Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this article was to examine associations between metabolic syndrome and its individual components with cognitive function among rural elderly population in northeast China.

Methods:

Our study included 1047 residents aged older than 60 years in a northeast rural area. All were interviewed and data were obtained including sociodemographic and medical histories. Cognitive function was assessed by Mini-Mental State Examination. Metabolic syndrome was defined by NCEP-ATP III.

Results:

After adjusted for confounding factors, metabolic syndrome was inversely associated with cognitive function (odds ratio [OR] = 1.79; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.06-3.01) especially in participants aged less than 70 years old (OR = 2.60; 95% CI: 1.27-5.26). In addition, participants with metabolic syndrome had worse language function, which is a part of cognitive function (OR = 2.64; 95% CI: 1.39-5.00). Individual metabolic syndrome components, especially abdominal obesity and hyperglycemia, had significant association with cognitive function (OR = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.56-0.92 and OR = 1.41; 95% CI: 1.12-1.78, respectively).

Conclusions:

Abdominal obesity might be a protective factor for cognitive function. However, hyperglycemia might be a risk factor.

Keywords: abdominal obesity, cognitive function, elderly, ·metabolic syndrome, MMSE

Introduction

Cognitive disorder includes mild cognitive impairment and dementia. The damage of dementia can reach the degree that affects the ability of society and daily life, and the types of dementia with the highest incidence include Alzheimer’s disease (AD), vascular dementia, and mixed dementia. It was reported that the number of people with dementia in China had increased to 9.19 million in 2010. 1 A recent research showed that the prevalence rate of dementia among people older than 60 years was 7.7% in rural area in northern China. 2 With the increasing aging population, China will confront with a serious problem that more elderly people may have cognitive disorder.

In recent years, some studies have found that metabolic syndrome (MetS) and its individual components (including hypertension, hyperglycemia, abdominal obesity, and other cardiovascular risk factors of the syndrome) have an inverse association with cognitive performance. 3 -5 However, several studies had not yet found the association between MetS and cognitive disorders. 6,7 Difference in sample size, lifestyle, study design may lead to some inconsistencies in conclusions . 8 The major mechanisms of MetS, such as insulin resistance (IR) and hyperinsulinemia, affect cognitive function. In the cerebral cortex, MetS can lead to a decrease in glucose use and energy metabolism. 9 Additionally, it also can deposit β amyloids and increase the phosphorylation of τ proteins. 10 The results of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in the United States showed that the age of standardized MetS prevalence increased from 29.2% to 34.2% during 1999 to 2006. 11 Asian countries also have found similar growth trends. 12

In China, about 70% of population lives in rural areas. 13 A recent study found that the incidence of AD in rural areas was higher than that in urban areas. 14 In addition, in recent decades, China is undertaking the construction of urbanization. It not only developed economy but also brought lots of healthy problems, such as diet structure change (intake of high fat, high protein diets) and less physical activity. And it has reported higher prevalence of MetS in rural China than in some cities. 15 Some studies have described the relationship between MetS and cognitive function in the Chinese population. 16,17 However, most of them focused on the population in urban. Little information is available about MetS in the rural areas of northeast China, which is relatively poor and less developing compared with urban. To better understand the relationship between MetS or its individual components and cognitive function in the rural population in Northeast China. Therefore, we investigated among older adults aged 60 years and above in rural areas of Shenyang, Liaoning Province, Northeast China.

Method

Study Population

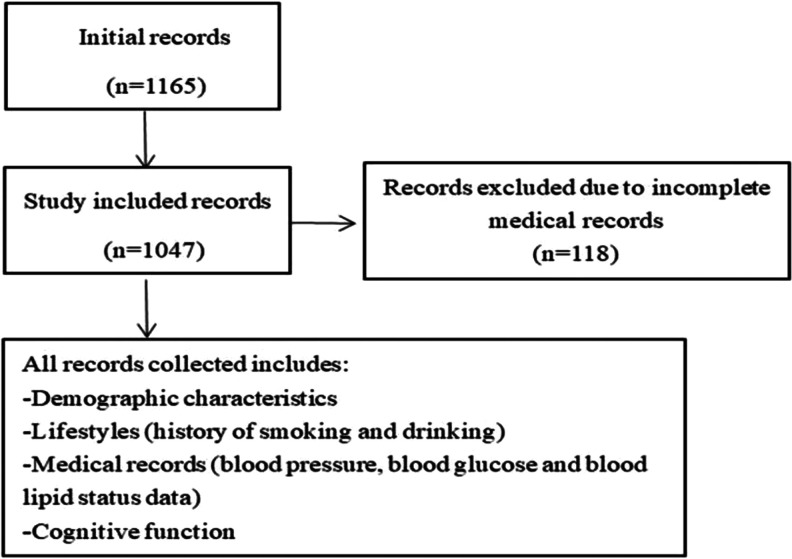

This study was performed in the Sujiatun district, a northern rural area in Shenyang, China. All volunteers who have lived at Sujiatun district at least 6 months were included from every village. With the help of the local village doctors, the villagers were informed the study protocol and were asked to participate in the study. We contacted 1390 volunteers, but 225 volunteers refused to participate in the survey. As shown in Figure 1, in our study, we recruited 1165 volunteers, and of whom, 118 volunteers were excluded due to incomplete medical records. This study was approved by the ethical standards of the Committee on Human Experimentation of China Medical University, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the enrollment in this study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for study.

Data Collection

Each participant completed a standardized questionnaire through a face-to-face interview. The participants’ demographic characteristics (age, education years, and sex), medical histories (history of hypertension and diabetes), and lifestyles (history of smoking and drinking) were collected by self-reported. Cognitive function was assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), 18 which is the most generally used instrument for comprehensive assessment of cognitive performance through orientation (10 points), registration (3 points), attention and calculation (5 points), recall (3 points), and language (9 points). 19 In this study, body weight, waist circumference (WC), and height were measured twice using standardized instruments. Blood pressure, blood glucose, and blood lipid status data were primarily extracted from the participants’ medical records.

Definition of MetS

Presence of MetS was defined according to the diagnostic criteria of the American Heart Association revised project of the US National Cholesterol Education Program Guidelines–Adult Treatment Panel Criteria as having 3 or more of the following components 12 : (1) abdominal obesity (WC) ≥90 cm in man and ≥80 cm in women, (2) hypertriglyceridemia: fasting plasma triglycerides ≥1.7 mmol/L, (3) systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥130 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥85 mm Hg or have a history of hypertension, (4) fasting blood glucose (FBG) ≥5.6 mmol/L or have a history of diabetes, and (5) decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C): fasting HDL-C <1.0 mmol/L in mans and <1.3 mmol/L in women. We divided participants into 3 groups: (1) healthy participants, (2) participants with MetS, and (3) the others are no MetS.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of variance or χ2 test was used to examine correlations between sample characteristics and MMSE categories. The MMSE score was classified in tertiles as low (≤23), middle (24-27), and high (≥28) levels of cognition. Each cognitive domains score was classified into 2 groups based on the median as follows: orientation (0-9 and 10), attention and calculation (0-3 and 4-5), recall (0-2 and 3), registration (0-2 and 3), and language performance (0-7 and 8-9), respectively. Ordinal logistic regression was used to explore the association among MetS and its components with MMSE score and examine the relationship between MetS and cognitive domains. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 20.0 software. P value <.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Result

Description of the Population

The characteristics of the participants by cognitive function are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 69.98 ± 5.58 years old, with a range from 60 to 93 years old. Participants with low level of cognitive function were older and had lower level of education, higher SBP, higher DBP, and higher FBG than participants with high level of cognitive function. In addition, they also had more participants with a habit of smoking.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Elderly Population by Levels of Cognitive Function.

| Characteristic of Elderly Population | Characteristics of Cognitive Level | Total (1047) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (384) | Middle (316) | High (347) | |||

| Mean (SD) | |||||

| Age (years) | 72.42 (6.13) | 69.26 (5.01) | 67.92 (4.30) | 69.98 (5.58) | <.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 62.42 (9.86) | 63.22 (9.89) | 63.84 (9.24) | 63.13 (9.68) | .139 |

| WC | 82.28 (9.95) | 83.49 (9.97) | 83.42 (9.17) | 83.02 (9.72) | .169 |

| SBP | 139.87 (16.67) | 135.73 (16.83) | 135.58 (16.40) | 137.20 (16.74) | <.001 |

| DBP | 86.04 (10.43) | 84.79 (9.99) | 83.89 (9.25) | 84.95 (9.95) | .014 |

| FBG | 6.15 (1.98) | 5.87 (1.29) | 5.60 (1.36) | 5.88 (1.61) | <.001 |

| TG | 1.88 (1.12) | 1.79 (0.97) | 1.81 (1.04) | 1.83 (1.05) | .478 |

| HDL-C | 1.47 (0.78) | 1.37 (0.26) | 1.44 (0.33) | 1.42 (0.50) | .471 |

| Education years | 2.93 (0.15) | 2.72 (0.15) | 2.42 (0.13) | 5.74 (2.89) | <.001 |

| n (%) | |||||

| Male | 157 (40.9%) | 140 (44.3%) | 158 (45.5%) | 455 (43.5%) | .420 |

| MetS | 176 (45.8%) | 129 (40.8%) | 141 (40.6%) | 446 (42.6%) | .052 |

| Smoking | 115 (29.9%) | 105 (33.2%) | 92 (26.5%) | 312 (29.8%) | <.001 |

| Drinking | 89 (23.2%) | 90 (28.5%) | 91 (26.2%) | 270 (25.8%) | .146 |

Abbreviations: DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FBG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MetS, participants with metabolic syndrome; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TG, triglycerides; WC, waist circumference.

Correlation Between MetS and Cognitive Function

The correlation between MetS and MMSE score is presented in Table 2. Compared with healthy participants, participants with MetS had lower level of cognitive function (odds ratios [ORs] = 1.79, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.06-3.01], after adjusting for confounding factors, participants aged less than 70 years old (OR = 2.60, 95% CI: 1.27-5.26). However, participants aged more than 70 years have no significant association between MetS and MMSE (OR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.45-2.35).

Table 2.

Odds Radios From an Ordinal Logistic Regression Model of the Association Between MetS Status and Cognitive Function.a

| MetS Status | ≤70 Years | >70 Years | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| No MetS | 1.91 (0.95-3.82) | 1.25 (0.56-2.83) | 1.79 (1.06-3.01) |

| P trend | .020 | .789 | .057 |

Abbreviation: MetS, participants with metabolic syndrome.

aAdjusted for age, education years, sex, smoking, and drinking.

Relationship Between MetS and Cognitive Domains

Table 3 shows the relationship between MetS and cognitive domains after adjusting for age, sex, education years, and history of drinking and smoking. The result showed that participants with MetS had lower language performance than healthy participants (OR = 2.64, 95% CI: 1.39-5.00), but they had nonsignificant correlations with other domains.

Table 3.

Odds Radios From an Ordinal Logistic Regression Model of the Relationship Between MetS and Cognitive Domains.a

| MetS Status | Orientation | Registration | Attention and Calculation | Recall | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| No MetS | 1.38 (0.71-2.70) | 1.55 (0.87-2.78) | 1.38 (0.78-2.42) | 1.52 (0.87-2.68) | 2.33 (1.24-4.37) |

| MetS | 1.22 (0.62-2.41) | 1.21 (0.67-2.18) | 1.60 (0.90-2.83) | 1.63 (0.92-2.90) | 2.64 (1.39-5.00) |

| P trend | .943 | .519 | .081 | .117 | .014 |

Abbreviation: MetS, participants with metabolic syndrome.

aAdjusted for age, sex, drinking, smoking, and education year.

Associations of Individual MetS Components With Cognitive Function

Table 4 shows after adjusting age, sex, education years, and history of drinking and smoking, abdominal obesity and hyperglycemia were significantly associated with cognitive function. Moreover, these links still existed and further adjusted the other 4 components. Hyperglycemia was associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment (OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.12-1.77). However, abdominal obesity presented decreased risk of cognitive impairment (OR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.57-0.93).

Table 4.

Odds Radios From an Ordinal Logistic Regression Model of the Association Between Individual MetS Components With Cognitive Function.

| MetS Components | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal obesity | |||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 0.87 (0.70-1.09) | 0.78 (0.62-0.99) | 0.72 (0.56-0.92) |

| Hyperglycemia | |||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.55 (1.24-1.92) | 1.41 (1.12-1.77) | 1.41 (1.12-1.78) |

| High blood pressure | |||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.43 (1.14-1.79) | 1.18 (0.94-1.49) | 1.19 (0.93-1.52) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | |||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.07 (0.86-1.33) | 1.06 (0.85-1.35) | 1.05 (0.83-1.32) |

| Low HDL-C | |||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 0.76 (0.44-1.30) | 0.98 (0.56-1.72) | 1.07 (0.60-1.92) |

Abbreviations: HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MetS, metabolic syndrome.

aUnadjusted.

bAdjusted for age, sex, drinking, smoking, and education year.

cAdjusted for age, sex, drinking, smoking education year, and the other 4 metabolic syndrome components.

Discussion

Our study illustrated that MetS was associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment, but this relationship was not significant in participants aged more than 70 years. Interestingly, we also found that obesity (abdominal obesity), MetS individual component, presented an inverse association with cognitive impairment.

The result of our study showed that MetS was associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment in rural elderly population, which was in accordance with a previous study. A cross-sectional study from the Chinese community elderly population reported that participants with MetS were more likely to have mild cognitive impairment. 6 Further analysis also provided evidence that hyperglycemia, one of MetS components, had association with an increased risk of cognitive impairment, after adjusting the other 4 MetS components. Many studies reported that participants with hyperglycemia or diabetes had worse cognitive function. 9,20 In a population-based study in Southern Italy described a clear increased risk of cognitive decline connected to hyperglycemia, which was consistent with our result. 21 The biological mechanism of the relationship between MetS and cognitive impairment is still unclear. But research have come up with the hypothesis of IR, which suggested that IR can lead to the frontal cortex dysfunction and then affect cognitive function. 20 Our study also found MetS showed a significant impact on language function. Possible biological mechanism is that reduced glycemic control and microvascular changes may influence language function. 22,23 Indeed, IR and reduced glycemic control could implicate neuronal networks underlying cognition in widely distributed fields affecting the brain. Some studies have shown that MetS was not related to attention or memory, 24,25 which is consistent with our result. However, many researches showed MetS was associated with attention or memory. 26,27 The possible reasons are that different age composition, races, gender, survey methods, and cognitive assessment methods may lead to inconsistent results.

However, we didn’t find MetS was associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment in participants aged older than 70 years in our study, which was consistent with the previous study. 28 The reason may be that people died of cardiovascular diseases and people with severs MetS cannot survive before reaching older. In rural Northeast China, unhealthy diet consumed by many residents, such as high salt, high fat, could result in cardiovascular diseases, such as hypertension. In addition, participants with lower level of education in rural area get less healthy knowledge and not aware of unhealthy lifestyles which may promote severe cardiovascular diseases. It was found that the prevalence of hypertension was still high, but the control rate of hypertension was regrettably low. It showed that less than 50% were realized their diagnosis, less than 40% were taking antihypertensive medications, and only 6.0% were controlled; in addition, obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hyperuricemia have become the risk factors for people in northeast rural China. 29 Cardiovascular Disease Report 2017 in China found that the mortality CVD is still on the top, and CVD mortality in rural was higher than urban. 30

Interestingly, we found that abdominal obesity presented decreased risk for cognitive impairment. It was demonstrated that being underweight in old age increased the risk of dementia. 31 In addition, a Korean study suggested that obesity might be beneficial for cognition for older, which was consistent with our result. 32 However, the research on middle-aged people exhibited that obesity was a risk factor in cognitive function. 33 Possible reasons for inconsistent results may include, on the one hand, leptin, which is secreted by adipose tissue and can affect the functions of the hypothalamus and hippocampus. 34 Recent animal experiment also showed that leptin might improve cognition. 35 And the elderly had higher leptin levels than midlife. 36 On the other hand, carbohydrate, lipid, and protein metabolism have age-related regulatory changes, which might result in protective effect of obesity on dementia in elderly. 36 The effect of age on the relationship between obesity and cognitive impairment needs further research. Due to high salt, high fat diet and so on, in northeast rural area of China, the prevalence of abdominal obesity has grown and approached the rate in urban areas. 37 Therefore, it is necessary to have more prospective studies in this area to further explore the link between obesity and cognitive function in the elderly people.

Our finding also has limitations. Firstly, participants in our study live in rural areas for a long time, which cannot well represent the general Chinese older population. Secondly, because this is a cross-sectional study, cognitive function and MetS status were measured only at one point in time, and MetS could be greatly changed over time. So we cannot make causal inferences in our study. Thirdly, we did not adjust for all confounding factors, such as physical exercise and family history of cognitive impairment. Fourthly, the number of fully healthy participants in this study was only 63, which may affect results. In northeast China rural, the prevalence of hypertension is very high (74.4%) in elderly population, 28 and the number of participants with hypertension in our study accounted for 76.9% (data not shown in results). This may be the reason for the small number of participants who are fully healthy in this study. Finally, the cognition was assessed by only MMSE. Mini-Mental State Examination contains fewer cognitive domains compared to other assessments. Memory testing (only 3 words recall) and executive function (only 1 point) are relatively simple, and immediate recall and delayed recall are separated by a short time. Therefore, MMSE is less sensitive to screening for impairment of individual cognitive domain (memory, executive function) than other cognitive function evaluation scales. For participants with higher education level, the MMSE is too simple, which easily conceals the cognitive impairment of participants.

In summary, MetS as a syndrome showed the association with poor cognition in an elderly population in rural area of Shenyang, China. Younger elderly with MetS were more likely to have cognitive disorder than healthy participants. Prevention of MetS and its components might slow down cognitive impairment.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81402644).

ORCID iD: Qian Gao  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6291-6108

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6291-6108

References

- 1. Chan KY, Wang W, Wu JJ. et al. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia in China, 1990-2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9882):2016–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ji Y, Shi Z, Zhang Y. et al. Prevalence of dementia and main subtypes in rural northern China. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2015;39(5-6):294–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Forti P, Pisacane N, Rietti E. et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of dementia in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(3):487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frisardi V. Impact of metabolic syndrome on cognitive decline in older age: protective or harmful, where is the pitfall? J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(1):163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yaffe K. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive disorders: is the sum greater than its parts? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(2):167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen B, Jin X, Guo R. et al. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive performance among Chinese ≥50 years: a cross-sectional study with 3988 participants. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2016;14(4):222–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tournoy J, Lee DM, Pendleton N. et al. Association of cognitive performance with the metabolic syndrome and with glycaemia in middle aged and older European men: the European Male Ageing Study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26(8):668–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Watts AS, Loskutova N, Burns JM, Johnson DK. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive decline in early Alzheimer’s disease and healthy older adults. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;35(2):253–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. S Roriz-Filho J, Sá-Roriz TM, Rosset I. et al. (Pre)diabetes, brain aging, and cognition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792(5):432–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hamilton SJ, Watts GF. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes: pathogenesis, significance, and treatment. Rev Diabet Stud. 2013;10(2-3):133–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mozumdar A, Liguori G. Persistent increase of prevalence of metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults: NHANES III to NHANES 1999-2006. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):216–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institue, Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR. et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome. An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Executive summary. Cardiol Rev. 2005;13(6):322–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu Y, Rao K, Hsiao WC. Medical expenditure and rural impoverishment in China. J Health Popul Nutr. 2003;21(3):216–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jia J, Wang F, Wei C. et al. The prevalence of dementia in urban and rural areas of China. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zuo H, Shi Z, Hu X, Wu M, Guo Z, Hussain A. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and factors associated with its components in Chinese adults. Metabolism. 2009;58(8):1102–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li P, Quan W, Lu D. et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and cognitive impairment after acute ischemic stroke: a cross-sectional study in a Chinese population. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0167327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu M, He Y, Jiang B. et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and mild cognitive impairment and its age difference in a Chinese community elderly population. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015;82(6):844–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269(18):2386–2391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abbatecola AM, Paolisso G, Lamponi M. et al. Insulin resistance and executive dysfunction in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(10):1713–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tortelli R, Lozupone M, Guerra V. et al. Midlife metabolic profile and the risk of late-life cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;59(1):121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Albert ML, Spiro A, III, Sayers KJ. et al. Effects of health status on word finding in aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(12):2300–2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cahana-Amitay D, Albert ML, Ojo EA. et al. Effects of hypertension and diabetes on sentence comprehension in aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(4):513–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reijmer YD, van den Berg E, Dekker JM. et al. The metabolic syndrome, atherosclerosis and cognitive functioning in a non-demented population: the Hoorn Study. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219(2):839–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Viscogliosi G, Chiriac IM, Andreozzi P, Ettorre E. Executive dysfunction assessed by Clock-Drawing Test in older non-demented subjects with metabolic syndrome is not mediated by white matter lesions. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;69(10):620–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van den Berg E, Dekker JM, Nijpels G. et al. Cognitive Functioning in elderly persons with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome: the Hoorn study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26(3):261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dik MG, Jonker C, Comijs HC. et al. Contribution of metabolic syndrome components to cognition in older individuals. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(10):2655–2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Muller M, Tang MX, Schupf N, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Luchsinger JA. Metabolic syndrome and dementia risk in a multiethnic elderly cohort. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24(3):185–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li Z, Guo X, Zheng L, Yang H, Sun Y. Grim status of hypertension in rural China: results from Northeast China Rural Cardiovascular Health Study 2013. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2015;9(5):358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ma LY, Wu YZ, Wang W, Chen WW. Interpretation of the report on cardiovascular diseases in China. Chin J Cardiovasc Med. 2018;23(1):3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qizilbash N, Gregson J, Johnson ME. et al. BMI and risk of dementia in two million people over two decades: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(6):431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Noh HM, Oh S, Song HJ. et al. Relationships between cognitive function and body composition among community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosengren A, Skoog I, Gustafson D, Wilhelmsen L. Body mass index, other cardiovascular risk factors, and hospitalization for dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(3):321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Davidson TL, Kanoski SE, Walls EK, Jarrard LE. Memory inhibition and energy regulation. Physiol Behav. 2005;86(5):731–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harvey J, Shanley LJ, O’Malley D, Irving AJ. Leptin: a potential cognitive enhancer? Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33(pt 5):1029–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Emmerzaal TL, Kiliaan AJ, Gustafson DR. 2003-2013: a decade of body mass index, Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43(3):739–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guo X, Li Z, Guo L. et al. An update on overweight and obesity in rural Northeast China: from lifestyle risk factors to cardiometabolic comorbidities. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]