Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication (LNF) is the most common standard technique worldwidely for Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Another type of fundoplication, laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication (LTF), intends to reduce incidence of postoperative complications. A systematic review and meta-analysis are required on short- and long-term outcomes based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) between LNF and LTF.

Methods

We searched databases including PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, and Web of Knowledge for RCTs comparing LNF and LTF. Outcomes included postoperative reflux recurrence, postoperative heartburn, dysphagia and postoperative chest pain, inability to belch, gas bloating, satisfaction with intervention, postoperative esophagitis, postoperative DeMeester scores, operating time (min), in-hospital complications, postoperative use of proton pump inhibitors, reoperation rate, postoperative lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) pressure (mmHg). We assessed data using risk ratios and weighted mean differences in meta-analyses.

Results

Eight eligible RCTs comparing LNF (n = 605) and LTF (n = 607) were identified. There were no significant differences between the LNF and LTF in terms of postoperative reflux recurrence, postoperative heartburn, postoperative chest pain, satisfaction with intervention, reoperation rate in short and long term, in-hospital complications, esophagitis in short term, and gas bloating, postoperative DeMeester scores, postoperative use of proton pump inhibitors, reoperation rate in long term. LTF had lower LOS pressure (mmHg), fewer postoperative dysphagia and inability to belch in short and long term and gas bloating in short term compared to LNF.

Conclusion

LTF were equally effective at controlling reflux symptoms and improving the quality of life, but with lower rate of complications compared to LNF. We concluded that LTF surgical treatment was superior for over 16 years old patients with typical symptoms of GERD and without upper abdominal surgical history upon high-level evidence of evidence-based medicine.

Keywords: gastro-esophageal reflux disease, laparoscopic, fundoplication, randomized controlled trials, meta-analysis

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common digestive system disease, which causes reflux from stomach contents. GERD has typical symptoms and these symptoms are divided into esophageal or extraesophageal syndromes by The Montreal Definition and Classification of GERD, 1 such as retrosternal burning, regurgitation, and reflux cough syndrome, reflux asthma syndrome etc. A large increase has been witnessed from 1990 to current years both in the global incidence and the global prevalence of all ages.2-4 GERD is a worldwide disease with different prevalence in different region. 5 The highest was in North America with prevalence estimation from 18.1% to27.8%; the following area was in South America with 23.0%; the lowest was in East Asia with 2.5%–7.8%. 6 Compared to medical treatment, surgical treatment offers a choice of a treatment for GERD(7-9). In terms of surgery, the short-term morbidity rate and hospital stay length declines using laparoscopic fundoplication.10-12 Laparoscopic Nissen (360°) fundoplication (LNF) is the most common standard technique worldwide for GERD. 7 There is another anti-reflux procedure, namely, the partial fundoplication. The most common partial fundoplication technique is the laparoscopic Toupet (270°) fundoplication (LTF) with the purpose to lower incidence of postoperative dysphagia, bloating, flatulence, and reoperation rate.13,14 Despite the available evidence shows LTF is a safe and effective alternative anti-reflux procedure, high-quality evidence is needed to support LTF as the priority. 12

In the past decades, several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing between LNF and LTF were published,15-24 and controversy over the optimal surgical method is still ongoing. Short-term and long-term complications are found after fundoplication. Symptoms occur after fundoplication, including heartburn, dysphagia, chest pain, inability to belch, gas bloating, and diarrhea. The short-term postoperative complications may be caused by surgically induced edema and inflammation, 25 and the long-term postoperative complications occurrence comes from structural changes caused by surgery. Although complications are generally self-limiting, which is very common, some cases with severe complications are unable to maintain hydration and nutrition with a liquid diet.26,27 The patients who suffer severely from complications would undergo extra treatments in short-term period after surgery. Several meta-analyses10,13,28-31 have been conducted comparing long-term outcomes between LNF and LTF based on RCTs until 2021. They only included outcomes with a follow-up time greater than 12 months but without the short-term outcomes. However, these short-term outcomes would result in additional health care resource expenditures, such as balloon or probe to dilate the esophagus and if various non-surgical treatments cannot effectively relieve the symptoms, surgical treatment is needed to lift the obstruction. Therefore, it is necessary to systematically review and meta-analysis both short- and long-term potential benefits or the potential side effects of all RCTs comparing LNF with LTF for GERD to develop high-level evidence of evidence-based medicine of which surgical treatment is superior.

Methods

Our meta-analysis was carried out and the results were described as the PRISMA statement.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We selected the studies published till 21 Nov, 2021, by searching PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, and Web of Knowledge. We used the following combined MeSH and Entry terms: “Gastroesophageal Reflux” and “Fundoplication” and “randomized controlled trial”. The complete search used for PubMed was: (((“Gastroesophageal Reflux”[Mesh]) OR ((((((((((((((((((Gastric Acid Reflux[Title/Abstract]) OR (Acid Reflux, Gastric[Title/Abstract])) OR (Reflux, Gastric Acid[Title/Abstract])) OR (Gastric Acid Reflux Disease[Title/Abstract])) OR (Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease[Title/Abstract])) OR (Gastro Esophageal Reflux Disease[Title/Abstract])) OR (Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Diseases[Title/Abstract])) OR (Reflux Disease, Gastro-Esophageal[Title/Abstract])) OR (Gastro-oesophageal Reflux[Title/Abstract])) OR (Gastro oesophageal Reflux[Title/Abstract])) OR (Reflux, Gastro-oesophageal[Title/Abstract])) OR (Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease[Title/Abstract])) OR (GERD[Title/Abstract])) OR (Reflux, Gastroesophageal[Title/Abstract])) OR (Esophageal Reflux[Title/Abstract])) OR (Gastro-Esophageal Reflux[Title/Abstract])) OR (Gastro Esophageal Reflux[Title/Abstract])) OR (Reflux, Gastro-Esophageal[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((“Fundoplication”[Mesh]) OR (((((Nissen Operation[Title/Abstract]) OR (Operation, Nissen[Title/Abstract])) OR (Nissen[Title/Abstract])) OR (Toupet[Title/Abstract])) OR (Antireflux[Title/Abstract])))) AND (randomized controlled trial[Publication Type] OR randomized[Title/Abstract] OR placebo[Title/Abstract]). We applied the language limitations to English.

Inclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (i) Randomized controlled trial comparison between LNF and LTF. (ii) Study population - over 16 years old patient with typical symptoms of GERD, dominated by heartburn and acid regurgitation. (iii) Patients with 24-hour pathological pH surveillance or endoscopy-tested esophagitis. (iv) Patients diagnosed with GERD. (v) Raw data can be drawn from the study to calculate the results.

Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria were: (i) Patients who had previous gastric or antireflux surgery or other major upper abdominal surgical history. (ii) Pregnancy. (iii) The Toupet fundoplication is a non-270° posterior partial fundoplication.

Outcomes of Interest and Definitions

We compared the LNF and LTF treatment strategy for GERD. The outcomes of the assessment were shown below: the short- and long-term outcomes of postoperative reflux recurrence (means no relief of reflux symptoms after surgery), postoperative heartburn (defined as any burning sensation behind the sternum and/or the sub-xiphoid region with or without a relation to food intake and/or posture), 32 dysphagia, postoperative chest pain, inability to belch, gas bloating, satisfaction with intervention, esophagitis, DeMeester scores, in-hospital complications, reoperation rate and lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) pressure (mmHg). Among parameters mentioned above, the primary outcome parameters were specified as postoperative reflux recurrence, postoperative heartburn, postoperative dysphagia, postoperative chest pain, postoperative inability to belch, postoperative gas bloating, satisfaction with intervention. Postoperative esophagitis, postoperative DeMeester scores, operating time (min), in-hospital complications, postoperative use of proton pump inhibitors, reoperation rate, postoperative LOS pressure, were regarded as secondary outcome parameters. The short term implied a postoperative period with no more than 6 months postoperatively, while the long term meant at least 1 year.

Data Extraction

Two independent investigators (Gen Li, Ning Jiang) browsed study titles and abstracts, and studies that met the inclusion criteria were retrieved for full-text assessment. The final included studies were selected, and disagreements were resolved by an additional third investigator (Chuanliang Peng). The following data was extracted by the same two investigators separately. For all studies that met the inclusion criteria, the following data were extracted by both investigators separately: Year of publication, country in which the study was conducted, demographic baseline characteristic, study design, surgical technique, study period, inclusion and exclusion criteria, follow-up period, number of participants, outcomes analysis. Disagreements among investigators are resolved through discussion and consensus. In case of missing data, we contacted the authors of the original study to provide relevant data information. The published RCTs results for the same group of patients at different stages were collected and synthesized in our study.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Two investigators (Gen Li, Ning Jiang) completed risk of bias assessment of all studies independently by using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias' tool.33,34 ‘Low risk of bias', ‘high risk of bias', or ‘unclear risk of bias' are assigned for each ‘Risk of bias’ domain using the specific questions detailed below.

1. Random sequence generation;

2. Allocation concealment;

3. Blinding of participants and personnel;

4. Blinding of outcome assessment;

5. Incomplete outcome data;

6. Selective outcome reporting;

7. Other bias.

We also use the funnel plots to evaluate the publication bias for each outcome included in the trial.

Statistical Analysis

Data extracted from inclusion studies were integrated with Review Manager 5.4 provided by the Cochrane Collaboration. Outcomes reported by two or more studies were pooled in meta-analyses. Dichotomous and continuous outcomes were presented as risk ratios (RRs) and weighted mean differences (MD) respectively. We pooled the data of dichotomous and continuous outcomes using the Mantel–Haenszel and the inverse variance method. The fixed-effects model was used if heterogeneity was absent (χ2 test, P > .1 and I2 < 30%); otherwise, the random-effects model was used. We also did I2 testing to assess the magnitude of the heterogeneity among studies, and the values higher than 30% indicated moderate-to-high heterogeneity. If excessive heterogeneity was present, the data were first rechecked. When unable to explain the causes of heterogeneity, we used subgroup or sensitivity analyses to explore its causes.

Results

Description of Studies

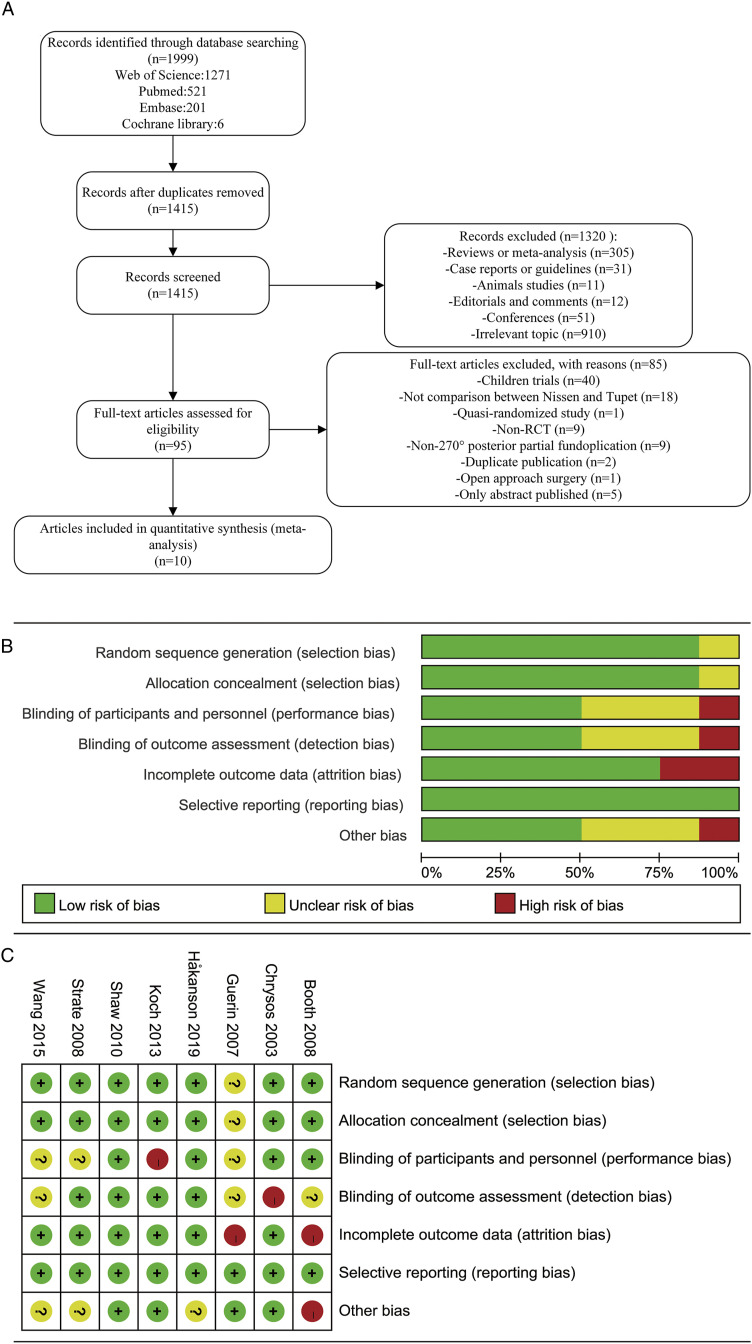

We identified 1415 potentially relevant publications, of which 815-24 (three literature were published based on one RCT study21-23) were included in our analysis (Figure 1) including 1212 participants. We excluded one study 35 because of quasi-randomized controlled trails. Included trials were published between 2003 and 2019. There were 605 participants in LNF and 607 participants in LTF antireflux Operations, where the LTF we included were 270° posterior partial fundoplication. Not all studies had provided data on results that were required. The publication flow is shown in Figure 1. In terms of qualitative outcome parameters, endpoints were assessed by telephone or letter questionnaires to investigate the prevalence of the same defined symptoms. Quantitative outcome parameters, namely the uniform standard objective data, were measured through the patient’s post-operative follow-up. The studies included to conduct meta-analyses all used the same assessment.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram (a) and risk of bias graph (b) and risk of bias summary (c).

Quality Assessment

In two trials (Strate 2008,21-23 Hakanson 2019 18 ), the significant differences of demographic baseline characteristics and preoperative complications in two groups were not reported. Studies included the length of the fundoplication differed from 1 to 4 cm, and the length of the fundoplication was similar in both arms. But one study 20 took a 1 cm wrap in LNF and a 2 cm wrap in LTF. In terms of follow-up time, short-term was defined as less than 12 months, and long-term was defined as more than or equal to 12 months. Both short- and long-term outcomes are included in our study. Characteristics of included studies are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of included randomized controlled trial studies.

| Reference | Country | N (LNF/LTF) | Age (years) (LNF/LTF) | DSGV (LNF/LTF) | Bougies (Fr) (LNF/LTF) | Wrap Length (cm) (LNF/LTF) | Short-Term Outcomes | Long-Term Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Booth 2008 | England | 59/58 | 45.3 (21-86)/44.2 (19-69) | Yes/Yes | 56/56 | 2/2 | 6 months | 12 months |

| Chrysos 2003 | Greece | 14/19 | 61.7±8.7/59.2±11.5 | No/No | No/No | 3-4/3-4 | 3 months | 12 months |

| Guerin 2007 | Belgium | 64/57 | NR | Yes/Yes | 34/34 | 3/NR | Immediate | 12 months |

| Håkanson 2019 | Sweden | 227/228 | 50.2±11.7/47.9±11.7 | Yes/Yes | No/No | 2/NR | 6 weeks | 12 months |

| Koch 2013 | Austria | 54/57 | 50.32(20-76)/51.87(25-81) | Yes/Yes | 58-60/NR | 2/NR | NR | 12 months |

| Shaw 2010 | South Africa | 47/48 | 45.2(28-72)/45.6(25-67) | Yes/Yes | 52/52 | 1/2 | NR | 60 months |

| Strate 2008 | Germany | 100/100 | 56(20-80) | Yes/Yes | 36/NR | 2/NR | 4 months | 24 months |

| Wang 2015 | China | 40/40 | 57±13.2/57±10.8 | Yes/Yes | 32/32 | 2/2 | 6 weeks | 24 months |

DSGV division of short gastric vessels. NR no report.

Methodological Quality of Included Studies

The methodological quality of the included studies was based on the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool. Primary limitations resulted from lack of explanation for double-blinding processes,16,19 and lack of explanation of how many follow-up patients were lost in each group and its reason.15,17 In Booth 2008, 15 more preoperative symptom of dysphagia were found in the LNF group compared with the LTF group. Review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item are presented as percentages among all included studies in (Figure 1). Funnel plots illustrates no significant publication bias in Supplemental File 1-19.

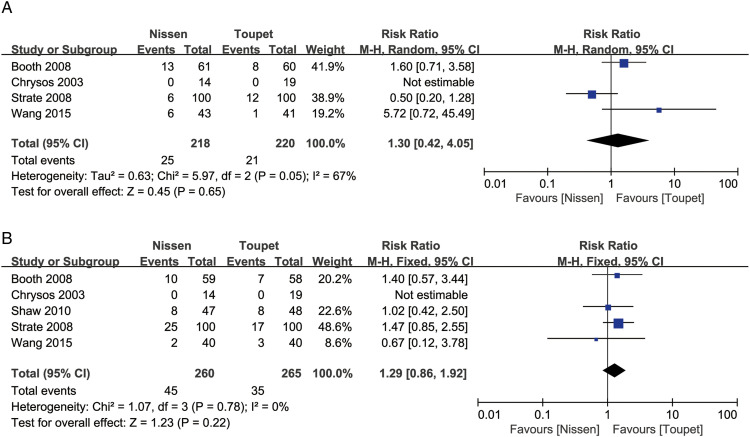

Postoperative Reflux Recurrence

Four studies assessed the short-term outcomes of postoperative reflux recurrence, and the meta-analysis of the postoperative reflux recurrence revealed excessive heterogeneity. Therefore, the random effects model was used for pooling data. There was no difference in this parameter between the two arms. (RR = 1.30, 95% CI, [.42, 4.05], P = .65). After removal of one study [Strate 2008], heterogeneity was significantly reduced and the result did not change. (RR = 2.11, 95% CI, [.74, 6.08], (P = .16); Chi2, (P = .25); I2 = 24%. Five studies analyzed the long-term outcomes of postoperative reflux recurrence, and the meta-analysis showed no significant difference in this outcome between the two arms (RR = 1.29, 95% CI, [.86, 1.92], P = .22) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of short-term (a) and long-term (b) outcomes postoperative reflux recurrence.

Postoperative Heartburn

Three studies assessed the short-term outcomes of postoperative heartburn. The meta-analysis of the postoperative heartburn, the meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference of both two arms (RR = 1.24, 95% CI, [.73, 2.10], P = .42). Four studies assessed the long-term outcomes of postoperative heartburn, and the meta-analysis revealed no significant difference in this outcome between the two arms (RR = .75, 95% CI, [.44, 1.27], P = .28) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of short-term (a) and long-term (b) postoperative heartburn.

Postoperative Dysphagia

Five studies assessed the short-term outcomes of postoperative dysphagia. The meta-analysis of the postoperative dysphagia revealed excessive heterogeneity. Therefore, the random effects model was used for pooling data. There was no difference in this parameter between the two arms (RR = 1.60, 95% CI, [.68, 3.74], Chi2, P = .65; I2 = 86%). By exploring the possible causes of heterogeneity, we consider that the duration of short follow-up of the study 17 was immediate, which could have affected the heterogeneity. After removing one study, heterogeneity was significantly reduced and the result favored LTF (RR = 2.26, 95% CI, [1.56, 3.27], P < .0001). Six studies assessed the long-term outcomes of postoperative dysphagia, and the meta-analysis revealed favored LTF (RR = 2.28, 95% CI, [1.43, 3.63], P = .0005) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of short-term (a) and long-term (b) postoperative dysphagia.

Postoperative Chest Pain

Three studies assessed the short-term outcomes of postoperative chest pain. The meta-analysis of the postoperative chest pain, the meta-analysis revealed no significant difference in this outcome between the two arms (RR = 1.18, 95% CI, [.68, 2.06], P = .55). Three studies assessed the long-term outcomes of postoperative chest pain. The meta-analysis of the postoperative chest pain, the meta-analysis of the postoperative chest pain revealed excessive heterogeneity. Therefore, the random effects model was used for pooling data. There was no difference in this parameter between the two arms (RR = 1.30, 95% CI, [.10, 16.51], P = .84) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of short-term (a) and long-term (b) postoperative chest pain.

Postoperative Inability to Belch

Three studies assessed the short-term outcomes of postoperative inability to belch. The meta-analysis of the postoperative inability to belch revealed excessive heterogeneity. Therefore, the random effects model was used for pooling data. There was no difference in this parameter between the two arms (RR = 1.42, 95% CI, [.26, 7.64] P = .68; Chi2, P = .65; I2 = 86%). In the same reason, we removed one study Guerin 2007. 17 Heterogeneity was significantly reduced and the result favored LTF. (RR = 3.30, 95% CI, [1.26, 8.61], (P = .01). Three studies assessed the long-term outcomes of postoperative Inability to belch, and the meta-analysis revealed favored LTF (RR = 2.04, 95% CI, [1.19, 3.49], P = .009) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis of short-term (a) and long-term (b) Inability to belch.

Postoperative Gas Bloating

Four studies assessed the short-term outcomes of postoperative gas bloating. The meta-analysis of the postoperative gas bloating revealed excessive heterogeneity. Therefore, the random effects model was used for pooling data. There was no difference in this parameter between the two arms (RR = 1.40, 95% CI, [.55, 3.57]; P = .48; Chi2, P = .01; I2 = 73%). In the same reason, we removed one study Guerin 2007. 17 Heterogeneity was significantly reduced and the result favored LTF (RR = 2.14, 95% CI, [1.30, 3.53], P = .003. Three studies assessed the long-term outcomes of postoperative gas bloating, and the meta-analysis showed no significant difference between the two arms (RR = 1.50, 95% CI, [.86, 2.64], P = .16) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Meta-analysis of short-term (a) and long-term (b) Gas bloating.

Satisfaction with Intervention

Two studies assessed the short-term outcomes of satisfaction with intervention. The meta-analysis of the satisfaction with intervention revealed no significant difference in this outcome between the two arms (RR = .97, 95% CI, [.88, 1.06]; P = .47); Six studies assessed the long-term outcomes of satisfaction with intervention, and the meta-analysis revealed no significant difference between the two arms (RR = 1.00, 95% CI, [.94, 1.06], P = .95) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Meta-analysis of short-term (a) and long-term (b) Satisfaction with intervention.

Postoperative Esophagitis

Two studies assessed the short-term outcomes of postoperative esophagitis. The meta-analysis of the postoperative esophagitis revealed excessive heterogeneity. Therefore, the random effects model was used for pooling data. The meta-analysis of the esophagitis revealed no significant difference in this outcome between the two arms (RR = 1.30, 95% CI, [.61, 2.80]; P = .50; Chi2, P = .50; I2 = 45%) (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Meta-analysis of postoperative esophagitis (a), postoperative DeMeester scores (b), operating time (min) (c), in-hospital complications (d), postoperative use of proton pump inhibitors (e), reoperation rate (f), postoperative LOS pressure (mmHg) (g).

Postoperative DeMeester Scores

Four studies assessed the long-term outcomes of DeMeester scores. The meta-analysis of the postoperative DeMeester scores revealed excessive heterogeneity. Therefore, the random effects model was used for pooling data. The meta-analysis of the DeMeester scores revealed no significant difference in this outcome between the two arms (MD = −.26, 95% CI, [-2.59, 2.06]; P = .82; Chi2, P = .18; I2 = 39%) (Figure 9).

Operating Time (min)

Four studies assessed the operating time (min), where four studies with applied division of the short gastric vessels and one study was with non-division of the short gastric vessels. The meta-analysis of the operating time (min) revealed excessive heterogeneity. Therefore, the random effects model was used for pooling data. Operating time was shorter in patients undergoing LNF surgical (MD = −11.16, 95% CI, [-17.50, −4.82]; P = .0006; Tau2 P = .02, I2 = 64%). We removed one study Chrysos 2003. 16 Heterogeneity was significantly reduced and the result did not change (MD = -7.42, 95% CI, [-11.22, −3.62], P = .0001) (Figure 9).

In-Hospital Complications

Five studies assessed the in-hospital complications (fundal wrap perforation, atelectasis, pleural effusion, haemorrhage, pneumothorax pneumothorax, intestinal perforation, parenchymal-splenic injuries and nervous vomiting). The meta-analysis of the in-hospital complications revealed no significant difference between the two arms (RR = 1.03, 95% CI, [.58, 1.82], P = .93) (Figure 9).

Postoperative Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors

Two studies assessed the postoperative use of proton pump inhibitors. The meta-analysis of using proton pump inhibitors postoperatively revealed no significant difference between the two arms (RR = 1.11, 95% CI, [.75, 1.64], P = .61) (Figure 9).

Reoperation Rate

Five studies assessed the reoperation rate. The meta-analysis of the reoperation rate revealed no significant difference between the two arms (RR = 1.94, 95% CI, [.82, 4.57] (P = .13) (Figure 9).

Postoperative LOS Pressure (mmHg)

Three studies assessed the long-term outcomes of postoperative LOS pressure (mmHg). We removed two studies Booth 2008 15 and Strate 2008, 21 where the raw data standard deviation cannot draw from the study to calculate the results. Postoperative LOS pressure (mmHg) was higher in patients LNF surgical (MD = 2.65, 95% CI, [1.64, 3.65], P < .00001) (Figure 9).

Discussion

In our meta-analysis, we included 8 RCTs that reported short- and long-term outcomes of postoperative of 1212 patients after a standardized surgical technique total (360°) LNF or a 270° circumferences LTF. Our findings indicated that, compared with LNF, LTF were equally effective at controlling reflux symptoms and improving the quality of life, without increasing the in-hospital complications and reoperation rate. Our analysis showed that LTF tended to have less LOS pressure (mmHg) of postoperative and more operating time (min). The rates of short- and long-term postoperative reflux recurrence, postoperative heartburn, postoperative chest pain, satisfaction with intervention and short-term postoperative esophagitis and long-term gas bloating, postoperative DeMeester scores, postoperative use of proton pump inhibitors were similar after LTF and LNF. Furthermore, LTF had lower risk for early term postoperative dysphagia, postoperative inability to belch, postoperative gas bloating complications and long-term complications postoperative dysphagia, postoperative inability to belch. These data supported LTF as a therapeutic strategy that had lower incidence complications antireflux surgery for treatment of GERD.

Since the literature on LNF in 1991, the most commonly surgery procedure for GERD is LNF, also known as the 360° stomach wrap. 36 The challenge with anti-reflux surgery is improving subjective symptoms while minimizing subjective side effects. LTF, also known as 270° stomach wrap, can minimize LNF complications. The fundoplication is the gold standard for surgical, which increases the ability of the esophagogastric junction to prevent reflux control. 37 Fundoplication creates a barrier against the reflux of all gastric substances (acidic and non-acidic), to relieve reflux-related proton-pump inhibitor refractory heartburn. 38 There are views proposed to adapt antireflux procedures to the results of pre-operative esophageal manometry and pH tests, but a growing body of evidence suggests that such a strategy is unnecessary.15,21,39-42

In the last two decades, several high-quality random sequence generation and allocation concealment RCTs comparing LNF with LTF (270° stomach wrap) have been published. To prevent increasing heterogeneity among tests and reducing the reliability and accuracy of the meta-analysis results, we excluded the non-270° posterior partial Toupet fundoplication. Therefore, we have good comparability of baseline information on the LNF and the LTF. From 2010 to 2021, five meta-analyses13,28-31 comparing the LNF and the LTF were published. However, for all the meta-analyses there were no report of the short-term outcomes of postoperative. To evaluate short- and long-term outcomes and explore symptom regression over time after LNF or LTF, it is therefore important to reevaluate and synthesize data from existing trials.

The short-term outcomes of one RCT Guerin 2007 17 was the immediate postoperative result, which caused the excessive heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of the postoperative dysphagia, inability to belch, and gas bloating. The reason for that is anesthesia and pneumoperitoneum of laparoscopic would result in impaired gastrointestinal motility. This is different from tissue edema due to surgery, which is the cause of excessive heterogeneity. When the RCT causes excessive heterogeneity at the short-term meta-analysis, we would remove it. Different from the others, one of the RCT was no division of short gastric vessels. However, in our review, Chrysos 2003 16 was included because, except of operative time, other aspects were identical. Some studies 43 have shown no difference in outcomes when comparing conventional fundoplication with no division of the short gastric vessels. Our study found that the postoperative LOS pressure (mmHg) was lower in the patients who undergoing LTF, which was appeared to be sufficient to prevent reflux of stomach contents. But our study demonstrated therapeutic effect of LNF and LTF were equivalent. Although our study showed that LTF increases the procedure time and LNF was simpler and easier to perform compared to LTF, based on the fewer complications of LTF, we suggest that a gradual transition from LNF to LTF should be arranged. By analyzing the follow-up results within five years, our research showed that LTF not only had equivalent reflux control compared to LNF, but also had fewer complications in the early postoperative period. Although results of follow-up beyond 5 years were rarely reported, a recent study where there were beyond 5 years of follow-up also supported our view. 44 The limitations of our meta-analysis were: the length of short-term and long-term follow-up was not uniform in original studies included in the meta-analysis; We excluded data that did not meet the uniform criteria resulting in less data available for meta-analysis and thus there were fewer objective outcome parameters in our research; Due to the limitations of the follow-up time in the included studies, no meta-analysis was conducted for results beyond 5 years of follow-up.

In terms of the current findings on surgical efficacy and complications, for over 16 years old patients with typical symptoms of GERD and without upper abdominal surgical history, the LTF has better data to support itself, but more researches are necessary to determine the superior treatment based on the short and long term for GERD.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Laparoscopic Nissen Versus Toupet Fundoplication for Short- and Long-Term Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review by Gen Li, Ning Jiang, Nuerboli Chendaer, Yingtao Hao, Weiquan Zhang, Chuanliang Peng in Surgical Innovation

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Chuanliang Peng, Ning Jiang, Gen Li. Acquisition of data: Gen Li, Ning Jiang, Nuerboli Chendaer. Analysis and interpretation: Gen Li, Ning Jiang, Nuerboli Chendaer. Study supervision: Yingtao Hao, Weiquan Zhang, Chuanliang Peng.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Chuanliang Peng https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2275-4789

References

- 1.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R, Global Consensus Group . The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(8):1900-1920; quiz 43. PubMed PMID: 16928254. Epub 2006/08/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dirac MA, Safiri S, Tsoi D. The global, regional, and national burden of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(6):561-581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho KY. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia: a condition in evolution. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(5):716-722. PubMed PMID: 18410606. Epub 2008/04/16. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Serag HB. Time trends of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(1):17-26. PubMed PMID: 17142109. Epub 2006/12/05. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katzka DA, Kahrilas PJ. Advances in the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 371, 2020;371:m3786. PubMed PMID: 33229333. Epub 2020/11/25. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63(6):871-880. PubMed PMID: 23853213. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC4046948. Epub 2013/07/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elakkary E, Duffy A, Roberts K, Bell R. Recent advances in the surgical treatment of achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(5):603-609. PubMed PMID: 18364581. Epub 2008/03/28. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gyawali CP, Fass R. Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):302-318. PubMed PMID: 28827081. Epub 2017/08/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hart E, Dunn TE, Feuerstein S, Jacobs DM. Proton Pump Inhibitors and Risk of Acute and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Pharmacotherapy. 2019;39(4):443-453. PubMed PMID: 30779194. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC6453745. Epub 2019/02/20. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catarci M, Gentileschi P, Papi C, Carrara A, Marrese R, Gaspari AL, et al. Evidence-based appraisal of antireflux fundoplication. Ann Surg. 2004;239(3):325-337. PubMed PMID: 15075649. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC1356230. Epub 2004/04/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du X, Hu Z, Yan C, Zhang C, Wang Z, Wu J. A meta-analysis of long follow-up outcomes of laparoscopic Nissen (total) versus Toupet (270°) fundoplication for gastro-esophageal reflux disease based on randomized controlled trials in adults. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16(1):88. PubMed PMID: 27484006. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC4969978. Epub 2016/08/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stefanidis D, Hope WW, Kohn GP, Reardon PR, Richardson WS, Fanelli RD, et al. Guidelines for surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(11):2647-2669. PubMed PMID: 20725747. Epub 2010/08/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian ZC, Wang B, Shan CX, Zhang W, Jiang D, Qiu M. A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials to Compare Long-Term Outcomes of Nissen and Toupet Fundoplication for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0127627. PubMed PMID: 26121646. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC4484805. Epub 2015/06/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varin O, Velstra B, De Sutter S, Ceelen W. Total vs partial fundoplication in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2009;144(3):273-278. PubMed PMID: 19289668. Epub 2009/03/18. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Booth MI, Stratford J, Jones L, Dehn TCB. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic total (Nissen) versus posterior partial (Toupet) fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease based on preoperative oesophageal manometry. Br J Surg. 2008;95(1):57-63. PubMed PMID: 18076018. Epub 2007/12/14. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chrysos E, Tsiaoussis J, Zoras OJ, Athanasakis E, Mantides A, Katsamouris A, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for gastroesophageal reflux disease patients with impaired esophageal peristalsis: total or partial fundoplication? J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197(1):8-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerin E, Betroune K, Closset J, Mehdi A, Lefebvre JC, Houben JJ, et al. Nissen versus Toupet fundoplication: results of a randomized and multicenter trial. Surg Endosc. 200721(11):1985-1990. PubMed PMID: 17704884. Epub 2007/08/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hakanson BS, Lundell L, Bylund A, Thorell A. Comparison of Laparoscopic 270° Posterior Partial Fundoplication vs Total Fundoplication for the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(6):479-486. PubMed PMID: 30840057. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC6583844. Epub 2019/03/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koch OO, Kaindlstorfer A, Antoniou SA, Luketina RR, Emmanuel K, Pointner R. Comparison of results from a randomized trial 1 year after laparoscopic Nissen and Toupet fundoplications. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(7):2383-2390. PubMed PMID: 23361260. Epub 2013/01/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw JM, Bornman PC, Callanan MD, Beckingham IJ, Metz DC. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic Nissen and laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a prospective, randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(4):924-932. PubMed PMID: 19789920. Epub 2009/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strate U, EmmermAnn A, Fibbe C, Strate U, EmmermAnn A. Laparoscopic fundoplication: Nissen versus Toupet two-year outcome of a prospective randomized study of 200 patients regarding preoperative esophageal motility. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(1):21-30. PubMed PMID: 18027055. Epub 2007/11/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fibbe C, Layer P, Keller J, Strate U, EmmermAnn A, Zornig C. Esophageal motility in reflux disease before and after fundoplication: a prospective, randomized, clinical, and manometric study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(1):5-14. PubMed PMID: 11438489. Epub 2001/07/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zornig C, Strate U, Fibbe C, Strate U, EmmermAnn A. Nissen vs Toupet laparoscopic fundoplication. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(5):758-766. PubMed PMID: 11997817. Epub 2002/05/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang B, Zhang W, Liu S, Du Z, Shan C, Qiu M. A Chinese randomized prospective trial of floppy Nissen and Toupet fundoplication for gastroesophageal disease. Int J Surg. 2015;23(Pt):35-40. PubMed PMID: 26360740. Epub 2015/09/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yadlapati R, Hungness ES, Pandolfino JE. Complications of Antireflux Surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(8):1137-1147. PubMed PMID: 29899438. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC6394217. Epub 2018/06/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malhi-Chowla N, Gorecki P, Bammer T, Achem SR, Hinder RA, Devault KR. Dilation after fundoplication: timing, frequency, indications, and outcome. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55(2):219-223. PubMed PMID: 11818926. Epub 2002/01/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaker A, Stoikes N, Drapekin J, Kushnir V, Brunt LM, Gyawali CP. Multiple rapid swallow responses during esophageal high-resolution manometry reflect esophageal body peristaltic reserve. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(11):1706-1712. PubMed PMID: 24019081. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC4091619. Epub 2013/09/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du X, Hu Z, Yan C, Zhang C, Wang Z, Wu J. A meta-analysis of long follow-up outcomes of laparoscopic Nissen (total) versus Toupet (270°) fundoplication for gastro-esophageal reflux disease based on randomized controlled trials in adults. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16(1):88. PubMed PMID: 27484006. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC4969978. Epub 2016/08/04. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan G, Yang Z, Wang Z. Meta-analysis of laparoscopic total (Nissen) versus posterior (Toupet) fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease based on randomized clinical trials. ANZ J Surg. 2011;81(4):246-252. PubMed PMID: 21418467. Epub 2011/03/23. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shan CX, Zhang W, Zheng XM, Jiang DZ, Liu S, Qiu M. Evidence-based appraisal in laparoscopic Nissen and Toupet fundoplications for gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(24):3063-3071. PubMed PMID: 20572311. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC2890948. Epub 2010/06/24. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Broeders JA, Mauritz FA, Ahmed Ali U, Draaisma WA, Ruurda JP, Gooszen HG. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic Nissen (posterior total) versus Toupet (posterior partial) fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Br J Surg. 2010;97(9):1318-1330. PubMed PMID: 20641062. Epub 2010/07/20. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rijnhart-De Jong HG, Draaisma WA, Smout AJPM, Broeders IAMJ, Gooszen HG. The Visick score: a good measure for the overall effect of antireflux surgery? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(7):787-793. PubMed PMID: 18584516. Epub 2008/06/28. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:Ed000142. PubMed PMID: 31643080. Epub 2019/10/24. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011;343:d5928. PubMed PMID: 22008217. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3196245 www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare support from the Cochrane Collaboration for the development and evaluation of the tool described; they have no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. Epub 2011/10/20. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qin M, Ding G, Yang H. A clinical comparison of laparoscopic Nissen and Toupet fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23(7):601-604. PubMed PMID: 23614820. Epub 2013/04/26. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geagea T. Laparoscopic Nissen's fundoplication: preliminary report on ten cases. Surg Endosc. 1991;5(4):170-173. PubMed PMID: 1839573. Epub 1991/01/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garg SK, Gurusamy KS. Laparoscopic fundoplication surgery versus medical management for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(11):Cd003243. PubMed PMID: 26544951. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC8278567. Epub 2015/11/07. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, Lee R, Smith BR, Mashimo H, et al. Randomized Trial of Medical versus Surgical Treatment for Refractory Heartburn. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1513-1523. PubMed PMID: 31618539. Epub 2019/10/17. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biertho L, Sebajang H, Anvari M. Effects of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication on esophageal motility: long-term results. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(4):619-623. PubMed PMID: 16508818. Epub 2006/03/02. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Booth M, Stratford J, Dehn TCB. Preoperative esophageal body motility does not influence the outcome of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. 2002;15(1):57-60. PubMed PMID: 12060044. Epub 2002/06/13. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beckingham IJ, Cariem AK, Bornman PC, Callanan MD, Louw JA. Oesophageal dysmotility is not associated with poor outcome after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Br J Surg. 1998;85(9):1290-1293. PubMed PMID: 9752880. Epub 1998/09/30. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mughal MM, Bancewicz J, Marples M. Oesophageal manometry and pH recording does not predict the bad results of Nissen fundoplication. Br J Surg. 1990;77(1):43-45. PubMed PMID: 2302512. Epub 1990/01/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kinsey-Trotman SP, Devitt PG, Bright T, Thompson SK, Jamieson GG, Watson DI. Randomized Trial of Division Versus Nondivision of Short Gastric Vessels During Nissen Fundoplication: 20-Year Outcomes. Ann Surg. 2018;268(2):228-232. PubMed PMID: 29303805. Epub 2018/01/06. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Analatos A, Håkanson BS, Ansorge C, Lindblad M, Lundell L, Thorell A. Clinical Outcomes of a Laparoscopic Total vs a 270° Posterior Partial Fundoplication in Chronic Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2022. Apr 20. PubMed PMID: 35442430. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC9021984 grants (to institution) from Ethicon Endo-Surgery, is a member of an advisory board for Novo Nordisk and Ethicon Endo-Surgery, and has received speaker honoraria from Kabi Fresenius and Ethicon Endo-Surgery. No other disclosures were reported. Epub 2022/04/21. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Laparoscopic Nissen Versus Toupet Fundoplication for Short- and Long-Term Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review by Gen Li, Ning Jiang, Nuerboli Chendaer, Yingtao Hao, Weiquan Zhang, Chuanliang Peng in Surgical Innovation