Abstract

Blacklegged ticks (Ixodes scapularis Say, Acari: Ixodidae) were collected from 432 locations across New York State (NYS) during the summer and autumn of 2015–2020 to determine the prevalence and geographic distribution of Borrelia miyamotoi (Spirochaetales: Spirochaetaceae) and coinfections with other tick-borne pathogens. A total of 48,386 I. scapularis were individually analyzed using a multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction assay to simultaneously detect the presence of Bo. miyamotoi, Borrelia burgdorferi (Spirochaetales: Spirochaetaceae), Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae), and Babesia microti (Piroplasmida: Babesiidae). Overall prevalence of Bo. miyamotoi in host-seeking nymphs and adults varied geographically and temporally at the regional level. The rate of polymicrobial infection in Bo. miyamotoi-infected ticks varied by developmental stage, with certain co-infections occurring more frequently than expected by chance. Entomological risk of exposure to Bo. miyamotoi-infected nymphal and adult ticks (entomological risk index [ERI]) across NYS regions in relation to human cases of Bo. miyamotoi disease identified during the study period demonstrated spatial and temporal variation. The relationship between select environmental factors and Bo. miyamotoi ERI was explored using generalized linear mixed effects models, resulting in different factors significantly impacting ERI for nymphs and adult ticks. These results can inform estimates of Bo. miyamotoi disease risk and further our understanding of Bo. miyamotoi ecological dynamics in regions where this pathogen is known to occur.

Keywords: tick, entomological risk index, Borrelia miyamotoi disease, polymicrobial infection, co-infection

Borrelia miyamotoi is a spirochete belonging to the relapsing fever borreliae group. It was first isolated from Ixodes persulcatus (Schulze, Acari: Ixodidae) ticks and small mammals in Japan (Fukunaga et al. 1995), and later detected in Connecticut, United States from Ixodes scapularis (Say, Acari: Ixodidae) (Scoles et al. 2001). This pathogen now has a broad distribution throughout the northern hemisphere (Platonov et al. 2011, Gellar et al. 2012, Jahfari et al. 2014, Sato et al. 2014, Krause et al. 2015) and is considered the etiological agent of a relapsing fever illness, Borrelia miyamotoi disease (BMD), in humans (Platonov et al. 2011, Chowdri et al. 2013, Krause et al. 2015, Wroblewski et al. 2017). Common symptoms of BMD include fatigue, headache, fever >40 °C, chills, arthralgia, nausea, and myalgia (Dworkin et al. 2002, Chowdri et al. 2013, Krause et al. 2013, Wagemakers et al. 2015). Compatible clinical presentation accompanied by travel history to a region where Lyme disease is endemic help to identify suspect BMD cases warranting further evaluation. Laboratory tests, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of whole blood and antibody determination, are used to confirm infection with Bo. miyamotoi (Ullmann et al., 2005, Chowdri et al., 2013, Molloy et al., 2015, Wroblewski et al. 2017). Most patients experience uncomplicated recovery following treatment with doxycycline (Platonov et al. 2011, Chowdri et al. 2013), though potential complications in immunocompromised individuals may include meningoencephalitis and central nervous system involvement (Gugliotta et al. 2013, Molloy et al. 2015). Polymicrobial infection of Bo. miyamotoi with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto (Spirochaetales: Spirochaetaceae) the causative agent of Lyme disease in the northeastern United States, Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) the causative agent of anaplasmosis or Babesia microti (Piroplasmida: Babesiidae) the causative agent of babesiosis, has been reported in vector ticks (DiBernardo et al. 2014, Takano et al. 2014, Johnson et al. 2018, Lehane et al. 2021) and the occurrence of tick-borne coinfections of may complicate or delay patient diagnosis and treatment (Magnarelli et al. 1987, Krause et al. 1996, Belongia 2002).

In the northeastern United States and Canada, Bo. miyamotoi is primarily transmitted by I. scapularis, and infection is maintained in the vector both transstadially and transovarially (Scoles et al. 2001, Rollend et al. 2013). Ixodes pacificus (Cooley and Kohls, Acari: Ixodidae) and I. ricinus (L., Acari: Ixodidae) serve as vectors of Bo. miyamotoi in the northwestern United States and Europe, respectively. In previous studies, prevalence of Bo. miyamotoi in host-seeking ticks from the northeastern United States and New England ranged from 0 to 10% (Scoles et al. 2001, Tokarz et al. 2010, Krause et al. 2015, Keesing et al. 2021, Lehane et al. 2021). Bo. miyamotoi has been detected in North America in the white-footed mouse Peromyscus leucopus (Rafinesque, Rodentia: Cricetidae) wild turkeys Meleagris gallopavo (L., Galliformes: Phasianidae) and in several species of passerine birds, particularly northern cardinals Cardinalis cardinalis (L., Passeriformes: Cardinalidae) (Scoles et al. 2001, Hamer et al. 2012). Additionally, the existence of a cryptic enzootic maintenance cycle involving the rabbit tick, Ixodes dentatus (Marx, Acari: Ixodidae) and reservoir competent bird species has been suggested (Hamer et al. 2012).

Both nationally and in New York State (NYS), Bo. miyamotoi human infections are not currently classified as a reportable disease under public health law. As such, physicians and clinical laboratories are not legally obligated to report diagnosed BMD cases or positive clinical laboratory test results detecting Bo. miyamotoi to the NYS Department of Health (NYSDOH) or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and there is limited knowledge of the full epidemiologic and geographic distribution of Bo. miyamotoi infection in NYS residents and nationally. However, more than 224 human cases of BMD have been identified in residents of the northeastern United States (Gugliotta et al. 2013, Krause et al. 2013, 2014, Molloy et al. 2015, Fiorito et al. 2017, Marcos et al. 2020), including NYS (Wroblewski et al. 2017). A statewide pilot study conducted in NYS identified 8 patients out of 1,162 clinical samples (0.7%) who tested positive for Bo. miyamotoi after testing negative for suspected anaplasmosis infection (Wroblewski et al. 2017). The same study also documented the prevalence of Bo. miyamotoi and other tick-borne pathogens in I. scapularis adults obtained from hunter-killed white-tailed deer, Odocoileus virginianus (Zimmerman, Artiodactyla: Cervidae) harvested from 13 counties in the Hudson Valley and Capital District regions of NYS in 2013 and 2014; finding an overall prevalence of 1.5, 20, and 27% for Bo. miyamotoi, Bo. burgdorferi, and A. phagocytophilum, respectively. An earlier study on the polymicrobial infection of host-seeking adult ticks in 4 southeastern NYS counties found a prevalence of 2, 20, 20, and 64% for Bo. miyamotoi, A. phagocytophilum, Ba. microti and Bo. burgdorferi, respectively (Tokarz et al. 2010) and a substantial overall coinfection rate of 30%, with Bo. miyamotoi coinfection occurring in only 0.6% of the ticks tested. More recently, Bo. miyamotoi was detected in 1.2% of host-seeking ticks collected from >100 locations across Dutchess County, NY, with a maximum site-level prevalence of 9.1% and no temporal trend in infection prevalence noted over 8 yrs (Keesing et al. 2021). However, it is important to note that these previous NYS studies were limited in their scope, both geographically and with respect to sample sizes.

The NYSDOH has conducted statewide active surveillance of pathogens in host-seeking ticks since 2008, including Bo. burgdorferi, A. phagocytophilum, and Ba. microti. In 2015, Bo. miyamotoi was added to the NYSDOH routine tick surveillance testing panel to identify presence and prevalence in tick populations on public lands across NYS. In this study, we examined spatial and temporal trends in Bo. miyamotoi and co-infection data from 48,386 individual host-seeking I. scapularis systematically collected and tested over a 6-yr period from across NYS. In addition, we calculated entomological risk indices to determine the timing and location of potential high-risk encounters with Bo. miyamotoi-infected I. scapularis nymphs and adults. We used generalized linear mixed effects models to examine the potential impact of certain environmental factors on Bo. miyamotoi entomological risk index (ERI) and evaluated polymicrobial infection rates in Bo. miyamotoi-infected host-seeking ticks to further explore pathogen ecology. Our study is the first to evaluate the spatiotemporal dynamics of Bo. miyamotoi-infected host-seeking I. scapularis nymph and adult tick populations in relation to human BMD cases across the entirety of NYS; our results can inform estimates of BMD risk to humans and further our understanding of Bo. miyamotoi ecological dynamics in regions where this pathogen is emerging or established.

Materials and Methods

BMD Human Case Data

Clinical samples submitted to the NYSDOH Wadsworth Center Bacteriology Laboratory from 2014 to 2020 for anaplasmosis testing that subsequently screened negative for A. phagocytophilum and positive for the presence of Bo. miyamotoi by previously described methods (Wroblewski et al. 2017) were classified as BMD cases and included in this study. Epidemiological factors associated with BMD cases, including the NYS county and United States Postal Service (USPS) ZIP code of patient residence, the month and year of symptom onset, age, sex, race, and ethnicity, were recorded with Bo. miyamotoi test results in the NYSDOH Electronic Clinical Laboratory Reporting System.

Tick Collections

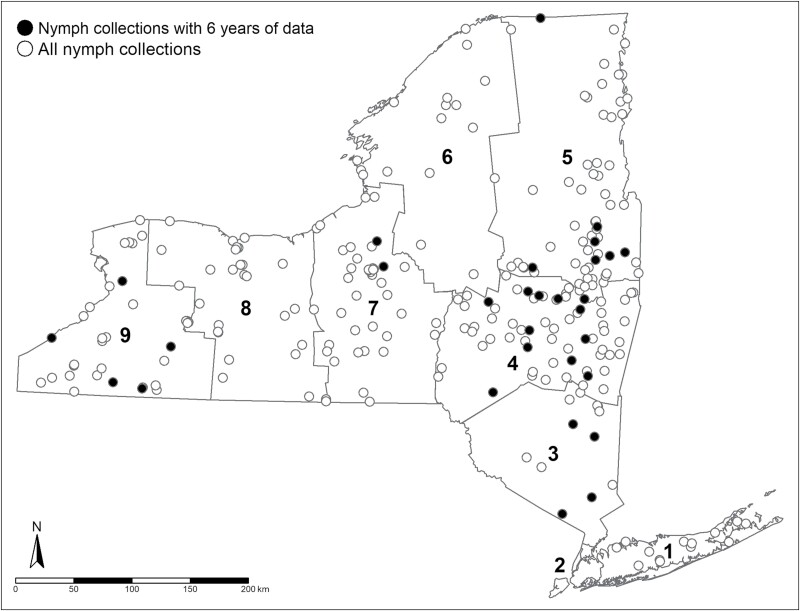

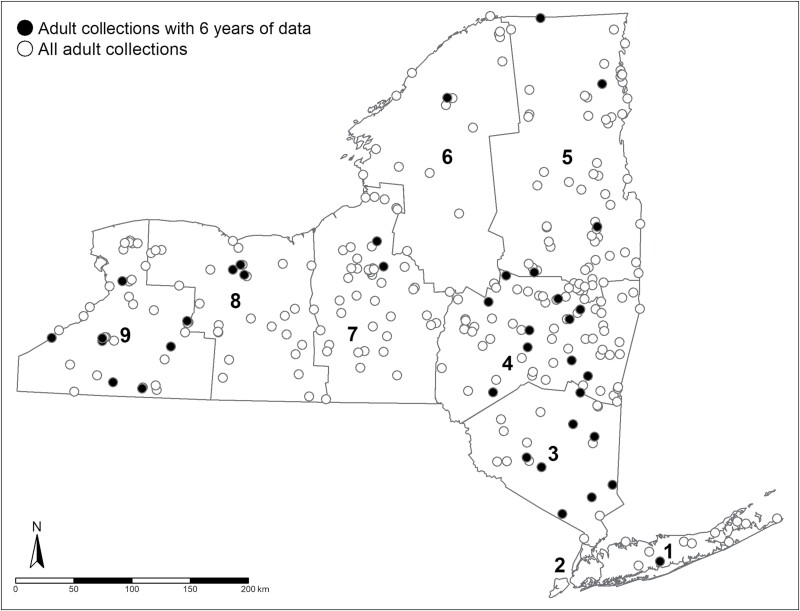

Host-seeking nymphal and adult I. scapularis were collected from publicly accessible forested lands across NYS (Figs. 1 and 2) during May-August and October–December of 2015–2020, respectively, using a 1 m2 piece of white fabric during standardized dragging and flagging surveys as previously described (Prusinski et al. 2014). Ambient air temperature, relative humidity, and general weather and site conditions were recorded at the time of sampling. A total of 559 collection sites were selected across NYS, excluding New York City, based on established criteria for habitat suitability for I. scapularis, associated vertebrate hosts, and for human exposure potential. Ticks were preserved in the field in 99.5% ethanol, returned to the laboratory, and maintained at 4○C until identified to species under a dissecting microscope (Model SMZ1000, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) using dichotomous keys (Cooley and Kohls 1944, Keirans and Clifford 1978, Keirans and Litwak 1989, Durden and Keirans 1996, Coley 2015, Egizi et al. 2019). Tick specimens were accessioned, placed into individually blind-labeled sterile 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes containing 99.5% ethanol, and stored at −20○C until nucleic acid extraction.

Fig. 1.

Spatial distribution of nymphal Ixodes scapularis collections conducted by the New York State Department of Health in New York during 2015–2020.

Fig. 2.

Spatial distribution of adult Ixodes scapularis collections conducted by the New York State Department of Health in New York during 2015–2020.

Nucleic Acid Extraction

Briefly, individual ticks were double rinsed with nuclease-free distilled water and homogenized as previously described (Prusinski et al. 2014). Tick DNA was extracted on the QIAcube HT automated platform using the QIAamp 96 kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and a manufacturer generated protocol with final elution volumes of 100 µl and 200 µl for nymphs and adult ticks, respectively, and stored at −20○C until polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. Each 96-well extraction plate consisted of 92 samples and 4 randomly distributed negative extraction control wells, with 200 µl Buffer AE (Qiagen, Valencia, CA.) substituted for sample. Extraction of tick DNA was conducted under BSL2 conditions in a class 2 biological safety cabinet with laminar airflow (SterilGARDIII Advance, Baker Co., Sanford, ME) designated exclusively for DNA extraction, and sterile aerosol-barrier tips were used during all procedures to prevent cross contamination.

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Individual I. scapularis nymphs and adults were tested for Bo. burgdorferi, Ba. microti, A. phagocytophilum, and Bo. miyamotoi by real-time multiplex PCR assay as detailed elsewhere (Piedmonte et al. 2018). All fluorogenic probes and primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) and Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Reactions were prepared in a 1:1 mixture of 5× PerfeCta MultiPlex qPCR ToughMix, Low ROX and 2× PerfeCta MultiPlex qPCR SuperMix, Low ROX (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD) such that each reaction contained 5 μl of ToughMix/SuperMix with primer and probe concentrations as described (Piedmonte et al. 2018), to which 9 μl of template was added, yielding a 25 μl final reaction volume. A negative control with nuclease-free water substituted for template DNA, and a positive control consisting of 7.8 μl purified pathogen-free I. scapularis DNA in nuclease-free water with 0.3 μl each of the following: DNA extracted from whole blood of a Ba. microti-infected C3H/HeN mouse (10% parasitemia), low-passage Bo. burgdorferi B31 lysate (Stony Brook, NY), previously isolated A. phagocytophilum genomic DNA (CDC, Atlanta, GA), and B. hermsii DNA purified from culture (DSMZ) were included with each run. Amplification was carried out on an ABI 7500 Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using white 96-well semi-skirted plates with optically clear adhesive seal (Thermo Scientific, USA). Thermocycling conditions consisted of 50°C for 2 min and initial denaturation and activation of AccuStart Taq DNA polymerase at 95○C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of amplification with denaturation at 95○C for 15 sec and annealing at 63○C for 1 min. All PCR was performed in an isolated location separate from DNA extraction, in a class 2 biological safety cabinet with laminar airflow designated exclusively for PCR, using sterile aerosol-barrier tips, designated micropipettors, and strict sterile technique to prevent cross contamination of samples. All real-time mulitplex PCR data were interpreted with a cut-off of cycle 40 and analyzed using the Applied Biosystems 7500 SDS Software Version 1.4 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as previously described (Piedmonte et al. 2018). Samples testing positive for A. phagocytophilum by multiplex PCR were further tested using a custom TaqMan SNP genotyping PCR assay to differentiate between the Ap-ha and Ap-V1 variants of A. phagocytophilum as described elsewhere (Krakowetz et al. 2014, Prusinski et al. 2023).

Data Analysis

Data were imported into R (RStudio Team, 2022) (version 4.1.2). Collection locations were assigned to 1 of 8 NYS Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) regions (Figs. 1 and 2). An ERI was calculated for nymphs and adults separately for each collection event as the product of I. scapularis nymphs or adults per 1,000 m2 sampled and the proportion of ticks infected with Bo. miyamotoi. In instances where a location was visited on multiple occasions within a given sampling season, the infection prevalence and tick density measures were averaged using the R package “dplyr” (Wickham et al. 2021), and the resulting averages were used to generate a single ERI value for each site and year. There was no control for the effect of phenology due to the limited ticks collected per location and lack of repeated sampling events per collection season at most locations. The site-level data for I. scapularis nymphs and adults, separately, were used to generate risk maps for each developmental stage using the tmap package in R (Tennekes 2018) where individual data points represented a collection site, the color indicated detection of Bo. miyamotoi, and size of each data point represented the degree of risk (ERI).

A Tweedie distribution generalized linear mixed effects model (GLMM) (Foster and Bravington 2013) was generated using site-level data from locations with consistent collections across all 6 study years for nymphs (177 sampling events, 30 sites) and adults (221 sampling events, 37 sites) separately in R studio using the “glmmTMB” package (Brooks et al. 2017), to examine the significance of the following predictors on ERI: year, region, elevation (30 km resolution), average maximum temperature and average cm of rainfall from weather stations during the collection season for each life stage (DeGaetano et al. 2014), and average relative humidity at the time of field collection. A Tweedie distribution was chosen for this model to accommodate the zero-inflated semi-continuous ERI outcome variable. These ecological variables were scaled using the base R “scale” function, where each value was normalized by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation, to account for large variation in values among variables (Becker et al. 1988). To determine model fit, backwards selection was conducted with the variables of interest. The model with the lowest Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) value (Burnham and Anderson 2004) was chosen. Year and region were treated as categorical variables and their significance was determined using ANOVA within the R package “car” (Fox and Weisberg 2019). The packages “lmer4” and “simr” were used to conduct a post-hoc power analysis following a simplified version of the Tweedie GLMM models in R studio (Bates et al. 2015, Green and MacLeod 2016).

To analyze spatial and temporal trends at the region and year level, the R package “dplyr” was used to aggregate I. scapularis density, Bo. miyamotoi prevalence, and ERI. These aggregated values were plotted in a bar chart to visualize overall variation in risk among regions and years. Post hoc analysis of the model was conducted to determine which regions and years were different from one another using pairwise comparisons in the R package “emmeans” (Lenth 2022); significant values (α ≤ 0.05). The R package “emmeans” was also used to visualize estimated marginal means among the significant interactions. In addition to ERI, polymicrobial tick infection rates were determined for Bo. miyamotoi-infected I. scapularis. Chi-square tests were performed with the R package “stats” (R Core Team 2021) and were used to determine if Bo. miyamotoi coinfection with any other pathogens occurred more frequently than expected by chance.

Results

BMD Human Cases

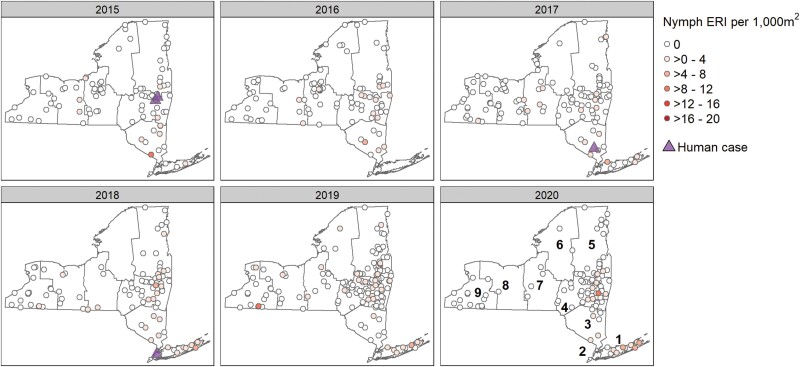

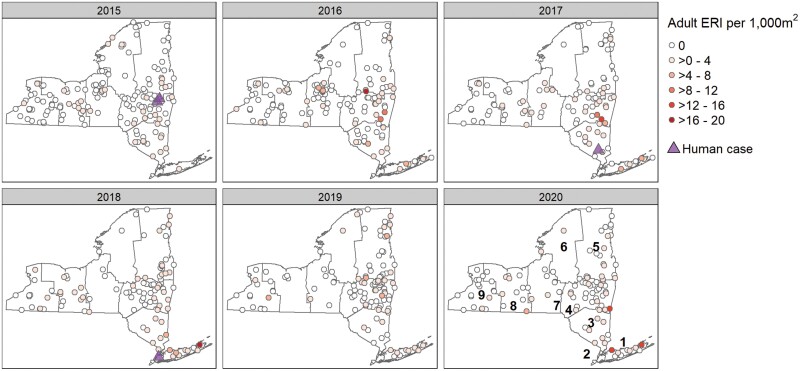

Between the years of 2014 and 2020, there were 5 human cases of BMD identified by the NYSDOH Wadsworth Center Bacteriology Laboratory of 942 clinical specimens tested for Bo. miyamotoi (0.5%). Demographic data for BMD cases are presented in Table 1. Race and ethnicity fields were incomplete for all BMD cases and were subsequently excluded from our analyses. Information on travel history was also incomplete for all 5 identified cases. BMD cases were residents of 4 different NYS geographic regions. Spatially, in Region 1, 1 of 147 (0.6% positive) was identified in 2014; in Region 4, 2 of 266 (0.8%) patients tested positive in 2015; in Region 3, 1 of 172 (0.6%) patients tested positive in 2017; and in Region 2, 1 of 88 (1.1%) tested positive in 2018. There were no detected cases reported in 2016 (n = 118 patients tested), 2019 (n = 87), and 2020 (n = 64) (Figs. 3 and 4).

Table 1.

Positive cases of laboratory-confirmed Borrelia miyamotoi infection in New York State from 2014 to 2020.

| Characteristic | Bo. miyamotoi-positive cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | |

| 10–19 | 1 (20%) |

| 40–49 | 2 (40%) |

| 50–59 | 1 (20%) |

| 60–69 | 1 (20%) |

| Age (yr) | |

| Mean (SD) | 43.4 (19.23) |

| Median (max, min) | 46 (13, 64) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 2 (40%) |

| Female | 2 (40%) |

| Missing | 1 (20%) |

| Month of symptom onset | |

| May | 1 (20%) |

| Jun | 1 (20%) |

| Aug | 2 (40%) |

| Sep | 1 (20%) |

Fig. 3.

Risk of encountering Borrelia miyamotoi-infected Ixodes scapularis nymphs during 2015–2020 across New York State regions and years in relation to BMD human cases.

Fig. 4.

Risk of encountering Borrelia miyamotoi-infected Ixodes scapularis adults during 2015–2020 across New York State regions and years in relation to BMD human cases.

Tick Collections

A total of 151,065 ticks were collected during 2,463 sampling attempts at 559 locations across all 57 NYS counties (excluding New York City) between 15 April 2015 and 27 November 2020. Of these, 111,437 I. scapularis (23,399 larvae [L], 27,553 nymphs [N], 60,485 adults [A]) were obtained from 432 locations in 57 counties and comprised 73.8% of the total ticks collected. Other tick species encountered (26%) included: Amblyomma americanum (L., Acari: Ixodidae) (10,682 N, 3,525 A), Dermacentor albipictus (Packard, Acari: Ixodidae) (125 L), Dermacentor variabilis (Say, Acari: Ixodidae) (27 L, 2 N, 1,453 A), Haemaphysalis leporispalustris (Packard, Acari: Ixodidae) (261 L, 32 N), Haemaphysalis longicornis (Neumann, Acari: Ixodidae) (23,290 L, 67 N, 95 A), Ixodes angustus (Neumann, Acari: Ixodidae) (2 L), Ixodes dentatus (Marx, Acari: Ixodidae) (2 L, 36 N), Ixodes cookei (Packard, Acari: Ixodidae) (5 L, 11 N, 4 A), Ixodes marxi (Banks, Acari: Ixodidae) (1 L, 5 N, 2 A), and Ixodes muris (Bishopp, Acari: Ixodidae) (1 A). Average tick densities (ticks per 1,000 m2 ± SE) for host-seeking I. scapularis nymphs and adults, respectively, were 22.5 ± 1.3 and 47.3 ± 2.2, with annual variation and regional differences in average density (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percent Borrelia miyamotoi positive collections, mean tick density and mean Bo. miyamotoi Entomological Risk Index for Ixodes scapularis nymphs and adults across years and New York State regions from 2015 to 2020.

| % Positive collections (positive collections/total collections) | Mean tick density per 1,000 m2 (±SE) | Mean prevalence (±SE) | Mean ERI per 1,000 m2 (±SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nymph | 17.60% (116/659) | 22.50 (1.32) | 0.007 (0.001) | 0.27 (0.04) |

| Year | ||||

| 2015 | 11.11% (10/90) | 20.67 (3.51) | 0.004 (0.002) | 0.16 (0.11) |

| 2016 | 15.79% (15/95) | 16.32 (2.98) | 0.006 (0.003) | 0.14 (0.06) |

| 2017 | 14.05% (17/121) | 24.19 (2.89) | 0.004 (0.001) | 0.20 (0.07) |

| 2018 | 27.96% (26/93) | 22.66 (3.92) | 0.010 (0.002) | 0.44 (0.11) |

| 2019 | 19.21% (29/151) | 31.39 (3.37) | 0.006 (0.001) | 0.29 (0.09) |

| 2020 | 17.43% (19/109) | 15.08 (1.95) | 0.010 (0.002) | 0.36 (0.13) |

| Region | ||||

| Region 1 | 69.23% (27/39) | 45.78 (6.64) | 0.031 (0.005) | 1.67 (0.34) |

| Region 3 | 45.45% (20/44) | 65.79 (8.91) | 0.017 (0.005) | 0.84 (0.26) |

| Region 4 | 16.41% (32/195) | 23.38 (2.40) | 0.007 (0.002) | 0.21 (0.05) |

| Region 5 | 10.49% (15/143) | 10.68 (1.44) | 0.003 (0.001) | 0.06 (0.02) |

| Region 6 | 5.26% (1/19) | 11.77 (2.65) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.04 (0.04) |

| Region 7 | 15.71% (11/70) | 12.48 (1.23) | 0.004 (0.001) | 0.06 (0.02) |

| Region 8 | 9.52% (6/63) | 22.60 (4.58) | 0.004 (0.002) | 0.10 (0.05) |

| Region 9 | 4.65% (4/86) | 17.94 (2.71) | 0.002 (0.001) | 0.15 (0.13) |

| Adult | 30.91% (230/744) | 47.27 (2.21) | 0.012 (0.001) | 0.65 (0.07) |

| Year | ||||

| 2015 | 23.72% (37/156) | 29.51 (3.10) | 0.012 (0.003) | 0.32 (0.06) |

| 2016 | 29.41% (40/136) | 56.85 (7.31) | 0.008 (0.001) | 0.77 (0.18) |

| 2017 | 31.53% (35/111) | 53.66 (5.22) | 0.015 (0.005) | 0.81 (0.20) |

| 2018 | 43.27% (45/104) | 36.21 (3.22) | 0.016 (0.003) | 0.78 (0.190 |

| 2019 | 29.51% (36/122) | 56.23 (5.10) | 0.009 (0.001) | 0.52 (0.11) |

| 2020 | 32.17% (37/115) | 54.38 (6.62) | 0.013 (0.002) | 0.82 (0.21) |

| Region | ||||

| Region 1 | 66.67% (30/45) | 73.37 (10.55) | 0.028 (0.004) | 2.33 (0.58) |

| Region 3 | 52.31% (34/65) | 52.79 (4.11) | 0.017 (0.003) | 0.87 (0.13) |

| Region 4 | 32.62% (61/187) | 55.90 (6.04) | 0.012 (0.002) | 0.79 (0.15) |

| Region 5 | 25.52% (37/145) | 37.92 (4.21) | 0.009 (0.002) | 0.49 (0.14) |

| Region 6 | 23.33% (7/30) | 37.07 (5.09) | 0.008 (0.003) | 0.35 (0.14) |

| Region 7 | 29.49% (23/78) | 37.82 (6.34) | 0.013 (0.006) | 0.43 (0.13) |

| Region 8 | 27.17% (25/92) | 49.65 (5.47) | 0.009 (0.002) | 0.34 (0.08) |

| Region 9 | 12.75% (13/102) | 38.27 (4.32) | 0.006 (0.003) | 0.26 (0.09) |

Pathogen Prevalence

A total of 48,386 I. scapularis (18,235 N, 30,151 A) were tested for Bo. burgdorferi, Ba. microti, A. phagocytophilum, and Bo. miyamotoi by real-time multiplex PCR assay, of which 581 were positive for the presence of Bo. miyamotoi. Overall prevalence of these pathogens for nymphs and adults, respectively, was 25% (n = 4,502) and 54% (n = 16,117) for Bo. burgdorferi, 5.3% (n = 964) and 8.4% (n = 2,522) for A. phagocytophilum, 4.6% (n = 834) and 5.1% (n = 1,535) for Ba. microti, and 1.1% (n = 194) and 1.3% (n = 387) for Bo. miyamotoi. Borrelia miyamotoi was detected in 34 of 57 NYS counties (60%) where I. scapularis nymphs were obtained, and from 47 of 57 NYS counties (83%) across all geographic regions where host-seeking adult I. scapularis populations were found (Figs. 3 and 4). Regional mean prevalence of Bo. miyamotoi in nymphs and adults, respectively, ranged from 0.1% and 0.6% to 3.1% and 2.8% (Table 2). Annual site-level Bo. miyamotoi prevalence ranged from 1.6 to 20% for nymphs from 67 of 288 locations (23.3%) and from 0.8 to 33% in adult ticks from 131 of 379 locations (34.6%). At locations with sufficient sample size to accurately assess pathogen prevalence (n ≥ 50 ticks tested), Bo. miyamotoi site level infection rates in host-seeking I. scapularis ranged from 1.6 to 16.0% for nymphs and 0.8–12.0% for adults. The overall mean prevalence of Bo. miyamotoi in nymphs was lowest in 2015 and 2017 (0.4%) and highest in 2018 and 2020 (1.0%) and ranged from 0.8% in 2016 to 1.6% in 2018 for adult I. scapularis (Table 2).

Polymicrobial Infections

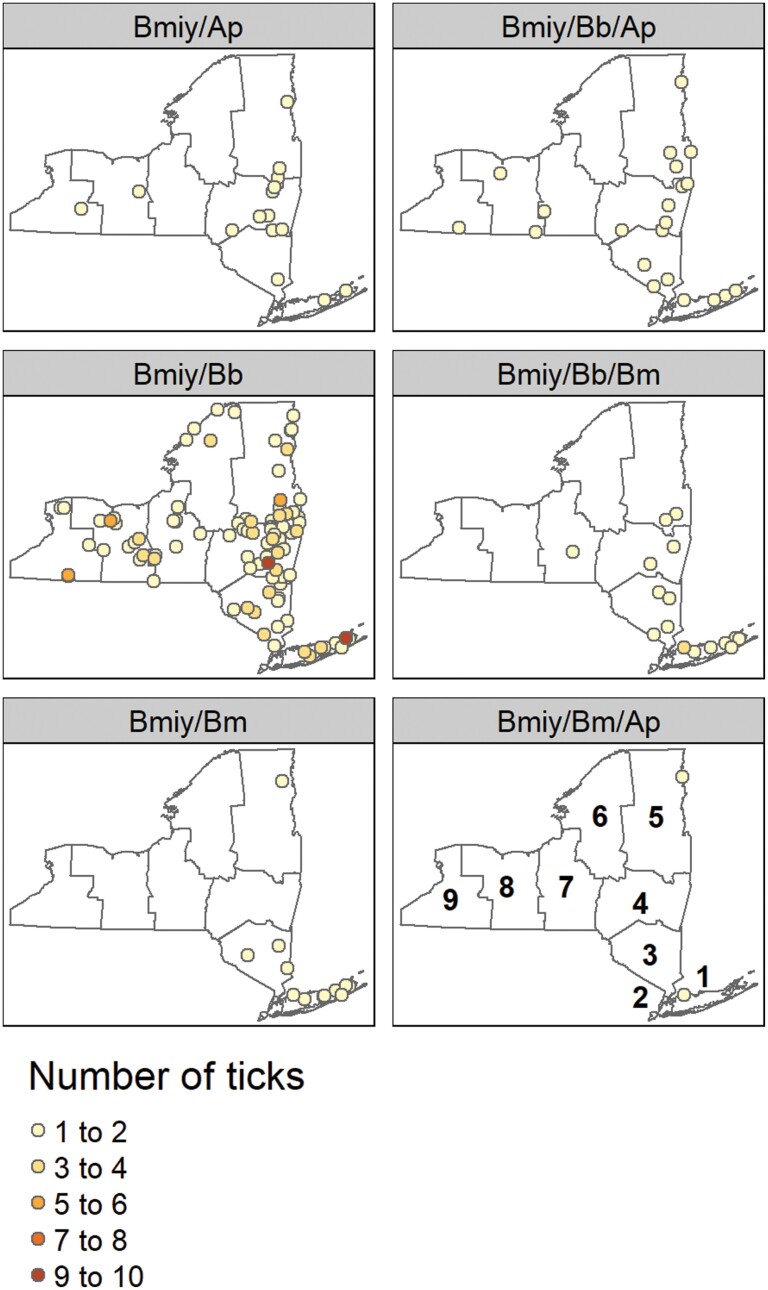

Of the 581 ticks (194 N, 387 A) testing positive for Bo. miyamotoi; 299 (124 N, 175 A) were single infections (52%), 228 (55 N, 173 A) were dual infections (39%), and 50 (15 N, 35 A) were triple infections (8.6%). Four adult ticks (0.7%) were infected with all 4 pathogens (Table 3). The overall rate of polymicrobial infection was 36% for Bo. miyamotoi-infected nymphs and 55% for adults. Adult ticks accounted for 75% of Bo. miyamotoi co-infections. The most frequently detected pathogens found together in the same tick were Bo. miyamotoi and Bo. burgdorferi (n = 202, 35%). Of pairwise combinations, Bo. miyamotoi and Ba. microti co-occurred together (n = 47, 8.1%) more often than expected by chance (χ2 = 10.27, df = 1, P-value = 0.001). Ticks simultaneously infected with 2 pathogens were found in all NYS geographic regions; as were ticks co-infected with 3 pathogens, with the exception of Region 6 (Fig. 5). Three of the four quadruple infected adult ticks were collected in Region 1 and 1 was from Region 3, both located in the southeastern portion of NYS (Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Co-infections in Borrelia miyamotoi-infected Ixodes scapularis collected in New York State from 2015 to 2020.

| Pathogens | No. ticks (n = 581) (%) |

Life stage | A. phagocytophilum variant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bmiy/Bb/Bm/Ap | 4 (0.7%) | F = 3 M = 1 N = 0 |

ha = 3 v1 = 1 ha/v1 = 0 undetermined = 0 |

| Bmiy/Bb/Bm | 25 (4.3%) | F = 8 M = 5 N = 12 |

– |

| Bmiy/Bb/Ap | 23 (4.0%) | F = 8 M = 13 N = 2 |

ha = 18 v1 = 1 ha/v1 = 0 undetermined = 4 |

| Bmiy/Bm/Ap | 2 (0.3%) | F = 1 M = 0 N = 1 |

ha = 2 v1 = 0 ha/v1 = 0 undetermined = 0 |

| Bmiy/Bb | 196 (33.7%) | F = 87 M = 65 N = 44 |

– |

| Bmiy/Bm | 16 (2.8%) | F = 6 M = 1 N = 9 |

– |

| Bmiy/Ap | 16 (2.8%) | F = 9 M = 5 N = 2 |

ha = 11 v1 = 5 ha/v1 = 0 undetermined=0 |

| Bmiy only | 299 (51.5%) | F = 87 M = 88 N = 124 |

– |

Bmiy = Borrelia miyamotoi, Bb = Borrelia burgdorferi, Bm = Babesia microti, Ap = Anaplasma phagocytophilum, ha = human active, v1 = variant 1.

Fig. 5.

Spatial distribution of co-infected Ixodes scapularis collected in New York State from 2015–2020. *Bmiy = Borrelia miyamotoi, Bb = Borrelia burgdorferi, Bm = Babesia microti, Ap = Ananplasma phagocytophilum.

Borrelia miyamotoi Entomological Risk Index

Overall, the average Bo. miyamotoi ERI for adults and nymphs, respectively was 0.65 (SE ± 0.07) and 0.27 (SE ± 0.04). Mean nymphal and adult Bo. miyamotoi ERI values across study years and NYS regions are shown in Table 2. Borrelia miyamotoi ERI for nymphal ticks was lowest in Region 6 (0.04) and highest in Region 1 (1.67). Nymphal Bo. miyamotoi ERI was lowest in 2016 (0.14) and highest in 2018 (0.44). Borrelia miyamotoi ERI for adult ticks was lowest in Region 9 (0.26) and highest in Region 1 (2.33). Risk of encountering Bo. miyamotoi-infected adult I. scapularis was lowest in 2015 (0.32) and highest in 2020 (0.82). The geographic distribution of Bo. miyamotoi ERI values at sampling sites was similar throughout all study years for both nymphal and adult tick collections. Specifically, the highest ERI values were located in regions 1, 3, and 4 which were also the regions containing identified cases of BMD (Figs. 3 and 4.) Notably, the risk of encountering Bo. miyamotoi-infected adults was higher than the risk of encountering infected nymphs across all regions and years (t = 5.05, df = 1198, P-value ≤ 0.001).

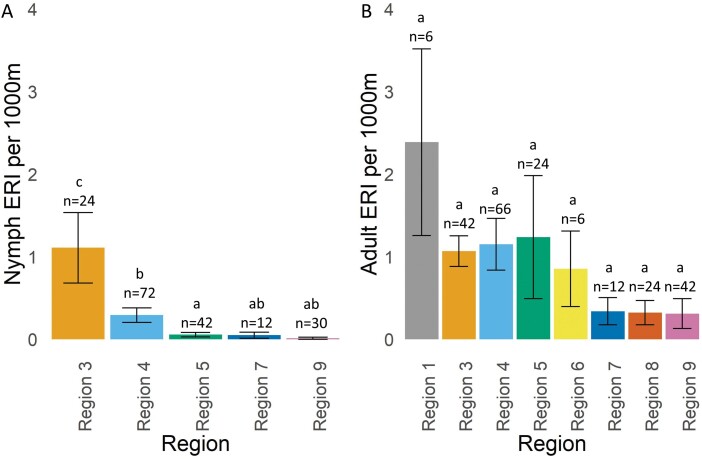

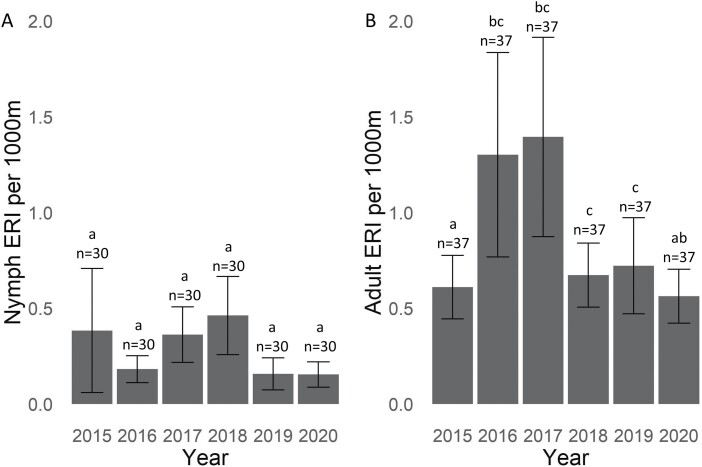

Overall, the average Bo. miyamotoi ERI for nymphal ticks across sites that were sampled consistently over all 6 study years was 0.28 (SE ± 0.07), with the highest risk in Region 3 (Fig. 6A). All other regions were significantly lower than Region 3 based on pairwise comparisons. In addition, Region 5 was significantly lower than Region 4. The overall average Bo. miyamotoi ERI for adult ticks across sites with consistent sampling data across all 6 yr of our study was 0.88 (SE ± 0.13), with the highest risk in Region 1 (Fig. 6B). There were no significant differences among regions in adult tick Bo. miyamotoi ERI. The risk of encountering Bo. miyamotoi-infected nymphs was highest in 2018 across sites that were sampled during all 6 study years with 0.46 (SE ± 0.20). However, based on pairwise comparisons, there was no significant difference among years (Fig. 7A). The risk of encountering Bo. miyamotoi-infected adults was highest in 2017 across sites with 6 years of sampling data with 1.39 (SE ± 0.52) infected adults encountered every 1,000 m2. However, pairwise comparisons show that risk in 2017 was significantly higher than 2015 and no other years (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 6.

Risk of exposure to Borrelia miyamotoi-infected Ixodes scapularis by New York State region, 2015–2020. Bars with different letters are significantly different from each other. Letters only signify statistical differences within that tick developmental stage and cannot be compared across developmental stages.

Fig. 7.

Risk of exposure to Borrelia. miyamotoi-infected Ixodes scapularis by year of collection, 2015–2020 in New York State. Bars with different letters are significantly different from each other. The letters only signify statistical differences within that developmental stage and cannot be compared between both stages.

Borrelia miyamotoi ERI Environmental Models

Elevation influenced risk of encountering Bo. miyamotoi-infected nymphs as determined by ERI (Table 4). Elevation was negatively associated with ERI (β = −1.37, P < 0.001) in the analyses of nymphal I. scapularis. ANOVA of the final nymphal model revealed NYS region had a significant impact on ERI (χ2 = 39.38, df = 4, P-value ≤ 0.001) but year did not. Due to the lack of consistent nymphal sampling and environmental data collection at the time of tick sampling at sites on Long Island (Region 1) during the study period, it was excluded from our analyses of nymphal I. scapularis.

Table 4.

Model parameters and significant predictors for human exposure to Borrelia miyamotoi-infected Ixodes scapularis nymphs in NYS. (AIC: 245.4)

| Mean Entomological Risk Index per 1,000 m2 ~ year + region + elevation + mean relative humidity + (1 | location) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number of sampling events: 177 Number of sites: 30 | ||

| Predictors | Coefficient estimates | P-values |

| Intercept (Region 3 2015) | −0.4291 | 0.3800 |

| Elevation | −1.3671 | <0.001a |

| Mean relative humidity | 0.2960 | 0.094a |

Mean Bo. miyamotoi ERI per 1,000 m2 = average number of infected ticks encountered every 1,000 m2, year = year collection occurred, region = region collection occurred, mean relative humidity = average on site relative humidity values for location that year, mean maximum temperature = average maximum temperature from May to August, elevation = elevation of collection site within 30 km, (1 | location) = random effects for location.

aStatistically significant.

Mean rainfall, relative humidity, maximum temperature, and the interaction between relative humidity and maximum temperature influenced adult tick Bo. miyamotoi ERI when comparing collection data for sites with consistent adult tick sampling across all 6 study years (Table 5). Mean relative humidity was positively associated with ERI (β = 0.25, P-value = 0.048); mean maximum temperature was positively associated with ERI (β = 1.11, P-value < 0.001); mean rainfall was negatively associated with ERI (β = −0.42, P-value = 0.018); and the interaction between mean relative humidity was negatively associated with ERI (β = −0.31, P-value = 0.018). ANOVA analysis of the final adult model revealed year was significantly associated with adult tick Bo. miyamotoi ERI (χ2 = 20.25, df = 5, P-value = 0.001) but region was not.

Table 5.

Model parameters and significant predictors for human exposure to Borrelia miyamotoi-infected Ixodes scapularis adults in New York State. (AIC: 574.2)

| Mean Entomological Risk Index per 1,000 m2 ~ year + region + mean relative humidity + mean maximum temperature + mean rainfall cm + (1 | location) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number of sampling events: 221 Number of sites: 37 | ||

| Predictors | Coefficient estimates | P-values |

| Intercept (Region 1 2015) | −2.6115 | 0.0281a |

| Mean max. temperature (Oct–Dec) | 1.1131 | 0.0003a |

| Mean rainfall (Oct–Dec) | −0.4179 | 0.0185a |

| Mean relative humidity (RH) | 0.2544 | 0.0475a |

| Mean RH × mean max. temperature (Oct–Dec) | −0.3064 | 0.0179a |

Mean Bo. miyamotoi ERI per 1,000 m2 = average number of infected ticks encountered every 1,000 m2, year = year collection occurred, region = region collection occurred, mean relative humidity = average on site relative humidity values for location that year, mean maximum temperature = average maximum temperature from October to December, mean rainfall cm = average rainfall in cm from October to December, (1 | location) = random effects for location.

aStatistically significant.

Discussion

Global Bo. miyamotoi infection rates reported in ticks range from 0.02% to 6.4% (Cutler et al. 2019) and the prevalence of Bo. miyamotoi in host-seeking I. scapularis from NYS was similar at the site level to those reported previously (Scoles et al. 2001, Tokarz et al. 2010, Krause et al. 2015, Keesing et al. 2021). We detected Bo. miyamotoi in 3.1% of nymphs and 2.8% of I. scapularis adults from Suffolk County (Region 1), consistent with the 2.6% and 3.4%, respectively, reported previously (Tokarz et al. 2017). A study recently conducted in Dutchess County, NY (Region 3), had an overall Bo. miyamotoi prevalence of 1.2% out of 3,647 nymphal I. scapularis (Keesing et al. 2021). Yuan et al. (2020) also reported Bo. miyamotoi infection rates in adult ticks from Region 3 (Westchester County) to be 2.2% (1/45) and 14% (1/7) in 2017 and 2018, respectively. In Region 3, the average Bo. miyamotoi prevalence for both nymphal and adult ticks was 1.7%. Targeted sampling of ticks from the southeastern portion of this NYS region, encompassing Westchester County, should be considered to better define areas with elevated risk.

Across all study sites, average Bo. miyamotoi ERI was 2.4 times higher in adult ticks in comparison to nymphs (Table 2), and geographic regions with higher Bo. miyamotoi ERI in ticks overlapped with locations of human BMD cases reported during the study period in NYS. However, the paucity of cases detected by NYSDOH Wadsworth clinical BMD testing and the lack of patient travel histories reduced our confidence in the significance of spatial overlap with areas of elevated predicted Bo. miyamotoi risk. Bo. miyamotoi ERI in adult ticks was highest in 2016 and 2017, and significantly lower in 2015. In contrast, nymphal ERI was highest in 2015. However, not all sites were sampled for both adults and nymphs every year and further examination of locations that were sampled annually for both developmental stages is warranted.

Our GLMM model results indicated that nymphal Bo. miyamotoi ERI was statistically higher in the Hudson Valley in southeastern NYS (Region 3) compared to the other regions. Nymphal Bo. miyamotoi ERI in Region 4, an area known as the “Capital District Region”, was also significantly higher than risk in Region 5, which includes the Adirondack Mountains. The relatively higher levels of risk in Regions 3 and 4 are not surprising, as these areas of NYS also have increased prevalence of other I. scapularis-associated pathogens, including A. phagocytophilum (Russell et al. 2021, Prusinski et al. 2023), Bo. burgdorferi (Prusinski et al. 2014, Lin et al. 2019) and Ba. microti (Kogut et al. 2005, Linden et al. 2018, O’Connor et al. 2021) with increased incidence of associated disease in humans. While Long Island (Region 1) was excluded from our nymphal analyses due to lack of consistent sampling at set locations during the entirety of the study period, almost 70% of the nymphal I. scapularis collection attempts in Suffolk County (Region 1) yielded Bo. miyamotoi-infected ticks (Table 3), with a county-level prevalence of 3.6%. Risk of encountering Bo. miyamotoi-infected adults was also highest in Region 1. However, these differences were not statistically significant in the adult tick model, likely due to the limited number of sites that were consistently sampled across all years in Region 1. The lack of consistent sampling reduced our ability to identify true differences between Region 1 and other regions, particularly those with more consistent sampling during the study period. Future studies should consider consistent annual sampling of I. scapularis nymphs and adults at additional sites in Region 1 to enable higher resolution analyses of Bo. miyamotoi dynamics in this area of elevated risk.

Pathogen co-infection results for I. scapularis adults and nymphs infected with Bo. miyamotoi were similar. The most frequently detected pathogens found together in the same tick were Bo. miyamotoi and Bo. burgdorferi (Table 5). It is likely that these pathogens infect the same reservoir species and ticks ingest both pathogens while feeding on a single host. The white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) is a major reservoir of Bo. burgdorferi and has been found to be co-infected with Bo. miyamotoi in the northeastern United States (Barbour et al. 2009). Additionally, Bo. burgdorferi is the most prevalent and geographically dispersed tick-borne disease agent in NYS tick populations (Prusinski et al., 2014, Yuan et al. 2020). Babesia microti infection in ticks was significantly associated with Bo. miyamotoi infection. This result may also be attributed to P. leucopus serving as a common reservoir for both pathogens (Dunn et al. 2014) and is also likely related to the spatial distribution of Ba. microti in NYS, where the highest prevalence in host-seeking ticks occurred in the southeastern potion of NYS (O’Connor et al. 2021), including the Hudson Valley (Region 3) and Long Island (Region 1), which also had the highest prevalence of Bo. miyamotoi in our study. Additional studies are necessary to better understand the transmission dynamics and microbial interactions in ticks co-infected with multiple pathogens, including Bo. miyamotoi.

The polymicrobial infection rates we detected have important clinical implications. Of the 581 ticks that were infected with Bo. miyamotoi, 35% were also infected with Bo. burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease in the northeastern United States. Since BMD is not currently a reportable condition in NYS under public health law, screening for Bo. miyamotoi in clinical samples is infrequent and significant misdiagnosis and underreporting of BMD likely occurs in NYS. Patients presenting with flu-like symptoms and history of tick bite in Lyme disease endemic areas are commonly tested for Bo. burgdorferi and subsequently treated with antibiotics, such as doxycycline, and may not be screened for other lesser-known emerging pathogens like Bo. miyamotoi. As both BMD and Lyme disease are successfully treated with doxycycline, the lack of specific clinical testing for Bo. miyamotoi infection likely leads to missed diagnoses of BMD in the event of Lyme disease co-infection, complicating our understanding of BMD epidemiology, burden, and risk. Additionally, babesiosis patients receiving appropriate treatment, who screen negative for concurrent Lyme disease or anaplasmosis infection but continue to exhibit symptoms consistent with these diseases should be screened for Bo. miyamotoi infection, as they would potentially benefit from proper diagnosis and prompt initiation of doxycycline treatment for BMD.

In our study, risk of exposure to Bo. miyamotoi-infected I. scapularis nymphs was influenced by elevation. Habitat suitability for I. scapularis has been shown to decrease as elevation increases (Hahn et al. 2016). In addition, fewer reproductive and reservoir hosts may be available at higher elevations (Mccain and Grytnes 2010). For example, Rand et al. (2003) reported that the number of I. scapularis collected from white-tailed deer decreased as elevation increased, potentially due to a lack of smaller mammal hosts and increased probability of adverse microclimatic conditions for the immature tick life stages. However, in contrast to nymphs, elevation was not shown to be a significant predictor of adult tick Bo. miyamotoi ERI, possibly indicating that elevation may have a larger impact on the survival of immature ticks in the larval stage than as engorged nymphs or adults.

Borrelia miyamotoi adult tick ERI was significantly influenced by mean seasonal temperature, mean seasonal rainfall, and relative humidity. Increases in temperature during the autumn questing period would lead to increased Bo. miyamotoi risk, as temperature has been positively correlated to questing activity in I. scapularis adults (Duffy and Campbell 1994). Rainfall led to a significant decrease in risk of encountering Bo. miyamotoi infected adults, as increased periods of rain may suppress questing activity and successful host acquisition over a season. Increases in relative humidity at the site level led to an increased risk of encountering adults infected with Bo. miyamotoi. These results agree with previous results indicating that tick questing and abundance are positively related to relative humidity (Berger et al. 2014). Statistically significant interaction between relative humidity at the site level and mean seasonal temperature indicates that the risk of encountering a Bo. miyamotoi-infected adult I. scapularis varies across these 2 variables.

Our study is subject to several limitations that decreased our ability to robustly model BMD risk. Sample sizes of Bo. miyamotoi-infected host-seeking ticks were small in certain regions and years, due to limitations in available NYSDOH resources dedicated to surveillance sampling, making it difficult to make statistically significant comparisons across space and time. The collection data were analyzed with year as a categorical variable due to limited samples for each year, which limited our ability to determine temporal difference within years. It would be beneficial to analyze the data on a more granular scale with collection month included as a predictor, to potentially assess if these factors impact BMD risk seasonally within years and within the context of vector phenology. In addition to overall sample size, specific multi-year sampling at consistent locations was limited, further reducing statistical power to model risk. For instance, Region 1 had the highest reported Bo. miyamotoi risk in nymphal collections, but these values were excluded from the model due to lack of consistent nymphal sampling and/or recording of key environmental data at the time of sampling at some locations in the region. Results of our post hoc power analysis indicated that our sample size was sufficient to evaluate the effect of year, region, and maximum temperature on adult and nymphal ERI; however, our models lacked sufficient power to estimate effect sizes for other included covariates. Future annual sampling of both nymphal and adult ticks at set locations and complete recording of required site-level environmental data has now been implemented and will facilitate more precise risk estimates going forward. In addition, the data provided by the nearest weather stations were aggregated across the sampling season to provide an average temperature and rainfall value for each site across the target sampling season for each tick developmental stage. The generalized weather values may not accurately represent macro- and microhabitat conditions for the tick populations sampled. For future studies, measuring temperature, rainfall, and humidity at the microclimate level with data loggers or point measures at the time of sampling would provide more accurate information concerning the impact of these variables on tick questing and resulting human risk (Teel et al. 1982, Boehnke et al. 2017). Other measures such as saturation deficit could potentially represent more accurate predictors of risk and should be considered in future studies. Further investigations should be conducted to better understand the dynamic relationships among various climate and ecological variables on nymphal Bo. miyamotoi risk.

As a transovarially transmitted pathogen (Scoles et al. 2001, Breuner et al. 2018), sampling and testing of I. scapularis larvae for Bo. miyamotoi would contribute to estimates of BMD risk and may provide an early warning of emerging exposure risk to infected nymphs and adults. While a large number of I. scapularis larvae were collected during the course of our study, they were processed and tested for Powassan/Deer Tick virus (Amarillovirales: Flaviviridae) as part of ongoing enhanced NYSDOH arboviral surveillance efforts. Future prospective and retrospective screening of larval ticks for Bo. miyamotoi may better elucidate the role of larvae in pathogen transmission.

Our study is the first to evaluate the spatiotemporal dynamics of Bo. miyamotoi-infected host-seeking I. scapularis nymph and adult tick populations in relation to human BMD cases across the entirety of NYS. While Bo. miyamotoi prevalence in host-seeking ticks was low compared with other tick-borne pathogens and diagnosed cases of BMD are rare and likely vastly underreported due to lack of reporting mandates, risk of Bo. miyamotoi exposure was found to be present across all geographic regions of NYS. Our results highlighted areas of NYS where residents are potentially at higher risk of encountering Bo. miyamotoi-infected I. scapularis, and documented study years with the highest risk as determined by ERI. We identified factors that may influence Bo. miyamotoi risk and determined that abiotic factors influence tick risk differently by tick developmental stage. Bo. miyamotoi co-infections were common in our study, especially with Bo. burgdorferi and Ba. microti, and may have significant clinical implications. The association between Bo. miyamotoi and Ba. microti highlights the likelihood of overlapping reservoir hosts, spatial geography and resulting increased risk of exposure to both pathogens.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, the New York State Department of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, and various county, town, and village park managers for granting us the use of lands to conduct this research. We extend thanks to the following individuals for their assistance in collection, identification, and/or molecular testing of ticks: T. Zembsch, L. Rose, L. Meehan, E. Banker, R. Reichel, S. Beebe, J. Sherwood, J. Howard, D. Rice, M. Katz, N. Piedmonte, S. Keyel, O. Timm, our dedicated undergraduate and graduate student assistants, M. Fierke and associates with the State University of New York (SUNY) College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Colgate University students and faculty, C. Hartl and others from SUNY Brockport, Niagara County Department of Health (DOH), S. Campbell, M. Santoriello, C. Romano with Suffolk County DOH, and I. Rochlin and M. Cucura with Suffolk County Vector Control. We would like to thank Erika Mudrak from the Cornell Statistical Consulting Unit for aiding with data analysis and modeling. We would also like to extend thanks to the New York State Integrated Pest Management Program for providing climatic data from the Network for Environment and Weather Applications. Additionally, we thank E. Lutterloh and L. Eisen for helpful comments and suggestions that improved the manuscript. This work was supported by the New York State Department of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (award U01CK000509), the CDC Emerging Infections Program TickNET (Cooperative Agreement NU50CK000486), and the National Institutes of Health (grants AI097137 and AI142572). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Contributor Information

Nicole Foley, Department of Entomology, Cornell University, 3138/2130 Comstock Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA.

Collin O’Connor, New York State Department of Health, Bureau of Communicable Disease Control, Western New York Regional Office, 584 Delaware Avenue, Buffalo, NY 14202, USA; Department of Geography, University at Buffalo, Suite 105, Buffalo, NY, 14261, USA.

Richard C Falco, New York State Department of Health, Fordham University, Vector Ecology Laboratory, Louis Calder Center, 53 Whippoorwill Road, Armonk, NY 10504, USA.

Vanessa Vinci, New York State Department of Health, Fordham University, Vector Ecology Laboratory, Louis Calder Center, 53 Whippoorwill Road, Armonk, NY 10504, USA.

JoAnne Oliver, New York State Department of Health, Bureau of Communicable Disease Control, Central New York Regional Office, 217 South Salina Street, 3rd Floor, Syracuse, NY 13202, USA.

Jamie Haight, New York State Department of Health, Bureau of Communicable Disease Control, Chautauqua County DPF Offices, 454 North Work Street, Room B-05, Falconer, NY 14733, USA.

Lee Ann Sporn, Paul Smith’s College, State Routes 30 and 86, Paul Smiths, NY 12970, USA.

Laura Harrington, Department of Entomology, Cornell University, 3138/2130 Comstock Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA.

Emily Mader, Department of Entomology, Cornell University, 3138/2130 Comstock Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA.

Danielle Wroblewski, Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health, Bacteriology Laboratory, David Axelrod Institute, 120 New Scotland Avenue, Albany, NY 12208, USA.

P Bryon Backenson, New York State Department of Health, Bureau of Communicable Disease Control, Communicable Disease Investigations and Vector Surveillance Unit, Empire State Plaza, Albany, NY 12237, USA.

Melissa A Prusinski, New York State Department of Health, Bureau of Communicable Disease Control, Vector Ecology Laboratory, Wadsworth Center Biggs Laboratory C-456, Empire State Plaza, Albany, NY 12237, USA.

References

- Barbour AG, Bunikis J, Travinsky B, Hoen A, Diuk-Wasser M, Fish D, Tsao JI. Niche partitioning of Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia miyamotoi in the same tick vector and mammalian reservoir species. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009:81:1120–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015:67(1):1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker RA, Chambers JM, Wilks AR. The New S language. Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Belongia EA. Epidemiology and impact of coinfections acquired from Ixodes ticks. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2002:2(4):265–273. 10.1089/153036602321653851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger KA, Ginsberg HS, Gonzalez L, Mather TN. Relative humidity and activity patterns of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 2014:51(4):769–776. 10.1603/me13186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehnke D, Gebhardt R, Petney T, Norra S. On the complexity of measuring forests microclimate and interpreting its relevance in habitat ecology: the example of Ixodes ricinus ticks. Parasites Vectors. 2017:10(1):549. 10.1186/s13071-017-2498-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuner NE, Hojgaard A, Replogle AJ, Boegler KA, Eisen L. Transmission of the relapsing fever spirochete, Borrelia miyamotoi, by single transovarially-infected larval Ixodes scapularis ticks. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018:9(6):1464–1467. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks M, Kristensen K, Koen J, Magnussson A, Berg C, Neilsen A, Skaug H, Maechler M, Bolker B. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J. 2017:9:378–400. https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2017/RJ-2017-066/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Burnham K, Anderson D. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. New York: Springer New York; 2004. 10.1007/B97636 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdri HR, Gugliotta JL, Berardi VP, Goethert HK, Molloy PJ, Sterling SL, Telford SR. Borrelia miyamotoi infection presenting as human granulocytic anaplasmosis. Ann Intern Med. 2013:159(1):21–27. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley K. Identification guide to larval stages of ticks of medical importance in the USA [B.S. thesis]. [Statesboro (GA)]: Georgia Southern University Honors College; 2015. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/110. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley RA, Kohls GM. The genus Amblyomma (Ixodidae) in the United States. J Parasitol. 1944:30:7770–7111. 10.2307/3272571 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SJ, Vayssier-Taussat M, Estrada-Peña A, Potkonjak A, Mihalca AD, Zeller H. A new Borrelia on the block: Borrelia miyamotoi – a human health risk?. Euro Surveill. 2019:24:1–14. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.18.1800170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGaetano AT, Noon W, Eggleston KL. Efficient access to climate products in support of climate services using the applied climate information system (ACIS) web services. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2014:96:173–180. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-13-00032.1 [Google Scholar]

- DiBernardo A, Cote T, Ogden NH, Lindsay LR. The prevalence of Borrelia miyamotoi infection, and co-infections with other Borrelia spp. in Ixodes scapularis ticks collected in Canada. Parasites Vectors. 2014:183:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy DC, Campbell SR. Ambient air temperature as a predictor of activity of adult Ixodes scapularis (Acari, Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 1994:31(1):178–180. 10.1093/jmedent/31.1.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JM, Krause PJ, Davis S, Vannier EG, Fitzpatrick MC, Rollend L, Belperron AA, States SL, Stacey A, Bockenstedt LK, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi promotes the establishment of Babesia microti in the northeastern United States. PLoS One. 2014:9(12):e115494. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durden LA, Keirans JE. Nymphs of the genus Ixodes (Acari: Ixodidae) of the United States: taxonomy, identification key, distribution, hosts, and medical/veterinary importance. Lanham (MD): Entomological Society of America; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin MS, Shoemaker PC, Fritz CL, Dowell ME, Anderson DE. The epidemiology of tick-borne relapsing fever in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002:66(6):753–758. 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egizi AM, Robbins RG, Beati L, Nava S, Evans CR, Occi JL, Fonseca DM. A pictorial key to differentiate the recently detected exotic Haemaphysalis longicornis Neumann, 1901 (Acari, Ixodidae) from native congeners in North America. ZooKeys. 2019:818:117–128. 10.3897/zookeys.818.30448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorito TM, Reece R, Flanigan TP, Silverblatt FJ. Borrelia miyamotoi polymerase chain reaction positivity on a tick-borne disease panel in an endemic region of Rhode Island: a case series. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2017:25(5):250–254. 10.1097/ipc.0000000000000509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foster SD, Bravington MV. A poisson-gamma model for analysis of ecological non-negative continuous data. Environ Ecol Stat. 2013:20:533–552. 10.1007/s10651-012-0233-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J, Weisberg S. An R companion to applied regression. 3rd ed.. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publishing; 2019. https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion/. [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga M, Takahashi Y, Tsuruta Y, Matsushita O, Ralph D, McClelland M, Nakao M. Genetic and phenotypic analysis of Borrelia miyamotoi sp. nov., isolated from the Ixodid tick Ixodes persulcatus, the vector for the Lyme disease. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995:45(4):804–810. 10.1099/00207713-45-4-804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellar J, Nazarova L, Katargina O, Jarvekulg L, Fomenko N, Golovljova I. Detection and genetic characterization of relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia miyamotoi in Estonian ticks. PLoS One. 2012:7:e15915–e15917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green P, MacLeod CJ. simr: an R package for power analysis of generalised linear mixed models by simulation. Methods Ecol Evol. 2016:7(4):493–498. 10.1111/2041-210x.12504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gugliotta JL, Goethert HK, Berardi VP, Telford SR. Meningoencephalitis from Borrelia miyamotoi in an immunocompromised patient. N Engl J Med. 2013:368(3):240–245. 10.1056/NEJMoa1209039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn MB, Jarnevich CS, Monaghan AJ, Eisen RJ. Modeling the geographic distribution of Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) in the contiguous United States. J Med Entomol. 2016:53(5):1176–1191. 10.1093/jme/tjw076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer SA, Hickling GJ, Keith R, Sidge JL, Walker ED, Tsao JI. Associations of passerine birds, rabbits, and ticks with Borrelia miyamotoi and Borrelia andersonii in Michigan, U.S.A. Parasites Vectors. 2012:5:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahfari S, Herremans T, Platonov AE, Kuiper H, Karan LS, Vasilieva O, Koopmans M, Hovius JWR, Sprong H. High seroprevelance of Borrelia miyamotoi antibodies in forestry workers and individuals suspected of human granulocytic anaplasmosis in the Netherlands. New Microbe New Infect. 2014:2:144–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TL, Graham CB, Maes SE, Hojgaard A, Fleshman A, Boegler KA, Delory MJ, Slater KS, Karpathy SE, Bjork JK, et al. Prevalence and distribution of seven human pathogens in host-seeking Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) nymphs in Minnesota, USA. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018:9(6):1499–1507. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keesing F, McHenry DJ, Hersh MH, Ostfeld RS. Spatial and temporal patterns of the emerging tick-borne pathogen Borrelia miyamotoi in blacklegged ticks (Ixodes scapularis) in New York. Parasites Vectors. 2021:14:51. 10.1186/s13071-020-04569-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keirans JE, Clifford CM. The genus Ixodes in the United States: A scanning electron microscope study and key to the adults. J Med Entomol. 1978:2:1–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keirans JE, Litwak TR. Pictorial key to the adults of hard ticks, family Ixodidae (Ixodida: Ixodoidea) east of the Mississippi River. J Med Entomol. 1989:26(5):435–448. 10.1093/jmedent/26.5.435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogut SJ, Thill CD, Prusinski MA, Lee J, Backenson PB, Coleman JL, Anand M, White DJ. Babesia microti, upstate New York. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005:11(3):476–478. 10.3201/eid1103.040599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowetz CN, Dibernardo A, Lindsay LR, Chilton NB. Two Anaplasma phagocytophilum strains in Ixodes scapularis ticks, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014:20(12):2064–2067. 10.3201/eid2012.140172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause PJ, Fish D, Narasimhan S, Barbour AG. Borrelia miyamotoi infection in nature and in humans. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015:21(7):631–639. 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause PJ, Narasimhan S, Wormser GP, Barbour AG, Platonov AE, Brancato J, Lepore T, Dardick K, Mamula M, Rollend L, et al. ; Tick Borne Diseases Group. Borrelia miyamotoi sensu lato seroreactivity and seroprevalence in the northeastern United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014:20(7):1183–1190. 10.3201/eid2007.131587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause PJ, Narasimhan S, Wormser GP, Rollend L, Fikrig E, Lepore T, Barbour A, Fish D. Human Borrelia miyamotoi infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013:368(3): 291–293. 10.1056/NEJMc1215469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause PJ, Telford SR 3rd, Spielman A, Sikand V, Ryan R, Christianson D, Burke G, Brassard P, Pollack R, Peck J, et al. Concurrent Lyme disease and babesiosis. evidence for increased severity and duration of illness. JAMA. 1996:275(21):1657–1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehane A, Maes SE, Graham CB, Jones E, Delorey M, Eisen RJ. Prevalence of single and coinfections of human pathogens in Ixodes ticks from five geographical regions in the United States, 2013–2019. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2021:12(2):101637. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2020.101637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenth R. Emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R Package Version 1.7.2. 2022. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans. [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Shrestha S, Insaf T, Graber N, Backenson PB, Prusinski MA, White JL, Lukacik G, Hwang S. The effect of seasonal weather factors on incidence of Lyme disease and its vector during summer in New York State. J Total Environ. 2019:665:1182–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden J, Prusinski MA, Crowder L, Tonnetti L, Stramer S, Kessler D, White J, Shaz B, Olkowska D. Transfusion-transmitted and community-acquired babesiosis in New York, 2004–2015. Transfusion. 2018:58(3):660–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnarelli LA, Anderson JF, Johnson RC. Cross-reactivity in serologic tests for Lyme disease and other spirochetal infections. J Infect Dis. 1987:156(1):183–188. 10.1093/infdis/156.1.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos LA, Smith K, Reardon K, Weinbaum F, Spitzer ED. Presence of Borrelia miyamotoi infection in a highly endemic area of Lyme disease. Ann Clin Microbiol. 2020:19:1–4. 10.1186/s12941-020-00364-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCain CM, Grytnes JA. Elevational gradients in species richness. In: Encyclopedia of life sciences. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley and Sons; 2010. 10.1002/9780470015902.a0022548 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy PJ, Telford SR, Chowdri HR, Lepore TJ, Gugliotta JL, Weeks K, Hewins ME, Goethert H, Berardi VP. Borrelia miyamotoi disease in the northeastern United States. Ann Intern Med. 2015:163:91–98. 10.7326/M15-0333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor C, Prusinski MA, Jiang S, Russell A, White J, Falco R, Kokas J, Vinci V, Gall W, Tober K, et al. A comparative spatial and climate analysis of human granulocytic anaplasmosis and human babesiosis in New York State (2013-2018). J Med Entomol. 2021:38:2453–2466. 10.1093/jme/tjab107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piedmonte NP, Shaw SB, Prusinski MA, Fierke MK. Landscape features associated with blacklegged tick (Acari: Ixodidae) density and tick-borne pathogen prevalence at multiple spatial scales in central New York State. J Med Entomol. 2018:55(6):1496–1508. 10.1093/jme/tjy111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platonov AE, Karan LS, Kolyasnikova NM, Makhneva NA, Toporkova MG, Maleev VV, Fish D, Krause PJ. Humans infected with relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia miyamotoi, Russia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011:17(10):1816–1823. 10.3201/eid1710.101474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusinski MA, Kogut SJ, Hukey KT, Lee J, Kokas JE, Backenson PB. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi (Spirochaetales: Spirochaetaceae), Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae), and Babesia microti (Piroplasmida: Babesiidae) in Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) collected from recreational lands in the Hudson Valley region, New York State. J Med Entomol. 2014:51:226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusinski MA, O’Connor C, Russell A, Sommer J, White J, Rose L, Falco R, Kokas J, Vinci V, Gall W, et al. Associations of Anaplasma phagocytophilum bacteria variants in Ixodes scapularis ticks and humans, New York, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023:29:540–550. 10.3201/eid2903.220320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rand PW, Lubelczyk C, Lavigne GR, Elias S, Holman MS, Lacombe EH, Smith RP. Deer density and the abundance of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 2003:40(2):179–184. 10.1603/0022-2585-40.2.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollend L, Fish D, Childs JE. Transovarial transmission of Borrelia spirochetes by Ixodes scapularis: a summary of the literature and recent observations. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2013:4(1–2):46–51. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: integrated development environment for R. Boston (MA): RStudio, Inc.; 2022. http://www.rstudio.com/. [Google Scholar]

- Russell A, Prusinski M, Sommer J, O’Connor C, White J, Falco R, Kokas J, Vinci V, Gall W, Tober K, et al. Epidemiology and spatial emergence of anaplasmosis, New York, USA, 2010‒2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021:27(8):2154–2162. 10.3201/eid2708.210133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Takano A, Konnai S, Nakao A, Ito T, Koyama K, Kaneko M, Ohnishi M, Kawabata H. Human infections with Borrelia miyamotoi, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014:20:1391–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoles GA, Papero M, Beati L, Fish D. A relapsing fever group spirochete transmitted by Ixodes scapularis ticks. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2001:1(1):21–34. 10.1089/153036601750137624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano A, Toyomane K, Konnai S, Ohashi K, Nakao M, Ito T, Andoh M, Maeda K, Watarai M, Sato K, et al. Tick surveillance for relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia miyamotoi in Hokkaido, Japan. PLoS One. 2014:9(8):e104532. 10.1371/journal.pone.0104532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teel PD, Fleetwood SC, Huebner GL. An integrated sensing and data acquisition system designed for unattended continuous monitoring of microclimate relative humidity and its use to determine the influence of vapor pressure deficits on tick (Acari: Ixodoidea) activity. J Agric Meteorol. 1982:27:145–154. 10.1016/0002-1571(82)90002-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tennekes M. tmap: thematic maps in R. J Stat Softw. 2018:84:1–39. 10.18637/jss30450020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tokarz R, Jain K, Bennett A, Briese T, Lipkin WI. Assessment of polymicrobial infections in ticks in New York State. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010:10(3):217–221. 10.1089/vbz.2009.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokarz R, Tagliafierro T, Cucura DM, Rochlin I, Sameroff S, Lipkin WI. Detection of Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Babesia microti, Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia miyamotoi, and Powassan virus in ticks by a multiplex real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay. MSphere 2017:2(2):e00151-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullmann AJ, Gabitzsch ES, Schulze TL, Zeidner NS, Piesman J. Three multiplex assays for detection of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and Borrelia miyamotoi sensu lato in field-collected Ixodes nymphs in North America. J Med Entomol. 2005:42(6): 1057–1062. 10.1093/jmedent/42.6.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagemakers A, Staarink P, Sprong H, Hovius JWR. Borrelia miyamotoi: a widespread tick-borne relapsing fever spirochete. Trends Parasitol. 2015:31:260–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H, François R, Henry L, Müller K. dplyr: a grammar of data manipulation. R package version 1.0.7. 2021. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr. [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewski D, Gebhardt L, Prusinski MA, Meehan LJ, Halse TA, Musser KA. Detection of Borrelia miyamotoi and other tick-borne pathogens in human clinical specimens and Ixodes scapularis ticks in New York State, 2012–2015. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2017:8(3):407–411. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q, Llanos-Soto SG, Gangloff-Kaufmann JL, Lampman JM, Frye MJ, Benedict MC, Tallmadge RL, Mitchell PK, Anderson RR, Cronk BD, et al. Active surveillance of pathogens from ticks collected in New York State suburban parks and schoolyards. Zoonoses Public Health. 2020:67(6):684–696. 10.1111/zph.12749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]