Abstract

The Pseudomonas asiatica strain PNPG3 was documented to possess chemotactic potential toward p-nitrophenol (PNP), and other nitroaromatic compounds. Initial screening with drop plate and swarm plate assays demonstrated significant movement of the strain toward the test compounds. A quantitative capillary assay revealed the highest chemotactic potential of the strain toward 4-Aminophenol (4AP), (CI: 12.33); followed by p-benzoquinone (PBQ), (CI: 6.8); and PNP, (CI: 5.33). Gene annotation revealed the presence of chemotactic genes (Che), (Methyl-accepting Proteins) MCPs, rotary motor proteins, and flagellar proteins within the genome of strain PNPG3. The chemotactic machinery of the strain PNPG3 comprised of thirteen Che genes, twenty-two MCPs, eight rotary motors, and thirty-four flagellar proteins that are involved in sensing chemoattractant. Two chemotactic gene clusters were recorded in the genome, of which the major cluster consisted of two copies of CheW, one copy of CheA, CheY, CheZ, one MotD gene, and several Fli genes. Various conserved regions and motifs were documented in them using a standard bioinformatics tool. Genes involved in the chemotaxis of strain PNPG3 were compared with three closely related strains and one distantly related strain belonging to Burkholderia sp. Considering these phenotypic and genotypic data, it can be speculated that it is metabolism-dependent chemotaxis; and that test compound activated the Che. This study indicated that strain PNPG3 could be used as a model organism for the study of the molecular mechanism of chemotaxis and bioremediation of PNP.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-023-03809-3.

Keywords: Chemotaxis, P-nitrophenol, Pseudomonas asiatica, Methyl-accepting protein, Whole genome sequencing

Introduction

P-Nitrophenol (PNP) has been widely and extensively used in industries for the chemical synthesis of plastics, dyes, paints, pharmaceuticals, and pesticides, resulting in high levels of contamination in almost all environments (Bhushan et al. 2000; Alam and Saha 2022a). Due to its water solubility, it is considered highly mobile and might have contaminated the drinking water sources, thereby causing water pollution (Kuang et al. 2020). The river Ganges of the northern Indian subcontinent provides a freshwater source of livelihood for millions of populations dwelling alongside the river. However, over the past few decades, several fertilizers, paints, pharmaceuticals, petrochemicals, and tannery industries have grown along the banks of the river Ganges (Roy and Shamim 2020). Huge discharges of this industrial wastewater and urban drainage have contaminated the river Ganges (Ghirardelli et al. 2021). Its uncontrolled release into the aquatic ecosystem via industrial waste and agricultural applications such as methyl parathion, and parathion-based pesticides has been documented in the literature (Prakash et al. 1996). River Ganges was reported to be fifth-ranked, among the most polluted river on our planet as of 2007 (Jhariya and Tiwari 2020). PNP is highly toxic and is reported to have carcinogenic and mutagenic effects on living organisms (Kulkarni and Chaudhari 2006a). PNP is also reported to plays a role in the dysfunction of the liver, kidney, and other important physiological life processes of animals (Kuang et al. 2020). The maximum permissible limit of PNP is documented to be 10 ng/ml in natural water bodies (Kulkarni and Chaudhari 2006b). This recalcitrant xenobiotic compound is considered a priority pollutant by US-EPA (1980). This is a huge threat to the public and ecosystem (biodiversity and sustainable functioning) (Sengupta et al. 2019). Consequently, effective subsidence and removal of such hazardous xenobiotic compounds are urgently required.

Reports in the literature suggest that several bacterial genera are involved in PNP biodegradation either catabolically or cometabolically including Flavobacterium sp. (Sethunathan and Yoshida 1973), Sphingomonas sp UG30 (Alber et al. 2000), Arthrobacter protophormae RKJ100 (Chauhan et al. 2000), Achromobacter xylosoxidans Ns strain (Wan et al. 2007), Serratia sp DS001 (Pakala et al. 2007), Ochrobatrum sp. B2 (Qiu et al. 2007), Citriococcus nitrophenolicus sp. PNP1 (Nielsen et al. 2011), Sphingobacterium sp. RB (Samson et al. 2019), Rhodococcus sp. strain BUPNP1 (Sengupta et al. 2019), Brachybacterium sp strain DNPG3 (Alam and Saha 2022a).

Bioremediation and biodegradation by microorganisms provide a promising alternative method for the detoxification of environmental pollution (Ibrahim 2016). Chemotaxis is one of the well-known adaptive response. By this mechanism, microorganisms can perceive, locate, interact, respond, and degrade a particular compound. This phenomenon ensures a clean, green, and eco-friendly aquatic ecosystem, in addition to rescuing major aquatic animals from the deleterious effects of toxic compounds. Bioavailability of these target compounds may take place either by adhesion of bacteria to the non-aqueous phase or by target compound dissolution in the aqueous phase. Some bacterial genera showed chemotactic behavior toward xenobiotic compounds, including Ralstonia sp. SJ98 (Samanta et al. 2000), Acidovorax sp. strain JS42 (Rabinovitch-Deere and Parales 2012), Pseudomonas sp. JHN (Arora and Bae 2014), Pseudomonas sp. strain BUR11 (Pailan and Saha 2015), Bacillus subtilis PA-2 (Arora et al. 2015), Cupriavidus sp. strain CNP‑8 (Min et al. 2018). However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, reports are lacking for chemotactic behavior on PNP intermediates like PBQ. Again, very few reports are available on annotated genes/proteins involved in chemotaxis.

Strain PNPG3 was isolated from river Ganges water sample and was identified as Pseudomonas asiatica using genome sequence-based criteria (Alam and Saha 2022b).

To establish relationship between xenobiotic compound degradation and chemotaxis, the chemotactic behavior of the Pseudomonas asiatica strain PNPG3, (with well-established PNP biodegradation potential) was monitored against different xenobiotic compounds, so that its applicability toward bioremediation process (ex-situ) may be attempted, in future. Thus, in the present manuscript, chemotactic responses of this strain were explored toward recalcitrant, mutagenic,and carcinogenic compounds such as PNP, PBQ, and 4AP, to develop effective methods for the detoxification and removal of such hazardous compounds. The strain PNPG3 showed the best chemotactic potential toward 4AP, followed by PBQ, and PNP. This is the first report of chemotaxis by bacterial strain under Pseudomonas asiatica and also the first report of chemotaxis toward PBQ. This manuscript will broaden our knowledge of the chemotaxis of bacteria toward PNP and its major degradation intermediates as well as 4AP. In addition, genes and proteins responsible for encoding the chemotaxis property were specifically identified by the genome mining from the genome sequence of the bacterium. The study confirms the presence of diverse genomic attributes related to its chemotaxis, in the genome of strain PNPG3, which might have functional significance toward PNP metabolisms and / or degradation.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

PNP and other degradation intermediates were purchased from Merck/Sigma/HiMedia. Solvents used in this study were of HPLC grade. Microbiological media (MM), general chemicals, and components were purchased from HiMedia, India.

Selection of bacterial strain and growth curve study on different xenobiotic compounds

Pseudomonas asiatica strain PNPG3 was isolated by enrichment technique (Alam and Saha 2022b) and it was selected to grow on MM with different concentrations of several nitroaromatic compounds viz; [PNP (0.5 mM); PBQ (0.25 mM); 4AP (0.2 mM)]. Growth in broth media was measured by recording changes in the OD600 values by using a UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan) at every 4 h of interval.

Assessment of chemotactic responses

The chemotactic activity of the strain PNPG3 toward different nitroaromatic compounds were investigated qualitatively (by drop plate and swarm plate assays) and quantitatively by capillary assay following established methods (Pandey et al. 2012; Arora and Bae 2014; Pailan and Saha 2015).

Drop plate assay

The drop plate assay medium [MM—0.3% agarose (Chromous Biotech, India)] was inoculated with 100 µl cells (4.6 × 108 CFU/ml) and poured into Petri plates (55 mm; Tarsons, India). In the center of the semisolid plate, two–three crystals of the respective nitroaromatic compounds were placed and incubated at optimum temperature. The chemotactic response was recorded after 12 h of incubation. Surrounding the crystals, a positive response was indicated by the formation of concentric rings due to bacterial cell accumulation. MM-glucose was used as a positive control. Ring formation was analyzed due to the chemotactic accumulation of bacterial cells. The experiment was conducted in a set of triplicates. MM-glucose was used as the positive control.

Swarm plate assay

Swarm plate assay medium (MM-0.2% agarose) was supplemented with the optimal response concentration of nitroaromatic compounds and poured into the 55 mm Petri plates. About 100 μl (4.6 × 108 CFU/ml) of cell suspension was added to the center of the plate and incubated at optimum temperature. A positive chemotactic response was recorded by the formation of exocentric rings after 12 h of incubation. MM-glucose was used as the positive control. The experiment was performed thrice.

Capillary assay

For the quantitative determination of chemotactic responses, a chemotactic index by capillary assay was performed. Different concentrations of nitroaromatic compounds (from 50 to 500 µM in 50 µM increments) were prepared in the chemotactic buffer (100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) and 20 µM EDTA). Quantitation of the chemotactic response of strain PNPG3 toward different analytes (PNP, PBQ, 4AP) was performed by using a capillary assay. A 10 µl graduated glass capillary tube [Spectrochem pvt. ltd. (Mumbai, India)] was filled with a solution of NC (test compounds) (dissolve in HPLC grade acetonitrile) separately and the suction end was sealed by sterile agarose gel till the nitroaromatic compound reach the 10 µl of the capillary tube. Each of these capillary tubes was inserted into microcentrifuge tubes (separately) containing cell suspension (4.6 × 107 CFU/ml) of strain PNPG3 and incubated at 28 °C for 30 min. The contents of the capillary tubes were serially diluted up to 10–5 and plated 5 μl of diluted culture onto a non-selective medium (Tryptone soya agar plate). After overnight incubation at optimum temperature, the colony-forming units were counted. The chemotactic response was determined in terms of the chemotaxis index (CI), which is the ratio of the number of bacterial cells accumulated in the test capillary containing nitroaromatic compound to that of control (i.e., without any chemotactic compound, just chemotaxis buffer). Glucose was used as the positive control. The experiment was performed thrice.

Genome sequence and annotation

The Illumina HiseqX platform (read length of 151 bp) was used for sequencing the draft genome of strain PNPG3. The metaSPAdes assembler (v3.11.1) pipeline (Nurk et al. 2017) was used for the De novo assembly of the strain. Sequences were further annotated by submitting the sequence to the RAST (Aziz et al. 2008), PATRIC (https://www.patricbrc.org) (Wattam et al. 2014) server, and PGAP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/annotation_prok/) (Tatusova et al. 2016).

Analysis of chemotaxis gene clusters/proteins

PATRIC, PGAP, and RAST platforms were used to confirm the existence of chemotaxis gene clusters /proteins. Che of the strain PNPG3 were manually extracted and compared with Pseudomonas sp. 13159349 (CP045553.1), Pseudomonas sp. SW144 (CP026674.1), Pseudomonas sp. JS425 (CP073661.1), and Burkholderia sp. SJ98 (AJHK00000000) for the determination of homologous genes. Transmembrane helices of chemotaxis-related genes were confirmed by TMHMMv2.0 (Krogh et al. 2001). Multiple sequence alignment of the chemotactic proteins (CheA, CheB, CheZ, CheY, CheR, CheV, and CheW) were compared with the above-mentioned strains for the determination of the conserved region of the protein performed by Clustal Omega (Sievers et al. 2011). Conserve domain combinations of each chemotaxis gene were determined by the SMART (Letunic et al. 2006) database.

Accession numbers

The 16S rRNA gene sequence accession number of the strain PNPG3 at GenBank is MW350013. The bacterial strain was deposited in MTCC, IMTECH, Chandigarh (accession no-MTCC13126) for general availability to the scientific community. Raw read genomic data and nucleotide sequence of the strain was deposited to NCBI (accession no- SRR18163134 and JALLKV000000000, respectively).

Results and discussion

Growth study of strain PNPG3

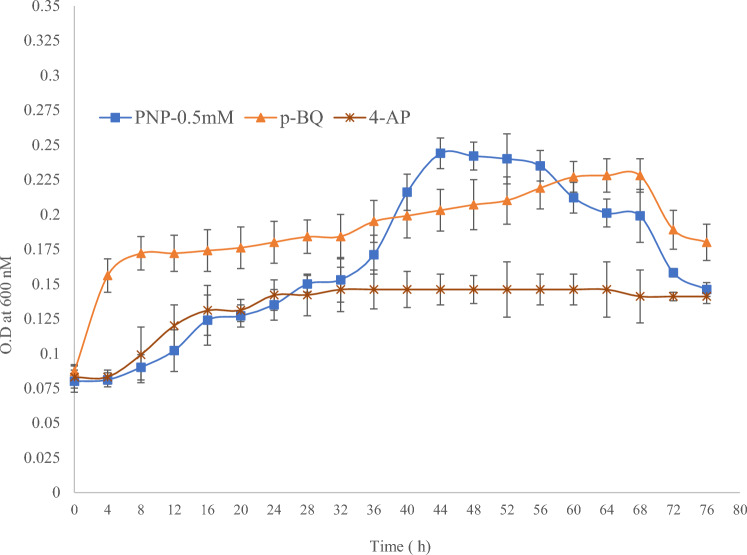

A study of comparative growth patterns revealed that the strain PNPG3 could utilize PNP, PBQ, and 4AP very efficiently as a sole source of carbon for its growth (Fig. 1). However, a higher OD600 value was recorded in the case of PNP than for the other two compounds. This result indicated that the strain PNPG3 prefers PNP rather than PBQ or 4AP for efficient growth. Although the strain could tolerate 6 mM of PNP, its optimum growth was recorded at 0.5 mM. The ability of the motile strain PNPG3 to utilize different nitroaromatic compounds encouraged us to investigate its chemotactic response toward those compounds. A similar type of growth study was reported by Pailan and Saha (2015) when they were working with Pseudomonas sp. strain BUR11.

Fig. 1.

Comparative growth curve of strain PNPG3 in presence of PNP (0.5 mM); p-benzoquinone (0.25 mM); 4-aminophenol (0.2 mM)

Chemotactic assay

The chemotactic behavior of Pseudomonas asiatica strain PNPG3 was monitored against three different xenobiotic compounds by using both qualitative (drop plate and swarm plate assay) as well as quantitative assay techniques.

Drop plate and swarm plate assay

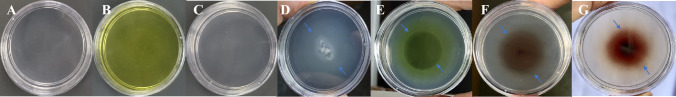

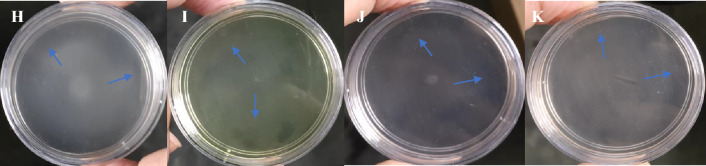

In the drop plate assay, the strain PNPG3 showed positive chemotactic potential toward glucose, PNP, PBQ, and 4AP. A distinct migration ring was observed in all the test compounds (Fig. 2). The swarm plate assay experiment revealed that strain PNPG3 showed chemotactic potential due to the formation of an exocentric ring (Fig. 3). Although, the ring was not so prominent. This might happen due to the uniform solubility of such compounds.

Fig. 2.

Drop plate assay for strain PNPG3—A Blank-only glucose, No inoculum; B Only PNP, No inoculum C No nitroaromatic compound, no inoculum; only MM + agarose D Glucose + PNPG3 E PNP + PNPG3 F p-benzoquinone + PNPG3 G 4-Aminophenol + PNPG3

Tahir et al. (2022) reported positive chemotaxis of Bacillus subtilis strain MB378 toward different dyes such as mordant black 11, direct 28, and acid orange 52. Again, xenobiotic compounds such as polychlorinated biphenyl, biphenyl, and benzoate were reported to attract Pseudomonas sp. B4 (Gordillo et al. 2007). On the contrary, reports are available for negative chemotaxis by the strain Bacillus subtilis PA-2 for several xenobiotic compounds (4-chloro-2-nitrophenol, PNP, and 2,6-dichloro-4- nitrophenol) (Arora et al. 2015).

Quantitative capillary assay

To quantify the chemotactic potential of the strain PNPG3 toward different compounds, the capillary assay was performed. The graph reveals that the chemotactic index increases with increasing the concentration of compounds until an optimal concentration was reached and then the chemotaxis index declines (Fig. 4). Thus, here semi-bell-shaped curve and concentration-dependent chemotaxis was recorded. Considering the CI, strain PNPG3 showed the best chemotactic potential for 4AP (CI: 12.33), followed by PBQ (CI: 6.8) and PNP (CI: 5.33). Results from qualitative chemotaxis assays were strongly supported by the findings of the quantitative assays. Previously, Pailan and Saha (2015) reported the positive chemotactic potential of P. sp. strain BUR11 toward different xenobiotic compounds (parathion, chlorpyrifos, 4-AP, PNP, and TCP) via both qualitative and quantitative assays. While Pseudomonas putida PRS2000 was reported to show chemotactic behavior toward benzoate and chlorobenzoates (Harwood et al. 1990). Cupriavidus sp. strain CNP‑8 was reported to exhibit positive chemotaxis toward 2-chloro-4-nitrophenol, 2-chloro-5-nitrophenol, and PNP (Min et al. 2018).

Fig. 4.

Quantitative chemotactic response of strain PNPG3 towards different test compounds using capillary assays

Annotations of chemotactic genes

Bioinformatics analyses (carried out at RAST, PGAP, and PATRIC server) revealed that the chemosensory machinery of Pseudomonas asiatica strain PNPG3 consisted of thirteen Che genes (one CheA, one CheB, two CheV, one CheR, six CheW, one CheY, one CheZ); twenty-two MCPs (Supplementary Table 1); eight rotary motors (MotA, MotB, MotD, FliG, FliM, FliN) (Supplementary Table 2); thirty-four flagellar proteins (Supplementary Table 3). A total of seventy-seven proteins are responsible for the chemotaxis of the strain PNPG3.

The cytoplasmic histidine kinase, CheA (locus tag- MJ643_21610; JALLKV010000039) was 2235 nt long, and documented 99.87% amino acid sequence homology with the CheA protein of Pseudomonas asiatica (WP_196184030.1); whereas the methylesterase CheB (locus tag- MJ643_24290; JALLKV010000051) shared 100% amino acid sequence homology with the cheB of Pseudomonas sp (WP_013973112.1). A detailed homology of chemotaxis family members (Che gene) of Pseudomonas asiatica strain PNPG3 is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

BLASTX homology search for chemotaxis gene cluster of strain PNPG3

| Locus tag PGAP; Protein ID | Homology (%) | E value | Score | Function | Origin (Accession no.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MJ643_21610, JALLKV010000039); MCK2123184 | 99.87 | 0.0 | 1194 | Chemotaxis protein CheA | Pseudomonas asiatica; (WP_196184030.1) |

| (MJ643_24290, JALLKV010000051); MCK2123701 | 100 | 8e-119 | 345 | Chemotaxis protein CheB | Pseudomonas sp; (WP_013973112.1) |

| (MJ643_12965, JALLKV010000016); MCK2121496 | 100 | 0.0 | 631 | Chemotaxis protein CheV | Pseudomonas sp; (WP_013971705.1) |

| (MJ643_26105, JALLKV010000060); MCK2124053 | 100 | 0.0 | 600 | Chemotaxis protein CheV | Pseudomonas sp; (WP_038410062.1) |

| (MJ643_26110, JALLKV010000060); MCK2124054 | 99.64 | 0.0 | 569 | Protein Glutamate O-methyltransferase CheR | Pseudomonas sp; (WP_015271244.1) |

| (MJ643_21600; JALLKV010000039), MCK2123182 | 100 | 3e-85 | 254 | Chemotaxis response regulator CheY | Pseudomonas sp. (WP_023663319.1) |

| (MJ643_21605; JALLKV010000039) MCK2123183 | 100 | 1e-156 | 444 | Protein phosphatase CheZ | Pseudomonas sp. (WP_023663318.1) |

| (MJ643_13830; JALLKV010000017), MCK2121667 | 100 | 3e-156 | 441 | Chemotaxis protein CheW | Pseudomonas sp. (WP_013971213.1) |

| (MJ643_13840; JALLKV010000017), MCK2121669 | 100 | 8e-117 | 338 | Chemotaxis protein CheW | Pseudomonas sp (WP_013971211.1) |

| (MJ643_21635; JALLKV010000039) MCK2123189.1 | 100 | 0.0 | 556 | MULTISPECIES: chemotaxis protein CheW | Pseudomonas sp. (WP_013970975) |

| (MJ643_21640; JALLKV010000039), MCK2123190.1 | 100 | 4e-110 | 320 | chemotaxis protein CheW | Pseudomonas putida SJ3 (ERT15993) |

| (MJ643_23050; JALLKV010000045), MCK2123460 | 100 | 4e-107 | 314 | Chemotaxis protein CheW | Pseudomonas sp. (WP_003257767.1) |

| (MJ643_23035; JALLKV010000045), MCK2123457 | 100 | 7e-105 | 306 | Chemotaxis protein CheW | Pseudomonas sp. (WP_015272077.1) |

Most of the MCPs had two transmembrane helices, as determined by TMHMM v 2.0. Only one MCP (locus tag- MJ643_00440; JALLKV010000001; Protein id- MCK2119068) had three transmembrane helices (Supplementary Table 1) and four MCPs (MCK2120874, JALLKV010000002; MCK2119471, JALLKV010000007; MCK2120376, JALLKV010000010, and MCK2122837; JALLKV010000033) had one transmembrane helix. Two MCPs (protein Id- MCK2119068, JALLKV010000001, and MCK2119729, JALLKV010000003) had transmembrane helices with a probability score of more than 0.8 (computed by TMHMM2.0).

The abundance of MCP-coding genes (twenty-two) in the genome of strain PNPG3 plausibly indicates an increased requirement for sensing environmental cues in the subsurface environment.

From the genome analysis, it was evident that two chemotaxis gene clusters were in contig 39 (JALLKV010000039) and contig 60 (JALLKV010000060). The major gene clusters (JALLKV010000039) had one copy of CheA, CheY, CheZ, and two copies of CheW along with several Fli genes and one MotD gene (Fig. 5A); whereas, the other cluster had one copy of CheV and CheR with several Flg, Fli genes (Fig. 3B). Other Che like CheB, CheV, rest of the CheW, and MCPs were recorded to be dispersed within the genome of strain PNPG3 (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). In contrast, Caulobacter crescentus had two gene clusters; of which the major cluster is solely responsible for chemotactic movement toward different carbon sources while both the clusters play a pivotal role in holdfast formation and biofilm production (Berne and Brun 2019).

Fig. 5.

A and B Documentation of the Che gene clusters in the genome of strain PNPG3

Fig. 3.

Swarm plate assay for strain PNPG3—H Glucose + PNPG3 (I) PNP + PNPG3 (J) p-benzoquinone + PNPG3 (K) 4-AP + PNPG3

As per Li et al. (2007), Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 genome harbored a gene encoding a parA-family protein, which was positioned between the CheB gene and a CheW domain protein, whereas in the case of strain PNPG3, the parA gene was located between the MotD and CheW genes, similar to Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAOI. The E. coli chemotaxis pathway comprises of 11 genes, with the majority of them arranged in a cluster in close proximity to the flagellar genes (Blattner et al. 1997), whereas the Che are dispersed throughout the genome of strain PNPG3 (Supplementary Table 1, 2, 3).

Comparison of chemotaxis genes of PNPG3 with Pseudomonas sp. 13159349 (CP045553.1), Pseudomonas sp. SW144 (CP026674.1), Pseudomonas sp. JS425 (CP073661.1), Burkholderia sp. SJ98 (AJHK00000000) revealed that strains SW144 and SJ98 possessed all of the Che in multiple numbers, whereas some of the important genes (CheZ) are absent in strains 13159349 and JS425. The CheW gene was present in multiple copies in strain PNPG3 (six) similar to strains SJ98 (four) and SW144 (two), but a single copy was present in rest two strains. A list of chemotactic proteins is summarized in Table 2. The existence of numerous Che homologs and clusters strongly suggests the existence of various pathways, prompting intriguing inquiries regarding their functions and whether these pathways overlap or have redundant functions.

Table 2.

Comparative account of Che gene homologs among close relatives of strain PNPG3

| Character | Genes present in strain PNPG3 | Pseudomonas sp. 13159349 | Pseudomonas sp. SW144 | Pseudomonas sp. JS425 | Burkholderia sp. SJ98 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CheA | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| CheB | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 |

| CheR | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| CheY | 1 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| CheW | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| CheZ | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| CheV | 2 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

To determine the conserved sequences among the chemotaxis genes, homologous sequences were searched against the selected strains and conserved sequences were determined using Clustal Omega. Conserved sequences of the chemotaxis genes were summarized in Table 3. The SMART database revealed that CheA consists of the Histidine phosphotransfer domain (HPT), signal-transducing histidine kinase domain (H-kinase_dim), and histidine kinase-like ATPase (HATPase_C), signaling adaptor domain CheW, and three low complexity regions. The domain architecture of each of the chemotaxis genes is summarized in Table 4. Li et al. (2007) reported that loss-of-function mutation of CheA gene results in the complete loss of swimming toward acceptor molecules in the swarm plate assay medium, although growth the strain was not hampered.

Table 3.

Conserved amino acid residues among different Che proteins of Pseudomonas sp

| Protein name | Conserved sequences |

|---|---|

| CheA | EA-KG-VRD-PL-HL-RN-DHG-GK-DDG-PGFS-SGRGVG-PLTL-PL-DG-LI-DV |

| CheB | GG-AL-PG-RP-DG-MP |

| CheR | DF-GI-SRL-GI-TTN-FR-EPYSI-ERL-NL-FD-FCRNV-IYF-KPG-LF-SE |

| CheV | IN-KV-LT-GV-RG-DL-TE-IV-DDS-VA-EM-EMDG-SL-KF |

| CheW | L-G |

| CheY |

MKIL-VDDF-TMRRI-NLL-LG-EA-DG-DF-TDWNMP-RA-PVL- VTAE-II-AA-AG-NGYV-KPFTA-KI |

| CheZ | LTR-DA-RL-YV-TE-AA-AL-SFL-LAQD-QDLTGQVIK-LL-GPQI-DVV-VDDLL-SLGF |

Table 4.

Domain architecture of different chemotaxis genes of strain PNPG3

| Protein | Domain architecture |

|---|---|

|

CheA (MCK2123184 JALLKV010000039) |

|

|

CheB (MCK2123701 JALLKV010000051) |

|

|

CheV (MCK2121496; JALLKV010000016) |

|

|

CheR (MCK2124054 JALLKV010000060) |

|

|

CheY (MCK2123182 JALLKV010000039) |

|

|

CheZ (MCK2123183 JALLKV010000039) |

|

|

CheW (MCK2123189.1 JALLKV010000039) |

|

|

MCP (MCK2119068 JALLKV010000001) |

The presence of chemotaxis-specific methylesterase, MotA, MotB, and MotD were recorded in the genome of Pseudomonas asiatica strain PNPG3 (Supplementary Table 2). The MotA genes were present in three copies, whereas the MotB and MotD gene was present in a single copy. Mot genes were responsible for torque generation in bacterial flagellar movement; therefore they are essentially required for bacterial chemotactic response (Stolz and Berg 1991). A rotary motor gene cluster was recorded in contig 39 (JALLKV010000039) of this genome. The presence of chemotaxis-related genes within the genome of strain PNPG3 and experimental demonstration of chemotactic properties suggest that these genes actively participate in chemotaxis mechanisms. Similar, genomic attribute-phenotypic associative outcomes were also reported by Kumar et al. (2013) and Tahir et al. (2021).

Tahir et al. (2022) reported that contig 5 of Bacillus subtilis MB378 contained eight Che genes and MCPs. Similarly, Burkholderia sp. SJ98 genome exhibited the presence of thirty-seven Che genes and nineteen chemotactic MCPs, responsible for the chemotaxis of nitroaromatic and chloroaromatic compounds (Kumar et al. 2013). Pereira et al. (2004) reported that β- proteobacterium and Chromobacterium violaceum contained sixty-seven chemotaxis-related genes, distributed in ten gene clusters (forty-one MCPs and twenty-six Che genes including CheD, CheV, CheR, CheA, CheB, CheY, CheZ) which sense the environmental stimuli and respond according to the stimulus.

Several reports are available elaborating that chemotaxis protein (Che genes) and MCPs play important roles in chemotaxis. In E. coli, MCPs sense the chemical gradient and transfer the signal to the histidine kinase protein CheA (Ni et al. 2013). Thus, MCPs play an important role in chemotaxis. The CheW protein binds with CheA and MCPs to form a ternary complex, but the function of CheW is not clear (Pereira et al. 2004). CheA is a dimeric, soluble protein, phosphorylated by two response regulator proteins, CheB, and CheY (Porter et al. 2011; Kumar et al. 2013). Phosphorylated CheY then binds to the flagellar motor proteins FliM and FliN, promoting the clockwise movement of the bacterium. (Pereira et al. 2004; Porter et al 2011). Thus, CheY protein regulates the flagellar motor movement. Signaling termination occurs by dephosphorylation of CheY-P protein by several phosphatases like CheC and FliY in Bacillus subtilis; CheZ in E. coli (Porter et al. 2011). The CheC protein plays an important regulatory role to balance the CheY-P level by dephosphorylating CheY-P protein (Kumar et al. 2013). Both CheB and CheR have methyl-transferase properties. CheR methylates the MCP protein, whereas CheB demethylates it. When the flagellar motor rotates anticlockwise, E coli cell is attracted toward the compounds and vice versa (Porter et al. 2011). Iwaki et al. (2007) reported that NtdY of Acidovorax strain JS42 and NbaY of Pseudomonas fluorescens strain KU-7 act as MCPs for 2-nitrotoluene and 2-nitrobenzoate respectively.

The strain was neither attracted to 2,4,6-trichlorophenol and 4-chloro-2-nitrophenol nor these compounds could be utilized as a sole source of carbon for their growth, indicating the absence of metabolism-independent chemotaxis. The strain PNPG3 was reported to carry out catabolic utilization (Alam and Saha 2022b) and positive chemotactic responses toward all three test compounds (write them) (in this study) as well as the occurrence of genome-encoded attributes (i.e., genes) responsible for chemotaxis (in this study). Such a type of chemotaxis is known as metabolism-dependent chemotaxis (Pandey and Jain 2002). Metabolism-dependent chemotaxis toward other nitroaromatic compounds has also been reported in other bacteria: Wen et al. (2007) reported that Pseudomonas putida DLL-1 exhibited metabolism-dependent chemotaxis toward methyl parathion; Burkholderia sp. strain SJ98 also demonstrated such chemotaxis toward several chloro-nitroaromatic compounds (Pandey et al. 2012); Pailan and Saha (2015) reported possible metabolism-dependent behavior of P. sp. strain BUR11 toward 4AP, parathion, and PNP. In contrast, when chemotaxis occurs independent of the metabolism of the chemo-attractant, it is called metabolism-independent chemotaxis. The latter phenomenon was reported by Arora et al. (2015); Rabinovitch-Deere and Parales (2012) when they were working with Bacillus subtilis PA-2 and Acidovorax sp. strain JS42, respectively. Chemotaxis provides an extra advantage for the xenobiotics-degrading bacterium, which can sense and locate the area within the ecosystem. Chemotaxis toward hazardous xenobiotic compounds and their mineralization indicate that chemotaxis and bioremediation are somehow linked (Pandey and Jain 2002). Thus, it may be summarized that the strain PNPG3 may be used as a model organism for the study of the molecular mechanism of biodegradation and chemotaxis toward xenobiotic compounds. A similar phenotypic-genotypic associative study was reported for another strain of P. asiatica strain JP233 by Wang et al. (2022).

Conclusion

The present manuscript elaborated that the Pseudomonas asiatica strain PNPG3 exhibited a variable degree of chemotactic potential toward three different xenobiotic toxic compounds, such as PNP, PBQ, and 4AP. A genome annotation study revealed that the strain harbored all the chemotactic machinery within its genome. The strain has thirteen Che genes, thirty-four flagellar proteins, twenty-two MCPs, and eight rotary motors that are involved in sensing chemoattractants. Moreover, conserved sequences of the chemotaxis genes were determined and domain organizations were determined by standard tools (freely available in public database). The current study indicated that Pseudomonas asiatica strain PNPG3 is a biotechnologically potential strain; it could be used for chemotaxis-mediated bioremediation (attempts in ex-situ study) of toxic PNP from aquatic ecosystems.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Department of Microbiology, The University of Burdwan, West Bengal, India for providing infrastructural support. AA is thankful to CSIR, Govt. of India (file no.- 09/025(0263)/2019) for the financial support (received during the initial phase of 1 year, from July 2018 to August 2019). AA is grateful to Dr. Santanu Pailan (Dept. of Biotechnology, The University of Burdwan), Dr. Urmimala Sen and Dr. Debdoot Gupta (Dept. of Microbiology, The University of Burdwan) for sharing scientific ideas related to experiment.

Author contributions

SAA isolated the strain, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures, and tables, performed bioinformatics analysis, and reviewed drafts of the paper. PS designed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials, and reviewed drafts of the paper.

Data availability

The dataset is publicly available under genome sequence accession number (of strain PNPG3)-JALLKV000000000.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest connected to the manuscript.

References

- Alam SA, Saha P. Biodegradation of p-nitrophenol by a member of the genus Brachybacterium, isolated from the river Ganges. 3 Biotech. 2022;12:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s13205-022-03263-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam SA, Saha P. Evidence of p-nitrophenol biodegradation and study of genomic attributes from a newly isolated aquatic bacterium Pseudomonas asiatica strain PNPG3. Soil Sediment Contam An Int J. 2022 doi: 10.1080/15320383.2022.2159321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alber T, Cassidy MB, Zablotowicz RM, Trevors JT, Lee H. Degradation of p-nitrophenol and pentachlorophenol mixtures by Sphingomonas sp. UG30 in soil perfusion bioreactors. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;25:93–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.7000040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arora PK, Bae H. Biotransformation and chemotaxis of 4-chloro-2-nitrophenol by Pseudomonas sp. JHN Microb Cell Factories. 2014;13:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12934-014-0110-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora PK, Jeong MJ, Bae H. Chemotaxis away from 4-chloro-2-nitrophenol, 4-nitrophenol, and 2, 6-dichloro-4-nitrophenol by Bacillus subtilis PA-2. J Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/296231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008;9:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berne C, Brun YV. The two chemotaxis clusters in Caulobacter crescentus play different roles in chemotaxis and biofilm regulation. J Bacteriol. 2019;201:00071–119. doi: 10.1128/JB.00071-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan B, Samanta SK, Chauhan A, Chakraborti AK, Jain RK. Chemotaxis and biodegradation of 3-methyl-4-nitrophenol by Ralstonia sp. SJ98. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;275:129–133. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner FR, Plunkett G, III, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, Gregor J, Davis NW, Kirkpatrick HA, Goeden MA, Rose DJ, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan A, Chakraborti AK, Jain RK. Plasmid-encoded degradation of p-nitrophenol and 4-nitrocatechol by Arthrobacter protophormiae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:733–740. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghirardelli A, Tarolli P, Rajasekaran MK, Mudbhatkal A, Macklin MG, Masin R. Organic contaminants in Ganga basin: from the green revolution to the emerging concerns of modern India. Iscience. 2021;24:102122. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordillo F, Chávez FP, Jerez CA. Motility and chemotaxis of Pseudomonas sp. B4 towards polychlorobiphenyls and chlorobenzoates. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2007;60:322–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood CS, Parales RE, Dispensa MARILYN. Chemotaxis of Pseudomonas putida toward chlorinated benzoates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1501–1503. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.5.1501-1503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim HM. Biodegradation of used engine oil by novel strains of Ochrobactrium anthropi HM-1 and Citrobacter freundii HM-2 isolated from oil-contaminated soil. 3 Biotech. 2016;6:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s13205-016-0540-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaki H, Muraki T, Ishihara S, Hasegawa Y, Rankin KN, Sulea T, Boyd J, Lau PC. Characterization of a pseudomonad 2-nitrobenzoate nitroreductase and its catabolic pathway-associated 2-hydroxylaminobenzoate mutase and a chemoreceptor involved in 2-nitrobenzoate chemotaxis. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:3502–3514. doi: 10.1128/jb.01098-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhariya DC and Tiwari AK (2020) December. Ganga River: A Paradox of Purity and Pollution in India due to Unethical Practice. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environ Sci 597: 012023). IOP Publishing. 10.1088/1755-1315/597/1/012023

- Krogh A, Larsson B, Von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Bio. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S, Le Q, Hu J, Wang Y, Yu N, Cao X, Zhang M, Sun Y, Gu W, Yang Y, Zhang Y. Effects of p-nitrophenol on enzyme activity, histology, and gene expression in Larimichthys crocea. Comp Biochem Physiol Part C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2020;228:108638. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2019.108638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni M, Chaudhari A. Biodegradation of p-nitrophenol by P. putida. Bioresour Technol. 2006;97:982–988. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni M, Chaudhari A. Efficient Pseudomonas putida for degradation of p-nitrophenol. Indian J Bacteriol. 2006;5:411–415. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.04.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Vikram S, Raghava GPS. Genome annotation of Burkholderia sp. SJ98 with special focus on chemotaxis genes. PloS One. 2013;8:70624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Copley RR, Pils B, Pinkert S, Schultz J, Bork P. SMART 5: domains in the context of genomes and networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:257–D260. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Romine MF, Ward MJ. Identification and analysis of a highly conserved chemotaxis gene cluster in Shewanella species. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;273:180–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min J, Wang J, Chen W, Hu X. Biodegradation of 2-chloro-4-nitrophenol via a hydroxyquinol pathway by a Gram-negative bacterium, Cupriavidus sp. strain CNP-8. AMB Express. 2018;8:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13568-018-0574-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni B, Huang Z, Fan Z, Jiang CY, Liu SJ. Comamonas testosteroni uses a chemoreceptor for tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates to trigger chemotactic responses towards aromatic compounds. Mol Microbiol. 2013;90:813–823. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen MB, Kjeldsen KU, Ingvorsen K. Description of Citricoccus nitrophenolicus sp. Nov., a para-nitrophenol degrading actinobacterium isolated from a wastewater treatment plant and emended description of the genus Citricoccus Altenburger et al. 2002. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2011;99:489–499. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9513-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurk S, Meleshko D, Korobeynikov A, Pevzner PA. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 2017;27:824–834. doi: 10.1101/gr.213959.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pailan S, Saha P. Chemotaxis and degradation of organophosphate compound by a novel moderately thermo-halo tolerant Pseudomonas sp. strain BUR11: evidence for possible existence of two pathways for degradation. PeerJ. 2015;3:1378. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakala SB, Gorla P, Pinjari AB, Krovidi RK, Baru R, Yanamandra M, Merrick M, Siddavattam D. Biodegradation of methyl parathion and p-nitrophenol: evidence for the presence of a p-nitrophenol 2-hydroxylase in a Gram-negative Serratia sp. strain DS001. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;73:1452–1462. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0595-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey G, Jain RK. Bacterial chemotaxis toward environmental pollutants: role in bioremediation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:5789–5795. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.12.5789-5795,2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey J, Sharma NK, Khan F, Ghosh A, Oakeshott JG, Jain RK, Pandey G. Chemotaxis of Burkholderia sp. strain SJ98 towards chloronitroaromatic compounds that it can metabolise. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira M, Rocha JAP, Bataus LAM, Cardoso DDDDP, Soares RDBA and Soares CMDA (2004) Chemotaxis and flagellar genes of Chromobacterium violaceum [PubMed]

- Porter SL, Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. Signal processing in complex chemotaxis pathways. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:153–165. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash D, Chauhan A, Jain RK. Plasmid-encoded degradation of p-nitrophenol by Pseudomonas cepacia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224:375–381. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X, Zhong Q, Li M, Bai W, Li B. Biodegradation of p-nitrophenol by methyl parathion-degrading Ochrobactrum sp. B2. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2007;59:297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2006.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovitch-Deere CA, Parales RE. Three types of taxis used in the response of Acidovorax sp. strain JS42 to 2-nitrotoluene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:2306–2315. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07183-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy M, Shamim F. Research on the impact of industrial pollution on river Ganga: a review. Int J Prev Control Indus Pollut. 2020;6:43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Samanta SK, Bhushan B, Chauhan A, Jain RK. Chemotaxis of a Ralstonia sp. SJ98 toward different nitroaromatic compounds and their degradation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;269:117–123. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson R, Bodade R, Zinjarde S, Kutty R. A novel Sphingobacterium sp. RB, a rhizosphere isolate degrading para-nitrophenol with substrate specificity towards nitrotoluenes and nitroanilines. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2019;366:168. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnz168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta K, Swain MT, Livingstone PG, Whitworth DE, Saha P. Genome sequencing and comparative transcriptomics provide a holistic view of 4-nitrophenol degradation and concurrent fatty acid catabolism by Rhodococcus sp. strain BUPNP1. Front Microbiol. 2019;9:3209. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethunathan N, Yoshida T. Parathion degradation of submerged rice soils in the Philippines. J Agric Food Chem. 1973;21:504–506. doi: 10.1021/jf60187a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolz BEAT, Berg HC. Evidence for interactions between MotA and MotB, torque-generating elements of the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7033–7037. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.7033-7037.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir U, Aslam F, Nawaz S, Khan UH, Yasmin A. Annotation of chemotaxis gene clusters and proteins involved in chemotaxis of Bacillus subtilis strain MB378 capable of biodecolorizing different dyes. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29:3510–3520. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-15634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusova T, DiCuccio M, Badretdin A, Chetvernin V, Nawrocki EP, Zaslavsky L, Lomsadze A, Pruitt KD, Borodovsky M, Ostell J. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:6614–6624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US-Environmental Protection Agency (US-EPA) (1980) Water quality criteria documents: availability. Environmental Protection Agency Fed. Reg. Washington, D.C. 45:79–318

- Wan N, Gu JD, Yan Y. Degradation of p-nitrophenol by Achromobacter xylosoxidans Ns isolated from wetland sediment. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2007;59:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2006.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhou F, Zhou J, Harvey PR, Yu H, Zhang G, Zhang X. Genomic analysis of Pseudomonas asiatica JP233: an efficient phosphate-solubilizing bacterium. Genes. 2022;13:2290. doi: 10.3390/bgenes13122290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattam AR, Abraham D, Dalay O, Disz TL, Driscoll T, Gabbard JL, Gillespie JJ, Gough R, Hix D, Kenyon R, Machi D. PATRIC, the bacterial bioinformatics database and analysis resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:581–D591. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Jiang JD, Deng HH, Lan H, Li SP. Effect of mutation of chemotaxis signal transduction gene cheA in Pseudomonas putida DLL-1 on its chemotaxis and methyl parathion biodegradation. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao Acta Microbiol Sinica. 2007;47:471–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is publicly available under genome sequence accession number (of strain PNPG3)-JALLKV000000000.