This nonrandomized controlled trial assesses the safety and clinical activity of anti–PD-1 therapy to treat high-risk proliferative verrucous leukoplakia.

Key Points

Question

Can immune checkpoint therapy treat high-risk oral precancerous disease to prevent progression to oral squamous carcinoma?

Findings

This phase 2 nonrandomized controlled trial treated 33 patients with high-risk oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia with the programmed cell death 1 protein inhibitor nivolumab and demonstrated variable lesion regression by size and degree of dysplasia in response to therapy, while 27% of patients developed invasive oral cancer after nivolumab. All whole-exome sequenced patients who progressed to develop cancer had 9p21.3 chromosomal loss.

Meaning

Nivolumab showed potential clinical activity in this immune checkpoint therapy trial for high-risk oral precancerous disease; future trials should prioritize cancer-free survival end points and biomarker stratification.

Abstract

Importance

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) is an aggressive oral precancerous disease characterized by a high risk of transformation to invasive oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), and no therapies have been shown to affect its natural history. A recent study of the PVL immune landscape revealed a cytotoxic T-cell–rich microenvironment, providing strong rationale to investigate immune checkpoint therapy.

Objective

To determine the safety and clinical activity of anti–programmed cell death 1 protein (PD-1) therapy to treat high-risk PVL.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This nonrandomized, open-label, phase 2 clinical trial was conducted from January 2019 to December 2021 at a single academic medical center; median (range) follow-up was 21.1 (5.4-43.6) months. Participants were a population-based sample of patients with PVL (multifocal, contiguous, or a single lesion ≥4 cm with any degree of dysplasia).

Intervention

Patients underwent pretreatment biopsy (1-3 sites) and then received 4 doses of nivolumab (480 mg intravenously) every 28 days, followed by rebiopsy and intraoral photographs at each visit.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was the change in composite score (size and degree of dysplasia) from before to after treatment (major response [MR]: >80% decrease in score; partial response: 40%-80% decrease). Secondary analyses included immune-related adverse events, cancer-free survival (CFS), PD-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, 9p21.3 deletion, and other exploratory immunologic and genomic associations of response.

Results

A total of 33 patients were enrolled (median [range] age, 63 [32-80] years; 18 [55%] were female), including 8 (24%) with previously resected early-stage OSCC. Twelve patients (36%) (95% CI, 20.4%-54.8%) had a response by composite score (3 MRs [9%]), 4 had progressive disease (>10% composite score increase, or cancer). Nine patients (27%) developed OSCC during the trial, with a 2-year CFS of 73% (95% CI, 53%-86%). Two patients (6%) discontinued because of toxic effects; 7 (21%) experienced grade 3 to 4 immune-related adverse events. PD-L1 combined positive scores were not associated with response or CFS. Of 20 whole-exome sequenced patients, all 6 patients who had progression to OSCC after nivolumab treatment exhibited 9p21.3 somatic copy-number loss on pretreatment biopsy, while only 4 of the 14 patients (29%) who did not develop OSCC had 9p21.3 loss.

Conclusions and Relevance

This immune checkpoint therapy precancer nonrandomized clinical trial met its prespecified response end point, suggesting potential clinical activity for nivolumab in high-risk PVL. Findings identified immunogenomic associations to inform future trials in this precancerous disease with unmet medical need that has been difficult to study.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03692325

Introduction

Oral leukoplakia refers to a white plaque of variable cancer risk, having excluded other conditions, and affects up to 5% of the global population,1 but only a small proportion of leukoplakia lesions will undergo malignant transformation.2 Degree of epithelial dysplasia, lesion size, and tobacco history all influence the transformation rate.3 Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) defines an aggressive subtype with a malignant transformation rate exceeding 10% per year, characterized by heterogeneous or verrucous lesions involving multiple oral subsites.4,5,6 To date, no therapies have been shown to change the natural history of this severe oral precancerous disease,7,8,9 reflecting a critical unmet medical need.

Studies of the immune landscape led to pivotal trials of anti–programmed cell death 1 protein (PD-1) therapy in recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.10,11,12,13 Our prior retrospective study revealed a cytotoxic T-cell–rich immune microenvironment in PVL.14 These findings together with immunosurveillance studies in the context of lung premalignancy and of various immune-oncology interventions in preclinical models15,16,17,18 provided strong rationale for investigating PD-1/PD-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) axis blockade in oral precancerous disease. Here we report the first (to our knowledge) trial to evaluate the safety and clinical activity of preventive anti–PD-1 therapy among patients with high-risk PVL.

Methods

Study Population

This was an open-label, single-group phase 2 trial conducted at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts (trial protocol in Supplement 1). Patients with high-risk oral leukoplakia defined by any of the following criteria were eligible: PVL with multifocal (≥2), contiguous 3 cm or greater, or a single lesion 4 cm or greater in largest diameter (2-3-4 rule) with epithelial dysplasia (any degree); PVL with 4-quadrant oral cavity involvement; at least 1 localized leukoplakia with moderate dysplasia, or erythroleukoplakia for which surgery was indicated but not feasible or the patient refused. Patients were 18 years or older and had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 2 or lower. A history of surgically treated carcinoma in situ (CIS) or early-stage oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual, eighth edition, stages I or II) was permitted. Participants defined their race and ethnicity by self-identification. This was assessed given the potential for variation in interpreting the results of the study based on a majority of participants from 1 ethnic group and/or race given the epidemiology of the disease and the treatment center’s regional participant demographics. The trial was approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center institutional review board (18-387), conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, and registered nationally (NCT03692325). This study followed the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations With Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) reporting guideline.

Treatment

Following written informed consent, participants received nivolumab (480 mg intravenously) on day 1 of a 28-day cycle for 4 cycles. Immunosuppressive medications and doses of corticosteroids greater than 20-mg prednisone equivalent daily were prohibited unless used for immune-related toxicity management.

Assessments

Three weeks prior to the first dose of nivolumab and at monthly visits, patients underwent digital intraoral color photography to capture all leukoplakia lesions. Bidimensional measurements were obtained from up to 3 target lesions (per patient) as determined by 1 of 5 oral medicine investigators. Screening and posttreatment biopsies were performed by the same oral medicine investigator for consistency. Fresh tissue biopsies from all target lesions were mandatory at baseline and 30 days after the final dose of nivolumab. Pathologic specimens from each biopsy were examined by 2 experienced oral pathologists (V.Y.J. and K.S.W.) blinded to outcome data (or a third in cases of any scoring discrepancy). New or suspicious nontarget lesions or changes in target lesions could trigger rebiopsy at any point.

Response was assessed according to a modified composite scoring system (van der Waal classification)19 (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). The sum of target lesion point scores (both clinical and pathologic) yielded a composite score. The percent change in composite score before and after treatment determined best overall response. Major response (MR) was a decrease of more than 80%, partial response (PR) a decrease of 40% to 80%, stable disease (SD) was neither an MR or PR, and progression of disease (PD) was defined as an increase of 10% or greater in the composite score or a CIS or OSCC diagnosis. Patients were followed up with clinical examinations every 3 to 4 months until study withdrawal or up to 5 years.

Safety

Safety evaluations included laboratory and adverse event (AE) assessments (National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0).20 For patients who developed grade 3 or intolerable grade 2 immune-related AEs (irAEs), nivolumab treatment could be interrupted, delayed, or discontinued; certain grade 4 irAEs required discontinuation. AEs were captured up to 3 months after completion of nivolumab treatment.

Statistical Analysis

The primary end point was best overall response (MR + PR rate) as defined by the percent change in clinical-pathologic composite score. A 2-stage Simon optimal design was used. When more than 5 of 33 patients who were eligible and began protocol treatment had disease in response (assuming >1 patient with disease in response among the first 16 patients), there was 84.3% power to rule out a 10% and detect a 25% response rate (using a 1-sided exact binomial test, type I error rate of 10%). A response rate of 25% was targeted when considering the cumulative risk of serious irAEs.21

Secondary end points included safety and cancer-free survival (CFS), defined as the time from trial registration to OSCC or death due to any cause (participants alive without oral cancer were censored at last assessment). Based on studies of PD-L1 expression14,22 and somatic 9p21 copy-number loss in advanced OSCC, lung, and other tumors,23,24 we conducted secondary analyses to evaluate the association of pretreatment dysplastic tissue PD-L1 expression and 9p21.3 deletion status with outcomes. Exploratory analyses included immunogenomic profiling using multiparametric flow cytometry and whole-exome sequencing (WES) detailed in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

The primary clinical activity population included all eligible patients who began protocol treatment. Response rate was summarized as a proportion with a corresponding 2-stage 95% CI. The distribution of CFS was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Logistic regression and Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) for best overall response and hazard ratios (HRs) for CFS, respectively. Fisher exact test was used to compare somatic copy-number alterations (SCNAs) and genomic subsets (2-sided). Wilcoxon signed rank test (paired data) and Wilcoxon rank-sum test (independent) were used to analyze both circulating and tissue-based immune profiling parameters (2-sided), using a Bonferroni-Dunn correction for tests of multiple comparisons. Data as of September 30, 2022, were analyzed. Data analysis used R, version 4.3.0 for Windows (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). A 2-sided P ≤ .05 indicates statistical significance.

Results

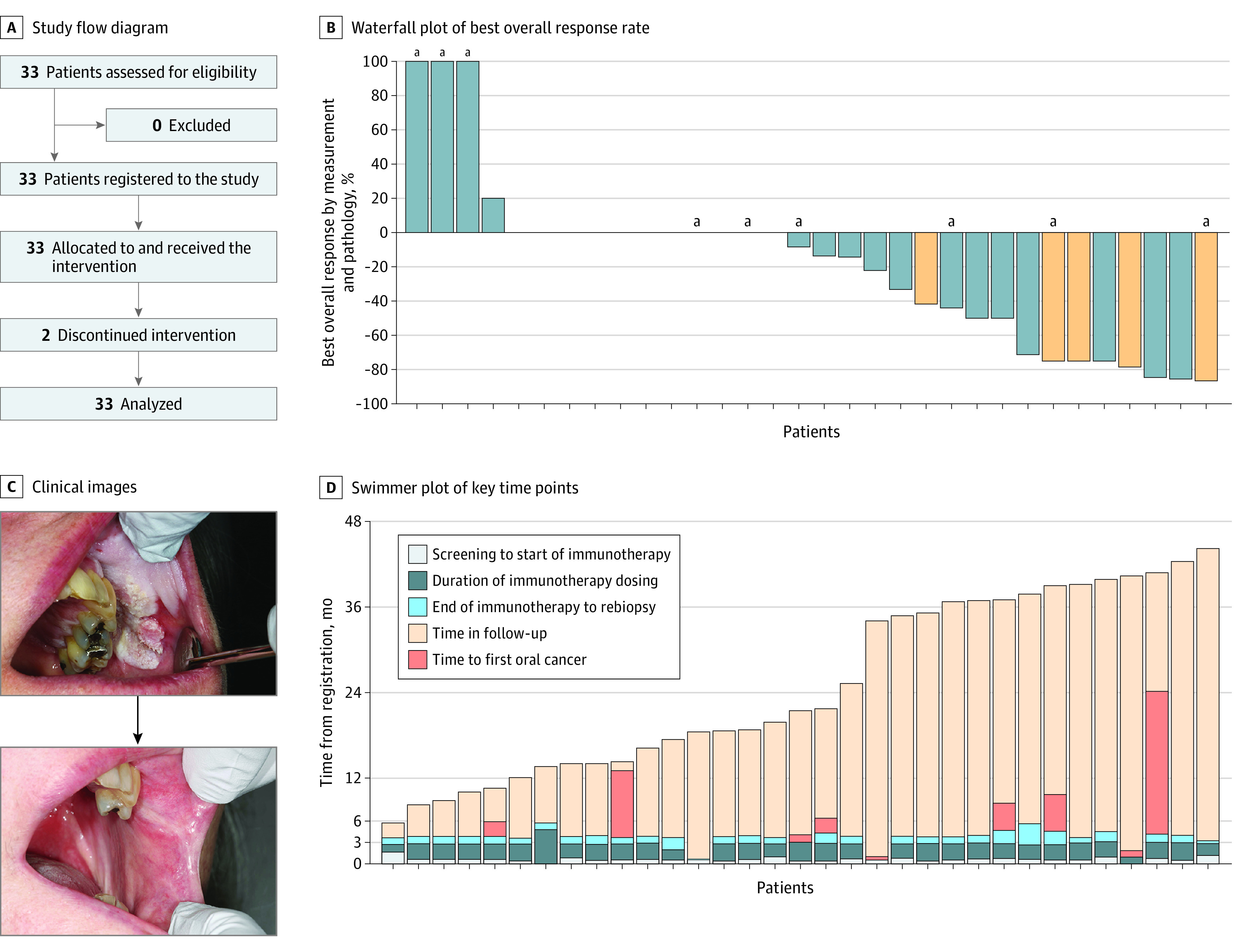

Between January 10, 2019, and December 13, 2021, the trial enrolled 33 patients. All began protocol treatment and were included in analyses (Figure 1A). Median (range) age was 63 (32-80) years, with a slight majority of female individuals (18 [55%]), and many were smokers (16 [48%]) (Table 1). Eight (24%) had a history of surgically treated early-stage OSCC. Median (range) disease-free interval for those with a head and neck cancer prior to trial entry was 10.5 (0.3-195.0) months. A median of 4 cycles of therapy were received (12% of patients received fewer than all 4 doses).

Figure 1. Clinical and Pathologic Response.

A, Study flow diagram. B, Waterfall plot showing best overall response rate to up to 4 doses of immunotherapy (nivolumab) in patients with high-risk oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. Response was determined by the relative change in composite score determined pre- to posttherapy using bidimensional lesion measurements and biopsy degree of dysplasia (mild, moderate, severe). A decrease by greater than 80% equated to a major response, a decrease by 40% to 80% was a partial response, and an increase by 10% or more or new carcinoma in situ or oral squamous cell carcinoma development was deemed progressive disease. Orange bars indicate patients with pretreatment epithelial dysplasia tissue demonstrating a programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 combined positive score of 20 or greater. C, Photographs of a responder (top, pretreatment; bottom, posttreatment) showing a 4 × 3 cm verrucous lesion contiguous with a left maxillary gingival sulcus lesion defined by proliferative and hyperkeratotic change with inferior erythematous friability at a heaped-up border, which resolved postimmunotherapy. Of note, teeth No. 25 to 27 were extracted prior to the posttreatment photo being taken. D, Swimmer plot showing key time points throughout the trial duration and follow-up period. Each bar represents an individual participant. All patients were alive at last follow-up.

aDeveloped oral cancer.

Table 1. Baseline Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) (N = 33) |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 63.2 (32-80) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 18 (55) |

| Male | 15 (45) |

| Race and ethnicitya | |

| Asian | 1 (3) |

| Hispanic | 0 |

| Non-Hispanic | 33 (100) |

| White | 31 (94) |

| Other | 1 (3) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 30 (91) |

| 1 | 3 (9) |

| Autoimmune history | |

| Yes | 3 (9) |

| No | 30 (91) |

| Smoking history | |

| Never or ≤10 pack-years | 17 (52) |

| Former (>10 pack-years) | 15 (45) |

| Current | 1 (3) |

| Primary site of diseaseb | |

| Oral tongue | 13 (39) |

| Buccal gingiva | 10 (30) |

| Palatal gingiva | 1 (3) |

| Alveolar ridge mucosa | 9 (27) |

| No. of target lesions | |

| 1 | 23 (70) |

| 2 | 7 (21) |

| 3 | 3 (9) |

| High-risk oral leukoplakia subtype | |

| PVL | 29 (88) |

| PVL with 4-quadrant involvement | 2 (6) |

| Localized leukoplakia with moderate dysplasia | 1 (3) |

| Erythroleukoplakia | 1 (3) |

| Worst degree of dysplasia identified on biopsy at baseline | |

| None | 0 |

| Mild | 24 (73) |

| Moderate | 8 (24) |

| Severe or carcinoma in situ | 1 (3) |

| Prior early-stage oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma diagnosis | |

| Yes | 8 (24) |

| No | 25 (76) |

| Doses of nivolumab received (1-4), median (range) | 4 (1-4) |

| Time from first dose of immunotherapy to posttreatment biopsy, median (range), d | 115 (29-171) |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PVL, proliferative verrucous leukoplakia.

As classified by the participant (other denotes multiple races).

Denotes the largest or primary site of oral leukoplakia at trial enrollment, as many patients had multifocal sites of involvement in the oral cavity.

Twelve patients (36%) (95% CI, 20.4%-54.8%) demonstrated a best overall response of MR or PR, with 3 (9%) demonstrating a greater than 80% reduction in composite score (Table 2). Among individual patients, 2 (6%) had complete resolution of at least 1 target lesion. Sixteen (48%) had SD, and 4 patients (12%) had a best response of PD (Figure 1B and D). Three of the patients with a best response of PD developed OSCC in a target lesion identified on their end-of-treatment biopsy, and the other experienced an increase in the severity of dysplasia in a buccal gingiva target lesion resulting in greater than 20% composite score increase. No patient developed CIS. Six additional patients with a best response other than PD later developed OSCC (eTable 1 in Supplement 2); of note, 6 of the 9 who developed OSCC had a history of early-stage OSCC, and 3 of 12 responders (25%) later developed OSCC. Among the 9 patients with an OSCC event, median (range) time from trial registration to a first OSCC event was 6.6 (1.3-24.3) months, and median time from the last dose of nivolumab to the development of OSCC was 3.7 months. Eight of 9 events were in target lesions.

Table 2. Outcome Measures and Reasons for Treatment Discontinuation.

| Outcome measure | Patients, No. (%) (N = 33) |

|---|---|

| Best overall response to immunotherapya | |

| Major response | 3 (9) |

| Partial response | 9 (27) |

| Stable disease | 16 (48) |

| Progression of diseaseb | 4 (12) |

| Unevaluablec | 1 (3) |

| Reason for treatment discontinuation | |

| Completed therapy | 29 (88) |

| Toxic effect from drug | 2 (6) |

| Progression of disease | 2 (6) |

| Physician discretion | 0 |

| Withdrawal of consent | 0 |

| Death | 0 |

| Follow-up, median (range), mo | 21.1 (5.4-43.6+) |

| CFS, median (95% CI), mo | NR (24.3-NR) |

| No. of eventsd | 9 (27) |

| 1-y CFS, % (95% CI) | 76.6 (56.8-88.2) |

| 2-y CFS, % (95% CI) | 72.8 (52.6-85.5) |

| 3-y CFS, % (95% CI) | 66.2 (43.3-81.5) |

| OS, median (95% CI), mo | NR |

| No. of events | 0 |

| 2-y OS, % | 100 |

Abbreviations: CFS, cancer-free survival; NR, not reached; OS, overall survival; +, censored at last follow-up as of data cutoff.

Determined by the change in bidirectional measurements and degree of pathologic dysplasia composite scoring of target leukoplakia lesion(s).

Determined via composite score (at least a 10% increase in the total composite score from baseline) or development of either oral squamous cell carcinoma or carcinoma in situ while receiving study treatment.

One patient experienced toxic effects and withdrew consent from treatment prior to rebiopsy.

CFS events include development of oral squamous cell carcinoma documented via biopsy confirmation or death, whichever occurred first. None of the 9 events were due to death alone.

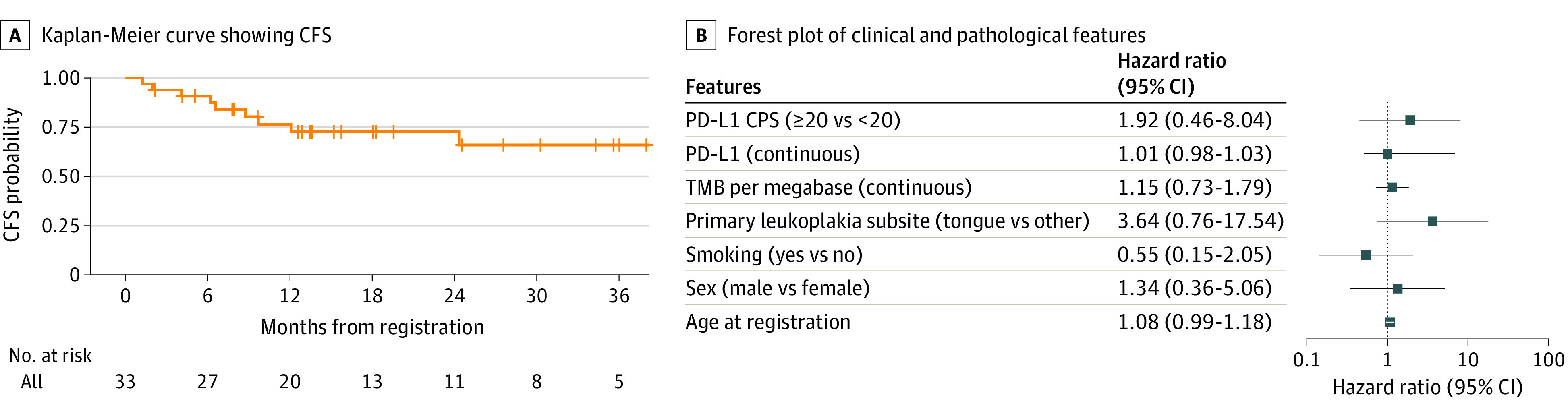

At a median (range) follow-up of 21.1 (5.4-43.6) months, median CFS had not been reached (NR) (95% CI, 24.3 months to NR) with a 2-year CFS of 72.8% (95% CI, 52.6%-85.5%) (Figure 2). There were 9 CFS events (27.3%) and no deaths (all OSCC events). No clinical or pathologic features appeared to be associated with CFS except a history of early-stage OSCC (HR, 13.53; 95% CI, 3.3-55.5) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). The median CFS for patients with a prior oral cavity cancer diagnosis was 1.3 months (95% CI, 6.2-12.1), and for patients without a history of OSCC, the median was not reached.

Figure 2. Survival Outcomes.

A, Kaplan-Meier curve showing cancer-free survival (CFS) reported in months from the time of trial registration to the first of oral squamous cell carcinoma, death, or censored at last follow-up. B, Forest plot showing the hazard ratio and 95% CIs (log 10) of the association of clinical and pathologic variables with CFS (hazard ratio >1 indicates higher risk of CFS event). Univariate Cox proportional hazard model. CPS indicates combined positive score; PD-L1, programmed cell death 1 ligand 1; TMB, tumor mutational burden.

Fatigue was the most common AE (18 [55%]), followed by oral pain (11 [33%]) and diarrhea (9 [27%]) (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Seven patients (21%) developed grade 3 to 4 AEs, which later resolved. One patient without a cardiac history had atypical chest pain after a half-marathon after cycle 1 and had an elevated troponin T level; cardiologic evaluation clarified a low suspicion for immune-related myocarditis, and the patient resumed treatment. Two patients developed immune-related hepatitis. One patient developed immune-related colitis 5 months after completion of therapy.

All pretreatment dysplastic specimens were evaluable for PD-L1 combined positive score (CPS) testing. Scores ranged from 0 to 80 (eFigure 2A and B in Supplement 2), with 22 (67%) demonstrating a CPS of 1 or greater. No significant difference was observed in PD-L1 CPS scores among responders vs nonresponders (12.5 vs 5, P = .21), and patients with CPS 20 or greater vs less than 20 were not significantly more likely to respond (OR, 4.29; 95% CI, 0.83-25.94) (eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Multiparametric flow on paired dysplastic tissue before and after treatment revealed that CD8+ T cells showed greater activation (CD69) and immune checkpoint LAG3 coexpression after treatment, with increased LAG3 expression among patients with pretreatment 9p21.3 loss of heterozygosity profiles. Among paired peripheral blood samples, PD-1 expression on both circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells decreased significantly (both adjusted P < .001), while CD38 increased on CD8+ T cells (adjusted P < .001) (supporting data in eFigure 2C in Supplement 2).

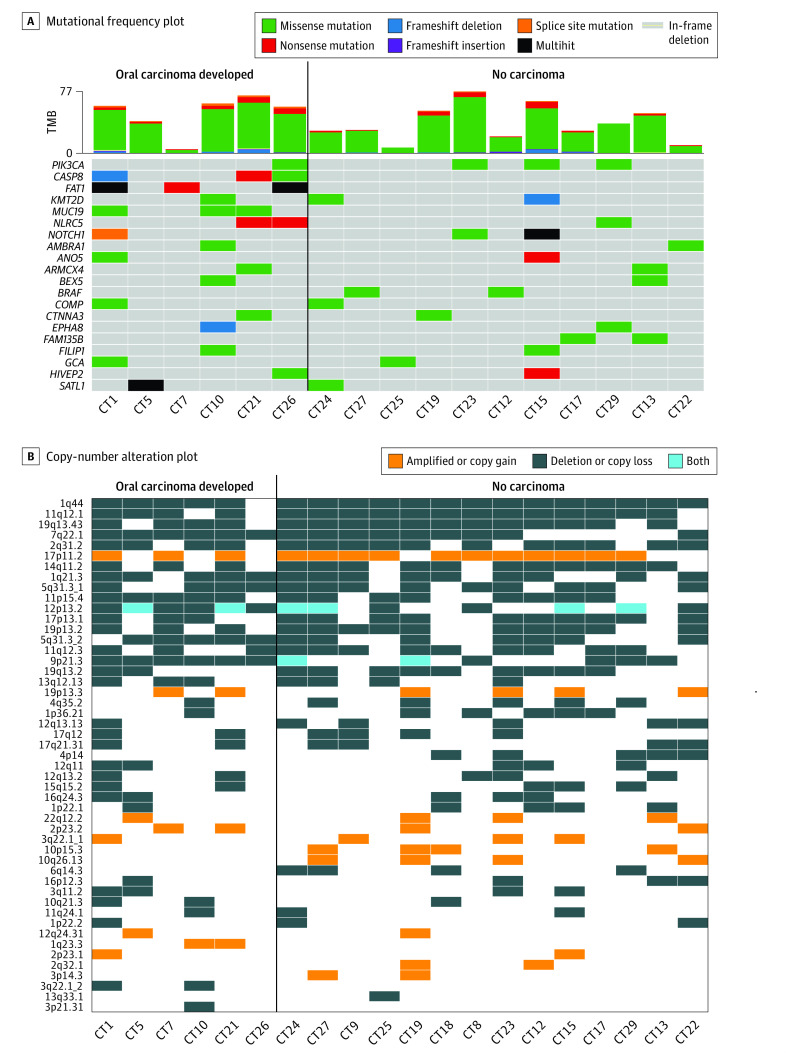

A subset of 23 patients (70%) had adequate tissue for WES. Twenty pairs of paired peripheral blood and oral dysplastic tissue passed quality controls. Pretreatment median (range) tumor mutational burden was 3.4 (1.4-8.0) mutations per megabase and was similar regardless of response (3.6 vs 2.8, P = .63) and among patients who developed cancer vs not (3.9 vs 2.9, P = .51) (Figure 3A). Genomic driver alterations were similar in patients who developed OSCC vs not. Missense mutations in PIK3CA were common. SCNAs revealed a range of complex allelic-imbalance profiles, primarily focal deletions, most frequently observed at 1q44 (Figure 3B). Only 9p21.3 deletion yielded statistically significant differences between patients who developed OSCC and those who did not. Of 10 patients whose pretreatment tissue sequencing showed 9p21.3 copy-number loss, 6 (60%) later developed OSCC, whereas none of the 10 patients without 9p21.3 loss developed OSCC (P = .01).

Figure 3. Genomic Associations of Response and Survival.

A, Mutational frequency plot with each column representing an individual dysplastic sample (sample IDs noted, CT#). Genes are arranged top to bottom by mutational frequency. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) for dysplastic samples is plotted in the bar graph above the mutational plot. Only the top 20 most frequently altered genes are displayed. B, Copy-number alteration plot demonstrating allelic imbalance (amplifications, deletions, or both [polyploidy]) among pretreatment oral dysplastic epithelial samples prior to treatment with 4 doses of nivolumab arranged by those patients who developed oral carcinoma (left) vs not (at last known follow-up).

Discussion

We present the first (to our knowledge) trial demonstrating the potential efficacy of PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade among patients with high-risk oral precancerous disease. Our data suggest that PD-1 inhibition may yield clinical-pathologic regression in some patients. While some chemoprevention trials have yielded short-term responses to reverse or mute oral carcinogenesis, no therapeutic agents have demonstrated an improvement in CFS, and rates of progression to cancer range from 10% to 30%.7,8,9,25,26,27,28

PVL is an uncommon variant of leukoplakia, occurring in less than 1% of adults, which is aggressive and challenging to treat29,30 largely due to nonhomogeneous, multifocal lesions, and with the histologic hallmarks being corrugated hyperkeratosis and verrucous hyperplasia with variable dysplasia.5,31,32 Some degree of dysplasia was required in our trial with the aim of selecting the highest-risk lesions. Our previous retrospective cohort of patients with PVL suggested a 2-year CFS of 82%.14 In the present trial, we observed a 2-year CFS of 73%; however, we designed the trial with stringent entry criteria, requiring biopsy-proven dysplasia and permitting a history of OSCC. Notably, CFS was a secondary end point in our trial, and the sample size and median follow-up time were limited. It is plausible that our preliminary CFS rate would have been similar without immunotherapy exposure, supporting the need for randomized data. Three patients who had a response during the trial later developed OSCC, suggesting that our scoring system and response definitions may not adequately predict CFS. The prognostic impact of tumor size may not be readily generalizable to precancerous lesions, and a 1-tier change in histopathology (degree of dysplasia) may not be an optimal outcome measurement. As compared to prior chemoprevention trials, our rate of progression to cancer (27%) was comparable,7,8,9,25,26,27,28 while response was defined in prior studies primarily based on lesion size and not histologic change.

Of 9 OSCC events, 6 (67%) were among patients with prior early-stage OSCC with a short median time to failure (<4 months). Including patients with prior cancer events added some heterogeneity to the trial population, but we thought it was important to include them given their recurrence risk.33 Exclusion of patients with prior oral cancer has been implemented in some chemoprevention studies,27,28,34,35 but in the Erlotinib Prevention of Oral Cancer (EPOC) trial,7 60% of patients had prior OSCC. That study followed a prevention-adjuvant therapy convergent design36 under the assumption that high-risk patients with oral premalignant lesions and resected cancers share molecular alterations for prevention and could be studied in similar settings.23,37,38 The cancer events among the patients in the current trial were most often pT1 lesions, but structured follow-up may have identified cancers earlier with a bias toward earlier biopsy. Longer follow-up in a larger randomized trial design will be needed to identify a time-to-event or survival benefit. It is unclear whether immunotherapy favorably affects the pathologic severity of future oral cancer events.

We acknowledge that novel pathologic criteria were required to evaluate clinical activity in this first oral precancer immune checkpoint therapy (ICT) prevention trial, as more traditional response criteria would not apply. We chose a modified composite scoring method to quantify response as a function of lesion size and dysplasia across multiple sites, recognizing that analyzing percent changes in composite score can be limited by small sample size and variability in scores. To limit interobserver variability, we required digital intraoral photography with bidimensional measurements and structured pathologic examination among 2 to 3 oral pathologists. We recognize that distinguishing mild dysplasia from hyperkeratosis can be subject to interpretation, and most of the cohort (73%) had mild dysplasia at baseline. Further, we observed a mix of lesion size and/or histologic changes in response to therapy among individual patients. We appreciate that multifocal lesions may have affected response assessments, but we would not expect spontaneous clinical regression in PVL in the absence of an effective therapy. A time-to-event CFS end point may be more generalizable and have broader clinical applicability. It is also worth noting that the trial population had limited racial and ethnic diversity, and many patients traveled to our center for treatment, which introduced some component of socioeconomic bias. This not only has potential treatment outcome implications, but also may influence tolerance and affordability.

A major concern for this ICT trial was safety, as we treated patients who did not have documented oral cancer. Frequently reported AEs were in line with prior head and neck cancer study populations more broadly.10,11,12,13 We observed some increase in grade 3 to 4 AEs (21.2%), although we permitted a history of autoimmune disease, and all higher-grade irAEs resolved in time with no deaths. These findings need to be weighed carefully against the potential for clinical activity, given concern for a narrow therapeutic risk-benefit ratio.

Patients with PD-L1 CPS scores of 20 or greater in PVL were not more likely to respond (as has been observed in advanced OSCC11), but this could be due to sample size limitations and/or scoring criteria (CPS is validated on invasive cancers); future studies will need to explore this further. Circulating CD4+/CD8+ T cells displayed significantly increased CD38 and reduced PD-1 expression following treatment, confirming on-target blockade of PD-1 and T-cell activation. An immune phenotype indicative of activation and/or reinvigoration was also observed on CD8+ T cells in oral dysplastic lesions, where surface expression of CD69 and LAG-3 were elevated in posttreatment samples.

Genomic studies of precancers have been limited by adequate tissue availability from small biopsies. Therefore, prior studies generally assessed single genes and/or allelic-imbalance using microsatellite markers, detecting 9p21.3 loss of heterozygosity in approximately 45% of patients with PVL, depending on the number of markers used.39 To our knowledge, this is the first study using WES in PVL, which revealed a range of complex SCNA and allelic-imbalance profiles. Recent data from several groups have found that 9p deletions encompassing 9p21 are significant and selective predictors of ICT resistance in advanced OSCC and lung cancer.23,24,40,41 This may be due to deletions encompassing the type I interferon gene cluster,42 which is often co-deleted with the tumor suppressor CDKN2A, highlighting a key mechanism of immune evasion.43 In our immunogenomic studies, only pretreatment 9p21.3 deletion yielded statistically significant differences: 6 of 10 patients with 9p21.3 deletion in baseline biopsies later developed cancer. We have previously shown that 9p21.3 copy-number loss is generally a focal event in oral precancer44 and associated with an immune-cold signal in OSCC23 that is enhanced by larger deletions extending to the telomeric band at 9p24.1.40 We speculate that resistance to the PD-1 inhibitor in this aggressive oral precancerous disease trial may have arisen during ICT resulting from increasing 9p deletion size to encompass 9p24.1, leading to low expression of the therapeutic target (PD-L1) and other immune gene depletion.23,40,45 PD-L1 is encoded by the CD274 gene, which is located on 9p24.1, close to 9p21, and is often co-deleted in advanced human papillomavirus–negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and lung cancers.42,44

Limitations

This study has limitations. We thought it was important to include patients with prior cancer events given their risk but recognize that this added some heterogeneity to the study population. This trial was single group and single center, using a novel clinical and pathologic scoring system to assess immunotherapy response in a hard-to-study oral precancer population. A lack of randomization or use of a time-to-event end point is another limiting factor to acknowledge.

Conclusions

We report the first (to our knowledge) nonrandomized clinical trial of ICT in patients with precancerous disease, specifically patients with high-risk oral precancer, to mitigate progression to OSCC. This trial met its primary response end point, but few patients had complete lesion regression. Other studies using immunotherapy to treat patients with high-risk oral premalignant lesions are ongoing.46,47 Recognizing the limitations and complexity of measuring treatment outcomes in precancer trials, for the first time, we demonstrate potential clinical activity and acceptable safety with the use of ICT in a population with high-risk precancer. A next step would be to consider a larger, precision immunotherapy randomized clinical trial favoring CFS as a primary outcome and stratified by prior history of early-stage treated OSCC and 9p21.3 loss.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Detailed Clinical and Pathologic Assessments of All Study Patients

eTable 2. Association Between Clinical and Pathologic Parameters and Cancer-Free Survival

eTable 3. Adverse Events Potentially Attributable to Nivolumab (N=33)

eTable 4. Clinical and Pathologic Predictors of Response

eFigure 1. Measurement of Effect and Response Assessment

eFigure 2. Immunologic Correlates of Response and Survival

eMethods. PD-L1 IHC, Tissue and Peripheral Blood Immunoprofiling and Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES)

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Mello FW, Miguel AFP, Dutra KL, et al. Prevalence of oral potentially malignant disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2018;47(7):633-640. doi: 10.1111/jop.12726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaturvedi AK, Udaltsova N, Engels EA, et al. Oral leukoplakia and risk of progression to oral cancer: a population-based cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(10):1047-1054. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speight PM, Khurram SA, Kujan O. Oral potentially malignant disorders: risk of progression to malignancy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;125(6):612-627. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2017.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torrejon-Moya A, Jané-Salas E, López-López J. Clinical manifestations of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a systematic review. J Oral Pathol Med. 2020;49(5):404-408. doi: 10.1111/jop.12999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villa A, Menon RS, Kerr AR, et al. Proliferative leukoplakia: proposed new clinical diagnostic criteria. Oral Dis. 2018;24(5):749-760. doi: 10.1111/odi.12830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Archibald H, Buryska S, Ondrey FG. An active surveillance program in oral preneoplasia and translational oncology benefit. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2021;6(4):764-772. doi: 10.1002/lio2.612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.William WN Jr, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Lee JJ, et al. Erlotinib and the risk of oral cancer: the Erlotinib Prevention of Oral Cancer (EPOC) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(2):209-216. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lippman SM, Batsakis JG, Toth BB, et al. Comparison of low-dose isotretinoin with beta carotene to prevent oral carcinogenesis. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(1):15-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301073280103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papadimitrakopoulou VA, William WN Jr, Dannenberg AJ, et al. Pilot randomized phase II study of celecoxib in oral premalignant lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(7):2095-2101. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen EEW, Soulières D, Le Tourneau C, et al. ; KEYNOTE-040 investigators . Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):156-167. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31999-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, et al. ; KEYNOTE-048 Investigators . Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394(10212):1915-1928. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32591-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G Jr, Fayette J, et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1856-1867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seiwert TY, Burtness B, Mehra R, et al. Safety and clinical activity of pembrolizumab for treatment of recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-012): an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):956-965. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30066-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanna GJ, Villa A, Mistry N, et al. Comprehensive immunoprofiling of high-risk oral proliferative and localized leukoplakia. Cancer Res Commun. 2021;1(1):30-40. doi: 10.1158/2767-9764.CRC-21-0060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spira A, Disis ML, Schiller JT, et al. Leveraging premalignant biology for immune-based cancer prevention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(39):10750-10758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608077113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mascaux C, Angelova M, Vasaturo A, et al. Immune evasion before tumour invasion in early lung squamous carcinogenesis. Nature. 2019;571(7766):570-575. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1330-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pennycuick A, Teixeira VH, AbdulJabbar K, et al. Immune surveillance in clinical regression of preinvasive squamous cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(10):1489-1499. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krysan K, Tran LM, Dubinett SM. Immunosurveillance and regression in the context of squamous pulmonary premalignancy. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(10):1442-1444. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Waal I, Schepman KP, van der Meij EH. A modified classification and staging system for oral leukoplakia. Oral Oncol. 2000;36(3):264-266. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(99)00092-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Cancer Institute . Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 5.0. US Department of Health and Human Services National Cancer Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magee DE, Hird AE, Klaassen Z, et al. Adverse event profile for immunotherapy agents compared with chemotherapy in solid organ tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(1):50-60. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen EEW, Bell RB, Bifulco CB, et al. The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer consensus statement on immunotherapy for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (HNSCC). J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):184. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0662-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.William WN Jr, Zhao X, Bianchi JJ, et al. Immune evasion in HPV- head and neck precancer-cancer transition is driven by an aneuploid switch involving chromosome 9p loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(19):e2022655118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2022655118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han G, Yang G, Hao D, et al. 9p21 Loss confers a cold tumor immune microenvironment and primary resistance to immune checkpoint therapy. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5606. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25894-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saba NF, Haigentz M Jr, Vermorken JB, et al. Prevention of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: removing the “chemo” from “chemoprevention”. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(2):112-118. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudin CM, Cohen EE, Papadimitrakopoulou VA, et al. An attenuated adenovirus, ONYX-015, as mouthwash therapy for premalignant oral dysplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(24):4546-4552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Lee JJ, William WN Jr, et al. Randomized trial of 13-cis retinoic acid compared with retinyl palmitate with or without beta-carotene in oral premalignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(4):599-604. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulshine JL, Atkinson JC, Greer RO, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIb trial of the cyclooxygenase inhibitor ketorolac as an oral rinse in oropharyngeal leukoplakia. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(5):1565-1573. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1020-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abadie WM, Partington EJ, Fowler CB, Schmalbach CE. Optimal management of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a systematic review of the literature. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153(4):504-511. doi: 10.1177/0194599815586779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pentenero M, Meleti M, Vescovi P, Gandolfo S. Oral proliferative verrucous leucoplakia: are there particular features for such an ambiguous entity? a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(5):1039-1047. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alabdulaaly L, Villa A, Chen T, et al. Characterization of initial/early histologic features of proliferative leukoplakia and correlation with malignant transformation: a multicenter study. Mod Pathol. 2022;35(8):1034-1044. doi: 10.1038/s41379-022-01021-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson LDR, Fitzpatrick SG, Müller S, et al. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: an expert consensus guideline for standardized assessment and reporting. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15(2):572-587. doi: 10.1007/s12105-020-01262-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren ZH, Xu JL, Li B, Fan TF, Ji T, Zhang CP. Elective versus therapeutic neck dissection in node-negative oral cancer: evidence from five randomized controlled trials. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(11):976-981. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiesa F, Tradati N, Marazza M, et al. Prevention of local relapses and new localisations of oral leukoplakias with the synthetic retinoid fenretinide (4-HPR): preliminary results. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1992;28B(2):97-102. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(92)90035-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuriakose MA, Ramdas K, Dey B, et al. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase IIB trial of curcumin in oral leukoplakia. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2016;9(8):683-691. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-15-0390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abbruzzese JL, Lippman SM. The convergence of cancer prevention and therapy in early-phase clinical drug development. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(4):321-326. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teixeira VH, Pipinikas CP, Pennycuick A, et al. Deciphering the genomic, epigenomic, and transcriptomic landscapes of pre-invasive lung cancer lesions. Nat Med. 2019;25(3):517-525. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0323-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spira A, Yurgelun MB, Alexandrov L, et al. Precancer atlas to drive precision prevention trials. Cancer Res. 2017;77(7):1510-1541. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kresty LA, Mallery SR, Knobloch TJ, et al. Frequent alterations of p16INK4a and p14ARF in oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(11):3179-3187. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao X, Cohen EEW, William WN Jr, et al. Somatic 9p24.1 alterations in HPV- head and neck squamous cancer dictate immune microenvironment and anti-PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(47):e2213835119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2213835119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ebot EM, Duncan DL, Tolba K, et al. Deletions on 9p21 are associated with worse outcomes after anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy but not chemoimmunotherapy. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2022;6(1):44. doi: 10.1038/s41698-022-00286-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barriga FM, Tsanov KM, Ho YJ, et al. MACHETE identifies interferon-encompassing chromosome 9p21.3 deletions as mediators of immune evasion and metastasis. Nat Cancer. 2022;3(11):1367-1385. doi: 10.1038/s43018-022-00443-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thol K, Pawlik P, McGranahan N. Therapy sculpts the complex interplay between cancer and the immune system during tumour evolution. Genome Med. 2022;14(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s13073-022-01138-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.William WN Jr, Zhang J, Zhao X, et al. Spatial PD-L1, immune-cell microenvironment, and genomic copy-number alteration patterns and drivers of invasive-disease transition in prospective oral precancer cohort. Cancer. 2023;129(5):714-727. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saloura V, Izumchenko E, Zuo Z, et al. Immune profiles in primary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Oral Oncol. 2019;96:77-88. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pembrolizumab in treating participants with leukoplakia. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03603223. Updated June 15, 2023. Accessed October 10, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03603223

- 47.Immune checkpoint inhibitor in high risk oral premalignant lesions (IMPEDE). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04504552. Updated December 1, 2020. Accessed October 10, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04504552

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Detailed Clinical and Pathologic Assessments of All Study Patients

eTable 2. Association Between Clinical and Pathologic Parameters and Cancer-Free Survival

eTable 3. Adverse Events Potentially Attributable to Nivolumab (N=33)

eTable 4. Clinical and Pathologic Predictors of Response

eFigure 1. Measurement of Effect and Response Assessment

eFigure 2. Immunologic Correlates of Response and Survival

eMethods. PD-L1 IHC, Tissue and Peripheral Blood Immunoprofiling and Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES)

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement