ABSTRACT

The pathogenic yeast Candida auris represents a global threat of the utmost clinical relevance. This emerging fungal species is remarkable in its resistance to commonly used antifungal agents and its persistence in the nosocomial settings. The innate immune system is one the first lines of defense preventing the dissemination of pathogens in the host. C. auris is susceptible to circulating phagocytes, and understanding the molecular details of these interactions may suggest routes to improved therapies. In this work, we examined the interactions of this yeast with macrophages. We found that macrophages avidly phagocytose C. auris; however, intracellular replication is not inhibited, indicating that C. auris resists the killing mechanisms imposed by the phagocyte. Unlike Candida albicans, phagocytosis of C. auris does not induce macrophage lysis. The transcriptional response of C. auris to macrophage phagocytosis is very similar to other members of the CUG clade (C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. lusitaniae), i.e., downregulation of transcription/translation and upregulation of alternative carbon metabolism pathways, transporters, and induction of oxidative stress response and proteolysis. Gene family expansions are common in this yeast, and we found that many of these genes are induced in response to macrophage co-incubation. Among these, amino acid and oligopeptide transporters, as well as lipases and proteases, are upregulated. Thus, C. auris shares key transcriptional signatures shared with other fungal pathogens and capitalizes on the expansion of gene families coding for potential virulence attributes that allow its survival, persistence, and evasion of the innate immune system.

KEYWORDS: Candida auris, macrophage, host-pathogen interactions, transcriptional profile

INTRODUCTION

Candida auris is an emergent fungal pathogen of extremely high clinical and public health relevance (1). First isolated from an ear infection in Japan (2), numerous outbreaks have been reported worldwide. Whole genome sequencing has revealed the existence of at least five geographically based clades: South Asia (Clade I), East Asia (II), southern Africa (IV), South America (IV), and Iran (V) (3, 4). Closely related to Candida (Clavispora) lusitaniae, C. auris and other species of concern (e.g., C. haemulonii) have intrinsic resistance to the commonly used triazole antifungals, like fluconazole, and some isolates have developed tolerance to echinocandins and amphotericin B, used to treat invasive fungal infections. Perhaps 5–10% of isolates are resistant to all three classes of clinically useful antifungal agents (5, 6). This highlights the need to understand the pathogenicity mechanisms that enable C. auris to invade and thrive in the host, and to find novel therapeutic targets allowing the treatment of multidrug resistant isolates.

Predisposing factors that confer susceptibility to C. auris infection are shared with other Candida infections and include iatrogenic factors, immune dysfunction, and antibiotic exposure (1). Patients in intensive care units are particularly at risk, with mortality rates ranging from 30% to 72% (7). While person-to-person transmission is not generally a route of infection in most cases of candidiasis, save C. parapsilosis in neonatal ICUs (8), it is common with C. auris, mediated through the contamination of bedding, shared medical equipment like temporal thermometers and blood pressure cuffs, and skin colonization of health care workers (9 – 11).

Phagocytic cells represent one of the first lines of defense in the host (12). Macrophages are professional phagocytes found either as resident cells patrolling organs and tissues or recruited from the bloodstream where they circulate as monocytes. The attempt to eliminate pathogens begins with recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), i.e., carbohydrate moieties on the cell wall of fungi, such as mannans, glucans, and chitin (13), or the recognition of opsonizing molecules on the surface of microbes, like neutralizing antibodies or complement-derived molecules (12). This triggers phagocytosis into a specialized organelle, the phagolysosome, containing acidic hydrolases, antimicrobial peptides, and oxidative and nitrosative stresses, which are intended to damage the engulfed microbe (14).

Fungal pathogens have a conserved response to macrophage phagocytosis (14 – 22). The intracellular environment of the phagocyte seems to be restrictive in the amounts of available sugars for the pathogen utilization, leading to a metabolic switch in which pathways that allow the utilization of alternative carbon sources and nutrient scavenging mechanisms are upregulated. These include pathways for the catabolism of carboxylic acids, amino acids, fatty acids, and N-acetylglucosamine (17, 23). In addition, detoxifying mechanisms that allow coping with oxidative stress are also activated. Reactive oxygen species are inactivated by means of enzymes such as superoxide dismutases and catalases (24, 25), whereas nitrosative stress induces flavohemoglobin enzymes that scavenge nitric oxide (26). Thus, many fungal pathogens are well equipped with virulence attributes that allow them to counteract the macrophage killing mechanisms. In fact, there are numerous examples of pathogenic yeast that replicate within macrophages e.g., Cryptococcus neoformans (20), Histoplasma capsulatum (27), and Candida glabrata (28). Even Candida albicans, which normally forms hyphae that extend and rupture the macrophage membrane, may exhibit this behavior: the non-filamentous mutant efg1Δ/Δ cph1Δ/Δ replicates inside macrophages (17).

Unlike C. albicans, C. auris exists primarily in the yeast morphotype and, although reports exist of pseudohyphae under specific conditions (29 – 31), the role of morphogenesis in virulence remains inconclusive in this species. Genomic studies have shown that genes associated with virulence in other species have expanded gene families (32). Particularly, oligopeptide transporters and secreted lipases are expanded in a similar fashion as they are in C. albicans (33 – 35), emphasizing the potential importance of nutrient uptake in surviving phagocytosis, as has been demonstrated in C. albicans and other species (35 – 38).

In this report, we investigated the interactions of C. auris with macrophages. We demonstrate that macrophages avidly phagocytose C. auris cells; however, like other fungal pathogens, this yeast replicates intracellularly. Unlike C. albicans, C. auris inflicts no apparent damage to the phagocyte. We analyzed the transcriptional response of C. auris upon co-incubation with macrophages and showed that C. auris shares a core metabolic response with other Candida species, inducing genes required for alternative carbon metabolism, nutrient transport, and proteolysis, as well as oxidative stress responses. Additionally, species-specific responses are upregulated; however, the absence of orthologs suggests the emergence of novel genes that may contribute to the virulence of C. auris.

RESULTS

Macrophages phagocytose C. auris and restrict its growth

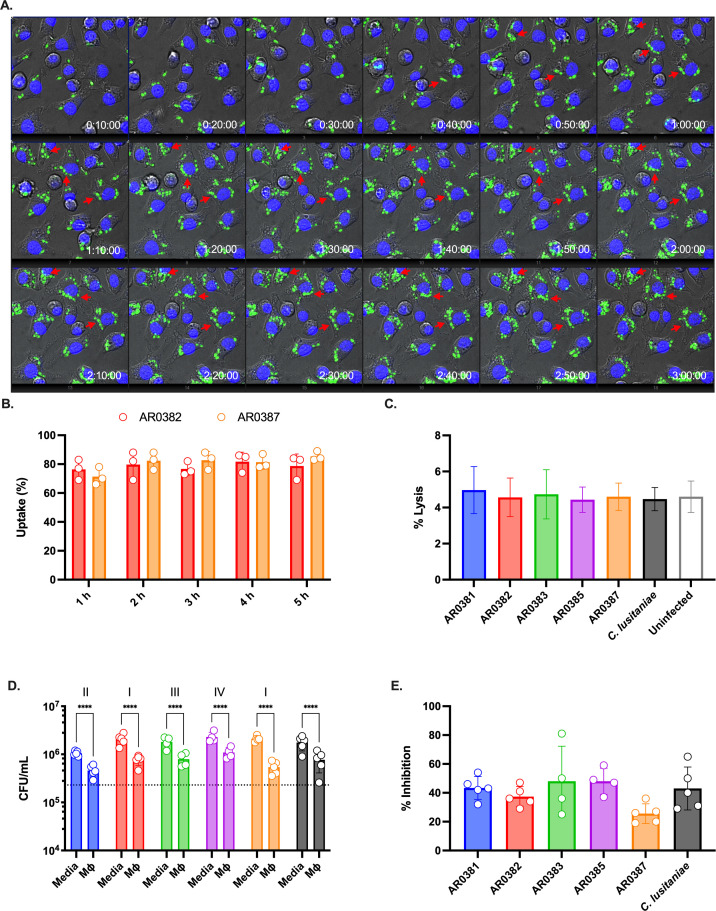

Phagocytes are one of the first lines of defense during fungal infections. We sought to understand the interaction between C. auris and macrophages. The first step of this interaction is the recognition of fungal cells by the phagocytes, followed by internalization and processing. As shown in Fig. 1A; Videos S1 and S2, macrophages readily detect and avidly phagocytose cells of the C. auris clade I strain AR0382. Fungal uptake was monitored and nearly all macrophages had engulfed at least one fungal cell (Fig. 1B). Uptake did not differ significantly between strains, including a second clade I isolate (AR0387, Fig. 1B) or strains from clades I, II, III, or IV (respectively, AR0387, AR0381, AR0383, AR0386; Fig. S1). Notably, engulfed C. auris cells can divide inside the macrophage (Fig. 1A, red arrows), like other fungal pathogens (e.g., C. neoformans, H. capsulatum, C. glabrata), able to subvert the inhospitable environment and killing mechanisms of the intracellular environment of the phagocyte.

Fig 1.

Macrophages phagocytose and constraint C. auris survival. (A) J774A.1 macrophages were loaded with Hoechst 33342 and infected with GFP-labeled C. auris (AR0382), MOI 5. Time lapse was performed for 3 h. The red arrows point to examples of C. auris cells dividing inside the macrophage. (B) Percentage of macrophages with at least one engulfed C. auris cell. GFP-labeled C. auris strains (AR0382 and AR0387) were used to infect Hoechst-labeled macrophages. Time lapse was performed for 5 h and quantified at indicated time points; n = 3, mean and standard deviation. (C) Macrophage damage was determined by measuring the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity in the supernatant after infection with C. auris for 5 h. A control with the less pathogenic C. lusitaniae was included for comparison. A negative control where macrophages were not infected was also included. Maximal LDH activity was determined in detergent-lysed control, set as 100%; n = 3, mean and standard deviation. (D) Colony-forming units were determined after infecting J774A.1 macrophages for 5 h. As controls, C. auris was inoculated in media-only to assess replication in the absence of phagocytes. Dotted line indicates the average initial CFU count (2.3 × 107 CFU/mL); n = 5, mean and standard deviation. Data were analyzed with two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison test to determine statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). (E) The average CFU count of C. auris co-cultured with macrophages for 5 h relative to media-only controls (defined as 100%).

In contrast to C. albicans, which transitions to its filamentous morphology inside macrophages, C. auris remains in the yeast morphotype (Fig. 1A). We investigated whether C. auris infection results in macrophages damage. As proxy of macrophage integrity, we determined lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity in the supernatants of macrophages infected with different isolates of C. auris for 5 h. Despite active fungal replication inside the phagocytes, infection by C. auris does not induce cellular damage of infected macrophages. In fact, LDH release during the first 5 h of infection is comparable to the uninfected control (Fig. 1C). For comparison, co-incubation with C. albicans induces the lysis of greater than 50% of the macrophages in similar experimental conditions (39).

We then investigated whether macrophages provide any antifungal measure to inhibit the replication of C. auris. We compared the colony-forming units (CFUs) of C. auris in culture media DMEM and after macrophage infection. As shown in Fig. 1D, CFUs are lower when macrophages are present, indicating that despite C. auris intracellular replication, macrophages are at least partially able to restrict fungal division; in all strains, CFUs were at least 50% lower in the presence of macrophages than the absence (Fig. 1E), but this offers little evidence for substantial fungal killing by these phagocytes.

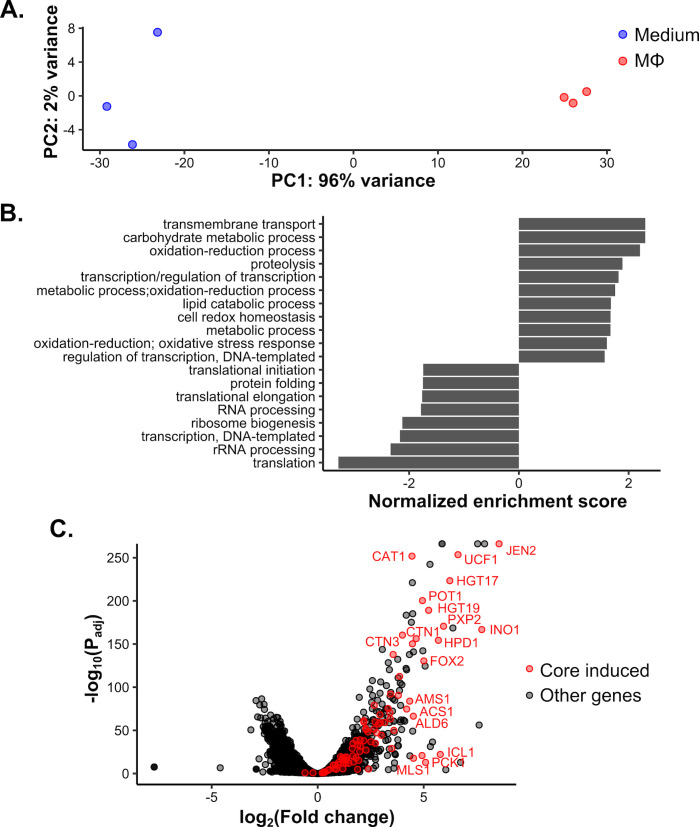

Phagocytosis induces an alternative carbon metabolism response in the transcriptome

Having established that C. auris can be taken up by and reside within macrophages, we next investigated its response to phagocytosis. Previous work has demonstrated that the C. albicans response to phagocytosis is dominated by induction of the alternative carbon metabolism response and repression of transcription and translation-related genes (17, 21, 22), and we recently showed that this response is broadly conserved across CUG-clade Candida spp. (15). Principal component analysis of C. auris AR0382 incubated for 1 h in the presence or absence of macrophages revealed clear segregation of samples by condition along principal component 1 (Fig. 2A). PC-1 captured 96% of variation in the data, indicating that variation between samples across conditions was far greater than within conditions. To identify the pathways driving these differences, we performed Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) (40, 41) on the log-fold change in gene expression between conditions (Fig. 2B). As for other species, we observed induction of metabolic functions and repression of transcription and translation, consistent with our observation that growth is retarded (Fig. 1D). We previously defined a core conserved set of 92 genes induced in other CUG species and asked if they were similarly induced in C. auris. Of 87 genes with C. auris orthologs, 83 genes were significantly induced (Fig. 2C). These included several key alternative carbon response genes (e.g., ICL1, FOX2, and JEN2) and some that were involved in defense against oxidative stress (e.g., CAT1). In pairwise comparisons, C. auris showed highly significant correlations in response with both C. albicans and the more closely related but less pathogenic C. lusitaniae (Fig. S2). Taken together, conservation of the phagocytosis response noted in other species clearly extends to C. auris, suggesting that it may use similar metabolic and growth strategies to survive and adapt within macrophages.

Fig 2.

Macrophages elicit an alternative carbon metabolism-driven transcriptional response shared with other Candida species. (A) Principal component analysis distinguishes C. auris incubated with macrophages from those in medium-only conditions. The percentage of variance explained by each of the first two principal components is indicated. (B) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis for GO terms significantly associated with shifts in log2-fold change (false discovery rate = 0.1). Positive and negative normalized enrichment scores reflect GO terms induced and repressed during phagocytosis, respectively. (C) Volcano plot of the phagocytosis response. Genes in the previously determined conserved induced gene set are in red, with select highly induced genes labeled.

Phagocytosis elicits induction of unique and expanded gene families in C. auris

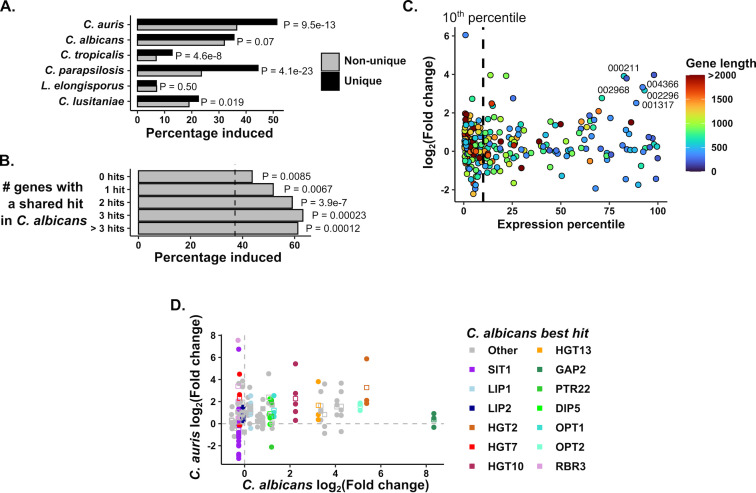

Since the overall response to phagocytosis was highly conserved among orthologous groups of genes across species, we decided to investigate further those genes that did not have a direct ortholog mapped in other CUG-clade species. Previously, we observed that species-specific genes are enriched for phagocytosis induction in some species but not others, with C. parapsilosis-specific genes being particularly enriched for phagocytosis-induced transporter genes (15). In this context, we decided to compare the 498 C. auris-specific genes without orthologs in these species. Like C. parapsilosis, C. auris-specific genes showed a stronger enrichment of phagocytosis induction than other species (Fig. 3A). Here we define species-specific genes as those that do not have an ortholog mapped in the Candida Gene Order Browser (CGOB) (42), which defines orthology by one-to-one mappings using sequence homology and genomic synteny. However, this can arise either because a gene has no identifiable sequence homolog or because events such as gene family expansion or genomic rearrangements mean that they do not share a one-to-one pairing with another species. Therefore, we classified C. auris-specific genes based on whether they have a BLAST hit in C. albicans (E value < 1e-5), and if they do, how many C. auris genes have homology to that C. albicans hit (where having multiple C. auris genes mapping to a single C. albicans gene indicates expansion of that gene family since the divergence between species) (Table S1). Interestingly, we saw enrichment of phagocytosis-induced genes across these categories, although this was strongest for the C. auris genes with evidence of expansion (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3.

C. auris-specific and expanded gene families are induced in response to phagocytosis. (A) C. auris-specific genes are especially enriched for phagocytosis-induced genes. For each species, genes specific to that species were identified (i.e., those without orthologs in any of the five other species compared here) and the percentage of species-specific genes induced by phagocytosis was compared to that of shared genes. P values were calculated by hypergeometric test. (B) C. auris-specific genes were categorized based on whether they had a BLAST hit in C. albicans and if they did, how many C. auris genes shared that hit (those genes without a C. albicans hit are labeled “0 hits”). The percentage of induced genes in each group is shown, with the vertical dashed line representing the percentage induced among all C. auris genes. By hypergeometric test, each class of genes was significantly enriched for induced genes. (C) Response of C. auris genes without a C. albicans BLAST hit as a function of Expression level and gene length. Expression percentile was calculated from the length-corrected mean expression level. Note that most genes in this category are in the bottom 10% of expressed genes (vertical dashed line). Colors indicate gene length, and genes that are at least 300 bp in length with strong average expression and induction are labeled (“B9J08_” suffixes have been removed from gene IDs, see Table S2 for more information). (D) Comparison of C. auris and C. albicans transcriptional responses in genes with evidence of C. auris expansion. For all genes whose best BLAST hit mapped to the same C. albicans gene as at least two other genes, the log2-fold change is compared to that of the C. albicans sequence homolog. Points indicate individual genes, squares the mean expression for that family. Genes highlighted are labeled by the C. albicans gene name directly above the points. Dashed lines mark a log2-fold change of zero in either species.

Among C. auris-specific genes without a C. albicans homolog, we observed no overall functional enrichment by GO term analysis. These genes were generally both shorter and expressed at lower levels than those with identifiable C. albicans homologs (Fig. S3). Together this suggests that some of these may be pseudogenes. Nevertheless, some phagocytosis-responsive C. auris genes in this category were neither short (CDS length > 300 bp) nor poorly expressed (>50th percentile by mean expression) (Fig. 3C). Most of these were proteins of unknown function that had no BLAST hit in any other Candida species (Table S2). Therefore, similar to previous observations we made in C. albicans (15), C. auris has a number of genes that are induced in response to the host cells but whose biological function or role in virulence are currently unknown.

Next, we examined C. auris-specific genes with evidence of expansion (at least three C. auris genes mapping to the same C. albicans homolog), since these showed particularly strong enrichment for induced genes (Fig. 3B). Among induced genes in this group, we observed a functional enrichment of GO terms for “transmembrane transport,” “localization,” and “iron import into the cell” functions. We wished to determine how much these expanded families mirrored the same pattern of induction as seen in C. albicans. Therefore, for all genes with evidence of expansion, we compared their response to phagocytosis to their best BLAST hit in C. albicans (Fig. 3D). Among carbohydrate transporters (HGT2, HGT10, and HGT13), we observed a strong trend for shared induction in both species. Similarly, sequence homologs of several amino acid and oligopeptide transporters (DIP5, PTR22, OPT1, and OPT2) were broadly induced, although in contrast to C. albicans, GAP2 sequence homologs were not. Sequence homologs of the lipase LIP1 and the protease SAP9 were modestly induced in C. auris but not in C. albicans. However, for sequence homologs of the iron transporter SIT1, there was considerable variation in response. While most SIT1 homologs showed little induction or even repression, B9J08_001499 was 107-fold induced. Similarly, for homologs of the adhesin-like protein RBR3, most showed little change but B9J08_004098 was induced 187-fold. Therefore, while many genes in expanded families show similar regulation to their orthologs in C. albicans, a subset exhibit independent phagocytosis induction. Together, the C. auris data bear strong resemblance to C. albicans and other species but suggest that it has responded to similar evolutionary pressures in slightly different ways than other species, as might be expected.

DISCUSSION

In this work we investigated the interactions of Candida auris with cells from the innate immune system, the macrophages. Previous research studied this interaction in an ex vivo whole blood model (43) and with isolated human neutrophils (44). In the whole blood model, neutrophils are responsible for most of the killing observed under these conditions, although association with monocytes and leukocytes (NK cells) was reported at considerably lower levels. This model shows efficient killing of C. auris, although it was noted that about 10% of the fungal population survives which could initiate organ invasion. In stark contrast, isolated neutrophils were shown to be unable to properly recognize, engulf, or induce NET formation in response to C. auris (44). This may be explained by the experimental setting in which the phagocytes were isolated and other opsonizing molecules necessary for proper recognition are missing i.e., antibodies and the complement system found in whole blood. Under our experimental conditions we observed efficient phagocytosis of C. auris by both bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) (not shown) and the phagocytic cell line J774A.1 (Fig. 1A), which is in accordance to a previous report using both murine BMDMs and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (45). Wang et al. reported that phagocytosis of C. auris by BMDMs is less robust compared to C. albicans (46), ranging from 0% to 60% phagocytes engaged in fungal uptake. In our experiments, consistent phagocyte engagement was observed throughout the experiment (Fig. 1B). Although the strain used in Wang et al. and the strains we used for this part of our study belong all to Clade 1, intraclade differences could account for this discrepancy. Our work suggests that receptors on macrophages are sufficient to efficiently recognize and phagocytose C. auris in an opsonization independent manner. Supporting this point, Bruno et al. demonstrated that β-glucans mediate the early response to C. auris, whereas mannan recognition orchestrates host responses at later time points (45). However, it should also be noted that mannosylation of the C. auris cell wall deeply impacts recognition by the immune system: masking of the β-glucan layer by mannans decreases recognition failing to activate key MAPK pathways, particularly p38 and, in turn, secretion of proinflammatory cytokines that are key for proper host responses and fungal clearance (46). The contribution of C. auris cell wall mannans may go beyond mere physical masking of glucans since the low complexity and small molecular mass of the mannose chains may have a direct impact on the affinity of macrophages receptors like dectin-2 and mannose receptors (45). Adding evidence of the contribution of low complexity mannans to immune evasion is Horton et al. work showing that C. auris null mutants with a decreased mannan content are efficiently phagocytosed by neutrophils and exhibit increased killing (47).

Despite efficient phagocytosis, C. auris divides inside macrophages. This is in accordance with a recent report describing fungal replication inside macrophages, without apparent damage to the phagocyte for the first 8–10 h (22). Previous reports have investigated C. auris-macrophage interactions with a focus on relative early time points (45, 46), since C. albicans effects on macrophage activation and viability occur within the first 6–8 h (inflammasome activation, cytokine production, cell lysis) (48, 49). In agreement with previous work, we show that C. auris exerts relatively little to no damage, measured as cell lysis during the first 5 h of infection. Weerasinghe et al. showed that C. auris escapes from macrophages; however, this occurs at later time points beyond what is observed in C. albicans (22). In fact, LDH release, a widely used indicator of phagocyte integrity, remains low up until 16 h, comparable to uninfected controls. Moreover, NRLP3 inflammasome activation is not triggered by C. auris, even though the fungal cells are actively dividing intracellularly. It is only when C. auris escapes from the macrophage at later time points when the now extracellular yeasts can consume the nutrients available in the media, starving the macrophages and killing them. The exact molecular mechanisms that lead to C. auris-mediated macrophage cell death remain elusive (22).

We sought to investigate the transcriptional response to macrophage engulfment. Not surprisingly, C. auris shares the core transcriptional response that other members of the CUG clade exhibit during co-culture with macrophages (15). This reinforces the argument that simple sugars are limited or readily available in the intracellularly milieu, so pathogens resort to the utilization of the available nutrients such as organic acids and lipids to sustain viability and growth. A recent report has unraveled a less obvious role of a lipase in C. albicans: Lip2, one of a 10-member family, promotes deep tissue invasion by downregulating the IL-17 pathway that promotes fungal clearance, via suppression by palmitic acid, a product of the lipase activity (50). C. auris transcriptional response includes several lipase encoding genes (B9J08_004172, B9J08_004173, B9J08_004176, and B9J08_004177), including the CaLIP2 homolog. The possibility that C. auris could make use of this immune suppression strategy is intriguing.

Several fungal lineages have developed approaches to resist and overcome the hostile intracellular conditions found in the phagosome (16). C. neoformans possesses a thick polysaccharide capsule that physically protects from oxidative stress (51), and the melanin in the cell wall scavenges free radicals (52). Transcriptionally, C. neoformans induces detoxification systems that decomposes nitric oxide (53), a mechanism that enables survival. C. auris modestly upregulates the YHB1 homolog, B9J08_002691, which in C. albicans detoxifies nitric oxide (26), is induced by macrophages (17), and contributes to survival when confronted to phagocytes (54). H. capsulatum, another fungal pathogen that divides intracellularly in macrophages, prevents the acidification of the phagosome and upregulates iron-scavenging siderophores and two catalases (27, 55). In C. auris, the SIT1 ortholog, encoding a siderophore transporter (56), underwent an expansion (Fig. 3D), and at least one member, B9J08_001499, is strongly induced, indicating that iron scavenging systems may be relevant for C. auris survival. Likewise, the homologs of well-characterized systems that aid in detoxification of ROS are all induced in C. auris: CAT1 (catalase, B9J08_002298), GPX (glutathione peroxidase, B9J08_003442), and SOD2 (superoxide dismutase, B9J08_000528), reinforcing the idea that the response to oxidative stress is conserved in this species as part of the response to macrophages. Surprisingly, these systems were not part of the transcriptional response observed in the whole blood model, in which the thioredoxin system seems to be more relevant (43).

C. albicans and C. glabrata also evolved mechanisms that promote survival and replication inside macrophages. C. albicans metabolism switches to utilize organic, fatty, and amino acids (17). This metabolic adaptation is critical for survival (57 – 60). Additionally, it has been shown that C. albicans resides in a modified phagosome conducive for survival, though the molecular details remain unclear (61). This allows C. albicans to undergo the yeast-to-hypha transition that allows escaping from the phagocyte (62, 63). Similarly, C. glabrata resides in a partially acidified- modified-phagosome that permits survival and replication (28). In contrast to C. albicans, C. glabrata remains in the yeast form since it is unable to filament. Although similar strategies are observed in both cases, C. albicans damages the phagocyte, triggering a proinflammatory response via pyroptosis (48, 49), whereas C. glabrata does not (28). Our results suggest that C. auris likely uses a similar strategy to that of C. glabrata, in which it is recognized and phagocytosed, but phagosome maturation is stunted, and the integrity of the phagocyte maintained, allowing for intracellular replication. Interestingly, C. auris lacks a homolog of the fungal toxin candidalysin, known to activate the NLRP3-inflammasome (64) and permeabilize the macrophage membrane to facilitate C. albicans escape (65, 66). Interestingly, one difference between CUG species that are cytotoxic and those that are not is the presence of a homolog of candidalysin (encoded by the ECE1 gene). For instance, C. parapsilosis and C. lusitaniae, which do not have candidalysin, elicited significantly less macrophage damage and lower secretion of the proinflammatory chemokine CCL3 (15). The absence of an ECE1 homolog in C. auris may contribute to the immune evasion preventing a pro-inflammatory response that allows fungal survival. In vivo, this has important consequences since macrophages could be used to hide from immune surveillance by other phagocytes (i.e., neutrophils and dendritic cells) or other immune effectors (NK cells), allowing C. auris to persist in the host.

In conclusion, C. auris is recognized and phagocytosed avidly by macrophages and this does not differ substantially between strains or clades. It is not effectively killed by these phagocytes, but neither does it damage these immune cells. Its transcriptional response to phagocytosis is highly similar to other CUG clade species but includes C. auris-specific genes that represent both unique factors and expansions of gene families similar to other organisms. Despite the recent emergence of this pathogen of concern, its interaction with macrophages resembles both pathogenic and non-pathogenic members of the CUG clade.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions

Strains used in this study are described in Table 1. Strains were routinely grown on liquid YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose) overnight at 30°C in a shaking incubator (180–200 rpm).

TABLE 1.

Candida strains used in this study

| Species | Strain | Genotype | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans | SC5314 | Wild type | Clinical isolate (67) |

| Candida auris | B11220 (AR0381) | ENO1-RFP-SAT1 | Clinical isolate – CDC (68) |

| B11109 (AR0382) | Clinical isolate – CDC | ||

| CaPM480 (AR0382) | ENO1-T2A-eGFP-SAT1 | This work | |

| CaPM484 (AR0382) | ENO1-T2A-mCh-SAT1 | This work | |

| B11221 (AR0383) | ENO1-RFP-SAT1 | Clinical isolate – CDC (68) | |

| B11222 (AR0384) | Clinical isolate – CDC | ||

| B11244 (AR0385) | Clinical isolate – CDC | ||

| B11245 (AR0386) | ENO1-RFP-SAT1 | Clinical isolate – CDC (68) | |

| B8441 (AR0387) | ENO1-RFP-SAT1 | Clinical isolate – CDC (68) | |

| CaPM482 (AR0387) | ENO1-T2A-eGFP-SAT1 | This work | |

| CaPM486 (AR0387) | ENO1-T2A-mCh-SAT1 | This work | |

| B11098 (AR0388) | Clinical isolate – CDC | ||

| Candida lusitaniae | AR0398 | Clinical isolate – CDC |

C. auris labeling

A fluorescent protein (eGFP or mCherry) was expressed in C. auris using a construct where its expression was driven by the ENO1 gene, similar to a previous approach (68). To generate this, a 1,514-bp fragment containing C. auris ENO1 and part of its promoter was cloned in front of CUG-optimized eGFP or mCherry as a fusion protein, separated by the self-cleaving T2A peptide (69), resulting in the production of Eno1 and the fluorescent protein as two separate polypeptides. This fragment was cloned into a plasmid containing the nourseothricin resistance marker SAT1, containing a 1,020-bp fragment of the ENO1 downstream region, generating pENO1GFP-SAT1 or pENO1mCh-SAT1. The expression cassette was released with XhoI and ApaI to electroporate competent C. auris (AR0382 and AR0387) cells. Transformants were screened by colony PCR and by assessing the fluorescence intensity in a microplate reader assay.

Macrophage culture and media

BMDMs were differentiated from bone marrow cells isolated from the femurs and tibiae of outbred female ICR mice. Cells were grown and differentiated in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (GE Healthcare) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Corning) and penicillin/streptomycin (Corning), supplemented with 20 ng/mL recombinant mouse GM-CSF (R&D Systems) for 7 days. Animal protocols were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

J774A.1 mouse macrophages (ATTC TIB-67) were routinely grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (high glucose, GE Healthcare) with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. Cell cultures were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Fungal survival, phagocytosis, and macrophage lysis

The survival of C. auris after co-incubation with macrophages was assessed using J774A.1 macrophages that were cultured in 12-well plates to a density of 4 × 106 cells per well. Overnight cultures from fungal strains were outgrown for 3 h in YPD at 30°C, washed twice with 1x PBS and adjusted to the desired concentration. Macrophages were infected with the fungal suspensions and incubated for 5 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. After incubation, fungal cells were released from macrophages by adding Triton X-100 (0.05% final concentration). Serial dilutions were performed and plated on YPD and incubated at 30°C until colonies were visible. To examine phagocytosis of C. auris, J774A.1 murine macrophages were prestained with Hoechst 33342 (NucBlue Live ReadyProbes Reagent, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Phagocytes were infected with red fluorescent protein (RFP)-labeled C. auris cells (68) or GFP-labeled C. auris strains. Samples were fixed after 3 h with 4% paraformaldehyde and images were captured on the Cytation 5 Cell Imaging Multi-Mode Reader (BioTek). For time-lapse experiments, images were acquired every 10 min for 3 h using an Olympus IX83 spinning disk confocal microscope using stage-top environmental controls to maintain the co-cultures at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Macrophage lysis was assessed by determining the LDH activity as a proxy of cellular integrity after infecting the phagocytes with C. auris strains, using the CytoTox96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity assay (Promega), as described (63). J774A.1 macrophages were cultured in a 96-well plate (2.5 × 105 cells mL−1, 100 µL per well) and incubated for 24 h. Media was replaced with DMEM without Phenol Red prior to infection. C. auris strains were outgrown for 3 h in fresh YPD, washed, and the concentration adjusted to infect the cultured phagocytes at an approximate macrophage-fungal cell ratio of 1:5. Infection was allowed to proceed for 5 h. Maximal LDH release was achieved by lysing macrophages with Triton X-100, for normalization purposes.

RNA preparation and sequencing

C. auris overnight cultures were washed in PBS and diluted in IMDM. Wells containing BMDMs (5 × 106 per well in a 6-well plate) were then infected at an MOI of 5 for 1 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Fungal cells were scraped off with ice-cold water and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min. To ensure complete macrophage lysis, pellets were resuspended in ice-cold water and centrifuged again. Fungal cell walls were digested with 40 U zymolyase (United States Biological) incubated for 5 min at 37°C and RNA was isolated using the SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega). RNA integrity was assessed using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Library preparation and sequencing was performed by Psomagen, Inc, using the TruSeq stranded mRNA kit. Deep sequencing obtained 35–45 million paired end 150 bp reads per sample. Three independent biological replicates were analyzed.

RNA-seq data analysis

While the RNA extraction protocol used here selectively captures fungal RNA, with most macrophage RNA removed during washing, nevertheless we initially depleted mouse sequencing reads by mapping to the mouse genome [Ensembl release 98 (70)] with HISAT2 v2.1.0 (71). Next, we quantified C. auris transcripts from the unmapped reads to the C. auris B8441 reference transcriptome [FungiDB release 39 (72)] using Salmon v1.1.0 (73) with –gcBias and –seqBias flags enabled. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 v1.38.2 (74) with full results given in Table S1. To avoid inflation of fold changes for low-expressed genes, log2-fold change (LFC) estimates were subject to shrinkage using the “apeglm” method (75). PCA was performed using expression counts transformed using the variance stabilizing transformation. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis was performed on LFCs using the fgsea package v1.24.0 in R using GO term annotation obtained from FungiDB. GO term enrichment on induced genes was otherwise performed using the “GO term finder” tool in the Candida Genome Database (CGD) (76). Annotation from CGOB v2 (42, 77) was used to determine orthologs between species based on both sequence homology and genomic synteny. For C. auris genes without an ortholog in C. albicans, we obtained annotation of best BLAST hits from the CGD. These mappings were generated previously using BLASTP with parameters -F \"m S\" -M BLOSUM80, with an expectation value (E) threshold of 1e-5 for inclusion. For comparison of mean expression levels, the average expression across samples (calculated as “baseMean” in DESeq2) was subject to length correction as expression divided by the exonic gene length multiplied by the median length across genes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the Mycotic Diseases Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for making the C. auris strains available. Thanks to Teresa O’Meara for sharing of strains and plasmids. We thank Hannah Wilson for helping perform microscopy imaging. Thanks also to Dr. Michael Gustin and members of the Lorenz lab for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by NIH award R01AI143304 to M.C.L.

Contributor Information

Michael C. Lorenz, Email: Michael.Lorenz@uth.tmc.edu.

Mairi C. Noverr, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.00274-23.

Macrophages uptake C. auris.

The C. auris response correlates with that of other Candida species.

C. auris-specific genes without a C. albicans BLAST hit are shorter and lower-expressed.

Differential expression analysis and phagocytosis-induced genes.

Legends of Fig. S1 to S3, Videos S1 and S2, and Tables S1 and S2.

Time lapse microscopy of GFP-labeled C. auris CaPM480 infecting J774A.1 macrophages.

Time lapse microscopy of mCherry-labeled C. auris CaPM486 infecting J774A.1 macrophages.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Watkins RR, Gowen R, Lionakis MS, Ghannoum M. 2022. Update on the pathogenesis, virulence, and treatment of Candida auris Pathog Immun 7:46–65. doi: 10.20411/pai.v7i2.535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Satoh K, Makimura K, Hasumi Y, Nishiyama Y, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H. 2009. Candida auris SP. Nov., a novel ascomycetous yeast isolated from the external ear canal of an inpatient in a Japanese hospital. Microbiol Immunol 53:41–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2008.00083.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chow NA, Muñoz JF, Gade L, Berkow EL, Li X, Welsh RM, Forsberg K, Lockhart SR, Adam R, Alanio A, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Althawadi S, Araúz AB, Ben-Ami R, Bharat A, Calvo B, Desnos-Ollivier M, Escandón P, Gardam D, Gunturu R, Heath CH, Kurzai O, Martin R, Litvintseva AP, Cuomo CA. 2020. Tracing the evolutionary history and global expansion of Candida auris using population genomic analyses. mBio 11:e03364-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03364-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spruijtenburg B, Badali H, Abastabar M, Mirhendi H, Khodavaisy S, Sharifisooraki J, Taghizadeh Armaki M, de Groot T, Meis JF. 2022. Confirmation of fifth Candida auris clade by whole genome sequencing. Emerg Microbes Infect 11:2405–2411. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2125349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chowdhary A, Prakash A, Sharma C, Kordalewska M, Kumar A, Sarma S, Tarai B, Singh A, Upadhyaya G, Upadhyay S, Yadav P, Singh PK, Khillan V, Sachdeva N, Perlin DS, Meis JF. 2018. A Multicentre study of antifungal susceptibility patterns among 350 Candida auris isolates (2009-17) in India: Role of the Erg11 and Fks1 genes in azole and echinocandin resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 73:891–899. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ostrowsky B, Greenko J, Adams E, Quinn M, O’Brien B, Chaturvedi V, Berkow E, Vallabhaneni S, Forsberg K, Chaturvedi S, Lutterloh E, Blog D, C. auris Investigation Work Group . 2020. Candida auris isolates resistant to three classes of antifungal medications - New York, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69:6–9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6901a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cortegiani A, Misseri G, Fasciana T, Giammanco A, Giarratano A, Chowdhary A. 2018. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, resistance, and treatment of infections by Candida auris J Intensive Care 6:69. doi: 10.1186/s40560-018-0342-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pammi M, Holland L, Butler G, Gacser A, Bliss JM. 2013. Candida parapsilosis is a significant neonatal pathogen: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 32:e206–16. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182863a1c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garcia-Bustos V, Salavert M, Ruiz-Gaitán AC, Cabañero-Navalon MD, Sigona-Giangreco IA, Pemán J. 2020. A clinical predictive model of Candidaemia by Candida auris in previously colonized critically ill patients. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 26:1507–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huang X, Welsh RM, Deming C, Proctor DM, Thomas PJ, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program, Gussin GM, Huang SS, Kong HH, Bentz ML, Vallabhaneni S, Chiller T, Jackson BR, Forsberg K, Conlan S, Litvintseva AP, Segre JA, Young VB. 2021. Skin Metagenomic sequence analysis of early Candida auris outbreaks in U.S. mSphere 6. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00287-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Proctor DM, Dangana T, Sexton DJ, Fukuda C, Yelin RD, Stanley M, Bell PB, Baskaran S, Deming C, Chen Q, Conlan S, Park M, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program, Mullikin J, Thomas J, Young A, Bouffard G, Barnabas B, Brooks S, Han J, Ho S, Kim J, Legaspi R, Maduro Q, Marfani H, Montemayor C, Riebow N, Schandler K, Schmidt B, Sison C, Stantripop M, Black S, Dekhtyar M, Masiello C, McDowell J, Thomas P, Vemulapalli M, Welsh RM, Vallabhaneni S, Chiller T, Forsberg K, Black SR, Pacilli M, Kong HH, Lin MY, Schoeny ME, Litvintseva AP, Segre JA, Hayden MK. 2021. Integrated genomic, epidemiologic investigation of Candida auris skin colonization in a skilled nursing facility. Nat Med 27:1401–1409. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01383-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Netea MG, Joosten LAB, van der Meer JWM, Kullberg B-J, van de Veerdonk FL. 2015. Immune defence against Candida fungal infections. Nat Rev Immunol 15:630–642. doi: 10.1038/nri3897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Erwig LP, Gow NARR. 2016. Interactions of fungal pathogens with phagocytes. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:163–176. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smith LM, May RC. 2013. Mechanisms of microbial escape from phagocyte killing. Biochem Soc Trans 41:475–490. doi: 10.1042/BST20130014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pountain AW, Collette JR, Farrell WM, Lorenz MC, Goldman GH. 2021. Interactions of both pathogenic and nonpathogenic CUG clade Candida species with macrophages share a conserved transcriptional landscape. mBio 12:e0331721. doi: 10.1128/mbio.03317-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gilbert AS, Wheeler RT, May RC. 2014. Fungal pathogens: survival and replication within macrophages. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 5:a019661. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lorenz MC, Bender J, Fink GR. 2004. Transcriptional response of Candida albicans upon internalization by macrophages transcriptional response of Candida albicans upon internalization by macrophages. Eukaryot Cell 3:1076–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Slesiona S, Gressler M, Mihlan M, Zaehle C, Schaller M, Barz D, Hube B, Jacobsen ID, Brock M. 2012. Persistence versus escape: aspergillus Terreus and aspergillus fumigatus employ different strategies during interactions with macrophages. PLoS One 7:e31223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kasper L, Seider K, Gerwien F, Allert S, Brunke S, Schwarzmüller T, Ames L, Zubiria-Barrera C, Mansour MK, Becken U, Barz D, Vyas JM, Reiling N, Haas A, Haynes K, Kuchler K, Hube B. 2014. Identification of Candida glabrata genes involved in pH modulation and modification of the phagosomal environment in macrophages. PLoS One 9:e96015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tucker SC, Casadevall A.. 2002. Replication of cryptococcus neoformans in macrophages is accompanied by phagosomal permeabilization and accumulation of vesicles containing polysaccharide in the cytoplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:3165–3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fradin C, De Groot P, MacCallum D, Schaller M, Klis F, Odds FC, Hube B. 2005. Granulocytes govern the transcriptional response, morphology and proliferation of Candida albicans in human blood. Mol Microbiol 56:397–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04557.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weerasinghe H, Simm C, Djajawi TM, Tedja I, Lo TL, Simpson DS, Shasha D, Mizrahi N, Olivier FAB, Speir M, Lawlor KE, Ben-Ami R, Traven A. 2023. Candida auris uses metabolic strategies to escape and kill macrophages while avoiding robust activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome response. Cell Reports 42:112522. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miramón P, Lorenz MC. 2017. A feast for candida: metabolic plasticity confers an edge for virulence. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006144. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Frohner IE, Bourgeois C, Yatsyk K, Majer O, Kuchler K. 2009. Candida albicans cell surface superoxide dismutases degrade host-derived reactive oxygen species to escape innate immune surveillance. Mol Microbiol 71:240–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06528.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wysong DR, Christin L, Sugar AM, Robbins PW, Diamond RD. 1998. Cloning and sequencing of a Candida albicans catalase gene and effects of disruption of this gene. Infect Immun 66:1953–1961. doi: 10.1128/IAI.66.5.1953-1961.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hromatka BS, Noble SM, Johnson AD. 2005. Transcriptional response of Candida albicans to nitric oxide and the role of the Yhb1 gene in nitrosative stress and virulence. Mol Biol Cell 16:4814–4826. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e05-05-0435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Inglis DO, Voorhies M, Hocking Murray DR, Sil A. 2013. Comparative transcriptomics of infectious spores from the fungal pathogen histoplasma capsulatum reveals a core set of transcripts that specify infectious and pathogenic states. Eukaryot Cell 12:828–852. doi: 10.1128/EC.00069-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Seider K, Brunke S, Schild L, Jablonowski N, Wilson D, Majer O, Barz D, Haas A, Kuchler K, Schaller M, Hube B. 2011. The facultative intracellular pathogen Candida glabrata subverts macrophage cytokine production and phagolysosome maturation. J Immunol 187:3072–3086. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fan S, Yue H, Zheng Q, Bing J, Tian S, Chen J, Ennis CL, Nobile CJ, Huang G, Du H. 2021. Filamentous growth is a general feature of Candida auris clinical isolates. Med Mycol 59:734–740. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myaa116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yue H, Bing J, Zheng Q, Zhang Y, Hu T, Du H, Wang H, Huang G. 2018. Filamentation in Candida auris, an emerging fungal pathogen of humans: passage through the mammalian body induces a heritable phenotypic switch. Emerg Microbes Infect 7:188. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0187-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bravo Ruiz G, Ross ZK, Gow NAR, Lorenz A. 2020. Pseudohyphal growth of the emerging pathogen Candida auris is triggered by genotoxic stress through the S phase checkpoint. mSphere 5:e00151-20. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00151-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Muñoz JF, Gade L, Chow NA, Loparev VN, Juieng P, Berkow EL, Farrer RA, Litvintseva AP, Cuomo CA. 2018. Genomic insights into multidrug-resistance, mating and virulence in Candida auris and related emerging species. Nat Commun 9:5346. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07779-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hube B, Stehr F, Bossenz M, Mazur A, Kretschmar M, Schäfer W. 2000. Secreted Lipases of Candida albicans: cloning, characterisation and expression analysis of a new gene family with at least ten members. Arch Microbiol 174:362–374. doi: 10.1007/s002030000218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schaller M, Borelli C, Korting HC, Hube B. 2005. Hydrolytic enzymes as virulence factors of Candida albicans. Mycoses 48:365–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2005.01165.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reuss O, Morschhäuser J. 2006. A family of oligopeptide transporters is required for growth of Candida albicans on proteins. Mol Microbiol 60:795–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05136.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Martínez P, Ljungdahl PO. 2005. Divergence of Stp1 and Stp2 transcription factors in Candida albicans places virulence factors required for proper nutrient acquisition under amino acid control. Mol Cell Biol 25:9435–9446. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9435-9446.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miramón P, Lorenz MC. 2016. The SPS amino acid sensor mediates nutrient acquisition and immune evasion in Candida albicans. Cell Microbiol 18:1611–1624. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Garbe E, Miramón P, Gerwien F, Ueberschaar N, Hansske-Braun L, Brandt P, Böttcher B, Lorenz M, Vylkova S. 2022. Gnp2 encodes a high-specificity proline permease in Candida albicans. mBio 13:e0314221. doi: 10.1128/mbio.03142-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vylkova S, Lorenz MC. 2017. Phagosomal neutralization by the fungal pathogen Candida albicans induces macrophage pyroptosis. Infect Immun 85:1–14. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00832-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. 2005. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson K-F, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J, Puigserver P, Carlsson E, Ridderstråle M, Laurila E, Houstis N, Daly MJ, Patterson N, Mesirov JP, Golub TR, Tamayo P, Spiegelman B, Lander ES, Hirschhorn JN, Altshuler D, Groop LC. 2003. PGC-1Alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet 34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Maguire SL, ÓhÉigeartaigh SS, Byrne KP, Schröder MS, O’Gaora P, Wolfe KH, Butler G. 2013. Comparative genome analysis and gene finding in Candida species using CGOB. Mol Biol Evol 30:1281–1291. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Allert S, Schulz D, Kämmer P, Großmann P, Wolf T, Schäuble S, Panagiotou G, Brunke S, Hube B. 2022. From environmental adaptation to host survival: attributes that mediate pathogenicity of Candida auris Virulence 13:191–214. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2022.2026037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Johnson CJ, Davis JM, Huttenlocher A, Kernien JF, Nett JE. 2018. Emerging fungal pathogen Candida auris evades neutrophil attack. mBio 9:e01403-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01403-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bruno M, Kersten S, Bain JM, Jaeger M, Rosati D, Kruppa MD, Lowman DW, Rice PJ, Graves B, Ma Z, Jiao YN, Chowdhary A, Renieris G, van de Veerdonk FL, Kullberg B-J, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Hoischen A, Gow NAR, Brown AJP, Meis JF, Williams DL, Netea MG. 2020. Transcriptional and functional insights into the host immune response against the emerging fungal pathogen Candida auris. Nat Microbiol 5:1516–1531. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0780-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang Y, Zou Y, Chen X, Li H, Yin Z, Zhang B, Xu Y, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Huang X, Yang W, Xu C, Jiang T, Tang Q, Zhou Z, Ji Y, Liu Y, Hu L, Zhou J, Zhou Y, Zhao J, Liu N, Huang G, Chang H, Fang W, Chen C, Zhou D. 2022. Innate immune responses against the fungal pathogen Candida auris. Nat Commun 13:3553. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31201-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Horton MV, Johnson CJ, Zarnowski R, Andes BD, Schoen TJ, Kernien JF, Lowman D, Kruppa MD, Ma Z, Williams DL, Huttenlocher A, Nett JE. 2021. Candida auris cell wall mannosylation contributes to neutrophil evasion through pathways divergent from Candida albicans and Candida glabrata. mSphere 6:e0040621. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00406-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Uwamahoro N, Verma-Gaur J, Shen H-H, Qu Y, Lewis R, Lu J, Bambery K, Masters SL, Vince JE, Naderer T, Traven A. 2014. The pathogen Candida albicans hijacks pyroptosis for escape from macrophages. mBio 5:e00003–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00003-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wellington M, Koselny K, Sutterwala FS, Krysan DJ. 2014. Candida albicans triggers Nlrp3-mediated pyroptosis in macrophages. Eukaryot Cell 13:329–340. doi: 10.1128/EC.00336-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Basso P, Dang EV, Urisman A, Cowen LE, Madhani HD, Noble SM. 2022. Deep tissue infection by an invasive human fungal pathogen requires lipid-based suppression of the IL-17 response. Cell Host Microbe 30:1589–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2022.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zaragoza O, Chrisman CJ, Castelli MV, Frases S, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodríguez-Tudela JL, Casadevall A. 2008. Capsule enlargement in cryptococcus neoformans confers resistance to oxidative stress suggesting a mechanism for intracellular survival. Cell Microbiol 10:2043–2057. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01186.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang Y, Aisen P, Casadevall A. 1995. Cryptococcus neoformans melanin and virulence: mechanism of action. Infect Immun 63:3131–3136. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3131-3136.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. de Jesús-Berríos M, Liu L, Nussbaum JC, Cox GM, Stamler JS, Heitman J. 2003. Enzymes that counteract nitrosative stress promote fungal virulence. Curr Biol 13:1963–1968. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Miramón P, Dunker C, Windecker H, Bohovych IM, Brown AJP, Kurzai O, Hube B. 2012. Cellular responses of Candida albicans to Phagocytosis and the extracellular activities of neutrophils are critical to counteract carbohydrate starvation, oxidative and Nitrosative stress. PLoS One 7:e52850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Eissenberg LG, Goldman WE, Schlesinger PH. 1993. Histoplasma capsulatum modulates the acidification of phagolysosomes. J Exp Med 177:1605–1611. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Heymann P, Gerads M, Schaller M, Dromer F, Winkelmann G, Ernst JF. 2002. The siderophore iron transporter of Candida albicans (Sit1P/Arn1P) mediates uptake of ferrichrome-type siderophores and is required for epithelial invasion. Infect Immun 70:5246–5255. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.5246-5255.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ramírez MA, Lorenz MC. 2007. Mutations in alternative carbon utilization pathways in Candida albicans attenuate virulence and confer pleiotropic phenotypes. Eukaryot Cell 6:280–290. doi: 10.1128/EC.00372-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lorenz MC, Fink GR. 2001. The glyoxylate cycle is required for fungal virulence. Nature 412:83–86. doi: 10.1038/35083594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Williams RB, Lorenz MC. 2020. Multiple alternative carbon pathways combine to promote candida albicans stress resistance, immune interactions, and virulence. mBio 11:e03070-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03070-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Barelle CJ, Priest CL, Maccallum DM, Gow NAR, Odds FC, Brown AJP. 2006. Niche-specific regulation of central metabolic pathways in a fungal pathogen. Cell Microbiol 8:961–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00676.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wilson HB, Lorenz MC. 2023. Candida albicans hyphal morphogenesis within macrophages does not require carbon dioxide or pH-sensing pathways. Infect Immun 91:e0008723. doi: 10.1128/iai.00087-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Vylkova S, Carman AJ, Danhof HA, Collette JR, Zhou H, Lorenz MC, Taylor JW. 2011. The fungal pathogen Candida albicans autoinduces hyphal morphogenesis by raising extracellular pH. mBio 2:00055-11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00055-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vylkova S, Lorenz MC. 2014. Modulation of phagosomal pH by Candida albicans promotes hyphal morphogenesis and requires Stp2P, a regulator of amino acid transport. PLoS Pathog 10:e1003995. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kasper L, König A, Koenig P-A, Gresnigt MS, Westman J, Drummond RA, Lionakis MS, Groß O, Ruland J, Naglik JR, Hube B. 2018. The fungal peptide toxin candidalysin activates the Nlrp3 Inflammasome and causes cytolysis in mononuclear phagocytes. Nat Commun 9:4260. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06607-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Olivier FAB, Hilsenstein V, Weerasinghe H, Weir A, Hughes S, Crawford S, Vince JE, Hickey MJ, Traven A. 2022. The escape of Candida albicans from macrophages is enabled by the fungal toxin candidalysin and two host cell death pathways. Cell Rep 40:111374. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ding X, Kambara H, Guo R, Kanneganti A, Acosta-Zaldívar M, Li J, Liu F, Bei T, Qi W, Xie X, Han W, Liu N, Zhang C, Zhang X, Yu H, Zhao L, Ma F, Köhler JR, Luo HR. 2021. Inflammasome-mediated GSDMD activation facilitates escape of Candida albicans from macrophages. Nat Commun 12:6699. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27034-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gillum AM, Tsay EY, Kirsch DR. 1984. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5’-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol Gen Genet 198:179–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00328721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Santana DJ, O’Meara TR. 2021. Forward and reverse genetic dissection of morphogenesis identifies filament-competent Candida auris strains. Nat Commun 12:7197. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27545-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Liu Z, Chen O, Wall JBJ, Zheng M, Zhou Y, Wang L, Ruth Vaseghi H, Qian L, Liu J. 2017. Systematic comparison of 2A peptides for cloning multi-genes in a polycistronic vector. Sci Rep 7:2193. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02460-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Aitken SJ, Anderson CJ, Connor F, Pich O, Sundaram V, Feig C, Rayner TF, Lukk M, Aitken S, Luft J, Kentepozidou E, Arnedo-Pac C, Beentjes SV, Davies SE, Drews RM, Ewing A, Kaiser VB, Khamseh A, López-Arribillaga E, Redmond AM, Santoyo-Lopez J, Sentís I, Talmane L, Yates AD, Liver Cancer Evolution Consortium, Semple CA, López-Bigas N, Flicek P, Odom DT, Taylor MS. 2020. Pervasive lesion segregation shapes cancer genome evolution. Nature 583:265–270. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2435-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL. 2019. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol 37:907–915. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Amos B, Aurrecoechea C, Barba M, Barreto A, Basenko EY, Bażant W, Belnap R, Blevins AS, Böhme U, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Caddick M, Callan D, Campbell L, Christensen MB, Christophides GK, Crouch K, Davis K, DeBarry J, Doherty R, Duan Y, Dunn M, Falke D, Fisher S, Flicek P, Fox B, Gajria B, Giraldo-Calderón GI, Harb OS, Harper E, Hertz-Fowler C, Hickman MJ, Howington C, Hu S, Humphrey J, Iodice J, Jones A, Judkins J, Kelly SA, Kissinger JC, Kwon DK, Lamoureux K, Lawson D, Li W, Lies K, Lodha D, Long J, MacCallum RM, Maslen G, McDowell MA, Nabrzyski J, Roos DS, Rund SSC, Schulman SW, Shanmugasundram A, Sitnik V, Spruill D, Starns D, Stoeckert CJ, Tomko SS, Wang H, Warrenfeltz S, Wieck R, Wilkinson PA, Xu L, Zheng J. 2022. Veupathdb: the eukaryotic pathogen, vector and host bioinformatics resource center. Nucleic Acids Res 50:D898–D911. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA, Kingsford C. 2017. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat Methods 14:417–419. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-Seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zhu A, Ibrahim JG, Love MI. 2018. Heavy-tailed prior distributions for sequence count data: removing the noise and preserving large differences. Bioinformatics. doi: 10.1101/303255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76. Skrzypek MS, Binkley J, Binkley G, Miyasato SR, Simison M, Sherlock G. 2017. The Candida genome database (CGD): incorporation of assembly 22, systematic Identifiers and visualization of high throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D592–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Fitzpatrick DA, O’Gaora P, Byrne KP, Butler G. 2010. Analysis of gene evolution and metabolic pathways using the Candida gene order browser. BMC Genomics 11:290. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Macrophages uptake C. auris.

The C. auris response correlates with that of other Candida species.

C. auris-specific genes without a C. albicans BLAST hit are shorter and lower-expressed.

Differential expression analysis and phagocytosis-induced genes.

Legends of Fig. S1 to S3, Videos S1 and S2, and Tables S1 and S2.

Time lapse microscopy of GFP-labeled C. auris CaPM480 infecting J774A.1 macrophages.

Time lapse microscopy of mCherry-labeled C. auris CaPM486 infecting J774A.1 macrophages.