ABSTRACT

Zika virus (ZIKV) is now in a post-pandemic period, for which the potential for re-emergence and future spread is unknown. Adding to this uncertainty is the unique capacity of ZIKV to directly transmit between humans via sexual transmission. Recently, we demonstrated that direct transmission of ZIKV between vertebrate hosts leads to rapid adaptation resulting in enhanced virulence in mice and the emergence of three amino acid substitutions (NS2A-A117V, NS2A-A117T, and NS4A-E19G) shared among all vertebrate-passaged lineages. Here, we further characterized these host-adapted viruses and found that vertebrate-passaged viruses do not lose fitness or transmission potential in mosquitoes. To understand the contribution of genetic changes to the enhanced virulence and transmission phenotype, we engineered these amino acid substitutions, singly and in combination, into a ZIKV infectious clone. We found that NS4A-E19G contributed to the enhanced virulence and mortality phenotype in mice. Further analyses revealed that NS4A-E19G results in increased viral loads and distinct transcriptional patterns for innate immune genes in the brain. None of the substitutions contributed to changes in mosquito vector competence. Together, these findings suggest that direct transmission chains could enable the emergence of more virulent ZIKV strains without compromising mosquito transmission capacity, although the underlying genetics of these adaptations are complex.

IMPORTANCE

Previously, we modeled direct transmission chains of Zika virus (ZIKV) by serially passaging ZIKV in mice and mosquitoes and found that direct mouse transmission chains selected for viruses with increased virulence in mice and the acquisition of non-synonymous amino acid substitutions. Here, we show that these same mouse-passaged viruses also maintain fitness and transmission capacity in mosquitoes. We used infectious clone-derived viruses to demonstrate that the substitution in nonstructural protein 4A contributes to increased virulence in mice.

KEYWORDS: Zika virus, arbovirus, evolution, pathogenesis, transmission

INTRODUCTION

The adaptive potential of RNA viruses is driven by error-prone replication which creates a heterogeneous swarm of virus genotypes within each host (1). RNA arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) therefore have the potential for rapid evolution but exhibit high degrees of consensus genome sequence stability in nature [summarized in reference (2)]. The need to navigate distinct host environments and barriers to infection and transmission is believed to restrict arbovirus evolution. Indeed, the fitness trade-off hypothesis for arboviruses posits that fitness gains in one host come at the cost of fitness losses in the other host. Paradoxically, a preponderance of experimental evidence suggests that host alternation does not automatically limit the adaptive potential of arboviruses [reviewed in references (3) and (4)]. Rather, arboviruses may be the ultimate generalists, evolving mechanisms to limit or avoid the effects of trade-offs from dual-host cycling. They may be positioned to evolve rapidly when novel conditions arise.

This is perhaps best exemplified by the fact that many arbovirus epidemics have been associated with virus genetic change. For example, Indian Ocean lineage chikungunya virus adaptation to Aedes albopictus was mediated by a series of envelope glycoprotein E2/E3 and E1 substitutions during an explosive outbreak on La Reunion Island (5, 6). Other examples of epidemic-enhancing mutations include West Nile virus adaptation for more efficient transmission by North American mosquitoes (7) and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus adaptations that produce high viral titers in horses (8). Finally, considerable research effort has been dedicated to identifying mutations that may have contributed to Zika virus (ZIKV) epidemic potential or contributed to the appearance of previously unobserved severe clinical manifestations [reviewed in reference (9)]. Whether these mutations are important determinants of ZIKV emergence and spread remains an open question (10 – 12).

However, ZIKV is unique among mosquito-borne viruses due to its capacity to directly transmit between humans via sexual transmission. While it is epidemiologically challenging to quantify the contribution of sexual transmission to infection incidence in endemic regions, recent studies have shown that sexual transmission may be a more important driver of ZIKV transmission than previously thought (13 – 15). The ability to forgo mosquito-borne transmission for sexual transmission therefore creates a scenario where a highly mutable virus may be able to explore broader sequence space leading to the potential for novel host-adaptive mutations becoming fixed in the human population. To this end, we recently explored the consequences of releasing ZIKV from alternate host cycling between mosquito and vertebrate hosts. We modeled single and alternate host transmission chains in Ifnar1-/- mice and Aedes aegypti mosquitoes (16). We found that mouse- and mosquito-adapted lineages replicated to significantly higher titers in mice compared to unpassaged ZIKV, and that mouse-adapted viruses were universally lethal. Mosquito-adapted and alternate-passaged viruses had more heterogeneous phenotypes, with some lineages producing enhanced mortality rates relative to unpassaged virus, and other lineages resulting in little to no mortality (16). We also found that during direct vertebrate transmission chains, ZIKV consistently evolved enhanced virulence coincident with the selection of two polymorphisms at a single locus in NS2A—A117V and A117T—and at NS4A-E19G and NS2A I139T (16). While these data demonstrate that ZIKVs experimentally evolved through direct vertebrate transmission chains possess increased virulence, we did not assess the potential trade-offs between virulence and transmission, nor did we functionally characterize these amino acid substitutions using reverse genetics.

To evaluate the extent to which experimental evolution of ZIKV through mice, mosquitoes, and alternate host passaging alters the vector competence phenotype in mosquitoes, we exposed Ae. aegypti to ZIKV from each passage series (n = two lineages per passage series) and assessed infection, dissemination, and transmission potential and compared these rates to unpassaged ZIKV. We found that the mouse-passaged lineages had no loss of fitness or transmission capacity in mosquitoes. To investigate the viral genetic determinants for enhanced virulence and maintenance of fitness and transmission capacity for these ZIKV variants, we engineered the NS2A-A117V, A117T, and NS4A-E19G substitutions—singly and in combination—into the Puerto Rican ZIKV isolate PRVABC59 (ZIKV-A117V, ZIKV-A117T, ZIKV-E19G, ZIKV-A117V/E19G, and ZIKV-A117T/E19G) and infected mice and mosquitoes with these viruses. This is the same parental isolate on which these mutations emerged (16). Viruses containing NS4A-E19G caused increased mortality and viremia, increased viral loads in the brain, and altered innate immune gene expression in mice. In contrast, vector competence studies showed no differences in transmission potential between ZIKV mutants and unpassaged viruses.

RESULTS

Mouse-adapted Zika viruses maintain fitness and transmission capacity in Aedes aegypti

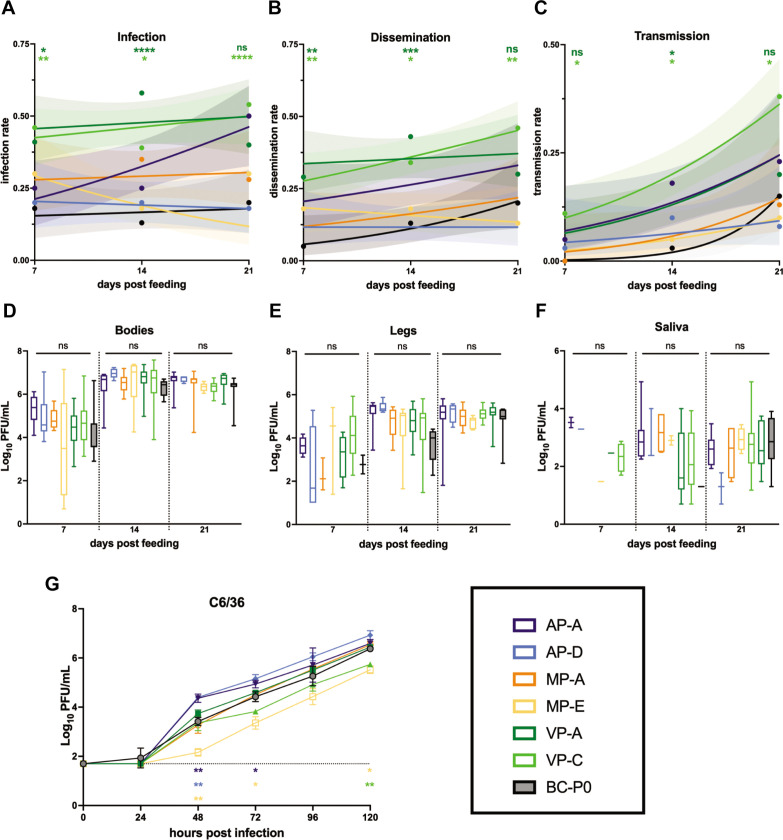

Previously (16), we performed in vivo serial passage experiments in which a molecularly barcoded ZIKV (ZIKV-BC), built on an Asian lineage genetic backbone, was passaged in five parallel replicates (lineages) for 10 passages in Ifnar1-/- mice or in Ae. aegypti mosquitoes. To mimic natural host cycling, ZIKV-BC was alternately passaged in mice and mosquitoes for 10 passages in five parallel lineages. After subcutaneous inoculation of mice at passage 1, alternating passage was conducted via natural bloodfeeding transmission with small cohorts of mosquitoes feeding on an infected mouse, and then feeding on a naive mouse 12 days later (16). To evaluate the extent to which serial or alternate passage altered ZIKV replicative fitness and overall virulence, the phenotypes of the passaged viruses were evaluated in Ifnar1-/- mice and compared to unpassaged ZIKV-BC. Briefly, mouse-adapted viruses were universally lethal, whereas mosquito-adapted and alternate-passaged were heterogeneous in their outcomes (16). Next, to assess how serial and/or alternate passage affects vector competence for the adapted viruses, we compared the relative abilities of a subset of viruses from each passage series to be transmitted by Ae. aegypti in the laboratory. Two representative lineages from each passage series were chosen for vector competence experiments (see Table 1 in Materials and Methods): n = two mouse-adapted ZIKVs, VP-A and VP-C; n = two mosquito-adapted ZIKVs, MP-A and MP-E; and n = two alternate-passaged ZIKVs, AP-A and AP-D. Since mouse-passaged virus had uniform lethality, we chose two lineages with the most distinct frequencies of amino acid substitutions [VP-A: mixed population of NS2A-117T and NS2A-117V; VP-C: highest frequency of NS2A-117V and NS4A-E19G; see reference (16)]. For the mosquito-adapted and alternate-passaged groups, we chose lineages that had distinct mortality phenotypes (see Table 1). To assess vector competence, mosquitoes were exposed to viremic bloodmeals (6.5–7.5 log10 plaque forming units (PFU)/mL) via water-jacketed membrane feeder maintained at 36.5°C. Infection, dissemination, and transmission rates were assessed at 7, 14, and 21 days post feeding (dpf; n = 39–80 per timepoint per virus group) using an in vitro transmission assay (16 – 18). Mosquitoes exposed to unpassaged ZIKV-BC served as experimental controls. Infection, dissemination, and transmission rates were similar for MP-A, MP-E, AP-A, AP-D, and ZIKV-BC at all timepoints. In contrast, VP-A and VP-C had significantly higher rates of infection at all timepoints compared to ZIKV-BC, with the exception of VP-A at 21d (two-tailed Fisher’s exact test) (Fig. 1A, green vs black). Dissemination rates were also significantly increased across all timepoints for VP-A and VP-C compared to ZIKV-BC, with the exception of VP-A at 21d (Fig. 1B, green vs black). Transmission rates of VP-C were significantly increased compared to ZIKV-BC at 21d (38% vs 15%, P = 0.011, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test) (Fig. 1C). Thus, ZIKV serial passage in mice resulted in no loss of fitness or transmission capacity in mosquitoes. One possible explanation for the shared fitness advantages in both mice and mosquitoes could be increased replicative capacity in both hosts. We therefore quantified infectious virus using plaque assays for all mosquito tissues that were positive in our vector competence assay and across all timepoints to assess whether the transmission advantage for VP-A and VP-C was due to increased replicative capacity of these viruses. We found no significant difference in infectious titers in any tissue between virus groups at any timepoint [one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test], and virus titers within virus groups were highly variable (Fig. 1D through F). Because the number of positive samples varied between groups and timepoints (bodies: n = 4–29 per group per timepoint; legs: n = 2–23 per group per timepoint; saliva: n = 0–17 per group per timepoint), we also directly compared in vitro replication kinetics between viruses on the mosquito cell line C6/36 (Fig. 1G). The majority of variant viruses gave similar growth curves to the unpassaged virus (ZIKV-BC) (Fig. 1G). However, MP-E had significantly lower titers at 48, 72, and 120 h post infection (hpi) compared to unpassaged virus (ZIKV-BC) (two-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, P < 0.02), which is consistent with low infection rates, dissemination rates, and transmission rates of this variant in vector competence assays. In contrast, VP-A and VP-C gave similar growth curves to ZIKV-BC with the exception of VP-C having significantly lower titer at 120 hpi (P < 0.0047). Still, this variant had the highest transmission rate in vector competence assays. Overall, these in vitro replication data further suggest that enhanced transmission potential is not due to enhanced replicative capacity.

TABLE 1.

Viruses used for vector competence (Fig. 1)

| Virus | Passage group | Mortality in mice (%) a |

|---|---|---|

| AP-A | Alternate | 100 |

| AP-D | Alternate | 0 |

| MP-A | Mosquito | 75 |

| MP-E | Mosquito | 0 |

| VP-A | Mouse | 100 |

| VP-C | Mouse | 100 |

| ZIKV-BC | Unpassaged | 12.5 |

Mortality determined in prior study, Riemersma et al. (16).

Fig 1.

Vector competence of serially passaged Zika virus lineages. Female Ae. aegypti mosquitoes were exposed to passaged ZIKV strains via an artificial infectious bloodmeal and collected 7, 14, and 21 dpf. Infection (A), dissemination (B), and transmission (C) rates over the three collection timepoints are shown. Infection rate is the percentage of ZIKV-positive bodies, dissemination rate is the percentage of positive legs, and transmission rate is the percentage of positive saliva samples of total mosquitoes that took a bloodmeal (determined by plaque assay). Data points represent the empirically measured percentages (n = 39–80 per data point). The lines represent the logistic regression results and the shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals of the logistic regression fits. Infection, dissemination, and transmission rates of VP-A and VP-C were compared to ZIKV-BC at each timepoint (two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, not significant. Infectious virus was quantified via plaque assay from bodies (D), legs (E), and saliva (F) from all positive samples. Mean titers were not significantly different between virus groups in any tissue at any timepoint (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). ns, not significant. (G) In vitro growth kinetics of passaged ZIKV strains in C6/36 cells. Data points represent the mean of three replicates at each timepoint. Error bars represent standard deviation. Differences in viral titer at each timepoint were compared to ZIKV-BC (two-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons test). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. The dotted line indicates the assay limit of detection.

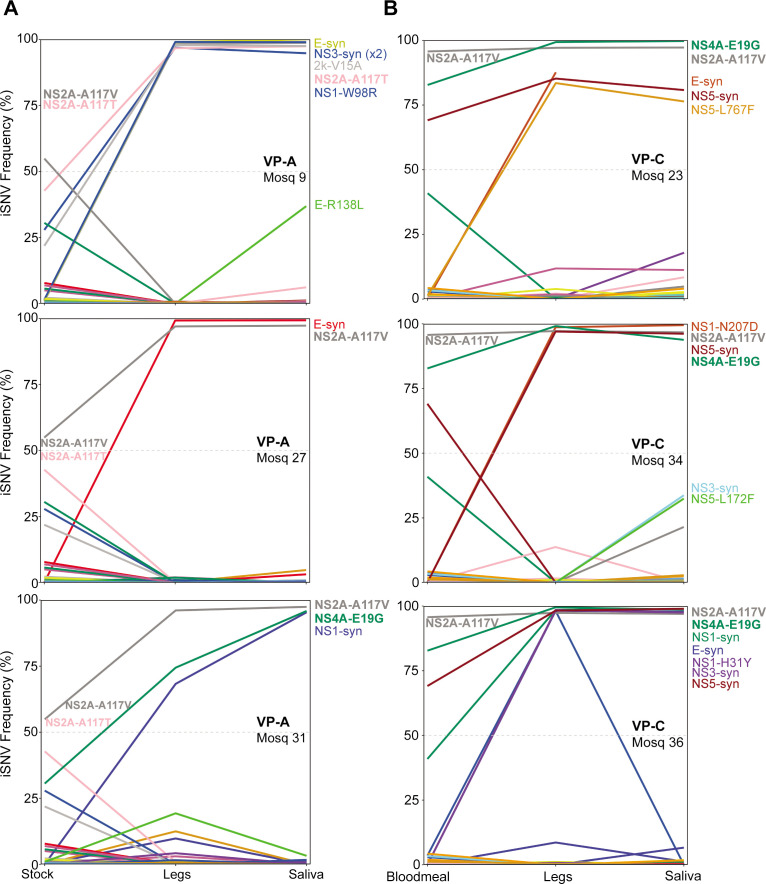

Next, we performed deep sequencing of virus populations replicating in legs (disseminated population) and saliva (transmitted population) from the VP-A- and VP-C-exposed mosquitoes at 21 dpf to confirm whether the amino acid substitutions selected for during mouse serial passage (NS2A-A117V, NS2A-A117T, NS2A-I139T, NS4A-E19G) were stably maintained in mosquito samples. A loss of these mutations would indicate that they are not advantageous in mosquitoes, and therefore not contributing to the maintenance of fitness and transmission capacity. The VP-A stock used to make infectious bloodmeals had a mixed population of V and T substitutions at NS2A position 117; in one mosquito (#9), NS2A-117T reached nearly 100% frequency in 21d saliva (Fig. 2A), whereas NSA-117V was present at nearly 100% frequency in the remaining saliva samples. In contrast, 2/3 VP-A mosquitoes lost NS4A-E19G substitution while in 1/3, NS4A-19G was fixed in 21d saliva (Fig. 2A). Mosquitoes exposed to VP-C had nearly 100% NS2A-117V frequency in the stock and bloodmeal, and this substitution was maintained in all mosquitoes tested (Fig. 2B). VP-C mosquitoes also had NS4A-E19G present at nearly 100% frequency in the saliva at 21 dpf. NS2A-I139T, which was the lowest frequency variant, was not present in any mosquito samples sequenced.

Fig 2.

Deep sequencing of viral populations in mosquito tissues. Paired legs and saliva samples from individual mosquitoes exposed to VP-A (A) and VP-C (B) 21 dpf were deep sequenced. Lines represent single nucleotide variant (SNV) frequency percentages between the stock or bloodmeal, legs, and saliva.

In vitro and in vivo characterization of mutant ZIKV clones

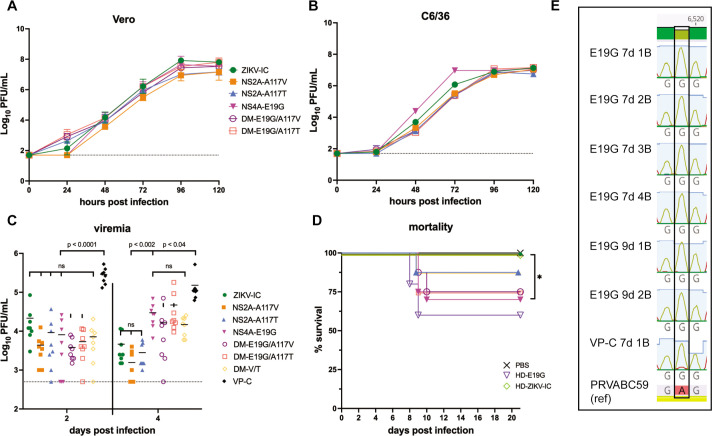

Phenotypic characterization of our experimentally evolved ZIKVs established that mouse-adapted viruses were more virulent in mice, maintain fitness and transmission capacity in mosquitoes, and share amino acid substitutions that arose during serial passage in mice that are maintained during infection in mosquitoes. We therefore hypothesized that one of, or a combination of, the amino acid substitutions NS2A-A117V, NS2A-A117T, or NS4A-E19G is contributing to the enhanced virulence phenotype. Since NS2A-I139T was the lowest frequency variant and was lost during mosquito infection, we did not include it in our panel. To assess the roles of NS2A-A117V, NS2A-A117T, and NS4A-E19G in virulence and transmission, we engineered these substitutions, singly and in combination, into a Zika virus infectious clone derived from the Puerto Rican ZIKV isolate PRVABC59 (single mutants: NS2A-117V, NS2A-117T, NS4A-E19G; double mutants: DM-E19G/A117V, DM-E19G/A117T). This is the same virus genetic backbone used in the previous experimental evolution study (16). Deep sequencing confirmed successful introductions of target mutations at a frequency >99%. Prior to use in vivo, we assessed viral infectivity and replication in vitro in Vero cells and C6/36 cells. All mutant viruses—as well as the control virus bearing the PRVABC59 isolate consensus sequence (ZIKV-IC)—gave similar growth curves in both cell types (Fig. 3A through B). Of note, NS4A-E19G did reach significantly higher titers compared to ZIKV-IC at 48 h and 72 hpi in C6/36 cells (mixed-effects model with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons), but these differences were resolved by 96 hpi (Fig. 3B). Overall, these growth curves suggest that introducing these substitutions did not have a significant effect on either infectivity or replicative capacity in vitro.

Fig 3.

In vitro and in vivo characterization of ZIKV mutant clones. In vitro growth kinetics of ZIKV clones in Vero (A) and C6/36 (B) cells. Data points represent the mean of three replicates at each timepoint. Error bars represent standard deviation. (C) Serum viremia 2 and 4 days post infection (dpi) of Ifnar1 -/- mice inoculated with 103 PFU of different ZIKV clones [n = 8 for virus groups, n = 4 for phosphate buffered saline (PBS) control]. Serum viremia for mutant viruses was compared to previously published viremia data from VP-C infection. Differences in mean serum viremia between virus groups was compared by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ns, not significant. The dotted line indicates the assay limit of detection. (D) Survival curves of Ifnar1 -/- mice inoculated with 103 PFU of virus, or a PBS control. HD-E19G and HD-WTic groups were inoculated with 104 PFU. Survival curves were compared to WTic by Fisher’s exact test. *, P < 0.05. (E) Chromatograms from Sanger sequencing of a subset of E19G 7d and 9d and VP-C 7d brains showing confirmation of the maintained NS4A position 19 substitution (nucleotide substitution at nt 6519 of the polyprotein: GAG → GGG). Sequenced amplicons were aligned to ZIKV-PRVABC59.

Next, to evaluate the extent to which the NS2A and NS4A amino acid substitutions alter the ZIKV virulence phenotype in vivo, we subcutaneously (s.c.) inoculated 5- to 7-week-old Ifnar1-/- mice in the footpad with 1 × 103 PFU of the different ZIKVs (n = 8–20), or phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to serve as experimental controls (n = 4). We also included a group inoculated with a 1:1 mixture of the double mutants (DM) to achieve a mixed population of NS2A-A117V and NS2A-A117T (DM-V/T) to assess whether diversity at this position was necessary for recapitulating the virulence phenotype. We collected serum 2 and 4 days post infection (dpi) to compare viremia kinetics between viruses. At 2 dpi, there were no significant differences in serum titers between the different ZIKVs (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) (Fig. 3C). At 4 dpi, serum titers did not differ significantly between ZIKV-IC, NS2A-A117V, and NS2A-A117T. However, NS4A-E19G and the double-mutant viruses all reached significantly higher titers at 4 dpi compared to NS2A-A117V, NS2A-A117T, and ZIKV-IC (P < 0.002, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Serum titers at 4 dpi in the NS4A-E19G and the double-mutant infected groups did not differ significantly from each other (P > 0.13, one-way ANOVA). Additionally, when comparing these data to serum titers from mice infected with VP-C from reference (16), all mutant viruses and ZIKV-IC had significantly lower viremia at both timepoints (Fig. 3C).

Only the NS4A-E19G-inoculated groups showed significant mortality compared to ZIKV-IC and PBS-inoculated, age-matched controls (30% mortality, log-rank test, P = 0.02) (Fig. 3D). DM-E19G/A117V and DM-E19G/A117T groups showed similar rates of mortality (25%). Because NS4A-E19G did not recapitulate the 100% mortality phenotype observed with the uncloned mouse-adapted viruses (16), we inoculated a group of mice (n = 5) with a higher challenge dose (104 PFU) of NS4A-E19G or ZIKV-IC. The higher-dose, NS4A-E19G-inoculated group resulted in a 40% mortality rate (Fig. 3D). Synthesizing the mortality data from all infections with viruses containing NS4A-E19G (low-dose and high-dose NS4A-E19G and double mutants) compared to those without this substitution (ZIKV-IC and NS2A single mutants), we conclude that the virulence phenotype is NS4A-E19G dependent.

Given the incomplete penetrance of the NS4A-E19G phenotype, we posited that this substitution could have at least partially reverted to wild type in mice that did not succumb to infection and had lower levels of virus detectable in the brain. We therefore sequenced virus from brain tissue of mice infected with NS4A-E19G 7 and 9–10 dpi and determined that this substitution was stably maintained during mouse infection (Fig. 3E).

Increased brain viral loads and innate immune gene expression are NS4A-E19G dependent

ZIKV NS4A has been shown to antagonize interferon induction via interactions with the retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs), RIG-I, and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA-5), which are cytosolic RNA sensors that sense viral RNAs during infection and trigger signaling pathways resulting in the production of type I interferon (type I IFN) and proinflammatory cytokines (19, 20). Since our experiments were done in mice that lack type I IFN receptor 1 function, we expect that this antagonism occurs via RLR signaling through the mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS) pathway (21). While expression may differ depending on tissue type and by a specific virus, prior studies of West Nile virus (WNV) establish that RIG-I, MDA-5, as well as Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR-3) function in Ifnar1−/− mice to limit flavivirus infection (22, 23). Indeed, increasing evidence suggests that viruses can escape the host antiviral response by interfering at multiple points in the MAVS signaling pathway, thereby maintaining viral replication and expanding tropism (24). MAVS signaling is initiated by RLRs that recognize viral RNA; therefore, we posit that NS4A-E19G confers an enhanced ability to evade innate immune responses in mice resulting in higher titers and broader tissue tropism, including neuroinvasion (25 – 27).

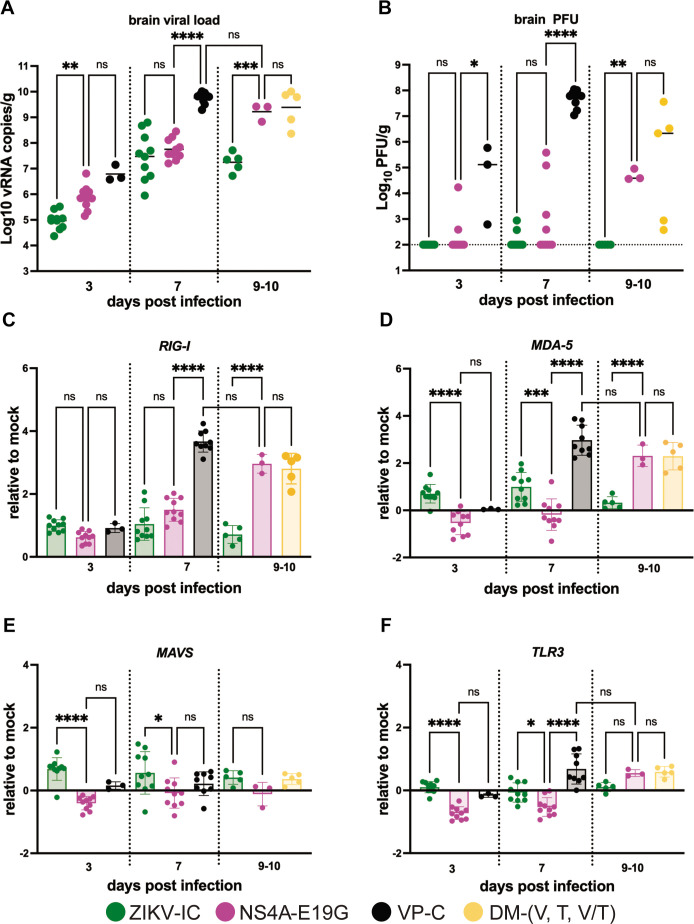

To evaluate whether NS4A-E19G contributes to infection of the brain, we s.c. inoculated Ifnar1-/- mice with 103 PFU of NS4A-E19G, ZIKV-IC, or the mouse-adapted virus lineage, VP-C. Brains were collected at 3 or 7 dpi, and from animals that met endpoint criteria (~9–10 dpi) from experiments described above (Fig. 3D). Brains were also collected at 9 dpi from a group of ZIKV-IC-inoculated mice to serve as controls for the 9–10 dpi timepoint. Brains from VP-C-inoculated animals could not be collected from later timepoints because all mice met endpoint criteria by 7 dpi [see reference (16)]. Infectious virus was quantified from brain homogenate via plaque assay, and viral RNA (vRNA) loads were evaluated via quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR). Viral loads in the brain were significantly higher in mice infected with NS4A-E19G compared to ZIKV-IC at 3 dpi (P = 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test), while mean viral load did not differ between NS4A-E19G and VP-C at 3 dpi (Fig. 3A). Viral load increased in all groups from 3 to 7 dpi, with no significant difference in brain vRNA loads between ZIKV-IC and NS4A-E19G-inoculated groups (Fig. 4A). At 9–10 dpi, vRNA loads continued to increase in animals infected with NS4A-E19G or double mutants, but did not differ significantly from VP-C-inoculated groups at 7 dpi. ZIKV-IC viral loads were significantly lower than NS4A-E19G and double mutants at 9 dpi (P < 0.001). Similar patterns were observed in infectious virus titers in the brain (Fig. 4B). Infectious virus was only detectable at low levels in two ZIKV-IC-infected brains, two samples at 3 dpi and four samples at 7 dpi from NS4A-E19G-inoculated groups. Although not statistically different from ZIKV-IC at 7 dpi, the number of plaque assay-positive brains from NS4A-E19G-inoculated animals does roughly parallel the mortality rate observed in this group. At 9–10 dpi, all NS4A-E19G and double mutant-infected groups had detectable infectious virus in the brain, while no ZIKV-IC brains were positive (Fig. 4B). While discrepancies in patterns between vRNA and infectious titers are likely due to factors such as differential assay sensitivity and RT-qPCR detecting partial and non-viable RNA fragments, both assays show increased detection of virus infection in the brain of viruses possessing NS4A-E19G.

Fig 4.

Differential brain viral loads and innate immune gene responses to ZIKV mutants. Viral RNA (A) and infectious virus (B) were quantified from brain tissue collected 3, 7, and 9–10 days after 103 PFU inoculation of Ifnar1-/- mice with ZIKV-IC, NS4A-E19G, VP-C or, double-mutant clones by qRT-PCR and plaque assay, respectively. The dotted line indicates the assay limit of detection (B). Transcript abundance of RIG-I (C), MDA-5 (D), MAVS (E), and TLR3 (F) was analyzed from brains collected 3, 7, and 9–10 dpi by qPCR. Expression levels were normalized to ActB and Hprt and the ddCT value was calculated as log2 fold change expression relative to mock-inoculated mice. Data points represent individual samples. Means with standard deviation are shown. Viral loads, infectious viral titers, and relative fold change of transcript abundance were compared between virus groups at each timepoint by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Next, to evaluate whether NS4A-E19G modulates the transcriptional activity of Rig-i (Ddx58), Mda-5 (Ifih1), Mavs, and Toll-like receptor 3 (Tlr3) in the brain, we measured relative transcript abundance at 3, 7, and 9–10 dpi. Tlr3 was included as an additional pattern recognition receptor because it detects double-stranded RNA and has been shown to modulate the inflammatory response to ZIKV infection in astrocytes, as well as interact with the Rig-i pathway (28, 29). Additionally, in the context of other arboviruses, Tlr3 has been shown to be both protective and pathologic during West Nile virus (WNV) infections in the brain and is expressed in response to infection in both wild-type and Ifnar1−/− mice (23, 30, 31).

At 3 dpi, we observed modest induction of Rig-i for all virus groups compared to mock-inoculated controls (Fig. 4C). At 7 dpi, ZIKV-IC and NS4A-E19G had similar Rig-i expression profiles that were significantly lower than VP-C. However, at 9–10 dpi, viruses containing NS4A-E19G had significantly higher Rig-i transcript abundance compared to ZIKV-IC (P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Mda-5 expression patterns were similar to Rig-i, with increased Mda-5 abundance detected at 7 dpi in VP-C and at 9–10 dpi for viruses containing NS4A-E19G (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, at 3 and 7 dpi, brains of mice infected with NS4A-E19G had significantly less Mda-5 transcript abundance compared to those of mice infected with ZIKV-IC (P < 0.0002, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons). In contrast, Mavs and Tlr3 were not induced at the later timepoints for any virus group, but brains of mice infected with NS4A-E19G had significantly less Mavs and Tlr3 transcript abundance at 3 and 7 dpi compared to ZIKV-IC (P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) (Fig. 4E through F).

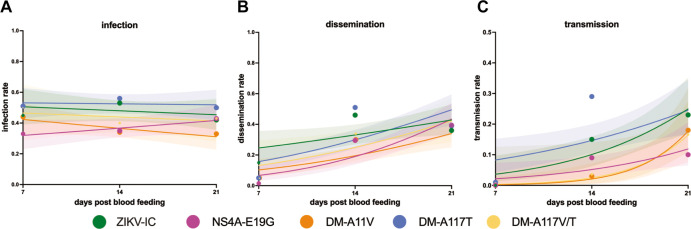

Transmission potential is not impacted by NS2A-117V, NS2A-117T, or NS4A-19G

Finally, to evaluate the extent to which the NS2A and NS4A amino acid substitutions altered mosquito vector competence, we compared the relative abilities of NS4A-E19G, DM-E19G/A11V, DM-E19G/A117T, and ZIKV-IC to be transmitted by Ae. aegypti.

We focused on viruses containing the NS4A-E19G substitution because of its role in the virulence phenotype in mice (Fig. 3). Because vector competence for the double mutants did not significantly differ from the ZIKV-IC control, the single NS2A mutants were not pursued in vector competence experiments. Vector competence was performed as described earlier. Briefly, female Ae. aegypti mosquitoes were exposed to bloodmeals containing either ZIKV-IC, NS4A-E19G, DM-E19G/A11V, DM-E19G/A117T, as well as a bloodmeal that contained a 1:1 mixture of the two double mutants (DM-V/T). Bloodmeal titers ranged from 6.6 to 7.3 log10 PFU/mL. Infection, dissemination, and transmission rates were assessed at 7, 14, and 21 dpf (n = 20–80 per timepoint per virus group). ZIKV-IC and NS4A-E19G exposures were repeated in two independent replicates with distinct generations of mosquitoes to account for stochastic variation between generations. No differences were observed in infection, dissemination, or transmission rates at any timepoint between viruses (Fig. 5A through C).

Fig 5.

Vector competence for ZIKV mutants. Female Ae. aegypti mosquitoes were exposed to passaged ZIKV strains via an artificial infectious bloodmeal and collected 7, 14, and 21 dpf. Infection (A), dissemination (B), and transmission (C) rates over the three collection timepoints are shown. Infection rate is the percentage of ZIKV-positive bodies, dissemination rate is the percentage of positive legs, and transmission rate is the percentage of positive saliva samples (determined by plaque assay screen). Data points represent the empirically measured percentages (n = 20–80 per data point, point size is proportional to group size). The lines represent the logistic regression results and the shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals of the logistic regression fits.

DISCUSSION

Here, we expanded on our previous work (16), to demonstrate that ZIKV adaptation to mice, which increased virulence, does not impact fitness or transmission capacity in mosquitoes. These observations are important because knowledge on how flaviviruses limit or avoid the effects of trade-offs from dual-host cycling is limited, and thus providing further evidence that flaviviruses can limit the effects of trade-offs from host cycling. This finding is consistent with observations from other studies that mostly refute the trade-off hypothesis for arboviruses (3, 4, 32, 33). For example, serial passaging of WNV in chicks resulted in avian-passaged WNV acquiring fitness gains in both chicks and Culex pipiens mosquitoes (32). Similarly, experiments with single-host passaged St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV) found that some avian-passaged SLEVs displayed fitness gains in chicks without fitness losses in mosquitoes (33). Notably, neither study assessed transmission potential of single-host passaged viruses. We assayed mosquito vector competence by quantifying differences in the rates of infection, dissemination, and transmission and found that mouse adaptation results in no fitness or transmission costs in mosquitoes. We also found that during direct vertebrate transmission chains, ZIKV consistently evolved these enhanced virulence and transmission properties coincident with the selection of two polymorphisms at a single site in NS2A—A117V and A117T—and at NS4A-E19G (16). NS2A 117V is present on naturally isolated ZIKV genomes from humans and Ae. aegypti reported in the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC), indicating it is a viable variant in natural transmission cycles. Importantly, NS4A-E19G has also been identified in a naturally isolated ZIKV genome from a pregnant woman in Honduras in 2016, reported in Nextstrain, and has not been characterized prior to this study. In contrast, the NS2A 117T variant has not been previously detected in natural or laboratory isolates to our knowledge (BV-BRC database: https://www.bv-brc.org; Nextstrain: https://nextstrain.org). The emergence of naturally occurring variants within our passaging experiments supports the biological relevance of this experimental system to mimic natural transmission dynamics and produce variants viable in nature which warrant further characterization.

All studies seeking to link viral genotype to phenotype using reverse genetics can be limited by the genetic context of the cloned virus(es) chosen for analysis. As a result, it may be that these substitutions examined in the context of different ZIKV strains might have different phenotypic effects. The parental virus used in our studies was PRVABC59, a 2016 isolate from Puerto Rico. A previous study found that NS2A-A117V enhanced virulence of two additional strains of American-sublineage ZIKV in mice (34). However, we did not observe a significant difference in pathogenic potential of ZIKV encoding alanine or valine at NS2A position 117. Flavivirus NS2A and NS4A have been previously shown to act as IFN antagonists (19, 20 35) and as a result are mediators of flavivirus pathogenesis (36, 37). Here, the virulence phenotype was NS4A-E19G dependent.

Flavivirus NS4A is a multifunctional protein involved in membrane remodeling and the establishment of the viral replication complex (38, 39), innate immune antagonism (19), as well as modulating autophagy, which is important in neurodevelopment (40, 41). Position 19 falls within the cytoplasmic N-terminus of NS4A, a region particularly important for protein stability and homo-oligomerization (36 ). While studies of ZIKV NS4A are limited, studies investigating the role of this region of NS4A in both dengue virus (DENV) and WNV found that mutations introduced into this region were highly attenuating to viral replication (42 – 44). Another study, using a yellow fever virus strain with defective replicative capacity due to a large in-frame deletion in the NS1 gene, found that replication could be restored by an adaptive mutation in the N-terminal region of NS4A (45). Previous studies identified interactions between NS4A and NS2A which promote neurovirulence and innate immune antagonism (19). We had therefore posited that there may be an epistatic interaction between the NS2A and NS4A substitutions. Our results, however, show similar outcomes from clones containing NS4A-E19G with or without NS2A substitutions, suggesting there is no epistatic interaction between the NS4A-E19G and NS2A substitutions—at least in the environments tested here—nor do these mutations have functionally redundant roles in promoting neurovirulence.

Little is known about which regions of the protein are involved in NS4A-mediated immune regulation. We identified distinct patterns of innate immune gene expression in the brain between ZIKV-IC-infected brains and NS4A-E19G-infected brains. The temporal Mda-5 expression pattern suggests that the NS4A-E19G substitution may contribute to more efficient suppression of Mda-5 expression early in infection. Alternatively, increased abundance of both Rig-i and Mda-5 at later timepoints in brains from both VP-C and NS4A-E19G groups suggests that increased innate immune activation may be responsible for adverse outcomes in these mice, but this will require further confirmation. Early suppression of Mda-5 , Mavs, and Tlr3 suggests that NS4A-E19G may contribute to an enhanced ability to evade early innate immune responses, and thus expand tissue tropism, which we observed as increased viral loads in the brain, mortality, and viral replication with viruses containing NS4A-E19G. Alternatively, significant induction of Rig-i and Mda-5 later in infection suggests increased RLR signaling in the brain, which may contribute to the virulence phenotype for NS4A-E19G viruses (31, 46). Although the exact mechanism cannot be resolved from these data, the results clearly show differences in the modulation of innate immune gene expression for viruses containing NS4A-E19G compared to ZIKV-IC. We therefore speculate that increased immune activation in the brain of NS4A-E19G-infected mice may contribute to immunopathology. This could happen due to increased proinflammatory cytokine production from RLR signaling (47 – 49), but we did not test that here. Numerous proteins—such as a subset of TRIM proteins—negatively regulate the RIG-I pathway to protect against prolonged signaling-induced immunopathology, so it is possible that the NS4A substitution facilitates improved antagonism of negative regulatory proteins of these immune pathways (50, 51). Because our study was conducted in mice that lack type I IFN receptor 1 function and we do not know the extent to which NS4A-E19G may antagonize these innate immune pathways in the presence of fully intact interferon signaling, our data suggest that increased viral loads in the brain likely contribute to this change in innate immune gene expression, but more studies are needed to disentangle the exact underlying mechanism(s). We do, however, provide further support for the multifaceted role of NS4A in both replication and immune modulation.

NS4A may also play a functionally redundant and evolutionarily conserved role in the mosquito host. There are considerable similarities in insect and mammalian cytosolic sensing of RNA; RIG-I-like antiviral proteins have been identified in insects, including mosquitoes (52 – 55). In mammals, RLRs are critical for the production of type I interferon in cells, whereas, in insects, Dicer-2 is homologous to mammalian RLRs (52). The mammalian RLRs RIG-I and MDA-5 sense cytosolic viral RNAs during infection and activate signaling pathways that culminate in the production of type I IFNs and proinflammatory cytokines as part of the antiviral immune response (56, 57). In mosquitoes, Vago appears to function as an IFN-like antiviral cytokine that is activated in a Dicer-2-dependent manner (53). However, since neither polymorphism in NS2A or NS4A impacted mosquito vector competence (Fig. 4), we do not have robust evidence for this in our system.

Importantly, the virulence phenotype we observed with NS4A-E19G was not 100% penetrant. Previously, it has been shown that viral population diversity is important for fitness, virulence, and pathogenesis (58 – 60). For example, polio viruses with reduced viral diversity had an attenuated phenotype in mice and also lost neurotropism (58). However, when we mixed both double mutants (DM-E19G/A117V and DM-E19G/A117T) for mosquito vector competence and mouse pathogenesis experiments, the mixed populations had no impact on the mosquito vector competence phenotype and were similarly pathogenic to the single NS4A-E19G virus. Although both passaged and clone viruses were constructed on the same parental backbone (ZIKV-PRVABC59), the passaged viruses contained a molecular barcode and thus barcode diversity while the mutant ZIKVs used here did not. While we would not expect silent barcodes to enhance virulence, and there is no evidence for this when comparing the virulence phenotype of the barcoded virus versus the ZIKV-IC used here (16, 61), the accumulation of genetic diversity may be important for the virulence phenotype. Critically, we were not able to investigate all low-frequency variants present in the mouse-passaged viruses. For example, NS2A I139T was found in all five lineages but was only found on less than 50% of the ZIKV genomes (16). We chose not to investigate this variant because NS2A I139T was not detected when we put VP-A and VP-C into mosquitoes (Fig. 1H).

Since the NS4A-E19G virus was unable to completely recapitulate the virulence phenotype observed with the mouse-adapted viruses from our previous study (16), we posit that this phenotype is multifactorial, involving some combination of the E19G amino acid substitution, virus population diversity, and codon usage—all of which are supported by the work presented herein and by the analyses presented in our previous paper (16 ). Additionally, like most studies, we focused on the coding region of the genome. The untranslated 5´ and 3´ ends of the flavivirus genome (5´ and 3´ untranslated regions [UTRs]), however, have gained increased focus for the multifaceted roles of UTR-derived subgenomic flavivirus RNAs (sfRNA) in viral replication, mosquito transmission, as well as viral pathogenicity in vertebrate and invertebrate hosts (62 – 65). In fact, a 2015 study identified two substitutions within the 3´ UTR of an emergent strain of DENV, which resulted in increased production of sfRNAs that reduced RIG-I signaling and subsequent IFN induction, and ultimately contributed to greater epidemiological fitness of this DENV strain (66). Future study of the evolutionary trajectory of ZIKV, as well as other RNA viruses, should consider these alternative genetic components as potential determinants for changes in viral phenotype. The future spread of ZIKV is unpredictable; however, these studies collectively show that direct transmission chains could enable the emergence of more virulent and transmissible ZIKV strains. While the underlying genetics of these adaptations remain unclear, these studies highlight the capacity of flaviviruses to adapt in ways which limit the restrictions of dual-host cycling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses

African green monkey kidney cells (Vero; ATCC #CCL-81) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin, and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. Aedes albopictus mosquito cells [C6/36; American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) #CRL-1660] were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin, and incubated at 28°C in 5% CO2. Cell lines were obtained from the ATCC and were tested and confirmed negative for mycoplasma. Viruses were generated by in vivo passaging of a barcoded Zika virus infectious clone derived from the PRVABC59 strain followed by cell culture amplification after 10 passages as previously described (16). For vector competence experiments with passaged viruses, amplified passage 10 viruses were passed through another round of cell culture amplification and then concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal filter unit (Millipore Sigma) to achieve necessary infectious bloodmeal titers. Strains used for these experiments are presented in Table 1 (below).

Generation of ZIKV mutant clones

Mutagenic primers were designed using SnapGene 6.0.2 software (GSL Biotech). PCRs were performed using the SuperFi II Master Mix (Thermo Fisher 12368010), and the products were gel purified using the Machary-Nagel NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up kit (740609). Amplicons were assembled using the NEB Builder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (E2621L). The assembly products were digested with DpnI (R0176S), lambda exonuclease (M0262S), and exonuclease I (M0293S), and amplified using SuperPhi RCA Premix Kit with Random Primers (Evomic Science catalog number PM100) ( 67). RCA products were then transfected into HEK293A cells (68). The supernatant was harvested, clarified by centrifugation, and sequenced by Sanger sequencing to confirm the mutation of interest was introduced.

Viral sequencing

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) and analysis

ZIKV mutant clones were additionally deep-sequenced to further confirm that no other polymorphisms were detected in these stocks, as previously described (69).

For sequencing from mosquito tissue samples, viral RNA was extracted from 50 µL of saliva and 200 µL of bodies, virus stocks, and bloodmeals. All RNA extractions were performed on a Maxwell 16 instrument (Promega) with the Maxwell RSC Viral Total Nucleic Acid Purification Kit and eluted in 50 µL of nuclease-free water. Whole genome ZIKV sequencing libraries were then prepared and sequenced as previously described (16). WGS libraries were generated using the previously described tiled PCR amplicon approach (70, 71). WGS libraries were sequenced with paired-end 150 bp reads on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 by the UW Biotechnology Center. Similarly, WGS analysis for mosquito samples was conducted as previously described (16). Briefly, raw reads were quality trimmed, merged, and aligned to the ZIKV PRVABC59 reference strain. Consensus sequences were extracted and variants were called against reference and consensus sequences. Frequency of single nucleotide variants (SNVs) across paired mosquito samples was analyzed using previously developed pipelines. Data processing, analysis, and visualization scripts are publicly available (https://github.com/tcflab/ZIKVBC_HostCycling).

Sanger sequencing

A 388 bp region surrounding NS4A position 19 was amplified from total RNA extracted from a subset of brains using OneStep RT-PCR (Qiagen) using the following primers: Forward: (5´- AGAGTGCTCAAACCGAGGTG-3′), Reverse: (5´- TTTCCGAGAGCCACATGAGC-3′). Amplicons were sequenced directly by Sanger sequencing (Azenta Life Sciences). Sequences were viewed with Geneious Prime.

Plaque assay

Infectious ZIKV from mouse serum and tissue, mosquito tissue, in vitro growth curves, and titrations from virus stocks was quantified by plaque assay on Vero cell cultures. Duplicate wells were infected with 0.1 mL aliquots from serial 10-fold dilutions in growth media and virus was adsorbed for 1 h. Following incubation, the inoculum was removed, and monolayers were overlaid with 3 mL containing a 1:1 mixture of 1.2% oxoid agar and 2× DMEM (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% (vol/vol) FBS and 2% (vol/vol) penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 4 days for plaque development. Cell monolayers then were stained with 3 mL of overlay containing a 1:1 mixture of 1.2% oxoid agar and 2× DMEM with 2% (vol/vol) FBS, 2% (vol/vol) penicillin/streptomycin, and 0.33% neutral red (Gibco). Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C and plaques were counted.

Virus isolation

Total RNA was extracted and purified from homogenized brain tissue using a Direct-zol RNA kit (Zymo Research) and used for onward analysis of vRNA quantity and gene expression. RNA was then quantified using quantitative RT-PCR.

qRT-PCR

Viral RNA was quantified from extracted total RNA from brain tissue by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR as described previously (10). The RT-PCR was performed using the Taqman Fast Virus 1-step master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on a QuantStudio3 (Thermo Fisher). The viral RNA concentration was determined by interpolation onto an internal standard curve composed of seven 10-fold serial dilutions of a synthetic ZIKV RNA fragment. The ZIKV RNA fragment is based on a ZIKV strain derived from French Polynesia that shares >99% identity at the nucleotide level with the Puerto Rican lineage strain from which all viruses were derived that are used in the infections described in this report.

Gene expression

cDNA was synthesized using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems) from RNA extracted from brain homogenate as previously described. Gene expression of RIG-I, MDA-5, MAVS, and TLR3 was then quantified from cDNA by qPCR using customized TaqMan Array Mouse Antiviral Response 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher) run on a QuantStudio3 (Thermo Fisher). Innate immune gene transcript abundance was normalized to ActB and Hprt and then the threshold cycle value (2-delta delta CT) was calculated relative to mock-inoculated controls.

In vitro viral replication

Six-well plates containing confluent monolayers of Vero and C6/36 cells were inoculated with each clone virus (WTic, NS4A-E19G, NS2A-A117V, NS2A-A117T, DM-E19G/A117V, DM-E19G/A117T) in triplicate at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01 PFU/cell. After 1 h of adsorption at 37°C, inoculum was removed and the cultures were washed three times. Fresh media were added and the cell cultures were incubated for 5 days at 37°C with aliquots removed every 24 h and stored at −80°C. Viral titers at each timepoint were determined by plaque assay on Vero cells.

Mice

Ifnar1−/− mice on the C57BL/6 background were bred in the specific pathogen-free animal facilities of the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine. Mixed sex groups of 5- to 7-week-old mice were used for all experiments.

Subcutaneous inoculation

Ifnar1−/− mice were subcutaneously inoculated in the left hind footpad with 103 PFU of the selected ZIKV clone, or VP-C in 20 µL of sterile PBS or with sterile PBS alone as experimental controls. An inoculum titer or 103 PFU was selected to match the prior study of passaged ZIKV viruses in mice (16). An additional 104 PFU inoculation group was included for WTic and NS4A-E19G. Submandibular blood draws were collected 2 and 4 dpi to confirm viremia and compare replication kinetics. Mice were weighed daily and monitored for clinical signs of morbidity. Morbidity was rated on a scale of 0–6: 0—normal; 1—ruffled fur; 2—hunching, mild to moderate weakness, ataxia, distended abdomen, diarrhea; 3—severe weakness, tremors, circling, head tilt, seizures; 4—paralyzed limb; 5—morbid, non-responsive; 6—dead. Mice were euthanized at the experimental endpoint of 21 dpi, or if they met early endpoint euthanasia criteria as defined by a loss of 20% of original body weight or reached a clinical score of greater than or equal to 3.

Mouse necropsy

Following inoculation with WTic, NS4A-E19G, or VP-C, mice were sacrificed at 3 and 7 dpi, or if they met early endpoint criteria. Immediately following euthanasia, brain tissue was carefully dissected using sterile instruments, placed in a culture dish, rinsed with sterile PBS, and then brains were individually collected in pre-weighed tubes of PBS supplemented with 20% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. These tissues were then weighed and homogenized by either Omni homogenizer (Omni International, Omni Tissue Homogenizer) 115V) or by 5 mm stainless steel beads with a TissueLyser (Qiagen) and used for onward analysis of infectious virus and vRNA quantification, and gene expression analysis.

Mosquito strain and colony maintenance

All mosquitoes used in this study were maintained at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities as previously described (72) in an environmental chamber at 26.5 ± 1°C, 75% ± 5% relative humidity, and with a 12 h light and 12 h dark photoperiod with a 30-min crepuscular period at the beginning of each light cycle. The Aedes aegypti Gainesville strain used in this study was obtained from Benzon Research (Carlisle, PA), and was originally derived from the USDA “Gainesville” strain. Three- to 6-day-old female mosquitoes were used for all experiments.

Vector competence studies

Mosquitoes were exposed to virus-infected bloodmeals via water-jacketed membrane feeder maintained at 36.5°C (73). Bloodmeals consisted of defibrinated sheep blood (HemoStat Laboratories, Inc.) and virus stock, yielding infectious bloodmeal titers ranging from 6.5 to 7.5 log10 PFU/mL. Bloodmeal titer was determined after feeding. Infection, dissemination, and transmission rates were determined for individual mosquitoes and sample sizes were chosen using well-established protocols (17, 18, 74, 75). Briefly, mosquitoes were sucrose starved overnight prior to bloodmeal exposure. Mosquitoes that fed to repletion were randomized, separated into cartons in groups of 40–50, and maintained on 0.3 M sucrose in a Conviron A1000 environmental chamber at 26.5 ± 1°C, 75% ± 5% relative humidity, with a 12 h photoperiod within the Veterinary Isolation Facility BSL3 Insectary at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. All samples were screened by plaque assay on Vero cells.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA). Fisher’s exact test was used to determine significant differences in vector competence between viruses in each tissue at each timepoint. For survival analysis, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed by the log-rank test. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons was used to determine differences in viremia, brain viral loads and titers, and relative transcript abundance between virus groups.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities BSL3 Program for facilities and Neal Heuss for support.

This work was supported by NIH grants R21AI131454 and R01AI132563. A.S.J. was supported by T32 AI083196 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. The Wisconsin National Primate Research Center is supported by grants P51RR000167 and P51OD011106.

Contributor Information

Matthew T. Aliota, Email: mtaliota@umn.edu.

Anice C. Lowen, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

DATA AVAILABILITY

Raw Illumina sequencing data are available on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject no. PRJNA1009075.

ETHICS APPROVAL

This study was approved by the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol Number, 1804–35828).

REFERENCES

- 1. Lauring AS, Andino R. 2010. Quasispecies theory and the behavior of RNA viruses. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001005. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weaver SC. 2006. Evolutionary influences in arboviral disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 299:285–314. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26397-7_10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greene IP, Wang E, Deardorff ER, Milleron R, Domingo E, Weaver SC. 2005. Effect of alternating passage on adaptation of sindbis virus to vertebrate and Invertebrate cells. J Virol 79:14253–14260. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14253-14260.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Novella IS, Presloid JB, Smith SD, Wilke CO. 2011. Specific and nonspecific host adaptation during arboviral experimental evolution. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 21:71–81. doi: 10.1159/000332752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tsetsarkin KA, Vanlandingham DL, McGee CE, Higgs S. 2007. A single mutation in chikungunya virus affects vector specificity and epidemic potential. PLoS Pathog 3:e201. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tsetsarkin KA, Weaver SC. 2011. Sequential adaptive mutations enhance efficient vector switching by chikungunya virus and its epidemic emergence. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002412. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moudy RM, Meola MA, Morin LL, Ebel GD, Kramer LD. 2007. A newly emergent genotype of West Nile virus is transmitted earlier and more efficiently by Culex mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg 77:365–370. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2007.77.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brault AC, Powers AM, Holmes EC, Woelk CH, Weaver SC. 2002. Positively charged amino acid substitutions in the e2 envelope glycoprotein are associated with the emergence of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. J Virol 76:1718–1730. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.4.1718-1730.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rossi SL, Ebel GD, Shan C, Shi PY, Vasilakis N. 2018. Did Zika virus mutate to cause severe outbreaks? Trends Microbiol 26:877–885. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jaeger AS, Murrieta RA, Goren LR, Crooks CM, Moriarty RV, Weiler AM, Rybarczyk S, Semler MR, Huffman C, Mejia A, Simmons HA, Fritsch M, Osorio JE, Eickhoff JC, O’Connor SL, Ebel GD, Friedrich TC, Aliota MT. 2019. Zika viruses of African and Asian lineages cause fetal harm in a mouse model of vertical transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13:e0007343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grubaugh ND, Ishtiaq F, Setoh YX, Ko AI. 2019. Misperceived risks of Zika-related microcephaly in India. Trends Microbiol 27:381–383. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2019.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oliveira G, Vogels CBF, Zolfaghari A, Saraf S, Klitting R, Weger-Lucarelli J, Leon PK, Ontiveros CO, Agarwal R, Tsetsarkin KA, Harris E, Ebel GD, Wohl S, Grubaugh ND, Andersen KG. 2023. Genomic and phenotypic analyses suggest moderate fitness differences among Zika virus lineages. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 17:e0011055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0011055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Allard A, Althouse BM, Hébert-Dufresne L, Scarpino SV. 2017. The risk of sustained sexual transmission of Zika is underestimated. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006633. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Magalhaes T, Foy BD, Marques ETA, Ebel GD, Weger-Lucarelli J. 2018. Mosquito-borne and sexual transmission of Zika virus: recent developments and future directions. Virus Res 254:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Magalhaes T, Morais CNL, Jacques I, Azevedo EAN, Brito AM, Lima PV, Carvalho GMM, Lima ARS, Castanha PMS, Cordeiro MT, Oliveira ALS, Jaenisch T, Lamb MM, Marques ETA, Foy BD. 2021. Follow-up household serosurvey in Northeast Brazil for Zika virus: sexual contacts of index patients have the highest risk for seropositivity. J Infect Dis 223:673–685. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riemersma KK, Jaeger AS, Crooks CM, Braun KM, Weger-Lucarelli J, Ebel GD, Friedrich TC, Aliota MT. 2021. Rapid evolution of enhanced Zika virus virulence during direct vertebrate transmission chains. J Virol 95:e02218-20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02218-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jaeger AS, Weiler AM, Moriarty RV, Rybarczyk S, O’Connor SL, O’Connor DH, Seelig DM, Fritsch MK, Friedrich TC, Aliota MT. 2020. Spondweni virus causes fetal harm in Ifnar1-/- mice and is transmitted by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Virology 547:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2020.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aliota MT, Peinado SA, Osorio JE, Bartholomay LC. 2016. Culex pipiens and Aedes triseriatus mosquito susceptibility to Zika virus. Emerg Infect Dis 22:1857–1859. doi: 10.3201/eid2210.161082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ngueyen TTN, Kim SJ, Lee JY, Myoung J. 2019. Zika virus proteins NS2A and NS4A are major antagonists that reduce IFN-Β promoter activity induced by the MDA5/RIG-I signaling pathway. J Microbiol Biotechnol 29:1665–1674. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1909.09017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ma J, Ketkar H, Geng T, Lo E, Wang L, Xi J, Sun Q, Zhu Z, Cui Y, Yang L, Wang P. 2018. Zika virus non-structural protein 4A blocks the RLR-MAVS signaling. Front Microbiol 9:1350. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gao Z, Zhang X, Zhang L, Wu S, Ma J, Wang F, Zhou Y, Dai X, Bullitt E, Du Y, Guo JT, Chang J. 2022. A yellow fever virus NS4B inhibitor not only suppresses viral replication, but also enhances the virus activation of RIG-I-like receptor-mediated innate immune response. PLoS Pathog 18:e1010271. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Daffis S, Samuel MA, Keller BC, Gale M, Diamond MS. 2007. Cell-specific IRF-3 responses protect against West Nile virus infection by interferon-dependent and -independent mechanisms. PLoS Pathog 3:e106. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suthar MS, Brassil MM, Blahnik G, McMillan A, Ramos HJ, Proll SC, Belisle SE, Katze MG, Gale M. 2013. A systems biology approach reveals that tissue tropism to West Nile virus is regulated by antiviral genes and innate immune cellular processes. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003168. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ren Z, Ding T, Zuo Z, Xu Z, Deng J, Wei Z. 2020. Regulation of MAVS expression and signaling function in the antiviral innate immune response. Front Immunol 11:1030. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Daniels BP, Klein RS, Dutch RE. 2015. Knocking on closed doors: host interferons dynamically regulate blood-brain barrier function during viral infections of the central nervous system. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005096. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ida-Hosonuma M, Iwasaki T, Yoshikawa T, Nagata N, Sato Y, Sata T, Yoneyama M, Fujita T, Taya C, Yonekawa H, Koike S. 2005. The alpha/beta interferon response controls tissue tropism and pathogenicity of poliovirus. J Virol 79:4460–4469. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4460-4469.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shen FH, Tsai CC, Wang LC, Chang KC, Tung YY, Su IJ, Chen SH. 2013. Enterovirus 71 infection increases expression of interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 which protects mice by reducing viral burden in multiple tissues. J Gen Virol 94:1019–1027. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.046383-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Plociennikowska A, Frankish J, Moraes T, Del Prete D, Kahnt F, Acuna C, Slezak M, Binder M, Bartenschlager R. 2021. TLR3 activation by Zika virus stimulates inflammatory cytokine production which dampens the antiviral response induced by RIG-I-like receptors. J Virol 95:e01050-20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01050-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ojha CR, Rodriguez M, Karuppan MKM, Lapierre J, Kashanchi F, El-Hage N. 2019. Toll-like receptor 3 regulates Zika virus infection and associated host inflammatory response in primary human astrocytes. PLoS One 14:e0208543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Daffis S, Samuel MA, Suthar MS, Gale M, Diamond MS. 2008. Toll-like receptor 3 has a protective role against West Nile virus infection. J Virol 82:10349–10358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00935-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang T, Town T, Alexopoulou L, Anderson JF, Fikrig E, Flavell RA. 2004. Toll-like receptor 3 mediates West Nile virus entry into the brain causing lethal encephalitis. Nat Med 10:1366–1373. doi: 10.1038/nm1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deardorff ER, Fitzpatrick KA, Jerzak GVS, Shi PY, Kramer LD, Ebel GD. 2011. West Nile virus experimental evolution in vivo and the trade-off hypothesis. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002335. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ciota AT, Jia Y, Payne AF, Jerzak G, Davis LJ, Young DS, Ehrbar D, Kramer LD. 2009. Experimental passage of St. Louis encephalitis virus in vivo in mosquitoes and chickens reveals evolutionarily significant virus characteristics. PLoS One 4:e7876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ávila-Pérez G, Nogales A, Park JG, Márquez-Jurado S, Iborra FJ, Almazan F, Martínez-Sobrido L. 2019. A natural polymorphism in Zika virus NS2A protein responsible of virulence in mice. Sci Rep 9:19968. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-56291-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Muñoz-Jordan JL, Sánchez-Burgos GG, Laurent-Rolle M, García-Sastre A. 2003. Inhibition of interferon signaling by dengue virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:14333–14338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335168100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Klaitong P, Smith DR. 2021. Roles of non-structural protein 4A in Flavivirus infection. Viruses 13:2077. doi: 10.3390/v13102077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pierson TC, Diamond MS. 2020. The continued threat of emerging flaviviruses. Nat Microbiol 5:796–812. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0714-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Miller S, Kastner S, Krijnse-Locker J, Bühler S, Bartenschlager R. 2007. The non-structural protein 4A of dengue virus is an integral membrane protein inducing membrane alterations in a 2K-regulated manner. J Biol Chem 282:8873–8882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609919200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Teo CSH, Chu JJH. 2014. Cellular vimentin regulates construction of dengue virus replication complexes through interaction with NS4A protein. J Virol 88:1897–1913. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01249-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McLean JE, Wudzinska A, Datan E, Quaglino D, Zakeri Z. 2011. Flavivirus NS4A-induced autophagy protects cells against death and enhances virus replication. J Biol Chem 286:22147–22159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.192500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liang Q, Luo Z, Zeng J, Chen W, Foo SS, Lee S-A, Ge J, Wang S, Goldman SA, Zlokovic BV, Zhao Z, Jung JU. 2016. Zika virus NS4A and NS4B proteins deregulate Akt-mTOR signaling in human fetal neural stem cells to inhibit neurogenesis and induce autophagy. Cell Stem Cell 19:663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stern O, Hung YF, Valdau O, Yaffe Y, Harris E, Hoffmann S, Willbold D, Sklan EH. 2013. An N-terminal Amphipathic Helix in Dengue virus Nonstructural protein 4A mediates Oligomerization and is essential for replication. J Virol 87:4080–4085. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01900-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee CM, Xie X, Zou J, Li SH, Lee MYQ, Dong H, Qin CF, Kang C, Shi PY. 2015. Determinants of dengue virus NS4A protein oligomerization. J Virol 89:6171–6183. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00546-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ambrose RL, Mackenzie JM. 2015. Conserved amino acids within the N-terminus of the West Nile virus NS4A protein contribute to virus replication, protein stability and membrane proliferation. Virology 481:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lindenbach BD, Rice CM. 1999. Genetic interaction of flavivirus nonstructural proteins NS1 and NS4A as a determinant of replicase function. J Virol 73:4611–4621. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.6.4611-4621.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. da Conceição TM, Rust NM, Berbel A, Martins NB, do Nascimento Santos CA, Da Poian AT, de Arruda LB. 2013. Essential role of RIG-I in the activation of endothelial cells by dengue virus. Virology 435:281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Carty M, Reinert L, Paludan SR, Bowie AG. 2014. Innate antiviral signalling in the central nervous system. Trends Immunol 35:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Blank T, Prinz M. 2017. Type I interferon pathway in CNS homeostasis and neurological disorders. Glia 65:1397–1406. doi: 10.1002/glia.23154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Major J, Crotta S, Llorian M, McCabe TM, Gad HH, Priestnall SL, Hartmann R, Wack A. 2020. Type I and III Interferons disrupt lung epithelial repair during recovery from viral infection. Science 369:712–717. doi: 10.1126/science.abc2061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Quicke KM, Diamond MS, Suthar MS. 2017. Negative regulators of the RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway. Eur J Immunol 47:615–628. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rajsbaum R, García-Sastre A, Versteeg GA. 2014. TRIMmunity: the roles of the TRIM E3-ubiquitin ligase family in innate antiviral immunity. J Mol Biol 426:1265–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Deddouche S, Matt N, Budd A, Mueller S, Kemp C, Galiana-Arnoux D, Dostert C, Antoniewski C, Hoffmann JA, Imler JL. 2008. The DExD/H-box Helicase Dicer-2 mediates the induction of antiviral activity in drosophila. Nat Immunol 9:1425–1432. doi: 10.1038/ni.1664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Paradkar PN, Trinidad L, Voysey R, Duchemin JB, Walker PJ. 2012. Secreted Vago restricts West Nile virus infection in Culex mosquito cells by activating the Jak-STAT pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:18915–18920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205231109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gao J, Zhao BR, Zhang H, You YL, Li F, Wang XW. 2021. Interferon functional analog activates antiviral Jak/Stat signaling through integrin in an arthropod. Cell Rep 36:109761. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Asad S, Parry R, Asgari S. 2018. Upregulation of Aedes aegypti Vago1 by Wolbachia and its effect on dengue virus replication. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 92:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2017.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sanchez David RY, Combredet C, Najburg V, Millot GA, Beauclair G, Schwikowski B, Léger T, Camadro JM, Jacob Y, Bellalou J, Jouvenet N, Tangy F, Komarova AV. 2019. LGP2 binds to PACT to regulate RIG-I- and MDA5-mediated antiviral responses. Sci Signal 12:eaar3993. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aar3993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Satoh T, Kato H, Kumagai Y, Yoneyama M, Sato S, Matsushita K, Tsujimura T, Fujita T, Akira S, Takeuchi O. 2010. LGP2 is a positive regulator of RIG-I- and MDA5-mediated antiviral responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:1512–1517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912986107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vignuzzi M, Stone JK, Arnold JJ, Cameron CE, Andino R. 2006. Quasispecies diversity determines pathogenesis through cooperative interactions in a viral population. Nature 439:344–348. doi: 10.1038/nature04388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Caldwell HS, Lasek-Nesselquist E, Follano P, Kramer LD, Ciota AT. 2020. Divergent mutational landscapes of consensus and minority genotypes of West Nile virus demonstrate host and gene-specific evolutionary pressures. Genes (Basel) 11:1299. doi: 10.3390/genes11111299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jerzak G, Bernard KA, Kramer LD, Ebel GD. 2005. Genetic variation in West Nile virus from naturally infected mosquitoes and birds suggests quasispecies structure and strong purifying selection. J Gen Virol 86:2175–2183. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81015-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Aliota MT, Dudley DM, Newman CM, Weger-Lucarelli J, Stewart LM, Koenig MR, Breitbach ME, Weiler AM, Semler MR, Barry GL, Zarbock KR, Haj AK, Moriarty RV, Mohns MS, Mohr EL, Venturi V, Schultz-Darken N, Peterson E, Newton W, Schotzko ML, Simmons HA, Mejia A, Hayes JM, Capuano S, Davenport MP, Friedrich TC, Ebel GD, O’Connor SL, O’Connor DH. 2018. Molecularly barcoded Zika virus libraries to probe in vivo evolutionary dynamics. PLoS Pathog 14:e1006964. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pijlman GP, Funk A, Kondratieva N, Leung J, Torres S, van der Aa L, Liu WJ, Palmenberg AC, Shi PY, Hall RA, Khromykh AA. 2008. A highly structured, nuclease-resistant, noncoding RNA produced by flaviviruses is required for pathogenicity. Cell Host Microbe 4:579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Roby JA, Pijlman GP, Wilusz J, Khromykh AA. 2014. Noncoding sSubgenomic flavivirus RNA: multiple functions in West Nile virus pathogenesis and modulation of host responses. Viruses 6:404–427. doi: 10.3390/v6020404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Göertz GP, van Bree JWM, Hiralal A, Fernhout BM, Steffens C, Boeren S, Visser TM, Vogels CBF, Abbo SR, Fros JJ, Koenraadt CJM, van Oers MM, Pijlman GP. 2019. Subgenomic flavivirus RNA binds the mosquito DEAD/H-box helicase ME31B and determines Zika virus transmission by Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:19136–19144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905617116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Slonchak A, Khromykh AA. 2018. Subgenomic flaviviral RNAs: what do we know after the first decade of research. Antiviral Res 159:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Manokaran G, Finol E, Wang C, Gunaratne J, Bahl J, Ong EZ, Tan HC, Sessions OM, Ward AM, Gubler DJ, Harris E, Garcia-Blanco MA, Ooi EE. 2015. Dengue subgenomic RNA binds TRIM25 to inhibit interferon expression for epidemiological fitness. Science 350:217–221. doi: 10.1126/science.aab3369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bates TA, Chuong C, Hawks SA, Rai P, Duggal NK, Weger-Lucarelli J. 2021. Development and characterization of infectious clones of two strains of Usutu virus. Virology 554:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2020.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Marano J, Cereghino C, Finkielstein C, Weger-Lucarelli J. 2022. An in vitro workflow to create and modify novel infectious clones using replication cycle reaction. In Review. In Review, In review. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1894417/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69. Lauck M, Switzer WM, Sibley SD, Hyeroba D, Tumukunde A, Weny G, Taylor B, Shankar A, Ting N, Chapman CA, Friedrich TC, Goldberg TL, O’Connor DH. 2013. Discovery and full genome characterization of two highly divergent simian immunodeficiency viruses infecting black-and-white colobus monkeys (Colobus guereza) in Kibale National Park, Uganda. Retrovirology 10:107. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Quick J, Grubaugh ND, Pullan ST, Claro IM, Smith AD, Gangavarapu K, Oliveira G, Robles-Sikisaka R, Rogers TF, Beutler NA, Burton DR, Lewis-Ximenez LL, de Jesus JG, Giovanetti M, Hill SC, Black A, Bedford T, Carroll MW, Nunes M, Alcantara LC, Sabino EC, Baylis SA, Faria NR, Loose M, Simpson JT, Pybus OG, Andersen KG, Loman NJ. 2017. Multiplex PCR method for MinION and Illumina sequencing of Zika and other virus genomes directly from clinical samples. Nat Protoc 12:1261–1276. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Grubaugh ND, Gangavarapu K, Quick J, Matteson NL, De Jesus JG, Main BJ, Tan AL, Paul LM, Brackney DE, Grewal S, Gurfield N, Van Rompay KKA, Isern S, Michael SF, Coffey LL, Loman NJ, Andersen KG. 2019. An amplicon-based sequencing framework for accurately measuring Intrahost virus diversity using PrimalSeq and iVar. Genome Biol 20:8. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1618-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Christensen BM, Sutherland DR. 1984. Brugia pahangi: exsheathment and midgut penetration in Aedes aegypti. Trans Am Microsc Soc 103:423. doi: 10.2307/3226478 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Rutledge LC, Ward RA, Gould D. 1964. Studies on the feeding response of mosquitoes to nutritive solutions in a new membrane feeder. Mosq News 24:407–409. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Aliota MT, Peinado SA, Velez ID, Osorio JE. 2016. The wMel strain of Wolbachia reduces transmission of Zika virus by Aedes aegypti. Sci Rep 6:28792. doi: 10.1038/srep28792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Dudley DM, Newman CM, Lalli J, Stewart LM, Koenig MR, Weiler AM, Semler MR, Barry GL, Zarbock KR, Mohns MS, Breitbach ME, Schultz-Darken N, Peterson E, Newton W, Mohr EL, Capuano Iii S, Osorio JE, O’Connor SL, O’Connor DH, Friedrich TC, Aliota MT. 2017. Infection via mosquito bite alters Zika virus tissue tropism and replication kinetics in rhesus macaques. Nat Commun 8:2096. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02222-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw Illumina sequencing data are available on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject no. PRJNA1009075.