Abstract

Monoclonal antibodies and epifluorescence microscopy were used to determine the depth distribution of two indigenous bacterial populations in the stratified Lake Plußsee and characterize their life strategies. Populations of Comamonas acidovorans PX54 showed a depth distribution with maximum abundances in the oxic epilimnion, whereas Aeromonas hydrophila PU7718 showed a depth distribution with maximum abundances in the anoxic thermocline layer (metalimnion), i.e., in the water layer with the highest microbial activity. Resistance of PX54 to protist grazing and high metabolic versatility and growth rate of PU7718 were the most important life strategy traits for explaining the depth distribution of the two bacterial populations. Maximum abundance of PX54 was 16,000 cells per ml, and maximum abundance of PU7718 was 20,000 cells per ml. Determination of bacterial productivity in dilution cultures with different-size fractions of dissolved organic matter (DOM) from lake water indicates that low-molecular-weight (LMW) DOM is less bioreactive than total DOM (TDOM). The abundance and growth rate of PU7718 were highest in the TDOM fractions, whereas those of PX54 were highest in the LMW DOM fraction, demonstrating that PX54 can grow well on the less bioreactive DOM fraction. We estimated that 13 to 24% of the entire bacterial community and 14% of PU7718 were removed by viral lysis, whereas no significant effect of viral lysis on PX54 could be detected. Growth rates of PX54 (0.11 to 0.13 h−1) were higher than those of the entire bacterial community (0.04 to 0.08 h−1) but lower than those of PU7718 (0.26 to 0.31 h−1). In undiluted cultures, the growth rates were significantly lower, pointing to density effects such as resource limitation or antibiosis, and the effects were stronger for PU7718 and the entire bacterial community than for PX54. Life strategy characterizations based on data from literature and this study revealed that the fast-growing and metabolically versatile A. hydrophila PU7718 is an r-strategist or opportunistic population in Lake Plußsee, whereas the grazing-resistant C. acidovorans PX54 is rather a K-strategist or equilibrium population.

There are a vast number of studies on the population ecology of phytoplankton and zooplankton, whereas such investigations of bacterioplankton populations are sparse. The major reason for this is that bacteria lack morphological structures which allow for taxonomic identification in many eukaryotes. In contrast, classical bacterial taxonomy strongly depends on assessing metabolic features that can be studied only after isolation of strains. However, since typically less than 1% of the bacterial community in aquatic systems can be grown on culture medium (2), we know only little of the distribution, control mechanisms, and life strategies of bacterioplankton populations.

A variety of nucleic-acid-based techniques have been developed to circumvent the cultivation problem and study microbial diversity and community structure in the environment (for reviews, see references 15 and 30). However, the molecular technique with the highest taxonomic resolution is probing with antibodies which can be specific for bacterial strains. To avoid the main problem of immunological techniques, i.e., the high probability of cross-reactivity, monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) which are specific for epitopes on the cell surface of isolates can be developed. Antibodies have been used already to detect populations in different habitats and to study their depth distribution and population dynamics (11, 28, 34, 43). Also, the cell numbers of functional groups such as ammonia and nitrate oxidizers (35), denitrifiers (36), and cyanobacteria (9) have been determined in aquatic systems. Yet, MAbs have not been used to study the mechanisms which control the growth of indigenous populations in dilution cultures along with the natural bacterial community.

Two basic types of life strategies have been distinguished in eukaryotes (26). Populations that are subject to disturbances and thus grow in regular or erratic bursts are called opportunistic, whereas those which exist at more stable densities are termed equilibrium populations. Opportunistic populations typically grow fast, whereas equilibrium populations have a high competitive ability. These populations are also called r-strategists and K-strategists, respectively. Andrews and Harris (5) provided a framework to apply the concept of r- and K-selection to microbial ecology. Due to the problem of identifying populations in natural bacterial communities, life strategies were typically assessed by quantifying the maximum specific rate of increase and the competitive ability for limiting resources with isolates grown in culture medium; studies of r- and K-selection of single populations in bacterial communities are rare. Using oligonucleotides (2) or MAbs as taxonomic probes now allows for such investigations.

Nutrient pulses (20) and grazing of bacteria by protozoans (29) can strongly affect the community structure and population density of species. Since resource availability and grazing are the major known mechanisms for controlling bacterial production, it is possible that these mechanisms also regulate population dynamics and thus diversity. Viral lysis is another major mechanism for bacterial mortality; however, although it has been speculated that viral lysis might influence bacterial diversity (17, 32), evidence for this role of viruses is still sparse. Recent findings also indicate that high-molecular-weight (HMW) dissolved organic matter (DOM) is more bioreactive than low-molecular-weight (LMW) DOM (3). Thus, it is conceivable that the relative amount and the composition of DOM fractions influence the growth of individual bacterial strains and, by that, bacterial community structure.

We used strain-specific MAbs developed against Comamonas acidovorans PX54 and Aeromonas hydrophila PU7718 isolated from Lake Plußsee (14) to determine the depth distribution of the two populations in this lake during water stratification and the effect of different-size fractions of DOM on their growth in comparison to the entire bacterial community. PX54 showed a depth distribution with maximum abundances in the epilimnion, whereas PU7718 showed a depth distribution with maximum abundances in the metalimnion. Data from a DOM size fractionation experiment and from metabolic profiles were used to explain the depth distribution of the two strains and to characterize their life strategies in Lake Plußsee.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling and study site.

The study site was Lake Plußsee (10°23′E, 54°10′N) near Plön in Schleswig-Holstein (northern Germany). Lake Plußsee is a eutrophic dimictic lake which is stratified during summer into the warm and oxic epilimnion and the cold and anoxic hypolimnion, separated by the thermocline layer (metalimnion, [22]). On 23 September 1996, water samples were collected along a depth profile with a Ruttner sampler from a permanent platform mounted in the center of the lake. Subsamples were preserved in formaldehyde (2% final concentration) and kept at 4°C in the dark. For a more detailed description of the sampling site, see reference 38.

Immunofluorescence microscopy of bacterial populations.

The strains C. acidovorans PX54 and A. hydrophila PU7718 were isolated previously from Lake Plußsee (8), and the MAbs III4G8 (anti-PU7718) and I4B1 (anti-PX54) were produced against these isolates (14). No cross-reactivity of these MAbs was found with closely or distantly related isolates from the same environment or culture collections. Enumeration of bacteria by using MAbs and epifluorescence microscopy was performed as described in the work of Faude and Höfle (14). Briefly, bacteria from 5- to 15-ml samples were collected onto 0.2-μm-pore-size black polycarbonate filters (Nuclepore) and incubated for 1 h in 3 ml of 0.2-μm-pore-size-sterile-filtered hydridoma supernatant containing the primary MAb. The MAb was stained with a dichlorotriazinylamino-fluorescein-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody (Dianova). Bacteria were stained for 15 min with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; final concentration, 1 μg ml−1). Unspecific staining by the conjugate was tested by omitting the primary antibody. Cells recognized by MAbs were enumerated by using an epifluorescence microscope (Axiovert model 135TV microscope; Zeiss).

Microbial cell counts.

Bacteria and viruses were stained with DAPI (final concentration, 1 μg ml−1) and enumerated by the use of epifluorescence microscopy. Samples (1 ml) for bacteria and viruses were stained for 30 min, filtered onto 0.02-μm-pore-size Anodisc filters (Whatman), and enumerated as described in reference 41. The number of CFU was determined on casein peptone starch (8 g per liter; Difco Corp.)–1.5% agar plates.

Bacterial production.

Bacterial production was estimated by the [3H]thymidine ([methyl-3H]TdR; 83.0 Ci mmol−1; Amersham) incorporation method (16). Samples were spiked with [3H]TdR at a final concentration of 20 nM, since the incorporation of [3H]TdR in the trichloroacetic acid-insoluble macromolecular fraction is constant for bacterioplankton in Lake Plußsee at concentrations ≥ 15 nM (10). Incubations (5 ml) were done in triplicate, and duplicate formaldehyde-killed samples served as controls. Following incubation (ca. 60 min), samples were filtered onto cellulose nitrate filters (Millipore GSWP; 0.22-μm-pore size), and [3H]TdR was extracted by two incubations (10 min) with 5% ice-cold trichloroacetic acid. The filters were dissolved with scintillation cocktail, and radioactivity was determined with a Packard Tricarb 8500 system. Conversion factors for relating TdR incorporation to cell production were obtained from values determined in fall during a seasonal study in Lake Plußsee and averaged 1.92 × 106 cells pmol−1 for the euphotic zone (10). Estimated cell production was applied to estimate carbon production by using cell volumes determined in the experiments (37) and a conversion factor of 350 fg of C μm−3 (23) for relating the bacterial biovolume to the carbon content.

Determination of visibly infected bacteria.

The number of visibly infected cells (VICs) was determined by a transmission electron microscopy-based method described in reference 39. Bacteria from 10-ml samples were collected quantitatively onto Formvar-coated, 400-mesh electron microscope grids by centrifugation in a swinging-bucket rotor (Beckman SW-41; 66,000 × g for 20 min), stained for 30 s with 1% uranyl acetate, and rinsed three times with deonized distilled water. The chosen time and speed of centrifugation reduce disruption of infected bacteria, and as few viruses are pelleted, phages within bacteria are easily distinguished (40). Grids were screened for VICs by using a transmission electron microscope (CEM 902 model; Zeiss) operated at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. Between 500 and 2,000 cells per sample were examined for mature phages within the cells. A minimum of five phages was observed in a VIC. Viruses inside cells were identified based on uniformity of structure, size, and intensity of staining (39). According to the model of Proctor et al. (27), bacterial mortality due to viral lysis was estimated by multiplying the frequency of VICs (FVICs) by the average (10.84) and the range of conversion factors (7.4 to 14.28).

Dilution cultures.

To test the effect of different size fractions of DOM on the growth of bacterial populations and the entire bacterial community, 100 liters of lake water was collected on 24 September 1996 from a 0.5-m depth by using a submersible pump and prefiltered through 10-μm-pore-size Nitex screening and 3-μm-pore-size filters (Nuclepore) to remove larger zooplankton and phytoplankton and a part of the protozoan plankton. Twenty liters of prefiltered water was passed through Milli Q-rinsed 0.2-μm-pore-size polycarbonate filters (Nuclepore) to remove bacterioplankton and obtain total DOM (TDOM), which contains the majority of the natural virus community (virus-rich TDOM). Forty liters of prefiltered samples was passed through a 0.1-μm-pore-size hollow-fiber filter with a tangential-flow ultrafiltration system (Amicon M12) to concentrate bacteria for later use as an inoculum (6). The abundance of viruses in the fraction of DOM passing this filter was reduced compared to that in the virus-rich TDOM fraction, whereas dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentrations (for the determination of DOC concentrations, see below) were similar (Table 1). Thus, this fraction of lake water was termed virus-reduced TDOM fraction. A subsample (20 liters) of the virus-reduced TDOM fraction was filtered through a spiral cartridge (Amicon S10Y1; 1-kDa cutoff) to obtain the virus free LMW DOM fraction. Aliquots of the bacterial concentrate were added to the three DOM fractions at a final concentration of 10%, in order to reduce contact rates between bacteria and flagellates and competition between bacteria and to avoid nutrient limitation. Duplicate 10-liter glass flasks were incubated at in situ temperatures (15°C) in the dark. An additional incubation sample contained the fraction that passed a 3.0-μm-pore-size filter (undiluted culture). Samples for bacterial and viral counts were preserved in formaldehyde (2% final concentration) and kept at 4°C in the dark until analysis. Growth rates of the entire bacterial community and the two populations were calculated as the slope of ln-transformed data of bacterial abundance versus time, assuming exponential growth. Growth rates of the entire bacterial community were also calculated from the increase of TdR incorporation (bacterial production) over time. Doubling time was calculated by dividing ln(2) by the growth rate.

TABLE 1.

DOC concentrations and viral abundances in the different DOM fractions at the start of the experiments

| Fraction | DOC (mg liter−1)a | Viral abundance (107 ml−1)b |

|---|---|---|

| LMW DOM | 4.2 ± 0.14 | 0.1 ± 0.03 |

| Virus-reduced TDOM | 9.2 ± 0.15 | 0.6 ± 0.06 |

| Virus-rich TDOM | 9.6 ± 0.13 | 1.7 ± 0.20 |

Values are means (± standard deviations) of three samples.

Values are means (± ranges) calculated from two incubations.

Determination of DOC.

Samples for DOC were collected after separation of lake water in the different DOM fractions and stored frozen (−20°C) until analysis. DOC concentrations were determined by the high-temperature combustion method (31) with a Shimadzu TOC-5000 analyzer with a platinum catalyst on quartz and performance of regular blank monitoring (7). Contamination of samples by leaching of carbon from the polycarbonate filters was less than 3%, and leaching from the filter cartridges was less than 1% of the DOC concentrations (data not shown).

Phenotypic characterization.

For API ZYM (Bio-Mérieux, Nürtingen, Germany), API 20 NE (Bio-Mérieux), and BIOLOG GN microplate (BIOLOG Inc., Hayward, Calif.) tests, strains were grown on nutrient broth agar medium (8 g liter−1; Difco Corp.) at 25°C for ca. 3 days. Bacterial biomass was scraped off the agar plates and resuspended in 0.85% NaCl. Tests for constitutive enzymes and metabolic profiles were done in duplicate at 25°C according to the manuals of the manufacturers.

The metabolic versatilities of the two strains were compared by calculating the ratio of the number of BIOLOG substrates used or enzymes expressed by PX54 to the number of BIOLOG substrates used or enzymes expressed by PU7718. As a measure of metabolic similarity, the niche overlap index (NOI) was calculated as the ratio of the number of substrates used by both strains to the total number of substrates used (42). Also, we determined the NOI for the enzyme expression, which was determined by API ZYM tests. It was recommended to use only those substrates for calculating NOI which are found in the environment (42). In natural waters, there are 24 substrates (24) that are represented in the BIOLOG plates (44). We used these substrates for calculating the metabolic versatility and NOI; however, similar trends were obtained when all used BIOLOG substrates were compared (data not shown). The comparison of metabolic versatility and the calculation of NOI were also done separately for several classes of organic matter, i.e., amino acids, carbohydrates, and fatty acids, as specified in reference 24. Although this concept was originally developed to determine the niche overlap of strains, we were more interested in quantifying the metabolic similarity between the two strains for the substrates tested.

Statistical analyses.

All data were log transformed for statistical analyses. Analysis of variance and Fisher’s protected least-significant-difference post hoc tests (StatView D 4.5 program) were used to test whether parameters were significantly different between the depth layers and the DOM fractions. A probability of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Depth distribution of bacteria.

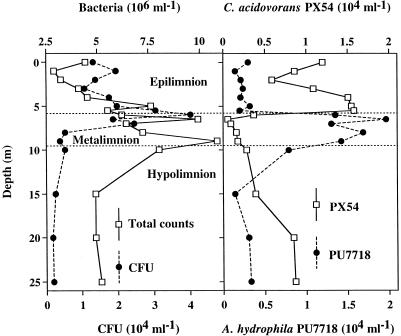

Temperature and oxygen profiles determined during the sampling period showed that the pelagic zone of Lake Plußsee was well stratified and separated into three distinct layers, the oxic epilimnion, the thermocline layer (metalimnion), and the anoxic hypolimnion (38). As determined by an analysis of variance, bacterial abundances of populations and communities differed significantly (P < 0.05 for all abundances) between the depth layers (Fig. 1). Total bacterial counts, CFU, and the abundance of A. hydrophila PU7718 were higher in the metalimnion than in the other depth layers, whereas maximum numbers of C. acidovorans PX54 bacteria were detected in the epilimnion. CFU were <1% of the total bacterial counts throughout the water column. From 5.5 to 5.75 m in depth, i.e., at the transition from the epilimnion to the metalimnion, the abundance of PX54 decreased from 1.6 × 104 to 0.4 × 104 cells ml−1 and the abundance of PU7718 increased dramatically from 0.2 × 104 to 1.4 × 104 cells ml−1. The abundance of PX54 ranged from 0.06 × 104 to 1.6 × 104 cells ml−1, and that of PU7718 ranged from 0.14 × 104 to 2.0 × 104 cells ml−1. The abundance of each of the two bacterial populations was less than 1% of total bacterial abundance. PX54 was rod shaped with an average cell length of ca. 3 μm, whereas PU7718 showed cocci or short rods typically of <1 μm.

FIG. 1.

Abundance of the entire bacterial community and the populations of C. acidovorans PX54 and A. hydrophila PU7718 in three depth layers of Lake Plußsee on 23 September 1996. Data for the characterization of water stratification and total bacterial abundance are taken from reference 38.

Growth of bacteria in different-size fractions of DOM.

Due to the fractionation treatment, viral abundances differed significantly (P < 0.05) between the treatments. Viral abundance was reduced to 34% in the virus-reduced fraction compared to the virus-rich TDOM fraction, whereas the viral number in the LMW DOM fraction was reduced to 5.0% (Table 1). The DOC concentrations differed significantly (P < 0.0001) between the DOM fractions. The DOC concentration in the LMW DOM fraction was 45% of the DOC concentration measured in the virus-rich TDOM fraction and did not differ strongly between the two TDOM fractions.

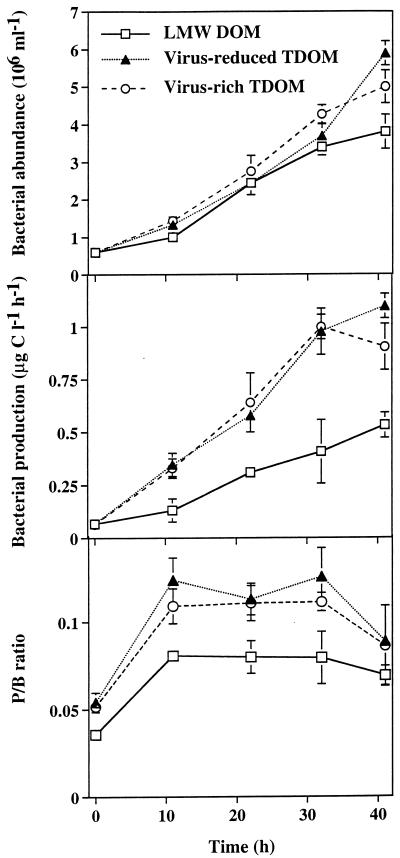

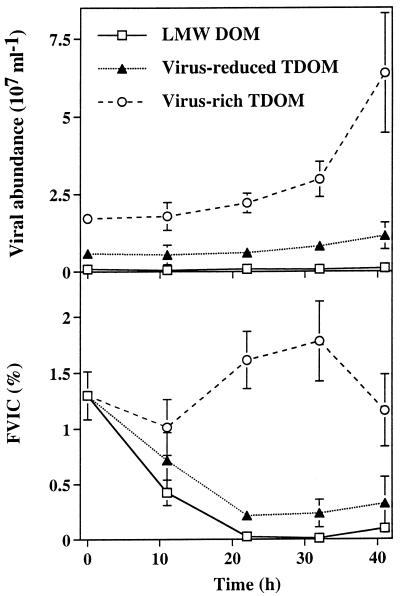

In all treatments, total bacterial abundance and production increased during the experiment (Fig. 2). At the end of the experiment, bacterial abundance and production were significantly (P < 0.05) higher in the virus-reduced TDOM fraction than in the LMW DOM fraction. Abundance and production of the entire bacterial community at the end of the experiments, corrected for values at the start of the experiment, were 17 to 19% lower in the virus-rich fraction than in the virus-reduced TDOM fraction. Throughout the experiment, the production-to-biomass ratio was higher in the TDOM fractions than in the LMW DOM fraction. Viral abundance increased rapidly in the virus-rich fraction and slowly in the virus-reduced TDOM fraction, whereas viral concentrations remained comparatively stable in the LMW DOM fraction (Fig. 3). At the start of the experiment, the FVICs was ca. 1.3% in all treatments. Later in the experiment, the FVICs varied between 1.0 and 1.8% in the virus-rich TDOM fraction and dropped to ca. 0.2 to 0.3% in the virus-reduced TDOM fraction and to <0.1% in the LMW DOM fraction. FVICs determined at the end of the experiments differed significantly (P < 0.05) between the treatments. We estimated that bacterial mortality due to viral lysis averaged 13 to 24% in the virus-rich TDOM fraction and 2 to 3% in the virus-reduced TDOM fraction.

FIG. 2.

Bacterial abundance and production in size fractions of DOM. P/B ratio, production-to-biomass ratio. Data are presented as means (± ranges) of duplicate incubations.

FIG. 3.

Viral abundance and FVICs in size fractions of DOM. Data are presented as means (± ranges) of duplicate incubations.

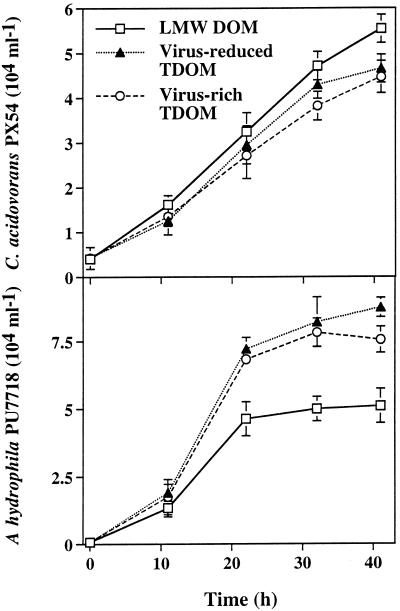

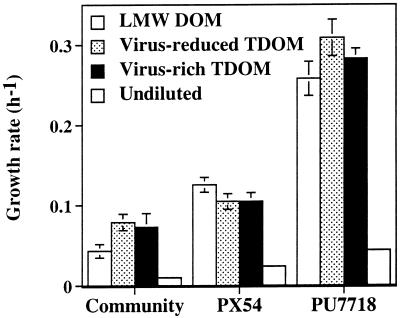

In all treatments, the abundance of C. acidovorans PX54 and A. hydrophila PU7718 increased during the experiment (Fig. 4). At the end of the experiment, PX54 was significantly (P < 0.05) more abundant in the LMW DOM fraction than in the two TDOM fractions, and the numbers did not differ between the two TDOM fractions. In contrast, the abundance of PU7718 was significantly (P < 0.05; ca. 30 to 40%) higher in the TDOM fractions than in the LMW DOM fraction. At the end of the experiment, the abundance of PU7718 was 14% lower in the virus-rich fraction than in the virus-reduced TDOM fraction. The effect of the treatments on the growth rates of the two populations in the different DOM fractions (Fig. 5) was comparable to the trends found for the abundance of populations but, however, not significant (P > 0.05). The highest growth rate of PX54 was estimated for the LMW DOM fraction, whereas PU7718 grew fastest in the TDOM fractions. The growth rate of PX54 (0.11 to 0.13 h−1 was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that of the entire bacterial community (0.04 to 0.08 h−1) but significantly lower (P < 0.05) than that of PU7718 (0.26 to 0.31 h−1). Doubling times ranged from 8.8 to 16.1 h in the entire bacterial community, from 5.5 to 6.6 h in PX54, and from 2.2 to 2.7 h in PU7718.

FIG. 4.

Abundance of the populations of C. acidovorans PX54 and A. hydrophila PU7718 in size fractions of DOM. Data are presented as means (± ranges) of duplicate incubations.

FIG. 5.

Growth rate of the entire bacterial community and the populations of C. acidovorans PX54 and A. hydrophila PU7718 in size fractions of DOM. Growth rates were calculated as the slope of ln-transformed data of bacterial abundance versus time. Data are presented as means (± ranges) of duplicate incubations.

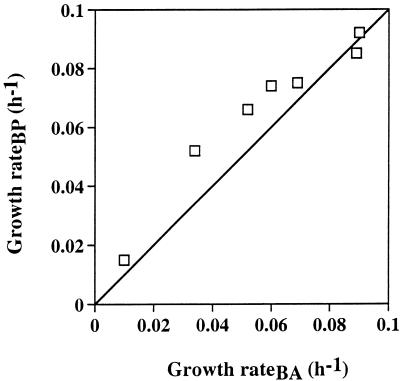

In undiluted cultures of bacterial populations and the community, the growth rates were significantly lower (P < 0.05 for the community and P < 0.01 for the populations) than those in dilution cultures. Thus, growth rate in undiluted cultures was 0.010 h−1 for the entire bacterial community, 0.024 h−1 for PX54, and 0.044 h−1 for PU7718, and doubling times were 69, 29, and 16 h, respectively. The ratio of growth rate in the dilution cultures (virus-rich TDOM) to the growth rate in the undiluted cultures was higher for the entire bacterial community (5.8 to 8.8) and for PU7718 (6.2 to 6.7) than for PX54 (3.9 to 5.0), indicating that dilution had a stronger effect on the growth rate of PU7718 and the entire bacterial community than on the growth rate of PX54. Growth rates of the bacterial community estimated from an increase of bacterial abundance and from production over time were correlated significantly (r2 = 0.933; P < 0.001) and were similar over ca. 1 order of magnitude (Fig. 6); growth rates determined from bacterial abundance averaged 84% of those made by using bacterial production.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of the growth rates in the natural bacterial community determined by using bacterial abundance (BA) and bacterial production (BP). Solid line, relationship of 1:1. r2 = 0.933.

Phenotypic characterization of bacterial strains.

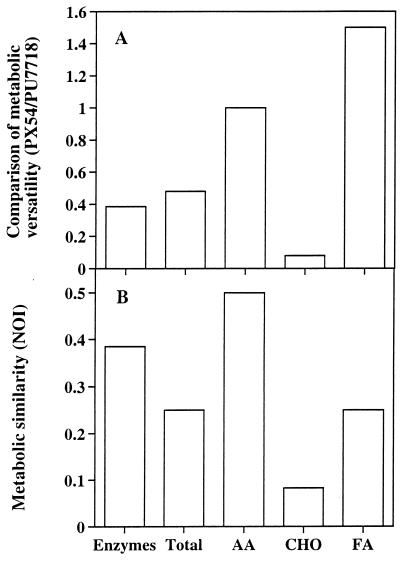

In contrast to C. acidovorans PX54, A. hydrophila PU7718 is fermentative and shows β-glucosidase and β-galactosidase activity. Growth of PU7718 could be detected in 11 (92%) of the 12 assimilation reactions compared to only 7 (58%) for PX54. A weak β-glucosidase and β-galactosidase activity of PU7718 was also confirmed by API ZYM testing. PU7718 showed positive reactions in 7 (37%) of 19 constitutive enzyme tests compared to 5 (26%) for PX54, and reactions were generally stronger for PU7718 than for PX54. In the BIOLOG tests, PU7718 demonstrated growth on 56 (59%) of 95 substrates compared to 30 (32%) for PX54. The comparison of metabolic versatilities indicated that PX54 expressed less enzyme and showed detectable growth on a lower number of total substrates and carbohydrates than did PU7718, whereas there was no difference between the two strains for the number of amino acids; however, PX54 could grow on more fatty acids than could PU7718 (Fig. 7A). NOI was lowest for carbohydrates and highest for amino acids (Fig. 7B), indicating that the metabolic similarity was ca. 50% for amino acids and <10% for carbohydrates.

FIG. 7.

Metabolic comparison and ecological similarity of the strains . C. acidovorans PX54 and A. hydrophila PU7718. BIOLOG and API ZYM test systems were used to assess metabolic versatilities of the two populations. Note that duplicates of BIOLOG plates and API ZYM strips showed the same results. Total, total substrates used; AA, amino acids; CHO, carbohydrates; FA, fatty acids. (A) Comparison of metabolic versatility of PX54 to that of PU7718, calculated as the ratio of the number of substrates used or enzymes expressed by PX54 to the number of substrates used or enzymes expressed by PU7718. (B) Metabolic similarity as determined by the NOI.

DISCUSSION

By using MAbs, we could demonstrate that populations of C. acidovorans PX54 showed a depth distribution in Lake Plußsee with maximum abundances in the oxic epilimnion, whereas A. hydrophila PU7718 showed a depth distribution with maximum abundances in the anoxic thermocline layer (metalimnion), i.e., in the water layer with the highest microbial activity. Resistance of PX54 to protist grazing and high metabolic versatility and growth rate of PU7718 were the most important life strategy traits for explaining the depth distribution of the two bacterial populations. Characterizations of life strategies showed that on a relative scale PX54 can be described as a K-strategist or equilibrium population and PU7718 can be described as an r-strategist or opportunistic population in Lake Plußsee. The use of MAbs also allowed for an estimation of growth rates of indigenous bacterial populations.

Concentration and reactivity of DOC in different size fractions of DOM.

The DOC concentration in the LMW DOM fraction was ca. 45% of that in the TDOM fractions. This value falls within the range of values (ca. 10 to 70%) reported from freshwater and marine systems (4). Amon and Benner (3, 4) determined bacterial growth in the DOM fractions <1 kDa and >1 kDa that were enriched with inorganic nutrient species and found that the rates of bacterial growth and respiration were higher in the >1-kDa than in the <1-kDa incubation samples. In our study, we used filtration of lake water through filters of different pore sizes instead of separating DOM into LMW and HMW fractions. By using this treatment, we have avoided amending incubation samples with inorganic nutrient species which could have affected bacterial community structure and growth of the bacterial populations. The finding that the growth rate and the production/biomass ratio of bacterioplankton were higher in the TDOM fractions than in the LMW DOM fraction indicates that HMW DOM is more bioreactive than LMW DOM and thus supports earlier findings (3, 4, 33).

Growth of bacteria in different size fractions of DOM.

Since abundance and production of the entire bacterial community were 17 to 19% lower in the virus-rich fraction than in the virus-reduced TDOM fraction and the estimated bacterial mortality due to viral lysis was 13 to 24% in the virus-rich TDOM fraction but only 2 to 3% in the virus-reduced TDOM fraction, it is likely that the difference between the two TDOM fractions was due to viral lysis. The abundance of C. acidovorans PX54 did not differ between the TDOM fractions, whereas the number of A. hydrophila PU7718 bacteria was lower in the virus-rich fraction than in the virus-reduced TDOM fraction. Assuming that the difference in PU7718 abundance between the two TDOM fractions was caused by mortality due to viruses, viral lysis removed 14% of the PU7718 cells.

Abundance and growth rate of C. acidovorans PX54 were highest in the LMW DOM fraction, which is less bioreactive for the entire bacterial community. Support for this comes from the fact that isolates of C. acidovorans can degrade recalcitrant substrates such as oil-derived wastes (1). Although a low competitive ability for the utilization of less-recalcitrant HMW DOM compounds compared to that for average bacterioplankton could be another reason for the low numbers of PX54 in the TDOM fractions, it is unlikely that competition was significant in our experiments, since we inoculated the natural bacterial community at a final concentration of only 10%.

Enzymatic and metabolic profiles indicate that A. hydrophila PU7718 can grow on more test substrates and express a larger variety of constitutive enzymes than C. acidovorans PX54 (Fig. 7). The ability to use a large variety of substrates could explain why the growth rate of PU7718 on a complex substrate such as DOM was higher than that of PX54. Moreover, high concentrations of labile DOM in the epilimnion (see below) might have allowed for high growth rates of PU7718. In lake water mesocosms which were amended with a nutrient broth medium consisting of a complex mixture of amino acids, peptides, and proteins, A. hydrophila as identified by LMW RNA community fingerprinting showed a bloom and the abundance of this species was ca. five times higher than that in unamended mesocosms, whereas C. acidovorans did not bloom (20, 21).

The growth rate of the entire bacterial community and bacterial populations was significantly higher in dilution cultures than in undiluted cultures (Fig. 5). The most probable reason for this is density effects such as resource limitation or antibiosis. Resource limitation in undiluted cultures is likely at some point, since they are closed systems and new photosynthetic carbon fixation was prevented by keeping the incubation samples in the dark. Protozoan grazing may have contributed to the low growth rates in undiluted cultures; however, since growth rates were determined during the logarithmic growth phase and an increase of protozoan abundance was observed only at the end of the experiment (data not shown), a strong influence of grazing seems unlikely. A comparison of growth rates in undiluted and dilution cultures demonstrated that density effects were less important for PX54 than for PU7718 or the entire bacterial community, indicating a higher competitive ability of PX54.

During a seasonal study in Lake Plußsee, growth rates of the entire bacterial community determined in dilution cultures by using TdR and leucine incorporation ranged from ca. 0.01 to 0.1 h−1 (10). The estimation of growth rates of the entire bacterial community in our dilution cultures ranged from 0.04 to 0.08 h−1 and was thus within the range reported for Lake Plußsee. The growth rates determined from an increase of bacterial abundance over time were similar to those made by using an increase of bacterial production over time (Fig. 6), indicating that the enumeration of bacterial abundance in dilution cultures can be used as a good proxy to estimate growth rates. This conclusion also supports the use of carefully selected MAbs to estimate the growth rate of bacterial populations.

Depth distribution of bacterial populations.

Data from a previous study conducted at the onset of the water stratification in spring (14) and from our study performed in early fall demonstrate a pronounced depth distribution of the two populations during water stratification. The highest abundance of A. hydrophila PU7718 was detected in the metalimnion, and C. acidovorans PX54 predominated in the epilimnion. In Lake Plußsee, the highest proportion of labile DOM is found in the epilimnion and metalimnion, whereas the DOM in the hypolimnion is a refractory carbon skeleton depleted of nitrogen and phosphorus (25). Photosynthetic extracellular release, leakage from senescent cells, destruction of phytoplankton cells by sloppy feeding, and viral lysis are major sources of labile DOM. Also, bacteria seem to be an important source of DOM, e.g., by the release of exopolymers (12) or the disruption of cells during viral lysis. The metalimnion probably showed the highest concentrations of labile organic substrates during the investigation period, since chlorophyll a concentrations and bacterial abundance and production were high in this water layer (Fig. 1) (38).

In lake water mesocosms that were amended with nutrients, a bloom of A. hydrophila which was removed rapidly by grazing occurred, whereas C. acidovorans was probably not strongly affected by nutrient addition or grazing (20, 21). In chemostat studies, it was demonstrated that increasing the cell size is a strategy of PX54 to avoid grazing, whereas no such strategy was found for PU7718 (18, 19). PX54 was more than three times larger than PU7718 in our study (see also Fig. 5 or reference 14), and grazing rates were high in the epilimnion during the investigation period (38). Thus, grazing resistance might explain the finding that the abundance of A. hydrophila PU7718 in this water layer was lower than the numbers of C. acidovorans PX54, although the growth rate of PU7718 was higher than that of PX54 in incubations with epilimnetic water. In the metalimnion, the low control by grazing during the investigation period (38) might explain the high numbers of the fast-growing A. hydrophila PU7718, whereas the low numbers of PX54 in this water layer might result from the low growth rates of this population or from grazing of daphnids on the large PX54 cells.

In the epilimnion and metalimnion of Lake Plußsee, monomeric carbohydrates and labile polymeric carbohydrates cleaved by β-glucosidase and β-galactosidase represent a major contribution to bacterial nutrition, whereas the contribution of carbohydrates to total DOM decreases below the thermocline (25). The finding that the metabolic similarity between the two strains was lowest for simple carbohydrates (Fig. 7B) and that PX54 could use only 8% of the simple carbohydrates used by PU7718 (Fig. 7A) indicates that the availability of carbohydrates could have influenced the depth distribution of the two populations. Carbohydrates might be an important carbon source for PU7718 and contribute to its high abundance in the metalimnion, whereas a low utilization of carbohydrates could cause the low numbers of PX54. Moreover, the constitutive expression of β-glucosidase and β-galactosidase may help PU7718 to sequester carbon from polymeric DOM and sustain high abundances in the metalimnion. Although the ecological similarity of the amino acids used is only 50% for the two strains (Fig. 7B), the number of amino acids used which are relevant in aquatic systems is the same for both strains (Fig. 7A), indicating that the use of amino acids was probably less important for explaining the different depth distributions. PX54 could grow on more fatty acids than PU7718; however, since the concentrations of fatty acids are very low in Lake Plußsee (25), it is unlikely that fatty acids contributed to the depth distribution of the two populations. Although we used only those BIOLOG substrates that are found in natural waters, it has to be considered that these substrates might not be representative for Lake Plußsee. The reason for the decrease of PU7718 and the increase of PX54 below the metalimnion remains unknown; however, the recalcitrant DOM and the low concentrations of carbohydrates might sustain cell abundances that are higher for PX54 than for PU7718.

The maximum abundance of C. acidovorans PX54 found by Faude and Höfle (14) in lake Plußsee was <5 × 103 ml−1, and the maximum concentration of A. hydrophila PU7718 was 8.9 × 103 ml−1, compared to 16 × 103 and 20 × 103 ml−1, respectively, in our study. PX54 and PU7718 were isolated in spring 1990 and still detected 3 years later by using MAbs (14). Our data show that both populations could be found in large numbers more than 6 years after their isolation. Assuming that the growth rates in the undiluted cultures are representative for the two populations, C. acidovorans PX54 was present in Lake Plußsee for ca. 900 generations and A. hydrophila PU7718 was present for ca. 3,400 generations. This indicates a strong stability of bacterial community structure at the population level. A stability of the population structure over 1 year was also demonstrated recently for a set of marine strains of Shewanella putrefaciens by using DNA fingerprinting (45).

Life strategies of bacterial populations.

A compilation of life strategy traits (including data from literature) of C. acidovorans PX54 and A. hydrophila PU7718 is presented in Table 2. PX54 showed lower growth rates and a lower metabolic versatility for the substrates and enzymes tested than did PU7718 but could grow better on refractory DOM and was less influenced by density effects and more resistant to grazing by protozoans (and maybe also viral lysis). The amendment of mesocosms with organic nutrients stimulated a bloom of A. hydrophila but not of C. acidovorans as identified by LMW RNA community fingerprinting (20, 21). Later in this experiment, grazing strongly reduced A. hydrophila but not C. acidovorans. This indicates that the species to which PX54 and PU7718 belong show some life strategy traits that are similar to those of the populations selected in this study. Thus, the data on populations may also have some potential to explain the distribution of these two species that are abundant in Lake Plußsee and other lakes (13). Overall, along the r/K selection continuum PU7718 is rather an r-strategist or opportunistic population in Lake Plußsee and PX54 behaves like a K-strategist or equilibrium population.

TABLE 2.

Some life strategy features of C. acidovorans PX54 and A. hydrophila PU7718

| Traita | Method | Evaluation of straine:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| PX54 | PU7718 | ||

| Growth rate | Dilution culture, mesocosmb | Low | High |

| Effect of dilution on growth rate | Dilution culture | Low | High |

| Ability to utilize refractory DOM | Dilution culture | High | Low |

| Nutritional range | Metabolic fingerprintc | Low | High |

| Range of expressed enzymes | Metabolic fingerprintc | Low | High |

| Resistance to predation-lysis | Dilution culture, chemostat,d mesocosmb | High | Low |

Implications.

Our data show that bacterial populations can differ strongly with respect to growth rates and responses to size fractions of DOM and also deviate from average bacterioplankton. Thus, bulk measurements of bacterial parameters mask the complex and manifold performances and interactions of populations within the bacterioplankton community. By using MAbs, we determined the depth distribution and abundance of bacterial populations, and we can also offer an explanation for their distribution and abundance based on the characterization of life strategies. Moreover, we could estimate the growth rate of indigenous bacterial populations growing along with the bacterial community, which provides for more realistic scenarios. Thus, taxonomic probes used in situ and in experimental studies have a great potential for explaining the distribution and abundance of populations and investigating their control mechanisms such as grazing, viral lysis, and quality and quantity of DOM.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank W. Lampert and D. Albrecht at the Max Planck Institute for Limnology in Plön for providing laboratory space and “ballerina” Katja Dominik for help during field and laboratory work. The help of Heinrich Lünsdorf with electron microscopy and that of Michael Tesar, Christiane Beckmann, and Pia Weidlich with antibodies is acknowledged. We also thank Gerhard J. Herndl and Ingrid Kolar for organic carbon analyses. The comments of two referees improved the manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant (BEO-0319433B) of the Bundesministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft, Forschung und Technologie to M.G.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aislabie J, Richards N K, Lyttle T C. Description of bacteria able to degrade isoquinoline in pure culture. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40:555–560. doi: 10.1139/m94-089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amon R M W, Benner R. Rapid cycling of high-molecular-weight dissolved organic matter in the ocean. Nature. 1994;369:549–552. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amon R M W, Benner R. Bacterial utilization of different size classes of dissolved organic matter. Limnol Oceanogr. 1996;41:41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews J H, Harris R F. r- and K-selection and microbial ecology. Adv Microb Ecol. 1986;9:99–147. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benner R. Ultrafiltration for the concentration of bacteria, viruses, and dissolved organic matter. In: Hurde D C, Spencer D W, editors. Marine particles: analysis and characterization. Washington, D.C: American Geophysical Union; 1991. pp. 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benner R, Strom M. A critical evaluation of the analytical blank associated with DOC measurements by high-temperature catalytic oxidation. Mar Chem. 1993;41:153–160. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brettar L, Höfle M G. Influence of ecosystematic factors of survival of Escherichia coli after large-scale release into lake water mesocosms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2201–2210. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.7.2201-2210.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell L, Carpenter E J, Iacono V J. Identification and enumeration of marine chroococcoid cyanobacteria by immunofluorescence. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46:553–559. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.3.553-559.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chróst R J, Rai H. Bacterial secondary production. In: Overbeck J, Chróst R J, editors. Microbial ecology of Lake Plußsee. New York, N.Y: Springer; 1994. pp. 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahle A B, Laake M. Diversity dynamics of marine bacteria studied by immunofluorescence staining on membrane filters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:169–176. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.1.169-176.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decho A W. Microbial exopolymer secretions in ocean environments: their role(s) in food webs and marine processes. Oceanogr Mar Biol Annu Rev. 1990;28:73–153. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dominik K. Vergleichende 5S rRNA-Analyse der zeitlichen und räumlichen Dynamik von Bakterioplankton aus dem Pluflsee und anderen ostholsteinischen Seen. Ph.D. thesis. Braunschweig, Germany: Technical University of Braunschweig; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faude U C, Höfle M G. Development and application of monoclonal antibodies for in situ detection of indigenous bacterial strains in aquatic ecosystems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4534–4542. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4534-4542.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuhrman J A. Community structure: bacteria and archaea. In: Hurst C J, Knudsen G R, McInerney M J, Stetzenbach L D, Walter M V, editors. Manual of environmental microbiology. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1997. pp. 278–283. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuhrman J A, Azam F. Bacterioplankton secondary production estimates for coastal waters of British Columbia, Antarctica, and California. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;39:1085–1095. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.6.1085-1095.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuhrman J A, Suttle C A. Viruses in marine planktonic systems. Oceanography. 1993;6:51–63. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn M. Experimentelle Untersuchungen zur Interaktion von bakterivoren Nanoflagellaten mit planktischen Bakterien. Ph.D. thesis. Braunschweig, Germany: Technical University of Braunschweig; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hahn M W, Höfle M G. Grazing pressure by a bacterivorous flagellate reverses the relative abundance of Comamonas acidovorans PX54 and Vibrio strain CB5 in chemostat cocultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1910–1918. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1910-1918.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Höfle M G. Bacterioplankton community structure and dynamics after large-scale release of nonindigenous bacteria as revealed by low-molecular-weight-RNA analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3387–3394. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.10.3387-3394.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Höfle, M. G. Direct detection of nutrient induced changes in the community structure of bacterioplankton using low-molecular-weight RNA analysis. Adv. Limnol., in press.

- 22.Krambeck H-J, Albrecht D, Hickel B, Hofmann W, Arzbach H-H. Limnology of the Plußsee. In: Overbeck J, Chróst R J, editors. Microbial ecology of Lake Plußsee. New York, N.Y: Springer; 1994. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S, Fuhrman J A. Relationships between biovolume and biomass of naturally derived marine bacterioplankton. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1298–1303. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.6.1298-1303.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lock M A. Dynamics of particulate and dissolved organic matter over the substratum of water bodies. In: Wotton R S, editor. The biology of particles in aquatic systems. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, Fla: Lewis Publishers; 1994. pp. 137–160. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Münster U, Albrecht D. Dissolved organic matter: analysis of composition and function by a molecular-biochemical approach. In: Overbeck J, Chróst R J, editors. Microbial ecology of Lake Plußsee. New York, N.Y: Springer; 1994. pp. 24–62. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pianka E T. Evolutionary ecology. New York, N.Y: Harper & Row; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proctor L M, Okubo A, Fuhrman J A. Calibrating estimates of phage-induced mortality in marine bacteria: ultrastructural studies of marine bacteriophage development from one-step growth experiments. Microb Ecol. 1993;25:161–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00177193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reed W M, Dugan P R. Distribution of Methylomonas methanica and Methylosinus trichosporium in Cleveland Harbor as determined by an indirect fluorescent antibody-membrane filter technique. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:422–430. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.2.422-430.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simek K, Vrba J, Pernthaler J, Posch T, Hartman P, Nemoda J, Psenner R. Morphological and compositional shifts in an experimental bacterial community influenced by protists with contrasting feeding modes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:587–595. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.587-595.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stahl D A. Molecular approaches for the measurement of density, diversity, and phylogeny. In: Hurst C J, Knudsen G R, McInerney M J, Stetzenbach L D, Walter M V, editors. Manual of environmental microbiology. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1997. pp. 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugimura Y, Suzuki Y. A high-temperature catalytic oxidation method for the determination of non-volatile dissolved organic carbon in seawater by direct injection of a liquid sample. Mar Chem. 1988;24:105–131. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thingstad T F, Heldal M, Bratbak G, Dundas I. Are viruses important partners in pelagic food webs? Trends Ecol Evol. 1993;8:209–213. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(93)90101-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tranvik L J. Bacterioplankton growth on fractions of dissolved organic carbon of different molecular weights from humic and clear waters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1672–1677. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1672-1677.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tuomi P, Torsvik T, Heldal M, Bratbak G. Bacterial population dynamics in a meromictic lake. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2181–2188. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2181-2188.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ward B B, Carlucci A F. Marine ammonia- and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria: seriological diversity determined by immunofluorescence in culture and in the environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50:194–201. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.2.194-201.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ward B B, Cockcroft A R. Immunofluorescence detection of the denitrifying strain Pseudomonas stutzeri (ATCC 14405) in seawater and intertidal sediment environments. Microb Ecol. 1993;25:233–246. doi: 10.1007/BF00171890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinbauer M G, Höfle M G. Size-specific mortality of lake bacterioplankton by natural virus communities. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1998;156:103–113. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinbauer M G, Höfle M G. Significance of viral lysis and flagellate grazing as factors controlling bacterioplankton production in a eutrophic lake. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:431–438. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.431-438.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinbauer M G, Peduzzi P. Frequency, size and distribution of bacteriophages in different marine bacterial morphotypes. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1994;108:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weinbauer M G, Suttle C A. Potential significance of lysogeny to bacteriophage production and bacterial mortality in coastal waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4374–4380. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4374-4380.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinbauer M G, Suttle C A. Comparison of epifluorescence and transmission electron microscopy for counting viruses and bacteria in natural marine waters. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1997;13:225–232. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson M, Lindow S E. Ecological similarity and coexistence of epiphytic ice-nucleating (Ice+) Pseudomonas syringae strains and a non-ice-nucleating (Ice−) biological control agent. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3128–3137. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3128-3137.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zambon J J, Huber P S, Meyer A E, Slots J, Fornalik M S, Baier R E. In situ identification of bacterial species in marine microfouling films by using an immunofluorescence technique. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:1214–1220. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.6.1214-1220.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ziemke F. Entwicklung einer artspezifischen Screeningstrategie für Shewanella putrefaciens und Abschätzung der genetischen Diversität der Art mit Hilfe molekularer Fingerabrücke. Ph.D. thesis. Braunschweig, Germany: Technical University of Braunschweig; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ziemke F, Brettar I, Höfle M G. Stability and diversity of the genetic structure of a Shewanella putrefaciens population in the water column of the central Baltic. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1997;13:63–74. [Google Scholar]