Abstract

Background

Racial and ethnic disparities in health status are pervasive at all stages of the life cycle. One approach to reducing health disparities involves mobilizing community coalitions that include representatives of target populations to plan and implement interventions for community level change. A systematic examination of coalition‐led interventions is needed to inform decision making about the use of community coalition models.

Objectives

To assess effects of community coalition‐driven interventions in improving health status or reducing health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PsycINFO, Social Science Citation Index, Dissertation Abstracts, System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (SIGLE) (from January 1990 through September 30, 2013), and Global Health Library (from January 1990 through March 31, 2014).

Selection criteria

Cluster‐randomized controlled trials, randomized controlled trials, quasi‐experimental designs, controlled before‐after studies, interrupted time series studies, and prospective controlled cohort studies. Only studies of community coalitions with at least one racial or ethnic minority group representing the target population and at least two community public or private organizations are included. Major outcomes of interest are direct measures of health status, as well as lifestyle factors when evidence indicates that these have an effect on the direct measures performed.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed risk of bias for each study.

Main results

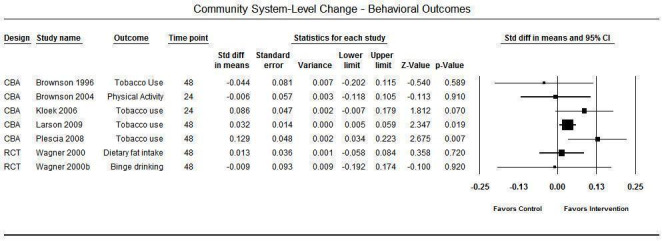

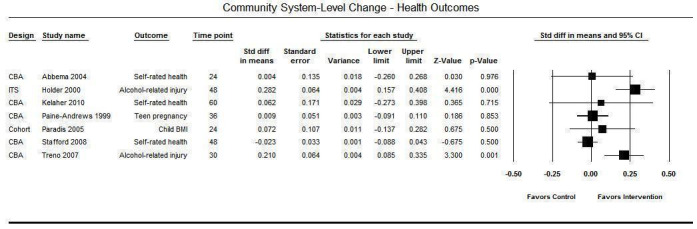

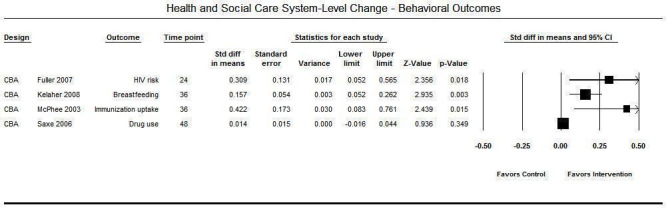

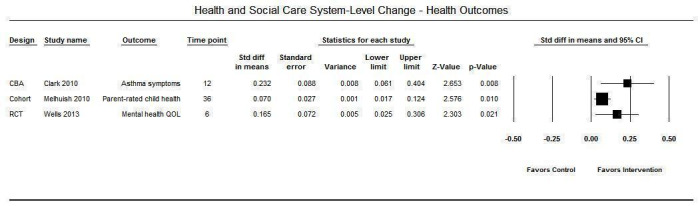

Fifty‐eight community coalition‐driven intervention studies were included. No study was considered to be at low risk of bias. Behavioral change outcomes and health status change outcomes were analyzed separately. Outcomes are grouped by intervention type. Pooled effects across intervention types are not presented because the diverse community coalition‐led intervention studies did not examine the same constructs or relationships, and they used dissimilar methodological designs. Broad‐scale community system level change strategies led to little or no difference in measures of health behavior or health status (very low‐certainty evidence). Broad health and social care system level strategies leds to small beneficial changes in measures of health behavior or health status in large samples of community residents (very low‐certainty evidence). Lay community health outreach worker interventions led to beneficial changes in health behavior measures of moderate magnitude in large samples of community residents (very low‐certainty evidence). Lay community health outreach worker interventions may lead to beneficial changes in health status measures in large samples of community residents; however, results were not consistent across studies (low‐certainty evidence). Group‐based health education led by professional staff resulted in moderate improvement in measures of health behavior (very low‐certainty evidence) or health status (low‐certainty evidence). Adverse outcomes of community coalition‐led interventions were not reported.

Authors' conclusions

Coalition‐led interventions are characterized by connection of multi‐sectoral networks of health and human service providers with ethnic and racial minority communities. These interventions benefit a diverse range of individual health outcomes and behaviors, as well as health and social care delivery systems. Evidence in this review shows that interventions led by community coalitions may connect health and human service providers with ethnic and racial minority communities in ways that benefit individual health outcomes and behaviors, as well as care delivery systems. However, because information on characteristics of the coalitions themselves is insufficient, evidence does not provide an explanation for the underlying mechanisms of beneficial effects. Thus, a definitive answer as to whether a coalition‐led intervention adds extra value to the types of community engagement intervention strategies described in this review remains unattainable.

Plain language summary

Community coalition‐driven interventions to improve health status and reduce disparities in racial and ethnic minority populations

Unequal health status among racial and ethnic minority populations compared with the general population is a worldwide public health problem. Decades of public health interventions have led to little success in reducing inequalities in health among racial and ethnic minorities. One approach to reducing health disparities involves using coalitions that include representatives of minority communities to create supportive community environments for healthy choices and quality of life. This review looked for evidence that interventions driven by community coalitions improve health status or reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations.

This review, which included searches of databases from January 1990 through March 31, 2014, found 58 community coalition‐driven studies, which addressed a wide array of health outcomes and risk behaviors. Only studies of community coalitions with at least one racial or ethnic minority group representing the target population and at least two community‐based public or private organizations were included. This review examined the effects of four types of strategies or interventions used by community coalitions.

Community system‐level change strategies (such as initiatives targeting physical environments like housing, green spaces, neighborhood safety, or regulatory processes and policies) have produced small inconsistent effects; broad health and social care system‐level strategies (such as programs targeting behavior of staff in a health or social care system, accessibility of services, or policies, procedures, and technologies designed to improve quality of care) have had consistently positive small effects; interventions that used lay community health outreach workers or group‐based health education led by professional staff have produced fairly consistent positive effects; and group‐based health education led by peers has had inconsistent effects.

This review shows that interventions led by community coalitions may connect health and human service providers with ethnic and racial minority communities in ways that benefit individual health outcomes and behaviors, as well as care delivery systems. However, to achieve the same levels of health across communities, regardless of race or ethnicity, we need to know specifically how a program does or does not work. This will require better information on how some programs described in this review brought about beneficial change and theresources needed, so they can be replicated. Furthermore, we need better scientific tools to improve our ability to identify effects of programs on whole community systems and to understand the leverage points that, when employed appropriately, shift the distribution of health toward equity.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Community coalition‐driven interventions to reduce health disparities in racial and ethnic minority populations | ||||

|

Population: racial and ethnic minority populations including adults and children Setting: community‐based settings, primarily in urban areas in high‐income countries Interventions: (1) broad‐scale community system level change strategies; (2) health and social care system level change strategies; (3) lay community health outreach workers; and (4) group‐based health education and support for targeted risk groups led by trained peers or by health professionals Comparision: no intervention (48 studies) or alternative intervention (10 studies) | ||||

| ||||

| Outcomes | Impact | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE)* | Comments |

| Improvement in measures of health behavior at 24 to 48 months of follow‐up | Broad‐scale community system level change strategies lead to little or no difference in health behavior measures in large samples of community residents |

29,474 (7) | ⊝⊕⊝⊝ Very low certainty |

Studies targeted entire municipalities |

| Improvement in measures of health status at 24 to 60 months of follow‐up | Broad‐scale community system level change strategies lead to little or no difference in health status measures in large samples of community residents | 14,431 (7) | ⊝⊕⊝⊝ Very low certainty |

Studies targeted entire municipalities |

| ||||

| Improvement in measures of health behavior at 24 to 48 months of follow‐up | Broad health and social care system level strategies lead to small beneficial changes in measures of health behavior in large samples of community residents | 52,849 (4) | ⊝⊕⊝⊝ Very low certainty | Studies targeted entire municipalities |

| Improvement in measures of health status at 6 to 36 months of follow‐up | Broad health and social care system level strategies lead to small beneficial changes in measures of health status in large samples of community residents | 21,607 (3) | ⊝⊕⊕⊝ Low certainty |

Studies targeted entire municipalities |

| ||||

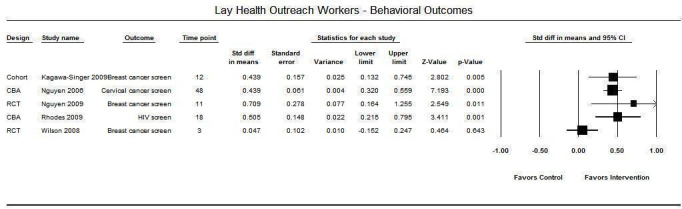

| Improvement in measures of health behavior at 3 to 48 months of follow‐up | Lay community health outreach worker interventions lead to beneficial changes in health behavior measures of moderate magnitude in fairly large samples of community residents |

4957 (5) | ⊝⊕⊝⊝ Very low certainty | |

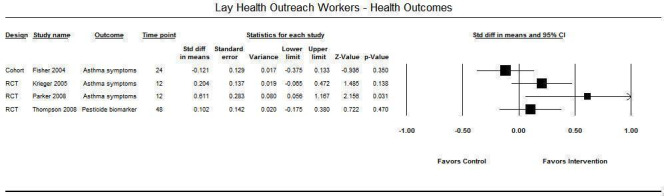

| Improvement in measures of health status at 12 to 48 months of follow‐up | Lay community health outreach worker interventions may lead to beneficial change in health status measures in fairly large samples of community residents; however, results were not consistent across studies | 1833 (4) | ⊝⊕⊕⊝ Low certainty | |

| ||||

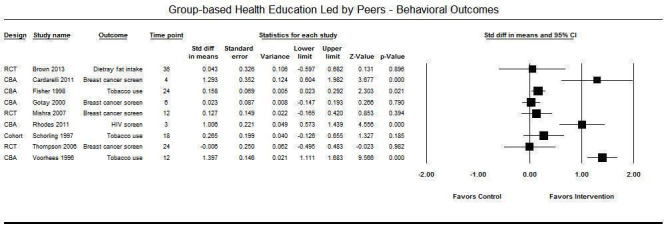

| Improvement in measures of health behavior at 4 to 36 months of follow‐up | Peer‐led health education and support to small groups yielded Inconsistent findings — either little or no effect or large effects — on health behavior measures in populations targeted for higher health risks |

4447 (9) | ⊝⊕⊝⊝ Low certainty | |

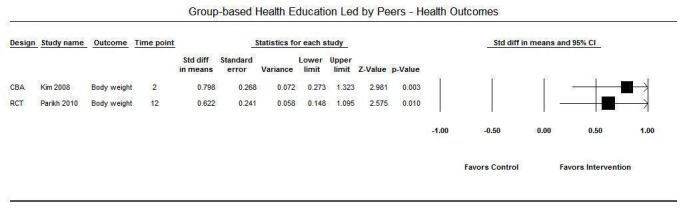

| Improvement in measures of health status at 2 to 12 months of follow‐up | Peer‐led health education and support for small groups may improve weight control outcomes | > 251 (2) | ⊝⊕⊕⊝ Low certainty | |

| ||||

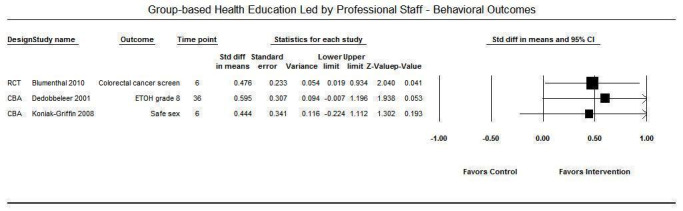

| Improvement in measures of health behavior at 6 to 36 months of follow‐up | Professionally led health education and support for small groups may lead to beneficial change in measures of health behavior in populations targeted for higher health risks | 1209 (3) | ⊝⊕⊝⊝ Very low certainty | |

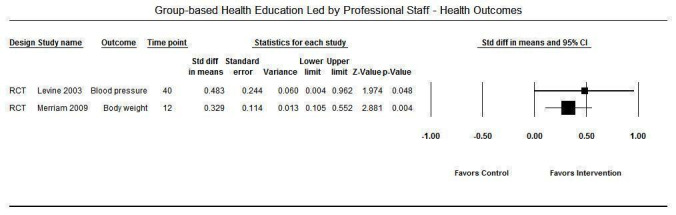

| Improvement in measures of health status at 12 to 40 months of follow‐up | Professionally led health education and support for small groups improve health status measures in populations targeted for higher health risks | 783 (2) | ⊝⊕⊕⊝ Low certainty | |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

* Characteristics of the evidence base (i.e. 67% non‐randomized studies, several of which evaluated outcomes in large population‐based samples) in this review resulted in an assessment of evidence as low to quite low in certainty. Although the aim of the table is to provide transparency to review users, this method of combining internal and external validity assessments may not yield reliable predictors of the impact of further research on our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Background

Description of the condition

Unfavorable racial and ethnic disparities in health status are pervasive and can be identified at all stages of the life cycle, from birth to old age (LaVeist 2005). Socioeconomic conditions — including poverty, inadequate educational opportunities, unemployment, limited access to basic services and goods such as nutritional foods, and poor quality health care — contribute to health disparities (Marmot 2006). Some groups in society are disproportionately exposed to adverse social conditions as a consequence of differing from the predominant population (e.g. in terms of ethnic background, language, culture, religion) and experience differential treatment and discrimination (Williams 2010). One approach to reducing health disparities has been to mobilize community representatives of target populations to work collaboratively with multi‐sector public and private organizations to identify common health issues, develop program or policy interventions, and attempt to bring about community‐level change that supports health‐promoting opportunities and behaviors (Bazzoli 2003; Liao 2011; Shortell 2002). This represents a departure from a service model that views community residents as simply recipients of services and instead engages them in mobilizing resources to reduce health disparities.

Description of the intervention

Increasingly, government and private funding initiatives are promoting coalitions, collaborations, and other interorganizational approaches to address complex community health issues. Community coalitions are one strategy in the wider range of community‐based co‐operative programs that involve community members in programs to improve population health (e.g. community‐based participatory research, lay community health workers, advisory boards that include community members). Specifically, community coalitions are conglomerates of citizen groups, public and private organizations, and professions (Dluhy 1990) that are characterized by representation from multiple community sectors in bottom‐up planning and decision making. They operate through partnerships and emphasize using local assets and resources to build community capacity. The focus of a community coalition may vary depending on the sectors of the community involved (e.g. education, public safety, public health). Characteristics of these partnerships and organizational structures affect how a coalition functions and how resources are exchanged (Mizrahi 2001). Factors such as clarity of mission, coalition leadership, established governance structures, training and technical support, processes of communication, and member satisfaction can advance or impede the likelihood that a coalition can mobilize resources and implement interventions (Kadushin 2005; Mitchell 2000; Roussos 2000; Zakocs 2006). The broad cross‐sector composition and the voluntary nature of community coalitions distinguish them from other public health models.

The theory and principles behind increasing control of local communities over their affairs and using multi‐agency partnerships to bring together the resources necessary to achieve common goals have antecedents in health promotion and disease prevention coalitions (Green 1990), as well as in community development models (Chavis 1992); moreover, they draw from several theories, including social ecology, social capital, and community empowerment, as well as organizational behavior theories such as network and open‐systems theories (Kreuter 2002; Stokols 1996; Wandersman 1996). This now widely used strategy is based on the premise that health is a product of complex interactions between the individual and the social environment and thus is amenable to influence by community‐based collaborative efforts (Anderson 2003; Stokols 1992). The coalition's choice of a health improvement issue and intervention strategy is based on the shared goals and resources of member stakeholders and funders. A broad range of topics is anticipated because of the sectors involved (e.g. transportation, housing), the community population targeted (e.g. youth, seniors, high‐risk individuals), and the conditions of interest (e.g. chronic disease, substance abuse, access to care).

To summarize, this multi‐sector coalition model is a social initiative that connects a community targeted for intervention with stakeholders who share a common interest in reducing health disparities by changing community‐level structures, processes, and policies to promote the health and well‐being of local residents.

How the intervention might work

Some key assumptions underlie community‐based health programs in general, and community coalition models in particular. The focus on community stems from the recognition that "humans live in, are shaped by, and in turn shape the environment in which they live" (Nilsen 2006). Both geographic location and networks of social relationships exert influence. The notion of community participation — another key aspect — places value on members' knowledge of "what matters." Intersectoral collaboration recognizes that many factors that impact health are outside of the health field. In addition, collaboration across sectors allows pooling of local community knowledge and resources with external partners' contributions of financial and technical support to achieve common goals. Finally, the aim of community‐based strategies is to control determinants of morbidity and mortality while lessening risk across the population. Thus community‐level, rather than individual‐level, outcomes are the goal. Furthermore, long‐term, multi‐faceted intervention strategies (behavioral and structural) are needed to achieve results (Nilsen 2006).

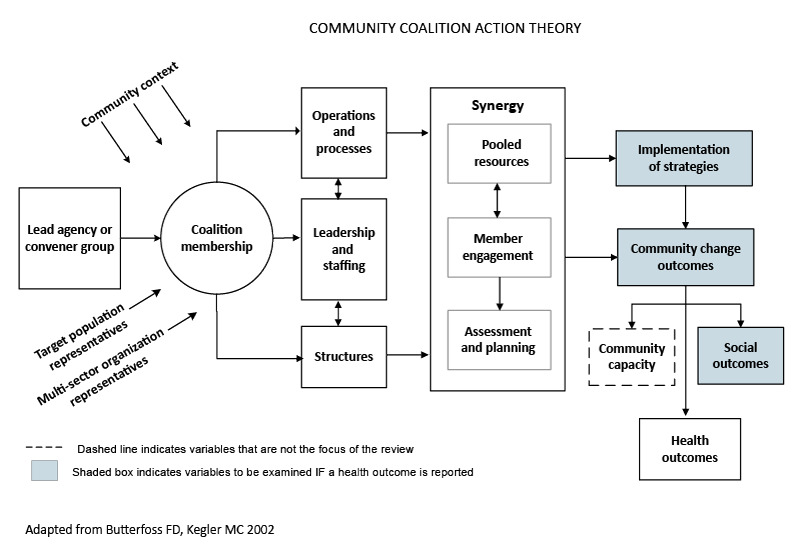

A community coalition provides a structured arrangement for collaboration by a broad constituency of participants who represent diverse interest groups, agencies, organizations, and institutions (Butterfoss 2002). Although some coalition members can be described as interested citizens or volunteers, many members represent organizations. The logic model provided in Figure 1 depicts the program theory underlying community coalitions that was used to guide this systematic review (Butterfoss 2002). Coalitions are formed when a lead agency or a convening group takes action on a community issue (e.g. youth drug and alcohol use); they may result from an opportunity (e.g. government funding for community‐based asthma prevention) or sometimes from a mandatory requirement by the funding source (e.g. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation funding for the Fighting Back Initiative). Governments and foundations see community coalitions as a means of reducing costs and duplication of effort through blending of resources and savings of prevention programs at the local level, where they are intended to have an impact. But as policymakers look increasingly to community coalitions as a solution to complex social and public health problems, community members must understand how these social initiatives function, and when and why they do or do not work as intended.

1.

Logic model.

Why it is important to do this review

The World Health Assembly has issued a resolution on reducing health inequities through action on social determinants of health (WHO 2009). This resolution requires continued research on interventions to reduce health disparities within sectors beyond health care. Furthermore, increased emphasis has been placed on applying participatory processes to reduce health disparities. Engaging communities and civil society more inclusively and transparently in policymaking processes through meaningful collaboration in governance was a key point at the 2011 World Conference on Social Determinants of Health (WHO 2011). Closing the gap in health disparities is not just a moral imperative — it is an economic one as well. Health inequities are costly in terms of wasted human potential, lost productivity, and expensive treatment for preventable conditions. A study commissioned by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies in the United States provides insight into the financial burden for society imposed by racial and ethnic health disparities (LaVeist 2009). Eliminating disparities would have reduced direct medical costs by USD 229.4 billion over the four‐year period from 2003 to 2006, and indirect costs of these inequities by USD 1.24 trillion.

What is lacking is a rigorous systematic review of the literature on the effectiveness of community coalition models in reducing racial and ethnic disparities in health and well‐being. Previous literature reviews have yielded equivocal findings regarding the success of community coalitions in addressing complex health problems (Berkowitz 2001; Kreuter 2000; Roussos 2000; Wagner 2000a; Zakocs 2006). A better understanding of the types of coalition structures and processes critical for effectiveness is needed, as this approach continues to be a popular public health strategy. Information is also needed on the benefits and costs and potential adverse effects that result when community coalitions are used as a bridge between networks of service providers and community residents, especially vulnerable target populations. Systematic examination is needed of coalition organizational structures and processes likely to explain effectiveness, as well as of community contextual factors that might hinder or help the coalition accomplish its goals. Examining the types of community issues targeted, the implementation strategies employed, and the resources required can inform decision making about the use of community coalition models.

Objectives

To assess effects of community coalition‐driven interventions in improving health status or reducing health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included cluster‐randomized controlled trials, randomized controlled trials, quasi‐experimental designs (e.g. propensity score matching, regression discontinuity designs), controlled before‐after studies, interrupted time series studies (with at least three data points before and three after the intervention), and prospective controlled cohort studies.

When review authors noted that studies referred to a process evaluation or another methodologic detail that is published elsewhere in a separate paper, we obtained these additional papers and considered them as part of the included studies.

Types of participants

Community‐level coalitions are the focus of this review; we did not include state‐wide or national coalitions, which differ in purpose and stakeholder characteristics. Communities are aggregates of people who form a loosely cohesive association within a residential space or district; they represent a subpopulation of a larger unit such as a city, or they can be indigenous and ethnic groups that may not reside in immediate residential proximity but possess a common community identity. We have examined minority racial and ethnic communities, including indigenous people, who participate in community coalitions, and for whom coalitions are targeting health promotion programs and policies.

We have included only studies of community coalitions with at least one racial or ethnic minority group representing the target population, and at least two community public or private organizations.

Types of interventions

Interventions include locally recruited coalitions in racial and ethnic minority communities in partnership with social and health service agencies, schools, businesses, etc., whose role is to leverage community resources and implement community‐based programs and policies that promote health or prevent health disparities. Interventions may involve strategies that target neighborhood social conditions influencing health outcomes (e.g. access to healthy food, safe neighborhood environments) or community risk behaviors (e.g. smoking). We have included comparisons with communities that do not employ a community coalition model to promote health, as well as comparisons with communities that do not provide an intervention or use other strategies.

Types of outcome measures

We have included studies that report a health outcome and describe other determinants of health such as changes in neighborhood conditions (e.g. level of violence) or policies (e.g. access to services) implemented to promote community health improvement.

Primary outcomes

Major outcomes of interest are direct measures of health status and lifestyle factors when evidence indicates that these have an effect on those direct measures. Studies are included when data on mortality (e.g. all‐cause death within period of study, probability of survival) and morbidity (e.g. quality of life measures, incidence rates, measures of symptoms and functionality) and health behavior change measures show that interventions directly affected levels of health risk or health protection (e.g. measures of physical activity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, dietary change). Of particular interest are measures of change in health disparities among predominant populations and ethnic and racial minority populations.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes that are recorded include changes in neighborhood conditions or policies introduced to promote community health improvement (e.g. a policy establishing a farmers' market to provide access to fresh produce, a school policy opening sports fields for local resident use during non‐school periods).

We have used qualitative data and process evaluations embedded in the included studies to capture information on community context and coalition structures and mechanisms.

We have used cost data embedded in the studies to assess cost and resource use.

We have captured adverse outcomes reported qualitatively or quantitatively at community, organizational, and individual levels.

Search methods for identification of studies

We developed search strategies in conjunction with the Cochrane Public Health Group Study Search Co‐ordinator that include terms used to identify appropriate global evaluation studies, for which definitions and designations may differ. We chose the literature search period start date of 1990 because a marked rise in local community coalitions for health promotion and disease prevention began in the early 1990s (Butterfoss 2007). Furthermore, during that period, "multi‐sector" coalition models (vs a single grass‐roots advocacy group) became the predominant strategy for private foundations and government organizations that saw pooling of resources and mobilizing of talents across diverse groups as inherent to a broad‐based, social‐ecologic approach to community change (Butterfoss 2007).

Electronic searches

We provided a summary of search strategies in Appendix 1.

Health

MEDLINE, January 1990 through March 31, 2014.

EMBASE, January 1990 through March 31, 2014.

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), January 1990 through March 31, 2014.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), January 1990 through March 31, 2014.

PsycINFO, January 1990 through March 31, 2014.

Social science

Social Science Citation Index, January 1990 through March 31, 2014.

Grey literature

Dissertation Abstracts, January 1990 through March 31, 2014.

System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (SIGLE), January 1990 through September 30, 2013 (we were unable to access the database for the March 2014 update).

Developing countries

Global Health Library, January 1990 through March 31, 2014.

Searching other resources

We screened reference lists of all included studies and review articles for relevant titles.

We handsearched the following four journals for the period 2000 to January 2012: Health Promotion International, Health Promotion Practice, Health Education Research, Preventive Medicine.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

A research librarian (SS) conducted electronic searches of the bibliographic databases. Review authors (LA and KA) removed duplicate studies across databases and undertook initial screening of titles and abstracts to remove those clearly outside the scope of the review. We retrieved in full text papers potentially meeting inclusion criteria based on content of titles and abstracts and linked multiple publications and reports on the same study. Two independent review authors (of LA, KA, CS, and JB) screened all full‐text papers to determine eligibility for inclusion and consulted a third review author when consensus was needed to resolve disagreements. We recorded reasons for study exclusion and translated for screening purposes articles published in languages other than English. We used Reference Manager bibliographic software to manage citation records.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data from all studies that met inclusion criteria. Two review authors (of LA, KA, CS, LK, and JB) extracted study characteristics of eligible papers, details of the community coalition, details of the interventions, and outcomes data and resolved disagreements through discussion.

Review authors (LA, KA, and CS) pilot‐tested a Community Coalitions Data Extraction Form. We used this extraction form (prepared in Excel format) to collect information on citation tracking and classification, community coalition characteristics, setting and context, intervention characteristics and strategies, target population sociodemographic characteristics, outcome ascertainment characteristics, analytic methods, and results. We examined patterns within coalition structures and processes, intervention strategies, and types of outcomes for aggregation of similar groups for synthesis and interpretation. We used the program logic model presented in Figure 1 to facilitate categorization of studies.

We entered data into Review Manager for storage and analysis (RevMan 2011). When health outcomes were reported, we also collected information on changes in neighborhood structures and policies that occurred to promote change in those health outcomes. When studies reported more than one end point per outcome, we recorded all for synthesis at a similar follow‐up period across similar studies. When studies reported multiple measures of the same or similar outcomes, we recorded these.

We included qualitative data and process evaluations embedded in the primary study or related reports to capture information on community context and coalition recruitment and structures, and on decision‐making mechanisms. We collected information on country and regional influences when reported, so we could consider location when interpreting study findings. We coded data on costs and use of resources. We captured adverse outcomes reported qualitatively or quantitatively. We contacted authors of primary studies when information was missing or clarification was needed.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (LA, KA) assessed studies meeting inclusion criteria for risk of bias and resolved disagreements through discussion. We used the Cochrane Collaboration "Risk of bias" tool (Cochrane 2008) for randomized controlled trials, and the Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC 2015) "Risk of bias" tool for controlled before‐after studies and for interrupted time series studies. For randomized controlled trials, controlled before‐after studies, and prospectively controlled cohort studies, we critically assessed potential for bias for random sequence generation, allocation concealment, comparability of outcome measurements at baseline, comparability of other characteristics at baseline, completeness of outcome data, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, protection against contamination, and selective reporting. For interrupted time series, we performed assessments for independence of interventions from other changes, point of analysis at point of intervention, intervention effects on data collection, blinding of outcome assessment, completeness of outcome data, and selective reporting. In each area, we appraised risk of bias as “high,” “low,” or “unclear.” We summarized risk of bias for each study and considered this information when interpreting review conclusions.

Measures of treatment effect

We used Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis 2.2 (CMA) software to calculate standardized effect sizes for health outcomes because it allowed greater flexibility in deriving and displaying forest plots; this was useful given that we do not present formal meta‐analyses of pooled effects. We reported outcomes both as differences and as ratios. We calculated a standardized mean difference effect size using CMA when outcomes were reported with sufficient data to compute the statistic. When outcome data were dichotomous (i.e. odds ratios), we transfomed them into standardized mean differences in CMA according to the method proposed by Hasselblad 1995.

Unit of analysis issues

In cluster‐randomized studies, we examined whether level of randomization was taken into account if individual participant data were analyzed, and adjusted accordingly. When cross‐over designs were used, we gathered data from the first treatment period. When multiple treatment groups were compared with a single control, we selected the most relevant treatment condition if the other groups were not applicable to the review question. When repeated measurements occurred, we used only one measurement in a single analysis.

Dealing with missing data

When important data were missing from the published report such as analytic methods used, baseline measurements, accounting for missing participants, or statistics such as variance measures, we attempted to contact the study authors via email. When we were unable to obtain missing data, we indicated this in the narrative description of that study. We considered the quantity of missing data in the overall review and discussed the potential impact on our findings and conclusions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We did not conduct meta‐analysis to pool effects across all studies because studies included in the systematic review were variable with respect to types of participants, types of interventions, and types of outcomes. We used a random‐effects model to compute standardized mean difference effect size as the common statistic for comparison purposes. Moderate to substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 50%) in results precluded pooling of effects across studies.

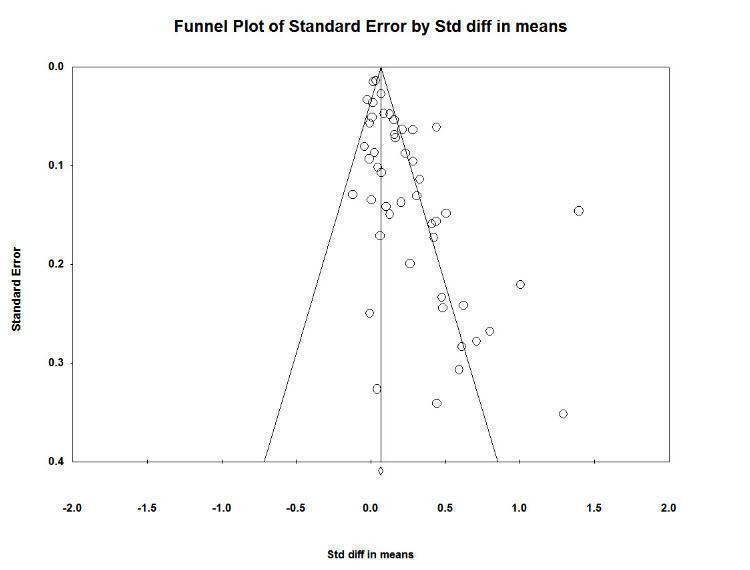

Assessment of reporting biases

We used a funnel plot to investigate the impact of publication bias.

Data synthesis

We observed heterogeneity within the collection of studies on community coalitions with respect to the population targeted, the intervention strategy employed, and the health outcome targeted. We grouped studies with respect to study methods, interventions, and outcomes. When data derived from similar methods reported on similar outcomes following similar interventions, we originally planned to pool effect sizes using CMA software. However, statistical synthesis of data was not appropriate, and we synthesized study information narratively.

Differences in interventions and outcomes across the body of community coalition studies precluded preparation of a summary of results of the data synthesis using a GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach, as suggested in Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Data were insufficient to allow subgroup analyses to examine the influence of (1) study design, (2) targeted health condition, (3) single‐setting and single‐level versus multi‐setting and multi‐level intervention strategies, (4) coalition organizational structure, and (5) community socioeconomic contextual factors, as was originally planned.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not perform sensitivity analyses comparing the results of two or more meta‐analyses calculated using different assumptions of acceptable study quality, as marked heterogeneity prohibited pooling of outcomes.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

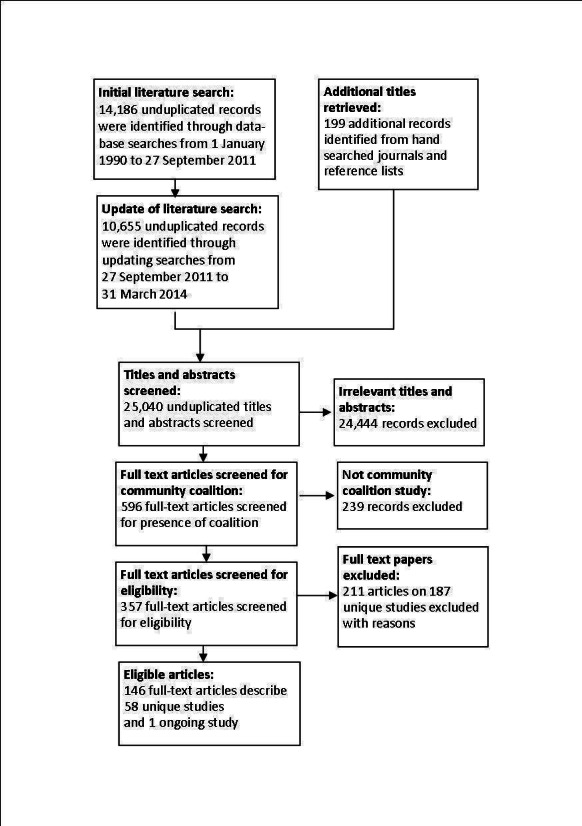

Although our review had strict inclusion criteria regarding the definition of a local community coalition, with racial and ethnic minority community members represented as one of the collaborating partners, our searches cast a wide net on the range of interventions that might be expected to reduce health disparities. Literature searches identified 14,186 unique records for the period January 1, 1990, to September 27, 2011, and search updates of the same databases yielded an additional 10,655 unique records for the period September 27, 2011, to March 31, 2014. Handsearched journals and reference lists yielded 199 additional records, for a total of 25,040 unduplicated titles and abstracts for screening. Figure 2 provides the flow diagram for the literature searches. After screening titles and abstracts for clearly irrelevant records, we excluded 24,444 studies. We screened the remaining 596 articles to determine if a community coalition was present; we found that 239 were not community coalition studies and excluded them. Of 357 articles that reported on a community coalition intervention study, we identified 146 articles representing 58 unique community coalition‐driven interventions. These studies described coalitions consisting of racial and ethnic minority community organizations and community members for whom the intervention was intended, and at least two community public or private organizations, which were comparative in evaluation design (i.e. randomized or quasi‐randomized controlled trials, controlled before‐after studies, or an interrupted times series). We identified one ongoing study at the protocol stage. We excluded 187 studies because they used study designs that were not eligible (e.g. case study, single group before‐after), and 36 because no racial or ethnic minority population was represented by a community coalition.

2.

Literature flow diagram.

Included studies

The 58 studies included in the review differed in characteristics of coalitions formed and characteristics of interventions implemented (i.e. population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes), and in several other factors. This section describes these differences. Detailed information on each study is presented in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Characteristics of study methods

Thirty‐one studies used a controlled before‐after evaluation design (see cite sheet). Nineteen studies reported that they used a randomized design; of these, 11 were randomized controlled trials and eight used a cluster‐randomized design. Of the remaining studies, seven were controlled prospective cohort trials and one used a time series design. We assessed outcomes of the 58 studies by reviewing responses to questionnaires, surveys, and records for 133,852 individuals.

Publication dates for the primary studies spanned a 20‐year period from 1994 to 2014. More studies were published in the latter decade, with 41 published between 2004 and 2013, compared with 16 published between 1994 and 2003. One study was published in 2014, but the search period ended March 31, 2014.

The country of origin in 52 studies was the United States. Two studies were conducted in Australia (Kelaher 2009; Kelaher 2010), two in Canada (Dedobbeleer 2001; Paradis 2005), two in England (Melhuish 2010; Stafford 2008), and two in the Netherlands (Abbema 2004; Kloek 2006).

Characteristics of participants

Studies included in this review targeted a wide array of racial and ethnic minorities. Thirty studies included individuals who were African American, or individuals of African or Afro‐Caribbean descent (Blumenthal 2010; Brownson 1996; Brownson 2004; Burhansstipanov 2010; Cardarelli 2011; Cheadle 2001; Darrow 2011; Davidson 1994; Fisher 1998; Fisher 2004; Fuller 2007; Holder 2000; Kim 2008; Kronish 2014; Kruger 2007; Larson 2009; Levine 2003; Liao 2010b; Paine‐Andrews 1999; Parikh 2010; Parker 2008; Plescia 2008; Rothman 1999; Schorling 1997; Spencer 2011; Treno 2007; Voorhees 1996; Wagner 2000a; Wells 2013; Wilson 2008). Eighteen studies included Latino and/or Latina individuals (Burhansstipanov 2010; Darrow 2011; Davidson 1994; Holder 2000; Koniak‐Griffin 2008; Kronish 2014; Liao 2010b; Merriam 2009; Paine‐Andrews 1999; Parikh 2010; Parker 2008; Rhodes 2009; Rhodes 2011; Spencer 2011; Thompson 2006; Thompson 2008; Treno 2007; Wells 2013). Nine studies targeted individuals who were Asian or Pacific Islanders, including Hawaiian (Gotay 2000) and Hmong (Kagawa‐Singer 2009), and communities with large populations of Asian Americans (Liao 2010a; Liao 2010b), Vietnamese or Chinese‐Vietnamese (McPhee 2003; Nguyen 2006; Nguyen 2009), Samoans (Mishra 2007), and Koreans (Moskowitz 2007). Six studies targeted Native Americans or indigenous populations (Brown 2013; Burhansstipanov 2010; Kelaher 2009; Liao 2010b; Paradis 2005; Wagner 2000b). A single study included individuals of Middle Eastern descent among participants from other racial and ethnic minorities (Dedobbeleer 2001).

Residents of geographic areas defined as socioeconomically disadvantaged or ethnically diverse were the target of 10 studies (Abbema 2004; Clark 2013; Kelaher 2009; Kelaher 2010; Kloek 2006; Krieger 2000; Krieger 2005; Melhuish 2010; Saxe 2006; Stafford 2008). A single study (Thompson 2008) targeted migrant workers at risk of agricultural pesticide exposure.

In terms of age, most studies targeted adults (Blumenthal 2010; Brownson 1996; Brownson 2004; Burhansstipanov 2010; Cardarelli 2011; Darrow 2011; Fisher 1998; Gotay 2000; Holder 2000; Kagawa‐Singer 2009; Kelaher 2010; Kim 2008; Kloek 2006; Larson 2009; Levine 2003; Liao 2010a; Liao 2010b; McPhee 2003; Merriam 2009; Mishra 2007; Moskowitz 2007; Nguyen 2006; Nguyen 2009; Parikh 2010; Plescia 2008; Rhodes 2009; Rhodes 2011; Saxe 2006; Schorling 1997; Spencer 2011; Thompson 2006; Thompson 2008; Voorhees 1996; Wagner 2000a; Wilson 2008), six studies targeted adolescents (Brown 2013; Cheadle 2001; Dedobbeleer 2001; Koniak‐Griffin 2008; Paine‐Andrews 1999; Wagner 2000b), five studies targeted young children (Fisher 2004; Melhuish 2010; Paradis 2005; Rothman 1999; Thompson 2008), four studies included children and adolescent youth (Clark 2013; Davidson 1994; Krieger 2005; Parker 2008), and two studies targeted infants (Kelaher 2009; Kruger 2007). One study (Krieger 2000) targeted senior citizens, and three studies targeted the general public (Abbema 2004; Treno 2007; Wells 2013).

Nine studies targeted women (Burhansstipanov 2010; Cardarelli 2011; Gotay 2000; Kagawa‐Singer 2009; Mishra 2007; Moskowitz 2007; Nguyen 2006; Nguyen 2009; Wilson 2008). All but one study targeting women focused on screening and prevention of breast and/or cervical cancer. Koniak‐Griffin 2008 focused on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention for adolescent Latina mothers and their male partners. Two studies targeted males (Rhodes 2009; Rhodes 2011).

Nine studies included individuals according to their medical history or health risk, including children and youth with asthma (Clark 2013), minority populations with high HIV incidence (Darrow 2011), youth with asthma (Fisher 2004; Krieger 2005; Parker 2008), intravenous drug users (Fuller 2007), stroke survivors (Kronish 2014), clinic patients with hypertension (Levine 2003), and adults with pre‐diabetes (Parikh 2010).

Most studies targeted individuals in urban settings (Abbema 2004; Blumenthal 2010; Burhansstipanov 2010; Cardarelli 2011; Cheadle 2001; Clark 2013; Darrow 2011; Fisher 1998; Fisher 2004; Fuller 2007; Gotay 2000; Kagawa‐Singer 2009; Kelaher 2009; Kelaher 2010; Kloek 2006; Koniak‐Griffin 2008; Krieger 2000; Krieger 2005; Kronish 2014; Kruger 2007; Levine 2003; Liao 2010a; Liao 2010b; Merriam 2009; Mishra 2007; Moskowitz 2007; Plescia 2008; Rothman 1999; Saxe 2006; Spencer 2011; Stafford 2008; Treno 2007; Voorhees 1996; Wagner 2000a; Wells 2013; Wilson 2008). Eight studies included individuals in rural settings (Brown 2013; Brownson 1996; Brownson 2004; Kim 2008; Paradis 2005; Schorling 1997; Thompson 2006; Wagner 2000b). Participants in one study were suburban (Holder 2000) and participants in six studies were from mixed urban/suburban/rural settings (Kelaher 2009; Melhuish 2010; Paine‐Andrews 1999; Rhodes 2009; Rhodes 2011; Thompson 2008).

Characteristics of coalitions

This review includes studies of community coalitions with at least one racial or ethnic minority group representing the target population, and at least two community public or private organizations. On the basis of study author description, community coalitions were coded as one of three types: “grass roots” partnerships of predominantly community‐based organizations; academic institution partnerships with communities; or public health agency partnerships with predominantly public agencies.

Academic/community partnership was the most prevalent coalition typology and was reported in 34 studies (Blumenthal 2010; Brown 2013; Brownson 2004; Cardarelli 2011; Cheadle 2001; Clark 2013; Darrow 2011; Fisher 1998; Fisher 2004; Fuller 2007; Gotay 2000; Holder 2000; Kagawa‐Singer 2009; Kim 2008; Koniak‐Griffin 2008; Krieger 2000; Krieger 2005; Kronish 2014; Levine 2003; Merriam 2009; Mishra 2007; Moskowitz 2007; Nguyen 2006; Nguyen 2009; Parikh 2010; Parker 2008; Rothman 1999; Schorling 1997; Spencer 2011; Thompson 2008; Voorhees 1996; Wagner 2000a; Wells 2013; Wilson 2008).

Fifteen studies reported a coalition based on a partnership of public health agencies predominantly with other public agencies (Abbema 2004; Brownson 1996; Kelaher 2009; Kelaher 2010; Kloek 2006; Kruger 2007; Larson 2009; Liao 2010a; Liao 2010b; Melhuish 2010, Paradis 2005, Plescia 2008, Rhodes 2009, Rhodes 2011Wagner 2000b).

Nine studies reported a coalition based on partnership of primarily community‐based agencies (Burhansstipanov 2010; Davidson 1994; Dedobbeleer 2001; McPhee 2003; Paine‐Andrews 1999; Saxe 2006; Stafford 2008; Thompson 2006; Treno 2007).

In addition to coalition typology, and on the basis of relevant research literature, authors of this systematic review identified variables of coalition structure and process deemed salient to an understanding of the effectiveness of community coalition‐based interventions. These variables included coalition convenor, type of leadership, number of organizational groups involved, governance structure, staffing, mission statement, by‐laws, goals and objectives, funding, meeting frequency, duration of coalition, and whether or not training for coalition members, a needs assessment process, and/or work groups/subcommittees were included. In addition, review authors coded for problems noted (i.e. problems with funding, leadership, member engagement, conflict resolution, or communication) and for other problems that may impede coalition functioning. With few exceptions, included studies reported these variables in insufficient detail, if at all. A minority of studies reported in very general terms on leadership and staffing, and noted whether needs assessment was conducted. Discussion of coalition member engagement was rarely addressed and usually was limited to reports of training of peer leaders or navigators.

Congruent with the predominant academic partnership coalition typology reported, the lead sector was reported as a university in 18 studies (Brownson 2004; Cardarelli 2011; Cheadle 2001; Darrow 2011; Kim 2008; Koniak‐Griffin 2008; Kronish 2014; Levine 2003; Mishra 2007; Nguyen 2009; Parker 2008; Rhodes 2011; Rothman 1999; Schorling 1997; Thompson 2008; Treno 2007; Voorhees 1996; Wagner 2000a).

A health agency or healthcare provider was the lead sector in 13 studies (Abbema 2004; Brown 2013; Brownson 1996; Gotay 2000; Kloek 2006; Krieger 2000; Krieger 2005; Kruger 2007; Larson 2009; Merriam 2009; Moskowitz 2007; Plescia 2008; Wagner 2000b), and a not‐for‐profit community‐based organization in seven studies (Burhansstipanov 2010; Dedobbeleer 2001; Fisher 1998; Fisher 2004; McPhee 2003; Rhodes 2009; Wells 2013). Community members were identified as the lead sector in two studies (Blumenthal 2010; Thompson 2006), and government human service or social welfare agencies in two studies (Kelaher 2009; Kelaher 2010). Ten studies did not report a lead sector.

The most common type of coalition leadership, reported in 13 studies, was core group/shared leadership (Abbema 2004; Brown 2013; Burhansstipanov 2010; Fisher 1998; Fisher 2004; Krieger 2000; Krieger 2005; Kronish 2014; Nguyen 2006; Nguyen 2009; Paradis 2005; Thompson 2006; Wells 2013). Another 12 studies reported steering committee leadership (Blumenthal 2010; Cardarelli 2011; Cheadle 2001; Dedobbeleer 2001; Gotay 2000; Kelaher 2010; Kim 2008; Larson 2009; Levine 2003; Parker 2008; Treno 2007; Voorhees 1996). Three studies reported leadership by a single person co‐ordinator (Brownson 1996; Darrow 2011; Schorling 1997), and two studies reported leadership by a principal investigator (Brownson 2004; Merriam 2009).

Twenty‐six studies reported a coalition needs assessment process (Abbema 2004; Brownson 1996; Burhansstipanov 2010; Cardarelli 2011; Clark 2013; Darrow 2011; Fuller 2007; Gotay 2000; Kagawa‐Singer 2009; Kelaher 2010; Kim 2008; Kloek 2006; Larson 2009; Levine 2003; Merriam 2009; Moskowitz 2007; Nguyen 2006; Nguyen 2009; Parikh 2010; Parker 2008; Rhodes 2009; Saxe 2006; Schorling 1997; Spencer 2011; Thompson 2006; Voorhees 1996).

Twenty‐seven studies reported use of coalition work groups or subcommittees (Abbema 2004; Brownson 1996; Dedobbeleer 2001; Fisher 1998; Fisher 2004; Fuller 2007; Gotay 2000; Kelaher 2009; Kelaher 2010; Kloek 2006; Krieger 2000; Krieger 2005; Kruger 2007; Larson 2009; Levine 2003; McPhee 2003; Merriam 2009; Nguyen 2006; Nguyen 2009; Parikh 2010; Parker 2008; Rhodes 2009; Treno 2007; Voorhees 1996; Wagner 2000a; Wagner 2000b; Wells 2013).

Thirteen studies reported that training of some kind was provided to coalition members (Brown 2013; Cardarelli 2011; Dedobbeleer 2001; Fisher 2004; Gotay 2000; Holder 2000; Kronish 2014; McPhee 2003; Moskowitz 2007; Plescia 2008; Schorling 1997; Thompson 2006; Voorhees 1996).

The role of theory

Understanding or explaining why or how a coalition‐driven approach may be effective requires explicit consideration of theory and, more important, exploration of conceptual and operational links between the constructs of collaborative community coalition theory and social behavior theory. Missing from the studies included in this review is an explicit theoretical rationale for applying a coalition approach to promoting health in racial and ethnic minorities.

As suggested by the logic model on which this review is based, the theory implied by a community coalition approach to health promotion in disenfranchised or marginalized populations is social‐ecologic theory, which links the social environment to health. Nine studies in this review identified a social‐ecologic theory as the rationale for their intervention approach (Abbema 2004; Blumenthal 2010; Brownson 2004; Larson 2009; Liao 2010a; Liao 2010b; Plescia 2008; Rhodes 2009; Rhodes 2011).

Fifteen studies identified community empowerment, community organization, or community‐sensitive research as their theoretical rationale (Brownson 1996; Burhansstipanov 2010; Cheadle 2001; Kelaher 2010; Kim 2008; Kloek 2006; Mishra 2007; Parker 2008; Rhodes 2009; Rhodes 2011; Schorling 1997; Spencer 2011; Stafford 2008; Thompson 2006; Wells 2013). Eleven studies reported social cognitive theory, or social learning theory, as their rationale (Blumenthal 2010; Brownson 1996; Burhansstipanov 2010; Kagawa‐Singer 2009; Krieger 2000; Krieger 2005; Merriam 2009; Paine‐Andrews 1999; Paradis 2005; Parker 2008; Wilson 2008). Although the latter two theories incorporate social support and imply access to community networks, they do not address other health determinants of the social environment that may be influenced by interagency collaboration.

Nine studies indicated a theory of individual behavior change as their rationale, such as Health Belief (Krieger 2000; Mishra 2007), Stage Theory (Brownson 1996; Kloek 2006; Schorling 1997), Precede‐Proceed (Levine 2003; Moskowitz 2007; Paradis 2005), and Self Efficacy (Parikh 2010). Other theories identified by single studies included Appreciative Inquiry (Kronish 2014), Innovation‐Diffusion (Paine‐Andrews 1999), Gender and Power (Koniak‐Griffin 2008), and Wounded Spirit Healing (Koniak‐Griffin 2008).

Twenty studies, including three of the nine REACH (Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health) studies (Kruger 2007; Nguyen 2006; Nguyen 2009), did not report an underlying theory. The REACH initiative implies a social‐ecologic approach, and four REACH studies identified this as their theoretical rationale (Larson 2009; Liao 2010a; Liao 2010b; Plescia 2008).

Characteristics of interventions

Review authors identified four core community engagement interventions utilized by the coalitions. These interventions represent a diverse set of community programs designed to improve health among racial and ethnic minority populations. Establishment of the coalition was a core component of each intervention, as it established the structure for engaging stakeholders and minority communities in collaborative decision making. Only one study (Wells 2013) explicitly tested the hypothesis that a coalition‐driven intervention provided added value, in terms of improved health status, compared with the same intervention delivered without the coalition model. The remaining studies evaluated a change in health behavior or health status resulting from the intervention strategy.

The 58 included studies evaluated behavioral change (n = 33) or health status change (n = 25) resulting from the intervention strategy. Forty‐eight studies compared the intervention group versus a control group that received no intervention or usual care. Ten studies compared the intervention group with a control group that received an alternative intervention (Blumenthal 2010; Brown 2013; Cardarelli 2011; Koniak‐Griffin 2008; Krieger 2005; Nguyen 2009; Rhodes 2011; Schorling 1997; Voorhees 1996; Wells 2013).

Thirty‐three studies measured change in health behavior as the primary outcome resulting from an intervention. Among these, 11 studies focused on cancer screening behaviors (Blumenthal 2010; Burhansstipanov 2010; Cardarelli 2011; Gotay 2000; Kagawa‐Singer 2009; Mishra 2007; Moskowitz 2007; Nguyen 2006; Nguyen 2009; Thompson 2006; Wilson 2008); eight studies evaluated changes in diet, physical activity, and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes (Brown 2013; Brownson 1996; Brownson 2004; Kloek 2006; Larson 2009; Liao 2010b; Plescia 2008; Wagner 2000a); seven examined alcohol, drug, or tobacco use (Dedobbeleer 2001; Fisher 1998; Liao 2010a; Saxe 2006; Schorling 1997; Voorhees 1996; Wagner 2000b); four studies examined human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) risk behaviors (Fuller 2007; Koniak‐Griffin 2008; Rhodes 2009; Rhodes 2011); two evaluated changes in immunization uptake among seniors (Krieger 2000) and children (McPhee 2003); and one study reported on changes in breastfeeding behavior (Kelaher 2009).

Twenty‐five studies measured a change in health status. Four reported changes in asthma symptoms in children (Clark 2013; Fisher 2004; Krieger 2005; Parker 2008); eight reported changes in cardiovascular disease and diabetes risk factors including body weight (Kim 2008; Melhuish 2010; Paradis 2005; Parikh 2010), blood pressure (Kronish 2014; Levine 2003), and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) (Merriam 2009; Spencer 2011); four reported changes in the quality of neighborhood/community life (Abbema 2004; Cheadle 2001; Kelaher 2010; Stafford 2008); and three reported on injuries (Davidson 1994; Holder 2000; Treno 2007). The following were reported in single studies: depression (Wells 2013), HIV incidence (Darrow 2011), infant mortality rates (Kruger 2007), teen pregnancy rates (Paine‐Andrews 1999), blood lead levels in children (Rothman 1999), and exposure to pesticides (Thompson 2008).

Only a few studies reported secondary outcomes that measured changes in the social‐ecologic domain. Abbema 2004 reported changes in perceived neighborhood safety, Cheadle 2001 measured levels of community mobilization, Gotay 2000 reported changes in social support related to cancer screening norms and behavior, and Stafford 2008 reported changes in level of satisfaction with local neighborhood living conditions. One study (Nguyen 2006) reported a policy change — re‐establishment of a state cancer screening program — as an outcome of the intervention. Most studies that sought to improve the sociocultural environment used behavioral and health status measures to evaluate program impact.

Adverse outcomes resulting from coalition‐driven interventions were not reported. Some problems (e.g. power imbalance between coalition members, unequal access to information, absence of sustainable funding) were noted anecdotally in a few studies (see discussion in "Potential Harms" section).

Four core intervention strategies were selected by the coalitions: (1) broad‐scale community system‐level change (Abbema 2004; Brownson 1996; Brownson 2004; Davidson 1994; Holder 2000; Kelaher 2010; Kloek 2006; Kruger 2007; Larson 2009; Paine‐Andrews 1999; Paradis 2005; Plescia 2008; Stafford 2008; Treno 2007; Wagner 2000a; Wagner 2000b); (2) broad‐scale health or social care system‐level change (Clark 2013; Fuller 2007; Kelaher 2009; McPhee 2003; Melhuish 2010; Saxe 2006; Wells 2013); (3) lay community health outreach workers (Burhansstipanov 2010; Cheadle 2001; Fisher 1998; Fisher 2004; Kagawa‐Singer 2009; Krieger 2005; Moskowitz 2007; Nguyen 2006; Nguyen 2009; Parker 2008; Rhodes 2009; Spencer 2011; Wilson 2008); and (4) group‐based health education and support for targeted groups led by trained peers (Brown 2013; Cardarelli 2011; Gotay 2000; Kim 2008; Kronish 2014; Mishra 2007; Parikh 2010; Rhodes 2011; Schorling 1997; Thompson 2006; Thompson 2008; Voorhees 1996) or by health professionals (Blumenthal 2010; Dedobbeleer 2001; Koniak‐Griffin 2008; Levine 2003; Merriam 2009; Rothman 1999). Mass media was the core strategy in one intervention (Darrow 2011), and a patient reminder system in another (Krieger 2000). We were unable to categorize the core intervention strategy for two studies (Liao 2010a; Liao 2010b) that summarized outcomes from multiple REACH programs (Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health), as each site used distinct coalition‐driven intervention approaches.

Broad‐scale community system‐level change strategies

Studies using broad‐scale community system‐level change strategies aimed to change sociocultural (e.g. public norms, regulatory processes and policies) and physical environments (e.g. housing, green spaces, neighborhood safety) to create supportive community environments for healthy choices and improved quality of life. Broad‐scale and comprehensive community initiatives typically required a longer duration than more specific programmatic efforts. In addition, it was difficult to define all of the components a priori as these programs evolved over time, and system leverage points were identified and acted on at multiple levels in the complex community system. It is not surprising that only one cluster‐randomized study was identified (Wagner 2000a), which targeted 80,953 urban Latino residents over a five‐year period to improve dietary intake for chronic disease prevention. Program components included improving grocery store options and providing community health screenings, nutrition classes, and school‐based nutrition education.

The remaining 15 studies that used broad‐scale community system‐level approaches included 11 controlled before‐after designs (Abbema 2004; Brownson 1996; Brownson 2004; Kelaher 2010; Kloek 2006; Kruger 2007; Larson 2009; Paine‐Andrews 1999; Paradis 2005; Plescia 2008), three interrupted time series (Davidson 1994; Holder 2000; Treno 2007), and one controlled prospective cohort study (Stafford 2008). Four of these consisted of multi‐component and multi‐level efforts to improve diet and physical activity among adults (Brownson 1996; Brownson 2004; Kloek 2006) and children (Paradis 2005); four studies aimed to improve resources for healthy behavior (e.g. places for recreation) and quality of community life (e.g. satisfaction with neighborhood) in socioeconomically deprived areas (Abbema 2004; Kelaher 2009; Plescia 2008; Stafford 2008); three aimed to reduce alcohol and drug risk behaviors among adults by raising awareness, altering beverage service practices in taverns, and altering law enforcement policies and practices (Holder 2000; Treno 2007), and, among Native American youth, through school‐based education, peer counseling, community education, and improved law enforcement (Wagner 2000b). The average duration of the 15 quasi‐experimental studies was 50 months.

Broad‐scale health or social care system‐level change strategies

Studies using broad‐scale health or social care system‐level strategies targeted the co‐ordinated behavior of multiple staff within a health or social care system; changed policies, procedures, and technologies to improve quality of care; and increased organizational and delivery system capacity and infrastructure to improve health outcomes among the populations served. Investigators applied complex interventions that altered the standard operating procedures of interrelated agencies in the system and changed practice protocols. We identified one cluster‐randomized controlled trial (Wells 2013) that implemented depression care quality improvement in a network of mental health and health and social care systems (primary care, substance abuse, social services, and homeless services) in the ethnically diverse South Los Angeles and Hollywood metropolitan area. Many non‐healthcare agencies were accessed by residents who also had depression, and the study aimed to establish co‐ordinated depression care across this network. Investigators compared a depression quality improvement program delivered in two ways: a coalition‐driven "community engagement" model, and a "resource support for agencies" approach without community engagement in mental health outcomes. The intervention occurred over a two‐year period and included train‐the‐trainer for quality improvement in depression care, cognitive‐behavioral therapy, and medication management, as well as development of service networks across diverse agencies.

The remaining six studies that examined broad‐scale health and social care system‐level change consisted of five controlled before‐after studies (Clark 2013; Fuller 2007; Kelaher 2009; McPhee 2003; Saxe 2006) and a prospective controlled cohort study (Melhuish 2010). Two of these studies were aimed at improving the health and development of young children in deprived areas in England through the Sure Start community‐based initiative (Melhuish 2010), and in Australia through the Best Start community initiative (Kelaher 2009). Interventions were implemented across hundreds of communities, with each program guided by a local coalition or partnership that included parents, local government, health series, education services, family support services, and community organizations such as those representing ethnic minority populations. System change strategies encompassed a range of improvements in the quality and co‐ordination of child and family support services including home visiting and outreach, childcare services, primary health care, and early childhood education and development programs. Another study, Allies Against Asthma, was a controlled before‐after evaluation of systems of asthma care for youth and adolescents in lower‐income neighborhoods of several cities (Clark 2013). Community coalitions were formed in each community with the aim of changing policies and practices regarding asthma management in minority youth by establishing asthma registries; improving reimbursement and financial incentives; improving care co‐ordination and case management; providing clinical quality improvements through provider education and use of standardized referrals, protocol, and action plans; and implementing changes in schools, childcare centers, and recreational facilities to improve asthma management. The remaining three controlled before‐after studies targeted change in systems of health and social care. One was a multi‐level intervention in Harlem, New York, that sought to increase sterile syringe access through a new policy allowing non‐prescription syringe sales in pharmacies (Fuller 2007). One study reported on the Fighting Back community initiatives implemented in several US cities, whereby multi‐sector coalitions of grass roots leaders and business and political leaders implemented a range of system level changes in prevention, treatment, and aftercare for substance abuse (Saxe 2006). One study focused on improving awareness and uptake of hepatitis B immunization for Vietnamese‐American children through community awareness and healthcare provider system changes (McPhee 2003). The average duration of these six quasi‐experimental studies was 36 months.

Lay community health outreach workers

Hiring lay health outreach workers was a strategy used in 13 studies to increase local community engagement and to reach minority community residents to facilitate health service access, increase knowledge, and promote behavior change in a culturally competent manner. Six of these studies used lay health outreach workers to contact community members, provide cancer prevention information, and facilitate access to screening services; two were randomized studies (Nguyen 2009; Wilson 2008), and four used a quasi‐experimental design (Burhansstipanov 2010; Kagawa‐Singer 2009; Moskowitz 2007; Nguyen 2006). Two randomized trials (Parker 2008; Krieger 2005) and one prospective controlled cohort study (Fisher 2004) employed lay community health workers to contact households of children with asthma and provide education, supplies, and support to reduce indoor asthma triggers. One cluster‐randomized trial paid local community organizers to raise community awareness of youth risk behaviors and to provide education about risk reduction strategies through community health fairs and other outreach venues (Cheadle 2001). One randomized controlled trial used community health workers for home visits to diagnose diabetes and teach diabetes self management (Spencer 2011). Migrant farm workers and their children at risk of pesticide exposure were the focus of a randomized trial in which "health promotoras" provided community outreach and education on abating pesticide exposure risk (Thompson 2008). One cohort study trained lay health advisors from Latino men’s soccer teams to provide HIV/AIDS prevention outreach to recent migrants in Spanish‐speaking soccer leagues (Rhodes 2009). The average duration of the 13 lay community health outreach worker interventions was 30 months.

Group‐based health education and support for targeted risk groups led by trained peers or by health professionals

Use of peer health educators to provide group‐based health education classes or workshops to targeted risk groups was the intervention strategy used in 12 studies. Four randomized studies used peer educators to reduce risk among adults of chronic disease, including cancer (Thompson 2006; Mishra 2007), cardiovascular disease (Kronish 2014), and diabetes (Parikh 2010). One randomized controlled trial trained tribal leaders to offer after‐school education to Native American youth at high risk of diabetes (Brown 2013). Two cohort studies used peer educators in church‐based settings to promote smoking cessation among African Americans (Schorling 1997; Voorhees 1996). Four controlled before‐after studies used peer health educators to increase cancer screening among Latinas (Cardarelli 2011) and Native Hawaiian women (Gotay 2000). One study (Rhodes 2011) used peer educators to reduce HIV risk and increase uptake of HIV screening among Latino men who were recent immigrants. The average duration of these peer educator interventions was five months.

Use of professional health staff to provide group‐based education and social support to targeted risk groups was evaluated in six studies. Three of these studies were randomized trials focused on chronic disease education and risk reduction for stroke survivors (Levine 2003) and people at high risk of diabetes (Merriam 2009) or cancer (Blumenthal 2010). Two studies were controlled before‐after studies evaluating group‐based health education for youth, including HIV/AIDS risk reduction (Koniak‐Griffin 2008) and risk behavior related to alcohol, drug, and tobacco use (Dedobbeleer 2001). One controlled before‐after study provided health education to the parents of children residing in low‐income neighborhoods for reducing the risk of household lead exposure (Rothman 1999). The average duration of group‐based health education programs provided by health professionals was 20 months.

Intervention costs and resources

Among the 58 studies included in this review, only eight provided information on annual costs (Brownson 1996; Clark 2013; Holder 2000; Krieger 2000; Kruger 2007; Saxe 2006; Stafford 2008; Wagner 2000a). Some studies reported the amount of grant funding the project received but provided no information beyond that.

Excluded studies

We excluded 36 studies as they had no racial or ethnic minority population, and 187 because they were not based on eligible study designs (e.g. case study, single group before‐after). See the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

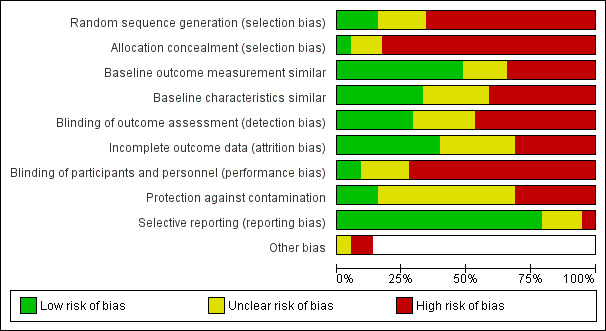

Risk of bias in included studies

Of the 58 studies reporting health outcomes, most (n = 31) were described as controlled before‐after studies. The remaining studies were described as cluster‐randomized controlled trials (n = 9), randomized controlled trials (n = 11), prospectively controlled cohort studies (n = 6), and controlled interrupted time series trials (n = 1). Given the preponderance of non‐randomized study designs included in this review, we utilized the "Risk of bias" tool developed by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group (EPOC 2015) to develop a checklist for appraising the methodological quality of studies.

We found that none of the randomized studies (n = 20) had uniformly low risk of bias. We found that only one study (Mishra 2007) had no areas with high risk of bias but was appraised as having “unclear” risk for four criteria Of the remaining randomized trials, two had only one area of high risk of bias, and the remaining had two or more areas of high risk of bias.

Among quasi‐experimental studies with a controlled cohort or before‐after design (n = 37), every study had at least one area with high risk of bias, and no study satisfied more than seven of the nine criteria with low risk of bias. Lack of random assignment to intervention groups in these studies meant that none could satisfy the random sequence generation or allocation concealment criteria.

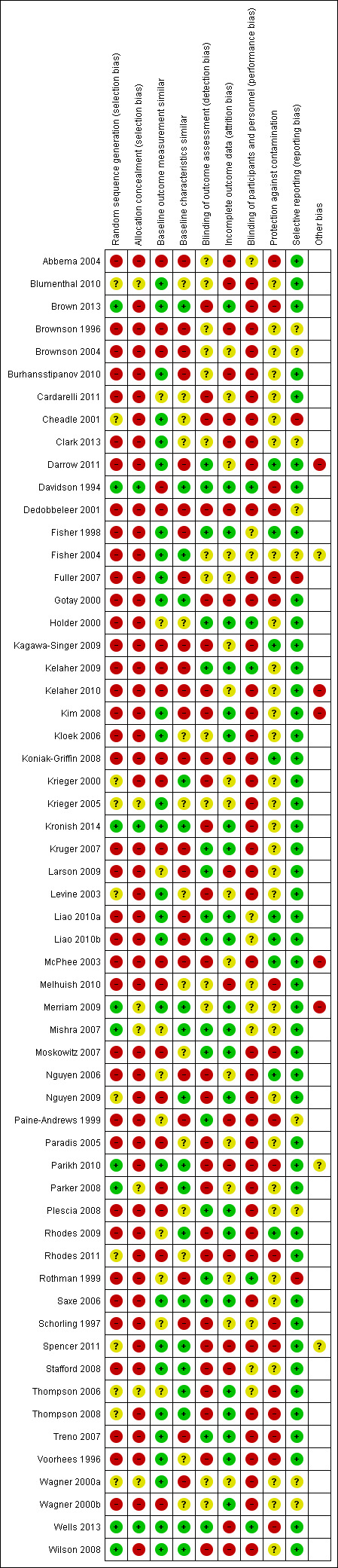

We have summarized risk of bias below by study design. Figure 3 depicts the distribution of risk of bias assessments. Figure 4 presents risk of bias for individual studies.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Randomized studies

We did not completely eliminate selection bias among the randomized trials included in this review. Less than half of these trials (n = 8) described an adequate randomization procedure, and only two (Kronish 2014; Wells 2013) described the procedure in sufficient detail to ensure allocation concealment. Despite randomization, one study (Krieger 2005) had a significant imbalance in baseline measures of one of the outcomes of interest (receipt of influenza immunization); three other studies (Mishra 2007; Parker 2008; Rhodes 2011) had an unclear risk of baseline imbalance in outcome measurements. One randomized trial presented data indicating high risk of baseline differences in participant characteristics between intervention and comparison groups (Wagner 2000a), but baseline imbalances could not be completely ruled out in six studies (Blumenthal 2010; Cheadle 2001; Krieger 2005; Levine 2003; Parker 2008; Rhodes 2011), which were appraised to have unclear risk.

Non‐randomized studies

As a result of lack of random assignment to intervention groups in these studies, none could satisfy the random sequence generation or allocation concealment criteria. Selection bias was a significant risk for most of these studies. We judged both outcome measurements and other participant characteristics as adequately balanced between intervention and control groups at baseline in only four studies (Fisher 2004; Gotay 2000; Saxe 2006; Stafford 2008). However, studies frequently described only a minimal number of baseline participant characteristics, and the comparability of groups was often difficult to assess.

Blinding

Randomized studies

In light of the nature of these community‐based interventions, we judged performance and detection bias to be at high or unclear risk for most of the randomized studies, which reported no blinding of participants or study personnel. We judged only one study as having low risk of both performance and detection bias (Wells 2013), and only two studies as having low or unclear risk in both domains (Merriam 2009; Mishra 2007). The remaining 17 randomized studies were at high risk for one (n = 5) or both domains (n = 12).

Non‐randomized studies

Non‐randomized studies did not attempt to blind participants or personnel, but we characterized three studies as having low risk on this criterion because outcome measurements not susceptible to lack of blinding were used (hospital emergency department records in Holder 2000, maternal child health indicators from state records in Kelaher 2009, blood lead levels in Rothman 1999).

Incomplete outcome data

Randomized studies

We appraised seven studies as having high risk of attrition bias because a high proportion of participants were lost to follow‐up or were missing outcome measurements (Blumenthal 2010; Cheadle 2010; Parikh 2010; Rhodes 2011; Spencer 2011; Wells 2013; Wilson 2008).

Non‐randomized studies

Attrition bias due to incomplete follow‐up or other missing outcome data was a high or unclear risk for most of the cohort studies, with only one out of six studies judged to have low risk for this criterion (Voorhees 1996). Controlled before‐after studies, using independent sampling strategies at baseline and at follow‐up, were immune to individual participant attrition but still often suffered from response rates that declined over time or differed significantly between intervention and control communities.

Selective reporting

Randomized studies

Reporting bias generally was not an issue, although information was insufficient to rule out selective reporting in two studies (Parikh 2010; Wagner 2000a).

Non‐randomized studies

Reporting bias was suspected in only one study (Rothman 1999), for which the cutoff level for a positive outcome was inconsistent between publications.

Other potential sources of bias

Risk of contamination was high or unclear in most of the studies in this review — both randomized and non‐randomized — because of proximate intervention and control groups.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Table 2 presents a summary of results reported in each study.

1. Findings on interventions to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations.

| Study ID | Primary outcomes | Secondary outcomes |

| Abbema 2004 |

|

|

| Brown 2013 | Outcomes reported as between‐group difference (Tx‐Ctrl) in mean (SD) and P value, or percent and P value

|

|

| Brownson 1996 |

|

|

| Brownson 2004 |

|

|

| Burhansstipanov 2010 |

Note: 65% of intervention group dropped from study because of change in healthcare coverage law, and if counted as unscreened, the result would be 20% |

|

| Cardarelli 2011 |

|

|

| Cheadle 2001 |

|

|

| Clark 2013 |

|

|

| Darrow 2011 |

|

|

| Davidson 1994 |

|

|

| Dedobbeleer 2001 |

|

|

| Fisher 2004 |

|

|

| Fuller 2007 |

|

|

| Gotay 2000 |

|

|

| Holder 2000 |

|

|

| Kagawa‐Singer 2009 |

|

|

| Kelaher 2009 |

|

|

| Kelaher 2010 |

|

|

| Kim 2008 |

|

|

| Kloek 2006 |

|

|

| Koniak‐Griffin 2008 |

|

|

| Kronish 2014 |

|

|

| Kruger 2007 |

|

|

| Larson 2009 |

|

|

| Levine 2003 |

|

|

| Liao 2010a |

|

|

| Liao 2010b |

|

|

| McPhee 2003 |

|

|

| Melhuish 2010 |

|

|

| Merriam 2009 |

|

|

| Mishra 2007 |

|

|

| Moskowitz 2007 |

|

|

| Nguyen 2006 |

|

|

| Nguyen 2009 |

|

|

| Paine‐Andrews 1999 |

|

|

| Paradis 2005 |

|

|

| Parikh 2010 |

|

|

| Parker 2008 |

|

|

| Plescia 2008 |

|

|

| Rhodes 2009 |

|

|

| Rhodes 2011 |

|

|

| Rothman 1999 |

|

|

| Saxe 2006 |

|

|

| Schorling 1997 |

|

|

| Spencer 2011 |

|

|

| Stafford 2008 |

|

|

| Thompson 2006 |

|

|

| Thompson 2008 |

|

|

| Treno 2007 |

|

|

| Voorhees 1996 |

|

|

| Wagner 2000a |

|

|

| Wells 2013 |

|

|

| Wilson 2008 |