Highlights

-

•

Thrombin stimulates AA release and increases lipid oxidation accumulation via the cPLA2α-ACSL4 pathway in triple-negative breast cancer cells.

-

•

Lower F2 and Acsl4 levels were associated with poorer prognosis in breast cancer.

-

•

In a mouse xenograft model, upregulation of thrombin suppressed TNBC growth which can be inhibited by ferroptosis inhibitor Liproxstatin-1.

Keywords: Thrombin, Ferroptosis, TNBC, ACSL4, Lipid peroxidation

Abstract

Ferroptosis is a recently identified form of regulated cell death that plays a crucial role in tumor suppression. In this study, we found that F2 (the gene encoding thrombin) was strongly upregulated in breast cancer (BRCA, TCGA Study Abbreviations) compared with normal samples and that lower F2 levels were associated with poorer prognosis in breast cancer patients. Thrombin induces ferroptosis in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells by activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2α (cPLA2α) activity to increase the release of arachidonic acid (AA). TNBC in all breast cancer subtypes exhibited the highest levels of PLA2G4A (the gene encoding cPLA2α) and Acsl4, and inhibition of cPLA2α and its downstream enzyme acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) reversed thrombin toxicity. In a mouse xenograft model of TNBC, thrombin treatment suppressed breast cancer growth which can be inhibited by ferroptosis inhibitor Liproxstatin-1 (Lip-1). Our study underscores the potential of the thrombin-ACSL4 axis as a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of TNBC.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Ferroptosis has been implicated in tumor suppression, antiviral immunity, neurodegeneration, and ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI) [1,2]. In tumor biology and cancer therapy, ferroptosis has been identified to inhibit the growth of non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, liver cancer, ovarian cancer, and other carcinogenic cancer cells [3]. It also contributes to the antitumor function of tumor suppressors (p53, BAP1, and fumarase) [4]. Furthermore, highly invasive mesenchymal-like cancer cells are often highly resistant to regular treatment options but are susceptible to ferroptosis [5]. Therefore, targeting ferroptosis may provide new therapeutic opportunities for the treatment of cancers.

Breast cancer is the most common type of malignant tumor. Breast cancers expressing estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), or epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) can be effectively treated by conventional endocrine therapies [6]. However, TNBCs that do not express any of these receptors, are more resistant to treatments with a significantly worse prognosis [7]. Thus, chemotherapy remains a viable and effective option for managing TNBC. Chemical inducers of ferroptosis (RSL3, Erastin, and their derivatives) are currently being investigated as potential therapies for breast cancer. However, their poor water solubility and nephrotoxicity limit their applications [6,8]. Therefore, identifying novel targets of ferroptosis induction may provide a more effective therapeutic strategy for TNBC.

The induction and defense mechanisms of ferroptosis have been extensively investigated. Our previous work demonstrated that thrombin promotes the release of AA from membrane phospholipids through activating cPLA2α, and then participates in the production of lipid peroxides mediated by ACSL4 and initiating ferroptosis signaling during cerebral ischemia/reperfusion [9]. Therefore, antithrombin therapy may benefit stroke by inhibiting ferroptosis. On the other hand, it also raises the possibility to target thrombin for the induction of ferroptosis in tumor cells.

In this study, we analyzed the association of thrombin and ACSL4 with breast cancer progression using existing datasets. The anti-cancer effects of thrombin on MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were investigated using genetic or pharmacological modifications and xenograft mouse models, and the underlying mechanism of action was explored. This line of evidence may strengthen our understanding of the involvement of ferroptosis in TNBC and provide new targets worthing further investigation.

Materials and methods

Reagents and assay kit

Liproxstatin-1 (Lip-1, S7699), Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1, S7243), Chloroquine (S6999), and Z-VAD-FMK (ZVAD, S7023) were purchased from Selleck Chemical (USA). Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1, HY-15760), AACOCF3 (HY-108611), and DMSO (HY-Y0320) were obtained from MedChemExpress (USA). Thrombin (ab62452, concentration data can be obtained from the official website based on the batch number), Lipid Peroxidation (MDA) Assay kit (ab233471), and Cytosolic Phospholipase A2 Assay Kit (ab133090) were acquired from Abcam (USA). Pioglitazone (112529-15-4) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX transfection reagent (13778030), 0.25 % trypsin/EDTA (25200056), and BODIPY 581/591 C11 (D3861) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA). Unless specified, the rest of the reagents were from Beyotime (CN).

Cell line and culture conditions

The MDA-MB-231 (Cat No. SCSP-5043), Hs578T (Cat No. TCHu127), and 4T1 (Cat No. SCSP-5056) cell lines were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences cell library. These cells were grown in DMEM Medium with 10 % fetal bovine serum (NATOCOR, Argentina, SFBE) in a humidified incubator with 5 % CO2. The cell culture medium was changed every three days, and cells were passaged using 0.25 % trypsin/EDTA (25200056).

Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates (2000 cells per well) and treated with the compounds [thrombin (ab62452), DMSO (HY-Y0320), Lip-1 (S7699), Fer-1 (S7243), ZVAD (S7023), NAC (S0077), Chloroquine (SS6999), Nec-1(HY-15760), AACOCF3, (HY-108611), Pioglitazone (112529-15-4)] after plating. Cell viability was assessed 48 hrs after treatment using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8, Bimake, USA, B34302) at the optical density of 450 nm, as previously described [10].

Calcein AM and Propidium Iodide (PI) staining

The status of cells was determined according to the instructions of the live/dead cell staining kit (Proteintech, USA, PF00007) [11]. 100,000 cells per well were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with the thrombin in the presence of different types of cell death inhibitors for 48 hrs (Lip-1, Fer-1, NAC, ZVAD, Chloroquine, Nec-1). The cells were collected and incubated with 2 μM Calcein AM and 4.5 μM PI for 15 mins at 37 °C in an incubator (Thermo 3307 Forma Steri-Cult CO2). Subsequently, the status of cells was measured within 30 mins by flow cytometry (BD, USA, LSR Fortessa), analyzed at least 10,000 cells per sample. Dead cells were detected in the Q1 area, live cells in the Q3 area, and cell debris in the Q4 area. Data analysis was conducted using FlowJo Software (BD, USA, FlowJo™ V10).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Cell mitochondrial size and mitochondrial membrane density were assayed using transmission electron microscopy as previously described [9]. After 48 hrs of thrombin treatment, the cells were collected into a 1.5 mL EP tube, in which the cells were centrifuged at low speed (400 × g) to the bottom of the EP tube, and the supernatants were removed. Cell pellets were immediately fixed with 0.1 M PBS (pH = 7.4) containing 2.5 % glutaraldehyde for 4 hrs at 4 °C, post-fixed in 1 % osmium tetroxide for 2 hrs at room temperature (20 °C), dehydrated in gradual ethanol (50–100 %) and acetone, embedded in epoxy resin. Polymerization was performed for 48 hrs at 60 °C. Ultrathin sections (80 nm) were cut, and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate before transmission electron microscopy analysis (HITACHI, JPN, HT7700). Images were taken with a Slow Scan CCD camera and iTEM software (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions, JPN).

Assessment of lipid peroxidation with BODIPY and MDA

Lipid peroxidation within cells was assessed as previously described [9,10]. 100,000 cells per well were seeded in 6-well plates. Cells were treated with the compounds (thrombin, 8 μg/mL; Lip-1, 2 μM; Fer-1, 2 μM; AACOCF3, 10 μM; Pioglitazone, 10 μM), and were collected and incubated with 1 µM BODIPY 581/591 C11 (D3861) for 30 mins at 37 °C in an incubator. Subsequently, cells were resuspended in 500 µL HBSS, strained through a 40 µm cell strainer (BD, USA, 352340), and analyzed using the 488 nm laser of a flow cytometer (BD, USA, LSR Fortessa). For BODIPY 581/591 C11 staining, the signals from both non-oxidized C11 (PE channel) and oxidized C11 (FITC channel) were monitored. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ratios of FITC to MFI of PE were calculated. At least 10,000 cells were analyzed per sample. Data analysis was conducted using FlowJo Software (BD, USA).

The cellular MDA level was assessed using the Lipid Oxidation (MDA) Detection Kits (ab233471) as previously described [12]. Briefly, samples and MDA color reagent were added into the well and incubated at room temperature for 20 mins. Following this, the reaction solution was introduced and the mix was incubated for 60 mins at room temperature. The resulting product was subsequently assessed at 695 nm using an absorbance microplate reader.

Detection of intracellular ferrous iron

Intracellular Fe2+ was detected using FerroOrange (Dojindo, Japan, F374) as described previously [13]. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with thrombinfor 24 hrs and then incubated with FerroOrange (1 µM) in serum-free DMEM for 30 mins in a 37 °C incubator. The cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope. The fluorescence intensity at Ex/Em=543/580 nm was detected by a microplate reader (BioTek, USA, Synergy HTX), and the cell viability was quantified by CCK8. Values of A 543/580 nm/A CCK8 were calculated for normalization and subsequent statistical analysis.

Immunoblotting

After the indicated treatments, cells were harvested and washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (Beyotime, China, P0013) containing the protease inhibitor PMSF (Beyotime, China, ST507). Protein concentration was quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, China, P0011). Subsequently, equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Block with 5 % skim milk for 1 h and incubate with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C with shaking. The membrane was washed 5 times with TBST and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 120 min at 30 °C. The membrane was then washed three times in TBST, developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (NCM Biotech, China, P10300) [14], and visualized using ChemiScope 6100 (CLiNX, China). Chemiluminescent band intensity quantification was performed using ImageJ (v1.53a, NIH, USA). The primary antibodies used in this experiment are as follows: anti-PTGS2 (Abcam, ab15191, 1:1000), anti-4-HNE (Abcam, ab46545, 1:1000), anti-Ferritin (Abcam, ab75973, 1:1000), anti-FPN (Abcam, ab239583, 1:1000), anti-cPLA2α (GeneTex, USA, GTX110218, 1:1000), anti-ACSL4 (Abcam, USA, ab155282, 1:5000), anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz, CA, sc-47778, 1:1000). All uncropped Western blot images are shown in Supplementary Figure S3.

Detection of the activity of cytoplasmic phospholipase A2

The cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2, cPLA2α) activity in the cells was assessed using the Cytosolic Phospholipase A2 Assay Kit (ab133090) as previously described [15]. The cells were collected by centrifugation (1000 × g for 10 mins at 4 °C), and the cell pellet was sonicated in 1 ml of cold buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, containing 1 mM EDTA). The pellet was then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 mins at 4 °C, and protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein assay kit (P0010). Protein samples were first incubated with Bromoenol Lactone for 15 mins at 25 °C to inhibit the iPLA2 activity. Substrate solution was then added to initiate the reaction and incubated for 60 mins at room temperature. Next, DTNB/EGTA was added to end the enzyme-catalyzed reaction. Finally, the absorbance was read at 414 nm using a microplate reader. The absorbance readings were converted to enzyme activity following the manufacturer's instructions.

Detection of intracellular AA

MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with thrombin, and cell extracts were prepared as instructed (https://www.elabscience.com/List-detail-259.html). The cellular AA level was assessed using the AA (arachidonic acid) ELISA kit (Elabscience, CN, E-EL-0051c) [16]. Briefly, Samples and the biotinylated detection antibody working solution were incubated together at 37 °C for 45 mins, followed by blotting dry and washing. Next, the HRP conjugate working solution was added and incubated at 37 °C for 30 mins, then blotted dry and washed. Subsequently, the substrate reagent was added and incubated at 37 °C for 15 mins. Finally, the stop solution was added, and the plate was immediately read at 450 nm by a microplate reader. The results were then calculated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

siRNA and transfection

Transfection of MDA-MB-231 cells was carried out when they achieved 70 % confluence, according to Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX transfection reagent (13778030) instructions for transfection. The synthesized oligonucleotide of cPLA2α siRNA (5′-CCUGACGUUUCAGAGCUGATT-3′) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (CA, sc-29280) [17]. The control siRNA (5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′) was obtained from GenePharma (Shanghai, China) [18]. At 24–72 hrs post-transfection, western blotting was used to analyze the expression of cPLA2α.

Generation of ACSL4 knockout and overexpressed cell lines

Single sgRNA guides were designed to target critical exons using the online tool (http://crispor.tefor.net/) [19]. The oligonucleotide sequences preceding the protospacer motif were: sgACSL4–1, 5′-CACCGAGTGTGTGACAGAGCGATA-3′ and sgACSL4–2, 5′-CACCGTAGCTGTAATAGACATCCC-3′. Guides for human ACSL4 knockout were inserted into BsmBI-digested lentiviral vector p12–2EF (kindly provided by Dr. Chong Chen, Sichuan University). ACSL4 cDNA of the human was introduced into pLVX-Puro (Clontech Laboratories, CN, 632164). Lentiviral vectors were packaged in HEK293T by the calcium phosphate method. The cells were seeded in 6-well plates, and the amount of overexpressing or knockout plasmid, psPAX2 (Addgene, USA, 12260), and pMD2.G (Addgene, USA, 12259) used for transfection in each well were 4 μg, 2 μg, and 1 μg, respectively. Puromycin (Beyotime, CN, ST551) was added to select stable cell lines at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml at 48 hrs post-transfection. The constructed cell line was verified by western blotting.

Mice

All animal care and experimental protocols were approved and performed following the guide from the Institutional Guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee (Sichuan University, 2021367A). 5-weeks-old female BALB/C nude mice were purchased from the Byrness Weil Biotech Ltd, China. All animals were raised under standard conditions of temperature (22 ± 2 °C) and humidity, and 12 h of light and dark circulation.

In vivo xenograft studies

MDA-MB-231 xenografts were established in 6-week-old nude mice by inoculating 5 × 106 cells mixed with Matrigel (BD Biocoat, USA, 354234) at a 1:1 ratio into the abdominal mammary fat pad. Tumor growth was monitored regularly via external caliper measurements. Once tumor volumes reached ≥50 mm3, mice were divided randomly into four groups (n = 6): the control, thrombin-only, Lip-1-only, and thrombin plus Lip-1 groups. Thrombin (2 mg/kg) was injected intratumorally, and Lip-1 (10 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally 30 mins before the thrombin injection. These chemicals were treated once every 4 days for 20 days. The maximum width (a) and length (b) of the tumor were measured, and the volume (V) was calculated using the formula: V = (a2 b)/2 [20]. Tumors were measured with calipers every 2 days. 20 days after administration, the mice were euthanized (maximum tumor volume did not exceed 1000 mm3), and the tumor xenografts were immediately dissected, weighed, fixed with formalin, processed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned for further immunohistochemical analysis.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC staining was performed as previously described [21]. Tissues were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded block tissues were cut into 5 μm sections. Immunohistochemical staining of paraffin-embedded sections was performed using an anti-Ki67 antibody (Abcam, USA, ab15580, 1:100), anti-PTGS2 antibody (Abcam, ab15191, 1:200) and an Immunohistochemistry kit (ZSGB-BIO Technologie, CN, SP-9000) according to the manufacturer's instructions [22]. Tissues were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. Images were acquired at three randomly selected areas through the microscope. Subsequently, the image analysis software ImageJ was used for processing. Protein expression levels were calculated by analyzing the integrated optical density of positive protein areas, and the results from each field were integrated to obtain immunohistochemical statistics for the entire tissue sample.

Bioinformatic analysis

Web-based bioinformatics tools were used for bioinformatics analysis. The level of F2 in normal samples and BRCA and the level of PLA2G4A and Acsl4 in different breast cancer subtypes were analyzed using online UALCAN (http://Ualcan.path.uab.edu/analysis) [23]. The online Kaplan-Meier (http://kmplot.com/analysis) [24] method was used to compare the recurrence-free survival (RFS) of breast cancer patients between the F2 high group and the low group based on the GSE4611 database [25] and to compare the RFS of the TNBC patients divided by the expression of Acsl4 in multiple databases. The correlation between PLA2G4A and Acsl4 in breast cancer cells was analyzed using the Spearman correlation coefficient based on the web tool GEPIA (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn) [26].

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the means ± SEM. t-test and ANOVA were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, USA). The P-value level set for statistical significance is P ≤ 0.05. All cell culture experiments were repeated independently at least three times.

Results

Thrombin and ACSL4 are associated with the progression of breast cancer

Thrombin is a multifunctional protein. In addition to promoting coagulation, thrombin can also have an impact on tumor growth and metastasis when it interacts with cells [27]. We previously found that thrombin induced ferroptosis in breast cancer cells [9]. We hypothesized that thrombin may be pathologically related to breast cancer, and tested with existing clinical datasets. The level of F2 was analyzed by online UALCAN, and as predicted it was significantly elevated in breast cancer compared to that in normal tissues (Fig. 1A). Online Kaplan-Meier Plotter analysis further indicated that the lower level of F2 was correlated with poorer prognosis of breast cancer patients (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Thrombin and ACSL4 are associated with breast cancer progression.

(A) Online UALCAN analysis of the level of F2 in BRCA. (B) Online Kaplan-Meier Plotter analysis of breast cancer patient outcomes. Differences in RFS were compared in groups stratified by F2 status. (C) Online GEPIA2 analysis showed that levels of PLA2G4A and Acsl4 were positively correlated with breast cancer. (D, E) Online UALCAN analysis of the levels of PLA2G4A (D) and Acsl4 (E) in BRCA based on breast cancer subclasses. (F) Online Kaplan-Meier Plotter analysis of TNBC patient outcomes. Differences in RFS were compared in groups stratified by Acsl4 status. P value as indicated in the figure.

Since we have found previously that thrombin is dependent on the activation of cPLA2α to promote ACSL4-mediated neuronal ferroptosis during cerebral ischemia/reperfusion [9], we speculated that cPLA2α and ACSL4 may play a role in thrombin-induced ferroptosis in breast cancer. We then examined the relationship between the levels of PLA2G4A and Acsl4 in breast cancer using GEPIA2. Our analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between the two genes (Fig. 1C). We then analyzed the levels of PLA2G4A and Acsl4 in various breast cancer subtypes. Online UALCAN analysis showed that TNBC in all breast cancer subtypes exhibited the highest levels of PLA2G4A and Acsl4 (Fig. 1D, E), implying that TNBC may be sensitive to thrombin-induced breast cancer ferroptosis. Furthermore, online Kaplan-Meier Plotter analysis indicated that lower Acsl4 was significantly associated with poorer prognosis in TNBC patients (Fig. 1F). Taken together, these analyses highlighted the possibilities of targeting thrombin and ACSL4 in the treatment of breast cancer.

Thrombin induces ferroptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells with accumulation of lipid peroxide

We utilized MDA-MB-231, Hs578T, and 4T1 cells, all of which are TNBC cell lines previously reported to exhibit high ACSL4 expression [28,29], to replicate our previous findings of thrombin toxicity in neurons. We found that thrombin dose-dependently induced cell death in these cells (Fig. 2A, S1A-C). Further observation of thrombin-induced MDA-MB-231 cell death was accompanied by smaller mitochondria and increased membrane density (Fig. 2B), a pathology consistent with ferroptosis. The observed cell death was significantly prevented by ferroptosis inhibitors Lip-1, Fer-1, and glutathione precursor NAC (Fig. 2C–E), indicating the involvement of ferroptosis. Interestingly, thrombin was previously reported to induce apoptosis [11], and we found here that the apoptosis inhibitor ZVAD also reduced thrombin toxicity but to a lesser extent (Fig. 2C–E). In contrast, neither the autophagy inhibitor Chloroquine nor the necroptosis inhibitor Nec-1 prevents thrombin toxicity (Fig. 2C–E), suggesting that ferroptosis is the main pathway of cell death induced by thrombin.

Fig. 2.

Thrombin induces MDA-MB-231 cells ferroptosis.

(A) Dose-response of thrombin-induced cytotoxicity in MDA-MB-231 cells. (B) TEM images of MDA-MB-231 cells treated with thrombin (8 μg/mL) for 48 hrs. Red arrows indicate shrunken mitochondria. (C, D) Live/Dead staining assay of MDA-MB-231 cells treated with thrombin (8 μg/mL) for 48 hrs in the absence or presence of various cell death inhibitors (2 μM Lip-1, 2 μM Fer-1, 200 μM NAC, 20 μM ZVAD, 200 µM Chloroquine, 1 μM Nec-1). Flow cytometry results (C) and statistical analysis of dead cell percentage (Q1 area) (D) are shown. (E) Cell viability of MDA-MB-231 cells treated with thrombin (8 μg/mL) for 48 hrs in the absence or presence of cell death inhibitors. (F-N) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with thrombin (8 μg/mL) for 24 hrs in the absence or presence of Lip-1, Fer-1 or ZVAD. Assayed for lipid ROS levels (F, I, L) with accompanying statistical histograms (G, J, M), and MDA levels (H, K, N). (O) FerroOrange staining in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with thrombin for 24 hrs. (P) The relative intracellular Fe2+was quantified as the average fluorescence intensity observed. Data are presented as means ± SEM. P values in (D, E, G, H, J, K, M, N) were determined using the One-way ANOVA; P value in (P) was determined using the t-test. Each point in the histogram represents a sample.

Fe2+ accumulation and lipid peroxidation are critical to execute ferroptosis [30], and we analyzed whether thrombin impacts these events. Indeed, thrombin caused elevations of lipid ROS and MDA (an end product of lipid peroxidation) (Fig. 2F–N, S1D-F), as well as an upregulation in the expression of PTGS2 [31], a downstream biomarker of ferroptosis, and 4-HNE [32], another product of lipid peroxidation (Fig. S2A-C). The accumulation of lipid ROS and MDA caused by thrombin can be inhibited by Lip-1 (Fig. 2F–H) and Fer-1 (Fig. 2I–K). The apoptosis inhibitor ZVAD was unable to prevent these effects (Fig. 2L–N). On the other hand, thrombin did not cause Fe2+ accumulation in MDA-MB-231 cells assayed by FerroOrange staining (Fig. 2O, P), and did not affect the expression of iron regulatory proteins ferritin or FPN (Fig. S2A, D, E). Therefore, the ferroptotic cell death induced by thrombin is through the modulation of lipid peroxidation, rather than iron accumulation.

Thrombin activates cPLA2α in MDA-MB-231 cells

cPLA2α, an enzyme that catalyzes the cleavage of AA from the sn-2 position of glycerophospholipids in the cell membrane, can cause the liberation of AA from the membrane, which can be promoted by thrombin [2]. Consistently, thrombin treatment significantly increased cPLA2α activity (Fig. 3A), and consequently facilitated AA release in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 3B). To investigate the causal relationship between thrombin and cPLA2α, we utilized siRNA transient transfection to reduce cPLA2α expression in MDA-MB-231 cells, verified by western blots (Fig. 3C). We have then observed that cPLA2α knockdown (Fig. 3D) and the cPLA2α inhibitor AACOCF3 (Fig. 3E) significantly protected the cells from thrombin-induced cytotoxicity.

Fig. 3.

cPLA2α mediates thrombin cytotoxicity in MDA-MB-231 cells.

(A, B) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with thrombin (8 μg/mL) for 24 hrs. The activity of cPLA2α (A) and the AA content (B) was assayed. (C) Western blot analysis of the cPLA2α knockdown in MDA-MB-231 cells. (D) Dose-response of thrombin-induced cytotoxicity in siControl and sicPLA2α MDA-MB-231 cells. (E) Cell viability of MDA-MB-231 cells 48 hrs after thrombin (8 μg/mL), with AACOCF3 (10 μM) co-treatment. (F-H) siControl and sicPLA2α MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with thrombin (8 μg/mL) for 24 hrs. Assayed for lipid ROS levels (F) with accompanying statistical histograms (G), and MDA levels (H). (I-K) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with thrombin (8 μg/mL) for 24 hrs in the absence or presence of AACOCF3 (10 μM). Assayed for lipid ROS levels (I) with accompanying statistical histograms (J), and MDA levels (K). Data are presented as means ± SEM. P values in (A, B, C, E) were determined using the t-test; P values in (G, H) were determined using the Two-way ANOVA; P values in (J, K) were determined using the One-way ANOVA. Each point in the histogram represents a sample.

Previous studies reported that AA produced by cPLA2α was the major source of lipid hydroperoxides (LOOHs) in denervated [33], we therefore hypothesized that inhibition of cPLA2α attenuates thrombin toxicity by reducing lipid peroxides. We found that cPLA2α knockdown (Fig. 3F-H) and AACOCF3 (Fig. 3I-K) suppressed the thrombin-mediated increase of lipid ROS and MDA, whereas cPLA2α inhibition did not affect baseline levels of lipid ROS or MDA (Fig. 3F-H). Therefore, thrombin induces ferroptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells by accelerating AA-mediated lipid ROS generation by activation of cPLA2α.

ACSL4 is involved in thrombin-induced ferroptosis

The next key molecule downstream of cPLA2α is ACSL4, an enzyme to convert free AA to arachidonoyl-CoA through acylation, which generates lipid hydroperoxides in ferroptosis [34]. ACSL4 was reported to be crucial in several neurological disorders, such as ischemic stroke, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson's disease [9,34,35]. In cancer, it was shown that ACSL4 is involved in various tumor progression and is a potential target for anticancer therapy, such as breast and liver cancer [36,37]. We here generated ACSL4-knockout (KO) MDA-MB-231 cells genetically with CRISPR-Cas9 and ACSL4-overexpressing (OE) cells using the Plvx-Puro-ACSL4 vector, confirmed by western blot results (Fig. 4A, B). MDA-MB-231 cells lacking ACSL4 exhibited greater resistance to thrombin compared to cells with normal ACSL4 expression (Fig. 4C). Conversely, cells overexpressing ACSL4 exhibited increased sensitivity to thrombin toxicity (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, compared to WT cells, thrombin resulted in significant accumulations of lipid ROS (Fig. 4D, E) and MDA (Fig. 4F) in ACSL4 OE cells, while ACSL4 KO cells exhibited the opposite (Fig. 4D–F). The ACSL4 inhibitor pioglitazone (PIO) was applied to further validate our findings. As expected, PIO reduced thrombin cytotoxicity (Fig. 4G), with reduced levels of lipid ROS (Fig. 4H, I) and MDA (Fig. 4J). Collectively, these findings suggested that ACSL4 functions as a facilitator in thrombin-induced ferroptosis.

Fig. 4.

ACSL4 mediates thrombin cytotoxicity in MDA-MB-231 cells.

(A, B) Western blot analysis of the ACSL4 KO (A) and ACSL4 OE (B) in MDA-MB-231 cells. (C) Dose-response of thrombin-induced cytotoxicity in WT, ACSL4 KO, and ACSL4 OE MDA-MB-231 cells. (D-F) WT, ACSL4 KO, and ACSL4 OE MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with thrombin (8 μg/mL) for 24 hrs. Assayed for lipid ROS levels (D) with accompanying statistical histograms (E), and MDA levels (F). (G) Cell viability of MDA-MB-231 cells 48 hrs after thrombin (8 μg/mL), with PIO (10 μM) co-treatment. (H-J) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with thrombin (8 μg/mL) for 24 hrs in the absence or presence of PIO (10 μM). Assayed for lipid ROS levels (H) with accompanying statistical histograms (I), and MDA levels (J). Data are presented as means ± SEM. P values in (A, B, G) were determined using the t-test; P values in (E, F) were determined using the Two-way ANOVA; P values in (I, J) were determined using the One-way ANOVA. Each point in the histogram represents a sample.

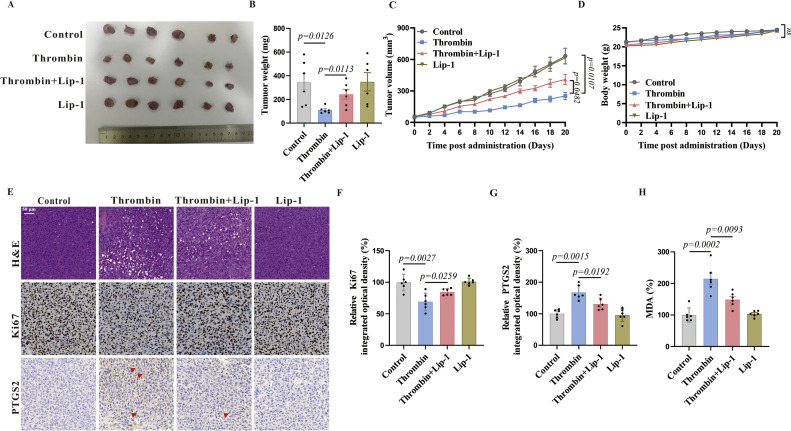

Thrombin inhibits xenograft growth in vivo

To explore the therapeutic potential of thrombin-induced ferroptosis on breast cancer, we performed in vivo mouse modeling experiments. In mice xenografted with MDA-MB-231 cells, we allowed tumors to reach an average volume of ≥50 mm3, randomly divided the mice into four groups, and initiated the administration of thrombin at the nodulation site. The tumors were significantly smaller when treated with thrombin (Fig. 5A, B). The administration of thrombin resulted in a reduced rate of tumor growth compared to the control group (Fig. 5C), without affecting the body weight (Fig. 5D). Moreover, we found a significant reduction in the expression of the tumor proliferation marker Ki67 (Fig. 5E, F) [38] with a substantial increase in the expression of the ferroptosis marker PTGS2 (Fig. 5E, G), accompanied with higher MDA levels (Fig. 5H). Lip-1 partially restored the tumor growth (Fig. 5A–C). Taken together, these findings are in line with the in vitro evidence, indicating that thrombin may exert a tumor-suppressive effect, promoting the cells to ferroptosis, which ultimately may prolong the life of patients as found in the cohort studies (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 5.

Thrombin leads to tumor regression in vivo.

(A, B) Xenografted tumors were dissected, and their size (A) and weight (B) were measured. (C) The growth curves represent the average size of xenografts in mice. (D) The body weight curves of mice in indicated groups. (E-G) H&E staining and IHC analysis for Ki-67 and PTGS2 in tumor tissues. Representative images were shown (E) and the statistical columns were quantified via Ki67 relative integrated optical density (IOD) value (F) and PTGS2 relative IOD values (G) (Red arrows indicate PTGS2-positive areas, and statistics are based on positive areas). (H) The MDA levels of mice in indicated groups were detected. Data are presented as means ± SEM. P values in (B, F, G, H) were determined using the One-way ANOVA; P values in (C, D) were determined using the two-tailed t-test with 95 % confidence interval. Each point in the histogram represents a sample.

Discussions

Here, we identified that thrombin induces ferroptosis in TNBC cell lines with high ACSL4 expression through the activation of cPLA2α to release AA from the cell membrane. By genetic manipulations and pharmacological inhibitions, we have pinpointed cPLA2α and ACSL4 as crucial proteins in thrombin-triggered ferroptosis. More importantly, analysis of existing datasets found that F2 levels were significantly elevated in BRCA compared with normal samples, and lower F2 levels were associated with poorer prognosis in breast cancer patients. PLA2G4A and Acsl4 are highly expressed in TNBC, and lower levels of Acsl4 are associated with poor prognosis in TNBC patients. These findings provided additional insights into the use of ferroptosis inhibitors in TNBC and may have implications for other types of cancer.

Thrombin, a Na+-activated serine protease, directly contributes to blood coagulation, angiogenesis, atherosclerosis, innate immunity, and tumor biology [9]. A dose-dependent dual effect of thrombin on tumor cell growth/apoptosis or impaired mitosis has been previously described [39,40]. It forms a pro-tumor microenvironment at lower doses to drive cell proliferation and metastasis, but causes cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase leading to apoptosis at higher doses [39,40]. Furthermore, thrombin is delivered explicitly to tumor-associated blood vessels, which induces intravascular thrombus formation leading to tumor necrosis [41]. Our results further indicated that exogenous thrombin increased lipid peroxide and induced ferroptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells, and therefore, inhibited tumor growth in vivo. This suggests that thrombin has promising potential as an antitumor drug with diverse applications.

PLA2 is a class of enzymes that catalyze the release of fatty acids from phospholipids and is generally divided into three types: secreted PLA2 (sPLA2), cytoplasmic PLA2 (cPLA2), and Ca2+-independent PLA2 (iPLA2) [42]. Two important members of the phospholipase A2 superfamily display a proclivity toward plasmalogen phospholipids with arachidonate at the sn-2 position: cPLA2α and iPLA2β [9]. cPLA2α is a highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed enzyme implicated in the pathophysiology of several inflammation-related diseases and cancers [43]. It promotes the production of lipid mediators [44], and enables its preferential hydrolysis of sn-2 arachidonic acid, initiating the release of AA to produce lipid mediators [45]. Our analysis found that PLA2G4A was positively correlated with its downstream gene Acsl4, and PLA2G4A had the highest level of TNBC compared with other breast cancer subtypes. We then demonstrate here that genetic and pharmacological inhibition of cPLA2α reduces thrombin-mediated ferroptosis, further supporting the role of PLA2 in ferroptosis.

ACSL4 is associated with cellular ferroptosis sensitivity and is considered a sensitive monitor and a vital contributor to ferroptosis [46]. ACSL4 is preferentially expressed in a subset of TNBC cell lines that are sensitive to ferroptosis, and loss of ACSL4 protects these cells from ferroptosis [47]. While the critical role of ACSL4 in ferroptosis is known, its role in thrombin-induced tumor cell death is unclear. We found that the Acsl4 level was higher in TNBC than in other types of breast cancer, and a lower Acsl4 level was significantly associated with poorer prognosis in TNBC patients. ACSL4 knockout and intervention with the ACSL4 inhibitor pioglitazone reduced thrombin cytotoxicity in MDA-MB-231 cells, suggesting that ACSL4 mediates the toxicity of thrombin. In addition to TNBC, ACSL4 is highly expressed in prostate, liver, and colorectal cancers and is associated with poor prognosis [48]. Therefore, the role of thrombin in these diseases may be worthy of further investigation.

In conclusion, thrombin plays a crucial role in ferroptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells through the generation of excess lipid ROS, where cPLA2α and ACSL4 are crucial mediators of toxicity. This supports targeting the thrombin-ACSL4 axis as a promising therapeutic approach for TNBC.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shuo Xu: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Qing-zhang Tuo: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Jie Meng: Investigation, Resources, Funding acquisition. Xiao-lei Wu: Investigation, Resources, Funding acquisition. Chang-long Li: Supervision, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Peng Lei: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (2022NSFSC1509), the West China Hospital 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence (ZYYC20009), and the Sichuan University Postdoctoral Interdisciplinary Innovation Fund (JCXK2206).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101817.

Contributor Information

Chang-long Li, Email: changlongli@scu.edu.cn.

Peng Lei, Email: peng.lei@scu.edu.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Yan H.F., Zou T., Tuo Q.Z., et al. Ferroptosis: mechanisms and links with diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021;6(1):49. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00428-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo J., Tuo Q.Z., Lei P. Iron, ferroptosis, and ischemic stroke. J. Neurochem. 2023;165(4):487–520. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang C., Liu X., Jin S., et al. Ferroptosis in cancer therapy: a novel approach to reversing drug resistance. Mol. Cancer. 2022;21(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01530-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang X., Stockwell B.R., Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021;22(4):266–282. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viswanathan V.S., Ryan M.J., Dhruv H.D., et al. Dependency of a therapy-resistant state of cancer cells on a lipid peroxidase pathway. Nature. 2017;547(7664):453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature23007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu M., Gai C., Li Z., et al. Targeted exosome-encapsulated erastin induced ferroptosis in triple negative breast cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2019;110(10):3173–3182. doi: 10.1111/cas.14181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maqbool M., Bekele F., Fekadu G. Treatment strategies against triple-negative breast cancer: an updated review. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2022;14:15–24. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S348060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang F., Xiao Y., Ding J.H., et al. Ferroptosis heterogeneity in triple-negative breast cancer reveals an innovative immunotherapy combination strategy. Cell Metab. 2023;35(1):84–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.09.021. .e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuo Q.Z., Liu Y., Xiang Z., et al. Thrombin induces ACSL4-dependent ferroptosis during cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022;7(1):59. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00917-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiao L., Li X., Luo Y., et al. Iron metabolism mediates microglia susceptibility in ferroptosis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022;16 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2022.995084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park M.J., Won J.H., Kim D.K. Thrombin induced apoptosis through calcium-mediated activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 in intestinal myofibroblasts. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul) 2022 doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2022.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X., Chen X., Zhou W., et al. Ferroptosis is essential for diabetic cardiomyopathy and is prevented by sulforaphane via AMPK/NRF2 pathways. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2022;12(2):708–722. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber R.A., Yen F.S., Nicholson S.P.V., et al. Maintaining iron homeostasis is the key role of lysosomal acidity for cell proliferation. Mol. Cell. 2020;77(3):645–655. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.01.003. .e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Q., Zhang X., Guo Y.J., et al. Scopolamine causes delirium-like brain network dysfunction and reversible cognitive impairment without neuronal loss. Zool Res. 2023;44(4):712–724. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2022.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pharaoh G., Brown J.L., Sataranatarajan K., et al. Targeting cPLA2 derived lipid hydroperoxides as a potential intervention for sarcopenia. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):13968. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70792-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H., Liu Y., Wang H., et al. Geometric constraints regulate energy metabolism and cellular contractility in vascular smooth muscle cells by coordinating mitochondrial DNA methylation. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 2022;9(32) doi: 10.1002/advs.202203995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L., Fu H., Luo Y., et al. cPLA2alpha mediates TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer through PI3k/Akt signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(4):e2728. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shu F., Lv S., Qin Y., et al. Functional characterization of human PFTK1 as a cyclin-dependent kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104(22):9248–9253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703327104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Concordet J.P., Haeussler M. CRISPOR: intuitive guide selection for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing experiments and screens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S., He Y., Chen K., et al. RSL3 drives ferroptosis through NF-kappaB pathway activation and GPX4 depletion in glioblastoma. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/2915019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangiafico S.P., Tuo Q.Z., Li X.L., et al. Tau suppresses microtubule-regulated pancreatic insulin secretion. Mol. Psychiatry. 2023 doi: 10.1038/s41380-023-02267-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong Y., Lan J. Overexpression of Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3D induces stem cell-like properties and metastasis in cervix cancer by activating FAK through inhibiting degradation of GRP78. Bioengineered. 2022;13(1):1952–1961. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.2024336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandrashekar D.S., Karthikeyan S.K., Korla P.K., et al. UALCAN: an update to the integrated cancer data analysis platform. Neoplasia. 2022;25:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2022.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gyorffy B., Lanczky A., Eklund A.C., et al. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;123(3):725–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gyorffy B., Karn T., Sztupinszki Z., et al. Dynamic classification using case-specific training cohorts outperforms static gene expression signatures in breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;136(9):2091–2098. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang Z., Li C., Kang B., et al. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(W1):W98–W102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danckwardt S., Hentze M.W., Kulozik A.E. Pathologies at the nexus of blood coagulation and inflammation: thrombin in hemostasis, cancer, and beyond. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 2013;91(11):1257–1271. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1074-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belkaid A., Ouellette R.J., Surette M.E. 17beta-estradiol-induced ACSL4 protein expression promotes an invasive phenotype in estrogen receptor positive mammary carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2017;38(4):402–410. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgx020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang Y., Zhao X., Huang J., et al. Transformable hybrid semiconducting polymer nanozyme for second near-infrared photothermal ferrotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):1857. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15730-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu J.R., Tuo Q.Z., Lei P. Ferroptosis, a recent defined form of critical cell death in neurological disorders. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2018;66(2):197–206. doi: 10.1007/s12031-018-1155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang W.S., SriRamaratnam R., Welsch M.E., et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156(1–2):317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y., Swanda R.V., Nie L., et al. mTORC1 couples cyst(e)ine availability with GPX4 protein synthesis and ferroptosis regulation. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):1589. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21841-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pharaoh G., Brown J.L., Sataranatarajan K., et al. Targeting cPLA(2) derived lipid hydroperoxides as a potential intervention for sarcopenia. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):13968. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70792-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luoqian J., Yang W., Ding X., et al. Ferroptosis promotes T-cell activation-induced neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022;19(8):913–924. doi: 10.1038/s41423-022-00883-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang F., Zhou L.Y., Li P., et al. Inhibition of ACSL4 alleviates parkinsonism phenotypes by reduction of lipid reactive oxygen species. Neurotherapeutics. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s13311-023-01382-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hou J., Jiang C., Wen X., et al. ACSL4 as a potential target and biomarker for anticancer: from molecular mechanisms to clinical therapeutics. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.949863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Y., Zhu T., Wang X., et al. ACSL3 and ACSL4, distinct roles in ferroptosis and cancers. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14(23) doi: 10.3390/cancers14235896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun X., Kaufman P.D. Ki-67: more than a proliferation marker. Chromosoma. 2018;127(2):175–186. doi: 10.1007/s00412-018-0659-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang Y.Q., Li J.J., Karpatkin S. Thrombin inhibits tumor cell growth in association with up-regulation of p21(waf/cip1) and caspases via a p53-independent, STAT-1-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(9):6462–6468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zain J., Huang Y.Q., Feng X., et al. Concentration-dependent dual effect of thrombin on impaired growth/apoptosis or mitogenesis in tumor cells. Blood. 2000;95(10):3133–3138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li S., Jiang Q., Liu S., et al. A DNA nanorobot functions as a cancer therapeutic in response to a molecular trigger in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36(3):258–264. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mouchlis V.D., Dennis E.A. Phospholipase A(2) catalysis and lipid mediator lipidomics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2019;1864(6):766–771. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leslie C.C. Cytosolic phospholipase A(2): physiological function and role in disease. J. Lipid Res. 2015;56(8):1386–1402. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R057588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uozumi N., Kita Y., Shimizu T. Modulation of lipid and protein mediators of inflammation by cytosolic phospholipase A2alpha during experimental sepsis. J. Immunol. 2008;181(5):3558–3566. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quach N.D., Arnold R.D., Cummings B.S. Secretory phospholipase A2 enzymes as pharmacological targets for treatment of disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014;90(4):338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan H., Li X., Zhang X., et al. Identification of ACSL4 as a biomarker and contributor of ferroptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016;478(3):1338–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doll S., Proneth B., Tyurina Y.Y., et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13(1):91–98. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang Y., Zhou J., Hooi S.C., et al. Fatty acid activation in carcinogenesis and cancer development: essential roles of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases. Oncol. Lett. 2018;16(2):1390–1396. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.