Key Points

Question

Does 100 mg of fluvoxamine twice daily for 13 days, compared with placebo, shorten symptom duration among outpatient adults (aged ≥30 years) with symptomatic mild to moderate COVID-19?

Findings

In this platform randomized clinical trial with 1175 US participants enrolled during the time that Omicron COVID-19 subvariants were circulating, there was no reportable difference in the time to sustained recovery between fluvoxamine and placebo groups (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.99 [95% credible interval, 0.89-1.09]; P for efficacy = .40). Median time to sustained recovery was 10 days (95% CI, 10-11) in both the intervention and placebo group.

Meaning

Fluvoxamine, 100 mg twice daily, does not shorten the duration of symptoms in outpatient adults with mild to moderate COVID-19.

Abstract

Importance

The effect of higher-dose fluvoxamine in reducing symptom duration among outpatients with mild to moderate COVID-19 remains uncertain.

Objective

To assess the effectiveness of fluvoxamine, 100 mg twice daily, compared with placebo, for treating mild to moderate COVID-19.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The ACTIV-6 platform randomized clinical trial aims to evaluate repurposed medications for mild to moderate COVID-19. Between August 25, 2022, and January 20, 2023, a total of 1175 participants were enrolled at 103 US sites for evaluating fluvoxamine; participants were 30 years or older with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and at least 2 acute COVID-19 symptoms for 7 days or less.

Interventions

Participants were randomized to receive fluvoxamine, 50 mg twice daily on day 1 followed by 100 mg twice daily for 12 additional days (n = 601), or placebo (n = 607).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was time to sustained recovery (defined as at least 3 consecutive days without symptoms). Secondary outcomes included time to death; time to hospitalization or death; a composite of hospitalization, urgent care visit, emergency department visit, or death; COVID-19 clinical progression scale score; and difference in mean time unwell. Follow-up occurred through day 28.

Results

Among 1208 participants who were randomized and received the study drug, the median (IQR) age was 50 (40-60) years, 65.8% were women, 45.5% identified as Hispanic/Latino, and 76.8% reported receiving at least 2 doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Among 589 participants who received fluvoxamine and 586 who received placebo included in the primary analysis, differences in time to sustained recovery were not observed (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.99 [95% credible interval, 0.89-1.09]; P for efficacy = .40]). Additionally, unadjusted median time to sustained recovery was 10 (95% CI, 10-11) days in both the intervention and placebo groups. No deaths were reported. Thirty-five participants reported health care use events (a priori defined as death, hospitalization, or emergency department/urgent care visit): 14 in the fluvoxamine group compared with 21 in the placebo group (HR, 0.69 [95% credible interval, 0.27-1.21]; P for efficacy = .86) There were 7 serious adverse events in 6 participants (2 with fluvoxamine and 4 with placebo) but no deaths.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among outpatients with mild to moderate COVID-19, treatment with fluvoxamine does not reduce duration of COVID-19 symptoms.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04885530

This randomized study examines the effect of higher-dose fluvoxamine on time to sustained recovery from mild to moderate COVID-19 or progression to severe disease in nonhospitalized adults.

Introduction

Several clinical trials have studied approved medications as repurposed oral therapies for outpatients with mild to moderate COVID-19.1,2 Fluvoxamine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, has been proposed to decrease the host inflammatory response and prevent progression to severe COVID-19.3 A systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that fluvoxamine reduced hospitalization rates among adults with symptomatic COVID-19; however, this evidence was insufficient for national guidelines to recommend its use.4,5 Fluvoxamine at doses of 100 mg 2 or 3 times daily have demonstrated a reduction in emergency department visits and hospitalizations,5,6 although tolerability may be a limitation. A lower dose of 50 mg twice daily had improved tolerability,6 but this lower dose was not efficacious in 2 clinical trials.2,5,7,8

The ongoing Accelerating Coronavirus Disease 2019 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV-6) platform randomized clinical trial evaluates repurposed medications in the outpatient setting.7 A previous trial from ACTIV-6 randomly assigned 1331 adults with mild to moderate COVID-19 to receive fluvoxamine, 50 mg twice daily, or placebo for 10 days.7 The primary outcome of time to sustained recovery was not different between the fluvoxamine and placebo groups and no differences were observed in need for higher-level medical care or death. The lack of efficacy with fluvoxamine 50 mg twice daily may be due to an inadequate dose. With conflicting results across several large randomized clinical trials, there is a need to confirm the potential therapeutic benefits of fluvoxamine at the higher dosage of 100 mg twice daily.

For this study, the ACTIV-6 platform sought to evaluate the effect of higher-dose fluvoxamine (50 mg twice daily for 1 day followed by 100 mg twice daily for 12 days) on time to sustained recovery from mild to moderate COVID-19 or progression to severe disease in nonhospitalized adults.

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

ACTIV-6 is a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled platform trial to study repurposed medications for the treatment of outpatients with mild to moderate COVID-19 in the US.9 ACTIV-6 utilizes a decentralized approach for integration into diverse health care and community-based settings, including COVID-19 clinical testing and treatment programs. The complete protocol and statistical analysis plan are provided in Supplement 1 and Supplement 2.

The trial protocol was approved by a central institutional review board with review at each site. Informed consent was obtained from each participant either via written or electronic consent. An independent data and safety monitoring committee oversaw participant safety, efficacy, and trial conduct.

Participants

Since the study platform opened on June 11, 2021, more than 7500 participants have been randomized across 6 study groups. The fluvoxamine 100 mg twice daily group enrolled participants from 103 sites between August 25, 2022, and January 20, 2023. Participants were identified by individual sites or by self-referral via the central study telephone hotline. The study was closed in anticipation of achieving the prespecified sample size accrual target and, due to concerns for limited availability of study product, could not overenroll.

Study eligibility criteria at the time of screening were confirmed at the site level and included age 30 years or older, SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed with a positive polymerase chain reaction or antigen test result (including home-based testing) within the past 10 days, and actively experiencing 2 or more COVID-19 symptoms for 7 days or less from the time of consent (full eligibility criteria provided in Supplement 1). Symptoms included fatigue, dyspnea, fever, cough, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, body aches, chills, headache, sore throat, nasal symptoms, and new loss of sense of taste or smell. Individuals meeting the following criteria were excluded from participation: current or recent hospitalization for COVID-19, ongoing or planned participation in other interventional trials for COVID-19, current or recent use (within 14 days) of fluvoxamine or other selective serotonin (or norepinephrine) reuptake inhibitors or monoamine oxidase inhibitors, bipolar disorder, pregnant or breastfeeding, or known allergy or contraindications to fluvoxamine. Prior receipt of COVID-19 vaccinations and current use of approved or emergency use authorization therapeutics for outpatient treatment of COVID-19 were allowed.

Randomization

Due to the adaptive design of ACTIV-6, study drugs could be added or removed based on evolving data. Unlike previous active drugs in the platform, the open period of enrollment for fluvoxamine 100 mg did not overlap with the enrollment period of other active drugs. Consequently, the randomization process simplified to a 1:1 matched placebo randomization ratio provided by a random number generator and there was no pooled placebo contribution.

Interventions

A 13-day supply of either fluvoxamine or matched placebo, provided by the manufacturer (Apotex), was dispensed to the participant via home delivery from a centralized pharmacy. Participants were instructed to self-administer oral fluvoxamine at a dose of 50 mg (one 50-mg tablet) or matching placebo twice daily for 1 day, followed by 100 mg (two 50-mg tablets) or matching placebo twice daily for 12 days, for a total 13-day course.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was time to sustained recovery within 28 days, defined as the time from receipt of the study drug to the third of 3 consecutive days without COVID-19 symptoms.7,9 This measure was selected a priori from the 2 possible primary outcomes of the platform. The other possible primary outcome—time to hospitalization or death—transitioned to a secondary outcome when not selected as the primary outcome, per the statistical analysis plan. Participants who died during follow-up were deemed to have not recovered, regardless of whether they were without symptoms for 3 consecutive days. Secondary outcomes included 3 time-to-event end points administratively censored at day 28: time to death (number of events permitting), time to hospitalization or death (number of events permitting), and time to first health care utilization (a composite of urgent care visits, emergency department visits, hospitalization, or death). Additional secondary outcomes included mean time spent unwell through day 14 and the World Health Organization COVID-19 clinical progression scale score on days 7, 14, and 28. Quality of life measures using the PROMIS-29 (patient-reported outcomes measurement information system) are being collected through day 180 and are not included in this report.

Trial Procedures

The ACTIV-6 platform was designed to occur remotely, with all screening and eligibility procedures reported by participants and confirmed at the site level. Positive laboratory test results for SARS-CoV-2 were verified by study staff prior to randomization. During screening procedures, participants self-reported demographic information, medical history, use of concomitant medications, and COVID-19 symptoms and completed quality of life surveys. Participant-reported race and ethnicity were collected due to the disparity in the burden of COVID-19 infection carried by marginalized communities based on race and ethnicity. Participants were asked about ethnicity separately from race and were able to select any combination of race designations, including the option to not report any designation.

A centralized investigational pharmacy packaged and provided active or placebo study products via mail to the address provided by participants. Shipping and delivery information was provided by the courier.

Daily assessments were reported by participants via the study portal during the first 14 days of the study, regardless of symptom status. If participants were not recovered by day 14, the daily assessments continued until sustained recovery or day 28. Planned remote follow-up visits occurred on days 28, 90, and 120. Additional study procedure details are provided in Supplement 1.

Statistical Analysis Plan

Inferences about the primary outcome and exploratory analyses involving secondary outcomes were based primarily on covariate-adjusted regression modeling, supplemented by unadjusted models and graphical and tabular displays. Proportional hazard regression was used for the time-to-event analysis, and cumulative probability ordinal regression models were used for ordinal outcomes. Longitudinal ordinal regressions models were used to estimate the differences in mean time spent unwell, a summary that compares the number of days in the first 14 days of follow-up spent not recovered.

The planned primary end point analysis was a Bayesian proportional hazards model. The primary inferential decision-making quantity was the posterior distribution for the treatment assignment hazard ratio (HR), with an HR greater than 1 indicating a beneficial effect. If the posterior probability of benefit exceeded 0.95 during interim or final analyses, efficacy of the intervention would be met. To preserve type I error less than .05, the prior for the treatment effect parameter on the log relative hazard scale was a normal distribution centered at 0 and scaled to an SD of 0.10. All other parameter priors were weakly informative, using the software default of 2.5 times the ratio of the SD of the outcome divided by the SD of the predictor variable. The study was designed to have 80% power to detect an HR of 1.2 in the primary end point from a total sample size of 1200 participants with planned interim analyses at 300, 600, and 900 participants.

The model for the primary end point included the following predictor variables: randomization assignment, age, sex, duration of symptoms prior to study drug receipt, calendar time, vaccination status, geographical location, call center indicator, and baseline symptom severity. The proportional hazard assumption of the primary end point was evaluated by generating visual diagnostics such as the log-log plot and plots of time-dependent regression coefficients for each predictor in the model.

Secondary end points were analyzed with Bayesian regression models (either proportional hazards or proportional odds). Weakly informative priors were used for all parameters. Secondary end points were not used for formal decision-making, and no decision threshold was selected. Analyses resulting from secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory given the potential for type I errors due to multiple comparisons. The same sets of covariates used in the primary endpoint model were used in the analysis of the secondary end points, provided that the end point accrued sufficient events to be analyzed with covariate adjustment.

All available data were used to compare each active study drug vs placebo, regardless of postrandomization adherence to study protocols. The modified intention-to-treat cohort comprised all participants who were randomized, who did not withdraw before delivery of the study drug, and for whom the courier confirmed study drug delivery. Day 1 of the study was defined as the day of study drug delivery. Participants who opted to discontinue data collection were censored at the time of last contact, including those participants who did not complete any surveys or phone calls after receipt of study drug. Missing data among covariates for both primary and secondary analyses were addressed with conditional mean imputations because the amount of missing covariate data was small.

A predefined analysis examined potential variations in treatment effects based on participant characteristics. The assessment of treatment effect heterogeneity encompassed age, symptom duration, body mass index, symptom severity on day 1, calendar time (indicative of circulating SARS-CoV-2 variant), sex, and vaccination status. Continuous variables were analyzed as such, without stratifying into subgroups.

Analyses were performed with R10 statistical software (R Foundation) version 4.3 with the following primary packages: rstanarm,11,12 rmsb,13 and survival.14

Results

Study Population

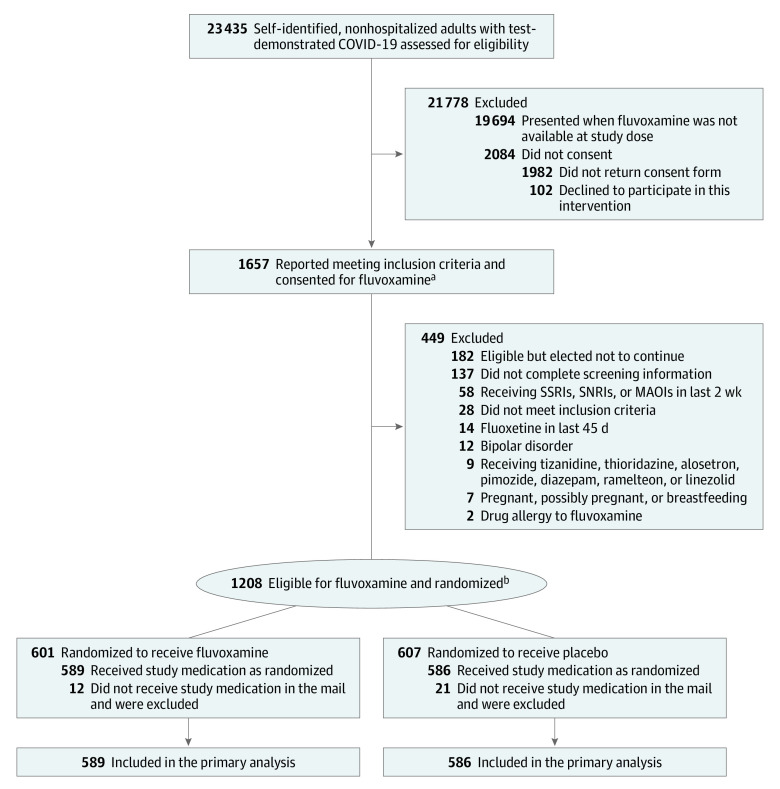

A total of 1208 participants provided written consent and were randomized to receive either fluvoxamine or placebo. A subset of 33 participants were excluded from the analysis population post randomization because the study drug was not delivered within 7 days of randomization. The modified intention-to-treat cohort included the 1175 participants who were randomized, received the study drug, and did not withdraw from the study before receiving the study drug. In the modified intention-to-treat analysis cohort, 589 participants were randomized to receive fluvoxamine and 586 participants were randomized to receive placebo (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Participant Flow in a Study of Higher-Dose Fluvoxamine in Mild to Moderate COVID-19.

MAOI indicates monoamine oxidase inhibitors; SNRI, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; and SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

aIn this platform trial with multiple study drugs, participants were able to choose what agents they were willing to be randomized to receive.

bNo additional study treatment groups were open while participants were enrolled in this study group; participants were randomized between fluvoxamine and matched placebo.

The characteristics of the participant population were similar to those observed in other ACTIV-6 cohorts (Table 1). The median (IQR) age was 50 (40-60) years; 65.8% were women; the most commonly self-reported races were Asian (4.6%), Black (9.1%), Middle Eastern (6.1%), and White (72.7%); and 45.5% of participants identified as Hispanic or Latino. The most common comorbidities were obesity (36.1%) and hypertension (25.8%). Overall, 76.8% of participants reported receiving at least 2 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine doses. Approximately 12.9% of participants reported receiving a recommended COVID-19 therapy (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Participants in a Study of Higher-Dose Fluvoxamine in Mild to Moderate COVID-19.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Fluvoxamine (n = 589) | Placebo (n = 586) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 50.0 (39.0-61.0) | 50.0 (41.0-60.0) |

| Age <50 y | 287 (48.7) | 286 (48.8) |

| Sexa | ||

| Women | 385 (65.4) | 388 (66.2) |

| Men | 204 (34.6) | 198 (33.8) |

| Raceb | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 5 (0.9) | 11 (1.9) |

| Asian | 29 (4.9) | 25 (4.3) |

| Black or African American | 55 (9.3) | 52 (8.9) |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 40 (6.8) | 32 (5.5) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.5) |

| White | 431 (73.2) | 423 (72.2) |

| None of the above | 29 (4.9) | 43 (7.3) |

| Prefer not to answer | 9 (1.5) | 15 (2.6) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 257 (43.6) | 277 (47.3) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 332 (56.4) | 309 (52.7) |

| Regionc | ||

| Midwest | 100 (17.0) | 103 (17.6) |

| Northeast | 97 (16.5) | 86 (14.7) |

| South | 321 (54.5) | 333 (56.8) |

| West | 71 (12.1) | 64 (10.9) |

| Recruited via call centerd | 17 (2.9) | 19 (3.2) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR) | 28.2 (24.9-32.1) | 28.0 (25.1-31.7) |

| Body mass index >30 | 222 (37.7) | 202 (34.5) |

| Weight, median (IQR), kg | 78.0 (68.0-91.2) | 78.0 (68.0-90.7) |

| Medical history, No./total No. (%)e | ||

| High blood pressure | 135/553 (24.4) | 150/550 (27.3) |

| Tobacco use within past year | 87/554 (15.7) | 93/550 (16.9) |

| Asthma | 77/553 (13.9) | 76/550 (13.8) |

| Diabetes | 67/554 (12.1) | 72/550 (13.1) |

| Heart disease | 35/553 (6.3) | 35/550 (6.4) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 18/553 (3.3) | 24/550 (4.4) |

| Malignant cancer | 13/549 (2.4) | 14/548 (2.6) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4/553 (0.7) | 10/550 (1.8) |

| SARS-CoV-2 vaccination status | ||

| Not vaccinated | 138 (23.4) | 133 (22.7) |

| Received 1 dose | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Received ≥2 doses | 449 (76.2) | 453 (77.3) |

| Days between symptom onset and receipt of drug, median (IQR) | 5 (4-7) | 5 (4-7) |

| Days between symptom onset and enrollment, median (IQR) | 3 (2-5) [n = 568] | 4 (2-5) [n = 562] |

| Symptom burden on study day 1, No./total No. (%)f | ||

| None | 54/542 (10.0) | 46/542 (8.5) |

| Mild | 289/542 (53.3) | 291/542 (53.7) |

| Moderate | 197/542 (36.3) | 198/542 (36.5) |

| Severe | 2/542 (0.4) | 7/542 (1.3) |

| COVID-19 medications | ||

| Remdesivir | 1 (0.2) | 0 |

| Nirmatrelvir and ritonavir | 71 (12.1) | 58 (9.9) |

| Monoclonal antibodies | 12 (2.0) | 4 (0.7) |

| Molnupiravir | 4 (0.7) | 7 (1.2) |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Participants also had the option to select “unknown,” “undifferentiated,” or “prefer not to answer.” Only those who self-identified as men or women were selected in this cohort.

Participants may have selected any combination of provided race descriptors, including “prefer not to answer.” Consequently, the sum of counts over all categories does not match the column total.

Northeast includes Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania; Midwest includes Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota; South includes Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas; and West includes Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, New Mexico, Montana, Utah, Nevada, Wyoming, Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington.

Patients may have alternatively been recruited at local clinical sites.

Medical history was provided by participants, responding to the prompts: “Has a doctor told you that you have any of the following,” “Have you ever experienced any of the following (select all that apply),” and “Have you ever smoked tobacco products.”

Each day, participants were asked to “Please choose the response that best describes the severity of your COVID-19 symptoms today” with the response options being “no symptoms,” “mild,” “moderate,” and “severe.”

Although only participants with symptoms were enrolled in the study, some participants reported no symptoms on the day of study drug delivery, which is defined as study day 1. At the time of study drug delivery, 9.2% of participants reported no symptoms, while the majority reported mild (53.5%) or moderate (36.4%) symptoms. The symptom burden for each of the 13 COVID-19–related symptoms at baseline is reported in eTable 1 in Supplement 3. Participants were enrolled within a median (IQR) of 3 (2-5) days of patient-reported symptom onset and the study drug was delivered within a median (IQR) of 5 (4-7) days of symptom onset. The complete distribution of time between onset of COVID-19 symptoms and study drug delivery is reported in eFigure 1 in Supplement 3.

Primary Outcome

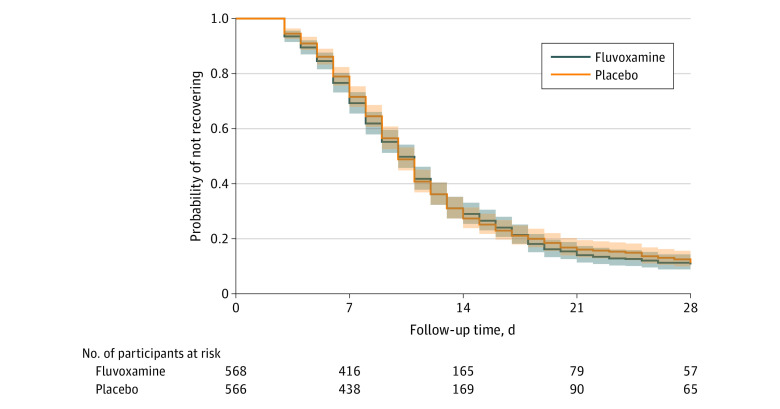

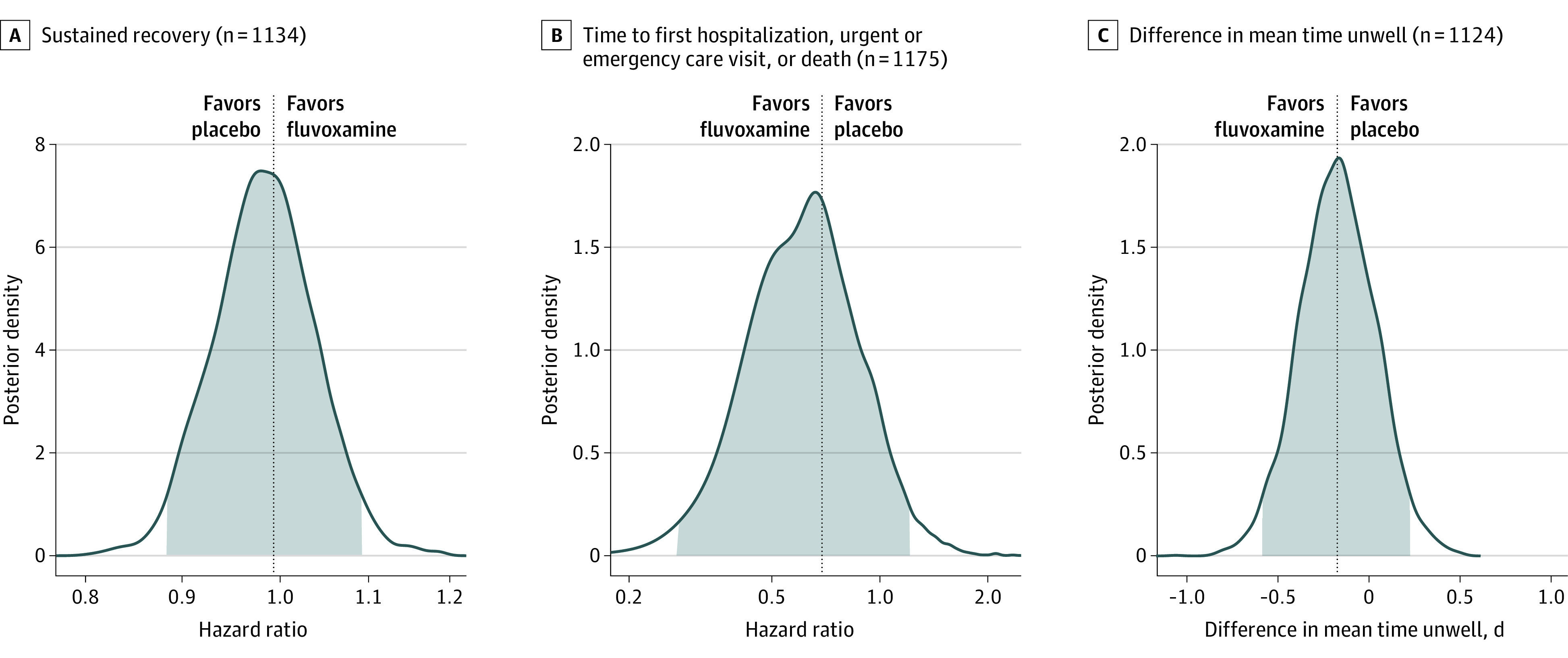

Differences in time to sustained recovery were not observed in either unadjusted Kaplan-Meier (Figure 2) or covariate-adjusted regression models (Table 2). The median time to sustained recovery was 10 days (95% CI, 10-11) in both the fluvoxamine and placebo groups. The posterior probability for benefit was 0.4, with an HR of 0.99 (95% credible interval [CrI], 0.89-1.09) (Figure 3). Sensitivity analyses yielded similar estimates of the treatment effect (eFigure 2 in Supplement 3).

Figure 2. Primary Outcome of Time to Sustained Recovery.

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes in a Study of Higher-Dose Fluvoxamine in Mild to Moderate COVID-19.

| Outcome | Fluvoxamine (n = 589) | Placebo (n = 586) | Adjusted estimate (95% credible interval [CrI])a | Posterior P value for efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary end point: time to sustained recoveryb | ||||

| Skeptical prior (primary analysis) | HR, 0.99 (0.89 to 1.09) | .40 | ||

| Noninformative prior (sensitivity analysis) | HR, 0.98 (0.86 to 1.11) | .38 | ||

| No prior (sensitivity analysis) | HR, 0.98 (0.86 to 1.11)c | |||

| Secondary end pointsd | ||||

| Hospitalization, urgent care, emergency department visit, or death through day 28, No. (%)e | 14 (2.38) | 21 (3.58) | HR, 0.69 (0.27 to 1.21) | .86 |

| Mortality at day 28, No. (%) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Hospitalization or death through day 28, No. (%) | 1 (0.17) | 2 (0.34) | HR, 0.51 (0.05 to 5.64)c | |

| Clinical progression ordinal outcome scalef | ||||

| Day 7 (n = 1026) | OR, 1.15 (0.51 to 1.83) | .38 | ||

| Day 14 (n = 1026) | OR, 0.66 (0.23 to 1.16) | .90 | ||

| Day 28 (n = 1018) | OR, 0.94 (0.29 to 1.74) | .63 | ||

| Mean time unwell (95% CrI), dg | 11.28 (11.06 to 11.50) | 11.45 (11.24 to 11.66) | difference, −0.17 (−0.58 to 0.23) | .79 |

Adjustment variables for time to sustained recovery, mortality, composite clinical endpoints, and clinical progression in addition to randomization assignment: age (as restricted cubic spline), sex, duration of symptoms prior to receipt of study drug, calendar time (as restricted cubic splines), vaccination status, geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), call center indicator, and baseline symptom severity.

Time to sustained recovery is from receipt of study drug to achieving the third of 3 days of recovery. A hazard ratio (HR) greater than 1.0 is favorable for faster recovery for fluvoxamine compared with placebo.

Low event rate precluded covariate adjustment, so maximum partial likelihood estimate is provided (no prior).

For secondary outcomes, an HR or odds ratio (OR) less than 1 favors fluvoxamine and a difference in mean values less than 0 favors fluvoxamine.

A priori death was a component of the composite outcome, but no deaths were observed.

The COVID-19 clinical outcome scale ranges from 0 (no clinical or virological evidence of infection) to 8 (death), with higher scores indicating more severe illness. See Supplement 2 for a full description.

Adjustment variables for mean time unwell in addition to randomization assignment included age and calendar time.

Figure 3. Time to Sustained Recovery, Health Care Use, and Mean Time Unwell.

Secondary Outcomes

No deaths were observed in either group; 1 participant in the fluvoxamine group and 2 in the placebo group were hospitalized (Table 2; eFigure 3 in Supplement 3). There were 14 participants (2.4%) in the fluvoxamine group and 21 (3.6%) in the placebo group who reported hospital admission or emergency department or urgent care visits (Table 2; eFigure 4 in Supplement 3). Analyzed as a time-to-first-event outcome, the HR for the composite health care outcome was 0.69 (95% CrI, 0.27-1.21) with a posterior probability of efficacy of 0.86 (Figure 3).

With clinical events such as hospitalizations and death being rare among participants, the COVID-19 clinical progression scale (Supplement 3) simplified into a self-reported evaluation of home activity levels (limited vs not limited) collected on study days 7, 14, and 28 (eFigure 5 in Supplement 3). By day 7, more than 95% of responding participants reported no limitations in activity, thus this end point did not meet prespecified thresholds for beneficial treatment effect. Likewise, the difference in mean time unwell was similar between the fluvoxamine and placebo groups (11.3 [95% CI, 11.1-11.5] days vs 11.5 [95% CI, 11.2-11.7]; 95% CrI, −0.58 to 0.23; P for efficacy] = .79). (Figure 3)

Adverse Events and Tolerability

Seven serious adverse events were reported in 6 participants (eTable 2 in Supplement 3), all of whom reported taking the study medication at least once. Three events in 2 participants were reported in the fluvoxamine group, including aggravated asthma, community-acquired pneumonia, and Guillain-Barre syndrome. Four participants in the placebo group reported 1 serious adverse event each, including ruptured appendix, diabetic foot ulcer, partial bowel obstruction, and perforated intestinal diverticulitis. The incidence of serious events was low without evidence of higher events in the intervention group.

Among participants who provided adherence data, 36 of 561 (6.4%) in the fluvoxamine group compared with 13 of 563 (2.1%) in the placebo group reported at least once “I am not planning to take my medicine because I feel worse,” consistent with a prior hypothesis that fluvoxamine may not be universally tolerated, especially at higher doses.

Heterogeneity of Treatment Effect Analyses

When stratified by baseline symptom severity and the timing of treatment relative to the onset of symptoms, no meaningful separation between participants in the fluvoxamine vs the placebo group was observed in the distribution of the primary outcome (eFigure 6 in Supplement 3). Likewise, exploratory analyses were completed to understand how the treatment effect for the primary outcome may vary with a priori defined patient characteristics. Results of the analysis suggests the possibility that participants who received fluvoxamine sooner after symptom onset faired poorer than those who received placebo (eFigure 7 in Supplement 3), whereas participants who received fluvoxamine approximately 7 days after symptom onset may have had better symptom resolution than placebo (interaction P value = .05). In additional exploratory analyses without covariate adjustment, the differences in sustained recovery between those who received the study drug within 3 days of symptom onset and those who received the study drug on days 6 to 8 were plotted and are provided in eFigure 8 in Supplement 3.

Discussion

Among outpatient adults with mild to moderate COVID-19, treatment with fluvoxamine 100 mg twice daily for 13 days, compared with placebo, did not improve time to sustained recovery in this trial of 1175 participants. The present study is one in a series of trials investigating fluvoxamine as a potential treatment for COVID-19 in an outpatient setting. The STOP COVID5 (n = 152), TOGETHER6 (n = 1497), and COVID OUT2 (n = 661) trials were designed around clinical events such as death, hospitalization, hypoxemia, and emergency department visits. The TOGETHER trial was stopped early for superiority of fluvoxamine 100 mg twice daily, compared with placebo, with a 32% reduction in the primary composite end point of hospitalization or extended care in an emergency setting.5 A follow-up TOGETHER trial (n = 1476) testing fluvoxamine 100 mg twice daily with inhaled budesonide in a majority-vaccinated population demonstrated a 50% reduction in the same composite end point.8 In contrast, the COVID-OUT and ACTIV-6 trials studying fluvoxamine 50 mg twice daily did not identify a benefit for fluvoxamine.2 Among these studies, ACTIV-6 is the only trial with a primary outcome of patient-reported sustained recovery and, in this trial of fluvoxamine 100 mg twice daily for 13 days, there was no evidence of benefit. A secondary composite outcome of death or health care use (including urgent care or emergency department visits or hospitalizations) suggested one-third fewer events in the fluvoxamine group compared with placebo. This difference did not meet prespecified decision-making thresholds.

The evolution of the pandemic, with changes in the severity of COVID-19 over time and increasing infection-related and/or vaccine-induced immunity, suggests that the circumstances of the present study are meaningfully different than those of earlier trials. COVID-19 severity has decreased over time with lower rates of hospitalization and death as partial immunity has increased. If clinical event rates for death or hospitalizations continue to decline, future trials may need to focus on composite outcomes such as health care utilization or enroll a larger number of participants to conclusively understand the impact of any therapeutic agent on outcomes. Testing time to recovery in clinical trials remains appealing because symptom reduction is a clinically relevant and patient-centric outcome; however, several medications, including nirmatrelvir, metformin, and molnupiravir, do not reduce symptom duration while showing clinical benefit.2,15

Exploratory findings from the heterogeneity of treatment effect analysis prompt the hypothesis that participants receiving fluvoxamine later in the course of their COVID-19 infection may have had more rapid symptom resolution compared with placebo in contrast to the difference between those who received the drug earlier in the course of disease. A plausible hypothesis is that the immune-modulating activity of fluvoxamine may not be beneficial until the latter stage of disease when the host experiences dysregulated immune responses.16

A strength of this study is the improved ethnic diversity, with 45% of participants identifying as Hispanic/Latino ethnicity. The pandemic exposed significant health disparities, with a large burden of more severe disease outcomes being reported from underrepresented and marginalized populations including Black and Hispanic/Latino communities.17,18,19 This increased diversity in the ACTIV-6 trial came from a concerted national effort to improve recruitment strategies, prioritize Spanish-language document translation, and onboard sites already engaged with diverse communities.

Limitations

The trial has several limitations. First, due to the evolving nature of the pandemic and the population enrolled, few clinical events occurred, limiting the ability of the trial to study the treatment effect on clinical outcomes either as a primary or secondary outcome. Second, the remote nature of the trial, while, in part, a strength, is also a limitation. The decentralized approach in theory expands access by allowing participation regardless of geographic location. An important limitation of the remote design is that study drug must be sent by courier, which resulted in a median of 2 additional days between symptom onset and receipt of the study drug, which may be particularly relevant for a proposed antiviral mechanism of action. Although the study design allowed enrollment within 7 days of symptom onset, the median time from symptom onset to enrollment was 3 days. This limitation is further addressed by including time from symptom onset to receipt of study drug in the heterogeneity of treatment effect analysis.

Conclusions

Among outpatient adults with mild to moderate COVID-19, treatment with fluvoxamine 100 mg twice daily, compared with placebo, did not improve time to sustained recovery. Although one-third fewer health care use events occurred in the fluvoxamine intervention group, the difference did not meet prespecified decision thresholds for concluding a treatment effect.

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eMethods, eTables, and eFigures

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Venkatesan P. Repurposing drugs for treatment of COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(7):e63. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00270-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bramante CT, Huling JD, Tignanelli CJ, et al. ; COVID-OUT Trial Team . Randomized trial of metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(7):599-610. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2201662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sukhatme VP, Reiersen AM, Vayttaden SJ, Sukhatme VV. Fluvoxamine: a review of its mechanism of action and its role in COVID-19. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:652688. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.652688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines . National Institutes of Health. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/

- 5.Lenze EJ, Mattar C, Zorumski CF, et al. Fluvoxamine vs placebo and clinical deterioration in outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2292-2300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reis G, Dos Santos Moreira-Silva EA, Silva DCM, et al. ; TOGETHER investigators . Effect of early treatment with fluvoxamine on risk of emergency care and hospitalisation among patients with COVID-19: the TOGETHER randomised, platform clinical trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(1):e42-e51. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00448-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy MW, Naggie S, Boulware DR, et al. ; Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV)-6 Study Group and Investigators . Effect of fluvoxamine vs placebo on time to sustained recovery in outpatients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;329(4):296-305. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.24100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reis G, Dos Santos Moreira Silva EA, Medeiros Silva DC, et al. Oral fluvoxamine with inhaled budesonide for treatment of early-onset COVID-19: a randomized platform trial. Ann Intern Med. 2023;176(5):667-675. doi: 10.7326/M22-3305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naggie S, Boulware DR, Lindsell CJ, et al. ; Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV-6) Study Group and Investigators . Effect of ivermectin vs placebo on time to sustained recovery in outpatients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;328(16):1595-1603. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.18590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodrich B, Gabry J, Ali I, Brilleman S. Bayesian Applied Regression Modeling via Stan [R Package Rstanarm]. R Foundation; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brilleman SL, Elci EM, Novik JB, Wolfe R. Bayesian survival analysis using the rstanarm R package. arXiv. 2020. doi: 10.48550/arxiv.2002.09633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrell F. Bayesian Regression Modeling Strategies [R Package Rmsb]. The Comprehensive R Archive Network; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Therneau TM. Survival Analysis [R Package Survival]. The Comprehensive R Archive Network; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan Y, Puenpatom A, Johnson MG, et al. Impact of molnupiravir treatment on patient-reported coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) symptoms in the phase 3 MOVe-OUT trial: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis . Published online June 19, 2023. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashimoto Y, Suzuki T, Hashimoto K. Mechanisms of action of fluvoxamine for COVID-19: a historical review. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(4):1898-1907. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01432-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.COVID-19 provisional counts: health disparities . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/health_disparities.htm

- 18.Lopez L III, Hart LH III, Katz MH. Racial and ethnic health disparities related to COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(8):719-720. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acosta AM, Garg S, Pham H, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in rates of COVID-19-associated hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, and in-hospital death in the united states from March 2020 to February 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2130479. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.30479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eMethods, eTables, and eFigures

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement