechanism in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 379 (2), 249–254. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okbay A., Beauchamp J. P., Fontana M. A., Lee J. J., Pers T. H., Rietveld C. A., et al. (2016). Genome-wide association study identifies 74 loci associated with educational attainment. Nature 533 (7604), 539–542. 10.1038/nature17671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peloso G. M., Auer P. L., Bis J. C., Voorman A., Morrison A. C., Stitziel N. O., et al. (2014). Association of low-frequency and rare coding-sequence variants with blood lipids and coronary heart disease in 56,000 whites and blacks. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 94 (2), 223–232. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera H. K., Clarke M., Morris N. J., Hong W., Chamberlain L. H., Gould G. W. (2003). Syntaxin 6 regulates Glut4 trafficking in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell 14 (7), 2946–2958. 10.1091/mbc.e02-11-0722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistell P. J., Morrison C. D., Gupta S., Knight A. G., Keller J. N., Ingram D. K., et al. (2010). Cognitive impairment following high fat diet consumption is associated with brain inflammation. J. Neuroimmunol. 219 (1-2), 25–32. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan G., Samson S. L., Sun Y. (2013). Ghrelin: much more than a hunger hormone. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 16 (6), 619–624. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328365b9be [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D. C., Sung Y. J., Winkler T. W., Schwander K., Borecki I., Cupples L. A., et al. (2017). Multiancestry study of gene-lifestyle interactions for cardiovascular traits in 610 475 individuals from 124 cohorts: design and rationale. Circ. Cardiovasc Genet. 10 (3), e001649. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero A., Kirchner H., Heppner K., Pfluger P. T., Tschop M. H., Nogueiras R. (2010). GOAT: the master switch for the ghrelin system? Eur. J. Endocrinol. 163 (1), 1–8. 10.1530/EJE-10-0099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer T., Lindtner C., O'Hare J., Hackl M., Zielinski E., Freudenthaler A., et al. (2016). Insulin regulates hepatic triglyceride secretion and lipid content via signaling in the brain. Diabetes 65 (6), 1511–1520. 10.2337/db15-1552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semon M., Duret L. (2006). Evolutionary origin and maintenance of coexpressed gene clusters in mammals. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23 (9), 1715–1723. 10.1093/molbev/msl034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea S., Melnik T. A., Stein A. D., Zansky S. M., Maylahn C., Basch C. E. (1993). Age, sex, educational attainment, and race/ethnicity in relation to consumption of specific foods contributing to the atherogenic potential of diet. Prev. Med. 22 (2), 203–218. 10.1006/pmed.1993.1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman G. I. (2014). Ectopic fat in insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and cardiometabolic disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 371 (12), 1131–1141. 10.1056/NEJMra1011035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorel J. E., Ragland D. R., Syme S. L., Davis W. B. (1992). Educational status and blood pressure: the second national health and nutrition examination survey, 1976-1980, and the hispanic health and nutrition examination survey, 1982-1984. Am. J. Epidemiol. 135 (12), 1339–1348. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanger S. A., Chen W., Wells G., Burger P. B., Tankovic A., Bhattacharya S., et al. (2016). Mechanistic insight into NMDA receptor dysregulation by rare variants in the GluN2A and GluN2B agonist binding domains. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99 (6), 1261–1280. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki K., Kamakura M., Nakamichi N., Taniura H., Yoneda Y. (2008). Upregulation of Myo6 expression after traumatic stress in mouse hippocampus. Neurosci. Lett. 433 (3), 183–187. 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.12.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyroler H. A. (1989). Socioeconomic status in the epidemiology and treatment of hypertension. Hypertension 13, I94–I97. 5 Suppl. 10.1161/01.hyp.13.5_suppl.i94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Eckel R. H. (2009). Lipoprotein lipase: from gene to obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 297 (2), E271–E288. 10.1152/ajpendo.90920.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Li M., Hakonarson H. (2010). ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38 (16), e164. 10.1093/nar/gkq603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward L. D., Kellis M. (2012). HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D930–D934. Database issue. 10.1093/nar/gkr917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K., Taskesen E., van Bochoven A., Posthuma D. (2017). Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 1826. 10.1038/s41467-017-01261-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werme J., van der Sluis S., Posthuma D., de Leeuw C. A. (2021). Genome-wide gene-environment interactions in neuroticism: an exploratory study across 25 environments. Transl. Psychiatry 11 (1), 180. 10.1038/s41398-021-01288-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willer C. J., Li Y., Abecasis G. R. (2010). METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics 26 (17), 2190–2191. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J. M. P., Parks C. G., Jacobsen S., Costenbader K. H., Bernatsky S. (2022). The role of environmental exposures and gene-environment interactions in the etiology of systemic lupus erythematous. J. Intern Med. 291 (6), 755–778. 10.1111/joim.13448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q., Yang G. Y., Liu N., Xu P., Chen Y. L., Zhou Z., et al. (2012). P4-ATPase ATP8A2 acts in synergy with CDC50A to enhance neurite outgrowth. FEBS Lett. 586 (13), 1803–1812. 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Xiong Y., Hu X. F., Du Y. H. (2015). MicroRNA-323 regulates ischemia/reperfusion injury-induced neuronal cell death by targeting BRI3. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 8 (9), 10725–10733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi C. X., Tschop M. H. (2012). Brain-gut-adipose-tissue communication pathways at a glance. Dis. Model Mech. 5 (5), 583–587. 10.1242/dmm.009902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Yuan S., Pu J., Yang L., Zhou X., Liu L., et al. (2018). Integrated metabolomics and proteomics analysis of Hippocampus in a rat model of depression. Neuroscience 371, 207–220. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Danbolt N. C. (2014). Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the healthy brain. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 121 (8), 799–817. 10.1007/s00702-014-1180-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y., Gong N., Cui Y., Wang X., Cui A., Chen Q., et al. (2015). Forkhead box P1 (FOXP1) transcription factor regulates hepatic glucose homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 290 (51), 30607–30615. 10.1074/jbc.M115.681627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: 83 US and international cohorts participated in this study, each subject to different regulations regarding sharing of data. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to LF, lfuentes@wustl.edu.