Abstract

Background

Overweight and obesity (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2 and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, respectively are increasingly common among women of reproductive age. Overweight and obesity are known to be associated with many adverse health conditions in the preconception period, during pregnancy and during the labour and postpartum period. There are no current guidelines to suggest which preconception health programs and interventions are of benefit to these women and their infants. It is important to evaluate the available evidence to establish which preconception interventions are of value to this population of women.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of preconception health programs and interventions for improving pregnancy outcomes in overweight and obese women.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (31 December 2014) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (including those using a cluster‐randomised design), comparing health programs and interventions with routine care in women of reproductive age and a BMI greater then or equal to 25 kg/m2. Studies published in abstract form only, were not eligible for inclusion. Quasi‐randomised trials or randomised trials using a cross‐over design were not eligible for inclusion in this review. The intervention in such studies would involve an assessment of preconception health and lead to an individualised preconception program addressing any areas of concern for that particular woman.

Preconception interventions could involve any or all of: provision of specific information, screening for and treating obesity‐related health problems, customised or general dietary and exercise advice, medical or surgical interventions. Medical interventions may include treatment of pre‐existing hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance or sleep apnoea. Surgical interventions may include interventions such as bariatric surgery. The comparator was prespecified to be standard preconception advice or no advice/interventions.

Data collection and analysis

We identified no studies that met the inclusion criteria for this review. The search identified one study (published in four trial reports) which was independently assessed by two review authors and subsequently excluded.

Main results

There are no included trials.

Authors' conclusions

We found no randomised controlled trials that assessed the effect of preconception health programs and interventions in overweight and obese women with the aim of improving pregnancy outcomes. Until the effectiveness of preconception health programs and interventions can be established, no practice recommendations can be made. Further research is required in this area.

Plain language summary

Preconception health programs and interventions for women who are overweight or obese to improve pregnancy outcomes for the woman and her infant

Being overweight or obese, or having a high body weight for one's height, is becoming increasingly common among women of reproductive age. General health conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, sleep apnoea (pauses or reduced breathing during sleep), and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which can cause reduced fertility or failure to achieve pregnancy, are associated with being overweight or obese. During pregnancy, overweight women are at increased risk of sugar intolerance (gestational diabetes), pregnancy‐related high blood pressure, losing a pregnancy (miscarriage), birth before some 40 weeks (preterm birth) and congenital birth defects such as neural tube and heart defects, and gastrointestinal malformations. Women who are overweight or obese are also at a higher risk of complications during labour including heavy blood loss after giving birth. Current guidelines about which preconception health programs or interventions are of benefit to reduce these adverse health outcomes are needed for overweight and obese women.

This Cochrane review aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of preconception health programs and interventions, however no randomised controlled trials were found. We recommend that further research is conducted in this area so that the effectiveness of preconception health programs and interventions can be established specifically for overweight and obese women. Programs can provide information, screening for and treating obesity‐related health problems, dietary and exercise advice and medical or surgical interventions, depending on the resources available and the individual needs of the woman.

Background

Description of the condition

Overweight and obesity (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2 and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, respectively (WHO 2013) are common among women of reproductive age (Callaway 2006; Vahration 2009), with the incidence of high BMI increasing over time (ABS 2011). There are many known associations between overweight and obesity and adverse outcomes for both the woman and her infant during pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period.

Overweight and obesity are known to be associated with many adverse general health conditions such as hypertension (Kurukulasuriya 2011), diabetes (Reaven 2011) and PCOS (polycystic ovary syndrome) (Gambineri 2002). PCOS is a common cause of decreased fertility (also known as infertility/subfertility, or failure to achieve pregnancy within a specific timeframe) in women of reproductive ages (Hull 1987), and is associated with several late pregnancy complications (Bjercke 2002). Whilst overweight and obesity are associated with reduced fertility, the specific preconception management of women with known subfertility will not be discussed in this review as it is discussed in another Cochrane review (Anderson 2010).

During pregnancy overweight or obese women are at increased risk of experiencing a miscarriage (Frederick 2013), developing impaired glucose tolerance (decreased ability to control blood glucose levels) (Frederick 2013), sleep apnoea (a sleep disorder involving pauses in breathing) (Frederick 2013), pre‐eclampsia (pregnancy‐related hypertension), chorioamnionitis (infection of the amniotic fluid surrounding the infant or of the membranes) (Raatikainen 2006), and preterm birth (Catalano 2006; Galtier 2008). There are additional risks of complications during labour and birth, including the need for induction of labour or caesarean birth (Catalano 2006), and also the risk of postpartum haemorrhage. Throughout the pregnancy and after the birth, overweight or obese women are also at higher risk of venous thromboembolism (a blood clot in the veins that can then break off and spread to other parts of the body) (Gray 2012).

Infants born to women who are overweight or obese are at increased risk of congenital abnormalities such as neural tube defects (a defect in the formation of the brain and/or spinal cord), structural heart defects and gastrointestinal malformations (Waller 2007). The infant is also more likely to have high birthweight (macrosomia) (Catalano 2006), which can result in increased risk of birth trauma and maternal complications (Oral 2001).

Following the birth, maternal obesity has been recognised as a risk factor for decreased initiation and duration of breastfeeding (Li 2003), and of the child themselves being obese later in life (Birbilis 2012).

Description of the intervention

Preconception care is a collection of health interventions designed to best prepare and improve the woman’s physical and emotional health to increase the likelihood of a successful pregnancy and healthy infant (Whitworth 2009). It has many components and can be implemented in many ways depending on the resources available and the individual needs of the woman.

Preconception care for the general population may include advice about alcohol intake and smoking, as well as exercise, nutritional supplementation and immunisations. Less attention however, has been paid to the needs of specific subgroups of women, including women who are overweight or obese, who may benefit from specific and targeted interventions. This may include diet and lifestyle advice, active management of co‐morbid medical conditions or bariatric surgery.

How the intervention might work

Women who are overweight or obese may benefit from a structured approach to preconception counselling, aiming to reduce the risks of the specific overweight and obesity complications outlined above. This approach may involve a preconception assessment of the woman's health, which could be followed by a directed and individualised plan to optimise the woman's health. This approach may include the following.

Education

Education is an important part of preconception counselling. Informing women about the risks associated with overweight and obesity during pregnancy may allow them to make informed decisions about their pregnancy plans and timing of conception.

Preconception screening for health conditions associated with obesity

Obesity prior to pregnancy is associated with many conditions including hypertension (high blood pressure) (Kurukulasuriya 2011), impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes (Reaven 2011) and sleep apnoea (Mehra 2008). Many of these conditions can be exacerbated by pregnancy. By screening for these conditions prior to conception there is the opportunity to optimise the woman's health by treating these co‐morbid conditions prior to conception. For example, for some women, it might be advised to await stabilisation of blood pressure or some degree of weight loss prior to conceiving.

Management of sleep apnoea

Sleep apnoea during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of developing hypertensive disease of pregnancy and gestational diabetes (Priscilla 2013). Intensive lifestyle interventions have been shown, in the general population, to reduce apnoea‐associated complications and improve rates of remission (Kuna 2013). The effect of preconception interventions for sleep apnoea and the outcomes for subsequent pregnancies has not been established.

Nutritional supplementation

Folic acid supplementation is well established as an important component of preconception care in the general population, reducing the incidence of neural tube defects. Women who are overweight or obese are reported to have lower serum folate levels (Tinker 2012), although there is no evidence to suggest that higher folate supplementation doses are beneficial. Women who are overweight or obese are reported to be less likely to take supplements during pregnancy, when compared with the general population (Case 2007).

Physical activity

Regular physical activity is recommended for all individuals as part of a healthy lifestyle. There are many benefits of regular physical activity including improved cardiovascular health (Metkus 2010) and improved bone density (Howe 2011). Moderate physical exercise has been shown to be safe (Larsson 2005), and has many benefits before and during pregnancy. Women who engage in regular physical activity in the preconception period are more likely to continue this during pregnancy.

General improvement of nutrition and health

Assessment of the overall nutrition of overweight or obese women is important as it provides the building blocks for the infant. While under‐nutrition is well recognised as being problematic for the pregnancy and future of the infant, over‐nutrition also has implications. Infants born to women who are overweight or obese are at greater risk of having a high birthweight, which predisposes to future obesity and metabolic syndrome (Desai 2013). Not only is weight itself important, but also the quality of the diet.

Many other factors affect body weight including genetics, psychological state, caloric intake and energy output. Previous Cochrane reviews have demonstrated that weight reduction is achievable in individuals who are overweight or obese with the use of low glycaemic index diets and psychological interventions, especially when these interventions are combined with exercise (Shaw 2009; Thomas 2009). Weight reduction as part of a pre‐pregnancy plan may assist in lowering BMI and potentially decreasing risk during pregnancy. For particular groups there may be an indication for surgical intervention to assist in weight management, and this includes gastric bypass surgery and gastric balloon insertion.

Surgical interventions

Bariatric surgery, regardless of whether restrictive (reducing the volume of food that can be consumed), or malabsorptive (reducing the area in the gastrointestinal system available to absorb nutrients), has been shown to have positive effects on many of the complications of obesity, including, diabetes, sleep apnoea, dyslipidaemia and hypertension in the general population (Noria 2013). Some studies have shown improved pregnancy outcomes in obese women who have undergone bariatric surgery particularly with regards to reducing the burden of hypertensive disease of pregnancy (Bennett 2010) and diabetes (Weintraub 2008). Unfortunately, some studies have also shown increased risk of nutritional deficiencies following bariatric surgery (Bebber 2011). Surgical interventions for weight control may be indicated in some groups of women who may be at higher risk of hypertensive complications who are resistant to other interventions.

Other Cochrane reviews in this area

There are Cochrane reviews already in place that address issues in this general area. We have listed them here and described differences between the existing reviews and our review.

Some address care specifically before during or after pregnancy.

The review by Amorim Adegboye et al (Diet or exercise, or both, for weight reduction in women after childbirth (Amorim Adegboye 2013)) includes only breastfeeding women in the postpartum period, and only includes outcomes for the mother and current child, not related to pregnancy.

The review by Furber et al (Antenatal interventions for reducing weight in obese women for improving pregnancy outcome (Furber 2013)) looks at weight control in the antenatal period. Our current review is assessing preconception interventions.

A number of reviews in particular address different aspects of preconception care.

A review by Tieu et al in 2010 entitled Preconception care for diabetic women for improving maternal and infant health (Tieu 2010) includes women with pre‐existing diabetes, and this group has been specifically excluded from this review.

The review by Whitworth and colleagues (Routine pre‐pregnancy health promotion for improving pregnancy outcomes (Whitworth 2009)) excludes trials where interventions are aimed specifically at women with established medical, obstetric or genetic risks or already receiving treatment as part of programmes for high‐risk groups and examines routine health promotion for all women.

In contrast, the review by Anderson and colleagues (Preconception lifestyle advice for people with subfertility (Anderson 2010)) is specific to those women seeking fertility treatment and this group has been excluded from this review.

Another review by Tieu et al (Interconception care for women with a history of gestational diabetes for improving maternal and infant outcomes (Tieu 2013)) only included women with a history of gestational diabetes. Our review looks at women with a larger range of preconception conditions, and specifically those with a BMI in the overweight or obese range.

Why it is important to do this review

Overweight and obesity are increasingly common among women of reproductive age and are associated with adverse outcomes for women and their infants. There is currently no evidence to indicate whether directed preconception health programs are of benefit, and if so, what they should include. It is important to determine which interventions, if any, are of benefit to women who are overweight or obese and how they should be implemented to improve pregnancy outcomes.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of a directed intervention or program of preconception care for women who are overweight or obese, compared with no specific preconception care or routine preconception care on pregnancy outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We had planned to include randomised controlled trials, excluding those only published as an abstract. Cluster‐randomised trials would have been eligible for inclusion. Quasi‐randomised trials and trials using a cross‐over design were not eligible for inclusion. The intervention in these studies would involve an assessment of preconception health and lead to an individualised preconception program addressing any areas of concern for that particular woman.

Types of participants

Women who are not pregnant, but of reproductive age (as defined by trial authors), who have a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 25 kg/m2. Women with existing type 2 diabetes and women with subfertility seeking treatment will be excluded from this review.

Types of interventions

Preconception interventions that involve any or all of: provision of specific information, screening for and treating obesity‐related health problems, customised or general dietary and exercise advice, medical or surgical interventions. Medical interventions may include treatment of pre‐existing hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance or sleep apnoea. Surgical interventions may include interventions such as bariatric surgery.

The comparator was prespecified to be standard preconception advice or no advice/interventions.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary infant outcome for this review is large‐for‐gestational‐age infants (greater than 90th percentile for infant sex and gestational age).

Secondary outcomes

Infant

Perinatal death (stillbirth and neonatal death)

Infant birthweight greater than 4500 g

Infant birthweight less than 2500 g

Admission to neonatal intensive care unit

Admission to the neonatal nursery

Length of hospital stay for the neonate

Birth trauma (nerve palsy or fracture)

Shoulder dystocia

Childhood

BMI

Childhood neurodevelopment (as defined by trial authors)

Childhood atopy/allergy

Maternal: pre‐pregnancy

Satisfaction with care (as defined by trial authors)

Quality of life (as defined by trial authors)

Physical health (as defined by trial authors)

Emotional health (as defined by trial authors)

Time to conception

Use of assisted reproductive technology

Maternal: pregnancy

Need for antenatal hospital stay

Antepartum haemorrhage requiring hospitalisation

Gestational diabetes (as defined by trial authors)

Hypertensive disease of pregnancy

Preterm birth before 37 weeks' gestation

Gestational weight gain

Need for induction of labour

Caesarean section

Perineal trauma

Postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by trial authors)

Postnatal length of stay

Thromboembolic disease

Breastfeeding at six months postpartum

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (31 December 2014).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

In addition, we searched reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors (Rosalie Grivell and Nicolle Opray) independently assessed the one study that was identified through the search strategy for inclusion. We resolved any disagreement through discussion. In this version of the review we were unable to identify any studies for inclusion. In updates of the review if we do identify trials which meet our inclusion criteria we will use the methods set out in Appendix 1 to carry out data extraction, assess bias in included studies and analyse findings.

Results

Description of studies

The search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register retrieved four reports from one study. This study was excluded because it did not meet our eligibility criteria as it reported data for all BMI categories combined and individual categories could not be separated out for data extraction purposes.

Results of the search

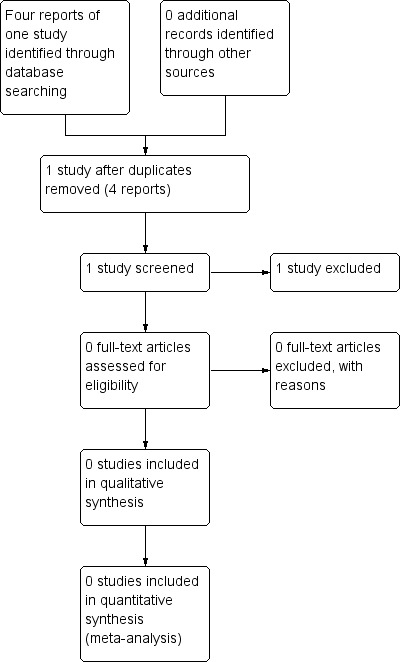

The search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register retrieved one study (Velott 2008) (published in four reports). See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

No studies met the eligibility criteria for inclusion.

Excluded studies

The one identified study (Velott 2008) was a randomised controlled study of preconception interventions in women of all BMI categories. It did not focus only on overweight or obese women and it was not possible to extract data by BMI category (by excluding the normal BMI group) as the data were not reported by BMI category. We therefore excluded the trial.

Risk of bias in included studies

There are no included studies in this review.

Effects of interventions

No studies met the eligibility criteria for inclusion.

Discussion

Being overweight or obese during pregnancy is associated with many adverse outcomes such as miscarriage, impaired glucose tolerance and sleep apnoea (Frederick 2013). However, there is no evidence from randomised controlled trials to guide which, if any, preconception interventions could have a positive and meaningful impact on pregnancy outcomes. There are many ways that preconception interventions could be designed and targeted but there is little evidence to support any individual model and no trials could be found to support any potential benefit of preconception interventions on pregnancy outcomes, A similar review (Whitworth 2009) looking at pre‐conception health promotion in the general population was also unable to show strong benefit to preconception health promotion.

Summary of main results

We identified no relevant randomised controlled trials that were eligible for this review.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We identified no relevant randomised controlled trials that were eligible for this review.

Quality of the evidence

We identified no relevant randomised controlled trials that were eligible for this review.

Potential biases in the review process

We identified no relevant randomised controlled trials that were eligible for this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

As no relevant eligible trials investigating the effect of preconception health interventions and programs on pregnancy outcomes were identified, we are unable to draw any reliable conclusions about the effectiveness of these programs and interventions. Consequently, we are unable to identify any agreements or disagreements with other studies or reviews.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

As there is no current evidence from randomised controlled trials to support which, if any, preconception interventions are likely to have a beneficial impact on pregnancy outcomes for overweight and obese women, no conclusions to inform practice can be made at this time.

Implications for research.

The absence of randomised controlled trials relating to preconception interventions for overweight and obese women to improve pregnancy outcomes reveals an area where further research is required. With increasing numbers of women of reproductive age becoming overweight or obese (Callaway 2006; Vahration 2009), more understanding is required about how to best approach and intervene in the preconception period.

Acknowledgements

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), members of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methods of data collection and analysis to be used in future updates of this review

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors will independently assess for inclusion all the potential studies we identify as a result of the search strategy. We will resolve any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we will consult a third person.

Data extraction and management

We will design a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors will extract the data using the agreed form. We will resolve discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we will consult a third person. We will enter data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and check for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above is unclear, we will attempt to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors will independently assess risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We will resolve any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We will describe for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We will assess the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We will describe for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and will assess whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We will assess the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We will describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We will consider that studies are at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judge that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We will assess blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We will assess the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We will describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We will assess blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We will assess methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We will describe for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We will state whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information is reported, or can be supplied by the trial authors, we will re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertake.

We will assess methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups, or maximum of 20% missing data);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We will describe for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We will assess the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We will describe for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We will assess whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We will make explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we will assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we consider it is likely to impact on the findings. We will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ see Sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we will present results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we will use the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We will include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook [Section 16.3.4] using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Multi‐armed trials

We will include multi‐armed trials and attempt to overcome potential unit of analysis errors by combining groups to create a single pairwise comparison or select one pair of interventions and exclude the others.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we will note levels of attrition. We will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we will carry out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we will attempt to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants will be analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial will be the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We will assess statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We will regard heterogeneity as substantial if an I² is greater than 30% and either a T² is greater than zero, or there is a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We will carry out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We will use fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it is reasonable to assume that studies are estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials are examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. If there is clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity is detected, we will use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials is considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary will be treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we will not combine trials.

If we use random‐effects analyses, the results will be presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identify substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We will consider whether an overall summary is meaningful, and if it is, use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We plan to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

Women who are overweight versus those who are obese.

Subgroup analysis will be restricted to the review's primary outcome.

We will assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We will report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the χ2 statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We plan to carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effects of trial quality as assessed by concealment of allocation or missing data for a particular outcome on the summary statistic. We plan to exclude studies of poor quality from the analysis in order to assess for any substantive difference to the overall result. Sensitivity analysis will be restricted to the primary outcome.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Velott 2008 | Randomised controlled trial of preconception intervention in women of all BMI categories. It is not possible to extract data by BMI category (by excluding the normal BMI group) as data not reported by BMI category. |

BMI: body mass index

Differences between protocol and review

We have edited the childhood secondary outcome 'BMI at three years of age' to 'BMI' to allow more flexibility if trials are identified for inclusion at the next update.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth standard search methods text has been updated.

Contributions of authors

Nicolle Opray is the contact person and guarantor for the review and designed the review and wrote the protocol and review, with review of content by Rosalie Grivell, Andrea Deussen and Jodie Dodd.

Declarations of interest

Nicolle Opray and Andrea Deussen: none known.

Jodie Dodd and Rosalie Grivell are planning to carry out a randomised controlled trial that may be eligible for inclusion in this review in the future. All decisions relating to any such study (i.e. assessment for inclusion and trial quality, data extraction) will be carried out by other members of the review team who are not directly involved in the study.

New

References

References to studies excluded from this review

Velott 2008 {published data only}

- Downs DS, Feinberg M, Hillemeier MM, Weisman CS, Chase GA, Chuang CH, et al. Design of the Central Pennsylvania Women's Health Study (CePAWHS) strong healthy women intervention: improving preconceptional health. Maternal and Child Health Journal 2009;13(1):18‐28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillemeier MM, Downs DS, Feinberg ME, Weisman CS, Chuang CH, Parrott R, et al. Improving women's preconceptional health: findings from a randomized trial of the Strong Healthy Women intervention in the Central Pennsylvania women's health study. Womens Health Issues 2008;18(6 Suppl):S87‐96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velott DL, Baker SA, Hillemeier MM, Weisman CS. Participant recruitment to a randomized trial of a community‐based behavioral intervention for pre‐ and interconceptional women findings from the Central Pennsylvania Women's Health Study. Womens Health Issues 2008;18(3):217‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman CS, Hillemeier MM, Downs DS, Feinberg ME, Chuang CH, Botti JJ, et al. Improving women's preconceptional health: long‐term effects of the strong healthy women behavior change intervention in the Central Pennsylvania Women's Health Study. Women's Health Issues 2011;21(4):265‐71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

ABS 2011

- Overweight and Obesity in Adults in Australia: A Snapshot, 2007–08. Australian Bureau of Statistics (http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/73E036F555CE4C11CA25789C0023DAF8?opendocument) [accessed 2 August 2014] 2011.

Amorim Adegboye 2013

- Amorim Adegboye AR, Linne YM. Diet or exercise, or both, for weight reduction in women after childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 7. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005627.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Anderson 2010

- Anderson K, Norman RJ, Middleton P. Preconception lifestyle advice for people with subfertility. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008189.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bebber 2011

- Bebber FE, Rizzolli J, Casagrande DS, Rodrigues MT, Padoin AV, Mottin CC, et al. Pregnancy after bariatric surgery: 39 pregnancies follow‐up in a multidisciplinary team. Obesity Surgery 2011;21(10):1546‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bennett 2010

- Bennett WL, Gilson MM, Jamshidi R, Burke AE, Segal JB, Steele KL, et al. Impact of bariatric surgery on hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: retrospective analysis of insurance claims data. BMJ 2010;340:c1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Birbilis 2012

Bjercke 2002

- Bjercke P, Dale PO, Tanbo T, Storeng R, Ertzeid G, Åbyholm T. Impact of insulin resistance on pregnancy complications and outcome in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 2002;54:94‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Callaway 2006

- Callaway LK, Prins JB, Chang AM, McIntyre HD. The prevalence and impact of overweight and obesity in an Australian obstetric population. Medical Journal of Australia 2006;184(2):56‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Case 2007

- Case AP, Ramadhani TA, Canfield MA, Beverly L, Wood R. Folic acid supplementation among diabetic, overweight, or obese women of childbearing age. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 2007;36(4):335‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Catalano 2006

Desai 2013

- Desai M, Beall M, Ross MG. Developmental origins of obesity: programmed adipogenesis. Current Diabetes Reports 2013;13(1):27‐33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Frederick 2013

Furber 2013

- Furber CM, McGowan L, Bower P, Kontopantelis E, Quenby S, Lavender T. Antenatal interventions for reducing weight in obese women for improving pregnancy outcome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009334.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Galtier 2008

- Galtier F, Raingeard I, Renard E, Boulot P, Bringer J. Optimizing the outcome of pregnancy in obese women: from pregestational to long‐term management. Diabetes and Metabolism 2008;34(1):19‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gambineri 2002

- Gambineri A, Pelusi C, Vicennati V, Pagotto U, Pasquali R. Obesity and the polycystic ovary syndrome. International Journal of Obesity 2002;26:883‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gray 2012

- Gray G, Nelson‐Piercy C. Thromboembolic disorders in obstetrics. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2012;26(1):53‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Howe 2011

- Howe TE, Shea B, Dawson LJ, Downie F, Murray A, Ross C, et al. Exercise for preventing and treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 7. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000333] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hull 1987

- Hull MGR. Epidemiology of infertility and polycystic ovarian disease: endocrinological and demographic studies. Gynecological Endocrinology 1987;1:235‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kuna 2013

- Kuna ST, Reboussin DM, Borradaile KE, Sanders MH, Millman RP, Zammit G, et al. Long‐term effect of weight loss on obstructive sleep apnea severity in obese patients with Type 2 diabetes. Sleep 2013;36(5):641‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kurukulasuriya 2011

- Kurukulasuriya LR, Stas S, Lastra G, Manrique C, Sowers JR. Hypertension in obesity. Medical Clinics of North America 2011;95(5):903‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Larsson 2005

- Larsson L, Lindqvist PG. Low‐impact exercise during pregnancy‐‐a study of safety. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2005;84(1):34‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Li 2003

- Li R, Jewell S, Grummer‐Strawn L. Maternal obesity and breast‐feeding practices. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2003;77(4):931‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mehra 2008

- Merah R, Redline S. Sleep apnea: a proinflammatory disorder that coaggregates with obesity. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2008;121(5):1096‐102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Metkus 2010

- Metkus TS Jr, Baughman KL, Thompson PD. Exercise prescription and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2010;121(23):2601‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Noria 2013

- Noria SF, Grantcharov T. Biological effects of bariatric surgery on obesity‐related comorbidities. Canadian Journal of Surgery 2013;56:47‐57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Oral 2001

- Oral E, Cağdas A, Gezer A, Kaleli S, Aydinli K, Ocer F. Perinatal and maternal outcomes of fetal macrosomia. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2001;99(2):167‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Priscilla 2013

- Priscilla M, Nodine CNM, Matthews EE. Common sleep disorders: management strategies and pregnancy outcomes. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health 2013;58(4):368‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Raatikainen 2006

- Raatikainen K, Heiskanen N, Heinonen S. Transition from overweight to obesity worsens pregnancy outcome in a BMI‐dependent manner. Obesity 2006;14(1):165‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reaven 2011

- Reaven GM. Insulin resistance: the link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Medical Clinics of North America 2011;95(5):875‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2014 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

Shaw 2009

- Shaw K, O'Rourke P, Mar C, Kenardy J. Psychological interventions for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003818] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thomas 2009

- Thomas DE, Elliott EJ, Baur L. Low glycaemic index or low glycaemic load diets for overweight and obesity. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005105] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tieu 2010

- Tieu J, Middleton P, Crowther CA. Preconception care for diabetic women for improving maternal and infant health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 12. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007776.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tieu 2013

- Tieu J, Bain E, Middleton P, Crowther CA. Interconception care for women with a history of gestational diabetes for improving maternal and infant outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 6. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010211.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tinker 2012

- Tinker SC, Hamner HC, Berry RJ, Bailey LB, Pfeiffer CM. Does obesity modify the association of supplemental folic acid with folate status among nonpregnant women of childbearing age in the United States?. Birth Defects Research. PArt A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology 2012;94(10):749‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vahration 2009

- Vahratian A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of childbearing age: results from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Maternal and Child Health Journal 2009;13(2):268‐73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Waller 2007

- Waller DK, Shaw GM, Rasmussen SA, Hobbs CA, Canfield MA, Siega‐Riz AM, et al. Prepregnancy obesity as a risk factor for structural birth defects. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 2007;161(8):745‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Weintraub 2008

- Weintraub AY, Levy A, Levi I, Mazor M, Wiznitzer A, Sheiner E. Effect of bariatric surgery on pregnancy outcome. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2008;103(3):246‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Whitworth 2009

- Whitworth M, Dowswell T. Routine pre‐pregnancy health promotion for improving pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007536.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 2013

- World Health Organization. Overweight and obesity fact sheet N 311. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html [accessed 2013] March 2013.