Abstract

Introduction

Guselkumab previously showed greater improvements versus placebo in axial symptoms in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) (assessed by Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index [BASDAI] and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score [ASDAS]), in post hoc analyses of the phase 3, placebo-controlled, randomized DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 studies. We now evaluate durability of response in axial-related outcomes through 2 years of DISCOVER-2.

Methods

DISCOVER-2 biologic-naive adults with active PsA (≥ 5 tender/ ≥ 5 swollen joints, C-reactive protein ≥ 0.6 mg/dl) were randomized to guselkumab 100 mg every 4 weeks (Q4W) or at week 0, week 4, then Q8W, or placebo → guselkumab Q4W at week 24. Among patients with imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis (investigator-identified), axial symptoms were assessed through 2 years utilizing BASDAI, BASDAI Question #2 (spinal pain), modified BASDAI (mBASDAI; excludes Question #3 [peripheral joint pain]), and ASDAS. Mean changes in scores and proportions of patients achieving ≥ 50% improvement in BASDAI (BASDAI 50) and ASDAS responses, including major improvement (decrease ≥ 2.0), were determined through week 100. Treatment failure rules (through week 24) and nonresponder imputation of missing data (post-week 24) were utilized. Mean BASDAI component scores were assessed through week 100 (observed data). Exploratory analyses evaluated efficacy by sex and HLA-B*27 status.

Results

Among 246 patients with PsA and imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis, guselkumab-treated patients had greater mean improvements in BASDAI, mBASDAI, spinal pain, and ASDAS scores, lower mean BASDAI component scores, and greater response rates in achieving BASDAI 50 and ASDAS major improvement vs. placebo at week 24. Differences from placebo were observed for guselkumab-treated patients in selected endpoints regardless of sex or HLA-B*27 status. At week 100, mean improvements were ~ 3 points for all BASDAI scores and 1.6–1.7 for ASDAS; 49–54% achieved BASDAI 50 and 39% achieved ASDAS major improvement at week 100.

Conclusions

Guselkumab treatment provided durable and meaningful improvements in axial symptoms and disease activity in substantial proportions of patients with active PsA and imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis.

Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03158285.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-023-00592-8.

Keywords: Psoriatic arthritis, Axial, Biologics, Guselkumab

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Guselkumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits the interleukin-23 p19 subunit, demonstrated efficacy in improving the overall signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) in adults with active disease in the phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled DISCOVER-1 (1 year; tumor necrosis factor-inhibitor-naïve and -experienced) and DISCOVER-2 (2 years; biologic-naïve) studies. |

| In post hoc analyses of pooled patients with active PsA and imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis (identified by the investigator) from DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2, guselkumab-treated patients had greater improvements in symptoms of axial disease as assessed by least squares (LS) mean changes in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) at week 24 compared with placebo. |

| We further investigated the effect of guselkumab treatment on maintenance and extent of improvements in axial symptoms through 2 years in the DISCOVER-2 cohort of patients with imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis. |

| What was learned from this study? |

| Guselkumab-treated patients had greater LS mean improvements in total BASDAI, spinal pain (BASDAI Question #2), and ASDAS scores, as well as greater response rates for achieving ≥ 50% improvement in BASDAI and ASDAS responses (clinically important improvement, major improvement, and inactive disease) at week 24 vs. placebo; mean improvements and response rates for achieving stringent response criteria (determined using nonresponder imputation) were sustained through 1 and 2 years. |

| Exploratory analyses in HLA-B*27+ and HLA-B*27– patients showed separation from placebo for LS mean changes in BASDAI, spinal pain, modified BASDAI (excludes Question #3 [peripheral joint pain]), and ASDAS at week 24; changes in BASDAI scores tended to be numerically larger in HLA-B*27– patients, while results were similar between the subgroups when using the ASDAS. |

| Although limited by the small sample sizes, the treatment effect of guselkumab was consistent in both males and females, with increasing response rates for achievement of BASDAI 50 and ASDAS major improvement over time through 2 years. |

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic, heterogeneous, inflammatory disease characterized by peripheral arthritis, psoriatic skin and nail disease, axial inflammation, enthesitis, and dactylitis. Axial disease is a common manifestation, with a prevalence estimated at 5–28% in patients with early disease [1] and over 40% of those with established PsA [2]; approximately 5% of patients with PsA have axial symptoms exclusively [3]. Symptoms of axial PsA (axPsA) include inflammatory pain and stiffness in the neck and back [4] accompanied by sacroiliitis, spondylitis, and syndesmophytes detected using traditional radiographs [5] or evidence of active inflammation in the sacroiliac joints and/or spine when evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging [6]. Analyses from a US-based patient registry found that patients with PsA and axial involvement were more likely to have enthesitis and, on average, had more severe PsA and psoriasis, had greater impairments in health-related quality of life and work productivity, and higher rates of pain and depression compared with patients without axial involvement [7].

Patients with axPsA tend to be younger than 40 at age of onset [8, 9], with men and women affected equally [7]. The presence of the HLA-B*27 allele is a known risk factor in the development of PsA and earlier onset of arthritis [10], and along with radiographic damage in the peripheral joints, a positive HLA-B*27 status has been associated with an increased risk of developing axial inflammation [11]. However, the prevalence of HLA-B*27 is substantially lower among patients with PsA (approximately 20%) than in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) (approximately 80%) [10, 12]. The alleles HLA-B*08, HLA-B*38, and HLA-B*39 have also been specifically associated with the development of axPsA [1].

Identifying patients with axPsA and assessing axial disease activity in these patients are complicated by the lack of a consensus definition of axPsA as well as dedicated assessment tools. To date, axial symptoms in patients with PsA have typically been assessed using indices developed for patients with AS, such as the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) [13] and the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score employing C-reactive protein (CRP) (ASDAS) [14].

The interleukin (IL)-17/IL-23 pathway is a key contributor in the pathogenesis of PsA, and [15] therapies inhibiting IL-17 and IL-23 have demonstrated efficacy in treating skin and joint symptoms of PsA [16–20]. However, there is a paucity of data of the effectiveness of these treatments specifically in patients with axPsA. The MAXIMISE study demonstrated that treatment with the IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab significantly improved axial signs and symptoms in patients with PsA and had a baseline BASDAI score ≥ 4 and a spinal pain score ≥ 40, who were considered by the investigator to have axPsA [21]. Post hoc analyses of the phase 3 PSUMMIT-1 and PSUMMIT-2 studies showed that in patients with PsA who had physician-reported spondylitis, those receiving ustekinumab, an IL-12/23p40 inhibitor, had greater improvements in axial symptoms vs. placebo [22].

Guselkumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits the IL-23 p19 subunit and has demonstrated efficacy in adults with active PsA enrolled in the 1-year DISCOVER-1 [19] and 2-year DISCOVER-2 [20] studies. In post hoc analyses of pooled data from DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 evaluating patients with investigator-verified, imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis, those treated with guselkumab had greater mean improvements in BASDAI and ASDAS scores as well as greater response rates for achieving clinically meaningful improvements in BASDAI and ASDAS at week 24 compared with placebo [23]. Mean improvements and response rates for axial-related outcomes were maintained through 1 year in guselkumab-treated patients [23]. We now report additional post hoc analyses, including subgroup analyses by HLA-B*27 status, assessing the effect of guselkumab on the individual BASDAI components as well as durability of improvement in symptoms of axial disease through up to 2 years for patients in DISCOVER-2.

Methods

Patients and study design

DISCOVER-2 was a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of adults with active PsA (swollen and tender joint counts each ≥ 5 and CRP level ≥ 0.6 mg/dl) and an inadequate response or intolerance to non-biologic standard therapies (i.e., conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs [csDMARDs], nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or apremilast) [20]. Patients also had to have current (plaque ≥ 2 cm) or documented history of psoriasis. Prior treatment with biologics was not permitted. Patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive subcutaneous injections of guselkumab 100 mg every 4 weeks (Q4W); guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 0, 4, and Q8W; or placebo with crossover to guselkumab Q4W at week 24 [20]. Study treatment continued through week 100. Concomitant use of methotrexate and oral corticosteroids was permitted at stable doses.

The eligibility criteria and study design of the phase 3 DISCOVER-1 [19] study were similar to those of DISCOVER-2 with the exceptions of active PsA defined as swollen and tender joint counts each ≥ 3 and CRP level ≥ 0.3 mg/dl; 30% of patients had previously received tumor necrosis factor inhibitors; and the study duration was 1 year. DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices. The protocol was reviewed and approved by an institutional review board or ethics committee at each site (Supplementary Material), and all patients gave written informed consent.

As described in previous analyses through 1 year utilizing pooled data from the DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 studies, patients were included in these post hoc analyses if the investigator identified them as having axial symptoms in addition to the primary diagnosis of PsA as well as documented evidence of sacroiliitis either by prior imaging (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] or radiograph) or pelvic radiograph at screening [23]. All imaging was locally read.

Assessments

Both BASDAI [13] and ASDAS [14] instruments were used to assess axial symptoms in this cohort of patients with sacroiliitis. The BASDAI is a patient-reported assessment of the following six symptoms, each using a visual analogue scale (VAS) of 0–10 cm: fatigue (Question [Q] #1), spinal pain (Q#2), peripheral joint pain (Q#3), pain at entheseal sites (Q#4), severity of morning stiffness (Q#5), and duration of morning stiffness (Q#6). The total BASDAI score is the mean of the component scores, with higher scores indicating more severe disease and scores ≥ 4 indicating active disease. A modified BASDAI (mBASDAI) [24], which excluded Q#3 pertaining to peripheral joint pain to minimize influence by the primary PsA diagnosis, was also determined. The ASDAS was developed by the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) to evaluate disease activity in patients with AS; the ASDAS utilized in the DISCOVER studies comprised three BASDAI components (spinal pain, peripheral joint pain, duration of morning stiffness), the patient global assessment of disease activity (arthritis; VAS, 0–10 cm), and CRP. ASDAS scores < 1.3 and < 2.1 represent inactive disease and low disease activity (LDA), respectively, while a score > 3.5 indicates very high disease activity [25, 26]. Reductions in ASDAS scores ≥ 1.1 or ≥ 2.0 are considered to be clinically important or major improvements, respectively [25].

Blood samples were collected for genetic testing of HLA-B*27 status (positive/negative) in patients who provided additional consent [23]. Patients who had at least one HLA-B*27 allele [27] were classified as HLA-B*27+.

Statistical methods

BASDAI and ASDAS-related endpoints were summarized by randomized treatment group through week 100 among DISCOVER-2 participants. Through week 24, least squares (LS) mean changes in total BASDAI, spinal pain, mBASDAI, and ASDAS scores and corresponding nominal (unadjusted) p values for each guselkumab group vs. placebo were determined using a mixed-effect model for repeated measures (MMRM) that included all available data from weeks 0–24 [23]. For patients with available genetic samples, LS mean changes in BASDAI and ASDAS scores from baseline to week 24 were also summarized by HLA-B*27 status (positive/negative). In addition, absolute mean changes from baseline in total BASDAI, spinal pain, mBASDAI, and ASDAS scores were determined at weeks 24, 52, and 100; no formal hypothesis testing was performed for absolute mean changes. Through week 24, patients who met treatment failure rules (discontinuation of study agent due to inadequate response; discontinuation of study participation for any reason; initiation or increase in dose of csDMARDs or corticosteroids for PsA; initiation of prohibited therapies for PsA) [19, 20] were considered to have no change from baseline; no imputation was performed for missing data. After week 24, patients who discontinued study treatment for any reason were imputed as a change of 0 (nonresponder imputation [NRI]).

The proportions of patients achieving ≥ 50% improvement in BASDAI (BASDAI 50), ASDAS responses (clinically important improvement, major improvement, and inactive disease), and ASDAS LDA were determined at weeks 24, 52, and 100 using the same treatment failure rules through week 24 and NRI applied for missing data at weeks 24, 52, and 100. Comparisons of response rates between each guselkumab group vs. placebo at week 24 were performed utilizing the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by baseline use of csDMARD (yes, no) and CRP prior to randomization (< 2.0 vs. ≥ 2.0 mg/dl). Treatment group comparisons through week 24 were not adjusted for multiplicity of testing, and all reported p values are nominal. No treatment group comparisons were performed after week 24. Additional exploratory analyses examined the response rates (utilizing combined data from the guselkumab Q4W and Q8W groups and employing NRI) for achieving BASDAI 50 and ASDAS major improvement in male and female patients.

Mean total BASDAI scores are reported through week 100. Through week 24, treatment failure rules were applied [19, 20], and missing data were assumed to be missing at random. Nominal p values for each guselkumab group vs. placebo through week 24 were determined using MMRM; no treatment group comparisons were performed after week 24.

Mean scores for the six individual BASDAI components were determined through week 100 by randomized treatment group utilizing observed data. An exploratory analysis of mean BASDAI component scores was also performed utilizing pooled observed data through week 52 from DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2.

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Disposition

Among all randomized and treated patients in DISCOVER-2, 33% (246/739; Q4W n = 82, Q8W n = 68, placebo n = 96) had imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis and were included in these analyses of axial symptoms; 145 (Q4W n = 48, Q8W n = 43, placebo n = 54) had prior imaging, and 101 (Q4W n = 34, Q8W n = 25, placebo n = 42) had a pelvic radiograph at screening. Baseline demographic and disease characteristics for these patients were generally similar to those of the overall DISCOVER-2 population [20], with the exception of greater proportions of male patients comprising this axial cohort (59–66% vs. 48–58%, respectively). Across the three treatment groups, nearly all patients were White (99–100%), the mean age was 44–45 years, and the mean disease duration was 5–6 years (Table 1). Mean BASDAI (6.5–6.6) and ASDAS (3.9–4.1) scores suggested highly active axial disease. Of the 149 patients with available samples, approximately one-third were positive for HLA-B*27 (Q4W 19/48, Q8W 12/38, placebo 17/63).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics for DISCOVER-2 patients with active PsA and investigator-verified, imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis

| Guselkumab 100 mg | Placebo | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Q4W | Q8W | ||

| Patients, N | 82 | 68 | 96 |

| Sex | |||

| Female, n (%) | 28 (34.1) | 28 (41.2) | 37 (38.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 54 (65.9) | 40 (58.8) | 59 (61.5) |

| Age, years | 44.2 ± 12.0 | 45.0 ± 10.7 | 44.2 ± 11.3 |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 |

| White | 82 (100.0) | 67 (98.5) | 96 (100.0) |

| Age, years | 44.2 ± 12.0 | 45.0 ± 10.7 | 44.2 ± 11.3 |

| BMI | 27.7 ± 5.9 | 28.0 ± 6.5 | 28.4 ± 6.5 |

| PsA duration, years | 5.2 ± 5.7 | 4.9 ± 5.4 | 5.8 ± 5.2 |

| BASDAI | |||

| Patients | 79 | 62 | 89 |

| Total | 6.5 ± 1.6 | 6.6 ± 1.9 | 6.6 ± 1.6 |

| Fatigue (Q#1) | 6.4 ± 1.9 | 6.7 ± 1.9 | 6.5 ± 1.8 |

| Spinal pain (Q#2) | 6.5 ± 2.2 | 6.6 ± 2.2 | 6.7 ± 1.9 |

| Joint pain (Q#3) | 6.4 ± 1.9 | 6.6 ± 2.1 | 6.8 ± 1.8 |

| Enthesitis (Q#4) | 6.3 ± 2.0 | 6.6 ± 2.3 | 6.4 ± 2.2 |

| Qualitative morning stiffness (Q#5) | 6.9 ± 2.0 | 7.0 ± 2.5 | 7.0 ± 2.0 |

| Quantitative morning stiffness (Q#6) | 6.4 ± 2.8 | 6.0 ± 2.7 | 6.3 ± 2.8 |

| ASDAS | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 4.0 ± 0.8 |

| Swollen joint count (0–66) | 13.4 ± 9.1 | 11.3 ± 5.6 | 11.4 ± 7.1 |

| Tender joint count (0–68) | 24.7 ± 15.7 | 21.2 ± 12.4 | 21.5 ± 13.2 |

| Patients with enthesitis, n (%) | 65 (79.3) | 53 (77.9) | 70 (72.9) |

| Enthesitis score (LEI, 0–6)* | 2.8 ± 1.8 | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 2.8 ± 1.7 |

| Patients with dactylitis, n (%) | 49 (59.8) | 37 (54.4) | 42 (43.8) |

| Dactylitis score (0–60) | 9.0 ± 10.0 | 9.1 ± 9.4 | 8.0 ± 8.3 |

| HLA-B*27+ , n/N (%) | 19/48 (39.6) | 12/38 (31.6) | 17/63 (27.0) |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise noted

*n = 64 in the Q4W group

ASDAS Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, BMI body mass index, LEI Leeds Enthesitis Index, PsA psoriatic arthritis, Q Question, Q4W/Q8W every 4/8 weeks

Specific to the cohort of patients with imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis included in the current analyses, five (2%) (Q4W 3/82 [4%]; Q8W 1/68 [1%]; placebo 1/96 [1%]) discontinued study treatment through week 24. In total, 218 (89%) patients (Q4W 75/82 [91%]; Q8W 62/68 [91%]; placebo → Q4W 81/96 [84%]) completed the study through week 100.

Improvements in Total BASDAI and ASDAS Scores

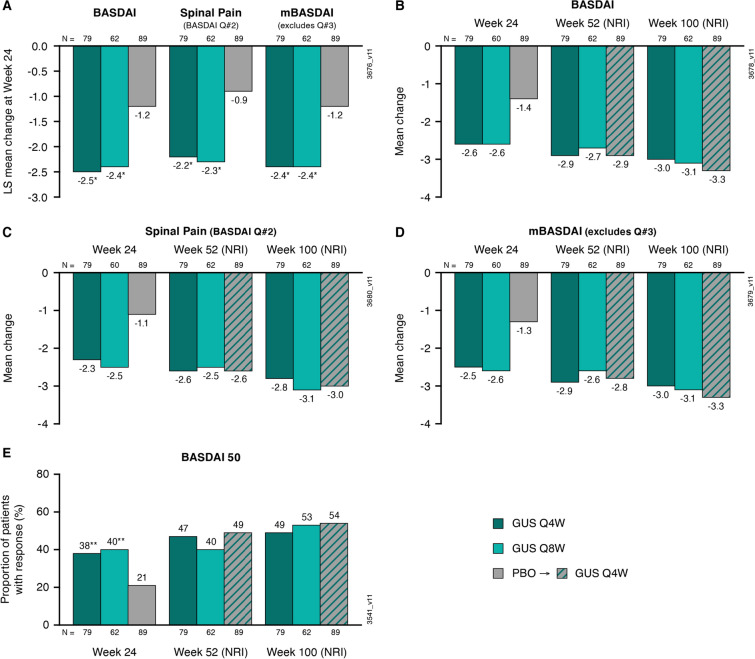

LS mean improvements from baseline at week 24 were greater in both the Q4W and Q8W groups than in the placebo group, respectively, in the total BASDAI (– 2.5 and – 2.4 vs. – 1.2), spinal pain (– 2.2 and – 2.3 vs. – 0.9), and mBASDAI (– 2.4 and – 2.4 vs. – 1.2) scores (all nominal p < 0.001; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

LS mean changes from baseline to week 24 among patients in DISCOVER-2 with active psoriatic arthritis and investigator-verified, imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis in BASDAI, spinal pain, and mBASDAI scores (A); mean changes from baseline to weeks 24, 52, and 100 in BASDAI (B), spinal pain (C), and mBASDAI (D) scores; and the proportions of patients achieving a BASDAI 50 response at weeks 24, 52, and 100 (E). Through week 24, treatment failure rules were applied for categorial endpoints, and LS mean changes were determined utilizing MMRM. After week 24, patients with missing data were considered nonresponders or to have no change from baseline (nonresponder imputation; NRI). Treatment group comparisons (each guselkumab group vs. placebo at week 24) were performed for LS mean changes and BASDAI 50 response. BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, BASDAI 50 ≥ 50% improvement in BASDAI, GUS guselkumab, LS least squares, mBASDAI modified BASDAI excluding Question #3, MMRM mixed-effect model for repeated measures, NRI nonresponder imputation, PBO placebo, Q Question, Q4W/Q8W every 4/8 weeks. Unadjusted p value vs. placebo: * < 0.001, **p < 0.05

Absolute mean changes from baseline in BASDAI score at week 24 were consistent with the LS mean changes: – 2.6 in the Q4W and Q8W groups and – 1.4 in the placebo group (Fig. 1). Mean improvements from baseline (utilizing NRI; missing data imputed as no change from baseline) continued to increase at both week 52 (Q4W – 2.9; Q8W – 2.7; placebo → Q4W – 2.9) and week 100 (Q4W – 3.0; Q8W – 3.1; placebo → Q4W – 3.3) (Fig. 1). Similar trends were observed for mean improvements in mBASDAI and spinal pain scores (Fig. 1). In addition, greater proportions of guselkumab-randomized patients achieved a BASDAI 50 response at week 24 compared with those receiving placebo (38–40% vs. 21%) (Fig. 1). Response rates at week 52 were similar among guselkumab-randomized patients and those who crossed over from placebo at week 24, ranging from 40 to 49%, and further increased at week 100 (49–54%; Fig. 1).

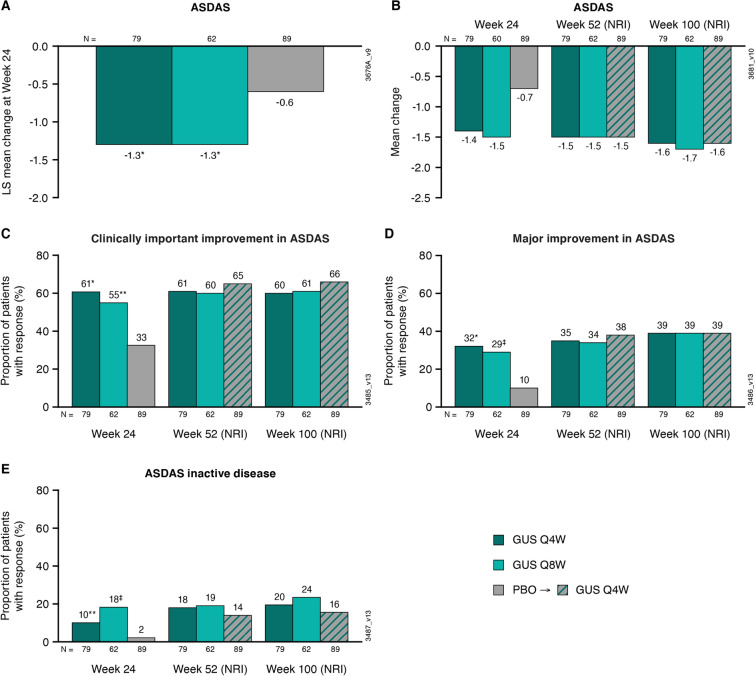

LS mean changes in ASDAS at week 24 were – 1.3 in both guselkumab groups compared with – 0.6 in the placebo group (nominal p < 0.001 for both; Fig. 2). Absolute mean changes in ASDAS at week 24 were similar to the LS mean changes at the same time point (Fig. 2) and were maintained at weeks 52 (Q4W – 1.5; Q8W – 1.5) and 100 (Q4W – 1.6; Q8W – 1.7) in guselkumab-randomized patients (Fig. 2). Mean changes in ASDAS at weeks 52 and 100 in the placebo → Q4W group (– 1.5 and – 1.6, respectively) were comparable to those observed in the Q4W and Q8W groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

LS mean changes from baseline to week 24 in patients from DISCOVER-2 with active psoriatic arthritis and investigator-verified, imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis in ASDAS (A); mean changes from baseline to weeks 24, 52, and 100 in ASDAS (B), and the proportions of patients achieving a ASDAS clinically important improvement (decrease ≥ 1.1) (C), ASDAS major improvement (decrease ≥ 2.0) (D), and ASDAS inactive disease (< 1.3) (E) at weeks 24, 52, and 100. Through week 24, treatment failure rules were applied, and LS mean changes were determined utilizing MMRM. After week 24, patients with missing data were considered nonresponders or to have no change from baseline (nonresponder imputation; NRI). Treatment group comparisons (each guselkumab group vs. placebo at week 24) were performed for LS mean change in ASDAS and ASDAS response rates. ASDAS Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, GUS guselkumab, LS least squares, MMRM mixed-effect model for repeated measures, NRI nonresponder imputation, PBO placebo, Q4W/Q8W every 4/8 weeks. Unadjusted p value vs. placebo: *p < 0.001; ‡p ≤ 0.01; **p < 0.05

At week 24, greater proportions of patients in the Q4W and Q8W groups than in the placebo group achieved a clinically important improvement in ASDAS (Q4W 61%, Q8W 55% vs. placebo 33%; nominal p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively), ASDAS major improvement (decrease ≥ 2.0; Q4W 32%, Q8W 29%, placebo 10%; nominal p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively), and ASDAS inactive disease (< 1.3; Q4W 10%, Q8W 18%, placebo 2%; nominal p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 2). ASDAS response rates (utilizing NRI) among guselkumab-randomized patients were maintained at week 52, with similar proportions of patients in the placebo → Q4W group also achieving response (Fig. 2). Response rates (NRI) at week 100 were 60–66% for ASDAS clinically important improvement, 39% across guselkumab-treated patients for ASDAS major improvement, and 16–24% for ASDAS inactive disease (Fig. 2). The proportions of patients achieving ASDAS < 2.1 followed a similar trend at weeks 24 (Q4W 34%, Q8W 39%, placebo 18%; nominal p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively) and 52 (Q4W 41%, Q8W 40%, placebo → Q4W 38%) and continued to increase through week 100 (Q4W 48%, Q8W 47%, placebo → Q4W 45%).

Subgroup Analyses

LS mean changes in BASDAI (total, spinal pain, and mBASDAI) and ASDAS were also assessed for HLA-B*27+ (n = 48) and HLA-B*27– (n = 101) subgroups among patients with available data. Mean improvements were consistent with the overall DISCOVER-2 axial cohort in both subgroups, with separation from placebo observed for guselkumab-treated patients at week 24 in both HLA-B*27+ (nominal p not significant) and HLA-B*27– (nominal p < 0.05) patients (Supplementary Material Fig. 1). LS mean changes in BASDAI scores tended to be numerically larger in the HLA-B*27– cohort, while results were similar between the subgroups when using the ASDAS.

The effect of guselkumab on achievement of a BASDAI 50 response and ASDAS major improvement was consistent in subgroups of male and female patients (Supplementary Material Fig. 2). The proportions of patients achieving these responses increased over time through week 100 in both cohorts (Supplementary Material Fig. 2).

Total BASDAI and Component Scores

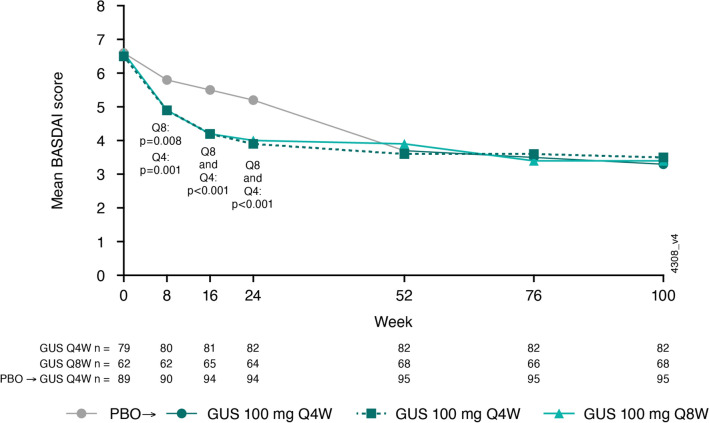

Mean total BASDAI scores at baseline were 6.5 in the Q4W group, 6.6 in the Q8W group, and 6.6 in the placebo group (Table 1). Guselkumab-treated patients had lower mean total BASDAI scores at weeks 8, 16, and 24, respectively, in the Q4W (4.9, 4.2, 3.9) and Q8W (4.9, 4.2, 4.0) groups when compared with placebo (5.8, 5.5, 5.2) (all nominal p < 0.01; Fig. 3). At week 100, the mean total BASDAI scores were similar between patients who had received guselkumab from baseline (Q4W 3.5; Q8W 3.4) and those who crossed over from placebo at week 24 (3.3) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mean total BASDAI scores through week 100 in patients from DISCOVER-2 with active psoriatic arthritis and investigator-verified, imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis. BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, GUS guselkumab, PBO placebo, Q4W/Q8W every 4/8 weeks

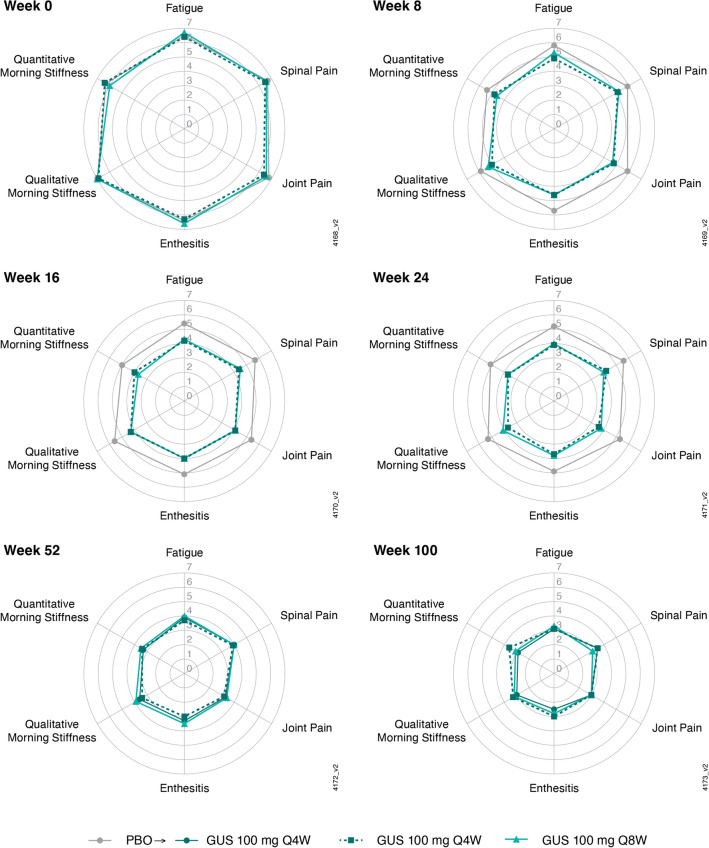

Similarly, mean baseline scores for the six BASDAI components ranged from 6.0 to 7.0, with comparable scores across the treatment groups (Table 1). Mean scores for all six BASDAI components decreased through week 24 in guselkumab-treated patients, with similar mean scores across dosing regimens, and separation from placebo evident at week 8 (Fig. 4), the earliest post-baseline timepoint at which these scores were determined. Mean scores for all six BASDAI components ranged from 2.5 to 3.6 at week 100 and were comparable for both guselkumab-randomized patients and those who crossed over from placebo to guselkumab at week 24 (Fig. 4). The same trend was observed through week 100 in both HLA-B*27+ and HLA-B*27– patients, although HLA-B*27+ patients generally had numerically higher mean scores at each timepoint (Supplementary Material Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

Mean BASDAI component scores (observed data) through week 100 in patients from DISCOVER-2 with active psoriatic arthritis and investigator-verified, imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis. BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, GUS guselkumab, PBO placebo, Q4W/Q8W every 4/8 weeks

Exploratory analyses of mean BASDAI component scores through 1 year in the pooled DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 cohort, both overall and by HLA-B*27 status, were consistent with those for DISCOVER-2 patients (Supplementary Material Figs. 4 and 5).

Discussion

In previous pooled analyses of 312 patients with investigator-verified, imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis from DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2, those treated with guselkumab demonstrated greater improvements in symptoms of axial disease at week 24 compared with those receiving placebo, with mean improvements and response rates maintained through 1 year [23]. Likewise, in the DISCOVER-2 only cohort of 246 biologic-naïve patients evaluated through 2 years in the current analyses, guselkumab-treated patients demonstrated greater LS mean improvements (total BASDAI, spinal pain, mBASDAI, and ASDAS scores) at week 24 compared with placebo. Patients in the guselkumab groups also had lower mean scores than those in the placebo group for the total BASDAI score and all six components through week 24. Improvements in these scores at week 24 were observed regardless of HLA-B*27 status. However, these results should be interpreted with caution as the sample sizes in these subgroups were relatively small and imbalanced; among patients with available data, approximately one-third were HLA-B*27+. For guselkumab-treated patients, mean improvements in total BASDAI, spinal pain, mBASDAI, and ASDAS scores increased through 1 and 2 years. Additionally, mean total BASDAI and component scores remained low through 2 years.

A treatment effect with guselkumab was also observed in the proportions of patients achieving BASDAI 50 and ASDAS (clinically important improvement, major improvement, inactive disease, and LDA) responses at week 24, and response rates were maintained through 2 years in both guselkumab groups. The proportions of patients achieving ASDAS responses (clinically important improvement, major improvement, inactive disease, and LDA) were generally similar between the two guselkumab dosing regimens at each timepoint, with the exception of the more stringent outcome of ASDAS inactive disease (score < 1.3), for which response rates were numerically lower in the Q4W group. The numerically higher response rate in patients receiving the Q8W dosing regimen may be related to some patients in this group having baseline scores just above the threshold for ASDAS inactive disease (ranges: Q4W 2.0–5.6, Q8W 1.4–6.3).

Although limited by the small sample sizes, additional exploratory analyses showed that the treatment effect of guselkumab was consistent in both males and females, with increasing response rates for achievement of BASDAI 50 and ASDAS major improvement over time through 2 years. Of note, greater variability was observed in female patients when assessing BASDAI 50 response, which is consistent with findings from patients with axial spondyloarthritis in a large observational study, suggesting that the BASDAI may be more susceptible to differences between males and females relative to the ASDAS [28].

Axial involvement in PsA is more common in patients with established disease; isolated axPsA is uncommon, occurring in approximately 2–5% of all patients [2, 29]. Because biologics targeting IL-23 have not demonstrated efficacy in patients with AS [30, 31], there has been some speculation that IL-23 inhibitors may not be efficacious in axPsA and that improvements observed in analyses such as those reported from DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 could be related to improvements in peripheral disease [32]. Despite overlapping features of AS and axPsA, patients with axPsA appear to have distinct clinical features in that they are more likely to experience peripheral joint pain and dactylitis as well as skin and nail disease [29, 33]. While patients with axPsA often experience inflammatory back pain, recent analyses suggest that this symptom occurs with a higher frequency in patients with AS [12, 29].

Furthermore, the incidence of HLA-B*27 positivity is higher in patients with axPsA than in patients with PsA without axial disease and the general population, but still lower than that observed in patients with AS [5, 12, 29, 33]. Findings from a recent analysis comparing the biomarker profile of patients with investigator-confirmed sacroiliitis in DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 with that of patients with AS were consistent with this pattern; additionally, patients with PsA and axial involvement had elevated baseline levels of serum IL-17A and IL-17F and enrichment of IL-17 and IL-10 pathway-associated genes [34]. Separate research has also identified distinct IL-23 and IL-23R polymorphisms in patients with PsA and AS [35–37]. These genetic differences may account for the differential response to IL-23 inhibition in patients with these conditions.

HLA-B*27 positivity in patients with PsA has been associated with both higher risk of axial involvement [38] and more extensive peripheral joint damage [11]. As previously reported, guselkumab-treated patients in the overall DISCOVER-2 population demonstrated low levels of radiographic progression through 2 years [39] that was associated with a higher likelihood of achieving the minimal disease activity criteria for swollen and tender joints, patient-reported pain and global disease activity, and normalized physical function [40]. The current exploratory post hoc analyses suggest that guselkumab may be efficacious in reducing the symptoms of axial disease, as assessed by the BASDAI and ASDAS, in patients with active PsA regardless of HLA-B*27 status.

The BASDAI and ASDAS instruments were developed for use in patients with AS and have since been utilized for patients with axPsA primarily due to the lack of diagnostic criteria and assessment tools specific to axPsA. Although both instruments have been shown to perform similarly in patients with axPsA [24, 41], utilization of these assessments in patients with axPsA is complicated by the inclusion of components assessing peripheral symptoms that also occur in patients without axial involvement. In separate analyses of patients with PsA, those with axial disease had higher BASDAI scores, on average, than patients without axial disease [42–44]; however, other analyses have found that changes in BASDAI were similar in patients with and without axial symptoms [43, 44]. ASAS and the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) have therefore initiated the Axial Involvement in Psoriatic Arthritis Study (AXIS) to develop classification criteria for axPsA and a unified nomenclature to improve research into this patient population [45].

Current GRAPPA guidelines for patients with axPsA relied on data generated in patients with radiographic and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis for recommending tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, IL-17 inhibitors, and Janus kinase inhibitors for axPsA patients [46]. To date, treatment recommendations regarding therapies that inhibit IL-12/23 or IL-23 are noted to have insufficient/inadequate evidence of efficacy in this patient population, as existing data were derived from post hoc analyses [22, 23]. Real-world evidence suggests a considerable unmet need remains for therapies that effectively treat axial disease in patients with PsA [47]. Therefore, the additional data reported here as well as results from the ongoing phase 4 STAR study that was designed to prospectively evaluate the effect of guselkumab on inflammation of the spine and sacroiliac joints using MRI in axPsA patients [48] will be critical in addressing this data gap. Together, with the AXIS study, results from the STAR study will significantly advance the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of patients with axPsA.

The findings reported in the present analyses from DISCOVER-2 are limited by the post hoc nature of the analyses. This study was not powered to evaluate guselkumab specifically in patients with axPsA. Patients in these analyses were required to meet the DISCOVER-2 entry criteria for joint and skin disease, all were biologic-naïve, the majority were males, and nearly all were White, potentially limiting the generalizability of these results to the broader population of patients with PsA. The BASDAI and ASDAS instruments utilized VAS scores that were collected digitally via a tablet. Although the BASDAI and ASDAS were initially validated employing these visual scales [13], it should be noted that this method, as opposed to a numerical rating scale, may pose a limitation for patients with literacy or vision impairments [49]. Additionally, although investigators confirmed the presence of sacroiliitis through either radiographs or MRI, spinal inflammation was not assessed objectively using MRI. The presence of axPsA in this study population was determined by the investigators using locally read imaging, the accuracy of which can be limited by variability in MRI reader expertise [50].

Although these analyses were performed post hoc, conservative statistical methods were applied, including NRI. Consistent with the full study population [39], approximately 90% of patients included in these post hoc analyses completed their study treatment through week 100, allowing for a robust evaluation of the long-term effects of guselkumab on symptoms of axial disease in patients with active PsA.

Conclusions

In this post hoc analysis of biologic-naïve adults with active PsA and investigator-confirmed sacroiliitis from DISCOVER-2, patients treated with guselkumab demonstrated greater improvements in symptoms of axial disease and higher response rates for achieving meaningful improvements through week 24 when compared with placebo and durable efficacy, as assessed by BASDAI, mBASDAI, spinal pain, and ASDAS scores, through 2 years.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

The authors thank Yanli Wang (consultant funded by Janssen) for statistical support and Cynthia Guzzo, MD (consultant funded by Janssen) for substantive review. Medical writing support was provided by Rebecca Clemente, PhD, of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC under the direction of the authors in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2022;175:1298–1304).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Study concept/design: Philip J. Mease, Dafna D. Gladman, Denis Poddubnyy, Soumya D. Chakravarty, May Shawi, Alexa P. Kollmeier, Xie L. Xu, Atul Deodhar, Xenofon Baraliakos. Data analyses: Stephen Xu. Data interpretation: Philip J. Mease, Dafna D. Gladman, Denis Poddubnyy, Soumya D. Chakravarty, May Shawi, Alexa P. Kollmeier, Xie L. Xu, Stephen Xu, Atul Deodhar, Xenofon Baraliakos. All authors revised the manuscript and approved it for submission.

Funding

Janssen Research & Development, LLC, provided funding for this study and the Rapid Service Fee.

Data Availability

The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the study data can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access [YODA] Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Philip J. Mease has received research grants from AbbVie, Acelyrin, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, SUN, and UCB; consulting fees from AbbVie, Acelyrin, Aclaris, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Immagene, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, SUN, UCB, Ventyx; speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. Dafna D. Gladman has received grant support from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB and consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. Denis Poddubnyy has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Biocad, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB and grants from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, and Pfizer. Soumya D. Chakravarty is an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and owns stock in Johnson & Johnson. May Shawi, Alexa P. Kollmeier, Xie L. Xu, and Stephen Xu are employees of Janssen Research & Development, LLC, and own stock in Johnson & Johnson. Atul Deodhar received consulting fees for participation in Advisory Boards from AbbVie, Amgen, Aurinia, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, MoonLake, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; Research Grant funding from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; and Speaker fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. Xenofon Baraliakos has received consulting fees, grant/research support/speaker support from AbbVie, Biocad, Chugai, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB.

Ethical approval

DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices. The protocols were reviewed and approved by an institutional review board or ethics committee at each site (Supplementary Material), and all patients gave written informed consent.

References

- 1.Feld J, Chandran V, Haroon N, Inman R, Gladman D. Axial disease in psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: a critical comparison. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14:363–371. doi: 10.1038/s41584-018-0006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gladman DD. Axial disease in psoriatic arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2007;9:455–460. doi: 10.1007/s11926-007-0074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottlieb A, Korman NJ, Gordon KB, Feldman SR, Lebwohl M, Koo JY, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 2. Psoriatic arthritis: overview and guidelines of care for treatment with an emphasis on the biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:851–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hanly JG, Russell ML, Gladman DD. Psoriatic spondyloarthropathy: a long-term prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47:386–393. doi: 10.1136/ard.47.5.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baraliakos X, Coates LC, Braun J. The involvement of the spine in psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:S31–S35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gezer HH, Duruoz MT. The value of SPARCC sacroiliac MRI scoring in axial psoriatic arthritis and its association with other disease parameters. Int J Rheum Dis. 2022;25:433–439. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.14285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mease PJ, Palmer JB, Liu M, Kavanaugh A, Pandurengan R, Ritchlin CT, et al. Influence of axial involvement on clinical characteristics of psoriatic arthritis: analysis from the Corrona Psoriatic Arthritis/Spondyloarthritis Registry. J Rheumatol. 2018;45:1389–1396. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.171094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jadon DR, Sengupta R, Nightingale A, Lindsay M, Korendowych E, Robinson G, et al. Axial Disease in Psoriatic Arthritis study: defining the clinical and radiographic phenotype of psoriatic spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:701–707. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottlieb AB, Merola JF. Axial psoriatic arthritis: An update for dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eder L, Chandran V, Gladman DD. What have we learned about genetic susceptibility in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:91–98. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandran V, Tolusso DC, Cook RJ, Gladman DD. Risk factors for axial inflammatory arthritis in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:809–815. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feld J, Ye JY, Chandran V, Inman RD, Haroon N, Cook R, et al. Is axial psoriatic arthritis distinct from ankylosing spondylitis with and without concomitant psoriasis? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59:1340–1346. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2286–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lukas C, Landewe R, Sieper J, Dougados M, Davis J, Braun J, et al. Development of an ASAS-endorsed disease activity score (ASDAS) in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:18–24. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.094870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veale DJ, Fearon U. The pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis. Lancet. 2018;391:2273–2284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb AB, Puig L, Rahman P, Ritchlin C, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT 1 trial. Lancet. 2013;382:780–789. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritchlin C, Rahman P, Kavanaugh A, McInnes IB, Puig L, Li S, et al. Efficacy and safety of the anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite conventional non-biological and biological anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy: 6-month and 1-year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised PSUMMIT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:990–999. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Kirkham B, Kavanaugh A, Rahman P, van der Heijde D, et al. Secukinumab inhibition of interleukin-17A in patients with psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1329–1339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deodhar A, Helliwell PS, Boehncke WH, Kollmeier AP, Hsia EC, Subramanian RA, et al. Guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis who were biologic-naive or had previously received TNFa inhibitor treatment (DISCOVER-1): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mease PJ, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, Kollmeier AP, Hsia EC, Xu XL, et al. Guselkumab in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (DISCOVER-2): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1126–1136. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baraliakos X, Gossec L, Pournara E, Jeka S, Mera-Varela A, D'Angelo S, et al. Secukinumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis and axial manifestations: results from the double-blind, randomised, phase 3 MAXIMISE trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:582–590. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kavanaugh A, Puig L, Gottlieb AB, Ritchlin C, You Y, Li S, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in psoriatic arthritis patients with peripheral arthritis and physician-reported spondylitis: post-hoc analyses from two phase III, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (PSUMMIT-1/PSUMMIT-2) Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1984–1988. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-209068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mease PJ, Helliwell PS, Gladman DD, Poddubnyy D, Baraliakos X, Chakravarty SD, et al. Efficacy of guselkumab on axial involvement in patients with active psoriatic arthritis and sacroiliitis: a post-hoc analysis of the phase 3 DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 studies. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:E715–E723. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eder L, Chandran V, Shen H, Cook RJ, Gladman DD. Is ASDAS better than BASDAI as a measure of disease activity in axial psoriatic arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:2160–2164. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.129726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Machado P, Landewe R, Lie E, Kvien TK, Braun J, Baker D, et al. Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease activity states and improvement scores. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:47–53. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Machado PM, Landewe R, van der Heijde D, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international S Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): 2018 update of the nomenclature for disease activity states. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1539–1540. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marsh SGE, Albert ED, Bodmer WF, Bontrop RE, Dupont B, Erlich HA, et al. Nomenclature for factors of the HLA system, 2010. Tissue Antigens. 2010;75:291–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2010.01466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benavent D, Capelusnik D, Ramiro S, Molto A, Lopez-Medina C, Dougados M, et al. Does gender influence outcome measures similarly in patients with spondyloarthritis? Results from the ASAS-perSpA study. RMD Open. 2022;8:e002514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Kwok TSH, Sutton M, Pereira D, Cook RJ, Chandran V, Haroon N, et al. Isolated axial disease in psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis with psoriasis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:1678–1684. doi: 10.1136/ard-2022-222537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baeten D, Ostergaard M, Wei JC, Sieper J, Jarvinen P, Tam LS, et al. Risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor, for ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept, dose-finding phase 2 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1295–1302. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deodhar A, Gensler LS, Sieper J, Clark M, Calderon C, Wang Y, et al. Three multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:258–270. doi: 10.1002/art.40728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braun J, Landewe RBM. No efficacy of anti-IL-23 therapy for axial spondyloarthritis in randomised controlled trials but in post-hoc analyses of psoriatic arthritis-related 'physician-reported spondylitis'? Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:466–468. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fragoulis GE, Pappa M, Evangelatos G, Iliopoulos A, Sfikakis PP, Tektonidou MG. Axial psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: same or different? A real-world study with emphasis on comorbidities. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2022;40:1267–1272. doi: 10.55563/clinexprheumatol/8zn9z8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kavanaugh A, Baraliakos X, Gao S, Chen W, Sweet K, Chakravarty SD, et al. Genetic and molecular distinctions between axial psoriatic arthritis and radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: post hoc analyses from four phase 3 clinical trials. Adv Ther. 2023;40:2439–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.McGonagle D, Watad A, Sharif K, Bridgewood C. Why inhibition of IL-23 lacked efficacy in ankylosing spondylitis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:614255. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.614255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahman P, Inman RD, Gladman DD, Reeve JP, Peddle L, Maksymowych WP. Association of interleukin-23 receptor variants with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1020–1025. doi: 10.1002/art.23389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vecellio M, Hake VX, Davidson C, Carena MC, Wordsworth BP, Selmi C. The IL-17/IL-23 axis and its genetic contribution to psoriatic arthritis. Front Immunol. 2021;11:596086. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.596086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Queiro R, Sarasqueta C, Belzunegui J, Gonzalez C, Figueroa M, Torre-Alonso JC. Psoriatic spondyloarthropathy: a comparative study between HLA-B27 positive and HLA-B27 negative disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;31:413–418. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2002.33470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McInnes IB, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, Hsia EC, Kollmeier AP, Xu XL, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of guselkumab, a monoclonal antibody specific to the p19 subunit of interleukin-23, through two years: results from a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74:475–485. doi: 10.1002/art.42010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gottlieb AB, McInnes IB, Rahman P, Kollmeier AP, Xu XL, Jiang Y, et al. Low rates of radiographic progression associated with clinical efficacy following up to 2 years of treatment with guselkumab: results from a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis. RMD Open. 2023;9:e002789. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2022-002789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baraliakos X, Gladman D, Chakravarty S, Gong C, Shawi M, Rampakakis E, et al. Performance of BASDAI vs. ASDAS in evaluating axial involvement in patients with PsA treated with guselkumab: pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74: https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/performance-of-basdai-vs-asdas-in-evaluating-axial-involvement-in-patients-with-psa-treated-with-guselkumab-pooled-analysis-of-two-phase-3-studies/. Accessed 29 Mar 2023

- 42.Taylor WJ, Harrison AA. Could the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) be a valid measure of disease activity in patients with psoriatic arthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:311–315. doi: 10.1002/art.20421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reddy S, Husni ME, Scher J, Craig E, Ogdie A, Walsh J. Use of the BASDAI in psoriatic arthritis patients with and without axial disease [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72: https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/use-of-the-basdai-in-psoriatic-arthritis-patients-with-and-without-axial-disease/. Accessed 9 Jan 2023

- 44.Ogdie A, Blachley T, Lakin PR, Dube B, McLean RR, Hur P, et al. Evaluation of clinical diagnosis of axial psoriatic arthritis (PsA) or elevated patient-reported spine pain in CorEvitas' PsA/Spondyloarthritis Registry. J Rheumatol. 2022;49:281–290. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.210662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poddubnyy D, Baraliakos X, Van den Bosch F, Braun J, Coates LC, Chandran V, et al. Axial Involvement in psoriatic arthritis cohort (AXIS): the protocol of a joint project of the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) and the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2021;13:1759720X211057975. doi: 10.1177/1759720X211057975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coates LC, Soriano ER, Corp N, Bertheussen H, Callis Duffin K, Campanholo CB, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA): updated treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis 2021. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18:465–479. doi: 10.1038/s41584-022-00798-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mease PJ, Chakravarty SD, McLean RR, Blachley T, Kawashima T, Lin I, et al. Treatment responses in patients with psoriatic arthritis axial disease according to Human Leukocyte Antigen-B27 status: an analysis from the CorEvitas Psoriatic Arthritis/Spondyloarthritis Registry. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2022;4:447–456. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Bird P, Soriano ER, Chakravarty SD, Shawi M, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in biologic-naive patients with active axial psoriatic arthritis: study protocol for STAR, a phase 4, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Trials. 2022;23:743. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06589-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Tubergen A, Debats I, Ryser L, Londono J, Burgos-Vargas R, Cardiel MH, et al. Use of a numerical rating scale as an answer modality in ankylosing spondylitis-specific questionnaires. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:242–248. doi: 10.1002/art.10397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maksymowych WP, Pedersen SJ, Weber U, Baraliakos X, Machado PM, Eshed I, et al. Central reader evaluation of MRI scans of the sacroiliac joints from the ASAS classification cohort: discrepancies with local readers and impact on the performance of the ASAS criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:935–942. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the study data can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access [YODA] Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.