Abstract

This study investigates associations between (a) relationship satisfaction and intimate partner violence (IPV: psychological, physical, and sexual) and (b) observed couples communication behavior. Mixed-sex couples (N=291) were recruited via random digit dialing. Partners completed the Quality of Marriage Index (Norton, 1983), the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus et al., 1996), and one female-initiated and one male-initiated 10-min conflict conversations. Discussions were coded with Rapid Marital Interaction Coding System, 2nd Generation (Heyman et al., 2015). As hypothesized, lower satisfaction was associated with more hostility (p =.018) and less positivity (p < 0.001); more extensive IPV was associated with more hostility (p < 0.001). For negative reciprocity, there was a dissatisfaction × IPV extent × conversation-initiator interaction (p < 0.006). Results showed that conflict behaviors of mixed-sex couples are related to the interplay among gender, satisfaction, and the severity of couple-level IPV. Theoretical and clinical implications are discussed.

Keywords: couple communication, Dyadic Relationship/Quality/Satisfaction, intimate partner violence, observation, Domestic Abuse/Violence

Although rarely acknowledged, the study of relationship distress1 is largely the study of clinically dissatisfied couples with co-occurring physical intimate partner violence (IPV). Indeed, eight samples of those presenting for couples therapy reported prevalences of 51–67% for physical IPV in the past year, and similar levels are found for distressed couples in community samples (Heyman et al., in press). Similarly, the study of physical IPV — at least in community samples of established (i.e., cohabiting or married) relationships — is largely the study of couples with physical IPV sporadically occurring amid chronic relationship distress (Johnson, 2006). This study aims to investigate associations between (a) relationship satisfaction and IPV (comprising psychological, physical, and sexual acts) and (b) communication, “the common pathway to relationship dysfunction across theories, therapies, therapists, and clients. All theories and therapies emphasize the role of communication… and both therapists … and couples … rate communication as the top problem area” (Heyman, 2001, p. 6). Communication’s primacy in interpersonal relationships — as the means for individuals to get what they want and to express and respond to anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise — makes it the Rosetta Stone of relationship constructs.

Both distress and IPV are prevalent. About 1 in 3 marriages are distressed (Whisman et al., 2008) with about the same prevalence for lifetime experience of both psychological and physical IPV (Smith et al., 2018). The public health burden of these problems and their sequelae are tremendous (Foran et al., 2013). Studies of the antecedents of physical IPV have found communication and problem-solving disputes (and the accompanying emotionality in these disputes) to be the most common proximal precipitants (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., 2012; O’Leary & Slep, 2006). Observed couples’ conflict communication (without regard to IPV) has been the focus of several hundred studies. Among the most replicated, robust findings are that, distressed, compared with non-distressed, couples trying to resolve problems (a) are more hostile, (b) are more likely to reciprocate and escalate their partners’ hostility, and (c) emit less positive behavior (Heyman, 2001).

Observational communication research of mixed-sex couples was extended in the late 1980s to compare distressed couples with male-to-female physical IPV (D+/IPV+), distressed couples without male-to-female physical IPV (D+/IPV-), and non-distressed couples without male-to-female physical IPV (D-/IPV- couples). The results are challenging to summarize (even within multiple publications from the same data set) because of (a) small group sizes (sometimes as few as n=13), leading to varying power to detect differences among studies; and (b) widely divergent operationalizations in constituting both the D+/IPV+ group and the contrasting D+/IPV- and D-/IPV- groups. Nevertheless, three important findings emerged.

First, D+/IPV+, compared with D+/IPV-, partners emit more negative behaviors (e.g., anger, belligerence, contempt; Burman et al., 1993; Cordova et al., 1993; Friend et al., 2017; Gordis et al., 2005; Jacobson et al., 1994; Margolin et al., 1988; Sommer et al., 2019). There have been notable exceptions: Waltz et al. (2000) found no differences, and Margolin et al. (1988) found differences for men but not women. In stark contrast, Friend et al. (2017) found that men and women in D+/IPV-, compared with D+/IPV+, relationships exhibited more belligerence.

Second, D+/IPV+, compared with D+/IPV-, partners emit fewer positive behaviors (Burman et al., 1993). However, Friend et al., 2017 found this for humor only and found the opposite for affection and interest, with D+/IPV+ partners emitting more than D+/IPV- partners. Gordis et al. (2005) did not classify couples on relationship distress but found IPV+, compared with IPV-, partners emitted less positive and neutral behaviors.

Third, negative reciprocity sequences (hostilityhostility; Patterson, 1982) were found more often in D+/IPV+ than in D+/IPV- couples (Burman et al. 1993; Coan et al., 1997; Cordova et al., 1993; Margolin et al., 1988).

The pattern of results is semi-coherent for several reasons. First, there is undoubtedly some true effect despite the middling signal/noise ratio. Multiple studies found that IPV+ couples act more hostilely and reciprocate and escalate hostility; tellingly, Gordis et al. (2005) also found that when, over time, couples desist IPV, they desist behaving like IPV+ couples. Second, the noise seems to be amplified by different investigators’ myriad grouping/contrasting strategies. The majority of these studies were published during a time of exceptional foment in the IPV field, with controversies raging about the meaning of bidirectional violence and whether IPV was a unitary phenomenon characterized by men’s use of IPV to exert power and control over women (Gelles & Loseke, 1993). Since then, typologies by Johnson (e.g., 1995; 2006) and Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) have garnered support that the predominant form of IPV in community samples (89% in Johnson, 2006) are couples who do not approve of IPV and for whom IPV tends to be bidirectional and less severe. Johnson (2006) has termed this type “Situational Couple Violence” (SCV). Most of the studies cited above studied SCV in couples with predominantly mild physical IPV (but with nearly all reporting at least one “severe” act, such as hitting). However, several studies (e.g., Cordova et al., 1993; Jacobson et al., 1994; Waltz, 2000) used criteria that likely recruited some couples from the SCV group but many from the group that Johnson (2006) terms “Intimate Terrorism” and the groups that Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) term “antisocial” and “borderline/dysphoric.”

If, as Johnson (1995, 2006) proposes, SCV IPV+ couples are drawn from the same population as IPV- couples, then considerable noise has been introduced by dividing couples into separate groups based on (a) error-laden classifications of distress (i.e., thresholds of questionable validity, measurement not taking into account confidence intervals, unified couples’ classification despite partners’ disparate satisfaction levels) and (b) myriad inclusion criteria for IPV+ that focus solely on physical IPV. This group-based classification of couples on variables (satisfaction and IPV) that are actually continuous in intensity obfuscates the effect sizes of the main effects and interactions implicit in creating such groups.

This paper is the first to attempt to delineate and disentangle the effects of satisfaction, IPV (psychological, physical, and sexual), and their interactions on observed communication behaviors. (Note that Shortt et al., 2010 studied the effects of (a) IPV, observed communication, and their interaction on (b) satisfaction; IPV x observed negative behavior predicted lower satisfaction five years later in emerging adult couples).

Cognitive-behavioral theories of IPV (e.g., Bell & Naugle, 2008; Finkel, 2008) theorize that acts occur during escalating coercive interactions in the context of fairly stable contextual factors (e.g., distress, learning history of coercion). Finkel’s (2008) I3 (Instigation, Impellance, Inhibition) model labels these contextual factors as “impellance” variables that can individually and interactively increase the likelihood of aggressive behavior (including observed hostility). First, we hypothesized main effects for satisfaction and coercive learning history (as indexed by the extent of past-year IPV) predicting the classic observed-conflict triad (i.e., more hostility, more reciprocation of hostility, less positivity; Heyman, 2001). Second, using I3 theory, we further hypothesized that lower satisfaction will magnify the perceived intensity of verbal instigations (Sanford, 2006), which, in the presence of IPV history, will be associated with the observed-conflict triad. Thus, we hypothesized a two-way interaction (satisfaction × IPV-extent) predicting the conflict triad outcomes.

Finally, two studies of distress and IPV (Holtzworth-Munroe et al., 1998; Noller & Roberts, 2002) found that observed behaviors of both partners differed depending on which partner was pursuing change, extending prior research that had not considered IPV (Christensen & Heavey, 1990; Heavey et al., 1995). Thus, we collected interactions with both men and women bringing up one of their top areas of change so that initiator differences on observed behavior could be tested.

To summarize, to disentangle the heretofore confounded impacts of variable levels of IPV and satisfaction, we used cognitive behavioral theories to hypothesize that (a) lower relationship satisfaction, (b) higher IPV extent (i.e., an ordinal scale ranging from none to injurious), and (c) their interactions would be associated with the observed-conflict triad of elevated hostility, negative reciprocity, and lower positivity. We did not hypothesize effects for gender or conversation initiator but will check whether these contextual factors significantly influence behavior.

Method

All study procedures were approved by the university institutional review board.

Participants

Participants were 291 English-speaking, mixed-sex couples (582 individuals) who were married (n = 262; 90%) or living together for at least one year (n = 29; 10%). Couples were recruited from a representative sampling frame of Suffolk County, New York using random digit dialing. A total of 229,106 phone numbers were dialed by research assistants who ultimately reached 12,009 individuals that answered at least one question in the interview. Respondents were screened via the telephone interview; n=2,212 completed interviews and met eligibility requirements. Of these respondents, 291 ultimately participated in the study and received $250 for completing the 4-hour lab protocol. Participants in the phone survey were found to be fairly representative of the county population (via the 2000 U.S. Census), and study participants were quite representative of couples who were eligible but did not participate in the main study (for detailed information see Slep et al., 2006).

To be invited to participate in the laboratory study, a phone respondent had to report that (a) he or she was married or cohabiting for at least one year and (b) report that both the respondent and the partner could understand and read English. To ensure broad distribution of both relationship satisfaction and IPV, we oversampled couples reporting IPV in the last year and those who reported relationship distress without IPV. Demographics and descriptive statistics for main study variables can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Variable | M | SD | % | M | SD | % |

| Age | 42.40 | 10.76 | - | 40.55 | 10.07 | - |

| Years of Education | 14.24 | 2.51 | - | 14.42 | 2.37 | - |

| Family Income (US$)* | - | - | - | 84,194 | 47,158 | - |

| Length of Relationship (Years)* | - | - | - | 12.88 | 10.97 | - |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Black or African American | - | - | 6.8 | - | - | 6.8 |

| Asian | - | - | 1.7 | - | - | 1.0 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | - | - | 2.1 | - | - | 0.0 |

| Hispanic or Latino/a (of any race) | - | - | 5.5 | - | - | 4.8 |

| White (Non-Hispanic or Latino/a) | - | - | 79.7 | - | - | 84.2 |

| Multiracial | - | - | 4.1 | - | - | 3.1 |

| Relationship Satisfaction | 31.41 | 9.95 | - | 30.07 | 11.67 | - |

| IPV Extent* | 5.29 | 2.97 | - | - | - | - |

| Female-Initiated Conversation | ||||||

| Combined Hostility Codes | 17.10 | 19.61 | - | 31.37 | 27.39 | - |

| Neutral (Constructive Problem Discussion) | 60.57 | 21.72 | - | 54.23 | 22.10 | - |

| Combined Positive Codes | 8.29 | 7.57 | - | 8.56 | 8.14 | - |

| Male-Initiated Conversation | ||||||

| Combined Hostility Codes | 19.69 | 19.93 | - | 21.28 | 24.98 | - |

| Neutral (Constructive Problem Discussion) | 59.90 | 20.64 | - | 54.23 | 21.09 | - |

| Combined Positive Codes | 8.71 | 8.71 | - | 10.27 | 9.76 | - |

Couple-level variable

Measures

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

Extent of couple physical, psychological, and sexual IPV.

The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) is the most widely used measure of IPV, with established reliability and validity (e.g., Archer, 2000; Newton et al., 2001; Straus, 2004). Participants indicated the frequency that they (i.e., perpetration) and their partners (i.e., victimization) engaged in specific acts during the preceding 12 months on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times). Using Straus et al.’s (1996) classifications, mild psychological IPV comprised the following items: insulted or sworn at, shouted or yelled, and done something to spite partner. Severe psychological IPV comprised the following items: called partner fat or ugly, destroyed something belonging to partner, accused partner of being a lousy lover, and threatened to hit or throw something. Mild physical IPV was assessed with the following items: threw an object that could hurt; twisted arm or hair; pushed or shoved; grabbed; and slapped. Severe physical or sexual IPV comprised the following items: beat up; burned or scalded on purpose; kicked; slammed against a wall; choked; punched or hit with an object that could hurt; used a knife or gun; used force to make your partner have sex. IPV impact/injury comprised two items: broken a bone or passed out from being hit on the head by your partner during a fight; and gone, or needed to (but didn’t) go, to the doctor because of a fight with your partner. As is typically done when data from both partners are available (e.g., Heyman & Schlee, 1997; Schafer et al., 2002), if partners differed in their ratings on a particular item (e.g., how frequently the man pushed the woman), the higher score was used. We first created a dyadic-level ordinal variable with 0=no IPV, 1=mild psychological IPV, 2=severe psychological IPV, 3=mild physical IPV, 4=severe physical/sexual IPV, and 5=impact/injury due to IPV, for male-to-female and female-to-male IPV. Couple-level IPV was summed across partners, with a range of 0–10 (M = 5.37, SD = 2.92). Supplemental Online Table 1 shows a crosstab of men’s x women’s IPV extent.

Approval of IPV.

We used two scales, a measure of overall justification of IPV —Attitudes Towards Interpersonal Violence (AIV; Riggs & O’Leary, 1996) — and the Situation-Specific Attitudes Toward IPV Scale (Slep & Heyman, 1998), a 10-item scale that presents vignettes and asks respondents to rate their agreement with the male-to-female IPV behavior on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The scale was adapted from the Attitudes About Aggression in Dating Situations Scale (Slep et al., 2001).

Relationship satisfaction

The Quality of Marriage Index (QMI; Norton, 1983) is a six-item inventory that assesses relationship satisfaction using broadly worded, global items; we replaced “marriage” with “relationship” (e.g., “We have a good relationship”). Respondents indicate the degree of agreement with each item on a scale ranging from 1 (Very strong disagreement) to 7 (Very strong agreement). Scores can range from 0 to 39, with higher scores indicated increasing satisfaction. The QMI has excellent (r >.90) convergent validity with other measures of relationship adjustment and satisfaction (Heyman et al., 1994) as well as excellent internal consistency in the current sample (α = 0.96 for men; α = 0.98 for women).

Behavioral Assessment

Rapid Marital Interaction Coding System, 2nd Generation (RMICS2; Heyman et al., 2015).

RMICS2 was used to code the conflict discussions. It is the most recent iteration of a micro-analytic coding system adapted from the Marital Interaction Coding System–IV (MICS–IV; Heyman et al., 1995) and RMICS (Heyman, 2004). Based on a factor analysis of 14 RMICS studies that suggested a more streamlined set of codes (Heyman et al., 2021), RMICS2 comprises seven codes: high hostility, low hostility, constructive problem discussion (neutral), low positivity, high positivity, dysphoric affect, and other. (A default “attention” code is given to listeners who emit no other behavior.) Behavior is defined broadly to include all observable actions (i.e., motoric, verbal, paraverbal, nonverbal). RMICS, and by extension the more parsimonious RMICS2, has excellent content, discriminative, convergent, concurrent, and predictive validity (Heyman, 2004). RMICS2 observers code both speaker and listener behavior in 5-sec intervals and assign one of the seven codes to each unit; if two or more codes are present during unit, a theoretically derived hierarchy (i.e., negative codes then positive codes then neutral codes) dictates which code to retain.

In addition to frequencies of RMICS2 behaviors, we calculated Yule’s Q for lag sequential analysis (Bakeman & Quera, 2011), measuring the likelihood (controlling for chance) that hostility by one partner will immediately follow a hostility by the other.

Fifteen trained coders scored the videos; 25% were coded by two coders blind to whether any particular video was used for measuring agreement. Across the 873 videos for the entire study, interrater agreement was high, with average Guilford’s G = .82. (Because of the highly imbalanced cells, Cohen’s kappa is extremely biased; G, a kappa variant, is the preferred statistic [Xu & Lorber, 2014]. G is interpreted similar to Cohen’s kappa, with values of .40–.59 “fair,” .60–.74 “good,” and values > .75 “excellent” [Cicchetti, 1994].) Gs per code were as follows: Hostility-High = 1.00; Hostility-Low = 0.85; Constructive Problem Discussion = 0.73; Positivity-Low = 0.89; Positivity-High = 1.00; Dysphoric Affect = 1.00. Because of the low frequencies of high-intensity codes, some analyses combined low- and high-hostility and low- and high-positivity. (See Table 1 for means and standard deviations.)

Typicality of Laboratory Behavior (Foster et al., 1997).

The typicality measure is an 8-item scale of the external validity of in-lab conversations to similar conversations at home. Responses ranged on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = much less than usual to 5 = much more than usual. Both positive and negative behaviors are assessed. An example of a positive behavior question is, “Compared with the usual difficult or stressful conversations between us, the amount of support or understanding my partner just showed was…” Responses were recoded (from −2 to +2) and centered so that 0 = “usual;” negative scores indicate less than at-home behavior, and positive numbers indicate more than at-home behavior. Internal consistency was high for the positive behaviors subscale (α = 0.78 for men; α = 0.85 for women) and reasonable for the negative behaviors subscale (α = 0.58 for men; α = 0.69 for women) across both conversations.

Procedures

On arrival, participants read and signed informed consent forms, were ushered into separate rooms, and then completed the relationship satisfaction and IPV measures and the Areas of Change Questionnaire (Weiss & Birchler, 1975), which was used to determine the topics for the three ten-minute videotaped discussions. Three topics were chosen: one for a warm-up conversation (with partners instructed to “communicate as you do at your best”) and two for the “typical” conversations analyzed in this paper. The first two topics were randomly selected from the woman’s top two areas of desired change, and the third was the man’s top area of desired change. (We were faced with time limitations to the entire protocol, which included many procedures not germane to the current study, which prevented a fully crossed design. Because of the needs of the larger study, conversation order was fixed: warm-up [woman’s topic], typical woman’s topic, and typical man’s topic.)

Before each interaction, researchers met with each partner, let him/her know the topic, and said, “We’d like to see you demonstrate how you typically discuss problems when you are at home. We’ve already seen what it’s like when you’re at your best, and this time we’d like to see what it’s like when you’re not at your best, but you’re just being yourselves.” After the instructions, partners were brought together in the living-room-like space equipped with video cameras and microphones, and they were asked to begin once the researcher left. After each 10-minute discussion, the researcher re-entered the room, accompanied participants to separate rooms, and asked each to complete the typicality questionnaire. Partners then separately participated in a range of procedures not germane to the current study.

After finishing the full protocol, participants were paid, debriefed, and provided with a list of community resources.

Data Analysis

We examined differences in RMICS2 code frequency and sequences as a function of IPV, relationship satisfaction, conversation initiator, gender, and IPV × relationship satisfaction with a series of mixed models in SPSS. Gender and conversation initiator were effects coded, and relationship satisfaction was grand-mean centered to aid interpretability. All hypothesized main effects, 2-way, and 3-way interactions were tested in the main model. Follow-up sensitivity analyses added gender and all its related 2-, 3-, and 4-way interactions. After examining the models, all non-significant higher-level interactions were dropped, resulting in the final reported models. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics for main study variables.

Results

Check of Situational Couple Violence (SCV) Status

Johnson (2006) specifies that SCV couples do not possess attitudes approving male-to-female IPV. To ensure that our description of our couples as SCV is correct, we calculated the percentage of men and women whose (a) average justification score on the AIV was <=4 (“rarely”) and (b) average on the Situation-Specific Attitudes Toward IPV Scale indicated disagreement with IPV-enactment. On the AIV, 96.63% of men and 98.23% of women indicated that IPV was rarely or never justified. On the Situation-Specific measure, 93.2% of men and 95.86% of women disagreed with the use of IPV in the vignettes. Thus, nearly all of our couples fall squarely within the SCV group.

Internal and External Validity of Observations

Internal validity.

As recommended by Crenshaw et al. (2021), we tested if individuals initiating conversations desired as much or more change on that topic as their partners did. In 84.9% of the female-initiated conversations, women desired more change; in 87.7% of the male-initiated conversations, men desired more change. Thus, overall, the procedures worked.

External Validity.

On the typicality measure, men and women reported that, compared with at-home difficult conversations, their partners acted about “about usual” (i.e., 0) for both positive (female-initiated conversations — men: M = 0.16 [SD = 0.52]; women: M = 0.15 [SD = 0.60]; male-initiated — men: M = 0.23 [SD = 0.63]; women: M = 0.23 [SD = 0.55]) and negative (female-initiated — men: M = −0.08 [SD = 0.58]; women: M = −0.17 [SD = 0.58]; male-initiated — men: M = −0.18 [SD = 0.91]; women: M = −0.06 [SD = 0.63]) behavior.

Hypothesized Impacts of IPV-Extent and Satisfaction on Observed Conflict Behavior

Frequency of hostility

As hypothesized, individuals who reported less satisfaction or more extensive IPV displayed more hostility (see Table 2). However, there was not a significant relationship dissatisfaction × IPV interaction. In addition, women displayed more frequent hostility than men did, and sensitivity analyses revealed that this effect depended on the initiator. Post hoc tests of simple effects indicated that women displayed an average of 10.40 more hostile behaviors than men did in female-initiated conversations (p < .001), whereas in male-initiated conversations, men displayed an average of 2.28 more hostile behaviors than women did, but this difference was not significant (p = n.s.).

Table 2.

Hypotheses 1 and 2: Hostility, Positivity, and Negative Reciprocity Final Models

| Hypothesis 1: Frequencies | Hostility Frequency | Positivity Frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variable | B | SE | p | B | SE | p |

| Intercept | 14.20 | 1.01 | .000*** | 9.89 | 0.77 | .000*** |

| Conversation Initiator | −2.03 | 0.47 | .000*** | 0.56 | 0.20 | .006** |

| Gender | −3.56 | 0.64 | .000*** | −0.53 | 0.20 | .010* |

| Satisfaction | −0.41 | 0.17 | .018* | 0.25 | 0.06 | .000*** |

| Couple IPV Extent | 1.42 | 0.33 | .000*** | −0.21 | 0.13 | .104 |

| Satisfaction × Couple IPV Extent | −0.04 | 0.03 | .158 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .290 |

| Conversation Initiator × Gender | 3.17 | 0.46 | .000*** | - | - | - |

| Hypothesis 2: Sequences | Negative Reciprocity | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Variable | B | SE | p | |||

|

| ||||||

| Intercept | −.01 | 0.06 | .934 | |||

| Conversation Initiator | −.03 | 0.05 | .564 | |||

| Gender of Hostile→Hostile Responder | −0.02 | 0.02 | .363 | |||

| Satisfaction | 0.01 | 0.01 | .226 | |||

| Couple IPV Extent | 0.01 | 0.01 | .397 | |||

| Satisfaction × Couple IPV Extent | −0.00 | 0.00 | .976 | |||

| Gender × Couple IPV Extent | - | - | - | |||

| Conversation Initiator × Satisfaction | 0.01 | 0.01 | .004* | |||

| Conversation Initiator × Couple IPV Extent | −0.00 | 0.01 | .614 | |||

| Conversation Initiator × Satisfaction × Couple IPV Extent | −0.00 | 0.00 | . 006* | |||

Note. B = unstandardized regression coefficient, SE = standard error

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Negative reciprocity

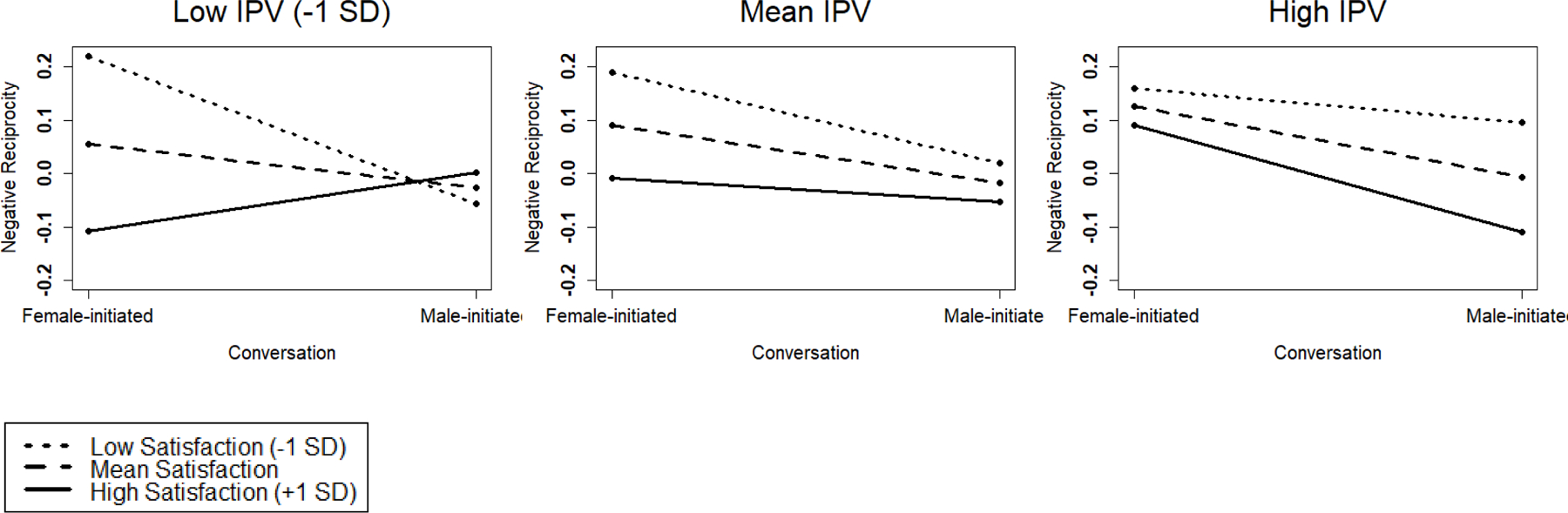

We did not find support for hypothesized main effects for negative reciprocity in the initial models; sensitivity tests revealed a significant dissatisfaction × IPV × initiator interaction (See Table 2). We used Preacher et al.’s (2006) methods and website to probe the interaction.

We first examined whether there were significant differences between conversations by examining simple slopes at low, average, and high values of IPV (i.e., −1 SD [2.32], mean [5.29], +1 SD [8.26]) and relationship satisfaction (i.e., −1 SD [10.846], mean [0], and +1 SD [10.846]). Figure 1 presents a plot of differences in negative reciprocity between conversations as a function of low, mean, and high levels of relationship satisfaction and IPV. There was significantly more negative reciprocity in female-, versus male-, initiated conversations for couples reporting low levels of both IPV and satisfaction (−1 SD) (left plot; B = −0.1376, SE = 0.0574, p = 0.0169), as well as for couples reporting mean IPV with either low (−1 SD) or mean levels of satisfaction (middle plot; B = −0.0849, SE = 0.0341, p = 0.0132 and B = −0.0536, SE = 0.0243, p = 0.0281, respectively). There were not significant differences between initiators among (a) couples reporting high (+1 SD) IPV, regardless of level of relationship satisfaction (right plot); (b) couples reporting low (−1 SD) levels of IPV together with either mean or high (+1 SD) levels of satisfaction, or (c) couples reporting mean levels of IPV together with high (+1 SD) levels of satisfaction.

Figure 1.

Interaction of Satisfaction and Intimate Partner Violence on Negative Reciprocity in Female- and Male-Initiated Conversations

Couples reporting low IPV used more negative reciprocity in female-, compared with male-, initiated conversations when satisfaction was below −4.9 (approximately ½ SD below the mean; B = −0.08, SE = 0.04, p = 0.05). Couples with mean IPV used more negative reciprocity in female-, compared with male-, initiated conversations when satisfaction was below 1.649 (i.e., just above the mean; B = −0.05, SE = 0.02, p = 0.05). Finally, couples with high IPV used more negative reciprocity in female-, versus male-, initiated conversations when satisfaction was between a small range of values just above the mean (between 0.1829 [B = −0.07, SE = 0.03, p = 0.05] and 1.3973 [B = −0.07, SE = 0.04, p = 0.05]).

Frequency of positivity

Consistent with hypotheses, individuals who reported greater relationship satisfaction emitted more positivity (see Table 2). However, there was not a significant main effect of IPV or interaction of dissatisfaction × IPV. In addition to effects testing hypotheses, there were significant main effects of gender and conversation initiator on positivity. Women displayed more frequent positivity than men did, and partners displayed more frequent positivity in male-, compared with female-, initiated conversations. See Table 2 for final model results.

Discussion

The results of this study clearly show that observed conflict behaviors of mixed-sex couples are affected by the intersection of gender, satisfaction, and extent of both partners’ psychological and/or physical IPV. Notably, this is the first study to examine all three simultaneously in couples marked by situational couples violence (Johnson, 2016).

The overarching finding from the hypotheses tested is that there are multiple significant influences on conflict behavior. Hypothesis 1 was generally supported, although we did not find the hypothesized impellance interactions (Finkel, 2007) between satisfaction and IPV-extent. Both increasing unhappiness and increasingly serious couple-level IPV were uniquely associated with observed hostility. Although women were, overall, more hostile than men were, this was true only when women initiated the conversations. The frequency of observed positivity was associated with satisfaction (but not IPV-extent). There were also main effects for gender (i.e., women were more frequently positive than men were) and conversation initiator (i.e., there was more positivity in male-, compared with female-, initiated conversations). Contrary to hypotheses, there were no significant interactions.

Hypothesis 2 was partially supported. Negative reciprocity (Patterson, 1982) also demonstrated intersectionality, with an initiator by satisfaction by IPV-extent interaction. High-IPV couples were insensitive to who initiated the conversation and remained high in negative reciprocity, as were couples low in IPV with mean-to-high satisfaction levels and those with mean-IPV and high satisfaction. These complicated interaction results indicated that female-initiated conversations were likely to be problematic for high-IPV couples (for whom all conflicts evoked high levels of negative reciprocity) and for those with a sufficient dosage of both impellance variables (IPV-extent and dissatisfaction). Using Finkel’s (2007) I3 model, it appears that for high-IPV couples, conflict instigation plus the impellance from IPV in the behavioral repertoire outweighs the weaker impellance effects of satisfaction. For all other couples, it appears that female-initiated topics (the most common one and more charged ones at home; Heyman et al., 2009) have a higher instigation value, but, as theorized by Finkel (2007), still require sufficient levels of impellance — via either IPV or dissatisfaction — to produce the hallmark of problematic couples: negative reciprocity (Gottman, 1994; Heyman, 2001).

To summarize, our findings indicate considerable nuance in understanding the conflict behavior of mixed-sex couples. Because of the high levels of IPV in distressed couples (e.g., Heyman et al., in press), what we think we know about the observed behavior of distressed couples over the past 50 years (Heyman, 2001) has been confounded by (a) not distinguishing the effects of IPV and dissatisfaction and (b) failing to control for the gender of the initiator of the conversation. IPV-extent and dissatisfaction additively impacted hostility; however, being high in both did not have the outsized (i.e., interactive) impact that clinicians and researchers would expect. Women displayed more hostility during conflicts, but they also displayed more positivity. Furthermore, women were only more hostile during conversations they initiated. Although women tend to desire more change and initiate conversations more (e.g., Heyman et al., 2009), this is not true for all topics (e.g., sex). The negative reciprocity results emphasized the nuanced, complicated intersection of gender, satisfaction, and IPV.

Next, who initiated the conversation matters: (a) women were more hostile only when initiating a conversation, and (b) the gender of the initiator impacted negative reciprocity for most couples except those with more extensive IPV and with high levels of satisfaction.

There are two key clinical implications of these results. First, couple therapists should already be universally assessing couples for IPV for safety and treatment planning reasons (e.g., Stith et al., 2011). These results emphasize that the need to focus on psychological, physical, and sexual IPV — and IPV’s behavioral and emotional aftereffects — in couples therapy for reasons beyond safety that are at the heart of the presenting problems themselves. Most couples presenting for treatment report physical IPV in the past year (Heyman et al., in press), and even more report significant psychological IPV. Treating couples inherently involves undoing the impact of IPV; even if this is often thought to be a specialized form of couples therapy (e.g., Stith et al., 2011), its ubiquity argues that it is not (because providers often do not screen for the full range of IPV, and couples rarely list it as a presenting problem; O’Leary et al., 1992). Furthermore, the problematic behaviors that tend to drive couples to therapy (e.g., high hostility, patterns of mutually reciprocated hostility) are related to, or exacerbated by, the extent of dyadic IPV. The bottom line is that “specialized” therapy for IPV couples — focusing on SCV couples’ instigating, impelling, and inhibiting factors for all forms of IPV, not just physical IPV (e.g., Epstein et al., 2015; Stith et al., 2011) — is a misnomer. Something is not a specialized treatment if it is likely indicated for the vast majority of purportedly “garden variety” distressed couples presenting for treatment, if only the assessment were comprehensive enough. Second, therapists should be alert to how differences in partners’ behavior and patterns are affected by who is pushing for change (i.e., what behaviorists term a “discriminative stimulus”). Gottman (e.g., Gottman et al., 1999) has interpreted similar findings as being due to men rejecting women’s influence). Our findings underscore the importance of addressing these dynamics in treatment. Furthermore, a treatment plan or approach that might have been crafted for a predominant presentation (e.g., that driven by female-initiated concerns) may need to be significantly altered for other problems when driven by the other men’s primary concerns. That is, the gendered context of mixed-sex couples’ problems, not surprisingly, leads to their behaviors varying when men, rather than women, are pressing for change.

This study had some notable strengths. First, the sample was drawn from a representative sampling frame using random-digit dialing. The sample was reasonably representative of the exurban county from which it was drawn, albeit one that is less racially/ethnically diverse than the U.S. as a whole. Replication in more diverse samples is needed. Second, the conflicts elicited in the laboratory were judged by participants to be typical of their at-home conflicts, bolstering the study’s external validity. Third, this is the first study to make empirical estimates of the unique, additive, and interactive impacts of relationship satisfaction and IPV on couples’ conflict behaviors. Fourth, appropriate for our situationally couple violent sample, we measured the IPV-extent on an ordinal scale comprising both partners’ behavior. Finally, because some past research has found that gender differences in behavior depend on which partner is pursuing change in a conversation, we observed couple conflicts in which each partner brought up one of their top areas of change; furthermore, we tested to make sure that the purported change agent actually reported desiring more change on that issue than their partner did.

Four limitations of this study should be delineated. First, studies conducted with community — as opposed to criminal justice-involved — samples comprise, almost exclusively, couples with SCV. We documented that this was the case with our sample. Although SCV is the predominant form of IPV and sometimes results in injury or fear, it is not the most dangerous or deadly form. Our results are unlikely to apply to relationships marked by intimate terrorism and should not be generalized to them. Second, the order of the conversations was not counterbalanced; the female-initiated conversation always preceded the male-initiated one (and both followed a warm-up conversation). Given that (a) the gender-of-initiator was not a primary focus of the study and (b) the participant-rated typicality of the conversations did not differ significantly, the order of the conversation is likely of minor importance. Third, the age representativeness of the sample necessarily means that our couples were older and more established than those at the peak risk for IPV (couples in early adulthood; Rivara et al., 2009). Thus, the results would need to be replicated in couples in adolescence and emerging adulthood. Fourth, this study was of mixed-sex couples and should be replicated in couples with other orientations (e.g., same-sex couples). Finally, the data collection was completed in 2003; although it is unlikely the interrelationships among the variables studied here have changed in the intervening time, this should be taken into consideration.

In conclusion, this study showed that research involving couples behavior should assess both satisfaction and the extent of psychological and physical IPV. In addition, as this is yet another study that found behavioral differences depending on who is initiating the conversation, it underscores the importance of collecting observations that vary who is the change agent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH057779) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (R49CCR218554). Dr. Baucom’s effort was also supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (K23DK115820). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

We have adopted terminology common in the couples field. “Relationship distress” refers to couples scoring below the clinically significant threshold on a questionnaire. “Relationship satisfaction” refers to scores on a continuous measure.

References

- Archer J (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 651–680. 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Graham K, Canady B, & Ross JM (2011). A proximal change experiment testing two communication exercises with intimate partner violent men. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 336–347. 10.1016/j.beth.2010.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, & Quera V (2011). Sequential analysis and observational methods for the behavioral sciences Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bell KM, & Naugle AE (2008). Intimate partner violence theoretical considerations: Moving towards a contextual framework. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(7), 1096–1107. 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchler GR, Weiss RL, & Vincent JP (1975). Multimethod analysis of social reinforcement exchange between maritally distressed and non-distressed spouse and stranger dyads. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31(2), 349–360. 10.1037/h0076280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burman B, Margolin G, & John RS (1993). America’s angriest home videos: Behavioral contingencies observed in home reenactments of marital conflict. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(1), 28–39. 10.1037/0022-006X.61.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, November). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2015 Data Brief – Updated Release https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf

- Christensen A, & Heavey CL (1990). Gender and social structure in the demand/withdraw pattern of marital conflict. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(1), 73–81. 10.1037/0022-3514.59.1.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284–290. 10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coan J, Gottman JM, Babcock J, & Jacobson N (1997). Battering and the male rejection of influence from women. Aggressive Behavior, 23(5), 375–388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JV, Jacobson NS, Gottman JM, Rushe R, & Cox G (1993). Negative reciprocity and communication in couples with a violent husband. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102(4), 559–564. 10.1037/0021-843X.102.4.559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw AO, Leo K, Christensen A, Hogan JN, Baucom KJW, & Baucom BRW (2021). Relative importance of conflict topics for within-couple tests: The case of demand/withdraw interaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 35(3), 377–387. 10.1037/fam0000782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein NB, Werlinich CA, & LaTaillade JJ (2015). Couple therapy for partner aggression. In Gurman AS, Lebow JL, & Snyder DK (Eds.), Clinical handbook of couple therapy (p. 389–411). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ (2008). Impelling and inhibiting forces in the perpetration of intimate partner violence. Review of General Psychology, 11(2), 193–207. 10.1037/1089-2680.11.2.193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, Beach SRH, Slep AMS, Heyman RE, & Wamboldt MZ (Eds.). (2013). Family Problems and Family Violence: Reliable Assessment and the ICD-11 Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Foster DA, Caplan RD, & Howe GW (1997). Representativeness of observed couple interaction: Couples can tell, and it does make a difference. Psychological Assessment, 9(3), 285–294. 10.1037/1040-3590.9.3.285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friend DJ, Bradley RPC, & Gottman JM (2017). Displayed affective behavior between intimate partner violence types during non-violent conflict discussions. Journal of Family Violence, 32(5), 493–504. 10.1007/s10896-016-9870-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gordis EB, Margolin G, & Vickerman K (2005). Communication and frightening behavior among couples with past and recent histories of physical marital aggression. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36(1–2), 177–191. 10.1007/s10464-005-6241-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM (1994). What predicts divorce? Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM (1999). The marriage clinic: A scientifically-based marital therapy Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman J, Coan J, Carrere S, & Swanson C (1998). Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 60(1), 5–22. doi: 10.2307/353438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heavey CL, Christensen A, & Malamuth NM (1995). The longitudinal impact of demand and withdrawal during marital conflict. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63(5), 797–801. 10.1037/0022-006X.63.5.797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heavey CL, Layne C, & Christensen A (1993). Gender and conflict structure in marital interaction: A replication and extension. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(1), 16–27. 10.1037/0022-006X.61.1.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE (2001). Observation of couple conflicts: Clinical assessment applications, stubborn truths, and shaky foundations. Psychological Assessment, 13(1), 5–35. 10.1037/1040-3590.13.1.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE (2004). Rapid Marital Interaction Coding System. In Kerig PK & Baucom DH (Eds.) Couple observational coding systems (pp. 67–94). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Lorber MF, Kim S, Wojda-Burlij AK, Stanley SM, Ivic A, Snyder DK, Rhoades GK, Whisman MA, & Beach SRH (in press). Overlap of relationship distress and intimate partner violence in community samples. Journal of Family Issues [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Heyman RE & Slep AMS (2004). Analogue methods. Encyclopedia of Psychological Assessment, 3, 162–180. 10.4135/9780857025753.n5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Hunt-Martorano AN, Malik J & Slep AMS (2009). Desired change in couples: Gender differences and communication. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(4), 474–484. 10.1037/a0015980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Lorber MF, Eddy JM, & West TV (2014). Behavioral observation and coding. In Reis HT & Judd CM (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (p. 345–372). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Sayers SL, & Bellack AS (1994). Global marital satisfaction versus marital adjustment: An empirical comparison of three measures. Journal of Family Psychology, 8(4), 432–446. 10.1037/0893-3200.8.4.432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE & Schlee KA (1997). Toward a better estimate of the prevalence of partner abuse: Adjusting rates based on the sensitivity of the Conflict Tactics Scale. Journal of Family Psychology, 11(3), 332–338. 10.1037/0893-3200.11.3.332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Weiss RL, & Eddy JM (1995). Marital Interaction Coding System: Revision and empirical evaluation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(6), 737–746. 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00003-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Wojda AK, Hopfield JF & Salas GM (2015). Rapid Marital Interaction Coding System (2nd Generation). [Unpublished technical manual]. Family Translational Research Group, New York University. https://scienceofbehaviorchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Rapid_Marital_Interaction_Coding.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, & Stuart G (1994). Typologies of male batterers: Three subtypes and the differences among them. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 476–497. 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Smutzler N, & Stuart GL (1998). Demand and withdraw communication among couples experiencing husband violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(5), 731–743. 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Gottman JM, Waltz J, Rushe R, Babcock J, & Holtzworth-Munroe A (1994). Affect, verbal content, and psychophysiology in the arguments of couples with a violent husband. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(5), 982–988. 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP (1995). Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: Two forms of violence against women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 57(2), 283–294. 10.2307/353683 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP (2006). Conflict and control: Gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence against Women, 12(11), 1003–1018. 10.1177/1077801206293328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, & Kenny ED (2003). Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(2), 339–352. 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, McCullars A, & Misra TA (2012). Motivations for men and women’s intimate partner violence perpetration: A comprehensive review. Partner Abuse, 3(4), 429–468. 10.1891/1946-6560.3.4.429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, & Bradbury TN (2001). Physical aggression and marital dysfunction: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(1), 135–154. 10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF, Erlanger ACE, Heyman RE, & O’Leary KD (2015). The honeymoon effect: Does it exist and can it be predicted? Prevention Science, 16(4), 550–559. 10.1007/s11121-014-0480-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loseke DR, Gelles RJ & Cavanaugh MM (Eds.) (2005). Current controversies on family violence SAGE. 10.4135/9781483328584 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, John RS, & Gleberman L (1988). Affective responses to conflictual discussions in violent and nonviolent couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(1), 24–33. 10.1037//0022-006x.56.1.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, John RS, & O’Brien M (1989). Sequential affective patterns as a function of marital conflict style. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 8(1), 45–61. 10.1521/jscp.1989.8.1.45 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newton RR, Connelly CD, & Landsverk JA (2001). An examination of measurement characteristics and factorial valdity of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61(2), 317–335. 10.1177/0013164401612011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noller P, & Roberts ND (2002). The communication of couples in violent and nonviolent relationships: Temporal associations with own and partners’ anxiety arousal and behavior. In Noller P & Feeney JA (Eds.), Understanding Marriage: Developments in the Study of Couple Interaction (pp. 348–378). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511500077.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norton R (1983). Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45(1), 141–151. 10.2307/351302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Vivian D, Malone J (1992). Assessment of physical aggression against women in marriage: The need for multimodal assessment. Behavioral Assessment, 14(1), 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary SG, & Slep AMS (2006). Precipitants of partner aggression. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(2), 344–347. 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR (1982). Coercive family process Castalia. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31(4), 437–448. 10.3102/10769986031004437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara FP, Anderson ML, Fishman P, Reid RJ, Bonomi AE, Carrell D, & Thompson RS (2009). Age, period, and cohort effects on intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims, 24(5), 627–638. 10.1891/0886-6708.24.5.627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford K (2006). Communication during marital conflict: When couples alter their appraisal, they change their behavior. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(2), 256–265. 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Caetano R, & Clark CL (2002). Agreement about violence in U.S. couples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17(4), 457–470. 10.1177/0886260502017004007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson LE, Doss BD, Wheeler J, & Christensen A (2007). Relationship violence among couples seeking therapy: Common couple violence or battering? Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33(2), 270–283. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00021.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep AMS, Cascardi M, Avery-Leaf S, & O’Leary KD (2001). Two new measures of attitudes about the acceptability of teen dating aggression. Psychological Assessment, 13(3), 306–318. 10.1037/1040-3590.13.3.306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep AMS & Heyman RE (1998). Situation-Specific Attitudes Toward IPV Scale [Unpublished manuscript]. Family Translational Research Group, New York University. [Google Scholar]

- Slep AMS, Heyman RE, Williams MC, Van Dyke CE, & O’Leary SG (2006). Using random telephone sampling to recruit generalizable samples for family violence studies. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(4), 680–689. 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer J, Iyican S, & Babcock J (2019). The relation between contempt, anger, and intimate partner violence: A dyadic approach. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(15), 3059–3079. 10.1177/0886260516665107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, McCollum EE, & Rosen KH (2011). Couples therapy for domestic violence: Finding safe solutions American Psychological Association. 10.1037/12329-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA (2004). Prevalence of violence against dating partners by male and female university students worldwide. Violence Against Women, 10(7), 790–811. 10.1177/1077801204265552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, & Sugarman DB (1996). The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 283–316. 10.1177/019251396017003001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz J, Babcock JC, Jacobson NS, & Gottman JM (2000). Testing a typology of batterers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 658–669. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RL, & Birchler GR (1975). Areas of Change questionnaire [Unpublished manuscript]. Department of Psychology, University of Oregon. [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Beach SRH, & Snyder DK (2008). Is marital discord taxonic and can taxonic status be assessed reliably? Results from a national, representative sample of married couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 745–755. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.5.745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, & Lorber MF (2014). Interrater agreement statistics with skewed data: Evaluation of alternatives to Cohen’s kappa. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 1219–1227. 10.1037/a0037489.supp [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.