Abstract

Background and Objectives

Elder mistreatment affects at least 1 in 10 older adults. Financial abuse, or exploitation, of older adults is among the most commonly reported forms of abuse. Few validated measures exist to measure this construct. We aim to present a new psychometrically validated measure of financial abuse of older adults.

Research Design and Methods

Classical test theory and item response theory (IRT) methodologies were used to examine a five-item measure of financial abuse of older adults, administered as part of the New York State Elder Mistreatment Survey.

Results

Factor analysis revealed a single factor best fits the data, which we labeled as financial abuse. Moreover, IRT analyses revealed that these items discriminated well between abused and nonabused persons and provided information at high levels of the latent trait θ, as is expected in cases of abuse.

Discussion and Implications

The Five-Item Victimization of Exploitation Scale has acceptable psychometric properties and has been used successfully in large-scale survey research. We recommend this measure as an indicator of financial abuse in elder abuse, or mistreatment prevalence research studies.

Keywords: IRT, Measurement validation, Mistreatment

Background and Objectives

Financial abuse of older adults occurs when a person in a position of trust obtains property or assets through deception or intimidation, or improperly uses the assets of an older adult (Hall et al., 2016). It represents one of the most common forms of elder mistreatment (EM). Research has shown a prevalence of approximately 4.5% (Pillemer et al., 2016) with a 10-year incidence of 8.5% (Burnes et al., 2021), affecting millions of older adults. However, research in this area is hampered by measurement issues, particularly overly burdensome and mostly unvalidated measures. A meta-analysis that examined financial abuse of older adults in prevalence studies found that the measurement of financial abuse is inconsistent and often involves the use of measures that lack established validity or reliability (Jackson, 2018). In response, this article seeks to demonstrate the psychometric properties of a five-item scale to measure self-reported financial abuse of older adults, the Five-Item Victimization of Exploitation (FIVE) scale.

There is a pressing need to measure financial abuse with validated tools; the FIVE scale seeks to address this issue. Typically, researchers have created or adapted scales to measure financial abuse but fail to provide information on the psychometric properties of the measure (Jackson, 2018). Such approaches include selecting a subset of items from previous scales, such as from the Hwalek–Sengstock Elder Abuse Screening Test (HS-EAST; Hwalek & Sengstock, 1986; Neale et al., 1991) or the Vulnerability to Abuse Screening Scale (VASS; Schofield & Mishra, 2003). Additionally, some scales were created based on prior research or policy, without the presentation of psychometric information (e.g., Amstadter et al., 2011; Biggs et al., 2009; among others). Other large-scale EM prevalence studies have measured financial abuse (Acierno et al., 2010; Beach et al., 2010; Laumann et al., 2008); however, none of these scales were presented with psychometric evidence. For example, Acierno et al. (2010, 2017) present a 10-item measure, without accompanying psychometric support, though the measure is conceptually similar to the FIVE scale. Beach et al. (2010) used a four-item measure, adapted from previous work, absent any psychometric properties. Additionally, Laumann et al. (2008) used a single-item measure for financial abuse, derived from other measures such as the HS-EAST and VASS. Overall, existing elder financial abuse measures have generally been administered without having demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties (Jackson, 2018).

An exception is the Older Adult Financial Exploitation Measure (OAFEM; Conrad et al., 2010), a 30-item measure developed and administered to an adult protective services sample, with substantiated claims of mistreatment, to assess the psychometric properties of the measure. Results indicated a unidimensional construct with high reliability and a hierarchy of severity of indicators of financial abuse, with major theft rated as very severe, whereas entitlement was a less severe form of abuse. A short form of this measure was created that reduced the number of items to 11, which still demonstrated good psychometric properties (Beach et al., 2017). The specificity of the short form was 0.96 and was strongly associated with the long-form measure of financial abuse. Sensitivity and specificity analyses revealed a cutoff score of 1; if any of the 11 items were endorsed, it was categorized as financial abuse. The authors recommended the use of the short form as a screen in applied settings, supplementing it with the long-form in positive cases to better understand the specifics of abuse (Beach et al., 2017).

However, both the long and short versions of the OAFEM have limitations. First, the 11-item version still is likely too long to be used as a screening tool, and both versions may be impractical to administer in survey research. Furthermore, the OAFEM was developed in an Adult Protective Services (APS) environment, whereas the measure described in this article is based on a general community sample. Measures used and validated among APS samples comprising victims and at-risk older adults may not generalize to older adults in the general population that predominantly consists of nonvictims.

With a proliferation of elder mistreatment survey research over the past decade (Pillemer et al., 2016), the development of validated financial abuse measurement tools is critical in advancing the rigor of elder abuse research in general, as well as the capacity to screen for the problem in real-world settings, such as health care or social service agencies, to identify older adults at risk. Given the wide range of measures that lack validation, a lack of consistency among measures, and the length of existing measures, we present the FIVE scale, a five-item self-report measure of financial abuse of older adults.

The current study examines the psychometric properties of the FIVE scale. This study used classical test theory (CTT) and item response theory (IRT) methodologies. First, we predict the measure to load on to a single factor, financial abuse, and for the measure to meet standard criteria of reliability (e.g., reliability >0.70; Nunnally, 1978). Additionally, to establish convergent validity, we examined the relationship between financial abuse and neglect and physical abuse. Jackson and Hafemeister (2011, 2013) differentiate financial abuse into two types: that which occurs without other forms of elder abuse, and that which co-occurs with physical abuse or neglect. These types of abuse are defined by different predictors and outcomes. Of note is the prevalence of co-occurring financial abuse and neglect (or physical abuse), sufficient to warrant its own categorization. In an examination of county reports of elder abuse, 38% reported financial abuse only, while 34% reported financial abuse with the presence of physical abuse or neglect (Choi & Mayer, 2000). Therefore, it is predicted that the measure of financial abuse presented here will correlate significantly with a measure of neglect and a measure of physical abuse, but not with emotional/psychological abuse, as it was not co-occurring with financial abuse to the same extent in prior work. Finally, using IRT methods, we predict that items will have high discriminations, be able to distinguish well between who is and is not abused, and high difficulties, suggesting that the items are only endorsed in serious circumstances, as is the case of abuse.

Research Design and Methods

Data

Sample

This study conducted a secondary analysis of data collected as part of the New York State Elder Mistreatment Prevalence Study (for a more detailed summary of the sample, see Burnes et al., 2015) wave 1. Random digit dialing was used to obtain a population-based representative (age, ethnicity, and sex) sample (n = 4,156). Participants were community-dwelling, cognitively intact (modified version of the abbreviated mental test), and older adults (>60).

Item creation

In the absence of an established measure of financial abuse among older adults in the general population, Lachs and Berman (2011) created a five-item self-report scale, the FIVE scale. To create the FIVE, the authors reviewed existing scales that included financial exploitation items and found many candidate instruments for their study (e.g., Manthorpe et al., 2007; Podnieks, 1993). However, for various reasons, these instruments lacked certain items commensurate with their goal. For example, some of the candidate instruments were created decades earlier and lacked newer forms of financial exploitation (e.g., misappropriation or theft of funds through electronic or online means, including ATM cards). Several rounds of expert consultation and a consensus technique were used to create the items for the FIVE scale in a multistage process involving

To ensure adequate coverage of financial abuse members of the study team recruited experts from diverse fields, including physicians, sociologists, direct social service providers, and scholars from the field of elder abuse. The experts provided information on what content could be adapted from prior work and what content needed to be added to adequately assess financial abuse. Questions were derived from commonly accepted definitions of financial abuse of older adults, reviews of the literature, and expert experience. A small number of participants known to be victims of financial exploitation derived from APS cases as well as a group of nonexploited “controls” were used to pilot test the data. The present study does not analyze these data. Results from the pilot test indicated that the FIVE scale had excellent sensitivity, identifying all cases in the known exploited group (Lachs & Berman, 2011). Each item also contained follow-up questions assessing the frequency and perceived severity of the financial abuse. Full question wording and answer choices are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Five-Item Victimization of Exploitation (FIVE) Scale Items

| Question | Question wording |

|---|---|

| Question stem | Since you turned 60 years old has someone you live with or spend a lot of time with ever done any of the following: |

| Question 1 | Stolen anything from you or used things that belonged to you but without your knowledge or permission? This could include money, bank ATM or credit cards, checks, personal property, or documents? |

| Question 2 | Forced, convinced, or misled you to give them something that belonged to you or to give them the legal rights to something that belonged to you? This could include money, a bank account, a credit card, a deed to a house, personal property, or documents such as a will (last will/testament) or power of attorney? |

| Question 3 | Pretended to be you to obtain goods or money? |

| Question 4 | Stopped contributing to household expenses such as rent or food where this arrangement had been previously agreed to, even if they were capable of still doing so? |

| Question 5 | Unwilling to contribute to household expenses to the extent that there was not enough money for food or other necessities? |

Note: Response options were “No,” “Yes,” “I don’t know,” or “Refused.”

Scoring

Each item was scored, with regards to financial abuse, “Yes” = 1 and “No” = 0. For analytic purposes, selections of “Do not know” or “Refused” are treated as missing. There was no significant difference between those who responded “Yes/No” and those who responded, “Do not know/Refused” on key study variables, except for race on item four (stopped contributing to household expenses), when corrected for multiple comparisons (p less than or equal to .001). For this question, people who selected “other” as their race were more likely to not answer this question, χ 2 (3, n = 4,119) = 15.61, p = .001. Considering the sensitivity of chi-square tests to sample size and examining the frequency table, which revealed two out of 105 who selected “other” as their race declined to answer the question, we continued to code nonresponses as missing in analyses. Finally, the yes/no response variable is summed across the five questions to create a single, summary measure score. If the sum score is one or more, financial abuse is indicated.

Validity Measures

Neglect

Neglect was operationalized as the number of instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) that were not being met. The Duke Older Americans Resources and Services IADL scale measured four IADLs, including shopping, meal prep, household chores, and medication management (Fillenbaum & Smyer, 1981). Participants rated whether or not they could perform these skills without assistance. If the skills could not be performed without assistance, they were asked if their needs were being met. It was considered elder neglect if those needs were not met. The responses were coded 0 = “needs not met,” 1 = “needs met.”

Physical and emotional abuse

Physical and emotional abuse was measured using a modified version of the conflict tactics scale (as in Beach et al., 2005; Burnes et al., 2015, 2021). Abuse was indicated if participants reported any instance of abuse. The items were scored “Yes” = 1 and “No” = 0, with a cutoff score of one to indicate abuse. The physical abuse subscale contained 11 items, covering constructs such as being slapped, kicked, or beat up. The psychological subscale included three items, capturing constructs such as being insulted, spited, or threatened.

Data Analytic Plan

We conducted an exploratory factor analysis to explore the dimensionality of the FIVE scale. An analysis of model fit, model comparisons, scree plot, eigenvalues, and theory were utilized to determine the best fitting factor structure. We examined one- and two-parameter logistic (1–2PL) IRT models. One-parameter models allow examination of the difficulty of the items, which is how likely an item is to be endorsed, holding the slope (or discrimination) of the item response curves constant, which implies that the likelihood of endorsing items is similar across items for the latent trait (θ). The two-parameter model frees the discrimination parameters, allowing for different levels of the likelihood of endorsement across items. Items with high discriminations have a steep slope and clearly divide those who are abused compared to those who are not abused. Meanwhile, the opposite is true for low discrimination; that is, items with low discrimination would not be able to classify between those who are and are not abused. This case is more common in measures that do not examine more extreme events such as abuse.

Chi-square tests were conducted to determine whether the two-parameter model provides significantly more information than the one-parameter model, or if it is reasonable to assume similar discrimination of the items. We plotted item characteristics curves (ICC), item information curves (IIC), and test information functions (TIF) to demonstrate how the items relate to and inform the underlying latent construct of financial abuse. Factor analyses were conducted in MPLUS version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017), which analyzes the tetrachoric correlation matrix, which is appropriate for binary response items. We predicted all items would load onto a single factor. IRT models were conducted in the ltm package (Rizopoulos, 2007) in RStudio version 1.3.959.

We conducted correlational analysis to provide evidence of convergent and discriminant validity in relation to neglect (total number of unmet IADL needs and specific IADL needs [shopping, meal prep, household chores, and medication management]), physical abuse, and emotional/psychological abuse. Given the skewed nature of the distributions of abuse (most indicating no abuse), Spearman’s correlations were used in analyses. Finally, reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and IRT methods.

Results

Exploratory Factor Analysis

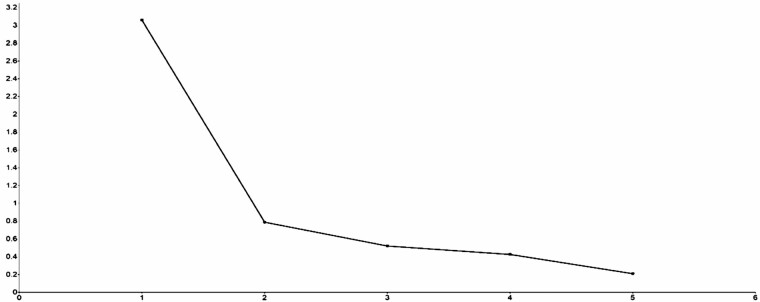

An exploratory factor analysis compared a one-factor model with a two-factor model. Model comparison tests revealed that the two-factor model did not significantly increase model fit (χ2 = 6.81, df = 4, p = .15). Applying the elbow rule to the scree plot suggested two factors, but only the one-factor solution had an eigenvalue greater than one (Figure 1). Taken together, these results suggested that a single factor best represents the FIVE scale. Estimated factor loadings are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Scree plot from confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 2.

Estimated Factor Loadings for 1 and 2 Factor Solutions

| Item number | 1 Factor | 2 Factor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | ||

| Item 1 | 0.77 | 0.31 | 0.51 |

| Item 2 | 0.92 | 0.99 | −0.01 |

| Item 3 | 0.85 | 0.64 | 0.24 |

| Item 4 | 0.79 | −0.01 | 0.88 |

| Item 5 | 0.76 | 0.13 | 0.69 |

Note: Bold items indicate which factor each item best loads on to.

IRT

We computed and compared 1PL and 2PL IRT models. Model fit (p = .40) was not improved when allowing item discriminations to be freely estimated (2PL), as opposed to constrained to equality (1PL). Fit for the 1PL model was assessed using a parametric bootstrap (n = 200) goodness-of-fit test using Pearson’s χ 2 statistic (p = .22), which indicated acceptable model fit (Rizopoulos, 2007). Therefore, it is assumed that the difference in item discriminations (the slope of the line in the ICC graph) is negligible and a single discrimination parameter (α = 2.33) best represented all items. A discrimination of 2.33 is generally regarded as very high, meaning the items discriminated between abuse and not abuse to a very high degree (Baker, 2001). We present the ICC, IIC, and TIF plots for the 1PL model in Figure 2. From these graphs, item one is most likely to be endorsed, while the remaining items are similar in difficulty or levels of endorsement, with item five being the most difficult. Examining the IIC and TIF, the items provided similar amounts of information about the latent trait. Moreover, most of the information came from the extreme positive end of the latent trait, between θ values of +2 and +4, which indicated that the measure assessed more extreme instances, which supports that this scale measures abuse, as opposed to more minor financial offenses. Indeed, 99.7% of the information from this test was greater than zero, suggesting the test measures instances of abuse, while providing little to no information about nonabusive behaviors. Given the total information of 11.666, the measure of IRT reliability was 0.91.

Figure 2.

IRT graphs of 1PL model. IRT = item response theory; 1PL = one-parameter logistic model.

The traditional measure of reliability for the measure was low (α Cronbach’s = 0.35), but this result is not problematic as there is little reason to assume a high correlation among endorsing items. Moreover, the IRT model demonstrated excellent fit and reliability. As an example, because someone endorses one item, such as stealing money, it does not necessarily make them more likely to also endorse coercion or impersonation. As such, these are causal, or formative indicators, in which the items predict the latent trait, as opposed to effect or reflective indicators, in which the latent trait predicts the item responses, as would be true for scales with traditionally high reliability (Bollen & Lennox, 1991). For reference, a common causal, or formative indicator is one such as negative life events, in which loss of job and death of a family member measure the same latent construct, but are lowly correlated. Moreover, the difference in reliability estimates demonstrates the benefits of an IRT or a combined IRT and CTT approach to measure reliability, as IRT demonstrates that the measure is very reliable (0.91), despite a low Cronbach’s alpha (0.35; Kim & Feldt, 2010). Given the relative independence of the items and the severity, as denoted by item difficulties at high levels of θ of each item, we propose a cutoff score of one be used to indicate abuse. That is, if any item is answered in the affirmative, abuse is indicated.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Spearman correlations between the financial abuse scale and the total number of unmet IADL needs (neglect) revealed a significant correlation rspearman = −0.10, p < .001 (recalling that 1 = needs met, 0 = needs not met). Looking at the items individually, financial abuse was significantly associated with shopping needs, household needs, and meal prep needs, but not with medication management (rspearmen range −0.1 to −0.08, p < .001). Notably, all of these activities required some form of financial management to be successfully met. Moreover, financial abuse was significantly correlated with instances of physical abuse, rspearman = 0.15, p < .001, as predicted. However, contrary to predictions, financial abuse was also significantly correlated with instances of emotional/psychological abuse, rspearman = 0.15, p < .001. Moreover, correlations can be used as estimates of effect size. Standard conventions interpret effect sizes of correlations of ≥0.10 as a small effect, ≥0.30 as a moderate effect, and ≥0.50 as a large effect (Cohen, 1988). Thus, the current relationships demonstrate a small but significant effect. Overall, financial abuse seems to co-occur with many other types of abuse.

Discussion and Implications

This study sought to examine the psychometric properties of the FIVE, a novel self-report measure of financial abuse among older adults. The analyses demonstrate sound psychometric properties to confirm the validity of the measure to assess elder financial abuse. As demonstrated, the measure is unidimensional, capturing a single domain―financial abuse. Moreover, given the difficulty of the items, as demonstrated in Figure 2, being 2–3 standard deviations from the mean of the latent construct, and the location of the information from Figure 2, peaking between two and four standard deviations above the mean, this measure only captures events that are less common, as is expected for measures of elder abuse. These results occurred in the context of a population-based, representative sample, which strengthens the overall external validity of the findings.

This scale demonstrated convergent validity with physical abuse and neglect, as predicted given the high co-occurring prevalence of these forms of elder abuse (Jackson & Hafemeister, 2011, 2013). Contrary to predictions, it was also significantly correlated with emotional/psychological abuse. The response data were insufficient to examine relationship between financial abuse and sexual abuse. Thus, based on our findings, it appears that financial abuse often co-occurs with other types of abuse.

Jackson (2018) highlights the difference between measures of prevalence and screening measures. The FIVE scale was initially included in a prevalence study of abuse among a representative sample of older adults. Although brief at five items, prior work on the FIVE scale (Peterson et al., 2014) examined qualitative reports of the abuse experienced if abuse was indicated on the measure and found that the measure successfully captures a wide range of abusive behaviors, lending it face validity in prevalence studies. Specifically, respondents reported 292 discrete financial abuse events, which mapped on to 14 subtypes of financial exploitation. In turn, these 14 subtypes mapped on to the five domains covered by the current measure (Peterson et al., 2014).

Given the brevity of this scale, its successful application in a large-scale prevalence study in a representative population, and the strong psychometric properties, we suggest that the measure can be used in future population-based or large-scale community-based research studies. The brevity of the scale may also lend itself for use in clinical settings as a first line of assessment, although such clinical applications require further data collection and validation work. In these clinical scenarios, however, positive indications based on the FIVE scale could be followed by longer measures such as the OAFEM to provide more specific details about the abuse.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. First, it was not possible to substantiate the abuse in the current sample beyond self-report, although a gold standard elder abuse confirmation procedure remains a common challenge in the field, particularly when conducting survey-based research. Second, the sample was limited to English- and Spanish-speaking older adults in the state of New York, so the results may not generalize to other populations. Given the low frequency of abuse events, it was not possible to conduct measurement invariance tests by age, race, or gender. Future research should examine whether this measure assesses abuse equally across these categories. Third, studies should evaluate the utility of this measure as a screening tool in clinical settings. Finally, as with all of the other measures of financial abuse, the FIVE scale was a self-report measure, though it did correctly identify 10 substantiated cases of abuse (Lachs & Berman, 2011). As such, results of any of these self-report measures likely underestimate the true population prevalence. Future work should verify the validity of this measure with a larger sample of substantiated cases of financial abuse.

In conclusion, this study provides a validated, short-form measure of financial abuse of older adults. With the reduced length, the FIVE scale is appropriate for use in survey research and potentially in clinical settings. Given the serious lack of validated measures in the field of elder abuse both in general and in relation to the issue of financial abuse specifically, this scale fills a significant gap in providing a psychometrically validated measure of financial abuse of older adults.

Contributor Information

David W Hancock, Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York, USA.

David P R Burnes, Factor-Inwentash School of Social Work, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

Karl A Pillemer, College of Human Ecology, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA.

Sara J Czaja, Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York, USA.

Mark S Lachs, Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York, USA.

Funding

The first author (D. W. Hancock) was supported by The Weill Cornell Medicine Research Training Program in Behavioral Geriatrics program (T32-AG049666).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Acierno, R., Hernandez, M. A., Amstadter, A. B., Resnick, H. S., Steve, K., Muzzy, W., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2010). Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 292–297. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2009.163089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acierno, R., Hernandez-Tejada, M. A., Anetzberger, G. J., Loew, D., & Muzzy, W. (2017). The national elder mistreatment study: An 8-year longitudinal study of outcomes. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 29(4), 254–269. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2017.1365031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter, A. B., Zajac, K., Strachan, M., Hernandez, M. A., Kilpatrick, D. G., & Acierno, R. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of elder mistreatment in South Carolina: The South Carolina elder mistreatment study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(15), 2947–2972. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, F. B. (2001). The basics of item response theory (2nd ed.). ERIC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach, S. R., Liu, P. -J., DeLiema, M., Iris, M., Howe, M. J. K., & Conrad, K. J. (2017). Development of short-form measures to assess four types of elder mistreatment: Findings from an evidence-based study of APS elder abuse substantiation decisions. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 29(4), 229–253. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2017.1338171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach, S. R., Schulz, R., Castle, N. G., & Rosen, J. (2010). Financial exploitation and psychological mistreatment among older adults: Differences between African Americans and non-African Americans in a population-based survey. The Gerontologist, 50(6), 744–757. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach, S. R., Schulz, R., Williamson, G. M., Miller, L. S., Weiner, M. F., & Lance, C. E. (2005). Risk factors for potentially harmful informal caregiver behavior. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(2), 255–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, S., Manthorpe, J., Tinker, A., Doyle, M., & Erens, B. (2009). Mistreatment of older people in the United Kingdom: Findings from the first national prevalence study. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 21(1), 1–14. doi: 10.1080/08946560802571870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K., & Lennox, R. (1991). Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural equation perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 110(2), 305–314. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.2.305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burnes, D., Hancock, D. W., Eckenrode, J., Lachs, M. S., & Pillemer, K. (2021). Estimated incidence and factors associated with risk of elder mistreatment in New York State. JAMA Network Open, 4(8), e2117758. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.17758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnes, D., Pillemer, K., Caccamise, P. L., Mason, A., Henderson, C. R.Berman, J., Cook, A. M., Shukoff, D., Brownell, P., Powell, M., Salamone, A., & Lachs, M. S. (2015). Prevalence of and risk factors for elder abuse and neglect in the community: A population-based study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(9), 1906–1912. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, N. G., & Mayer, J. (2000). Elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation: Risk factors and prevention strategies. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 33(2), 5–25. doi: 10.1300/J083v33n02_0214628757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, K. J., Iris, M., Ridings, J. W., Langley, K., & Wilber, K. H. (2010). Self-report measure of financial exploitation of older adults. The Gerontologist, 50(6), 758–773. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum, G. G., & Smyer, M. A. (1981). The development, validity, and reliability of the OARS multidimensional functional assessment questionnaire. Journal of Gerontology, 36(4), 428–4 34. doi: 10.1093/geronj/36.4.428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J., Karch, D., & Crosby, A. (2016). Elder abuse surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended core elements. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). [Google Scholar]

- Hwalek, M. A., & Sengstock, M. C. (1986). Assessing the probability of abuse of the elderly: Toward development of a clinical screening instrument. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 5(2), 153–173. doi: 10.1177/073346488600500205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S. L. (2018). A systematic review of financial exploitation measures in prevalence studies. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37(9), 1150–1188. doi: 10.1177/0733464816650801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S. L., & Hafemeister, T. L. (2011). Risk factors associated with elder abuse: The importance of differentiating by type of elder maltreatment. Violence and Victims, 26(6), 738–757. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.26.6.738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S., & Hafemeister, T. L. (2013). Financial abuse of elderly people vs. other forms of elder abuse: Assessing their dynamics, risk factors, and society’s response. National Institute of Justice Final Report (2011), 1–607. doi: 10.3886/ICPSR29301.v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S., & Feldt, L. S. (2010). The estimation of the IRT reliability coefficient and its lower and upper bounds, with comparisons to CTT reliability statistics. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11(2), 179–188. doi: 10.1007/s12564-009-9062-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs, M., & Berman, J. (2011). Under the radar: New York state elder abuse prevalence study, self-reported relevance and documented case surveys, 1–142. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann, E. O., Leitsch, S. A., & Waite, L. J. (2008). Elder mistreatment in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a nationally representative study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(4), S248–S254. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.4.s248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthorpe, J., Biggs, S., McCreadie, C., Tinker, A., Hills, A., O’Keefe, M., Doyle, M., Constantine, R., Scholes, S., & Erens, B. (2007). The UK national study of abuse and neglect among older people. Nursing Older People, 19(8), 24–26. doi: 10.7748/nop2007.10.19.8.24.c6268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (2017). MPLUS user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Neale, A. V., Hwalek, M. A., Scott, R. O., Sengstock, M. C., & Stahl, C. (1991). Validation of the Hwalek–Sengstock elder abuse screening test. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 10(4), 406–418. doi: 10.1177/073346489101000403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J. C., Burnes, D. P. R., Caccamise, P. L., Mason, A., Henderson, C. R., Wells, M. T., Berman, J., Cook, A. M., Shukoff, D., & Brownell, P. (2014). Financial exploitation of older adults: A population-based prevalence study. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29(12), 1615–1623. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2946-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer, K., Burnes, D., Riffin, C., & Lachs, M. S. (2016). Elder abuse: Global situation, risk factors, and prevention strategies. The Gerontologist, 56(suppl 2), S194–S205. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podnieks, E. (1993). National survey on abuse of the elderly in Canada. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 4(1–2), 5–58. doi: 10.1300/J084v04n01_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rizopoulos, D. (2007). ltm: An R package for latent variable modeling and item response analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 17, 1–25. doi: 10.18637/jss.v017.i05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, M. J., & Mishra, G. D. (2003). Validity of self-report screening scale for elder abuse: Women’s Health Australia Study. The Gerontologist, 43(1), 110–120. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]