Abstract

Combinatorially, intron excision within a given nascent transcript could proceed down any of thousands of paths, each of which would expose different dynamic landscapes of cis-elements and contribute to alternative splicing. In this study, we found that post-transcriptional multi-intron splicing order in human cells is largely predetermined, with most genes spliced in one or a few predominant orders. Strikingly, these orders were conserved across cell types and stages of motor neuron differentiation. Introns flanking alternatively spliced exons were frequently excised last, after their neighboring introns. Perturbations to the spliceosomal U2 snRNA altered the preferred splicing order of many genes, and these alterations were associated with the retention of other introns in the same transcript. In one gene, early removal of specific introns was sufficient to induce delayed excision of three proximal introns, and this delay was caused by two distinct cis-regulatory mechanisms. Together, our results demonstrate that multi-intron splicing order in human cells is predetermined, is influenced by a component of the spliceosome, and ensures splicing fidelity across long pre-mRNAs.

Introduction

Pre-mRNA splicing is an essential regulatory step of gene expression in which introns are removed and exons are ligated to generate mature mRNAs. Human genes contain many introns, and more than 95% of these genes undergo alternative splicing (AS)1,2. Accordingly, pre-mRNA splicing requires intricate mechanisms to coordinate the excision of multiple introns within each nascent transcript. Furthermore, the splicing catalysis timing varies across introns. Sequencing studies have shown that up to 70% of introns are removed co-transcriptionally3,4, whereas the other 30% are excised post-transcriptionally while the nascent transcripts remain associated with chromatin after 3’-end cleavage and polyadenylation3,5,6. Although mRNA isoforms within the mature transcriptome have been explored in many cell types and tissues7,8, it remains unclear how splicing and AS decisions occur across multiple introns of a single transcript to produce these pools of mature isoforms.

The order of intron removal is emerging as a crucial regulatory component of splicing. Because many splicing enhancers and silencers are located within introns9–12, intron excision order determines how long these elements persist within a transcript, where they can influence AS outcomes in cis. How splicing order proceeds across multiple introns within a single transcript remains largely unexplored, and the problem is immense: for the average human gene with eight introns, more than 40,000 possible paths can lead from an unspliced pre-mRNA to a fully spliced transcript. Due to technical limitations of analyzing splicing patterns across many introns, global analyses of intron removal order have thus far been limited to pairs of consecutive introns. These studies have shown that removal occurs largely in a defined order, i.e., one intron of a pair is usually excised before the other13,14. Multi-intron splicing order across more than two introns has been analyzed for a few individual genes by RT-PCR or targeted next-generation sequencing15–18, but because these experiments require complex primer design, they are limited to analyses of a few genes. Long-read transcriptome sequencing has emerged as a promising method for investigating the order of RNA processing events within single RNA molecules14,19,20. However, the low throughput of long-read technologies limited results to aggregate analyses of all introns across all sequenced transcripts. These initial studies have demonstrated that neighboring introns are more likely to have the same excision status than more distant introns, suggesting that removal of proximal introns is coordinated14, but it is unclear whether this coordination extends to larger intron groups and how it impacts AS outcomes.

Splicing is performed by the spliceosome, a complex consisting of five small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) that each contain one small nuclear RNA (snRNA) and several proteins21. Early in spliceosomal assembly, the 5’ splice site (SS) and branch point sequence (BPS) in the pre-mRNA interact with the U1 and U2 snRNAs via sequence complementarity. The relative levels of U1 and U2 snRNAs influence splicing fidelity, as demonstrated by the observation that moderate depletion of U1 and U2 snRNAs causes AS changes that are enriched for exon skipping events22. In mice, a mutation in only one of the five genes encoding U2 snRNA is sufficient to cause significant exon skipping and induces neurodegeneration23. We previously found that introns that are excised later within pairs are enriched for binding of U2 snRNP components14. Moreover, the U2 snRNP is important for synergistic spliceosome assembly across proximal introns in vitro24, suggesting a role for the U2 snRNP in regulating splicing order and coordination.

In this study, we used direct RNA nanopore sequencing (dRNA-seq) to study multi-intron splicing order during post-transcriptional splicing. We found that post-transcriptional splicing is widespread in human cells and frequently occurs in several introns per gene. In addition, we observed that post-transcriptional splicing across three or four proximal introns follows a defined order that is conserved across cell types and stages of human motor neuron differentiation, indicating that splicing order is generally predetermined and not subject to substantial variation. Moreover, U2 snRNA depletion or targeted perturbation of selected introns led to changes in splicing order that were accompanied by splicing defects throughout the resulting splice isoform. For example, out-of-order removal of one intron in the gene IFRD2 was sufficient to increase the retention of several proximal introns through two distinct cis-regulatory mechanisms involving a downstream SS or changes in secondary structure. Together, our results demonstrate that multi-intron splicing order in human cells is often predetermined, regulated by a core component of the spliceosome and pre-mRNA cis-elements, and crucial for splicing fidelity.

Results

Analysis of post-transcriptional splicing by dRNA-seq

To investigate post-transcriptional splicing across entire transcripts, we used nanopore dRNA-seq to analyze chromatin-associated poly(A)-selected RNA from human K562 cells (Fig. 1A). We focused on post-transcriptional splicing because we previously showed that co-transcriptional splicing occurs several kilobases away from transcription14, making it challenging to analyze with the current dRNA-seq read lengths, as most reads corresponding to elongating transcripts are completely unspliced (Extended Data Fig. 1A). Moreover, introns neighboring alternative exons are predominantly excised post-transcriptionally3 and are more likely to be removed second within intron pairs14, suggesting that studying post-transcriptional splicing will shed light on AS.

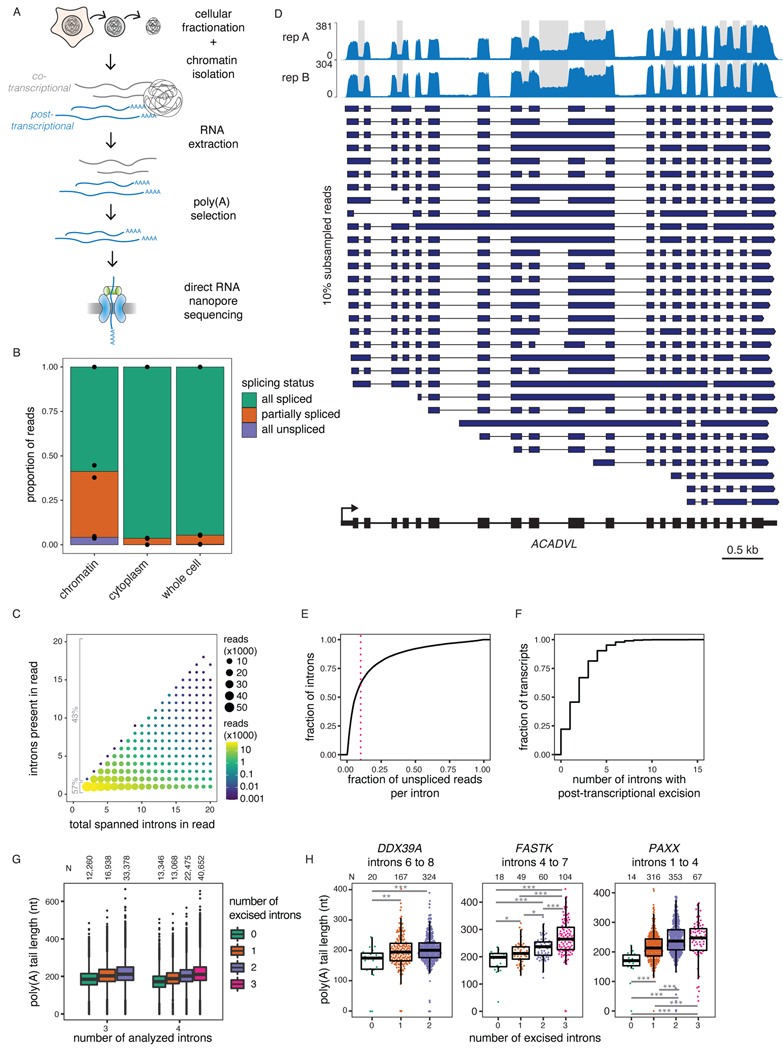

Figure 1. Widespread post-transcriptional splicing in human cells.

A) Schematic depicting the experimental design, adapted from 14. B) Proportion of reads spanning at least two introns that are fully spliced, partially spliced (intermediate isoforms), or fully unspliced in dRNA-seq samples from different cellular compartments. Individual dots represent two biological replicates. C) Post-transcriptionally excised introns in dRNA-seq of poly(A)-selected chromatin-associated RNA. The number of introns present in each read is represented as a function of the total number of introns spanned by the read (excised or not). D) Representative example gene displaying post-transcriptional splicing. Introns with fraction unspliced reads > 0.1 are shaded in grey. The overall coverage track is shown for two biological replicates at the top and 10% randomly sampled reads from replicate B are shown below as dark blue arrows. E) Cumulative distribution function (CDF) showing the fraction of unspliced reads per intron. The red dotted line indicates 10% or more unspliced reads and represents the cutoff used to define post-transcriptional splicing. F) CDF showing the number of post-transcriptionally excised introns per gene. For E) and F), only reads spanning at least two introns were included. G) Distribution of poly(A) tail lengths in chromatin-associated RNA from K562 cells (replicate B). All reads are classified into groups of 3 or 4 introns based on the number of proximal post-transcriptionally excised introns that the read covers (splicing level). Splicing levels were compared using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test (p-value < 10−50 for all comparisons). H) Same as G, but for example individual intron groups. Splicing levels were compared using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test: *: p-value < 0.05; **: p-value < 0.01; ***: p-value < 0.001. Each dot represents one read. In G) and H), boxplots elements are shown as follows: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; In G), points represent outliers.

Using our dataset of 2.65 million aligned reads (Supplemental Table 1), we classified the splicing status of each read spanning at least two introns (1.59 million reads) as being fully spliced, fully unspliced, or partially spliced (hereafter, intermediate isoform reads). More than 35% of multi-intron reads exhibited partial splicing, likely reflecting transcripts that were undergoing RNA processing, compared to less than 5% for cytoplasmic and total RNA (Fig. 1B). We observed that 43% of intermediate isoform reads in chromatin RNA had two or more remaining introns (Fig. 1C), the majority of which were middle introns (i.e., not the first or last introns in the transcript) (Extended Data Fig. 1B). We found that 38% of introns were excised post-transcriptionally, defined as being present in at least 10% of reads (Fig. 1D–E, Extended Data Fig. 1C–D). Globally, more than 75% of transcripts contained at least one intron exhibiting post-transcriptional excision (Fig. 1F), whereas over 25% of transcripts contained three or more. Thus, post-transcriptional splicing of polyadenylated, chromatin-associated RNA is a widespread feature of most transcripts.

Intermediate isoforms are undergoing active processing

Introns that are not excised while the transcript is associated with chromatin are likely removed eventually, as most transcribed pre-mRNA splice junctions are successfully spliced25. However, a small subset of post-transcriptionally excised introns (detained introns) are retained in nuclear polyadenylated transcripts, which can be degraded in an exosome-dependent manner26–29. Upon depletion of the nuclear exosome catalytic subunit, EXOSC10 (Extended Data Fig. 1E–F), we observed neither large-scale changes in global intron retention (Extended Data Fig. 1G) nor upregulation of most intermediate isoforms (Extended Data Fig. 1H, Supplemental Table 2), indicating that these transcripts are not frequently targeted for EXOSC10-dependent nuclear RNA decay.

As an orthogonal approach to confirm that intermediate isoforms represent RNAs that are actively undergoing processing, we took advantage of dRNA-seq estimates of the lengths of poly(A) tails30, which are added to the 3’ ends of RNA after co-transcriptional nascent RNA cleavage. We observed that poly(A) tails grew as splicing progressed, both globally and for individual genes (Fig. 1G–H, Extended Data Fig. 1I). These observations demonstrate that splicing and polyadenylation occur in parallel and emphasize that intermediate isoform reads represent RNAs engaged in active processing.

Splicing order is defined across multiple introns

In many genes with more than one post-transcriptionally excised intron, certain introns were present only if another intron was also present. For example, in DDX39A, intron 8 was almost exclusively present when intron 6 was also present (Fig. 2A). These observations suggest that removal of some introns occurs only after other introns have been excised from the transcript and that post-transcriptional splicing follows a defined order.

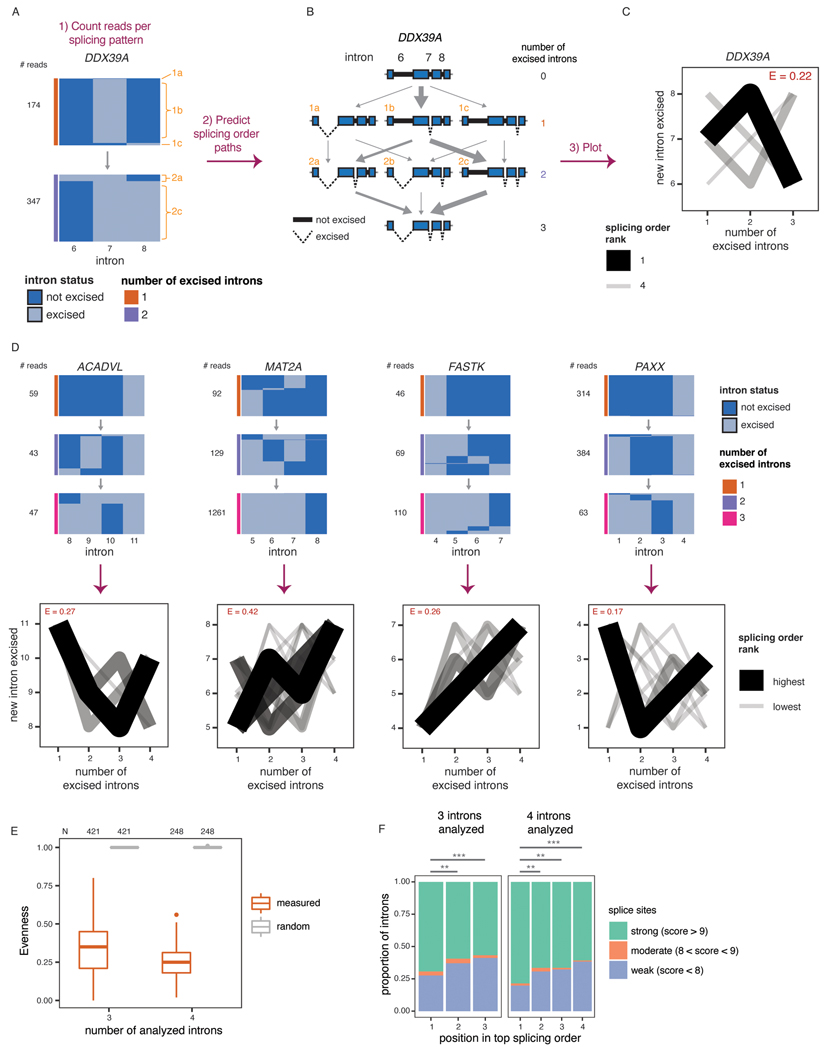

Figure 2. Post-transcriptional splicing follows a defined order.

A) Representation of all reads mapping to introns 6 to 8 of DDX39A in one representative biological replicate. Each column represents one intron. The horizontal blocks represent the proportion of reads for each intermediate isoform, with the total number of reads shown on the left. Orange numbers identify each intermediate isoform. B) Schematic of splicing order analysis of introns 6 to 8 of DDX39A. Each possible intermediate isoform, from fully unspliced to fully spliced, is depicted according to the number of excised introns. Arrows indicate the possible paths to go from one intermediate isoform to another. Intermediate isoforms are numbered in orange as in A). C) Splicing order plot for DDX39A introns 6 to 8. The thickness and opacity of the lines are proportional to the frequency at which each splicing order is used, with the top ranked order per intron group set to the maximum thickness and opacity. The evenness (E) is shown in red font. D) Top: Representation of all reads mapping to four example intron groups, as in A), in one representative biological replicate. Bottom: Splicing order plots for 4 example intron groups, shown as in C). E) Evenness of splicing order across all analyzed intron groups, separated by the number of introns in each group (3 or 4). Boxplots elements are shown as follows: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. F) Proportion of introns with strong, moderate or weak splice sites as a function of their position in the top ranked splicing order. Groups were compared using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test: **: p-value < 0.01; ***: p-value < 0.001. See Supplementary Note 1 for definition of strong, moderate and weak splice sites.

To perform a broader analysis of post-transcriptional splicing order, we identified sets of three or four introns (“intron groups”) undergoing post-transcriptional splicing within a single transcript. We developed an algorithm to predict the most frequent orders in which intron groups are removed to go from fully unspliced to fully spliced. Our method calculates the frequency of each pre-mRNA intermediate isoform, assembles the possible splicing orders, predicts the relative flux through each one, and assigns them a score so that all orders can be ranked (Fig. 2A–C). For example, for introns 6 to 8 in DDX39A, the relative frequencies of intermediate isoforms suggested that intron 7 is usually excised first, followed by intron 8 and finally intron 6 (Fig. 2A–C). Indeed, ranking the splicing order scores revealed that of the six possible paths, splicing followed one order predominantly, with a couple of other orders used much more rarely. We observed similar results for groups of four introns in ACADVL, MAT2A, FASTK and PAXX (Fig. 2D), in which one or a few orders predominated relative to the 24 possible paths. dRNA-seq read lengths and throughput restrictions limited a global analysis to shorter introns in highly expressed genes (Extended Data Fig. 2A–B). Nevertheless, applying this approach to the entire dataset, we obtained reproducible splicing orders for 669 distinct intron groups in 325 genes (Extended Data Fig. 2C–G, Supplemental Table 3). Although the introns in these groups share features of detained introns (Extended Data Fig. 2A), the majority do not overlap with previously identified detained introns31 (Extended Data Fig. 2H–J).

To quantify the extent to which splicing order is defined in each intron group, we computed a diversity measure, evenness, based on the Shannon diversity index32,33. A high evenness value (close to 1) indicates that more splicing orders are being used and that they tend to be used at a similar frequency, while lower values indicate that a smaller number of orders are preferred. We found that evenness values from observed splicing orders displayed a median close to 0.25 or 0.35 for groups of three or four introns, respectively (Fig. 2C–E, Extended Data Fig. 3A, Supplemental Table 4), while the evenness values for simulated random intermediate isoforms were near 1. The highest evenness values in our dataset were 0.56 (four introns) and 0.8 (three introns); in these cases, more than one order was used with high frequency (Extended Data Fig. 3B); however, this still represented only a subset of the possible splicing orders. Evenness was independent from sequencing depth (Extended Data Fig. 3C–E). Accordingly, the top splicing order per intron group was consistent with splicing index or splicing kinetis from short-read nascent RNA sequencing14 (Extended Data Fig. 4A–C). Splicing order within intron pairs was also strongly correlated with nanopore analysis of co-transcriptional processing (nano-COP)14 (Extended Data Fig. 4D–E). Introns that were removed later tended to be slightly longer and to have weaker splice sites (Fig. 2F, Extended Data Fig. 4F–G). Introns located first in transcripts tended to be removed later, consistent with previous reports4,34,35, while last introns were slightly more likely to be removed earlier (Extended Data Fig. 4H–I). Together, these findings indicate that multi-intron post-transcriptional splicing converges towards one or a few predominant and predetermined orders per intron group.

Splicing order is largely conserved across cell types

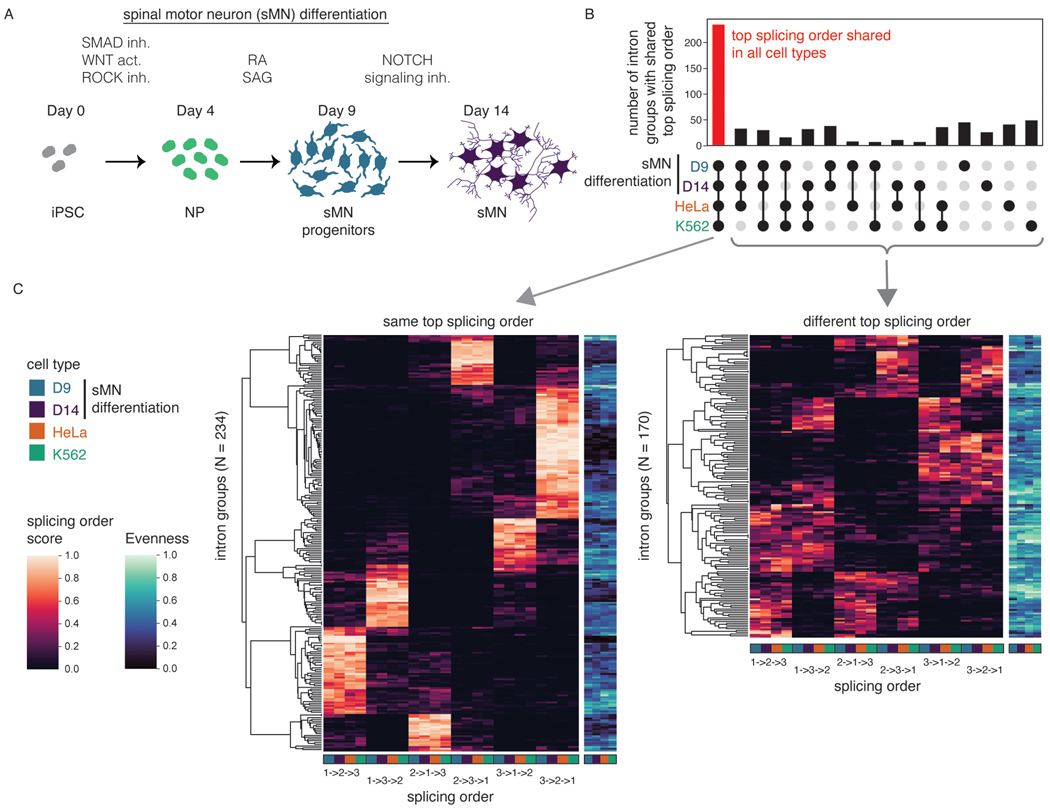

Introns flanking alternative exons (AS introns) are enriched in post-transcriptionally excised introns3, but the order in which these introns are removed relative to other post-transcriptionally excised proximal introns and how this influences AS remain unknown. Changes in AS are abundant during neurogenesis36 and several splicing factors are essential for proper motor neuron development and function in mice37–39. Thus, we sought to investigate the interplay between AS and splicing order during the differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) to spinal motor neurons (sMN)40. Short-read RNA-seq of chromatin-associated RNA at days 0, 4, 9, and 14 of differentiation (Fig. 3A)showed the most differences in gene expression and alternative exon inclusion between days 9 and 14 (Extended Data Fig. 5C), thus we collected deeply covered dRNA-seq of poly(A)-selected chromatin-associated RNA at those two timepoints. The majority of intron groups (82%) that were commonly expressed used the same top splicing order at both timepoints, revealing that splicing order is largely conserved across differentiation (Extended Data Fig. 5D–E). Remarkably, this was also the case when comparing splicing order between K562 cells, HeLa cells and the two sMN differentiation timepoints (Fig. 3B–C, Extended Data Fig. 5E, Supplemental Table 5). Intron groups that did not share the same top splicing order typically had higher evenness and displayed 2–3 predominant splicing orders that were shared across cell types, with moderate differences leading to having a different top splicing order (Fig. 3C, Extended Data Fig. 5F). Thus, splicing order is largely conserved between cancer cell lines and non-cancer cell types and throughout sMN differentiation, indicating that splicing follows preferred orders with low inter-cell type variability.

Figure 3. Splicing order is consistent across cell types.

A) Schematic of the differentiation of spinal motor neurons (sMN) from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC). NP: neural progenitors, inh: inhibitor, act: activator, RA: retinoic acid, SAG: Smoothened agonist. Schematic was made with images from https://smart.servier.com/. B) UpSet plot showing the overlap in top splicing order between K562 cells, HeLa cells, and the two later sMN differentiation timepoints. C) Heatmap displaying hierarchical clustering of intron groups (rows) using all possible splicing orders (columns) across cell types. Numbers within splicing orders (x-axis) indicate the relative position of each intron in the group from the 5’ to the 3’-end. Intron groups are separated based on whether they show the same or a different top splicing order across cell types. Evenness is also shown for each intron group (heatmap in blue shades).

Introns flanking alternative exons tend to be removed last

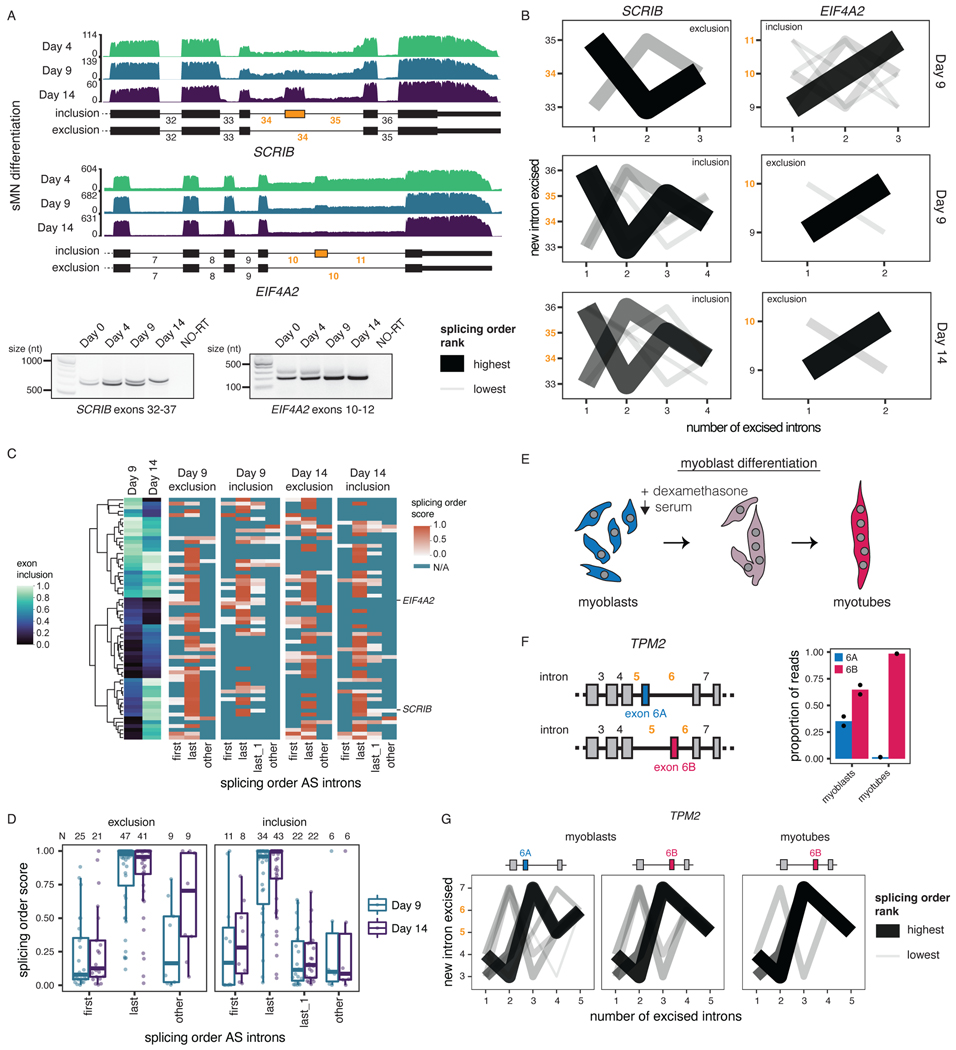

Our data revealed that AS remodeling is widespread during human sMN differentiation: we identified 1,721 distinct cassette exons with inclusion levels that changed significantly between at least two timepoints (Supplemental Table 6, Fig. 4A, Extended Data Fig. 5G). To investigate connections between AS and splicing order, we defined intron groups consisting of the AS introns surrounding an alternative cassette exon, and the upstream and/or downstream introns. For each intron group, we computed splicing order separately for the isoforms in which the alternative exon is included (“inclusion” isoform) or excluded (“exclusion” isoform) (Supplemental Table 7). Interestingly, whether or not the alternative exon was included, introns were generally removed in the same order (Fig. 4B–C, Extended Data Fig. 6A–B). Splicing order was also largely consistent between the same isoform at different timepoints (Extended Data Fig. 6A–B). Furthermore, the introns flanking the alternative exon were most often excised last (Fig. 4B–D, Extended Data Fig. 6A). In a smaller number of intron groups (Extended Data Fig. 5G), AS introns were removed earlier in the top ranked order, but remained at the same positions regardless of inclusion or exclusion. Moreover, inclusion and exclusion isoforms had comparable splicing order evenness overall (Extended Data Fig. 6C). Later removal of AS introns was also observed in short-read RNA-seq of chromatin-associated RNA (Extended Data Fig. 6D).

Figure 4. Splicing order is consistent between alternative isoforms and displays later removal of AS introns.

A) Top: dRNA-seq coverage tracks of one representative biological replicate for two example alternative cassette exons (yellow) with differential inclusion during sMN differentiation. AS introns are shown in yellow font throughout the figure. Bottom: Validation of AS events by RT-PCR of total RNA. The region amplified by PCR is indicated below each gel. NO-RT: no reverse transcriptase control. B) Splicing order plots for two intron groups that contain AS introns, shown separately for inclusion and exclusion of the alternative exon and for each timepoint that had sufficient coverage for a given isoform. C) Left: Heatmap displaying hierarchical clustering of inclusion levels from short-read RNA-seq for exons that are differentially included between Days 9 and 14 and for which splicing order was computed. Right: Heatmap displaying the summed splicing order scores of AS introns for exclusion and inclusion isoforms at each timepoint. Rows represent intron groups and are ordered according to the exon inclusion heatmap. N/A indicate orders that were not observed for an intron group or for which splicing order could not be computed because of low coverage. D) Distribution of summed splicing order scores for all the possible splicing orders of AS introns shown in C). Boxplots elements are shown as follows: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, intron groups. E) Schematic of human myoblasts differentiation into myotubes. F) Left: Schematic representation of TPM2 isoforms with mutually exclusive exons 6A and 6B. Right: Proportion of reads mapping to each TPM2 isoform in cDNA-PCR nanopore sequencing of chromatin-associated RNA from undifferentiated myoblasts and myotubes. G) Splicing order plots for the two TPM2 alternative isoforms in myoblasts and the only isoform expressed in myotubes.

We next investigated how splicing order accommodates mutually exclusive exons (MXEs), which are a rarer42 and more complex type of AS. Of the four MXE events that are differentially regulated between Days 9 and 14 and for which we could compute splicing order, two corresponding intron groups showed a splicing order reversal for the introns flanking the MXEs (MXE introns) (Extended Data Fig. 6E). Similarly, analysis of a well-characterized MXE event in the gene TPM243 during myoblast differentiation revealed that the excision order of the MXE introns was reversed between the two isoforms (Fig. 4G). Nevertheless, the MXE introns were removed last (Fig. 4G), consistent with the results obtained for other AS introns. Thus, the splicing order of introns involved in complex AS patterns may rearrange locally to enable some MXEs, while maintaining the same order within the broader intron group context. Altogether, these results indicate that, for the most part, splicing order is not differentially regulated between different isoforms, but rather programmed for the AS introns being removed later, further emphasizing the deterministic nature of splicing order.

U2 snRNA depletion modifies splicing order

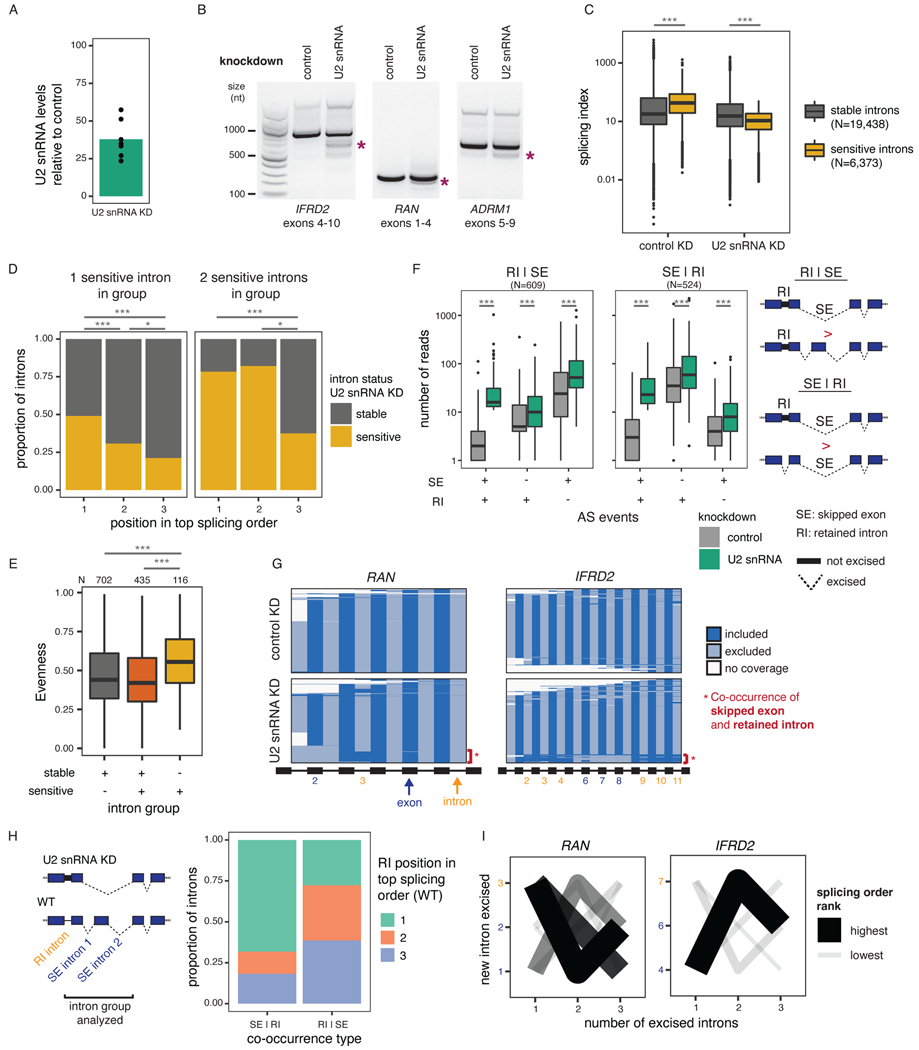

Given that splicing order is largely conserved across cell types and among alternative isoforms, we sought to investigate the consequences of disrupting intron removal order. We previously reported that U2 snRNP binding is correlated with splicing order of intron pairs14, so we depleted U2 snRNA in HeLa cells to ask whether U2 snRNP levels control splicing order. We used an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO)22 to reduce U2 snRNA levels in HeLa cells by ~25–50% (Fig. 5A). Importantly, we observed no difference in RNA polymerase II promoter-proximal pausing index between the control and U2 snRNA knockdown (KD) (Extended Data Fig. 7A), indicating that this modest U2 snRNA depletion did not affect transcription dynamics comparible to a strong U2 snRNP inhibition by the small molecule pladienolide B44. Global co-transcriptional splicing kinetics and splicing order were not affected14 (Extended Data Fig. 7B-C). However, short-read RNA-seq revealed numerous retained introns (RIs) and skipped exons (SEs) (Fig. 5B–C, Extended Data Fig. 7D), as previously reported22. Globally, introns retained upon U2 snRNA KD had a higher splicing index in control cells than unaffected introns (Fig. 5C, Extended Data Fig. 7D), suggesting that introns that are sensitive to U2 snRNA KD are normally excised rapidly and that U2 snRNA KD disrupts splicing order in the affected transcripts. Consistently, when inspecting the splicing orders from controlcells, we found that U2 snRNA KD sensitive introns were more likely to be removed first or second within intron groups, which resulted in a strongly defined splicing order in control cells (Fig. 5D, Extended Data Fig. 7E). Conversely, intron groups composed exclusively of sensitive introns had significantly higher evenness than other intron groups (Fig. 5E, Extended Data Fig. 7F), Thus, when there are several U2 snRNA-dependent introns in an intron group, splicing order is less well defined.

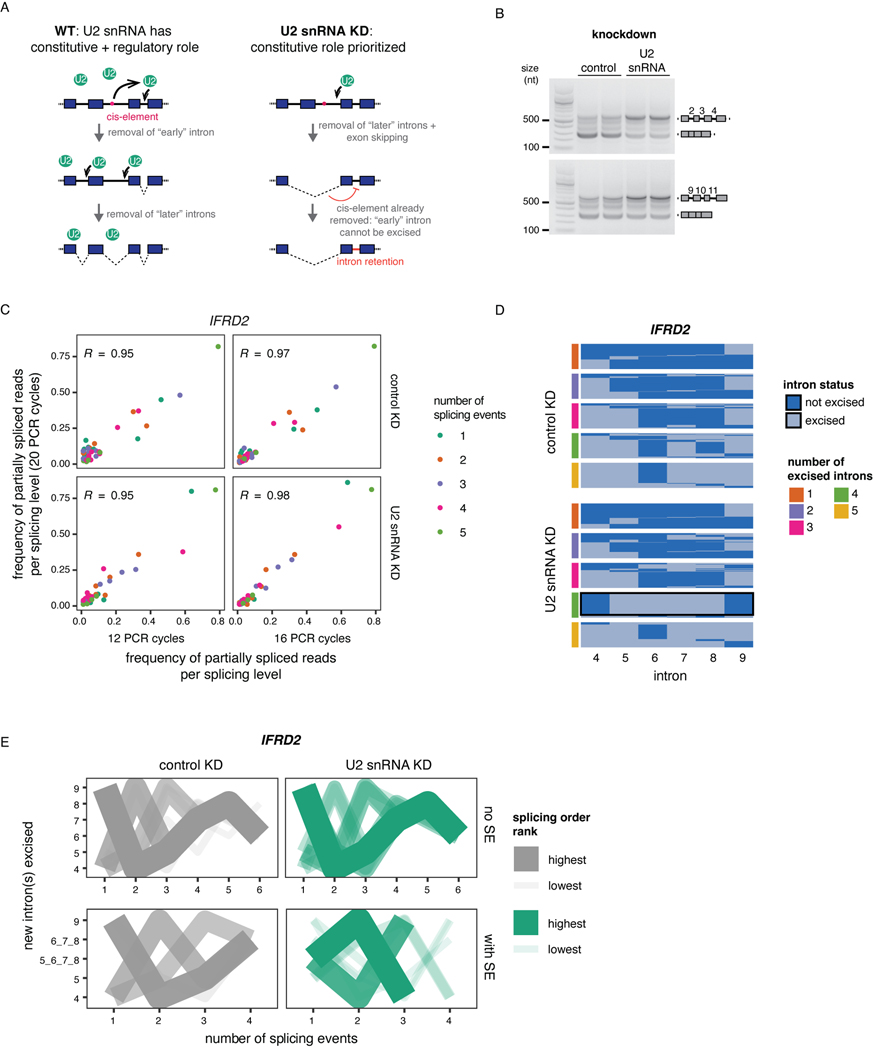

Figure 5. Splicing order changes upon U2 snRNA-mediated exon skipping.

A) qRT-PCR showing reduced U2 snRNA levels relative to control after a 48 hour KD. B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of RT-PCR products showing alternative splicing events upon U2 snRNA KD (asterisks). C) Distribution of total RNA splicing index for stable sensitive introns upon U2 snRNA KDThe average across biological triplicates was used for each intron. D) Proportion of introns that are sensitive or stable upon U2 snRNA knockdown as a function of their position in the top ranked splicing order in WT HeLa cells. Groups were compared using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test.E) Evenness for splicing orders in HeLa WT cells for intron groups that contain stable introns, sensitive introns, or both. . F) Distribution of the number of reads with skipped exons (SE), retained introns (RI), both, or neither. Intron groups are separated based on whether they show “SE | RI” or “RI | SE” upon U2 snRNA KD, as depicted next to the plot. G) Representation of all reads mapping to RAN and IFRD2 upon dRNA-seq of total poly(A)-selected RNA from control or U2 snRNA KD. Each line represents one read and each column represents an intron or an exon. RIs and SEs in the U2 snRNA KD are shown as yellow or dark blue numbers, respectively. H) Proportion of introns retained upon U2 snRNA knockdown as a function of their position in the top ranked splicing order in WT HeLa cells, for intron groups composed of one intron involved in intron retention and two introns involved in exon skipping. I) Splicing order plots for RAN and IFRD2 in WT HeLa cells, for groups containing introns involved in exon skipping (dark blue font) and intron retention (orange font) upon U2 snRNA KD. In C), E) and F), boxplots elements are shown as follows: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. In D), E) and F), groups were compared using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. *: p-value < 0.05; ***: p-value < 0.001.

We observed that genes with RIs were more likely to also contain SEs upon U2 snRNA KD (Extended Data Fig. 7G). mRNA dRNA-seq showed that for most genes with RIs and SEs upon U2 snRNA KD, these two events frequently occurred together on the same RNA molecules (Fig. 5F–G, Extended Data Fig. 7H, Supplemental Table 8). Interestingly, in intron groups where SEs were more frequent than RIs upon U2 snRNA KD, the introns involved in RIs were largely removed first in WT cells, with the introns flanking SEs excised later (Fig. 5H–I, Extended Data Fig. 7I, Supplemental Table 9). Thus, U2 snRNA-mediated AS is associated with splicing order changes in which introns flanking frequent SEs tend to be removed earlier than normal, whereas RI excision, which normally occurs earlier, is delayed or inhibited. These data suggest that introns that rely strongly on U2 snRNA are normally removed early. When U2 snRNA levels are limiting, these “early” introns may no longer be favored for removal, with the “late” introns being removed earlier as part of widespread exon skipping events. This would further inhibit rproximal “early” introns removal that typically rely on cis-elements in the “late” introns (Extended Data Fig. 8A). Our findings indicate that splicing order is regulated by the spliceosome itself and underscore the importance of a preferred splicing order for controlling the cis-element landscape during splicing regulation.

Splicing order-dependent intron retention in IFRD2

To investigate how splicing order changes lead to intron retention, we analyzed splicing of IFRD2 transcripts, in which skipping of exons 6–8 upon U2 snRNA KD was almost always associated with retention of three flanking introns on each side (introns 2–4 and 9–11) (Fig. 5G, Extended Data Fig. 8B). Using a targeted PCR-based approach to study splicing order of introns 4–9 in this gene with greater detail (Extended Data Fig. 8C), we observed that in normal conditions, introns 4 and 9 were usually removed first and introns 6–8 were removed later (Extended Data Fig. 8D–E). However, when U2 snRNA-mediated exon skipping occurred, removing introns 5–8 together, splicing order tended to be reversed, with introns 5–8 excised before introns 4 and 9 (Extended Data Fig. 8D–E).

To understand how splicing order determines the final isoform in IFRD2, we used ASOs to artificially alter IFRD2 splicing order by blocking the 3’SS of introns 4, 5, and 9 individually or in combination (Fig. 6A, Extended Data Fig. 9A–C). When we disrupted the predominant IFRD2 splicing order, in which intron 9 is removed first (Extended Data Fig. 8E), by blocking the 3’SS of intron 9, exon skipping did not co-occur (Fig. 6B). However, impeding the second and third most frequent splicing orders by simultaneously targeting the 3’ SSs of introns 4 and 5 led to a large exon skipping event (removal of introns 4–8) that was associated with intron 9 retention(Fig. 6B–C). Intron 9 was rarely retained on its own (Extended Data Fig. 9C), suggesting that the SE event drives intron 9 retention. These AS patterns were similar to what we observed in the U2 snRNA KD and indicate that alterations in splicing order of upstream introns are sufficient to elicit intron 9 retention.

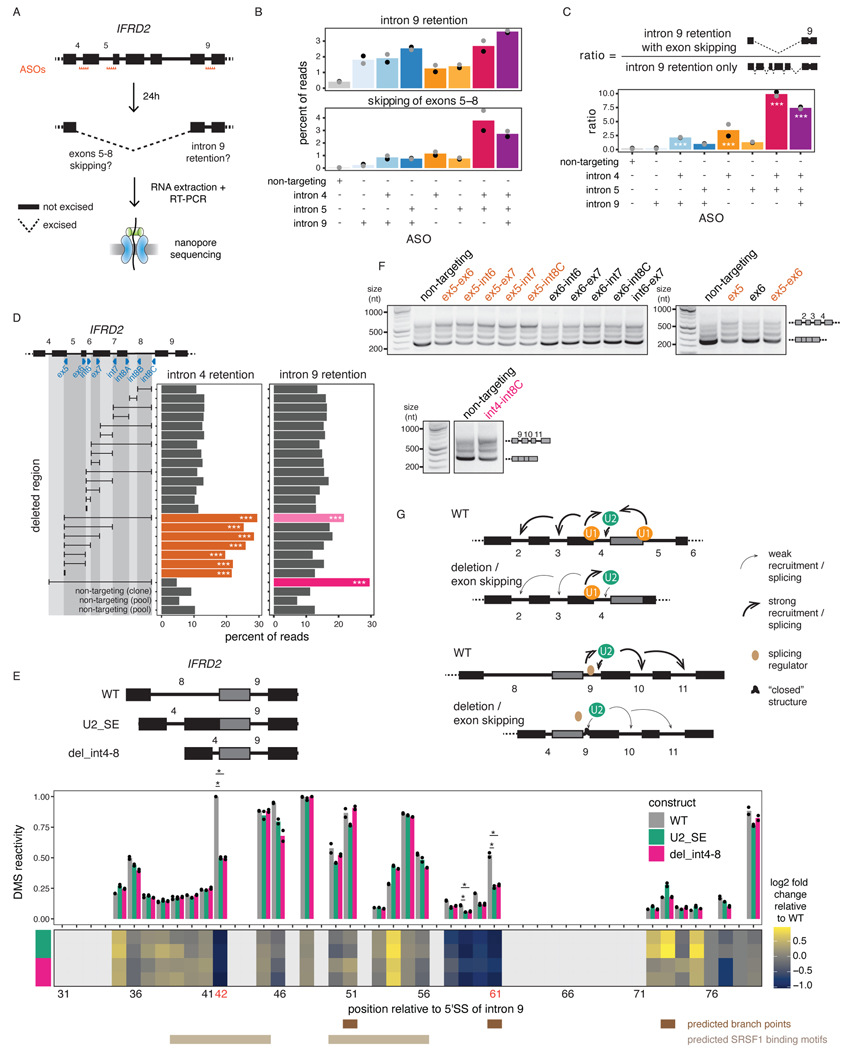

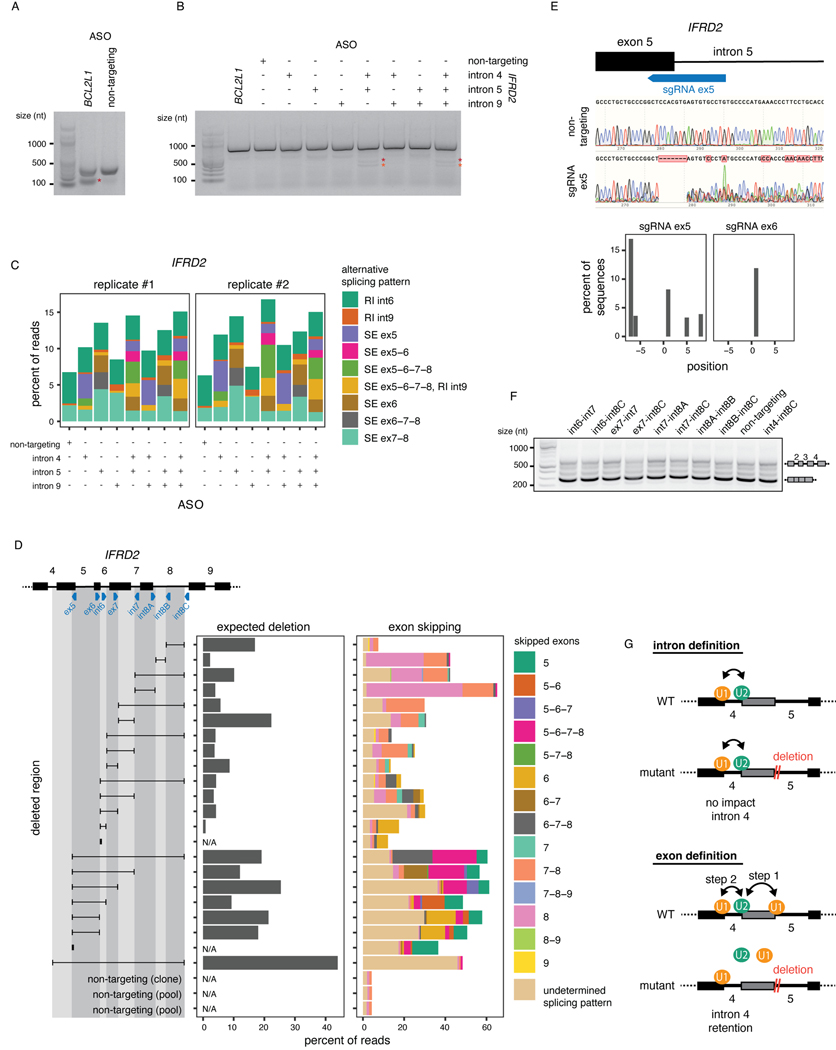

Figure 6. Perturbation of one intron disrupts excision of proximal introns.

A) Schematic of the experimental design for B) and C), adapted from 14. B) Levels of intron 9 retention or exons 5–8 skipping upon treatment with ASO(s) targeting IFRD2. Dots indicate biological replicates. Each ASO treatment was compared to the control using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test (p-value < 10−16 for all comparisons). C) Ratio of the number of reads with intron 9 retention and exons 5–8 skipping relative to the number of reads with intron 9 retention only upon treatment with ASO(s) targeting IFRD2. Dots indicate biological replicates. A one-sided binomial test was used to determine whether intron 9 retention occurs more frequently with exon skipping than expected by chance. ***: p-value < 0.001 and ratio >= 2. D) Percent of reads showing intron 4 or 9 retention upon deletion tiling of IFRD2 using CRISPR-Cas9 editing. Deletions are shown as a black horizontal line delimited by vertical lines aligned to the sgRNA(s) used (blue triangles). A one-sided binomial test was used to compare the frequency of intron retention in each deletion relative to the mean frequency across non-targeting controls. ***: p-value < 0.001 and fold change >= 2. E) Top: In vitro transcribed RNAs used for DMS-MaPseq. Middle: DMS-MaPseq reactivity for nucleotides 30 to 80 of IFRD2 intron 9. Individual dots represent two biological replicates. Bottom: Heatmap showing the log2 fold change of DMS reactivity in U2_SE or del_int4–8 relative to WT. Positions corresponding to G’s and T’s are shown in light grey. Positions where the largest fold change is observed in both mutated constructs are shown in orange font. Predicted branch points46,60 and the two predicted SRSF1 binding sites (ESEFinder47) with the highest scores are shown. Reactivities were compared with a two-sided Student’s t-test. *: p-value < 0.05 and fold change relative to WT >= 2. F) Agarose gel electrophoresis showing the RT-PCR products from amplification of introns 2 to 4 of IFRD2. Deletions involving the end of exon 5 are shown in orange font. G) Working models for the two mechanisms regulating excision of introns 4 and 9.

Distinct cis-regulatory mechanisms impact splicing fidelity

We postulated that delayed intron removal upon U2 snRNA KD (e.g. IFRD2 introns 4 and 9) was due to the premature removal of cis-elements in proximal regions (e.g. IFRD2 introns 5 through 8), which are necessary to stimulate their excision (Extended Data Fig. 8A). To test this hypothesis, we used CRISPR-Cas9 and dual sgRNAs to introduce overlapping deletions spanning IFRD2 introns 5 through 8 (Fig. 6D, Extended Data Fig. 9D–E). Interestingly, deleting as few as 7 nt near the 5’SS of intron 5 was sufficient to increase intron 4 retention (Fig. 6D), indicating that an intact and unspliced 5’SS in the downstream intron is critical for proper intron 4 excision. By contrast, intron 9 retention only occurred when the entire region of interest was deleted (Fig. 6D), suggesting that no single sequence in the upstream introns stimulates intron 9 removal.

To determine whether changes in RNA conformation underlie intron 9 retention, we performed in vitro dimethyl sulfate (DMS) mutational profiling with sequencing (DMS-MaPseq)45, in which unpaired adenosines and cytosines are modified by DMS and high DMS reactivity is indicative of nucleotides that are frequently single-stranded. To investigate the structure of intron 9 in the presence of different upstream contexts, we in vitro transcribed three RNAs: the unspliced WT IFRD2 transcript from exons 8 to 10 (WT), the transcript produced as a result of U2 snRNA-mediated exon skipping (U2_SE), and the transcript with the largest CRISPR-induced deletion (del_int4–8) (Fig. 6E). DMS reactivity was significantly reduced at one of the predicted intron 9 branch point adenosines46 in the U2_SE and del_int4–8 constructs relative to WT (Fig. 6E, Extended Data Fig. 10), suggesting reduced availability for U2 snRNA binding. Moreover, a position in intron 9 that was highly reactive in the WT, indicating that it is normally unpaired, exhibited a substantial decrease in reactivity in both alternative constructs (Fig. 6E, Extended Data Fig. 10). This position overlaps with a predicted splicing enhancer bound by the splicing factor SRSF1 (ESEFinder47), and its high reactivity in the WT construct is consistent with the reported preference of SRSF1 for binding single-stranded RNA48–50. Thus, our data suggest that intron 9 is more open at certain positions in the WT sequence, but when it is in closer proximity to exon 4 upon upstream exon skipping or deletion, structural rearrangements render it less accessible. Together, these results demonstrate that two different mechanisms regulate introns 4 and 9 excision. In both cases, however, early intron removal, either through splicing or a deletion, induced retention of introns that are normally excised earlier.

Finally, we asked whether intron retention is perpetuated further down the transcript, as observed upon U2 snRNA KD (Fig. 5G, Extended Data Fig. 8B). Remarkably, deletions that induced intron 4 or 9 retention also exhibited higher levels of retention of introns 2 and 3 or 10 and 11, respectively (Fig. 6F, Extended Data Fig. 9F). Together, our findings indicate a strong interdependency in removal of IFRD2 introns (Fig. 6G), consistent with coordinated splicing of neighboring introns14 and highlighting the importance of maintaining proper splicing order to generate a fully spliced mature mRNA.

Discussion

Here, we combined dRNA-seq with a novel algorithm to show that post-transcriptional multi-intron splicing order is predetermined and conserved across cell types. We found that splicing order can be perturbed through modulation of U2 snRNA levels, direct physical SS inhibition, or genomic deletion, resulting in long-range disruptions in cis that affect many introns along the transcript. These results underscore the coordinated nature of the many splicing events that occur along a transcript and demonstrate that perturbing the excision of a single intron can have far-reaching and long-lasting consequences on the final isoform.

Our findings expand on previous studies showing that splicing order is defined for pairs of consecutive introns transcriptome-wide13,14,51, as well as with single-gene experiments demonstrating that multiple introns within a given transcript are predominantly excised in one or a few orders15–17. We observed that AS introns are most often removed last, after their neighbors, suggesting that splicing order functions to predispose these introns to be excised last no matter the final isoform. This may allow more time for splicing regulators to bind to these introns and steer the splice site choice, or may instead represent a reservoir of almost mature transcripts that can be fully spliced into either isoform depending on cellular needs.

Due to the current read length of dRNA-seq, we were limited to analyzing groups of three or four proximal introns that are shorter than the genomic average. Consequently, our findings may not hold true for longer introns. Yet, recent work showed that longer introns (>10 kb) are frequently removed in smaller chunks through stochastic recursive splicing, whereas shorter introns (<1.5kb) are mostly excised as complete units52. It is reasonable to speculate that removal of shorter canonical or recursive introns follows a particularly well-defined order, where excision of proximal introns is dependent on one another because of the shorter distance between them. Moreover, due to more limited coverage of dRNA-seq, our analyses were restricted to introns in highly expressed genes. Nonetheless, many of these genes accomplish essential functions in gene expression and metabolism, highlighting the importance of understanding how splicing proceeds across these transcripts. A small proportion of the introns that we analyzed overlapped with previously characterized detained introns, which are a special class of post-transcriptionally excised introns31. While those introns were depleted from introns that are removed first, they were equally likely to be excised in the middle or last positions (Extended Data Fig. 2J). This raises the possibility that splicing may follow a different order when these introns are excised or detained, and that splicing order could contribute to regulation of intron detention. Furthermore, although our analyses focused specifically on post-transcriptional splicing, we observed high correlation between splicing order in this study and intron excision levels in nascent RNA datasets that are enriched for co-transcriptional splicing, suggesting that co- and post-transcriptional splicing may follow a similar order.

The consistency of splicing order across cell types and isoforms suggests that it is robustly defined. Previous analyses of human intron pairs showed that intron length, SS sequence, GC content, sequence motifs, and RNA-binding protein (RBP) binding are associated with splicing order, but that these features cannot explain a considerable fraction of the variance, suggesting that additional factors are at play13,14,53. We found that moderate U2 snRNA depletion changed splicing order in many genes. Interestingly, when we reanalyzed nanopore sequencing data from U2 snRNA mutant (NMF291−/−) mice cerebella54, we found a similar co-occurrence of RIs and SEs (Extended Data Fig. 7J–K), indicating that splicing order is partially determined by the spliceosome and that splicing fidelity is disrupted when splicing order changes in vivo. Our analysis of IFRD2 splicing order suggests that both cis-elements and secondary structure may also play important roles (Fig. 6G), possibly by modulating the landscape of RBPs in introns55,56. Identifying the determinants of splicing order on a broader scale will presumably require mapping of RBP binding and secondary structure in an intermediate isoform–specific manner, in which each transient intermediate isoform can be associated with its specific features. Nanopore sequencing was recently used to detect RBP binding sites57 and reveal isoform-specific secondary structure of mRNA58, suggesting that future experiments combining these approaches and splicing order analyses could uncover the global role of RBPs and RNA structure in determining splicing order.

Removal of short introns (<250 nt) is thought to occur through intron definition, while longer introns (>250 nt) are removed through exon definition, in which splicing factors first bind to the 3’ and 5’SS flanking an exon, followed by cross-intron interactions to enable intron excision59. The latter model is thought to predominate in humans, yet whether shorter human introns use exon or intron definition remains unclear. Our findings that early removal or a small deletion in the 5’SS of IFRD2 intron 5 is sufficient to perturb removal of the upstream intron 4 are consistent with its excision occurring through exon definition (Extended Data Fig. 9G), despite its short size (83 nt). These results also agree with in vitro findings showing that U1 snRNP binding to the intron 5’SS and the next downstream 5’SS exerts synergistic effects on U2 snRNP recruitment to the intron BPS and increases splicing efficiency24.

Upon U2 snRNA knockdown, we observed coordinated retention of multiple introns in IFRD2, indicating that they are either independently regulated by U2 snRNA or that the removal of one intron directly influences excision of its neighbors. Our local perturbations with CRISPR-Cas9 indicate that the latter option is at play, demonstrating for the first time that cis-elements can have longer-range effects on several proximal introns. This observation also adds to the evidence that excision of neighboring introns is coordinated 14. The distance between introns 2 and 5 of IFRD2 is relatively short (~800 nt), and this cross-intron coordination may be a feature of shorter introns. Alternatively, there may be a ripple effect of shorter-range interactions where the 5’SS of intron 5 is essential for intron 4 removal, intron 4 has an element that impacts intron 3, and so on. Further experiments are required to determine how these long-range effects occur and whether the regulation ofn IFRD2 splicing represents a widespread mechanism.

Understanding splicing order has important implications for human health. Intron removal order across several introns influences the splicing outcome of disease-causing mutations15,16, indicating that knowledge of splicing order could help interpret the impact of genetic variants. Moreover, splicing order can influence the efficiency of ASO-mediated exon skipping, used as a therapeutic strategy17. Consequently, taking splicing order into account could help to devise efficient RNA-based therapeutic approaches by ensuring that splicing fidelity is maintained for all introns in a targeted transcript.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

K562 cells (ATCC, CCL-243) were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 medium (ThermoFisher, 11875119) containing 10% FBS (ThermoFisher, 10437036), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 ug/mL streptomycin (ThermoFisher, 15140122). HeLa S3 cells (ATCC, CCL-2.2) and HEK293T cells (ATCC CRL-3216) were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in DMEM medium (ThermoFisher, 11995073) containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 ug/mL streptomycin. Human myoblasts from anonymous healthy control samples were a kind gift from Dr. Brendan Battersby (Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki). Myoblasts were grown in Human Skeletal Muscle Cell Media with the provided growth supplement (HSkMC Growth Medium Kit, Cell Applications, 151K-500). For differentiation into myotubes, the media was replaced with DMEM (ThermoFisher, 11995073) with 2% heat inactivated horse serum and 0.4 ug/mL dexamethasone and replaced every two days.

Spinal motor neuron differentiation

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) were grown in 2D as a monolayer on a Vitronectin substrate in Stemflex culture medium until they reached a confluence of >90%. iPSC colonies were digested with Accutase for 5 minutes at room temperature until a single cell suspension was obtained and manual cell counts were performed using a hemocytometer. Suspensions were adjusted to a concentration of 1×106 cells/mL and plated into Corning ultra low attachment dishes. The differentiation protocol was adapted from 40. On the day of dissociation (Day 0) cells were resuspended in a neural induction medium ‘N2B27’ with small molecules for dual Smad inhibition (SB431542–10uM and LDN 193189–0.25uM), WNT activation (CHIR99021–3uM), and a ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632–10uM) to generate adequate spheroid formation. The small molecule schedule continued as follows: Day 2–4 (SB431542–10uM, LDN193189–0.25uM, CHIR99021–3uM); Day 4–9 (Retinoic Acid-0.5uM, Smoothened Agonist-0.5uM, Purmorphamine-0.5uM); Day 9–14 (DAPT-10uM; Compound E-0.1uM; Culture One supplement-1x). Time points for collection occurred on days 0, 4, 9, and 14. Cells were dissociated using Accumax (Innovative Cell Technologies, AM105) for 15–20 minutes at room temperature. The reaction was inactivated with Ovomucoid (Papain dissociation kit, Worthington Biochemical Corporation). Cells were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 400g, resuspended in PBS, counted, and centrifuged again to pellet the cells before proceeding to cellular fractionation for purification of chromatin-associated RNA.

RNA collection, poly(A) selection and nanopore dRNA-seq

Materials and methods for cellular fractionation and RNA extraction are described in Supplementary Note 1. Poly(A)+ RNA was purified using the Dynabeads mRNA purification kit (ThermoFisher, 61006) according to manufacturer’s instructions, starting with up to 40 ug of chromatin-associated or nuclear RNA. Direct RNA library preparation was performed using the kit SQK-RNA002 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) with 500–700 ng of poly(A)+ RNA according to manufacturer’s instructions with the following exceptions: the RCS was omitted and replaced with 0.5 uL water and the ligation of the reverse transcription adapter was performed for 15 minutes. Sequencing was performed for up to 72 hours with FLO-MIN106D flow cells on a MinION device in our own laboratory or with FLO-PRO002 on a PromethION device at the Harvard University Bauer Core Facility (Supplemental Table 1). Two biological replicates from K562 chromatin-associated RNA were sequenced. We also analyzed two chromatin RNA replicates as well as two cytoplasmic and two total RNA samples (Supplemental Table 1) that were produced in 66 (GEO accession number GSE208225). For all downstream analyses in K562 cells, replicates 3 and 4 produced in this study were combined into replicate A and replicates 1 and 2 produced in 66 were combined into replicate B (Supplemental Table 1) to increase coverage (Extended Data Fig. 2E–F). For analysis of sMN differentiation, we sequenced biological duplicates or triplicates for days 9 and 14, respectively, while we were limited to sequencing a single biological replicate for day 4 due to lower cell counts at this earlier timepoint. One sample each from Days 9 and 14 was sequenced on a PromethION device, while the other samples were sequenced on a MinION device (Supplemental Table 1). For total RNA from control and U2 snRNA knockdown, single biological replicates were sequenced on a PromethION device.

U2 snRNA knockdown

For U2 snRNA KD, 0.4 million HeLa cells were plated in six-well plates. After 24 hours, cells were transfected with 250 pmoles of antisense oligonucleotide (ASO)22 and 10 uL of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Fisher Scientific, 13–778-030) per well according to manufacturer’s instructions for forward transfection. The ASOs were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) and their sequences are indicated in Supplemental Table 10. Cells were collected 48 hours after transfection and resuspended in 700 uL of Qiazol lysis reagent (Qiagen, 79306) for total RNA extraction or carried forward to cellular fractionation for purification of chromatin-associated RNA.

Splice switching with antisense oligonucleotides

ASOs were ordered from IDT (Supplemental Table 10) with phosphothioate backbones and 2’O-methyl modifications on every base. We used an ASO targeting the 5’SS of BCL2L1 as a positive control (Extended Data Fig. 9A)73 and an ASO targeting HBB, which is not expressed in HeLa cells, as a negative control74. 0.4 million HeLa cells were plated in six-well plates and transfected 24 hours later with 100 nM of ASO and 7.5 uL of Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Fisher Scientific, L3000008) per well according to manufacturer’s instructions for forward transfection. Cells were collected 24 hours after transfection and resuspended in 700 uL of Qiazol lysis reagent for total RNA extraction. All ASO experiments were performed in biological duplicate.

CRISPR-Cas9 editing of IFRD2

sgRNAs targeting IFRD2 were selected using CRISPOR75. Oligonucleotides corresponding to both strands of the sgRNA sequences were annealed and cloned into the plasmid lentiCRISPR v2 (Addgene #52961) as previously described76. For lentiviral packaging, HEK293T cells were grown in six-well plates and transfected with 2 ug lentiCRISPR v2 plasmid, 580 ng pRSV-REV (Addgene #12253), 1.16 ug pMDLg/pRRE (Addgene #12251), 700 ng pMD2.G (Addgene #12259) and 8 ul Lipofectamine 3000 with 8 ul P3000 reagent in 200 uL Opti-MEM medium. Cells were incubated at 37°C and viral media was collected after 48 hours. HeLa cells were transduced in six-well plates with 1.5 mL viral media and 1.5 mL normal media for single sgRNA transductions or with 1.5 mL viral media from each sgRNA for dual sgRNA transductions. In both cases, polybrene was added at a final concentration of 8 ug/ml. Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C and the media was replaced after 24 hours. Puromycin selection (1 ug/ml final concentration) was started after 72 hours and continued for 7 days, with replacement of the selection media every 48 hours. For generation of clonal cell lines, cells were diluted to 0.7 cells/mL, transferred to 96-well plates, and incubated until clones were detected. Genomic DNA was isolated with DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen, 69504).

Nanopore data processing

Live basecalling of nanopore sequencing data was performed with MinKNOW (release 9.06.7 or later). For dRNA-seq data, all reads with a basecalling threshold > 7 were converted into DNA sequences by substituting U to T bases prior to alignment. Reads were aligned to the reference human genome [ENSEMBLE GRCh38 (release-86)] using minimap278 with parameters -ax splice -uf -k14. For cDNA-PCR sequencing, all reads with a basecalling threshold > 8 were aligned to the reference human genome using minimap2 with parameters -ax splice. Uniquely mapped reads were extracted as outlined in 64. Coverage tracks in Figures 1 and 4 and Extended Data Figures 1 and 5 were produced with pyGenomeTracks79. Determination of intron splicing status and additional analyses are described in Supplementary Note 1.

Computation of splicing order

For dRNA-seq in K562 cells, groups of 3 or 4 introns from the RefSeq hg38 annotation were included in the analysis when they met the following criteria in both biological replicates: 1) each intron was present in at least 10 reads; 2) each splicing level, defined as the number of excised introns within each read for the considered intron group, was supported by at least 10 reads that spanned all introns in the considered intron group. This threshold was also required for the first splicing level, where none of the introns were excised. Therefore, at a minimum, each intron group is represented by 10 reads where all introns are present, 10 reads where only one intron has been removed, 10 reads where only two introns have been removed and 10 reads where only three introns have been removed (for groups of 4 introns). If a group of 3 introns was fully encompassed in a group of 4 introns, only the latter was kept for further analysis to avoid duplicates. For duplicated intron groups with the same genomic coordinates within different transcripts, only one instance was kept. For each splicing level , the frequency of each possible intermediate isoform was recorded by dividing the number of reads matching this intermediate isoform by the total number of reads at that splicing level. Next, we iterated through each level , where for each observed intermediate isoform , we identified the intermediate isoform(s) at the previous splicing level from which the isoform under consideration could originate (e.g. EXCISED_EXCISED_PRESENT could originate from PRESENT_EXCISED_PRESENT or EXCISED_PRESENT_PRESENT, see also Fig. 2B). Those intermediate isoforms were connected within a possible splicing order path and their frequencies were recorded. After iterating through each level, the frequencies of patterns supporting each possible splicing order were multiplied to yield the raw splicing order score , where is the total number of intermediate isoforms supporting a given splicing order (4 for groups of 3 introns and 5 for groups of 4 introns):

These raw scores were further divided by the sum of all raw scores for the considered intron group, where is the total number of observed splicing orders for the intron group. This yielded the final splicing order score such that the sum of all scores was equal to 1:

Only introns with “excised” or “not excised / present” statuses were considered for this analysis. For each intron group, Shannon diversity index () and evenness () were calculated as follows, where is the splicing order score for order , is the total number of observed splicing orders and is the total number of possible splicing orders (6 for groups of 3 introns and 24 for groups of 4 introns):

Splicing order plots were produced in R with ggplot2 (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org) with the following command:

To identify reproducible splicing orders in K562 cells, we filtered for orders that showed the same rank in both biological replicates. Splicing order plots in Figure 2 and Extended Data Figure 3 were made using data from biological replicate A. Splicing order scores from both biological replicates are included in Supplemental Table 3.

For comparison of splicing order between different cell types and differentiation timepoints, all biological replicates were combined for each cell type. Groups of three introns present in all cell types being compared were included and the same thresholds and strategy described above were applied. If intron groups containing two alternative exons (and thus different intron-exon junctions) met the coverage thresholds in each cell type, they were analyzed as distinct intron groups with some common introns and some different introns (those flanking the alternative exon). The top splicing order for each cell type was extracted and intersections between each combination of cell types were represented using UpSetPlot (https://upsetplot.readthedocs.io/en/stable/). For representation of all splicing orders (Fig. 3C), absolute intron numbers within the transcript were replaced by relative numbers from 1 to 3 that represent their intron positions within the intron group from 5’ to 3’. Of note, the sMN Day 4 sample did not have sufficient coverage to compute splicing order for most intron groups and was excluded from this analysis.

Computation of splicing order with AS during sMN differentiation

For splicing order of AS introns, we first extracted alternative cassette exons (SE events) that were differentially included between Days 9 and 14 in the poly(A)+ short-read RNA-seq data. We required that the exon have an inclusion level between 0.1 and 0.9 in at least one time point. For the isoform where the exon is included (inclusion isoform), we defined groups of 4 introns composed of the two introns flanking the alternative exon (AS introns), one intron upstream and one intron downstream. For the isoform where the exon is excluded (exclusion isoform), we defined groups of 3 introns composed of the intron overlapping the alternative exon, one intron upstream and one intron downstream. We extracted the GENCODE V38 transcripts that included each intron group and computed splicing status of each intron in the dRNA-seq data as described in Supplementary Note 1. All biological replicates from each timepoint were combined for this analysis. After identification of intermediate isoform reads mapping to these intron groups, we kept all intron groups composed of the AS intron(s) and at least one upstream or downstream intron, and that were covered by at least 5 reads per intermediate splicing level. For duplicated intron groups with the same genomic coordinates, only one instance was kept. If a group of 2 or 3 introns was fully encompassed in a larger intron group, only the latter was kept for further analysis to avoid duplicates. From these intron groups, we computed splicing order as described above. We then defined a “generic” splicing order by identifying the position of the AS introns within the splicing order. For exclusion isoforms, “first” and “last” mean that the AS intron overlapping the alternative exon is removed first or last, respectively. For inclusion isoforms, “first” and “last” mean that both AS introns flanking the alternative exon are removed first and second or last and second-last, respectively, while “last_1” means that one of the AS introns is removed last but the second AS intron is removed earlier than second-last. For both isoform types, “other” means that the AS intron(s) are excised at a position other than first or last. For each of these generic splicing orders, splicing order scores from the initial splicing orders were summed. Intron groups were kept for downstream analyses if splicing order could be computed for both the inclusion and the exclusion isoforms at at least one timepoint [e.g. both isoforms covered at one timepoint (see SCRIB and EIF4A2, Fig. 4B) or one isoform covered at one timepoint and the other isoform covered at the second timepoint (see SLC37A4, Extended Data Fig. 5G)]. For comparison of top splicing orders (Extended Data Fig. 6A), we extracted splicing orders that were ranked first and compared their generic order classification between exclusion and inclusion isoforms for each timepoint or between Days 9 and 14 for each isoform. Of note, the sMN Day 4 sample did not have sufficient coverage to compute splicing order for most intron groups and was excluded from these analyses. For comparison of splicing order to short-read RNA-seq, splicing index was computed as outlined above for each intron within the defined intron groups that had more than 20 reads spanning exon-intron junctions.

Other experiments and analyses

Additional experimental procedures and analyses are described in Supplementary Note 1.

Statistics and reproducibility

All experiments were repeated independently at least twice with similar results. All experiments included biological duplicates or triplicates, except for CRISPR-Cas9 editing experiments, where individual deletions that overlapped with one another provided reproducibility for the phenotype observed. No statistical methods were used to predetermine the sample size. The experiments were not randomized, and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Data availability

Raw and processed sequencing data are available from the Gene Expression Omnibus at accession number GSE232455. Source Data is provided for every Figure and Extended Data Figure.

Code availability

Code for analysis of all nanopore sequencing data will is available at https://github.com/churchmanlab/splicing_order.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1.

(related to Figure 1). A) Distribution of RNA 3’ ends based on read splicing status in nano-COP data14 from K562 cells. 3’end features are defined as in 14. B) UpSet plot showing the position of introns present in partially spliced reads from dRNA-seq of poly(A)-selected chromatin-associated RNA. “Middle” includes introns that are not the first or last intron in a transcript. Two biological replicates are displayed. C) Scatter plot of the fraction of unspliced reads per intron between two biological replicates. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is shown on the plot (p-value < 0.0001, 95% confidence interval 0.948–0.950). Only reads spanning two introns or more are included. D) Coverage tracks from dRNA-seq of poly(A)-selected chromatin-associated RNA for three genes displaying various levels of post-transcriptional splicing. Introns with fraction of unspliced reads > 0.1 are shaded in grey. E) EXOSC10 mRNA levels and F) RNA levels of two promoter upstream transcripts (PROMPT) following shRNA-mediated knockdown (KD) of EXOSC10, as measured by qRT-PCR of total RNA. Dots represent biological replicates. G) Proportion of reads mapping to each intermediate isoform for intron groups used in splicing order analyses in WT K562 cells (Fig. 2). Biological duplicates for each shRNA treatment are shown side by side. H) Proportion of intermediate isoforms and intron groups that show a significant change (FDR < 0.1 and odds ratio > 1 or < −1) in abundance upon EXOSC10 KD compared to a scrambled control. I) Distribution of median poly(A) tail lengths as a function of splicing level in K562 replicate B. All reads are classified into groups of 3–4 introns based on the number of proximal post-transcriptionally excised introns that the read covers (splicing level). The median poly(A) tail length across reads is calculated for each number of excised introns in each intron group. Splicing levels were compared using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test (p-value < 0.001 for all comparisons). In G) and I), boxplots elements are shown as follows: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers.

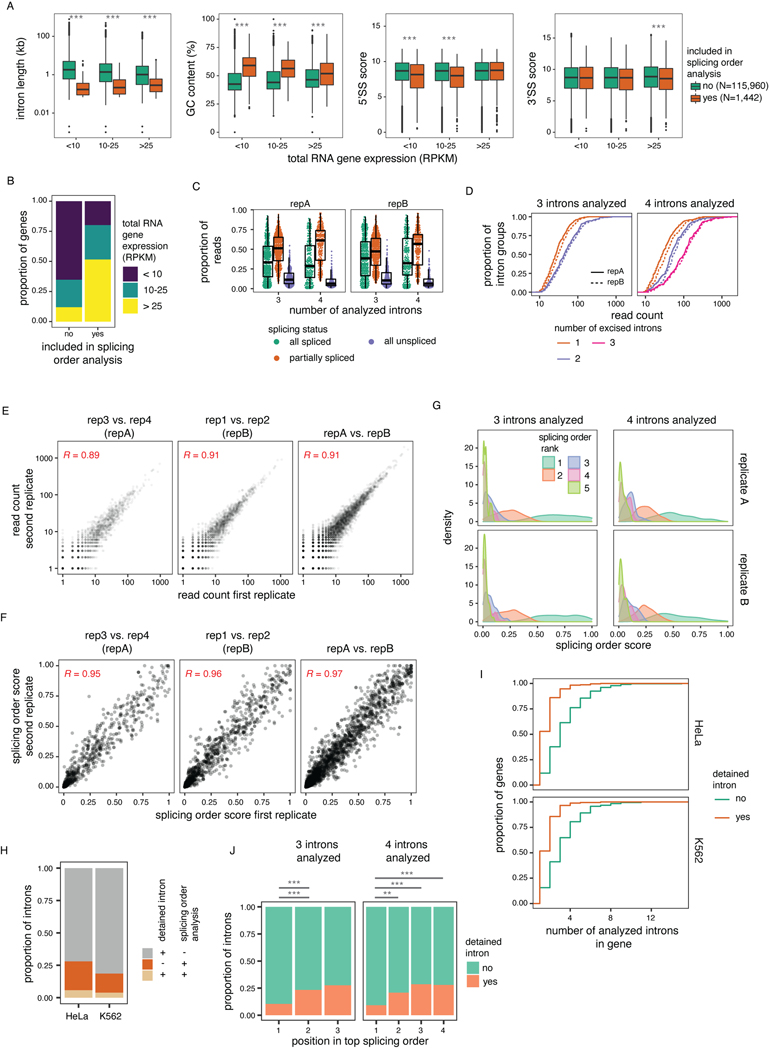

Extended Data Figure 2.

(related to Figure 2). A) Features of introns that were included or not in splicing order analyses in K562 cells. Groups were compared using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test (***: p-value < 0.001). B) Expression level in K562 cells for genes (RPKM > 1) used in splicing order analyses. C) Read splicing status for the intron groups used in splicing order analyses. Two K562 biological replicates are shown. Each dot represents one intron group. D) Cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the number of reads at each splicing level for the intron groups used in splicing order analyses. E) Correlation in number of intermediate isoform reads or F) splicing order scores between K562 biological replicates prior to and after merging into replicates A and B. Each dot represents one intermediate isoform (E) or one splicing order (F). Pearson’s correlation coefficients are shown on the plots [p-value < 0.0001, intermediate isoforms: 95% confidence interval 0.88–0.90 (reps 3 vs. 4), 0.90–0.91 (reps 1 vs. 2), 0.91–0.92 (reps A vs. B), splicing order scores: 0.95–0.96 (reps 3 vs. 4), 0.95–0.96 (reps 1 vs. 2), 0.96–0.97 (reps A vs. B)]. G) Scores for splicing orders with a rank lower than 5. H) Overlap between detained introns (DIs) from 31 and introns included in splicing order analyses, for introns present in genes expressed (RPKM or FPKM > 1) in K562 or HeLa cells and in at least one cell type from 31. I) CDF of number of introns that are DIs or not for genes in which at least one DI was identified in 31. J) Proportion of introns that were previously identified as DIs as a function of their position in the top ranked splicing order in K562 cells. Groups were compared using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test. *: p-value < 0.05, **: p-value < 0.01, ***: p-value < 0.001. For A) and C), boxplots elements are shown as follows: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range. In A), points represent outliers.

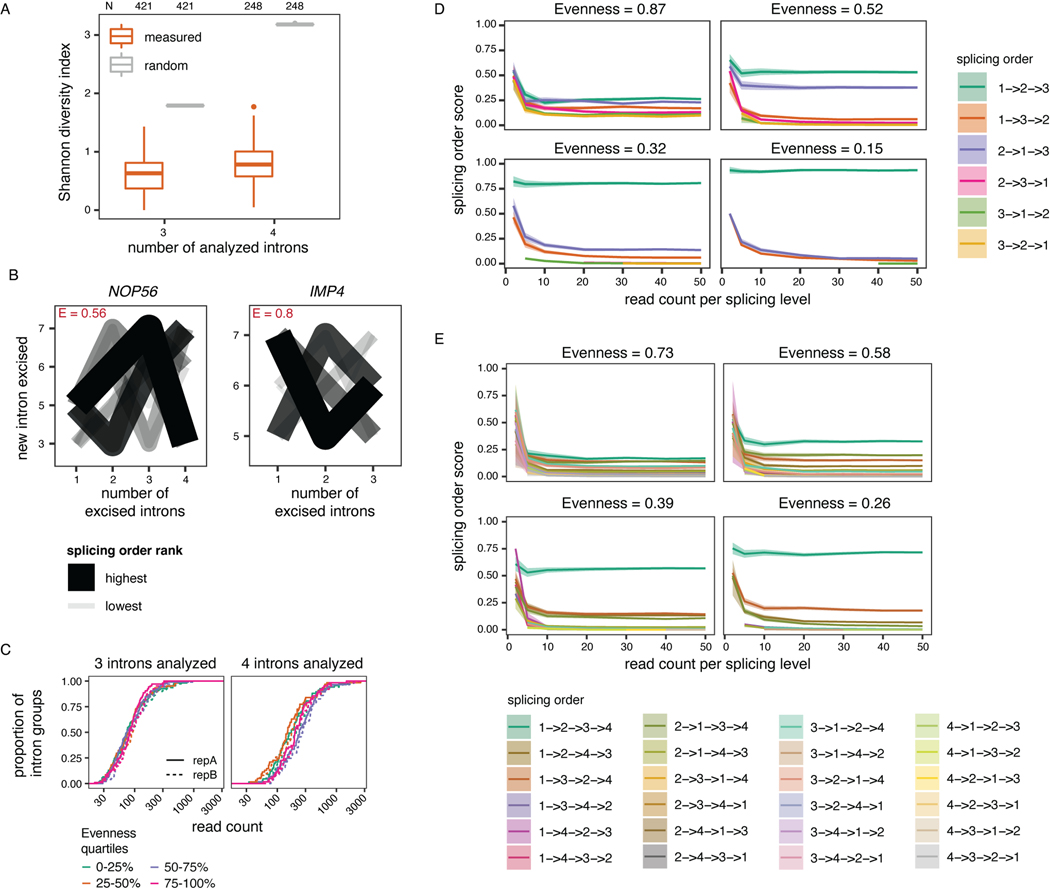

Extended Data Figure 3.

(related to Figure 2). A) Shannon diversity index of splicing order across all analyzed intron groups, separated by the number of introns in each group (3 or 4). Shannon diversity index is compared for measured (orange) or random (grey) splicing order. Boxplots elements are shown as follows: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points: outliers. B) Splicing order plots for the intron groups with the highest evenness for groups of 3 or 4 introns, respectively. The evenness (E) is shown in red font for each intron group. C) Cumulative distribution function plot of the number of reads at each splicing level for the intron groups used in splicing order analyses as a function of evenness. Evenness was binned into quartiles separately for groups of 3 or 4 introns. D) and E) Splicing order simulations with varying levels of read coverage and evenness values for 3 (D) or 4 (E) analyzed introns. Each possible splicing order is shown in a different color and the mean splicing order score for 100 simulations is displayed with 95% confidence interval.

Extended Data Figure 4.

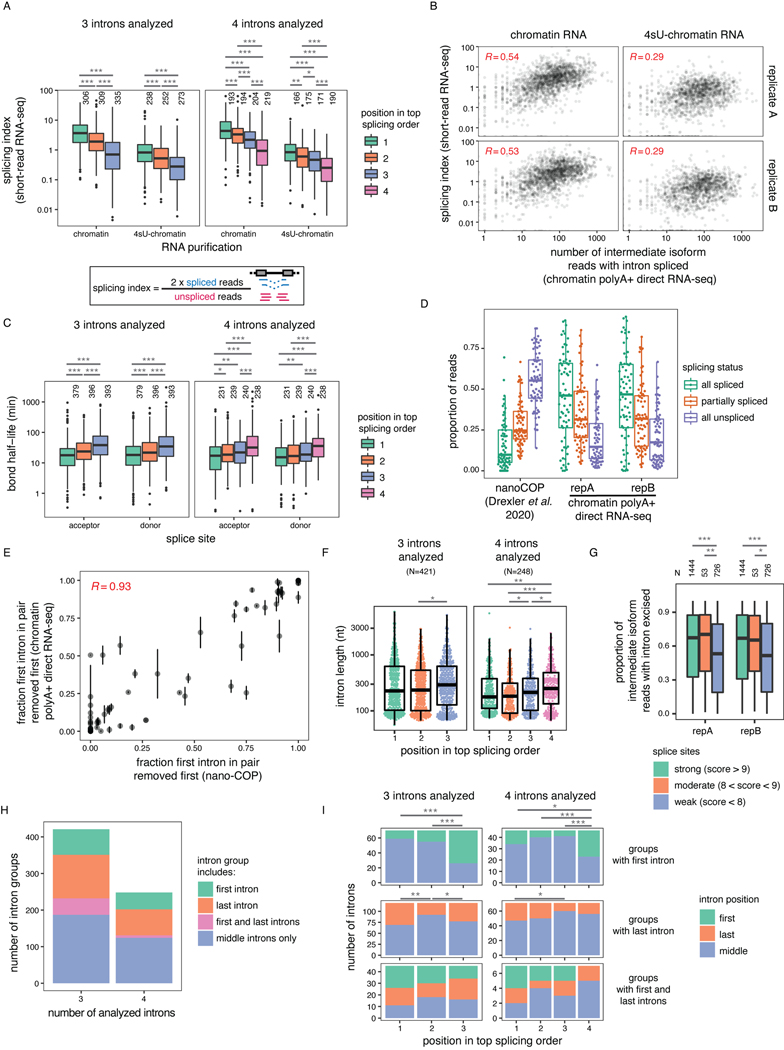

(related to Figure 2). A) Splicing index from short-read RNA-seq of rRNA-depleted nascent RNA, as a function of the position of introns in the top ranked splicing order from chromatin polyA+ dRNA-seq. B) Correlation between splicing index from A) and the number of intermediate isoform reads with a given intron excised from chromatin polyA+ dRNA-seq. Each dot represents one intron included in splicing order analyses in K562 cells. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is shown on the plot [p-value < 0.0001, 95% confidence interval 0.50–0.57 (repA chromatin), 0.50–0.56 (repB chromatin), 0.24–0.34 (repA 4sU-chromatin and repB 4sU-chromatin)]. C) Acceptor and donor bond half-lives25 as a function of the position of introns in the top ranked splicing order from chromatin polyA+ dRNA-seq. D) Splicing status of reads mapping to the intron pairs (N=69) compared between nano-COP14 and polyA+ dRNA-seq in E. E) Splicing order for pairs of consecutive introns in nano-COP vs. polyA+ dRNA-seq. Vertical bars show the range between the two biological replicates for chromatin polyA+ dRNA-seq. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is shown on the plot (p-value < 0.0001, 95% confidence interval 0.88–0.95). F) Intron length as a function of the position of introns in the top ranked splicing order per intron group. G) Proportion of intermediate isoform reads with a given intron excised for introns with strong, moderate or weak splice sites. H) Number of intron groups used in splicing order analyses that include a first or last intron in a transcript or both. I) Number of introns that are first or last in a transcript as a function of their position in the top ranked splicing order. For A), C), F) and G), introns or groups were compared using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. For I), groups were compared using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test. *: p-value < 0.05, **: p-value < 0.01, ***: p-value < 0.001. In A), C), D), F) and G, boxplots elements are shown as follows: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range. For A), C) and G), points represent outliers.

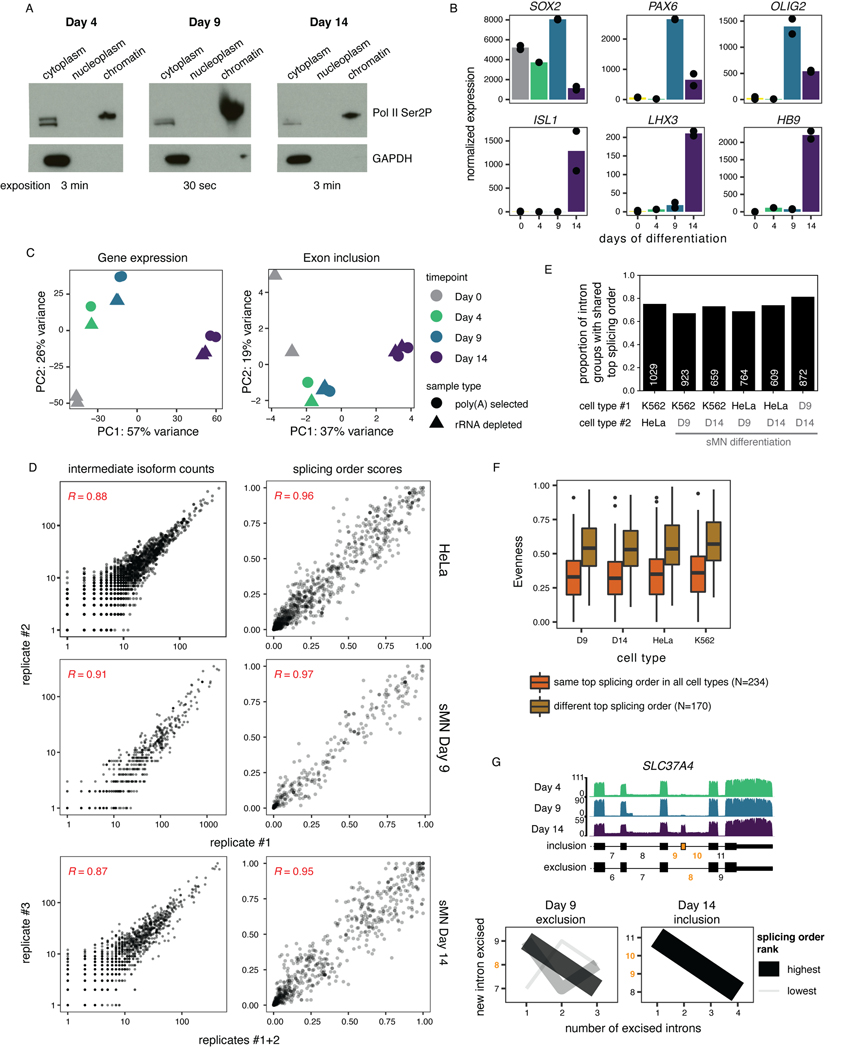

Extended Data Figure 5.

(related to Figures 3 and 4). A) Western blot showing the cytoplasm, nucleoplasm and chromatin fractions obtained from cellular fractionation at each sMN differentiation timepoint. The exposition time used for each blot is noted at the bottom. More cells were used at day 9, resulting in higher abundance of the markers. B) Expression of differentiation markers during sMN differentiation, as measured by short-read RNA-seq of chromatin-associated RNA. Dots represent biological replicates. C) Principal component analysis of gene expression or exon inclusion in short-read RNA-seq across all timepoints of sMN differentiation. D) Correlation in number of intermediate isoform reads or splicing order scores between biological replicates for the intron groups used in splicing order analyses in HeLa cells and differentiating sMN at Days 9 and 14. Each dot represents one intermediate isoform (left) or one splicing order (right). For Day 14, replicates 1 and 2 were merged to achieve similar coverage as replicate 3. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is shown on the plot [p-value < 0.0001, 95% confidence interval intermediate isoform counts: 0.87–0.89 (HeLa), 0.89–0.92 (sMN Day 9), 0.86–0.88 (sMN Day 14), splicing order scores: 0.95–0.96 (HeLa), 0.96–0.97 (sMN Day 9), 0.94–0.95 (sMN Day 14)]. E) Proportion of intron groups with the same top splicing order for each pairwise comparison of cell types indicated on the x-axis. The total number of intron groups per comparison is shown on each bar. F) Evenness of splicing order for intron groups analyzed across cell types, separated by whether they share the same top splicing order across cell types or not. Boxplots elements are shown as follows: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points: outliers. G) Top: dRNA-seq coverage tracks of an example alternative cassette exon (in yellow) with differential inclusion during sMN differentiation. AS introns are shown in yellow font. Bottom: Splicing order plot for SLC37A4, shown separately for inclusion and exclusion of the alternative exon and for each timepoint that had sufficient coverage of a specific isoform.

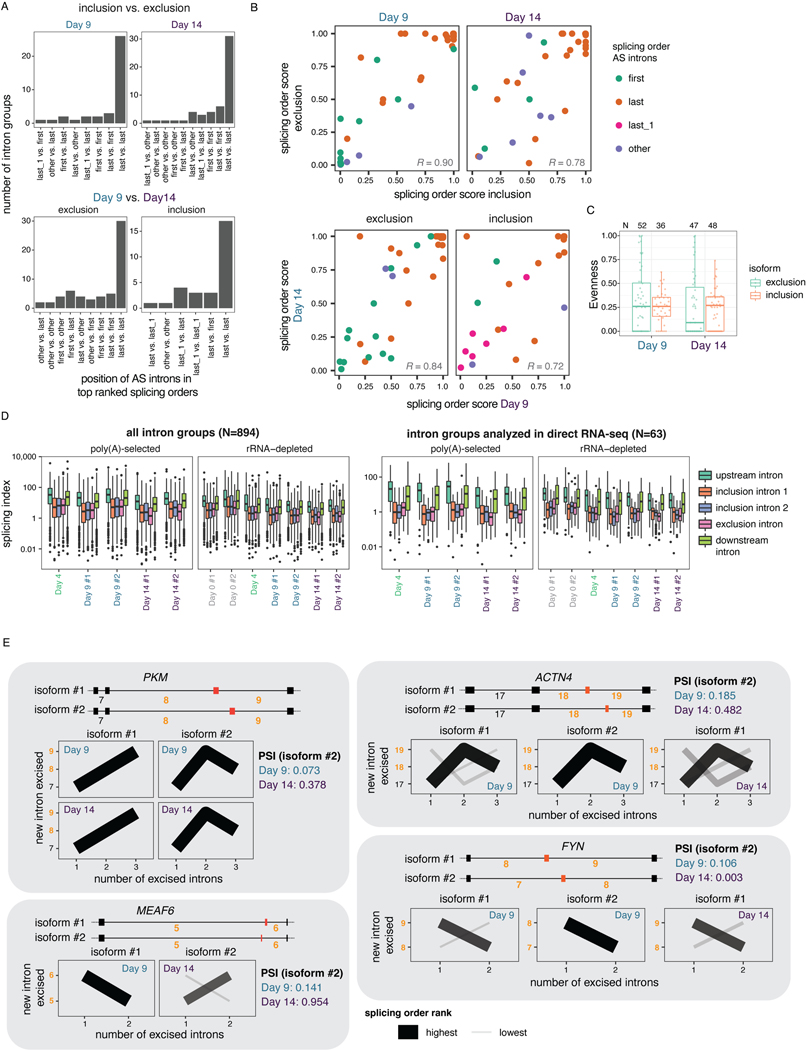

Extended Data Figure 6.

(related to Figure 4). A) Number of intron groups as a function of the order in which AS introns are removed in the top ranked splicing order per intron group. Each x-axis label compares the splicing order in inclusion vs. exclusion isoforms (top) or Day 9 vs. Day 14 (bottom). B) Correlation in splicing order scores for AS introns between exclusion and inclusion isoforms (top) or between Days 9 and 14 (bottom). Each dot represents one possible splicing order for one intron group. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is shown on the plot [p-value < 0.001, 95% confidence interval 0.82–0.95 (Day 9), 0.62–0.88 (Day 14), 0.72–0.91(exclusion), 0.48–0.87 (inclusion)]. C) Evenness for inclusion and exclusion isoforms. Isoforms were compared using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test (p-value > 0.05). D) Splicing index from short-read RNA-seq of chromatin-associated RNA for all intron groups that contain a differentially included exon between Days 9 and 14 (right) or for only those that had sufficient coverage to be analyzed by dRNA-seq (left). “Inclusion intron 1”, “inclusion intron 2” and “exclusion intron” refer to the three possible AS introns that flank or overlap an alternative exon. “Upstream” and “downstream” intron refer to the next proximal introns upstream or downstream of the AS introns. E) Splicing order for four mutually exclusive exons (MXE) AS events. Splicing order plots are shown for each isoform and time point that has sufficient coverage. The percent spliced in (PSI) for isoform #2 is shown for each timepoint. In C) and D), boxplots elements are shown as follows: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range. In C), points represent intron groups. In D), points represent outliers.

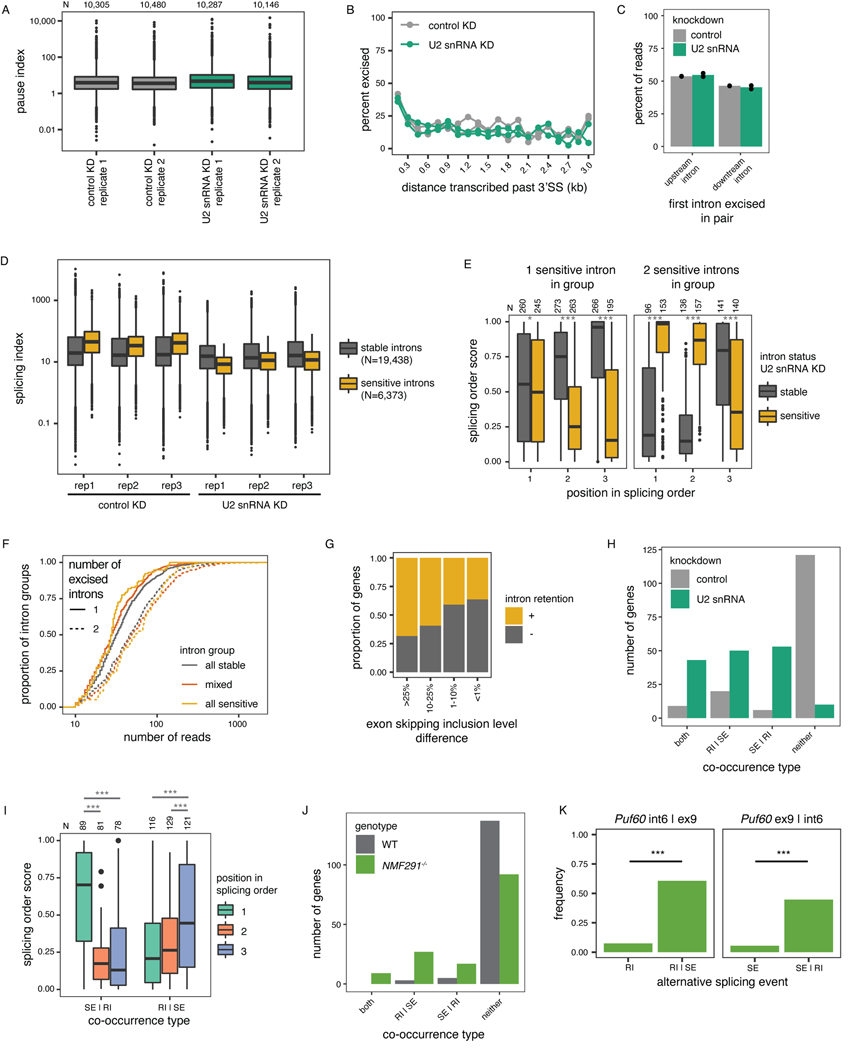

Extended Data Figure 7.

(related to Figure 5). A) NET-seq pause index upon control or U2 snRNA KD. B) Percent of excised introns as a function of the distance transcribed past the 3’ SS for nano-COP reads from control and U2 snRNA KD. Two biological replicates per condition are displayed. C) Splicing order in nano-COP data from control and U2 snRNA KD for pairs of consecutive introns. Dots represent biological replicates. D) Total RNA-seq splicing index for introns that are sensitive to U2 snRNA KD compared to those that are stable. Three biological replicates (“rep”) per condition are shown. E) Summed splicing order score for introns that are sensitive or stable upon U2 snRNA knockdown as a function of their position in splicing orders in WT HeLa cells. F) Number of reads mapping to each intron group as a function of the number of excised introns and their status upon U2 snRNA KD. G) Proportion of genes with and without intron retention in short-read RNA-seq from upon U2 snRNA KD, as a function of the exon skipping level difference between control and U2 snRNA KD in the same genes. H) Number of genes showing co-occurrence of skipped exons (SE) and retained introns (RI) in dRNA-seq, as depicted in Fig. 5F. I) Summed splicing order score for RIs upon U2 snRNA knockdown as a function of their position in splicing orders in WT HeLa cells. Intron groups are composed of one intron involved in RI and two introns involved in SE. J) Number of genes showing co-occurrence of SE(s) and RI(s) in cDNA-PCR nanopore sequencing data from WT and NMF291−/− (U2 snRNA mutant) mice53. K) Example of a SE and RI co-occurrence in Puf60 in NMF291−/− mice. ***: p-value < 0.001 in the one-sided binomial test assessing co-occurrence of SE and RI. In A), D), E) and I), boxplots elements are shown as follows: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. In E) and I), groups were compared using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test; *: p-value < 0.05; ***: p-value < 0.001.

Extended Data Figure 8.

(related to Figure 5). A) Working model to explain splicing order changes upon U2 snRNA KD. B) RT-PCR products from amplification of exons 2 to 5 and 9 to 12 of IFRD2, showing increased retention of introns 2 to 4 and 9 to 11 upon U2 snRNA KD compared to control. The identity of the spliced and unspliced products is shown on the right of the gel. Two biological replicates per knockdown condition are displayed. C) Scatter plots showing the correlation in frequency of intermediate isoform reads per splicing level for cDNA-PCR sequencing of IFRD2 exons 4–10 from chromatin-associated RNA with 12, 16 or 20 PCR cycles. Pearson’s R correlation coefficients are shown on each plot (p-value < 0.0001, 95% confidence interval: control KD, 12 cycles: 0.91–0.97; control KD, 16 cycles: 0.95–0.99; U2 snRNA KD, 12 cycles: 0.91–0.98; U2 snRNA KD, 16 cycles: 0.97–0.99). The data obtained from 20 cycles was used for subsequent analyses. D) Representation of reads mapping to introns 4 to 9 of IFRD2 upon cDNA-PCR sequencing of chromatin-associated RNA from control or U2 snRNA KD. Each line represents one read and each column represents one intron. For each number of excised introns, 100 reads were randomly subsampled from the total dataset. A black rectangle highlights the splicing order reversal upon U2 snRNA KD. E) Splicing order plots for IFRD2 in the absence (top) or presence (bottom) of SEs. On the y-axis, introns that are removed together to result in SE are shown separated by an underscore. The top 10 splicing orders per category (with or without SE) are shown. Experiments shown in C), D) and E) were performed on biological duplicates and data is displayed for one representative replicate per condition.

Extended Data Figure 9.

(related to Figure 6). A) RT-PCR following treatment with a positive control ASO resulting in the use of an alternative 5’SS in BCL2L1 (red asterisk). B) RT-PCR following treatment with ASOs targeting the 3’SS of introns 4, 5 and 9 of IFRD2. Asterisks indicate the alternative splicing events in which exons 5 to 8 are skipped, without (orange) or with (red) intron 9 retention. C) Proportion of reads with different alternative splicing events observed in cDNA-PCR nanopore sequencing of total RNA following treatment with ASOs targeting IFRD2. RI: retained intron, SE: skipped exon(s), int: intron, ex: exon. D) Deletion tiling of IFRD2 using CRISPR-Cas9 editing. The resulting deletions are shown as black horizontal lines delimited by vertical lines aligned to the sgRNA(s) used (blue triangles). Left: Percent of reads with the expected deletion in cDNA-PCR nanopore sequencing of chromatin-associated RNA. Deletions made with only one sgRNA and non-targeting controls were not assessed (N/A). Right: Percent of reads with exon skipping in each deletion. “Undetermined splicing pattern” refers to reads in which a splicing event does not map to annotated intron-exon junctions and results from detection of the deletion and/or from the use of a cryptic splice site as a result of the deletion. The reads shown on the left and right plots are not mutually exclusive, where reads containing the deletion (left) can also be classified as “undetermined splicing pattern” (right) if the deletion overlaps with exon(s). E) Top: Chromatograms from Sanger sequencing of pools of cells edited with a non-targeting sgRNA and one targeting the end of exon 5. The bottom bar plot shows the predicted type of indel introduced. The x-axis indicates the position relative to the expected cut site. F) RT-PCR of introns 2 to 4 of IFRD2 for the deletions shown in D) that are not displayed in Fig. 6F. G) Expected outcomes for intron 4 excision based on the intron and exon definition models of splice site recognition58,59. The observation of intron 4 retention (Fig. 6) is consistent with exon definition.