Abstract

Background:

AYAs experience treatment non-adherence rates as high as 60%, which can increase the risk of cancer relapse. Involvement of the AYA in treatment decisions might support adherence to medical treatment.

Objective:

To explore the involvement of adolescents and young adults (AYAs), age 15–20, in cancer treatment decision making (TDM).

Methods:

Using interpretive focused ethnography, we conducted interviews with 16 AYAs (total 31 interviews) receiving cancer treatment within one year of diagnosis. Participants reflected on a major recent TDM experience (e.g., clinical trial, surgery) and other treatment decisions.

Results:

Participants distinguished important major cancer treatment decisions from minor supportive care decisions. We identified three common dimensions related to AYAs’ involvement in cancer TDM: 1) becoming experienced with cancer, 2) import of the decision and 3) decision making roles. AYAs’ preferences for participation in TDM varied over time and by type of decision. We have proposed a three dimensional model to illustrate how these dimensions might interact to portray TDM during the first year of cancer treatment for AYAs.

Conclusions:

As AYAs accumulate experience in making decisions, their TDM preferences might evolve at different rates depending on whether the decisions are perceived to be minor or major. Parents played a particularly important supportive role in TDM for AYA participants.

Implications for Practice:

Clinicians should consider the AYA’s preferences and the role they want to assume in making different decisions in order to support and encourage involvement in their TDM and care.

Background

Cancer is a leading disease-related cause of death among individuals between 15–39 years of age, defined as adolescents and young adults (AYAs) by the National Cancer Institute1. Progress in improving the cancer survival of AYAs has fallen behind that of their younger and older peers1,2 especially for AYAs between 15–25 years3,4. The cause for this disparity is likely multifactorial, but is possibly due to treatment non-adherence leading to increased risk of cancer relapse5. Patient discomfort with their participation in decision making might be a key factor in non-adherence; therefore, research to improve AYAs’ engagement in and satisfaction with their decision making could improve their outcomes6.

Participation in treatment decision making (TDM) in children, adolescents and young adults might improve autonomy, efficacy and sense of control, and increase adherence to medical management5–11 but participation could also be stressful and taxing10. Open communication, positive family relationships and AYA involvement in treatment decisions support adherence to medical treatment12,13, whereas paternalistic relationships with health professionals may reduce treatment adherence14.

AYAs are challenged to determine the degree of involvement they prefer when making treatment decisions. Children and adolescents with cancer, for instance, frequently do not participate in TDM to their level of preference and comfort15,16 and adolescents often feel dissatisfied and powerless6. They vary in their preference for involvement in TDM, from no involvement at one end of the spectrum, to making most or all of the decisions at the other8,11,17–19. Barakat and colleagues7 reported that acute psychological stress was a barrier to AYAs’ involvement in decision making about their participation in Phase III clinical trials and that increased maturity (developmental, cognitive or emotional) was associated with increased involvement.20

Participation of children and adolescents in TDM is complex because of the triangular interactions between the patient, health care provider (HCP) and parents who often assume a protective gatekeeper role21. Early in the cancer treatment, parents often take control of critical decision making, but as adolescents become experienced with cancer, they often want or demand to participate in TDM22,23, including end-of-life decisions24. Studies suggest AYAs differentiate between major decisions, which they believe are not really decisions at all, and minor decisions, like how care is delivered, that they want to participate in6. However, when AYAs make treatment decisions, they still want support and prefer shared decision making with family and clinicians8,16.

Major gaps in knowledge include understanding the AYA’s voice and preferences for TDM, the involvement of AYAs in the TDM process, and factors that contribute to or impede this process. Outcomes of TDM participation are not known, especially related to congruence or lack of congruence between their desired and actual TDM roles.

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore, from the perspective of young AYAs with cancer, their involvement in decisions about their cancer treatment. We sought to address these aims: 1) describe the AYAs’ preference for and actual involvement in their cancer TDM, including factors that influence TDM about their cancer, 2) explore the types of treatment and non-treatment decisions in which AYAs do and do not want to be involved, and 3) examine how AYAs interact with family, especially parents, in making treatment decisions. These results could, in the long term, empower clinicians to sensitively assist AYAs to participate in TDM and help them develop appropriate interventions. These interventions may also improve the AYA’s relationship with HCPs and improve both their and their family’s well-being.

Design and Methods

Study Design

In this study, we used focused ethnography in the sociological tradition, based on a symbolic interaction framework, including interviews and informal participant observation, to explore AYAs’ experiences with TDM related to their cancer therapy. The goal of focused ethnography is typically to investigate shared cultural and social phenomena, rather than cultural groups, as in the classic anthropological tradition25. Focused ethnography is problem-focused and context-specific, with a limited number of participants and an emphasis on interview, rather than observational data. In comparison to conventional ethnography, focused ethnography usually takes place over a short interval, but produces a large amount of data that requires intensive analysis26. Focused ethnography was well suited to understand the human experiences of AYAs with cancer and their level of involvement in the TDM process27. Discussing the AYAs experiences allowed us to interpret their everyday life experience and understand their world. The first author interviewed participants and observed them informally in clinic or hospital settings to understand their experiences and perspectives.

The theory of symbolic interactionism informs ethnography in the sociologic tradition. Bronfenbrenner’s28 Bioecological Theory of Human Development and Bandura’s29 Self- Efficacy Theory served as sensitizing theories, and were used to develop initial interview guides and informed analytic discussions. Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory30 proposes behavior and development as intertwined functions of the personality and the environment and posits that human behavior can be interpreted based on interactions in social structures of community, society, economics and politics that are named ecological levels. Essentially, the interaction between the individual and their environment is bidirectional. The individual’s belief in their ability to perform a specific behavior or task such as decision making is defined as self-efficacy by Bandura29. Together, these frameworks are useful for guiding investigation of AYA participation in TDM as a health behavior amenable to analysis and modification in the context of self-efficacy theory.

Study Participants

The purposive sampling plan included AYAs receiving treatment for cancer within one year of diagnosis at two quaternary pediatric oncology programs in the western United States. Inclusion criteria for the sample were AYAs who: 1) were between the ages of 15 and 25 (the upper age cared for at these pediatric centers) at the time of the interview, 2) were receiving initial treatment for cancer, 3) had been diagnosed with cancer between one month and one year prior to the interview, 4) had experienced a major cancer treatment decision including but not limited to: whether to enroll in a clinical trial, a surgical treatment decision or other treatment decision such as radiation therapy versus surgery, 5) were able to speak English, and 6) provided informed consent (parent if under age 18, and assent of AYA, own consent if 18 and older). AYAs were excluded if they experienced a disease relapse, end-of-life care, self-identified as non-English speaking, or were physically or cognitively unable to participate.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards at each center. Members of the treatment team approached potentially eligible AYAs and/or their parents about their willingness to participate in the study. The first author then met with the eligible AYA and his/her parents to review the study in more detail. The first author interviewed participants and collected all data. At the time of the study, she held a part-time clinical nurse specialist position at one of the centers. She was not involved in the direct clinical care of the participants and wore street clothes during the interview. Interviews were conducted in a private setting on either the outpatient or inpatient unit. In some (12/31) interviews parents were present, if preferred by the participant. Questions were addressed solely to the participant. The interviews were audio-recorded with the AYA’s permission. Participants were given a $25 gift card for each interview as compensation for their time and participation in the study.

Demographic Questionnaire and Interviews

An 11-item demographic questionnaire was completed with the AYA. Questions included age, level of education, whether they were currently in school, ethnicity, race, marital status, household members, and employment status. Demographic data are presented in Table 1. If symptoms were present on screening, they had the choice to reschedule the interview.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the 16 Study Participants

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Mean age in years at 1st interview (range) | 17.3 (15–20) |

| Gender (n, %) | |

| Male | 9 (56) |

| Female | 6 (38) |

| Non-binary | 1 (6) |

| Race (n, %) | |

| White | 6 (37.5) |

| Hispanic | 2 (12.5) |

| Asian | 4 (25) |

| Multiracial | 4 (25) |

| Cancer Diagnosis (n, %) | |

| Leukemia | 7 (44) |

| Lymphoma | 3 (19) |

| Bone Tumor | 6 (37) |

| Mean Months from Diagnosis to 1st interview (range) | 5.4 (1.4–9.7) |

| Treatment Decision (n, %) | |

| Clinical Trial Enrollment | 10 (63) |

| Radiation Therapy vs Surgery | 1 (6) |

| Surgical Options | 5 (31) |

Interviews were guided by open-ended and semi-structured questions informed by a pilot study of four cancer survivors (not included in the current study) diagnosed with cancer as an AYA. Members of an AYA Advisory Council reviewed the interview guide and provided feedback. The interview guide consisted initially of broad questions about when participants were diagnosed with cancer. Early in the interview, questions focused on a recent major treatment decision, how they participated in the decision and what influenced their decision-making role. Other questions centered on everyday life, including decisions AYAs made about how to incorporate considerations related to their cancer into their school and social life.

Second interviews were conducted to expand upon and verify preliminary findings. The guide for each participant’s second interview was developed to ask clarifying questions, explore further questions more deeply and to conduct member checking of preliminary findings.

Data Analysis

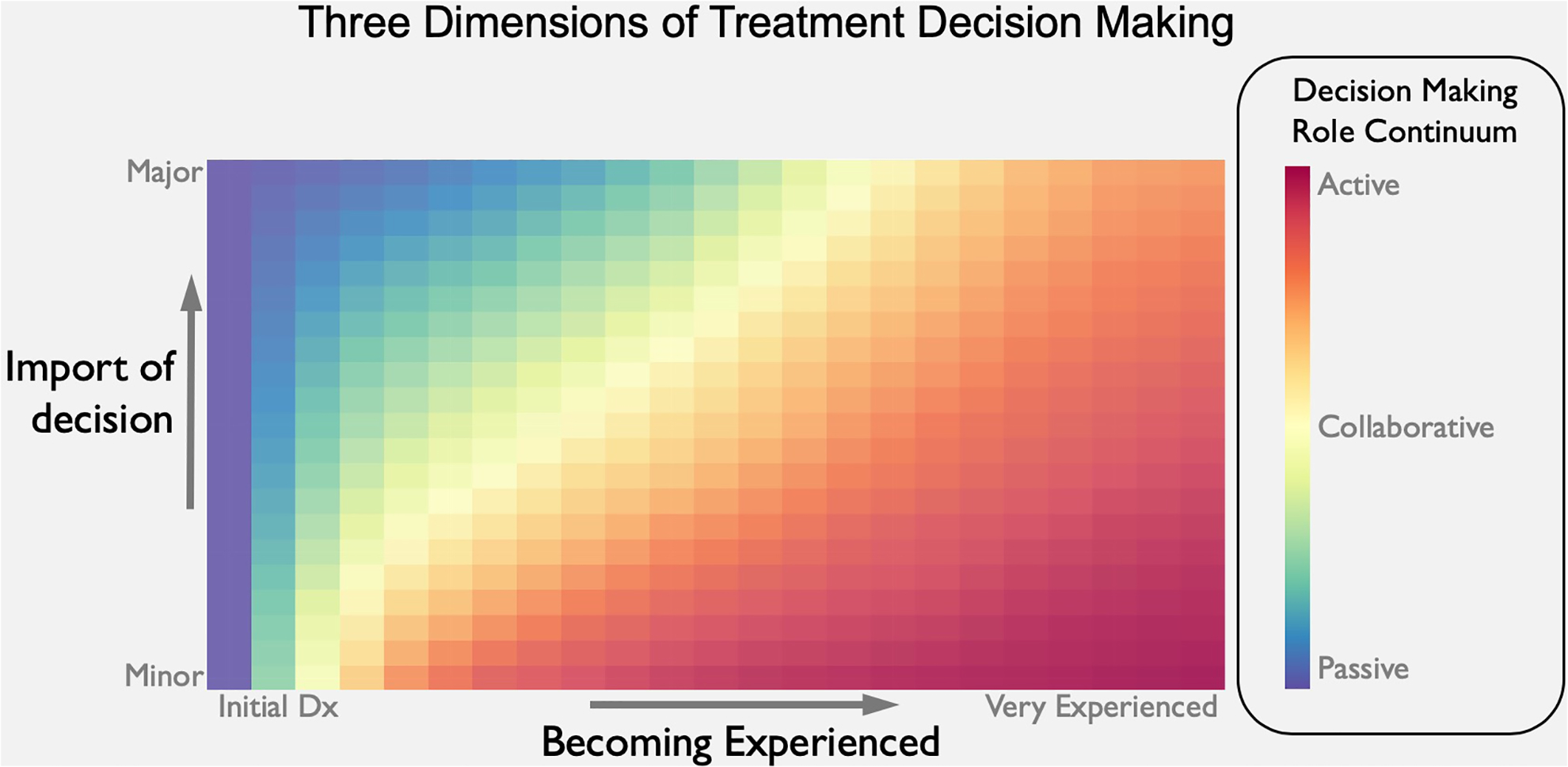

The interviews were transcribed and reviewed for accuracy. Field notes following each interview were transcribed. The transcripts were reviewed multiple times and analysis was conducted iteratively throughout and after data collection by the first author. Transcripts were coded, focusing on the feelings, actions, decisions and interactions of participants27. Codes were combined into categories which were used to conduct a second level of focused coding. This involved recoding data into related categories and combining categories. Following this, the major dimensions were identified and related to form the hypothesized model presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Three Dimensions of Treatment Decision Making.

Heat map depiction of postulated relationships portrayed along three different axes.

To ensure rigor, findings were discussed to consensus with members of the research team during the analysis period, including semi-weekly meetings with the senior author during periods of active analysis. Symbolic interaction was useful for data collection and analysis by responding to participants’ words with further probes during interviews and discussing with them their self-reflections and experiences since diagnosis. Reflexive notes were written into field notes. ATLAS-ti31 software was used for data analysis and organization.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Seventeen AYAs were approached to participate, one AYA declined, because he did not want to talk. Of the 16 participants, 15 were interviewed twice and one was interviewed once. Participants’ age at the time of cancer diagnosis ranged from 14.7 – 20 years old. The average age at the first interview was 17.3 years (range 15.2–20.6 years). The diagnoses included acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=6), acute myeloblastic leukemia (n=1), lymphomas (n=3), osteosarcoma (n=5), and Ewing sarcoma (n=1). Several AYAs became emotional (i.e., teared up or cried) when discussing their diagnosis, their friends and how life was different now. No participant chose to stop the interview prematurely.

The average time from diagnosis to the time of the first interview was 5.4 months (range 1.4 – 9.7 months). The second interview took place a median of 22 days after the first interview (range 1–74 days). The interviews lasted on average 64 minutes (range 30–97 minutes) for the first interview and 60 minutes for the second interview (range 37–97 minutes). No discernable patterns of difference in data from the internviews were noted based on whether or not a parent was present.

Dimensions of Decision making

We identified three dimensions of decision making for AYAs’ involvement in cancer TDM: 1) becoming experienced with cancer, 2) import of the decision, and 3) decision making roles (Table 2). Here, we dissect this web of interactions to allow each of these three dimensions to be illuminated.

Table 2.

Dimensions of Treatment Decision Making

| Dimension | Definition |

|---|---|

| Becoming experienced with cancer | Relates to the AYAs’ experience over time. At diagnosis they are naive and inexperienced. They are new to the cancer experience. Over time they gain experience with decision- making and learn about their disease and treatment. |

| Import of the decision | Relates to how the AYA determines what decisions are more important than others. This may relate to the consequences or potential outcomes of the decision. It also relates to how easy or hard the decision was to make. |

| Decision making roles | Relates to the type of decision making role that AYAs assume in various treatment decisions or care preferences. This may include an active, collaborative or passive role. |

Dimension 1: Becoming Experienced with Cancer

Receiving the diagnosis.

Shortly after diagnosis, participants often described themselves as sad, angry, frightened, in shock, and unable to retain information. It felt “surreal” and they thought they might die.

Initial events often happened quickly, such as diagnostic procedures and decisions such as whether or not to enroll in a clinical trial. Over time, and at their own pace, the AYAs became experienced with cancer and its treatment. Cancer evolved from an amorphous threat to something of more substance that they could understand and interact with. One AYA recounted her experience as follows:

The more you get into it, the more it becomes real and the more it like is actually what’s happening. Like once you finally understand that this is something you have to do, then over time …you’ll get more comfortable ‘cause you’ll know what happens, like how to go about doing things and stuff.

Learning about cancer.

Participants sought information by asking family, but rarely friends, for advice or their opinion, and searched the internet to better understand their condition and treatment. More than half of the AYAs (9/16) used the internet to look up information about their disease and/or its treatment. One participant described her need for information in the following way: “They tell you not to Google things but I don’t like that advice because then I have no idea what I’m walking into, right? So, I did a lot of research.”

Over time, they understood more about their condition and became more comfortable with their understanding of cancer. A participant recounted:

…now it’s like I kind of know everything. I don’t know everything, but I know a lot more. When they say stuff, I can think about it and connect it with other things, and so I don’t have to look up every term that they say now. In the beginning, I was so confused the entire time.

Information was important in making decisions.

Wanting to know about the treatment options and the time spent researching these options was also related to the importance of the decision. Once their initial information needs are addressed, the need for subsequent information decreased over time. As one participant remembered, “Because in the beginning I had less questions, and then I peaked in questions and I had to do lots of Googling and reading of like PubMed and stuff, and now I have less questions.”

Participants learned about their care through observing their HCPs as they delivered care to them and other patients, and by listening to discussions during bedside rounds or clinic visits. They learned a new language. Being part of discussions and listening even helped them to be less scared. Most participants asked their HCPs questions directed at the plan and side effects of treatment, usually focused on the effects in the immediate future.

In contrast to wanting information and being part of discussions, another participant described how she wanted information on a “need to know” basis only. She advocated for herself the right to self-regulate, so if the discussion became too much for her she would be able to remove herself without having to explain. She describes, “sometimes it’s a little hard to (say) ‘get out’, ‘cause I don’t want to be mean or anything, be like ‘I don’t want to hear this.’ But I’m getting better at standing up for myself.”

Some became more engaged over time. Others commented that decision making increased over time because they had more information and became more knowledgeable.

Managing cancer.

Participants became actively engaged in their own care and experienced at determining their care preferences. One AYA explained how with experience and trying different options for accessing his subcutaneous injection port, he found what worked best.

With experience they learned to identify and respond to illness symptoms. The AYAs often learned the side effects of their treatment and would notify the team or their parents if they were experiencing them. One 16-year-old described how she managed her symptoms at home:

If I didn’t feel well, I would try to see if the medication is working, see if they try to make me feel better. But if I feel like there’s definitely something wrong, then I immediately call the oncologist… and like one case was that I wasn’t feeling very well, kept throwing up. I don’t think I can take my antibiotic or take any more food in ‘cause I feel like I will vomit it back.

Developing an understanding of roles of health care team members.

As they became more knowledgeable about their disease and treatment and learned the language of their illness, participants learned how to communicate with team members:

They also became discriminating, realizing that different physicians or team members have different expertise. AYAs therefore learned whom to talk with about different issues or if they had specific questions. One participant described how, before making the decision about which surgical procedure to undergo, it was important to get the surgeon’s opinion.

Dimension 2: Import of the Decision

Distinguishing different types of decisions.

Participants described types of decisions, and how meaningful they were in their treatment, as easy versus hard, big versus little, and major versus minor, and framed them in terms of consequences or impact, reversibility and their future. Decisions ranged from supportive care decisions, sometimes regarded as care preferences and considered to be of lesser consequence, to more momentous, life-threatening decisions of greater consequence—such as whether or not to have surgery, or participate in a clinical trial—that involved others’ assistance or input. When they compared a clinical trial or surgical decision to supportive care decisions, the former were often described in terms of being life-altering or threatening and longer term. One AYA compared deciding about a clinical trial to a supportive care decision:

I think for something like the clinical thing [trial], it’s just something on a much larger scope. Like this is the treatment that I’ll be going down for three years. You know, I want to be able to like weigh the options myself. But then for something like nausea, it is maybe an afternoon of uncomfortableness and then the next day it just kind of repeats. But like I don’t think you really get the same chance with a clinical trial.

A 19-year-old commented about the distinction between decisions of different import:

But for example, with the port, if I want to count to three, then I suddenly decide I don’t want to count to three, that’s fine. With the surgery, if I’m like I want a reverse and then a month later I’m like, “Oops, so can I get the other version instead?” that’s not going to work.

In contrast, several participants did not view clinical trial enrollment as a major decision. Sometimes, making these decisions involved trusting providers and involving others. Participants explained there were not always a lot of decisions to be made after deciding on the treatment plan. For them, most decisions were not really big decisions. One participant recounted, “I haven’t actually had any big decisions to make since the decision. It’s kind of like there aren’t as many places where I can make decisions”

Some decisions, despite their importance, had only one obvious choice in the view of the participants, so were sometimes described by them as a ‘no-brainer.’ For example, for one 15-year-old, the decision to undergo fertility preservation was easy and her choice.

Two participants described decisions they did not want to be involved in. One AYA described decisions related to stem-cell transplant and the other described decisions about advance directives. These decisions about what might happen in the future were uncomfortable.

Minor decisions.

Minor decisions involved preferences for care or symptom management and not long-term consequences. From early on AYAs were involved in supportive care TDM. These included their involvement in symptom management (i.e. nausea, pain, and mucositis), how to access their port, and procedure-related decisions (i.e. bone marrow biopsy or lumbar puncture). They became engaged in these types of decisions relatively soon in their cancer experience: classifying them as minor. Participants described how they partnered with the nurse practitioner to determine their best antiemetic regimen, or with the anesthesiologist to determine the best type of anesthesia for a procedure.

For some of their care it did not always matter if they were asked their opinion. It was more important that the HCP “get it right.” For instance, for procedures like accessing their port or starting an IV, they wanted the nurse to do whatever he or she needed to do to be successful.

Intermediate decisions.

These were decisions that were not minor, were important, but not life threatening such as fertility preservation, self-management, or the decision to electively admit oneself to the hospital. In the context of day-to-day decisions, one AYA described how she knew when she needed to go to the hospital and made the decision to advocate for admission:

A lot of times I choose to be like “I need to go to the ER right now.” That’s a decision ‘cause I usually am the one who like says tapping out, like I need to go to… the hospital ‘cause that’s what I need to feel better.

Major decisions.

Major decisions were critical, where the consequences will last a lifetime, such as choosing between various limb salvage surgical options or amputation. As described above, AYAs were readily able to distinguish these decisions as being higher stakes, with greater consequences and different from other decisions they participate in.

Dimension 3: Decision-Making Roles

AYAs’ decision making roles varied depending on the type of decision and when these decisions occurred during their treatment course. For decisions related to whether to enroll in a clinical trial or other types of treatment choices for their cancer, most AYAs said they were involved in making the decision, but defined this in a variety of ways. Some of their decision making roles can be described in terms of a continuum: active, passive, or collaborative. Supportive care and symptom management decisions were located at the minor end of the continuum, and were typically AYA-led. More momentous decisions, with potential long-term consequences such as limb salvage, were at the major end of the continuum and required more consultation and consideration. These decisions were more collaborative or led by parents or HCPs. Participants were able to distinguish treatment decisions from care preferences.

Active Role (decision made by themselves).

For surgical decisions, two participants with osteogenic sarcoma said they “made the decision.” Both participants were almost 18 years old at the time of the decision. As young adults, they were the primary decision maker when it came to their cancer treatment. It was “my choice,” “my body” and it was happening to them. They listened to the physician’s recommendations, asked questions, weighed the options, researched the topic, and made the best decision for themselves. They accepted this role and responsibility.

Family had a role in supporting them in their healthcare decisions. Their parents assumed the primary supportive role but the AYAs did accept input from HCPs as well. They did not often turn to their friends or extended family for assistance in making treatment decisions but usually kept them informed if the friend was considered to be close. One AYA commented:

It’s nice to have input, like the input of the surgeon and the input of my parents and the input of the Internet and the input of other people. But I do think in the end, it’s still my decision.

Time was an important modifier for those treatment decisions that were not required at the time of diagnosis. For two participants who had osteosarcoma and whose surgery did not take place for several months they had time to think about and research their surgical options:

It did give me time to like come to a good decision… but it was enough time that I didn’t feel like I was stressing to like learn stuff. Like I didn’t feel like I was cramming for a test.

Making these decisions, meant taking ownership and actively seeking information from multiple sources, educating themselves and talking to providers, family and sometimes friends. Consequently, they felt comfortable and in charge of these decisions.

Collaborative role (decision made by themselves and the parent(s) and/or their physician(s)).

More than half of the AYAs (11/16) made the major treatment decision in collaboration with their parents and/or HCPs. When clinical trials were being discussed, parents wanted the AYA to be included in the discussion. There was no obvious relationship between age and the choice of a collaborative or passive role.

Participants perceived that parents encouraged their participation in discussions, making decisions about clinical trials and choosing between surgical options. They accepted and appreciated their parents’ involvement. They believed that parents and physicians looked out for their best interests and were their advocates and protectors. One participant described:

When the doctors talked to us, they talked to all three of us, my parents and me, not just my parents. They would include me in the conversation…so all the doctors and myself and my parents decided [tx] would be better.

Participants described their overall trust in the team during their treatment. They recognized that their physicians have knowledge and experience in dealing with cancer and respected this. They expressed positive feelings about their relationship with their team and they developed close relationships with those with whom they interacted regularly. As young adults, they came to rely on these relationships with physicians during times of TDM. Parents typically maintained an active role in the decision making process: “Even though I’m an adult and I’m in control of what happens, I still go with what my parents tell me on a lot of things. I’ll never make a decision without asking other people on this stuff.”

Passive role (decision made by parent(s) and/or their physician(s)).

For three participants, their parents mostly made the decision about their cancer treatment. For this group, treatment decisions related to whether to enroll in a clinical trial at diagnosis. Factors about the disease or illness influenced decisions they were part of making. The AYAs often did not want the responsibility or were too overwhelmed or ill to participate.

At the time of diagnosis and during early treatment planning, some participants recalled a sense of urgency. Things happened quickly and there were no major, or optional, decisions to be made. They were either too ill or overwhelmed to participate in discussions about their treatment and recall their parents participated in making the treatment decision. One participant did not remember participating in the discussion or decision about the clinical trial because of the pain she was experiencing at the time. Several passive participants recalled not being present during initial treatment discussions but being informed after the decision was made.

AYAs across all decision-making groups (active, collaborative, passive) wanted to be included in things that affected them, especially major decisions. Even though the participant may not have made the final decision, most felt they were involved and had a voice in the decision. One participant commented how he felt that he had more say over time because he became more knowledgeable and experienced and the team respected him. Over time their involvement in decision making either stayed the same or increased.

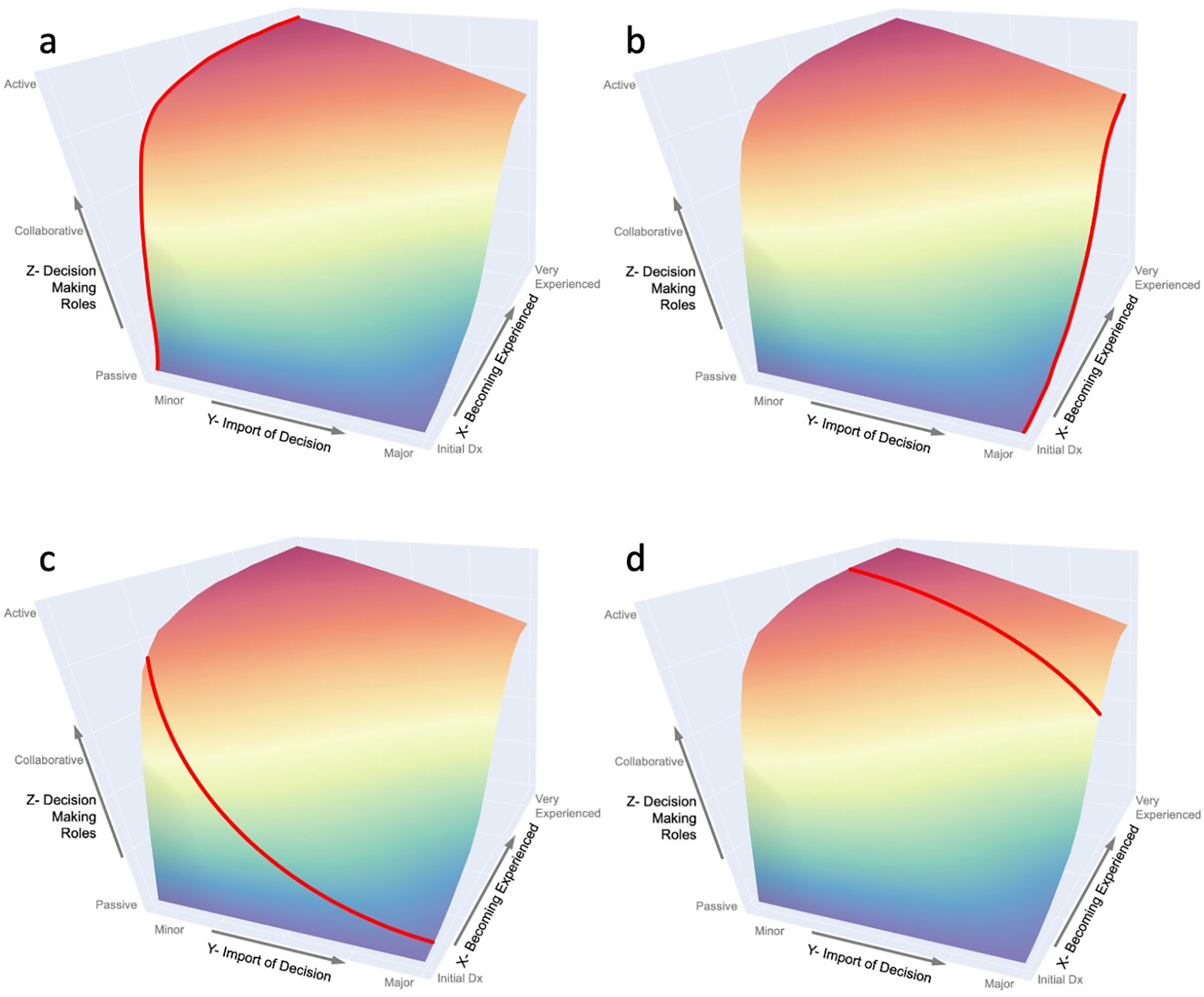

Treatment Decision Making Model

Most AYAs start out naïve and progress from passive to more active over time. Decision making for minor and major decisions progresses at different rates. Individual variation in the trajectory and interaction of the three dimensions can be visualized on a three-dimensional heat map with each of the axes, x (becoming experienced), y (import of the decision), and color (decision making roles), displaying one of these three dimensions of TDM (Figure 1). This Three Dimensions of Treatment Decision Making Heuristic Model (Figure 1) is a potential explanation for AYA TDM where the progress the AYA makes along each dimension may be independent of each other, or, more likely they may interact as the AYA develops experience with their cancer. Experience allows the AYA to participate and become engaged in TDM about their cancer treatment. Participants were readily able to distinguish the dimension of the “import of the decision” early on. They articulated and discussed a range of decisions from those of lesser import, such as supportive type care decisions about symptom management through to life changing decisions about their cancer treatment, such as deciding on a surgical option or whether to enroll in a clinical trial. The dimension of “decision making roles” varies depending on the type of decision and where the AYA is on the “becoming experienced with cancer” dimension. Participants described their increasing involvement in decisions with experience, generally beginning with a passive or collaborative approach to major decisions at the time of diagnosis, followed by their increasing involvement in supportive care decisions (minor), progressing to more self-management decisions (intermediate) about their disease and treatment. Figure 2 illustrates the same information in a three-dimensional surface graph view.

Figure 2. Example trajectories illustrated by red line overlaying graph:

a) The AYA rapidly becomes active early in their experience in making minor decisions, b) The AYA takes longer to become active in making major decisions. c) Early in their experience , the AYA rapidly becomes active in making minor decisions, while remaining relatively passive with respect to major decisions, d) The more experienced AYA is active in minor decisions and becoming more active in major decisions.

Discussion

This study used interpretive focused ethnography to further our understanding of the AYA’s involvement in cancer TDM and how decisions are made within the context of family, during the acute phase of treatment. Our findings indicate that TDM by the AYA and their families is a complex, dynamic, social process. TDM is multidimensional and includes the AYA’s experience with cancer, the import of the decision and their TDM roles. Identifying the relationship between these three important dimensions has not been previously reported and might contribute to an increased understanding of AYA cancer TDM.

During initial stages, the participants were naïve to cancer. In accordance with Tenniglo et al.32, newly diagnosed patients must negotiate a major change in their life circumstances. Day and colleagues33 described adolescents’ experience at this time as a loss of control and agency. At diagnosis for instance, there was urgency to start treatment and for illness reasons, the AYA might not be able to, or chose not to, participate in discussions or TDM.

Over time and at different rates, AYAs learn the nuances of their disease and treatment. Becoming experienced might lead to readiness or building confidence in making treatment decisions. The participants wanted varying amounts of information and often sought information from the internet, educated themselves, reported symptoms or asked questions about their care or self-management. They wanted to know what the plan was and how decisions were going to impact them, as is also reported in other studies10,34.

Most participants felt they had a collaborative role in major TDM. These results are similar to Mack et al.,19 study of 15–29 year olds with cancer. Very few participants took the lead in making early major decisions. Several passive participants could not recall being present during initial treatment discussions but were informed about the decision afterward. This is consistent with studies reporting parents or HCP’s may take control of critical TDM early in the cancer treatment22,23 6,35. Some AYAs’ TDM involvement evolved over the course of their disease trajectory to become more active.

Participants could distinguish important major cancer treatment decisions from minor supportive care decisions that typically occurred more frequently. In Coyne’s6 study, children and adolescents similarly distinguished between major and minor decisions. Decision making roles varied with the context of the decision. The AYAs were active in making most of the supportive care, less consequential or lower risk decisions with occasional consultation with their parents. This finding is consistent with those of Tenniglo et al.32, who reported similar findings in 12–18 year old patients, and Ruhe et al.10, in younger children and adolescents.

The role of family in making major decisions was very important to the AYA even though AYAs of age 18 are legally adults. This suggests we must interpret recommendations to solely involve AYAs as much as possible, with caution, because full independence may not be their preference and could actually contribute to further stress. Fostering collaboration between AYAs and parents might be optimal.

We found for decisions that involved treatment options a few older, more experienced participants described themselves as the primary decision maker. For more collaborative participants or those who were not able to participate in discussions about cancer treatment decisions, parents attempted to include them in discussions. A few assumed a passive role at diagnosis due to stress or illness. This study extends the findings from a study by REDACTED that showed that children and adolescents’ involvement in treatment discussions were influenced by what was happening to the child at the time, such as their clinical situation.

Some AYAs prefer that their parents make potentially life-altering decisions. This is not uncommon during the early phases of the disease; however, as they progress through the cancer experience, most AYAs naturally start taking more control over decisions. Expecting participation when it is not desired might lead to anxiety36. Also, it is possible that adherence and other outcomes might be optimized if there is congruence between their preferred type of participation and their actual participation in the TDM process.

The timing of the decision might effect the AYA’s TDM experience and role. The decision about a clinical trial usually occurred immediately after diagnosis. In contrast, other treatment decisions, such as surgical, occurred several months later, allowing time to explore options.

This study suggests TDM as something that evolves over the course of the AYA’s cancer disease trajectory. Involvement in discussions and decisions about their care may facilitate decisional confidence and a more active role in subsequent TDM. Taking the lead in decisions about supportive care might improve long-term adherence with medical management. The practice in making healthcare decisions, the positive feedback and acknowledgement of their importance in the process might lead the AYA to commit to increased adherence.

The heuristic model (Figure 1) based on data and literature, portrays the progression of TDM over time and experience, and could help HCPs and AYAs understand the trajectory of patients along the TDM continuum. When they are newly diagnosed most AYAs are naïve and tend to be passive (Figure 2a & b). After gaining some experience, they assume an active role with minor decisions but remain passive or collaborative with major decisions (Figure 2c). Some AYAs, especially those with complicated illness trajectories, may reach a point where they are actively involved in important decisions such as choosing end-of-life care or participation in a Phase I trial (Figure 2d)37,38. Further studies could help validate this model and determine how it interacts with social processes affecting the AYA, family, the health care team and cancer treatment, and variables such as age, gender, prognosis, phase in treatment and information needs.

Practice and Research Implications

Experience, import of the decision, and decision making roles are dimensions that impact the AYA’s involvement in TDM and change over time. Health care providers could consider where the AYA is on these three dimensions when decisions are being made. Their approach to the AYA and their care could be tailored to where the AYA is on these three dimensions.

Our findings also highlight the important role of parents in TDM and the relationship with HCPs throughout the continuum of care. Partnering with the AYA and parents, is critical to determining their role in cancer TDM and how best to facilitate alignment with AYA and parental goals. This is an opportunity for HCPs to promote quality patient and family-centered care by involving AYAs in TDM.

Additional research focusing on how these three dimensions interact is warranted. Understanding the roles of the AYAs, parents and HCPs, and their perceptions surrounding AYA TDM would be useful for designing interventions. Therapeutic approaches tailored to the individual needs of the AYA can encourage optimal participation and eventually improve psychological and treatment outcomes. It is also necessary to examine TDM longitudinally to understand changes in AYAs’ TDM for instance at relapse or end-of-life, and whether involvement in minor decisions promotes self-efficacy related to involvement in major decisions or if their participation in TDM correlates with long-term outcomes such as adherence. It would be useful to investigate whether the use of decision aids developed for the AYA are of benefit in assessing their preferences for TDM. Understanding how to engage AYAs in different types of TDM and self-management decisions related to their care is another area worthy of investigation as they ultimately prepare to transition to an independent adult cancer survivor. Studies in older AYAs might also be necessary based on the work of Arnett39 on emerging adulthood to provide perspective on how the role of family changes.

Limitations

AYAs might have been wary about sharing negative information and therefore gave socially acceptable responses. To mitigate this, the first author was supportive and accepting of their responses. It is unknown if the presence of parents during some of the interviews affected the AYA’s responses. Only AYA views were elicited, so alternate perspectives of AYA TDM from parents or HCPs were not included in the analyses. The experiences of this sample might not be reflective of those who are older or who are living independently from their families. Though the sample included participants from several ethnic groups, future research should include more diverse samples, or focus on particular racial/ethnic groups to learn about cultural influences on TDM. This study was conducted at two geographically close oncology programs so it is possible that approaches to involving AYAs in TDM might vary in other regions.

Conclusion

This study has extended knowledge about AYA involvement in cancer TDM. This analysis focused on describing three identified dimensions of AYA TDM. The first dimension, “becoming experienced,” was identified as an important phenomenon that the AYAs lived through. The second dimension, “import of decision,” delineated how the AYA distinguished decisions. The third dimension, “decision making roles,” described the types of TDM roles the AYA assumed in various decisions. During the acute phase of treatment, AYAs’ role in TDM might change over time depending on their experience and type of decision. Findings also highlight the important role of parents in TDM and the relationship with HCPs throughout the continuum of care. It might be important for clinicians to consider the AYAs’ preferences and role they want to assume in making different decisions in order to support and encourage their involvement in their TDM and care.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants and members of the clinical teams for their contributions to this study.

Funding

This work was supported by research described in this article was funded by the National Research Service Award from the National Institute of Nursing Research, grant number 5F31NR015951 and an American Cancer Society Pre-doctoral Award

Dr. Robert Goldsby is funded by Swim Across America.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Bleyer A, Ferrari A, Whelan J, Barr RD. Global assessment of cancer incidence and survival in adolescents and young adults. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2017;64(9). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis DR, Seibel NL, Smith AW, Stedman MR. Adolescent and young adult cancer survival. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 2014;2014(49):228–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleyer A, Ulrich C, Martin S. Young adults, cancer, health insurance, socioeconomic status, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Cancer. 2012;118(24):6018–6021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albritton K, Caligiuri M, Anderson B, Nichols C, Ulman D. Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer Report of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. 2006. https://www.cancer.gov/types/aya/research/ayao-august-2006.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2014.

- 5.Butow P, Palmer S, Pai A, Goodenough B, Luckett T, King M. Review of adherence-related issues in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(32):4800–4809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coyne I, Amory A, Kiernan G, Gibson F. Children’s participation in shared decision-making: children, adolescents, parents and healthcare professionals’ perspectives and experiences. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2014;18(3):273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barakat LP, Schwartz LA, Reilly A, Deatrick JA, Balis F. A Qualitative Study of Phase III Cancer Clinical Trial Enrollment Decision-Making: Perspectives from Adolescents, Young Adults, Caregivers, and Providers. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. 2014;3(1):3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coyne I, Gallagher P. Participation in communication and decision-making: children and young people’s experiences in a hospital setting. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2011;20(15–16):2334–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly KP, Mowbray C, Pyke-Grimm K, Hinds PS. Identifying a conceptual shift in child and adolescent-reported treatment decision making: “Having a say, as I need at this time”. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2017;64(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruhe KM, Badarau DO, Brazzola P, Hengartner H, Elger BS, Wangmo T. Participation in pediatric oncology: views of child and adolescent patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2016;25(9):1036–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snethen JA, Broome ME, Knafl K, Deatrick JA, Angst DB. Family patterns of decision-making in pediatric clinical trials. Research in Nursing and Health. 2006;29(3):223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sawyer SM, Aroni RA. Self-management in adolescents with chronic illness. What does it mean and how can it be achieved? The Medical Journal of Australia. 2005;183(8):405–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albritton K, Bleyer WA. The management of cancer in the older adolescent. European Journal of Cancer. 2003;39(18):2584–2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyngas H, Hentinen M, Barlow JH. Adolescents’ perceptions of physicians, nurses, parents and friends: help or hindrance in compliance with diabetes self-care? Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;27(4):760–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unguru Y The successful integration of research and care: how pediatric oncology became the subspecialty in which research defines the standard of care. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2011;56(7):1019–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zwaanswijk M, Tates K, van Dulmen S, Hoogerbrugge PM, Kamps WA, Bensing JM. Young patients’, parents’, and survivors’ communication preferences in paediatric oncology: results of online focus groups. BMC Pediatrics. 2007;7:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broome ME, Richards DJ, Hall JH. Children in research: The experience of ill children and adolescents. Journal of Family Nursing. 2001;7(1):32–49. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knopf JM, Hornung RW, Slap GB, DeVellis RF, Britto MT. Views of treatment decision making from adolescents with chronic illnesses and their parents: a pilot study. Health Expectations. 2008;11(4):343–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mack JW, Fasciano KM, Block SD. Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients’ Experiences With Treatment Decision-making. Pediatrics. 2019;143(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearce S, Brownsdon A, Fern L, Gibson F, Whelan J, Lavender V. The perceptions of teenagers, young adults and professionals in the participation of bone cancer clinical trials. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2016:epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young B, Dixon-Woods M, Windridge KC, Heney D. Managing communication with young people who have a potentially life threatening chronic illness: qualitative study of patients and parents. British Medical Journal. 2003;326(7384):305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller VA. Parent-child collaborative decision making for the management of chronic illness: a qualitative analysis. Families, Systems & Health : The Journal of Collaborative Family Healthcare. 2009;27(3):249–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller VA, Reynolds WW, Nelson RM. Parent-child roles in decision making about medical research. Ethics and Behavior. 2008;18(2 & 3):161 – 181. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller VA, Harris D. Measuring children’s decision-making involvement regarding chronic illness management. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2012;37(3):292–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wall S Focused Ethnography: A Methodological Adaptation for Social Research in Emerging Contexts. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2015;16(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knoblauch H Focused Ethnography. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2005;6(3):44. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prus RC. Symbolic interaction and ethnographic research: Intersubjectivity and the study of human lived experience. New York, NY: Suny Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bronfenbrenner U The Ecology of Human Development. Harvard College, USA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bandura A Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bubolz MM, Sontag MS. Human Ecology Theory. In: Boss P, Doherty WJ, LaRossa R, Schumm WR, Steinmetz SK, eds. Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods: A Contextual Approach. New York, NY: Springer; 2008:419–450. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meadows LM, Dodendorf D. Data management and interpretation-using computers to assist. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999:195–218. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tenniglo LJA, Loeffen EAH, Kremer LCM, et al. Patients’ and parents’ views regarding supportive care in childhood cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2017;25(10):3151–3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Day E, Jones L, Langner R, Bluebond-Langner M. Current understanding of decision-making in adolescents with cancer: A narrative systematic review. Palliative medicine. 2016;30(10):920–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stegenga K, Ward-Smith P. The adolescent perspective on participation in treatment decision making: a pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2008;25(2):112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coyne I Children’s participation in consultations and decision-making at health service level: a review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2008;45(11):1682–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beaver K, Luker KA, Owens RG, Leinster SJ, Degner LF, Sloan JA. Treatment decision making in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Cancer Nursing. 1996;19(1):8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hinds PS, Drew D, Oakes LL, et al. End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(36):9146–9154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller VA, Baker JN, Leek AC, et al. Adolescent perspectives on phase I cancer research. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2013;60:873–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arnett JJ, Padilla-Walker LM. Brief report: Danish emerging adults’ conceptions of adulthood. Journal of adolescence. 2015;38:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]