Abstract

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is a high-risk cancer presenting with heterogeneous tumors. The high incidence of EOC metastasis from primary tumors to nearby tissues and organs is a major driver of EOC lethality. We used cellular models of spheroid formation and readherence to investigate cellular signaling dynamics in each step toward EOC metastasis. In our system, adherent cells model primary tumors, spheroid formation represents the initiation of metastatic spread, and readherent spheroid cells represent secondary tumors. Proteomic and phosphoproteomic analyses show that spheroid cells are hypoxic and show markers for cell cycle arrest. Aurora kinase B abundance and downstream substrate phosphorylation are significantly reduced in spheroids and readherent cells, explaining their cell cycle arrest phenotype. The proteome of readherent cells is most similar to spheroids, yet greater changes in the phosphoproteome show that spheroid cells stimulate Rho-associated kinase 1 (ROCK1)–mediated signaling, which controls cytoskeletal organization. In spheroids, we found significant phosphorylation of ROCK1 substrates that were reduced in both adherent and readherent cells. Application of the ROCK1-specific inhibitor Y-27632 to spheroids increased the rate of readherence and altered spheroid density. The data suggest ROCK1 inhibition increases EOC metastatic potential. We identified novel pathways controlled by Aurora kinase B and ROCK1 as major drivers of metastatic behavior in EOC cells. Our data show that phosphoproteomic reprogramming precedes proteomic changes that characterize spheroid readherence in EOC metastasis.

Keywords: epithelial ovarian cancer, metastasis, phosphoproteomics, Aurora kinase, Rock1

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Epithelial ovarian cancer cell metastasis shows distinct proteomic signatures.

-

•

Aurora kinases and ROCK1 are major drivers of metastatic behavior.

-

•

Phosphoproteomic changes precede proteomic rearrangement during reattachment.

In Brief

Using proteomic and phosphoproteomic analysis, we identified the proteomic signature of epithelial ovarian cancer cells undergoing the three stages of metastatic behavior—adherent cells, dormant spheroid cells, and readherence. We newly identified Aurora kinases and Rock1 as major drivers of metastatic behavior and found that phosphoproteomic changes precede proteomic rearrangement during reattachment.

Ovarian cancer is a high-risk cancer that accounted for approximately 3.4% of cases and 4.7% of cancer deaths in women worldwide in 2020 (1). A number of both predictive and predisposing factors for ovarian cancers have been identified, but many remain controversial or are outside of individual control: for example, while the risk of ovarian cancer increases with age, use of oral contraceptives has a protective effect (2). Among ovarian cancers, epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) accounts for 80 to 85% of cases, of which 70% are high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas (HGSOCs) (3). Mutations in the tumor protein p53 (TP53) gene are pervasive in HGSOC, while breast cancer gene 1 and 2 mutations are common drivers of HGSOC that may work in conjunction with TP53 mutations to worsen the disease (4, 5). Although HGSOC, and EOC in general, is largely responsive to platinum-based therapies, disease recurrence is common and often lethal to the patient: in the period from 2010 to 2014, the American ovarian cancer survival rate was only 43.4% (6). Recently, poly ADP ribose polymerase inhibitors showed promise in targeting recurrent EOC with mutations in DNA-damage repair pathways, such as breast cancer gene 1 and mutants (7, 8). However, the ability of EOC to metastasize to nearby organs in the abdominal cavity means that while the primary tumor and visible metastases can be effectively identified and eliminated, microscopic residual disease may remain unscathed.

EOC metastasis begins in the ovary, where individual cells or small clumps of cells can shed from the primary tumor site into the peritoneal fluid. These cells clump together, forming clusters of cells called spheroids (Fig. 1A). Spheroid cells are dormant, existing in the peritoneal cavity until a reattachment event occurs. Indeed, the presence of detached spheroid cells is a known marker of EOC (9), and these cells mostly exist in the G1 stage of the cell cycle (10). Upon reattachment, spheroid cells undergo a dormant-to-proliferative metastatic switch, re-entering the cell cycle, and beginning secondary tumor growth (Fig. 1A) (9).

Fig. 1.

Ultra-low attachment plates control spheroid formation and readherence.A, overview of epithelial ovarian cancer metastasis and (B) culturing methods for modelling metastasis. Representative figures of (C) adherent, (D) spheroid, and (E) readherent OVCAR8 epithelial ovarian cancer cells. The scale bars represent 400 μm. F–I, heatmaps of differentially expressed proteins identified by (F and G) TMT-proteomic and (H and I) phosphoprotemic analysis (F and H) adherent (Adh) versus spheroid (Sph) or (G and I) spheroid versus readherent (Read) OVCAR8 cells. Heatmaps show proteins identified as significantly different in volcano plots (see supplemental Fig. S1). TMT, tandem mass tag.

The PI3K/protein kinase B (AKT)/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway is one of several pathways dynamically regulating the spheroid formation and readherence processes. Dormant spheroid cells have low AKT1 phosphorylation at both Ser473 (10, 11, 12) and Thr308 (12), the two key regulatory sites of AKT1, relative to adherent cells. The dormant-to-proliferative metastatic switch during spheroid readherence is also AKT1-dependent, where AKT1 inhibition reduces the number of S-phase cells and leads to reduced dispersion area of the readhered spheroids (10, 11). AKT1 is a leading drug target for EOC and other cancers, where AKT1 phosphorylation status is linked to poor survival outcomes in patients (11). Mutations in the PI3K/AKT pathway are particularly common in EOC cells, with 33 to 40% of ovarian clear cell carcinomas having activating mutations in PIK3CA, leading to increased AKT phosphorylation (13, 14, 15). In serous ovarian carcinomas, although mutations in the PI3K/AKT pathway are less common, copy number amplifications of KRAS, PIK3CA, AKT1, and AKT2 are observed (16).

Although the process of EOC metastasis is relatively well understood and has been studied in tissue culture (TC) models simulating the adherent, spheroid, and readherent steps of metastasis (Fig. 1B), the global pathway regulation underlying this phenomenon remain to be elucidated (9). A thorough investigation of the major regulatory pathways and signaling changes that control metastasis are key to understanding and preventing occurrence. Here, we use tandem mass tag (TMT) labeling in mass spectrometry (MS) to perform quantitative proteomic and phosphoproteomic analysis of OVCAR8 EOC cells grown in the three conditions described above: adherent (adh), spheroid (sph), and readherent (read). These analyses reveal the major regulatory signals involved in EOC metastasis. Guided by the MS results, we propose a more detailed mechanism of EOC metastasis than previously understood, where we show the hypoxic nature of spheroids and reveal Aurora kinase B (AURKB) and Rho-associated kinase 1 (ROCK1) as major regulators of metastatic behavior.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture

OVCAR8 and HeyA8 EOC cells were grown in RPMI 1640 media and ES-2 EOC cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 media. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% CO2. OVCAR8 cells were grown as adherent cultures on standard TC-treated plastics until cells reached approximately 70 to 90% confluence, then split into the three growth conditions: adherent, spheroid, and readherent at a ratio of 1:3:3, respectively. Cells were grown for 72 h on standard TC-treated plastic (adherent and readherent) or ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates (spheroid) before harvesting (adherent and spheroid) or replating on standard TC-treated plates for additional 72 h (readherent). For harvesting, cells were washed once with Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution, trypsinized, and washed once with PBS. Cell pellets were stored at −80 °C until further processing.

Spheroid Formation and Dispersion

Adherent OVCAR8, HeyA8, and ES-2 EOC cells were trypan blue stained and counted by hemocytometer. Cells were plated in 96-well round-bottom ULA plates at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells per mL in 100 μl. Immediately after plating, cells were treated with either 5 μM Y-27632 ROCK1 inhibitor (Cayman Chemical) or PBS control. Following treatment, cells were imaged every 24 h on a Motic AE31 microscope with Infinity2 camera attachment, EVOS FL auto fluorescent microscope, or BioTek Cytation C10 confocal imaging reader. After 72 h, cells were moved from ULA plates to TC-treated 96-well plates, centrifuged for 1 min at 300×g, and allowed to grow for an additional 48 h with continued imaging. Additional treatment of previously untreated spheroids with 5 μM Y-27632 ROCK1 inhibitor or PBS was performed at the time of replating. Quantification of spheroid parameters was performed in ImageJ (https://imagej.net/downloads) with analysis in Microsoft Excel (https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel) and GraphPad Prism (https://www.graphpad.com/).

Cell Proliferation

Cells treated with 5 μM Y-27632 or PBS control at time of spheroid formation were replated on TC-treated 96-well plates, following 72 h of spheroid formation. Cells were allowed to readhere for additional 48 h (HeyA8 and ES-2) or 72 h (OVCAR8). Prior to cell counting kit 8 (CCK-8) measurement, media was replaced with 100 μl of fresh media and 10 μl of CCK-8 solution was added. After 4 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2, absorbance at 450 nm was measured on Biotek Synergy H1 plate reader or BioTek Cytation C10 confocal imaging reader. Baseline absorbance from cell-free media with CCK-8 dye was subtracted from all readings.

Protein Extraction and Digestion

Cells were lysed by three rounds of sonication at 35% amplitude (5 s on/15 s off) on ice in 6 M guanidine, 200 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinepropanesulphonic acid (EPPS) (pH 8.6), 100 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (2 mM NaF, 2 mM imidazole, 1.15 mM Na2MoO4, 2 mM Na3VO4, 4 mM Na2C4H4O6, 1 mM Na4P2O7, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate). Lysates were methanol-chloroform precipitated, and protein pellets were dried before resuspension in 200 mM EPPS. Samples were treated with 5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine for 30 min and 15 mM indole-3-acetic acid for 45 min. LysC (Wako) digestion was performed at a ratio of 1 mAu per 100 μg of protein for 2 h at 37 °C, then trypsin (Promega) was added at a ratio of 1:40 for overnight digestion. Finally, samples were corrected to pH < 2 by addition of trifluoroacetic acid, desalted by C18 column (Phenomenex), dried in a SpeedVac, and stored in −80 °C until labelling.

TMT Labeling

Samples were resuspended in 200 mM EPPS and labeled with TMT 10-plex labeling reagents as described previously (17). Reactions were quenched by addition of 2.7 μl of 5% hydroxylamine. Finally, samples were combined at equal ratios, desalted by 100 mg C18 column, and dried.

Phosphopeptide Enrichment

Phosphopeptides were isolated from whole peptide sample by consecutive TiO2 and Fe-immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC) enrichment, as described (18). Briefly, TiO2 enrichment was performed using High-Select TiO2 Phosphopeptide Enrichment Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer protocols. The flow-through and washes from TiO2 were saved and combined, dried to approximately 30 uL by SpeedVac, and used for Fe-IMAC as previously described (19). Finally, the flow-through and washes from Fe-IMAC were saved and combined, dried by SpeedVac, and used for proteome sample analysis. Both proteome and phosphoproteome samples were fractionated by Pierce High pH Reversed-Phase Peptide Fractionation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with additional elutions in 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (phosphoproteome) or 0.1% formic acid in water (proteome). Elutions were dried by SpeedVac and pellets resuspended in 0.1% formic acid in water for MS injection.

MS Analysis

MS analysis was performed as described (20). Peptides were analyzed by data-dependent acquisition method on an EASY-nLC 1000 system coupled with Q-Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were loaded on an Acclaim PepMap 100 C18 column (20 mm with 75 μm in diameter, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and separated on an EASY-Spray ES803A analytical column (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. The gradient consisted of a linear gradient from 5% to 25% B then 40% B for the last 15% of the gradient. Gradient length was 3 h for the phosphoproteome or 4 h for proteome fractions.

Experimental Design and Statistical Rationale

All experiments were carried out in at least three biological triplicates. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA test for multiple comparisons. For volcano plots, we used DEqMS (21) for proteome calculations, as DEqMS uses weighted scores based on the number of peptide spectral matches. For the phosphoproteome, the weighting using in DEqMS is not applicable and thus we used Limma (22) for creation of phosphoproteome volcano plots. Significance levels are indicated using asterisks (∗∗∗∗ p < 0.0001, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001, ∗∗ p < 0.01, ∗ p < 0.05, ns = statistically nonsignificant).

Data Analysis

FragPipe version 17.2-build23 was used for data processing (23, 24, 25, 26). The FASTA database was loaded on 27-03-2022 from UniProt (27) and decoy and contaminants lists were added by FragPipe. The database search included 20,437 protein entries and 20,437 decoys. The default TMT10 workflow was used for proteome samples and the TMT10-phospho workflow was used for phosphoproteomics samples. Changes included TMT10 to TMT11 in TMT interrogator tab. In short, two missed cleavages were allowed with (+229.16293 on lysine and +57.02146 on cysteine) fixed modifications and (+15.9949 on methionine and either +42.0106 or +229.16293 n terminal) variable and with +79.96633 added for TMT10-phospho. Mass tolerance was set to 20 ppm for both precursor and fragment ions. Percolator (28) was run with 1% false discovery rate (FDR) filter and TMT-integrator filtered peptide spectral match and peptide with minimum probability of 0.9 for quantification. For quantification with TMT-integrator all missed cleavages were filtered out. The median centering output was used for further analysis in Perseus version 1.6.14.0 (29). Analysis in Perseus was performed exactly according to (30), including normalization by z-scoring. RStudio version 4.2.2 (31) was used for creation of heatmaps and principal component analysis plots. DEqMS (21) and Limma (32) were used for quality control analysis, creation of volcano plots, and boxplots. Data was analyzed by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (33), kinase substrate enrichment analysis (KSEA) (34), Coral (35), and Cytoscape (36) with EnrichmentMap (37), Omics Visualizer (38), and STRING (39) add-ons according to respective guidelines. Kaplan–Meier plots were generated using KM-plotter, with the ovarian cancer database using the default settings (40).

Results

TMT MS Reveals Major Proteomic Reorganization During EOC Metastasis

Metastasis of ovarian cancers is a complex process that involves the coordination of various intracellular and extracellular signaling events. While some of these pathways have been characterized (41), the contribution of other cell signaling processes remains elusive. Further, identifying an individual pathway is not always enough to interpret a specific role in metastasis: many proteins are regulated spatiotemporally or by posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, or glycosylation events. Thus, investigation of both changes in protein abundance and phosphorylation status during EOC metastasis is an important step in understanding the processes regulating spheroid formation and readherence events. Therefore, to investigate the mechanisms controlling EOC metastasis, we used TMT labeling in combination with MS to perform quantitative analysis of the three metastatic steps: adherent (adh, Fig. 1C), spheroid (sph, Fig. 1D), and readherent (read, Fig. 1E) OVCAR8 EOC cells.

While the process of metastasis in patients is believed to be mostly random (42), TC practices allow controlled spheroid formation. Using hydrophilically coated ULA plates, EOC cell lines can be forced into spheroid form (Fig. 1B). After a growth period as spheroids, replating the cells on standard TC plastics allows the cells to reattach via the dormant-to-proliferative metastatic switch described above. Spheroids that have reattached to standard adherent TC plastics will be referred to as readhered or readherent cells through the remainder of this manuscript.

TMT labeling is a quantitative MS method with peptide samples from different biological replicates chemically labelled with isobaric tags. The mass tag is cleaved during high energy collision–induced dissociation, allowing identification and quantification of the peptides. The mass tags for each peptide were quantified at the MS2 level. Finally, peptide spectra are matched to known proteins for identification (17, 43). This method quantifies between different experimental conditions within the same MS run. Therefore, we TMT-labeled biological replicates of OVCAR8 EOC cells from three growth conditions, combined those samples, and compared protein and phosphoprotein expression levels from the conditions based on the transitions of interest: adherent-to-spheroid and spheroid-to-readherent. We chose the OVCAR8 cell line for our investigation for numerous reasons. OVCAR8 is a well-established and robust model for EOC metastasis, having been published previously in various journals, including transcriptomics and MS (44, 45). Further, OVCAR8 are ideal for studying spheroid morphology, as they have a relatively thick extracellular matrix that leads to formation of tightly bound spheroid cells that are easily visualized. Indeed, OVCAR8 cells are known to overexpress cell movement and migration-associated genes (46, 47), making them ideal for studying the metastasis process.

Principal component analysis and volcano plots showed clear separation of the proteome and phosphoproteomes of the three growth states in OVCAR8 cells (supplemental Fig. S1). To test for the robustness of our data analysis, we evaluated multiple normalization methods for both the proteome and phosphoproteome and decided to use median-centered z-score normalization. Histograms of intensity readings versus number of proteins for each replicate show that both the proteomics (supplemental Fig. S2) and the phosphoproteomics (supplemental Fig. S3) datasets are normally distributed. We identified 7828 proteins (supplemental Table S1), with 3457 proteins changed significantly in abundance between conditions (FDR < 0.05, Fig. 1, F and G and supplemental Table S2). We then sequentially performed phosphoenrichment by two methods, TiO2 and Fe-IMAC, and identified nearly 10,000 unique phosphorylation sites (supplemental Table S3), including 3813 significantly changed in abundance between all three conditions (Fig. 1, H and I and supplemental Table S4). Phosphorylation events were detected on 38% of proteins identified in the proteome (supplemental Fig. S1G). These results were quantified, normalized, and enriched pathways for each transition identified using GSEA.

Proteomic Reorganization During the Adherent to Spheroid Transition

As expected, the transition from adherent to spheroid cells was accompanied by major rearrangement of the proteome and phosphoproteome. Of the 3457 significantly changed proteins, 2827 were significantly changed in abundance between adherent and spheroid conditions (supplemental Table S2), with 735 changed at least 1.3-fold in abundance in spheroids relative to adherent cells (supplemental Table S5). Among the phosphorylation sites identified in phosphoproteomics, 3024 were significantly changed in abundance between adherent and spheroid conditions (supplemental Table S4), with 2340 greater than 1.3-fold changed in abundance (supplemental Table S6). As we were interested in proteome- and phosphoproteome-wide changes in pathway signaling, we focused our further analysis to include even those proteins with significant but small changes (FDR < 0.05, no fold-change cut-off). To identify the major pathways altered between metastatic states, we performed GSEA analysis (33, 48) on all 7828 proteins identified.

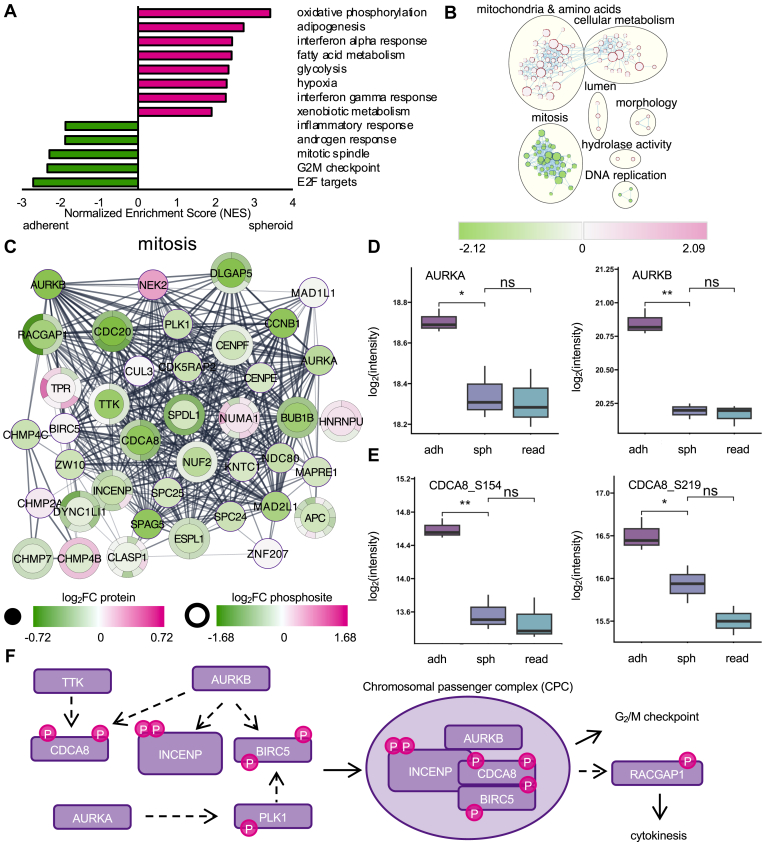

First, the H: hallmark gene set was used to identify the biological processes altered between adherent and spheroid states. Of the 50 gene sets, six were excluded from our analysis for containing fewer than ten genes. From the remaining 44 hallmark gene sets, 13 gene sets were significantly altered (FDR < 0.05, normalized enrichment score (NES) > 1.8). Oxidative phosphorylation (NES = 3.41, 124/200 genes) was the most significantly enriched gene set in spheroids, while E2F targets (NES = −2.71, 129/200 genes) was the most enriched in adherent cells (Fig. 2A, supplemental Tables S7, and S8). Notably, several energy and metabolism related gene sets were enriched in spheroids relative to adherent cells, including hypoxia (NES = 2.29, 69/200 genes) and glycolysis (NES = 2.34, 84/200 genes). In addition to E2F targets, the cell cycle related pathways G2M checkpoint (NES = −2.34, 109/200 genes) and mitotic spindle (NES= −2.29, 97/199 genes) were enriched in adherent cells, reflecting the dormant nature of spheroids.

Fig. 2.

GSEA analysis of OVCAR8 EOC metastasis model reveals AURKB regulation of cell cycle during the adherent-to-spheroid transition.A, enrichment of hallmark gene sets with FDR <0.05 and NES >1.8 in adherent (green) versus spheroid (pink) conditions. B, enrichmentMap pathway analysis of OVCAR8 adherent versus spheroid cells. Summary of GSEA pathway enrichment results performed using dataset MSigDB C5 Gene ontology (GO) terms. Each circle corresponds to a significantly enriched term from the C5 datasets. Green indicates negative enrichment, while pink corresponds to positive enrichment. Overarching terms are labeled within the figure. C, STRING analysis of proteins enriched in at least 20 pathways identified in mitosis grouping in (B). Inner circles indicate log2FC in protein abundance. Outer circles indicate log2FC in protein phosphorylation, with multiple phosphosites indicated within the same circle. Pink indicates increases in abundance and green indicates decreases in abundance, in spheroids relative to adherent cells. Figure created in Cytoscape with STRING and Omics Visualizer add-ons. D, representative box plots of changes in abundance of AURKA and AURKB. E, representative box plots of changes in abundance of AURKB targets CDCA8_S154 and CDCA8_S219. F, outline of the Aurora kinase pathway and formation of the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC). Dashed arrows indicate phosphorylation events. AURK, Aurora kinase; EOC, epithelial ovarian cancer; FC, fold change; FDR, false discovery rate; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; NES, normalized enrichment score.

Next, we expanded the GSEA analysis to the C5: ontology gene sets, which includes all Gene Ontology gene sets (Fig. 2B). As the C5 dataset includes over 15,000 gene sets, we analyzed gene sets with between 10 to 10000 genes, leaving 5087 gene sets in our analysis. To best interpret the pathways identified, we analyzed the data using EnrichmentMap in Cytoscape (37, 49). This analysis revealed mitochondrial proteins and proteins involved in amino acids metabolism (40 gene sets) and cellular metabolism (24 gene sets) as the most enriched areas in spheroids, while proteins involved in mitosis (40 gene sets) were the most enriched in adherent cells (Fig. 2B). As the nondividing nature of spheroids has been noted previously (10), we more closely investigated changes in proteins involved in mitosis in spheroids versus adherent cells.

Using the information from Cytoscape, we identified the proteins (nodes) with the most connections (edges) among the mitosis grouping, which we considered as potential drivers of altered cell cycle in spheroids. Among those nodes connected with at least 20 edges in the dataset, we built a network using data from STRING (Fig. 2C) (50). From these candidate proteins, we identified AURKB as the most connected protein, as it was connected to 37 of the 40 pathways in the mitosis grouping. AURKB, along with the related Aurora kinase A, was significantly reduced in abundance in spheroids relative to adherent cells (Fig. 2D). For this reason, we added Aurora kinase A to the STRING network despite not meeting the 20-edge cut-off. Similarly, several AURKB substrates were altered in phosphorylation (Figs. 2E and S4), indicating that AURKB activity is modified in spheroids. AURKB is the effector protein of the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC), which includes the proteins Borealin (CDCA8), Survivin (BIRC5), and inner centromere protein (51), all of which were similarly highly connected among the mitosis proteins (Fig. 2, C and F). Further, we found downregulation of the upstream CPC regulators dual specificity protein kinase TTK (TTK) and Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1), and of the CPC target Rac GTPase–activating protein 1 (RACGAP1) (Fig. 2, C and F). Thus, as previous studies have shown stalling of spheroids in G2/M phase (10), we here report that AURKB-mediated downregulation of G2-M phase is likely responsible for the dormant state of EOC spheroids.

Proteomic Reorganization During the Spheroid-to-Readherent Transition

Following our analysis of the adherent-to-spheroid transition characteristics, we next investigated the pathways regulating the transition from spheroid cells to readherence. Of the 3457 proteins that significantly changed in abundance, 1007 proteins were significantly altered in readherent cells relative to spheroids (supplemental Table S2). Further, 73 proteins were significantly altered in abundance at least 1.3-fold in readherent cells relative to spheroids (supplemental Table S5). Among the phosphorylation sites identified, we found 1343 phosphosites significantly changed in abundance between readherent cells and spheroids, with 1000 of those sites changed by at least 1.3-fold (supplemental Table S6). We noted that, on a phenotypic level, the readherent cells more closely resembled spheroids than adherent cells, with only a small number of the cells attached to the plate while the majority of cells remain within the intact spheroid cluster (Fig. 1E), and therefore the presence of many cells still in spheroid-like clusters is potentially obscuring more fine-tuned readherence signals.

As with the adherent-to-spheroid transition, we were interested in which major pathways were upregulated and downregulated during the spheroid-to-readherent transition. To investigate this, we again used GSEA analysis of the 7828 identified proteins (supplemental Table S1), comparing the levels of these proteins in spheroid versus readherent conditions (Fig. 3). We identified 15 significantly enriched (FDR < 0.05, NES > 1.8) gene sets, ten of which were enriched in readherent cells and five in spheroids (supplemental Tables S9 and S10). The most enriched gene sets were MYC targets v1 (NES = 2.78, 140/200 genes) and interferon gamma response (NES = −2.23, 62/200 genes) in spheroids and readherent cells, respectively (Fig. 3A). Similarly, we again used the C5: ontology gene sets to investigate pathways with major changes in protein abundance during the readherence process (Fig. 3B). Here, proteins involved in transcription and translation (85 gene sets) and DNA repair (39 gene sets) were the most enriched processes in spheroids, while lipid metabolism (90 gene sets), and immune response (61 gene sets) were enriched in readherent cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

GSEA analysis of OVCAR8 EOC metastasis model during the spheroid-to-readherent transition.A, enrichment of hallmark gene sets with FDR <0.05 and NES >1.8 in readherent (green) versus spheroid (pink) conditions. B, EnrichmentMap pathway analysis of OVCAR8 readherent versus spheroid cells. Summary of GSEA pathway enrichment results performed using dataset MSigDB C5 gene ontology (GO) terms. Each circle corresponds to a significantly enriched term from the C5 datasets. Green indicates negative enrichment, while pink corresponds to positive enrichment. Overarching terms are labeled within the figure. C, STRING analysis of proteins enriched in at least ten pathways identified in mitosis grouping in (B). Inner circles indicate log2FC in protein abundance. Outer circles indicate log2FC in protein phosphorylation, with multiple phosphosites indicated within the same circle. Pink indicates increased abundance and green indicates decreased abundance, in readherent cells relative to spheroids. Figure created in Cytoscape with STRING and Omics Visualizer add-ons. EOC, epithelial ovarian cancer; FC, fold change; FDR, false discovery rate; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; NES, normalized enrichment score.

Surprisingly, we also saw enrichment of mitosis pathways in spheroids relative to readherent cells (Fig. 3B, 18 gene sets), though not to the same extent as in adherent cells relative to spheroids (Fig. 2). To investigate this further, we again used STRING to build a network of the most connected nodes in the mitosis grouping and found similar nodes to those found in the adherent-to-spheroid transition: AURKB was connected by 11 edges, as were BIRC5 and CDCA8, while inner centromere protein, TTK, and PLK1 were connected by 12 edges each (Fig. 3C).

Total Proteomic Reorganization During Metastatic Steps

In addition to identifying the gene sets enriched in each transition, we were also interested in identifying pathways that are differentially upregulated and downregulated based on growth conditions; that is, which gene sets show significant changes between adherent and spheroid conditions (Fig. 2), but also between spheroid and readherent conditions (Fig. 3). First, clustering of the proteomics data showed five distinct clusters between adherent, spheroid, and readherent cells (supplemental Fig. S1H). The largest of those clusters includes proteins decreased in abundance in spheroids and readherent cells, relative to adherent cells, corresponding to mitosis pathways active in adherent cells. Among the two smaller clusters upregulated in spheroid and readherent cells relative to adherent cells, both related to changes in cellular metabolism pathways: sugars and fatty acid metabolism, respectively (supplemental Fig. S1H). To investigate these further, we also compared enrichment patterns of the Hallmarks pathways. Thus, we compared the enrichments of different pathways in combination, considering the possible combinations of enrichment patterns; if a particular pathway was upregulated in spheroids relative to both adherent and readherent cells, it would follow a pattern of OFF-ON-OFF, while a pathway downregulated in spheroids relative to both adherent and readherent cells follows ON-OFF-ON. Investigating these patterns may help elucidate pathways involved in EOC transition steps. The only gene set that followed a clear ON-OFF-ON pattern was the inflammatory response, which was enriched in adherent cells relative to spheroids (NES = −1.88, 23/200 genes) and in readherent cells relative to spheroids (NES = −2.14, 23/200 genes) (supplemental Tables S7–S10). Notably, hypoxia (NES = −1.95, 69/200 genes) and oxidative phosphorylation (NES = −1.95, 124/200 genes) were enriched in readherent cells relative to spheroids, but also in spheroid cells relative to adherent cells (OFF-ON-ON) (supplemental Tables S7–S10). The enrichment of these pathways in readherent cells relative to spheroids indicates that these pathways are further upregulated in readherent cells, beyond the baseline change that occurs during the adherent-to-spheroid transition. In contrast, some pathways that were downregulated during the adherent-to-spheroid transition remained downregulated during readherence (ON-OFF-OFF): E2F targets (NES = 2.46, 129/200 genes) and G2M checkpoint (NES = 2.31, 109/200) gene sets were both enriched in adherent cells relative to spheroids and spheroids relative to readherent cells (supplemental Tables S7–S10). We did not find any gene sets significantly enriched in spheroids (OFF-ON-OFF) in both comparisons.

Hypoxic Environments in Spheroids

As the GSEA results had indicated hypoxia in both spheroid and readherent cells, we were interested in investigating this relationship further. Reduced oxygen availability affects glucose metabolism in cells (52, 53). Cells deprived of oxygen rely on anaerobic respiration, causing increased glucose uptake and consumption to supply the cell with adequate glucose and meet energy demands. Hypoxia-induced changes in glucose metabolism have been linked to the progression of cancer and other diseases (53). The protein kinase AKT forms an important link between hypoxia and glucose deprivation: insulin stimulation results in mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 2 and AKT-mediated increase in glucose uptake via glucose transporters, GLUT1 and GLUT4 (54). AKT additionally can activate hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) signaling and is antiapoptotic, protecting the cell during hypoxic stressors (55, 56). Therefore, we were interested in elucidating the role of this link in spheroid formation and readherence. Hypoxia was identified as one of the most changed pathways in the adherent to spheroid transition, and cells remained hypoxic during the readherence phase. We confirmed the hypoxic nature of spheroids and readherent cells by Western blotting for the hypoxia markers HIF-1α, a subunit of the HIF-1 dimer, as well as the erythropoietin receptor (57). While erythropoietin receptor abundance did not change, we found significant 1.5-fold upregulation of HIF-1α in both spheroids and readherent cells, relative to adherent cells (supplemental Fig. S5, A and B). HIF-1 may promote gene expression in glucose metabolism and angiogenesis, allowing these spheroid and readherent cells to adapt to low oxygen levels (58). Therefore, we used this fold change (FC) data in combination with proteomics and phosphoproteomics to create a STRING network of changes in HIF-1 and identified changes in abundance of proteins and phosphoproteins in that network (supplemental Fig. S5, C and D). Together, these results indicate that EOC spheroids are indeed hypoxic environments that must rely on alternate pathways for energy production. Indeed, spheroid formation has been linked to decreased oxygen availability in the centers of spheroids, in a spheroid size-dependent manner (59). Our data shows that proteomic changes adapting to increased oxygen levels during readherence are trailing behind the cellular adhesion, and cellular markers of hypoxia remain upregulated.

Phosphoproteomic Changes During EOC Metastasis

Large-scale proteomic analysis is a powerful tool to further scientific understanding of cell signaling. However, changes in protein abundance are not the only drivers of protein activity changes. Many proteins are dynamically regulated by posttranslational modifications such as acetylation, methylation, or phosphorylation, where additions may lead to increased or decreased protein activity, depending on the cellular context (60, 61, 62). Indeed, AKT, a known driver of EOC metastasis (10, 63), is regulated by phosphorylation, where phosphorylation of Thr308 is required for activation of the AKT1 isozyme (61). Thus, to build further on our understanding of proteomic changes during EOC metastasis, we expanded our analysis to include phosphoproteomic analysis of EOC cells in the three metastatic conditions, as above.

Phosphoproteomic Changes During the Adherent-to-Spheroid Transition

As we were interested in the overall phosphoproteomic landscape in the various growth conditions, we performed two complementary analyses to investigate changes in phosphorylation: Coral and KSEA (Fig. 4, A and B and supplemental Fig. S6). Coral uses FC data to show changes in the kinome, mapping them onto the kinome tree (35), while KSEA uses known substrates to predict kinase activity (34). For the Coral analysis, we used the lists of significantly upregulated and downregulated proteins from the proteomic analysis to highlight the global changes in kinase expression during the adherent-to-spheroid transition (supplemental Fig. S6A). Of the 522 known human kinases (64), 277 kinases were identified, with 105 kinases significantly altered in abundance (supplemental Fig. S6C). Notably, Coral analysis revealed downregulation of kinases in spheroids, with 32 of the 105 kinases downregulated, compared to 23 upregulated and 50 with smaller than 1.3-FCs in abundance (supplemental Fig. S6C). The kinase most reduced in abundance was AURKB (FC = 1.57 down) and the most upregulated was Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 3 (FC = 1.71 up) (supplemental Table S11).

Fig. 4.

KSEA analysis reveals ROCK1 as a downstream driver of AURKB in EOC metastasis model.A and B, KSEA analysis results of kinase activity changes during the shift from (A) adherent to spheroid and (B) spheroid-to-readherent cultures of OVCAR8 cells. KSEA analysis was performed using the PhosphoSitePlus kinase-substrate dataset. Only kinases with five or more substrates identified in our analysis, p < 0.05, and kinase z-scores of at least 1.5 are shown. C, Kaplan–Meier curve of EOC patients with high (red) or low (black) ROCK1 expression. Figure generated in KM-plotter. D, STRING visualization of top 20 ROCK1 interactors identified from the literature. Inner circles indicate log2FC in protein abundance. Outer circles indicate log2FC in protein phosphorylation, with multiple phosphosites indicated within the same circle. Pink indicates increases in abundance, and green indicates decreases in abundance, in spheroids relative to readherent cells. Figure created in Cytoscape with STRING and Omics Visualizer add-ons. E, Box plot of ROCK1 abundance in EOC metastasis model states. F, Box plot of phosphorylation status of the ROCK1 substrate MAPK8IP3 (JIP3) at S365 in EOC metastasis model states. G, representative model of ROCK1-mediated regulation of myosin by the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC). H, representation of ROCK1 protein domains and regulation during EOC metastasis. During spheroid formation, hypoxia signaling leads to exchange of GDP for GTP binding of RhoA. GTP-bound RhoA interacts with the RHO-binding domain of ROCK1, leading the kinase to adopt an open, active conformation, and phosphorylate MAPK8IP3 at Ser365. Phosphorylated MAPK8IP3 further signals for cytoskeletal reorganization. AURK, Aurora kinase; EOC, epithelial ovarian cancer; FC, fold change; KSEA, kinase substrate enrichment analysis; MAPK8IP3, mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 interacting protein 3; RHOA, Ras homolog family member A; ROCK1, Rho-associated kinase 1.

Although many kinases are regulated by abundance, regulation by localization or posttranslational modifications is also common. To account for this, we complemented the Coral analysis of our phosphoproteomics results with a KSEA analysis of known kinase substrates to deduce kinase activity on known substrates. Although some kinases were themselves not identified in the Coral analysis, KSEA can infer the activity based on the phosphorylation of downstream substrates. For this analysis, we limited the kinases we identified to include only those kinases with at least five substrates identified in phosphoproteomics, z-score cut-offs of 1.8 or −1.8, and significance cut-offs of p < 0.05. KSEA identified five kinases with increased activity in spheroids (p < 0.05, z-score > 1.8) and five kinases with reduced activity in spheroids (p < 0.05, z-score < −1.8), relative to adherent cells (Fig. 4A and supplemental Table S13). The most significantly changed kinase activity identified was cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) (p < 0.0001, z-score = −7.20, 91 substrates), which shows reduced activity in spheroids relative to adherent cells, and was also identified as reduced in abundance in Coral analysis (supplemental Fig. S6, A and C). In contrast, the kinase identified as most increased in activity in spheroids was serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (SGK1) (p < 0.001, z-score = 3.29, five substrates, supplemental Table S13), which was not identified as changed in abundance in Coral as it was not identified in the MS analysis. Specifically, the SGK1 substrate N-Myc downstream–regulated 1 had 8.86-fold increased phosphorylation in spheroids relative to adherent cells, driving the identification of the SGK1 kinase (supplemental Table S13).

Phosphoproteomic Changes During the Spheroid-to-Re-adherent Transition

As with the adherent-to-spheroid transition, we were interested in which kinases showed increased or decreased activity during the spheroid-to-readherent transition. We again used Coral to map the significantly changed kinases from the proteomic identification and found only minor changes in kinase abundance in the spheroid-to-readherent transition (supplemental Fig. S6B). In total, there were only three upregulated kinases, and five downregulated kinases during the spheroid-to-readherent transition (supplemental Fig. S6, B and C and supplemental Table S12). Two of the three upregulated kinases were also upregulated during the adherent-to-spheroid transition, with only death-associated protein kinase 1 specific to the spheroid-to-readherent transition. Among the kinases decreased in abundance during readherence, serine/threonine-protein kinase RIO3 (RIOK3) and PAS domain–containing serine/threonine-protein kinase (PASK) were increased in abundance in spheroids relative to adherent cells. Lastly, RAC-beta serine/threonine-protein kinase (AKT2) was not altered in abundance in the adherent-to-spheroid transition but was downregulated in readherent cells. Thus, while many kinases are downregulated in abundance in spheroids, further changes in abundance occur during readherence, and some kinases remain inactive.

We again complemented the Coral analysis with KSEA to identify potential kinases driving the spheroid-to-readherent transition. KSEA identified eight kinases with altered activity during readherence: three kinases were inferred to have increased activity in readherent cells (p < 0.05, z-score > 1.5) and five showed decreased activity in readherent cells (p < 0.05, z-score<−1.5) (Fig. 4B and supplemental Table S14). Both the most upregulated and most downregulated kinases, Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 (HIPK2) (p < 0.001, z-score = 3.36) and CDK7 (p < 0.01, z-score = −2.80), respectively, were not identified in Coral. Interestingly glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), a major substrate of the EOC metastasis driving kinase AKT, was identified with decreased substrate phosphorylation by KSEA (p < 0.05, z-score = −2.00, supplemental Table S14). GSK-3β was also significantly decreased in abundance (supplemental Fig. S6B and supplemental Table S11). GSK-3β activity is downregulated by phosphorylation at S9 by AKT (12, 65), which agrees with the results shown here.

Total Phosphoproteomic Reorganization during Metastatic Steps

As with the proteomic dataset, we were interested in comparing our phosphoproteomic results in the adherent-to-spheroid and spheroid-to-readherent transitions both separately and in combination. Globally, comparing the Coral results shows an obvious shift from upregulated kinases in adherent cells to downregulation of those kinases in spheroids, then a move toward reactivation during the readherence process. This is seen most clearly in the color changes from supplemental Fig. S6, A and B, where the kinome map goes from mostly downregulated during spheroid formation (supplemental Fig. S6A) to more upregulated during readherence (supplemental Fig. S6B). Surprisingly, however, this is different from what is indicated from the KSEA analysis, which showed similar numbers of kinases being upregulated and downregulated during each transition (Fig. 4, A and B).

Further, we investigated the clustering of cellular pathways between the three cellular states. We identified four similarly sized clusters of phosphosites, with intensity-based clustering (supplemental Fig. S1I). The largest of these clusters includes proteins increased in phosphorylation in readherent cells relative to both spheroids and adherent cells, where spheroids had intermediate levels of phosphorylation, with enrichment of transcription- and translation-related pathways. Similarly, another cluster included phosphosites decreased in abundance in readherent cells and increased in adherent cells, with intermediate levels in spheroids; mitosis-related pathways were enriched in this cluster. The two remaining clusters included phosphosites increased in abundance in spheroids and decreased in adherent cells as well as the opposite, with readherent cells having intermediate levels of phosphorylation in both clusters. The first of these clusters, with high levels in adherent cells and low levels in spheroids, was enriched in cytoskeletal organization, while the other, with low levels in adherent cells and high levels in spheroids, was enriched in pathways related to transcription and mRNA splicing. Together, these data reflect the complexity of regulation of phosphorylation between EOC metastasis states.

Pathway Correlation in Proteomic and Phosphoproteomic Clusters

Among the clusters identified in adherent, spheroid, and readherent growth conditions, there was some overlap between the proteome and the phosphoproteome (supplemental Fig. S1, H and I). Mitosis-related proteins were significantly enriched in the largest cluster of the total proteome data as well as in one of the clusters of protein phosphosites. In both cases, those proteins followed similar patterns: both proteins and phosphosites levels were higher in adherent cells than in the other growth conditions. Surprisingly, however, despite minimal changes in abundance of this cluster of proteins, the phosphosites were further decreased in readherent cells, relative to both spheroids and adherent cells. Thus, changes in mitosis between EOC metastasis steps may occur at the phosphoprotein level separately from the protein level.

ROCK1 is a Key Driver of Spheroid Formation and Readherence

During our KSEA analysis, we noted two kinases that have no previously described role in EOC state transition. HIPK2 and ROCK1 showed reversal of activity in each shift (Fig. 4, A and B). HIPK2 activity follows an ON-OFF-ON trend, where it decreases during the adherent to spheroid transition (p < 0.0001, z-score = −4.41), and it is then reactivated when spheroids readhere (p < 0.001, z-score = 3.36). In contrast, ROCK1 activity follows an opposite OFF-ON-OFF trend, with increased activity in spheroids relative to both adherent (p < 0.05, z-score = 1.87) and readherent cells (p < 0.05, z-score = −1.83). Notably, Kaplan–Meier curves show that high ROCK1 expression is associated with longer progression-free survival in EOC (Fig. 4C), and a ROCK1 inhibitor is readily available (66). Therefore, we considered that either of these proteins may regulate EOC metastasis by changes in downstream signaling and focused our further analysis on the potential role of ROCK1 in EOC metastatic behavior.

We first used STRING to examine the network of proteins regulating ROCK1, using ROCK1 as a base and STRING to identify the 20 closest interactors (Fig. 4D). We then used the Omics Visualizer app (38) in Cytoscape to map changes in protein and phosphosite abundance among ROCK1 interactors between adherent and spheroid conditions. Although ROCK1 itself was not changed in abundance (Fig. 4E), mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 interacting protein 3 (MAPK8IP3, JIP3) phosphorylation at S365, the ROCK1 target site (67), was significantly increased 3.85-fold in spheroids relative to adherent cells (Fig. 4F), while multiple ROCK1 targets had decreased phosphorylation in readherent cells relative to spheroids (supplemental Fig. S7).

Since we identified ROCK1 as a potential driver of metastatic behavior in the KSEA analysis (Fig. 4, A and B, supplemental Tables S13, and S14), we decided to test if ROCK1 inhibition with a well-characterized inhibitor (68, 69, 70), leads to phenotypic changes during the adherent to spheroid-to-readherent steps. Interestingly, ROCK1 is a potential downstream effector of AURKB activity, where the CPC, through various other effector proteins, regulates Ras homolog family member A (RHOA) activity, altering phosphorylation of ROCK1 targets and ultimately controlling myosin (Fig. 4G). In normal conditions, RHOA is bound to GDP and inactive, while during hypoxia GDP is exchanged for GTP, activating RHOA binding of ROCK1 (Fig. 4H) (71, 72). GTP-bound RHOA interacts with the RHO-binding domain of ROCK1, causing ROCK1 to adopt an open, active conformation (Fig. 4H). The ROCK1 small molecule inhibitor Y-27632 binds competitively to the ATP-binding site of the ROCK1 kinase domain, preventing the phosphorylation of ROCK1 targets. Y-27632 has been shown in previous studies to bind both ROCK1 and ROCK2, with a slight preference for ROCK1 (66, 73), and effectively reduces phosphorylation of ROCK1 substrates in inhibited cells (69).

To examine the role of ROCK1 in spheroid formation and dispersion, we imaged cells treated with the ROCK1 inhibitor Y-27632 and measured the ability of inhibitor-treated and PBS-treated control cells to form spheroids (Fig. 5A). As expected, ROCK1-inhibited spheroids are markedly different from control spheroids (Fig. 5, A and B). We used four different parameters to quantify the structural differences: circularity, perimeter, area, and diameter (Fig. 5B). Previous studies examining the usefulness of each of these measures of spheroid formation have shown the potential for each in experimental conditions (74, 75, 76). The parameters directly related to spheroid size relay two pieces of key information: cell compaction and cell proliferation, where smaller area, perimeter, or diameter indicate more compact cells, and an increase in any of these values over time reflects cell proliferation. As a complement to this, circularity reflects cells morphology and aggregation. While all four of these measures show significant differences between control and ROCK1-inhibited spheroids, diameter is the only parameter that remains statistically significant on the third day of spheroid formation (Fig. 5B), where the diameter of PBS-treated control spheroids and Y-27632–treated spheroids are 535 ± 12 μm and 599 ± 17 μm, respectively. For both PBS and Y-27632 treatments, these are major decreases from the initial diameters of 752 ± 17 μm and 851 ± 14 μm, respectively, after 24 h of spheroid formation (Fig. 5B). Similarly, the area of PBS- and Y-27632–treated spheroids decreased from 445,232 ± 25,675 μm2 and 586,920 ± 15,445 μm2, respectively, after 24 h to 233,859 ± 10,438 μm2 and 291,430 ± 13,562 μm2, respectively, after 72 h. Despite the increases in area and diameters of Y-27632–treated spheroids relative to control spheroids, spheroid perimeters remained similar over the 3-day period of spheroid formation, with only a slight decrease from 3606 ± 84 μm in PBS-treated cells to 3222 ± 52 μm in Y-27632–treated cells in the first 24 h of spheroid formation, and no significant differences in perimeter at the 48- and 72-h timepoint (Fig. 5B). This changed trend of area and diameter from perimeter can likely be attributed to the circularity of the spheroids. Circularity is a unitless measure between 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 representing rounder objects. After 24 h, Y-27632–treated spheroids had significantly higher circularity than PBS-treated spheroids, with mean circularities of 0.712 and 0.434, respectively (Fig. 5B). After 48 h, Y-27632 spheroids were still significantly more circular than PBS spheroids, 0.813 and 0.696, an increase in circularity for both conditions (Fig. 5B). Lastly, after 72 h of treatment and spheroid formation, there was no significant difference in circularity between conditions (Fig. 5B). Thus, as Y-27632–treated spheroids are more circular than control spheroids, the ROCK1 inhibition leads to maintenance of similar perimeters despite the spheroids themselves being larger than control spheroids. Overall, these data indicate that ROCK1 inhibition leads to formation of spheroids that are larger and rounder than control spheroids.

Fig. 5.

ROCK1 inhibition alters spheroid formation and readherence.A, representative images of OVCAR8 epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) spheroids treated with 5 μM Y-27632 ROCK1 inhibitor or equivalent volume of PBS at the time of plating (t = 0 h, not shown). Equal numbers of cells were grown on 96-well plates for 72 h, with imaging every 24 h. The scale bars represent 400 μm. B, quantification of spheroid formation parameters of spheroid cells (n = 3) during 72 h of spheroid formation. C, representative images of OVCAR8 EOC spheroids treated with 5 μM Y-27632 ROCK1 inhibitor or equivalent volume of PBS at the time of spheroid formation. Equal numbers of cells were grown on 96-well plates for 72 h, then replated on TC-treated 96-well plates and imaged after 24 h and 48 h. The scale bars represent 400 μm. D, quantification of spheroid dispersion parameters of readherent cells (n = 3) at 24 h and 48 h, following readherence. p-values were calculated in GraphPad Prism by two-way repeated measures ANOVA, with asterisks to indicate significance (ns, not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). ROCK1, Rho-associated kinase 1.

Similarly, we investigated the same spheroid formation parameters in two additional EOC cell lines: HeyA8 and ES-2. These cell lines have similar spheroid formation to OVCAR8 but different genetic backgrounds. In HeyA8 cells, although we did not find significantly altered spheroid circularity, as we saw in OVCAR8 spheroids (Fig. 5), we found similar trends in spheroid size (supplemental Fig. S8, A and B). Y-27632–treated spheroids had increased area relative to control PBS spheroids at all three of the 24-, 48-, and 72-h timepoints: 91,328 ± 1088 μm2, 109,755 ±1083 μm2, and 152,203 ±1490 μm2 versus 76,092 ± 690 μm2, 101,299 ± 1888 μm2, and 145,217 ± 3466 μm2 for PBS-treated spheroids (supplemental Fig. S8B). Similarly, Y-27632–treated HeyA8 spheroids had significantly increased diameters of 395.90 ± 5.39 μm, relative to control spheroid diameters of 365.12 ± 2.32 μm, at the 24-h timepoint (supplemental Fig. S8B). Finally, Y-27632 treatment increased the perimeters of HeyA8 spheroids after 24 h from 1316.35 ± 12.07 μm in control spheroids to 1416.40 ± 29.41 μm in Y-27632–treated spheroids. Surprisingly, despite the similarities between OVCAR8 and HeyA8 spheroids following ROCK1 inhibition, we saw no significant effect of Y-27632 on spheroid formation in ES-2 EOC cells (supplemental Fig. S9), indicating that the role of ROCK1 in spheroid formation may be dependent on other factors involved in EOC metastasis.

Next, we replated OVCAR8 spheroids treated with Y-27632 on TC-treated plates and allowed the cells to readhere (Fig. 5, C and D). At 24- and 48-h post replating, the readherent cells were imaged and two parameters quantified: dispersion area and dispersion radius (74, 77). After 48 h of readherence, Y-27632–treated spheroids had significantly larger dispersion radii than control spheroids, 423 ± 31 μm and 251 ± 19 μm, respectively, although the total dispersion area was not significantly different (Fig. 5, C and D). Similarly, in HeyA8 cells, after 24 h of readherence, the dispersion area and radius both increased significantly from 24.7 ± 2.71 × 105 μm2 and 639 ± 38 μm in PBS-treated cells to 30 ± 1.45 × 105 μm2 and 711 ± 21 μm in Y-27632–treated readherent cells (supplemental Fig. S8, C and D). To determine whether this was a consequence of ROCK1 inhibition during spheroid formation versus during the readherence process, we also allowed 72 h of spheroid formation to occur without inhibitors and added Y-27632 or PBS control at the time of replating for the spheroid-to-readherence transition. We again saw significantly larger dispersion area and radius measurements for ROCK1-inhibited readherent cells: after 24 h of dispersion, Y-27632–treated readherent cells had a dispersion area of 431 ± 40 μm2, more than double that of the PBS-treated control cells, 148 ± 35 μm2, and dispersion radii of 173 ± 10 μm, a significant increase from the 104 ± 15 μm radii of PBS-treated readherent cells (supplemental Fig. S8). Similarly, after 48 h of dispersion, control readherent cells had a dispersion area of 425 ± 49 μm2, significantly smaller than the 726 ± 37 μm2 dispersion area of Y-27632–treated readherent cells, and dispersion radii of 240 ± 25 μm, again significantly smaller than the 372 ± 15 μm dispersion radii of Y-27632–treated readherent cells (supplemental Fig. S10). Lastly, to determine whether the changes in dispersion of Y-27632–treated readherent cells was caused by increased proliferation, we measured cell proliferation by CCK-8 assay. The CCK-8 showed no significant difference in cell proliferation between PBS- and Y-27632–treated readherent cells 72 h after readherence of OVCAR8 cells (supplemental Fig. S10C) or 48 h after readherence of HeyA8 (supplemental Fig. S8E) and ES-2 cells (supplemental Fig. S9E). Together, these results indicate that ROCK1 inhibition creates larger, rounder spheroids and leads to quicker, more aggressive, readherence of spheroids.

Discussion

Progression Through the Metastatic Steps of EOC Cells is Accompanied by Major Proteomic and Phosphoproteomic Changes

EOC is an aggressive cancer with high mortality and recurrence rates. EOC cells metastasize by detaching from the primary tumor site and forming spheroid structures that travel and reattach to form a secondary tumor site (9, 78). Both the adherent-to-spheroid and spheroid-to-readherent transitions are accompanied by major rearrangements of the proteome. We observed, in agreement with previously published proteomic studies, that proteins involved in energy metabolism are among the most upregulated pathways in the adherent-to-spheroid shift (79). Some pathways that are reduced in spheroid cells include mitotic cell cycle proteins, cell adhesion, and translation initiation, indicating that cells are indeed moving from proliferative state to a dormant cell state. EOC tumors were previously shown to enter a hypoxic state induced by the limited oxygen supply in growing tumors lacking blood vessels (80). Our data shows that proteins involved in glucose metabolism and hypoxia pathways are upregulated in spheroid cells and the hypoxia marker HIF-1α, which regulates glucose uptake and metabolism (52), is significantly increased in spheroid cells. HIF-1α was previously identified as a driver of EOC pathogenesis, and knockdown of HIF-1α induced apoptosis in Human EOC SKOV3 cells (81). Our proteomics data confirms that hypoxia is one of the most enriched pathways during the adherent-to-spheroid switch in OVCAR8 cells. Interestingly, hypoxia markers and pathways remain enriched upon reattachment, indicating the adaptation of the proteome lags behind the increased oxygen supply (80). On the other hand, E2F targets and pathways involved in DNA replication and cell division are downregulated in the adherent-to-spheroid switch, which agrees with the premise that cells enter a nondividing, dormant state. It is notable that the proteome of readherent cells more closely resemble that of spheroid cells rather than adherent cells and many changes are further accentuated when moving from adherent to spheroid-to-readherent states, such as oxidative phosphorylation and interferon alpha response. That is, several pathways, including hypoxia, remain upregulated in readherent cells. The explanation for this may be 2-fold: on the one hand, our cells were harvested after 72 h of incubation on TC-treated cells, which allows for a physical attachment of the spheroids to the plates, as shown in Figure 1. Nonetheless, many cells of the reattaching spheroids are still visibly in a spheroid state. To more closely observe proteomic changes during the reattachment process, single-cell transcriptomics or proteomics would reveal more detailed proteomic changes during attachment. A recent study in colorectal spheroids revealed major differences between inner, outer, and core spheroid layers (82), which could be applied to further understand proteomic changes in EOC spheroids. On the other hand, the attachment process may be directed by posttranslational modifications and alteration of protein activity, rather than changes in protein abundance. Indeed, our phosphoproteomic data revealed numerous changes that occur before proteomic changes in the dormant-to-proliferative switch.

The Dormant-to-Proliferative Shift in EOC is Driven by Changes in Kinase Activity

Previous studies showed that EOC cell metastatic behavior is driven by the oncogenic kinase AKT, where AKT is highly phosphorylated in dividing adherent states, but largely dephosphorylated and inactive during spheroid dormancy (10, 12, 63), indicating that metastatic behavior is driven by kinase activity, in addition to, or in place of changes in kinase and protein abundance. We did not note major changes in kinase abundance in our proteomic analysis but observed changes in downstream signaling pathways. We show that the activity of key cell cycle regulating kinases CDK1 and CDK2 is downregulated in spheroid cells compared to adherent cells. CDK1 downregulation by miR-490-3P was previously shown to reduce tumor proliferation of EOC models in mice (83), and high CDK1 expression predicts poor survival of EOC patients (84). Our data shows that CDK1 and CDK2 activity is high in adherent states, but reduced in spheroid and readherent states, indicating that CDK1 activity may primarily drive metastatic behavior in early stages of EOC pathogenesis. Upon reattachment, several kinase activities appear upregulated, as for example PLK3. PLK3 has been associated with contradicting roles in different cancers, including downregulation in head and neck carcinomas (85), hepatocellular carcinoma (86), and ovarian cancer (87). On the other hand, PLK3 overexpression is associated with poor prognosis in prostate and breast cancers (88, 89). Interestingly, PLK3 phosphorylates and destabilizes HIF-1α (90), indicating that while HIF-1α abundance is not reduced immediately upon reattachment, kinase signaling commenced to reduce the hypoxic response. Similarly, we found that protein kinase C alpha (PRKCA) activity increased during readherence. PRKCA is a known regulator of HIF-1α via the AKT-mammalian target of rapamycin pathway during hypoxia (91). AKT1 is an established driver for EOC metastatic behavior (10, 63, 77, 92), and as PRKCA regulates AKT1 phosphorylation at Ser473 (93), we deduce that the previously established changes in AKT1 activity may be driven by hypoxia, and the increased AKT1 activity upon reattachment may be driven by PRKCA.

AURKB and ROCK1 are Major Regulators of Metastatic Cell Proliferation

We analyzed the proteomes of OVCAR8 metastatic behavior in three steps from adherent to spheroid and to readherence phases. In our phosphoproteomic analysis, the ROCK1 was identified for following an OFF-ON-OFF pattern, wherein it is activated upon spheroid formation, and activity is subsequently reduced upon readherence. ROCK1 has been associated with multiple cellular functions, including actin cytoskeleton organization, extracellular matrix formation, cell adhesion, as well as proliferation and apoptosis. Our data shows that spheroids treated with a ROCK1 inhibitor have a more defined perimeter compared to untreated cells, yet are larger in area and diameter. A previous study showed that ROCK1 is required for cell adhesion and migration in non–small cell lung cancer (94). Similarly, our data shows that ROCK1 inhibition leads to reduced spheroid integrity, where spheroids disperse at a faster rate during reattachment, which agrees with ROCK1 function in cell adhesion. Similarly, ROCK1 inhibition led to increased breast cancer and metastasis (95). Interestingly, a previous study linked ROCK1 to hypoxia, where HIFs activate transcription of ROCK1, driving metastasis. Furthermore, another study showed that ROCK1 inhibition leads to increased AKT1 phosphorylation (96), which is in agreement with the inverse relationship between ROCK1 activity and AKT1 phosphorylation status and activity (10, 63, 77, 92).

The Aurora kinases are well-studied modulators of mitosis in cells. Mammalian AURKB was first identified based on homology to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Drosophila proteins, and it was identified as an essential protein for completion of cytokinesis (97). High levels of AURKB, however, can be detrimental, inducing multinucleation and polyploidy (98). Indeed, the same study was unable to produce stable overexpression of AURKB in cell lines lacking TP53 mutations (98). During cytokinesis, AURKB phosphorylates the RACGAP1, activating its activity toward RHOA (99). This creates an interesting link between our observations regarding ROCK1 and AURKB: when AURKB levels are low, as in spheroids, RACGAP1 is less active, leaving active GTP-bound RHOA available to activate ROCK1 activity (Fig. 6). Notably, RACGAP1 has also been linked to hypoxia, where it competes for binding to HIF-1 (100). High levels of ARNT (aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator), however, can outcompete RACGAP1 (100), and may be responsible for the hypoxic response we observed in both spheroids and readherent cells.

Fig. 6.

Summary of altered cell signaling in EOC metastasis.A, in adherent cells, modeling EOC primary tumors, AKT1 is phosphorylated and active in the cytoplasm. AURKB is expressed at a level necessary for formation of the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC) with INCENP, BIRC5, and CDCA8, and subsequent mitosis. MAPK8IP3 phosphorylation by ROCK1 is low, but ROCK1 is still activated by RHOA to phosphorylation SCRIB. Adherent cells are highly proliferative. B, in EOC spheroids, AKT1 phosphorylation is reduced. AURKB expression is low, reducing CPC formation. MAPK8IP3 pS65 is high, indicating increased RHOA/ROCK1 interaction. Cells in spheroids are dormant and not proliferating. C, in readherent EOC cells, modeling secondary tumors, AKT1 phosphorylation is increased for readherence to occur. AURKB levels remain similar to spheroid levels, as does MAPK8IP3 pS65, but SCRIB pS1378 is reduced. Outer readherent cells begin to proliferate, but interior cells are slow growing. AURK, Aurora kinase; EOC, epithelial ovarian cancer; MAPK8IP3, mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 interacting protein; RHOA, Ras homolog family member A; ROCK1, Rho-associated kinase 1.

In summary, our in-depth multiomics analysis showed that during metastatic behavior, cells undergo major proteomic and phosphoproteomic changes alongside phenotypic changes, which are driven by several kinases, summarized in Figure 6. We identified ROCK1 as a previously unknown regulator of spheroid integrity and AURKB as a regulator of cell dormancy in spheroids. Furthermore, our data indicates that many of the proteomic and phosphoproteomic changes may be related to hypoxia.

Data availability

All original code and data used in this analysis are publicly available at https://github.com/mfreder8/Frederick-et-al.-2023.

The proteomic data has been uploaded to the PRIDE database: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride

Project accession: PXD043220

Supplemental data

This article contains supplemental data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Farah Hasan, Tarana Siddika, Greg Gloor, and Patrick O’Donoghue for advice and critical discussion.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (to I. U. H. and S. S. C. L); Queen Elizabeth II Graduate Scholarship in Science and Technology (QEII-GSST) to M. I. F.; the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation (to I. U. H), and the Canadian Institute for Health Research (to I. U. H and S. S. C. L).

Author contributions

M. I. F., O. F. J. H., T. G. S., S. S. C. L., and I. U. H. conceptualization; M. I. F. and O. F. J. H. methodology; M. I. F. software; M. I. F. and J. H. K. validation; M. I. F., O. F. J. H., and J. H. K. formal analysis; M. I. F., O. F. J. H., and J. H. K. investigation; M. I. F. and O. F. J. H. data curation; M. I. F. and I. U. H. writing-original draft; M. I. F., O. F. J. H., T. G. S., S. S. C. L., and I. U. H. writing-review and editing; T. G. S., S. S. C. L., and I. U. H. supervision; T. G. S., S. S. C. L., and I. U. H. project administration; T. G. S., S. S. C. L., and I. U. H. funding acquisition.

Contributor Information

Shawn S.C. Li, Email: sli@uwo.ca.

Ilka U. Heinemann, Email: ilka.heinemann@uwo.ca.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Momenimovahed Z., Tiznobaik A., Taheri S., Salehiniya H. Ovarian cancer in the world: epidemiology and risk factors. Int. J. Womens Health. 2019;11:287–299. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S197604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devouassoux-Shisheboran M., Genestie C. Pathobiology of ovarian carcinomas. Chin J. Cancer. 2015;34:50–55. doi: 10.5732/cjc.014.10273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed A.A., Etemadmoghadam D., Temple J., Lynch A.G., Riad M., Sharma R., et al. Driver mutations in TP53 are ubiquitous in high grade serous carcinoma of the ovary. J. Pathol. 2010;221:49–56. doi: 10.1002/path.2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowtell D.D., Bohm S., Ahmed A.A., Aspuria P.J., Bast R.C., Jr., Beral V., et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer II: reducing mortality from high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:668–679. doi: 10.1038/nrc4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allemani C., Matsuda T., Di Carlo V., Harewood R., Matz M., Niksic M., et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391:1023–1075. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33326-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amin N., Chaabouni N., George A. Genetic testing for epithelial ovarian cancer. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020;65:125–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2020.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haunschild C.E., Tewari K.S. The current landscape of molecular profiling in the treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021;160:333–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uno K., Iyoshi S., Yoshihara M., Kitami K., Mogi K., Fujimoto H., et al. Metastatic voyage of ovarian cancer cells in ascites with the assistance of various cellular components. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:4383. doi: 10.3390/ijms23084383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correa R.J., Peart T., Valdes Y.R., DiMattia G.E., Shepherd T.G. Modulation of AKT activity is associated with reversible dormancy in ascites-derived epithelial ovarian cancer spheroids. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:49–58. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peart T.M., Correa R.J., Valdes Y.R., Dimattia G.E., Shepherd T.G. BMP signalling controls the malignant potential of ascites-derived human epithelial ovarian cancer spheroids via AKT kinase activation. Clin. Exp. Metast. 2012;29:293–313. doi: 10.1007/s10585-011-9451-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frederick M.I., Siddika T., Zhang P., Balasuriya N., Turk M.A., O'Donoghue P., et al. miRNA-dependent regulation of AKT1 phosphorylation. Cells. 2022;11:821. doi: 10.3390/cells11050821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samartzis E.P., Noske A., Dedes K.J., Fink D., Imesch P. ARID1A mutations and PI3K/AKT pathway alterations in endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:18824–18849. doi: 10.3390/ijms140918824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones S., Wang T.L., Shih Ie M., Mao T.L., Nakayama K., Roden R., et al. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling gene ARID1A in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Science. 2010;330:228–231. doi: 10.1126/science.1196333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo K.T., Mao T.L., Jones S., Veras E., Ayhan A., Wang T.L., et al. Frequent activating mutations of PIK3CA in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;174:1597–1601. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zecha J., Satpathy S., Kanashova T., Avanessian S.C., Kane M.H., Clauser K.R., et al. TMT labeling for the masses: a robust and cost-efficient, in-solution labeling approach. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2019;18:1468–1478. doi: 10.1074/mcp.TIR119.001385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi J., Snovida S., Bomgarden R., Rogers J. Thermo Fisher Scientific; Rockford, IL: 2017. Sequential Enrichment from Metal Oxide Affinity Chromatography (SMOAC), a Phosphoproteomics Strategy for the Separation of Multiply Phosphorylated from Monophosphorylated Peptides. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swaney D.L., Villen J. Enrichment of phosphopeptides via immobilized metal affinity chromatography. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot088005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hovey O., Zhong S., Kaneko T., Li S., Ezra S. quantitative proteomics approach to characterize cellular reprogramming. Search Life Sci. Literature. 2022 doi: 10.20944/preprints202211.0096.v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu Y., Orre L.M., Zhou Tran Y., Mermelekas G., Johansson H.J., Malyutina A., et al. DEqMS: a method for accurate variance estimation in differential protein expression analysis. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2020;19:1047–1057. doi: 10.1074/mcp.TIR119.001646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smyth G.K. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kong A.T., Leprevost F.V., Avtonomov D.M., Mellacheruvu D., Nesvizhskii A.I. MSFragger: ultrafast and comprehensive peptide identification in mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:513–520. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teo G.C., Polasky D.A., Yu F., Nesvizhskii A.I. Fast deisotoping algorithm and its implementation in the MSFragger search engine. J. Proteome Res. 2021;20:498–505. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.da Veiga Leprevost F., Haynes S.E., Avtonomov D.M., Chang H.Y., Shanmugam A.K., Mellacheruvu D., et al. Philosopher: a versatile toolkit for shotgun proteomics data analysis. Nat. Methods. 2020;17:869–870. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-0912-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Djomehri S.I., Gonzalez M.E., da Veiga Leprevost F., Tekula S.R., Chang H.Y., White M.J., et al. Quantitative proteomic landscape of metaplastic breast carcinoma pathological subtypes and their relationship to triple-negative tumors. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1723. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.UniProt C. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D523–D531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kall L., Canterbury J.D., Weston J., Noble W.S., MacCoss M.J. Semi-supervised learning for peptide identification from shotgun proteomics datasets. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:923–925. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tyanova S., Temu T., Sinitcyn P., Carlson A., Hein M.Y., Geiger T., et al. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:731–740. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyanova S., Cox J. Perseus: a bioinformatics platform for integrative analysis of proteomics data in cancer Research. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1711:133–148. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7493-1_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.R Development Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2010. R: A Language Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritchie M.E., Phipson B., Wu D., Hu Y., Law C.W., Shi W., et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B.L., Gillette M.A., et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiredja D.D., Koyuturk M., Chance M.R. The KSEA App: a web-based tool for kinase activity inference from quantitative phosphoproteomics. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:3489–3491. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Metz K.S., Deoudes E.M., Berginski M.E., Jimenez-Ruiz I., Aksoy B.A., Hammerbacher J., et al. Coral: clear and customizable visualization of human kinome data. Cell Syst. 2018;7:347–350.e341. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D., et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]