Abstract

A type II polyketide synthase gene cluster located in the terminal inverted repeats of Streptomyces ambofaciens ATCC 23877 was shown to be responsible for the production of an orange pigment and alpomycin, a new antibiotic probably belonging to the angucycline/angucyclinone class. Remarkably, this alp cluster contains five potential regulatory genes, three of which (alpT, alpU, and alpV) encode proteins with high similarity to members of the Streptomyces antibiotic regulatory protein (SARP) family. Deletion of the two copies of alpV (one in each alp cluster located at the two termini) abolished pigment and antibiotic production, suggesting that AlpV acts as a transcriptional activator of the biosynthetic genes. Consistent with this idea, the transcription of alpA, which encodes a ketosynthase essential for orange pigment and antibiotic production, was impaired in the alpV mutant, while the expression of alpT, alpU, and alpZ, another regulatory gene encoding a γ-butyrolactone receptor, was not significantly affected. Real-time PCR experiments showed that transcription of alpV in the wild-type strain increases dramatically after entering the transition phase. This induction precedes that of alpA, suggesting that AlpV needs to reach a threshold level to activate the expression of the structural genes. When introduced into an S. coelicolor mutant with deletions of actII-ORF4 and redD, the SARP-encoding genes regulating the biosynthesis of actinorhodin and undecylprodigiosin, respectively, alpV was able to restore actinorhodin production only. However, actII-ORF4 did not complement the alpV mutant, suggesting that AlpV and ActII-ORF4 may act in a different way.

Streptomyces organisms are gram-positive soil-inhabiting filamentous bacteria that undergo a complex process of morphological differentiation and produce a great variety of secondary metabolites, including antibiotics with important applications in human medicine and in agriculture.

The majority of these antibiotics are the products of complex biosynthetic pathways that are activated in a growth phase-dependent manner, i.e., upon entry into stationary phase or following a reduction in growth rate in liquid-grown cultures. On solid cultures, production of these compounds generally coincides with the onset of aerial mycelium formation. The activation of antibiotic biosynthesis is genetically controlled at several levels. The most fundamental level involves genes encoding pleiotropic regulators which control both secondary metabolism and morphological differentiation. Many bld genes, for example, are known to govern both sporulation and antibiotic production (6). The best-studied example is bldA, which encodes the tRNA for the rare leucine codon UUA. In Streptomyces coelicolor, the presence of this rare codon in the regulatory genes adpA, actII-ORF4, and redZ explains, respectively, the morphological defects and the loss of the actinorhodin and undecylprodigiosin antibiotic production of bldA mutants (12, 17, 42, 44). At the next level, genes exert their control over two or more antibiotics in the same organism but have no effects on morphological differentiation. A nice example are the three genes afsK, afsR, and afsS in S. coelicolor whose products are the components of a linear signal transduction system involved in the production of actinorhodin, undecylprodigiosin, and a calcium-dependent antibiotic (13, 21, 27). Finally, the most specific level of control concerns genes encoding regulators that act only on one biosynthetic pathway. These genes, whose expression is partly dependent on pleiotropic regulators, are usually found physically linked to the structural antibiotic biosynthesis genes on the chromosomes of streptomycetes. This contrasts with the global regulatory genes which can be located far from the clusters they control.

In most cases, the pathway-specific regulators play a positive role in the transcription of the biosynthetic genes, although some act as transcriptional repressors (28, 38, 47).

The group of proteins referred to as SARPs (for Streptomyces antibiotic regulatory proteins) (45) is prominent among the pathway-specific regulators in streptomycetes. Some members of this family, however, e.g., AfsR, are pleiotropic regulators. The SARPs are DNA-binding proteins sharing sequence similarities with several members of the OmpR family of DNA-binding domains (45). They are typified by the S. coelicolor transcriptional activators ActII-ORF4 and RedD that, respectively, control production of actinorhodin (12) and undecylprodigiosin (41), by the Streptomyces peucetius DnrI protein which regulates daunorubicin biosynthesis (26), and by CcaR, an activator of the cephamycin C and clavulanic acid biosynthesis in Streptomyces clavuligerus (31). These proteins act at the bottom of regulatory cascades and turn on the expression of biosynthetic genes present in their respective gene clusters.

Numerous SARP-encoding genes have been characterized by sequence analysis of antibiotic biosynthetic gene clusters, and in the majority of cases, these clusters harbor a single gene coding for a SARP. Some clusters, however, do possess more than one SARP-encoding gene. For example, the pristinamycin gene cluster of Streptomyces pristinaespiralis contains two SARP genes (14), as do the griseorhodin biosynthesis cluster from a marine species of Streptomyces (23) and the Streptomyces galilaeus aclacinomycin cluster (33). In Streptomyces fradiae, the tylosin antibiotic biosynthesis gene cluster contains five regulatory genes (tylP, tylQ, tylR, tylS, and tylT), one of the richest collection of regulators encountered in a single cluster (2). Among them, tylS and tylT encode SARPs, with TylS being essential for tylosin production and TylT not (2). Interestingly, these genes, together with tylP and tylQ, are congregated in a regulatory subcluster that is separated by about 60 kb from the tylR regulator (2).

We recently identified a gene cluster encoding an aromatic (type II) polyketide synthase (PKS) in the terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) of the linear Streptomyces ambofaciens ATCC 23877 chromosome (30). We have shown that this cluster, named alp, was responsible for the synthesis of an orange pigment and a new antibiotic probably belonging to the angucyclinone or angucycline class (30) that we named alpomycin. These compounds are two distinct molecules, and based on the timing of their appearance in cultures, alpomycin may be an intermediate in the biosynthesis of the pigment (30). Remarkably, the alp cluster contains up to five potential regulatory genes (alpT, alpU, alpV, alpW, and alpZ) that are congregated in a subcluster at one end of the alp cluster. Even more remarkably, three of these are SARP-encoding genes (alpT, alpU, and alpV), a situation never before described in a type II PKS gene cluster.

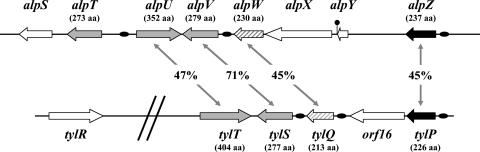

The presence of five regulatory genes suggests a complex cascade of events regulating the production of pigment and antibiotic by the alp cluster, a cascade which may be similar to that regulating the biosynthesis of tylosin in S. fradiae. Indeed, the alp regulatory locus from alpU to alpZ shows a gene organization similar to that of the tyl regulatory subcluster (Fig. 1). Among the tyl regulatory genes, only tylR and tylS have been shown to be essential for tylosin production (2, 3). The alp cluster contains an orthologue to tylS (alpV) but no tylR homologue, and in this study, we focus on the role of alpV in pigment and alpomycin production. We show that AlpV is essential for the biosynthesis of both the orange pigment and alpomycin and that it probably acts as a direct transcriptional activator of the biosynthetic genes.

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of the S. ambofaciens alpomycin regulatory cluster and comparison with the tylosin regulatory cluster of S. fradiae. Genes in grey encode a SARP, genes in black encode a γ-butyrolactone receptor, and the genes in hatched grey encode a product similar to the BarB transcriptional repressor. The deduced products of orf16, alpY, and alpX are a cytochrome P450 (2), a protein of unknown function, and a decarboxylase (30), respectively. The percentage of identity at the amino acid level is indicated for the orthologous genes. Horizontal filled ovals symbolize the locations of the ARE sequences (i.e., the candidate target sites for the γ-butyrolactone receptors, AlpZ in the alp cluster and TylP in the tyl cluster) (39) (see Discussion), and the filled circle symbolizes the transcriptional terminator as defined by TransTerm (10).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

All strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1. Streptomyces manipulations were as previously described (30). Pigment and antibiotic production were assessed on R2 medium (19), and R2 liquid cultures were used for RNA isolation. Luria-Bertani (LB) and SOB liquid media (36) were used for growing Escherichia coli, and LB was used for growing Bacillus subtilis. Ampicillin (50 μg/ml), apramycin (50 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), nalidixic acid (25 μg/ml), and spectinomycin (50 μg/ml), all from Sigma, were added to growth media when required. For the PCR-targeted mutagenesis (see below), l-arabinose (10 mM final concentration; Sigma) was added to SOB medium to induce the λ-red system (9). Conjugation between S. ambofaciens and E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 containing the cosmid or plasmid of interest was performed according to the method described in reference 19, except that HT agar medium (19) supplemented with MgCl2 (10 mM) was used instead of SFM MgCl2 (10 mM).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain, cosmid, or plasmid | Relevant property(ies)a | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. ambofaciens | ||

| ATCC 23877 | Wild-type | 32 |

| DMV1 | alpV loci on two chromosomal arms replaced by aac(3)-IV/oriT cassette | This study |

| SVC1 | alpV loci on two chromosomal arms replaced by a scar | This study |

| COMV1 | SVC1 transformed with pSET152-alpV | This study |

| COMVCK1 | SVC1 transformed with pSET152 | This study |

| S. coelicolor | ||

| M512 | ΔactII-ORF4 ΔredD mutant | 13 |

| M512(pSET152-alpV) | M512 transformed with pSET152-alpV | This study |

| M512(pSET152) | M512 transformed with pSET152 | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | General cloning strain | 18 |

| ET12567 | Strain used for conjugation between E. coli and Streptomyces | 25 |

| BW25113 | Strain used for PCR-targeted mutagenesis | 9 |

| B. subtilis ATCC 6633 | Strain used as an indicator in bioassays | |

| Cosmids or plasmids | ||

| F6 | Cosmid from the genomic library of S. ambofaciens ATCC 23877; bla, neo | 20 |

| F6ΔalpV::aac(3)-IV/oriT | alpV replaced by aac(3)-IV/oriT cassette; bla, neo | This study |

| F6ΔalpV::scar | alpV replaced by 81-bp scar | This study |

| F6::aadA/oriT-ΔalpV::scar | alpV replaced by 81-bp scar; neo gene replaced by aadA/oriT cassette; bla | This study |

| BT340 | FLP recombination plasmid; flp, bla, cat, repA101 | 9 |

| pUZ8002 | Used to mobilize in trans cosmid containing oriT locus | 29 |

| pIJ773 | oriT, aac(3)-IV | 16 |

| pIJ778 | oriT, aadA | 16 |

| pIJ790 | gam, bet, exo, cat | 16 |

| pSET152 | oriT, attP, int, aac(3)-IV | 4 |

| pSET152-alpV | oriT, attP, int, aac(3)-IV, alpV | This study |

cat, chloramphenicol resistance gene; gam, inhibits the host exonuclease V; bet, single-stranded DNA binding protein; exo, exonuclease promoting recombination together with bet; bla, ampicillin resistance gene; aac(3)-IV, apramycin resistance gene; aadA, spectinomycin and streptomycin resistance gene; neo, kanamycin resistance gene; int, integrase gene; oriT, origin of transfer; flp, gene encoding the FLP recombinase; repA101, thermosensitive replication origin.

DNA and RNA manipulations.

Isolation (including that for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis), cloning, and manipulation of DNA were carried out as described previously in references 20 and 30 for Streptomyces and in reference 36 for E. coli. Restriction enzymes and molecular biology reagents were purchased from New England Biolabs and Roche Diagnostics. PCR products were purified by using the High-Pure PCR product purification kit (Roche), while restriction fragments were purified from agarose gels by using the Geneclean procedure (Bio 101). Southern blots were performed by using a Hybond-N nylon membrane (Amersham-Pharmacia) and a vacuum transfer system (Bio-Rad). Probe DNA was labeled with digoxigenin dUTP (Roche). Light emission was detected with a Fluor-S MultImager (Bio-Rad).

Total RNAs were isolated from an R2 liquid-grown culture of S. ambofaciens as previously described (19).

RT-PCR and real-time PCR.

The method used for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis was as previously described in reference 30. Briefly, cDNAs were obtained after reverse transcription of 5 μg of DNAse I-treated total RNA with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (USB Corporation) and random hexamer primers (pdN6; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc.). Primer pairs alpV-1-alpV-2, KSI-F-KSI-R, alpT-1-alpT-2, alpU-1-alpU-2, alpZ-1-alpZ-2, and hrdB-F-hrdB-R (Table 2) were then used to analyze the cDNAs for alpV, alpA, alpT, alpU, alpZ, and hrdB-like gene expression, respectively. PCR conditions were as follows: 4 min at 95°C, 30 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 30 s at 72°C followed by a final extension of 7 min at 72°C. Control PCRs were similarly performed with RNA untreated by reverse transcriptase to confirm the absence of contaminating DNA in the RNA preparations. The sizes of the PCR products from cDNAs were 175, 104, 94, 129, 129, and 109 bp for alpA, alpV, alpT, alpU, alpZ, and hrdB, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this work

| Use | Primer | Nucleotide sequence (5′-3′)a |

|---|---|---|

| Construction of mutant | alpV-replace1 | GTCATGGGTGGGGCCCGTGACGGAGGGTGCGGGGTGTCATGTAGGCTGGACCTGCTTC |

| strains and control | alpV-replace2 | GATCACCCGGCCTGCGGCCTGACTCATGGGGGAAACGTGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| of gene replacement | CV1 | TTGACAAACCGACTGTGC |

| CV2 | TCATGTGGAGCTGCTGC | |

| Complementation | AlpV-amplify1 | CGCGGATCCGGCACGTCATGGGTG |

| AlpV-amplify2 | GCGAATTCAATAAGACCGCAAGGTCTGTTC | |

| Construction of | Kan-1 | ATGATTGAACAAGATGGATTGCACGCAGGTTCTCCGGCCATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| conjugative cosmids | Kan-2 | TCAGAAGAACTCGTCAAGAAGGCGATAGAAGGCGATGCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| Real-time and RT- | alpV-1 | GAAGTGCTGGGGACGCTG |

| PCR | alpV-2 | TGGTCGGCGTTGAGGG |

| alpT-1 | GAGCAGAGCCGCCTGGT | |

| alpT-2 | CCAGGTCGGTGAGTTCGG | |

| alpU-1 | CAGATTCACGACGAGCGG | |

| alpU-2 | CCACAACTCGTCCACCAGG | |

| alpZ-1 | AGGAACTGCGTGCGGAGT | |

| alpZ-2 | CAGCCACGCACTCTCGG | |

| hrdB-F | CGCGGCATGCTCTTCCT | |

| hrdB-R | AGGTGGCGTACGTGGAGAAC | |

| KSI-F | CCACGACGAACCCGAGTG | |

| KSI-R | GTAGGCGTTGGAGCGGGT |

For the primers alpV-replace1 and alpV-replace2, the sequences in boldface type correspond to the sequences immediately upstream (alpV-replace2) and downstream (alpV-replace1) of alpV, and include the stop and start codons (underlined). For Kan-1 and Kan-2, the sequences in boldface type correspond to the sequences upstream (Kan-1) and downstream (Kan-2) of the neo gene from SuperCos1 (11). The 3′ ends of these four primers match a different end of the resistance cassette. For the primers AlpV-amplify1 and AlpV-amplify2, the sequences in boldface type correspond, respectively, to the BamHI and EcoRI sites used for cloning into pSET152.

Real-time PCRs were performed as described in reference 30 and carried out on an iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Briefly, 5 μl of cDNAs was mixed together with 12.5 μl of Platinum Quantitative PCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen) and 3.3 μl of SYBR Green I (10,000× dilution; Sigma) together with 10 pmol of each primer in a final volume of 25 μl. The mix was submitted to the following thermal cycles: 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C followed by 60 repeats of 30 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C, and then 80 steps of 10 s with a temperature gradient increase of 0.5°C per step from 55 to 94°C. This last step allowed the melting curve of the PCR products and, consequently, their specificity to be determined. For each run, a standard dilution of the cDNA was used to check the relative efficiency and quality of primers. A negative control (distilled water) was included in all real-time PCR assays, and each experiment was performed in duplicate. The hrdB-like gene [hrdB encodes the major sigma factor in S. coelicolor A3(2) (5)] was used as an internal control to quantify the relative expression of target genes, as it is expressed fairly constantly throughout growth.

In-frame deletion of alpV. (i) Replacement of alpV by the aac(3)-IV/oriT cassette.

The strategy used for gene disruption was based on the PCR-targeted system (16) and was carried out as described in previous work (30). The primer set alpV-replace1-alpV-replace2 (Table 2) was used to amplify the aac(3)-IV/oriT cassette from pIJ773 (16). PCR conditions for amplification of the resistance cassette, the method of gene replacement in the F6 cosmid containing the alp gene cluster (30), and the method of allelic exchange in S. ambofaciens were as described in references 16 and 30. Allelic exchanges were confirmed by Southern blot and PCR analysis with primers CV1 (100 nucleotides downstream from the stop codon of alpV) and CV2 (117 nucleotides upstream from the start codon of alpV), giving a product of 1,053 bp in the wild type and 1,601 bp after replacement with the aac(3)-IV/oriT cassette.

(ii) In-frame deletion of alpV in the F6 cosmid mediated by FLP recombinase.

To generate a nonpolar, unmarked in-frame deletion of alpV in F6, we used the method described by Gust et al. (16). Briefly, F6ΔalpV::aac(3)-IV/oriT was introduced into E. coli DH5α/BT340 cells (9). BT340 shows temperature-sensitive replication and encodes the thermoinducible FLP recombinase. Transformants were selected on LB agar containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol and incubated at the permissive temperature (30°C). A few colonies were single colony purified nonselectively at 42°C. The FLP recombinase acts on FRT sites flanking the aac3(IV)/oriT cassette to remove the central part of the disruption cassette, leaving behind an 81-bp scar sequence (9). Colonies resistant to kanamycin but sensitive to apramycin (deletion of the cassette) and to chloramphenicol (loss of BT340) were selected. The deleted cosmid (F6ΔalpV::scar) was confirmed by restriction and by PCR analysis with primers CV1 and CV2 (expected size, 298 bp).

(iii) Construction of F6::aadA/oriT-ΔalpV::scar.

To introduce the cosmid containing the alpV in-frame deletion into the S. ambofaciens DMV1 mutant (Table 1) and, consequently, to generate a nonpolar in-frame mutation on the chromosome, the cosmid F6 ΔalpV::scar was made proficient for conjugation by replacing its neo gene with an aadA/oriT cassette by λ-Red-mediated recombination. The primers Kan-1 and Kan-2 (Table 2) were used to amplified the aadA/oriT cassette from pIJ778 (16). The purified PCR product was introduced into induced E. coli BW25113/pIJ790 cells (16) containing F6 ΔalpV::scar, and transformants were streaked onto LB agar containing spectinomycin. The modified cosmid F6::aadA/oriT-ΔalpV::scar was isolated from Sptr Kans transformants, and its structure was confirmed by BamHI restriction analysis.

(iv) In-frame deletion of alpV in S. ambofaciens.

F6::aadA/oriT-ΔalpV::scar was introduced into the S. ambofaciens DMV1 mutant (Table 1) by intergenic conjugation, and exconjugants resistant to spectinomycin were selected. Subsequent screening for the loss of both Sptr and the resistance (Aprr) derived from the marked deletion in the S. ambofaciens mutant indicated the successful replacement of the resistance marker with an unmarked, in-frame deletion. The structure of the mutant with the alpV deletion (SVC1) (Table 1) was confirmed by Southern blotting, by PCR analysis with the CV1-CV2 primer set, and by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

Complementation of the alpV mutant.

AlpV-amplify1 and AlpV-amplify2 (Table 2) were used to amplify a DNA region of the F6 cosmid spanning from the last 25 bp of alpU to the nucleotide adjacent to the stop codon of alpW (Fig. 1), therefore including the alpV coding DNA sequence and its putative promoter and terminator sequences. PCR was carried out by using high-fidelity enzyme (Finnzyme) with the following conditions: 2 min at 94°C; 30 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 60 s at 72°C; followed by a final extension of 10 min at 72°C. The 1,291-bp PCR product was cut by EcoRI and BamHI, purified by Geneclean, and cloned into the integrative pSET152 vector (4) (Table 1) previously digested by the same enzymes.

The newly generated pSET152-alpV plasmid was then introduced into the S. ambofaciens in-frame alpV deletion mutant SVC1 by intergenic conjugation. Site-specific integration of the plasmid into the attB chromosomal site allowed selection of Aprr exconjugants.

Bioassays and reverse-phase HPLC.

Bioassays were carried out as previously described (30) with B. subtilis ATCC 6633 as the indicator strain. Extraction of the alp cluster-derived antibiotic from R2 liquid cultures and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) conditions with a reverse-phase LichroCart C18 column (250- by 4-mm inner diameter, 5-μm particle size, 10-nm porosity; Merck) for the separation of the antibiotic were carried out as previously described (30).

RESULTS

The alpV gene is part of a large regulatory subcluster.

Sequence analysis of the alp type II PKS gene cluster located in the TIRs of the S. ambofaciens ATCC 23877 linear chromosome has revealed the presence of five putative regulatory genes, alpT, alpU, alpV, alpW, and alpZ (Fig. 1) (30). Based on the genetic organization illustrated in Fig. 1, it is likely that alpV is transcribed as a monocistronic RNA. Indeed, although no terminator could be identified between alpW and alpV, the size of this intergenic region (409 bp) is compatible with the presence of a transcriptional promoter site. The presence of a transcriptional regulatory motif, an ARE (autoregulatory element) site (14) (Fig. 1; see also Fig. 7 and Discussion), upstream of alpV reinforces this hypothesis. The other regulatory genes are also probably transcribed as monocistronic RNAs, with the exception of alpW. Indeed, the stop codon of the upstream alpX gene is located only 12 bp from the alpW start codon, suggesting that these two genes could be cotranscribed. For alpZ, the gene located upstream is divergently orientated (data not shown). The alpV gene, like the other regulatory genes, does not contain a TTA codon, indicating that the expression of their products does not depend on the bldA tRNA gene (22).

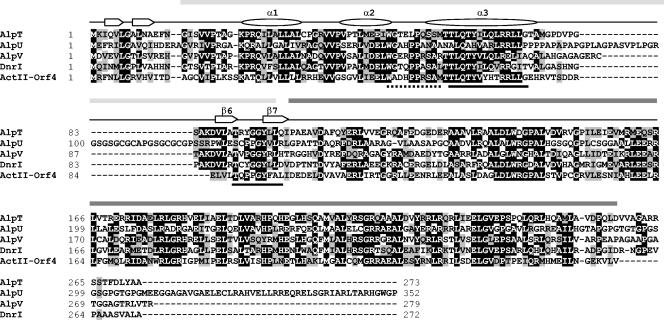

FIG. 7.

Alignment of the putative AlpZ binding sites with the ARE consensus proposed in reference 14. The distance between an ARE site and the start codon of the downstream gene is indicated. The letters Y, K, and W represent C or T, G or T, and A or T, respectively.

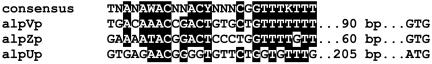

Analysis of the deduced sequence of the protein encoded by alpV revealed significant similarity to the putative products of the alpU and alpT genes and to members of the SARP family (Fig. 2). All contain the transcriptional regulatory protein C-terminal (trans_reg_C) domain (PF00486) and the bacterial transcriptional activator domain (PF03704) in their N and C termini, respectively (Fig. 2). Secondary structure prediction analysis with the PROF program (http://cubic.bioc.columbia.edu/predictprotein/) (35) confirmed the presence of helices and β-sheets proposed to interact with DNA in the SARPs as well as the loop proposed to interact with the RNA polymerase (37, 45) (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, the 44-residue distance between the α3 helix and the β6 sheet (according to the nomenclature of reference 45) in AlpU (whose sequence has been recently updated [accession number AAR30165]) is much longer than that previously observed in the SARPs (e.g., 12 and 16 residues for AlpT and AlpV, respectively). The amino acid sequence of this spacer is of low complexity and is rich in glycine residues. According to the PROF analysis, this region forms a loop (data not shown), and therefore, this particularly long spacer would not be predicted to affect the DNA binding activity of AlpU. The deduced product of alpZ shares homologies with γ-butyrolactone receptors, while AlpW exhibits similarities with transcriptional repressors such as BarB from Streptomyces virginiae (28), TylQ from S. fradiae (38), and JadR2 from Streptomyces venezuelae (47). This family of repressors corresponds to DNA-binding proteins with moderate similarity to γ-butyrolactone receptors.

FIG. 2.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the alp cluster-encoded SARPs with the well-characterized DnrI and ActII-ORF4. The predicted secondary structures for AlpT, AlpU, and AlpV were determined with PROF (35). The numbering of the α-helices and β-sheets is according to that described in reference 45. Regions proposed to make contact with DNA (black bars) and holo-RNAP (hatched bar) are marked. The trans_reg_C (PF00486) domain and bacterial transcriptional activator domain (PF03704) (see Results) are shown by a grey bar and a dark grey bar, respectively.

Interestingly, the locus containing alpU, alpV, alpW, and alpZ shows a strong synteny with that spanning from tylT to tylP from the S. fradiae tylosin cluster, with the exception of the genes located between alpW and alpZ and between tylQ and tylP (Fig. 1) (2). Indeed, based on sequence homology, AlpU, AlpV, AlpW, and AlpZ can be considered orthologues of TylT, TylS, TylQ, and TylP, respectively. AlpT has no equivalent in the tyl cluster.

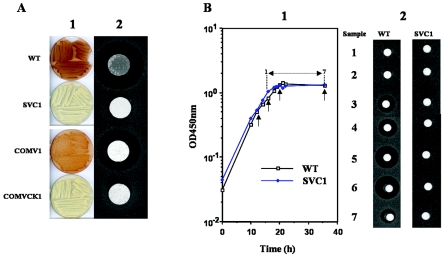

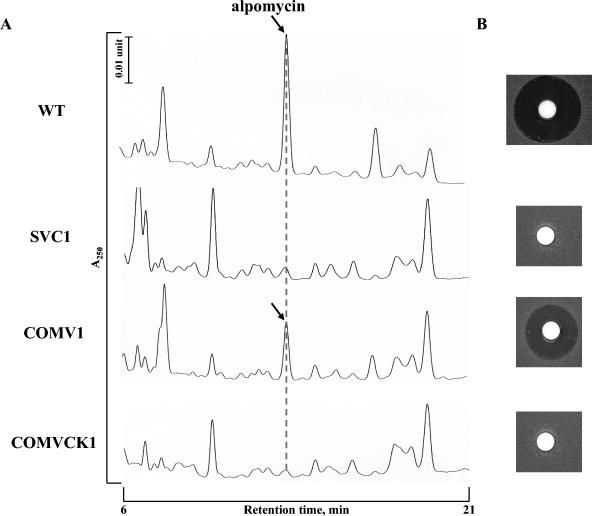

Loss of pigment and antibiotic production in SVC1.

In-frame deletion of the two copies of alpV was carried out as described in Materials and Methods and allowed the isolation of the SVC1 strain. The mutant strain showed growth and morphological characteristics identical to those of the S. ambofaciens wild-type strain when grown on HT, MM, R2YE, SMMS, and R2 solid media (19) or in R2 liquid medium (Fig. 3B). The production of the diffusible orange pigment and of alpomycin, the two phenotypes related to the alp cluster (30), were then assessed for SVC1 by its appearance during growth on R2 medium and by bioassay. As shown Fig. 3A, the mutant failed to produce the diffusible orange pigment on R2 medium even after a long period of growth (up to 10 days). Antibiotic activity was tested after 3 days of growth on R2 medium by transferring an agar plug of the wild-type and SVC1 strains onto an LB plate seeded with B. subtilis spores. While a large zone of growth inhibition was observed with the wild-type strain plug after an overnight incubation, none was detected with the SVC1 plug. We have previously demonstrated that under these conditions the macrolide antibiotic spiramycin produced by S. ambofaciens does not interfere with the bioactivity test (30). The same results were also observed when similarly testing supernatants of SVC1 and wild-type R2 liquid cultures (Fig. 3B). This inability of SVC1 to synthesize alpomycin was further confirmed by HLPC analysis of culture supernatant extracts (Fig. 4). No peak corresponding to alpomycin was observed in the SVC1 extract.

FIG. 3.

Effect of alpV deletion on pigment and antibiotic production. (A) Pigment production tested on R2 agar for the wild-type (WT), SVC1, COMV1 (SVC1 transformed with pSET152-alpV), and COMVCK1 (SVC1 transformed with pSET152) strains (column 1; the plates were photographed from below). Column 2 shows antibacterial activity against B. subtilis ATCC 6633. Bacteria were grown on R2 agar for 3 days, and a plug of mycelia was placed on an LB plate seeded with B. subtilis. (B) Antibiotic production tested in R2 liquid medium. Growth curves of wild-type and SVC1 strains are given in panel 1, and the results for bioassays from time points 1 to 7 in these curves are presented in panel 2. The four arrows in panel 1 indicate the four points from which total RNAs were extracted and used in transcriptional analysis (Fig. 6).

FIG. 4.

(A) Comparison of HPLC analyses of ethyl acetate extracts from S. ambofaciens wild-type (WT) and noncomplemented and complemented SVC1 strains. The arrows indicate the peak corresponding to the alpomycin antibiotic. Detection was carried out at 250 nm. A linear gradient from 40 to 98% acetonitrile was applied in the presence of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid with a flow rate of 1 ml · min−1. (B) Bioassays of the HPLC fractions corresponding to the dotted line for antibacterial activity against B. subtilis ATCC 6633.

Complementation experiments were carried out with pSET152-alpV (Table 1), an integrative and conjugative plasmid containing the coding sequence of alpV and its flanking intergenic regions (see Materials and Methods). As a control, SVC1 was also transformed with pSET152. Exconjugants showed a wild-type phenotype for growth and morphological differentiation on different media. However, the SVC1 clones containing pSET152-alpV, e.g., the COMV1 strain, were able to synthesize the orange pigment and bioactive compound on R2 medium. The exconjugants containing the vector alone, e.g., COMVCK1, did not recover these properties (Fig. 3A). HPLC analysis confirmed that the bioactive compound was the alpomycin antibiotic (Fig. 4). It is noticeable that production of the two compounds did not return to wild-type levels (Fig. 3A), consistent with the reintroduction of only a single copy of the alpV locus.

These results strongly suggest that AlpV acts as a positive regulator of the orange pigment and alpomycin production.

Complementation of an actII-ORF4 mutant by alpV.

It has previously been demonstrated that certain SARP-encoding genes can substitute for certain others (40). We thus tested whether AlpV could functionally replace ActII-ORF4 and/or RedD, two SARPs in S. coelicolor that promote activation of the actinorhodin and undecylprodigiosin structural genes, respectively. S. coelicolor M512, a ΔactII-ORF4 ΔredD double mutant (13), was transformed with pSET152 or pSET152-alpV, and the exconjugants were checked for the biosynthesis of the blue (actinorhodin)- and red (undecylprodigiosin)-pigmented antibiotics. The presence of alpV restored actinorhodin production in M512 but not that of the prodiginine antibiotic, while pSET152 alone had no effect on the production of either pigment (data not shown). The reciprocal complementation, however, did not work, and introduction of actII-ORF4 into SVC1 failed to restore production of the orange pigment (data not shown). This suggests that AlpV and ActII-ORF4 may recognize different binding sites (see Discussion).

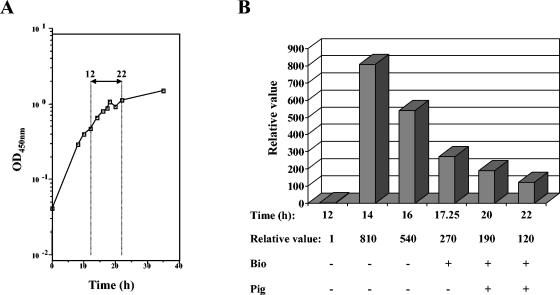

Transcriptional analysis of alpV in S. ambofaciens ATCC 23877.

We previously showed that the expression of alpA, the structural gene encoding the ketosynthase responsible for the pigment and alpomycin production, was strongly induced at late transition phase when S. ambofaciens ATCC 23877 was grown in R2 liquid cultures. Antibiotic activity could subsequently be detected by bioassay less than 90 min following the induction (30). Based on the phenotype of SVC1, this alpA induction could therefore depend on a prior increase of alpV expression. In S. coelicolor, the transcription of actII-ORF4 and redD has to reach a certain minimum level before expression of the act and red biosynthetic structural genes, respectively, occurs (15, 41). Therefore, the expression of alpV was quantified in the wild-type strain by real-time PCR (see Material and Methods) (Fig. 5) by using the same cDNA samples as those used to determine the transcription pattern of alpA in reference 30. A significant increase in alpV transcription (about 800-fold) was observed at 14 h (early transition phase) of growth (Fig. 5B), followed by a steady decrease in expression, reaching a relative value of 120 at 22 h (stationary phase). In previous results, the relative expression of alpA increased approximately 7,000-fold in the same samples but only after 16 h of growth (30), thus supporting our hypothesis that transcription of alpA depends on alpV.

FIG. 5.

Transcriptional analysis of alpV expression. (A) Growth curve of the wild-type strain in R2 liquid medium; (B) quantification of alpV expression from 12 to 22 h of growth by real-time PCR analysis. Relative values are in comparison to hrdB, which was used as an internal control (see Materials and Methods). The relative value for the 12-h sample was arbitrarily assigned as 1. The assessment of antibiotic activity against B. subtilis ATCC 6633 (Bio) and the pigment production (Pig) for each sample is indicated under the panel. +, detected; −, not detected; OD450, optical density at 450 nm.

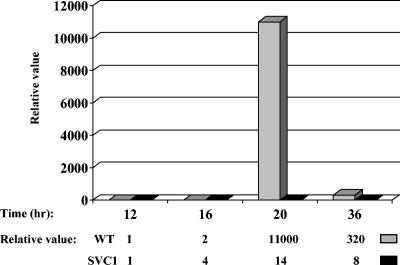

Transcription analysis in the SVC1 mutant strain.

To confirm the relationship between the expression level of alpV and alpA, we analyzed the transcription of the structural gene in SVC1. Total RNAs were extracted from the wild-type and SVC1 strains at 12, 16, 20, and 36 h of growth in R2 liquid medium (Fig. 3B) and were used to perform real-time PCR as before. Figure 6 shows that the expression of alpA is strongly impaired in the SVC1 strain compared to the wild type. In the wild-type strain, the expression of alpA showed a significant relative increase of 11,000-fold at 20 h and was still high at 36 h (320-fold), while it was very low and fairly constant (only a 14-fold increase at 20 h and an 8-fold increase at 36 h) throughout the time course in SVC1. This is consistent with AlpV acting as a direct transcriptional activator of alpA and, more probably, of the alpIAB operon, since these three genes are terminally overlapping (30).

FIG. 6.

Quantification of alpA expression in the wild-type (WT) and SVC1 strains by real-time PCR analysis. Total RNAs were extracted after 12, 16, 20, and 36 h of growth (growth curves are shown in Fig. 3). Relative values are in comparison to hrdB, which was used as an internal control (see Materials and Methods). The relative value for the 12-h sample was arbitrarily assigned as 1.

We also checked, by RT-PCR, the transcription of the two other SARP-encoding genes, alpT and alpU, and of the γ-butyrolactone receptor gene, alpZ, in the wild-type and alpV backgrounds by using the same cDNA. The three regulatory genes are expressed all along the growth, and their expression did not seem to be significantly affected by the alpV disruption (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The alp gene cluster of S. ambofaciens ATCC 23877, responsible for the synthesis of an orange pigment and of an angucycline-like antibiotic, is particularly original as it encodes five regulators, including three SARPs (encoded by alpT, alpU, and alpV) and at least one protein (encoded by alpZ) associated with signal transduction involving diffusible microbial hormones, i.e., γ-butyrolactones. To date, no similar situation has been described for type II PKS clusters, including those responsible for angucycline biosynthesis. For example, the S. venezuelae jadomycin, the Streptomyces cyanogenus landomycin A, and the Streptomyces antibioticus oviedomycin biosynthesis clusters, where the structural genes both show strong synteny to those in the alp cluster (30), contain, respectively, three (43, 46), two (34), and two (24) regulatory genes, none encoding a SARP. A high degree of synteny was, however, found between four of the alp regulatory genes and those present in the regulatory subcluster controlling tylosin biosynthesis (Fig. 1) (2). This was surprising, since tylosin is a macrolide antibiotic produced by a type I PKS gene cluster (8), and it is possible that the locus spanning from alpU to alpZ could have arisen from horizontal gene transfer. However, more than one transfer event would have needed to occur, since orf16 (cytochrome P450) of the tyl cluster is absent in the alp regulatory subcluster, which instead contains two open reading frames, alpX (decarboxylase) and alpY (unknown function) (Fig. 1) (30). Our previous sequence analysis of this cluster suggested that alpT may have been acquired by another event of horizontal transfer involving a linear plasmid (30). In fact, the whole alp cluster seems to be a patchwork of different transfer events, with its location in the subtelomeric regions reinforcing this hypothesis (30).

The homology with the tyl regulatory subcluster also suggests the existence of a similar cascade of regulation between tylosin production (38) and the orange pigment and alpomycin production. A common point is that alpV is essential for alpomycin and pigment production like its orthologue, tylS, is essential to activate tylosin production (3). TylS controls the expression of tylR, whose product is a global activator of the tylosin biosynthetic pathway, plus at least one other gene yet to be identified (3). In S. ambofaciens, no tylR homolog has been detected in the alp cluster (even in the whole sequenced 200-kb TIRs) (data not shown). The target(s) of AlpV is(are), therefore, still unknown. However, several arguments suggest that AlpV may directly control the expression of the biosynthetic genes (at least that of the alpIAB operon) (30). First, we have shown in this work that alpV can complement an S. coelicolor mutant with a deletion of actII-ORF4, and this latter is known to act at the bottom of the regulatory cascade of actinorhodin production, directly activating transcription of operons of biosynthetic structural genes in the actinorhodin cluster (1, 15). Second, RT-PCR analyses revealed that in SVC1, the mutant with a deletion of the two copies of alpV, although transcription of alpA is strongly impaired, that of alpT, alpU, and alpZ is not significantly affected. This indicates that the observed effect of alpV on alpA transcription is not mediated via regulation of the expression of any of these three regulatory genes. In contrast, the tylS knockout strain of S. fradiae was reported to show no detectable expression of the tylR regulatory gene, now known to be the target of TylS activation (3). Third, the mutants with deletions of any of the four other alp regulators are still able to produce pigment and antibiotic activity (data not shown), suggesting that they could occupy a higher rank than alpV in the hierarchy of regulation. In addition, analysis of the alp promoter regions revealed the presence of a candidate target site for a γ-butyrolactone receptor (ARE) (14) upstream of alpV and also upstream of alpU and alpZ (Fig. 7), suggesting that alpV transcription could be regulated by AlpZ (and not vice versa). Preliminary gel mobility shift assays indeed show that AlpZ binds to the alpV promoter region (data not shown). Therefore, alpV expression is, at least partly, under the control of AlpZ, in a manner similar to the control of tylS expression by TylP (38), another common feature that the two regulatory systems share.

It has been demonstrated that the SARP proteins DnrI and ActII-ORF4 bind regions containing heptameric direct repeats (1, 37). The targets of the two proteins are remarkably similar in sequence, and this could explain why expression of dnrI can complement an actII-ORF4 mutant (40). However, although alpV is also able to restore actinorhodin production in an actII-ORF4 mutant, no sequences homologous to the heptameric direct repeats recognized by DnrI and ActII-ORF4 could be detected in the promoter region of the alpIAB operon (a probable target of AlpV) nor in any of the other intergenic regions of the alp cluster. Some sequences do exhibit similarity with SARP binding sites, but the length of the spacer between the repeats is not conserved and correct spacing is reported to be critical for productive protein-DNA interaction (37). Although we cannot rule out that AlpV may bind to these sites, it seems likely that AlpV recognizes a different DNA-binding motif than that known for other SARPs. This has already been proposed for another S. ambofaciens SARP (designated AlpT in our analysis) (30), which has been shown to induce actinorhodin production in an actII-ORF4 mutant by activating the transcription of the structural gene actI-ORF1 from a heptameric repeat-free promoter (7). The fact that AlpV may recognize an alternative binding site is also reinforced by the failure of actII-ORF4 to complement SVC1.

Our results demonstrate that AlpV is essential for orange pigment and alpomycin production in S. ambofaciens. Characterization of the mutants with deletions of the other regulatory genes will help to establish the hierarchy of the regulation steps, as may the construction of multiple mutants with deletions of more than one of the regulators. However, we can already propose a preliminary model in which AlpZ is located at the top of the cascade positively regulating, probably in response to a γ-butyrolactone, its own expression and also that of alpU and alpV. This is supported by the identification of ARE sequences upstream of each of these three genes, by the evidence of the binding of AlpZ on the alpV promoter (data not shown), and also by the fact that a mutant with a deletion of alpZ showed a reduction in both pigment and antibiotic production (this is the second example so far described of a γ-butyrolactone receptor having a positive role in antibiotic production after SpbR in S. pristinaespiralis) (14). In turn, AlpV would activate transcription of the structural genes, leading to the production of the polyketide compounds. We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that AlpV might act through the regulation of alpW, but if this is really the case, it would act as a repressor, since an alpW mutant overproduces pigment and antibiotic. Interestingly, although probably similar in their complexity, the cascades of regulation of tylosin and alpomycin production are different in several aspects in addition to the targets regulated by AlpV/TylS. For example, preliminary results show that AlpZ acts as an activator, while its orthologue TylP represses tylosin biosynthesis. In addition, their targets are only partly common (alpZ, alpV, and alpU for AlpZ and tylP [the alpZ orthologue], tylS [the alpV orthologue], and tylQ [the alpW orthologue] for TylP) (39) (Fig. 1). This confirms again the remarkable diversity of the mechanisms for antibiotic regulation in Streptomyces.

Acknowledgments

X.P. was supported by a grant of the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (grant “Accueil de Chercheur Etranger”) and by INRA. This work was initiated with a postdoctoral fellowship from Région Lorraine (to X.P.) and was also supported by the ACI microbiologie fondamentale, appliquée, environnementale et bioterrorisme, 2003, granted by the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche.

We thank Keith Chater, Tobias Kieser, and Bertolt Gust (John Innes Centre) for the PCR-targeted mutagenesis and Jean-Michel Girardet (Université Henri Poincaré) for help with the HPLC analyses. We are grateful to Andrew Hesketh (John Innes Centre) for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arias, P., M. A. Fernandez-Moreno, and F. Malpartida. 1999. Characterization of the pathway-specific positive transcriptional regulator for actinorhodin biosynthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) as a DNA-binding protein. J. Bacteriol. 181:6958-6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bate, N., A. R. Butler, A. R. Gandecha, and E. Cundliffe. 1999. Multiple regulatory genes in the tylosin biosynthetic cluster of Streptomyces fradiae. Chem. Biol. 6:617-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bate, N., G. Stratigopoulos, and E. Cundliffe. 2002. Differential roles of two SARP-encoding regulatory genes during tylosin biosynthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 43:449-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bierman, M., R. Logan, K. O'Brien, E. T. Seno, R. N. Rao, and B. E. Schoner. 1992. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene 116:43-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buttner, K. L., K. F. Chater, and M. J. Bibb. 1990. Cloning, disruption and transcriptional analysis of three RNA polymerase genes of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Bacteriol. 172:3367-3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Champness, W. C. 2000. Actinomycete development, antibiotic production, and phylogeny: questions and challenges, p. 11-31. In Y. V. Brun and L. J. Shimkets (ed.), Prokaryotic development. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Culebras, E., E. Martinez, A. Carnero, and F. Malpartida. 1999. Cloning and characterization of a regulatory gene of the SARP family and its flanking region from Streptomyces ambofaciens. Mol. Gen. Genet. 262:730-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cundliffe, E., N. Bate, A. Butler, S. Fish, A. Gandecha, and L. Merson-Davies. 2001. The tylosin-biosynthetic genes of Streptomyces fradiae. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 79:229-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ermolaeva, M. D., H. G. Khalak, O. White, H. O. Smith, and S. L. Salzberg. 2000. Prediction of transcription terminators in bacterial genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 301:27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans, G. A., K. Lewis, and B. E. Rothenberg. 1989. High efficiency vectors for cosmid microcloning and genomic analysis. Gene 79:9-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez-Moreno, M. A., J. L. Caballero, D. A. Hopwood, and F. Malpartida. 1991. The act cluster contains regulatory and antibiotic export genes, direct targets for translational control by the bldA tRNA gene of Streptomyces. Cell 66:769-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Floriano, B., and M. Bibb. 1996. afsR is a pleiotropic but conditionally required regulatory gene for antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 21:385-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folcher, M., H. Gaillard, L. T. Nguyen, K. T. Nguyen, P. Lacroix, N. Bamas-Jacques, M. Rinkel, and C. J. Thompson. 2001. Pleiotropic functions of a Streptomyces pristinaespiralis autoregulator receptor in development, antibiotic biosynthesis, and expression of a superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:44297-44306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gramajo, H. C., E. Takano, and M. J. Bibb. 1993. Stationary-phase production of the antibiotic actinorhodin in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) is transcriptionally regulated. Mol. Microbiol. 7:837-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gust, B., G. L. Challis, K. Fowler, T. Kieser, and K. F. Chater. 2003. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1541-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guthrie, E. P., C. S. Flaxman, J. White, D. A. Hodgson, M. J. Bibb, and K. F. Chater. 1998. A response-regulator-like activator of antibiotic synthesis from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) with an amino-terminal domain that lacks a phosphorylation pocket. Microbiology 144:727-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kieser, T., M. J. Bibb, M. J. Buttner, K. F. Chater, and D. A. Hopwood. 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 20.Leblond, P., G. Fischer, F. X. Francou, F. Berger, M. Guérineau, and B. Decaris. 1996. The unstable region of Streptomyces ambofaciens includes 210 kb terminal inverted repeats flanking the extremities of the linear chromosomal DNA. Mol. Microbiol. 19:261-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee, P. C., T. Umeyama, and S. Horinouchi. 2002. afsS is a target of AfsR, a transcriptional factor with ATPase activity that globally controls secondary metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 43:1413-1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leskiw, B. K., M. J. Bibb, and K. F. Chater. 1991. The use of a rare codon specifically during development? Mol. Microbiol. 5:2861-2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, A., and J. Piel. 2002. A gene cluster from a marine Streptomyces encoding the biosynthesis of the aromatic spiroketal polyketide griseorhodin A. Chem. Biol. 9:1017-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lombo, F., A. F. Brana, J. A. Salas, and C. Mendez. 2004. Genetic organization of the biosynthetic gene cluster for the antitumor angucycline oviedomycin in Streptomyces antibioticus ATCC 11891. Chembiochem 5:1181-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacNeil, D. J., K. M. Gewain, C. L. Ruby, G. Dezeny, P. H. Gibbons, and T. MacNeil. 1992. Analysis of Streptomyces avermitilis genes required for avermectin biosynthesis utilizing a novel integration vector. Gene 111:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madduri, K., and C. R. Hutchinson. 1995. Functional characterization and transcriptional analysis of a gene cluster governing early and late steps in daunorubicin biosynthesis in Streptomyces peucetius. J. Bacteriol. 177:3879-3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto, A., S. K. Hong, H. Ishizuka, S. Horinouchi, and T. Beppu. 1994. Phosphorylation of the AfsR protein involved in secondary metabolism in Streptomyces species by a eukaryotic-type protein kinase. Gene 146:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuno, K., Y. Yamada, C. K. Lee, and T. Nihira. 2004. Identification by gene deletion analysis of barB as a negative regulator controlling an early process of virginiamycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces virginiae. Arch. Microbiol. 181:52-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paget, M. S. B., L. Chamberlin, A. Atrih, S. J. Foster, and M. J. Buttner. 1999. Evidence that the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor σE is required for normal cell wall structure in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Bacteriol. 181:204-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pang, X., B. Aigle, J. M. Girardet, S. Mangenot, J. L. Pernodet, B. Decaris, and P. Leblond. 2004. Functional angucycline-like antibiotic gene cluster in the terminal inverted repeats of the Streptomyces ambofaciens linear chromosome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:575-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez-Llarena, F. J., P. Liras, A. Rodriguez-Garcia, and J. F. Martin. 1997. A regulatory gene (ccaR) required for cephamycin and clavulanic acid production in Streptomyces clavuligerus: amplification results in overproduction of both beta-lactam compounds. J. Bacteriol. 179:2053-2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinnert-Sindico, S., L. Ninet, J. Preud'homme, and C. Cosar. 1955. A new antibiotic spiramycin. Antibiot. Annu. 1954-1955:724-727. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raty, K., J. Kantola, A. Hautala, J. Hakala, K. Ylihonko, and P. Mantsala. 2002. Cloning and characterization of Streptomyces galilaeus aclacinomycins polyketide synthase (PKS) cluster. Gene 293:115-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rebets, Y., B. Ostash, A. Luzhetskyy, D. Hoffmeister, A. Brana, C. Mendez, J. A. Salas, A. Bechthold, and V. Fedorenko. 2003. Production of landomycins in Streptomyces globisporus 1912 and S. cyanogenus S136 is regulated by genes encoding putative transcriptional activators. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 222:149-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rost, B., and C. Sander. 1993. Prediction of protein secondary structure at better than 70% accuracy. J. Mol. Biol. 232:584-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 37.Sheldon, P. J., S. B. Busarow, and C. R. Hutchinson. 2002. Mapping the DNA-binding domain and target sequences of the Streptomyces peucetius daunorubicin biosynthesis regulatory protein, DnrI. Mol. Microbiol. 44:449-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stratigopoulos, G., and E. Cundliffe. 2002. Expression analysis of the tylosin-biosynthetic gene cluster: pivotal regulatory role of the tylQ product. Chem. Biol. 9:71-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stratigopoulos, G., A. R. Gandecha, and E. Cundliffe. 2002. Regulation of tylosin production and morphological differentiation in Streptomyces fradiae by TylP, a deduced gamma-butyrolactone receptor. Mol. Microbiol. 45:735-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stutzman-Engwall, K. J., S. L. Otten, and C. R. Hutchinson. 1992. Regulation of secondary metabolism in Streptomyces spp. and overproduction of daunorubicin in Streptomyces peucetius. J. Bacteriol. 174:144-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takano, E., H. C. Gramajo, E. Strauch, N. Andres, J. White, and M. J. Bibb. 1992. Transcriptional regulation of the redD transcriptional activator gene accounts for growth-phase-dependent production of the antibiotic undecylprodigiosin in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 6:2797-2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takano, E., M. Tao, F. Long, M. J. Bibb, L. Wang, W. Li, M. J. Buttner, Z. X. Deng, and K. F. Chater. 2003. A rare leucine codon in adpA is implicated in the morphological defect of bldA mutants of Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 50:475-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, L., and L. C. Vining. 2003. Control of growth, secondary metabolism and sporulation in Streptomyces venezuelae ISP5230 by jadW1, a member of the afsA family of gamma-butyrolactone regulatory genes. Microbiology 149:1991-2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White, J., and M. Bibb. 1997. bldA dependence of undecylprodigiosin production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) involves a pathway-specific regulatory cascade. J. Bacteriol. 179:627-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wietzorrek, A., and M. Bibb. 1997. A novel family of proteins that regulates antibiotic production in streptomycetes appears to contain an OmpR-like DNA-binding fold. Mol. Microbiol. 25:1181-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang, K., L. Han, J. He, L. Wang, and L. C. Vining. 2001. A repressor-response regulator gene pair controlling jadomycin B production in Streptomyces venezuelae ISP5230. Gene 279:165-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang, K., L. Han, and L. C. Vining. 1995. Regulation of jadomycin B production in Streptomyces venezuelae ISP5230: involvement of a repressor gene, jadR2. J. Bacteriol. 177:6111-6117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]