Abstract

The toxic effects of modified Fenton reactions on Xanthobacter flavus FB71, measured as microbial survival rates, were determined as part of an investigation of simultaneous abiotic and biotic oxidations of xenobiotic chemicals. A central composite, rotatable experimental design was developed to study the survival rates of X. flavus under various concentrations of hydrogen peroxide and iron(II) and at different initial cell populations. A model based on the experimental results, relating microorganism survival to the variables of peroxide, iron, and cellular concentrations was formulated and fit the data reasonably well, with a coefficient of determination of 0.76. The results of this study indicate that the use of simultaneous abiotic and biotic processes for the treatment of xenobiotic compounds may be possible.

Abiotic-biotic processes, used for the destruction of recalcitrant compounds in industrial effluents and contaminated sites, have been the subject of recent research (1, 5, 6, 11, 25, 26, 35, 38). In all of these studies, the authors investigated sequential processes by using an abiotic reaction as pretreatment for a separate, later biological reaction. One area of study that has received little attention, however, is the investigation of simultaneous abiotic and biotic transformation processes. Such coexisting reactions could have both economic and process advantages when applied to industrial pollution prevention schemes or to in situ remediation of hazardous wastes. One major limitation to combining these reactions simultaneously is the toxicity of elements of abiotic reactions to microorganisms. Therefore, as part of an overall coexisting abiotic-biotic transformation process study, we investigated the toxic effects of modified Fenton reactions, a common abiotic transformation process (27, 28, 31, 37, 44), on Xanthobacter flavus, a xenobiotic chemical-degrading microorganism.

The Fenton reaction, a widely used abiotic transformation process, is the catalyzed decomposition of hydrogen peroxide by transition metals, which results in the generation of hydroxyl radicals and other species such as superoxide and hydroperoxyl radicals (18, 19, 34). The standard Fenton procedure involves adding dilute hydrogen peroxide to a degassed solution of iron(II), which results in nearly stoichiometric generation of hydroxyl radicals. However, most environmental applications of Fenton chemistry have some modifications, including the use of higher concentrations of hydrogen peroxide, phosphate-buffered medium, iron(III), or heterogeneous catalysts. These conditions, although not as stoichiometrically efficient as those in the standard Fenton reaction, are often necessary to treat industrial waste streams (18) and sorbed contaminants in soils and groundwater (41).

Hydroxyl radicals generated by modified Fenton reactions react with most environmental contaminants at near diffusion-controlled rates (>109 M−1 s−1). The degradation of xenobiotic chemicals by hydroxyl radicals then proceeds via either hydroxylation or hydrogen atom abstraction: ·OH + R → ·ROH (1)·OH + RH2 → ·RH + H2O (2)

Many biorefractory compounds, such as perhalogenated alkenes, dienes, and benzenes (e.g., perchloroethylene, hexachlorocyclopentadiene, hexachlorobenzene), are effectively degraded by hydroxyl radicals within minutes (27, 37, 42). Based on these high transformation rates, there has been an increased interest in oxidation processes for soil and groundwater treatment.

Coexisting abiotic-biotic reactions may have application in in situ soil and groundwater remediation and could possibly occur during such efforts. Hydrogen peroxide, which is miscible and dissociates to oxygen and water, has been commonly used as an oxygen source for in situ bioremediation (9, 32, 33). However, in some instances, due to rapid dissociation of the hydrogen peroxide, oxygen transfer was found to be limited to the area close to the injection well. This quick dissociation was later attributed to microbial enzymatic activity and iron and copper salts present in the soil matrix (8, 9, 39). Data from Tyre et al. (41) and Watts et al. (43) suggest that naturally occurring iron oxyhydroxides can serve as effective Fenton catalysts. Fenton reactions, then, were probably taking place in the in situ bioremediation applications where hydrogen peroxide was being used to increase dissolved-oxygen concentrations. Additionally, interest in abiotic remediation technologies has led to the recent commercialization of modified Fenton reaction systems for use in situ (3). Both abiotic and bioremediation technologies may ultimately benefit from coexisting abiotic-biotic reactions.

The elements of Fenton reactions, such as hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals, and other radical species, are highly toxic to living organisms. The toxicity of the reactive oxygen species comes from their ability to oxidize a large number of cellular constituents. Toxicity mechanisms include DNA disruption (2, 40), oxidation of proteins and amino acids (7, 47), and lipid peroxidation of membrane fatty acids (30). While the toxicity of hydrogen peroxide to microorganisms has been the subject of many investigations (2, 10, 15, 20, 46), there has been no attempt to quantify the toxic effects of the radicals involved in modified Fenton reactions on similar biological systems.

The purpose of this research was to investigate the toxic effects of modified Fenton reactions on Xanthobacter flavus FB71, a hazardous-compound-degrading bacterium. Survival of bacterial populations was modeled statistically for various combinations of the treatment parameters: (i) H2O2 concentration, (ii) Fe(II) concentration, and (iii) initial cell number. The effect of treatment conditions on the activities of selected microbial enzymes was also determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial growth conditions and strain determination.

We isolated a strain of bacterium that utilized dichloroacetic acid from waste activated sludge of a sewage treatment plant in Pullman, Wash., as the sole carbon and energy source. Isolation and growth media contained, per liter of distilled water, 200 mg of dichloroacetic acid sodium salt (98%; Aldrich), 15 g of Noble Agar (Difco), 3.4 g of Na2HPO4, 1.5 g of KH2PO4, 0.25 g of NaCl, 0.5 g of NH4Cl, 0.12 g of MgSO4, 5.55 mg of CaCl2, 2 ml of Wolfe’s mineral solution (17), and 2 ml of vitamin supplement stock solution containing (per liter) 50 mg each of biotin, thiamine HCl, and nicotinic acid (Sigma). The organism was identified, with a similarity index of 0.909, as X. flavus by cell wall fatty acid analysis (Acculab).

Following microbial isolation, the carbon source within the above defined growth medium (minus Noble Agar) was switched to pyruvic acid sodium salt (98%; Aldrich) to promote rapid growth. A number of authors have reported that the appearance of the microbial enzymes involved in the detoxification of reactive oxygen species is dependent upon the timing within the growth stage (22, 23, 29, 36, 45). Therefore, to ensure the consistency of harvested cells and enzyme activities, cells were grown in a 1.5-liter volume at steady state in a continuous-flow chemostat (New Brunswick Scientific BioFlo-III) with 1.0 liter of fresh growth medium per day at 30°C and with stirring at 200 rpm and aerated with 3 liters of sterile air per min.

H2O2 acclimation.

Cells were acclimated to high levels of H2O2 (Fisher Scientific) under similar chemostat-growth conditions to those detailed above, with the addition of increasing concentrations of peroxide. The H2O2 was added to the fresh medium during operation of the chemostat at concentrations of 100 mg/liter for the first day, 200 mg/liter for the second day, and 300 mg/liter for the third day. After the third day, the medium was maintain at an H2O2 concentration of 300 mg/liter.

Cell extracts.

Cells harvested from the chemostat were recovered by centrifuging at 4°C and 10,000 × g for 10 min with a Beckman centrifuge (model J2-MC). The cells were resuspended in 0.05 M phosphate buffer and then lysed by being passed through a French press three times under cell pressure of 11,000 lb/in2. Debris-free extracts were obtained by centrifuging the lysate at 4°C and 15,000 × g for 30 min and recovering the supernatant, which was used for protein and enzyme analyses.

Protein assay.

Total cellular protein was assayed spectrophotometrically (Hewlett-Packard model 8453) by monitoring the shift of maximum absorbance from 465 to 595 nm as the Brilliant blue G-250 dye bound to protein (Bio-Rad) (4).

Enzyme assays.

Catalase, peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzymes were assayed spectrophotometrically (Hewlett-Packard model 8453) by the methods described in the Worthington Enzyme Manual (48). The catalase activity was assayed by monitoring the disappearance of hydrogen peroxide at 240 nm. One unit of catalase activity was defined as the decomposition of 1 μM H2O2 per min at 25°C and pH 7.0. The peroxidase activity assay was based on the absorbance increase at 510 nm resulting from the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide with 4-aminoantipyrine used as a hydrogen donor. One unit of peroxidase activity resulted in the decomposition of 1 μM H2O2 per min at 25°C and pH 7.0. The SOD activity was assayed by monitoring the inhibition of the reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium at 540 nm. One unit was defined as the amount of enzyme causing half-maximal inhibition of nitroblue tetrazolium reduction. The unit activities of the enzymes were normalized as specific activities by using the total cellular protein assay.

Toxicity study.

Toxicity studies were performed by enumerating the cells after incubation in 40 ml of medium (as described above minus carbon and nitrogen), containing Fe(II), H2O2, and cells at the concentrations given in Table 1. Cultures were placed on a rotary platform shaker at 30°C and 200 rpm for 60 min. Hydrogen peroxide was added to the medium first, followed by cells that had been harvested from the steady-state chemostat. The concentrations of harvested cells were determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (0.1 unit ≅ 108 cells/ml), and the medium was diluted accordingly to obtain the desired initial cell populations. The experiments were initiated by the addition of a previously prepared ferrous iron stock solution. The ferrous iron stock solution (40 mM) was prepared in the presence of excess chelating agent, i.e., 400 mM nitriloacetic acid (NTA), and under anaerobic conditions to prevent autooxidation of the ferrous iron to ferric iron (13).

TABLE 1.

Experimental matrix for the investigation of response surfaces describing the toxic effects of modified Fenton reactions on X. flavus by measuring organism survival considering the experimental variables of hydrogen peroxide, iron(II), and cell population

| Block | Expt | H2O2 concn (mg/liter) | Fe(II) concn (mM) | No. of cells (log10) | Observed survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 60 | 2 | 3.0 | 71.4 |

| 2 | 240 | 2 | 3.0 | 52.5 | |

| 3 | 60 | 8 | 3.0 | 56.6 | |

| 4 | 240 | 8 | 3.0 | 33.0 | |

| 5 | 60 | 2 | 6.0 | 54.9 | |

| 6 | 240 | 2 | 6.0 | 44.1 | |

| 7 | 60 | 8 | 6.0 | 42.9 | |

| 8 | 240 | 8 | 6.0 | 26.0 | |

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 4.5 | 41.5 |

| 2 | 300 | 5 | 4.5 | 40.3 | |

| 3 | 150 | 0 | 4.5 | 76.6 | |

| 4 | 150 | 10 | 4.5 | 33.1 | |

| 5 | 150 | 5 | 2.0 | 36.2 | |

| 6 | 150 | 5 | 7.0 | 2.0 | |

| 3 | 1 | 150 | 5 | 4.5 | 28.6 |

| 2 | 150 | 5 | 4.5 | 23.4 | |

| 3 | 150 | 5 | 4.5 | 27.9 | |

| 4 | 150 | 5 | 4.5 | 45.2 | |

| 5 | 150 | 5 | 4.5 | 42.0 | |

| 6 | 150 | 5 | 4.5 | 20.7 |

Cell populations were enumerated at the end of the toxicity studies by the spread plate technique with nutrient agar (24). Tenfold serial dilutions prior to plate spreading were made in the carbon- and nitrogen-free growth medium. Such sample handling eliminated the need for pretreatment of cells since any adverse effects of the sampled media or carryover of the chemicals were decreased substantially by dilution.

Experimental design.

Toxicity experiments were based on a central composite, rotatable design as outlined by Cochran and Cox (12) to decrease the number of experiments while increasing the statistical significance of the results. The three-level design, shown in Table 1, included the initial cell population and H2O2 and Fe(II)-chelate concentrations as experimental variables. The percent cellular survival, based on spread plate enumerations, was the response measured. The design contained three blocks of experiments based on a second-order design: Block 1 was a 23 factorial design that formed the first-order portion of the design; block 2 was the “star” points that provided the second-order portion of the design; and block 3 was defined as the center of the experimental design, which allowed analysis of the error of the measurements.

Response surface methodology is a technique used to demonstrate the effects of independent variables on an experimental response. The method allows researchers to analyze the effects of multiple variables with a minimal number of experiments while keeping statistical significance (12) and has gained popularity as an effective research tool. Hess et al. (21) used the technique to investigate the effects of process variables on dissolved-oxygen removal from a water treatment technology, while Watts et al. (42) demonstrated the effects of treatment variables on remediation of hexachlorobenzene-contaminated soils.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Adaptation to H2O2 stress.

The purpose of our research was to investigate the toxic effects of modified Fenton reactions on bacteria, rather than the effects of hydrogen peroxide, which is itself toxic to microorganisms. Conversely, it has been well established that microorganisms can be acclimated to high concentrations of H2O2 by pretreatment with sublethal concentrations (15, 22, 46). Therefore, to eliminate the toxic effects of H2O2, we initially acclimated cells to high concentrations of H2O2.

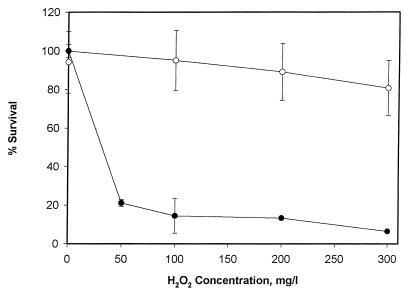

The effect of H2O2 acclimation was investigated by comparing the survival rates of acclimated and nonacclimated cells in the medium used for the toxicity study after 1 h of incubation with various concentrations of H2O2. The H2O2-acclimated cells showed high survival rates (>80%), while nonacclimated cells showed high susceptibility to H2O2 stress (Fig. 1), with an overall decline in cell number of more than 90%. During this study, it was observed that the time required to produce replicates from the same dilution significantly decreased the number of colonies formed for the nonacclimated cells. This situation, while resulting in a high standard deviation from the mean for final cell populations, affected neither the percent survival rate nor its standard deviation. A similar phenomenon was not encountered for the acclimated strain.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of survival rates of H2O2-acclimated (○) and nonacclimated (•) cells of X. flavus for various H2O2 concentrations after 1 h of incubation. Error bars represent standard errors of measurements.

We also investigated the effect of H2O2 acclimation on cellular enzyme activity. Although there were a number of possible enzymes that might be involved in the detoxification of H2O2, we selected the three most likely enzymes: catalase, SOD, and peroxidase. The results, summarized in Table 2, show the effect of H2O2 acclimation on these three enzymes. No measurable peroxidase activity was observed in either the H2O2-acclimated or nonacclimated cells. However, adaptation by feeding the chemostat with medium containing 300 mg of H2O2 per liter resulted in an approximately 23-fold increase in the specific activity of catalase, whereas the specific activity of SOD increased less than 2-fold. Izawa et al. (22) obtained similar results for catalase induction due to H2O2 acclimation.

TABLE 2.

Enzyme activity changes resulting from H2O2 acclimation of X. flavus

| Enzyme | Activity (U/mg) in:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| H2O2-acclimated strain | Unacclimated strain | |

| Catalase | 216.1 | 9.4 |

| SOD | 11.6 | 6.2 |

| Peroxidase | 0.0 | 0.0 |

The large increase in the specific activity of catalase demonstrates its role in H2O2 adaptation. The elevated survival rate of H2O2-acclimated cells in the presence of H2O2 is evidence of successful acclimation to H2O2, a necessary step for the following experiments.

Toxic effects of modified Fenton reactions.

The toxic effects of Fenton reactions on microorganisms results from H2O2, ·OH, and other reactive oxygen species. Because our goal was to investigate the toxic effects of only radical species generated via modified Fenton reactions, H2O2-acclimated cells were used throughout the experiments. The toxic effects were investigated as a function of initial cell population and both reaction elements, i.e., H2O2 and Fe(II). Experiments were based on a central composite, rotatable design (12), chosen to minimize the number of experiments while keeping a high degree of statistical significance in the results. The experimental design, with all calculated H2O2 and Fe(II) concentrations and cell population values, together with resulting cellular survival (as a percentage), is shown in Table 1.

Analyses of the experimental results, by a second-order equation, (12, 14) resulted in the following quadratic equation of the response surface for the percent cellular survival with the three variables of H2O2, Fe(II), and initial cell population: S = 122.6892 (±15.0632) − 0.251 × H (±0.1033) − 14.7437 × F (±3.0993) − 5.1721 × C (±1.1721) + 0.0006 × H2 (±0.0003) + 1.1315 × F2 (±0.2961), where S is percent cellular survival, H is H2O2 concentration (milligrams per liter), F is Fe(II) concentration (millimolar), and C is the initial cell population (log10 per milliliter). Numbers in parentheses are uncertainties (95% confidence level) associated with each variable in the model. The terms that were determined by a t test (14) as being insignificant at a P of 0.10 were excluded from the equation. The above equation was given with four significant figures because of the drastic effect on the model due to the H2 term. It should be noted that experiment 7, block 1 (Table 1), was rerun due to an experimental error, yet a sensitivity analysis on the point showed that the results of experiment 7 had an insignificant effect on the overall model equation (data not shown). Finally, it should be remembered that the validity of the model is limited to use within the tested boundaries.

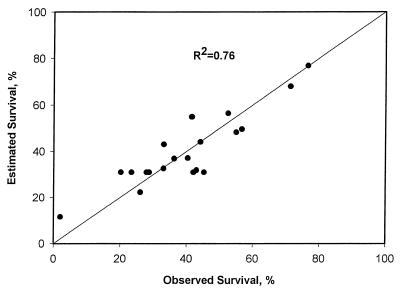

The statistical analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the data is shown in Table 3 (14). Regression of the experimental data values against estimated values from the model was performed and is shown in Fig. 2. The corresponding coefficient of correlation (R2) was 0.76, an acceptable value when considering the errors inherent in enumeration of microbial populations. Furthermore, based on ANOVA of the results (Fig. 2; Table 3), the second-order response equation appeared to adequately fit the data: comparison of the mean squares for lack of fit and error terms (Table 3) showed values of approximately equal size, indicating adequate model fit (12).

TABLE 3.

ANOVA results from the statistical analysis of the second-order response surface model

| Term | No. of degrees of freedom | Sum of squares | Mean square |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-order terms | 3 | 2,620.70 | 873.57 |

| Second-order terms | 6 | 2,019.94 | 336.66 |

| Lack of fit | 5 | 575.06 | 115.01 |

| Error | 5 | 513.43 | 102.69 |

FIG. 2.

Regression plot of observed data values against estimated values from the second-order response surface model.

The utility of any response surface model for describing a biological system comes from its ability to accurately predict the response. Our proposed model was shown to accurately predict observed values from the experimental design, based on the coefficient of determination statistic. The model also appeared valid in describing observed values from the separate experiment in Fig. 1. When these data were added to those in Fig. 2, the plot of observed survival against predicted survival, they fit within the overall experimental error and actually increased the coefficient of determination to 0.83 from 0.76 (data not shown).

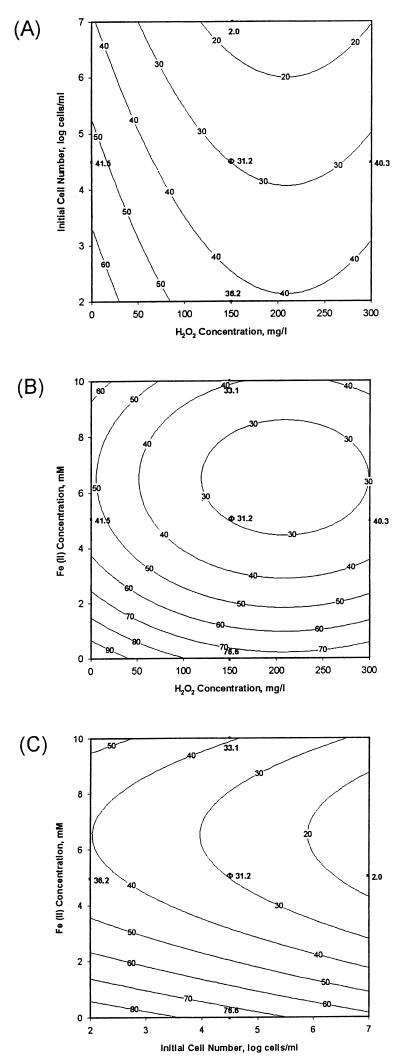

Response surface plots of the second-order model, generated by keeping one of the variables constant at the center point of the experimental design, are shown in Fig. 3, along with discrete data values. As can be seen in the plots, there was a decline in cellular survival with increasing hydrogen peroxide and Fe(II) concentrations. This was to be expected, since the extent of formation of products of Fenton reactions was dependent on the concentrations of both species (13). A further observation was the apparent anomaly of lowered bacterial survival with increasing initial cell number for similar peroxide concentrations, as seen in Fig. 3A and C. This, too, can be explained if the cell number is thought of as another reactive species with Fenton reaction products, and then high cell concentrations lead to high reaction rates, or cellular death, and low survival percentages. If coexisting abiotic-biotic processes are to be used for treatment purposes, a significant number of cells must be present to effect a useful kinetic degradation rate. Even though the experiment with an initial cell count of 107/ml (block 2, experiment 6 [Table 1]) showed only 2% survival, the remaining 2 × 105 cells/ml may be enough for a successful abiotic-biotic remediation scheme.

FIG. 3.

Response surface plots for percent microbial survival (contour lines) under different experimental conditions. (A) Ferrous iron concentration of 5 mM. (B) Initial cell number of 104.5 cells/ml. (C) Hydrogen peroxide concentration of 150 mg/liter. Symbols: ∗, observed data; Φ, mean value for center point data.

The results (Fig. 3B and C) showed that the addition of Fe(II) decreased cellular survival rates. Addition of ferrous iron to the reaction mixture resulted in the generation of various oxygen radical species, especially hydroxyl radicals, which were more reactive than H2O2. The first-order reaction rates of catalase with H2O2 and hydroxyl radicals are 1.7 × 107 and >1 × 1010 M−1 s−1, respectively (19). Although the primary detoxification enzyme involved in both cases was catalase (47), the increased toxicity seen in our experiments may be explained by the increased reactivity of products of Fenton reactions.

Data from Fig. 3A and B show that the elevated hydrogen peroxide concentrations resulted in higher survival rates. This phenomenon may be attributed to (i) experimental errors (the increases in survival rates are within the experimental error range) or (ii) the formation of other reactive oxygen species, in the presence of excess hydrogen peroxide, which are possibly less toxic or can be detoxified by enzymatic means other than by catalase. Pignatello and Sun (34) showed that ferric iron catalyzed excess hydrogen peroxide, yielding water, oxygen and hydroperoxyl radical (equations 3 to 6). Halliwell and Gutteridge (19) reported another possible reaction between ferric iron and hydrogen peroxide, yielding superoxide radical (equation 7), readily detoxified in microorganisms by SOD.

|

3 |

|

4 |

|

5 |

|

6 |

|

7 |

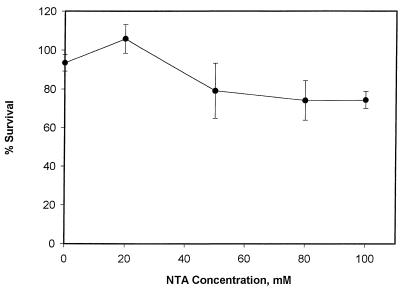

Another observation from this study concerned the possible toxicity of Fe(II)-NTA. Figure 3 shows that there was still significant toxicity in the absence of H2O2 and that it was attributable to either (i) in vivo generation of H2O2 during the reduction of molecular oxygen (16, 33), with concomitant generation of hydroxyl or other oxygen radicals, or (ii) high concentrations of NTA. Therefore, we further investigated the possible contribution of NTA to the observed results of the study of the toxic effects of the products of the Fenton reaction. To this extent, cells were exposed to NTA for 1 h under the same conditions at which the toxic effects of the Fenton reaction were investigated. The results (Fig. 4) showed that high NTA concentrations may have contributed up to 25% of the overall toxic effects of Fenton reactions when the Fe(II) concentration was 10 mM.

FIG. 4.

Effect of various concentrations of NTA on the survival rates of X. flavus after 1 h of exposure. Error bars represent standard errors of measurements.

In conclusion, the results of this research showed that there are toxic effects of Fenton reactions on peroxide-acclimated bacteria that are exclusive of the toxicity of any of the individual reactants. These toxic effects was attributed in this study to the production of hydroxyl and other oxygen radicals. The cellular protective mechanism against peroxide and oxygen radical toxicity was shown to be an increase in catalase activity. Finally, a model describing toxicity, as related to cellular survival, was developed on the basis of concentrations of Fenton reaction species and initial cell number. The model was shown to be a statistically significant description of the process and could be used to predict the survival of the bacteria within the ranges of variables used. The results of this research indicate that coexisting abiotic-biotic processes may be possible, in part, because of toxicity avoidance mechanisms in the bacteria. Although applications of single bacterial strains are limited in practice, a single-strain system was selected based on the analytical simplifications to clearly elucidate the interactions between chemical and biological processes. Knowing how such chemical and biological processes interact will aid in subsequent development and optimization of coexisting abiotic-biotic processes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by National Science Foundation grant 9613258 from a joint program of the National Science Foundation and United States Environmental Protection Agency.

We thank A. Paszcynski for help with experimental procedures and A. L. Teel for thoughtful discussion.

Footnotes

Publication 98303 of the Idaho Agricultural Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anagiotou C, Papadopoulus A, Loizidou M. Leachate treatment by chemical and biological oxidation. J Environ Sci Health Part A. 1993;28:21–35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ananthaswamy H N, Eisenstark A. Repair of hydrogen peroxide-induced single-strand breaks in Escherichia coli deoxyribonucleic acid. J Bacteriol. 1977;130:187–191. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.1.187-191.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews, T., D. Zervas, and R. S. Greenberg. 1997. Oxidizing agent can finish cleanup where other systems taper off. Soil Groundwater Cleanup 1997 (July):39–42.

- 4.Bio-Rad Laboratories. Bio-Rad protein assay. Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.

- 5.Bowers A R, Cho S H, Singh A. Chemical oxidation of aromatic compounds: comparison of H2O2, KMnO4 and O3 for toxicity reduction and improvements. In: Eckenfelder W W, Bowers A R, Roth J A, editors. Biodegradability in chemical oxidation technologies for the nineties. Lancaster, Pa: Technomic Publishing Company; 1991. pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowers A R, Gaddipati P, Eckenfelder W W, Monsen R M. Treatment of toxic or refractory wastewaters with hydrogen peroxide. Water Sci Technol. 1989;21:477–486. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brot N, Weissbach L, Wearth J, Weissnach H. Enzymatic reduction of protein-bound methionine sulfoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:2155–2158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown R A, Norris R D. The evolution of a technology: hydrogen peroxide in in-situ bioremediation. In: Hinchee R E, Alleman B C, Hoeppel R E, Miller R N, editors. Hydrocarbon bioremediation. Boca Raton, Fla: Lewis Publishers; 1994. pp. 148–162. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown R A, Norris R D, Raymond R L. Proceedings of the NWWA/API Conference on Petroleum Hydrocarbons and Organic Chemicals in Groundwater. Prevention, detection and restoration. Worthington, Ohio: National Water Well Association; 1994. Oxygen transport in contaminated aquifers with hydrogen peroxide; pp. 441–450. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchmeier N A, Libby S J, Xu Y, Loewen P C, Switala J, Guiney D G. DNA repair is more important than catalase for Salmonella virulence in mice. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1047–1053. doi: 10.1172/JCI117750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carberry J B, Benzing T M. Peroxide pre-oxidation of recalcitrant toxic waste to enhance biodegradation. Water Sci Technol. 1991;23:367–376. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cochran W G, Cox G M. Experimental designs. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen G. The fenton reaction. In: Greenwald R A, editor. CRC handbook of methods for oxygen radical research. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1987. pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diamond W J. Practical experimental designs for engineers and scientists. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiorenza S, Ward C H. Microbial adaptation to hydrogen peroxide and biodegradation of aromatic hydrocarbons. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;18:140–151. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.2900322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fridovich I. The biology of oxygen radicals. Science. 1978;201:875–880. doi: 10.1126/science.210504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gherna R, Pienta P, Cote R. Catalogue of bacteria and phages. 18th ed. Rockville, Md: American Type Culture Collection; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haber F, Weiss J. The catalytic decomposition of hydrogen peroxide by iron salts. Proc R Soc London. 1934;147A:332–351. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halliwell B, Gutteridge J M C. Free radicals in biology and medicine. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassan H M, Fridovich I. Regulation of the synthesis of catalase and peroxidase in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:6445–6450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hess T F, Chwirka J D, Noble A M. Use of response surface modeling in pilot testing for design. Environ Technol. 1996;17:1205–1214. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izawa S, Inoue Y, Kimura A. Importance of catalase in the adaptive response to hydrogen peroxide: analysis of acatalasaemic Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biochem. 1996;320:61–67. doi: 10.1042/bj3200061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jamieson D J, Rivers S L, Stephen D W S. Analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteins induced by peroxide and superoxide stress. Microbiology. 1994;140:3277–3283. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-12-3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koch A. Growth measurement. In: Gerhardt P, Murray R G E, Wood W A, Krieg N R, editors. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 248–277. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koyama O, Kamagata Y, Nakamura K. Degradation of chlorinated aromatics by Fenton oxidation and methanogenic digester sludge. Water Res. 1994;28:885–899. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee S H, Carberry J B. Biodegradation of PCP enhanced by chemical oxidation pretreatment. Water Environ Res. 1992;64:682–690. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leung S W, Watts R J, Miller G C. Degradation of perchloroethylene by Fenton’s reagent: speciation and pathway. J Environ Qual. 1992;21:377–381. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z M, Shea P J, Comfort S D. Fenton oxidation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene in contaminated soil slurries. Environ Eng Sci. 1997;14:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loewen P C. Isolation of catalase-deficient Escherichia coli mutants and genetic mapping of katE, a locus that affects catalase activity. J Bacteriol. 1984;157:622–626. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.2.622-626.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mead J F. Free radical mechanisms of lipid damage and consequences for cellular membranes. In: Pryor W A, editor. Free radicals in biology. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1976. pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy A P, Boegli W J, Price M K, Moody C D. A Fenton-like reaction to neutralize formaldehyde waste solutions. Environ Sci Technol. 1989;23:166–169. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norris R D, Dowd K D. In situ bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soil and groundwater in a low permeability aquifer. In: Flathman P E, Jerger D E, Exner J H, editors. Bioremediation: field experience. Boca Raton, Fla: Lewis Publishers; 1994. pp. 457–474. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pardieck D L, Bouwer E J, Stone A T. Hydrogen peroxide use to increase oxidant capacity for in-situ bioremediation of contaminated soils and aquifers: a review. J Contam Hydrol. 1992;9:221–242. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pignatello J J, Sun Y. Photo-assisted mineralization of herbicide wastes by ferric ion catalyzed hydrogen peroxide. In: Tedder D W, Pohland F G, editors. Emerging technologies in hazardous waste management. III. Washington, D.C: American Chemical Society; 1993. pp. 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ravikumar J X, Gurol M D. Effectiveness of chemical oxidation to enhance the biodegradation of pentachlorophenol in soils: a laboratory study. In: Neufeld R D, Casson L W, editors. Hazardous and industrial wastes. Proceedings of the Twenty-Third Mid-Atlantic Industrial Waste Conference. Lancaster, Pa: Technomic Publishing Company; 1991. pp. 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sak B D, Eisenstark A, Touati D. Exonuclease III and the catalase hydroperoxidase II in Escherichia coli are both regulated by the katF gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3271–3275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato C, Leung S W, Bell H, Burkett W A, Watts R J. Decomposition of perchloroehylene and polychlorinated biphenyls with Fenton’s reagent. In: Tedder D W, Pohland F G, editors. Emerging technologies in hazardous waste management. III. Washington, D.C: American Chemical Society; 1993. pp. 343–356. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scott J P, Ollis D F. Integration of chemical and biological oxidation processes for water treatment: review and recommendations. Environ Prog. 1995;14:88–103. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spain J C, Milligan J D, Downey D C, Slaughter J K. Excessive bacterial decomposition of H2O2 during enhanced biodegradation. Ground Water. 1989;27:163–167. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Storz G, Christman M F, Sies H, Ames B N. Spontaneous mutagenesis and oxidative damage to DNA in Salmonela typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8917–8921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tyre B W, Watts R J, Miller G C. Treatment of four biorefractory contaminants in soils using catalyzed hydrogen peroxide. J Environ Qual. 1991;20:832–838. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watts R J, Kong S, Dipre M, Barnes W T. Oxidation of sorbed hexachlorobenzene in soils using catalyzed hydrogen peroxide. J Hazard Mater. 1994;39:33–47. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watts R J, Udell M D, Monsen R M. Use of iron minerals in optimizing the peroxide treatment of contaminates soils. Water Environ Res. 1993;65:839–844. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watts R J, Dilly S E. Evaluation of iron catalysts for the Fenton-like remediation of diesel-contaminated soils. J Hazard Mater. 1996;51:209–224. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Werner-Washburne M, Braun E, Johnston G C, Singer R A. Stationary phase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:383–401. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.383-401.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winquist L, Rannug U, Rannug A, Ramel C. Protection from toxic and mutagenic effects of H2O2 by catalase induction in Salmonella typhimurium. Mutat Res. 1984;141:145–147. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(84)90087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolff S P, Garner A, Dean R T. Free radicals, lipids and protein degradation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1986;11:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Worthington V. Worthington enzyme manual: enzymes and related biochemicals. Freehold, N.J: Worthington Biochemical Corp.; 1993. [Google Scholar]