Abstract

In their seminal description of magnetic field effects on chemiluminescent fluid solutions, Atkins and Evans considered the spin-dependent interactions between two triplets, incorporating the effects of the diffusion of the molecules in the liquid phase. Their results, crucial for the advancement of photochemical upconversion, have received renewed attention due to the increasing interest in triplet–triplet annihilation for photovoltaic and optoelectronic applications. Here we revisit their approach, using a modern formulation of open quantum system dynamics and extend their results. We provide corrections to the theory of the magnetic field response of the fluorescent triplet pair state with singlet multiplicity. These corrections are timely, as improvements in the precision and range of available experimental methods are supported by the determination of quantitatively accurate rotational and interaction model parameters. We then extend Atkins and Evans’ theory to obtain the magnetic field response of triplet pair states with triplet and quintet multiplicity. Although these states are not optically active, transitions between them are becoming imperative to study the working mechanism of spin-mediated upconversion and downconversion processes, thanks to advances in electron spin resonance and time-resolved transient absorption spectroscopy.

Introduction

In triplet–triplet annihilation (TTA) upconversion, two low energy photons are effectively converted into one higher energy photon, via a process involving the electronic states of host molecules.1,2 In summary, two host molecules are promoted to their excited triplet (spin–1) states via the absorption of a photon. This can happen directly, via intersystem crossing from an optically active singlet state, or indirectly, via energy transfer from a sensitizer molecule.3 The host molecules may then pool their energy, allowing one molecule to reach its fluorescent singlet state and emit a photon of energy higher than that of the absorbed photon. Molecular singlet and triplet states have distinct spin characteristics, with interactions governed by spin selection rules, making TTA upconversion a spin-mediated process.4,5 As spin effects are magnetic in nature, they respond to the application of magnetic fields.6 Hence, experimentally, investigation of the magnetic field response of TTA upconversion is an important means of both interrogating and understanding the underlying quantum mechanical mechanisms,7 and to thereby optimize upconversion processes.8,9

In 1975, Atkins and Evans (A&E) published a seminal theory of TTA upconversion in solution,10 providing a mathematical description of the dependence of the upconverted fluorescence intensity on magnetic field strength in chemiluminescent reactions in liquids. Their theory has been utilized and validated by theorists11,12 and experimentalists13,14 alike across the decades. A practical demonstration of upconversion by sunlight (rather than a laser source) at the beginning of this century15 and a recent demonstration of upconversion from below the silicon band gap16 have reignited interest in TTA upconversion as a potential mechanism to overcome the detailed-balance efficiency limit of standard silicon-based cells.17 Other diverse applications include optoelectronics,18,19 bioimaging,20 and photodynamic therapy.21

Interestingly, this renewed attention to Atkins and Evans’ theory has led to the identification of a few issues with the original formulation of the theory and prompted its revision. Besides minor typographic errors, there are some conceptual issues with the density operator master equations and initial state assumptions. Furthermore, the mathematical formalism used by Atkins and Evans is at times hard to parse when compared to the modern formulation of open quantum systems dynamics. Though many of these discrepancies have gone unnoticed in the past, the improved precision of modern experimental techniques demands a more precise theory with quantitative predictive power.

To this end, we review the original A&E theory using a modern formulation of open quantum systems dynamics. We recast the original results and present new solutions associated with the dynamics of other spin states and multiplicities. In the original formulation, the model is developed for both triplet–triplet upconversion and also triplet quenching in doublet–triplet interactions. We explicitly consider the triplet–triplet case, as this is of direct interest to modern experiments, but for completeness, we also present the equivalent doublet–triplet results in the Supporting Information. Our results are in closed-form and expressed as a function of the initial state, local decoherence, and roto-diffusional coefficients, allowing the quantitative estimation of these parameters. Here we show that our corrections lead to significantly different results for the quantitative estimation of model parameters like translational correlation times.

Theory of TTA-Upconversion in Solution

In TTA-annihilation upconversion, molecules are promoted to their triplet states by each absorbing a low energy photon. Two of these excited molecules may collide and undergo energy exchange to pool their combined energy on one of the two molecules, exciting it to its fluorescent singlet state. This molecule may then emit a photon of higher energy than the original irradiating photons, resulting in upconversion.

As the singlet and triplet spin states have different spin angular momenta, they behave differently in magnetic fields. It is this magnetic field dependence of TTA-upconversion intensity that Atkins and Evans describe.10 While other authors had observed a diminishing fluorescence intensity with applied magnetic field22 and developed theory to describe it in the solid state,23 Atkins and Evans’ theory of the magnetic field effect in TTA-upconversion was the first to consider the liquid phase by incorporating rotational and translational diffusion.10

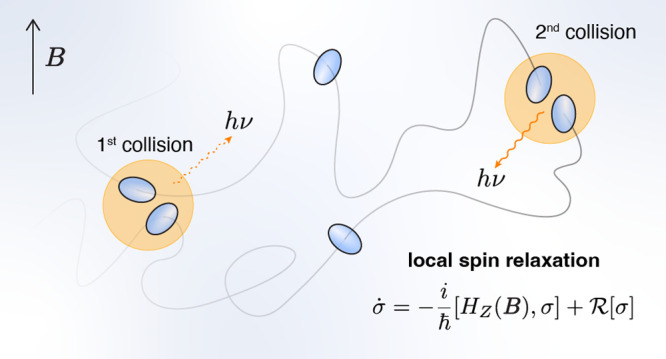

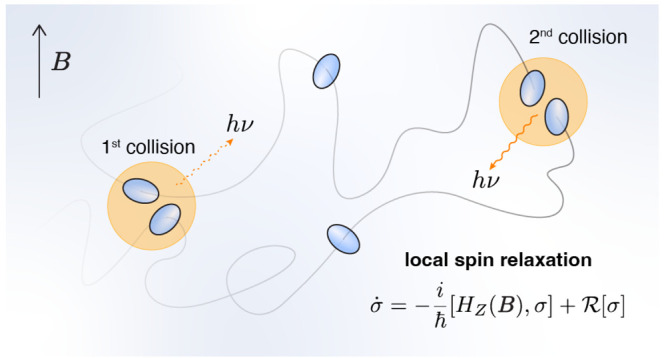

In Atkins and Evans’ model (Figure 1), two rotating triplet molecules undergo a first collision in the presence of a magnetic field B. The two triplets may, with some probability of λ, populate the overall singlet state of the pair and emit an upconverted photon. This effectively removes the singlet pair state contribution from the initial triplet pair immediately after the initial collision. The two triplets are then free to diffuse individually, and the spin state of each will evolve independently in response to the zero-field splitting parameters of the rotating molecules in the presence of the magnetic field, and through local spin relaxation induced by the Zeeman effect. Taking a random walk approach, the two diffusing triplet molecules may undergo a second collision. Again, the overall singlet state of this pair may be populated with the probability λ, leading to fluorescence. However, the local spin relaxation of the diffusing triplets in the presence of the magnetic field will alter the populations of the individual triplet spin states, and therefore also the populations of the overall spin pair state. The parameters in the model affecting these populations, and thereby determining the magnetic field effect in each pair state spin manifold, are the magnetic field strength, B, and rotational and translational correlation times, τr and τa respectively.

Figure 1.

Atkins

and Evans’ Upconversion Process. Two rotating triplet

molecules undergo a first collision in the presence of a magnetic

field B, and if the overall singlet

state of the pair is populated, may emit an upconverted photon of

energy hν. If a photon is not emitted, the

remaining two triplet molecules then drift apart, and the spin state

of each, σ, evolves under a local spin relaxation caused by

the Zeeman Hamiltonian, HZ(B), and molecular zero-field splitting parameters

of the Redfield term,  . The diffusing

triplet molecules may then

undergo a second collision. The population of the overall singlet

state of this pair, and hence probability of upconversion, depends

on the strength of the magnetic field and the rotational and translational

correlation times.

. The diffusing

triplet molecules may then

undergo a second collision. The population of the overall singlet

state of this pair, and hence probability of upconversion, depends

on the strength of the magnetic field and the rotational and translational

correlation times.

The upconversion photoluminescence intensity arises from fluorescence and is therefore proportional to the population of the singlet manifold. Hence, our goal is to study the pair state singlet population (for long times) as a function of the applied magnetic field. The singlet population is also affected by the local spin relaxation processes induced by the rotational and translational diffusion of the molecules hosting the triplets.

The Triplet Hamiltonian

As an individual triplet molecule tumbles in the presence of a magnetic field, a Zeeman term and a zero-field splitting term contribute to its energy fluctuations in time. The local Hamiltonian operator, H, for the triplet molecule is accordingly comprised of a Zeeman term, HZ, and a zero-field splitting term, Hzfs

| 1 |

The Zeeman term is given by

| 2 |

with g the electron g-factor, μB the Bohr magneton, ℏ the reduced Planck’s constant, B the magnetic field vector, and S the spin angular momentum operator of the triplet with standard laboratory frame (x, y, z) components,

| 3 |

The zero-field splitting component of the individual triplet Hamiltonian accounts for the anisotropic distribution of the molecule’s electron cloud and is given by

| 4 |

with D and E the molecular zero-field splitting parameters for the triplet molecule.

The overlap of electronic orbitals gives rise to the exchange interaction. As this is a short-range interaction (<1 nm),24 it is only relevant during collisions, and allows the exchange of energy between two colliding triplet molecules. Thus, the exchange interaction determines the probability (or rate) with which colliding triplets annihilate to form optically active singlets. In this work, as in the original A&E model, the probability of energy exchange between the two colliding triplets is represented by the coarse-grained parameter, λ. Conversely, when the two molecules are spatially separated, we assume the strength of the exchange interaction to be negligible with respect to the other characteristic energies of the system. Similarly, the available thermal energy in fluid solution at room temperature is so much larger than the energy spacing between triplet sublevels (kBT ≃ 0.026 eV at T = 300 K, where kB is the Boltzmann constant) that thermal effects and temperature dependence need not be considered in this model.

Bases for Uncoupled versus Interacting Triplet Pairs

To describe the spin-mediated TTA upconversion process, we use two bases: one describing the independent diffusing triplets and one describing the interacting triplet pair. For an uncoupled triplet exciton, with quantum numbers s = 1 and m = −1, 0, 1 (abbreviated to −, 0, +), the Zeeman Hamiltonian defines a local basis |m⟩ := |1, m⟩. We choose to align the magnetic field B = Bẑ, with unit vector ẑ oriented along the z direction in the lab frame so that

| 5 |

We can then obtain a local basis for the two-triplet system by performing the Kronecker product of each individual triplet’s spin state, |m1m2⟩ := |m⟩1⊗|m⟩2.

The second basis used is that of the interacting triplets, defined by the common eigenstates of S(1)z + S(2)z and S1 · S2, with quantum numbers S = 0, 1, 2 and – S ≤ M ≤ S. The states |S,M⟩ form the basis we use to define the singlet, triplet, and quintet pair states and to construct the projection operators that describe the reaction of two triplets undergoing upconversion.

The transformation between the (m1, m2) and (S, M) bases is conducted via Clebsch–Gordan coefficients. For example, the singlet pair state, with S = 0 and M = 0, is given by

| 6 |

The remaining Clebsch–Gordan transformations are summarized in the unitary operator U, where mi (i = 1, 2) number ordering runs as −, 0, + and the |S,M⟩ state ordering runs through singlet, triplet, and quintet states, from lowest to highest M,

|

7 |

Throughout the paper, we represent the density operator of an individual triplet in the m-basis using σ, while we use ρ to represent the density operator of the triplet pair state. In the description of triplet relaxation, the individual triplet densities, σ, are first allowed to evolve under the action of the Hamiltonian operator. The interacting pair state densities, ρ, are then calculated to determine the fraction of singlets, triplets, and quintets in the evolved pair state manifold.

Triplet Relaxation

As the molecular host tumbles into the solution, triplets relax under stochastic fluctuations in the ZFS tensor. To calculate the effect of these fluctuations we use perturbation theory, where the ZFS term, Hzfs(t), is a small perturbation of the Zeeman interaction HZ

| 8 |

A second-order expansion in the perturbation allows us to express the dynamics of the density operator of an individual triplet with the following quantum master equation25−27

| 9 |

where  is the superoperator

associated with the

relaxation process in the m-basis, i.e. the basis

of the Zeeman Hamiltonian. Equation 9 can be expressed in this basis as

is the superoperator

associated with the

relaxation process in the m-basis, i.e. the basis

of the Zeeman Hamiltonian. Equation 9 can be expressed in this basis as

| 10 |

where σmm′ = ⟨m|σ|m′⟩, ωmm′ = gμBB(m – m′)/ℏ, and where Rmm′nn′ are the elements of the Redfield tensor, which are calculated from the properties of the perturbation Hamiltonian Hzfs(t). In general, the elements of the Redfield tensor are given by28

| 11 |

with

| 12 |

By solving eq 9 in the secular approximation for nondegenerate HZ the dynamics of populations and coherences of the triplets is decoupled. Furthermore, we assume memoryless rotational dynamics of the zero-field splitting Hamiltonian characterized by exponentially decaying correlations exp(−t/τr), leading to Lorentzian spectral densities

| 13 |

Since the spectral densities are symmetric in the transition energies ωmn, there are only five independent elements of the Redfield tensor to be calculated,

| 14 |

| 15 |

| 16 |

| 17 |

| 18 |

where the function k(ω) represents the spectral density for the considered transition as a function of the magnetic field, with D and E the molecular zero-field splitting parameters,

| 19 |

The longitudinal and transverse relaxation times, T1 and T2, relative to the z-direction, can be expressed in terms of elements of the Redfield tensor,

| 20 |

| 21 |

The rate of spin-bath relaxation of the system as it approaches equilibrium is described by T1, while T2 relates to the decay of transverse magnetization. It is the interplay of these time scales with those of the rotational and translational correlation times for a given set of zero-field splitting parameters that give rise to the magnetic field effect. Here, as in A&E,10 we also assume isotropic rotational diffusion so that the rotational correlation time, τr, may be expressed in terms of the diffusion coefficient, Ddiff,

| 22 |

and related to the translational correlation time, τa, through

| 23 |

It is worth noting that the spectral density eq 19 can be generalized to capture the effect of temperature depending on the properties of the environment interacting with the triplet states.29 This typically leads to a detailed balance condition k(ω, T)/k(−ω, T) = exp(−ω/kBT), where here kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the temperature of the medium.25 In this case, there are more than five independent elements in the Redfield tensor, since the symmetry in the transitions n → m is lost. However, at room temperature T ≈ 300 K, the thermal energy kBT ≫ ωmn is much larger that the typical separation between spin sublevels, restoring the symmetry in the transitions, k(ω) = k(−ω).

Solution of the Triplet Relaxation

By combining eq 10 with the expressions 14 and 18 for the elements of the Redfield tensor, we obtain the prescription for the dynamics of the density operator σ of an individual triplet. The populations evolve according to

|

24 |

while the coherences evolve according to

| 25 |

and

| 26 |

These sets of coupled differential equations can be solved analytically to give the following solutions:

|

27 |

| 28 |

| 29 |

The remaining matrix elements are then obtained

from the Hermitian conjugation relation  .

.

Collisions and Initial Triplet–Triplet State

Before the first collision each triplet is assumed to be completely relaxed, i.e., such that each spin sublevel is equally probable,

| 30 |

which can be expressed in the m-basis notation as σmm′ = δmm′/3. As mentioned above, we consider pairs of triplets that collide and react via the singlet state of the correlated basis (S, M) with some probability λ. As in the original A&E model, the state of the pair before the collision is

| 31 |

During the upconversion reaction, the singlet state |0,0⟩ of the correlated basis (S, M) is lost to radiative emission with probability λ. To represent this we use the projection operator Π0 onto the singlet manifold

| 32 |

and construct the non-trace preserving map Λ:

| 33 |

In the (m1, m2) notation, the projection Π0 reads

|

34 |

The state ρ(0+) after the collision is then given by

| 35 |

| 36 |

that can be expressed in the local basis (m1, m2) as

| 37 |

This formulation of state ρ(0+) in eqs 35 and 36 resolves a conceptual issue that was present in the original A&E formulation,10 where it was incorrectly expressed as a tensor product between two individual triplet states, σ(0+) ⊗ σ(0+). State ρ(0+) of eq 36 is correlated (entangled) and thus cannot be expressed as a probability distribution over product states. Finally, we also notice that this state is not normalized, but normalization can be performed via ρ(0+)/Trρ(0+), and since we are interested in relative changes in the population, the renormalization factors eventually cancel out.

Time-Evolution and Singlet Manifolds

The initial triplet pair state of eq 36 is propagated using

|

38 |

where  is the map that propagates a triplet

operator

by some time t, as prescribed by eqs 27–29. After obtaining the density matrix of the triplet pair in the (m1, m2) basis, we

can transform it into the (S, M)

basis via the unitary transformation defined in eq 7

is the map that propagates a triplet

operator

by some time t, as prescribed by eqs 27–29. After obtaining the density matrix of the triplet pair in the (m1, m2) basis, we

can transform it into the (S, M)

basis via the unitary transformation defined in eq 7

| 39 |

We are interested in the dependence of the singlet population as a function of time, which can be calculated from the state ρ(t) as

| 40 |

for the singlets, where Π0 was introduced in eq 32. Similarly for triplet and quintet populations,

| 41 |

| 42 |

with respective projection operators

| 43 |

and

| 44 |

Translational Motion and Probability of Subsequent Encounters

The final step is to incorporate translational diffusion within the fluid via the translational correlation time, τa. A&E take a random walk approach by applying a convolution with probability distribution function G(t),

| 45 |

to the singlet, triplet, and quintet densities of eq 40 to eq 42 to obtain the magnetic field dependence (i.e., long-time behavior) of singlet, triplet, and quintet manifold populations in terms of the magnetic field strength B,

| 46 |

for X = 0, 1, 2 for singlet, triplet, and quintets, respectively.

The correlation integral is again simplified through a Laplace transform, noting that

| 47 |

to yield the final translated and rotated long-time populations in frequency space of each manifold, singlet, triplet, and quintet, where the Larmor frequency ω = gμB/ℏ incorporates the magnetic field dependence. Finally, the magnetic field effect for each manifold is reached by normalization with the population at zero magnetic field,

| 48 |

which is independent of the normalization of the initial state ρ(0+).

Results

The resulting expressions for the singlet, triplet and quintet populations in time are

| 49 |

| 50 |

| 51 |

The long-time behavior of the populations in terms of their magnetic field dependence is then given by applying eq 46:

|

52 |

|

53 |

|

54 |

It should be emphasized that these three equations, eqs 52 to 54, are all that is required to model magneto-photoluminescence (MPL) experimental results. The magnetic field dependence of the Redfield components in eqs 52 to 54 is omitted to conserve space. Note the signs in the argument of the final term of the singlet population eq 52, which are corrected here relative to eq (AE 3.25).10 The triplet and quintet populations, eqs 53 and 54, were not calculated in the original A&E theory, and are presented here for the first time.

The resulting magnetic field responses for each pair state multiplicity, for representative parameters λ = 0.25 and τa = 200 ps and molecular ZFS parameters for anthracene (D = 0.07156 cm–1 and E = −0.00844 cm–1),30 are shown in Figure 2. As expected, the singlet manifold response decreases with a magnetic field. Conversely, the triplet and quintet manifold responses increase with magnetic field, though the change is approximately one-tenth the magnitude of the singlet MFE.

Figure 2.

Triplet–triplet encounters: magnetic field response of singlet, triplet and quintet populations for typical parameters, λ = 0.25 and τa = 200 ps with anthracene ZFS parameters, D = 0.07156 cm–1 and E = −0.00844 cm–1.30

Comparison to the Original Atkins and Evans Theory

We are now ready to show how these corrections to Atkins and Evans’ theory lead to quantitatively different results. To this end, we compare the corrected MFE for the singlet manifold eq 52 to that as published in A&E’s original work eq 55, following eq (AE 3.24) and eq (AE 3.25).10

|

55 |

The signs are inverted in the argument of the final term of eq 55, relative to the corrected eq 52. As a consequence, the original A&E theory overpredicts the magnitude of the magnetic field effect in the pair state singlet manifold, and therefore in the upconversion photoluminescence. Figure 3 illustrates the magnitude of these corrections to the singlet manifold. For typical parameters (λ = 0.25 and τa = 200 ps), this results in a 7% overestimation of the maximum magnitude of the singlet manifold magnetic field effect. In practice, when experimental data are fitted using the original results of A&E, this discrepancy will result in a model that typically underestimates the translational correlation time τa by approximately 10%, and λ by 2%.

Figure 3.

Corrected versus original singlet MFE for λ = 0.25 and τa = 200 ps and anthracene ZFS parameters.

As an example, upconversion of near-infrared light from below the silicon band gap was demonstrated for the first time in ref (16). With the potential to enhance the efficiency of existing silicon photovoltaics as well as applications for in vivo drug delivery and biological imaging, these experiments have received wide interest. In the system of Gholizadeh et al.,16 TTA-upconversion was studied using TIPS–tetracene carboxylic acid ligated PbS nanocrystal sensitizers and Violanthrone-79 (V79) as the upconverting emitter. Their results included measurement of the diminishing magnetic field effect in the upconverted photoluminescence intensity. This experimental data were modeled through the original A&E theory eq 55 in ref (31). For comparison with the corrected pair state singlet population and the resulting magnetic field effect, Figure 4 illustrates the fitted V79 MFE experimental data. The corrected singlet MFE, of eq 52, and the original A&E expression, of eq 55, produce overlapping fits, but the update to the theory results in significant quantitative adjustments to the fit parameters: a 10% increase in translational correlation time of τa = 535 ± 28 ps (up from 486 ± 21 ps), and 1.8% increase in λ, the probability of colliding triplets reaching the pair state singlet manifold, with λ = 0.281 ± 0.009 (up from from 0.276 ± 0.009).

Figure 4.

Experimental data for upconverted fluorescence showing singlet MFE for PtOEP/V79 system as described in ref (16) and modeled in ref (31). The fits for the original and corrected equations overlap, but the correction to the theory results in a 10% increase in the estimate of the model parameter translational correlation time of τa = 535 ± 28 (up from 486 ± 21) ps and a 1.8% increase in probability of energy exchange within the pair, λ, with λ = 0.281 ± 0.009 (up from from 0.276 ± 0.009).

Discussion and Conclusions

The interplay of magnetic fields and singlet/triplet molecular spin-states physics is key to understanding multi-excitonic effects such as triplet–triplet annihilation and singlet fission. A&E theory is a surprisingly general and useful model for these processes in solution. However, as experiments have improved, the need for precise quantitative accuracy has become crucial.

In revisiting the original approach of A&E we have been able to provide a number of improvements to the original formulation including (i) a detailed rederivation using a more modern formulation of open-quantum systems theory, justifying all assumptions and correcting typographical errors in the original expressions (see Supporting Information), (ii) quantitative corrections to the magnetic field effect observed in triplet–triplet annihilation upconversion, (iii) an analytical description of the magnetic field response of triplet and quintet multiplicity pair states in triplet–triplet annihilation upconversion, and (iv) the magnetic field response of doublet and quartet pairs in doublet–triplet interactions (provided in the Supporting Information).

Although the original theory was explicitly concerned with the optical emission from triplet–triplet annihilation, by solving for all spin manifolds we provide general solutions that are more widely applicable. The solutions for triplet and quintet multiplicity pair states provide the magnetic field dependence for the population of the optically dark states which can be studied experimentally using electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy and time-resolved transient absorption spectroscopy. These approaches have been recently used to understand the pathways and intermediate states in singlet fission.32−35 In principle, our approach can be adapted to compute relevant time- and field-dependent population results for these types of experiments.

While A&E is well established in the literature as a seminal work on the theory of magnetic field effects on delayed fluorescence in solution, the only papers (by other groups) which explicitly apply the theory to experimental results are by Iwasaki et al.13 and Mani and Vinogradov.14 Iwasaki et al.13 investigate N,N,N′,N′–tetramethyl–1,4–phenylenediamine (TMPD) in mixed alcohol and 2-propanol, while Mani and Vinogradov14 apply A&E to perylene in DMF. These two publications use estimates of the rotational correlation time τr using the Stokes–Einstein–Debye relationship36 for solvent viscosity η,

| 56 |

and then fit for λ using the original A&E equations. This is in contrast to the computational method employed here and in earlier works by our group31,37 in which both A&E parameters are directly fitted to experimental data. The Stokes–Einstein approach is known to underestimate molecular radii, particularly for small molecules,38 and the estimated values of τr are correspondingly low, resulting in extremely high determinations of λ. This highlights the need for a model that can be used for the quantitative fitting of experimental results.

Understanding the role of spin–spin interactions and magnetic fields in photoactive molecules is key to their use in optical up-39 and down-conversion40,41 and information processing with excitons,42 among other applications. A&E theory is therefore notable in that it is a closed form model of magnetic field effects in solution that has shown a very high degree of quantitative agreement with experiment.

The approach detailed here can in principle be generalized to include multiple particle–particle encounters, larger spin multiplicity, or more sophisticated relaxation processes. Temperature dependence can also be included in both the relaxation terms and diffusion, which are experimentally relevant at high magnetic fields or low temperatures. The diffusion aspect of the model may also be adapted to excitonic diffusion in solid-state materials, which are of great interest for solar and lighting applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Australian Research Council (grant number CE170100026) for funding and the National Computational Infrastructure (NCI), supported by the Australian Government, for the computational resources. We also acknowledge useful conversations with T. W. Schmidt. F.C. acknowledges that results incorporated in this standard have received funding from the European Union Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Action for the project SpinSC.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jctc.3c00927.

The mathematical results for doublet–triplet relaxation and a detailed list of typographical errors in the original formulation can be found in the Supporting Information. (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Singh-Rachford T. N.; Castellano F. N. Photon Upconversion Based on Sensitized Triplet–Triplet Annihilation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010, 254, 2560–2573. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J.; Alves J.; de Clercq D. M.; Schmidt T. W. Photochemical Upconversion. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2023, 74, 145–168. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-092722-104952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turro N. J.; Ramamurthy V.; Scaiano J.. Modern Molecular Photochemistry of Organic Molecules; University Science Books: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Minaev B. F.; Ågren H. Spin–Catalysis Phenomena. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1996, 57, 519–532. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao X.; Luan L.; Liu Y.; Yu Z.; Hu B. Inter–Triplet Spin–Spin Interaction Effects on Inter–Conversion Between Different Spin States in Intermediate Triplet–Triplet Pairs Towards Singlet Fission. Org. Electron. 2014, 15, 2168–2172. 10.1016/j.orgel.2014.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner U. E.; Ulrich T. Magnetic Field Effects in Chemical Kinetics and Related Phenomena. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 51–147. 10.1021/cr00091a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. C.; Merrifield R. E. Effects of Magnetic Fields on the Mutual Annihilation of Triplet Excitons in Anthracene Crystals. Phys. Rev. B 1970, 1, 896–902. 10.1103/PhysRevB.1.896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y. Y.; Khoury T.; Clady R. G. C. R.; Tayebjee M. J. Y.; Ekins-Daukes N. J.; Crossley M. J.; Schmidt T. W. On the Efficiency Limit of Triplet–Triplet Annihilation for Photochemical Upconversion. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 66–71. 10.1039/B913243K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T. W.; Castellano F. N. Photochemical Upconversion: The Primacy of Kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 4062–4072. 10.1021/jz501799m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins P.; Evans G. Magnetic Field Effects on Chemiluminescent Fluid Solutions. Mol. Phys. 1975, 29, 921–935. 10.1080/00268977500100801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benk H.; Sixl H. Theory of Two Coupled Triplet States. Mol. Phys. 1981, 42, 779–801. 10.1080/00268978100100631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulten K. Ensemble Averaged Spin Pair Dynamics of Doublet and Triplet Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 80, 3668–3679. 10.1063/1.447189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki Y.; Maeda K.; Murai H. Time–Domain Observation of External Magnetic Field Effects on the Delayed Fluorescence of N,N,N’,N’–Tetramethyl–1,4–Phenylenediamine in Alcoholic Solution. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 2961–2966. 10.1021/jp002029v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mani T.; Vinogradov S. A. Magnetic Field Effects on Triplet–Triplet Annihilation in Solutions: Modulation of Visible/NIR Luminescence. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 2799–2804. 10.1021/jz401342b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluschev S.; Miteva T.; Yakutkin V.; Nelles G.; Yasuda A.; Wegner G. Up-Conversion Fluorescence: Noncoherent Excitation by Sunlight. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 143903. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.143903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholizadeh E. M.; Prasad S. K. K.; Teh Z. L.; Ishwara T.; Norman S.; Petty A. J.; Cole J. H.; Cheong S.; Tilley R. D.; Anthony J. E.; et al. Photochemical Upconversion of Near–Infrared Light from Below the Silicon Bandgap. Nat. Photonics 2020, 14, 585–590. 10.1038/s41566-020-0664-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tayebjee M. J.; McCamey D. R.; Schmidt T. W. Beyond Shockley–Queisser: Molecular Approaches to High–Efficiency Photovoltaics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 2367–2378. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray V.; Dzebo D.; Abrahamsson M.; Albinsson B.; Moth-Poulsen K. Triplet–Triplet Annihilation Photon–Upconversion: Towards Solar Energy Applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 10345–10352. 10.1039/C4CP00744A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrini J.; Monguzzi A. Recent Advances in the Application Triplet–Triplet Annihilation–Based Photon Upconversion Systems to Solar Technologies. J. Photonics Energy 2018, 8, 1. 10.1117/1.JPE.8.022005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Yang T.; Feng W.; Li F. Blue-Emissive Upconversion Nanoparticles for Low–Power–Excited Bioimaging in Vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 5390–5397. 10.1021/ja3003638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G.; Wang H.; Shi H.; Wang H.; Zhu M.; Jing A.; Li J.; Li G. Recent Progress in the Development of Upconversion Nanomaterials in Bioimaging and Disease Treatment. J. Nanobiotechnology 2020, 18, 154. 10.1186/s12951-020-00713-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. C.; Merrifield R. E.; Avakian P.; Flippen R. B. Effects of Magnetic Fields on the Mutual Annihilation of Triplet Excitons in Molecular Crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1967, 19, 285–287. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.19.285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merrifield R. E. Theory of Magnetic Field Effects on the Mutual Annihilation of Triplet Excitons. J. Chem. Phys. 1968, 48, 4318–4319. 10.1063/1.1669777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams M.; Kozlowska M.; Baroni N.; Oldenburg M.; Ma R.; Busko D.; Turshatov A.; Emandi G.; Senge M. O.; Haldar R.; W oll C.; Nienhaus G. U.; Richards B. S.; Howard I. A. Highly Efficient One–Dimensional Triplet Exciton Transport in a Palladium–Porphyrin–Based Surface–Anchored Metal–Organic Framework. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 15688–15697. 10.1021/acsami.9b03079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuer H.; Petruccione F.. The Theory of Open Quantum Systems; Oxford University Press: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lidar D. A.Lecture Notes on the Theory of Open Quantum Systems. arXiv:1902.00967 2019, 1–131. [Google Scholar]

- Campaioli F.; Cole J. H.; Hapuarachchi H.. A Tutorial on Quantum Master Equations: Tips and tricks for quantum optics, quantum computing and beyond. arXiv:2303.16449 2023, 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell J. Theory of Nuclear Magnetic Relaxation. Polymer 1985, 26, 193–196. 10.1016/0032-3861(85)90029-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkelbach T. C.; Hybertsen M. S.; Reichman D. R. Microscopic Theory of Singlet Exciton Fission. I. General Formulation. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 114102. 10.1063/1.4794425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R. H.; Hutchison C. A. Electron Nuclear Double Resonance of Photoexcited Anthracene Molecules in Their Lowest Triplet State in Phenazine Single Crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 54, 2962–2968. 10.1063/1.1675279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forecast R.; Campaioli F.; Schmidt T. W.; Cole J. H. Photochemical Upconversion in Solution: The Role of Oxygen and Magnetic Field Response. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 1794–1800. 10.1021/acs.jpca.2c08883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss L. R.; Bayliss S. L.; Kraffert F.; Thorley K. J.; Anthony J. E.; Bittl R.; Friend R. H.; Rao A.; Greenham N. C.; Behrends J. Strongly Exchange–Coupled Triplet Pairs in an Organic Semiconductor. Nat. Phys. 2017, 13, 176–181. 10.1038/nphys3908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tayebjee M. J. Y.; Sanders S. N.; Kumarasamy E.; Campos L. M.; Sfeir M. Y.; McCamey D. R. Quintet Multiexciton Dynamics in Singlet Fission. Nat. Phys. 2017, 13, 182–188. 10.1038/nphys3909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald T. S. C.; Tayebjee M. J. Y.; Collins M. I.; Kumarasamy E.; Sanders S. N.; Sfeir M. Y.; Campos L. M.; McCamey D. R. Anisotropic Multiexciton Quintet and Triplet Dynamics in Singlet Fission via Pulsed Electron Spin Resonance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 15275–15283. 10.1021/jacs.3c02672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiale Feng P. H.; de Clercq D.; Nielsen M.; Brett M.; Prasad S.; Farahani A.; Li H.; Sanders S.; Beves J.; Ekins-Daukes N.; Cole J.; Thordarson P.; Tayebjee M.; Schmidt T.. Observation of an Emissive Intermediate in a Liquid Singlet Fission and Triplet Fusion System at Room Temperature. 2023, working paper. [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama K.; Wakikawa Y.; Miura T.; Fujimori J.-i.; Ito F.; Ikoma T. Solvent Viscosity Effect on Triplet–Triplet Pair in Triplet Fusion. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 15901–15908. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b11208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forecast R.; Gholizadeh E. M.; Prasad S. K. K.; Blacket S.; Tapping P. C.; McCamey D. R.; Tayebjee M. J. Y.; Huang D. M.; Cole J. H.; Schmidt T. W. Power Dependence of the Magnetic Field Effect on Triplet Fusion: A Quantitative Model. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 4742–4747. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c00919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware W. R. Oxygen Quenching of Fluorescence in Solution: An Experimental Study of the Diffusion Process. J. Phys. Chem. 1962, 66, 455–458. 10.1021/j100809a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bharmoria P.; Bildirir H.; Moth-Poulsen K. Triplet–Triplet Annihilation Based Near Infrared to Visible Molecular Photon Upconversion. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 6529–6554. 10.1039/D0CS00257G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. B.; Michl J. Recent Advances in Singlet Fission. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2013, 64, 361–386. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040412-110130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldacchino A. J.; Collins M. I.; Nielsen M. P.; Schmidt T. W.; McCamey D. R.; Tayebjee M. J. Y. Singlet Fission Photovoltaics: Progress and Promising Pathways. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2022, 3, 021304. 10.1063/5.0080250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson R. J.; MacDonald T. S. C.; Cole J. H.; Schmidt T. W.; Smith T. A.; McCamey D. R.. Nature Reviews Chemistry 2023, in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.