ABSTRACT

One of the most commonly encountered scenarios in any healthcare setting is a patient presenting with a headache. Yet, the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of headache disorders can be challenging and burdensome for even specialist doctors in medicine, psychiatry, oto-rhinology, neurology and so on. Apart from saving patient’s and doctor’s time as well as money, this article will buy leading time for better outcome and management of certain difficult headache disorders. The aim of this review is to simplify the approach to headache diagnosis for an early and proper referral. Literature search was done on PubMed and Google Scholar using key words. Only studies which were in English were considered. Sixty-one articles published from 1975 to 2022 were reviewed after screening for inclusion and exclusion criteria. It is very essential that a primary care physician is aware of the classification of headache. Red flag signs of high-risk headaches are essential for proper referral. It is also essential that we rule out secondary headaches as they are more life threatening. Vulnerable populations such as geriatric and paediatric populations require expert attention in case of headache disorders.

Keywords: Cluster, headache, migraine, primary care, tension type, treatment

Introduction

Headache may be described as a disabling and painful characteristic of primary headache disorders that include cluster headache (CH), tension-type headache (TTH), migraine and chronic daily headache syndromes.[1] The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that in any given year, nearly one-half of the adult population in the world will suffer from a headache disorder. This shows it has a tremendous effect on ‘public health’.[2] It is a common universal symptom that has varied and complex causes.[3] The Ad Hoc Committee on Classification of Headache has classified headache into as many as 15 categories.[4] The second edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-2) has classified headache disorders depending on aetiology into primary and secondary headaches. Primary headache disorders are without any underlying aetiology and secondary headache disorders may be due to specific causes [Table 1].[5] Headaches can be seen in people irrespective of their races, socio-economic status and age. However, it is more commonly prevalent in the female sex.[3]

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of secondary headache

| Diagnosis | Symptoms | Signs | Investigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervicogenic headache[7] | Non-throbbing headache, starting in the neck Duration- varied | Precipitated by movement, reduced range of neck movement, neck/shoulder/arm pain- ipsilateral, no side shift | X-ray |

| Giant cell arteritis[7,14] | Age at onset >50 years Onset- abrupt unilateral/bilateral headache, scalp tenderness, visual symptoms- diplopia, blurred vision/loss, limb claudication, constitutional symptoms- fever, malaise, fatigue, weight loss | Tender, thickened, reduced pulsation in superficial temporal artery, scalp tenderness, visual field defect, vascular bruit | ESR >50 mm/h Arterial biopsy- vasculitis characterised by mononuclear cell infiltration, multinucleated giant cells Fundoscopy Optic disc- pale and swollen with haemorrhage |

| Idiopathic intracranial hypertension[14] | Daily, non-pulsating, diffuse headache increased by coughing, straining | Papilloedema, visual field defect, enlarged blind spot, sixth nerve palsy | LP-CSF pressure >200 mm of H2O (non-obese) >250 mm of H2O (obese) MRI, CT |

| Post-traumatic headache[14] | Headache except any typical features within 7 days after head trauma | CT with bone window images X-ray- fracture, ligamentous injury of spine, subluxation Cranial MRI- focal contusion- non-haemorrhagic | |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage[15] | Intense, incapacitating abrupt-onset headache associated with vomiting | Neck rigidity, altered mentation | CT scan- haemorrhage MRI CSF examination if scan is normal Angiography |

| Central venous thrombosis[15] | Headache with no specific features | Seizure, signs of raised intracranial tension, focal neurological signs | MRI along with MRV venous thrombosis |

| Trigeminal neuralgia[16] | Unilateral, onset- abrupt, electric shock-like sensations, duration- seconds to 2 min, along distribution of the fifth cranial nerve (second, third divisions), pain induced by washing, brushing, smoking, talking | Neurological deficit- absent | MRI- vascular/non-vascular Compression of fifth cranial nerve |

| Acute glaucoma | Painful red eye, sudden blindness/blurred vision | Clouding of cornea, conjunctival injection, visual disturbances | Elevated IOP>28 mmHg |

| Acute sinusitis | Frontal headache, pain in ear, face and teeth | Sinus tenderness | Elevated ESR, polymorphonuclear leucocytosis Pus culture- organism isolated X-ray- shadow/fluid level |

CSF=cerebrospinal fluid, CT=computed tomography, ESR=erythrocyte sedimentation rate, IOP=intraocular pressure, MRI=magnetic resonance imaging, LP-CSF=Lumbar puncture-cerebro-spinal fluid, MRV=Magnetic resonance venography

One of the most commonly encountered scenarios in any healthcare setting is a patient presenting with a headache. Yet, the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of headache disorders can be challenging and burdensome for even specialist doctors in medicine, psychiatry, oto-rhinology, neurology and so on. The sole purpose of this review is to simplify the approach to headache diagnosis for an early and proper referral. Apart from saving patient’s and doctor’s time as well as money, this article will buy leading time for better outcome and management of certain difficult headache disorders.

Materials and Methods

Literature search (eligibility criteria, information sources and search): A complete literature search was done to identify population-based research work on different types of headache and their management. PubMed and Google Scholar were used to search the following key words: primary care, migraine, headache, treatment, cluster, tension type. Most articles were published from 1970 to 2022, and only English language was considered. Only online articles were included in the review.

Data extraction (data collection process): The information extracted included the types of headache, their prevalence, their classification, diagnosis and management. Also, information about diagnosis and management of various types of headache in special populations based on age group was also included.

Study selection

All studies published from 1975 to 2022 that were available online were selected. Out of 80 articles screened, 61 were included. Studies which were in language other than English were excluded, and those that did not have access were also excluded. Only those articles in which headache diagnosis was according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders-1 (ICHD-1) or ICHD-2 or ICHD-3 were included. Although ICHD-1 appeared in 1988, we also included studies on headache prevalence before 1988.

Data items

Population: We selected studies that were performed in a sample representative of the whole population. We also included studies on special populations such as geriatric and paediatric age groups. Studies based on specific populations such as clinic population/college students/pregnant women were not included.

Intervention: Studies describing various types of pharmacotherapy for headache, including oral medications as well as parenteral medication of primary headache particularly, were included. Studies exploring neurostimulation methods for treatment of primary headache were included. All articles describing acute as well as prophylactic management of primary headache were included.

Comparison or control: May be or may not be present.

Outcome: Reduction of headache.

Study design: Systematic reviews, meta-analysis, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) as well as other narrative reviews were included. Case series and case reports were not included.

Epidemiology and Classification

Primary chronic daily headache syndrome has been divided into chronic TTH, migraine, new daily persistent headache (NDPH) and hemicranias continua (HC). They comprise almost 98% of all headache disorders.[6] Although secondary headaches are more serious and can end up in life-threatening scenarios, most of the time, he adaches are treatable with lifestyle changes and/or medications.[3]

ICHD third edition (beta version)

Primary headaches

Although primary headache disorders are not life threatening, they are responsible for high disability-adjusted life years (DALY) and morbidity. The true magnitude of public health burden of headache has not been fully acknowledged until now. Headache causes huge loss to society indirectly through loss of work time. Like any other chronic disorder, headaches cause loss of quality of life, disability and morbidity at an individual level.[7] DALY due to primary headaches can be reduced by early identification [Figure 1] and swift evidenced-based management [Table 2].

Figure 1.

Classification of headache (based on aetiology)

Table 2.

Management of primary headaches

| Type of primary headache | Treatment available |

|---|---|

| Migraine | First-line pharmacotherapy[18-23] |

| Acute treatment | Combination of analgesics: |

| aspirin (250 mg)/caffeine (65 mg)/acetaminophen (250 mg) | |

| Combine triptans and NSAIDs: naproxen (500 mg)/sumatriptan (85 mg) (maximum dose: two tablets/day) | |

| Triptans | |

| Almotriptan, rizatriptan, eletriptan, frovatriptan, sumatriptan, naratriptan, zolmitriptan | |

| NSAIDs: | |

| Naproxen (250-500 mg orally 12 hourly, maximum dose- 1 g/day) | |

| Ibuprofen (200-800 mg orally 6-8 hourly, maximum dose- 2.4 g/day) | |

| Other effective pharmacotherapies[18-23] | |

| Ergotamines: dihydroergotamine | |

| Acetaminophen (325 mg)/isometheptene (65 mg)/dichloralphenazone (100 mg) | |

| Antiemetics: metoclopramide, prochlorperazine | |

| Dexamethasone IV | |

| Lidocaine IV | |

| 5-HT1Fagonist, lasmiditan[24] | |

| Calcitonin gene-related peptides such as rimegepant or ubrogepant[24] | |

| Injectable[17] | |

| Subcutaneous sumatriptan | |

| Neurostimulation[17] | |

| TMS. | |

| VNS | |

| Preventive treatment[17] | External trigeminal nerve stimulation |

| Oral and intranasal | |

| ARBs: lisinopril, candesartan | |

| Beta-blockers: propranolol, metoprolol, timolol, atenolol, nadolol | |

| CCBs: “flunarizine “ | |

| Anticonvulsants: topiramate, valproate | |

| Antidepressants: | |

| Tricyclics: amitriptyline | |

| SNRI: venlafaxine | |

| Nutraceuticals: “riboflavin, coenzyme Q10, magnesium, omega3, vit-D[25] | |

| Injectables | |

| CGRP pathway monoclonal antibodies | |

| Onabotulinumtoxin-A | |

| Neurostimulation | |

| External trigeminal nerve stimulation | |

| Occipital nerve stimulation | |

| High cervical spinal cord stimulation | |

| Transcranial magnetic stimulation | |

| Tension-type headache | Level A recommendation[28] |

| Acute treatment[26,27] | Ibuprofen 200-800 |

| Ketoprofen 25 mg | |

| Aspirin 500-1000 mg | |

| Naproxen 375-550 mg | |

| Diclofenac 12.5-100 mg | |

| Paracetamol 1000 mg (oral) | |

| Level B recommendation[28] | |

| Caffeine comb. 65-200 mg | |

| Prophylactic treatment[26] | First line |

| Amitriptyline. 30-75 mg | |

| Second line | |

| Mirtazapine.30 mg | |

| Venlafaxine.150 mg | |

| Third line | |

| Clomipramine 75-150 mg | |

| Maprotiline 75 mg | |

| Mianserine 30-60 mg | |

| Non-pharmacological treatment[26] | Psycho-behavioural treatments: |

| EMG biofeedback | |

| Relaxation training | |

| Cognitive-behavioural therapy | |

| Cluster headache | Triptans |

| Acute treatment[29-31] | Sumatriptan S/C (6 mg) |

| Zolmitriptan nasal spray. (5 and 10 mg) | |

| Sumatriptan nasal spray. (20 mg) | |

| Zolmitriptan. orally (10 mg) | |

| Oxygen | |

| High-flow mask (flow rate of 12-15 L/min, sitting position) | |

| Lidocaine nasal spray ipsilateral nostril at 4% and 10% | |

| Prophylactic treatment[29-31] | Verapamil |

| 360 and 560 mg/day, increased to up to 960 mg/day | |

| Lithium 0·6 and 0·8 mmol/L | |

| Topiramate 100 and 200 mg/day (monotherapy or add on to verapamil) | |

| Prednisolone | |

| Triptans- frovatriptan, or naratriptan | |

| Melatonin | |

| Calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibodies[32] | |

| Suboccipital blockade- greater occipital nerve with a mixture of lidocaine and a steroid (i.e. dexamethasone) | |

| Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation | |

| Spheno-palatine ganglion micro stimulator |

ARBs=angiotensin pathway blockers, CCBs=calcium channel blockers, EMG=electromyography, IV=intravenous, NSAIDs=nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, TMS=transcranial magnetic.stimulation, VNS=vagal nerve stimulation, SNRI=Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, CGRP=Calcitonin gene related peptide

On the other hand, secondary headaches are mostly acute and subacute, life threatening and tagged with mortality. The doctor in medicine outpatient department (OPD) or a resident in casualty/community health centre (CHC)/ first referral uni (FRU) needs to be quick and rational while evaluating a case of headache, and it is essential that a detailed clinical examination is done to rule out secondary headaches. (a) Neurogenic headache is acute, abrupt and holocranial, associated with infection/head trauma, rigidity of the neck, localising signs, vomiting and so on. (b) Ear, nose and throat (ENT) headaches are associated with vertigo, giddiness, otalgia, sinusitis and rhinitis. (c) Ophthalmological headaches are associated with signs and symptoms of glaucoma and refractive errors. (d) Psychogenic headaches are mostly caused by sleep disturbance, untreated mood disorders/psychotic disorders, as well as substance withdrawal syndrome [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Approach to a case of headache[10-13], BPPV: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

Secondary headaches require specialist consultation [Figure 1]. In neurogenic secondary headache, investigations such as computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and so on are done to rule out haemorrhages/infarct/space-occupying lesions (SOLs)/any other neurological abnormality. In ENT headaches, speculum examination, otoscopy, nasal endoscopy, CT scan para-nasal sinuses (PNS) and so on are performed. Ophthalmological headaches require slit-lamp examination, refractory error examination, fundoscopy, ophthalmoscopy and so on [Table l]. Psychogenic headaches can be diagnosed with detailed clinical history and Mental Status Examination (MSE).

High-Risk Headaches or Dangerous Headaches

It is difficult to distinguish high-risk headaches from benign ones because there are overlapping signs and symptoms.[8] The high-risk headaches are associated with certain red flag symptoms that are mostly established by consensus reports and observational studies. Thus, they may not be unequivocally precise in determining the severe underlying aetiologies among patients with headache. Hence, patients showing features of secondary headaches should be examined and investigated thoroughly to rule out any high-risk pathology. Various radiological examinations are available to make this task easier, such as CT scan and MRI. MRI is much more sensitive in identifying smaller lesions.[9]

Childhood Headache

In one study, it was found that 24%–90% of children present with headache as a symptom and the total prevalence is about 58.4% among children.[33] Among the school-going children, prevalence is equivalent in girls and boys,[33] rises with age in both genders and the surge is more in females than males during adolescence. The most common primary headache among children is none other than migraine.[34] Its prevalence in childhood is around 7.7%; however, it is underdiagnosed among children.[33] Cluster headaches as well as paroxysmal hemicranias, which are trigeminal autonomic cephalgias, are rare among children.[34] TTH is also seen in children with a prevalence of 5%–25%, and the age on onset is equivalent to 7 years. It may be precipitated by various psychosocial stressors as well as comorbid psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and mood illnesses.[35] In the paediatric group, secondary headaches occur mostly due to acute infections such as sinusitis, upper respiratory tract infection (RTI), systemic infections and so on. In a few cases, they may be due to chronic intracranial illnesses such as meningitis, encephalitis, brain abscess, brain tumours, SOLs, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, hydrocephalus, vascular malformations and others.[36,37] It has also been seen that unhealthy lifestyles lead to increased incidence of childhood headache, for example, high parental expectations, increased academic pressure, overinvolvement in extracurricular activities, increased screen time, cut-throat competitions, poor nutrition and reduced sleep.[38] Red flags and the approach to headache evaluation among children are similar to those of the adult population.

Management of Childhood Headache

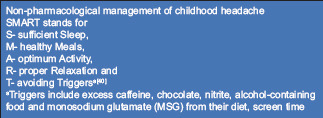

Non-pharmacological management

The child is advised to stay in a dark and quiet room in order to rest. Sleep and hydration often help.[35] SMART is an acronym which consists of various lifestyle modifications that can help in the management of childhood headache.

Pharmacological management

First-line acute pharmacological treatment of primary headaches, especially TTH, among children involves nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as paracetamol and/or ibuprofen adjusted to paediatric doses.[39] For acute management of migraine with and without aura among children, triptans can be given along with NSAIDs. For nausea and vomiting, domperidone, prochlorperazine and cyclizine may be added.[40] For trigeminal autonomic cephalgias (TACS), high-flow oxygen at 12 L/min has been recommended.[39] Prophylactic management of primary headaches is more or less same in children as in adults.

Headache in Geriatric Age Group

The prevalence of headache in older population is around 12%–50%.[41,42] Headache among elderly population is mainly due to primary headache such as migraine and TTH. However, the risk of secondary headache increases among elderly.[42,43] The risk of dangerous or high-risk headache rises 10 times among those aged 65 years and above.[42] It has been observed that secondary aetiologies such as vascular events cause sudden deaths among elderly, especially intracranial haemorrhage, rupture of aneurysm and cervical arterial dissection. In the presence of red flag signs, investigations among elderly population may vary and they should comprise various blood tests including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and neuroimaging techniques to rule out vascular anomalies or tumours/SOLs.[44] Most importantly, chronic disorders such as hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus should also be ruled out.

Primary headache

Once secondary headache disorders are ruled out, primary headache may be diagnosed.[44] Among those aged above 55 years, the 1-year prevalence was found out to be 35.8% in a review article.[45] It has been observed that there is higher risk of TTH among patients with depression, overuse of pain medication, as well as chronic pain and frequent headaches.[45] Among older adults, migraine is the second most common headache and the 1-year prevalence is around 10%.[43,46] Treatment of primary headache among older adults is similar to that of younger adults.

Secondary headache

Discussion

The approach of a doctor should be to get a thorough history of headache, which consists of the type, site, intensity and frequency, aggravating and relieving factors, course, duration and other associated characteristics. With available information, the next step is to ask leading questions in order to differentiate primary and secondary headache [Figures 1 and 2]. Arriving at a conclusion is very essential to plan further management [Table 2] or referral. Following guidelines helps to save time and avert confusion. A case of secondary headache may require further neurology/ophthalmology/ENT/psychiatric consultation depending on the history and examination [Table 1]. It is equally important that we identify the red flag signs and do the needful.

Red flag symptoms of high risk headaches

Medication overuse headache

Non-pharmacological management of childhood headache

Headache in elderly

Limitations

This review only includes the studies written in English language; so, several data are not included due to language constraint. Also, only reports available online are included in the study. Management of secondary headache could not be discussed in detail.

Conclusion

Algorithm-based approach to a disease is a classic concept. However, ours is an attempt to streamline the procedure that a patient has to follow through to get a proper treatment and referral, which is usually not done meticulously. We have also looked into headache in extreme age groups such as in geriatric and paediatric populations and how they are different from normal adults. This is one step in the direction of clinical and practical management of headache disorders. There is still room left for further improvement and modification.

List of abbreviations

DALY = disability-adjusted life years

TTH = tension-type headache

CH = cluster headache

NDPH = new daily persistent headache

HC = hemicranias continua

PHC = primary health care

CHC = community health centre

SOLs = space-occupying lesions

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Stovner Lj, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, Scher A, et al. The global burden of headache:A documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:193–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terrin A, Toldo G, Ermani M, Mainardi F, Maggioni F. When migraine mimics stroke:A systematic review. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:2068–78. doi: 10.1177/0333102418767999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mogilicherla S, Mamindla P, Enumula D. A review on classification, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and pharmacotherapy of headache. Innovare J Med Sci. 2020;8:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakal DA. Headache:A biopsychological perspective. Psychol Bull. 1975;82:369–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins MS, Lipton RB. The epidemiology of primary headache disorders. Semin Neurol. 2010;30:107–19. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Sliwinski M. Classification of daily and near-daily headaches:Field trial of revised IHS criteria. Neurology. 1996;47:871–5. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.4.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The International Classification of Headache Disorders:2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):9–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hainer BL, Matheson EM. Approach to acute headache in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:682–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edmeads J. Emergency management of headache. Headache. 1988;28:675–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1988.hed2810675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen R, Stovner LJ. Epidemiology and comorbidity of headache. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:354–61. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fumal A, Schoenen J. Tension-type headache:Current research and clinical management. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:70–83. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70325-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lance JW, Goadsby PJ. Mechanism and management of headache. Mech Manag Headache. 2005 doi:10.1016/B978-0-7506-7530-7. X5001-4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pryse-Phillips WEM, Dodick DW, Edmeads JG, Gawel MJ, Nelson RF, Purdy RA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of migraine in clinical practice. CMAJ. 1997;156:1273–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison TR, Longo DL, Dan L. Harrison's Manual of Medicine. New York, USA: mcgraw-hil; 2013. p. 550. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravishankar K, Chakravarty A, Chowdhury D, Shukla R, Singh S. Guidelines on the diagnosis and the current management of headache and related disorders. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011;14(Suppl 1):S40–59. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.83100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakravarty A, Mukherjee A, Roy D. Trigeminal autonomic cephalgias and variants:Clinical profile in Indian patients. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:859–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Antona L, Matharu M. Identifying and managing refractory migraine:Barriers and opportunities? J Headache Pain. 2019;20:89. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1040-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilmore B, Michael M. Treatment of acute migraine headache. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:271–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colman I, Brown MD, Innes GD, Grafstein E, Roberts TE, Rowe BH. Parenteral metoclopramide for acute migraine:Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2004;329:1369–73. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38281.595718.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandes JL, Kudrow D, Stark SR, O'Carroll CP, Adelman JU, O'Donnell FJ, et al. Sumatriptan-naproxen for acute treatment of migraine:A randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1443–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.13.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldstein J, Silberstein SD, Saper JR, Elkind AH, Smith TR, Gallagher RM, et al. Acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine versus sumatriptan succinate in the early treatment of migraine:Results from the ASSET trial. Headache. 2005;45:973–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrari MD, Roon KI, Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ. Oral triptans (serotonin 5-HT (1B/1D) agonists) in acute migraine treatment:A meta-analysis of 53 trials. Lancet. 2001;358:1668–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06711-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein J, Silberstein SD, Saper JR, Ryan RE, Jr, Lipton RB. Acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine in combination versus ibuprofen for acute migraine:Results from a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, single-dose, placebo-controlled study. Headache. 2006;46:444–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robbins MS. Diagnosis and management of headache:A review. JAMA. 2021;325:1874–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ariyanfar S, Razeghi Jahromi S, Togha M, Ghorbani Z. Review on headache related to dietary supplements. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2022;26:193–218. doi: 10.1007/s11916-022-01019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bendtsen L, Evers S, Linde M, Mitsikostas DD, Sandrini G, Schoenen J ;EFNS. EFNS guideline on the treatment of tension-type headache-report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:1318–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burch R. Migraine and tension-type headache:Diagnosis and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103:215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen RH. Tension-type headache-the normal and most prevalent headache. Headache. 2018;58:339–45. doi: 10.1111/head.13067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffmann J, May A. Diagnosis, pathophysiology, and management of cluster headache. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:75–83. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei DY, Khalil M, Goadsby PJ. Managing cluster headache. Pract Neurol. 2019;19:521–8. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2018-002124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Argyriou AA, Vikelis M, Mantovani E, Litsardopoulos P, Tamburin S. Recently available and emerging therapeutic strategies for the acute and prophylactic management of cluster headache:A systematic review and expert opinion. Expert Rev Neurother. 2020;21:235–48. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2021.1857240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei DY, Goadsby PJ. Cluster headache pathophysiology —insights from current and emerging treatments. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17:308–24. doi: 10.1038/s41582-021-00477-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abu-Arafeh I, Razak S, Sivaraman B, Graham C. Prevalence of headache and migraine in children and adolescents:A systematic review of population-based studies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:1088–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blume HK. Childhood headache:A brief review. Pediatr Ann. 2017;46:e155–65. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20170321-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raucci U, Della Vecchia N, Ossella C, Paolino MC, Villa MP, Reale A, et al. Management of childhood headache in the emergency department. Review of the literature. Front Neurol. 2019;10:886. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roser T, Bonfert M, Ebinger F, Blankenburg M, Ertl-Wagner B, Heinen F. Primary versus secondary headache in children:A frequent diagnostic challenge in clinical routine. Neuropediatrics. 2013;44:34–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1332743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis DW. Headaches in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faedda N, Cerutti R, Verdecchia P, Migliorini D, Arruda M, Guidetti V. Behavioral management of headache in children and adolescents. J Headache Pain. 2016;17:80. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0671-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kennis K, Kernick D, O'Flynn N. Diagnosis and management of headaches in young people and adults:NICE guideline. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:443–5. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X670895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitehouse WP, Agrawal S. Management of children and young people with headache. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2017;102:58–65. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hale WE, May FE, Marks RG, Moore MT, Stewart RB. Headache in the elderly:An evaluation of risk factors. Headache J Head Face Pain. 1987;27:272–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1987.hed2705272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pascual J, Berciano J. Experience in the diagnosis of headaches that start in elderly people. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:1255–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.10.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prencipe M, Casini AR, Ferretti C, Santini M, Pezzella F, Scaldaferri N, et al. Prevalence of headache in an elderly population:Attack frequency, disability, and use of medication. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:377–81. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.3.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Starling AJ. Diagnosis and management of headache in older adults. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:252–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crystal SC, Robbins MS. Epidemiology of tension-type headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14:449–54. doi: 10.1007/s11916-010-0146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haan J, Hollander J, Ferrari MD. Migraine in the elderly:A review. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:97–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramchandren S, Cross BJ, Liebeskind DS. Emergent headaches during pregnancy:Correlation between neurologic examination and neuroimaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1085–7. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramirez-Lassepas M, Espinosa CE, Cicero J, Johnston KL, Cipolle RJ, Barber DL. Predictors of intracranial pathologic findings in patients who seek emergency care because of headache. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:1506–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550240058013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dodick DW. Wolff's Headache and Other Head Pain. Dodick-Oxford University Press. 2007. [[Last accessed on 2021 Aug 16]]. Available from: https://global.oup.com/academic/product /wolffs-headache-and-other-head-pain-9780195 326567?cc=us&lang=en& .

- 50.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Steiner TJ, Silberstein SD, Olesen J. Classification of primary headaches. Neurology. 2004;63:427–35. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000133301.66364.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clinch CR. Evaluation of acute headaches in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:685–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version) Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629–808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toth C. Medications and substances as a cause of headache:A systematic review of the literature. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2003;26:122–36. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200305000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferrari A. Headache:One of the most common and troublesome adverse reactions to drugs. Curr Drug Saf. 2006;1:43–58. doi: 10.2174/157488606775252610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castillo J, Muñoz P, Guitera V, Pascual J. Kaplan Award 1998. Epidemiology of chronic daily headache in the general population. Headache. 1999;39:190–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1999.3903190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chiang C-C, Schwedt TJ, Wang S-J, Dodick DW. Treatment of medication-overuse headache:A systematic review. Cephalalgia. 2016;36:371–86. doi: 10.1177/0333102415593088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martins KM, Bordini CA, Bigal ME, Speciali JG. Migraine in the elderly:A comparison with migraine in young adults. Headache. 2006;46:312–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kelman L. Migraine changes with age:IMPACT on migraine classification. Headache. 2006;46:1161–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holle D, Naegel S, Krebs S, Katsarava Z, Diener H-C, Gaul C, et al. Clinical characteristics and therapeutic options in hypnic headache. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:1435–42. doi: 10.1177/0333102410375727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holle D, Naegel S, Obermann M. Hypnic headache. Cephalalgia. 2013;33:1349–57. doi: 10.1177/0333102413495967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]