Abstract

Background

Some patients with warm autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (wAIHA) or Evans syndrome (ES) have no response to glucocorticoid or relapse. Recent studies found that sirolimus was effective in autoimmune cytopenia with a low relapse rate.

Methods

Data from patients with refractory/relapsed wAIHA and ES in Peking Union Medical College Hospital from July 2016 to May 2022 who had been treated with sirolimus for at least 6 months and followed up for at least 12 months were collected retrospectively. Baseline and follow-up clinical data were recorded and the rate of complete response (CR), partial response (PR) at different time points, adverse events, relapse, outcomes, and factors that may affect the efficacy and relapse were analyzed.

Results

There were 44 patients enrolled, with 9 (20.5%) males and a median age of 44 (range: 18–86) years. 37 (84.1%) patients were diagnosed as wAIHA, and 7 (15.9%) as ES. Patients were treated with sirolimus for a median of 23 (range: 6–80) months and followed up for a median of 25 (range: 12–80) months. 35 (79.5%) patients responded to sirolimus, and 25 (56.8%) patients achieved an optimal response of CR. Mucositis (11.4%), infection (9.1%), and alanine aminotransferase elevation (9.1%) were the most common adverse events. 5/35 patients (14.3%) relapsed at a median of 19 (range: 15–50) months. Patients with a higher sirolimus plasma trough concentration had a higher overall response (OR) and CR rate (p = 0.009, 0.011, respectively). At the time of enrolment, patients were divided into two subgroups that relapsed or refractory to glucocorticoid, and the former had poorer relapse-free survival (p = 0.032) than the other group.

Conclusion

Sirolimus is effective for patients with primary refractory/relapsed wAIHA and ES, with a low relapse rate and mild side effects. Patients with a higher sirolimus plasma trough concentration had a higher OR and CR rate, and patients who relapsed to glucocorticoid treatment had poorer relapse-free survival than those who were refractory.

Keywords: Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, Evans syndrome, sirolimus, refractory/relapsed, efficacy

1. Introduction

Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (AIHA) is characterized by an increase in the destruction of autologous erythrocytes by autoantibodies, with or without complement activation [1]. Based on the temperature reactivity of the red blood cell autoantibodies, AIHA is classified into warm AIHA (wAIHA), cold AIHA (cAIHA), and mixed-type AIHA [2]. Evans syndrome (ES) is defined as the simultaneous or sequential development of wAIHA with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) and/or immune neutropenia [3,4]. AIHA and Evans syndrome are classified as primary and secondary based on whether an etiologic disorder is present [4].

Glucocorticoid monotherapy or in combination with rituximab in patients with severe disease was the standard first-line therapy for primary wAIHA in adults [4]. Glucocorticoid monotherapy or in combination with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in patients with low platelet counts was the standard first-line therapy for ES [5,6]. As a first-line therapy, glucocorticoid can induce overall response (OR) in about 80% of patients and complete response (CR) in about 60% of patients with AIHA [4,7]. However, several studies found that the median time to relapse was approximately 2 to 3 years, and even earlier in patients who tapered and stopped glucocorticoid in less than 6 months [8,9]. Rituximab, recommended in combination with glucocorticoid or as second-line therapy, was reported to have an OR rate of 70%, but a relapse rate of 50% with a median time to next treatment of 16.5 months [10]. Due to its high cost and transient response, IVIG is rarely used in the clinic for wAIHA, and Canadian guidelines also do not recommend its use in patients with AIHA [11,12]. Similarly, the First International Consensus Meeting only recommended IVIG as a rescue therapy for emergency situations [4]. Other therapies like cyclosporine A (CsA), cyclophosphamide (CTX), azathioprine, etc., have limited response in very small patient cohorts [13,14].

Sirolimus is a macrolide antibiotic produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus, which can bind to mammalian targets of rapamycin (mTOR) with high affinity and inhibit mTOR pathway [15,16]. Sirolimus, which acts through different mechanisms to cyclosporine, has been used to prevent graft rejection in solid organ transplantation[16] and treat a variety of autoimmune diseases [17,18]. In mouse models, sirolimus reduced Th1 inflammatory cytokines, stimulated expansion of regulatory T cells, and eliminated effector CD8+ T cells [19]. Some case reports demonstrated that sirolimus was effective in both children and adults with multi-resistant AIHA [20,21]. Besides, sirolimus had an OR rate of approximately 70% to 90% in autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) and autoimmune cytopenia with a low relapse rate [22,23]. However, these reports were mainly focused on other immune-related cytopenias other than AIHA/ES with a limited number of AIHA and ES enrolled, and the follow-up time was relatively short. Here we reported a group of patients with primary wAIHA/ES who had been treated with sirolimus as the salvage therapy and followed up regularly in the out clinic. This study had some overlapping subjects with our previous study [23], but we expanded the sample size of AIHA and ES, and evaluated the effect of sirolimus on more haematological parameters to assess the efficacy. In addition, we analyzed the predictive factors to response and relapse, and relapse-free survival.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Peking Union Medical College Hospital (project number: K4223, approved June 2023). As this was a retrospective study, the informed consent was waived.

Data from patients diagnosed as refractory/relapsed wAIHA and ES who had been treated with sirolimus from July 2016 to May 2022 from the Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) were collected respectively. Patients enrolled had to meet the following criteria: (1) ≥ 18 years old; (2) confirmed diagnosis of primary wAIHA, or ES; (3) refractory, or relapsed to at least full dose glucocorticoid (prednisolone 1.0 mg/kg per day for 3 weeks or other corticosteroids with equivalent daily doses) [4,7]; (4) had been treated with sirolimus for at least 6 months if not responded; (5) had been followed-up after sirolimus for at least 12 months; (6) had complete medical data. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) diagnosed as secondary AIHA and ES; (2) newly diagnosed AIHA/ES; (3) in combination with other treatment (except for glucocorticoid tapering and necessary supportive therapy) (4) with anaemia in chronic kidney disease or other types of anaemia, which may influence the assessment of efficacy (5) treated with sirolimus for less than 6 months or followed-up for less than 12 months. Because a certain duration is required for sirolimus to take action, patients who discontinued sirolimus early due to poor compliance, costs, side effects, and other reasons were excluded. Patients with a negative direct antiglobulin test (DAT) were diagnosed with clear evidence of haemolysis or a response to glucocorticoid treatment, and alternative causes of both inherited and acquired haemolysis were ruled out. 15 (34.1%) patients were overlapped with our previous study [23] (no. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, and 20 in the previous study) with a longer follow-up time.

2.2. Treatment regimens

Sirolimus was given at a dose of 1–3 mg/d, and dose adjustment was made if necessary to maintain the serum trough concentration of sirolimus at 4–15 ng/mL during the treatment period. All patients were treated with sirolimus for at least 6 months, and those who had a response continued the treatment for at least 1.5 years and tapered by 0.5 mg every 6 months. For those with decreased haemoglobin levels during tapering, the optimal higher dose was used and maintained for a longer time. Those who did not respond were changed to other medications or supportive therapies. Necessary supportive therapies included transfusion if haemoglobin was < 60 g/L, platelets < 20 × 109/L, or G-CSF (5 μg/kg/d) if neutrophils were less than 0.5 × 109/L.

Clinical data, including sex, age, symptoms, signs, complete blood cell count, serum biochemistry such as liver and kidney functions, ferritin level, laboratory inspection results, and treatment outcome, were collected before and post-therapy. All the adverse events and the disease status were obtained from the medical records or, occasionally, from the telephone interview of the patients and their relatives. The response was assessed after 3, 6, and 12 months of therapy and at the end of follow-up.

2.3. Assessment of response and adverse events

The response of AIHA and ES was defined by the recommendations for AIHA [4] and immune thrombocytopenic purpura from international working group [24]: 1) complete response (CR): normalization of all cytopenia (anaemia and thrombocytopenia); 2) partial response (PR): increase by 20 g/L in haemoglobin, or normalization of haemoglobin with haemolysis; or platelet count ≥ 30 × 109/L and at least 2-fold increase the baseline platelet count and absence of bleeding (only for patients with ES); 3) overall response (OR): achieve CR or PR; 4) no response (NR): failing to achieve CR or PR; 5) relapse: shifting from CR/PR to NR. Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to the Common Toxicity Criteria of the National Cancer Institute, version 5.0.

2.4. Statistical analysis

SPSS (version 25.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistics, and GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.2 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA, www.graphpad.com) was used for the graphs. Copyright licences for both software have been obtained. Continuous data are presented as median (range), and qualitative data are presented as frequencies and percentages. Key laboratory parameters are presented by median (interquartile range (IQR)), and compared by Mann-Whitney test. The average sirolimus plasma trough concentration of the first 6 months after sirolimus for each patient is used in the analysis of predictive factors. Time to relapse was defined as the interval from sirolimus treatment to relapse. The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used to calculate the cumulative response rate and relapse-free survival rate. A binary logistic regression test was used to detect predictive factors. All tests were two-sided analysis. The statistical significance level in this study was p < 0.05.

3. Results

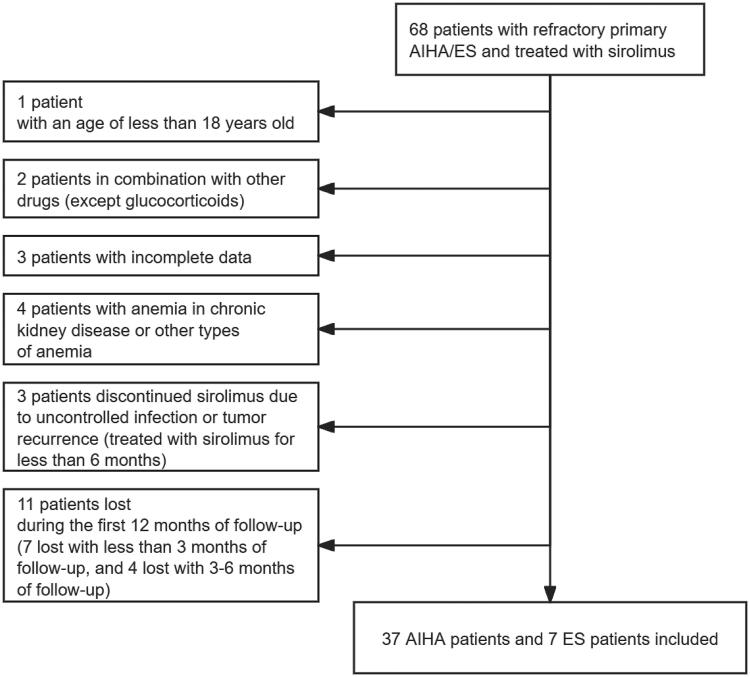

A total of 68 patients with relapsed/refractory primary AIHA/ES were screened. Among them, 24 patients were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The remaining 44 patients all have been treated with sirolimus for at least 6 months and followed up for at least 12 months.

Figure 1.

Study profile.

A total of 68 patients were screened. Among those, 1 patient was excluded with an age of less than 18; 2 in combination with other drugs (except glucocorticoids); 3 with incomplete data; 4 with anaemia in chronic kidney disease or other types of anaemia; 3 discontinued sirolimus due to uncontrolled infection or tumour recurrence (treated with sirolimus for less than 6 months); 11 lost during the first 12 months of follow-up (7 lost with less than 3 months of follow-up, and 4 lost with 3–6 months of follow-up). The remaining 44 patients all have been treated with sirolimus for at least 6 months and followed up for at least 12 months.

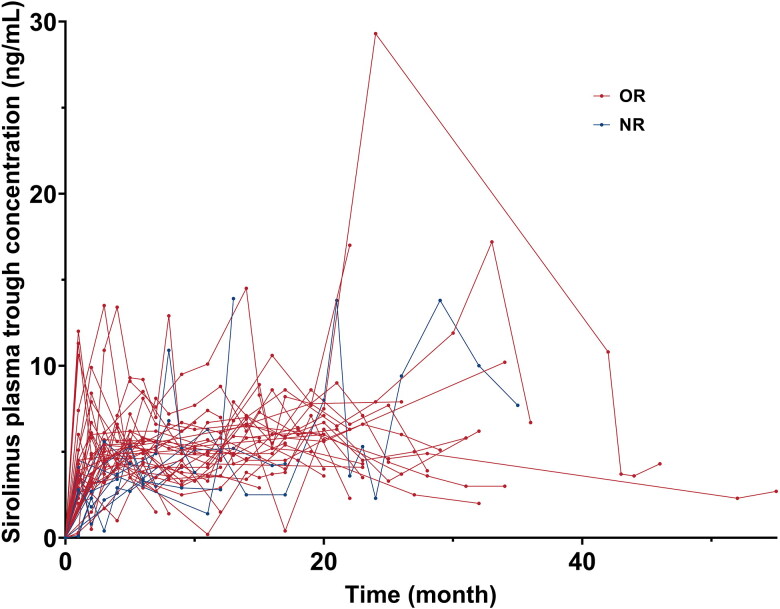

The median age was 44 (range: 18–86) years, with 9 males (20.5%) (Table 1). 37 (84.1%) patients were diagnosed as wAIHA and 7 (15.9%) as ES. The median time from diagnosis to sirolimus treatment was 15 (range: 1–212) months. All patients have been treated with a full dose of glucocorticoids as first-line therapy. Among them, 25 (56.8%) patients were refractory to glucocorticoid treatment, and 19 (43.2%) patients relapsed. Previous therapies like rituximab, cyclosporin A (CsA), cyclophosphamide (CTX), intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and azathioprine were given to some patients as well (Table 1). Considering the previous response to CsA, 6/13 (46.2%) of the patients were refractory to CsA, and 7/13 (53.8%) of the patients were relapsed. 26 (59.1%) patients have experienced two or more lines of previous therapy before sirolimus treatment. 13 (29.5%) patients were treated with glucocorticoids at the beginning of sirolimus treatment. Glucocorticoids were stopped or tapered as scheduled when sirolimus started, and the median time of glucocorticoid tapering was 8 (range: 2–19) weeks. The median sirolimus plasma trough concentration was 4.5 (range: 2.0–8.1) ng/mL, and the intraindividual variability of sirolimus plasma trough concentration was shown in Figure 2. The median duration of treatment with sirolimus was 23 (range: 6–80) months, and the median follow-up time was 25 (range: 12-80) months (Table 1). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between AIHA and ES patients, except that AIHA patients had significantly higher PLT than ES patients (211 (range: 102–414) ×109/L vs. 57 (range: 17–69) ×109/L, p = 3.55 × 10−5).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristics | Total (N = 44) | AIHA (N = 37) | ES (N = 7) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex, No. (%) | 9 (20.5) | 9 (24.3) | 0 (0) | 0.148 |

| Age, y, median (range) | 44 (18–86) | 45 (18–86) | 43 (30–72) | 0.441 |

| Time from diagnosis to sirolimus treatment, m, median (range) | 15 (1–212) | 15 (1–212) | 58 (8–83) | 0.150 |

| Diagnosis, No. (%) | ||||

| wAIHA | 37 (84.1) | – | – | – |

| ES | 7 (15.9) | – | – | – |

| Type of antibody, No. (%) | 0.480 | |||

| Warm (IgG) | 33 (75.0) | 27 (73.0) | 6 (85.7) | |

| Negative | 11 (25.0) | 10 (27.0) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Disease status, No. (%) | 0.104 | |||

| Refractory to glucocorticoid | 25 (56.8) | 23 (62.2) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Relapsed to glucocorticoid | 19 (43.2) | 14 (37.8) | 5 (71.4) | |

| Previous treatment, No. (%) | ||||

| Glucocorticoid | 44 (100) | 37 (100) | 7 (100) | 1.000 |

| Rituximab | 6 (13.6) | 5 (13.5) | 1 (14.3) | 0.975 |

| CsA | 13 (29.5) | 10 (27.0) | 3 (42.9) | 0.405 |

| CTX | 10 (22.7) | 7 (18.9) | 3 (42.9) | 0.171 |

| IVIG | 5 (11.4) | 4 (10.8) | 1 (14.3) | 0.793 |

| Azathioprine | 5 (11.4) | 4 (10.8) | 1 (14.3) | 0.793 |

| Two or more lines of previous therapies | 26 (59.1) | 20 (54.1) | 6 (85.7) | 0.122 |

| Haemoglobin, g/L, median (range) | 85 (30–107) | 85 (30–106) | 83 (44–107) | 0.759 |

| Platelet, ×109/L, median (range) | 189 (17–414) | 211 (102–414) | 57 (17–69) | 3.55 × 10-5 |

| Absolute neutrophil count, ×109/L, median (range) | 2.95 (0.90–12.61) | 2.95 (0.90–8.73) | 3.40 (1.21–12.61) | 0.360 |

| Absolute reticulocyte count, ×109/L, median (range) | 195.2 (75.0–875.2) | 202.0 (75.0–875.0) | 188.4 (111.4–371.6) | 0.656 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L, median (range) | 256 (114–491) | 259 (138–405) | 224 (114–491) | 0.890 |

| Serum total bilirubin, μmol/L, median (range) | 30.1 (8.5–286.6) | 34.5 (8.5–137.3) | 18.7 (12.5–286.6) | 0.285 |

| Serum indirect bilirubin, μmol/L, median (range) | 20.3 (5.7–251.3) | 24.3 (5.7–128.1) | 13.4 (9.0–251.3) | 0.292 |

| Serum ferritin, ng/mL, median (range) | 364 (43–1661) | 419 (43–1661) | 171 (47–600) | 0.188 |

| With glucocorticoid tapering, No. (%) | 13 (29.5) | 13 (35.1) | 0 | 0.065 |

| Duration of glucocorticoid tapering, wks, median (range) | 8 (2–19) | 8 (2–19) | – | – |

| Sirolimus plasma trough concentration, ng/mL, median (range)* | 4.5 (2.0–8.1) | 4.5 (2.0–8.1) | 4.3 (3.5–8.1) | 0.742 |

| Duration of sirolimus treatment, m, median (range) | 23 (6–80) | 23 (6–80) | 23 (6–38) | 0.712 |

| Duration of follow-up, m, median (range) | 25 (12–80) | 26 (12–80) | 23 (12–38) | 0.688 |

wAIHA: warm autoimmune haemolytic anaemia; ES: Evans syndrome; IgG: immunoglobulin G; CsA: cyclosporin A; CTX: cyclophosphamide; IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin.

Based on the average sirolimus plasma trough concentration of the first 6 months after sirolimus of each patient.

Figure 2.

Sirolimus plasma trough concentration in patients with response or no response to sirolimus. A line chart was conducted to assess intraindividual variability of sirolimus plasma trough concentration in each patient. One patient did not have a sirolimus plasma concentration test during the administration of sirolimus.

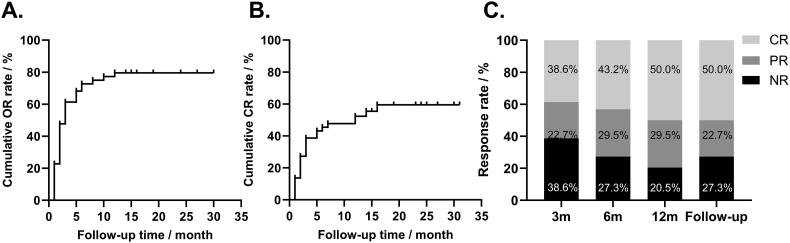

3.1. Response

The response at 3, 6, 12 months, and at the end of follow-up was reported in Table 2. 35 (79.5%) of the 44 patients had a response to sirolimus, and 25 (56.8%) patients achieved an optimal response of CR. The median time to response was 2 (range: 1-12) months, and the median time to optimal response was 3 (range: 1–16) months (Figure 3A and B). The OR rate (ORR) at 3, 6, 12 months, and at the end of follow-up was 61.4%, 72.7%, 79.5%, and 72.7%, with CR rate (CRR) of 38.6%, 43.2%, 50.0%, and 50.0%, respectively (Figure 3C).

Table 2.

Response to sirolimus.

| Response | Total (N = 44) | AIHA (N = 37) | ES (N = 7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3m | CR | 38.6% | 43.2% | 14.3% |

| PR | 22.7% | 13.5% | 71.4% | |

| NR | 38.6% | 43.2% | 14.3% | |

| 6m | CR | 43.2% | 48.6% | 14.3% |

| PR | 29.5% | 18.9% | 85.7% | |

| NR | 27.3% | 32.4% | 0 | |

| 12m | CR | 50.0% | 56.8% | 14.3% |

| PR | 29.5% | 18.9% | 85.7% | |

| NR | 20.5% | 24.3% | 0 | |

| Follow-up | CR | 50.0% | 56.8% | 14.3% |

| PR | 22.7% | 13.5% | 71.4% | |

| NR | 27.3% | 25.0% | 14.3% | |

AIHA: autoimmune haemolytic anaemia; ES: Evans syndrome; N: number; CR: complete response; PR: partial response; NR: no response.

Figure 3.

Cumulative response rate and response rate at 3, 6, 12 months, and at the end of follow-up. A. The cumulative or rate curves. Patients who did not respond to sirolimus were censored at the end of follow-up. B. The cumulative CR rate curves. Patients who did not respond to sirolimus were censored at the end of follow-up. C. The efficacy of sirolimus at 3, 6, 12 months of treatment and at the end of follow-up.

For the whole population, the median haemoglobin level significantly increased from 85 (IQR: 70–94) g/L at baseline to 113 (IQR: 95–126) g/L, 116 (IQR: 96–131) g/L, 120 (IQR: 109–132) g/L, and 120 (IQR: 93–135) g/L at 3, 6, 12 months and at the end of follow-up (all p<0.001, Figure 4A). Meanwhile, the levels of absolute reticulocyte count (ARC), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), serum total bilirubin (Tbil), and serum indirect bilirubin (Ibil) generally decreased during sirolimus treatment in all patients (Figure 4B, C, D, and E). The ARC kept compatible with the baseline level at 3 and 6 months, and significantly decreased at 12 months and at the end of follow-up (128.0 (IQR: 92.0–212.5) ×109/L at 12 months, 117.5 (IQR: 83.0–198.8) ×109/L at the end of follow-up vs. 195.2 (IQR: 125.0–268.1) ×109/L at baseline; p = 0.005, and p<0.001, respectively). The median LDH level kept compatible with the baseline level at 3 and 6 months, significantly decreased at 12 months, and remained nearly normal at the end of follow-up (229 (IQR: 187–260) U/L at 12 months and 220 (IQR: 187–270) U/L at the end of follow-up vs. 256 (IQR: 202–315) U/L at baseline vs., p = 0.006, and 0.036, respectively). The Tbil and Ibil levels were significantly lower than the baseline level at 3 months and remained similar thereafter (17.8 (IQR: 10.7–49.3) μmol/L at 3 months, 20.6 (IQR: 11.6–38.5) μmol/L at 6 months, 15.9 (IQR: 9.5–34.9) μmol/L at 12 months, and 21.5 (IQR: 11.4–39.9) μmol/L at the end of follow-up vs. 30.1 (IQR: 20.8–68.6) μmol/L at baseline, all p<0.001; 11.5 (IQR: 7.4–35.2) μmol/L at 3 months, 12.4 (IQR: 8.2–34.1) μmol/L at 6 months, 10.9 (IQR: 6.0–23.7) μmol/L at 12 months, and 12.6 (IQR: 7.2–21.6) μmol/L at the end of follow-up vs. 20.3 (IQR: 13.4–57.9) μmol/L at baseline, all p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Key laboratory parameter changes at 3, 6, 12 months, and at the end of follow-up. A. The haemoglobin levels at baseline, 3, 6, 12 months of treatment, and at the end of follow-up. The haemoglobin levels at 3, 6, 12 months, and at the end of follow-up were significantly higher than the baseline level (all p <0.001). B. The absolute reticulocyte counts at baseline, 3, 6, 12 months of treatment, and at the end of follow-up. The absolute reticulocyte counts at 12 months and at the end of follow-up were significantly lower than the baseline level (p = 0.005 and p < 0.001, respectively). C. The lactate dehydrogenase levels at baseline, 3, 6, 12 months of treatment, and at the end of follow-up. The lactate dehydrogenase levels at 12 months and at the end of follow-up were significantly lower than the baseline level (p = 0.006 and 0.036, respectively). D. The serum total bilirubin levels at baseline, 3, 6, 12 months, and at the end of follow-up. The serum total bilirubin levels at 3, 6, 12 months, and at the end of follow-up were significantly lower than the baseline (all p <0.001). E. The serum indirect bilirubin levels at baseline, 3, 6, 12 months, and at the end of follow-up. The serum indirect bilirubin levels at 3, 6, 12 months, and at the end of follow-up were significantly lower than the baseline level (all p <0.001). F. The platelet levels at baseline, 3, 6, 12 months of treatment, and at the end of follow-up. The platelet levels at 3 and 12 months were significantly higher than the baseline level (p = 0.037, 0.029, respectively), and there was a trend that the platelet levels at 6 months and at the end of follow-up were higher than the baseline level (p = 0.058, 0.055, respectively). In panels A-E, the horizontal line within each box represented the median, the lower and upper borders of each box represented the 25th and the 75th percentiles, respectively, and the I bars represented the adjusted minimum and maximum range. Dots represented outlier values.

For the 7 patients with ES, the platelet counts increased from 60 (IQR: 36–69) ×109/L at baseline, to 103 (IQR: 57–153) ×109/L at 3 months, 80 (IQR: 72–173) ×109/L at 6 months, 100 (IQR: 76–161) ×109/L at 12 months, and 100 (IQR: 57–168) ×109/L at the end of follow-up (p = 0.037, 0.058, 0.029, 0.055, respectively, Figure 4F).

3.2. Adverse effects (AEs)

The treatment-related AEs that occurred in all 44 patients are listed in Table 3. Mucositis (11.4%), infection (9.1%), and alanine aminotransferase elevation (9.1%) were the most frequently detected AEs. 2.3% (1/44) grade 3 pulmonary infection on National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria was reported (Table 3), and this patient discontinued sirolimus. No other patient had a sirolimus dose reduction or withdrawal because of AEs.

Table 3.

Adverse events during the treatment period.

| AEs | Any grade | Grade 3* |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients with Aes (%) | ||

| Mucositis | 5 (11.4) | 0 |

| Infection | 4 (9.1) | 1 (2.3) |

| Alanine aminotransferase elevation | 4 (9.1) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 2 (4.5) | 0 |

| Edema | 2 (4.5) | 0 |

| Myalgia | 2 (4.5) | 0 |

| Creatinine elevation | 1 (2.3) | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 1 (2.3) | 0 |

| Hyperuricemia | 1 (2.3) | 0 |

| Acne | 1 (2.3) | 0 |

AEs: adverse events.

Adjuvant therapies were used to alleviate adverse effects.

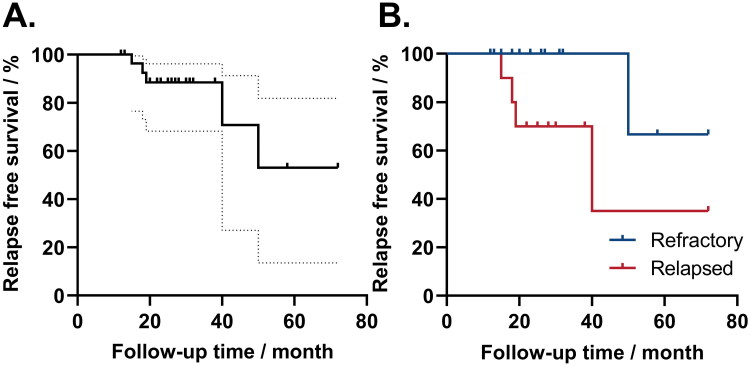

3.3. Relapse, clone evolution, and survival

The median follow-up time was 25 (range: 12–80) months. For patients who achieved PR or CR, 5/35 (14.3%) patients relapsed at a median time of 19 (range: 15–50) months (Figure 5A). Among them, four patients relapsed during tapering: 3 patients responded again after dose increasing, and the other did not respond and was given supportive therapy or other immunosuppressive therapies. One patient relapsed from sirolimus and was treated with sirolimus in combination with mycophenolate mofetil and responded afterward. No patient died during the follow-up period.

Figure 5.

Relapse-free survival of sirolimus treatment. A. The relapse-free survival of 35 patients with response to sirolimus. The solid line represented relapse-free survival during treatment, and the dotted line represented the 95% CI range. B. Relapse-free survival in patients refractory or relapsed. The blue line represented relapse-free survival in refractory patients, and the red line represented relapse-free survival in relapsed patients. Patients who did not relapse were censored at the end of follow-up.

3.4. Factors that may predict response and relapse

Factors that may predict the optimal overall response (OR) rate, complete response (CR) rate, and relapse rate were further analyzed. Age, sex ratio, time from diagnosis to sirolimus treatment, type of disease, refractory/relapsed, baseline haemoglobin, absolute reticulocyte count, previous response to CsA, sirolimus plasma trough concentration, and time to response were selected. In univariate analysis, patients with a higher sirolimus plasma trough concentration had a higher optimal OR rate and CR rate (4.9 (range: 2.9–8.1) ng/mL in OR patients vs. 3.0 (range: 2.0–4.5) ng/mL in non-OR patients, p = 0.009; 5.1 (range: 3.0–8.1) ng/mL in CR patients vs. 3.7 (range: 2.0–8.1) ng/mL in non-CR patients, p = 0.011). Besides, there was a trend that patients who relapsed to glucocorticoid treatment had a higher relapse rate to sirolimus than those who were refractory (relapse vs. non-relapse: 1/19 in refractory patients vs. 4/11 in relapsed patients, p = 0.102). However, only sirolimus plasma trough concentration was found to predict ORR in multivariate analysis (p = 0.028). No other factors were found to predict significantly OR, CR, and relapse rate in either univariate analysis or multivariate analysis (p > 0.05, Table 4). The cumulative relapse rates at 24, 36, and 48 months were 11.6%, 11.6%, and 30.4%, respectively. Patients who relapsed to glucocorticoid treatment had a poorer relapse-free survival than those who were refractory (p = 0.032, Figure 5B). Other factors, such as age, sex ratio, time from diagnosis to sirolimus treatment, type of disease, baseline haemoglobin, absolute reticulocyte count, sirolimus plasma trough concentration, and time to response, had no significant correlation with relapse-free survival.

Table 4.

Factors that may affect or/CR/relapse.

| Characteristics |

P-value |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||

| OR vs. non-OR | Age, years | 0.298 | 0.212 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.292 | 0.250 | |

| Median time from diagnosis to sirolimus treatment, months | 0.465 | 0.161 | |

| Type of diseases (wAIHA vs. ES) | 0.999 | 0.446 | |

| Disease status (refractory vs. relapsed) | 0.932 | 0.669 | |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 0.980 | 0.686 | |

| Absolute reticulocyte count, ×109/L | 0.075 | 0.217 | |

| Sirolimus plasma trough concentration, ng/mL* | 0.009 | 0.028 | |

| Previous response to CsA (refractory vs. relapsed) | 0.186 | – | |

| CR vs. non-CR | Age, years | 0.135 | 0.983 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.405 | 0.716 | |

| Median time from diagnosis to sirolimus treatment, months | 0.209 | 0.726 | |

| Type of diseases (wAIHA vs. ES) | 0.118 | 0.982 | |

| Disease status (refractory vs. relapsed) | 0.900 | 0.716 | |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 0.065 | 0.994 | |

| Absolute reticulocyte count, ×109/L | 0.190 | 0.784 | |

| Sirolimus plasma trough concentration, ng/mLa | 0.011 | 0.983 | |

| Previous response to CsA (refractory vs. relapsed) | 0.322 | – | |

| Relapse vs. non-relapse |

Age, years | 0.179 | 0.645 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.855 | 0.880 | |

| Median time from diagnosis to sirolimus treatment, months | 0.584 | 0.091 | |

| Type of diseases (wAIHA vs. ES) | 1.000 | 0.301 | |

| Disease status (refractory vs. relapsed) | 0.102 | 0.998 | |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 0.344 | 0.763 | |

| Absolute reticulocyte count, ×109/L | 0.381 | 0.250 | |

| Time to response | 0.914 | 0.753 | |

OR: overall response; CR: complete response; wAIHA: warm autoimmune haemolytic anaemia; ES: Evans syndrome; CsA: cyclosporine A.

Based on the average sirolimus plasma trough concentration of the first 6 months after sirolimus for each patient.

4. Discussion

Although steroids, rituximab, and intravenous immunoglobin (IVIG) have achieved a high response rate in primary wAIHA/ES, relapse and nonresponse to such treatments in the later course are common [9,13,14,25]. In addition, relapse/refractory patients often suffer from various severe side effects caused by repetitive steroids or rituximab [7,26,27]. With the ability to inhibit the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and regulate T cell proliferation, sirolimus was shown effective in autoimmune-related diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Castleman disease, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS), pure red cell aplasia (PRCA), immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), AIHA, ES, etc [17,28–34]. Recently, our group demonstrated that sirolimus had satisfactory efficacy and safety in autoimmune cytopenia [23]. However, since wAIHA and ES are relatively rare compared with other immune-related diseases, such as ITP, evidence for the efficacy of sirolimus in refractory primary AIHA and ES is limited (Table 5), and no study is available so far specifically for wAIHA/ES with a relatively larger sample size and longer follow-up time. With 44 refractory/relapsed adult patients, our study is the study with the largest AIHA cohort to address this issue so far.

Table 5.

Previous studies about sirolimus in patients with refractory primary AIHA/ES.

| Reference | Disease | No. of patients | Period of follow-up | Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jasinski et al. [22] | ES | 5 | 2.25 (range: 1–6) years* | CR 2, PR 2 |

| Bride et al. [35] | AIHA | 2 | 1 and 4 years | CR 1, PR 1 |

| ES | 8 | 15 weeks-2 years | CR 4, PR 2 | |

| Miano et al. [31] | AIHA | 4 | 3.46 years* | CR |

| Miano et al. [20] | AIHA | 3 | 9, 31, 42 months | CR |

| Li et al. [23] | AIHA | 14 | 18(range: 10–40) months* | CR 57.1%, OR 85.7% |

| ES | 12 | CR 25.0%, OR 33.3% | ||

| Williams et al. [21] | AIHA | 2 | 14 and 16 months | CR |

AIHA: autoimmune haemolytic anaemia; ES: Evans syndrome; CR: complete response; PR: partial response; OR: overall response.

Follow-up time for all patients included in the study.

Our data showed that 35 (79.5%) patients achieved an optimal response of OR and 25 (56.8%) patients achieved an optimal response of CR during sirolimus treatment. The median time to response was 2 months, and the median time to optimal response was 3 months at a median follow-up time of 25 months. Our findings were consistent with previous studies. Our team’s previous research [23] reported that 38 (84.4%) of 45 patients with autoimmune cytopenia responded to sirolimus, and 28 (62.2%) achieved a complete response. Bride et al. [35] demonstrated that among eight patients with ES and two with AIHA, eight patients responded to sirolimus and five had an optimal response of CR. Even though their study was conducted prior to the publishing of international consensus for response evaluation criteria, their response assessment criteria were similar to ours.

We found that patients who responded to sirolimus were mainly CR, in addition, they had not only an increase of haemoglobin, but also a significant normalization of haemolysis-related parameters, like absolute reticulocyte count and bilirubin. This is important, because achieving CR can greatly improve the quality of life and the normalization of the lab tests gives patients the confidence of going back to normal life. All these improvements were achieved with sirolimus monotherapy, which is relatively cheap with minor side effects. Previous reports suggested that although being a benign disease, patients with ITP had an even worse quality of life compared with those with haematologic malignancies [36,37]. wAIHA/ES had similar situations. The impaired quality of life comes from the repetitive relapse, side effects from steroids and other second-line therapies, and high long-term economic burden. Our findings were also consistent with the previous reports. Williams et al. [21] observed a decrease in reticulocyte and total bilirubin levels in 2 patients with refractory wAIHA. Bride et al. [35] reported a decreased trend of reticulocytes in both ALPS and non-ALPS patients with autoimmune cytopenia. Besides, our study found that in patients with Evans syndrome, the platelet level significantly increased at 3 and 12 months, and there was also an increased trend at 6 months and at the end of follow-up. Miano et al. [38] reported that sirolimus induced an ORR of 68% in 19 patients with primary ITP and autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome-related syndrome-ITP. Patients treated with sirolimus even had a higher platelet level than those with cyclosporine at 2 and 3 months [39]. Such evidence suggests that sirolimus may increase platelet levels in ES patients to induce complete remission. Since ES is even rarer than AIHA, we only included 7 patients, which may cause bias due to the small sample size.

Adverse events of sirolimus in our study were mild and controllable. Mucositis (11.4%) was the most detected AE, which was similar to the previous studies [35]. Infection was also notable. One grade 3 pulmonary infection defined by National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria was observed. Studies of sirolimus in refractory/relapse PRCA and chronic ITP showed that about 10% of patients experienced infection during treatment [39,40]. Our study also observed that 9.1% of patients had an infection during treatment. However, previous studies reported that the immune function of cells was not affected in most patients treated with sirolimus [35]. Because most patients were on glucocorticoid tapering or had recently experienced second-line immunotherapy failure when sirolimus started, they were more likely to develop opportunistic infections. Even though, such findings indicated that refractory/relapsed patients treated with sirolimus should be monitored for potential infections.

At the end of follow-up, 14.3% of patients relapsed, and the cumulative relapse rates at 24, 36, and 48 months were 11.6%, 11.6%, and 30.4%, respectively. Although the follow-up time was not as long as glucocorticoids, sirolimus seemed to have a lower relapse rate in the follow-up period. Interestingly, those who relapsed from glucocorticoid had poorer relapse-free survival (p = 0.032) than those who were refractory. Huang et al. [40] found a similar trend in relapse-free survival in patients with aPRCA, although no significant difference. Further studies with a larger sample size and a longer follow-up time are needed to verify this finding.

No significant predictive factors were found in previous studies of sirolimus either in refractory/relapsed autoimmune cytopenia or in PRCA by our previous studies [23,40]. In our study, patients with a higher sirolimus plasma trough concentration had a higher optimal OR and CR rate. This finding can be verified by the report that lower sirolimus plasma concentration (< 5 ng/mL) was associated with efficacy failure in the transplant population [41]. However, sirolimus has a relatively narrow window of concentration between being effective and toxic, and high sirolimus plasma concentration (> 15 ng/mL) was associated with adverse drug reactions [41,42]. Thus, monitoring sirolimus plasma concentration and trying to maintain it within the target trough concentration may improve the optimal efficacy.

There were also some limitations in our study. This was a retrospective study with a small sample size. Some patients were lost to follow-up, and patients with incomplete data were excluded, which may contribute to the bias of results. Meanwhile, due to the rarity of AIHA and ES, patients’ enrolment took a relatively long period, so there may be some difference in the supportive therapies between patients enrolled earlier or later. Only seven patients with ES enrolled made the efficacy of sirolimus on the platelet count uncertain. Even so, with a relatively large number of patients so far and a relatively longer observation time, we demonstrated that sirolimus may act as a salvage therapy for AIHA with a high response rate, mild side effects, and low relapse rate.

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by funding from National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-D-002, 2022-PUMCH-C-026, 2022-PUMCH-B-046), National Natural Science Foundation (82370121), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (2023): (7232109), and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS 2021-I2M-1-003).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures followed were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Peking Union Medical College Hospital (project number: K4223), and were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Consent for publication

This retrospective study involved the analysis of existing data and records; all detailed information of research participants has been de-identified in our article.

Author contributions

Zhuxin Zhang: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Qinglin Hu: Data curation; Investigation.

Chen Yang: Conceptualization; Resources.

Miao Chen: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Bing Han: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Resources; Supervision; Validation.

Disclosure statement

The funders played no roles in the study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, the writing of the report, and the decision to submit the article for publication. All authors have no financial or non-financial conflicts to disclose in this study.

Data availability statement

The datasets are not publicly available due to personal data protection reasons but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Barcellini W. New insights in the pathogenesis of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Transfus Med Hemother. 2015;42(5):1–11. doi: 10.1159/000439002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bass GF, Tuscano ET, Tuscano JM.. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(4-5):560–564. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans RS, Takahashi K, Duane RT, et al. Primary thrombocytopenic purpura and acquired hemolytic anemia: evidence for a common etiology. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1951;87(1):48–65. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1951.03810010058005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jager U, Barcellini W, Broome CM, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in adults: recommendations from the first international consensus meeting. Blood Rev. 2020;41:100648. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2019.100648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norton A, Roberts I.. Management of Evans syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2006;132(2):125–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Audia S, Grienay N, Mounier M, et al. Evans’ syndrome: from diagnosis to treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9(12):3851. doi: 10.3390/jcm9123851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill QA, Stamps R, Massey E, et al. The diagnosis and management of primary autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2017;176(3):395–411. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dussadee K, Taka O, Thedsawad A, et al. Incidence and risk factors of relapses in idiopathic autoimmune hemolytic anemia. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93(Suppl 1):S165–S170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birgens H, Frederiksen H, Hasselbalch HC, et al. A phase III randomized trial comparing glucocorticoid monotherapy versus glucocorticoid and rituximab in patients with autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2013;163(3):393–399. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maung SW, Leahy M, O’Leary HM, et al. A multi-centre retrospective study of rituximab use in the treatment of relapsed or resistant warm autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2013;163(1):118–122. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flores G, Cunningham-Rundles C, Newland AC, et al. Efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of autoimmune hemolytic anemia: results in 73 patients. Am J Hematol. 1993;44(4):237–242. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830440404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson D, Ali K, Blanchette V, et al. Guidelines on the use of intravenous immune globulin for hematologic conditions. Transfus Med Rev. 2007;21(2 Suppl 1):S9–S56. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barcellini W, Fattizzo B, Zaninoni A, et al. Clinical heterogeneity and predictors of outcome in primary autoimmune hemolytic anemia: a GIMEMA study of 308 patients. Blood. 2014;124(19):2930–2936. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-583021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roumier M, Loustau V, Guillaud C, et al. Characteristics and outcome of warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia in adults: new insights based on a single-center experience with 60 patients. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(9):E150–E155. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martel RR, Klicius J, Galet S.. Inhibition of the immune response by rapamycin, a new antifungal antibiotic. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1977;55(1):48–51. doi: 10.1139/y77-007%M.843990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sehgal SN. Sirolimus: its discovery, biological properties, and mechanism of action. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(3 Suppl):7S–14S. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai Z-W, Kelly R, Winans T, et al. Sirolimus in patients with clinically active systemic lupus erythematosus resistant to, or intolerant of, conventional medications: a single-arm, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1186–1196. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30485-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu C, Wang Q, Xu D, et al. Sirolimus for patients with connective tissue disease-related refractory thrombocytopenia: a single-arm, open-label clinical trial. Rheumatology. 2021;60(6):2629–2634. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng X, Lin Z, Sun W, et al. Rapamycin is highly effective in murine models of immune-mediated bone marrow failure. Haematologica. 2017;102(10):1691–1703. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.163675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miano M, Calvillo M, Palmisani E, et al. Sirolimus for the treatment of multi-resistant autoimmune haemolytic anaemia in children. Br J Haematol. 2014;167(4):571–574. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams O, Bhat R, Badawy SM.. Sirolimus for treatment of refractory primary warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia in children. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2020;83:102427. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2020.102427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jasinski S, Weinblatt ME, Glasser CL.. Sirolimus as an effective agent in the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) and evans syndrome (ES): a single institution’s experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39(6):420–424. doi: 10.1097/mph.0000000000000818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Ji J, Du Y, et al. Sirolimus is effective for primary relapsed/refractory autoimmune cytopenia: a multicenter study. Exp Hematol. 2020;89:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, et al. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood. 2009;113(11):2386–2393. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-162503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zecca M, Nobili B, Ramenghi U, et al. Rituximab for the treatment of refractory autoimmune hemolytic anemia in children. Blood. 2003;101(10):3857–3861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rizzoli R, Adachi JD, Cooper C, et al. Management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2012;91(4):225–243. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9630-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gürcan HM, Keskin DB, Stern JNH, et al. A review of the current use of rituximab in autoimmune diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9(1):10–25. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teachey DT, Greiner R, Seif A, et al. Treatment with sirolimus results in complete responses in patients with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2009;145(1):101–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07595.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bayram E, Pehlivan UA, Fajgenbaum DC, et al. Refractory idiopathic multicentric castleman disease responsive to sirolimus therapy. Am J Hematol. 2023;98(2):361–364. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Long Z, Yu F, Du Y, et al. Successful treatment of refractory/relapsed acquired pure red cell aplasia with sirolimus. Ann Hematol. 2018;97(11):2047–2054. doi: 10.1007/s00277-018-3431-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miano M, Scalzone M, Perri K, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus as second or further line treatment in children with chronic refractory primitive or secondary autoimmune cytopenias: a single centre experience. Br J Haematol. 2016;172(4):524–534. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foroncewicz B, Mucha K, Paczek L, et al. Efficacy of rapamycin in patient with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Transpl Int. 2005;18(3):366–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2004.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cejka D, Hayer S, Niederreiter B, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling is crucial for joint destruction in experimental arthritis and is activated in osteoclasts from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(8):2294–2302. doi: 10.1002/art.27504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng Y, Xiao Y, Yan H, et al. Sirolimus as rescue therapy for refractory/relapsed immune thrombocytopenia: results of a single-center, prospective, single-arm study. Front Med. 2020;7:110. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bride KL, Vincent T, Smith-Whitley K, et al. Sirolimus is effective in relapsed/refractory autoimmune cytopenias: results of a prospective multi-institutional trial. Blood. 2016;127(1):17–28. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-657981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMillan R, Bussel JB, George JN, et al. Self-reported health-related quality of life in adults with chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol. 2008;83(2):150–154. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cooper N, Kruse A, Kruse C, et al. Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) world impact survey (I-WISh): impact of ITP on health-related quality of life. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(2):199–207. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miano M, Rotulo GA, Palmisani E, et al. Sirolimus as a rescue therapy in children with immune thrombocytopenia refractory to mycophenolate mofetil. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(7):E175–E177. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mousavi-Hasanzadeh M, Bagheri B, Mehrabi S, et al. Sirolimus versus cyclosporine for the treatment of pediatric chronic immune thrombocytopenia: a randomized blinded trial. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88:106895. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang Y, Chen M, Yang C, et al. Sirolimus is effective for refractory/relapsed/intolerant acquired pure red cell aplasia: results of a prospective single-institutional trial. Leukemia. 2022;36(5):1351–1360. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01532-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kahan BD, Napoli KL, Kelly PA, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of sirolimus: correlations with efficacy and toxicity. Clin Transplant. 2000;14(2):97–109. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2000.140201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kahan BD, Podbielski J, Napoli KL, et al. Immunosuppressive effects and safety of a sirolimus/cyclosporine combination regimen for renal transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;66(8):1040–1046. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199810270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets are not publicly available due to personal data protection reasons but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.