Highlights

-

•

The expression of ZHX3 was significantly downregulated in colorectal cancer (CRC) tissues and showed a strong correlation with tumor size, tumor invasion depth, and TNM stage.

-

•

Low ZHX3 expression was associated to with poorer overall survival and disease-free survival in CRC patients.

-

•

The expression of ZHX3 was found to have an impact on the proliferation of CRC cells both in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: ZHX3, Colorectal cancer, Immunohistochemistry, Recurrence, Prognosis

Abstract

Accumulating studies suggest that ZHX3, the member of ZHX family, is involved in a variety of biological functions such as development and differentiation. Recently, ZHX3 may also be involved in the progression of several cancer types including renal cancer, gastric cancer, liver cancer and breast cancer. However, the potential role of ZHX3 in colorectal cancer (CRC) is still unknown. In this study, we analyzed the protein levels of ZHX3 by immunohistochemistry and evaluated its relationship with the clinicopathological features and prognosis in 286 CRC patients. In vitro cell proliferation assay, plate colony formation assay and xenograft model in nude mice were applied to evaluate CRC cell proliferative ability. Our results showed that the expression of ZHX3 was significantly downregulated in CRC tissues compared with paired adjacent nontumor tissues. Furthermore, the ZHX3 expression was found to have a strong correlation with tumor size, tumor invasion depth and TNM stage. Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that low ZHX3 expression was related to a poorer overall survival and disease-free survival in CRC patients. In addition, cox's proportional hazards analysis indicated that low ZHX3 expression was an independent prognostic indicator of poor prognosis. Functionally, reduced expression of ZHX3 promotes the proliferation of CRC cells both in vitro and in vivo. Conversely, overexpression of ZHX3 inhibited the growth of CRC cells, indicated that ZHX3 was significantly correlated with CRC progression. Our results indicate for the first time that ZHX3 may be a potential marker of cancer prognosis and CRC recurrence.

Abbreviations

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- ZHX3

zinc finger and homeobox 3

- NF-YA

nuclear factor Y

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- DFS

disease-free survival

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) has a high incidence and mortality rate, ranking third and second, respectively, among all cancers in 2020 [1], [2], [3], [4]. The prevalence of CRC is rapidly increasing, resulting in a massive cancer burden in China [5,6]. Currently, surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy are the most common treatments for CRC [7], [8], [9]. However, it is important to note that although colon and rectal cancers are often considered as a single entity, the treatment strategies for rectal cancer differ significantly from those for colon cancer. Some researchers have pointed out that for patients with stage II and III rectal cancer, it is recommended to undergo neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy before radical resection. This approach helps in reducing the risk of recurrence and metastasis [10,11]. Additionally, research reports indicate that preoperative radiotherapy, with or without chemotherapy, is necessary for achieving acceptable local control of rectal cancer [12]. In this regard, dynamic perfusion magnetic resonance imaging plays a crucial role in tumor grading and assessing post-treatment outcomes for rectal cancer. Ciolina et al. discovered that dynamic perfusion magnetic resonance imaging parameters can serve as imaging biomarkers to predict the aggressiveness of locally advanced rectal cancer and the effectiveness of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy [13].

Despite significant advancements in therapeutic procedures in recent years, treatment outcomes remain unsatisfactory [14,15]. Chemotherapy resistance is a significant challenge in anti-tumor treatment, and its underlying mechanisms are highly intricate. [16].The current clinical tumor biomarkers for CRC such as carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, and carbohydrate antigen 125 still lack high accuracy [17,18]. Thus, novel biomarkers that could serve as therapeutic targets or prognostic indicators for patients with CRC are urgently needed. Zinc finger and homeobox 3 (ZHX3), a member of ZHX family, consists of two zinc-finger motifs and five homeobox DNA-binding domains which is found in the cell nucleus [19]. The transcriptional repressor ZHX3 can form homodimers and heterodimers with the subunit of nuclear factor Y (NF-YA) [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. Accumulating researches have shown that the ZHX3 factor, acting as transcriptional mediator, plays crucial roles in biological processes such as development, differentiation and senescence [20,[26], [27], [28]]. Recently, ZHX3 may also be involved in the progression of several cancer types including renal cancer [29], gastric cancer [19], liver cancer [30], urothelial carcinoma of the bladder [31], and breast cancer [32], according to the data from relevant investigations. However, the potential role of ZHX3 in CRC is still unknown.

To clarify the role of ZHX3 in CRC, we investigated the expression level of ZHX3 in clinical samples and analyzed the effect of ZHX3 on the prognosis of patients with CRC in the present study. In addition, in vitro and in vivo experiments confirmed the role of tumor suppressor of ZHX3. Overall, our findings suggest that ZHX3 may be a potential biomarker and promising prognostic factor for CRC.

Materials and methods

Clinical sample collection and cell culture

Clinical samples were collected from 286 patients from department of General Surgery of Zhujiang Hospital affiliated with the Southern Medical University in Guangzhou, China. Patients with CRC who underwent radical surgery for colorectal cancer were included in this study. Written informed consent was signed by all participants or family members prior to participation. All histological diagnosis of CRC involved in the study were confirmed by pathology. The exclusion criteria were as follows: age less than 18 years or more than 80 years; pregnant women; refused to sign the consent form; the patient received preoperative treatment, including neoadjuvant chemotherapy; diagnosed with colorectal stromal tumor; diagnosed with other cancers. The follow-up data are updated every three months. This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Southern Medical University. For cell culture, CRC cells LoVo and SW620 were obtained from Shanghai Cell Bank (Shanghai, China) and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10 % fetal bovine serum. Cells were incubated at 37 degrees Celsius in a 5 % carbon dioxide environment with regular medium changes.

Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemical staining experiments was performed in CRC, paired adjacent nontumor tissues and nude mice xenograft tumor tissues. Fresh tissue was embedded in paraffin after being treated in 10 % formalin. Four-millimeter-thick tissue slices were used for immunohistochemical staining. Tissue sections were dewaxed with xylene and hydrated in graded ethanol. Paraffin sections were heated in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (PH=6) to retrieve antigens. After natural cooling, the sections were quenched in 3 % H2O2 for 15 min. The sections were then incubated in normal goat serum for 20 min at room temperature after washes with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The primary antibodies (ZHX3, ab99353 at 1/1000; and Ki67, ab15580 at 1/1000) were incubated overnight at 4 °C. After washing, biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody and streptavidin peroxidase were used for 30 min at 37 °C. After washing, the sections were stained with fresh diaminobenzidine (DAB) for 5 min. The slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin for 1 min after washes with distilled water. Finally, the sections were dehydrated and sealed with neutral gum. The sections were blind examined by two trained pathologists. The ZHX3 expression level was evaluated according to the proportion and intensity of positive staining cells in five microscopic fields per slide. The scoring system for tumor cell positivity rate is as follows: 0–9 % corresponds to 0 points, 10–25 % corresponds to 1 point, 26–50 % corresponds to 2 points, 51–75 % corresponds to 3 points, and 76–100 % corresponds to 4 points. Similarly, the scoring system for cell staining intensity is as follows: no staining corresponds to 0 points, weak staining corresponds to 1 point, moderate staining corresponds to 2 points, and strong staining corresponds to 3 points. The total score is the product of the proportion and the intensity score that varied from 0 to 12.

Measurement of study endpoints

Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time period from resection to first disease relapse or progression. This included the following events: recurrence of CRC, metastasis at a distance, occurrence of a second non-CRC excluding skin basal cell carcinoma skin and carcinoma-in-situ of the cervix, or death not related to cancer. Overall survival was measured as the time from surgery to death of patients with CRC or last follow up. Deaths were verified by review of medical records, death certificates and reports from family members. The above survival analysis was performed by experienced investigators who were blind to the data about the study.

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Biorad CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Biorad) was used to carry out qRT-PCR analysis. In short, total RNA from CRC and paired adjacent nontumor tissues was extracted with RNA extraction kit (Biomed-tech, Beijing, China). Then total RNA was reversely transcribed into cDNA with the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Invitrogen). Relative expression levels of ZHX3 were evaluated through qRT-PCR analysis. The forward primer sequence for GAPDH was 5’-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3’ and the reverse primer was 5’-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3’. The forward primer sequence for ZHX3 primer was 5’-TGTCACTCATCCCTGGTTCC-3’ and reverse primer was 5’-CTCCTCACTCCTGCTGACAA-3’.

Western blot analysis

Proteins of CRC cells were extracted by using RIPA Lysis buffer with proteinase inhibitors. Then proteins were separated by gel electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membrane. The membranes were incubated with primary antibody against ZHX3 (ab99353 at 1/1000),ZHX1 (ab168522 at 1/1000),ZHX2(ab205532 at 1/1000) and β-actin (ab8226 at 1/3000) overnight at 4 °C. HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was applied at room temperature for 1 hour. Protein signal was detected using standard chemiluminescence to analyze the protein expression.

Forced and knockdown expression of ZHX3 expression

For ZHX3 knockdown, a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting sequence for ZHX3 (5’-CCCACAATTACGGTTCTAAAT-3’) were ligated into the pSilencerTM 3.1-H1 puro vector. For ZHX3 overexpression, the coding sequence was amplified from cDNA derived from LoVo cells using primers (ZHX3-sense: 5’- TGTCACTCATCCCTGGTTCC-3’;ZHX3-antisense:5’-CTCCTCACTCCTGCTGACAA-3’)and cloned into the pcDNA™3.1(+) vector (Invitrogen).Stably transfected cell lines with ZHX3 knockdown were selected by G418. The ZHX3-specific siRNA (siZHX3-1, 5’-CCCAUUAACACUGUGUGUU CA-3’; siZHX3-2, 5’-CCAUGACAUGACCCAAUUUGU-3’ and negative control siRNA, 5’-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3’) were designed and synthesized by Guangzhou RiboBio (RiboBio Inc, China). Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used to transfect plasmids and siRNA into CRC cells, as directed by the manufacturer.

In vitro cell proliferation assay

Forty eight hours after transfection, LoVo and SW620 cells in log-phase were seeded at a density of 0.25 × 104 cells per well in 24-well plates. Cells were counted on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 with a Countess® Automated Cell Counter (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The experiments were performed three times independently with three replications per experiment.

Plate colony formation assay

Plate colony formation assay was applied to evaluate CRC cell colony formation ability. In brief, cells were plated in a 6-well plate containing nearly 1000 cells/well. Then the cells were incubated for 14 days until colony was visible. Subsequently, the cells were stained with 0.1 % crystal violet after carefully washed. These studies were carried out three times.

Cell cycle analysis

The implementation of the cell cycle assays followed the guidelines provided by the cell cycle detection kit (Beyotime,China) . Initially, the collected cells were fixed in 70 % ethanol at a low temperature of 4 °C and incubated overnight. Subsequently, the cells underwent two rounds of cold PBS solution washes and were treated with RNase A for one hour. Afterward, staining with propidium iodide (PI) was conducted on the cells for 30 min. The stained cells were immediately analyzed and detected using a flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, CA, USA).

Xenograft model in nude mice

To establish the xenograft tumor model, 1 × 107 LoVo CRC cells were injected subcutaneously into the flank of 4–6 week-old BALB/c nude mice. The width and length of the subcutaneous tumor were measured every 4 days and tumor volume was calculated as follows: tumor volume = length × width × width/2. After 30 days, these subcutaneous tumors were harvested and photographed. All animal handling was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Southern Medical University.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 19.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Pearson chi-square test was performed to assess the associations between categorical variables. The correlation coefficients were calculated using the Spearman correlation analysis. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between curves were evaluated by the log-rank test. The independent factors on disease-free and overall survival were evaluated by Cox proportional hazards modeling. The difference between two groups was analyzed using the student's t test. All tests with P value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

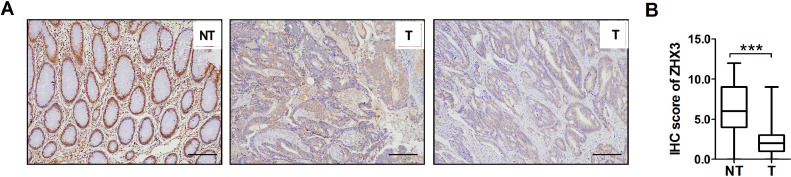

ZHX3 expression of mRNA and protein levels in CRC tissues

In this study, ZHX3 expression was detected using immunohistochemistry and quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Immunohistochemical staining showed that ZHX3 was localized in the nucleus as shown in Fig. 1A. The results of immunohistochemical scoring indicated that the expression of ZHX3 was significantly decreased at the protein level in human CRC tissues than that of paired adjacent non-tumor samples (Fig. 1B). Together, these results suggest that the expression of ZHX3 was significantly downregulated in CRC tissues and the abnormal expression of ZHX3 may affect the biological behavior of CRC.

Fig. 1.

A significant low-expression of ZHX3 in CRC tissues. (A) IHC detection of ZHX3 expression in 286 pairs of CRC samples and adjacent non-tumor tissues. Left panels indicate high expression of ZHX3 in adjacent non-tumor tissues. Middle and right panels indicate low expression of ZHX3 in CRC. Scale bar, 100μm. **P < 0.001. (B) ZHX3 expression levels were compared with CRC and paired adjacent non-tumorous specimens. **P < 0.01.

The association of ZHX3 expression and clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with CRC

Next, clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with CRC and the association with ZHX3 expression were analyzed. As shown in Table 1, the expression of ZHX3 was significantly correlated with tumor size (p = 0.006). Furthermore, the ZHX3 expression was found to have a strong correlation with tumor invasion depth (p = 0.004) and TNM stage (p = 0.013). However, associations regarding gender (p = 0.535), age at diagnosis (p = 1.000), tumor site (p = 0.391), lymph node metastasis (p = 0.547) or distant metastasis (p = 0.167) were not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Relationship between tumor ZHX3 expression and clinic features.

| Variables | No. of cases | ZHX3 expression | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | |||

| All | 286 | 143 | 143 | |

| Age | 1.000 | |||

| < 60 | 129 | 65 | 64 | |

| > = 60 | 157 | 78 | 79 | |

| Gender | 0.535 | |||

| Female | 100 | 53 | 47 | |

| Male | 186 | 90 | 96 | |

| Tumor site | 0.391 | |||

| Colon | 180 | 94 | 86 | |

| Rectum | 106 | 49 | 57 | |

| Tumor size | 0.006 | |||

| < 5.0 cm | 160 | 68 | 92 | |

| > = 5 cm | 126 | 75 | 51 | |

| Differentiation grade | 0.184 | |||

| Well | 9 | 3 | 6 | |

| Moderately | 249 | 122 | 127 | |

| Poor | 28 | 18 | 10 | |

| Depth of invasion | 0.004 | |||

| T1+T2 | 137 | 56 | 81 | |

| T3+T4 | 149 | 87 | 62 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.547 | |||

| Absent | 170 | 82 | 88 | |

| Present | 116 | 61 | 55 | |

| Distant metastasis | 0.167 | |||

| Absent | 217 | 103 | 114 | |

| Present | 69 | 40 | 29 | |

| TNM stage | 0.013 | |||

| I+ II | 134 | 56 | 78 | |

| III+ IV | 152 | 87 | 65 | |

Abbreviations: TNM, tumor-nodes-metastases; P valu, when expression levels were compared using Pearson χ2 test and P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

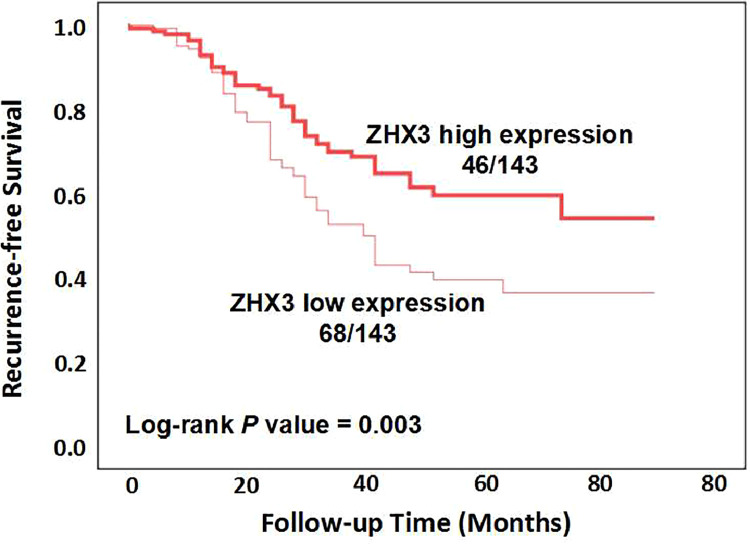

The association of ZHX3 expression and disease-free survival

Since ZHX3 expression is associated with TNM stage of CRC, we next analyzed the correlation of ZHX3 expression with disease-free survival of patients with CRC. In Fig. 2, at the conclusion of the study, it was found that out of the patients who had high ZHX3 expression, 46 patients experienced tumor recurrence, while the remaining patients did not. On the other hand, among the patients with low ZHX3 expression, 68 patients had tumor recurrence, while the rest did not. The results of Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that CRC patients with decreased ZHX3 expression had reduced disease-free survival compared to those with increased expression (Fig. 2, log-rank p = 0.003), indicating that CRC patients with low levels of ZHX3 expression had higher risk of recurrence than those with high ZHX3 expression. Then we used univariate and multivariate analyses to evaluate whether ZHX3 expression is an independent factor for disease-free survival. Univariate analysis indicated that ZHX3 expression (p = 0.004), tumor size (p = 0.003), tumor depth of invasion (p < 0.001) and TNM stage (p < 0.001) were associated with disease-free survival. Next, the Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariate analysis. Similarly, the results of multivariate analysis showed that ZHX3 expression (p = 0.006), tumor size (p = 0.028), tumor depth of invasion (p = 0.001) and TNM stage (p = 0.001) were presented as independent factors for disease-free survival (Table 2). The above results showed that patients with low ZHX3 expression had a higher incidence of relapse compared to those with ZHX3 high expression.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve analysis of ZHX3 expression on disease-free survival in CRC patients. The difference significance was calculated by using Log-rank test.

Table 2.

Association of ZHX3 and clinical factors with disease-free survival.

| Unadjusted HR* (95 % CI) | P | Unadjusted HR† (95 % CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZHX3 low expression | 0.573(0.393–0.833) | 0.004 | 0.577(0.389–0.855) | 0.006 |

| Gender | 0.877(0.601–1.279) | 0.496 | - | - |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.055(0.727–1.531) | 0.777 | - | - |

| Tumor site | 1.151(0.783–1.691) | 0.474 | - | - |

| Tumor size | 1.743(1.2042–2.524) | 0.003 | 1.531(1.047–2.239) | 0.028 |

| Depth of invasion | 2.068(1.413–3.027) | <0.001 | 1.940(1.322–2.846) | 0.001 |

| TNM stage | 2.554(1.724–3.784) | <0.001 | 1.955(1.328–2.879) | 0.001 |

Hazard ratios in univariate models

Hazard ratios in multivariable models

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

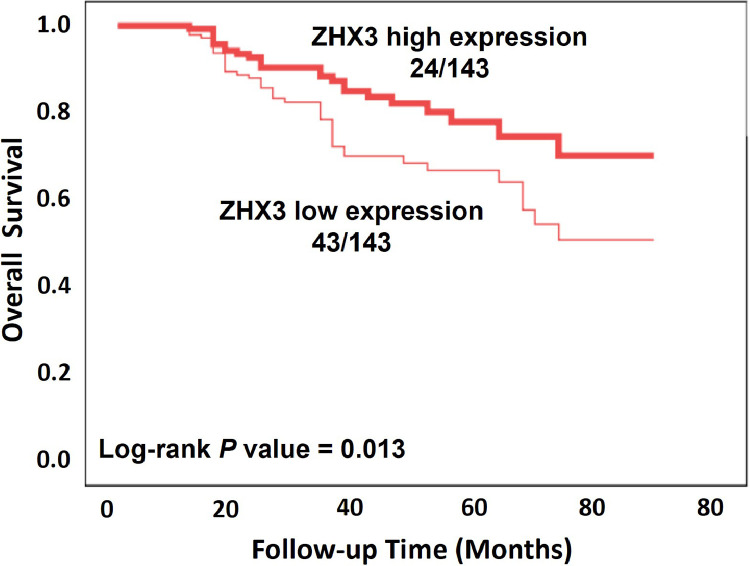

Association between ZHX3 expression and overall survival of CRC patients

Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to assess the association between ZHX3 expression and survival of CRC patients. In Fig. 3, at the end of the study, it was observed that out of the patients with high ZHX3 expression, 24 patients died due to CRC, and the rest are still alive. Similarly, among the patients with low ZHX3 expression, 43 patients died due to CRC causes, while the remaining patients were alive. Similar to the effect of ZHX3 expression on disease-free survival, the results showed that patients with ZHX3 low expression had a shorter overall survival, whereas high expression of ZHX3 predicted longer overall survival (Fig. 3). At the same time, we show that ZHX3 low expression (p = 0.001), tumor size (p < 0.001), depth of invasion (p = 0.001), and TNM stage (p = 0.001) were positively correlated with overall survival in univariate analysis (Table 3). However, the results did not show statistically significant association between gender, age, or tumor site and overall survival. In addition, multivariate analysis showed that low expression of ZHX3 was an independent factor of poor prognosis (p = 0.014). Similarly, tumor size (p = 0.004), tumor depth of invasion (p = 0.005) and TNM stage (p = 0.001) were also significantly associated with unfavorable overall survival. However, similar to the results of disease-free survival, no apparent associations were found between overall survival and gender, age, or tumor site (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve analysis of ZHX3 expression on overall survival in CRC patients. The difference significance was calculated by using Log-rank test.

Table 3.

Association of ZHX3 and clinical factors with overall survival.

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) * | P | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) † | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZHX3 low expression | 0.406(0.241–0.684) | 0.001 | 0.510(0.298–0.873) | 0.014 |

| Gender | 0.935(0.571–1.531) | 0.788 | - | - |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.974(0.602–1.575) | 0.914 | - | - |

| Tumor site | 0.935(0.575–1.522) | 0.788 | - | - |

| Tumor size | 2.686(1.621–4.450) | <0.001 | 2.169(1.281–3.671) | 0.004 |

| Depth of invasion | 2.458(1.469–4.114) | 0.001 | 2.110(1.253–3.5543) | 0.005 |

| TNM stage | 2.462(1.457–4.158) | 0.001 | 2.506(1.480–4.246) | 0.001 |

Hazard ratios in univariate models

Hazard ratios in multivariable models

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; 95 % CI, 95 % confidence interval.

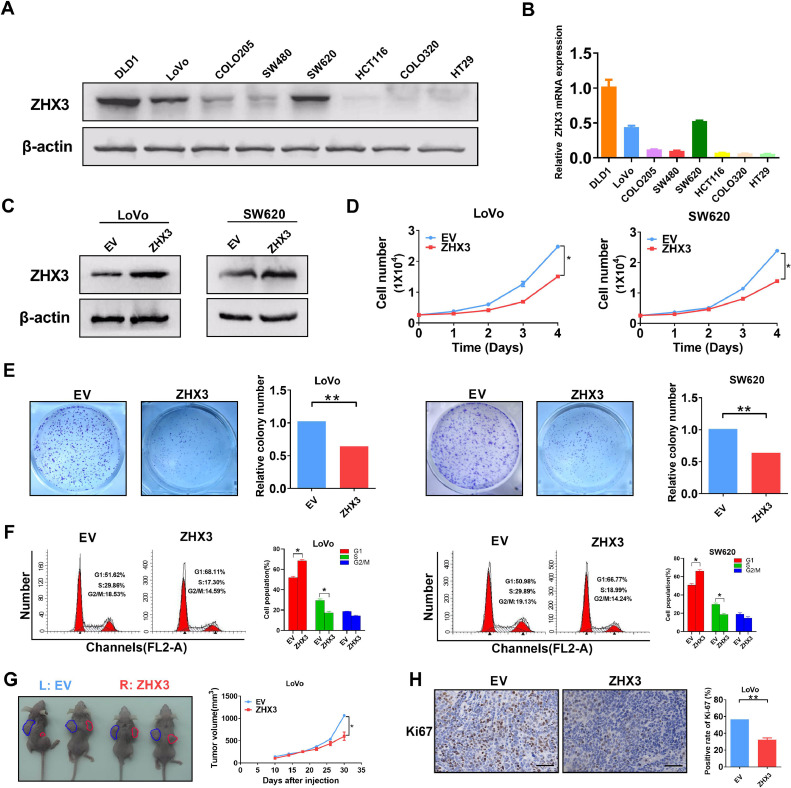

Increased expression of ZHX3 inhibits CRC cells proliferation in vitro and in vivo

To study the role of ZHX3 in CRC cells, we select LoVo and SW620 CRC cells with moderate ZHX3 expression to establish overexpression of ZHX3 expression cell models (Fig. 4A and B). As shown in Fig. 4C, western blot assay confirmed CRC cells models with ZHX3 overexpression were successfully constructed. Since previous studies have confirmed that ZHX3 expression was closely related to tumor size, tumor depth of invasion and TNM stage, we first examined whether ZHX3 had an effect on CRC cell proliferation. As expected, CRC cells with ZHX3 overexpression resulted in a significant decrease in cell proliferation in cell counting assay (Fig. 4D). Moreover, the colony forming assay showed that increased ZHX3 expression significantly inhibited cell colony formation (Fig. 4E). The results of the cell cycle assay demonstrated that the overexpression of ZHX3 led to cell cycle arrest in both the LoVo and SW620 cell lines. Specifically, there was a significant increase in the proportion of cells in the G1 phase, while the proportions of cells in the S phase and G2/M phase decreased (Fig. 4F). Apoptosis experiments showed a significant increase in the number of apoptotic cells after ZHX3 overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 2). To investigate the impact of ZHX3 overexpression or knockdown on the invasion of cells, transwell experiments were conducted. However, the results revealed no significant alteration in the number of migrated cells, suggesting that ZHX3 may not influence the invasion ability of these two cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 3). Consistent with in vitro experiments, ZHX3 overexpression significantly inhibited xenografted tumor growth in nude mice (Fig. 4G). In addition, immunohistochemical staining of Ki-67, a marker of proliferation, was performed to evaluate the role of ZHX3 on tumor proliferation. As is shown in Fig. 4H, the positive rate of Ki67 was significantly decreased in ZHX3 high expressing group. In conclusion, our results showed that high expression of ZHX3 inhibited CRC proliferation both in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 4.

Overexpressing ZHX3 inhibits CRC cell growth both in vitro and in vivo. (A-B) The protein and mRNA expression levels of ZHX3 in different CRC cell lines. (C) Expression of ZHX3 in LoVo and SW620 cells transfected with the indicated expression vectors. (D) Cell counting assay of CRC cells with ZHX3 overexpression. (E) Colony formation assay of CRC cells with ZHX3 overexpression. (F) Cell cycle assay of CRC cells with ZHX3 overexpression. (G) Comparison of tumor volume curves and (H) Ki-67 positive cells in tumor tissues of subcutaneous xenograft tumor models formed by CRC cells stably transfected with forced expression vectors (n = 4). Scale bar, 50 μm. ZHX3, expression vector encoding ZHX3; EV, empty vector. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Decreased expression of ZHX3 promotes CRC cells proliferation both in vitro and in vivo

To further clarify the role of ZHX3 in CRC cell proliferation, we performed in vivo and in vitro experiments. As seen in Fig. 5A, the protein expression level of ZHX3 was decreased significantly in ZHX3 knockdown cells. However, interference with ZHX3 using small RNAs in LoVo and SW620 cell lines did not have any impact on the expression of other ZHX families, including ZHX1 and ZHX2 (Supplementary Fig. 1).Correspondingly, cell proliferation was significantly increased after knockdown of ZHX3 compared to the control group (Fig. 5B). Moreover, the results of colony forming assay indicated that the group with low expression of ZHX3 increased the number of colony forming compared to that of control (Fig. 5C). Moreover, the results of the cell cycle assay showed that knockdown of ZHX3 led to a decrease in the proportion of cells in the G1 phase, but increased the proportions in the S phase and G2/M phase(Fig. 5D). In addition, nude mouse xenograft experiments exhibited that stable ZHX3 knockdown significantly promoted tumor cell growth (Fig. 5E). Our results showed that there was a significant increase in Ki67 expression in the tumor tissue of the decreased ZHX3 expression group (Fig. 5F). In summary, our results suggested that decreased ZHX3 promoted CRC cells proliferation both in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Knockdown of ZHX3 promotes CRC cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo. (A) The protein levels of ZHX3 in LoVo and SW620 cells transfected with the indicated siRNA of ZHX3. (B) Cell counting assay of CRC cells with ZHX3 knockdown. (C) Colony formation assay of CRC cells with ZHX3 knockdown.(D) Cell cycle assay of CRC cells with ZHX3 knockdown. (E) Comparison of tumor volume curves and (F) Ki-67 positive cells in tumor tissues of subcutaneous xenograft tumor models formed by CRC cells transfected with shRNA of ZHX3 (n = 4). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Discussion

Accumulating studies suggest that ZHX3, the member of ZHX family, is involved in a variety of biological activities and cellular functions. Tomoka et al. found that ZHX3 can act as crucial transcription repressor to prevent cellular senescence in cultured fibroblasts [28]. Another study showed that ZHX3 could be a potential ectoderm-biased biomarker in pluripotent stem cells by mRNA and miRNA microarrays analysis [33]. In addition, ZHX3 plays an important role in the regulation of osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells [26]. Other studies have also found that ZHX3 regulates glucose production in liver and primary hepatocytes [34]. Furthermore, ZHX3 has been found in the development of non-neoplastic disease such as nephrotic syndrome [27]. Recently, it has been shown that ZHX3 is of vital role in carcinogenesis and tumor progression of some cancers. For instance, ZHX3 is considered as oncogene which promotes cancer progression in urothelial carcinoma [31] or is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer [19] and renal cell carcinoma [29]. On the contrary, several studies have revealed that ZHX3 might act as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer [32] and in the hepatocellular carcinoma [35]. CRC, as a very common and different tumor type, however, much less is known about the potential role of ZHX3 in its development and progression.

Therefore, the current study was carried out to explore the relationship between ZHX3 expression level and clinical characteristics, disease-free survival and overall survival in patients diagnosed with CRC. Our results indicated that ZHX3 expression level was significantly decreased compared with that of paired adjacent nontumor tissues. Further analysis revealed that ZHX3 expression was positively correlated with tumor size, depth of invasion and TNM stage. These results suggest that ZHX3 may inhibit CRC progression. Next, the relationship between ZHX3 level and disease-free and overall survival was investigated. The current study found that low ZHX3 expression was related to worse disease-free and overall survival. Univariate and multivariate analysis revealed that ZHX3 may be an independent predictor of disease-free and overall survival of patients with CRC. Moreover, further in vivo and in vitro experiments verified low ZHX3 expression remarkably promoted CRC cell proliferation whereas up-regulation of ZHX3 produced the opposite results. These results indicated that ZHX3 might be an effective biomarker for prognosis and a novel therapeutic target for CRC.

It has been reported that ZHX3 may act as an oncogene or tumor-suppressor gene in different types of tumors. However, the molecular mechanism is rarely reported. We found that low expression of ZHX3 was related to the tumor size, the depth of invasion and TNM stage, whereas no significant correlation was made with distance and lymph node metastasis. Our results showed that ZHX3 inhibited CRC progression by affecting cell proliferation not migration or invasion. Deng et al. reported that ZHX3 promotes migration and invasion of urothelial carcinoma [31]. This may reflect that different physiological roles for ZHX3 in different tumor types and different tumor microenvironments. Thus, the molecular mechanism underlying ZHX3 function in CRC is necessary to be further investigated. Our research has some limitations, despite its novelty and significance. First, it is a single-center study, with a relatively small sample size. It is necessary to conduct multicenter randomized controlled trials in future follow-up studies. Second, the molecular mechanism underlying the role of ZHX3 has not yet been fully elucidated. Currently, there is limited research available regarding the mechanism of ZHX3′s impact on tumors. Deng et al. conducted a study revealing that ZHX3 stimulates the invasion and metastasis of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder through the RGS2-RhoA pathway [31]. In our study, the molecular mechanisms involved in the process need to be characterized in the future. Nonetheless, this study has some strengths including detailed patient information, accurate follow-up data.

To conclude, ZHX3 expression was found to be down-regulated in human CRC and to be linked with tumor cell growth and proliferation. Our findings also shown for the first time that ZHX3 was related with disease-free and overall survival in CRC patients. Furthermore, ZHX3 inhibited CRC cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo, according to our findings. These findings suggested that ZHX3 could be a potential predictor of tumor recurrence and prognosis in CRC patients.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhai Cai: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Songsheng Wang: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis. Huabin Zhou: Methodology, Resources, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation. Ding Cao: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Gang Wang from the Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University for his technical support in animal experiments.

Funding statement

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101829.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spadaccini M., Iannone A., Maselli R., Badalamenti M., Desai M., Chandrasekar V.T., Patel H.K., Fugazza A., Pellegatta G., Galtieri P.A., Lollo G., Carrara S., Anderloni A., Rex D.K., Savevski V., Wallace M.B., Bhandari P., Roesch T., Gralnek I.M., Sharma P., Hassan C., Repici A. Computer-aided detection versus advanced imaging for detection of colorectal neoplasia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021;6:793–802. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapelle N., Martel M., Toes-Zoutendijk E., Barkun A.N., Bardou M. Recent advances in clinical practice: colorectal cancer chemoprevention in the average-risk population. Gut. 2020;69:2244–2255. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montazeri Z., Li X., Nyiraneza C., Ma X., Timofeeva M., Svinti V., Meng X., He Y., Bo Y., Morgan S., Castellvi-Bel S., Ruiz-Ponte C., Fernandez-Rozadilla C., Carracedo A., Castells A., Bishop T., Buchanan D., Jenkins M.A., Keku T.O., Lindblom A., van Duijnhoven F.J.B., Wu A., Farrington S.M., Dunlop M.G., Campbell H., Theodoratou E., Zheng W., Little J. Systematic meta-analyses, field synopsis and global assessment of the evidence of genetic association studies in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2020;69:1460–1471. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao W., Chen H.D., Yu Y.W., Li N., Chen W.Q. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: a secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin. Med. J. 2021;134:783–791. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001474. (Engl.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li N., Lu B., Luo C., Cai J., Lu M., Zhang Y., Chen H., Dai M. Incidence, mortality, survival, risk factor and screening of colorectal cancer: a comparison among China, Europe, and Northern America. Cancer Lett. 2021;522:255–268. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biller L.H., Schrag D. Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: a review. JAMA. 2021;325:669–685. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y., Chen Z., Li J. The current status of treatment for colorectal cancer in China: a systematic review. Medicine. 2017;96:e8242. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008242. (Baltimore) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuipers E.J., Grady W.M., Lieberman D., Seufferlein T., Sung J.J., Boelens P.G., van de Velde C.J., Watanabe T. Colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2015;1:15065. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nussbaum N., Altomare I. The neoadjuvant treatment of rectal cancer: a review. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2015;17:434. doi: 10.1007/s11912-014-0434-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobie S.A., Warren J.L., Matthews B., Schwartz D., Baldwin L.M., Billingsley K. Survival benefits and trends in use of adjuvant therapy among elderly stage II and III rectal cancer patients in the general population. Cancer. 2008;112:789–799. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosset J.F., Collette L., Calais G., Mineur L., Maingon P., Radosevic-Jelic L., Daban A., Bardet E., Beny A., Ollier J.C., Trial E.R.G. Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:1114–1123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciolina M., Caruso D., De Santis D., Zerunian M., Rengo M., Alfieri N., Musio D., De Felice F., Ciardi A., Tombolini V., Laghi A. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in locally advanced rectal cancer: role of perfusion parameters in the assessment of response to treatment. Radiol. Med. 2019;124:331–338. doi: 10.1007/s11547-018-0978-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weitz J., Koch M., Debus J., Hohler T., Galle P.R., Buchler M.W. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:153–165. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17706-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfeiffer P., Kohne C.H., Qvortrup C. The changing face of treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2019;19:61–70. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2019.1543593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchetti C., De Felice F., Romito A., Iacobelli V., Sassu C.M., Corrado G., Ricci C., Scambia G., Fagotti A. Chemotherapy resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer: mechanisms and emerging treatments. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021;77:144–166. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo H., Shen K., Li B., Li R., Wang Z., Xie Z. Clinical significance and diagnostic value of serum NSE, CEA, CA19-9, CA125 and CA242 levels in colorectal cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2020;20:742–750. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.11633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yiu A.J., Yiu C.Y. Biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:1093–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.You Y., Bai F., Li H., Ma Y., Yao L., Hu J., Tian Y. Prognostic value and therapeutic implications of ZHX family member expression in human gastric cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2020;12:3376–3388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y., Ma D., Ji C. Zinc fingers and homeoboxes family in human diseases. Cancer Gene Ther. 2015;22:223–226. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2015.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barthelemy I., Carramolino L., Gutierrez J., Barbero J.L., Marquez G., Zaballos A. ZHX-1: a novel mouse homeodomain protein containing two zinc-fingers and five homeodomains. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;224:870–876. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirano S., Yamada K., Kawata H., Shou Z., Mizutani T., Yazawa T., Kajitani T., Sekiguchi T., Yoshino M., Shigematsu Y., Mayumi M., Miyamoto K. Rat zinc-fingers and homeoboxes 1 (ZHX1), a nuclear factor-YA-interacting nuclear protein, forms a homodimer. Gene. 2002;290:107–114. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00553-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawata H., Yamada K., Shou Z., Mizutani T., Yazawa T., Yoshino M., Sekiguchi T., Kajitani T., Miyamoto K. Zinc-fingers and homeoboxes (ZHX) 2, a novel member of the ZHX family, functions as a transcriptional repressor. Biochem. J. 2003;373:747–757. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamada K., Kawata H., Shou Z., Hirano S., Mizutani T., Yazawa T., Sekiguchi T., Yoshino M., Kajitani T., Miyamoto K. Analysis of zinc-fingers and homeoboxes (ZHX)-1-interacting proteins: molecular cloning and characterization of a member of the ZHX family, ZHX3. Biochem. J. 2003;373:167–178. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawata H., Yamada K., Shou Z., Mizutani T., Miyamoto K. The mouse zinc-fingers and homeoboxes (ZHX) family; ZHX2 forms a heterodimer with ZHX3. Gene. 2003;323:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suehiro F., Nishimura M., Kawamoto T., Kanawa M., Yoshizawa Y., Murata H., Kato Y. Impact of zinc fingers and homeoboxes 3 on the regulation of mesenchymal stem cell osteogenic differentiation. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1539–1547. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu G., Clement L.C., Kanwar Y.S., Avila-Casado C., Chugh S.S. ZHX proteins regulate podocyte gene expression during the development of nephrotic syndrome. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:39681–39692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606664200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Igata T., Tanaka H., Etoh K., Hong S., Tani N., Koga T., Nakao M. Loss of the transcription repressor ZHX3 induces senescence-associated gene expression and mitochondrial-nucleolar activation. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwon R.J., Kim Y.H., Jeong D.C., Han M.E., Kim J.Y., Liu L., Jung J.S., Oh S.O. Expression and prognostic significance of zinc fingers and homeoboxes family members in renal cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.You Y., Hu F., Hu S. Attenuated ZHX3 expression is predictive of poor outcome for liver cancer: indication for personalized therapy. Oncol. Lett. 2022;24:224. doi: 10.3892/ol.2022.13345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng M., Wei W., Duan J., Chen R., Wang N., He L., Peng Y., Ma X., Wu Z., Liu J., Li Z., Zhang Z., Jiang L., Zhou F., Xie D. ZHX3 promotes the progression of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder via repressing of RGS2 and is a novel substrate of TRIM21. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:1758–1771. doi: 10.1111/cas.14810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.You Y., Ma Y., Wang Q., Ye Z., Deng Y., Bai F. Attenuated ZHX3 expression serves as a potential biomarker that predicts poor clinical outcomes in breast cancer patients. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019;11:1199–1210. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S184340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mawaribuchi S., Aiki Y., Ikeda N., Ito Y. mRNA and miRNA expression profiles in an ectoderm-biased substate of human pluripotent stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:11910. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48447-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L., Liu Q., Kitamoto T., Hou J., Qin J., Accili D. Identification of insulin-responsive transcription factors that regulate glucose production by hepatocytes. Diabetes. 2019;68:1156–1167. doi: 10.2337/db18-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamada K., Ogata-Kawata H., Matsuura K., Kagawa N., Takagi K., Asano K., Haneishi A., Miyamoto K. ZHX2 and ZHX3 repress cancer markers in normal hepatocytes. Front. Biosci. 2009;14:3724–3732. doi: 10.2741/3483. (Landmark Ed) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.