Abstract

We cloned the complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) of the heat shock cognate 70 (hsc70) gene of tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon). It was 2207 bp long and included a 1959-bp coding region, a 40-bp flanking region at the 5′ end, and a 208-bp flanking region at the 3′ end. The deduced, 652–amino acid sequence had a molecular mass of 71 481 Da and an estimated isoelectric point (pI) of 5.2. Based on phylogenetic analysis, the gene is clustered with the hsc70 proteins of invertebrates and vertebrates. In native gel electrophoresis, recombinant P monodon hsc70 expressed in an Escherichia coli system is tightly associated with carboxymethylated α-lactalbumin (CMLA), which indicates that hsc70 probably functions as a chaperone. In an in vitro adenosine triphosphatase assay, recombinant hsc70 hydrolyzed adenosine triphosphate to adenosine-5′-diphosphate and increased hydrolysis activity by binding to unfolded peptide, CMLA. In situ hybridization using an antisense riboprobe revealed that the hsc70 gene was active in most tissues of unstressed shrimp. The expression of hsc70 messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) in hemocytes increased 2- to 3-fold at the first hour after shrimp experienced heat shock and 0.5-hour recovery. Hsc70 mRNA decreased gradually to the background level. Cloning and characterizing the P monodon hsc70 gene is the first, crucial step in studying the relationship of heat shock proteins with the stress or immune responses of shrimp.

INTRODUCTION

A sudden increase in temperature and other types of environmental stresses induce the synthesis of a specific set of proteins called heat shock proteins (Hsps). The first description of a subset of cellular proteins in Drosophila induced by heat shock (Ritossa 1962) triggered extensive research on their function in stress tolerance in a variety of organisms. Hsps are grouped into 5 major families on the basis of their molecular size in kilodaltons (kDa): Hsp110, Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp60, and the low–molecular weight Hsp family. The Hsp70 family occurs in diverse organisms, and it is highly conserved among eukaryotes. Members of the Hsp70 family play an essential role in protein metabolism in both stressed and unstressed organisms. Hsp70 proteins are involved with de novo protein folding, membrane translocation, formation and disassembly of protein complexes, and degradation of misfolded proteins (Hartl 1996; Bukau and Horwich 1998; Kregel 2002).

Hsp70 family members are composed of 3 domains. The 44-kDa, N-terminal adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) domain binds and hydrolyses adenosine triphosphate (ATP). The variable 18-kDa, peptide-binding domain interacts with unfolded polypeptides, and the 10-kDa, C-terminal domain bears the highly conserved, EEVD terminal sequence present in all eukaryotic Hsp70 families (Flaherty et al 1990; Kiang and Tsokos 1998). Hsp70 family members also interact with a number of other proteins, promoting specific chaperoning functions (Santacruz et al 1997). Some hsp70 proteins are weakly expressed, at best, under normal conditions but are induced by heat and other stresses allowing cells to cope with acute stressor insults. The genes for these bona fide hsp70 proteins lack introns. The heat shock cognate 70 (hsc70) proteins are expressed constitutively. They play essential roles in protein metabolism under normal conditions. The genes for these proteins contain introns and are only slightly inducible, at best. Physiologically, hsc70 functions as a “housekeeping protein” or “professional chaperone.” It is involved with many cellular physiological processes. They include the folding of newly synthesized polypeptides, membrane translocation, formation and disassembly of protein complexes, and degradation of misfolded proteins (Hartl 1996; Bukau and Horwich 1998; Kiang and Tsokos 1998; Hartl and Hayar-Hartl 2002; Kregel 2002). Hsc70 even increases cell survival by restoring cellular homeostasis (Mallouk et al 1999). Additional members of the Hsp70 family include a mitochondrial form, hsp75, and a glucose-regulated protein known as Grp78, or heavy-chain binding proteins (Bip), that is located in the endoplasmic reticulum (Lindquist and Craig 1988; Kiang and Tsokos 1998).

The Hsc70 protein always associates with nascent polypeptide chains. It also forms a stable complex with unfolded proteins, such as reduced carboxymethylated α-lactalbumin (CMLA), a thermally unstable mutant of staphylococcal nuclease and apocytochrome c (Beckmann et al 1990; Palleros et al 1991; Sadis and Hightower 1992; Frydman et al 1994). Hsc70 has a high affinity for ATP but relatively weak intrinsic ATPase activity. The ATP hydrolysis activity of hsc70 can be stimulated by the other peptides, suggesting that the released energy is used to facilitate folding of the substrates. Thus, CMLA is used as a model protein to form a complex with hsc70 to identify the binding capacity in basal chaperone functions (Wang and Lee 1993; Hu and Wang 1996).

Penaeus monodon is native to the Western Pacific region and is a major species in Asian aquaculture. As previously reported, 2 expressed sequence tag (EST) homologues for the stress-related hsp70 gene were found in tiger shrimp (P monodon) and Pacific white shrimp (Lipopenaeus vannamei) (Tassanakajorn A, GenBank: BI78445; Gross et al 2001) and an EST homologue for the stress-related hsp60 gene was found in P monodon (Lehnert et al 1999). However, they were not characterized further, and their full-length complementary deoxyribonucleic acids (cDNA) were not obtained. In this study, we molecularly cloned and characterized the hsc70 gene in P monodon. The recombinant protein expressed in an Escherichia coli system is the first member of the Hsp70 family in shrimp. Using in situ hybridization, we compared the expression patterns of hsc70 in a variety of tissues from unstressed shrimp. Finally, we demonstrated that regulation of hsc70 expression in P monodon hemocytes was heat dependent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hemocyte collection and ribonucleic acid extraction

Shrimp hemolymph was withdrawn from the ventral sinus in the first abdominal segment using a 26-gauge hypodermic needle on a 1-mL syringe. The syringe was prefilled with anticoagulant solution (100 mM sodium citrate, 250 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 780 ± 20 mOsm/kg). Extra anticoagulant was added to make a 1: 4 volume ratio of hemolymph to anticoagulant. The mixture was centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 minutes to separate hemocytes from plasma. Hemocytes (106 cells) were immediately homogenized in 1 mL TRIzol reagent (Gibco BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The total ribonucleic acid (RNA) was extracted and further purified by using an RNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Gibco BRL).

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

First-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out using 2 μg of deoxyribonuclease-treated total RNA as template and incubating at 37°C for 30 minutes. Reverse transcription was performed using Moloney leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Super-Script Preamplification System, Gibco BRL). Degenerate oligonucleotide primers, 5′ GGGAT GGTCG GCAA(A/G) TGGCA (T/C)TTGG 3′ and 5′ AAGTG AGCCT TGTAC TT(C/G)CC 3′, were synthesized on the basis of the polynucleotide sequences of hsc70 from oyster (AF14466), coral (AF152004), and sea urchin (X61379). A 330-bp fragment was cloned using a set of these primers and 1 μg of hemocyte cDNA as a template. To this mixture we added 5 μL polymerase chain reaction (PCR) 10× buffer + Mg2+, 4 μL deoxynucleoside triphosphate MIX, and 1 μL Taq DNA polymerase (500 U/mL) KIT (Viogene, Taipei, Taiwan) according to the manufacturer's instructions, yielding a final volume of 50 μL. Thirty cycles of PCR amplification were performed. Each cycle consisted of denaturation for 40 seconds at 94°C, 45 seconds of annealing at 56°C, and 45 seconds of extension at 72°C. The last extension step was extended to 10 minutes at 72°C, followed by cooling to 4°C. Amplified DNA fragments were ligated to the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and transfected into E coli DH5α–competent cells. DNA sequencing, from both ends of 3 clones, was carried out using an ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with a DNA sequencer (ABI PRISM 377-96, Applied Biosystems).

Rapid amplification of cDNA ends

Full-length cDNA was obtained by using both 5′–rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) and 3′-RACE. The first-strand cDNA used in 5′-RACE was synthesized as described above. The 5′ end of the cDNA was tailed using a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (Boehringer Mannheim) and deoxyguanosine triphosphate. The resulting poly G–tailed cDNA was used to generate a double-stranded cDNA in the first PCR amplification in the presence of a universal primer, RAAPC (5′ GGCCA CGCGT CGACT AGTAC T(C)9 3′), and a P monodon–specific primer, R1 (5′ GACAA GGACG ATGTC GTGGA TC 3′). PCR was carried out as described above, except that the annealing temperature was 56°C. The first PCR product was diluted 50-fold with sterile, nanopure water. Then, 1 μL diluted PCR product was used as the template for the second PCR amplification (at 60°C), which used another universal primer, RAUAP (5′ GGCCA CGCGT CGACT AGTAC 3′) and a specific R2 (5′ CATCA CGGAG TGACT TCTCC 3′). Procedures for 3′-RACE were the same as for 5′-RACE, except that the first-strand cDNA was synthesized using a specific F1 (5′ GATCC ACGAC ATCGT CCTTG TC 3′) and an universal RAAPT (5′ GGCCA CGCGT CGACT AGTAC (T)18 3′) to generate a double-stranded cDNA, and the temperature was 32°C. For the nested PCR (at 56°C), 1 μL of the first PCR product (diluted 100-fold) was used as a template in the presence of a pair of primers: F2 (5′ GCCGG CGGTG TGATG ACTGC G 3′) and RAUAP. Amplified DNA fragments were subcloned, and 3 clones from each end were sequenced.

Sequence analysis

Nucleotides and deduced amino acid sequences were submitted to the National Center of Biotechnology International (NCBI, Bethesda, MD, USA) database for BLASTN and BLASTP searches of matches to known GenBank sequences. Multiple alignments were made with the ClustalW of Data Analysis in Molecular Biology and Evolution (DAMBE, version 4.0.75) software package (Xia 2000; Xia and Xie 2001). Using the alignment of amino acid sequences from different species, phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted using MEGA version 2.1 (Kumar et al 2001). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method (Nei and Kumar 2000).

Production of recombinant hsc70

To clone the hsc70 gene into the transfer vector, flanking NdeI and HindIII restriction sites (in bold) were introduced at the 5′ and 3′ ends by PCR mutagenesis with a sense primer (5′-CATAT GGCAA AGCCT-3′) and an antisense primer (5′-AAGCT TTAAT CGACT TCCTC-3′). The new hsc70 cDNA fragment was cloned into the pET-22b (+) transfer vector (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany), and then transformed into E coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RP-X–competent cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The transformation mixture was incubated with 600 mL Luria-Bertani medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 50 μg/ mL chloramphenicol for 16 to 20 hours at 37°C. After the culture reached an optical density of OD600 = 0.4, recombinant protein expression was induced with isopropyl β-thiogalactoside, at a final concentration of 0.4 mM. Incubation was continued for four more hours.

Purification of recombinant P monodon hsc70 protein and the N-terminus sequence

The induced bacterial culture was centrifuged at 5000 × g for 10 minutes, and the pellet was collected and stored overnight at −20°C. The E coli pellet was resuspended in 20 mL B-PER Bacterial Protein Extraction Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) by vortexing until the cell suspension was homogeneous. Purified inclusion bodies were dissolved with the same reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. The inclusion bodies were resuspended in 10 mL of 2 M urea in buffer A (5 mM MgCl, 125 mM NaCl, and 25 mM Tris base, pH 7.0) and incubated on ice for 10 minutes. After centrifugation at 12 000 × g for 10 minutes, the supernatant was stored at 4°C. These procedures were repeated using 4 and 6 M urea, and each supernatant was collected and pooled together. We added 1 M l-arginine (Sigma) to the supernatant and kept the mixture at 4°C for 10–15 minutes to renature the unfolded or misfolded recombinant protein. After centrifugation at 12 000 × g for 20 minutes, the supernatant was dialyzed in 5 L 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight to remove unnecessary urea. The dialyzed mixture was centrifuged at 12 000 × g for 20 minutes. Then, 10 mM MgCl2 was added to the supernatant before it was separated with a 2-mL adenosine-triphosphate agarose column (Sigma). Elution of the recombinant hsc70 was performed as previously described (Wang and Lee 1993). After collection, the fractions were dialyzed in 0.01 M PBS. The protein solution was concentrated with an Amicon Ultra-4 filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and stored at −80°C. Finally, the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the recombinant hsc70 was determined by Edman degradation using a Procise™ 490 protein sequencing system (Applied Biosystems).

Formation of the recombinant hsc70–CMLA complex

To determine whether a hsc70-CMLA complex formed, 3 μM purified recombinant P monodon hsc70 was mixed with 25 μM CMLA (excess) and 0.2 mM adenosine-5′-diphosphate in the buffer (75 mM KCl, 40 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid [HEPES], 10 mM dithiothreitol, and 4.5 mM Mg(CH3COO)2, pH 7.0) to achieve a final volume of 20 μL. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 45 minutes (Hu and Wang 1996). At the end of incubation, 5 μL of sample buffer (200 mM Tris, 25 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], 0.05% bromophenol blue, 50% glycerol, pH 7.0) were added. Finally, 12.5% native gel electrophoresis was conducted as described by Laemmli (1970), except that sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was omitted from the gels and the running buffer. The gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

ATPase assay

An ATP-hydrolysis assay was conducted according to the procedures of Tsai and Wang (1994). Briefly, 3 μg recombinant P monodon hsc70 protein was incubated at 37°C in 10 μL of buffer B (75 mM KCl, 40 mM HEPES, 4.5 mM Mg[CH3COO]2, pH 7.0) with, or without, 50 μM CMLA (Sigma). Then, 1 μCi [γ-32P]-ATP (3000 Ci/mmol; NEN/ Dupont, Boston, MA, USA) was added. At 0, 20, 40, and 60 minutes, 0.25 μL of the reaction mixture was withdrawn and spotted onto PEI-cellulose sheets (Millipore). The chromatograms were developed in 1.0 M formic acid–0.5 M LiCl. The amount of ATP hydrolyzed was quantified by PhosphoImager Analysis (Molecular Dynamics, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Tissue preparation for histology

Juvenile shrimp (3–5.8 g) were fixed in an RNA-friendly fixative containing 34.9% formalin, 40.7% ethanol, and 2.2% ammonium hydroxide (pH 6.5) (Hasson et al 1997). After dehydration, the samples were embedded in Paraplast, and 4-μm sections were cut and mounted on slides and stored at 4°C.

In situ nucleic acid hybridization of hsc70 messenger RNA in tissue sections

Riboprobes

A GEM-T Easy plasmid containing a region (1856–2175 nt) of P monodon hsc70 cDNA was used as a template for the preparation of the probes. Digoxigenin (DIG)-uridine triphosphate–labeled sense and antisense riboprobes were generated from linearized cDNA plasmids (5 μg) by in vitro transcription using the RNA-labeling kits T7 RNA polymerase and SP6 RNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim), respectively.

Hybridization

After deparaffinization and hydration, sections were treated with proteinase K (20 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at 37°C. The sections then were acetylated for 10 minutes at room temperature (using 0.25% acetic acid and 0.1 M triethanolamine, pH 8.0) and dehydrated in ethanol. Sections were incubated overnight at 43°C with hybridization solution containing 2.5 ng/slide of DIG-labeled hsc70 antisense probe. The hybridization solution consisted of 4× standard saline citrate (SSC), 50% formamide, 1× Denhardt's solution, 5% dextran sulfate, 0.5 mg/mL of salmon sperm DNA, and 0.25 mg/mL of yeast transfer RNA. The sections were washed at 43°C with 1× SSC for 30 minutes and then with 0.1× SSC for 15 minutes. The following steps were performed according to instructions for using Boehringer's DIG kit in alkaline phosphatase (AP) substrate for 1.5 hours at room temperature. The enzyme reaction was stopped by adding 100% methanol for 10 minutes. Then, the sections were counterstained with Bismarck Brown Y (Sigma) for 30 seconds. Finally, the sections were dehydrated, made transparent with graded ethanol and xylene, and mounted in GEL/ MOUNT™ (Biømeda Corp, Foster City, CA, USA). The sections were examined with a light microscope to determine the density of fixed, AP enzymatic reaction products (blue-black), and the signal density of each tissue was recorded as faintly positive (+), moderately positive (++), or very strongly positive (+++).

Northern blot analysis of hsc70 messenger RNA in P monodon hemocytes

Experimental animals

Healthy looking tiger shrimp (body length, 17.8 ± 1.5 cm; weight, 28.4 ± 1.64 g) were collected from the Tungkang Marine Laboratory located in southern Taiwan. Shrimp were kept in a plastic tank supplied with 1000 L of 26 ± 1°C, constantly flowing, recirculating seawater with 2% salinity. Shrimp were stocked at a density of 20–25 individuals per cubic meter. Twice a day, shrimp were fed commercial feed pellets equivalent to 5% of their body weight. Shrimp were conditioned for more than 1 month before receiving heat treatments.

Shrimp were transferred from water maintained at a controlled temperature of 26 ± 1°C to a tank containing seawater preheated to 37 ± 1°C. After 1 hour at 37 ± 1°C, the temperature of the water was rapidly decreased to 26 ± 1°C for 0.5 hours of recovery by draining and adding cool water (26 ± 1°C, flow rate: 30 L/min). Shrimp in the control group were transferred to another tank of water maintained at 26°C and kept at the same temperature by draining and adding water as in the test group. It was noticed that the water volume always was kept the same, both in heat stress and recovery treatment in the 2 groups. Hemolymph was withdrawn 0, 1, 2, 4, and 6 hours after treatment. For each sample, 10 shrimp were randomly selected from the experimental and control groups. With 5 people, hemolymph was withdrawn simultaneously from the first 5 shrimp of each sample and then, immediately afterward, from the remaining 5 shrimp.

DNA probes

A shrimp-specific hsc70 cDNA probe was prepared using PCR. Two primers were synthesized, F5 (5′-ATGGC AAAGG CACCT GCTGT CGG-3′) and R1. The primers corresponded to both ends of a 1012-bp fragment (nt 41– 1052). This fragment contained 2 signature motifs, the adenosine triphosphate-guanosine triphosphate (ATP-GTP)–binding site, potential bipartite nuclear localization signals, and the nonorganellar eukaryotic consensus region. A PCR DIG-labeled DNA probe synthesis kit (Boehringer Mannheim) was used to produce the DNA probe. The unincorporated DIG-labeled nucleotides were removed using a Nick column (Pharmacia, New York, NY, USA). The resulting 537-bp hemocytic actin DIG probe was synthesized as the hsc70 probe. Briefly, an oligo(dT)-primed cDNA corresponding to P monodon hemocytic actin was used as a template. The primers 5′ACGAG GGCTA CGCCC TGCCC C3′ and 5′GAGGC CAGGA TGGAG CCGCC G3′ were synthesized on the basis of the EST of tiger shrimp hemocytic actin (AW600757).

Northern blot

From each sample, 10 μg of total RNA was run electrophoretically on a denaturing formaldehyde-agarose gel (1.2%) in 1× formaldehyde gel-running buffer (20 mM 3[N-morpholino] propanesulfonic acid, 8 mM sodium acetate, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.0) at 50 V for 1 hour. Samples were compared with a RNA Millennium Marker (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA), which served as the control. Overnight, separated RNA was transferred with 20× SSC onto a nylon membrane (Millipore) by capillary blotting. The blotted membrane was cross-linked with 20 000 μJ by an UV-linker (Stratagene) before being subjected to hybridization. Each membrane was prehybridized for 2 hours at 60°C in hybridization solution (50% formamide, 5× SSC, 2% blocking reagent, 0.1% N-lauroylsarcosine, and 0.02% SDS). Hybridization was performed overnight at 60°C in buffer containing the hsc70-specific probe. After hybridization, the membranes were stripped with prewarmed dimethylformamide and reprobed with the actin cDNA probe. A total of 4 washes were performed at room temperature for 5 minutes. The first 2 washes were in 80 mL 2× SSC–0.1% SDS, and the final 2 washes were in 100 mL 1× SSC–0.1% SDS at 50°C for 15 minutes each. Detection was performed with a DIG Nucleic Acid Detection Kit (Boehringer Mannheim). Blots were quantified using a Personal Densitometer S1 (Molecular Dynamics), and the hsc70 transcript was normalized relative to the actin transcript.

RESULTS

Isolation of cDNA clones, sequencing and analysis of the deduced amino acid sequences

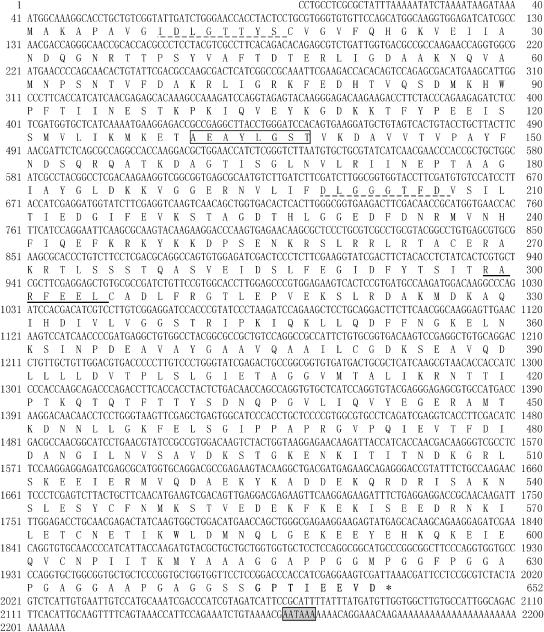

The full-length cDNA of P monodon heat shock hsc70 protein (GenBank accession number AF474375) was cloned. It is composed of 2207 bp, including a 1959-bp coding region and 40- and 208-bp flanking regions at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The most probable translation initiation codon, “ATG,” is located at nt 41 from the 5′ end, and the stop codon, “TAA,” is at nt 1997. A single polyadenylation site (AATAAA) was found at nt 2158–2163 (Fig 1). The guanine-cytosine content of the P monodon hsc70 gene was 0.566. The deduced amino acid sequence encoded a 652–amino acid protein with a calculated molecular mass of 71 481 Da and an isoelectric point (pI) of 5.21. Several general eukaryotic Hsp70 family motifs were identified on the deduced amino acid sequence: 2 signatures (IDLGTTYS, aa 9–16; DLGGGTFD, aa 199–206) and a putative ATP-GTP–binding site (AEAYLGST; aa 131– 138). Two additional specific motifs were found: the nonorganellar consensus motif (RARFEEL; aa 299–305) and the cytoplasmic Hsp70 carboxyl terminal region (GPTIEEVD; aa 649–652) (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence of Penaeus monodon hsc70 complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA). The nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the hsc70 protein and the predicted amino acid sequence deduced from the cDNA inserts are shown. Two signatures are underlined with dots, and the putative adenosine triphosphate-guanosine triphosphate (ATP-GTP)–binding site is boxed. The potential nonorganellar eukaryotic consensus motif is underlined, and the cytoplasmic motif carboxyl terminal region (GPTIEEVD) is in bold. The polyadenylation signal (AATAAA) is shown in a gray box, and the stop codon is marked with an asterisk

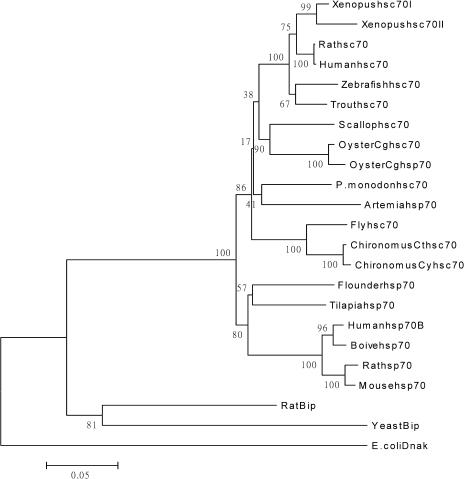

Relationship with other members of the Hsp70 family

A phylogenetic tree was constructed by analyzing the amino acid sequences of P monodon hsc70 and the hsc70, hsp70, and Bip from a variety of eukaryotic species. Twenty-three Hsp70 family members from 10 diverse genera were selected for analysis. P monodon hsc70 clustered with Artemia hsp70 on a unique branch of the tree. They clustered with other hsc70 from vertebrates, molluscs, and insects. The amino acid sequences of human, rat, Xenopus, trout, zebrafish, oyster, fly, chironomus, and P monodon hsc70 shared 83–99% identity. Human, rat, mouse, bovine, tilapia, and flounder hsp70 amino acid sequences shared 88–99% identity. The Bip and prokaryotic E coli DnaK sequences form their own unique branches (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationship of Penaeus monodon hsc70 amino acid sequence to other Hsp70 family members from a variety of species. Sequences used in the tree, followed by their GenBank accession number, were Xenopus hsc70I (AAB97092), Xenopus hsc70II (AAB41583), zebrafish hsc70 (AAB03704), trout hsc70 (AAB21658), human hsc70 (CAA68445), rat hsc70 (CAA68265), scallop hsc70 (AAS17724), oyster Cghsp70 (CAC83009), oyster Cghsc70 (CAC83683), P monodon hsc70 (AAQ05768), Artemia hsp70 (AAL27404), fly (AAC23392), chironomus Cthsc70 (AAN14525), chironomus Cyhsc70 (AAN14426), flounder hsp70 (BAA31697), tilapia hsp70 (CAA04673), mouse hsp70 (AAA59362), rat hsp70 (AAA17441), human hsp70B (NP005337), rat heavy-chain binding proteins (Bip) (AAA40817), yeast Bip (AAA08536), and Escherichia coli DnaK (BAB96589). The distance is the proportion of amino acid sites at which 2 sequences are different. Bootstrap values are given in percent

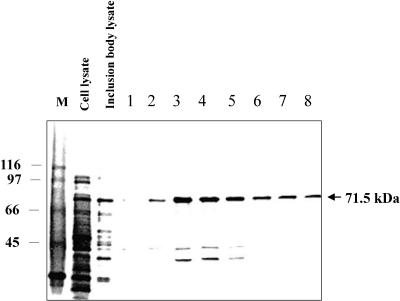

Recombinant P monodon hsc70

In this study, recombinant hsc70 was overproduced as shown in the whole-cell lysate (Fig 3, lane 1). Almost all overexpressed proteins are insoluble and form inclusion bodies (Fig 3, lane 2). After the ATP-agarose column step, essentially homogeneous hsc70 was collected from fractions 1–8 (Fig 3, lanes 3–10). Recombinant hsc70 migrates in the gel as a 71.5-kDa protein. Amino acid sequence analysis found that the N-terminus of recombinant hsc70 is AKAPA. This matches the corresponding, deduced P monodon hsc70 N-terminal amino acid sequence and is different from that of the E coli, 70-kDa hsp, DnaK.

Fig 3.

Purification of recombinant hsc70. In sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (12.5% acrylamide), each lane corresponds to a different purification step. M, molecular mass markers (in kDa, on left); lane 1, whole-cell lysate; lane 2, inclusion body lysate; lanes 3 to 10, fractions 1 to 8 were eluted from an adenosine triphosphate (ATP)–agarose column. Recombinant Penaeus monodon hsc70 migrates in the gel as a 71.5-kDa protein (arrow)

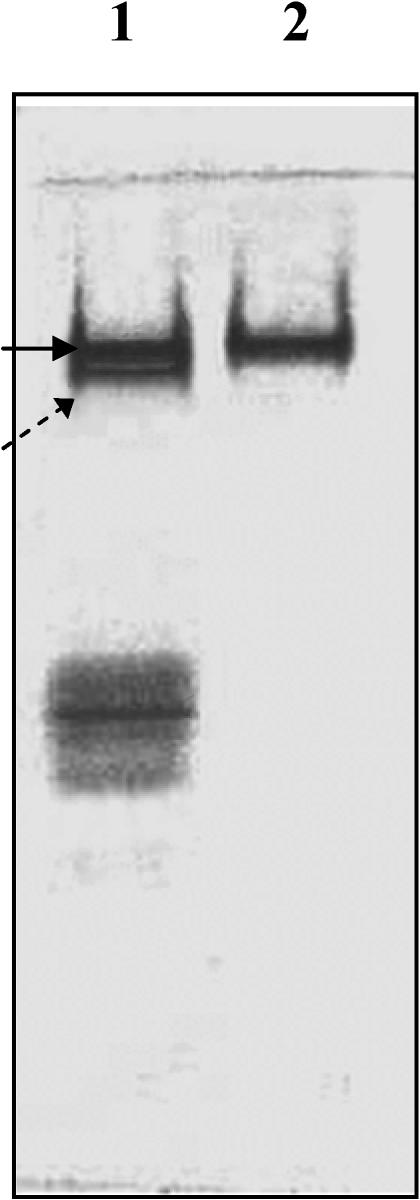

Formation of recombinant P monodon hsc70–CMLA complex

To assay for a tightly associated, recombinant P monodon hsc70–CMLA complex, the protein was incubated with CMLA and then resolved on native gel. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) shows that the top “two bands” in Figure 4, lane 1 emerge when hsc70 was mixed with CMLA (upper band was free hsc70 and the lower band was hsc70-CMLA complex). The other excess CMLA with its degraded proteins that cannot complex with recombinant hsc70 will be observed on the bottom band in lane 1 (Fig 4). Recombinant hsc70 only is in lane 2.

Fig 4.

Identification of the hsc70–carboxymethylated α-lactalbumin (CMLA) complex. Recombinant Penaeus monodon hsc70 (3 μM) was incubated with 50 μM CMLA and then separated by native gel electrophoresis. In the resolving gels, the concentration of acrylamide is 12.5%. Lane 1 has a mixture of CMLA and hsc70. The arrow points at the upper one of the top 2 bands is free hsc70 not yet bound to CMLA. The lower band is the tightly bound hsc70-CMLA complex (arrow with dots). The bottom band is excess CMLA and it's degraded products. Lane 2 has recombinant hsc70 only

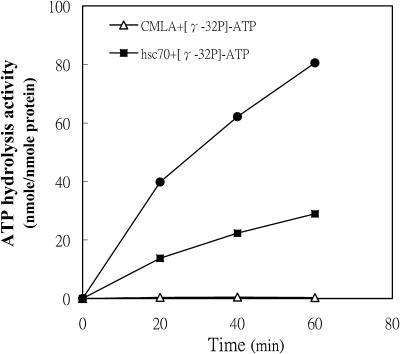

ATPase assay

The hydrolysis activity of ATP by recombinant P monodon hsc70 increased with incubation time and then formed a complex with CMLA. CMLA increased recombinant hsc70 ATP hydrolysis activity (Fig 5, top). The activity of recombinant hsc70, alone, was low and that of CMLA alone was very low (Fig 5, middle and bottom). After incubation for 60 minutes with 50 μM CMLA, hsc70 ATP hydrolysis activity was about 3.2-fold higher than that of hsc70 alone.

Fig 5.

The effect of hsc70 and CMLA on adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis. Recombinant hsc70 (3 μg) was incubated with or without 50 μM CMLA. To initiate the reaction, 0.2 mM [γ-32P]-ATP was added to the mixtures, in a total volume of 10 μL. Every 20 minutes, ATP hydrolysis was measured. CMLA alone was incapable of ATP hydrolysis (open triangles)

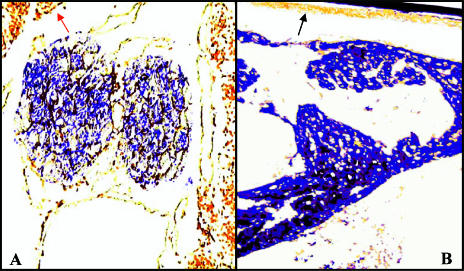

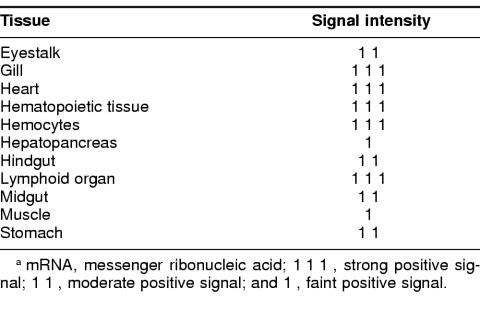

In situ nucleic acid hybridization

To determine the distribution of the hsc70 gene expression in different tissues, we used in situ nucleic acid hybridization to assess the basal levels of expression in unstressed tiger shrimp. A blue-black, positive signal was observed in nearly all shrimp tissues and organs, except for the epithelium (Fig 6B, bold arrow). Unexpectedly, the largest shrimp organ, the hepatopancreas, exhibited only a faint signal (Fig 6A, arrow). The strongest positive signals for hsc70 messenger RNA (mRNA) occurred in the gills, heart, hematopoietic tissue, hemocytes, and the lymphoid organ. Moderately positive signals for hsc70 mRNA were observed in the eyestalk, hindgut, midgut, and stomach (Table 1).

Fig 6.

In situ hybridization of shrimp hsc70 with antisense riboprobe. (A) Lymphoid organ and hepatopancreas (200×). (B) Heart (200×) of Penaeus monodon. The sections are slightly counterstained with Bismarck Brown Y. In (A), the red arrow points at the hepatopancreas, and in (B), the black arrow points at the epithelium. No positive signals were observed when a sense hsc70 riboprobe was used (data not shown)

Table 1.

Abundance of hsc70 mRNA in Penaeus monodon tissues as determined by in situ nucleic acid hybridizationa

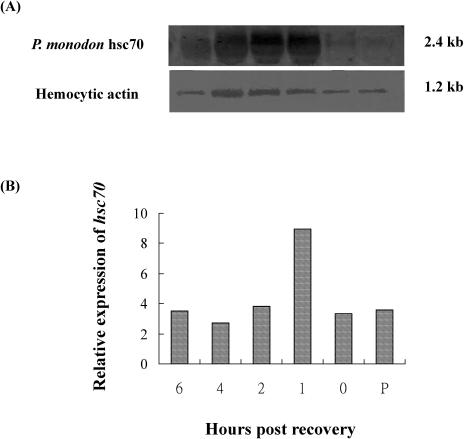

Northern blot analysis

To determine whether P monodon constitutive hsc70 was inducible, shrimp were also subjected to heat shock treatment. Hemocytes, the cells in which the gene was isolated, were used in this analysis. In tiger shrimp, heat shock treatment increased the amount of hsc70 mRNA transcript. A 2.4-kb band was found in shrimp hemocytes before treatment as well as 0, 1, 2, 4, and 6 hours after recovery. The signal was weak before heat treatment and after 24 hours (Fig 7, lane P and 0). Expression was greatest during the first hour after heat treatment and recovery. It gradually decreased to the pretreatment level at the next time point. Hsc70 was expressed constitutively and until the termination of the experiment (Fig 3). In the control group, no notable difference was found at each sampling time (data not shown).

Fig 7.

Northern blot analysis of ribonucleic acid (RNA) extracted from Penaeus monodon hemocytes. RNA (10 μg per lane) was isolated from the hemocytes of pretreated shrimp (lane P) and heat shocked shrimp 0, 1, 2, 4, and 6 hours after 0.5 hours of recovery. Total RNA was electrophoretically separated on a denaturing formaldehyde agarose gel (1.2%) and blotted onto a nylon membrane. (A) The upper blot was hybridized with the hsc70-specific complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) probe. The lower blot was hybridized with a hemocytic actin–specific probe, providing an internal control. (B) Expression of P monodon hsc70 relative to expression of the hemocytic actin gene

DISCUSSION

A full-length cDNA, containing a 1959-bp coding region with 40- and 208-bp flanking regions at each end, was cloned. The GPKH motif characteristic of the prokaryotic Hsp70 family was not present between amino acids 295– 296, excluding the possibility of false prokaryotic cloning (Karlin and Brocchieri 1998). The deduced amino acid sequence of shrimp hsc70 was highly homologous with the amino acid sequences of Artemia, rainbow trout, humans, rats, and zebrafish hsc70. Two signature (I/V-D-L-G-T-T-x-S and D-L/F-G-G-G-T-F-D) sequences and the ATP-GTP–binding motif functional domain (A-E-A-Y-L-G-K/ R-T) characteristic of the eukaryotic Hsp70 family were found in the shrimp hsc70 sequence. Thus, the gene in this study clearly belongs to the eukaryotic Hsp70 family. Putative bipartite nuclear localization signals (K-K and R-R-L-R-T) were identified at aa 250–251 and aa 261–265 of the P monodon hsc70 primary sequence. The signal, characterized by an abundance of the basic amino acids lysine and arginine, is needed for the selective translocation of hsc70 protein into the nucleus (Knowlton and Salfity 1996). In addition, P monodon hsc70 included a nonorganellar stress protein motif (R-A-R-F-E-E-L; aa 299–305), tetrapeptide GGXP repeats (where X is any aliphatic residue; aa 615–638), and the cytosolic-cytoplasmic Hsp70 family carboxyl terminal region (G-P-T-I/V-E-E-V-D-stop codon; aa 595–652), which affects binding of certain cofactors of the hsc70 protein (Demand et al 1998). These motifs account for the localization of our hsc70 in the cell cytosol and cytoplasm (Boorstein et al 1994; Gupta and Singh 1994; Rensing and Maier 1994). Based on the sequence analyses presented above, the P monodon hsc70 is a member of the eukaryotic cytosolic-cytoplasmic Hsp70 family (Demand et al 1998; Vayssier et al 1999).

P monodon hsc70 clustered with the hsc70 amino acid sequences of vertebrates, arthopods, and molluscs to form a distinct clade. P monodon hsc70 is not as closely related to other eukaryotic hsp70 (whose genes lack introns), Bip in the Hsp70 family, and prokaryotic hsp70-equivalent DnaK. Phylogenetically, P monodon hsc70 is most closely related to brine shrimp hsp70 (Artemia franciscana). Both belong to a group of eukaryotic hsc70 whose genes contain introns (Fig 2). Unfortunately, the brine shrimp hsp70 amino acid sequence in GenBank is incomplete in the C-terminal region. Therefore, our comparison of P monodon and A franciscana sequences is preliminary and inconclusive. However, the N-terminal 644 amino acids of P monodon hsc70 and Artemia hsp70 exhibited 86% identity (data not shown). Typically, eukaryotic Hsp70 family members localized in the cytoplasm share approximately 50% identity with prokaryotic hsp70. Among eukaryotic subgroups, cytoplasmic members share at least 71% identity (Boorstein 1994). A detailed comparison of the amino acid sequence of P monodon hsc70 with the sequences of the other Hsp70 family members currently available in the database found highly conserved regions in the N-terminal part of the protein. Conservation of the amino acid sequence is expected decrease toward the C-terminal end of the protein.

Eukaryotic recombinant hsc70 produced by the E coli expression system usually is in the soluble form (Wang and Lee 1993; Boutet et al 2003). However, recombinant P monodon hsc70 was present in an insoluble form (inclusion bodies). Hsc70 protein (0.4 to 0.6 mg) was obtained from 0.6 L of cell culture. Insoluble recombinant hsc70 required a longer extraction time than the soluble hsc70, so that it sometimes was degraded from 71.5-kDa to 44-and 27.5-kDa fragments when separated by SDS-PAGE gel (Fig 3, lanes 5–7). Therefore, for biochemical assays and antibody production, we always purified the complete recombinant hsc70 by dialyzing with a membrane tube (MWCO: 5000). The five N-terminal amino acids were sequenced. They were A-K-A-P-A. They matched the deduced P monodon hsc70 sequence and proved that the sequence was eukaryotic. The N-terminal amino acids for the E coli sequence are G-K-I-I-G. The recombinant P monodon hsc70 was produced by a prokaryotic (E coli) expression system. Thus, the first amino acid (methionine) of the protein is not translated (Wang and Lee 1993).

Using native gel electrophoresis, we verified that recombinant P monodon hsc70 formed a tight complex with CMLA. The two closest bands were unbound hsc70 (upper) and hsc70-CMLA complex (lower) (Fig 4, top 2 bands in lane 1). The data demonstrated that the mobility of the tightly associated hsc70-CMLA complex is greater than that of hsc70 alone as given in a previous report (Hu and Wang 1996). In addition, we showed that recombinant hsc70 ATP hydrolytic activity was stimulated by the unfolded peptide, CMLA. This provides further evidence that recombinant P monodon hsc70 protein functions as a chaperone (Gething and Sambrook 1992; Benaroudj et al 1996; Hu and Wang 1996; Takeda and McKay 1996; Leng et al 1998; Kampinga et al 2003).

Using an in situ hybridization assay, we found that hsc70 mRNA transcripts were present in all P monodon tissues, except the epithelium. The level of hsc70 expression varied in different tissues of P monodon (Table 1). Differential expression of hsc70 also has been reported in the tissues of rats, Xenopus, and carp (O'Malley et al 1985; Ali et al 1996, 2003). The exact reasons and mechanisms for this differential expression are not well understood.

In this study, we demonstrated that hsc70 increased significantly in the hemocytes of P monodon after heat shock treatment (Fig 7). In previous studies, heat shock treatment did not increase hsc70 expression in most species (Kiang and Tsokos 1998). However, an increasing number of studies have demonstrated that heat shock treatment does increase mRNA levels severalfold (<20-fold) in a variety of cell types, including oyster hemocytes (Gourdon et al 2000), human peripheral blood monocytes (Jacquier-Sarlin et al 1995), human lymphocytes (Hansen et al 1991), and human HeLa cells (O'Malley et al 1985). Similarly, expressions of several members of the multigenic Hsp70 family that are expressed constitutively in unstressed animals increase severalfold in stressed animals, indicating that they are inducible (Taviara et al 1996). Based on our results and those from other studies, shrimp hemocytes, which are similar to immune cells, provide vital cellular protection against stress.

Cloning and characterization of the hsc70 and other stress protein genes in P monodon provides a tool for investigating the immune and stress-related responses in shrimp. We are now in the process of cloning and sequencing the hsp70 (the major inducible form). Based on differences between hsp70 and hsc70, we can develop the transgenic techniques in marine crustaceans. In addition, the conserved amino acid sequences of these stress proteins provide invaluable information about the evolution of the immune system in the shrimp and other invertebrates.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Dr C Wang, Institute of Molecular Biology, Academia Sinica, for kindly providing guidance and facilities. We also are very thankful to Prof Huai-Jen Tsai, Institute of Fisheries Science, National Taiwan University for his helpful guidance. We are grateful to Prof C.W. Hu, Institute of Marine Biotechnology, National Taiwan Ocean University, for valuable comments and for critically reviewing the manuscript. The Council of Agriculture, Republic of China, financially supported this project under grant 92AS-4.2.3-FD-Z3.

REFERENCES

- Ali A, Salter-Cid L, Flajnik MF, Heikkila JJ. Isolation and characterization of a cDNA encoding a Xenopus 70kDa heat shock cognate protein, Hsc70. I. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;113:681–687. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(95)02081-0.1096-4959(1996)113<0681:IACOAC>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali KS, Dorgai L, Abraham M, Hermesz E. Tissue-and stressor-specific differential expression of two hsc70 genes in carp. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;307:503–509. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01206-3.0006-291X(2003)307<0503:TSDEOT>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann RP, Mizzen LA, Welch WJ. Interaction of Hsp 70 with newly synthesized proteins: implications for protein folding and assembly. Science. 1990;248:850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.2188360.0193-4511(1990)248<0850:IOHWNS>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benaroudj N, Triniolles F, Ladjimi MM. Effect of nucleotides, peptides, and unfolded proteins on the self-association of the molecular chaperone HSC70. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18471–18476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18471.0021-9258(1996)271<18471:EONPAU>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boorstein WR, Ziegelhoffer T, Craig EA. Molecular evolution of the Hsp70 multigene family. J Mol Evol. 1994;38:1–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00175490.0022-2844(1994)038<0001:MEOTHM>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutet I, Tanguy A, Rousseau S, Auffret M, Moraga D. Molecular identification and expression of heat shock cognate 70 (hsc70) and heat shock protein 70 (hsp70) genes in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2003;8:76–85. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2003)8<76:miaeoh>2.0.co;2.1466-1268(2003)008<0076:MIAEOH>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau B, Horwich AL. The Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone machines. Cell. 1998;92:351–366. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80928-9.0092-8674(1998)092<0351:THAHCM>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demand J, Luders J, Hohfeld J. The carboxy-terminal domain of Hsc70 provides binding sites for a distinct set of chaperone cofactors. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2023–2028. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2023.0270-7306(1998)018<2023:TCDOHP>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty KM, DeLuca-Flaherty C, McKay DB. Three-dimensional structure of the ATPase fragment of a 70 K heat-shock cognate protein. Nature. 1990;346:623–638. doi: 10.1038/346623a0.0028-0836(1990)346<0623:TSOTAF>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman J, Nimmesgern E, Ohtsuka K, Hartl FU. Folding of nascent polypeptide chains in a high molecular mass assembly with molecular chaperones. Nature. 1994;370:111–117. doi: 10.1038/370111a0.0028-0836(1994)370<0111:FONPCI>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gething MJ, Sambrook J. Protein folding in the cell. Nature. 1992;355:33–45. doi: 10.1038/355033a0.0028-0836(1992)355<0033:PFITC>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourdon I, Gricourt L, Kellner K, Roch P, Escoubas JM. Characterization of a cDNA encoding a 72 kDa heat shock cognate protein (Hsc72) from the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. DNA Seq. 2000;11:265–270. doi: 10.3109/10425170009033241.1042-5179(2000)011<0265:COACEA>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross PS, Barlettt TC, Browdy RW, Chapman RW, Warr GW. Immune gene discovery by expressed sequence tag analysis of haemocytes and hepatopancreas in the Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, and the Atlantic white shrimp, L. setiferus. Dev Comp Immunol. 2001;25:565–577. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(01)00018-0.0145-305X(2001)025<0565:IGDBES>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RS, Singh B. Phylogenetic analysis of 70 kD heat shock protein sequences suggests a chimeric origin for the eukaryotic cell nucleus. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1104–1114. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00249-9.0960-9822(1994)004<1104:PAOKHS>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen LK, Houchins JP, O'Leary JJ. Differential regulation of HSC70, HSP70, HSP90 alpha, and HSP90 beta mRNA expression by mitogen activation and heat shock in human lymphocytes. Exp Cell Res. 1991;192:587–596. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90080-e.0014-4827(1991)192<0587:DROHHH>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature. 1996;381:571–579. doi: 10.1038/381571a0.0028-0836(1996)381<0571:MCICPF>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU, Hayar-Hartl M. Complex environment of nascent chain to folded protein. Science. 2002;295:1852–1858. doi: 10.1126/science.1068408.0193-4511(2002)295<1852:CEONCT>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson KW, Hasson J, Aubert H, Redman RM, Lightner DV. A new RNA-friendly fixative for the preservation of penaeid shrimp samples for virological detection using cDNA genomic probes. J Virol Methods. 1997;66:227–236. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(97)00066-9.0166-0934(1997)066<0227:ANRFFT>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu SM, Wang C. Involvement of the 10-kDa C-terminal fragment of hsc70 in complexing with unfolded protein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;332:163–169. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0328.0003-9861(1996)332<0163:IOTKCF>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquier-Sarlin MR, Jornot L, Polla BS. Differential expression and regulation of hsp70 and hsp90 by phorbol esters and heat shock. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14094–14099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.14094.0021-9258(1995)270<14094:DEAROH>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampinga HH, Kanon B, Salomons FA, Kabakov AE, Patterson C. Overexpression of the cochaperone CHIP enhances Hsp70-dependent folding activity in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4948–4958. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4948-4958.2003.0270-7306(2003)023<4948:OOTCCE>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin S, Brocchieri L. Heat shock protein 70 family: multiple sequence comparisons, function, and evolution. J Mol Evol. 1998;47:565–577. doi: 10.1007/pl00006413.0022-2844(1998)047<0565:HSPFMS>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang JG, Tsokos GC. Heat shock protein 70 kDa: molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;80:183–201. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00028-x.0163-7258(1998)080<0183:HSPKMB>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton AA, Salfity M. Nuclear localization and the heat shock proteins. J Biosci. 1996;21:123–132.0250-5991(1996)021<0123:NLATHS>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Kregel KC. Heat shock proteins: modifying factors in physiological stress responses and acquired thermotolerance. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:2177–2186. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01267.2001.8750-7587(2002)092<2177:HSPMFI>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Tamura K, Jakobsen IB, Nei M. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1244–1245. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1244.1367-4803(2001)017<1244:MMEGAS>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0.0028-0836(1970)227<0680:COSPDT>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert SA, Wilson KJ, Byrne K, Moore SS. Tissue-specific expressed sequence tags from the black tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 1999;1:465–476. doi: 10.1007/pl00011803.1436-2228(1999)001<0465:TESTFT>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng CH, Brodsky JL, Wang C. Isolation and characterization of a DnaJ-like protein in rats: the C-terminal 10-kDa domain of hsc70 is not essential for stimulating the ATP-hydrolytic activity of hsc70 by a DnaJ-like protein. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1186–1194. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070513.0961-8368(1998)007<1186:IACOAD>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S, Craig EA. The heat-shock proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1988;22:631–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.003215.0066-4197(1988)022<0631:THP>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallouk Y, Vayssier-Taussat M, Bonventre JV, Polla BS. Heat shock protein 70 and ATP as partners in cell homeostasis (Review) Int J Mol Med. 1999;4:463–474. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.4.5.463.1107-3756(1999)004<0463:HSPAAA>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Kumar S 2000 Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley K, Mauron A, Barchas JD, Kedes L. Constitutively expressed rat mRNA encoding a 70-kilodalton heat shock-like protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:3476–3483. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3476.0270-7306(1985)005<3476:CERMEA>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palleros DR, Welch WJ, Fink AL. Interaction of hsp70 with unfolded proteins: effects of temperature and nucleotides on the kinetics of binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5719–5723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5719.0027-8424(1991)088<5719:IOHWUP>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensing SA, Maier UG. Phylogenetic analysis of the stress-70 protein family. J Mol Evol. 1994;39:80–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00178252.0022-2844(1994)039<0080:PAOTSP>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritossa E. A new puffing pattern induced by heat shock and DNP in Drosophila. Experientia. 1962;18:571–573.0014-4754(1962)018<0571:ANPPIB>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Sadis S, Hightower LE. Unfolded proteins stimulate molecular chaperone Hsc70 ATPase by accelerating ADP/ATP exchange. Biochemistry. 1992;31:9406–9412. doi: 10.1021/bi00154a012.0006-2960(1992)031<9406:UPSMCH>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santacruz H, Vriz S, Angelier N. Molecular characterization of a heat shock cognate cDNA of zebrafish, hsc70, and developmental expression of the corresponding transcripts. Dev Genet. 1997;21:223–233. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1997)21:3<223::AID-DVG5>3.0.CO;2-9.0192-253X(1997)021<0223:MCOAHS>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S, McKay DB. Kinetics of peptide binding to the bovine 70 kDa heat shock cognate protein, a molecular chaperone. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4636–4644. doi: 10.1021/bi952903o.0006-2960(1996)035<4636:KOPBTT>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taviara M, Gabriele T, Kola I, Anderson RL. A hitchhiker's guide to the human Hsp70 family. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1996;1:23–28. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1996)001<0023:ahsgtt>2.3.co;2.1466-1268(1996)001<0023:AHGTTH>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MY, Wang C. Uncoupling of peptide-stimulated ATPase and clathrin-uncoating activity in deletion mutant of hsc70. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5958–5962.0021-9258(1994)269<5958:UOPAAC>2.0.CO;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vayssier M, Le Guerhier F, and Fabien JF. et al. 1999 Cloning and analysis of a Trichinella britovi gene encoding a cytoplasmic heat shock protein of 72 kDa. Parasitology. 119:81–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Lee MR. High-level expression of soluble rat hsc70 in Escherichia coli: purification and characterization of the cloned enzyme. Biochem J. 1993;294:69–77. doi: 10.1042/bj2940069.0264-6021(1993)294<0069:HEOSRH>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X 2000 Data Analysis in Molecular Biology and Evolution. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Xia X, Xie Z. DAMBE: data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. J Hered. 2001;92:371–373. doi: 10.1093/jhered/92.4.371.0022-1503(2001)092<0371:DDAIMB>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]