Abstract

Objective

The goal of the study was to examine the relations of general and diabetes-specific friend support and conflict to psychological and diabetes health among youth with type 1 diabetes. We examined gender as a moderator of these relations, and friend responsiveness and information-sharing as potential mediators.

Methods

Youth with type 1 diabetes (n = 167; M age 15.83 [SD = 0.78]; 50% female) were interviewed once in the Fall and once in the following Spring of the school year. Using multiple regression analysis, general friend support, general friend conflict, diabetes-specific support, and diabetes-specific conflict were investigated as simultaneous predictors of psychological and diabetes outcomes cross-sectionally and longitudinally over four months.

Results

Cross-sectionally friend conflict, including both general and diabetes-specific, was more predictive of outcomes than friend support. In cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses, gender was a significant moderator, such that several relations of general friend conflict to outcomes were significant for females but not nonfemales. Friend support revealed mixed relations to outcomes across cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Although we found links of friend relationship variables to mediators (perceived responsiveness; information sharing), we found little evidence of mediation.

Conclusions

These findings show stronger evidence that conflictual friend relationships than supportive friend relationships are linked to health. Findings suggest that problematic friend relationships may have a stronger impact on the health of females than nonfemales. These results underscore the need to better understand the conditions under which friend support is helpful versus harmful and the reasons underlying these links.

Keywords: diabetes, friend conflict, friend support, gender

Major developmental tasks of adolescents include the development of autonomy from parents and the establishment of connections with peers (Rubin et al., 2006). Over the course of adolescence, youth spend an increasing amount of time with peers (Barry et al., 2016; Lam et al., 2014; Steinberg & Morris, 2001) and begin to turn to peers rather than parents for support (Spitz et al., 2020). Adolescents are also sensitive to the influence of peers (Sayler et al., 2022; van Hoorn et al., 2016). The increased role of peer relationships in the lives of adolescents suggests that those relationships are likely to influence well-being. Indeed, a meta-synthesis showed small but significant cross-sectional and longitudinal links of friendship characteristics to depressive symptoms and loneliness among adolescents (Schwartz-Mette et al., 2020).

Peer relationships may play an especially critical role in well-being for youth with type 1 diabetes. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease that requires the exogenous administration of insulin and careful monitoring of diet and exercise to maintain healthy glucose levels over the course of the day. This self-care regimen is demanding and may disrupt normative social interactions. Research has shown that diabetes self-care behavior declines and average glucose levels (i.e., HbA1c) increase over the course of adolescence (Foster et al., 2019; King et al., 2014). Whether—and to what extent—peer relationships are involved in these changes remains unclear.

Because of the importance of friend and peer relationships during this developmental stage, friend conflict is likely to have important implications for diabetes management among adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Indeed, a literature review concluded that friend conflict was related to psychological difficulties—specifically depression, perceived stress, and risk behavior—among this group (Van Vleet & Helgeson, 2020). However, the review noted that few studies have examined links of friend conflict to self-care or HbA1c, and these findings are equivocal. Even less work has focused on conflictual interactions with friends that are directly related to diabetes. Such “diabetes-specific conflict” may be particularly troublesome for diabetes outcomes because it may pose direct barriers to daily self-care behaviors. Although qualitative studies indicate that adolescents perceive peers to be an obstacle to good self-care (e.g., Berlin et al., 2006; Cox et al., 2014; Jayawickreme et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2015), few quantitative studies have tested this possibility, and one study showed that diabetes interpersonal stress was not associated with glycemic stability (Berlin et al., 2012).

On the other hand, friend support shows mixed links to both psychological and diabetes outcomes among adolescents with diabetes. Whereas some research shows that friend support is related to good psychological health (less depression, lower perceived stress, reduced risk behavior), links to diabetes outcomes are less clear (Van Vleet & Helgeson, 2020). One study showed that friend support predicted reduced diabetes distress over one year but did not predict changes in adherence or HbA1c (Raymaekers et al., 2017). Only a handful of studies have focused on support that is specific to diabetes, some of which reveal no relations to health, a few reveal a relation to good health, and a couple reveal a relation to health difficulties (see Van Vleet & Helgeson, 2020, for a review). The drawback to diabetes-specific support is that it sets youth apart from peers at a time when fitting in is crucial. Youth with type 1 diabetes are concerned with fitting in with peers and perceive that their disease makes them feel different (Commissariat et al., 2016; Mattacola, 2020). Whereas general forms of support are likely to communicate feelings of acceptance and belonging (fitting in with one’s friends), diabetes-specific support may unintentionally single out adolescents with diabetes.

In sum, there is more evidence that conflict with friends is related to health difficulties than there is that support from friends is related to good health, but the entire body of research in this area is sparse. The existing research focuses more on general conflict and support rather than diabetes-specific conflict and support. Researchers have emphasized the importance in making this distinction (Raymaekers et al., 2017; Van Vleet & Helgeson, 2020). In addition, links to diabetes outcomes have not been closely investigated. Thus, the first study goal was to expand on previous research by examining links of both general and diabetes-specific forms of support and conflict to psychological and diabetes health.

We predicted that both general and diabetes-specific conflict would be related to psychological and diabetes health difficulties. We did not make any predictions as to whether general or diabetes-specific conflict would reveal stronger relations to outcomes. We predicted that both general support and diabetes-specific support would be linked to positive psychological and diabetes health, but expected general support would be more strongly linked to outcomes than diabetes-specific support.

Gender as a Moderator

The second study goal was to examine the extent to which gender moderated the links of friend relationships to health. Friends tend to play a larger role in the lives of female than male adolescents, and friendships between two females are characterized by more intimacy than friendships involving two males (Barry et al., 2009; Bauminger et al., 2008; Linden-Andersen et al., 2009; Swenson & Rose, 2009). A meta-analytic review of the literature on social support and well-being among children and adolescents showed that relations were stronger for females than males—but did not specifically distinguish among the sources of support when examining gender (Chu et al., 2010). Thus, we hypothesized that the relations of friend support and conflict to health may be stronger for females than males.

Explanations for Links of Friend Relationships to Health

Little attention has been paid to the explanations for links of friend support or friend conflict to health. Thus, the final study goal is to focus on two potential explanatory mechanisms: friend responsiveness to needs and information sharing.

How friends respond to diabetes may explain why friend support and/or friend conflict is related to health. When youth with type 1 diabetes were asked to predict how their friends and peers would react to hypothetical diabetes self-care scenarios, adolescents who reported that their friends and peers would react negatively anticipated that they would be less likely to take care of themselves, reported higher overall diabetes stress, and had glycemic instability (Hains et al., 2007). Anticipating friends’ responses is similar to the construct of perceived emotional responsiveness in the close relationships literature (Reis & Gable, 2015)—that is, the extent to which adolescents perceive that social network members will respond positively or negatively in the face of stress. Perceived responsiveness has been connected to numerous good relationship and health outcomes, including reduced mortality (Stanton et al., 2019). In the present study, having supportive friends may lead one to anticipate that friends will be responsive to one’s diabetes-related needs, thus enabling one to maintain regular diabetes care in the presence of friends. On the other hand, friend conflict may lead one to expect that friends will not respond appropriately to one’s diabetes needs, which may result in avoiding necessary self-care behaviors in the presence of friends. Thus, perceived friend responsiveness to needs could explain why support is beneficial to health and conflict is harmful to health.

A second explanation for the connection of friend support and conflict to health is the extent to which youth have shared information about diabetes with their friends and the extent to which friends know how to help during an emergency. Qualitative work has highlighted the importance of self-disclosure to self-care (Commissariat et al., 2016). In the context of supportive relationships, youth with diabetes may feel comfortable sharing their illness with their friends and describing potential emergency situations and how to handle them. By contrast, these efforts would seem less likely to occur in the context of conflictual relationships. Indeed, having friends who know how to help during an emergency is related to better self-care behavior (Malik & Koot, 2012; Pihlaskari et al., 2018). Thus, sharing diabetes information with friends and having friends who are knowledgeable about diabetes may be an important pathway connecting general or diabetes-specific support and conflict to health.

The Present Study

There were three study goals. First, we examined the links of both general and diabetes-specific friend support and conflict to health. Whereas much previous research has focused on either general constructs or diabetes-specific ones, we aimed to examine both. The majority of previous research also has focused on support rather than conflict. Again, here we examine both constructs. We examined psychological health (i.e., depressive symptoms, loneliness, disturbed eating behavior) and diabetes health (i.e., diabetes distress, diabetes efficacy, self-care behavior, HbA1c). We chose depressive symptoms because it is an important outcome in its own right and has been linked to suboptimal diabetes outcomes (Buchberger et al., 2016). We included loneliness because a recent synthesis of 16 meta-analyses on friendship in children and adolescence concluded that there were both concurrent and longitudinal links of friendship indices to both depressive symptoms and loneliness, with links slightly stronger for loneliness (Schwartz-Mette et al., 2020). We included disordered eating because youth with type 1 diabetes are at higher risk than those without diabetes for eating disorders (Young et al., 2013). We examined both cross-sectional and longitudinal relations over a 4-month period. We predicted that conflict would be more strongly linked to these outcomes than support. Among support indices, we predicted that general support would be more strongly linked to good outcomes than diabetes-specific support. Second, we examined gender as a moderator of these relations. We predicted that support and conflict would be more strongly related to outcomes for females than males. Finally, we expand on previous research by trying to understand the reasons for the relations of support and conflict to outcomes, focusing on perceived responsiveness and information sharing as potential mediators.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 167 youth aged 14–17 years with type 1 diabetes. Eligibility requirements included having type 1 diabetes for at least one year, having no other chronic illness that affected everyday life more than diabetes, and being a freshman/sophomore/junior in high school. Half identified as female (49%), 49% as male, and 2% as nonbinary. Race and ethnicity were examined using the National Institutes of Health categories. Nearly all participants were non-Hispanic (99%), and the majority were White race only (89%). Other demographic information is shown in Table I.

Table I.

Demographic Characteristics

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.83 | 0.78 | 14.12 | 17.64 | 167 |

| Diagnosis age | 8.97 | 3.71 | 1 | 15.5 | 167 |

| HbA1c | 8.43 | 1.47 | 4.9 | 14.0 | 166 |

| Gender | 48.5% female | 167 | |||

| 49.7% male | |||||

| 1.8% neither male nor female | |||||

| Racea | 92.8% White | 167 | |||

| 9.6% Black | |||||

| 1.2% Asian | |||||

| 0% American Indian/Alaska Native | |||||

| 0% Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | |||||

| Ethnicity | 98.8 % non-Hispanic; 1.2% Hispanic | 167 | |||

| Household structure | 67.1% live with mom & dad | 167 | |||

| 2 parent household | 80.8% 2-parent household | 167 | |||

| Grade | 22.8% 9th | 167 | |||

| 48.5% 10th | |||||

| 28.7% 11th | |||||

| Pump | 59.9% pump; 40.1% injections | 167 | |||

| CGM | 79% CGM; 21% meter | 167 | |||

Because participants could select more than one race, these numbers add up to more than 100%; note that 3.6% chose more than one race.

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh. The study was preregistered, and all data are available at https://osf.io/fh9r3/.

Participants were recruited from the pediatric diabetes clinic at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. A nurse recruiter approached potentially eligible participants when they came to the clinic or contacted them by phone. She briefly described the study and obtained permission to release contact information to the project director. Only 18 refused. The project director then called families, screened for eligibility, described the study, and obtained verbal consent from one parent and the child to participate. Of the 334 families referred to the study, the project director reached 253 families after multiple attempts (e.g., some did not answer phone, some had incorrect phone number). Of the 253 reached, 18 were ineligible, 22 declined, and 213 agreed to participate. Of the 213, 167 were scheduled for the initial interview; 46 were not scheduled for various reasons (i.e., unable to reach for scheduling; phone disconnected; changed mind; study ended before participant could be scheduled). Thus, our effective response rate was 71%. The demographic data shown in Table I are consistent with the demographics for the overall clinic population ages 12–17 years (i.e., average age at diagnosis 8 years, 53% female, 88% white, 97% nonHispanic, 55% on insulin pump, 80% on CGM).

Prior to COVID-19 (i.e., March 16, 2020), the initial session consisted of an in-person interview in participants’ homes (n = 59). After March 16, 2020 due to COVID-19, the initial session was conducted virtually (n = 108). The first session was conducted in the Fall (Time 1 [T1]) and began by obtaining informed consent from one parent and assent from the youth. For virtual sessions, online consent was obtained as well as a recording of verbal consent. The youth was interviewed separately from the parent. To maintain interest, encourage engagement, and provide opportunities for clarification, we asked questions aloud with the use of response cards. The exceptions were measures of depression, loneliness, and disturbed eating behavior, which were completed privately via an online questionnaire (for both in-person and virtual interviews) due to their sensitive nature. At the end of the interview, HbA1c was obtained. In the Spring (approximately 4 months later), participants were reinterviewed following the same procedure (Time 2 [T2]). Monetary compensation was provided for each session ($25).

In the Spring, we retained 92% (n = 154) of the sample. Comparisons of those who were retained to those who dropped out on the variables shown in Table I revealed three differences. Those who dropped out were more likely to be a race or ethnicity other than non-Hispanic white (X2(1) = 5.26, p = .02), were less likely to live with their mother and father (X2(1) = 5.22, p = .02), and were less likely to be using an insulin pump (X2(1) = 4.97, p < .03). Comparisons on baseline friend variables revealed no differences; comparisons on baseline outcomes revealed only one difference—those who dropped out scored lower on bulimic symptoms (t (165) = 2.17, p = .03).

Instruments: Predictors

Internal consistencies at T1 and T2 for all instruments are provided in Supplementary Table I.

General Support and Conflict

We used the Berndt & Keefe (1995) friendship questionnaire. Support was measured by taking the average of three 4-item scales: esteem support, intimacy, and prosocial support subscales. One item was removed from the prosocial scale (“how often do you and your friends borrow things from each other”) because it detracted from reliability. Conflict was measured by taking the average of the 4-item conflict and 4-item dominance scales. We have combined these subscales into total support and conflict scores in many studies (e.g., Helgeson et al., 2007, 2009). The support scales are too highly correlated to examine individually and would add to the number of statistical tests conducted (same for the two conflict subscales). In addition, Berndt & Keefe (1995) reported that a principal components analysis showed the positive friendship scales loaded on one factor and the negative friendship scales loaded on another factor, supporting combining the subscales into support and conflict indices. All items were rated on 5-point scales ranging from 1 = never to 5 = very often.

Diabetes-Specific Support and Conflict

We developed three face-valid items to measure diabetes-specific support and three face-valid items to measure diabetes-specific conflict using the same 1–5 response scale. For support, we asked participants the extent to which friends helped them with (a) insulin regimen and blood glucose checking, (b) sticking to meal plan, counting carbohydrates, anything to do with food, and (c) feeling good about diabetes. For conflict, we asked how often friends made it more difficult with these same three domains. These scales tapped both the instrumental and emotional aspects of diabetes.

Instruments: Outcomes

Depression-Loneliness

We used the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale to measure depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977) and 7 of the 8-item abbreviated UCLA loneliness scale (Hays & Dimatteo, 1987). We removed “I am unhappy being so withdrawn” because the item is double-barreled and confounds loneliness with sadness. Because the two scales were highly correlated at T1 (r = 0.80, p < .001) and T2 (r = 0.82, p < .001), we standardized and averaged them to form a depression-loneliness index.

Disturbed Eating Behavior

We used two subscales from the Eating Disorder Inventory (Garner, 1990): drive for thinness (excessive concern with dieting, preoccupation with weight) and bulimic symptoms (episodes of uncontrollable eating or bingeing), both of which have been used with youth with type 1 diabetes (Helgeson et al., 2007). Three items from the drive for thinness scale were excluded because they are biased by the presence of diabetes (Steel et al., 1989). Each item is rated on a 1–5 scale, ranging from never to very often.

Diabetes Distress

We used the Teen Version of the Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale (Weissberg-Benchell & Antisdel-Lomaglio, 2011). The scale taps sources of diabetes distress. Respondents indicate how much of a problem six different hassles have been for them in the past month on a scale ranging from 1 (not a problem) to 6 (serious problem).

Self-Efficacy

The 7-item self-efficacy subscale of the Multidimensional Diabetes questionnaire (Talbot et al., 1997) was administered. Ratings were made on a scale ranging from 0% (absolutely certain cannot do it) to 100% (100% certain can do it), reflecting confidence that they could enact various aspects of diabetes self-care (e.g., check blood glucose).

Self-Care

We administered the 14-item Self-Care Inventory (SCI; La Greca et al., 1988) which asks respondents to indicate how well they have followed their physicians’ recommendations for glucose checking, insulin administration, diet, exercise, and other diabetes-related behaviors over the past 2 weeks. Each item is rated on a 1 (never do it) to 5 (always do this as recommended) scale. This scale has been associated with HbA1c among adolescents in several studies (Lewin et al., 2009). We updated this scale in our previous work (Helgeson et al., 2008) by asking how frequently (1 = never, 5 = very often) participants rotated injection or pump sites, skipped injections or boluses, skipped meals, ate foods that should be avoided, falsified blood test results because the numbers were too high, falsified blood test results because they did not really check (the latter two taken from Weissberg-Benchell et al., 1995). We also omitted “coming in for appointments” because that self-care behavior is governed more by parents than adolescents, and most youth will not have had an appointment in the past 2 weeks.

HbA1c

For in-person interviews, we used the DCA Vantage to obtain a measure of HbA1c. For virtual interviews, we mailed the CoreMedica HemaSpot-SE Self-Collection Test kit prior to the interview and provided instructions about its use at the end of the interview. Participants mailed the kits to the lab for processing, and we received the results. On occasions when we did not receive the results, youth did not submit the kit, or we could not accurately identify to whom the results belonged, we used the HbA1c from the closet clinic appointment if it occurred within 3 months (T1: n = 12; T2: n = 20). This resulted in 1 missing at T1 and 6 missing at T2. Higher HbA1c indicates on average higher values of blood glucose, which is reflective of diabetes instability.

Instruments: Mediators

Perceived Emotional Responsiveness

We asked participants to think about how their friends typically respond when they are having a problem with diabetes. Participants rated how often they felt the following ways on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot): understood, accepted, comforted, self-confident, loved/cared for, judged/evaluated, put down, controlled, bossed around. These items were developed by Fekete et al. (2007) in a study of women with lupus based on the work of Laurenceau et al. (2005) to measure the perception of friends’ or partners’ responsiveness. This scale also has been used in the context of diabetes (Zajdel et al., 2018). When we examined the correlation matrix of the 9 items, there were two distinct clusters of items, such that the positive items were highly intercorrelated as were the negative items. A principal components analysis confirmed the presence of two distinct factors. Thus, we created a 5-item positive responsiveness factor and a 3-item negative responsiveness factor (we removed “controlled” because it detracted from the reliability).

Information Sharing

Participants were asked how much they have told their friends about (a) blood glucose checking, (b) what to do if blood sugar is low, and (c) what to do if blood sugar is high, using 3-point scales (1 = nothing, 2 = a little bit, 3 = a lot). Participants also indicated how much they agreed with the following three statements: (a) my friends know what I should do if my blood sugar is low, (b) my friends know what to do when my blood sugar is high, and (c) my friends understand blood glucose checking. Because the two scales were strongly correlated (r = 0.60, p < .001), we felt that we could not distinguish them and took the average of the two standardized scales.

Overview of the Analyses

We conducted an a priori power analysis by simulation based on a projection of a final sample of n = 144 (which we exceeded with n = 154) with two-tailed p < .05 for the goal of linking friend support and conflict to psychological and diabetes outcomes. We had 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.24 which is consistent with (if not lower than) effect sizes presented in our previous work.

First, we examined the correlations among the friend relationship variables to ensure that they were not so high that we could not examine them in a simultaneous regression. Second, we used independent t-tests to examine gender differences in friendship variables as well as potential mediators and outcomes because gender was a focal point of the study. Because less than 2% of the sample identified as nonbinary and most of our gender hypotheses revolved around being female, we divided the sample into female versus nonfemale (male and nonbinary) for gender analyses. Third, we examined potential covariates by examining the extent to which the demographic variables in Table I were related to the dependent variables. Because household structure, gender, race, and use of continuous glucose monitors (CGM) were related to multiple outcomes, we controlled for these four variables in all analyses. We examined race as a dichotomous variable because the vast majority of participants were non-Hispanic White; remaining participants were largely non-Hispanic Black (see Table I). Whether interviews were conducted pre- or post-COVID was related to general support and depression-loneliness at T1 and to depression-loneliness at T2. (Participants interviewed post-COVID reported lower T1 general conflict but higher T1 and T2 depression-loneliness than participants interviewed pre-COVID.) Nonetheless, controlling for this variable did not alter the findings presented in the results.

We examined cross-sectional links of friend variables to outcomes at T1 in two steps with multiple regression analysis. On the first step, we entered general friend support, diabetes-specific friend support, general friend conflict, and diabetes-specific friend conflict into a simultaneous regression analysis with the above statistical controls. On the second step, we examined the extent to which gender moderated the relations of the four friendship variables to outcomes by including the four interaction terms into the analyses. The standardized betas and confidence intervals for these findings are shown in Tables II–IV. When interactions were significant, we interpreted them with simple slopes analysis which we provide in the text and figure captions. To examine longitudinal relations, we used the same procedures to examine T2 outcomes but controlled for the respective T1 outcome.

Table II.

Regressions: Friendship Variables Predicting Psychological Outcomes (Standardized Betas and Confidence Intervals)

| Depression-Loneliness | Bulimic Symptoms | Drive for thinness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step1 | Step 2 | |

| Female | .29 *** [.26; .84] | .11 [−2.40; 2.81] | .26 *** [.14; .54] | −.75 [−2.86; .85] | .50*** [.81; 1.42] | −.25 [−3.39; 2.27] |

| HH structure | −.08 [−.46; .15] | −.09 [−.48; .12] | −.07 [−.33; .13] | −.06 [−.29; .13] | −.12+ [−.61; .03] | −.12 [−.61; .03] |

| Pump | −.02 [−.33; .24] | .01 [−.27; .29] | .03 [−.16; .24] | .04 [−.14; .26] | −.22 *** [−.79; −.20] | −.21 ** [−.77; −.17] |

| Race | .00 [−.43; .44] | −.01 [−.44; .40] | .09 [−.11; .50] | .08 [−.14; .47] | .18 ** [.19; 1.10] | .18** [.18; 1.10] |

| General support | −.26 ** [−.71; −.13] | −.01 [−.44; .39] | −.13 [−.35; .06] | −.08 [−.38; .21] | −.07 [−.44; .17] | −.05 [−.55; .35] |

| DM support | −.04 [−.21; .12] | −.30* [−.57; −.03] | .06 [−.08; .16] | −.04 [−.22; .16] | −.05 [−.24; .11] | −.11 [−.42; .16] |

| General conflict | .20 ** [.10; .61] | −.01 [−.36; .32] | .20** [.07; .43] | .01 [−.23; .26] | .17 ** [.09; .62] | .09 [−.20; .54] |

| DM conflict | .14+ [−.01; .63] | .10 [−.27; .71] | .28 *** [.21; .66] | .27* [.07; .76] | .19** [.15; .83] | .11 [−.24; .82] |

| General support × F | −1.18+ [−1.12; .04] | .09 [−.39; .44] | .11 [−.57; .69] | |||

| DM support × F | .63* [.04; .72] | .21 [−.15; .33] | .15 [−.26; .47] | |||

| General conflict × F | .77 ** [.18; 1.19] | .79 ** [.15; .86] | .35 [−.17; .92] | |||

| DM conflict × F | .06 [−.56; .70] | −.01 [−.45; .44] | .22 [−.37; 1.00] | |||

| F statistic | 5.28 | 4.91 | 5.82*** | 4.65*** | 11.86 | 8.09 |

| R 2 | .21 | .28 | .23 | .27 | .38 | .39 |

Note:

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001; bolded coefficients are statistically significant at the alpha = .05/3 or .017 level; F = female; Female is scored as 1 = female, 0 = nonfemale; HH = household; Pump is scored as 1 = using insulin pump, 0 = not using insulin pump; Race is scored as 1 = Non-Hispanic White, 0 = All other races/ethnicities; DM = diabetes.

To the extent that friend variables predicted outcomes longitudinally, we examined whether positive and negative perceived responsiveness and information-sharing at T1 explained the link between the T1 friend variables and the T2 outcomes. If gender moderated the longitudinal links, moderated mediation was conducted with gender (female vs. nonfemale) moderating the effect of the independent variable on the mediator (path A) and the independent variable on the dependent variable (path C). Separate mediation models were conducted for each mediator; thus, three models were fit for each longitudinal finding. Demographic covariates were included in each model. When examining mediation for one of the three specific friend predictors, we omitted the other three friend predictors in the mediation models due to concerns about interpretability. Full information maximum likelihood was used to compute standard errors. Analyses were conducted in R using the lavaan package (v0.6-12; Rosseel, 2012).

Because we conducted multiple statistical tests, we applied the Bonferroni correction to our regression analyses by adjusting the alpha by the number of statistical tests performed within each set of outcomes. Thus, alpha was set to 0.017 for the three psychological outcomes (Table II), to 0.0125 for the four diabetes outcomes (Table III), and to 0.017 for the three mediators (Table IV).

Table III.

Regressions: Friendship Variables Predicting Diabetes Outcomes (Standardized Betas, Confidence Intervals)

| Diabetes Distress | Self-efficacy | Self-care | HbA1c | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | |

| Female | .34 *** [.47; 1.13] | −.43 [−3.96; 2.00] | −.23 ** [−11.87; −2.22] | .86 [−16.88; 69.90] | −.32 *** [−.46; −.18] | .90 [−.37; 2.14] | .08 [−.24; .69] | −1.92 **[−9.76; −1.50] |

| HH structure | −.20 ** [−.84; −.16] | −.20 **[−.83; −.16] | .06 [−2.99; 6.95] | .06 [−3.06; 6.79] | .20 ** [.06; .35] | .19 ** [.06; .34] | −.15+ [−.93; .02] | −.13+ [−.87; .07] |

| Pump | −.17* [−.71; −.08] | −.14* [−.66; −.03] | .04 [−3.30; 5.99] | .02 [−3.98; 5.27] | .14* [.01; .28] | .12+ [−.01; .26] | −.26 *** [−1.23; −.34] | −.26 *** [−1.22; −.33] |

| Race | .14* [.02; 1.00] | .13+ [−.00; .96] | −.16* [−14.73; −.47] | −.15* [−14.14; −.03] | −.15* [−.43; −.02] | −.14* [−.41; −.00] | .03 [−.56; .80] | .03 [−.54; .81] |

| Gen support | −.15+ [−.62; .03] | −.05 [−.58; .36] | .13 [−1.35; 8.08] | .06 [−5.41; 8.37] | .07 [−.08; .20] | .03 [−.18; .22] | −.21* [−.98; −.09] | −.39 ** [−1.65; −.34] |

| DM support | .01 [−.18; .20] | −.24+ [−.59; .02] | .05 [−1.92; 3.60] | .27+ [−.12; 8.82] | .11 [−.03; .13] | .30* [.02; .28] | .25 ** [.11; .64] | .38 ** [.15; 1.00] |

| Gen conflict | .17 * [.09; .66] | .03 [−.32; .46] | −.15* [−8.48; −.21] | .02 [−5.20; 6.15] | −.24 *** [−.33; −.09] | −.06 [−.22; .11] | .08 [−.17; .62] | .01 [−.51; .57] |

| DM conflict | .32 *** [.52; 1.24] | .34 *** [.38; 1.49] | −.29 *** [−15.57; −5.06] | −.29* [−18.46; −2.18] | −.29 *** [−.49; −.18] | −.30 ** [−.57; −.10] | .20** [.18; 1.18] | .00 [−.76; .78] |

| Gen support × F | −.22 [−.78; .53] | .01 [−9.56; 9.76] | −.17 [−.32; .24] | 1.44* [.11; 1.94] | ||||

| DM support × F | .60* [.07; .84] | −.54+ [−11.01; .29] | −.48+ [−.31; .01] | −.31 [−.83; .25] | ||||

| Gen conflict × F | .58* [.07; 1.21] | −.71* [−18.75; −1.99] | −.74 ** [−.59; −.10] | .39 [−.25; 1.34] | ||||

| DM conflict × F | −.06 [−.81; .62] | .01 [−10.26; 10.69] | .03 [−.29; .32] | .60* [.15; 2.14] | ||||

| F statistic | 10.58 | 8.17 | 5.07 | 4.27 | 9.48 | 7.55 | 4.92 | 4.31 |

| R 2 | .35 | .39 | .20 | .25 | .32 | .37 | .20 | .25 |

Note:

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001; bolded coefficients are statistically significant at the alpha = .05/4 or .0125 level; F = female; Female is scored as 1 = female, 0 = nonfemale; HH = household; Pump is scored as 1 = using insulin pump, 0 = not using insulin pump; Race is scored as 1 = Non-Hispanic White, 0 = All other races/ethnicities; Gen = general; DM = diabetes.

Table IV.

Friendship Variables Predicting Proposed Mediators (Standardized Betas and Confidence Intervals)

| Information sharing | PER positive | PER negative | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | |

| Female | .06 [−.10; .26] | .03 [−1.61; 1.69] | −.06 [−.19; .07] | −.08 [−1.25; 1.09] | −.06 [−.18; .08] | .08 [−1.12; 1.25] |

| HH structure | .07 [−.08; .30] | .06 [−.09; .28] | .08 [−.05; .21] | .08 [−.05; .22] | −.15+ [−.27; .00] | −.15+ [−.27; .00] |

| Pump | .07 [−.08; .28] | .07 [−.07; .28] | .05 [−.07; .18] | .05 [−.07; .18] | −.05 [−.17; .09] | −.05 [−.17; .08] |

| Race | −.03 [−.34; .21] | −.03 [−.33; .21] | −.04 [−.25; .13] | −.03 [−.24; .14] | −.03 [−.23; .16] | −.04 [−.25; .14] |

| General support | .14+ [−.01; .35] | .24* [.04; .56] | .30 *** [.14; .39] | .22* [.01; .38] | −.06 [−.17; .09] | .02 [−.17; .20] |

| DM support | .59 *** [.33; .54] | .63 *** [.30; .64] | .41 *** [.15; .29] | .44 *** [.11; .35] | .11 [−.03; .12] | .14 [−.06; .18] |

| General conflict | .03 [−.12; .20] | −.08 [−.33; .11] | −.12* [−.22; −.00] | −.01 [−.16; .15] | .32 *** [.13; .35] | .18+ [−.02; .29] |

| DM conflict | −.00 [−.20; .20] | −.13 [−.53; .09] | −.24 *** [−.42; −.14] | −.25 ** [−.52; −.08] | .23 ** [.07; .36] | .28* [.05; .49] |

| General support × F | −.54 [−.56; .18] | .39 [−.16; .36] | −.36 [−.34; .19] | |||

| DM support × F | −.13 [−.27; .16] | −.03 [−.16; .14] | −.12 [−.19; .12] | |||

| General conflict × F | .36 [−.07; .57] | −.42+ [−.43; .02] | .52+ [−.03; .44] | |||

| DM conflict × F | .33 [−.09; .71] | .10 [−.22; .35] | −.24 [−.42; .16] | |||

| F statistic | 17.62 | 12.89 | 18.82 | 13.02 | 4.46 | 3.48 |

| R 2 | .47 | .50 | .49 | .50 | .19 | .21 |

Note:

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001; bolded coefficients are statistically significant at the alpha = .05/3 or .017 level; F = female; Female is scored as 1 = female, 0 = nonfemale; HH = household; Pump is scored as 1 = using insulin pump, 0 = not using insulin pump; Race is scored as 1 = Non-Hispanic White, 0 = All other races/ethnicities; DM = diabetes; PER = perceived emotional responsiveness.

Results

Correlations among Friendship Variables

As shown in Supplementary Table II, half of the correlations were not significant, the rest were small (p < .05) with one exception: friend general support and friend diabetes-specific support were correlated 0.55 at T1 and 0.52 at T2 (both p’s < .001).

Gender Relations to Study Variables

As shown in Supplementary Table I and top of Table II, females reported more general support and diabetes-specific support than nonfemales. There were no significant gender differences in general conflict, but females reported more diabetes-specific conflict than nonfemales.

Females reported greater depression-loneliness, more bulimic symptoms, more drive for thinness, and more diabetes distress than nonfemales. Females reported lower self-efficacy, lower self-care, and had higher HbA1c than nonfemales.

Females reported greater information sharing than nonfemales, but there were no gender differences in positive or negative responsiveness.

Cross-Sectional Links of Friend Variables to Health

Psychological Health

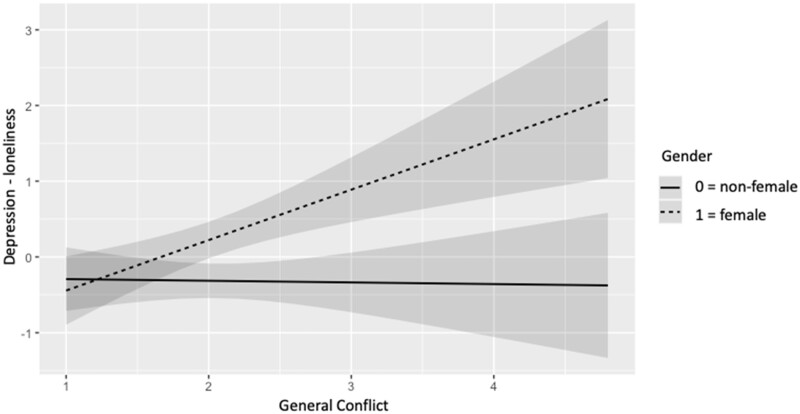

As shown in Table II, general support was related to lower depression-loneliness, whereas general conflict was related to higher depression-loneliness. There was a significant gender by general conflict interaction, such that general conflict was related to more depression-loneliness for females (p < .001) but not for nonfemales (p = .90; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

General friend conflict is related to greater T1 depression-loneliness for females (B = .67; SE = .19, p < .001) but not nonfemales (B = −.02, SE = .17, p = .90).

Both general and diabetes-specific conflicts were related to greater bulimic symptoms. Again, there was a similar gender by general conflict interaction (see Figure 2). General conflict was related to more bulimic symptoms for females (p < .001) but not nonfemales (p = .83). Both general and diabetes-specific conflicts also were related to greater drive for thinness, but there were no interactions with gender.

Figure 2.

General friend conflict is related to greater T1 bulimic symptoms for females (B = .61, SE = .15, p < .001) but not nonfemales (B = .03, SE = .13, p = .83).

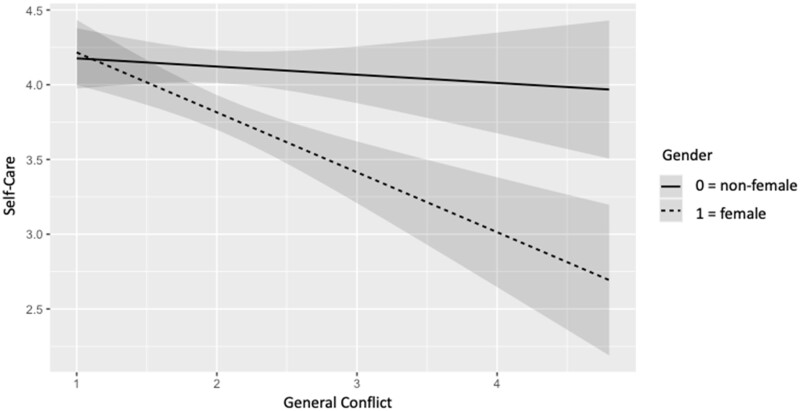

Diabetes Health

After accounting for multiple comparisons, general conflict was related to greater diabetes distress and lower self-care behavior (see Table III). Diabetes-specific conflict was related to all four diabetes outcomes, in the direction of more conflict being related to worse health. Gender interacted with general conflict to predict self-care behavior, such that general conflict was related to worse self-care for females (p < .001) but not for nonfemales (p = .51; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

General conflict is related to worse self-care for females (B = −.40, SE = .09, p < .001) but not nonfemales (B = −.05, SE = .08, p = .51).

More diabetes-specific support was related to higher (worse) HbA1c. When gender was added to the model, general support was related to lower HbA1c, and two interactions appeared that were not significant after the Bonferroni correction—one of which involved general support (p = .03). Because of the importance of this outcome, we examined the simple slopes for these two interactions, understanding that we needed to interpret them with caution. General friend support was related to lower (better) HbA1c for nonfemales (p = .003) but was unrelated for females (p = .92). Diabetes-specific conflict was related to higher HbA1c for females (p < .001) but not for nonfemales (p = .98).

Cross-Sectional Links of Friend Variables to Mediators

As shown in Table IV, general support was related to higher positive perceived responsiveness, and diabetes-specific friend support was related to greater information sharing and higher positive perceived responsiveness. General conflict was related to higher negative perceived responsiveness, and diabetes-specific conflict was related to lower positive perceived responsiveness and higher negative perceived responsiveness. There were no significant interactions with gender.

Longitudinal Links of Friend Variables to Outcomes

The full results for the longitudinal analyses are shown in Supplemental Tables III–V.

Psychological Health

None of the friend variables predicted changes in the three psychological health outcomes. For bulimic symptoms, there was a general support by gender interaction, but it was not significant with the Bonferonni correction.

Diabetes Health

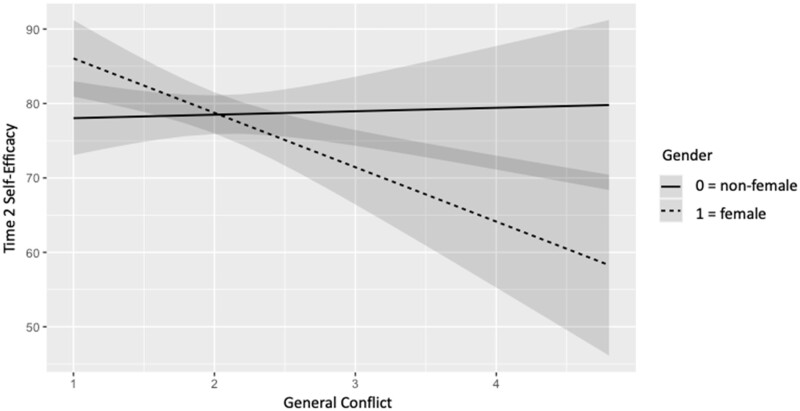

Friend relationship variables did not predict changes in diabetes distress. General friend conflict interacted with gender to predict changes in self-efficacy (B = −0.50, p = .011). Consistent with the other interactions in this paper, general conflict was related to a decrease in self-efficacy for females (p = .001) but not for nonfemales (p = .82; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

General conflict predicted a decline in self-efficacy for females (B = −7.31, SE = 2.17, p = .001) but not nonfemales (B = .46, SE = 2.06, p = .82).

None of the friendship variables predicted changes in self-care behavior. General friend support predicted a decline (improvement) in HbA1c (B = −0.25, p < .001), but diabetes-specific friend support predicted an increase (deterioration) in HbA1c (B = 0.23, p = .003). The diabetes-specific support effect was qualified by gender which again did not reach statistical significance after Bonferroni correction (B = 0.49, p = .044). However, simple slopes revealed that diabetes-specific support was related to an increase in HbA1c for females (p < .001) but was unrelated to HbA1c for nonfemales (p = .74).

Longitudinal Links of Friend Variables to Mediators

There were no friend relationship predictors of changes in information sharing.

General friend support predicted an increase in friend positive responsiveness (B = 0.28, p < .001) and a decline in friend negative responsiveness (B = −0.24, p = .005). General friend conflict predicted an increase in friend negative responsiveness (B = 0.30, p < .001).

There were no significant interactions with gender.

Mediation

It is important to note that the four mediators were largely uncorrelated. The full mediation results are shown in Supplemental Tables VIa–c.

The gender by friend conflict interaction effect on self-efficacy was not mediated by information sharing or positive or negative responsiveness.

The link of general friend support to lower HbA1c was not mediated by positive or negative responsiveness. However, information sharing emerged as a significant mediator. Interestingly, this indirect effect was in the opposite direction as the total effect and the direct effect. That is, T1 friend support was related to greater T1 information sharing, and T1 information sharing predicted higher HbA1c at T2. In contrast, the portion of friend support that did not operate through information sharing (i.e., the direct effect) predicted lower HbA1c at T2.

The link of diabetes specific support to changes in HbA1c was not mediated by information sharing, positive responsiveness, or negative responsiveness.

Discussion

Our first study goal was to examine the links of both general and diabetes-specific support and conflict to psychological and diabetes health. We predicted that conflict would be more consistently related to worse health outcomes than support would be related to good health outcomes. In general, findings were consistent with this prediction, which is consistent with previous research in the area of friendship and diabetes (Helgeson et al., 2007, 2009). Both general friend conflict and diabetes-specific friend conflict were cross-sectionally related to all three psychological health outcomes. Of the four diabetes outcomes, general friend conflict was related to two of them (diabetes distress and self-care), and diabetes-specific conflict was related to all four outcomes. Thus, there is some evidence that diabetes-specific conflict is more strongly linked to diabetes outcomes than general conflict. It is important to note that these findings emerged when both forms of conflict were in the same regression analysis, suggesting that these are unique effects. These findings are important as little previous research has focused on friend conflict, and the research that does exist neglects diabetes outcomes and involves general rather than diabetes-specific conflict. Given the lack of mediation (a point we return to later), it will be important for future research to identify the unique mechanisms by which general conflict is connected to problematic health outcomes compared to diabetes-specific conflict. In fact, it is possible that a generally conflictual relationship with a friend gives rise to specific instances of problems in the face of diabetes (i.e., diabetes-specific conflict) which then leads to greater psychological and diabetes difficulties.

Within the domain of support, general support was linked to lower depression-loneliness and an improvement in HbA1c over the four months. By contrast, diabetes-specific support was cross-sectionally linked to a higher HbA1c and to an increase in HbA1c over the four months. Thus, youth with diabetes may benefit more from having friends with whom they can connect, confide in, and rely on in general rather than from friends who support them specifically with diabetes, an idea put forth recently in a topical review (Helgeson et al., 2023). Adolescents with diabetes are concerned with fitting in with peers and worried that diabetes—and even helpful efforts from friends in regard to diabetes—sets them apart from their friends. Because the data showed that diabetes-friend support is related to a change in HbA1c over time (i.e., controlling for baseline HbA1c), it cannot be simply that youth who have a high HbA1c end up needing more diabetes specific support from friends.

Our second study goal was to examine whether the findings for friend relationship variables were moderated by gender. We found some evidence that general conflict was detrimental in terms of both general and diabetes health for females but not nonfemales. There was only one longitudinal relation involving general conflict, and it was moderated by gender in the same direction. That is, general conflict was related to a decline in self-efficacy over time for females only. To the extent that females are socialized to construe themselves more in terms of their relationships than males (Cross & Madson, 1997), it is not surprising that relationship qualities have a stronger connection to health for females. It is also the case that gender-role socialization is heightened during adolescence (i.e., gender intensification; Hill & Lynch, 1983), which may make females especially vulnerable to relationship influences at this time. On the other hand, it may be that general conflict is more characteristic of male friendship, and thus less bothersome to males than females (Bank & Hansford, 2000). In support of this possibility, we examined the correlation between general friend support and general friend conflict; the two were uncorrelated for nonfemales (r = −0.03, p = .81; [r = −0.01 for males specifically]) but strongly inversely correlated for females (r = −0.43, p < .001). Interestingly, these gender interactions were unique to general conflict, meaning the relations of diabetes conflict to relationship and health difficulties were not affected by gender.

However, there was no evidence that females benefitted more than nonfemales from the supportive aspects of friendship. To the contrary—there were a couple of suggestive findings that females benefitted less from support than nonfemales or that females’ health was even harmed by support. First, general support was related to a better HbA1c for nonfemales but not for females. Second, diabetes-specific support was linked with a deterioration in HbA1c over time for females but not for nonfemales. It is not the case that HbA1c deteriorated on average over the four months; to the contrary there was a slight but significant improvement. It is important to note that these interactions did not reach significance with the Bonferroni correction, but the simple slopes analyses supported this finding with the correction.

Previous research has shown contradictory relations of support to health in youth with type 1 diabetes, including research that has documented relations to health problems (Van Vleet & Helgeson, 2020). Indeed, this prior research was the impetus for our third goal of examining several explanations as to why support would be related to health difficulties. Although we examined several mediators, we did not learn from this dataset why friend support was not more strongly linked to good health outcomes.

Only one of the potential mediators accounted for any of our longitudinal relations—information sharing. Information sharing appeared as a mediator of the link between friend general support and an improvement in HbA1c over time, but the mediation was not in the direction anticipated. In the context of friend support, there was more information sharing but this information sharing appeared to be connected to changes in HbA1c that were in an adverse direction. In this case, are youth sharing information with their friends in anticipation of future problems? Alternatively, are youth sharing information with their friends as a replacement for working together with parents to manage diabetes? This could imply a loss of parent support as a possible mechanism. Clearly, more research is needed to investigate this possibility.

A second mediator that we investigated is perceived friend responsiveness, hypothesizing that conflictual relationships would lead youth to perceive that friends would not be responsive to their needs and supportive relationships would lead youth to perceive that friends would be responsiveness to their needs. Indeed, we found evidence that supportive friendships (general and diabetes-specific) were connected to anticipating a more positive response from peers and conflictual relationships (general and diabetes-specific) were connected to anticipating a more negative response from peers. Longitudinal analyses strengthened these claims, suggesting that supportive and conflictual friendships could lead to changes in one’s expectations of how responsive peers would be. However, there was no evidence that this responsiveness—at least at T1—explained any of the connections of support or conflict to outcomes.

In this study, we only examined mediation for our longitudinal relations because mediation of cross-sectional relations is not informative with respect to causality. An optimal test of mediation would require at least three time points to assess independent variable, mediator, and outcome. Because we only had two timepoints, we examined the connection of the independent variable to the mediator at T1 and the mediator’s connection to changes in the outcome between T1 and T2. Future research should employ at least three waves of data collection to provide a stronger test of mediation.

Future research should also consider the timescale to use in capturing changes in relationships at this age. Daily or weekly reports of peer relationships and health behavior might be more informative. We chose a 4-month period to span the Fall and Spring semesters of school, but this length of a time period might not have captured the fluctuations in relationships during adolescence.

Before concluding, we note several important study limitations. First, we had differential attrition with regard to race, household structure, and the use of an insulin pump, all in the direction suggesting that the least advantaged persons were less likely to remain the study. This underscores the need to develop additional methods to retain people with fewer resources in longitudinal studies. Differential attrition also limits the generalizability of our longitudinal findings. Second, most of the relations were cross-sectional rather than longitudinal. Thus, more research is needed to discern the causal direction between friend relationships and health. Third, the vast majority of youth were non-Hispanic White, making it not feasible to examine distinct ethnic or racial groups. Thus, our race variable is largely a comparison of non-Hispanic White to non-Hispanic Black persons. Relationships may play a stronger role among youth from more collectivistic races, ethnicities, and cultures. Fourth, some of the friend scales had less than ideal reliabilities, suggesting the importance of replication and future work on scale validation. Fifth, another important indicator of psychological health—anxiety—should be considered in future research, as it also has been linked to diabetes outcomes (Buchberger et al., 2016). Finally, due to COVID-19, we had to shift to using capillary dried blood spot kits to measure HbA1c which are not the same as samples collected from the DCA Vantage commonly used in the clinic.

Researchers and clinicians alike tend to focus on family relationships among youth with type 1 diabetes and neglect to study friend relationship variables. The relationship literature at large tends to focus on support rather than conflict. Recognizing that diabetes is only one part of an adolescent’s life, it would be helpful if health care professionals spent some time with youth discussing their peer relationships, specifically difficulties that might arise because of diabetes. These results suggest that peer support programs aimed at youth with type 1 diabetes should focus more on fostering general connections with peers and reducing problematic interactions surrounding diabetes rather than trying to involve peers in the management of diabetes.

One of the unique aspects of the present study is the large number of adolescents who were using technology (60% insulin pumps and 79% continuous glucose monitors). While the intention of both devices is to improve diabetes health, an anticipated side benefit is that these devices enable diabetes care to be more easily woven into everyday life. However, these devices also make diabetes more public to friends which could bring unwanted attention to youth. Little is known about the interface between diabetes technology and interactions with friends—an important avenue for future research.

Our findings demonstrate that friends play an important role in the lives of youth with type 1 diabetes—especially females, and that conflictual relationships with friends may impact psychological health as well as diabetes health. Future research needs to continue to understand the conditions under which and the reasons as to why friend support—especially diabetes-specific support—is not helpful and could be harmful for youth with type 1 diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Abigail Vaughn for overseeing the project and to Wyatt Macejka, Emma Fenstermaker, Tate Miner, and Tiona Jones for data collection.

Contributor Information

Vicki S Helgeson, Department of Psychology, Carnegie Mellon University, USA.

Fiona S Horner, Department of Psychology, Carnegie Mellon University, USA.

Harry T Reis, University of Rochester, USA.

Nynke M D Niezink, Department of Data Science and Statistics, Carnegie Mellon University, USA.

Ingrid Libman, UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, USA.

Author Contributions

Vicki S. Helgeson (Conceptualization [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Project administration [equal], Writing – original draft [equal], Writing – review & editing [equal]), Fiona S. Horner (Formal analysis [supporting], Writing – review & editing [equal]), Harry T. Reis (Writing – review & editing [supporting]), Nynke niezink (Writing – review & editing [supporting]), and Ingrid Libman (Writing – review & editing [supporting]).

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data can be found at: https://academic.oup.com/jpepsy.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK115384).

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- Bank B. J., Hansford S. L. (2000). Gender and friendship: why are men’s best same-sex friendships less intimate and supportive? Personal Relationships, 7(1), 63–78. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2000.tb00004.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barry C. M., Madsen S. D., DeGrace A. (2016). Growing up with a little help from their friends in emerging adulthood. In Arnett J. J. (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Emerging Adulthood (pp. 215–229). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barry C. M. N., Madsen S. D., Nelson L. J., Carroll J. S., Badger S. (2009). Friendship and romantic relationship qualities in emerging adulthood: differential associations with identity development and achieved adulthood criteria. Journal of Adult Development, 16(4), 209–222. 10.1007/s10804-009-9067-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauminger N., Finzi-Dottan R., Chason S., Har-Even D. (2008). Intimacy in adolescent friendship: the roles of attachment, coherence, and self-disclosure. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(3), 409–428. 10.1177/0265407508090866 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin K. S., Davies W. H., Jastrowski K. E., Hains A. A., Parton E. A., Alemzadeh R. (2006). Contextual assessment of problematic situations identified by insulin pump using adolescents and their parents. Families, Systems and Health, 24(1), 33–44. 10.1037/1091-7527.24.1.33 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin K. S., Rabideau E. M., Hains A. A. (2012). Empirically derived patterns of perceived stress among youth with type 1 diabetes and relationships to metabolic control. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37(9), 990–998. 10.1093/jpepsy/jss080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt T., Keefe K. (1995). Friends’ influence on adolescents’ adjustment to school. Child Development, 66(5), 1312–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchberger B., Huppertz H., Krabbe L., Lux B., Mattivi J. T., Siafarikas A. (2016). Symptoms of depression and anxiety in youth with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 70, 70–84. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu P. S., Saucier D. A., Hafner E. (2010). Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(6), 624–645. 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.6.624 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Commissariat P. V., Kenowitz J. R., Trast J., Heptulla R. A., Gonzalez J. S. (2016). Developing a personal and social identity with type 1 diabetes during adolescence: a hypothesis generative study. Qualitative Health Research, 26(5), 672–684. 10.1177/1049732316628835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox E. D., Fritz K. A., Hansen K. W., Brown R. L., Rajamanickam V., Wiles K. E., Fate B. H., Young H. N., Moreno M. A. (2014). Development and validation of PRISM: a survey tool to identify diabetes self-management barriers. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 104(1), 126–135. 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross S. E., Madson L. (1997). Models of the self: self-construals and gender. Psychological Bulletin, 122(1), 5–37. 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete E. M., Stephens M. A. P., Mickelson K. D., Druley J. A. (2007). Couples’ support provision during illness: the role of perceived emotional responsiveness. Families, Systems, and Health, 25(2), 204–217. 10.1037/1091-7527.25.2.204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foster N. C., Beck R. W., Miller K. M., Clements M. A., Rickels M. R., Dimeglio L. A., Maahs D. M., Tamborlane W. V., Bergenstal R., Smith E., Olson B. A., Garg S. K. (2019). State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016-2018. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics, 21(2), 66–72. 10.1089/dia.2018.0384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner D. M. (1990). Eating Disorder Inventory-2. Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Hains A. A., Berlin K. S., Hobart Davies W., Smothers M. K., Sato A. F., Alemzadeh R. (2007). Attributions of adolescents with type 1 diabetes related to performing diabetes care around friends and peers: the moderating role of friend support. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(5), 561–570. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays R. D., Dimatteo M. R. (1987). A short-form measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 51(1), 69–81. 10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson V. S., Berg C. A., Raymaekers K. (2023). Topical review: youth with type 1 diabetes: what is the role of peer support? Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 48(2), 176–180. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsac083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson V. S., Lopez L. C., Kamarck T. (2009). Peer relationships and diabetes: retrospective and ecological momentary assessment approaches. Health Psychology, 28(3), 273–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson V. S., Reynolds K. A., Escobar O., Siminerio L., Becker D. (2007). The role of friendship in the lives of male and female adolescents: does diabetes make a difference? Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(1), 36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson V. S., Reynolds K. A., Siminerio L., Escobar O., Becker D. (2008). Parent and adolescent distribution of responsibility for diabetes self-care: links to health outcomes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(5), 497–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. P., Lynch M. E. (1983). The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In Brooks-Gunn J., Petersen A. C. (Eds.), Girls at Puberty (pp. 201–228). Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jayawickreme E., Infurna F. J., Alajak K., Blackie L. E. R., Chopik W. J., Chung J. M., Dorfman A., Fleeson W., Forgeard M. J. C., Frazier P., Furr R. M., Grossmann I., Heller A. S., Laceulle O. M., Lucas R. E., Luhmann M., Luong G., Meijer L., McLean K. C., Zonneveld R. (2021). Post-traumatic growth as positive personality change: challenges, opportunities, and recommendations. Journal of Personality, 89(1), 145–165. 10.1111/jopy.12591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King P. S., Berg C. A., Butner J., Butler J. M., Wiebe D. J. (2014). Longitudinal trajectories of parental involvement in type 1 diabetes and adolescents’ adherence. Health Psychology, 33(5), 424–432. 10.1037/a0032804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca A. M., Swales T., Klemp S., Madigan S. (1988). Self-care behaviors among adolescents with diabetes. Ninth Annual Sessions of the Society of Behavioral Medicine.

- Lam C. B., Mchale S. M., Crouter A. C. (2014). Time with peers from middle childhood to late adolescence: developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Development, 85(4), 1677–1693. 10.1111/cdev.12235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau J. P., Barrett L. F., Rovine M. J. (2005). The interpersonal process model of intimacy in marriage: a daily-diary and multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 314–323. 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin A. B., Lagreca A. M., Geffken G. R., Williams L. B., Duke D. C., Storch E. A., Silverstein J. H. (2009). Validity and reliability of an adolescent and parent rating scale of type 1 diabetes adherence behaviors: the self-care inventory (SCI). Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(9), 999–1007. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden-Andersen S., Markiewicz D., Doyle A.-B. (2009). Perceived similarity among adolescent friends. Journal of Early Adolescence, 29(5), 617–637. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Pyatak E. A., Peters A. L., Wood J. R., Kipke M., Cohen M., Sequeira P. A. (2015). Patient perspectives on peer mentoring: type 1 diabetes management in adolescents and young adults. Diabetes Educator, 41(1), 59–68. 10.1177/0145721714559133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik J. A., Koot H. M. (2012). Assessing diabetes support in adolescents: factor structure of the modified Diabetes Social Support Questionnaire (DSSQ-Friends). Diabetic Medicine, 29(8), e232–e240. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03677.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattacola E. (2020). “They think it’s helpful, but it’s not”: a qualitative analysis of the experience of social support provided by peers in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 27(4), 444–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihlaskari A. K., Wiebe D. J., Troxel N. R., Stewart S. M., Berg C. A. (2018). Perceived peer support and diabetes management from adolescence into early emerging adulthood. Health Psychology, 37(11), 1055–1058. 10.1037/hea0000662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raymaekers K., Oris L., Prikken S., Moons P., Goossens E., Weets I., Luyckx K. (2017). The role of peers for diabetes management in adolescents and emerging adults with type 1 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabetes Care, 40(12), 1678–1684. 10.2337/dc17-0643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis H. T., Gable S. L. (2015). Responsiveness. Current Opinion in Psychology, 1, 67–71. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. (2012). Iavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin K. H., Bukowski W. M., Parker J. G. (2006). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In W. Damon, R. M Lerner, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology. (Issue May). Wiley, New York. 10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sayler K., Zhang X., Steinberg L., Belsky J. (2022). Parenting, peers and psychosocial adjustment: are the same—or different—children affected by each? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(3), 443–457. 10.1007/s10964-022-01574-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz-Mette R. A., Shankman J., Dueweke A. R., Borowski S., Rose A. J. (2020). Relations of friendship experiences with depressive symptoms and loneliness in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146(8), 664–700. 10.1037/bul0000239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz A., Winkler Metzke C., Steinhausen H. C. (2020). Development of perceived familial and non-familial support in adolescence; findings from a community-based longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(October), 486915–486911. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.486915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton S. C. E., Slatcher R. B., Reis H. T. (2019). Relationships, health, and well-being: the role of responsiveness. In Schoebi D., Campos B. (Eds.), New Directions in the Psychology of Close Relationships (pp. 118–135). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Steel J. M., , YoungR. J., , LloydG. G., & , Macintyre C. C. (1989). Abnormal eating attitudes in young insulin-dependent diabetics. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 515–521. 10.1192/bjp.155.4.515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L., Morris A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 83–110. 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson L. P., Rose A. J. (2009). Friends’ knowledge of youth internalizing and externalizing adjustment: accuracy, bias, and the influences of gender, grade, positive friendship quality, and self-disclosure. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(6), 887–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot F., Nouwen A., Gingras J., Gosselin M., Audet J. (1997). The assessment of diabetes-related cognitive and social factors: the Multidimensional Diabetes Questionnaire. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 20(3), 291–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoorn J., van Dijk E., Meuwese R., Rieffe C., Crone E. A. (2016). Peer influence on prosocial behavior in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(1), 90–100. 10.1111/jora.12173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vleet M., Helgeson V. S. (2020). Benefits and detriments of friend and peer relationships among youth with type 1 diabetes: a review. In Delamater A., Marrero D. (Eds.), Behavioral Diabetes. Ecological Perspectives. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Weissberg-Benchell J., Antisdel-Lomaglio J. (2011). Diabetes-specific emotional distress among adolescents: feasibility, reliability, and validity of the problem areas in diabetes-teen version. Pediatric Diabetes, 12(4 Pt 1), 341–344. 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2010.00720.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissberg-Benchell J., Glasgow A. M., Tynan W. D., Wirtz P., Turek J., Ward J. (1995). Adolescent diabetes management and mismanagement. Diabetes Care, 18(1), 77–82. 10.2337/diacare.18.1.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young V., Eiser C., Johnson B., Brierley S., Epton T., Elliott J., Heller S. (2013). Eating problems in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Diabetic Medicine, 30(2), 189–198. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03771.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajdel M., , HelgesonV. S., , SeltmanH. J., , KorytkowskiM. T., & , Hausmann L. R. M. (2018). Daily Communal Coping in Couples With Type 2 Diabetes: Links to Mood and Self-Care. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52(3), 228–238. 10.1093/abm/kax047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.