Abstract

Legal problems encompass issues requiring resolution through the justice system. This social risk factor creates barriers in accessing services and increases risk of poor health outcomes. A systematic review of the peer-reviewed English-language health literature following the PRISMA guidelines sought to answer the question, how has the concept of patients’ “legal problems” been operationalized in healthcare settings? Eligible articles reported the measurement or screening of individuals for legal problems in a United States healthcare or clinical setting. We abstracted the prevalence of legal problems, characteristics of the sampled population, and which concepts were included. 58 studies reported a total of 82 different measurements of legal problems. 56.8% of measures reflected a single concept (e.g., incarcerated only). The rest of the measures reflected two or more concepts within a single reported measure (e.g., incarcerations and arrests). Among all measures, the concept of incarceration or being imprisoned appeared the most frequently (57%). The mean of the reported legal problems was 26%. The literature indicates that legal concepts, however operationalized, are very common among patients. The variation in measurement definitions and approaches indicates the potential difficulties for organizations seeking to address these challenges.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40352-023-00246-5.

Keywords: Social determinants of health, Screening, Measurement

Introduction

Patients with past and current legal problems face significant barriers in accessing key services and are at risk of future poor health outcomes and high cost services. In the US, more than 3.8 million adults are on probation or parole (Kaeble, 2020), which are associated with increased emergency department utilization and hospitalizations (Hawks et al. 2020). Additionally, the US has the highest incarceration rates in the world (The Sentencing Project, 2022) and patients with a history of incarceration are at increased risk for chronic conditions and face barriers to housing and employment (Massoglia & Pridemore, 2015). As part of the broader trend in social risk factor measurement, healthcare organizations are able to screen for patients’ legal problems through the wide variety of questionnaires developed by healthcare organizations, government agencies, practice collaboratives, and electronic health record vendors (Social Interventions Research Evaluation Network. Social Needs Screening Tool Comparison Table, 2019).

However, substantial variation appears to exist in the how healthcare organizations have operationalized patients’ legal problems. For example, screening questionnaires and surveys use differing words, including time in jail, parole, arrests, justice-involvement, and incarceration (Moen et al. 2020; Saloner et al. 2016; Social Interventions Research Evaluation Network. Social Needs Screening Tool Comparison Table, 2019), to capture patients’ legal problems. Likewise, the interventions available to healthcare organizations to support patients, such as medical-legal partnerships, may address differing legal problems such as issues arising from criminal records, immigration status, and broader issues such as housing and benefits (Sandel et al. 2010). Also, ICD10 Z codes allow for problems related to arrests and prosecution in addition to incarceration history (World Health Organization. ICD-10 Version:, 2019. Chapter XXI Factors influencing health status & contact with health services 2019).

The objective of this study is to answer the question, how has the concept of patients’ “legal problems” been operationalized in healthcare settings? Given that healthcare organizations are increasingly attentive to identifying patients’ social risk factors, we specifically focus on the operationalization of “legal problems” in the screening and measurement contexts. Clarity on the difference between definitions of patients’ legal problems in current measurements will allow organizations to link services more effectively to patients’ needs and enable comparisons across populations.

Theoretical framing

The objectives and orientation of this review are grounded in the epidemiological concept of screening and the population health management concept of risk stratification. Screening for social risk factors, such as patients with legal problems, is simply a systematic process of case finding (Andermann, 2018). Risk stratification is the process of subdividing a large population into smaller segments at increased risk for negative health outcomes (Girwar et al. 2021). The identification of key subsets within the population allows for better matching of needed resources to specific patient needs through referrals or direct service provision (Vuik et al. 2016). In population health management, social risk factor screening may be used to inform, or be the basis of, risk stratification and intervention delivery (Steenkamer et al. 2017).

To be effective, however, case finding via screening and stratification strategies must accurately reflect the social factor of concern. Incorrect identification of a patient’s specific risk could result in services that are poorly matched or altogether neglect patient needs. The former is a potential waste of resources, and the latter does not improve patient health. For example, common screening questionnaires’ language reflects concepts such as time in jail, parole, arrests, justice-involvement, and incarceration (Moen et al. 2020; Saloner et al. 2016; Social Interventions Research Evaluation Network. Social Needs Screening Tool Comparison Table, 2019). While each of these different terms are potentially reflective of the broader concept of legal problems (Currie, 2009), these terms have specific definitions that reflect different types of engagement with the criminal justice system, differ in terms of temporality, and may have different risks for health (Bryson et al. 2021). For example, individuals with a history of arrests may face stigma and discrimination while seeking care from the health care system (Redmond et al. 2020; Smith et al. 2022). During incarceration, risks include infectious disease, violence, and substance misuse (American Academy of Family Physicians, 2021). Individuals recently released from incarceration can face difficulties in employment or housing, which affects access to the resources and environments to remain healthy (Lares & Montgomery, 2020).

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the peer-reviewed English-language health literature following the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al. 2021). We included the following concepts under the broader term legal problems: probation, arrest, parole, incarceration, criminal record/history, corrections, justice-involved and juvenile justice. Known, relevant articles collected by the authors were analyzed to select relevant keywords and subject headings. We excluded legal problems of a civil nature (i.e. divorce, custody, lawsuits, etc.).

Information sources & search strategy

We identified peer-reviewed articles through database searches. First, the teams’ health science librarian (RH) queried Medline (via OVID), PsycINFO (via EBSCO), CINAHL (via EBSCO), the Criminal Justice Index (via ProQuest), and Google Scholar on March 9th, 2022. The first 100 records were downloaded from Google Scholar. The final search terms incorporated subject headings and keywords associated with legal problems, social determinants of health, screening and instruments, and healthcare settings.

Articles were eligible for inclusion if they reported the measurement or screening of individual patients for legal problems in a US healthcare or clinical setting. We excluded all nonpatient populations and settings, such as assessments of currently incarcerated populations, studies of clinician perceptions, studies within community-based organizations, or national population-based surveys. We excluded all articles that were case studies, commentaries, or editorials, and those not in English. The full search strategies for all information sources are provided in Additional file 1.

Selection and screening

First, two authors (JV and HH) independently screened the titles for potential inclusion. The goal at this step was to exclude the obviously ineligible studies. As such, we erred on the side of inclusion. The second round was screening based off the abstract information only. From this set, we reviewed the full text to determine final inclusion status. The interrater agreement on this final step was 0.65. All differences were resolved with a joint reading and discussion until consensus was reached.

Data elements and abstraction

One author (HH) independently abstracted data, which was verified by a second author (JV). The data abstracted included identifying information from each of the included studies: author(s), year, title, and journal. In addition, the study design, study dates, healthcare setting, method of patient data collection (e.g., survey, natural language processing (NLP), review of data charted by providers), and study sample demographics were abstracted.

Next, we extracted each article’s reported measures of legal problems. One article may have had more than one measure. For each of the reported measurements, we used a series of binary indicators to indicate which concepts were included in the measure: incarceration, jail, probation, parole, arrests, awaiting trial, contact with criminal justice system, convictions, crimes, immigration status, or juvenile detention. If provided, we also abstracted the reported prevalence of legal problems. We noted if any measurement of the reliability and validity was reported.

Bias assessment

To understand the potential bias in the reported measures of legal problems, we described each study sample broadly as general patient populations, or targeted to those with specific risk behaviors or characteristics (i.e. at-risk).

Analyses

We describe the characteristics of the included studies and provided measures using frequencies and percentages. Additionally, we used means to summarize the reported percentages of legal problem by including concepts stratified by general or at-risk populations. We compared means using t-tests. Due to small samples, we limited the summarization by means to those categories with at least 10 observations.

Results

Study selection

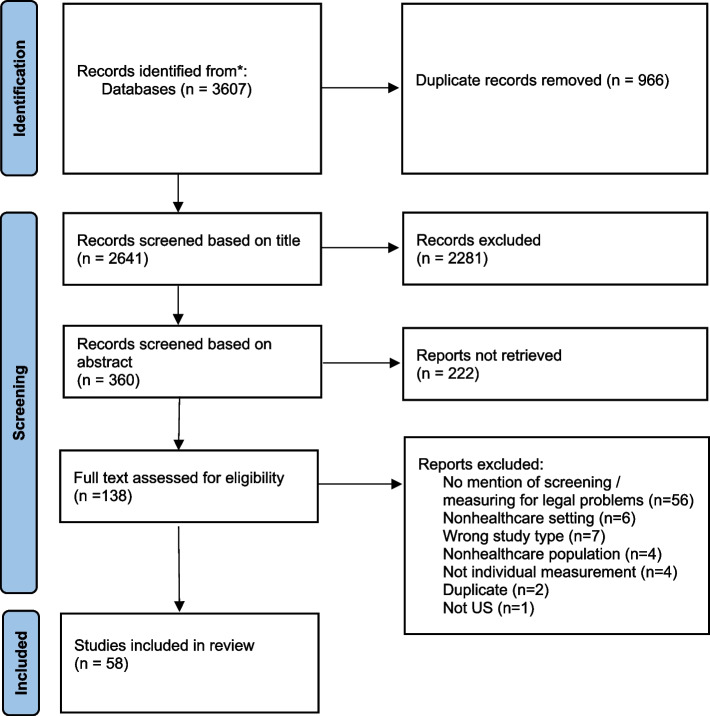

Our initial search strategy yielded 2,641 records for screening after duplicates were removed (Fig. 1). After excluding records based on title (n = 2,281) and abstract (n = 222), we were left with 138 records for full-text assessment. The most common reason for excluding the study at this stage was no mention of screening or measurement of legal problems (n = 58). The other reasons for exclusion (e.g. non-healthcare settings or non-healthcare population) were much less frequent. The resultant strategy and selection process resulted in 58 studies that reported a total of 82 different measurements of legal problems (Additional file 2).

Fig. 1.

Search strategy to identify healthcare's operationalization of legal problems

Study characteristics

The included studies utilized patient samples from a variety of healthcare delivery settings (Table 1). Notably, a fifth of the studies were focused on behavioral health settings. Other settings included specialty providers such as STD (Weisbord et al. 2003; Widman et al. 2014) or methadone clinics (Magura et al. 1998). The patients represented in the included studies were largely adults (75.4%) and inclusive of both genders (92.6%). However, several of the studies, notably those among veterans, were highly skewed towards male samples (Blosnich et al. 2020; Elbogen et al. 2018; Holliday et al. 2021; Schultz et al. 2015; Szymkowiak et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2019). Overall, the included studies focused more on patient groups with some known risk factors associated with legal problems (61.4%), such as behavioral health comorbidities (Anderson et al. 2015; Buzi et al. 2016; Carlsen-Landy et al. 2020; Evens & Vander, 1997; Giggie et al. 2007; Harry & Steadman, 1988; Klassen & O’Connor, 1988; Lorine et al. 2015; Pasic et al. 2005; Phillips et al. 2002; Prins et al. 2015; Rich & Sullivan, 2001; Schauss et al. 2020; Theriot & Segal, 2005), history of risky sexual behaviors (Aronson et al. 2016; Kadivar et al. 2006; Sheu et al. 2002; Tolou-Shams et al. 2007; Widman et al. 2014), or at risk of substance misuse (Claus & Kindleberger, 2002; Liebschutz et al. 2010; Magura et al. 1998; Mark et al. 2020; Pittsenbarger et al. 2017; Schultz et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2010).

Table 1.

Measures of legal problems in healthcare and study characteristics

| Characteristic | Percent |

|---|---|

| Settinga | |

| Behavioral health | 21.1 |

| FQHC | 5.3 |

| Health system (inpatient & outpatient) | 29.8 |

| Hospital or emergency department | 19.3 |

| Primary care clinic | 14.0 |

| Other clinic type | 10.5 |

| Populationa | |

| General | 38.6 |

| At risk | 61.4 |

| Age groups includeda | |

| Adults | 75.4 |

| Pediatric | 14.0 |

| Both | 10.5 |

| Genders includeda | |

| Both | 92.6 |

| Female only | 4.4 |

| Male only | 2.9 |

| Measurement methodb | |

| Survey | 63.4 |

| Linked databases | 14.6 |

| Chart review | 9.8 |

| EHR structured data | 8.5 |

| NLP | 3.7 |

| Number of concepts appearing within measuresb | |

| One | 56.8 |

| Two | 21.0 |

| Three | 13.6 |

| Four | 2.5 |

| Five | 6.2 |

| Concepts appearing within measuresb | |

| Incarceration | 58.5 |

| Arrests | 26.8 |

| Jail | 25.6 |

| General / no description contact with criminal justice system | 13.4 |

| Juvenile detention / correction | 13.4 |

| Convictions | 12.2 |

| Parole | 11.0 |

| Probation | 11.0 |

| Immigration | 6.1 |

| Criminal activity | 1.2 |

aOut of articles (n = 58)

bOut of individual measures (n = 82)

The most common method for obtaining individual’s legal problems (Table 1) was through a survey or questionnaire (63.4%). Most of these instances were homegrown or unique tools and only a few studies reported using previously published multidomain social determinant of health screeners like PRAPARE (Kusnoor et al. 2018) or I-HELLP (Ko et al. 2016; Patel et al. 2018). However, multiple studies made use of the legal module within the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (Claus & Kindleberger, 2002; Erlyana et al. 2019; Schultz et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2010), which is a psychometrically evaluated tool for measuring substance abuse behavior and related risk factors. The next most common approach to measuring legal problems was through the use of linked databases (14.6%), i.e., the combination of data sources created and maintained by disparate entities through patient identifiers (Arthur et al. 2018; Claassen et al. 2007; Evens & Vander, 1997; Finlay et al. 2022; Harry & Steadman, 1988; Klassen & O’Connor, 1988; Mark et al. 2020; Theriot & Segal, 2005). While not a true gold standard, these linked sources represent an independent and objective measurement of patient contact with aspects of the criminal justice system. The remaining approaches to measurement all relied on existing information from medical records. Beyond general “chart review”, several measures used structured data from within the electronic health record (EHR): ICD-10 Z codes (Alemi et al. 2020; Blosnich et al. 2020; Davis et al. 2020), specific service codes (Davis et al. 2020; Szymkowiak et al. 2022), or sources of admissions and discharges (Garrett et al. 2020). Lastly, three studies used NLP techniques to identify legal problems (Boch et al. 2021; Vest et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2019). Notably, Wang and colleagues (Wang et al. 2019) compared their NLP algorithm against an independent reference standard.

Measures of “legal problems” used within individual studies

The included studies used a wide variety of terms to describe the constructs under consideration ranging from variants of global terms like criminal justice involvement, interaction, or status (Alemi et al. 2020; Anderson et al. 2015; Doran et al. 2021; Holliday et al. 2021; Ko et al. 2016; Magura et al. 1998; Ragucci et al. 2001; Schauss et al. 2020; Schultz et al. 2015; Shah et al. 2009; Theriot & Segal, 2005), correctional involvement (Boch et al. 2021; MacKenzie et al. 2021), criminal history (Carlsen-Landy et al. 2020; Claassen et al. 2007; Schultz et al. 2015), and legal problems or needs (Aronson et al. 2016; Blosnich et al. 2020; Davis et al. 2020; Heller et al. 2020; Kulie et al. 2021; Poleshuck et al. 2020; Tolou-Shams et al. 2007) to the more focused such as incarceration (Anderson et al. 2015; Buzi et al. 2016; Doran et al. 2021; Elbogen et al. 2018; Garrett et al. 2020; Gilbert et al. 2013; Howell et al. 2016; Lorine et al. 2015; MacKenzie et al. 2021; Mark et al. 2020; Pasic et al. 2005; Rich & Sullivan, 2001; Shah et al. 2009; Sheu et al. 2002; Szymkowiak et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2010; Widman et al. 2014), arrests (Doran et al. 2021; Erlyana et al. 2019; Harry & Steadman, 1988; Klassen & O’Connor, 1988; Rich & Sullivan, 2001), or immigration status (Gottlieb et al. 2014; Patel et al. 2018; Wyrick et al. 2017). Within this set, some articles provided very detailed definitions of the constructs being measured [e.g. (Gilbert et al. 2013; Schultz et al. 2015; Theriot & Segal, 2005), or provided a clear distinction between lifetime and more recent exposures [e.g. (Howell et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2019)].

Among the 82 different recorded measures (Table 1), just over half (56.8%) reflected a single concept (e.g., incarcerated only). The rest of the measures reflected two (21.0%) or more concepts within a single reported measure (e.g., incarcerations and arrests, or arrests, convictions, parole, probation, and incarceration). Among all measures, the concept of incarceration or being imprisoned appeared the most frequently (58.5%). The measures next most frequently reflected were arrests (26.8%) or time in jail (25.6%).

Synthesis

Overall, the mean of the reported legal problems was 26.0% across all studies. When stratified by study population, the percent of legal problems among studies of general populations was 13.8%. This was statistically lower than the percentage among at risk populations (35.6%). This was the general trend for all the examined concepts. For example, when legal problems included the concept of incarcerations, the percent among at-risk populations was significantly higher (36.1%) than the percent among general populations (16.5%). Within population groups, the mean prevalence varied according to the included concepts. Regardless of measurement approach, those at risk generally had a higher percentage of legal problem than those measured among general populations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean reported percentage of legal problems by concepts included in the definition and measurement methods

| At risk | General | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | |

| Totala | 77 | 35.6 (22.2) | 13.8 (16.1) | 0.0001 |

| Concepts appearing within measuresb | ||||

| Incarceration | 45 | 36.1 (22.2) | 16.5 (17.9) | 0.0022 |

| Arrests | 21 | 41.9 (24.9) | 20.3 (20.3) | 0.0534 |

| Jail | 19 | 24.9 (20.4) | 22.1 (19.7) | 0.7930 |

| General / no description contact with criminal justice system | 9 | 26.6 (31.6) | 2.4 (1.6) | 0.1271 |

| Juvenile detention / correction | 10 | 41.6 (10.7) | 18.7 (21.6) | 0.0874 |

| Convictions | 9 | 40.6 (29.3) | 2.1 (1.0) | 0.0639 |

| Parole / probation | 9 | 34.0 (29.3) | 16.0 (19.7) | 0.3301 |

| Immigration | 5 | 34.0 (29.3) | 16.0 (19.7) | 0.3301 |

| Measurement methodc | ||||

| Survey | 47 | 34.2 (22.5) | 19.0 (16.5) | 0.0131 |

| Linked databases | 12 | 45.3 (25.2) | 2.2 (1.0) | 0.0037 |

| Chart review | 8 | 35.6 (20.8) | –c | – |

| EHR structured data | 7 | 21.3 (0.1) | 2.5 (3.0) | 0.0004 |

| NLP | 3 | – | 15.6 (23.5) | – |

aStudies with no percentages reported omitted (n = 5)

bConcept appeared in definition, but not exclusively. More than one concept may be included

cCombination not present – not reported

Discussion

Legal problems broadly encompass issues requiring resolution through the justice system (Currie, 2009; Nobleman, 2014). Legal problems, in their variety of manifestations, create barriers to health and wellbeing for patients. The existing literature on patients’ legal problems in healthcare settings utilize a variety of measurement methods and measures, including different and sometimes multiple concepts. Overall, the literature indicates that legal concepts, however operationalized, are very common among patient groups with known risk factors and common among general patient populations. The variation identified in measurement definitions, measurement approaches, and included populations indicates health care organizations will face challenges in formulating intervention strategies.

First, we focused on those problems associated with the criminal justice system. Even within this restricted definition of legal problems, we noted substantial variability in the concepts measured in the literature. This in itself is not a negative; different legal problems represent unique encounters with the criminal justice system and may create different risks or require different responses. For example, incarceration in prison is a detention due to a conviction (Gilbert et al. 2013) and that stress leads to negative health effects, which may require attentiveness to conditions such as heart disease or hypertension (Massoglia & Pridemore, 2015). In contrast, an arrest is a less severe degree of contact with the criminal justice system (Asad & Clair, 2018), but one that can create barriers to housing and employment (Ispa-Landa & Loeffler, 2016). However, the challenge with the literature was in frequent lack of specificity and clarity around measurement definitions without such clarity, matching appropriate interventions becomes more difficult.

Second, the validity and reliability of the measurement strategies selected was largely unknown; pragmatic tools or unspecified items or definitions were most common. In this respect, the operationalization of legal problems has the same challenges as other social risk factors, which tend to have poorly evaluated measurement tools (Henrikson et al. 2019). This practice of non-validated or programmatic tools unfortunately contributes to the uncertainty of the measurements. In addition to lack of clarity, some tools included multiple distinct concepts simultaneously. In contrast, those that relied on the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) could be much more specific about, and confident in, the reliability and validity of their measures of legal problems (Claus & Kindleberger, 2002; Erlyana et al. 2019; Schultz et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2010). However, using a validated tool like the ASI may not be practical in practice or in research studies given its length. For those looking to use various screening methods, the study by Wang and colleagues (Wang et al. 2019) was particularly useful as it indicated that measures were generally very specific, but were not as sensitive. Regardless of the survey or NLP algorithm selected, an effective process will require clear definition of the issue being measured so that the correct intervention can be identified and delivered.

As a result of these measurement issues, along with the frequent study of at-risk populations, makes drawing conclusions about the prevalence of legal issues in US healthcare setting challenging. At risk populations had much higher reported percentages of legal problems than general patient populations. Attempts to generalize these percentages to the general patient populations is likely not possible, as legal problems are associated with behavioral health comorbidities (Anderson et al. 2015; Buzi et al. 2016; Carlsen-Landy et al. 2020; Evens & Vander, 1997; Giggie et al. 2007; Harry & Steadman, 1988; Klassen & O’Connor, 1988; Lorine et al. 2015; Pasic et al. 2005; Phillips et al. 2002; Prins et al. 2015; Rich & Sullivan, 2001; Schauss et al. 2020; Theriot & Segal, 2005), history of risky sexual behaviors(Aronson et al. 2016; Kadivar et al. 2006; Sheu et al. 2002; Tolou-Shams et al. 2007; Widman et al. 2014), or at risk of substance misuse (Claus & Kindleberger, 2002; Liebschutz et al. 2010; Magura et al. 1998; Mark et al. 2020; Pittsenbarger et al. 2017; Schultz et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2010). Nevertheless, given the high rates of incarceration and contact with the law enforcement in the US (Asad & Clair, 2018; Kaeble, 2020; The Sentencing Project, 2022), the occurrence of legal problems among more general patient populations should be not negligible. The estimates in the general population samples bear out that legal problems are somewhat common (Additional file 2).

Limitations

The study is limited in that it did not specifically include civil legal problems like unsafe housing, unfair employment, or family law (Currie, 2009; Sandel et al. 2010). However, some articles may have included these issues and if we had included these issues, we would have likely seen even more variation. In addition, we limited our studies to those in healthcare-related settings. Other studies have looked at population level percentages or measurement in community settings, thus they may have had different foci and resulted in different strategies.

Conclusions

Increasingly healthcare organizations are screening patients for various social risk factors to drive referral decisions and support community needs assessments. The operationalization of legal problems in measurement approaches is variable often without strong evidence of construct validity.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

JV conceived and designed the study. RH designed the methods. JV and HH abstracted all information and performed all analyses. All authors drafted and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (1R01HS028636-01) and the National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health (T15LM012502).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Systematic review. Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Joshua Vest is a founder and equity holder in Uppstroms, a technology company.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Joshua R. Vest, Email: joshvest@iu.edu

Heidi Hosler, Email: hbhosler@gmail.com.

References

- Alemi F, Avramovic S, Renshaw KD, Kanchi R, Schwartz M. Relative accuracy of social and medical determinants of Suicide in electronic health records. Health Services Research. 2020;55(Suppl 2):833–840. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Incarceration and Health: A Family Medicine Perspective (2021). https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/incarceration.html. Accessed 19 Aug 2023.

- Anderson A, Esenwein SV, Spaulding A, Druss B. Involvement in the criminal justice system among attendees of an urban mental health center. Health Justice. 2015;3:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s40352-015-0017-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andermann A. Screening for social determinants of health in clinical care: Moving from the margins to the mainstream. Public Health Reviews. 2018;39:19. doi: 10.1186/s40985-018-0094-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson ID, Cleland CM, Perlman DC, Rajan S, Sun W, Ferraris C, et al. MOBILE SCREENING TO IDENTIFY AND FOLLOW-UP WITH HIGH RISK, HIV NEGATIVE YOUTH. J Mob Technol Med. 2016;5:9–18. doi: 10.7309/jmtm.5.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur KC, Lucenko BA, Sharkova IV, Xing J, Mangione-Smith R. Using State Administrative Data to identify Social Complexity Risk factors for children. Annals of Family Medicine. 2018;16:62–69. doi: 10.1370/afm.2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asad AL, Clair M. Racialized legal status as a social determinant of health. Social Science and Medicine. 2018;199:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich JR, Montgomery AE, Dichter ME, Gordon AJ, Kavalieratos D, Taylor L, et al. Social determinants and military veterans’ Suicide ideation and attempt: A Cross-sectional Analysis of Electronic Health Record Data. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2020;35:1759–1767. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05447-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boch S, Sezgin E, Ruch D, Kelleher K, Chisolm D, Lin S. Unjust: The health records of youth with personal/family justice involvement in a large pediatric health system. Health Justice. 2021;9:20. doi: 10.1186/s40352-021-00147-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson WC, Piel J, Thielke S. Associations between parole, probation, arrest, and self-reported Suicide attempts. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57:727–735. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00704-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzi RS, Smith P, Haase S. Risk-related behaviors Associated with HIV among Young Minority men Attending Family Planning Clinics. Int J Mens Health. 2016;15:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen-Landy D, Bolton C, Baronia R, McMahon T, Larumbe E, McGovern TF. A study of criminal history among young adults with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders in psychiatry outpatient. Alcohol Treat Q. 2020;38:346–355. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2019.1700861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claassen CA, Larkin GL, Hodges G, Field C. Criminal correlates of injury-related emergency department recidivism. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2007;32:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2006.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claus RE, Kindleberger LR. Engaging substance abusers after centralized assessment: Predictors of treatment entry and dropout. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34:25–31. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie A. The Legal Problems of Everyday Life: The Nature, Extent and Consequences of Justiciable Problems Experienced by Canadians. Department of Justice Canada; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Davis CI, Montgomery AE, Dichter ME, Taylor LD, Blosnich JR. Social determinants and emergency department utilization: Findings from the Veterans Health Administration. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020;38:1904–1909. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran KM, Johns E, Zuiderveen S, Shinn M, Dinan K, Schretzman M, et al. Development of a homelessness risk screening tool for emergency department patients. Health Services Research. 2021 doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Brancu M, Kimbrel NA, Naylor JC, Swinkels CM, et al. Psychosocial risk factors and other than honorable military discharge: Providing healthcare to previously ineligible veterans. Military Medicine. 2018;183:e532–e538. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usx128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlyana E, Reynolds GL, Fisher DG, Pedersen WC, Van Otterloo L. Arrest and trait aggression correlates of emergency department use. Journal of Correctional Health Care : The Official Journal of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care. 2019;25:253–264. doi: 10.1177/1078345819854373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evens CC, Vander Stoep A. II risk factors for juvenile justice system referral among children in a public mental health system. J Ment Health Adm. 1997;24:443–455. doi: 10.1007/BF02790505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay AK, Palframan KM, Stimmel M, McCarthy JF. Legal system involvement and opioid-related Overdose mortality in U.S. Department of Veterans affairs patients. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2022;62:e29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett N, Bikah Bi Nguema Engoang JA, Rubin S, Vickery KD, Winkelman TNA. Health system resource use among populations with complex social and behavioral needs in an urban, safety-net health system. Healthc Amst Neth. 2020;8:100448. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2020.100448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giggie MA, Olvera RL, Joshi MN. Screening for risk factors associated with Violence in pediatric patients presenting to a psychiatric emergency department. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2007;13:246–252. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000281485.96698.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Chang M, Shaw SA, Wu E, Roy L. Risk and protective factors for drug use and partner Violence among women in emergency care. J Community Psychol. 2013;41:565–581. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb LM, Hessler D, Long D, Amaya A, Adler N. A randomized trial on screening for social determinants of health: The iScreen study. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1611–e1618. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girwar SM, Jabroer R, Fiocco M, Sutch SP, Numans ME, Bruijnzeels MA. A systematic review of risk stratification tools internationally used in primary care settings. Health Sci Rep. 2021;4:e329. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harry B, Steadman HJ. Arrest rates of patients treated at a community mental health center. Hospital & Community Psychiatry. 1988;39:862–866. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.8.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawks L, Wang EA, Howell B, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Bor D, et al. Health Status and Health Care utilization of US adults under probation: 2015–2018. American Journal of Public Health. 2020;110:1411–1417. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller CG, Parsons AS, Chambers EC, Fiori KP, Rehm CD. Social risks among Primary Care patients in a large Urban Health System. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2020;58:514–525. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrikson NB, Blasi PR, Dorsey CN, Mettert KD, Nguyen MB, Walsh-Bailey C, et al. Psychometric and pragmatic properties of Social Risk Screening tools: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2019;57:S13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday R, Hoffmire CA, Martin WB, Hoff RA, Monteith LL. Associations between justice involvement and PTSD and depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and Suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2021;13:730–739. doi: 10.1037/tra0001038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell B, Long J, Edelman E, McGinnis K, Rimland D, Fiellin D, et al. Incarceration history and uncontrolled blood pressure in a Multi-site Cohort. JGIM J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:1496–1502. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3857-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ispa-Landa S, Loeffler CE. Indefinite punishment and the criminal record: Stigma Reports among Expungement-Seekers in Illinois*. Criminology. 2016;54:387–412. doi: 10.1111/1745-9125.12108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadivar H, Garvie PA, Sinnock C, Heston JD, Flynn PM. Psychosocial profile of HIV-infected adolescents in a Southern US urban cohort. Aids Care. 2006;18:544–549. doi: 10.1080/13548500500228763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeble, D., Probation, & Parole in the United States. (2020). and, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2021.

- Klassen D, O’Connor WA. Crime, inpatient admissions, and Violence among male mental patients. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 1988;11:305–312. doi: 10.1016/0160-2527(88)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko NY, Battaglia TA, Gupta-Lawrence R, Schiller J, Gunn C, Festa K, et al. Burden of socio-legal concerns among vulnerable patients seeking cancer care services at an urban safety-net hospital: A cross-sectional survey. Bmc Health Services Research. 2016;16:196. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1443-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusnoor SV, Koonce TY, Hurley ST, McClellan KM, Blasingame MN, Frakes ET, et al. Collection of social determinants of health in the community clinic setting: A cross-sectional study. Bmc Public Health. 2018;18:550–550. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5453-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulie P, Steinmetz E, Johnson S, McCarthy ML. A health-related social needs referral program for Medicaid beneficiaries treated in an emergency department. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2021;47:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lares LA, Montgomery S. Psychosocial needs of released long-term incarcerated older adults. Crim Justice Rev. 2020;45:358–377. doi: 10.1177/0734016820913101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liebschutz JM, Saitz R, Weiss RD, Averbuch T, Schwartz S, Meltzer EC, et al. Clinical factors associated with prescription Drug Use Disorder in urban primary care patients with chronic pain. The Journal of Pain : Official Journal of the American Pain Society. 2010;11:1047–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorine K, Goenjian H, Kim S, Steinberg AM, Schmidt K, Goenjian AK. Risk factors associated with psychiatric readmission. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2015;203:425–430. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie O, Goldman J, Chin M, Duffy B, Martino S, Ramsey S, et al. Association of Individual and Familial History of Correctional Control With Health Outcomes of Patients in a primary Care Center. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2133384–e2133384. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.33384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Nwakeze PC, Demsky SY. Pre- and in-treatment predictors of retention in Methadone treatment using survival analysis. Addict Abingdon Engl. 1998;93:51–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark K, Pierce E, Joseph D, Crimmins S. Interaction with the justice system and other factors associated with pregnant women’s self-report and continuation of use of marijuana. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2020;206:107723. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoglia M, Pridemore WA. Incarceration and health. Annu Rev Sociol. 2015;41:291–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen M, Storr C, German D, Friedmann E, Johantgen M. A review of tools to Screen for Social Determinants of Health in the United States: A practice brief. Popul Health Manag. 2020;23:422–429. doi: 10.1089/pop.2019.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobleman RL. Addressing Access to Justice as a Social Determinant of Health. Health Law Journal. 2014;21:49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M, Bathory E, Scholnick J, White-Davis T, Choi J, Braganza S. Resident Documentation of Social determinants of Health: Effects of a Teaching Tool in the outpatient setting. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2018;57:451–456. doi: 10.1177/0009922817728697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SD, Burns BJ, Wagner HR, Kramer TL, Robbins JM. Parental incarceration among adolescents receiving mental health services. J Child Fam Stud. 2002;11:385–399. doi: 10.1023/A:1020975106679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pasic J, Russo J, Roy-Byrne P. High utilizers of Psychiatric Emergency services. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D. C.) 2005;56:678–684. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittsenbarger Z, Thurm C, Neuman M, Spencer S, Simon H, Gosdin C, et al. Hospital-Level Factors Associated with Pediatric Emergency Department Return visits. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2017;12:536–543. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poleshuck E, Wittink M, Crean HF, Juskiewicz I, Bell E, Harrington A, et al. A comparative effectiveness trial of two patient-centered interventions for women with Unmet Social needs: Personalized support for Progress and enhanced screening and referral. J Womens Health. 2020;29:242–252. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins SJ, Skeem JL, Mauro C, Link BG. Criminogenic factors, psychotic symptoms, and incident arrests among people with serious mental illnesses under intensive outpatient treatment. Law and Human Behavior. 2015;39:177–188. doi: 10.1037/lhb0000104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragucci MV, Gittler MM, Balfanz-Vertiz K, Hunter A. Societal risk factors associated with spinal cord injury secondary to Gunshot Wound. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2001;82:1720–1723. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.26610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond N, Aminawung JA, Morse DS, Zaller N, Shavit S, Wang EA. Perceived discrimination based on criminal record in Healthcare settings and self-reported health status among formerly incarcerated individuals. Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2020;97:105–111. doi: 10.1007/s11524-019-00382-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich JA, Sullivan LM. Correlates of violent Assault among young male primary care patients. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2001;12:103–112. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloner B, Bandara SN, McGinty EE, Barry CL. Justice-involved adults with Substance Use disorders: Coverage increased but Rates of Treatment did not in 2014. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:1058–1066. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MP, Edmonds-Myles S, Anderson M, Shapiro ME, Chu C. The impact of mass incarceration on outpatients in the Bronx: A card study. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2009;20:1049–1059. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandel M, Hansen M, Kahn R, Lawton E, Paul E, Parker V, et al. Medical-legal partnerships: Transforming primary Care by addressing the Legal needs of vulnerable populations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1697–1705. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauss E, Zettler H, Naik S, Ellmo F, Hawes K, Dixon P, et al. Adolescents in residential treatment: The prevalence of aces, substance use and justice involvement. J Fam Trauma Child Custody Child Dev. 2020;17:249–267. doi: 10.1080/26904586.2020.1781018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz NR, Blonigen D, Finlay A, Timko C. Criminal typology of veterans entering substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;54:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu M, Hogan J, Allsworth J, Stein M, Vlahov D, Schoenbaum EE, et al. Continuity of medical care and risk of incarceration in HIV-positive and high-risk HIV-negative women. J Womens Health. 2002;11:743–750. doi: 10.1089/15409990260363698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social Interventions Research & Evaluation Network. Social Needs Screening Tool Comparison Table. SIREN (2019). https://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/tools-resources/resources/screening-tools-comparison. Accessed 16 Mar 2022.

- Smith ML, Hoven CW, Cheslack-Postava K, Musa GJ, Wicks J, McReynolds L, et al. Arrest history, stigma, and self-esteem: A modified labeling theory approach to understanding how arrests impact lives. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2022;57:1849–1860. doi: 10.1007/s00127-022-02245-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamer BM, Drewes HW, Heijink R, Baan CA, Struijs JN. Defining Population Health Management: A scoping review of the literature. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20:74–85. doi: 10.1089/pop.2015.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymkowiak D, Montgomery AE, Tsai J, O’Toole TP. Frequent Episodic Utilizers of Veterans Health Administration Homeless Programs Use: Background characteristics and Health services Use. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice : Jphmp. 2022;28:E211–E218. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Sentencing Project. Criminal Justice Facts. Criminal Justice Facts (2022). https://www.sentencingproject.org/criminal-justice-facts/. Accessed 3 Jun 2022.

- Theriot MT, Segal SP. Involvement with the Criminal Justice System among New Clients at Outpatient Mental Health Agencies. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D. C.) 2005;56:179–185. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolou-Shams M, Brown LK, Gordon G, Fernandez I. Arrest history as an indicator of adolescent/young adult substance use and HIV risk. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:87–90. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vest J, Grannis SJ, Haut DP, Halverson PK, Menachemi N. Using structured and unstructured data to identify patients’ need for services that address the social determinants of health. Int J Med Inf. 2017;107:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuik SI, Mayer EK, Darzi A. Patient segmentation analysis offers significant benefits for Integrated Care and Support. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:769–775. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang EA, Long JB, McGinnis KA, Wang KH, Wildeman CJ, Kim C, et al. Measuring exposure to incarceration using the Electronic Health Record. Medical Care. 2019;57:S157. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang EA, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, Fiellin DA. Effect of incarceration history on outcomes of primary care office-based buprenorphine/naloxone. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25:670–674. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1306-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisbord JS, Trepka MJ, Zhang G, Smith IP, Brewer T. Prevalence of and risk factors for Hepatitis C virus Infection among STD clinic clientele in Miami, Florida. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2003;79:E1. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.1.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Noar SM, Golin CE, Willoughby JF, Crosby R. Incarceration and unstable housing interact to predict sexual risk behaviours among African American STD clinic patients. International Journal of Std and Aids. 2014;25:348–354. doi: 10.1177/0956462413505999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. ICD-10 Version:2019. Chapter XXI Factors influencing health status and contact with health services (Z00-Z99) (2021). https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en#/XXI. Accessed 21 Jan 2021.

- Wyrick JM, Kalosza BA, Coritsidis GN, Tse R, Agriantonis G. Trauma care in a multiethnic population: Effects of being undocumented. Journal of Surgical Research. 2017;214:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.