ABSTRACT

Arthrobacter phage Ascela was isolated in North Georgia. Its genome is 44,192 bp with 71 open reading frames and a GC content of 67.4%. It shares 99.29% nucleotide identity with Arthrobacter phage Iter. Actinobacteriophages that share over 50% nucleotide identity are sorted into clusters, with Ascela in cluster AZ and subcluster AZ1.

KEYWORDS: bacteriophages, bacteriophage genetics, Arthrobacter

ANNOUNCEMENT

There is a growing concern about antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which could be addressed by phage therapy. The discovery and characterization of bacteriophage are important because they could be used for treatments of bacterial infections. Here, we present the Arthrobacter phage Ascela, isolated using a Science Education Alliance–Phage Hunters Advancing Genomics and Evolutionary Science protocol (1).

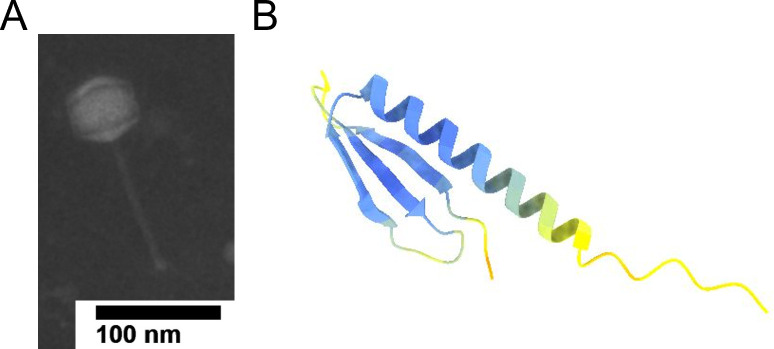

Ascela was isolated from shallow, lake-side soil collected in Dahlonega, Georgia (34.551799˚N, 83.966918˚W) in 2021. Arthrobacter globiformis B-2979 was used for Ascela’s isolation from the environmental sample. Briefly, LB liquid medium was added to soil, incubated at 30°C for 24 hours, and filtered using a 0.22-µm filter. Phage presence was confirmed and purified via standard plaque assay. After three rounds of purification, phages were amplified to a high titer to extract phage genomic DNA for sequencing (2). Electron microscopy using phosphotungstic acid as a negative stain identified Ascela as having siphovirus morphology with a capsid and tail measuring 45.6 nm in diameter and 113.5 nm in length, respectively (Fig. 1A). Ascela’s plaques are regularly 3 mm in diameter with distinct margins, but plaques with other characteristics were also observed. Actinobacteriophages that share over 50% nucleotide identity are sorted into clusters and subclusters where appropriate (3, 4). Ascela was sorted into cluster AZ and further into subcluster AZ1.

Fig 1.

(A) Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of Ascela. TEM images were obtained using a JEM-1011 TEM (JOEL, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) at the University of Georgia Electron Microscope laboratory. (B) Structure prediction of Ascela ORF59. Potential protein tertiary structure was predicted using AlphaFold (5).

Phage genomic DNA was extracted from Ascela lysate with a Wizard DNA extraction kit (Promega) per the manufacturer’s instructions. An NEB Ultra II Library Kit with v3 Reagents and 150-base single-end reads was used to assemble a sequencing library. Ascela was run using Illumina MiSeq sequencing. Ascela’s coverage was 249× with no Sanger finishing reactions required. These raw reads were assembled using Newbler v2.9 (Rosche) and Consed version June 2022 (6). The resulting single phage contig was checked for completeness, accuracy, and phage genomic termini using Consed v29 as previously described.

The genome was annotated using GeneMark v3.25 (7), NCBI BLAST v2.13.0, Glimmer v3.02, HHpred v3.2.0 (8, 9), ARAGORN v1.2.38 (10, 11), and Phamerator (5). Default parameters were used for all software. Hits with E values of 10e-10 or less were considered acceptable. Phamerator and GeneMark indicate that Ascela has 71 open reading frames (ORFs), and functions were able to be predicted for 34 of them. All genes are transcribed in the forward direction except for genes 38 and 50, which are transcribed in the reverse direction. Ascela is predicted to be a temperate phage, as a predicted serine integrase (ORF51) was identified. A phamily was determined using Phamerator by using “pairwise comparisons to generate gene relationships” (5). Ascela has 3′ sticky ends with an 11-bp overhang. Ascela is most genetically similar to Iter (GenBank accession no. ON208833), having 99.29% nucleotide identity via BLAST alignment. There is a single gene insertion in Ascela’s genome at ORF59 with no known function able to be called. The structure predicted for ORF59 has a single alpha helix 24 amino acids long at the C terminus and a single beta sheet at the N terminus as predicted by Alphafold (12, 13) (Fig. 1B).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was conducted as part of the Science Education Alliance–Phage Hunters Advancing Genomics and Evolutionary Science (SEA-PHAGES) program (3), supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI).

Funding was provided in part by the UNG College of Science and Mathematics professional development grant.

We thank John Shields and Mary Ard at UGA Georgia Electron Microscopy for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging support. We also thank Debbie Jacobs-Sera from SEA-PHAGES for her time and efforts spent in QC and review.

We thank NC State Genomic Sciences Laboratory for sequencing the genome.

Contributor Information

Alison E. Kanak, Email: aekanak@ung.edu.

Kenneth M. Stedman, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon, USA

DATA AVAILABILITY

Information on Ascela’s genome can be found in GenBank under accession no. OQ709218. Sequencing reads are part of the Sequence Read Archive with accession no. SRX20165771 under BioProject accession no. PRJNA488469.

REFERENCES

- 1. Russell DA. 2018. Sequencing, assembling, and finishing complete bacteriophage genomes. Methods Mol Biol 1681:109–125. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7343-9_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Poxleitner M PW, Jacobs-Sera D, Sivanathan V, Hatfull G. 2018. Protocol 6.2. Howard Hughes Medical Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hanauer DI, Graham MJ, SEA-PHAGES, Betancur L, Bobrownicki A, Cresawn SG, Garlena RA, Jacobs-Sera D, Kaufmann N, Pope WH, Russell DA, Jacobs WR, Sivanathan V, Asai DJ, Hatfull GF. 2017. An inclusive Research Education Community (iREC): impact of the SEA-PHAGES program on research outcomes and student learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:13531–13536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718188115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pope WH, Mavrich TN, Garlena RA, Guerrero-Bustamante CA, Jacobs-Sera D, Montgomery MT, Russell DA, Warner MH, et al. 2017. Bacteriophages of Gordonia spp. display a spectrum of diversity and genetic relationships. mBio 8. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01069-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cresawn SG, Bogel M, Day N, Jacobs-Sera D, Hendrix RW, Hatfull GF. 2011. Phamerator: a bioinformatic tool for comparative bacteriophage genomics. BMC Bioinformatics 12:395. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gordon D, Green P. 2013. Consed: a graphical editor for next-generation sequencing. Bioinformatics 29:2936–2937. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Delcher AL, Bratke KA, Powers EC, Salzberg SL. 2007. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with glimmer. Bioinformatics 23:673–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, Studer G, Tauriello G, Gumienny R, Heer FT, de Beer TAP, Rempfer C, Bordoli L, Lepore R, Schwede T. 2018. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 46:W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Söding J, Biegert A, Lupas AN. 2005. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 33:W244–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bienert S, Waterhouse A, de Beer TA, Tauriello G, Studer G, Bordoli L, Schwede T. 2017. The SWISS-MODEL repository-new features and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D313–D319. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laslett D, Canback B. 2004. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 32:11–16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, Tunyasuvunakool K, Bates R, Žídek A, Potapenko A, et al. 2021. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with Alphafold. Nature 596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mirdita M, Schütze K, Moriwaki Y, Heo L, Ovchinnikov S, Steinegger M. 2022. Colabfold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat Methods 19:679–682. doi: 10.1038/s41592-022-01488-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Information on Ascela’s genome can be found in GenBank under accession no. OQ709218. Sequencing reads are part of the Sequence Read Archive with accession no. SRX20165771 under BioProject accession no. PRJNA488469.