Abstract

Purpose

To examine processes, barriers, and facilitators to sperm banking counseling and decision-making for adolescent males newly diagnosed with cancer from the perspective of clinicians who completed Oncofertility communication training. We also identify opportunities for improvement to inform future interventions and implementation.

Methods

A survey (N=104) and subsequent focus groups (N=15) were conducted with non-physician clinicians practicing in pediatric oncology who completed Oncofertility communication training.

Results

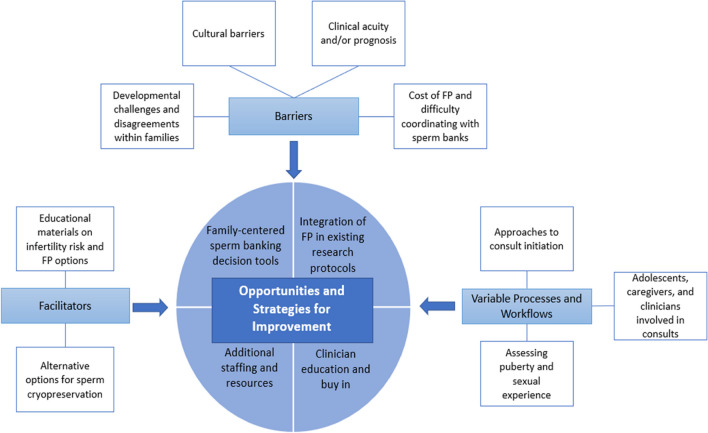

Most survey participants were confident in communicating about the impact of cancer on fertility (n=87, 83.7%) and fertility preservation options (n=80, 76.9%). Most participants reported never/rarely using a sperm banking decision tool (n=70, 67.3%), although 98.1% (n=102) said a decision tool with a family-centered approach would be beneficial. Primary themes in the subsequent focus groups included variable processes/workflows (inconsistent approaches to consult initiation; involvement of adolescents, caregivers, and various clinician types; assessment of puberty/sexual experience), structural and psychosocial barriers (cost and logistics, developmental, cultural, clinical acuity/prognosis), and facilitators (educational materials, alternative options for banking). Opportunities and strategies for improvement (including fertility preservation in existing research protocols; additional staffing/resources; oncologist education and buy-in; and development of decision tools) were informed by challenges identified in the other themes.

Conclusion

Barriers to adolescent sperm banking remain, even among clinicians who have completed Oncofertility training. Although training is one factor necessary to facilitate banking, structural and psychosocial barriers persist. Given the complexities of offering sperm banking to pediatric populations, continued efforts are needed to mitigate structural barriers and develop strategies to facilitate decision-making before childhood cancer treatment.

Keywords: Oncofertility, Fertility preservation, Fertility counseling, Decision-making, Clinicians

Introduction

Over 15,000 individuals under the age of 20 are diagnosed with cancer each year in the USA [1], and treatment advances have resulted in 85% 5-year survival rates [2]. Most childhood cancer survivors experience at least one adverse late effect of treatment [3]. Over half of male childhood cancer survivors are at risk for impaired fertility [4]. Given that initial infertility risk predictions are imperfect and fertility impairment is known to cause psychosocial distress among survivors [5], fertility counseling is recommended before initiation of cancer therapy [6, 7].

Despite the fact that sperm banking is an established, effective, and typically non-invasive fertility preservation (FP) option, pre-treatment sperm banking rates remain low at many pediatric centers [8–10]. Both survivors and their parents have reported regret about missed opportunities for sperm banking, retrospectively wishing they were given more information about banking before treatment [11]. Practice patterns at even relatively high-resourced settings are not consistent with current guidelines. A recent Children’s Oncology Group (COG) survey of 144 programs showed 98% offered sperm banking [12], but almost one-third offered it after treatment initiation [13].

Counseling adolescent males newly diagnosed with cancer about FP is uniquely challenging given the physical and psychosocial implications of a new pediatric cancer diagnosis and limitations in their ability to plan for the future [14]. Furthermore, unlike adults who can typically make autonomous medical decisions, a sperm banking decision in the pediatric context requires the informed consent and active participation of the adolescent and effective communication and shared decision-making between clinicians, parents, and adolescents, often in a very short time frame [15, 16]. Research suggests both clinicians (i.e., a healthcare professional qualified in the clinical practice of medicine, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and other allied health professionals [17]) and parents have an important influence on sperm banking decisions, yet some of the topics may be difficult to discuss, such as masturbation or electroejaculation [18, 19].

Clinicians play an essential role in delivering sperm banking counseling; however, one survey study showed 92% of oncology providers had no formal training in FP, and some were not comfortable with this topic [20]. In this context, the web-based adolescent and young adult Oncofertility-related training for nurses, ENRICH (Educating Nurses about Reproductive Issues in Cancer Healthcare), and the subsequent training for allied health professionals, ECHO (Enriching Communication skills for Health professionals in Oncofertility), were developed. ENRICH/ECHO includes modules on FP, sexual health, psychosocial issues, and communication strategies to improve knowledge and confidence in Oncofertility counseling; clinicians have been recruited nationally to receive this training (2011–present) [21–25]. The aims of this mixed-methods study were to (1) examine processes, barriers, and facilitators for adolescent sperm banking counseling and patient decision-making among Oncofertility clinicians who recently completed this training and (2) identify opportunities to improve Oncofertility care delivery for adolescent males with cancer to inform future interventions.

Methods

Procedures

In this explanatory, sequential, mixed-methods study, a survey and subsequent focus groups were conducted. The study was deemed non-human subjects (NYU IRB). The 38-item survey was administered (September 2022) via a listserv as part of the yearly follow-up for former ECHO learners (2016–2021; N=567). Items assessed participants’ academic engagement with and clinical practices regarding a variety of reproductive health topics; participants received a $10 gift card upon completion. Survey items related to the facilitation of adolescent sperm banking were the focus of this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Survey responses

| Question | Response options | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rate your confidence in your communication skills with adolescent oncology patients on the impact of cancer on fertility | Not at all confident | 0 | 0 |

| Slightly confident | 2 | 1.92 | |

| Somewhat confident | 15 | 14.42 | |

| Confident | 47 | 45.19 | |

| Very confident | 40 | 38.46 | |

| Rate your confidence in your communication skills with AYA oncology patients on fertility preservation options | Not at all confident | 0 | 0 |

| Slightly confident | 3 | 2.88 | |

| Somewhat confident | 21 | 20.19 | |

| Confident | 43 | 41.35 | |

| Very confident | 37 | 35.58 | |

| How frequently do you use a sperm banking decision tool (e.g., values clarification tool, decision aid) for pubertal males? | Never | 58 | 55.77 |

| Rarely | 12 | 11.54 | |

| Sometimes | 24 | 23.08 | |

| Often | 5 | 4.81 | |

| Always | 5 | 4.81 | |

| If so, does your decision tool include both adolescent and parent perspectives? | Yes | 31 | 72.09 |

| No | 12 | 27.91 | |

| How beneficial would it be to have a sperm banking decision tool (e.g., values clarification tool, decision aid) for pubertal males (~12–25 years of age) newly diagnosed with cancer? | Not at all beneficial | 2 | 1.92 |

| Somewhat beneficial | 29 | 27.88 | |

| Very beneficial | 73 | 70.19 | |

| How beneficial would it be to use a family-centered approach (i.e., incorporating parents’ perspectives) when using a sperm banking decision tool for pubertal males (~12–25 years of age) newly diagnosed with cancer? | Not at all beneficial | 1 | 0.96 |

| Somewhat beneficial | 30 | 28.85 | |

| Very beneficial | 73 | 70.19 |

To explain and contextualize the quantitative findings, all participants who indicated working with pediatric patients in the yearly follow-up survey were invited via email to participate in a focus group. Two, 1-h virtual focus groups (n1=8, n2=7) were conducted in February 2023 with verbal consent obtained prior to the audio-recorded sessions. The welcome script began the session as follows: As you know, you’ve been asked to participate in this group because you have completed ECHO training and are involved in the delivery of fertility preservation counseling for adolescent males with cancer. Subsequently, a semi-structured focus group guide was utilized, which began with a vignette of a 15-year-old pubertal male newly diagnosed with lymphoma, and then explored aspects of discussing adolescent sperm banking within their institutions (Table 2). Sociodemographic information of focus group participants (i.e., age, years in practice, gender, race, ethnicity, primary institution type, discipline) was collected through a REDCap survey after each focus group, and participants received a $30 gift card.

Table 2.

Focus group items

| Focus group guide | Who initiates fertility consultations? |

| Who do you involve in conversations about fertility? | |

| Which adolescents receive fertility consultations? How do you ensure that all eligible adolescents receive a consultation? | |

| How is puberty and sexual experience assessed? | |

| How is shared decision-making facilitated? | |

| Which decisional support tools and resources do you use? | |

| What alternate options exist if the patient is unwilling/unable to produce a sample? | |

| What barriers do you encounter? | |

| What improvements could be made? |

Data analyses

Descriptive quantitative analysis of the survey was conducted in SPSS. Focus groups were transcribed verbatim and analyzed by three coders using the constant comparative method (i.e., an approach to qualitative analysis where information is categorized as it compares and contrasts to other information shared, allowing patterns to emerge in the data that from themes [26]) to identify common themes and patterns in participants’ responses.

Results

Quantitative

Two hundred thirty-eight people completed the survey, though only those who had complete data and worked in pediatrics (n=64, 26.9%) or both pediatrics and adults (n=40, 16.8%) were included in these analyses, leaving a total sample of 104. Survey respondents (response rate=30% of eligible learners) included social workers (n=33, 31.7%), psychologists (n=26, 25.0%), nurse practitioners (n=16, 15.4%), nurses (n=15, 14.4%), physician assistants (n=5, 4.8%), and other medical professionals (n=9, 8.7%). The size of practice setting was variable, with 42.3% (n=44) working at cancer centers with less than 100 new diagnoses per year, 28.8% (n=30) in settings with 100–200, and 28.8% (n=30) in settings that see more than 200 new diagnoses per year.

Most participants reported feeling confident in their communication skills when discussing the impact of cancer on fertility (n=87, 83.7%) and FP options (n=80, 76.9%) with adolescent oncology patients (Table 1). Although most reported that they never or rarely used a sperm banking decision tool (n=70, 67.3%), 98.1% (n=102) said such a tool would be beneficial. Of the 43 participants who reported using a decision tool, 72.1% said their tool included both adolescent and parent perspectives. Furthermore, 99.0% (n=103) of participants reported it would be beneficial to use a decision tool with a family-centered approach.

Qualitative

Focus group participants (N=15) were primarily women (n=12, 80%), with a median age of 40–45 years, who worked in pediatric practices (n=10), adult and pediatric practices (n=4), and academic health centers (n=8). All participants worked in settings with adolescent male patients. Participants included social workers (n=4), nurse practitioners (n=3), nurses (n=6), a psychologist (n=1), and a director of provider relations and navigation (n=1). All participants were White and non-Hispanic, and most had been in oncology practice for ≥10 years (n=10, 66.67%).

Themes

There were four major themes discussed in response to the vignette and focus group questions (Table 2): (1) variable processes and workflows, (2) barriers, (3) facilitators, and (4) opportunities and strategies for improvement.

Variable processes and workflows

Variation in procedures

The initiation of fertility consults for adolescent males newly diagnosed with cancer varied greatly across centers. Some participants, particularly those at centers with dedicated fertility navigators, said consultations were automatically initiated at the time of a new cancer diagnosis. Others endorsed more variability, stating “whether a referral comes in or not is dependent on who’s on service,” or that their site relied on staff to review every chart to identify candidates for fertility consultations, “we’re always going to miss people…of course we don’t want to, but we have a lot of adolescent patients come through the doors, so it’s tough.” Participants also noted variability based on setting, as different staff would be available to complete the fertility consultation in the outpatient versus inpatient setting. Finally, most participants noted a lack of standardization in ongoing fertility-related discussions. One participant stated, “it’s relying on the provider to have that follow-up conversation, or for the patient or family to ask about it again,” and another noted, “I worry that [conversation] doesn’t get carried on throughout treatment and post-treatment.”

Who is involved in fertility-related discussions

There was wide variability between centers regarding who led fertility-related discussions. Some settings relied on designated fertility navigators/coordinators to lead the fertility consultation (often after the topic was introduced by the oncologist), whereas sites without these resources relied on whomever was available to address fertility (i.e., ranging from the oncologist on service to the on-call gynecology residents). Most participants reported that they involved both the adolescent and parents in the discussions. “We try to meet with the family as a whole to lightly discuss it and gauge their reaction to see if we have to meet with the teen or the parents alone.”

Assessing puberty and sexual experience

Participants noted inconsistent approaches for determining whether an adolescent would be able to produce a sample for sperm banking. Regarding assessing pubertal status and sexual experience, one participant said: “the team that’s doing the diagnostic work up will document physical features of puberty…I don’t think we’re as good at asking about sexual health upfront.” Other participants reported challenges with these assessments: “that’s not usually done by the teams…I wish we had a better way,” or “I’m often begging, can you do a Tanner stage?” One participant said that their consultations are often virtual without opportunities for Tanner staging, “most of the time our conversation actually starts over the phone…we just ask if there are any issues with erection or ejaculations.”

Barriers

Cost and logistics

Cost was a frequently cited barrier given that banking is rarely covered by insurance and is an added cost during an already financially stressful cancer diagnosis. One participant’s center had a grant to cover the cost of sperm banking, but all other participants cited cost as a major barrier to sperm banking. “Unfortunately, families are always asking about costs. So, I have some cost sheets I can give them, and then I’ll talk about whatever else we’re trying to utilize to bring the cost down, since 99% of my patients have no insurance coverage for it.”

In addition to financial barriers, many participants discussed challenges coordinating FP with sperm banks. Participants noted a lack of onsite sperm banks, explaining that families often must courier the sample from the hospital to the sperm bank. “If we have an inpatient, the courier has messed up a number of times with getting the sample directly there. So, that’s definitely a huge barrier.” Additionally, most sperm banks had limited hours, making banking logistics even more difficult. “Our lab is only open Monday through Friday. It closes at two in the afternoon, so, that’s a whole other issue.”

Developmental challenges

Participants also discussed challenges specific to adolescents, both in making banking decisions and in producing a sample. Some participants mentioned that adolescent boys do not want to discuss sperm banking, as they find it embarrassing. One participant shared her experience with a patient, who initially was embarrassed but eventually found it to be empowering. “I’ve got one teenage boy whose comment was that cancer is very degrading and undignified, and to then ask them to do something else that they’re really not comfortable with, that they’ve never even talked about as a family, to them made it more undignified. But being able to talk about that gave him back some feeling of control when he chose to consider whether or not he wanted to bank.”

Participants also noted that many male adolescents had not previously thought about their parenthood goals and were overwhelmed by these conversations in the context of a new cancer diagnosis and urgency to start treatment. Participants discussed the struggle of engaging reluctant adolescents in conversations about parenthood, but felt it was necessary to avoid decisional regret. “They’re 14, 15 years old. They don’t want to talk about having a family. They don’t want to discuss this with you, and then they come back 8, 9, 10 years later and they’re 22, 24 years old, and they regret that decision.” Another stated, “if we could, we’d have hours of conversations around this, but we just don’t have that at diagnosis.” Participants recalled challenging situations in which adolescents and parents disagreed about banking, sometimes with the patient pushing for banking (while parents were prioritizing starting treatment immediately) and other instances when the parents were inclined, but the adolescent did not want to think or talk about banking.

Even among adolescents who made banking attempts, participants noted challenges in producing a sample. One provider doubted that all of their patients knew how to produce a sample. Others discussed that adolescents often struggle to produce a sample in the inpatient setting. “I’ve had two recently…15, 16 years old who were super sick. They were admitted and they couldn’t collect…all the nurses around and the pressure of the situation…just super hard for these adolescents.”

Cultural barriers

An additional barrier was counseling families from diverse backgrounds. One participant discussed their experiences working with Arabic families and said navigating these conversations without culturally responsive materials was challenging, as sexuality is often viewed as a private topic. Another participant stated, “It’s kind of a melting pot of different cultures and nationalities. We’ve had a lot of parents not want us to talk about it at all, because they might think that their teenage boy should not be exploring their body or ejaculating, and it’s a privacy issue that shouldn’t even be spoken about. So, in that respect, it’s very hard to have that conversation.”

Clinical acuity and/or prognosis

Some participants reported challenges in fertility counseling and sperm banking in situations where the initial presentation was severe and/or if prognosis was poor. One participant noted that they are less likely to discuss FP options with adolescents experiencing neurological issues or those in the intensive care unit. Another participant acknowledged differing perspectives about fertility consults in the context of metastatic disease, but stated, “I think it [FP] is still a very important conversation to have regardless of prognosis.”

Facilitators

Educational materials

Participants reported providing families and adolescents with a variety of resources on infertility risk and FP options. Some participants reported showing patients and families a fertility risk chart, the fertility booklet from the Association of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nurses, or referring them to the website, “letstakecharge.org.” Some centers provide branded materials or materials from their associated sperm bank. “We provide them literature on general sperm banking information that we have at [site], as well as whatever cryobank that they use. We generally give them their brochure.”

Options for sperm cryopreservation

Participants discussed alternate options for adolescents unable to produce a semen sample. Although a few participants had access to testicular sperm extraction or electroejaculation, these procedures often took place off-site.

Opportunities and strategies for improvement

Both focus groups ended with participants suggesting opportunities and strategies for improving Oncofertility care delivery for adolescent males with cancer. These suggestions were informed by the challenges identified while discussing varying processes and workflows, barriers, and facilitators (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Opportunities and strategies for improvement as informed by identified variable processes and workflows, barriers, and facilitators

Including FP in existing research protocols

Given the high costs and lack of standardized procedures for discussing FP after a new adolescent cancer diagnosis, one solution proposed by focus group participants was to include FP into established research protocols. According to participants, this would be helpful, “so families could have it more standardized or have it covered [financially] in a different way.” Another participant shared that they advocate for the inclusion of FP in COG new treatment trials whenever the opportunity arises. “I always try to plug it whenever anybody is talking about related things…would be hugely helpful and an easy way to standardize for a large portion of patients.”

Additional resources

Participants also talked about the need for additional resources for fertility programs. Many participants expressed the need for an onsite sperm bank and a dedicated space on site for adolescents to produce the sample. “We’re hoping to one day have a cryobank here, as well as a room for them to do it, because we do a lot of inpatients, and it always takes longer than they anticipate.” By adding dedicated banking facilities to pediatric cancer centers, providers hope to eliminate some of the logistical barriers for adolescents and families. The focus groups also revealed the need for more staffing. “We just keep getting more referrals, but we don’t really add to our team.”

Development of sperm banking decision tools

Participants explicitly addressed a desire for a universal sperm banking tool for adolescents. “Is there a decision tool out there for males? Because I would definitely be interested in looking at that. We don’t have that, but if there is a decision tool out there for males, that would be incredible.” Participants did their best with the materials they had available, but discussed the challenges of providing accurate, uniform information to families. “In general I struggle with that there’s not a universal tool…just some place to go as a provider, or mostly for families to direct them.”

Clinician education and buy-in

Participants extensively discussed the need for more education and agreement about the importance of providing fertility counseling to adolescents newly diagnosed with cancer. One participant stated, “We have a lot of providers, but some of them are not comfortable having that conversation. They forget it’s a topic of discussion when you talk about chemo and fertility.” Some participants felt that clinicians were educated on the implications of treatment for fertility but were not prioritizing fertility discussions. “I really think trying to get like the provider support, whether it’s an NP or PA or a doctor that’s going in and having these conversations with the patients, getting everyone to realize this needs to be on your checklist of things that you decide and discuss on that first visit, even though they’re so overwhelmed. It really needs to be addressed.”

Discussion

This study highlights the wide variability in processes related to fertility counseling and sperm banking across pediatric cancer centers and a notable lack of resources. This cohort of clinicians received prior Oncofertility communication training and reported high levels of confidence in fertility counseling, suggesting a relatively high level of commitment to Oncofertility among these participants and their institutions. Yet, they still identified several barriers to banking. This underscores the multitude of factors—at the system, clinician, family, and individual levels—that must be considered to increase adolescent sperm banking rates before cancer treatment.

Published guidelines state fertility consults should occur prior to cancer treatment and should include information about risk of fertility impairment [6, 7]. Details should also be provided about FP options (e.g., costs, logistics), with a plan to facilitate sperm banking for pubertal males. Focus group participants reported structural barriers to implementing this recommendation in the clinical context: (1) variability in processes for initiating pre-treatment consults, (2) lack of prioritization by oncologists, (3) gaps in assessing puberty and sexual experience, (4) inadequate staffing to complete consults, (5) high out-of-pocket costs of FP, and (6) difficulty accessing sperm banks given off-site locations and limited hours. These data are consistent with barriers reported in a recent national survey, suggesting reasons why pre-treatment banking does not consistently occur [12, 13], and that Oncofertility training for clinicians is beneficial [22, 23], but insufficient. Qualitative data across themes (processes, facilitators, and opportunities for improvement) can inform better system level strategies for Oncofertility care delivery, such as automating fertility consults, incorporating FP in established research protocols to standardize counseling and offset costs, increasing staffing, and creating dedicated spaces within their institutions where banking could occur (Fig. 1).

In addition to structural barriers, this study explored fertility-related communication and decision-making support for adolescent males newly diagnosed with cancer. Prior research examining predictors of adolescent sperm banking has highlighted the influence of clinician and parent recommendation [18]; demonstrated that oncologists and parents experience difficulty discussing this topic [14, 19, 27]; and emphasized the need for Oncofertility training and family-centered decision tools [27–29]. By using a mixed-methods design, we were able to elucidate these topics in depth among a cohort of clinicians, who have received this specialized training and also reported feeling confident in providing fertility counseling to adolescents with cancer. Furthermore, these data demonstrate that although there is a need for Oncofertility training [27], this training is insufficient to improve FP rates without addressing other real-world barriers that exist in the contemporary landscape in pediatric cancer centers. Furthermore, some procedures that have increased access to care (e.g., telemedicine) may be creating other downstream challenges that need to be addressed, (i.e., inability to assess pubertal stage remotely).

We found one-third of survey participants endorsed using decision tools in their population, but follow-up focus group data indicated family-centered adolescent sperm banking tools were not widely available. Rather, educational materials and brochures have been created at individual sites and/or sperm banks. All focus group participants reported including both adolescents and caregivers in fertility consults, but many noted developmental challenges in discussing sperm banking with adolescents given the short time frame before cancer treatment. Participants reflected on experiences where adolescents and parents disagreed on the banking decision and/or where cultural practices made the discussions more complex. Along these lines, recent research highlights that parents are often unaware of their sons’ fertility-related perspectives, with an association between parent-adolescent concordance and sperm banking attempts [30]. With the goal of facilitating shared decision-making and preventing future regret, both the quantitative and qualitative findings in this study suggest using a standardized yet tailored (based on the family’s values), family-centered decision tool to provide guidance and support. Recent research shows an increase in pre-treatment sperm banking attempts at a single site [31], but larger studies have yet to examine effectiveness and/or implementation of formal decision tools.

These findings must be interpreted in the context of several limitations. All data were obtained from ECHO learners, who are likely more skilled in providing Oncofertility care than those who have not participated in such trainings. Additionally, only ~one-third of eligible learners completed the survey. Furthermore, focus group participants were all White and mostly female, limiting the generalizability of these findings. Research has demonstrated racial/ethnic disparities in FP rates (albeit primarily examined in women) [32–34], highlighting a need for exploring more diverse perspectives among both patients/families and clinicians. Finally, given the interdisciplinary nature of the Oncofertility field, the disciplines included in the focus groups may not fully represent those leading Oncofertility discussions across all centers/countries [35]. Despite these limitations, this mixed-methods study makes a novel and impactful contribution by highlighting common structural and psychosocial barriers to banking and informing future family-centered communication/decision-making FP interventions for the male adolescent cancer population.

Conclusion

While national guidelines endorse the importance of informing individuals with newly diagnosed cancer about infertility risks and referrals for preservation [6, 7], uptake remains low due to a multitude of structural and psychosocial barriers. This paper highlights several opportunities and strategies for improvement, from the perspective of clinicians who have received Oncofertility communication training. These data can be used to mitigate barriers and inform development and implementation of family-centered decision-making tools, with the ultimate goal of improving reproductive and psychosocial outcomes.

Author contributions

LN, GPQ, CAG, SHO, and STV contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by LN, SML, DJ, and GPQ. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LN, SML, DJ, and GPQ. All authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by NIH/NCI-K08CA237338 (PI Nahata) and 2R25CA142519-11 (MPIs Quinn and Vadaparampil) and NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

Data Availability

Deidentified survey data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was deemed non-human subjects by the New York University Institutional Review Board.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, et al. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2018. National Cancer Institute; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudson MM, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. Jama. 2013;309(22):2371–2381. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green DM, et al. Fertility of male survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):332. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.9037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armuand GM, et al. Desire for children, difficulties achieving a pregnancy, and infertility distress 3 to 7 years after cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2805–2812. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2279-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulder RL, et al. Fertility preservation for male patients with childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer: recommendations from the PanCareLIFE Consortium and the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(2):e57–e67. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30582-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(6):1022–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapadia A, et al. An institutional assessment of sperm cryospreservation and fertility counselling in pubertal male cancer survivors. J Pediatr Urol. 2020;16(4):474. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.05.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saraf AJ, et al. Examining predictors and outcomes of fertility consults among children, adolescents, and young adults with cancer. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 2018;65(12):e27409. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel V, et al. Recollection of fertility discussion in adolescent and young adult oncology patients: a single-institution study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2020;9(1):72–77. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2019.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein DM, et al. Fertility preservation preferences and perspectives among adult male survivors of pediatric cancer and their parents. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2014;3(2):75–82. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2014.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frederick NN, et al. Infrastructure of fertility preservation services for pediatric cancer patients: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(3):e325–e333. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frederick NN, et al. Fertility preservation practices at pediatric oncology institutions in the United States: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. JCO Oncol Pract. 2023;19(4):e550–e558. doi: 10.1200/OP.22.00349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nahata L, Gerhardt CA, Quinn GP. Fertility preservation discussions with male adolescents with cancer and their parents: “ultimately, it’s his decision”. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):799–800. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayden RP, Kashanian JA. Facing a cancer diagnosis: empowering parents to speak with adolescents about sperm banking. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):957–958. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan TL, et al. Recruiting families and children newly diagnosed with cancer for behavioral research: important considerations and successful strategies. Psychooncology. 2019;28(4):928–930. doi: 10.1002/pon.5012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clinicians. CMS.gov, Accessed July 24, 2023; https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/QMY-Clinicians

- 18.Klosky JL, et al. Prevalence and predictors of sperm banking in adolescents newly diagnosed with cancer: examination of adolescent, parent, and provider factors influencing fertility preservation outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(34):3830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.4767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olsavsky AL, et al. Family communication about fertility preservation in adolescent males newly diagnosed with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(7):e28978. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuchs A, et al. Pediatric oncology providers’ attitudes and practice patterns regarding fertility preservation in adolescent male cancer patients. J Pediatr Hematol/Oncol. 2016;38(2):118. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vadaparampil ST, Hutchins NM, Quinn GP. Reproductive health in the adolescent and young adult cancer patient: an innovative training program for oncology nurses. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28:197–208. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0435-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vadaparampil ST, et al. ENRICH: a promising oncology nurse training program to implement ASCO clinical practice guidelines on fertility for AYA cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(11):1907–1910. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quinn GP, et al. Impact of a web-based reproductive health training program: ENRICH (Educating Nurses about Reproductive Issues in Cancer Healthcare) Psycho-oncology. 2019;28(5):1096–1101. doi: 10.1002/pon.5063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pecoriello J, et al. Evolution and growth of the ECHO (Enriching Communication skills for Health professionals in Oncofertility) program: a 5-year study in the training of oncofertility professionals. J Cancer Surviv. 2022. 10.1007/s11764-021-01139-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Barrett F, et al. Perspectives surrounding fertility preservation and posthumous reproduction for adolescent and young adults with terminal cancer: survey of allied health professionals. Cancer Med. 2023;12(5):6129–6138. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social problems. 1965;12(4):436–445. doi: 10.2307/798843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panagiotopoulou N, et al. Barriers and facilitators towards fertility preservation care for cancer patients: a meta-synthesis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(1):e12428. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flynn JS, et al. Parent recommendation to bank sperm among at-risk adolescent and young adult males with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(10):e28217. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klosky JL, et al. Parental influences on sperm banking attempts among adolescent males newly diagnosed with cancer. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nahata L, et al. Parent–adolescent concordance regarding fertility perspectives and sperm banking attempts in adolescent males with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2021;46(10):1149–1158. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsab069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nahata L, et al. Impact of a novel family-centered values clarification tool on adolescent sperm banking attempts at the time of a new cancer diagnosis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:1561–1569. doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02092-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Letourneau JM, et al. Racial, socioeconomic, and demographic disparities in access to fertility preservation in young women diagnosed with cancer. Cancer. 2012;118(18):4579–4588. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voigt PE, et al. Equal oppurtunity for all? An analysis of race and ethnicity in fertility preservation in New York City. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:3095–3102. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01980-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canzona MR, et al. Fertility preservation decisional turning points for adolescents and young adults with cancer: exploring alignment and divergence by race and ethnicity. JCO Oncol Pract. 2023; 10.1200/op.22.00613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Woodruff TK, et al. A view from the past into our collective future: the oncofertility consortium visit statemnet. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:3–15. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01983-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified survey data are available upon request to the corresponding author.