Highlights

-

•

Transcriptomic sequencing detected the highest expression of hsa_circ_0020134 (circ0020134) in liver metastases of colorectal cancer (CRC).

-

•

The transcription factor PAX5 potently enhances the expression of circ0020134 in CRC cells.

-

•

A CRC-specific circRNA-miRNA-mRNA network was established.

-

•

The circ0020134-miR-183-5p-PFN2 axis is shown to participate in the activation of the TGF-β/Smad pathway and promotes epithelial to mesenchymal transition.

-

•

The novel circ0020134-miR-183-5p-PFN2-TGF-β/Smad axis may be an anti-metastasis target for patients with CRC.

Keywords: CircRNAs, Colorectal cancer, miR-183-5p, Liver metastasis, Epithelial-mesenchymal transformation

Abstract

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are a distinct class of non-coding RNAs that play regulatory roles in the initiation and progression of tumors. With advancements in transcriptome sequencing technology, numerous circRNAs that play significant roles in tumor-related genes have been identified. In this study, we used transcriptome sequencing to analyze the expression levels of circRNAs in normal adjacent tissues, primary colorectal cancer (CRC) tissues, and CRC tissues with liver metastasis. We successfully identified the circRNA hsa_circ_0020134 (circ0020134), which exhibited significantly elevated expression specifically in CRC with liver metastasis. Importantly, high levels of circ0020134 were associated with a poor prognosis among patients. Functional experiments demonstrated that circ0020134 promotes the proliferation and metastasis of CRC cells both in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, upregulation of circ0020134 was induced by the transcription factor, PAX5, while miR-183-5p acted as a sponge for circ0020134, leading to partial upregulation of PFN2 mRNA and protein levels, thereby further activating the downstream TGF-β/Smad pathway. Additionally, downregulation of circ0020134 inhibited epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in CRC cells, which could be reversed by miR-183-5p inhibitor treatment. Collectively, our findings confirm that the circ0020134-miR-183-5p-PFN2-TGF-β/Smad axis induces EMT transformation within tumor cells, promoting CRC proliferation and metastasis, thus highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target for patients with CRC liver metastasis.

Introduction

According to the latest global cancer statistics, colorectal cancer (CRC) has an incidence and mortality rate of 10.0% and 9.4%, respectively, ranking it as the third most common malignant tumor in terms of incidence and second leading cause of death [1]. Despite significant advancements in the diagnosis and treatment of CRC through surgical interventions, palliative care, and adjuvant chemotherapy, changes in dietary habits and living standards have contributed to a rapid increase in the occurrence and fatality rates of this disease [2], [3], [4]. However, patients with liver metastases from CRC have low overall survival (OS) rates [5]. Liver metastasis is the most frequent form of distant spread observed among patients; approximately 15–25% present with liver metastases at initial diagnosis, while up to 20–25% develop synchronous liver metastases after primary CRC resection [6,7]. Furthermore, recurrence occurs in 40%–75% of patients following hepatectomy [8,9]. Moreover, traditional therapeutic drugs, such as bevacizumab and cetuximab, exhibit low specificity and sensitivity when used for the clinical treatment of patients with CRC with liver metastasis [10,11]. Therefore, identifying novel therapeutic targets and elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying CRC liver metastasis may significantly enhance treatment outcomes.

Circular RNA (circRNAs) are a novel class of non-coding RNA that differ from linear RNAs because of their circular structure, which confers them increased stability [12,13]. circRNAs exert diverse regulatory functions by acting as miRNA sponges, thereby modulating the expression of miRNAs and their target genes [14,15]. Additionally, circRNAs can function as RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that regulate gene expression through interactions with chelating agents and transcription regulators [16,17]. circRNAs are involved in the pathogenesis of various cancer types [18], [19], [20]. Recent comprehensive reviews by Dragomir and Zeng systematically summarized the roles and mechanisms of circRNAs in CRC, highlighting their potential diagnostic and prognostic value for patients with CRC [21,22]. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a pivotal mechanism in CRC metastasis. For instance, S100A8 promotes EMT and metastasis in CRC via the TGF-β/USF2 axis, while an IL-6R/STAT3/miR-34a feedback loop facilitates EMT-mediated invasion and metastasis in CRC [23,24]. However, the specific contribution of circRNAs to EMT in CRC remains unknown. Therefore, further investigations are urgently needed to elucidate the mechanistic role of circRNAs in promoting liver metastasis in CRC and to identify potential therapeutic targets.

Here, we identified hsa_circ_0020134 (circ0020134) as a highly specific marker of CRC liver metastasis and evaluated its prognostic value. Moreover, both in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that circ0020134 promoted the progression of CRC through a miR-183-5p-PFN2-dependent mechanism. Additionally, we discovered that the transcription factor, PAX5, induces upregulation of circ0020134 expression. Furthermore, circ0020134 overexpression led to the upregulation of Smad2 and Smad3 in CRC cells, subsequently inducing EMT. Collectively, these findings highlight the prognostic significance of circ0020134 in CRC and suggest that targeting the circ0020134-miR-183-5p-PFN2-TGF-β/Smad axis may hold promise as an anti-metastatic strategy for patients with CRC.

Materials and methods

Patients and human samples

Two cohorts of patients with CRC were enrolled in this study. Cohort I consisted of 172 untreated paired-adjacent normal tissues, primary CRC tissues, and corresponding colorectal liver metastases obtained during CRC resection at the Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou. Among the 172 patients, 130 had no liver metastasis, whereas 42 were diagnosed with colorectal liver metastasis. Cohort II included 42 pairs of normal adjacent tissues, primary CRC tissues, and colorectal liver metastases from patients in cohort I at Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University. All the tissue specimens collected between 2015 and 2018, and were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent use.

RNA isolation and RNAseq

RNA was extracted from frozen human tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. For RNAseq analysis, 15 samples were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq platform (Aksomics, Shanghai, China), generating an average of approximately 14.51 G bases per sample. Total RNA samples were subjected to oligo dT enrichment (rRNA removal) and prepared using the KAPA Strand RNA-Seq Library Prep Kit (Illumina, Shanghai, China). During library construction, double-stranded cDNA was synthesized using the dUTP method in combination with a high-fidelity PCR polymerase to ensure strand specificity of the resulting RNA sequencing library. The constructed libraries were assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and quantified using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). Pooled libraries consisting of different samples were sequenced using an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencer. Image processing and base identification were performed using the Solexa pipeline version 1.8 (Off-Line Base Caller software, version 1.8). circRNAs were aligned to the reference genome (GRCh37) using STAR software, and post-splice junction reads were detected using CIRCexplorer2. Read counts were calculated and differential expression was analyzed using edgeR in the R software package. Correlation analysis based on gene expression levels as well as additional data mining analyses, such as clustering of differentially expressed genes, were performed using the Python, R, and Shell programs.

CRC cell lines and cell culture

The intestinal epithelial cell line, NCM-460, was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ACTT, Manassas, VA, USA) and maintained at the Oncology Laboratory, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University. CRC cell lines: SW480, SW620, LOVO, HCT116, DLD1, and HT29 were also acquired from ATCC and cultured in the same laboratory. Cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All experiments were conducted during the logarithmic growth phase.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from CRC tissues and cell lines using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). HiScript II Q Select RT SuperMix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) was used for cDNA synthesis to analyze circRNAs and mRNA. For miRNA analysis, cDNA was synthesized using specialized stem-loop primers (Generay, Shanghai, China). Subsequently, PCR amplification was conducted using ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme) and analyzed on a LightCycler 96 System (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). GAPDH or U6 served as internal controls for circRNA, miRNA, and mRNA assays. Relative expression levels were determined using the 2−△Ct or 2−△△Ct method. All experiments were performed in triplicates. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

The Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) kits were procured from RiboBio (Guangzhou, China). Experiments were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. For tissue preparation, deparaffinized and rehydrated tissue sections were digested with Proteinase K. After a pre-hybridization period of 30 min, cell or tissue samples were subjected to overnight hybridization at 37 °C using specific probes (FISH kit; RiboBio). The Cy3 labeled circ0020134 probe (5′-TTATAACATTCATTACTGCAGCTCCTTTGAG-3′) was designed and synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). 18S and U6 probes were provided by GenePharma. Images were acquired using a Zeiss confocal fluorescence microscope (LSM710, Jena, Germany).

RNase R treatment

Total RNA (2 μg) was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, either with or without RNase R (5 U*μg−1, epicentre Technologies, Madison, WI, USA). Subsequently, RNA samples were purified using the RNeasy MinElute Cleaning Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) and subjected to qRT-PCR analysis.

Plasmids, small interfering (si)RNA, and cell transfection

Full-length cDNAs of circ0020134 and PAX5 were amplified and cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector, obtained from Generay (Shanghai, China). Circ0020134 was transiently silenced using siRNAs specifically designed and synthesized by GenePharma to target human Circ0020134 or PFN2. miR-183-5p mimics or inhibitors and control plasmids were purchased from GenePharma (Table S2). Transfection of the vectors was performed using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen). After 48 h of transfection, the transfection efficiency of each group was assessed using qRT-PCR.

Bioinformatics analysis

The circ0020134 sequence was obtained from CircBase (http://www.circbase.org/). Circ0020134 and potential miRNA-binding sites were identified using the CircInteractome database (https://circinteractome.nia.nih.gov/). TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/) and miRDB (http://www.mirdb.org/mirdb/index.html) were used to predict miRNA-mRNA binding sites. The Cytoscape software was used to construct comprehensive circRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks. Additionally, ORFfinder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/) and IRESite (http://www.iresite.org/) were used to assess the translational capacity of circ0020134.

CCK-8 and colony formation detection

Cell proliferation assays were performed using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) reagent (APExBIO, Houston, Texas, USA). Transfected cells were inoculated into 96-well plates at 1 × 103 cells per well and cultured for different periods (1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 days). Twenty μL CCK-8 solution was added to each well and the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. Optical density values at 450 nm were measured using a scanner (ELx800; BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA).

For colony formation experiments, 3 × 103 cells were seeded in six-well plates and incubated in a complete medium at 37 °C. After 2 weeks, the colonies were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.5% crystal violet. Colonies containing at least 50 cells were scored and viewed under an IX71 inverted phase-contrast fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of five random scoring fields.

Migration and invasion assay

Transwell chambers (8 μm, 24-well insert; Corning, Lowell, MA, USA) were used for migration assay. Briefly, 600 μL culture medium containing 10% FBS was added to the inferior chamber, and 1 × 104 cells were added to 200 μL serum-free culture medium to the upper chamber. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. A cotton swab was used to remove the unmigrated cells. Finally, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and transferred to a membrane stained with 0.5% crystal violet. Migrating cells were counted under an IX71 microscope (Olympus). For the invasion assay, the inserted membrane was coated with diluted Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA). The remaining steps were identical to those used in the migration assay.

Western blot

RIPA Lysis Buffer (CwBiotech, Jiangsu, China) was used to extract total protein, and a BCA protein Assay Kit (CwBiotech) was used to detect the protein concentration. The protein extracts were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). After 1 h of blocking, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Next day, the membrane was incubated with secondary antibodies, conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:5000; Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA), at room temperature for 1 h. Immunoreactive bands were detected using the ECL kit (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA). The following primary antibodies were used: anti-PFN2 (1:1000,PK07518; Abmart, Shanghai, China), anti-Smad2 (1:1000,5339 s; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Smad3 (1:1000,9523 s; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-TGF-β1 (1:1000,ab215715; Abcam, Shanghai, China), anti-E-cadherin (1:1000,3195 s; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-N-cadherin (1:1000,13116s; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Vimentin (1:1000,5741 s; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Snail (1:1000,3879 s; Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-Slug (1:1000,9585 s; Cell Signaling Technology). The band density was normalized to β-actin (1:1000,RM2001; ABclonal, Wuhan, China) or GAPDH (1:1000, 60004–1-Ig; Proteintech, Wuhan, China) and quantified by a Biolight BLT GelView 6000 Pro-machine.

RNA immunoprecipitation

The RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) procedure was performed using the Magna RIP RNA-binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Kit (Millipore), according to the manufacturer's instructions. CRC cells were lysed in RIPA buffer and immunoprecipitated using antibodies and protein A/G magnetic beads. Antibodies against AGO2 (1:50, 67934–1-IG; Proteintech) were used for immunoprecipitation. Magnets were used to hold the bead-bound complex while the unbound material was washed off. Finally, the immunoprecipitated RNA was extracted and analyzed using qRT-PCR.

RNA pull-down

RNA pull-down was performed using a Pierce™ Magnetic RNA-protein pull-down kit (Millipore). Biotin-labeled control oligomers (UGCUUUGCACGGUAACGCCUGUUUU-bio, known as Control probe) or an oligomer complementary to the sequence of circ0020134 (TTATAACATTCATTACTGCAGCTCCTTTGAG-bio, also known as circ00200134 probe) from GenePharma, Shanghai, China, were synthesized and utilized. The oligomers were incubated with the lysates from HCT116 and DLD1 cells for 2 h at 25 °C. The RNA/ protein or RNA/miRNA complex was then captured with streptavidin-coupled dynabeads at 25 °C for 1 h. The pull-down complex was analyzed using western blotting and qRT-PCR.

Luciferase

Wild-type predicted binding sites or mutant binding sites of circ0020134 and miR-183-5p were cloned into the luciferase reporter, pmirGLO dual-luciferase miRNA TARGET EXPRESSION vector (GenePharma). The plasmid was then co-transfected into HCT116 cells along with miR-183-5p mimics. PFN2–3′UTR with wild-type or mutant seed regions were also cloned into the pmirGLO dual-luciferase miRNA TARGET EXPRESSION vector (GenePharma) and co-transfected with miR-183-5p mimics to confirm direct binding between miR-183-5p and PFN2. To evaluate the transcriptional regulatory relationship between PAX5 and circ0020134, the circ0020134 promoter was embedded into the pGL3-Basic vector (GenePharma), followed by co-transfection with the PAX5 expression plasmid and pRL-Renilla into HCT116 cells. Luciferase activity was detected 48 h after transfection and firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

Animal studies

Five-week-old male BALB/c nude mice were purchased from GemPharmatech LLC (Nanjing, China) and divided into four groups (six mice per group): NC, circ0020134, short hairpin (sh)-PFN2, and circ0020134 + sh-PFN2. Aliquots of 100 μL of 5 × 106 SW620 cells infected with lentiviral NC, lentiviral-circ0020134, lentiviral-shPFN2 or lentiviral-circ0020134, and lentiviral-shPFN2 were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of nude mice. Tumor volume (TV) was measured weekly and calculated as follows: TV (mm3) = length × width2 × 0.5. Mice were sacrificed 4 weeks after inoculation, and the tumor tissues were excised and stored at −80 °C for further immunohistochemistry (IHC). To observe the metastasis in vivo, four groups were formed again and 100 μL of 5 × 106 SW620 cells were injected into the spleen of the mice. After 1.5 months, the mice were sacrificed and their livers were collected and photographed. The number of metastatic liver nodes per mouse was determined and calculated.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Immunohistochemical analyses were performed using primary antibodies against PFN2 (1:100, PK07518; Abmart) and Ki-67 (1:100,9027 s; Cell Signaling Technology). Tissue specimens were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and treated with boiling citrate buffer for 6 min for antigen extraction. Sections were enclosed in a blocking reagent (Millipore) for 10 min, incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C, washed with tris buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST), and then incubated with secondary antibodies (Millipore) for 45 min. An HRP/DAB kit (Millipore) was used for staining. IHC images were obtained under a microscope at 10x and 20x objectives. IHC staining was scored by the percentage of positive area and intensity as follows: 0, no staining; 1, <10% positive, moderate, or strong intensity; 2, 10–50% positive, moderate, or strong intensity; 3, >50% positive, moderate intensity; and 4, >50% positive, strong intensity.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA, USA). Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA were used to compare differences between groups, as appropriate. OS curves were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and analyzed using the log-rank test. Correlations between the groups were analyzed using Spearman's correlation. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Results

Transcriptomic sequencing identified a unique gene expression profile for liver metastases in CRC

To illustrate the expression profile of liver metastasis-associated circRNAs in CRC tissues, normal adjacent tissues, primary CRC tissues, and CRC liver metastases were compared in five patients, and transcriptomic sequencing was performed using Illumina HiSeq (Fig. 1A). Unsupervised clustering, volcano, and scatter maps of transcriptomic sequencing datasets demonstrated that CRC liver metastasis tissues had a different gene expression profile than that of primary CRC tissues or normal adjacent tissues (Fig. 1B–D).

Fig. 1.

Transcriptomic sequencing identified a unique gene expression profile for liver metastases in CRC. A. Adjacent normal tissues (ANT), primary tumors (PT), and liver metastasis (LM) were collected from five patients with colorectal cancer and subjected to transcriptomic sequencing. B. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of normalized counts from high-throughput sequencing of ANT, PT, and LM. C-D. Volcano and scatter plot were described for upregulated genes in LM compared to that in PT. E. Eight candidate genes were selected from top upregulated circRNAs in LM compared to that in ANT or PT. F. OS curves were plotted, showing that high circ0020134 levels were associated with poor 5-year OS compared with that in patients with low expression levels. G. Relative expression of circ0020134 in 42 pairs of ANT, PT, and LM tissues measured using qRT-PCR. All data were presented as the mean ± SD of experimental triplicates. ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Subsequently, the circRNA with the highest expression in CRC liver metastasis tissues was selected, followed by primary CRC tissues and the lowest expression in normal adjacent tissues. According to these criteria, eight candidate circRNAs were obtained from the intersection of CRC liver metastasis tissues, primary CRC tissues, and normal adjacent tissues (Fig. 1E). Circ0020134 was the most significant circRNA among the eight candidate circRNAs. The correlation between circ0020134 expression levels and the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with CRC is listed in Table S3. The expression levels of circ0020134 showed statistically significant differences according to the tumor size and TNM stage. An OS curve was constructed (Cohort I). The data showed that patients with CRC with high circ0020134 levels had worse OS at 5 years compared to that of patients with low circ0020134 levels (***P < 0.001, Fig. 1F). Finally, qRT-PCR was performed to detect circ0020134 expression in 42 pairs of normal adjacent tissues, primary CRC tissues, and CRC liver metastasis tissues (Cohort II). The results showed that the expression level of circ0020134 in CRC liver tissues was significantly higher than that in normal adjacent or primary CRC tissues (Fig. 1G). These results strongly suggested that circ0020134 is a metastasis-associated ncRNA that is strongly associated with the prognosis of patients with CRC.

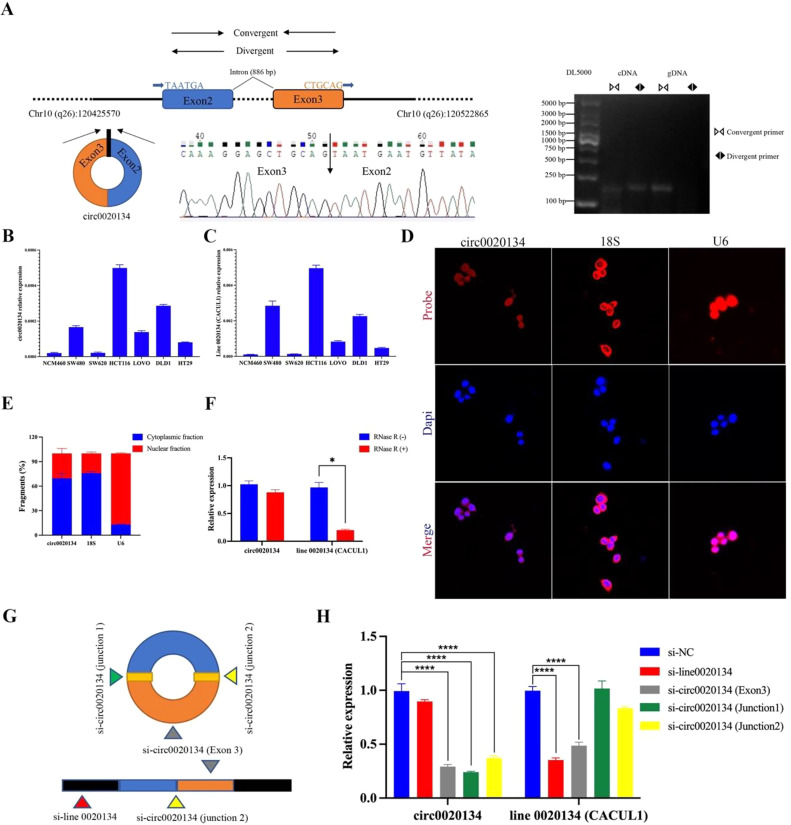

Characterization of circ0020134 in CRC cells

Circ0020134, also called hsa_circ_0020134 (https://circinteractome.nia.nih.gov/), is from CACUL1 genes (gene ID:143384, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/143384 chr10:120425570–120522865). Linear 0020134 (chr10:120488806–120489922) has a genome length of 1116 bp, and circ0020134 consists of head-to-tail splicing of exons 2 and 3 with a length of 230 bp. In this study, the back splice of circ0020134 was specifically amplified using divergent and convergent primers in HCT116 cells, and Sanger sequencing of the PCR products confirmed the presence of circ0020134 splicing junctions (Fig. 2A). The qRT-PCR results also showed that circ0020134 and linear 0020134 were commonly expressed in different CRC cell lines (Fig. 2B and C). Moreover, the results showed that linear 0020134 and circ0020134 were highly expressed in the HCT116 and DLD1 cells, respectively. Confocal microscopy of FISH assays showed that circ0020134 was mainly expressed in the cytoplasm of HCT116 cells, similar to that of the control group 18S (Fig. 2D and E). Next, the stability of circ0020134 was analyzed, and HCT116 cells were treated with RNase R. qRT-PCR revealed that circ0020134 was more resistant to digestion after treatment with RNase R exonuclease than was linear RNA, further indicating that circ0020134 has a stable loop structure (Fig. 2F). In addition, interference fragments of linear 0020134, exon 3, junction 1, and junction 2, which specifically target circ0020134, were synthesized and transfected into HCT116 cells. The results demonstrated that the linear 0020134 was attenuated by si-line 0020134 and circ0020134 (exon 3), whereas circ0020134 was significantly knocked down by targeting exon 3, junction 1, and junction 2 (Fig. 2G and H). These findings indicate that circ0020134 is derived from the host gene CACUL1 and has a stable head-to-tail splice loop structure.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of circ0020134 in CRC cells. A. The genomic locus of circ0020134. Left, the expression of circ0020134 was detected using qRT-PCR followed by Sanger sequencing. Right, qRT-PCR products with divergent primers showing the circularization of circ0020134. B-C. The relative common expressions between circ0020134 and linear 0020134 in different CRC cells were detected using qRT-PCR. d-E. The locations of circ0020134, 18S, and U6 in HCT116 cells were observed by the FISH assay. F. HCT116 cells were treated with RNase R and circ0020134 stability was analyzed. G-H. Interference fragments which specifically targeted the linear 0020134 and junction of circ0020134 were synthesized and transfected into HCT116 cells. Expressions of circ0020134 and linear 0020134 were determined using qRT-PCR. All data were presented as the mean ± SD of experimental triplicates. *, P < 0.05; ****, P < 0.0001.

Circ0020134 promotes CRC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion

The following assays were performed to further explore the biological functions of circ0020134 in CRC cells. Circ0020134 was effectively silenced by siRNA in HCT116 and DLD1 cells, and si1-circ0020134 with the best knockdown efficiency was selected for subsequent experiments (Fig. S1A). CCK-8 and colony formation assays were performed; si-circ0020134 significantly affected the proliferative ability of HCT116 and DLD1 cells compared to that of the control group (Fig. 3A–D). The effect of si-circ0020134 on tumor metastasis was evaluated using cell migration and invasion assays. As shown in Fig. 3E–H, silencing circ0020134 significantly inhibited the migration and invasion of CRC cells. Meanwhile, circ0020134 and a mock expression vector were constructed, and the PCR results suggested that the overexpressed vector of circ0020134 was adequate for subsequent studies (Fig. S1B). Similarly, overexpression of circ0020134 significantly increased the proliferation of CRC cells (Fig. 3I–L). Moreover, circ0020134 overexpression significantly improved the migration and invasion of HT29 and SW620 cells (Fig. 3M–P). These results suggested that circ0020134 may play a metastasis-promoting role in CRC.

Fig. 3.

Circ0020134 promotes CRC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. A-B. Proliferative ability was determined using the CCK-8 assay. C-D. Colony formation assay was performed and calculated. E-H. Cell migration and invasion was determined. I-J. Proliferative ability was determined using the CCK-8 assay. K-L. Colony formation assay was performed and calculated. M-P. Cell migration and invasion was determined. All data were presented as the mean ± SD of experimental triplicates. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

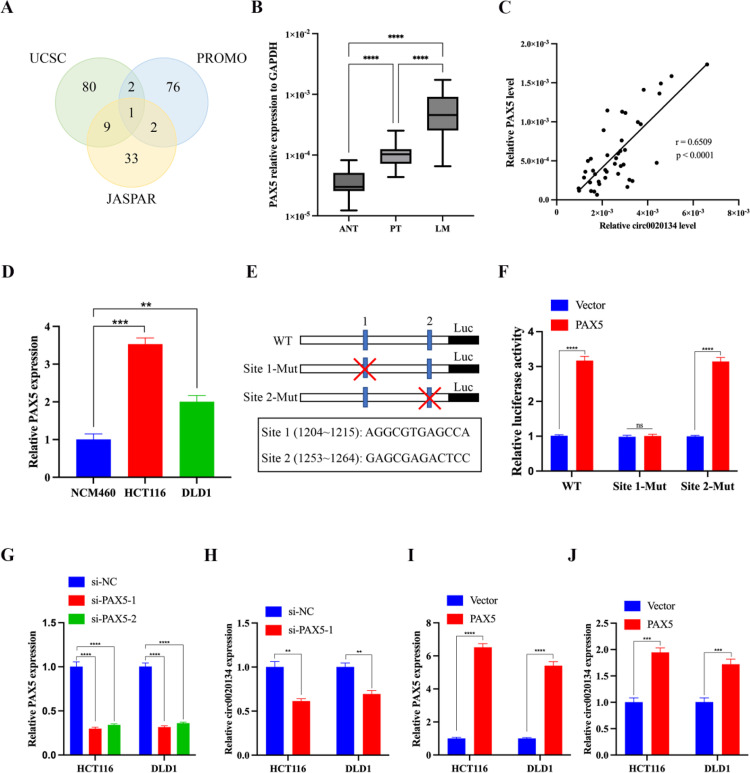

The expression of circ0020134 in CRC can be regulated by PAX5

Given the significant upregulation of circ0020134 in CRC, we hypothesized that circ0020134 is regulated by upstream transcription factors (TF) during CRC development in humans. We retrieved the promoter sequence of CACUL1 from the UCUS Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) and applied three algorithms (UCSC, PROMO, and JASPAR) to predict the potential TFs that might interact with this promoter sequence. PAX5 was the only TF for which these algorithms overlapped (Fig. 4A). We then examined the expression level of PAX5 in 42 pairs of normal adjacent tissues, primary CRC tissues, and CRC liver metastasis tissues. We found that PAX5 was highly expressed in CRC liver metastasis tissues compared to that in normal adjacent tissues or primary CRC tissues and was positively correlated with the expression level of circ0020134 (Fig. 4B and C). At the cellular level, PAX5 was upregulated in HCT116 and DLD1 cells compared to that in NCM460 cells (Fig. 4D). Subsequently, we compared the promoter sequence of circ0020134 with the PAX5-binding motif in JASPAR, which predicted two possible PAX5-binding sites in the circ0020134 promoter (Fig. 4E), and verified the two possible binding sites using dual-luciferase reporter assays. As expected, forced expression of PAX5 significantly increased the activity of the circ0020134 promoter, but this effect disappeared after mutation at site 1 rather than at site 2 (Fig. 4F), suggesting that PAX5 regulation of circ0020134 requires site 1. Next, we investigated the effect of PAX5 on the expression change of circ0020134. We designed two siRNAs for PAX5, and because of its relatively good knockdown effect, si-PAX5–1 was selected for follow-up experiments (Fig. 4G). After PAX5 knockdown, the expression level of circ0020134 in HCT116 and DLD1 cells decreased significantly (Fig. 4H), and the results of PAX5 overexpression were similar (Fig. 4I and J). These results suggest that the transcriptional regulation of PAX5 may act on circ0020134. In conclusion, PAX5 may activate circ0020134 transcription in patients with CRC.

Fig. 4.

The expression of circ0020134 in CRC can be regulated by PAX5. A. The Wayne plot shows the overlap between circ0020134 transcription factors predicted by three different algorithms. B. Relative expression of PAX5 in 42 pairs of ANT, PT, and LM tissues measured using qRT-PCR. C. The correlation between circ0020134 and PAX5 in CRC tissues was analyzed by Spearman correlation coefficients. D. The relative expression of PAX5 was detected in chosen CRC cell lines (HCT116, DLD1) and NCM460. E. The schematic plot of pGL3-Basic vector containing wild-type and mutated two motifs of circ0020134 promoter. F. Luciferase reporter assay in HCT116 cells co-transfected with the indicated two mutant pGL3-Basic vectors and control or PAX5 expression plasmid. G. Two PAX5-targeted siRNAs were transfected into HCT116 and DLD1 cells, and relative mRNA of PAX5 were estimated using qRT-PCR. H. The relative circ0020134 expression were detected in HCT116 and DLD1 cells after PAX5 silencing using qRT-PCR. I-J. The relative PAX5 and circ0020134 expression were detected in HCT116 and DLD1 cells after PAX5 overexpression using qRT-PCR. All data are presented as the mean ± SD of experimental triplicates. ns, P > 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

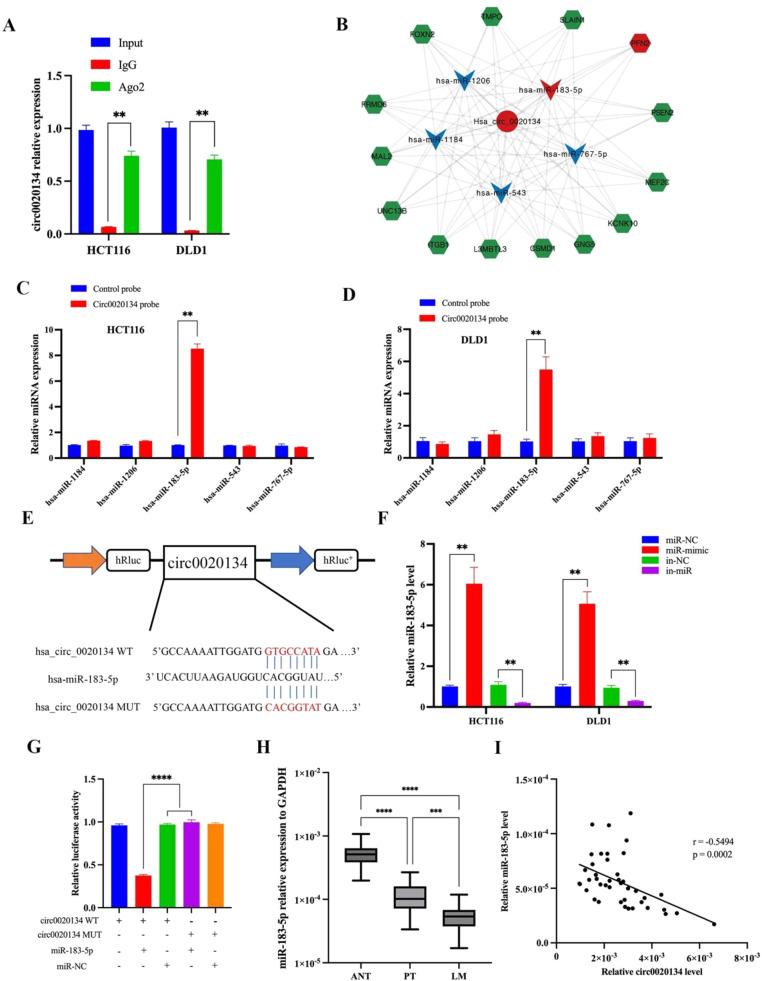

Circ0020134 functions as a sponge for miR-183-5p

To further study the potential mechanism of circ0020134 and search for its potential downstream molecules, bioinformatic methods were applied. As circ0020134 may encode small peptides, ORFfinder and IRESite were used to test its function. However, circ0020134 does not encode a small peptide (Fig. S2A). According to the FISH assay results, circ0020134 mainly exists in the cytoplasm. Therefore, circ0020134 was hypothesized to play a competing endogenous RNA in CRC. First, RIP assay was performed on HCT116 and DLD1 cells. The results showed that circ0020134 was enriched in AGO2 immunoprecipitation, confirming that circ0020134 absorbed the miRNAs (Fig. 5A). Bioinformatics analysis was performed using Cytoscape software to predict circRNA-miRNA-mRNA interactions based on circ0020134 (Fig. 5B). From the predicted results, five candidate miRNAs were selected, and their specific interactions were verified using a RNA pull-down assay. The results showed significant differences in the pull-down levels of miR-183-5p in HCT116 and DLD1 cells between circ0020134 and oligomeric probes (Fig. 5C and D). To further confirm the interaction between circ0020134 and miR-183-5p, a double-luciferase reporter assay was performed using HCT116 cells. The circ0020134-WT (wild-type) or circ0020134-mut plasmid was constructed based on the luciferase reporter vector (Fig. 5E), and then co-transfected with the miR-183-5p mimic or NC into HCT116 cells (Figs. 5F and S2B). The results of the double luciferase reporter assay showed that miR-183-5p mimics significantly reduced luciferase activity in the circ0020134-WT group, but had no effect on the mutant group (Fig. 5G). The expression levels of miR-183-5p in 42 pairs of normal adjacent tissues, primary CRC tissues, and CRC liver metastasis tissues were detected using qRT-PCR (Cohort II). The results showed that the expression level of miR-183-5p in CRC liver metastasis tissues was significantly lower than that in normal adjacent or primary CRC tissues (Fig. 5H). Spearman correlation coefficient analysis revealed that miR-183-5p was negatively correlated with the expression of circ0020134 in CRC liver metastasis tissues (r = −0.5494, P = 0.0002) (Fig. 5I). Collectively, these results suggested that circ0020134 acts as a sponge for miR-183-5p in CRC.

Fig. 5.

Circ0020134 functions as a sponge for miR-183-5p. A. RIP analysis of circ0020134 using anti-AGO2 antibodies in HCT116 and DLD1 cells. B. The circRNA-miRNA-mRNA interaction based on circ0020134 was demonstrated using prediction and bioinformatics analysis using Cytoscape software. C-D. The five miRNAs that may be regulated by circ0020134 based on the miRNA prediction and bioinformatics analyses are shown and were measured using qRT-PCR after the pull-down assay in HCT116 and DLD1 cells. E. Schematic illustration demonstrating the luciferase reporter vectors containing wild-type (WT) or mutant (MUT) predicted miR-183-5p binding sites of circ0020134. F. Relative expression of miR-183-5p after transfection with the mimics or inhibitor was measured using qRT-PCR. G. The luciferase assay was performed in HCT116 cells after co-transfection with miR-183-5p mimic and the luciferase vector containing wild-type (WT) or mutant (MUT) circ0020134. H. Relative expression of miR-183-5p in 42 pairs of ANT, PT, and LM tissues measured using qRT-PCR. I. The correlation between circ0020134 and miR-183-5p in CRC tissues was analyzed using Spearman correlation coefficients. All data were presented as the mean ± SD of experimental triplicates. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

PFN2 is directly targeted by miR-183-5p and indirectly regulated by Circ0020134

According to our previous predictions, PFN2, KCNK10, GNG5, SLAIN1, FRMD6, ITGB1, PSEN2, and MAL2 were the most likely target genes of miR-183-5p. Therefore, the mRNA expression levels of these genes were detected after the transfection of HCT116 cells with miR-183-5p mimics or inhibitors. The results showed that transfection with miR-183-5p mimics significantly downregulated the expression levels of PFN2 and GNG5, whereas the expression levels of PFN2 were upregulated after transfection with miR-183-5p inhibitors (Fig. 6A and B). Double-luciferase reporter assays were performed to confirm the binding between PFN2 and miR-183-5p (Fig. 6C). In HCT116 cells, PFN2 3′UTR WT or mutant plasmid was co-transfected with miR-183-5p mimics. The results showed that co-transfection of PFN2 3′UTR WT plasmid and miR-183-5p mimics significantly reduced the relative activity of luciferase (Fig. 6D). We also investigated the effect of miR-183-5p on PFN2 expression. The qRT-PCR results demonstrated that miR-183-5p mimics significantly reduced the expression of PFN2, whereas miR-183-5p inhibitors significantly upregulated the expression of PFN2 in both HCT116 and DLD1 cell lines (Fig. 6E). In contrast, PFN2 protein levels were significantly downregulated by miR-183-5p mimics (Fig. 6F). PFN2 expression was examined in 42 pairs of normal adjacent tissues, primary CRC tissues, and CRC liver metastasis tissues (Cohort II). The results revealed significantly higher expression levels of PFN2 in CRC liver metastasis tissues compared to that in normal adjacent tissues or primary CRC tissues, which was negatively correlated with the expression of miR-183-5p in CRC liver metastasis tissues (r = −0.4694, P = 0.0018) (Fig. 6G and H). To explore whether circ0020134 could also regulate the expression of PFN2, the expression of PFN2 was evaluated after transfection with circ0020134 siRNA. circ0020134 knockdown significantly reduced PFN2 expression (Fig. 6I and J). Based on PFN2 in 42 CRC liver metastasis tissues, a positive correlation between PFN2 and circ0020134 expression was observed in CRC liver metastasis tissues (r = 0.7078, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 6K). Taken together, these results suggest that PFN2 is a target gene of miR-183-5p and that it can be regulated by circ0020134.

Fig. 6.

PFN2 is directly targeted by miR-183-5p and indirectly regulated by Circ0020134. A. The relative mRNA expression of PFN2, KCNK10, GNG5, SLAIN1, FRMD6, ITGB1, PSEN2, and MAL2 after transfection with the miR-183-5p inhibitor was detected in HCT116 cells using qRT-PCR. B. The relative mRNA expression of PFN2, KCNK10, GNG5, SLAIN1, FRMD6, ITGB1, PSEN2, and MAL2 after transfection with the miR-183-5p mimics was detected in HCT116 cells using qRT-PCR. C. Schematic illustration of PFN2 3′UTR wild-type (WT) or 3′UTR mutant (MUT) luciferase reporter vectors and the predicted binding sites to miR-183-5p. D. The relative luciferase activities were detected in HCT116 cells after co-transfection with the PFN2 3′UTR wild-type (WT) or 3′UTR mutant (MUT) luciferase reporter vectors with the miR-183-5p mimics. E. Relative PFN2 mRNA expression after transfection with the miR-183-5p mimics or inhibitor was detected in cells using qRT-PCR. F. The relative PFN2 protein level after transfection with the miR-183-5p mimics was detected in cells using western blot. G. Relative expression of PFN2 in 42 pairs of ANT, PT, and LM tissues measured using qRT-PCR. H. The correlation between miR-183-5p and PFN2 in CRC tissues was analyzed using Spearman correlation coefficients. I. The relative PFN2 mRNA expression after transfection with circ0020134 siRNA was detected using qRT-PCR. J. The relative PFN2 protein level after transfection with circ0020134 siRNA was detected in cells using western blot. K. The correlation between circ0020134 and PFN2 level expression in CRC tissues was analyzed based on Spearman correlation coefficients. All data are presented as the mean ± SD of experimental triplicates. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

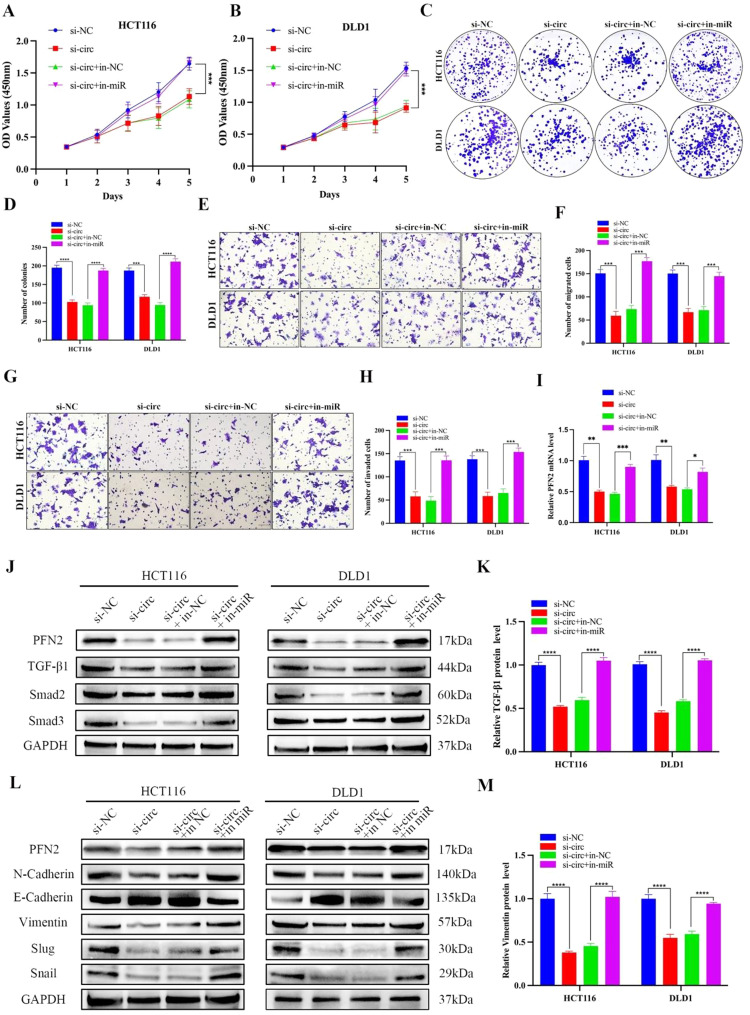

Circ0020134 promotes CRC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion through the Circ0020134/miR-183-5p/PFN2 axis

To investigate whether circ0020134 plays a role in promoting tumor progression via the /miR-183-5p/PFN2 axis, rescue experiments were performed on circ0020134 knockdown cells using miR-183-5p inhibitor transcription. CCK-8, colony formation, and Transwell assay results revealed that miR-183-5p inhibitors could salvage the inhibition of proliferation, migration, and invasion by circ0020134 downregulation in HCT116 and DLD1 cells (Fig. 7A–H). Next, PFN2 mRNA expression was detected using qRT-PCR, revealing that the circ0020134 siRNA-induced reduction in PFN2 expression was alleviated by miR-183-5p inhibitors (Fig. 7I). In addition, the western blot assay indicated that circ0020134 knockdown reduced PFN2 protein levels as well as TGF-β1 and Smad2/3 levels, which were reversed by miR-183-5p inhibitors (Fig. 7J–K and Fig. S3A-C). The TGF-β/Smad pathway plays a crucial role in EMT [41,42]. Markers involved in EMT were investigated by western blotting (Figs. 7L–M and S3D–H). Collectively, these results suggest that circ0020134 regulates miR-183-5p to further influence the expression of PFN2 and play a regulatory role in CRC.

Fig. 7.

Circ0020134 promotes CRC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion through the Circ0020134/miR-183-5p/PFN2 axis. A-D. HCT116 and DLD1 cell proliferation after transfection with circ0020134 siRNA and/or miR-183-5p inhibitor was measured using CCK-8 and colony formation assays. E-H. The cell migration (E) and invasion (G) capabilities were determined using Transwell assay after transfection of HCT116 and DLD1 cells with the circ0020134 siRNA and/or miR-183-5p inhibitor. I. The relative mRNA expression of PFN2 after transfection with circ0020134 siRNA and/or miR-183-5p inhibitor was detected using qRT-PCR. J-M. The relative protein expression of PFN2, EMT, and the level of downstream pathway proteins were measured using western blot in cells transfected with the circ0020134 siRNA and/or miR-183-5p inhibitor. All data are presented as the mean ± SD of experimental triplicates. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Circ0020134 promotes liver metastasis of colorectal cancer in vivo

Finally, tumor cells were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of BALB/ C-nude mice to determine whether circ0020134 promotes tumor development in vivo. Consistent with the in vitro results, both circ0020134 and PFN2 promoted tumor growth, and a rescue effect of shPFN2 was observed in circ0020134-overexpressed mice (Fig. 8A–C). Subsequently, the expression levels of Ki-67 and PFN2 in the four groups of tumor tissues were detected by immunohistochemical staining. The results showed that shPFN2 restored the expression levels of Ki-67 and PFN2 in circ0020134-overexpressed tumor tissues (Fig. 8D–E). Different groups of cells were injected into the spleens of the mice to better observe metastasis. Liver metastasis was observed 1.5 months later. The data showed that circ0020134 significantly promoted liver metastasis of CRC cells, whereas shPFN2 impaired the metastasis of tumor cells. More importantly, shPFN2 effectively antagonized the formation of liver metastases induced by circ0020134 overexpression (Fig. 8F–G). In summary, circ0020134 may specifically promote liver metastasis of CRC through a PFN2-dependent mechanism in vivo (Fig. 8H).

Fig. 8.

Circ0020134 promotes liver metastasis of CRC in vivo. A-C. Cells were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of BALB/c-nude mice and TV was measured weekly. After 4 weeks, the mice were sacrificed and the tumor tissues were excised and weighed. D. Histological analysis of tumor tissues using hematoxylin and eosin staining for Ki-67 and PFN2 in subcutaneous tumors. E. The graph shows the relative signal intensity scores of Ki-67 and PFN2. F-G. Cells were injected into the mouse spleens. After 1.5 months, the livers were excised and photographed, and the liver metastatic nodes were calculated. H. Schematic illustration of circ0020134 regulating the miR-183-5p-PFN2-TGF-β/Smad axis in CRC. All data are presented as the mean ± SD of experimental triplicates. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Discussion

In the present study, we have confirmed that circ0020134 is a circular RNA (circRNA) associated with CRC metastasis. Overexpression of circ0020134 was closely correlated with invasive characteristics and poor prognosis. Mechanistic investigations revealed that circ0020134 functions by adsorbing miR-183-5p to upregulate the expression of its target gene, PFN2, thereby inducing EMT and facilitating CRC metastasis and dissemination. Consequently, our findings contribute significantly to the understanding of the role of circRNAs in cancer progression and highlight the pivotal role of endogenous circ0020134 in CRC metastasis.

CircRNAs are a novel class of non-coding RNAs that form closed continuous loops through covalently linked 3′ and 5′ ends [12,25]. In the 1970s, Sanger et al. discovered many single-stranded circular RNAs in plant viruses [26]. However, circRNAs are believed to result from mis-splicing during exon transcription [27]. Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of circRNAs in both diagnostic and treatment strategies for CRC [28]. In this study, we investigated the expression levels of circRNAs in adjacent normal tissues, primary CRC tissues, and CRC liver metastasis tissues. Compared with that in primary CRC or normal adjacent tissues, circ0020134 exhibited the highest upregulation in CRC liver metastasis tissues. Further survival analysis revealed that patients with CRC with elevated circ0020134 levels had poor OS rates at 5 years. Functional experiments confirmed that circ0020134 significantly influences the proliferation and metastasis of CRC cells. These findings suggest a potential role for circ0020134 in promoting metastasis within CRC.

In the current study, three mechanisms through which circRNAs exert their biological functions were identified. First, nuclear-retained circular RNAs can regulate gene expression at the transcriptional and splicing levels [29,30]. Secondly, circRNAs can undergo translation and function as coding proteins [31,32]. The third mechanism, which is widely established, involves circular RNAs acting as sponges for miRNAs by binding to their binding sites, thereby regulating miRNA activity against other target genes [14,33]. In this study, we excluded the possible biological function mechanisms of the first two circRNAs, based on FISH experiments and the results obtained from the ORFfinder and IRESite prediction tools. Subsequently, RIP experiments confirmed that circ0020134 could adsorb miRNA; therefore, we further explored the ceRNA mechanism in depth. Cytoscape software was used to predict circRNA-miRNA-mRNA interactions and establish a related network that revealed a potential target miRNA, miR-183-5p. This finding was consistent with those of the RNA pull-down and dual-luciferase reporter assays, confirming their binding interactions. Additionally, there was negative correlation between miR-183-5p expression level and that of circ0020134. miR-183-5p plays a tumor suppressor role in various cancers; for instance, it inhibits PIK3CA and PTEN in lung cancer, while targeting ABAT to regulate liver cancer cell function [34], [35], [36]. Collectively, these findings suggest that circ0020134 acts as an oncogene in CRC through the sponge-like sequestration of miR-183-5p.

As non-coding RNAs, miRNAs primarily exert their biological functions by modulating the stability of their target genes. Through our previous prediction analysis, we identified several potential target genes and subsequently validated the specific binding of miR-183-5p to the 3′UTR region of PFN2 using a dual luciferase reporter assay. Importantly, our findings revealed elevated levels of PFN2 mRNA and protein in CRC liver metastasis tissues compared to those in normal adjacent tissues or primary CRC tissues. Furthermore, these expression levels exhibited a significant positive correlation with circ0020134 expression but displayed an inverse relationship with miR-183-5p levels. Based on these results, we hypothesized that the circ0020134-miR-183-5p-PFN2 axis promotes liver metastasis in CRC.

Profilins (PFNs) are a family of actin-binding proteins found in eukaryotes that regulate the dynamics of actin polymerization and reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton [37]. Recent studies have demonstrated upregulation of PFN2 expression in colorectal and lung cancer tissues, which is consistent with our experimental findings [38,39]. Furthermore, PFN2 can epigenetically upregulate the expression of Smad2 and Smad3 in non-small cell lung cancer by inhibiting HDAC1 recruitment to their promoters, thereby promoting tumor proliferation and metastasis [40]. The TGF-β/Smad pathway is known to play a crucial role in EMT. For instance, TGF-β regulates fibrosis and induces EMT through the RAS effector, RREB1, while LncRNA LIATS1 inhibits TGF-β-induced EMT and cancer cell plasticity by enhancing the degradation of TβRI [41,42]. Surprisingly, our experimental results consistently demonstrated that knockdown of circ0020134 suppressed the expression levels of PFN2, TGF-β1, Smad2/3, as well as EMT markers. In rescue experiments supplemented with miR-183-5p inhibitor, knockdown of circ0020134 in CRC cells resulted in downregulation of PFN2, TGF-β1, and Smad2/3 along with EMT markers; these effects were completely reversed. Therefore, we propose that the circ0020134-miR-183-5p-PFN2 axis contributes to activation of the TGF-β/Smad pathway leading to induction of EMT transformation in tumor cells and promotion of CRC proliferation and metastasis.

The abnormally high expression of circRNAs in tumors is epigenetically regulated. For example, the transcription factor, ZEB1, upregulates hsa_circ_0001178 production and enhances the invasion and metastasis of CRC. YY1-regulated circFIRRE drives osteosarcoma progression and metastasis through oncogenesis-angiogenesis coupling [43,44]. In this study, we identified PAX5 as a transcription factor that promotes circ0020134 transcription. Specifically, the PAX5-miR-142 feedback loop stimulates breast cancer proliferation by regulating DNMT1 and ZEB1, while PAX5 activation of DGCR5 activates Wnt/β-catenin pathway by targeting miR-3163/TOP2A to promote pancreatic cancer [45,46]. Subsequent experiments demonstrated that PAX5 directly binds to sites 1204 ∼ 1215 in the circ0020134 promoter, thereby increasing its expression. Similarly, we observed a strong positive correlation between circ0020134 expression and PAX5 levels in CRC tissues, and knockdown of PAX5 downregulated circ0020134 expression. Reportedly, specific modifications in the genome such as methylation and acetylation can influence DNA binding specificity of transcription factors [47,48]. However, the precise mechanism underlying PAX5 binding to circ0020134 requires further investigation. Collectively, these findings confirm that the transcription factor, PAX5, promotes circ0020134 expression which regulates EMT of CRC cells through the circ0020134-miR-183-5p-PFN2-TGF-β /Smad axis and facilitates liver metastasis in CRC.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate a significant upregulation of circ0020134 in CRC liver metastases, which is closely associated with the prognosis of patients with CRC. Through comprehensive in vivo and in vitro experiments, we confirmed that the transcription factor, PAX5, induces the overexpression of circ0020134. Furthermore, we have elucidated that the circ0020134-miR-183-5p-PFN2 axis plays a crucial role in activating the TGF-β/Smad pathway to promote EMT, thereby uncovering a novel mechanism underlying CRC progression. Importantly, targeting the circ0020134-miR-183-5p-PFN2-TGF-β/Smad axis holds great promise as an effective therapeutic strategy for combating CRC liver metastasis.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital. All patients provided informed consent for the collection of tissue specimens. The animal studies were approved by the Laboratory Animal Center of Sun Yat-Sen University and the Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University.

Registry and the Registration No. of the study/trial: N/A.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jin-hao Yu: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Jia-nan Tan: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Guang-yu Zhong: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Lin Zhong: Formal analysis. Dong Hou: Formal analysis. Shuai Ma: Investigation. Peng-liang Wang: Investigation. Zhi-hong Zhang: Software. Xu-qiang Lu: Software. Bin Yang: Conceptualization, Visualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Sheng-ning Zhou: Conceptualization, Visualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Fang-hai Han: Conceptualization, Visualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 82003253), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (grant number 2021A1515111113), Guangzhou Science and Technology Plan Project (grant number 202206080007).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101823.

Contributor Information

Bin Yang, Email: yangb23@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Sheng-ning Zhou, Email: zhoushn3@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Fang-hai Han, Email: hanfh@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West N.R., McCuaig S., Franchini F., Powrie F. Emerging cytokine networks in colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015;15:615–629. doi: 10.1038/nri3896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein D.A., Zeichner S.B., Bartnik C.M., Neustadter E., Flowers C.R. Metastatic colorectal Cancer: a systematic review of the value of current therapies. Clin. Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dienstmann R., Vermeulen L., Guinney J., Kopetz S., Tejpar S., Tabernero J. Consensus molecular subtypes and the evolution of precision medicine in colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2017;17:79–92. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tejpar S., Shen L., Wang X., Schilsky R.L. Integrating biomarkers in colorectal cancer trials in the west and China. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015;12:553–560. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopetz S., Chang G.J., Overman M.J., Eng C., Sargent D.J., Larson D.W., Grothey A., Vauthey J.N., Nagorney D.M., McWilliams R.R. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:3677–3683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cen B., et al. Prostaglandin E2 induces miR675-5p to promote colorectal tumor metastasis via modulation of p53 expression. Gastroenterology. 2019;158:971–984. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vigano L., Capussotti L., Lapointe R., Barroso E., Hubert C., Giuliante F., Ijzermans J.N., Mirza D.F., Elias D. Early recurrence after liver resection for colorectal metastases: risk factors, prognosis, and treatment. A LiverMetSurvey-based study of 6,025 patients. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014;21:1276–1286. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhogal R.H., Hodson J., Bramhall S.R., Isaac J., Marudanayagam R., Mirza D.F., Muiesan P., Sutcliffe R.P. Predictors of early recurrence after resection of colorectal liver metastases. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2015;13:135. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0549-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuboki Y., Nishina T., Shinozaki E., Yamazaki K., Shitara K., et al. TAS-102 plus bevacizumab for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard therapies (C-TASK FORCE): an investigator-initiated, open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 1/2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1172–1181. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yaeger R., Weiss J., Pelster M.S., Spira A.I., Barve M., Ou S.I., Leal T.A., Bekaii-Saab T.S., Paweletz C.P., Heavey G.A., et al. Adagrasib with or without Cetuximab in colorectal cancer with mutated KRAS G12C. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023;388(1):44–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2212419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Memczak S., Jens M., Elefsinioti A., et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature. 2013;495:333–338. doi: 10.1038/nature11928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salzman J., Gawad C., Wang P., Lacayo N., Brown P. Circular RNAs are the predominant transcript isoform from hundreds of human genes in diverse cell types. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen T.B., Jensen T.I., Clausen B.H., Bramsen J.B., Finsen B., Damgaard C.K., et al. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 2013;495(7441):384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng Q., Bao C., Guo W., Li S., Chen J., Chen B., et al. Circular RNA profiling reveals an abundant circHIPK3 that regulates cell growth by sponging multiple miRNAs. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11215. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du W.W., Yang W., Liu E., Yang Z., Dhaliwal P., Yang B.B. Foxo3 circular RNA retards cell cycle progression via forming ternary complexes with p21 and CDK2. Nucl. Acid. Res. 2016;44:2846–2858. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holdt L.M., Stahringer A., Sass K., Pichler G., Kulak N.A., Wilfert W., Kohlmaier A., Herbst A., Northoff B.H., Nicolaou A., et al. Circular non-coding RNA ANRIL modulates ribosomal RNA maturation and atherosclerosis in humans. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12429. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X.N., Wang Z.J., Ye C.X., Zhao B.C., Li Z.L., Yang Y. RNA sequencing reveals the expression profiles of circRNA and indicates that circDDX17 acts as a tumor suppressor in colorectal cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;37:325. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-1006-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X., Mao R., Su W., Yang X., Geng Q., Guo C., et al. Circular RNA circHIPK3 modulates autophagy via MIR124-3p-STAT3-PRKAA/AMPKa signaling in STK11 mutant lung cancer. Autophagy. 2020;16(4):659–671. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2019.1634945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jie M., Wu Y., Gao M., Li X., Liu C., Ouyang C., et al. CircMRPS35 suppresses gastric cancer progression via recruiting KAT7 to govern histone modification. Mol. Cancer. 2020;19:56. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01160-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng K., Wang S. Circular RNAs: the crucial regulatory molecules in colorectal cancer. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2020;216 doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2020.152861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dragomir M.P., Kopetz S., Ajani J.A., Calin G.A. Non-coding RNAs in GI cancers: from cancer hallmarks to clinical utility. Gut. 2020;69:748–763. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li S., Zhang J., Qian S., Wu X., Sun L., Ling T., Jin Y., Li W., Sun L., Lai M., Xu F. S100A8 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis under TGF-β/USF2 axis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2021;41(2):154–170. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rokavec M., Öner M.G., Li H., Jackstadt R., Jiang L., Lodygin D., Kaller M., et al. IL-6R/STAT3/miR-34a feedback loop promotes EMT-mediated colorectal cancer invasion and metastasis. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124(4):1853–1867. doi: 10.1172/JCI73531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geng Y., Jiang J., Wu C. Function and clinical significance of circRNAs in solid tumors. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018;11:98. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0643-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanger H.L., Klotz G., Riesner D., Gross H.J., Kleinschmidt A.K., et al. Viroids are single-stranded covalently closed circular RNA molecules existing as highly base-paired rod-like structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73(11):3852–3856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cocquerelle C., Mascrez B., Hetuin D., Bailleul B. Mis-splicing yields circular RNA molecules. FASEB J. 1993;7(1):155–160. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.1.7678559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H., Li X., Meng Q., Sun H., Wu S., Hu W., Liu G., Li X., Yang Y., Chen R. CircPTK2 (hsa_circ_0005273) as a novel therapeutic target for metastatic colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2020;19(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-1139-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han D., Li J., Wang H., Su X., Hou J., Gu Y., et al. Circular RNA circMTO1 acts as the sponge of microRNA-9 to suppress hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Hepatology. 2017;66:1151–1164. doi: 10.1002/hep.29270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X., Chen R.X., Wei W.S., Li Y.H., Feng Z.H., Tan L., et al. PRMT5 circular RNA promotes metastasis of Urothelial carcinoma of the bladder through sponging miR-30c to induce epithelial–Mesenchymal transition. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;24(24):6319–6330. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Z., Huang C., Bao C., Chen L., Lin M., Wang X., Zhong G., Yu B., Hu W., Dai L., et al. Exon-intron circular RNAs regulate transcription in the nucleus. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:256–264. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conn V.M., et al. A circRNA from SEPALLATA3 regulates splicing of its cognate mRNA through R-loop formation. Nat. Plants. 2017;3:17053. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Y., Xie Z., Chen J., Chen J., Ni W., Ma Y., et al. Circular RNA circTADA2A promotes osteosarcoma progression and metastasis by sponging miR-203a-3p and regulating CREB3 expression. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:73. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1007-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meng F., Zhang L. miR-183-5p functions as a tumor suppressor in lung cancer through PIK3CA inhibition. Exp. Cell. Res. 2019;374(2):315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han H., Zhou S., Chen G., Lu Y., Lin H. ABAT targeted by miR-183-5p regulates cell functions in liver cancer. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2021;141 doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2021.106116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang H., Ma Z., Liu X., Zhang C., Hu Y., Ding L., Qi P., Wang J., Lu S., Li Y. MiR-183-5p is required for non-small cell lung cancer progression by repressing PTEN. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019;111:1103–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y., Grenklo S., Higgins T., et al. The proflin: actin complex localizes to sites of dynamic actin polymerization at the leading edge of migrating cells and pathogen-induced actin tails. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2008;87:893–904. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim M.J., Lee Y.S., Han G.Y., et al. Proflin 2 promotes migration, invasion, and stemness of HT29 human colorectal cancer stem cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2015;79:1438–1446. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2015.1043118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan J., Ma C., Gao Y. MicroRNA-30a-5p suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition by targeting proflin-2 in high invasive nonsmall cell lung cancer cell lines. Oncol. Rep. 2017;37:3146–3154. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang Y.N., Ding W.Q., Guo X.J., et al. Epigenetic regulation of Smad2 and Smad3 by proflin-2 promotes lung cancer growth and metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8230. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su J., Morgani S.M., David C.J., Wang Q., Er E.E., Huang Y.H., Basnet H., Zou Y., Shu W., Soni R.K., Hendrickson R.C., Hadjantonakis A.K., Massagué J. TGF-β orchestrates fibrogenic and developmental EMTs via the RAS effector RREB1. Nature. 2020;577(7791):566–571. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1897-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fan C., Wang Q., Kuipers T.B., Cats D., Iyengar P.V., Hagenaars S.C., Mesker W.E., Devilee P., Tollenaar R.A.E.M., Mei H., Ten Dijke P. LncRNA LITATS1 suppresses TGF-β-induced EMT and cancer cell plasticity by potentiating TβRI degradation. EMBO J. 2023;42(10) doi: 10.15252/embj.2022112806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ren C., Zhang Z., Wang S., Zhu W., Zheng P., Wang W. Circular RNA hsa_circ_0001178 facilitates the invasion and metastasis of colorectal cancer through upregulating ZEB1 via sponging multiple miRNAs. Biol. Chem. 2020;401(4):487–496. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2019-0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu L., Zhu H., Wang Z., Huang J., Zhu Y., Fan G., Wang Y., Chen X., Zhou G. Circular RNA circFIRRE drives osteosarcoma progression and metastasis through tumorigenic-angiogenic coupling. Mol. Cancer. 2022;21(1):167. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01624-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Z.H., Chen Y.B., Yue H.R., Zhou X.J., Ma H.Y., Wang X., Cao X.C., Yu Y. PAX5-miR-142 feedback loop promotes breast cancer proliferation by regulating DNMT1 and ZEB1. Mol. Med. 2023;29(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s10020-023-00681-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu S.L., Cai C., Yang Z.Y., Wu Z.Y., Wu X.S., Wang X.F., Dong P., Gong W. DGCR5 is activated by PAX5 and promotes pancreatic cancer via targeting miR-3163/TOP2A and activating Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(2):498–513. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.55636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin Y., Morgunova E., Jolma A., Kaasinen E., Sahu B., Khund-Sayeed S., et al. Impact of cytosine methylation on DNA binding specificities of human transcription factors. Science. 2017;356(6337):eaaj2239. doi: 10.1126/science.aaj2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bannister A.J., Miska E.A. Regulation of gene expression by transcription factor acetylation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2000;57(8–9):1184–1192. doi: 10.1007/PL00000758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.