This cross-sectional study examines the factors related to social determinants of health that are associated with visiting an eye care practitioner among patients with type 2 diabetes.

Key Points

Question

What factors related to social determinants of health, including sociodemographics, self-reported health, and health care access, are associated with visiting an eye care professional among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D)?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 11 551 participants with T2D from the All of Us Research Program, practitioner concordance, food or housing insecurity, and mental health were associated with receiving eye care.

Meaning

These findings highlight the complex barriers associated with seeking eye care among patients with T2D and the importance of taking steps to promote health equity and physician diversity.

Abstract

Importance

Regular screening for diabetic retinopathy often is crucial for the health of patients with diabetes. However, many factors may be barriers to regular screening and associated with disparities in screening rates.

Objective

To evaluate the associations between visiting an eye care practitioner for diabetic retinopathy screening and factors related to overall health and social determinants of health, including socioeconomic status and health care access and utilization.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cross-sectional study included adults aged 18 years or older with type 2 diabetes who answered survey questions in the All of Us Research Program, a national multicenter cohort of patients contributing electronic health records and survey data, who were enrolled from May 1, 2018, to July 1, 2022.

Exposures

The associations between visiting an eye care practitioner and (1) demographic and socioeconomic factors and (2) responses to the Health Care Access and Utilization, Social Determinants of Health, and Overall Health surveys were investigated using univariable and multivariable logistic regressions.

Main Outcome and Measures

The primary outcome was whether patients self-reported visiting an eye care practitioner in the past 12 months. The associations between visiting an eye care practitioner and demographic and socioeconomic factors and responses to the Health Care Access and Utilization, Social Determinants of Health, and Overall Health surveys in All of Us were investigated using univariable and multivariable logistic regression.

Results

Of the 11 551 included participants (54.55% cisgender women; mean [SD] age, 64.71 [11.82] years), 7983 (69.11%) self-reported visiting an eye care practitioner in the past year. Individuals who thought practitioner concordance was somewhat or very important were less likely to have seen an eye care practitioner (somewhat important: adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 0.83 [95% CI, 0.74-0.93]; very important: AOR, 0.85 [95% CI, 0.76-0.95]). Compared with financially stable participants, individuals with food or housing insecurity were less likely to visit an eye care practitioner (food insecurity: AOR, 0.75 [95% CI, 0.61-0.91]; housing insecurity: AOR, 0.86 [95% CI, 0.75-0.98]). Individuals who reported fair mental health were less likely to visit an eye care practitioner than were those who reported good mental health (AOR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74-0.96).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found that food insecurity, housing insecurity, mental health concerns, and the perceived importance of practitioner concordance were associated with a lower likelihood of receiving eye care. Such findings highlight the self-reported barriers to seeking care and the importance of taking steps to promote health equity.

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a microvascular complication of diabetes affecting the small blood vessels in the retina, and it is the primary reason for blindness in working-age adults residing in the US.1 Approximately 28% of adults with diabetes in the US have DR.1 The importance of DR screening is emphasized by the fact that interventions, such as laser photocoagulation, vitrectomy, and intravitreal injection of anti–vascular endothelial growth factor, are associated with reductions in severe vision loss by 90%.2,3 Current screening guidelines recommend that patients with diabetes visit an eye care practitioner to undergo a visual acuity and retinal examination. The Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set—an important tool that measures performance on health care quality and service—includes eye examinations as part of comprehensive diabetes care.3 Guidelines from the American Academy of Ophthalmology recommend that patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) undergo annual screening for DR starting immediately on diagnosis.4

Numerous studies have examined factors associated with reduced DR screening rates among patients with diabetes.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 Such factors encompass younger age,5 minority racial or ethnic group,5,11,12 lower levels of income or education,5 neighborhood deprivation,7,13 and unfavorable housing conditions.10,13 While previous research has acknowledged various socioeconomic variables that are associated with lower adherence to DR screening, few studies have delved into patients’ perspectives to elucidate the reasons behind this discrepancy.13,14 Studies that analyze the effects of patient-reported factors for eye conditions and social determinants of health (SDOH) are prevalent, but studies focusing on these topics in DR screening are sparse.15,16,17,18

The All of Us Research Program, funded and administered by the National Institutes of Health, presents a promising opportunity for investigating these issues.19 The platform provides extensive health information from over a quarter million individuals across the US and self-reported survey data. The research program also emphasizes rigorous efforts to capture a diverse population that includes groups traditionally underrepresented in research to position researchers to better understand and adequately tackle health disparities.20 All of Us serves as an ideal platform for examining patterns of DR screening and overcomes limitations of previous studies by including patient information on SDOH not typically found in electronic health records and claims-based data sets. The goal of this study was to evaluate the associations between visiting an eye care practitioner for DR screening and various factors related to overall health and SDOH, including socioeconomic status and health care access and utilization, captured in the All of Us Research Program.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study using the All of Us Research Program to assess the differences in demographics, overall health, and SDOH, including socioeconomic status, between patients with T2D who did and did not self-report seeing an eye practitioner in the previous year. Because of use of deidentified data, this study was exempt from Stanford University institutional review board approval. Participants in the All of Us program undergo a rigorous informed consent process to contribute their data to All of Us. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki21 and followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies.22

Data Source

The All of Us Research Program provides a longitudinal database encompassing clinical, environmental, and lifestyle factors for over a quarter million individuals residing in the US. Individuals aged 18 years or older who reside in the US can participate in the program either through the program’s website or via more than 60 health care organizations. Data are collected from various sources, such as electronic health records and surveys. On completion of the core surveys (The Basics, Lifestyle, and Overall Health surveys), participants are invited to complete additional optional surveys, such as the Health Care Access and Utilization (HCAU) and Social Determinants of Health surveys. Although health care access and socioeconomic status fall under the Healthy People 203023 framework definition of SDOH, the All of Us Research Program collects and shares these data in separate surveys; thus, they are referred to by their survey herein. The clinical encounters include diagnosis codes based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision as well as the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine, all of which are mapped to the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Common Data Model24 for observational health data.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

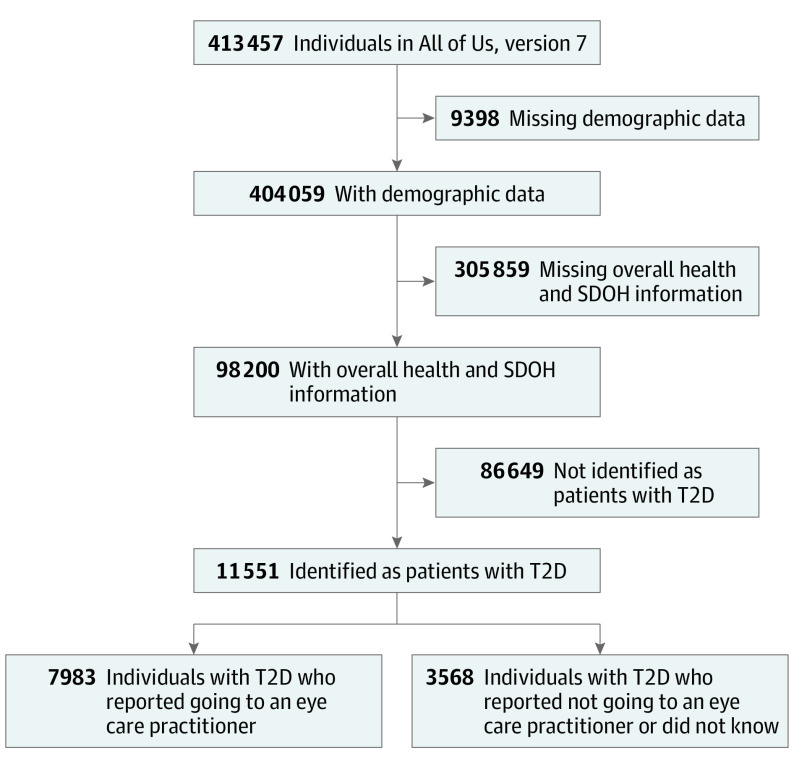

This study included patients from the All of Us, version 7 cohort, the latest data release as of the time of this analysis, which included data from participants enrolled from May 1, 2018, to July 1, 2022. Participants with T2D who answered a survey question on whether or not they visited an eye care practitioner in the past year were identified. Survey questions could be completed at the time of study enrollment or subsequently. We defined patients with T2D as individuals who self-reported taking medications for T2D or whose electronic health records indicated that they had at least 1 condition related to T2D and were prescribed medications used for diabetes (eTable 1 in Supplement 1 gives related concept codes). We considered only diagnoses and prescriptions recorded before the patient answered whether they visited an eye care practitioner. This ensured that patients had a diagnosis of T2D before they answered the survey question. Participants who were missing demographic information or who did not answer questions from the HCAU, SDOH, and Overall Health surveys were excluded. The cohort design for the study population is summarized in the Figure.

Figure. Cohort Construction Diagram.

SDOH indicates social determinants of health; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was whether patients self-reported visiting an eye care practitioner in the past 12 months, as answered on the survey question: “During the past 12 months, have you seen or talked to any of the following health care providers about your own health?...An optometrist, ophthalmologist, or eye doctor (someone who prescribes eyeglasses).” The responses of “yes,” “no,” or “don’t know” were dichotomized as yes and no or don’t know.

Measures

Primary variables included information from The Basics, SDOH, HCAU, and Overall Health surveys. The survey on HCAU gathers data on participants’ health care access and utilization, such as remoteness of health care access, health literacy, and beliefs about practitioner concordance on race and ethnicity and other factors. The SDOH survey collects information on factors including food insecurity and whether participants speak a language other than English at home. The Overall Health survey collects participants’ reported levels of overall general health, physical and mental health, and quality of life. The full text of the questions investigated in this study, participants’ answer choices, and short descriptions by which we refer to these questions are listed in eTable 2 in Supplement 1.

Information about demographics and additional covariates were identified from The Basics survey. Age was considered as a continuous covariate. Race and ethnicity were categorized as Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, other race or ethnicity, and unknown. Race and ethnicity were ascertained through self-reported surveys from The Basic surveys within All of Us. Other race and ethnicity included Middle Eastern or North African, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and none of these. Race and ethnicity were important to include in this study given the association between race and ethnicity and adherence to DR screening previously reported in the literature. Education was categorized as did not graduate high school, high school graduate or General Equivalency Development, some college, college graduate, advanced degree, and unknown. Gender was categorized as cisgender man, cisgender woman, nonbinary or transgender, and unknown using the 2-step process from Reisner et al.25 Sexual orientation was categorized as straight or heterosexual, other, and unknown. The groups included as other were bisexual; gay or lesbian; queer; poly-, omni-, sapio-, or pansexual; asexual; 2-spirit; not figured out; mostly straight; no sexuality; no labels; and something else. Income was categorized as less than $25 000, $25 000 to $49 999, $50 000 to $74 999, $75 000 to $99 999, $100 000 to $149 999, $150 000 or more, and unknown. Relationship status was categorized as married or living together, never married, widowed, divorced or separated, and unknown. Insurance coverage was categorized as yes, no, and unknown.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were summarized with means (SDs) and compared using the t test. Categorical variables were summarized with frequencies (percentage) and compared using the χ2 test. Univariable (unadjusted) and multivariable (adjusted) logistic regression models were constructed to investigate factors associated with visiting an eye care practitioner in the past year among patients with T2D. Adjusted logistic regression included age, race and ethnicity, educational level, gender, sexual orientation, employment status, income, relationship status, and insurance coverage as covariates. Analysis-of-variance inflation factors confirmed absence of multicollinearity. Per National Institutes of Health All of Us policies aimed at reducing risk of reidentification of study participants, cell sizes with less than 20 individuals (and their corresponding percentages) are suppressed. For all results, P values were 2 sided and were not adjusted for multiple analyses; P < .05 was considered significant.

Data preparation was performed using pandas, version 1.3.5 and NumPy, version 1.21.6 in Python, version 3.7.12 (Python Software Foundation). Logistic regression models were constructed using R, version 4.2.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

In the study cohort of 11 551 participants with T2D, 7983 (69.11%) participants reported having visited an eye care practitioner in the past year. Table 1 summarizes the population characteristics of participants with T2D. The overall mean (SD) age was 64.71 (11.82) years; 5109 participants (44.23%) were cisgender men, 6301 (54.55%) were cisgendered women, 49 (0.42%) were nonbinary or transgender, and 192 (1.66%) had unknown gender. A total of 1007 participants (8.72%) were Hispanic; 225 (1.95%), non-Hispanic Asian; 1573 (13.62%), non-Hispanic Black; 8294 (71.80%), non-Hispanic White, 210 (1.81%), other race and ethnicity; and 242 (2.10%) unknown race and ethnicity. A total of 3311 participants (28.66%) were employed for wages, and 4456 (38.58%) reported a household income of less than $50 000.

Table 1. Demographic Population Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Individualsa | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visited an ECP (n = 7983) | Did not visit an ECP or did not know (n = 3568) | Total (N = 11 551) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 65.08 (11.58) | 63.89 (12.29) | 64.71 (11.82) | <.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Cisgender man | 3698 (46.32) | 1411 (39.55) | 5109 (44.23) | <.001 |

| Cisgender woman | 4197 (52.57) | 2104 (58.97) | 6301 (54.55) | |

| Nonbinary or transgender | 33 (0.41) | <20 | 49 (0.42) | |

| Unknown | 55 (0.69) | 37 (1.03) | 192 (1.66) | |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 642 (8.04) | 365 (10.23) | 1007 (8.72) | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 176 (2.20) | 49 (1.37) | 225 (1.95) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 998 (12.50) | 575 (16.12) | 1573 (13.62) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 5857 (73.37) | 2437 (68.30) | 8294 (71.80) | |

| Otherb | 144 (1.80) | 66 (1.85) | 210 (1.81) | |

| Unknown | 166 (2.08) | 76 (2.13) | 242 (2.10) | |

| Educational level | ||||

| Did not graduate high school | 259 (3.24) | 194 (5.44) | 453 (3.92) | <.001 |

| High school graduate or GED | 885 (11.09) | 553 (15.50) | 1438 (12.45) | |

| Some college | 2452 (30.72) | 1266 (35.48) | 3718 (32.19) | |

| College graduate or above | 2153 (26.97) | 819 (22.95) | 2972 (25.73) | |

| Advanced degree | 2129 (26.67) | 687 (19.25) | 2816 (24.38) | |

| Unknown | 105 (1.32) | 49 (1.37) | 154 (1.33) | |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Straight or heterosexual | 7155 (89.63) | 3206 (89.85) | 10 361 (89.70) | .37 |

| Otherc | 664 (8.32) | 287 (8.04) | 951 (8.33) | |

| Unknown | 144 (1.83) | 75 (2.11) | 219 (1.97) | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed for wages | 2335 (29.25) | 976 (27.35) | 3311 (28.66) | <.001 |

| Self-employed | 375 (4.70) | 178 (4.99) | 553 (4.79) | |

| Out of work or unable to work | 1480 (18.54) | 792 (22.20) | 2272 (19.67) | |

| Retired | 3442 (43.12) | 1422 (39.85) | 4864 (42.11) | |

| Other | 269 (3.37) | 137 (3.84) | 406 (3.51) | |

| Unknown | 82 (1.03) | 63 (1.77) | 145 (1.26) | |

| Income, $ | ||||

| <25 000 | 1387 (17.37) | 863 (24.19) | 2250 (19.48) | <.001 |

| 25 000-49 999 | 1465 (18.35) | 741 (20.77) | 2206 (19.10) | |

| 50 000-74 999 | 1267 (15.87) | 548 (15.36) | 1815 (15.71) | |

| 75 000-99 999 | 1005 (12.59) | 351 (9.84) | 1356 (11.74) | |

| 100 000-149 999 | 1191 (14.92) | 371 (10.40) | 1562 (13.52) | |

| ≥150 000 | 826 (10.35) | 239 (6.70) | 1065 (9.22) | |

| Unknown | 842 (10.55) | 455 (12.75) | 1297 (11.23) | |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Married or living with partner | 4716 (59.08) | 1861 (52.16) | 6577 (56.94) | <.001 |

| Never married | 1134 (14.21) | 533 (14.94) | 1667 (14.43) | |

| Widowed | 641 (8.03) | 357 (10.01) | 998 (8.64) | |

| Divorced or separated | 1410 (17.66) | 756 (21.19) | 2166 (18.75) | |

| Unknown | 82 (1.03) | 61 (1.71) | 143 (1.24) | |

| Insurance coverage | ||||

| No | 152 (1.90) | 163 (4.57) | 315 (2.73) | <.001 |

| Yes | 7758 (97.18) | 3347 (93.81) | 11 105 (96.14) | |

| Unknown | 73 (0.91) | 58 (1.63) | 131 (1.13) | |

Abbreviations: ECP, eye care practitioner; GED, General Equivalency Development.

Data are given as number (percentage) of participants unless otherwise indicated.

Other race and ethnicity included Middle Eastern or North African, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and none of these.

Other sexual orientation included bisexual; gay or lesbian; queer; poly-, omni-, sapio-, or pansexual; asexual; 2-spirit; not figured out; mostly straight; no sexuality; no labels; and something else.

Table 2 summarizes the responses from the HCAU, SDOH, and Overall Health surveys. Most measures differed significantly between those who self-reported visiting an eye care practitioner and those who did not. For example, there was a higher percentage of participants who were worried or concerned about not having a place to live who did not visit an eye care practitioner compared with those who did (13.42% vs 9.76%; difference, 3.66%; 95% CI, 2.40%-5.00%; P < .001).

Table 2. Survey Population Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Individuals, No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visited an ECP (n = 7983) | Did not visit an ECP or did not know (n = 3568) | Total (N = 11 551) | ||

| Mental health | ||||

| Poor | 208 (2.61) | 105 (2.94) | 313 (2.71) | <.001 |

| Fair | 964 (12.08) | 555 (15.55) | 1519 (13.15) | |

| Good | 2199 (27.55) | 1007 (28.22) | 3206 (27.76) | |

| Very good | 2775 (34.76) | 1163 (32.60) | 3938 (34.09) | |

| Excellent | 1772 (22.20) | 717 (20.10) | 2489 (21.55) | |

| Skipped question | 65 (0.81) | 21 (0.59) | 86 (0.74) | |

| Physical health | ||||

| Poor | 553 (6.93) | 316 (8.86) | 869 (7.52) | <.001 |

| Fair | 2391 (29.95) | 1116 (31.28) | 3507 (30.36) | |

| Good | 3196 (40.04) | 1399 (39.21) | 4595 (39.78) | |

| Very good | 1606 (20.12) | 624 (17.49) | 2230 (19.31) | |

| Excellent | 163 (2.04) | 81 (2.27) | 244 (2.11) | |

| Skipped question | 74 (0.93) | 32 (0.90) | 106 (0.92) | |

| General health | ||||

| Poor | 479 (6.00) | 262 (7.34) | 741 (6.42) | <.001 |

| Fair | 2188 (27.41) | 1065 (29.85) | 3253 (28.16) | |

| Good | 3313 (41.50) | 1437 (40.27) | 4750 (41.12) | |

| Very good | 1773 (22.21) | 688 (19.28) | 2461 (21.31) | |

| Excellent | 178 (2.23) | 90 (2.52) | 268 (2.32) | |

| Skipped question | 52 (0.65) | 26 (0.73) | 78 (0.68) | |

| Quality of life | ||||

| Poor | 165 (2.07) | 112 (3.14) | 277 (2.40) | <.001 |

| Fair | 1088 (13.63) | 570 (15.98) | 1658 (14.35) | |

| Good | 2699 (33.81) | 1278 (35.82) | 3977 (34.43) | |

| Very good | 2867 (35.91) | 1135 (31.81) | 4002 (34.65) | |

| Excellent | 1076 (13.48) | 420 (11.77) | 1496 (12.95) | |

| Skipped question | 88 (1.10) | 53 (1.49) | 141 (1.22) | |

| Food insecurity | ||||

| Never true | 6641 (83.19) | 2757 (77.27) | 9398 (81.36) | <.001 |

| Sometimes true | 1006 (12.60) | 556 (15.58) | 1562 (13.52) | |

| Often true | 274 (3.43) | 207 (5.80) | 481 (4.16) | |

| Skipped question | 62 (0.78) | 48 (1.35) | 110 (0.95) | |

| Housing insecurity | ||||

| No | 7141 (89.45) | 3055 (85.62) | 10 196 (88.27) | <.001 |

| Yes | 779 (9.76) | 479 (13.42) | 1258 (10.89) | |

| Skipped question | 63 (0.79) | 34 (0.95) | 97 (0.84) | |

| Non-English language | ||||

| No | 6961 (87.20) | 3008 (84.30) | 9969 (86.30) | <.001 |

| Yes | 945 (11.84) | 507 (14.21) | 1452 (12.57) | |

| Unknown | 77 (0.96) | 53 (1.49) | 130 (1.13) | |

| Rural living area | ||||

| No | 7506 (94.02) | 3135 (87.86) | 10 641 (92.12) | <.001 |

| Yes | 292 (3.66) | 143 (4.01) | 435 (3.77) | |

| Unknown | 185 (2.32) | 290 (8.13) | 475 (4.11) | |

| Practitioner concordance, health care delay | ||||

| None of the time | 7073 (88.60) | 2956 (82.85) | 10 029 (86.82) | <.001 |

| Some of the time | 488 (6.11) | 318 (8.91) | 806 (6.98) | |

| Most of the time | 83 (1.04) | 60 (1.68) | 143 (1.24) | |

| Always | 79 (0.99) | 53 (1.49) | 132 (1.14) | |

| Don’t know | 163 (2.04) | 103 (2.89) | 266 (2.30) | |

| Skipped question | 97 (1.22) | 78 (2.19) | 175 (1.52) | |

| Health literacy | ||||

| None of the time | 56 (0.70) | 28 (0.78) | 84 (0.73) | <.001 |

| Some of the time | 383 (4.80) | 221 (6.19) | 604 (5.23) | |

| Most of the time | 2511 (31.45) | 1047 (29.34) | 3558 (30.80) | |

| Always | 4946 (61.96) | 2184 (61.21) | 7130 (61.73) | |

| Don’t know | <20 | <20 | 22 (0.19) | |

| Skipped question | 75 (0.94) | 78 (2.19) | 153 (1.32) | |

| Practitioner concordance, health care importance | ||||

| Not important | 1955 (24.49) | 730 (20.46) | 2685 (23.24) | <.001 |

| Slightly important | 1226 (15.36) | 466 (13.06) | 1692 (14.65) | |

| Somewhat important | 2003 (25.09) | 935 (26.21) | 2938 (25.44) | |

| Very important | 2587 (32.41) | 1319 (36.97) | 3906 (33.82) | |

| Don’t know | 139 (1.74) | 56 (1.57) | 195 (1.69) | |

| Skipped question | 73 (0.91) | 62 (1.73) | 135 (1.17) | |

Abbreviation: ECP, eye care practitioner.

We examined whether demographic factors and socioeconomic status were associated with a visit to an eye care practitioner in the previous year among patients with T2D (Table 3) in both univariable and adjusted multivariable logistic regression models. For every 10-year increase in age, participants were more likely to visit an eye care practitioner (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.05; 95% CI, 1.00-1.10). Higher income and higher educational level were also independently associated with visiting an eye care practitioner. Hispanic (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.64-0.84) and non-Hispanic Black (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.65-0.81) participants were less likely to visit an eye care practitioner compared with non-Hispanic White participants only in unadjusted models. Regression results with alternate reference values for income, employment status, and insurance status are provided in eTable 3 in Supplement 1.

Table 3. Sociodemographic Characteristics Associated With Visiting an Eye Care Practitioner Among All of Us Participants With Type 2 Diabetes.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|

| Age, per every 10 y | 1.09 (1.05-1.12) | 1.05 (1.00-1.10) |

| Gender | ||

| Cisgender man | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Cisgender woman | 0.76 (0.70-0.82) | 0.86 (0.79-0.94) |

| Nonbinary or transgender | 0.79 (0.44-1.47) | 0.90 (0.49-1.70) |

| Unknown | 0.57 (0.37-0.87) | 0.68 (0.44-1.06) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 0.73 (0.64-0.84) | 0.98 (0.84-1.14) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1.49 (1.09-2.08) | 1.29 (0.94-1.80) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.72 (0.65-0.81) | 0.92 (0.81-1.03) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Otherb | 0.91 (0.68-1.23) | 0.98 (0.73-1.32) |

| Unknown | 0.91 (0.69-1.20) | 1.03 (0.78-1.38) |

| Educational level | ||

| Did not graduate high school | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| High school graduate or GED | 1.20 (0.97-1.48) | 1.05 (0.83-1.31) |

| Some college | 1.45 (1.19-1.77) | 1.18 (0.95-1.47) |

| College graduate or above | 1.97 (1.61-2.41) | 1.44 (1.14-1.80) |

| Advanced degree | 2.32 (1.89-2.85) | 1.55 (1.22-1.96) |

| Unknown | 1.61 (1.10-2.38) | 1.53 (1.03-2.31) |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Straight or heterosexual | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Otherc | 1.07 (0.93-1.23) | 1.06 (0.91-1.24) |

| Unknown | 0.86 (0.65-1.15) | 1.01 (0.76-1.36) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed for wages | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Self-employed | 0.88 (0.73-1.07) | 0.86 (0.71-1.06) |

| Out of work or unable to work | 0.78 (0.70-0.88) | 1.05 (0.92-1.19) |

| Retired | 1.01 (0.92-1.11) | 0.97 (0.86-1.10) |

| Other | 0.82 (0.66-1.02) | 1.13 (0.90-1.43) |

| Unknown | 0.54 (0.39-0.76) | 0.79 (0.55-1.14) |

| Income, $ | ||

| <25 000 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 25 000-49 999 | 1.23 (1.10-1.39) | 1.09 (0.95-1.24) |

| 50 000-74 999 | 1.44 (1.26-1.64) | 1.20 (1.03-1.39) |

| 75 000-99 999 | 1.78 (1.54-2.10) | 1.41 (1.19-1.67) |

| 100 000-149 999 | 1.20 (1.73-2.31) | 1.51 (1.27-1.79) |

| ≥150 000 | 2.15 (1.82-2.55) | 1.53 (1.26-1.87) |

| Unknown | 1.15 (1.00-1.33) | 1.08 (0.93-1.26) |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married or living with partner | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Never married | 0.84 (0.75-0.94) | 1.05 (0.92-1.19) |

| Widowed | 0.71 (0.62-0.82) | 0.83 (0.72-0.97) |

| Divorced or separated | 0.74 (0.66-0.82) | 0.93 (0.83-1.05) |

| Unknown | 0.53 (0.38-0.74) | 0.76 (0.53-1.10) |

| Insurance coverage | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 2.49 (1.99-3.11) | 1.92 (1.52-2.43) |

| Unknown | 1.35 (0.90-2.04) | 1.28 (0.84-1.97) |

Abbreviations: GED, General Equivalency Development; OR, odds ratio.

Adjusted for age, race and ethnicity, gender, educational level, sexual orientation, employment status, relationship status, and income.

Other race and ethnicity included Middle Eastern or North African, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and none of these.

Other sexual orientation included bisexual; gay or lesbian; queer; poly-, omni-, sapio-, or pansexual; asexual; 2-spirit; not figured out; mostly straight; no sexuality; no labels; and something else.

We next examined whether overall health, SDOH, and patient perceptions of health care factors were associated with having visited an eye care practitioner in the previous year (Table 4). Individuals with food insecurity or housing insecurity were less likely to visit an eye care practitioner than those who did not have these insecurities (food insecurity: AOR, 0.75 [95% CI, 0.61-0.91]; housing insecurity: AOR, 0.86 [95% CI, 0.75-0.98]). Individuals with fair mental health compared with good mental health were less likely to visit an eye care practitioner (AOR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74-0.96), and individuals who had excellent vs good general health were also less likely to visit an eye care practitioner (AOR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.56-0.96). Regression results with alternate reference values for self-reported health are provided in eTable 4 in Supplement 1. Factors related to participants’ attitudes toward practitioner concordance were associated with not having seen an eye care practitioner. Individuals who thought that it was somewhat or very important for their practitioners to understand or share their race or ethnicity, gender, religion or beliefs, or native language were less likely to have seen an eye care practitioner (somewhat important: AOR, 0.83 [95% CI, 0.74-0.93]; very important: AOR, 0.85 [95% CI, 0.76-0.95]). Individuals who reported delaying or skipping health care due to practitioner concordance some or most of the time were also less likely to visit an eye care practitioner (some of the time: AOR, 0.73 [95% CI, 0.62-0.85]; most of the time: AOR, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.50-0.99]).

Table 4. Self-Reported Health and Social Factors Associated With Visiting an Eye Care Practitioner Among All of Us Participants With Type 2 Diabetes.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|

| Mental health | ||

| Poor | 0.91 (0.71-1.16) | 1.06 (0.82-1.36) |

| Fair | 0.80 (0.70-0.90) | 0.84 (0.74-0.96) |

| Good | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Very good | 1.09 (0.99-1.21) | 0.97 (0.87-1.08) |

| Excellent | 1.13 (1.01-1.27) | 0.96 (0.85-1.08) |

| Skipped question | 1.42 (0.88-2.39) | 1.51 (0.92-2.56) |

| Physical health | ||

| Poor | 0.77 (0.66-0.89) | 0.90 (0.77-1.06) |

| Fair | 0.94 (0.85-1.03) | 1.01 (0.92-1.12) |

| Good | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Very good | 1.13 (1.01-1.26) | 1.00 (0.89-1.12) |

| Excellent | 0.88 (0.67-1.16) | 0.77 (0.58-1.02) |

| Skipped question | 1.01 (0.67-1.56) | 1.15 (0.76-1.79) |

| General health | ||

| Poor | 0.79 (0.67-0.93) | 0.95 (0.80-1.12) |

| Fair | 0.89 (0.81-0.98) | 0.98 (0.88-1.08) |

| Good | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Very good | 1.12 (1.00-1.25) | 0.99 (0.89-1.11) |

| Excellent | 0.86 (0.66-1.12) | 0.74 (0.56-0.96) |

| Skipped question | 0.87 (0.54-1.41) | 0.95 (0.59-1.57) |

| Quality of life | ||

| Poor | 0.70 (0.54-0.90) | 0.79 (0.62-1.03) |

| Fair | 0.90 (0.80-1.02) | 0.98 (0.87-1.12) |

| Good | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Very good | 1.20 (1.09-1.32) | 1.03 (0.93-1.14) |

| Excellent | 1.21 (1.06-1.38) | 0.96 (0.84-1.10) |

| Skipped question | 0.79 (0.56-1.12) | 0.82 (0.58-1.18) |

| Food insecurity | ||

| Never true | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Sometimes true | 0.75 (0.67-0.84) | 0.95 (0.84-1.07) |

| Often true | 0.55 (0.46-0.66) | 0.75 (0.61-0.91) |

| Skipped question | 0.54 (0.37-0.79) | 0.63 (0.43-0.93) |

| Housing insecurity | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 0.70 (0.62-0.79) | 0.86 (0.75-0.98) |

| Skipped question | 0.79 (0.52-1.22) | 0.99 (0.64-1.56) |

| Non-English language | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 0.81 (0.72-0.91) | 0.87 (0.75-1.01) |

| Unknown | 0.63 (0.44-0.90) | 0.75 (0.52-1.08) |

| Rural living area | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 0.85 (0.70-1.05) | 1.07 (0.87-1.33) |

| Unknown | 0.27 (0.22-0.32) | 0.28 (0.23-0.33) |

| Practitioner concordance, health care delay | ||

| None of the time | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Some of the time | 0.64 (0.55-0.74) | 0.73 (0.62-0.85) |

| Most of the time | 0.58 (0.41-0.81) | 0.70 (0.50-0.99) |

| Always | 0.62 (0.44-0.89) | 0.83 (0.58-1.19) |

| Don’t know | 0.66 (0.52-0.85) | 0.70 (0.55-0.91) |

| Skipped question | 0.52 (0.38-0.70) | 0.57 (0.42-0.78) |

| Health literacy | ||

| None of the time | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Some of the time | 0.87 (0.53-1.39) | 0.76 (0.46-1.24) |

| Most of the time | 1.20 (0.75-1.88) | 0.92 (0.57-1.46) |

| Always | 1.13 (0.71-1.77) | 0.88 (0.54-1.38) |

| Don’t know | 0.60 (0.23-1.58) | 0.69 (0.26-1.86) |

| Skipped question | 0.48 (0.27-0.83) | 0.40 (0.23-0.70) |

| Practitioner concordance, health care importance | ||

| Not important | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Slightly important | 0.98 (0.86-1.13) | 0.98 (0.85-1.12) |

| Somewhat important | 0.80 (0.71-0.90) | 0.83 (0.74-0.93) |

| Very important | 0.73 (0.66-0.82) | 0.85 (0.76-0.95) |

| Don’t know | 0.93 (0.68-1.29) | 1.01 (0.73-1.41) |

| Skipped question | 0.44 (0.31-0.62) | 0.49 (0.35-0.70) |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Adjusted for age, race and ethnicity, gender, educational level, sexual orientation, employment status, relationship status, and income.

Discussion

In this large nationwide study of patients with T2D, we investigated factors associated with receiving eye care in the previous year. Having higher educational level and income and having any insurance were associated with receiving eye care within 12 months, while having food and housing insecurity were associated with not receiving eye care. Participants who deemed practitioner concordance on race or ethnicity, gender, language, or religion or beliefs to be important or who delayed health care due to practitioner concordance were also less likely to have received eye care.

This investigation was carried out in a cohort designed to capture participants who are traditionally underprivileged or underrepresented in research, and our findings reinforce the complex and multifactorial associations of race, ethnicity, income, educational level, health insurance, and food and housing stability with adherence to DR screening. Although prior studies have shown that Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black adults have higher prevalence of DR and visual impairment caused by DR, the effects of race and ethnicity on DR screening adherence are unclear.26,27,28 Our unadjusted models showed that Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black participants were less likely to have had a diabetic eye examination, but these associations did not persist in our adjusted model. Racial and ethnic minority individuals had lower rates of DR screening in prior investigations, although this was not consistently observed in all studies.5,28,29 In a cohort of 204 073 adults with diabetes, An et al5 found that Black and male participants were less likely to adhere to DR screening after adjusting for demographic, clinical, and health care access–related variables. In another study of working-age adults with diabetes from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component from 2002 to 2009, Shi et al28 found that racial and ethnic minority populations had lower rates of eye examination each year for 8 years compared with non-Hispanic White participants after adjusting for age, gender, educational level, marital status, insurance coverage, family income, and census region. However, an analysis of 5000 adults with diabetes in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California system did not find significant differences in rates of 1-year follow-up eye examination by race or ethnicity,29 similar to our study.

Our findings regarding the association of socioeconomic factors with DR screening are consistent with prior studies.5,6,10,12,17,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 Low socioeconomic status was revealed to be associated with DR screening nonadherence,6,9,12,26,31,36 with studies showing that financial barriers or lack of health insurance were associated with not having an eye examination within 12 months for adults with diabetes.6,37 Our study found that patients with higher income or those who were insured were more likely to have had an eye examination. Furthermore, our study showed that participants with food or housing instability had lower odds of having visited an eye care practitioner in the past year, reinforcing prior studies demonstrating that financial instability, such as food instability and housing instability, and paying bills were associated with not receiving eye care.15,17 Low educational level was also shown to be associated with nonadherence to DR screening recommendations in previous studies, likely due to limited health literacy.5,6,9,12,31,35,37 We also found that participants with a college or advanced degree were more likely to have visited an eye care practitioner in the past year.

One key strength of our study was the ability to assess factors associated with health care utilization that go beyond demographics and socioeconomic status, including mental health and patient-physician concordance. We found that participants who placed high importance on practitioner concordance or who reported delaying or skipping health care due to lack of practitioner concordance were less likely to have seen an eye care practitioner. Concordance—a shared identity between patient and physician, including race, ethnicity, religion, and spoken language—is associated with a higher-quality patient experience and potentially with improved outcomes.38,39,40 This may be due to the patient’s trust in their clinician due to a point of commonality that can enhance the ways in which patients and physicians relate to one another.41 Our findings are consistent with the themes of prior studies elucidating why certain racial and ethnic minority groups face barriers to DR care. Huang et al14 found that non-Hispanic Black individuals were more prone to experience less respect, courtesy, and poorer service. Similarly, Owsley et al18 reported that transportation, trusting the physician, and communicating with the physician were perceived barriers to care for African American individuals. Hispanic individuals with diabetes are also more likely to face language barriers and struggles with health care costs.42 In previous studies,14,18,42 as well as in ours, the quality of communication with the physician was a key factor. Our results demonstrated the importance of practitioner concordance in relation to delaying eye care, suggesting the potential importance of enhancing workforce diversity and implementing cultural competency training to bridge the gap between patient-physician discordance.43,44

We also found that individuals who reported fair mental health were less likely to visit an eye care practitioner than were those who reported good mental health. These results align with findings of previous studies focusing on DR screening in persons with mental illness that reported that people with severe mental illness had reduced attendance of DR screening.45 According to a recent study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a quarter of adults experiencing vision loss reported feelings of anxiety or depression,46 which highlights the important relationship between mental health and eye care. Conversely, those who self-reported excellent general health in our study were less likely to have received eye care; possibly, patients who believe that they are in excellent health and are asymptomatic feel less need to seek out routine screening.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. Not all study participants completed the voluntary surveys related to SDOH and HCAU or answered the question on eye care utilization, which may have introduced selection bias, resulting in reduced external validity of our results. Another limitation is that the survey question on eye care utilization did not distinguish between optometrist or ophthalmologist visits, nor did it ask whether dilation occurred at the visit, although presumably most eye care practitioners would perform a diabetic eye screening examination for patients with diabetes. Thus, results may not be perfectly comparable to those of other studies using different or more specific survey questions. Additionally, teleophthalmology screening or artificial intelligence screening is not covered in the survey, so it is possible that some patients were screened by retinal photograph but responded no on the eye visit question. Although these modalities of screening are not yet common or widespread in the US, this may have resulted in lower reported rates of eye examination than actually occurred.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated that food or housing insecurity, attitudes toward practitioner concordance, income, educational level, and insurance status were associated with a lower likelihood of receiving DR screening. Our results highlight self-reported barriers to seeking care and the potential importance of taking steps to promote health equity, such as providing a safe space to receive care, reducing implicit bias, and improving access to care.

eTable 1. Codes to Identify Individuals in All of Us

eTable 2. Survey Questions From The Basics, Overall Health, Healthcare Access and Utilization, and Social Determinants of Health

eTable 3. Sociodemographic Predictors for Visiting an Eye Care Provider Among All of Us Participants With Type 2 Diabetes Using Different Reference Levels

eTable 4. Self-Reported Health and Social Predictors for Visiting an Eye Care Provider Among All of Us Participants With Type 2 Diabetes Using Different Reference Levels

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Zhang X, Saaddine JB, Chou CF, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the United States, 2005-2008. JAMA. 2010;304(6):649-656. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL III, Klein RE, et al. ; Global Diabetic Retinopathy Project Group . Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(9):1677-1682. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00475-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NCQA. HEDIS measures and technical resources. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/

- 4.Flaxel CJ, Adelman RA, Bailey ST, et al. Diabetic retinopathy preferred practice pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(1):P66-P145. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An J, Niu F, Turpcu A, Rajput Y, Cheetham TC. Adherence to the American Diabetes Association retinal screening guidelines for population with diabetes in the United States. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2018;25(3):257-265. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2018.1424344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eppley SE, Mansberger SL, Ramanathan S, Lowry EA. Characteristics associated with adherence to annual dilated eye examinations among US patients with diagnosed diabetes. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(11):1492-1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yusuf R, Chen EM, Nwanyanwu K, Richards B. Neighborhood deprivation and adherence to initial diabetic retinopathy screening. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4(5):550-552. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2020.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murchison AP, Hark L, Pizzi LT, et al. Non-adherence to eye care in people with diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000333. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paksin-Hall A, Dent ML, Dong F, Ablah E. Factors contributing to diabetes patients not receiving annual dilated eye examinations. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2013;20(5):281-287. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2013.789531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai CX, Li Y, Zeger SL, McCarthy ML. Social determinants of health impacting adherence to diabetic retinopathy examinations. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2021;9(1):e002374. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2021-002374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nsiah-Kumi P, Ortmeier SR, Brown AE. Disparities in diabetic retinopathy screening and disease for racial and ethnic minority populations—a literature review. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(5):430-437. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30929-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas CG, Channa R, Prichett L, Liu TYA, Abramoff MD, Wolf RM. Racial/ethnic disparities and barriers to diabetic retinopathy screening in youths. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(7):791-795. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2021.1551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel D, Ananthakrishnan A, Lin T, Channa R, Liu TYA, Wolf RM. Social determinants of health and impact on screening, prevalence, and management of diabetic retinopathy in adults: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2022;11(23):7120. doi: 10.3390/jcm11237120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang BB, Radha Saseendrakumar B, Delavar A, Baxter SL. Racial disparities in barriers to care for patients with diabetic retinopathy in a nationwide cohort. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2023;12(3):14. doi: 10.1167/tvst.12.3.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hom GL, Cwalina TB, Jella TK, Singh RP. Assessing financial insecurity among common eye conditions: a 2016-2017 national health survey study. Eye (Lond). 2022;36(10):2044-2051. doi: 10.1038/s41433-021-01745-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broman AT, Hafiz G, Muñoz B, et al. Cataract and barriers to cataract surgery in a US Hispanic population: Proyecto VER. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(9):1231-1236. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.9.1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Zupan NJ, Shiyanbola OO, et al. Factors influencing patient adherence with diabetic eye screening in rural communities: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0206742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owsley C, McGwin G, Scilley K, Girkin CA, Phillips JM, Searcey K. Perceived barriers to care and attitudes about vision and eye care: focus groups with older African Americans and eye care providers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(7):2797-2802. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denny JC, Rutter JL, Goldstein DB, et al. ; All of Us Research Program Investigators . The “All of Us” research program. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(7):668-676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1809937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mapes BM, Foster CS, Kusnoor SV, et al. ; All of Us Research Program . Diversity and inclusion for the All of Us research program: a scoping review. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0234962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030: social determinants of health. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

- 24.Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics. Data standardization. Accessed July 18, 2023. https://www.ohdsi.org/data-standardization/

- 25.Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, et al. Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: a review. Lancet. 2016;388(10042):412-436. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00684-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muñoz B, West SK, Rubin GS, et al. Causes of blindness and visual impairment in a population of older Americans: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(6):819-825. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.6.819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris MI, Klein R, Cowie CC, Rowland M, Byrd-Holt DD. Is the risk of diabetic retinopathy greater in non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans than in non-Hispanic whites with type 2 diabetes? a U.S. population study. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(8):1230-1235. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.8.1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi Q, Zhao Y, Fonseca V, Krousel-Wood M, Shi L. Racial disparity of eye examinations among the U.S. working-age population with diabetes: 2002-2009. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(5):1321-1328. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saadine JB, Fong DS, Yao J. Factors associated with follow-up eye examinations among persons with diabetes. Retina. 2008;28(2):195-200. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318115169a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang SY, Andrews CA, Gardner TW, Wood M, Singer K, Stein JD. Ophthalmic screening patterns among youths with diabetes enrolled in a large US managed care network. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(5):432-438. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.0089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tran EMT, Bhattacharya J, Pershing S. Self-reported receipt of dilated fundus examinations among patients with diabetes: Medicare Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002-2013. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;179:18-24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Will JC, German RR, Schuman E, Michael S, Kurth DM, Deeb L. Patient adherence to guidelines for diabetes eye care: results from the diabetic eye disease follow-up study. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(10):1669-1671. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.84.10.1669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peavey JJ, D’Amico SL, Kim BY, Higgins ST, Friedman DS, Brady CJ. Impact of socioeconomic disadvantage and diabetic retinopathy severity on poor ophthalmic follow-up in a rural Vermont and New York population. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:2397-2403. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S258270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taccheri C, Jordan J, Tran D, et al. The impact of social determinants of health on eye care utilization in a national sample of people with diabetes. Ophthalmology. 2023;130(10):1037-1045. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jotte A, Vander Kooi W, French DD. Factors associated with annual vision screening in diabetic adults: analysis of the 2019 National Health Interview Survey. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023;17:613-621. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S402082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chou CF, Sherrod CE, Zhang X, et al. Barriers to eye care among people aged 40 years and older with diagnosed diabetes, 2006-2010. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(1):180-188. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fisher MD, Rajput Y, Gu T, et al. Evaluating adherence to dilated eye examination recommendations among patients with diabetes, combined with patient and provider perspectives. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9(7):385-393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, et al. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):117-140. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takeshita J, Wang S, Loren AW, et al. Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024583. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diamond L, Izquierdo K, Canfield D, Matsoukas K, Gany F. A systematic review of the impact of patient-physician non-English language concordance on quality of care and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1591-1606. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04847-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, Haidet P. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(3):198-205. doi: 10.1370/afm.821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hudson SM, Modjtahedi BS, Altman D, Jimenez JJ, Luong TQ, Fong DS. Factors affecting compliance with diabetic retinopathy screening: a qualitative study comparing English and Spanish speakers. Clin Ophthalmol. 2022;16:1009-1018. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S342965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LaVeist TA, Pierre G. Integrating the 3Ds–social determinants, health disparities, and health-care workforce diversity. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(suppl 2):9-14. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schoenthaler A, Ravenell J. Understanding the patient experience through the lenses of racial/ethnic and gender patient-physician concordance. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2025349. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bradley ER, Delaffon V. Diabetic retinopathy screening in persons with mental illness: a literature review. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2020;5(1):e000437. doi: 10.1136/bmjophth-2020-000437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lundeen EA, Saydah S, Ehrlich JR, Saaddine J. Self-reported vision impairment and psychological distress in U.S. adults. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2022;29(2):171-181. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2021.1918177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Codes to Identify Individuals in All of Us

eTable 2. Survey Questions From The Basics, Overall Health, Healthcare Access and Utilization, and Social Determinants of Health

eTable 3. Sociodemographic Predictors for Visiting an Eye Care Provider Among All of Us Participants With Type 2 Diabetes Using Different Reference Levels

eTable 4. Self-Reported Health and Social Predictors for Visiting an Eye Care Provider Among All of Us Participants With Type 2 Diabetes Using Different Reference Levels

Data Sharing Statement