Abstract

HIV-1 infection is typically treated ≥2 drugs including at least one HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitor. Drugs targeting RT comprise nucleos(t)ide RT inhibitors (NRTIs) and non-nucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs). NRTI-triphosphates bind at the polymerase active site and, following incorporation, inhibit DNA elongation. NNRTIs bind at an allosteric pocket ~10 Å away from the polymerase active site. This study focuses on compounds (“NBD derivatives”) originally developed to bind to HIV-1 gp120, some of which inhibit RT. We have determined crystal structures of three NBD compounds in complex with HIV-1 RT, correlating with RT enzyme inhibition and antiviral activity, to develop structure-activity relationships. Intriguingly, these compounds bridge the dNTP and NNRTI binding sites, and inhibit the polymerase activity of RT in the enzymatic assays (IC50 <5 μM). Two of the lead compounds, NBD-14189 and NBD-14270, show potent antiviral activity (EC50 <200 nM) and NBD-14270 shows low cytotoxicity (CC50 > 100 μM).

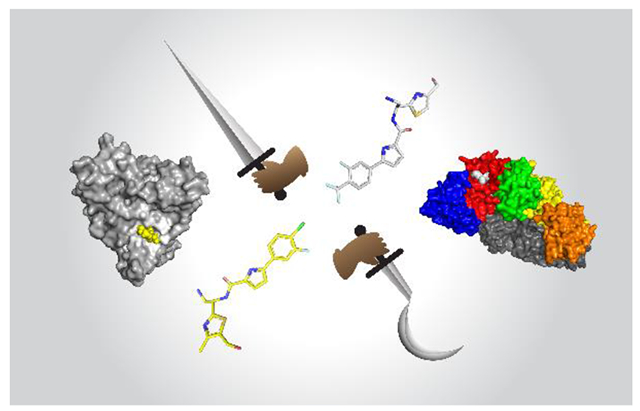

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

HIV-1 is a retrovirus that uses the enzyme reverse transcriptase (RT) to convert the viral single-stranded (ss)RNA into double-stranded (ds)DNA; almost half of the FDA-approved HIV-1 drugs target RT. Two types of FDA-approved drugs that target RT are nucleos(t)ide RT inhibitors (NRTIs) and non-nucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs). The NRTI and NNRTI binding sites are ~10 Å apart and several research groups have been attempting to develop bifunctional RT inhibitors that would bind both sites simultaneously1–3 or simply reach out of the NNRTI site.4,5

The entry of HIV-1 into host cells is mediated by the envelope glycoprotein gp120 binding to the host cell CD4 receptor. Since 2005, the Debnath laboratory has been developing a new class of HIV-1 entry antagonists (NBD compounds) that bind to the F43 cavity of gp120 and prevent Env-mediated cell-to-cell fusion of the virus to the host. Two of the NBD compounds present noteworthy antiviral activity (EC50 <200 nM) against HIV-1 wild-type.6–14 Additionally, HIV-1 RT inhibition assays revealed that some of the NBD compounds also have RT inhibitory activity against wild-type,9,11,13 against AZT-resistant mutants (e.g., D67N, K70R, T215F, and K219Q/E), which enhance excision via ATP binding, and against NNRTI-resistant mutants, e.g., K101P/K103N and K103N/Y181C, with low μM or nM EC50s.14

Here, we have explored RT inhibition in enzymatic assays (IC50) and viral inhibition and cytotoxicity in cellular assays (EC50 and CC50, Tables 1 and 2) for a series of NBD compounds. The lead compound, NBD-14189 (189 from now on; nomenclature applicable to any compound in the NBD-14000s series), has both (i) potent antiviral activity and (ii) RT inhibitory activity, while the compound 270 is a close second. However, 270 has the added benefit of lower cytotoxicity than 189 (see “Results and Discussion” section). We have solved crystal structures of HIV-1 RT in complexes with 189, 270, and 075 (Figures 1A–C and 2). All three compounds bind to a site where the previously reported bifunctional RT inhibitor, compound G from Merck3 (Figure 1D) and the allosteric RNase H inhibitor DHBNH1 (Figure 1E) bind, extending into the NNRTI-binding pocket (NNIBP) on one side, and extending (further than compound G and DHBNH) towards the polymerase active site into the nucleotide-binding site (N-site) from the other end. The NBDs have been optimized earlier for gp120 inhibition. Here we report the structure-activity relationships (SAR) for RT inhibition. Our results may enhance further improvement of these dual gp120/RT inhibitor leads in preclinical development.

Table 1.

Anti-HIV RT enzyme inhibition activity (IC50), antiviral activity (EC50) against HIV-1HXB2 in a single-cycle assay, and cytotoxicity (CC50) (TZM-bl cells).

| Compound | IC50 (μM) | Fold-change from best inhibitor | EC50 (μM) | Fold-change from best inhibitor | CC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBD-11021A2 9 | 43.44 | 31 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 25 | ~24 |

| NBD-14075 11 | 13.7 ± 1.4 | 9 | 0.57 ± 0.01 | 6 | 33 ± 0.2 |

| NBD-14088 11 | 7.2 ± 0.7 | 5 | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 5 | 38.8 ± 0.8 |

| NBD-14113 13 | 45.9 ± 3.6 | 31 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 37 | 84.1 ± 1.3 |

| NBD-14010 10 | 8.3 ± 0.1 | 6 | 0.59 ± 0.06 | 7 | 40.5 ± 1.3 |

| NBD-14107 11 | 8.4 | 6 | 0.64 ± 0.06 | 7 | 39.5 ± 2.3 |

|

| |||||

| NBD-14189 12 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1 | 0.089 ± 0.001 | 1 | 21.9 ± 0.5 |

| NBD-14270 14 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 2 | 0.16 ± 0.004 | 2 | 109.3 ± 2 |

| NBD-14227 14 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 2 | 0.3 ± 0.04 | 3 | 124 ± 7 |

| NBD-14235 14 | 5 ± 0.3 | 3 | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 4 | 85 ± 3 |

|

| |||||

| NBD-14306 14 | ND | ND | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 24 | >113 |

| NBD-14110 13 | 30.6 ± 2.7 | 20 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 26 | 145.6 ± 7.6 |

| NBD-14123 13 | 39.5 ± 2.8 | 26 | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 48 | 142.3 ± 2.6 |

| NBD-14159 13 | 28.1 ± 7.9 | 19 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 30 | 95.8 ± 1.4 |

| NBD-556 9 | >200 | >133 | 6.9±0.9 | 77.5 | ~60 |

| Nevirapine 9 | 0.2 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Some previous studies reported the antiviral assay results as “IC50”. Herein, these same values are reported as “EC50” to distinguish from the RT enzyme inhibition assays. All of the reported values represent the means ± standard deviations (n = 3). ND= Not determined.

Table 2.

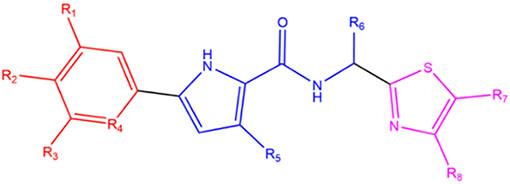

NBD substituents organized by similarity of the phenyl para and meta groups in the R1 and R2 columns.

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBD- | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | Enantiomer | |

| Halogen | 11021A2 | H | Cl | H | CH | H | CHNHCH2 CH2CH2CH2 | CH2OH | CH3 | 16R, 25S |

| 14075 | H | Cl | F | CH | H | CH2NH2 | CH2OH | H | R | |

| 14088 | H | CH3 | F | CH | H | CH2NH2 | CH2OH | H | R | |

| 14113 | H | F | F | CH | H | CH2NH2 | CH2OH | CH3 | R | |

| 14010 | H | Cl | F | CH | H | CH2NH2 | CH2OH | CH3 | S | |

| 14107 | F | Cl | F | CH | H | CH2NH2 | CH2OH | H | S | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Trifluoromethyl | 14189 | H | CF3 | F | CH | H | CH2NH2 | H | CH2OH | S |

| 14270 | H | CF3 | H | N | CH3 | CH2NH2 | CH2OH | H | S | |

| 14227 | H | CF3 | H | N | H | CH2NH2 | H | CH2OH | S | |

| 14235 | H | CF3 | H | N | CH3 | CH2NH2 | H | CH2OH | R | |

| 14306 | H | CF3 | H | N | H | CH2NH2 | CHOHCH2OH | H | R | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Dioxole | 14110 | H | OCH2O | CH | H | CH2NH2 | CH2OH | CH3 | S | |

| 14123 | H | OCH2O | CH | H | CH2NH2 | CH2OH | H | S | ||

| 14159 | H | OCH2O | CH | H | CH2NHCH3 | H | CH2OH | S | ||

All NBD compounds are referred to throughout the text by their last 3 digits (except for 11021A2)

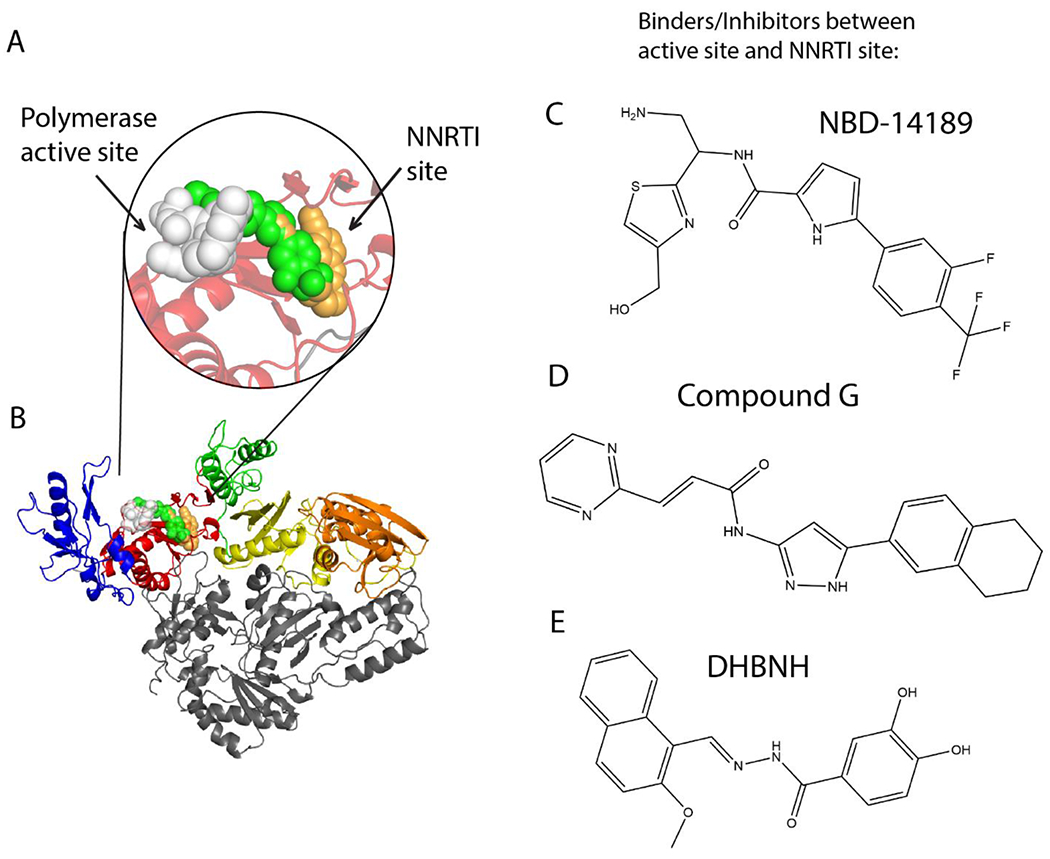

Figure 1.

NBD compound binding compared with other HIV-1 RT inhibitors. (A) Close-up view of bound NBD-14189 (189) represented as green space-filled model in complex with HIV-1 RT. Superposed onto the RT/189 structure are RPV (orange, overlapping 189) and AZT-TP (white). (B) Binding locations of 189, RPV, and AZT-TP on RT (fingers, palm, thumb, connection, and RNase H are colored blue, red, green, yellow, orange, respectively). (C) Chemical structure of NBD-14189 (189). Chemical structures of compounds binding similarly to 189: (D) Compound G (from PDB 5VZ6).3 (E) DHBNH (from PDB 2I5J).1

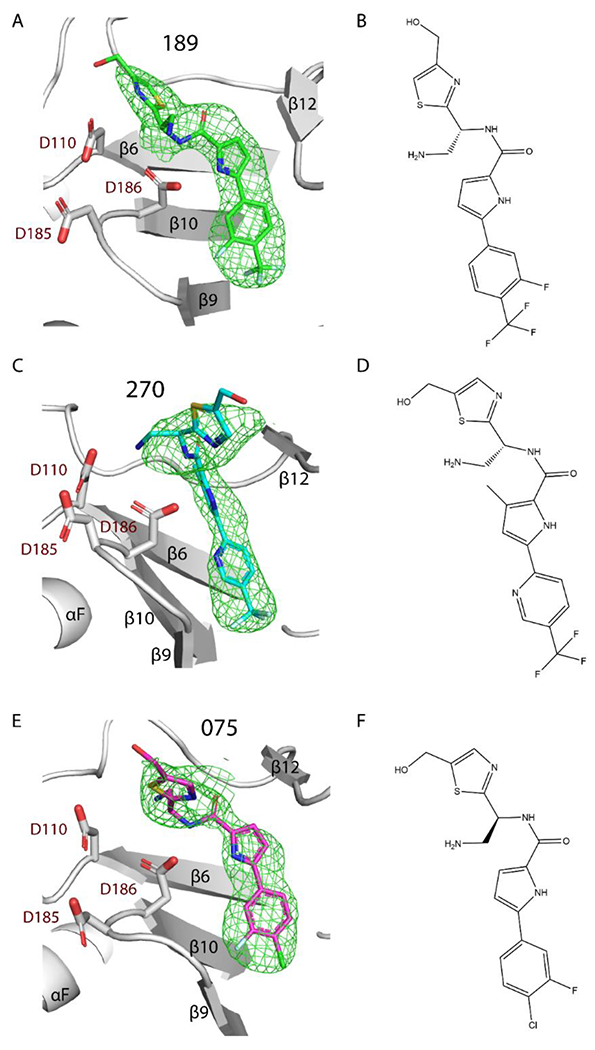

Figure 2.

Difference polder mFo – DFc map (green mesh) of 189, 270, and 075 in complex with RT (white ribbons, secondary structures labeled). PDB 7LPW, 7LPX, and 7LQU, respectively. Electron density maps of; (A) 189 (green sticks, map 5σ contours), (C) 270 (cyan sticks, map 5σ contours), (E) 075 (magenta sticks, map 4σ contours). Chemical structure of (B) 189, (D) 270, (F) 075.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

RT Inhibition and Antiviral Activity.

The compounds listed in Tables 1 and 2 are a small subset of sample generated over multiple generations8–14 of NBDs. The subset of compounds was selected based on their favorable RT inhibition (and related compounds for further SAR development). The backbone of each NBD is comprised of three components (Table 2): a thiazole ring that is solvent-exposed, a pyrrole ring (connected to the thiazole via a flexible spacer composed of an amide group plus a sp3 carbon), and the phenyl/pyridine that is completely buried. Substituents on the thiazole and spacer components are usually polar to enable favorable interactions with the solvent. The pyrrole component has small or no substituents, which makes the NBDs narrower. Finally, the phenyl/pyridine component has substituents in the para or meta positions that are less polar and/or decrease cytotoxicity. The NBD compounds can be divided into three groups based on their phenyl/pyridine substituents (Table 2): i) those with one, two, or three halogens [hereinafter referred to as the “halogen NBDs”]; ii) those with a trifluoromethyl group [hereinafter “trifluoromethyl NBDs”]; and iii) those with a dioxole group [hereinafter “dioxole NBDs”]. Assays for reverse transcription enzymatic inhibition (IC50s) and antiviral activity (EC50s) were completed with NBD-556 as a negative control and nevirapine as a positive control for each publication with all other NBD compounds in Table 1. NBD-556 behaves as a cell-entry agonist9, while all other NBDs listed in Table 1 display IC50s one or two orders of magnitude lower than NBD-556, implying antagonistic behavior and better candidates for inhibitors. Nevirapine (NVP) is a potent NNRTI drug, however, HIV-1 mutations are selected quickly after treatment with NVP.

The NBD halogen compounds have identical R4-R7 substituents (except for 11021A2), but 113 has significantly higher IC50 and EC50 values. Based on the IC50 values, it is uncertain whether the addition of the methyl group on the thiazole ring or the R2 change from Cl to F reduces activity. The higher EC50 for 113 suggests that the most unfavorable change is the R8 methyl addition on the thiazole. The single change at R2 from the Cl in 075 to a methyl in 088 resulted in an improved IC50 value (and a small improvement in EC50). Lastly, in 107, a second meta-F and chiral center change from R to S improved the IC50 value slightly, however, without improving its EC50 value.

The trifluoromethyl NBDs (189, 270, 235, and 227) have the most potent IC50 values, indicating that the trifluoromethyl R2 substituent is the most favorable for RT binding (also allowing for better bioavailability).15 189 and 270 are the best inhibitors, with 270 having a slightly higher IC50, which could be due to any of the four substituent changes or the chiral center change. The phenyl in 189 is instead a pyridine in all other trifluoromethyl NBDs, which increases their solubility. The meta-F in 189 is removed from all other compounds in the trifluoromethyl NBDs, suggesting that the meta-F (also present in the halogen NBDs) improves the IC50 value. The hydroxymethyl substituent presence on the thiazole ring (referred to hereinafter as the thiazole moiety) does not have a clear impact on inhibition efficacy. However, the dihydroxyethyl substitution in 306 (vs. hydroxymethyl in 270) led to a significant loss in antiviral potency (>24-fold, IC50 unavailable). The IC50 value increased from 227 to 235 with the change in chirality from S to R, suggesting RT inhibition is more efficient with an S enantiomer.

11021A2 and the three dioxole NBDs were the weakest inhibitors. 11021A2 showed the highest IC50 value, likely because the bulky ring on R6 is not favorable for interactions with RT, but it does not have the highest EC50 (due to its potent HIV-1 entry antagonist activity).11 123 had the lowest EC50 and showed the weakest inhibition of the dioxole NBDs, revealing that the methyl group on the pyrrole (referred to hereinafter as the pyrrole moiety) of 110 improved inhibition. It is unclear if 159’s increased efficacy is the result of switching the hydroxymethyl from R7 to R8 or the new methyl on R6. This group was the most similar to Compound G (Figure 1D) from Merck; however, Lai et al.,3 reported lower IC50 values, suggesting that the oxygens in the dioxole NBDs might hinder critical hydrophobic interactions. Overall, the NBD compounds with more hydrophobic substituents in the phenyl/pyridine region (hereinafter the phenyl/pyridine moiety) result in the most significant improvements to the IC50 and EC50 values.

X-ray Crystal Structures of 189, 270 and 075, and SAR.

Compounds 189, 270, and 075 were successfully co-crystallized with HIV-1 RT (Figure 2 and Table S1 in Supporting Information, SI). Additionally, the RT/010 complex was co-crystallized, but the electron density at the ligand-binding site was weak (Figure S1 in SI).

The compounds co-crystallized in this study bind at the region between the NNRTI and NRTI sites in the palm subdomain of RT, which we refer to as the NBD-binding pocket (Figure 1A and Figure 2). The common mode of binding of these compounds resembles the binding modes of earlier reported Compound G3 and DHBNH.1 There are two conserved interactions among all three crystallized NBDs and the two aforementioned bifunctional RT inhibitors (Figures 3 and S4): i) π–π stacking interactions with W229, a conserved residue located in the ‘primer grip’ that ensures appropriate positioning of the 3’ primer terminus for polymerization16 and ii) a hydrogen bond (or polar interaction) with catalytic residue D186.16 The three NBD compounds additionally make hydrophobic interactions with the side chain of F227. The interactions with W229 and F227 anchor the phenyl/pyridine and pyrrole moieties in this hydrophobic sub-pocket. Compound G shares this hydrophobic anchoring interaction with F227 in the pocket, but DHBNH does not (Figure S4). The conserved residue L23417 interacts with 189 and 075 (Figures 3A and 3C), but in the case of 270 the R5 methyl interacts with V108, accompanied by rearrangement of the pyrrole, preventing any potential interaction with L234 (Figure 3B). Compound G interacts with L234 at its phenyl/pyridine moiety (as opposed to the pyrrole moiety in the case of 189 and 075), but this interaction is not found in DHBNH.

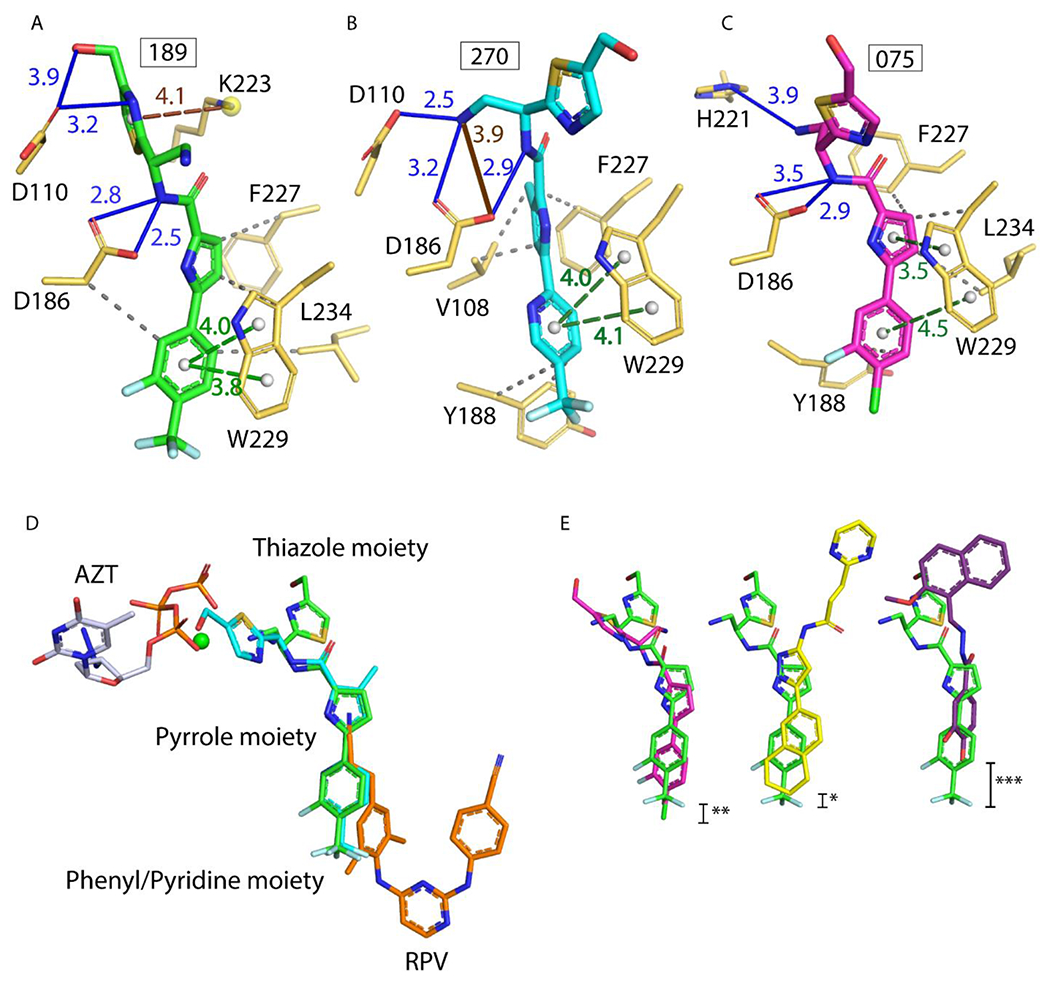

Figure 3.

Understanding the conserved and unique interactions of NBDs with HIV-1 RT. (A-C) Atomic models of RT with 189, 270, and 075 built with assistance from the PLIP server.21 All interactions were verified manually with Coot.22 Hydrogen bonds in blue solid lines, π-π stacking in green dashed lines, hydrophobic interactions in gray dashed lines, π-cation interaction in light brown dashed line (A) and one potential hydrogen bond in brown solid line (B). All distances measured in Å. (D) Superposition of: RT/189, RT/270, RT/ RPV (PDB 4G1Q), and RT/AZT-TP/calcium ion (PDB 5I42) (green, cyan, orange, and white/green sphere, respectively). Note RPV and AZT-TP do not bind simultaneously in vitro or in vivo. (E) 189 (green) superposed with 075 (magenta), then Compound G (yellow), and then DHBNH (purple). AZT-TP and RPV were hidden for clarity. Stars indicate degree of vertical displacement from 189 within the NBD-binding pocket.

In spite of both 189 and 270 having an S chiral center, their thiazole moieties are oriented in opposite directions, with the former pointing towards the polymerase active site and the latter to the solvent. This may be the result of switching the hydroxymethyl substituent from the R7 position to the R8 position or, more likely, from the addition of the methyl on the pyrrole ring (Figures 3A–B and 3D). The thiazole moiety of 075 (an R enantiomer) is positioned somewhat in an intermediate position relative to the two other NBDs (Figure 3E). Notably, while the positioning of the phenyl/pyridine moieties of both trifluoromethyl NBDs is almost equivalent, the phenyl moiety of 075 reaches deeper into the hydrophobic sub-pocket (region of NBD pocket that overlaps the NNIBP) (Figures 3E and 4C). Given the ~10-fold increase in the IC50 value of 075 vs. 189 and 270, this suggests that the phenyl/pyridine moiety of the trifluoromethyl NBDs have the correct positioning (i.e., correct alignment for π-π stacking with W229) and shape-complementarity for binding this sub-pocket of the NBD-binding pocket. Indeed, the shape-complementarity of a ligand filling a pocket is known to be critical for proper binding.18,19

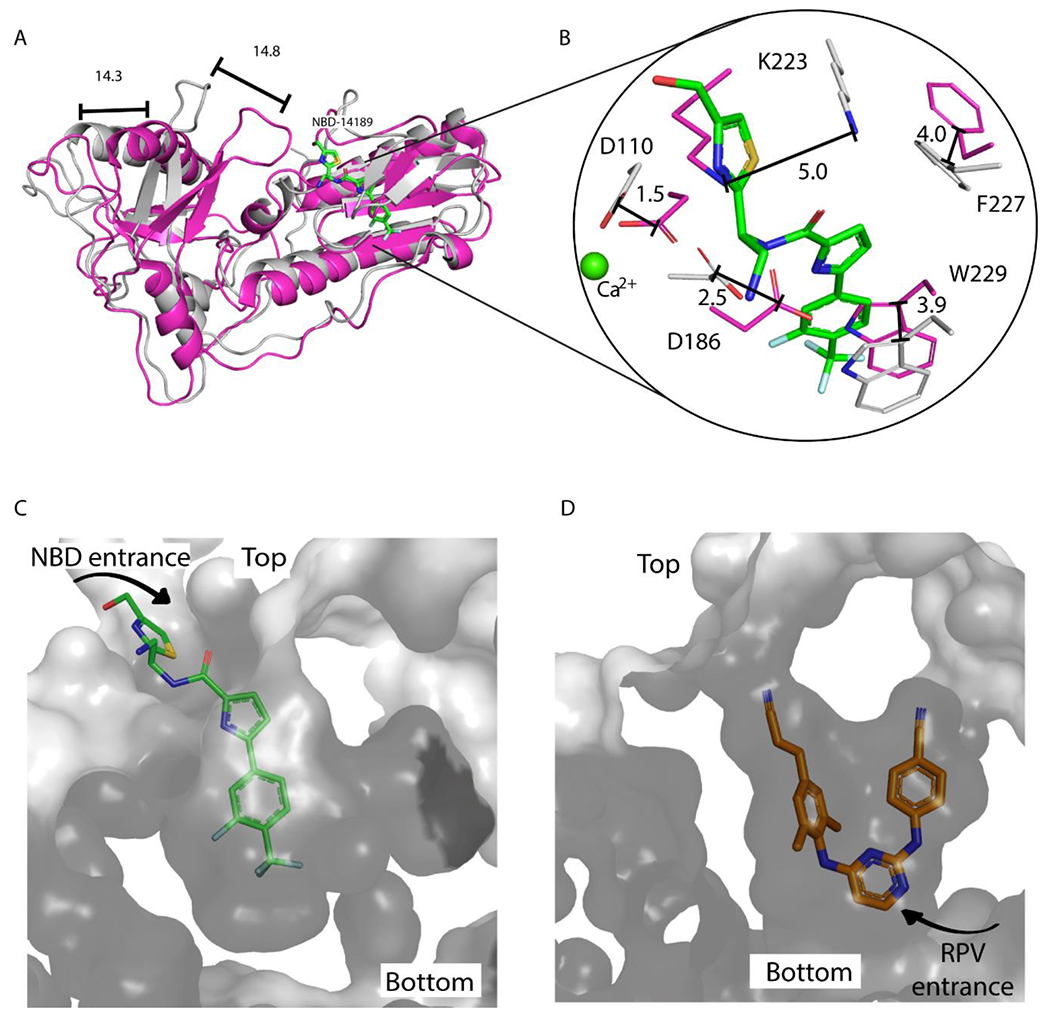

Figure 4.

Comparing conformational changes of HIV-1 RT upon binding of NBD versus DNA/AZT-TP versus RPV. Top panels: Comparison of RT/189 with RT bound to DNA, with shifts indicated with black bars and distances in Å. (A) RT/DNA/AZT-TP (PDB 5I42,25 RT in magenta ribbons) superposed with RT/189 complex (189 in green sticks, and RT in dark gray ribbons). (B) 189 (green sticks) in complex with RT (white sticks), superposed with RT from PDB 5I4225 (magenta sticks) and Ca2+ ion, to indicate active site location (green sphere). Bottom panels: Comparing RT/189 with RT bound to NNRTI. (C) 189 (green), RT protein surface (gray), and NBD-binding pocket showing the putative entrance from the top. (D) Rilpivirine (RPV, orange), RT surface (gray), and NNIBP showing the entrance from the bottom.

Similarly, the π-π stacking of the phenyl/pyridine moiety with W229 may be more optimal with the trifluoromethyl NBDs than in 075, as the two rings in W229 assume favorable parallel-displaced stacking with 189 and 270.18 For the halogen NBDs, like 075, the stacking of the phenyl moiety and pyrrole moiety with W229 has an angle ~20° (measured from the ring normal and the vector between the ring centroids), which could be less optimal (Figures 3A–C).

A comparison of the binding modes of three NBD compounds to RT suggest that the thiazole moiety is the most variable part in its positioning in the pocket. Nevertheless, all of them present the aforementioned key interaction with the amide NH making a hydrogen bond with D186 (Figures 3A–C). Moreover, both 189 and 270 have additional interaction with the catalytic residue D110. While the IC50 values are similar, the leaning of the thiazole ring of 189 towards the polymerase active site (270 goes towards the solvent) could be advantageous. This interaction with a second catalytic residue is also a unique feature of these trifluoromethyl NBDs, not present in 075, compound G, or DHBNH.

The three crystallized NBDs form favorable “syn”,20 symmetric hydrogen bonds with D186, and 189 and 270 have favorable geometry for their hydrogen bonds to D110 as well. Interestingly, the R6 amine in 270 makes hydrogen-bonding interactions with both D110 and D186, while 189 hydrogen bonds to D110 through the N on the thiazole. Importantly, the thiazole of 189 also forms a cation-π interaction with K223, which sandwiches and possibly stabilizes the thiazole moiety of 189. Maintaining this interaction will be valuable for future inhibitors. Additionally, weak (>3.5 Å) polar interactions are present in 189 (R8 methanol group and D110), 075 (R6 amine and H221), in compound G (with K223), and in DHBNH (with L228 main-chain atoms, Figure S4) that are located towards the top of the pocket.

In Figure 4A, the fingers and thumb subdomains of RT in the RT/189 are in a hyperextended position that is displaced >14 Å away from the closed, “catalytically competent conformation”.23 This hyperextension also accompanies RPV binding in the RT/RPV complex (PDB 4G1Q).24 The superposition of RT/189 with RT/DNA/AZT-TP (PDB 5I42)25 also shows a significant rearrangement of some residues in the binding pocket (Figure 4B). D110 and D186 ultimately undergo a small shift upon 189 binding. However, W229, K223, and F227 shift significantly to create space for the inhibitor. Therefore, if NBD compounds were to bind to RT/DNA complexes, this could require rearrangements of RT that might impair catalysis. However, Figure S3 shows that the thiazole region of 189 could be compatible with nucleic acid-binding. Interestingly, F227 moves closer to 189 without clashing, likely to compensate for the shift in the other residues.

In addition to their proximity to the polymerase active site, the phenyl/pyridine moiety of the NBD compounds occupies the NNIBP where the cyanovinyl-dimethylphenyl wing of rilpivirine (RPV) would be located (Figure 3D). As noted by Lai et al. for compound G,3 the NBD compounds most likely enter the NBD-binding pocket through the top, while NNRTIs enter the NNIBP through the bottom (Figures 4C–D). This can also be visualized by comparing the positioning of key NNIBP residues Y181 and Y188 (Figure S2B). The crystal unit cell dimensions of RT/189 and RT/RPV are essentially identical, and the thumb is hyperextended in both structures. However, there is notable rearrangement upon NBD binding that results in the RT backbone of the fingers shifting up to 3.9 Å and the thumb shifting up to 4.3 Å (Figure S2A). The side chains of the palm shift most dramatically (up to 5.1 Å) in the loop closest to the NBD entrance.

Based on these overlays, it is not clear whether the mechanism of inhibition by NBD compounds involves allosteric NNRTI inhibition, competition with incoming dNTP substrates, synergistic inhibition by both routes, or adoption of a distinct mechanism. Further biochemical experiments could help to distinguish among the possibilities.

Ongoing antiretroviral therapy (ART) has led to the evolution of drug-resistant and multi-drug-resistant HIV. Common NNRTI-resistance mutations potentially affecting NBDs include L100I, K101E, K103N, V108I, E138K (p51 subunit), Y181C, and Y188L. Upon superposition of the 189 NBD complex with other solved structures of RT NNRTI mutants, we anticipate that some mutations might not affect binding of the NBDs. L100I, K101E, and E138K are located 5 Å, 10 Å, and 6 Å, away from 189, respectively (measurements determined by the distance between the closest atom in 189 and the closest atom in the protein residue) and are not likely to make close contacts. V108 makes weak hydrophobic interactions with the pyrrole, while V108I could be accommodated and increase hydrophobic interactions with 189, 270, and 075. The main interaction of the phenyl/pyridine ring has extensive π–π stacking with W229, and weaker hydrophobic interactions with Y181 and Y188. It is likely that the common clinical mutations at Y181 and Y188 (Y181C, Y181I, Y188L etc.) will not alter the binding of the NBDs drastically. The common NRTI-resistance mutations M184I/V, K65R and Q151M are located about 7 Å, 13 Å, and 10 Å away from 189, respectively, suggesting that the mutations are unlikely to affect the binding of NBD compounds. Likewise, the AZT excision resistance mutations D67N, K70R, T215F, and K219Q/E are not likely to affect binding of the NBD compounds, as they are more than 10 Å away from the NBD pocket.

Extended SAR through AutoDock simulations.

To further understand and predict the potential RT binding modes of the other NBDs not solved in complex with RT (especially the dioxole NBDs), the AutoDock software suite26 was employed for model binding. AutoDock Vina27 predicts multiple potential binding conformations; hence the crystal structures of 189, 270, and 075 were used to determine the “best” conformation (closest match to experimental structure). Compound G, with its 1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene, was used as the experimental reference structure for the dioxole NBDs. To compare the binding predictions across compounds, calculated binding affinities were a relative guide rather than an absolute measurement, and ultimately the conformations were the deciding factor. The AutoDock Vina predictions of the phenyl/pyridine moiety conformation frequently matched the experimental structure, while the thiazole moiety conformations were not well predicted due to the many degrees of freedom (Figure S5). Further modelling with AutoDock with RT and gp120 can help predict substituents of the NBD pyrrole and phenyl/pyridine moieties for development. This will be especially valuable for the NBDs which have no crystal structures in complex to either target.

CONCLUSIONS

Developing a bifunctional inhibitor for HIV-1 RT has been an interest of many researchers for some time. Indeed, our laboratory (Arnold lab) suggested the idea of developing compounds that bridged the NNRTI and NRTI-binding sites as the first structures of RT in complex with NNRTI and with nucleic acid were solved28 as a potential way to improve efficacy and mitigate drug resistance. The NBD compounds bind partly in the NNIBP, but unlike bifunctional predecessors,1,3 they are flexible in their solvent-exposed region, allowing them to interact closely with two of the three polymerase catalytic residues (for 189 and 270, the lead NBDs), thereby bridging the NRTI- and NNRTI-binding sites (bifunctional). Additionally, the EC50 values are one or two orders of magnitude lower than the IC50 values against RT. However, it is still unclear if there is a synergistic or cumulative effect by the NBD compounds because of their dual-action (targeting both gp120 and RT).

Our SAR studies revealed key features of the NBDs that enhanced their efficacy. The meta-fluoro and para-trifluoromethyl substituents on the phenyl/pyridine moiety improved both the IC50 and EC50 values and bioavailability. The phenyl/pyridine moiety improved solubility and cytotoxicity but may result in a slight decrease in efficacy. Each NBD compound has a single chiral center that can form an R or S stereoisomer; however, only one of each enantiomeric pair was chosen for this study.10–14 The enantiomers not discussed here exhibited similar EC50s to their respective pair; therefore, the enantiomeric form of each NBD did not correlate with stronger or weaker inhibition. Additionally, our leads, 189 and 270, show broad-spectrum inhibition of multiple clades and mutants (including NNRTI-resistant mutants) of HIV-1 gp120 and RT12,14 and in some cases, show hypersusceptibility against the mutants.

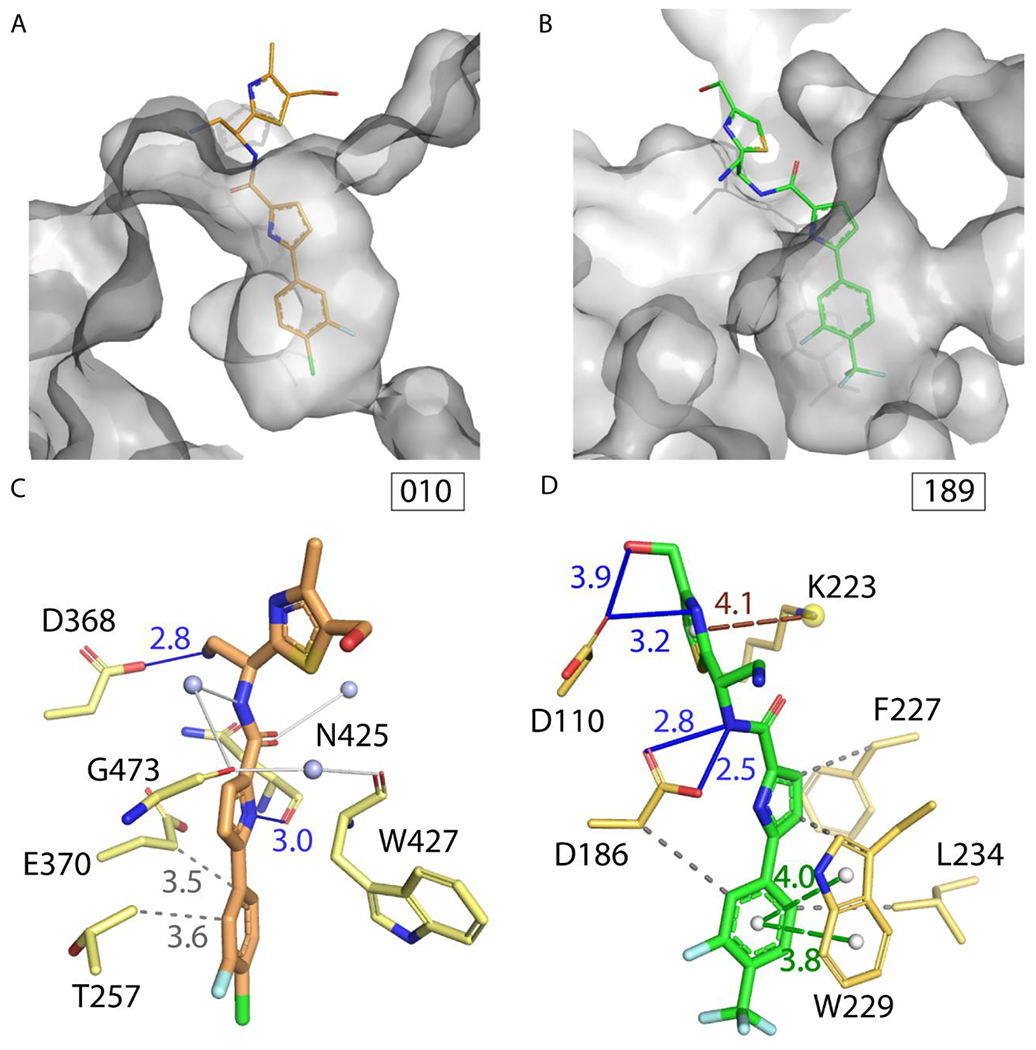

An analysis comparing the NBD binding pockets in HIV-1 gp120 and RT was done to understand more about their dual-targeting nature. In spite of being two structurally unrelated proteins, there are similar structural features of the NBD-binding pockets in gp120 and RT: i) the residues involved in interactions with NBDs, as well as ii) the number of hydrogen bond donors, and iii) amino acid composition (Table S3 in SI). Notably, there are hydrogen bonds of the solvent exposed portion of the NBD with an aspartate residue in both cases (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparing structural features of NBD-binding pockets in HIV-1 gp120 and RT. (A) 010 (orange sticks) in complex with gp120 (white surface, PDB 5U6E).11 (B) 189 (green sticks) in complex with RT (white surface). Bottom panel models built with assistance from the PLIP server.21 All interactions were verified manually with Coot.22 Hydrogen bonds in blue, π-π stacking in green, hydrophobic interactions in gray, π-cation interaction in brown, water bridges in white. (C) Atomic model of gp120 with 010. (D) Atomic model of RT with 189.

We plan to develop 189 and 270 further,29 focusing on the efficacy of 189 while retaining the low cytotoxicity of 270. Additional NRTI-interacting moieties will be carefully chosen to accommodate the binding pockets in both gp120 and RT, maintaining the favorable trifluoromethyl-aryl phenyl/pyridine moiety for both targets. Our next steps will be focused in three directions: 1) in-depth study of the biochemical mechanism of inhibition of the lead compounds 189 and 270 (Are the NBD compounds allosteric, competitive, or mixed inhibitors? Can they bind in the presence of nucleic acid?); 2) assessment of the RT inhibitory activity of other NBD compounds reported to have strong antiviral activity (including NRTI-resistant mutants) and using X-ray crystallography to determine their complex structures; and 3) evaluation of the in vitro ADMET and in vivo pharmacokinetics of the lead compounds 189 and 270 in laboratory animals. Ultimately, these efforts will inform the next steps for designing improved dual gp120/RT inhibitors with a bifunctional RT inhibition mode and broad-spectrum HIV antiviral activity. These compounds could potentially serve as a new type of weapon for combination therapy, especially for treatment-experienced patients.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemistry.

NBD compounds were synthesized as reported.8–14 Purity of all compounds is >95% (details of the analyses are reported in the Supporting Information).

RT Inhibition Assays and HIV-1 Antiviral Assays.

RT activity was measured with the colorimetric Reverse Transcriptase Assay (Roche) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, 1 ng of recombinant HIV-1 RT was diluted in lysis buffer to 20 μL and was combined with 20 μL of RT inhibitor (also diluted in lysis buffer) and 20 μL of reaction mixture. Reactions were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Samples were transferred to microplate (MP) modules, covered with foil, and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Solution was removed completely with washing buffer, and incubation was repeated with 200 μL anti-digoxigenin-peroxidase working dilution. Wash was repeated and 200 μL of substrate solution was added and incubated at 15-25°C until green color developed (10-30 min). Absorbance was measured at 405 nm.

The antiviral activity assays were measured in TZM-bl cells using a single-cycle infection. In brief, cells were plated in a 96-well tissue culture plate at 1×104/well and cultured at 37°C. Following overnight incubation, aliquots of HIV-1 pseudovirus pretreated with graded concentrations of the small molecules for 30 min were added to the cells and incubated for three days. Cells were washed and lysed with 50 μL of lysis buffer (Promega). Then 20 μL of the lysates were transferred to a white plate and mixed with the luciferase assay reagent (Promega). The luciferase activity was measured immediately with a Tecan Infinite M1000 reader. The cytotoxicity of the small molecules in TZM-bl cells was measured by the colorimetric method using XTT (PolyScience) as previously described.9 Cells were plated as described for the antiviral assays. Following overnight incubation, the cells were incubated with 100 μL of the compounds at graded concentrations and cultured for three days. The XTT solution was added to the cells, and 4 h later, the soluble intracellular formazan was quantified at 450 nm. The IC50, EC50, and CC50 values were calculated with GraphPad Prism software. All the reported values represent the means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

HIV-1 RT Expression, Purification, and Crystallization.

An engineered HIV-1 RT clade B construct, RT52A, here referred to as RT, was expressed and purified as described previously.30 NBD compounds were dissolved in DMSO to a stock concentration of 200 mM. Compounds were incubated with HIV-1 RT and β-octyl glucoside for 30 minutes at room temperature. Each compound was added to the protein mixture for a final concentration of 2 mM NBD, 170 μM RT, and 0.015% β-octyl glucoside. After incubation, the complex was manually added to hanging-drop crystal trays in triplicate. The well solution contained: 10% PEG 8,000, 4% PEG 400, 100 mM imidazole pH 6.6, 10 mM spermine, 15 mM MgSO4, 100 mM (NH4)2SO4, and 5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). The drops varied in ratios of protein mixture to well solution, which were 1:2, 1:1, and 2:1 (v:v). The higher ratios formed sufficient crystals, i.e., more than two crystals per drop with crystals measuring at least 10 microns in the shortest dimension.

Data Collection and Refinement.

The crystals were cryo-protected by dipping into a well solution supplemented with 25% ethylene glycol and then plunge-frozen in liquid N2. Diffraction data for co-crystals of RT with 189, 270, and 010 were collected at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) beamline ID7B2, while the co-crystal of RT with 075 was collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) beamline 9-2. The crystallographic software packages HKL200031 or iMOSFLM,32 and AIMLESS33 were used for data processing. The software package Phenix34 was used for molecular replacement and structure refinement and COOT22 for model building. The structures were solved by molecular replacement using PDB ID 4G1Q24 as the search model. The diffraction data and refinement statistics are summarized in Table S1 in SI. Polder maps were calculated to confirm the presence of the ligands.35

AutoDock Vina

Molecular docking was performed with AutoDock Vina.27 The NBD compounds (ligands) and RT (protein receptor) coordinate files were prepared as described26 using AutoDockTools (ADT). AutoGrid was used to create and solvate an 18.75 Å3 3D grid around the NBD binding pocket, centered around the pyrrole moiety. Four to nine random poses were automatically generated for each ligand by AutoDock Vina. Redocking of the NBD ligands solved in complex with RT was used as a method control. Results were visualized in PyMOL, and poses were manually inspected to determine the conformations closest to the experimental crystal structure.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the CHESS ID7B2 and SSRL 9-2 beamline facilities for data collection. E.A. acknowledges National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 AI027690 for support. A.K.D. acknowledges NIH R01 award AI104416 for support.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- HIV-1

human immunodeficiency virus type 1

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- NNRTI

non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

- NRTI

nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

- AZT

azidothymidine

- RPV

rilpivirine

- DHBNH

dihydroxy benzoyl naphthyl hydrazone

- dNTP

deoxynucleotide triphosphate

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Himmel DM; Sarafianos SG; Dharmasena S; Hossain MM; McCoy-Simandle K; Ilina T; Clark AD; Knight JL; Julias JG; Clark PK; Krogh-Jespersen K; Levy RM; Hughes SH; Parniak MA; Arnold E HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Structure with RNase H Inhibitor Dihydroxy Benzoyl Naphthyl Hydrazone Bound at a Novel Site. ACS Chem. Biol 2006, 1 (11), 702–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Bailey CM; Sullivan TJ; Iyidogan P; Tirado-Rives J; Chung R; Ruiz-Caro J; Mohamed E; Jorgensen W; Hunter R; Anderson KS Bifunctional Inhibition of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Reverse Transcriptase: Mechanism and Proof-of-Concept as a Novel Therapeutic Design Strategy. J. Med. Chem 2013, 56 (10), 3959–3968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Lai MT; Tawa P; Auger A; Wang D; Su HP; Yan Y; Hazuda DJ; Miller MD; Asante-Appiah E; Melnyk RA Identification of Novel Bifunctional HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2018, 73 (1), 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Pata JD; Stirtan WG; Goldstein SW; Steitz TA Structure of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Bound to an Inhibitor Active against Mutant Reverse Transcriptases Resistant to Other Nonnucleoside Inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2004, 101 (29), 10548–10553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Su H-P; Yan Y; Prasad GS; Smith RF; Daniels CL; Abeywickrema PD; Reid JC; Loughran HM; Kornienko M; Sharma S; Grobler JA; Xu B; Sardana V; Allison TJ; Williams PD; Darke PL; Hazuda DJ; Munshi S Structural Basis for the Inhibition of RNase H Activity of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase by RNase H Active Site-Directed Inhibitors. J. Virol 2010, 84 (15), 7625–7633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Zhao Q; Ma L; Jiang S; Lu H; Liu S; He Y; Strick N; Neamati N; Debnath AK Identification of N-Phenyl-N′-(2,2,6,6-Tetramethyl-Piperidin-4-Yl)- Oxalamides as a New Class of HIV-1 Entry Inhibitors That Prevent Gp120 Binding to CD4. Virology 2005, 339 (2), 213–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kwon Y. Do; Finzi A; Wu X; Dogo-Isonagie C; Lee LK; Moore LR; Schmidt SD; Stuckey J; Yang Y; Zhou T; Zhu J; Vicic DA; Debnath AK; Shapiro L; Bewley CA; Mascola JR; Sodroski JG; Kwong PD Unliganded HIV-1 Gp120 Core Structures Assume the CD4-Bound Conformation with Regulation by Quaternary Interactions and Variable Loops. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012, 109 (15), 5663–5668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Curreli F; Kwon Y. Do; Zhang H; Yang Y; Scacalossi D; Kwong PD; Debnath AK. Binding Mode Characterization of NBD Series CD4-Mimetic HIV-1 Entry Inhibitors by X-Ray Structure and Resistance Study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2014, 58 (9), 5478–5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Curreli F; Kwon Y. Do; Zhang H; Scacalossi D; Belov DS; Tikhonov AA; Andreev IA; Altieri A; Kurkin AV; Kwong PD; Debnath AK. Structure-Based Design of a Small Molecule CD4-Antagonist with Broad Spectrum Anti-HIV-1 Activity. J. Med. Chem 2015, 58 (17), 6909–6927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Curreli F; Belov DS; Ramesh RR; Patel N; Altieri A; Kurkin AV; Debnath AK Design, Synthesis and Evaluation of Small Molecule CD4-Mimics as Entry Inhibitors Possessing Broad Spectrum Anti-HIV-1 Activity. Bioorganic Med. Chem 2016, 24 (22), 5988–6003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Curreli F; Kwon Y. Do; Belov DS; Ramesh RR; Kurkin AV; Altieri A; Kwong PD; Debnath AK Synthesis, Antiviral Potency, in Vitro ADMET, and X-Ray Structure of Potent CD4 Mimics as Entry Inhibitors That Target the Phe43 Cavity of HIV-1 Gp120. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60 (7), 3124–3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Curreli F; Belov DS; Kwon Y. Do; Ramesh R; Furimsky AM; O’Loughlin K; Byrge PC; Iyer LV; Mirsalis JC; Kurkin AV; Altieri A; Debnath AK Structure-Based Lead Optimization to Improve Antiviral Potency and ADMET Properties of Phenyl-1H-Pyrrole-Carboxamide Entry Inhibitors Targeted to HIV-1 Gp120. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2018, 154, 367–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Curreli F; Belov DS; Ahmed S; Ramesh RR; Kurkin AV; Altieri A; Debnath AK Synthesis, Antiviral Activity, and Structure–Activity Relationship of 1,3-Benzodioxolyl Pyrrole-Based Entry Inhibitors Targeting the Phe43 Cavity in HIV-1 Gp120. ChemMedChem 2018, 13 (21), 2332–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Curreli F; Ahmed S; Benedict M; Iusupov IR; Belov DS; Markov PO; Kurkin AV; Altieri A; Debnath AK. Preclinical Optimization of Gp120 Entry Antagonists as Anti-HIV-1 Agents with Improved Cytotoxicity and ADME Properties through Rational Design, Synthesis, and Antiviral Evaluation. J. Med. Chem 2020, 5, 1724–1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Purser S; Moore PR; Swallow S; Gouverneur V Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev 2008, 37 (2), 320–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Sarafianos SG; Marchand B; Das K; Himmel DM; Parniak MA; Hughes SH; Arnold E Structure and Function of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase: Molecular Mechanisms of Polymerization and Inhibition. Journal of Molecular Biology. Academic Press January 23, 2009, 693–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wapling J; Moore KL; Sonza S; Mak J; Tachedjian G Mutations That Abrogate Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Reverse Transcriptase Dimerization Affect Maturation of the Reverse Transcriptase Heterodimer. J. Virol 2005, 79 (16), 10247–10257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Bissantz C; Kuhn B; Stahl M A Medicinal Chemist’s Guide to Molecular Interactions. J. Med. Chem 2010, 53 (14), 5061–5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Huggins DJ; Sherman W; Tidor B Rational Approaches to Improving Selectivity in Drug Design. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. American Chemical Society February 23, 2012, 1424–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Gorbitz CH; Etter MC Hydrogen Bonds to Carboxylate Groups. The Question of Three-Centre Interactions. J. CHEM. SOC. PERKIN TRANS 1992, 2 (1), 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Salentin S; Schreiber S; Haupt VJ; Adasme MF; Schroeder M PLIP: Fully Automated Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43 (W1), W443–W447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Emsley P; Cowtan K Coot: Model-Building Tools for Molecular Graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr 2004, 60 (Pt 12 Pt 1), 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Singh K; Marchand B; Kirby KA; Michailidis E; Sarafianos SG Structural Aspects of Drug Resistance and Inhibition of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase. Viruses. February 2010, 606–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Kuroda DG; Bauman JD; Challa JR; Patel D; Troxler T; Das K; Arnold E; Hochstrasser RM Snapshot of the Equilibrium Dynamics of a Drug Bound to HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase. Nat. Chem 2013, 5 (3), 174–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Das K; Balzarini J; Miller MT; Maguire AR; DeStefano JJ; Arnold E Conformational States of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase for Nucleotide Incorporation vs Pyrophosphorolysis - Binding of Foscarnet. ACS Chem. Biol 2016, 11 (8), 2158–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Forli S; Huey R; Pique ME; Sanner MF; Goodsell DS; Olson AJ Computational Protein-Ligand Docking and Virtual Drug Screening with the AutoDock Suite. Nat. Protoc 2016, 11 (5), 905–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Trott O; Olson AJ AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem 2010, 31 (2), 455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Nanni RG; Ding J; Jacobo-Molina A; Hughes SH; Arnold E Review of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Three-Dimensional Structure: Implications for Drug Design. Perspect. Drug Discov. Des 1993, 1 (1), 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zhang S; Zhang J; Gao P; Sun L; Song Y; Kang D; Liu X; Zhan P Efficient Drug Discovery by Rational Lead Hybridization Based on Crystallographic Overlay. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24 (3), 805–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Bauman JD; Das K; Ho WC; Baweja M; Himmel DM; Clark AD; Oren DA; Boyer PL; Hughes SH; Shatkin AJ; Arnold E Crystal Engineering of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase for Structure-Based Drug Design. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36 (15), 5083–5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Otwinowski Z; Minor W Processing of X-Ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997, 276, 307—326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Battye TGG; Kontogiannis L; Johnson O; Powell HR; Leslie AGW IMOSFLM: A New Graphical Interface for Diffraction-Image Processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr 2011, 67 (Pt 4), 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Evans PR; Murshudov GN How Good Are My Data and What Is the Resolution? Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr 2013, 69 (Pt 7), 1204–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Adams PD; Afonine PV; Bunkóczi G; Chen VB; Davis IW; Echols N; Headd JJ; Hung L-W; Kapral GJ; Grosse-Kunstleve RW; McCoy AJ; Moriarty NW; Oeffner R; Read RJ; Richardson DC; Richardson JS; Terwilliger TC; Zwart PH. PHENIX: A Comprehensive Python-Based System for Macromolecular Structure Solution. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr 2010, 66 (Pt 2), 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Liebschner D; Afonine PV; Moriarty NW; Poon BK; Sobolev OV; Terwilliger TC; Adams PD. Polder Maps: Improving OMIT Maps by Excluding Bulk Solvent. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D, Struct. Biol 2017, 73 (Pt 2), 148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.