Abstract

In contrast to other Children’s Oncology Group (COG) committees, the COG Nursing discipline is unique in that it provides the infrastructure necessary for nurses to support COG clinical trials and implements a research agenda aimed at scientific discovery. This hybrid focus of the discipline reflects the varied roles and expertise within pediatric oncology clinical trials nursing that encompass clinical care, leadership, and research. Nurses are broadly represented across COG disease, domain, and administrative committees, and are assigned to all clinically-focused protocols. Equally important is the provision of clinical trials-specific education and training for nurses caring for patients on COG trials. Nurses involved in the discipline’s evidence-based practice initiative have published a wide array of systematic reviews on topics of clinical importance to the discipline. Nurses also develop and lead research studies within COG, including stand-alone studies and aims embedded in disease/ treatment trials. Additionally, the nursing discipline is charged with responsibility for developing patient/family educational resources within COG. Looking to the future, the nursing discipline will continue to support COG clinical trials through a multifaceted approach, with a particular focus on patient-reported outcomes and health equity/disparities, and development of interventions to better understand and address illness-related distress in children with cancer.

Keywords: Clinical trials, pediatric cancer, nursing

INTRODUCTION

The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Nursing discipline is fundamental for the conduct of successful COG clinical trials, as evidenced by the multiple roles nurses have within the group. Nursing is the largest discipline within COG; with over 2400 members, nurses comprise more than 25% of the group’s overall membership.1 The mission of the COG nursing discipline is to set standard of excellence for the care of children, adolescents, and young adults with cancer treated on COG clinical trials from diagnosis to survivorship, and to transform pediatric oncology clinical trials nursing through education, evidence-based practice and research. In the previously published Blueprint for COG Nursing, two overarching aims were established to address key gaps in knowledge affecting nursing care of children with cancer enrolled on clinical trials by i) understanding the effective delivery of patient/family education and ii) reducing illness-related distress.2 These overarching aims are integrated into all aspects of the work of the COG nursing discipline. Here, we provide a concise overview of the work accomplished toward these aims over the past decade. We describe the organizational structure of the discipline and detail how the work and accomplishments of the discipline’s subcommittees have contributed toward the overarching aims. An outline of future goals for the discipline over next decade is provided with a focus on sustainability, dissemination, and innovation.

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE NURSING DISCIPLINE

In contrast to other COG committees, the COG Nursing discipline is unique in that it provides both the infrastructure necessary for nurses to support COG clinical trials and implements a research agenda aimed at discovery. This hybrid focus of the discipline reflects the varied roles and expertise within pediatric oncology clinical trials nursing that encompass clinical care, leadership, and research. Nurses are broadly represented across COG disease, domain, and administrative committees, and are assigned to all clinically-focused protocols. Nurses also develop and lead research studies within COG, including stand-alone studies and aims embedded in disease/treatment trials. Additionally, the nursing discipline is charged with responsibility for all patient/family educational resources within COG.

The Nursing discipline Steering Committee is comprised of three elected members – the Chair and two Members-at-Large. Each elected Member-at Large has role-specific responsibilities; one oversees the discipline’s patient and family educational resources and the other oversees discipline membership and serves as the discipline’s liaison with the Association of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nurses (APHON). The Chair appoints the remainder of the Steering Committee, including the Vice Chair, Associate Vice Chairs, Subcommittee Chairs, Communications Chair, and Special Assistant.

The current Nursing committee structure is designed to reflect the diverse and unique roles held by COG nurses, to support the discipline’s hybrid focus, and to enable the work necessary to realize the discipline’s mission. The discipline is organized into four subcommittees: clinical trials, education, evidence-based practice, and research (Figure 1). The success of the Nursing discipline relies on the intersection among these established subcommittees.

Figure 1. Nursing Discipline Subcommittees.

Abbreviation: COG=Children’s Oncology Group

Nursing Clinical Trials Subcommittee

A core responsibility of the COG Nursing discipline is supporting the infrastructure of clinical trials operations. One way the Nursing Clinical Trials Subcommittee achieves this is by facilitating expert nursing representation on COG committees, including disease and domain steering committees and protocol committees.

Highly experienced COG nurses, known as Disease Committee Nurses (DCNs), are selected by nursing leadership through a competitive process to serve on disease and domain steering committees. Additional nurses, known as core group nurses, are selected to serve as protocol nurses in their areas of expertise. DCNs oversee the assignment of protocol nurses from within the core groups; ideally, these nurses are appointed during the study pre-concept phase. Responsibilities of protocol nurses include responding in real-time to protocol and care-related questions that arise from COG members caring for patients enrolled on clinical trials. Often, these inquiries are aimed at ensuring that protocol requirements are not compromised, which maintains the quality of clinical trials data and averts potential protocol violations. Protocol nurses also serve in a feedback loop to study committees, providing updates on frequently asked questions and protocol concerns that have been reported, thereby informing important protocol amendments. For example, recently, the core nursing group for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) trials consolidated frequently asked questions (FAQs) about blinatumomab into a FAQ document that is posted with the protocol materials for the current trials AALL1731 and AALL1821. COG nurses report that this document is a useful resource, and is particularly helpful at the site level at the time of study activation.3 The DCNs and core nurses also review all patient and family-facing COG clinical trials information prior to distribution. These have included Clinical Trial Summaries (CTS), which provide an overview of the clinical trial’s primary aims, and Return of Results (ROR) Summaries, which summarize the main results of published clinical trials. Leadership of the ROR Committee within COG has included nurses since inception,4 and the current ROR committee is co-led by two nurses.

Outside of the formal roles described here, nurses champion COG clinical trials at the institutional level. Nurses coordinate and provide protocol-directed care, with meticulous attention to detail to ensure adherence to protocol requirements. Nurses also advocate for COG clinical trials by raising awareness of these trials during patient/family discussions and treatment planning. COG Supportive Care clinical trials (also known as Cancer Control [CCL] trials) are often aligned with the Nursing discipline’s aim of reducing illness-related distress. COG advanced practice nurses champion supportive care trials, which has increased overall enrollment of these trials.5

Nursing Education Subcommittee

Equally important to supporting COG clinical trials is the provision of education and training for nurses caring for patients enrolled on COG trials, which is the primary focus of the Nursing Education subcommittee. Education and training provided by the subcommittee are presented at two main forums – the COG educational track at the APHON annual conference, and nursing educational sessions embedded within the COG annual meeting.

Many nurses providing care to patients on COG clinical trials are not COG members; therefore, a priority of the Committee is providing access to COG clinical trials education targeted to a broader pediatric oncology nursing community. Through a partnership with APHON established in 2010, the subcommittee presents COG educational tracks at the annual APHON conference, which is typically attended by approximately 1000 pediatric oncology nurses. To further promote access to this education, these COG educational tracks are recorded and made available as on-demand learning modules.6 A COG nursing VIMEO page (vimeo.com/cognursing) currently houses the modules, making them accessible to all pediatric oncology nurses. Content for the COG educational track sessions is selected by the COG nursing leadership with the goal of disseminating high-priority clinical trials information to the broader pediatric oncology nursing audience that attends APHON conferences. COG Nursing leadership performs a rigorous review of all COG track content prior to these presentations to ensure compliance with COG and human research subject confidentiality policies.

COG’s partnership with APHON includes other opportunities for disseminating COG clinical trials information to the pediatric oncology nursing community. The quarterly APHON Counts newsletter features a COG clinical trials column authored by COG nurses. Additionally, several of the COG educational tracks have been made available by APHON as continuing education (CE) webinars.

Obtaining CE credits is a priority for many nurses. To address this need, educational sessions offering CEs have been embedded within the COG annual Nursing meetings. Presenting educational content for COG nurses at the annual meetings offers the advantage of inclusion of confidential content that cannot be presented in the public domain. Often, this content includes critical information related to caring for patients and successfully navigating protocol requirements of ongoing open COG clinical trials. Table 1 provides a summary of topics from both the COG educational tracks at APHON and the nursing CE sessions at COG meetings over the past decade.

Table 1.

COG Educational Track Sessions at APHON and COG Fall Meeting Nursing Educational Sessions, 2013–2022

| Year | Topic |

|---|---|

| COG Educational Track Sessions Presented at the Association of Pediatric Hematology Oncology Nurses Annual Conference | |

| 2013 | 1. Confidently caring for children with brain tumors on COG clinical trials 2. Confidently caring for children with high-risk B-ALL 3. Confidently caring for children receiving CH14:18 on COG clinical trials 4. Confidently caring for children with Down Syndrome on a clinical trial 5. Clinical trials and you: What you need to know to confidently care for patients and families |

| 2014 | 1. Pediatric Myeloid Leukemias: The Role of Stem Cell Transplant and Supportive Care (pre-conference) 2. Hodgkin Lymphoma: Evolution through Revolution – Transitioning Toward Targeted Therapy 3. Novel Therapeutics: Advancing Pediatric Oncology in COG 4. Whatever Happened with My COG Clinical Trial? How to Help Patients and Families Get Results 5. Late Effects and Clinical Trials in COG 6. Innovation, Communication, Motivation: Keys to Adherence |

| 2015 | 1. ALL COG Clinical Trials for Ph+ and Ph-like 2. Pediatric Bone Tumors: Meeting the challenges through COG clinical Trials 3. Demystifying ANHL113: An intergroup trial for High-Risk B-Cell Malignancies 4. Radiation Therapy: Lessons learned from COG clinical trials 5. Pre-conference workshop on Evidence-Based Practice |

| 2016 | 1. Using COG resources to optimize your nursing practice 2. Project Every Child: A new strategic approach for the Children’s Oncology Group 3. Molecular Subtyping: An update on COG protocols for CNS tumors 4. Advancing AYA therapy through COG clinical trials 5. AALL1331: Blinatumomab for first relapse of childhood B-ALL 6. 40 years of clinical trials nursing |

| 2017 | 1. Patient/Family Education in Pediatric Oncology: The Children’s Oncology Group Experience 2. Nurse-Led Models for Enhancing the Conduct of Children’s Oncology Group Cancer Control Trials 3. Putting Evidence into Practice: Results from Two COG EBP Teams 4. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: Current COG treatment for a unique AML subtype 5. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Current COG Trials for T Cell, Ph+, and Ph-Like ALL 6. The landscape of neuroblastoma in COG: yesterday, today and tomorrow’s therapies |

| 2018 | 1. A Tale of Two MABs: Blinatumomab and Inotuzumab in COG Clinical Trials for Relapsed B ALL 2. Are Your Patients with Advanced Cancer Suffering? A Nurse-Led Study Utilizing Technology to Measure Symptoms 3. Therapeutic and Supportive Care Protocols Paving the Way to a Brighter Future for Children with AML: Children’s Oncology Group Experience |

| 2019 | 1. Navigating 131I-MIBG and CAR T 19, in COG trials ANBL1531 and AALL1721: Sharing Care and Strategies for Success 2. Infant ALL: Rearranged for the Big Screen! Providing Care on COG AALL15P1, Nurses in a Leading Role! 3. Livers, Kidneys, and Germ Cells–Oh My! Helping Nurses Understand the Children’s Oncology Group Approach to Unique Childhood Cancers 4. Shaping the Future with Clinical Trials: Empowered Nurses a Key to Their Success 5. Beyond the Cure: The Children’s Oncology Group Uses Evidence and Clinical Trials to Study Late Effects in Childhood Cancer Survivors 6. Engaging Pediatric Oncology Nurses in Multi-Site Clinical Trials |

| 2020 | 1. Enhancing Patient/Family Education with Children’s Oncology Group Tools and Resources 2. High Risk Neuroblastoma in the new decade: Incorporating targeted therapies to maximize impact in current Children’s Oncology Group trials 3. How to Return Research Results to Patients and Families? The Children’s Oncology Group Experience 4. Less is More in Childhood B-ALL: Targeted immunotherapies, MRD by HTS, and De-escalation of Therapy in COG Trials AALL1731/AALL1732 |

| 2021 | 1. Incorporating COG Health Links into Clinical Practice 2.Clinical Trials in the Children’s Oncology Group: A Case Study Approach 3. Caring for Children on COG AML Protocols: Quick Hits and Nursing Tips 4. Lighting the Way in COG with MATCH: Targeted Therapies in Pediatric CNS Tumors |

| 2022 | 1. Using Shared Experience to Define Optimal Care for Patients Receiving Blinatumomab on COG Clinical Trials 2. Hot Topics in Pediatric Oncology: Updates from the Children’s Oncology Group 3. Using their own words: AYA cancer patients as Influencers of COG clinical trials 4. Targeting patient and family education of MEK/ALK inhibitor therapy COG Nursing EBP project |

| COG Fall Meeting Educational Sessions | |

| 2013 | 1. Cytogenetics Overview 2. Traineeship Updates: Stress Experienced by Parents of Children Recovering from the Acute Phase of HSCT, Vincristine-Related Toxicity in Children Treated for ALL on CCG-1961 |

| 2014 | 1. Assessing Toxicity on AALL1131 and ACNS0831 |

| 2015 | 1. Blinatumomab in first relapse of B-ALL |

| 2016 | 1. APEC14B1 Project Every Child 2. Patient/Family Education Update: What we have learned |

| 2017 | 1. Update from EBP teams 2. Protocol highlight AALL1131 |

| 2018 | 1. Protocol highlight ANBL1531 2. Update from EBP teams |

| 2019 | 1. COG Supportive Care Guidelines Committee 2. ROR Committee |

| 2020 | 1. COG Resources for Patient and Family Education |

| 2021 | 1. ACCL20NICD-Financial Distress during Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment in the US 2. Sexual Health among Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors 3. Clinical Translations Task Force within Outcomes & Survivorship Committee |

| 2022 | 1. Shared Experience Administering and Caring for Patients Receiving Blinatumomab on COG trials – Blinatumomab in COG and Survey Highlights 2. Update on EBP review – MEK and ALK Inhibitors in Pediatric Cancer |

Abbreviations: ALL=Acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML=acute myeloid leukemia; APHON=Association of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nurses; AYA=Adolescent/Young Adult; B-ALL=B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CAR= chimeric-antigen receptor; CNS=Central nervous system; COG=Children’s Oncology Group; EBP=evidence-based practice; HSCT=hematopoietic stem cell transplant; HTS=High-throughput sequencing; MABs=Monoclonal antibodies; MATCH=Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice; MEK/ALK=mitogen-activated kinase/anaplastic lymphoma kinase; MIBG= meta-iodobenzylguanidine; MRD=Minimal residual disease; Ph=Philadelphia chromosome; ROR=return of results; US=United States

Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Subcommittee

The nursing Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) subcommittee was established to provide COG nurses with evidence-based recommendations to guide care provided to children enrolled on clinical trials. This subcommittee identifies high-priority clinical questions, performs systematic reviews of existing evidence based on these questions, and develops evidence-based summaries and recommendations to guide clinical practice.

The EBP subcommittee employs a competitive application process through which teams of nurses are selected to develop mentored EBP projects. Over the past decade, three EBP training workshops have been conducted; through this process, a cadre of COG nurses now have experience in the EBP process.7 EBP teams include one or two nurse leaders and additional team members, many with expertise other than nursing. After each new team is selected, nurses with EBP expertise provide guidance and mentorship for the team leaders who, in turn, guide and mentor members of their teams.

EBP teams each address a PICOT (Population, Intervention/Interest, Comparison, Outcome, Time) question8 identified by the COG Nursing leadership that focuses on a topic relevant to clinical trials nursing and to the discipline’s key aims. A comprehensive literature review is then conducted by the team to identify relevant evidence. The quality of evidence is evaluated by the team using the GRADE criteria9 for evidence summaries and the AGREE II criteria10 for clinical practice guidelines. Synthesis statements are then developed to summarize the findings and provide clinical recommendations, along with an overall appraisal of the quality and strength of the evidence.11

A wide variety of nursing care issues has been addressed by the COG nursing EBP process to date7,12–27 (Table 2). Additionally, the discipline’s EBP projects have been widely disseminated to pediatric oncology nurses through presentations at COG meetings, and through the COG educational track sessions at annual APHON meetings.

Table 2.

COG Nursing Discipline Evidence-Based Practice Projects: 2013–2023

| Topic | Training Aims | Funding | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIM: PATIENT-FAMILY EDUCATION | |||

| Recommendations for physical activity in mononephric childhood cancer survivors | Provision of mentoring in the systematic review process | U10CA098543 | Okada et al., 2016 |

| Systematic review of effective delivery of patient-family education | Mentored YI fellowship project | U10CA180886 R13CA196165 |

Rodgers et al., 2016 |

| Patient/family education regarding hypersensitivity reactions to PEG-asparaginase | Provision of mentoring in the systematic review process | U10CA180886 | Woods et al., 2017 |

| Development of a standardized checklist for delivery of new diagnosis education in pediatric oncology | Engaging direct care and advanced practices nurses in EBP | U10CA180886 | Rodgers et al., 2018 |

| Implementation and evaluation of a standardized new diagnosis education checklist in pediatric oncology | Mentored fellowship in EBP implementation | U10CA180886 | Duffy et al., 2021 |

| Evidence-based recommendations for education provided to families regarding the adverse events of ALK and MEK inhibitors | Mentored fellowship in EBP implementation | U10CA180886 | Fisher et al., in press, 2023 |

| AIM: ILLNESS-RELATED DISTRESS | |||

| Fertility preservation options for inclusion in protocols for pediatric and adolescent patients with cancer | Provision of mentoring in the systematic review process | U10CA098543 | Fernbach et al., 2014 |

| Hydration in children receiving intravenous cyclophosphamide | Provision of mentoring in the systematic review process | U10CA098543 | Robinson et al., 2014 |

| Prevention/management of post-lumbar headaches in patients receiving intrathecal chemotherapy | Provision of mentoring in the systematic review process | U10CA098543 Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation |

Rusch et al., 2014

|

| Nurse monitoring/management of hypersensitivity reactions to PEG-asparaginase | Provision of mentoring in the systematic review process | U10CA098543 | Woods et al., 2017 |

| Nephrotoxicity in patients receiving cisplatin therapy | Provision of mentoring in the systematic review process | U10CA180886 | Duffy et al., 2018 |

| Identification of validated tools for assessing peripheral neuropathy in pediatric oncology | Provision of mentoring in the systematic review process | U10CA180886 | Smolik et al., 2018 |

| Identification of interventions to promote adherence to oral medications in pediatric chronic illness | Provision of mentoring in the systematic review process | U10CA180886 | Coyne et al., 2019 |

| Identification of factors affecting the willingness of adolescents to communicate symptoms during cancer treatment | Provision of mentoring in the systematic review process | U10CA180886 | McLaughlin et al., 2019 |

| Evidence-based recommendations for the appropriate level of sedation to manage pain during procedures in pediatric oncology | Provision of mentoring in the systematic review process | U10CA180886 | Duffy et al., 2020 |

| Evidence-based recommendations for nurse monitoring and management of immunotherapy-induced cytokine release syndrome | Provision of mentoring in the systematic review process | U10CA180886 | Browne et al., 2021 |

| Commonly reported adverse events associated with pediatric immunotherapy | Provision of mentoring in the systematic review process | U10CA180886 | Withycombe et al., 2021 |

Abbreviation: ALK=anaplastic lymphoma kinase; EBP=Evidence-based practice; MEK= mitogen-activated kinase; PEG=Pegylated; YI=Young Investigator

Nursing Research Subcommittee

The nursing research subcommittee facilitates the development of research questions of high priority to pediatric oncology clinical trials nursing, and the exchange of ideas and expertise among nurse researchers. Research conducted within the discipline is guided by the Resilience in Individuals and Families Affected by Cancer organizing framework.28 This framework was developed from a positive health perspective and incorporates factors relevant to young people with cancer, their families and culture, including factors such as age, developmental level, environment, illness, and treatment.28

The majority of research conducted within the Nursing discipline intentionally incorporates opportunities for training and mentoring of young investigators (YI). Traineeship opportunities across the past decade, made possible through cooperative group infrastructure support grants (U10CA098543 and U10CA180886), have yielded opportunities for mentored and independent YI projects aligned with the discipline’s key aims.29–37 Additionally, valuable training opportunities supported through funding sources beyond the cooperative group have yielded outstanding opportunities for doctorally-prepared YI nurses, advanced practice nurses, and direct-care nurses to engage in scientific discovery.38–48 Findings from these projects have contributed to new knowledge generated by the work of the discipline (Table 3). To further support the work of YIs, the nursing discipline hosted a grant-writing workshop to invest in the future pipeline of investigators prepared to lead the discipline’s research. Many workshop attendees have gone on to secure institutional and federal funding for their research.

Table 3:

COG Nursing Discipline Research Studies: 2013–2023

| Topic | Training Aims | Funding | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIM: PATIENT-FAMILY EDUCATION | |||

| Understanding parental experience of receipt of new diagnosis education | Mentored YI original research project; Mentored YI fellowship project |

U10CA180886 R13CA196165 Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation |

Rodgers et al., 2016 Kelly et al., 2018 |

| Institutional patient/family educational practices across COG | Mentored YI fellowship project | U10CA180886 | Withycombe et al., 2016 |

| Critical content for inclusion in new diagnosis education | Mentored YI original research project | U10CA180886 | Haugen et al., 2016 |

| Expert consensus regarding effective delivery of new diagnosis education | N/A | U10CA180886 R13CA196165 |

Landier et al., 2016 |

| Developing COG smartphone application for parents of children with cancer | N/A | Kaul Pediatric Research Institute U10CA180886 St. Baldrick’s Foundation |

Landier et al., 2023 |

| AIM: ILLNESS-RELATED DISTRESS | |||

| Caregiver demands/parental well-being | N/A | U10CA098543 U10CA098413 U10CA095861 |

Kelly et al., 2014 |

| Resilience in AYA undergoing HSCT | Engaging direct care nurses in behavioral intervention research; Training/supporting nurses in the site PI role; Identifying strategies to support academic-clinical nurse collaborations |

R01NR008583 U10CA098543 U10CA095861 |

Robb et al., 2014

Docherty et al., 2013 Roll et al., 2013 Hendricks-Ferguson et al., 2017 Haase et al., 2020 |

| Weight change during ALL induction and obesity | Mentored YI traineeship | ACS119073- DSCN-10–090-01 U10CA098543 |

Withycombe et al., 2014 |

| Exercise and fatigue in AYA survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma | Mentored YI traineeship | U10CA098543 | Macpherson et al., 2015 |

| Parent psychophysiological outcomes in pediatric HSCT | Mentored YI original research project | U10CA098543 U10CA180886 |

Ward et al., 2017 |

| Self-care and communication intervention for parents of AYA undergoing high-risk cancer treatment | Engaging direct care and advanced practice nurses in behavioral intervention research | R01CA162181 U10CA098543 U10CA180886 UG1CA189955 U10CA098561 U10CA180899 |

Haase et al., 2021 |

| Symptom distress experienced by children receiving treatment for cancer on clinical trials | Mentored YI original research project | R13CA232442 U10CA180886 |

Skeens et al., 2019 |

| Expert consensus regarding symptom assessment during childhood cancer treatment | N/A | R13CA232442 U10CA180886 |

Withycombe et al., 2019 |

| Comparison of child self-report and parent proxy report of symptoms in children with advanced cancer | Mentored YI fellowship in multi-site clinical trial research | Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation | Montgomery et al., 2021 |

| Electronic symptom assessment in pediatric HSCT | Mentored YI fellowship in multi-site clinical trial research | Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation | Ward et al., 2020 |

| Pediatric education discharge support strategies | Engaging direct care nurses in research | American Nurses Credentialing Center |

Hockenberry et al., 2021

Patton et al., 2020 Haugen et al., 2020 |

| Fertility-related worry among AYA cancer survivors | YI original research project | K23NR020037 U10CA180886 |

Cherven, Lewis, et al., 2022 Cherven, Sampson, et al., 2022 |

| Delivery of care for pediatric patients receiving blinatumomab | Original research project | U10CA180886 | Withycombe et al., 2023 (manuscript in preparation) |

Abbreviations: COG=Children’s Oncology Group; YI=Young Investigator; N/A=Not applicable; HSCT=Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation; ALL=Acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AYA=Adolescent/Young Adult; ACS=American Cancer Society; DSCN=Doctoral Scholarship in Cancer Nursing; HSCT; Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation; N/A=Not Applicable; PI=Principal Investigator; YI=Young Investigator

COG nurses also conduct and lead research in collaboration with other COG disease and domain committees and investigators, including CCL49,50, young investigator51, outcomes/survivorship52, adolescent/young adult (AYA)53, acute lymphoblastic leukemia54–57, myeloid leukemia58, neuroblastoma59, and central nervous system tumor60,61 committees.

Important research milestones for the COG nursing discipline over the past decade include two state-of-the-science symposia – each centered on one of the two aims that are key foci for the discipline (patient/family education; illness-related distress). Each symposium was supported through the National Cancer Institute’s R13 mechanism (R13CA232442; R13CA196165), had findings featured in specially-themed issues of the Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing,16,31–33,35,62–68 and yielded expert consensus recommendations to guide further discipline research in these key areas.62,68

COG PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION RESOURCES

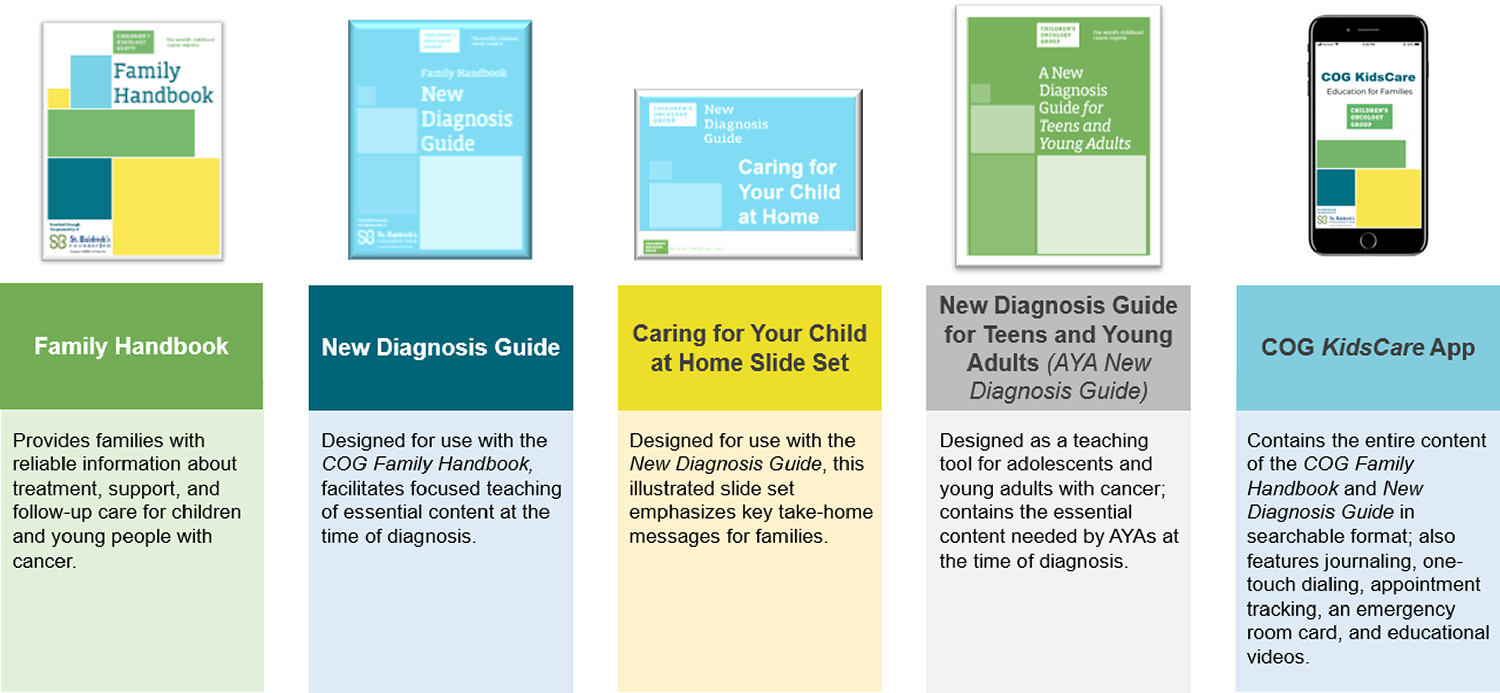

COG nursing is charged with the development and oversight of patient and family education resources within the cooperative group. This includes the Family Handbook,69 New Diagnosis Guide,70 New Diagnosis Slide Set: Caring for Your Child at Home,71 New Diagnosis Guide for Teens and Young Adults,72 and the COG KidsCare App73 (Figure 2). These resources are available in English, Spanish, and French (https://childrensoncologygroup.org/cog-family-handbook). The Patient and Family Education Member at Large is responsible for the oversight of these educational resources.

Figure 2. COG Patient/Family Education Resources.

Over the past decade, the COG Nursing Steering Committee has conducted extensive research in the area of patient and family education and has established best practices for provision of this education.14, 27, 39, 43, 57, 58 Use of the Family Handbook is the standard of care at many COG institutions where it is used in patient and family education at diagnosis, throughout treatment, and at the completion of therapy. Research conducted by the COG Nursing discipline found that families were often overwhelmed and experienced “information overload” at the time of a child’s cancer diagnosis.32,62 Based on these findings, the New Diagnosis Guide was developed to narrow the focus of education at initial diagnosis to key topics necessary for safe care of the child at home. Similarly, to guide new diagnosis education specific to the AYA population, the New Diagnosis Guide for Teens and Young Adults was developed. A multidisciplinary group within COG collaborated to develop this guide, which includes all information from the COG New Diagnosis Guide, and adds topics specific to the AYA population, including fertility, sexual intimacy, substance use, physical activity, driving safety, tattoos and body piercings, school, work and friendships, and resources for AYAs with cancer. The nursing discipline also developed a smartphone application, the COG KidsCare app. This app provides the entire content of the COG Family Handbook and New Diagnosis Guide in searchable format, and includes many features, such as journaling and appointment tracking, to promote user engagement and ongoing use throughout treatment and survivorship.73

In addition to the educational resources developed for families, the COG Nursing discipline also developed a checklist designed to guide pediatric oncology nurses in providing standardized new diagnosis education.17 To evaluate implementation of this checklist, an EBP fellowship was awarded to two doctorally-prepared nurses. The checklist was subsequently implemented at two COG institutions and found to be feasible and acceptable in the clinical setting.8 This project also yielded a standardized educational program for use by nurses to facilitate the provision of new diagnosis education. This program, developed as a PowerPoint© slide set, was later expanded into the COG New Diagnosis Slide Set: Caring for your Child at Home71 and made available to all COG nurses.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The COG Nursing committee, established 20 years ago, continues to adapt to meet the overarching goals of the nursing discipline and to support the COG mission. Expert pediatric oncology nurses are essential to the success of COG clinical trials, and the looming nursing shortage will undoubtedly influence future directions of the discipline. To confront this challenge, the COG nursing leadership will prioritize the retention of expert clinical trials nurses, as well as recruitment and development of new pediatric oncology clinical trials nurses. This can be accomplished by sustaining the Nursing committee structure and efforts, and through increasing opportunities for meaningful engagement of nurses within COG. The COG Nursing discipline must also be nimble and quickly adjust to the rapidly evolving scientific discoveries in the field. Over the next decade, there will be a clear focus on both sustainability and innovation, as the nursing committee tackles future challenges and opportunities.

Sustainability

The current structure of the Nursing committee provides opportunities for engagement that reflect the broad interests and expertise of the Nursing discipline membership. Provision of clinical trials training and education will remain a priority of the Nursing discipline, including educational outreach to the broader pediatric oncology nursing community. The Nursing committee will continue to partner with APHON, including the annual COG educational track, and will maintain an online platform to house educational sessions for nurses. Efforts to provide CE offerings will also continue. Many patient and family resources have been developed this past decade; sustaining availability and assuring timeliness of these resources will remain a priority. COG nurse representation on disease and domain committees, and on COG administrative committees should be maintained. Mentorship of nurses within COG has been a strength of the past decade and the efforts to sustain continued mentorship will be an important strategy for the future.

Innovation

Increasing opportunity, awareness, and access to pediatric oncology clinical trials education and training for nurses through innovation will be a future priority. This vision will need to reflect the anticipated nursing shortages but also be representative of the varied ways in which nurses prefer to learn. Harnessing technology to both market and provide education will be explored. This will include hybrid formats for nursing educational sessions at annual COG meetings, and the introduction of quarterly COG nursing webinars. Providing opportunities for nurses to learn with minimal interruption to clinical responsibilities is an important consideration. Collaboration with other COG disciplines to provide inter-professional education with available CE is another opportunity to expand access to educational opportunities. Leveraging social media to increase awareness of and provide educational offerings can also increase pediatric oncology nursing reach and engagement.

In light of the increasing complexities of clinical trials, opportunities for nurses to share lessons learned when caring for patients, and a focus on avoiding redundant efforts will be explored. This will include further development of FAQ documents to enhance protocol materials and support efficient trials operations including site activation. Research to understand variations in nursing clinical practice related to new and complex cancer therapies will be developed and undertaken with the aim of improving standardization and determining best practices related to the care of patients enrolled on COG clinical trials.

Efforts focused on implementing evidence into practice is required to positively influence the care of patients on COG clinical trials. While the work of the EBP subcommittee to date has been successful in providing mentorship to COG nurses in the EBP process, the future of EBP must consider knowledge translation and assess both successes and barriers to implementation. Using evidence to inform the care of patients and families fosters opportunities to improve outcomes.

The future of patient and family education resources within COG must include a process for review focused on refining and updating content. Attention to the availability of formats for the resources (e.g., print, electronic), and for additional languages and the development of materials tailored to literacy/health literacy levels of families and reflective of community and culture will require careful consideration. The COG Nursing committee will need to develop a strategy for sustaining these resources and informing development of additional resources as the field of pediatric oncology continues to evolve. Research focused on understanding effective implementation of COG’s patient and family educational resources remains an important goal.

Over the next decade, the research focus of the Nursing discipline will shift, with more emphasis placed on reducing illness-related distress. This will include two priority areas: i) development of aims driven by patient-reported outcomes (PROs) within COG clinical trials and ii) development of interventions to mitigate or manage distressing symptoms and toxicities of pediatric cancer therapy. Beyond this priority area, COG nurses have wide-ranging scientific interests that involve or are led by other COG committees, requiring collaboration. For example, COG nurses are involved in ongoing efforts aimed at understanding and addressing health disparities and improving diversity in COG trials. Developing PRO aims within COG clinical trials, although directly tied to the nursing research priority of reducing illness-related distress, also requires collaboration across COG. A working group within the CCL PRO subcommittee, co-led by nursing, behavioral science, and hematology/oncology, is focused on the successful development of PRO aims within COG clinical trials. An important priority of this PRO working group is to ensure representation across disciplines in the future development of PRO aims. Building on the success of the recent COG AYA PRO pilot,74 the working group is currently developing a proposal for inclusion of PRO aims for children under age 15 enrolled on COG clinical trials. This proposal includes establishment and validation of a battery of PROs for children that reflects the population, but also flexible, allowing for multiple raters due to the young age of many patients. Equally important, this initiative will also provide increased opportunity to build infrastructure and expertise within COG related to PRO aims. Involvement of YIs within PRO aims is an added priority of this working group.

CONCLUSION

Much has been accomplished by the COG Nursing discipline over the past decade, including ongoing support of COG clinical trials through nursing participation on COG steering and protocol committees, the provision of high-quality clinical trials education to the pediatric oncology nursing community, publication of a wide array of systematic reviews on topics of clinical importance to the discipline, and conduct of research that has informed the development of a rich assortment of patient/family educational resources. Looking to the future, the Nursing discipline will continue to support COG clinical trials through a multifaceted approach, with a particular focus on patient-reported outcomes, development of interventions to better understand and address illness-related distress in children and AYAs with cancer, and to ensure equity and inclusion in all aspects of care.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following individuals for their significant contributions to the strategic planning process for developing this Blueprint for the COG Nursing Discipline: Joy Bartholomew, Ashlee Blumhoff, Elizabeth Duffy, Maureen Haugen, Marilyn Hockenberry, Casey Hooke, Carol Kotsubo, Peggy Kulm, Marcia Leonard, Jeneane Miller, Denise Mills, Cheryl Rodgers, Kathy Ruccione, Micah Skeens, Katy Tomlinson, Janice Withycombe, and Christine Yun.

Funding:

This research was funded by the Children’s Oncology Group NCTN Network Group Operations Grant (U10CA180886).

Abbreviation Key:

- AGREE

Appraisal of Guidelines and Research and Evaluation

- ALL

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- APHON

Association of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nurses

- AYA(s)

Adolescent/adolescence and young adult(s)

- CCL

Cancer Control

- CE

continuing education

- COG

Children’s Oncology Group

- CTS

Clinical Trial Summaries

- DCN(s)

Disease Committee Nurse(s)

- EBP

Evidence-Based Practice

- FAQ(s)

Frequently asked question(s)

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations

- PICOT

Population, Intervention/Interest, Comparison, Outcome, Time

- PROs

patient-reported outcomes

- ROR

Return of Results

- YI(s)

young investigator(s)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests: None

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and is not intended to represent the views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Withycombe JS, Alonzo TA, Wilkins-Sanchez MA, Hetherington M, Adamson PC, Landier W. The Children’s Oncology Group: Organizational Structure, Membership, and Institutional Characteristics. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jan/Feb 2019;36(1):24–34. doi: 10.1177/1043454218810141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landier W, Leonard M, Ruccione KS. Children’s Oncology Group’s 2013 blueprint for research: nursing discipline. Pediatr Blood Cancer. Jun 2013;60(6):1031–6. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zupanec S, Withycombe J. Using shared experience to define optimal care for patients receiving blinatumomab on COG clinical trials. 17 Sep 2022 Association of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nurses 46th Annual Conference (Session C228) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez CV, Ruccione K, Wells RJ, et al. Recommendations for the return of research results to study participants and guardians: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. Dec 20 2012;30(36):4573–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haugen M, Kelly KP, Leonard M, et al. Nurse-Led Programs to Facilitate Enrollment to Children’s Oncology Group Cancer Control Trials. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs Sep 2016;33(5):387–91. doi: 10.1177/1043454215617458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haugen M, Gasber E, Leonard M, Landier W. Harnessing technology to enhance delivery of clinical trials education for nurses: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Mar-Apr 2015;32(2):96–102. doi: 10.1177/1043454214564189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodgers C, Withycombe JS, Hockenberry MJ. Evidence-Based Practice Projects in Pediatric Oncology Nursing. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs Jul 2014;31(4):182–184. doi: 10.1177/1043454214532023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, Stillwell SB, Williamson KM. Evidence-based practice: step by step: the seven steps of evidence-based practice. Am J Nurs. Jan 2010;110(1):51–3. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000366056.06605.d2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. Apr 2011;64(4):383–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burgers JS, Fervers B, Haugh M, et al. International assessment of the quality of clinical practice guidelines in oncology using the Appraisal of Guidelines and Research and Evaluation Instrument. J Clin Oncol. May 15 2004;22(10):2000–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. Jul 2013;66(7):719–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernbach A, Lockart B, Armus CL, et al. Evidence-Based Recommendations for Fertility Preservation Options for Inclusion in Treatment Protocols for Pediatric and Adolescent Patients Diagnosed With Cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jul 2014;31(4):211–222. doi: 10.1177/1043454214532025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson D, Schulz G, Langley R, Donze K, Winchester K, Rodgers C. Evidence-Based Practice Recommendations for Hydration in Children and Adolescents With Cancer Receiving Intravenous Cyclophosphamide. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs Jul 2014;31(4):191–199. doi: 10.1177/1043454214532024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rusch R, Schulta C, Hughes L, Withycombe JS. Evidence-Based Practice Recommendations to Prevent/Manage Post-Lumbar Puncture Headaches in Pediatric Patients Receiving Intrathecal Chemotherapy. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jul 2014;31(4):230–238. doi: 10.1177/1043454214532026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okada M, Hockenberry MJ, Koh CJ, et al. Reconsidering Physical Activity Restrictions for Mononephric Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jul 2016;33(4):306–13. doi: 10.1177/1043454215607341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodgers CC, Laing CM, Herring RA, et al. Understanding Effective Delivery of Patient and Family Education in Pediatric Oncology(A Systematic Review From the Children’s Oncology Group [Formula: see text]). J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Nov/Dec 2016;33(6):432–446. doi: 10.1177/1043454216659449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woods D, Winchester K, Towerman A, et al. From the Children’s Oncology Group: Evidence-Based Recommendations for PEG-Asparaginase Nurse Monitoring, Hypersensitivity Reaction Management, and Patient/Family Education. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Nov/Dec 2017;34(6):387–396. doi: 10.1177/1043454217713455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffy EA, Fitzgerald W, Boyle K, Rohatgi R. Nephrotoxicity: Evidence in Patients Receiving Cisplatin Therapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. Apr 1 2018;22(2):175–183. doi: 10.1188/18.CJON.175-183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodgers C, Bertini V, Conway MA, et al. A Standardized Education Checklist for Parents of Children Newly Diagnosed With Cancer: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jul/Aug 2018;35(4):235–246. doi: 10.1177/1043454218764889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smolik S, Arland L, Hensley MA, et al. Assessment Tools for Peripheral Neuropathy in Pediatric Oncology: A Systematic Review From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jul/Aug 2018;35(4):267–275. doi: 10.1177/1043454218762705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coyne KD, Trimble KA, Lloyd A, et al. Interventions to Promote Oral Medication Adherence in the Pediatric Chronic Illness Population: A Systematic Review From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. May/Jun 2019;36(3):219–235. doi: 10.1177/1043454219835451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLaughlin CA, Gordon K, Hoag J, et al. Factors Affecting Adolescents’ Willingness to Communicate Symptoms During Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. Apr 2019;8(2):105–113. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2018.0111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duffy EA, Adams T, Thornton CP, Fisher B, Misasi J, McCollum S. Evidence-Based Recommendations for the Appropriate Level of Sedation to Manage Pain in Pediatric Oncology Patients Requiring Procedures: A Systematic Review From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jan/Feb 2020;37(1):6–20. doi: 10.1177/1043454219858610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Browne EK, Daut E, Hente M, Turner K, Waters K, Duffy EA. Evidence-Based Recommendations for Nurse Monitoring and Management of Immunotherapy-Induced Cytokine Release Syndrome: A Systematic Review from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Nov-Dec 2021;38(6):399–409. doi: 10.1177/10434542211040203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duffy EA, Herriage T, Ranney L, Tena N. Implementing and Evaluating a Standardized New Diagnosis Education Checklist: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Sep-Oct 2021;38(5):322–330. doi: 10.1177/10434542211011059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Withycombe JS, Carlson A, Coleman C, et al. Commonly Reported Adverse Events Associated With Pediatric Immunotherapy: A Systematic Review From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jan/Feb 2021;38(1):16–25. doi: 10.1177/1043454220966590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher B, Meyer A, Brown A, et al. Evidence-Based Recommendations for Education Provided to Patients and Families Regarding the Adverse Events of ALK and MEK Inhibitors: A Systematic Review from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol Nurs. 2023; in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly KP, Hooke MC, Ruccione K, Landier W, Haase J. Children’s Oncology Group nursing research framework. Semin Oncol Nurs Feb 2014;30(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macpherson CF, Hooke MC, Friedman DL, et al. Exercise and Fatigue in Adolescent and Young Adult Survivors of Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. Sep 2015;4(3):137–40. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2015.0013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Withycombe JS, Smith LM, Meza JL, et al. Weight change during childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia induction therapy predicts obesity: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. Mar 2015;62(3):434–9. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haugen MS, Landier W, Mandrell BN, et al. Educating Families of Children Newly Diagnosed With Cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Nov/Dec 2016;33(6):405–413. doi: 10.1177/1043454216652856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodgers CC, Stegenga K, Withycombe JS, Sachse K, Kelly KP. Processing Information After a Child’s Cancer Diagnosis-How Parents Learn. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Nov/Dec 2016;33(6):447–459. doi: 10.1177/1043454216668825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Withycombe JS, Andam-Mejia R, Dwyer A, Slaven A, Windt K, Landier W. A Comprehensive Survey of Institutional Patient/Family Educational Practices for Newly Diagnosed Pediatric Oncology Patients. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Nov/Dec 2016;33(6):414–421. doi: 10.1177/1043454216652857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward J, Swanson B, Fogg L, Rodgers C. Pilot Study of Parent Psychophysiologic Outcomes in Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Cancer Nurs. May/Jun 2017;40(3):E48–E57. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skeens MA, Cullen P, Stanek J, Hockenberry M. Perspectives of Childhood Cancer Symptom-Related Distress: Results of the State of the Science Survey. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jul/Aug 2019;36(4):287–293. doi: 10.1177/1043454219858608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cherven B, Kelling E, Lewis RW, Pruett M, Meacham L, Klosky JL. Fertility-related worry among emerging adult cancer survivors. J Assist Reprod Genet. Nov 30 2022;doi: 10.1007/s10815-022-02663-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cherven B, Lewis RW, Pruett M, Meacham L, Klosky JL. Interest in fertility status assessment among young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer Med. Jun 1 2022;doi: 10.1002/cam4.4887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Docherty SL, Robb SL, Phillips-Salimi C, et al. Parental perspectives on a behavioral health music intervention for adolescent/young adult resilience during cancer treatment: report from the children’s oncology group. J Adolesc Health. Feb 2013;52(2):170–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roll L, Stegenga K, Hendricks-Ferguson V, et al. Engaging nurses in research for a randomized clinical trial of a behavioral health intervention. Nurs Res Pract. 2013;2013:183984. doi: 10.1155/2013/183984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robb SL, Burns DS, Stegenga KA, et al. Randomized clinical trial of therapeutic music video intervention for resilience outcomes in adolescents/young adults undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. Mar 15 2014;120(6):909–17. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hendricks-Ferguson VL, Barnes YJ, Cherven B, et al. Stories and Music for Adolescent/Young Adult Resilience During Transplant Partnerships: Strategies to Support Academic-Clinical Nurse Collaborations in Behavioral Intervention Studies. Clin Nurse Spec. Jul/Aug 2017;31(4):195–200. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haase JE, Robb SL, Burns DS, et al. Adolescent/Young Adult Perspectives of a Therapeutic Music Video Intervention to Improve Resilience During Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant for Cancer. J Music Ther. Feb 25 2020;57(1):3–33. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thz014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haugen M, Skeens M, Hancock D, Ureda T, Arthur M, Hockenberry M. Implementing a pediatric oncology nursing multisite trial. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. Jul 2020;25(3):e12293. doi: 10.1111/jspn.12293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patton L, Montgomery K, Coyne K, Slaven A, Arthur M, Hockenberry M. Promoting Direct Care Nurse Engagement in Research in Magnet Hospitals: The Parent Education Discharge Support Strategies Experience. J Nurs Adm. May 2020;50(5):287–292. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ward JA, Balian C, Gilger E, Raybin JL, Li Z, Montgomery KE. Electronic Symptom Assessment in Children and Adolescents With Advanced Cancer Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jul/Aug 2020;37(4):255–264. doi: 10.1177/1043454220917686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haase JE, Stegenga K, Robb SL, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of a Self-care and Communication Intervention for Parents of Adolescent/Young Adults Undergoing High-Risk Cancer Treatment: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer Nurs. Nov 23 2021;doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000001038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hockenberry M, Haugen M, Slaven A, et al. Pediatric Education Discharge Support Strategies for Newly Diagnosed Children With Cancer. Cancer Nurs. Nov-Dec 01 2021;44(6):E520–E530. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montgomery KE, Vos K, Raybin JL, et al. Comparison of child self-report and parent proxy-report of symptoms: Results from a longitudinal symptom assessment study of children with advanced cancer. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. Jul 2021;26(3):e12316. doi: 10.1111/jspn.12316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sugalski AJ, Lo T, Beauchemin M, et al. Facilitators and barriers to clinical practice guideline-consistent supportive care at pediatric oncology institutions: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Implement Sci Commun. Sep 16 2021;2(1):106. doi: 10.1186/s43058-021-00200-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beauchemin M, Santacroce SJ, Bona K, et al. Rationale and design of Children’s Oncology Group (COG) study ACCL20N1CD: financial distress during treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the United States. BMC Health Serv Res. Jun 28 2022;22(1):832. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08201-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levy AS, Pyke-Grimm KA, Lee DA, et al. Mentoring in pediatric oncology: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group Young Investigator Committee. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. Aug 2013;35(6):456–61. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31829eec33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hudson MM, Bhatia S, Casillas J, et al. Long-term Follow-up Care for Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Pediatrics Sep 2021;148(3)doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-053127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cherven B, Sampson A, Bober SL, et al. Sexual health among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: A scoping review from the Children’s Oncology Group Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Discipline Committee. CA Cancer J Clin. May 2021;71(3):250–263. doi: 10.3322/caac.21655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Landier W, Chen Y, Hageman L, et al. Comparison of self-report and electronic monitoring of 6MP intake in childhood ALL: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Blood. Apr 6 2017;129(14):1919–1926. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-07-726893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Landier W, Hageman L, Chen Y, et al. Mercaptopurine Ingestion Habits, Red Cell Thioguanine Nucleotide Levels, and Relapse Risk in Children With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group Study AALL03N1. J Clin Oncol. May 20 2017;35(15):1730–1736. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.7579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thompson J EC, Withycombe J, Kairalla J, Wang C, Zupanec S, Gupta S, Rau R, Rabin K, Loh M, Raetz E, Alexander S, Miller T. Risk of spesis during blinatumomab administration: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology 2023 Paper and Poster Abstracts. Pediatr Blood Cancer. Jun 2023;70(S3):e30390; Abstrract #2016. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Withycombe J, Kubaney HR, Okada M, et al. Delivery of Care for Pediatric Patients Receiving Blinatumomab: A Children’s Oncology Group Study. 2023; (Manuscript in preparation) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnston DL, Nagarajan R, Caparas M, et al. Reasons for non-completion of health related quality of life evaluations in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. PloS one. 2013;8(9):e74549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Landier W, Knight K, Wong FL, et al. Ototoxicity in children with high-risk neuroblastoma: prevalence, risk factors, and concordance of grading scales--a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. Feb 20 2014;32(6):527–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.2038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schulte F, Russell KB, Cullen P, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of health-related quality of life in pediatric CNS tumor survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. Aug 2017;64(8)doi: 10.1002/pbc.26442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Michalski JM, Janss AJ, Vezina LG, et al. Children’s Oncology Group Phase III Trial of Reduced-Dose and Reduced-Volume Radiotherapy With Chemotherapy for Newly Diagnosed Average-Risk Medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. Aug 20 2021;39(24):2685–2697. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Landier W, Ahern J, Barakat LP, et al. Patient/Family Education for Newly Diagnosed Pediatric Oncology Patients. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Nov/Dec 2016;33(6):422–431. doi: 10.1177/1043454216655983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hockenberry M, Landier W. Patient/Family Education as Translational Science in Pediatric Oncology. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. May/Jun 2017;34(3):155. doi: 10.1177/1043454216680738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hockenberry M, Landier W. Symptom Assessment During Childhood Cancer Treatment. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jul/Aug 2019;36(4):242–243. doi: 10.1177/1043454219852611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hooke MC, Linder LA. Symptoms in Children Receiving Treatment for Cancer-Part I: Fatigue, Sleep Disturbance, and Nausea/Vomiting. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jul/Aug 2019;36(4):244–261. doi: 10.1177/1043454219849576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Linder LA, Hooke MC. Symptoms in Children Receiving Treatment for Cancer-Part II: Pain, Sadness, and Symptom Clusters. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jul/Aug 2019;36(4):262–279. doi: 10.1177/1043454219849578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mandrell BN, Withycombe JS. Symptom Biomarkers for Children Receiving Treatment for Cancer: State of the Science. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jul/Aug 2019;36(4):280–286. doi: 10.1177/1043454219859233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Withycombe JS, Haugen M, Zupanec S, Macpherson CF, Landier W. Consensus Recommendations From the Children’s Oncology Group Nursing Discipline’s State of the Science Symposium: Symptom Assessment During Childhood Cancer Treatment. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. Jul/Aug 2019;36(4):294–299. doi: 10.1177/1043454219854983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murphy K, ed. The Children’s Oncology Group Family Handbook, 2nd Ed. Children’s Oncology Group, https://childrensoncologygroup.org/downloads/English_COG_Family_Handbook.pdf; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sullivan J, Tomlinson K, eds. The Children’s Oncology Group Family Handbook New Diagnosis Guide. Children’s Oncology Group, https://childrensoncologygroup.org/downloads/329120-SBF-New_Diagnosis_English.pdf; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sullivan J, Duffy EA, Herriage T, Ranney L, Tena N, eds. The Children’s Oncology Group New Diagnosis Guide: Caring for Your Child at Home. Children’s Oncology Group, https://childrensoncologygroup.org/downloads/Diagnosis_Guide_Slide_Set_English.pptx; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Herriage T, Miller JS, eds. Children’s Oncology Group Family Handbook: A New Diagnosis Guide for Teens and Young Adults. Children’s Oncology Group, https://childrensoncologygroup.org/downloads/COG_AYA_Guide_English.pdf; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Landier W, Campos Gonzalez PD, Henneberg H, et al. Children’s Oncology Group KidsCare smartphone application for parents of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. Mar 21 2023:e30288. doi: 10.1002/pbc.30288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roth ME, Parsons SK, Ganz PA, et al. Inclusion of a core patient-reported outcomes battery in adolescent and young adult cancer clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. Jan 10 2023;115(1):21–28. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djac166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]