Abstract

Caregivers often tailor their language to infants’ ongoing actions (e.g., “are you stacking the blocks?”). When infants develop new motor skills, do caregivers show concomitant changes in their language input? We tested whether the use of verbs that refer to locomotor actions (e.g., “come”, “bring”, “walk”) differed for mothers of 13-month-old crawling (N = 16) and walking infants (N = 16), and mothers of 18-month-old experienced walkers (N = 16). Mothers directed twice as many locomotor verbs to walkers compared to same-age crawlers, but mothers’ locomotor verbs were similar for younger and older walkers. In real time, mothers’ use of locomotor verbs was dense when infants were locomoting, and sparse when infants were stationary, regardless of infants’ crawler/walker status. Consequently, infants who spent more time in motion received more locomotor verbs compared to infants who moved less frequently. Findings indicate that infants’ motor skills guide their in-the-moment behaviors, which in turn shape the language they receive from caregivers.

Keywords: developmental cascades, language input, motor development, dyadic interactions

Infants’ moment-to-moment motor actions generate rich, multi-modal information that in turn, facilitates learning (Gibson, 1988; Piaget, 1954). For example, manipulating objects facilitates learning that objects are 3 dimensional (Soska, Adolph, & Johnson, 2010). And crawling from place to place promotes advances in spatial cognition (Campos et al., 2000). Likewise, infants’ moment-to-moment motor actions have immediate consequences for their social interactions, including the language they receive from caregivers (e.g., Schatz, Suarez-Rivera, Kaplan, & Tamis-LeMonda, 2022). In real time, caregivers respond sensitively and contingently to infant actions by referring to the objects of infant play and the actions of infant movements (Custode & Tamis-LeMonda, 2020; Tamis-LeMonda, Kuchirko, & Tafuro, 2013; West, Fletcher, Adolph, & Tamis-LeMonda, 2022; West & Iverson, 2017; Yu & Smith, 2012). For example, caregivers name objects in synchrony with infants’ touch (e.g., “bear” as infant holds a teddy bear) and produce verbs that align with infants’ actions (e.g., “hug” as infant hugs a teddy bear; Liu, Zhang, & Yu, 2019; West, et al., 2022). The real-time connection between infants’ actions and their verb inputs may benefit their verb learning, particularly because verbs are among the most difficult parts of speech to learn (e.g., Gentner, 2006; Gleitman & Gleitman, 1992).

Given the real-time connection between infants’ actions and caregivers’ verb inputs, developmental changes in infants’ motor skills should instigate concomitant changes in caregivers’ verb use. When infants acquire a new motor skill, their changing behaviors should unlock new opportunities for verb learning—a developmental cascade from motor development to language input (West, et al., 2022). On this account, motor skill acquisition enables infants to move and behave in new ways, thereby creating opportunities for caregivers to produce the relevant verbs (e.g., “climb” when infant learns to ascend stairs, or “jump” when infant learns to jump). We propose that infants’ ability to walk has cascading effects on caregivers’ verb inputs. Walking upright enables infants to locomote faster and farther than they could while crawling (e.g., Adolph & Tamis-LeMonda, 2014). Even newly walking infants take twice as many steps as experienced crawlers, covering three times the distance as they move (Adolph et al., 2012). Thus, we hypothesize that walkers spend more time in motion during natural activity at home, and walkers’ enhanced locomotion elicits more frequent relevant verbs—like “go” and “step”—from their caregivers.

Changes in caregivers’ verb use across the second postnatal year provide partial support for the developmental cascade hypothesis. Caregivers direct more frequent and varied action verbs to 18-month-olds than they do to 13-month-olds (West, et al., 2022). Presumably, older infants engage in more advanced and varied motor activities than do younger infants, which could account for the difference in caregivers’ verb use. But, it is unclear whether this difference is driven by advances in motor skill, or more domain-general, maturational changes. In addition, learning to walk prompts changes in how caregivers verbally respond to their infant’s locomotor behavior (Schneider & Iverson, 2021). After infants begin to walk, caregivers respond more frequently to infants’ moving social bids; for example, by saying, “do you want to hug the bear?” when infant approaches to share a toy (Karasik, Tamis-LeMonda, & Adolph, 2014; West & Iverson, 2021).

When infants begin to walk, does that also unlock new opportunities for verb inputs? Prior work shows that caregivers’ verbs are often contextually connected to their infants’ actions from one moment to the next (e.g., Liu, Zhang, & Yu, 2019; West, et al., 2022). However, it is unknown whether newly acquired motor skills—like learning to walk—prompt a simultaneous shift in caregivers’ verb use. Thus, to test our hypothesized developmental cascade, we investigated associations between infants’ walking status and age and their mothers’ use of verbs that pertain to locomotion (hereafter, “locomotor verbs”) such as “come,” “go,” “bring,” “carry,” “crawl,” and “walk.” We used a unique age/skill-matched design to identify the independent effects of infant age (as in West, et al., 2022) and locomotor status (i.e., whether infants are crawlers or walkers). Specifically, we documented mothers’ use of locomotor verbs during everyday natural activity with three groups of infants: 13-month-old crawlers, 13-month-old walkers, and 18-month-old walkers. By comparing same-aged crawlers and walkers, we tested for an effect of locomotor status, with age held constant. By comparing younger and older walkers, we tested for an age effect, with locomotor status held constant.

In light of prior work showing that caregivers’ verbs are tailored to infants’ real-time actions (West et al., 2022) and evidence that learning to walk changes infants’ locomotor behavior (e.g., Adolph & Tamis-LeMonda, 2014; Adolph et al., 2012), we hypothesized that mothers direct more frequent and varied locomotor verbs to walkers than to crawlers. Thus, we predicted that 13-month-old walkers would be exposed to more locomotor verbs compared to same-aged crawlers, but 13- and 18- month-old walkers would be exposed to similar locomotor verb inputs. Alternatively, and contrary to the hypothesized cascade, mothers may direct more frequent and varied verb input to 18-month-old infants who have greater language skills than 13-month-old infants, regardless of locomotor status. Indeed, caregivers direct more language input overall to infants with larger vocabularies (e.g., Dailey & Bergelson, 2022).

In addition, we hypothesized that infants’ real-time locomotor behavior is the mechanism underlying mothers’ locomotor verb use. Thus, we predicted that infants’ sheer time in motion—regardless of whether crawling or walking—would elicit correspondingly frequent and varied locomotor verbs from their mothers. We also tested an alternative developmental cascade: Possibly infants’ developmental status as a “walker”—but not necessarily their moment-to-moment locomotion per se—influences the verbs mothers say. Indeed, caregivers perceive their infants to be more independent and intentional after babies learn to walk (Walle, 2016), which may consequently shape their speech to infants. This account predicts that—regardless of infants’ time in motion—walkers would receive different verb inputs than same-aged crawlers.

Method

Study materials are shared on the Databrary library (databrary.org). Videos and demographic data are shared with authorized investigators at nyu.databrary.org/volume/1322/slot/64469/−. The coding manual, Datavyu coding spreadsheets, and scripts for coding reliability and exporting data are publicly shared at nyu.databrary.org/volume/1322/slot/64470/−. Processed data and analysis scripts are publicly shared at nyu.databrary.org/volume/1322/slot/64471/−.

Participants

Three groups of infants and their mothers participated: 16 13-month-old crawlers (half boys; range = 12.72–13.41 months), 16 13-month-old walkers (half boys; range = 12.72–13.44 months), and 16 18-month-old walkers (half boys; range = 17.58–18.28 months). We established infants’ locomotor status through parent report. A researcher asked mothers when their infants first began to crawl and walk proficiently (for 3 meters without stopping, falling, or holding onto anything) in a structured interview. Mothers were encouraged to use calendars, photos, or cellphone videos to corroborate their memories.

All infants were first-born and born at term, with no birth complications or known disabilities. Mothers reported their infants’ race and ethnicity as: N = 33 White, N = 5 Hispanic or Latino, N = 3 Asian, N = 1 Black, N = 10 multiple racial/ethnic identities, and N = 1 other race (Indian). All families were from monolingual English-speaking and mostly upper- to middle-class households, as measured by Nakao-Treas occupational prestige scores: M = 73.05, range = 30–92 (Nakao-Treas, 1994). Families were recruited through pediatric groups in New York City and purchased mailing lists, brochures, referrals, and parenting websites.

Procedure

Dyads were video recorded during everyday home activities by a researcher with a handheld camera. Recordings lasted for one (N = 12) or two hours (N = 32)1. Visits were scheduled between naptimes and mealtimes and when only mother was expected to be present. An additional family member arrived home briefly for 3 dyads but stayed in a separate room until the video recording concluded. Mothers were informed that the purpose of the study was to document infants’ natural everyday activity and were instructed to ignore the researcher and go about their routines. The researcher focused on the infant, attempting to keep infant’s full body in frontal view; remained at the periphery of the room; and did not interact with the infant or mother while recording. Families received a $75 gift card or photo album of their infants as souvenirs of participation.

Data Coding, Reduction, and Reliability

Behavioral data were coded in three passes using Datavyu software (www.datavyu.org): (1) transcripts of maternal speech; (2) mothers’ use of locomotor verbs (“get,” “walk,” “bring”) and; (3) infants’ locomotor behaviors of crawling and walking. To assess inter-observer reliability for coding of mothers’ verbs and infants’ locomotion, a primary coder scored the entire session and a second coder independently scored 25% of each session. Coders reviewed and discussed disagreements after every few files to prevent drift. Cohen’s κs were 0.96 for locomotor verbs, and 0.97 for infant locomotion, ps < .001. Inter-coder correlations for locomotor bout duration were 0.85, p < .001. Typos and careless errors were corrected for final analyses to prevent propagating known errors; for true disagreements (e.g., one coder thought infant was moving and the other did not), we retained the primary coder’s data.

Transcription.

An experienced coder transcribed mother speech verbatim, time-stamped at the onset of each utterance, using the procedures and protocols developed for the PLAY project (www.play-project.org).

Verb Types.

Using the transcripts, a primary coder identified all verb phrases that referred to infants’ locomotor actions. Verbs were credited if they specified an action referring to walking steps, crawling steps, jumping, hopping, or otherwise moving the entire body through space, regardless of past, present, or future tense (Did you bring me your ball? You’re running fast! You will go outside). Verbs that specified postural transitions such as standing and sitting (e.g., sit, have a seat) or referred to mothers’ actions on the infant (e.g., lifting infant out of a highchair) did not count. We excluded prohibitive verbs (e.g., don’t go into the kitchen!), song lyrics (do the hokey pokey), commonly used slang (c’mon), and verbatim reading of text from a book.

Infant Locomotion.

Infant locomotion was coded using the criteria and manuals developed by the PLAY project (www.play-project.org). In keeping with the PLAY locomotion coding scheme, we identified bouts of infant locomotion when infants took steps in any direction by either walking or crawling (including non-hands-and-knees crawling styles like bum-shuffling and hitching). Bouts of locomotion were coded regardless of whether infants balanced independently or received support from furniture or their mothers. Walking bouts were counted if infants took at least one step. Crawlers’ upright steps (e.g., while cruising) counted as walking bouts. Crawling bouts were counted only when the infant took at least three steps based on movements of the knees to prevent overcounting crawling based on arm movements and transitions in posture. Each locomotor bout ended when the infant stopped moving for at least one second.

Density of Locomotor Verbs.

Next, we documented the density of locomotor verbs during infant locomotion and during stationary play. Using the previously identified verb and locomotion codes, we calculated the rate of locomotor verbs per minute that occurred during infant locomotion (i.e., total number of verbs during locomotion divided by total time spent locomoting), and the rate of locomotor verbs per minute during stationary play.

Data Analysis

We tested associations between infants’ locomotor status and caregivers’ language input (i.e., rate of utterances per hour, rate of locomotor verbs per hour, and unique locomotor verbs per hour) in a series of ANOVAs with group (13-month-old crawlers, 13-month-old-walkers, and 18-month-old walkers) as a between-subject variable. We tested significant group effects using two pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni-adjusted alpha values: 13-month-old crawlers versus 13-month-old walkers (locomotor group comparison with age held constant), and 13-month-old walkers versus 18-month-old walkers (age group comparison with locomotor status held constant).

Additionally, we tested whether infants’ real-time locomotor behavior (moment-to-moment movement during the session) was associated with the rate and variety of mothers’ locomotor verbs using Pearson bivariate correlations. Finally, we compared the temporal density of mothers’ locomotor verbs while infants were moving versus stationary using a repeated measures ANOVA with group as a between subject variable and infant activity (in motion, stationary) as a within-subject variable.

Results

The frequency of utterances is associated with infant age, but not locomotor status

First, we examined whether the quantity of language input differed across groups. In general, mothers spoke to their infants frequently, directing M = 13.59 utterances per minute to them (SD = 5.09). The frequency of mothers’ utterances increased with infant age. Mothers of 18-month-old walkers produced more utterances per hour (M = 16.60; SD = 4.81) compared to mothers of 13-month-old walkers (M = 10.79; SD = 4.23). However, infants’ locomotor status had no bearing on the frequency of mothers’ utterances. The 13-month-old crawlers (M = 13.39; SD= 4.69) received just as many utterances as the 13-month-old-walkers. The ANOVA confirmed a significant group effect, F(2, 47) = 6.46, p = .003, and pairwise comparisons indicated that 18-month-old walkers received more utterances than did 13-month-old walkers, p = .002, with no differences between the 13-month-old groups, p = .348.

Mothers of walkers direct more frequent and diverse locomotor verbs to their infants compared to mothers of crawlers

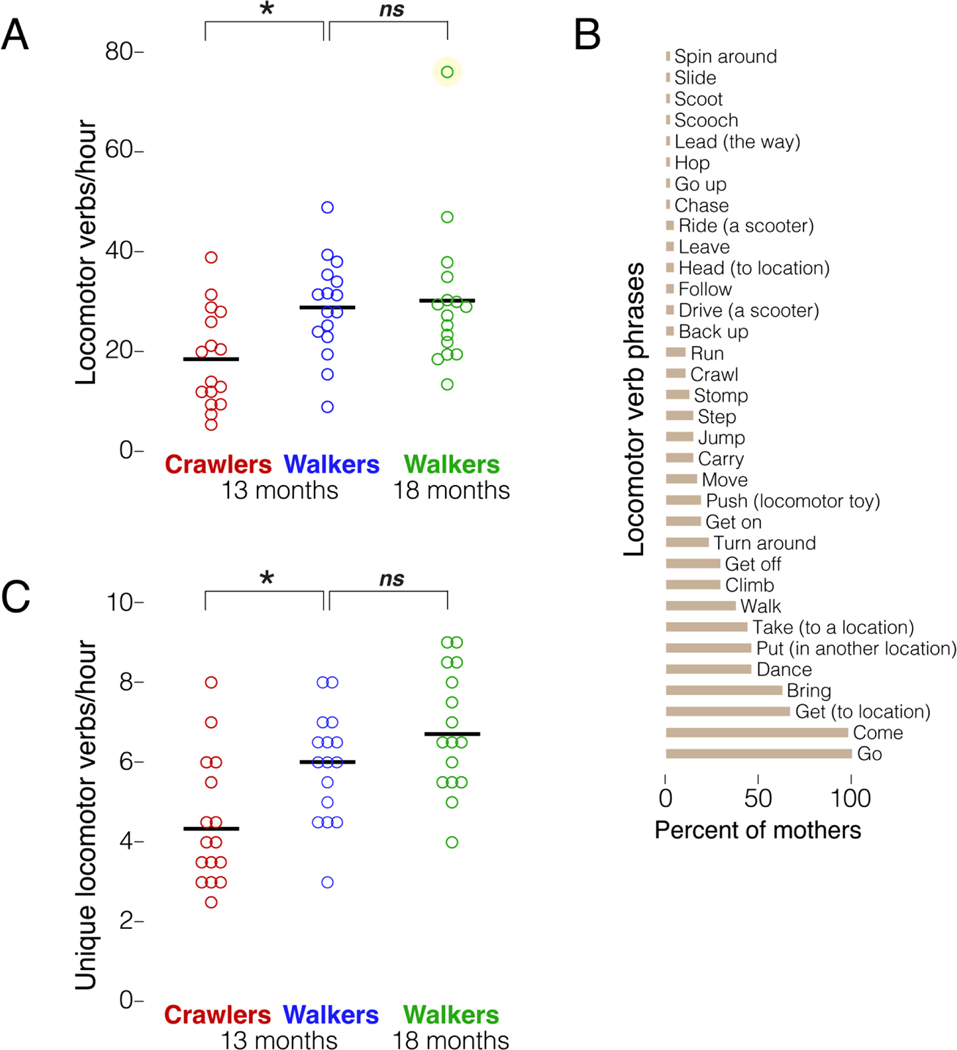

Although overall quantity of language input did not differ for crawling and walking infants, it’s possible that mothers may use different types of language when speaking to crawlers and walkers. So, we examined whether language input that is directly relevant to locomotion—locomotor verbs like “come” or “bring”—differed across groups. Mothers of walkers produced more locomotor verbs than did mothers of crawlers (Figure 1A). Indeed, 13- and 18-month-old walking infants received Ms = 28.91, 30.23 locomotor verbs per hour respectively (SDs = 9.73, 14.73)2 relative to 13-month-old crawlers (M = 18.61, SD = 9.81). The ANOVA confirmed a main effect of group, F(2, 47) = 4.76, p = .013, and pairwise comparisons indicated that crawlers received significantly fewer locomotor verbs than same-aged walkers, p = .048, with no differences between walking groups, p = .985.

Figure 1.

Mothers’ locomotor verbs. Mothers of 13-month-old crawlers are depicted in red, 13-month-old walkers in blue, and 18-month-old walkers in green. (A) Rate of locomotor verbs for each mother. Graph shows that mothers of walkers used locomotor verbs more frequently than mothers of crawlers. One mother of an 18-month-old was an outlier, circled in yellow, but results were unchanged by excluding this datapoint. (B) Prevalence of specific locomotor verb phrases. “Go” and “come” were spoken by most mothers, but most verbs were idiosyncratic. (C) Variety of locomotor verbs for each mother. Graph shows that mothers of walkers used a greater variety of locomotor verbs than mothers of crawlers.

Altogether, mothers used 34 unique locomotor verb phrases (Figure 1B). Common locomotor verbs were “go” (spoken by all 48 mothers), “come” (47 mothers), and “bring” (30 mothers). But largely, locomotor verbs were idiosyncratic and shared by fewer than half the mothers (e.g., “chase”, “carry”, “crawl”, “step”, “back up”). Mothers of walkers used a greater variety of locomotor verbs than did mothers of crawlers (Figure 1C). Crawlers received M = 4.46 (SD = 1.59) unique verbs per hour, whereas the same-aged walkers heard M = 5.91 (SD = 1.35) unique verbs per hour. Younger and older walkers (M = 6.78, SD = 1.52) heard an equivalent number of unique verbs per hour. The ANOVA confirmed a main effect of group, F(2, 47) = 9.78, p < .001, and pairwise comparisons indicated that crawlers received fewer locomotor verbs than same-aged walkers, p = .027, with no differences between the walking groups3, p = .282.

Infants’ time spent locomoting is associated with more frequent and diverse locomotor verb inputs

Given that walking infants received more locomotor verbs than same-aged crawlers, we next tested whether this group-level difference is accounted for by infants’ real-time locomotion. Consistent with prior work (e.g., Adolph & Tamis-LeMonda, 2014), walking infants spent more time locomoting compared to crawlers. Crawlers were in motion for M = 7.2% of the session (SD = 2.9), compared to 20.4% for the 13-month-old walkers (SD = 7.2), and 19.7% for the 18-month-old walkers (SD = 6.2). Crawlers’ individual locomotor bouts were shorter in duration (M = 3.08 seconds; SD = 1.05) compared to the same-aged walkers (M’s = 3.96 seconds; SD = 0.98). An ANOVA confirmed a main effect of group on infants’ time in motion, F(2, 47) = 26.70, p < .001. Pairwise comparisons indicated that crawlers spent less time in motion than same-aged walkers, p < .001 and 18-month-old walkers, p < .001.

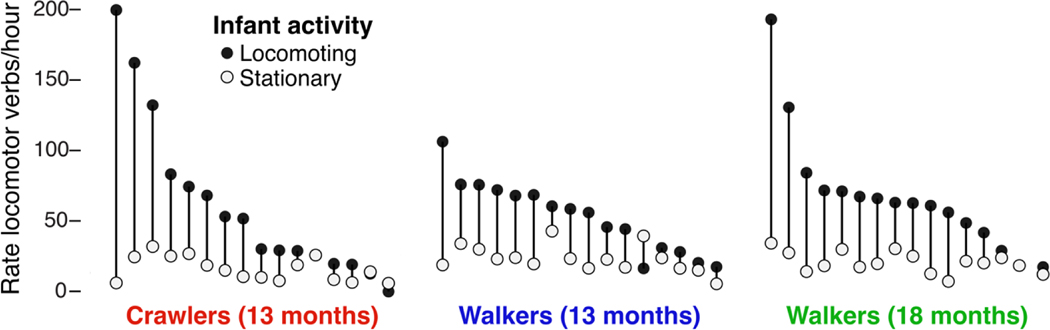

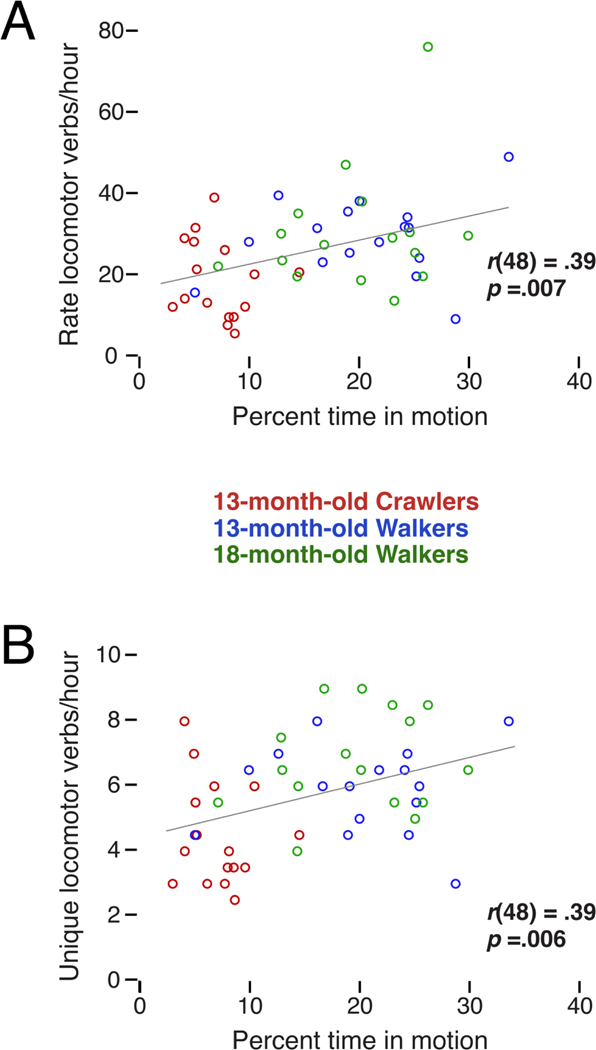

Real-time locomotion was the key catalyst for infants’ locomotor verb exposure. Mothers’ locomotor verbs were dense during periods of infant locomotion (Figure 2). While infants were in motion, they received triple the rate of locomotor verbs per hour (M = 61.06; SD = 43.51) compared to when they were stationary (M = 20.16; SD = 8.97). The ANOVA confirmed a main effect of infant activity, F(1, 45) = 45.89, p < .001. Notably, the three groups did not differ in the density of verbs during locomotion, F(2, 45) = 0.87, p = .425. When the 13-month-old crawlers moved, they heard just as many locomotor verbs per hour (M = 62.16; SD = 57.45) as did the 13- and 18-month-old walkers (Ms = 53.08, 67.94; SDs = 25.54, 43.14, respectively). However, because crawlers spent much less time locomoting across the session, they were ultimately exposed to fewer locomotor verbs than the 13- and 18-month-old walkers. Indeed, across the session, the percent of time that infants spent in motion was correlated with the rate per hour of mothers’ locomotor verbs, (r = .387, p = .007; Figure 3A) and the variety of locomotor verbs, r = .390, p = .006; Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

The rate per hour of mothers’ locomotor verbs when infants were stationary (open circles) and locomoting (solid circles). Comparison of the open and solid circles shows that locomotor verbs were more dense while infants locomoted compared to when infants were stationary. Group comparisons show that when 13-month-old crawlers locomoted, they heard just as many locomotor verbs per hour as the 13- and 18-month-old walkers.

Figure 3.

Mothers’ locomotor verbs and infants’ locomotion. Mothers of 13-month-old crawlers are depicted in red, 13-month-old walkers in blue, and 18-month-old walkers in green. (A) The percent of time that infants spent in motion was correlated with the rate per hour of mothers’ locomotor verbs. (B) The percent of time that infants spent in motion was correlated with the number of unique locomotor verbs mothers used.

We further tested whether infant actions elicit verb input by testing the temporal ordering of infant and caregiver behaviors. We assessed whether correspondences between infant locomotion and caregiver verb resulted from caregivers’ prompting (e.g., caregiver says, “come here” and then infant locomotes) or commenting on locomotion that was already underway (e.g., infant locomotes and caregiver says, “are you chasing him?”). For the majority of verb-locomotion correspondences, the infant had begun locomoting prior to the verb utterance (M = 80.00%; SD = 18.67), and there were no differences among groups (Ms = 76.91%, 80.82%, 82.22% for crawlers, 13-month-old walkers, and 18-month-old walkers; SDs = 28.23, 11.53, 12.94); F(2, 47) = 0.34, p = .715. The ordering of behaviors—from infant movement to mother input—further supports the hypothesized cascade, with infants’ actions spurring verb input.

Discussion

The notion that infants’ motor skill attainments facilitate learning in other domains has deep roots in psychology (Gibson, 1988; Piaget, 1954). And indeed, studies reveal connections among infants’ motor skill attainments and progress in other abilities that emerge weeks, months, or even years later. For example, the onset of walking is followed by accelerated vocabulary growth (He, Walle, & Campos, 2015; Walle & Campos, 2014; West, Leezebaum, Northrup, & Iverson, 2019). But which mechanisms explain connections between infants’ motor skills and learning opportunities? Our findings offer a model system to understand motor-language cascades: Infants’ developmental skill level (whether they can walk) guides their in-the-moment motor behavior (how much time they spend in motion), which in turn shapes their opportunities to learn words (here, locomotor verbs). Specifically, mothers directed twice as many locomotor verbs to walkers compared to same-aged crawlers. And in real time, mothers’ use of locomotor verbs was dense when infants were locomoting, and sparse when infants were stationary. Consequently, infants who spent more time in motion received more locomotor verbs compared to infants who moved less frequently.

The observed verb-action correspondence offers insights into verb learning. Researchers often puzzle over how infants overcome the “word mapping” challenge—how infants connect a word to its referent despite near-infinite possible alternatives. Theories of word mapping are overwhelmingly predicated on noun learning (Wojcik, Zettersten & Benitez, 2021), and propose that ostensive visual cues—moments when the referent is visually differentiated from the rest of the scene—facilitate word mapping (e.g., caregiver points to a cup while saying “cup”). However, mapping verbs to actions poses unique challenges compared to mapping nouns to objects, and learning mechanisms likely differ (e.g., Hirsh-Pasek & Golinkoff, 2010). Whereas nouns refer to concrete objects which are visually stable over time, verbs refer to fleeting events. Infants’ own experience performing the target action—at the precise moment they hear the verb—may spotlight the verb meaning more so than passively seeing the action performed by others. Infants may not see the referent action that they perform (e.g., infants almost never look at their own legs while they locomote), but nevertheless they receive rich proprioceptive, tactile, and visual information from movements (Kretch, Franchak & Adoph, 2014). In the case of verb learning, performing the action may be more salient than seeing the action. Indeed, congenitally blind people learn action verbs despite never seeing the action performed (e.g., Bedny, Caramazza, Pascual-Leone & Saxe, 2012).

The density of mothers’ locomotor verbs during infant locomotion suggests that mothers repeat locomotor verbs in succession. In fact, analyses of mothers’ verbs showed that mothers often restated verbs in quick sequences (e.g., one mother repeated the word “go” 18 times in under two minutes). Verb repetitions likely optimize learning. Prior experimental work shows that infants are more likely to learn words that are repeated in rapid succession, compared to isolated instances of the word dispersed over time (Schwab & Lew-Williams, 2016).

Moreover, repetitions of utterances that contain related but distinct verbs may draw infants’ attention to the critical distinction. That is, linguistic contrasts may support verb learning (e.g., Au & Markman, 1987). For example, “crawl”, “walk”, “follow”, and “back up” all refer to locomotion. But, “walk” and “crawl” refer to the manner of the action (i.e., how the locomotion is performed), and “follow” and “back up” refer to the path of the locomotion (e.g., Talmy, 1985). Exposure to related, but contrasting, verbs in succession—and in the context of the infants’ own action—may illuminate both the shared features of the actions and the critical distinctions among them. Such linguistic contrasts certainly characterized mothers’ verb input in our data. Although our criteria for the category “locomotor verbs” was deliberately narrow (actions that involve taking steps to move one’s body through space), mothers used thirty-four unique locomotor verb phrases. Such linguistic contrasts support noun and adjective learning (e.g., Au & Laframboise, 1990; Au & Markman, 1987), and likewise may facilitate learning verb categories.

Of course, locomotor verbs constitute a small slice of the thousands of words infants are exposed to each day (e.g., Custode & Tamis-LeMonda, 2020). And so, changes in the frequency of caregivers’ locomotor verb use are unlikely to fully account for broader developmental trends in infants’ vocabulary growth (e.g., the trajectories of vocabulary growth reported by: He, et al., 2015; Walle & Campos, 2014; West, et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the connection between infant locomotion and caregivers’ locomotor verbs offers critical insight into processes of developmental cascades. Over time, as infants’ motor actions become increasingly sophisticated and frequent, the language inputs they elicit may change in kind. Infants develop a tremendous repertoire of motor actions and play behaviors—they climb on furniture, ride tricycles, open containers, use utensils to scoop food, and chase pets around the house. Each action that infants master likely gives rise to new opportunities to hear—and potentially learn—the relevant verbs precisely as infants perform the action. The co-developing coordination between infant action and caregiver language input may be a critical component of early word learning.

Research Highlights.

Infants’ motor skills guide their in-the-moment behaviors, which in turn shape the language they receive from caregivers.

Mothers directed more frequent and diverse verbs that referenced locomotion (e.g., “come”, “go”, “bring”) to walking infants compared to same-aged crawling infants.

Mothers’ locomotor verbs were temporally dense when infants locomoted and sparse when infants were stationary, regardless of whether infants could walk or only crawl.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the LEGO Foundation to Catherine S. Tamis-LeMonda and Karen E. Adolph and by a postdoctoral training grant from the National Institute of Health to Kelsey L. West (F32 DC017903). Portions of this work were presented at the Society for Research in Child Development in April 2021 and the International Congress of Infant Studies in July 2022.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

We took several steps to ensure that variation in recording time did not influence the pattern of results. First, variables of interest did not differ during the first versus second recorded hour among infants with longer recording durations. Second, the pattern of results was unchanged by limiting our data to behaviors collected during the first recorded hour. Thus, we retained the full data available and computed variables as rates per hour to account for variation in recording time.

Data from the 18-month-old group included an outlier: One mother used 76 locomotor verbs per hour. The pattern of significant results was unchanged when the outlier was excluded from analyses.

Beyond walking status, infants’ overall locomotor experience (the elapsed time since they had begun crawling) also related to the variety of locomotor verbs that mothers directed to their infants, r = .40, p = .005. Thus, infants with more experience locomoting were exposed to a greater variety of locomotor verbs.

References

- Adolph KE, Cole WG, Komati M, Garciaguirre JS, Badaly D, Lingeman JM, . . . Sotsky RB (2012). How do you learn to walk? Thousands of steps and dozens of falls per day. Psychological Science, 23, 1387–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolph KE, & Tamis-LeMonda CS (2014). The costs and benefits of development: The transition from crawling to walking. Child Development Perspectives, 8, 187–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au TKF, & Laframboise DE (1990). Acquiring color names via linguistic contrast: The influence of contrasting terms. Child Development, 61(6), 1808–1823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au TKF, & Markman EM (1987). Acquiring word meanings via linguistic contrast. Cognitive Development, 2(3), 217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Bedny M, Caramazza A, Pascual-Leone A, & Saxe R. (2012). Typical neural representations of action verbs develop without vision. Cerebral cortex, 22(2), 286–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos JJ, Anderson DI, Barbu-Roth MA, Hubbard EM, Hertenstein MJ, & Witherington DC (2000). Travel broadens the mind. Infancy, 1, 149–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custode SA, & Tamis-LeMonda C. (2020). Cracking the code: Social and contextual cues to language input in the home environment. Infancy, 25, 809–826. doi: 10.1111/infa.12361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey S, & Bergelson E. (2022). Talking to talkers: Infants’ talk status, but not their gender, is related to language input. Child Development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentner D. (2006). Why verbs are hard to learn. In Hirsh-Pasek K. & Golinkoff RM (Eds.), Action meets world: How children learn verbs (Vol. 1, pp. 544–564). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson EJ (1988). Exploratory behavior in the development of perceiving, acting, and the acquiring of knowledge. Annual Review of Psychology, 39, 1–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.39.020188.000245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gleitman LR, & Gleitman H. (1992). A picture is worth a thousand words, but that’s the problem: The role of syntax in vocabulary acquisition. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- He M, Walle EA, & Campos JJ (2015). A cross-national investigation of the relationship between infant walking and language development. Infancy, 20, 283–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh-Pasek K, & Golinkoff RM (2010). Action meets word: How children learn verbs. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karasik LB, Tamis-LeMonda CS, & Adolph KE (2014). Crawling and walking infants elicit different verbal responses from mothers. Developmental Science, 17, 388–395. doi: 10.1111/desc.12129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretch KS, Franchak JM, & Adolph KE (2014). Crawling and walking infants see the world differently. Child development, 85(4), 1503–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Zhang Y, & Yu C. (2019). Why some verbs are harder to learn than others: A micro-level analysis of everyday learning contexts for early verb learning. Paper presented at the 42nd Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society in Toronto, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Nakao K, & Treas J. (1994). Updating occupational prestige and socioeconomic scores: How the new measures measure up. Sociological methodology, 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira AF, Smith LB, & Yu C. (2013). A bottom-up view of toddler word learning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 21, 178–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Schatz JL, Suarez-Rivera C, Kaplan BE, & Tamis-LeMonda CS (2022). Infants’ object interactions are long and complex during everyday joint engagement. Developmental Science, e13239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JL, & Iverson JM (2021). Cascades in action: How the transition to walking shapes caregiver communication during everyday interactions. Developmental Psychology, 58, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab JF, & Lew-Williams C. (2016). Repetition across successive sentences facilitates young children’s word learning. Developmental psychology, 52, 879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LB, Yu C, & Pereira AF (2011). Not your mother’s view: The dynamics of toddler visual experience. Developmental Science, 14, 9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soska KC, Adolph KE, & Johnson SP (2010). Systems in development: Motor skill acquisition facilitates three-dimensional object completion. Developmental Psychology, 46, 129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmy L. (1985). Lexicalization patterns: Semantic structure in lexical forms. Language typology and syntactic description, 3(99), 36–149. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS, Kuchirko Y, & Tafuro L. (2013). From action to interaction: Infant object exploration and mothers’ contingent responsiveness. IEEE Transactions on Autonomous Mental Development, 5, 202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Walle EA (2016). Infant social development across the transition from crawling to walking. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walle EA, & Campos JJ (2014). Infant language development is related to the acquisition of walking. Developmental Psychology, 50, 336–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West KL, Fletcher KK, Adolph KE, & Tamis-LeMonda CS (2022). Mothers talk about infants’ actions: How verbs correspond to infants’ real-time behavior. Developmental Psychology 58, 405–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West KL, & Iverson JM (2017). Language learning is hands-on: Exploring links between infants’ object manipulation and verbal input. Cognitive Development, 43, 190–200. [Google Scholar]

- West KL, & Iverson JM (2021). Communication changes when infants begin to walk. Developmental science, 24, e13102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West KL, Leezebaum NB, Northrup JB, & Iverson JM (2019). The relation between walking and language in infant siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. Child Development, 90, 356–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik EH, Zettersten M, & Benitez VL (2022). The map trap: Why and how word learning research should move beyond mapping. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, e1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C, & Smith LB (2012). Embodied attention and word learning by toddlers. Cognition, 125, 244–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]