Abstract

Although heat shock proteins (Hsps) are primarily considered as being intracellular, this study identified the presence of Hsp72 in plasma from female Holstein-Friesian dairy cattle. Plasma samples were collected from the same animals at different ages and on different days after calving and accordingly divided into 5 age classes. The age classes were calves less than 235 days of age, young heifers between 235 and 305 days of age, older heifers between 305 and 560 days of age, cows early in lactation, and cows later in lactation. For a subsample of animals within each age class, replicate plasma samples were collected from 1 to 7 days apart to test whether the Hsp72 concentration levels are repeatable on this shorter timescale. Hsp72 was observed in plasma samples from animals of all 5 age classes. For animals with blood samples taken a few days apart, the repeatability (within age class) of the Hsp72 concentration was 0.52 ± 0.06. Age and days from calving significantly affected the Hsp72 concentration level. The highest Hsp72 level was observed in older heifers (305–560 days of age). The repeatability of Hsp72 concentrations across age classes within animal was 0.22 ± 0.06. High environmental sensitivity and negative genetic associations between production and health traits in this high-producing breed have been documented earlier. Hsp72 is believed to be strictly stress inducible, and the finding of Hsp72 in plasma indicates that even apparently healthy individuals may experience extrinsic or intrinsic stress (or both).

INTRODUCTION

Genetic selection has increased the production levels in livestock animals considerably. However, intense selection for specific traits has had some negative consequences in the form of behavioral, physiological, and immunological problems (reviewed in Rauw et al 1998). High-producing animals seem to be more sensitive to environmental changes (Nielsen and Andersen 1987; Kolmodin et al 2002). Another negative side effect of modern animal breeding is that the effective population sizes within some breeds are low, possibly leading to some degree of inbreeding depression (Smith et al 1998). This indicates that livestock animals may experience both intrinsic and extrinsic stress and that the homeostatic balance of the animals is occasionally at risk.

Heat shock proteins are a subgroup of molecular chaperones. They are classified into 5 families according to their molecular weight (Hsp100, Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp60, as well as the family of the small Hsps). They are among the most conserved and ubiquitous known proteins, highlighting their important function (Lindquist 1986). In unstressed cells Hsps act in successful folding, assembly, intracellular localization, secretion, regulation, and degradation of other proteins. Under conditions in which protein folding is perturbed or proteins begin to unfold and denature, Hsps assist in refolding, protecting cellular systems against protein damage, solubilizing aggregates, sequestering overloaded and damaged proteins into larger aggregates, and targeting damaged proteins into the degradation machinery (Gething and Sambrook 1992; Parsell and Lindquist 1993; Hartl 1996).

One of the most important and most studied Hsp families is Hsp70, which can represent up to 1% of the total cellular protein content under stressful conditions (Rothman 1989; Welch 1992). In bovines Hsp72 has been believed to be absent under nonstressful conditions and is therefore often referred to as the inducible form of the Hsp70 family (Welch 1992). However, recent investigations have shown that Hsp72 is also present at a low level in human cells and serum under apparently nonstressful conditions (Pockley et al 1998; Walsh et al 2001).

Hsps are typically regarded as intracellular proteins (Welch 1992). However, studies on humans and pigs have shown that Hsp70 family members are released from cells into the peripheral circulation system (Roma-Figueroa et al 1997; Pockley et al 1998; Wright et al 2000; Walsh et al 2001). The physiological basis for such a release is currently unknown. However, the recent identification of Hsp60 and Hsp70 family members in the serum of nonstressed individuals may suggest a fundamental role in physiological and immunological mechanisms by prevention or protection during pathophysiological processes (Welch 1992; Pockley et al 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001; Wright et al 2000).

It is known from several species, including mammals, that Hsps are involved in improved resistance toward stress and disease (reviewed in Favatier et al 1997; Feder and Hofmann 1999; Sørensen et al 2003). There is evidence suggesting that extreme selection for increased milk yield in cattle can result in physiological stress. In this study we investigated the Hsp72 concentration in plasma sampled from female Danish Holstein-Friesian dairy cattle without clinical disease symptoms. The objectives of the study were, first, to investigate whether Hsp72 was present in plasma samples from juvenile bovines collected at 3 ages and after parturition at 2 stages of lactation (days from calving) and, second, to test whether measures of Hsp72 concentrations are repeatable in plasma samples collected a few days apart and at different ages and lactation stages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical material

Hsp72 concentrations were determined in plasma samples from healthy female dairy cattle of the Holstein-Friesian breed at different ages and days from first calving. The animals in this study originated from a breeding experiment performed at the Skølvad breeding station in Denmark. Blood samples from 71 females were divided into 5 age classes according to age and days from first calving (Table 1). Thirty-one of the 71 animals had blood samples taken from all 5 age classes, whereas the remaining 40 animals had blood samples taken from 4 of the 5 age classes. For a number of animals from each age class (see Table 1), 2 blood samples (samples 1 and 2) were taken between 1 and 7 days apart (4.29 ± 0.15 days). Blood samples were drawn from an intravenous catheter into heparin and chilled on ice, and the plasma was separated by centrifugation (4000 × g, 4°C, 10 minutes) and stored frozen (−20°C) until assayed for Hsp72.

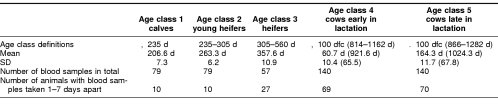

Table 1.

Age class definitions and number of blood samples taken. Numbers are average age (d) or days from first calving (dfc) ± SE

Protein expression

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (#EKS-700, StressGen Biotechnologies, Victoria, Canada) was used to determine the relative concentration of Hsp72 in plasma samples (see Biotechnologies 2003 for technical specifications). Animals were assayed on different plates. Samples from each age class were distributed at random on the 7 plates used in the study (1 replica per sample). A control sample was assayed in duplicate on each plate. The Hsp72 concentrations of each sample were calculated from standard curves plotted on a log-log scale.

Statistical analysis

Hsp72 concentrations showed a natural log-normal distribution. Therefore, data were ln transformed before statistical analysis. Normality was confirmed by Shapiro-Wilk tests and by graphical inspection.

Simple correlations among repeated measures within age classes were examined graphically and as linear regressions. Similar simple correlations among age classes were based on either a single sample from each age class or the mean concentration of the 2 samples obtained within that age class.

An overall measure of repeatability within and among age classes was calculated as intraclass correlations, estimated from covariance components obtained from a mixed model, which can be written as

| Yijkl = μ + Ci + Bj + Ak + Aki + bi(aikl − ai··) + ɛijkl, (1) |

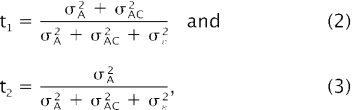

where Yijkl is the ln transformed plasma Hsp72 concentration in sample l from animal k in batch j (day effect) and age class i, μ the common intercept, Ci the effect of age class i, Bj the random effect of sampling batch j, Ak the overall random effect of animal k, Aki the random effect of animal k within age class i, bi the regression coefficient on deviations in age at sampling for animal k from the mean age for age class i (ai·), and ɛijkl the random error term. Because the regression on deviation in age within age class was found to be nonsignificant (NS), this term was omitted from the final model. Repeatability was calculated from covariance components at 2 levels (within [equation 2] and among [equation 3] age classes) as

|

where σA2 is the overall animal variance component, σAC2 the within–age class variance, and σɛ2 the residual variance. Standard errors on the repeatabilities were approximated based on a Taylor series expansion (Lynch and Walsh 1998). Covariance components were estimated using the MIXED procedure of SAS (SAS Institute Inc. 1999). Other statistical analyses were performed using the software packages SAS and standard statistical tests (SPSS 1998; SAS Institute Inc. 1999; Zar 1999).

RESULTS

Plasma Hsp72 concentration

The interassay variability was assessed by the coefficient of variation (CV) and was below 4% for all plates over the working range of the assay. The between-plate CV for the control sample assayed on each plate was 6.7%.

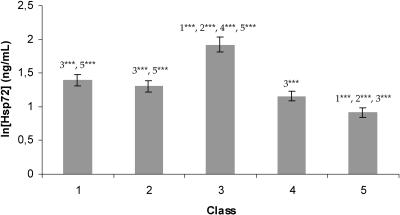

The distribution of the transformed data was approximately normal. Hsp72 concentrations above the lower sensitivity limit for the assay (0.2 ng/mL) were found in all samples (mean, 4.46 ± 0.17 ng/mL; range, 0.24–26.47 ng/mL). The effect of age class was highly significant (F(148,4) = 19.60, P < 0.0001). The Hsp72 concentration was highest in age class 3 (old heifers) and lowest in cows (age classes 4 and 5). Differences in the Hsp72 concentration among age classes were tested by t-tests (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Mean ln Hsp72 concentration ± standard error in the 5 different age classes. Differences in Hsp72 concentration levels among age classes are assessed by t-tests (test results not shown). When the mean concentration level in a given age class differs from the concentration level of another age class, it is indicated by the number of that age class above the column. Significant differences are indicated (*** P < 0.001). Significance levels are adjusted according to sequential Bonferroni correction

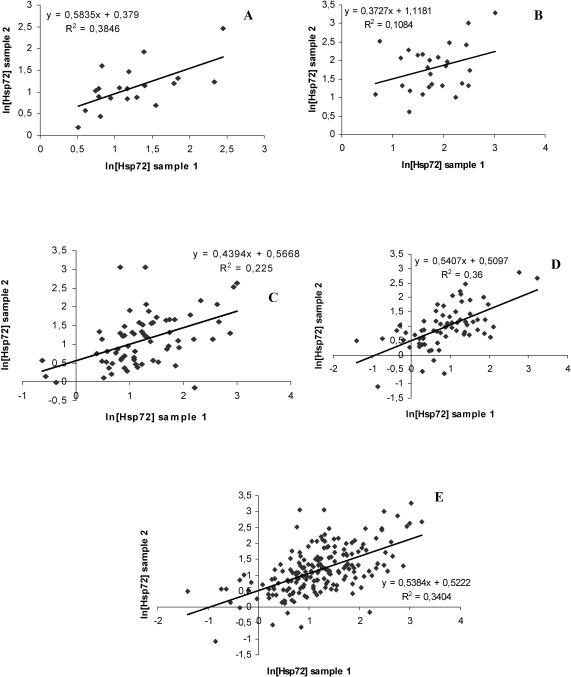

The effect of sampling day (for animals with samples taken a few days apart) within age class was NS in all age classes (age class 1: F(1,20) = 0.18, NS; age class 2: F(1,20) = 1.32, NS; age class 3: F(1,53) = 4.10, NS; age class 4: F(1,137) = 1.11, NS; age class 5: df = 139, F(1,139) = 0.88, NS). The Pearson moment correlation (including all repeated samples) yielded a moderate correlation among Hsp72 concentrations in the blood samples taken from the same animals a few days apart (see Fig 2). Duplicate samples were investigated individually for each age class, except for age classes 1 and 2, where all individuals with repeated samples were pooled because of the low number of animals with repeated measures in these age classes (10 in each age class). The pooling was further justified by the fact that there was no significant difference in Hsp72 concentration among the age classes (Fig 1).

Fig 2.

Correlation between ln Hsp72 concentrations in 2 plasma samples from the same animal taken 1–7 days apart (4.29 ± 0.15 days between blood sampling). (A) Age classes 1 and 2 pooled, (B) age class 3, (C) age class 4, (D) age class 5, and (E) all animals with repeated measures pooled

The graphs reveal moderate correlations between samples 1 and 2, and the repeatability of Hsp72 concentration across sampling day within age class was estimated to be 0.52 ± 0.06 (Fig 2).

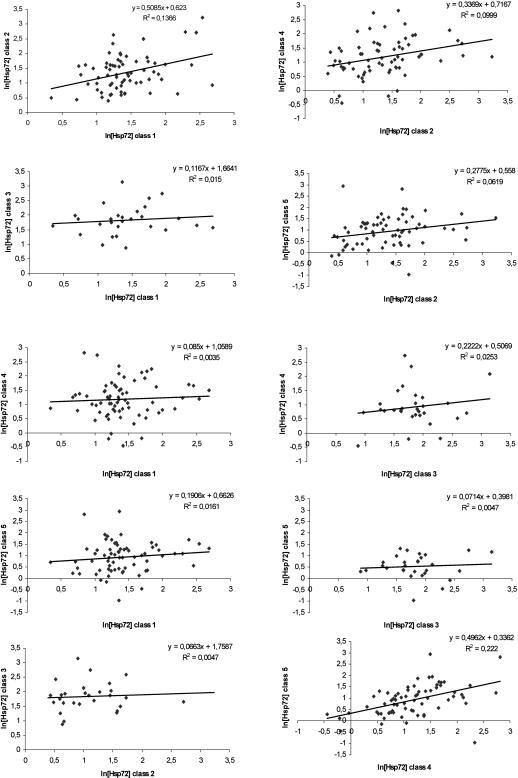

The within-animal correlations across age classes were in general weak (for animals with duplicate samples within age class, the average of the 2 samples was used in the correlation analysis) (Fig 3). However, the concentration level was moderately correlated in young heifers (age classes 1 and 2) and between the 2 age classes of lactating cows (age classes 4 and 5). The repeatability within animal across sampling day was 0.22 ± 0.06 (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Correlation among ln Hsp72 concentrations within animal among age classes

DISCUSSION

Although the mammalian Hsp72 is highly inducible by stress, it has been believed to be absent under normal nonstressful conditions. However, in this study we showed for the first time that Hsp72 is present in the plasma from normal Holstein dairy cattle. Similar results have been obtained from studies on Hsp72 in the circulating system of apparently nonstressed humans (Pockley et al 1998). Therefore, this study questions the dogmatic distinction between inducible and constitutive expression of Hsp72. The environment or the genetic constitution of an organism may often be suboptimal, and livestock animals may commonly be experiencing some degree of stress. Hsp72 regulation may be much more fine tuned than was previously assumed and does not seem to be an on/off mechanism of relevance only in relation to sudden extreme stress exposures (see also Sørensen et al 2003).

The mechanism behind the release of Hsp72 into the circulating system is currently unknown. Our data cannot determine the tissue of origin or the process of release. However, because Hsp72 is present in plasma, the results may indicate that the investigated animals are experiencing some degree of stress (intrinsic or extrinsic) even under environmental conditions that are considered to be benign. Negative side effects of extreme selection for increased production, ie, inbreeding or negative genetic or phenotypic correlations between production and disease resistance traits, may be one reason for this.

From this study it is clear that there is only a moderate correlation among plasma concentrations across age classes. However, the correlation among individual concentration levels within age classes 1 and 2 and age classes 4 and 5 shows that within young heifers and lactating cows, respectively, the Hsp72 concentration in plasma is relatively stable. Within these classes Hsp72 concentration may therefore be useful as an indicator of disease or environmental stress. A departure from an expected (compared with other measures) concentration level within these age classes may be stress induced, and therefore the concentration level may function as a biological indicator for sudden changes in the stress levels. The average Hsp72 concentration level in animals from age class 3 departs from the levels obtained in other age classes, and the within-animal Hsp72 concentration level does not correlate with the concentration levels obtained in the other age classes (Figs 2 and 3). A rather low number of animals have had blood samples taken in this age class, and at this age the animals are shifted to a different stable system. Therefore, the reason for the higher concentration in plasma from animals belonging to age class 3 needs to be investigated further.

Watanabe et al (1997) have shown that the concentration of Hsp90 in mammary tissue is increased during mammary development in late pregnancy and during early lactation but decreases late in lactation and during involution. This demonstrates that Hsp90 plays an important role in mammary development and during lactation. In contrast to these findings we found that within young heifers (age classes 1 and 2) and lactating cows (age classes 4 and 5) the plasma Hsp72 concentration was rather constant. During lactation dairy cattle may experience physiological (metabolic) stress, and available Hsp72 may be bound to intracellular components and mainly released to the circulating systems during less-stressful nonlactating states. This hypothesis is supported by a study showing high intra- but not extracellular levels of Hsp72 increases in physiologically stressed humans (Walsh et al 2001).

Other investigations have shown an age-dependent regulation of Hsps (Niedzwiecki et al 1991; Pahlavani et al 1995; Rea et al 2001; Sørensen and Loeschcke 2002). The results of the present study do not support these findings. However, in this study the variation in age may have been too narrow to conclude whether the concentration of Hsp72 in the plasma is up- or downregulated with age in dairy cattle.

The concentration of Hsp72 is measured with relatively high repeatability (0.52 ± 0.06) across sampling day within age class (repeated samples taken up to 7 days apart). This indicates consistency in the plasma Hsp72 concentration levels at this timescale. Therefore, we have verified that the concentration level in plasma is not significantly affected by minor day-to-day environmental variation in the investigated individuals. This does not invalidate the use of Hsp72 level as a potential indicator of severe stress exposure because we know from other studies that the level of inducible Hsps far exceeds the base level (Rothman 1989; Welch 1992; Kristensen et al 2002).

This study was designed to study repeatability of the Hsp72 concentration with the intention of dedicating further studies to quantitative genetic variation in the expression of Hsps in various tissues and its associations with disease and stress resistance. Although the repeatability across age classes was only moderate (t2 = 0.22), this is a clear indication of conserved individual differences in Hsp72 expression patterns that are likely to be determined by the genetic background of the animals. Apart from being a potential indicator of stress in farm animals, Hsp expression levels may also be used as a selection criterion in animal breeding.

In summary, this study shows that Hsp72 is present in plasma from female dairy cattle and that the age and stage of lactation affect the concentration level. When blood samples are collected from the same animals a few days apart, the Hsp72 concentration level is measured with a repeatability of 0.52. In blood samples taken from the same animals in different age classes, the repeatability in Hsp72 concentration level is 0.22. Evidence for the role of Hsp72 in resistance toward disease and various systematic stresses in Holstein cattle awaits further experimentation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Janne Adamsen for excellent technical help in the laboratory and to the employees at the Skølvad breeding station for blood sampling.

REFERENCES

- Favatier F, Bornman L, Hightower LE, Gunther E, Polla BS. Variation in hsp gene expression and hsp polymorphism: do they contribute to differential disease susceptibility and stress tolerance? Cell Stress Chaperones. 1997;2:141–155. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1997)002<0141:vihgea>2.3.co;2.1466-1268(1997)002<0141:VIHGEA>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder ME, Hofmann GE. Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: evolutionary and ecological physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:243–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.243.0066-4278(1999)061<0243:HPMCAT>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gething M-J, Sambrook J. Protein folding in the cell. Nature. 1992;355:33–45. doi: 10.1038/355033a0.0028-0836(1992)355<0033:PFITC>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature. 1996;381:571–580. doi: 10.1038/381571a0.0028-0836(1996)381<0571:MCICPF>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmodin R, Strandberg E, Madsen P, Jensen J, Jorjani H. Genotype by environment interaction in Nordic cattle studied by use of reaction norms. Acta Agric Scand Sect A Anim Sci. 2002;52:11–24.0906-4702(2002)052<0011:GBEIIN>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen TN, Dahlgaard J, Loeschcke V. Inbreeding affects Hsp70 expression in two species of Drosophila even at benign temperatures. Evol Ecol Res. 2002;4:1209–1216.1522-0613(2002)004<1209:IAHEIT>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S. The heat-shock response. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1151–1191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005443.0066-4154(1986)055<1151:THR>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Walsh B 1998 Genetics and Analysis of Quantitative Traits. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiecki A, Kongpachith AM, Fleming JE. Aging affects expression of 70 kDa heat shock protein in Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:9332–9338.0021-9258(1991)266<9332:AAEOKH>2.0.CO;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen BVH, Andersen S. Selection for growth on normal and reduced protein diets in mice: direct and correlated responses for growth. Genet Res Camb. 1987;50:7–15. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300023272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahlavani MA, Harris MD, Moore SA, Weindruch R, Richardson A. The expression of heat-shock protein-70 decreases with age in lymphocytes from rats and rhesus-monkeys. Exp Cell Res. 1995;218:310–318. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1160.0014-4827(1995)218<0310:TEOHPD>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsell DA, Lindquist S. The function of heat-shock proteins in stress tolerance degradation and reactivation of damaged proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1993;27:437–496. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.27.120193.002253.0066-4197(1993)027<0437:TFOHPI>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockley AG. Heat shock proteins, anti-heat shock protein reactivity and allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2001;71:1503–1507. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200106150-00001.0041-1337(2001)071<1503:HSPASP>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockley AG, Bulmer J, Hanks BM, Wright BH. Identification of human heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60) and anti-Hsp60 antibodies in the peripheral circulation of normal individuals. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1999;4:29–35. doi: 10.1054/csac.1998.0121.1466-1268(1999)004<0029:IOHHSP>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockley AG, Shepherd J, Corton JM. Detection of heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) and anti-Hsp70 antibodies in the serum of normal individuals. Immunol Investig. 1998;27:367–377. doi: 10.3109/08820139809022710.0882-0139(1998)027<0367:DOHSPH>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockley AG, Wu R, Lemne C, Kiessling R, de Faire U, Frostegård J. Circulating heat shock protein 60 is associated with early cardiovascular disease. Hypertension. 2000;36:303–307. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.2.303.0194-911X(2000)036<0303:CHSPIA>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauw WM, Kanis E, Noordhuizen-Stassen EN, Grommers FJ. Undesirable side effects of selection for high production efficiency in farm animals: a review. Livest Prod Sci. 1998;546:15–33.0301-6226(1998)546<0015:USEOSF>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Rea IM, McNerlan S, Pockley AG. Serum heat shock protein and anti-heat shock protein antibody levels in aging. Exp Gerontol. 2001;36:341–352. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00215-1.0531-5565(2001)036<0341:SHSPAA>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roma-Figueroa MG, Camou JP, Yepiz-Plascentia GM. Stress-70 proteins in plasma from stressed and unstressed pigs. J Food Biochem. 1997;21:67–78.0145-8884(1997)021<0067:SPIPFS>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Rothman JE. Polypeptide chain binding proteins: catalysts of protein folding and related processes in cells. Cell. 1989;59:591–601. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90005-6.0092-8674(1989)059<0591:PCBPCO>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. 1999 SAS/STAT Software© Software Version 8. SAS Institute, Cary, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Smith LA, Cassell BG, Pearson RE. The effects of inbreeding on the lifetime performance of dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. 1998;81:2729–2737. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)75830-8.0022-0302(1998)081<2729:TEOIOT>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen JG, Kristensen TN, Loeschcke V. The evolutionary and ecological role of heat shock proteins. Ecol Lett. 2003;6:1025–1037.1461-023X(2003)006<1025:TEAERO>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen JG, Loeschcke V. Decreased heat-shock resistance and down-regulation of Hsp70 expression with increasing age in adult Drosophila melanogaster. Funct Ecol. 2002;16:379–384.0269-8463(2002)016<0379:DHRADO>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- SPSS. 1998 SPSS for Windows, Version 9.0. SPSS, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- StressGen Biotechnologies. 2003 Kit Instruction Manual. Available at: http://www.hsp70kit.com. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh RC, Koukoulas I, Garnham A, Moseley PL, Hargreaves M, Febbraio MA. Exercise increases serum Hsp72 in humans. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6:386–393. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0386:eishih>2.0.co;2.1466-1268(2001)006<0386:EISHIH>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe A, Miyamoto T, Katoh N, Takahashi Y. Effect of stages of lactation on the concentration of a 90-kilodalton heat shock protein in bovine mammary tissue. J Dairy Sci. 1997;80:2372–2379. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(97)76188-5.0022-0302(1997)080<2372:EOSOLO>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch WJ. Mammalian stress response: cell physiology, structure/function of stress proteins, and implications for medicine and disease. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:1063–1081. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.4.1063.0031-9333(1992)072<1063:MSRCPF>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright BH, Corton JM, El-Nahas AM, Wood RFM, Pockley AG. Elevated levels of circulating heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) in peripheral and renal vascular disease. Heart Vessels. 2000;15:18–22. doi: 10.1007/s003800070043.0910-8327(2000)015<0018:ELOCHS>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zar JH 1999 Biostatistical Analysis, 4th ed. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. [Google Scholar]