Abstract

Background

Many people with atopic eczema are reluctant to use the most commonly recommended treatments because they fear the long‐term health effects. As a result, many turn to dietary supplements as a possible treatment approach, often with the belief that some essential ingredient is 'missing' in their diet. Various supplements have been proposed, but it is unclear whether any of these interventions are effective.

Objectives

To evaluate dietary supplements for treating established atopic eczema/dermatitis.

Evening primrose oil, borage oil, and probiotics are covered in other Cochrane reviews.

Search methods

We searched the following databases up to July 2010: the Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE (from 2005), EMBASE (from 2007), PsycINFO (from 1806), AMED (from 1985), LILACS (from 1982), ISI Web of Science, GREAT (Global Resource of EczemA Trials) database, and reference lists of articles. We searched ongoing trials registers up to April 2011.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of dietary supplements for the treatment of those with established atopic eczema/dermatitis.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts, read the full text of the publications, extracted data, and assessed the risk of bias.

Main results

We included 11 studies with a total of 596 participants. Two studies assessed fish oil versus olive oil or corn oil placebo. The following were all looked at in single studies: oral zinc sulphate compared to placebo, selenium versus selenium plus vitamin E versus placebo, vitamin D versus placebo, vitamin D versus vitamin E versus vitamins D plus vitamin E together versus placebo, pyridoxine versus placebo, sea buckthorn seed oil versus sea buckthorn pulp oil versus placebo, hempseed oil versus placebo, sunflower oil (linoleic acid) versus fish oil versus placebo, and DHA versus control (saturated fatty acids of the same energy value). Two small studies on fish oil suggest a possible modest benefit, but many outcomes were explored. A convincingly positive result from a much larger study with a publicly‐registered protocol is needed before clinical practice can be influenced.

Authors' conclusions

There is no convincing evidence of the benefit of dietary supplements in eczema, and they cannot be recommended for the public or for clinical practice at present. Whilst some may argue that at least supplements do not do any harm, high doses of vitamin D may give rise to serious medical problems, and the cost of long‐term supplements may also mount up.

Keywords: Humans; Dietary Supplements; Dermatitis, Atopic; Dermatitis, Atopic/diet therapy; Fish Oils; Fish Oils/therapeutic use; Plant Oils; Plant Oils/therapeutic use; Pyridoxine; Pyridoxine/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Selenium; Selenium/therapeutic use; Vitamin D; Vitamin D/therapeutic use; Vitamin E; Vitamin E/therapeutic use; Vitamins; Vitamins/therapeutic use; Zinc; Zinc/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Dietary supplements for established atopic eczema in adults and children

Eczema is a skin condition characterised by an itchy, red rash, which affects 5% to 20% of people worldwide. There is no cure, but many treatments can help improve the skin's condition, making life easier. In those for whom these treatments do not work well or who fear their long‐term effects, there is often a belief that either something in their diet, or something missing in their diet, is making their eczema worse.

This review looked at the following dietary supplements (products which add ingredients to a diet): fish oil, zinc, selenium, vitamin D, vitamin E, pyridoxine (vitamin B6), sea buckthorn oil, hempseed oil, and sunflower oil.

Three commonly used dietary supplements (evening primrose oil, borage oil, and probiotics) are currently the subject of other Cochrane reviews (Boehm 2003; Boyle 2008).

We looked for trials comparing supplements with placebo (dummy). We included 11 randomised controlled trials (596 participants) when it was clear that the children or adults taking part had atopic eczema. In reviewing the trials, the main outcomes we looked for were evidence of improvement in the symptoms of eczema, such as itching or loss of sleep, in the short‐term (i.e. six weeks). In the longer term, we wanted to see evidence of a reduced need for treatment for the eczema or a reduction in the number of flares. We also looked for evidence of any general improvement in the eczema and in individual symptoms.

Overall, we found no convincing evidence that taking supplements improved the eczema of those involved. In general, studies were small with low numbers of participants and of poor quality in terms of the way they were run. Two trials of fish oil did find slight improvement for the participants in terms of the degree of itchiness and quality of life. However, these trials had small numbers, which means they had little chance of finding real differences if they did exist. That is why larger trials are needed before any recommendations can be made. We found no evidence of adverse (harmful) effects in those who took part in the trials. People sometimes think that supplements can at least do no harm; however, high doses of vitamin D, for example, can cause serious medical problems, and the safety of dietary supplements should not be assumed. The cost of supplements can also mount up.

Background

Description of the condition

Disease definition

Atopic eczema (AE) is a non‐infective, chronic inflammatory skin disease characterised by an itchy, red rash. The terms 'atopic eczema' and 'atopic dermatitis' have been used synonymously throughout this review.

The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) nomenclature task force has previously defined the term 'atopy' as a personal or familial tendency, or both, usually in childhood and adolescence, to become sensitised to an allergen and to produce IgE antibodies (Johansson 2001).

Up to 40% of children with atopic eczema are not atopic when defined according to allergy tests, such as skin prick tests (Bohme 2001). Others have found that up to two thirds of people with atopic dermatitis are not atopic (Flohr 2004), implying that the continued use of the term 'atopic dermatitis' is problematic. A revised nomenclature for allergy (Johansson 2001) has been updated by the World Allergy Organisation (Johansson 2004). The new nomenclature is based on the mechanisms that initiate and mediate allergic reactions. The term 'eczema' is proposed to replace the provisional term 'atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome' (AEDS). What is generally known as 'atopic eczema/dermatitis' is probably not one single disease, but rather an aggregation of several diseases with certain characteristics in common. The term 'atopy' cannot be used until an IgE sensitisation has been documented by IgE antibodies in the blood of a person or by a positive skin prick test to common environmental allergens, such as pollen or house dust mite. The term 'eczema' can, therefore, be split into 'atopic eczema' and 'non‐atopic eczema'.

Because most readers of this review will be used to the terms 'atopic eczema' or 'atopic dermatitis' when referring to these conditions, we will use the term 'atopic eczema' in a similar loose way throughout this review on the understanding that the use of the prefix 'atopic' does not imply IgE sensitivity. Where IgE sensitivity has been determined in the studies, we will highlight them accordingly.

Epidemiology and causes

Atopic eczema is the most common inflammatory skin disease of childhood, affecting 15% to 20% of children in the UK at any one time (Hoare 2000). The cumulative prevalence of atopic dermatitis varies from up to 20% in Northern Europe and the USA, to 5% in the South Eastern Mediterranean (Shaw 2011; Thestrup 2002). Prevalence data for the symptoms of atopic eczema were collected in the global ISAAC study (International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood). The results of this study suggest that atopic eczema is a worldwide problem affecting 5% to 20% of children (Odhiambo 2009; Williams 1999). Only 2% of children under the age of 5 years have severe disease, and 84% have mild disease (Emerson 1998). Around 2% of adults have atopic eczema, and many of these have a more chronic and severe form (Charman 2002). Atopic eczema is often associated with other atopic diseases (Beck 2000), e.g. asthma and rhinitis, and sufferers often have a family history of the condition. The incidence of common allergic disease has increased over the last 30 years (Asher 2006). The increase in prevalence of atopic disease in the past three decades appears to be a real phenomenon and has been observed in countries as far apart as Japan, USA, Finland, and Africa (Williams 2008).

The cause of eczema is not well‐understood, but it is probably due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors (Cookson 2002), such as pollution (Polosa 2001), and prenatal or early exposure to infections (Kalliomaki 2002). Research into filaggrin gene mutations has also highlighted the importance of a defective skin barrier as well as altered immune responses (van den Oord 2009).

Clinical features

Atopic eczema may be acute (short and severe) with redness, scaling, oozing, and vesicles; or it may be chronic (long‐term) with skin thickening, altered pigmentation, and exaggerated surface markings. The condition affects mainly the creases of the elbows and knees, and the face and neck, although it can affect any part of the body. The severity of eczema is variable, ranging from localised mild scaling to generalised involvement of the whole body, with redness, oozing, and secondary infection. Itching is the predominant symptom, which can induce a vicious cycle of scratching and, thus, skin damage that in turn leads to more itching ‐ the so‐called "itch scratch itch" cycle. There is a tendency to a dry, sensitive skin, even in those who have 'grown out' of the disease. This is thought to be due to a defect in the barrier of the epidermis (van den Oord 2009). In adulthood, the skin (especially of the hands) may be prone to inflammation in the presence of environmental irritants, such as soaps (Archer 2000).

Natural history

Atopic eczema usually starts within the first 6 months of life, and by 1 year, 60% of those likely to develop it will have done so. Remission occurs by the age of 15 years in 60% to 70% of cases, although some relapse later (Williams 2000). In the more severely affected child, development and puberty may be delayed (Baum 2002).

Impact

Atopic eczema varies in severity, often from one hour to the next. Severity can be measured in a number of ways. The itching and scratching can adversely affect quality of life through chronic sleep disturbance (Meltzer 2008). This may have an impact on family life. The disease can be associated with complications, such as bacterial and viral infections (McHenry 1995). The unsightly appearance of the skin and the need to apply greasy ointments can limit a child's inclination to participate in social and sporting activities and, thus, affect their confidence. Adults with atopic eczema often have low self‐esteem, and relationships can be difficult to initiate and sustain. Everyday tasks, such as housework, gardening, childcare, and food preparation, present problems when the skin on the hands is cracked. Promotion at work may be blocked for people who do not 'look good'.

There is a substantial economic cost not only to the family of the person with atopic eczema (Kemp 2003), but also to the health services of the country as a whole (Herd 1996; Mancini 2008; Verboom 2002). Direct costs to the family are encountered when purchasing treatments, special clothing, and bedding; indirect costs are experienced from lost working days when parents are looking after a sick child. The wider economic implications lie in the costs of healthcare professionals, the lost opportunities of parents of sick children who do not have the option of seeking employment, and the child who, as a result of missing schooling, has limited employment prospects (Su 1997).

Description of the intervention

There is currently no cure for atopic eczema. However, a wide range of treatments are employed that aim to control the symptoms (Fennessy 2000; Hoare 2000; Lamb 2002). Healthcare professionals assist people in the management of their disease using a variety of treatment methods; these include emollients, topical steroids, topical tars, topical tacrolimus, and pimecrolimus (NCC‐WCH & NICE 2007; SIGN 2011). Other treatment methods, such as wet wrap dressings, phototherapy, and complementary therapies (Ernst 2002), are also tried. Many of the treatments are of unknown effectiveness (Hoare 2000). Emollients and topical corticosteroids are universally recommended (Smethurst 2002). In addition, textile (soft clothes) and ambient (dust) measures of control for atopic eczema have been used.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) systematic review of treatments for atopic eczema (Hoare 2000) looked at trials that had been conducted on dietary interventions including borage oil, evening primrose oil, pyridoxine, vitamin, and zinc supplementation. This review suggested that there was no clear benefit over placebo with any of these interventions, although no formal meta‐analyses were performed, and the review is now out of date. We could not find any other systematic reviews on this topic.

Diet and atopic eczema

Many people with atopic eczema are reluctant to use the most commonly recommended treatments because they fear the long‐term health effects (Charman 2002). As a result, many turn to dietary supplementation as a possible treatment approach, often with the belief that some essential ingredient is 'missing' in the diet of the affected individual. In other cases, the rationale for use of the supplements may have a sound scientific basis as illustrated below.

A number of dietary supplements have been tried, and these can be broadly classified into the following.

(1) Vitamins, such as pyridoxine (vitamin B6)

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) is an essential water‐soluble vitamin and a co‐factor in many of the body's chemical pathways. It has been used to treat atopic eczema (Mabin 1995).

(2) Essential fatty acids, such as evening primrose oil (EPO)

Polyunsaturated fatty acids are essential components of all cell membranes. There are 2 families of such essential fatty acids: n‐6 (e.g. linoleic acid and arachidonic acid) and n‐3 (e.g. eicosapentaenoic acid). Some of these substances are precursors of a group of substances called eicosanoids, which may play an important part in the inflammatory and immunological processes of atopic eczema. Fish oils are particularly rich in n‐3 fatty acids, and it has been suggested that these may compete with n‐6 fatty acids in a way that reduces the inflammatory components of atopic eczema. EPO and borage oil are being covered in another Cochrane review currently in preparation (Boehm 2003).

(3) Minerals, such as zinc

Oral supplements of zinc salts have become popular remedies for a range of unrelated medical disorders (Pfeiffer 1978). They have been specifically recommended for the treatment of atopic eczema (Bland 1983; Davies 1987; Franklin 1988), although the scientific basis for this is unclear.

(4) 'Others', such as trace elements (e.g. selenium)

Reduced concentrations of selenium in whole blood, plasma, and white cells; and reduced activity of the selenium‐dependent enzyme, glutathione peroxidase, in red cells have been found in atopic eczema. This has lead to the use of supplements, such as selenium and vitamin E (Fairris 1989a).

(5) Probiotics (friendly gut bacteria)

Probiotics are a treatment that may alter the intestinal microbiota of people with eczema. Probiotics are live micro‐organisms (e.g. Lactobacillus species) that when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host. Their precise mode of action is not well‐established, but they have been shown to reduce markers of intestinal inflammation and intestinal permeability in disease states. This might change the way in which antigens that are present in the intestine are recognised by the immune system. Probiotics are dealt with in another Cochrane review (Boyle 2008).

Why it is important to do this review

The rationale for a review on dietary supplements for established atopic eczema is as follows:

(1) previous reviews, such as the UK Health Technology Assessment systematic reviews, are now at least 10 years out of date;

(2) there is a need to cover those dietary supplements that are not mentioned in the other Cochrane reviews of evening primrose oil or probiotics; and

(3) lots of dietary supplements are commonly tried in eczema.

Objectives

To evaluate dietary supplements for treating established atopic eczema/dermatitis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of dietary supplements for the treatment of established atopic eczema/dermatitis.

We excluded provocation studies, such as double‐blind food challenges that focused only on the diagnosis of food allergy. However, RCTs of therapeutic interventions that have used food challenges to identify suitable study participants were included.

Types of participants

We included those people who had atopic eczema as diagnosed by a doctor.

In the HTA systematic review of treatments for atopic eczema (Hoare 2000), specific terms were used to identify trial participants as listed in Table 1. The list classifies conditions into 'definite', 'possible', and 'not' atopic eczema ‐ we used this list as a guide.

1. Terms used to categorise trial participants with atopic eczema (AE).

| Definite AE | Possible AE | Not AE |

| Atopic eczema | Periorbital eczema | Seborrhoeic eczema |

| Atopic dermatitis | Childhood eczema | Contact eczema |

| Besnier's prurigo | Infantile eczema | Allergic contact eczema |

| Neurodermatitis atopica (German) | 'Eczema' unspecified | Irritant contact eczema |

| Flexural eczema/dermatitis | Constitutional eczema | Discoid/ nummular eczema |

| ‐ | Endogenous eczema | Asteatotic eczema |

| ‐ | Chronic eczema | Varicose/stasis eczema |

| ‐ | Neurodermatitis | Photo‐/light‐sensitive eczema |

| ‐ | Neurodermatitis (German) | Chronic actinic dermatitis |

| ‐ | ‐ | Dishydrotic eczema |

| ‐ | ‐ | Pompholyx eczema |

| ‐ | ‐ | Hand eczema |

| ‐ | ‐ | Frictional lichenoid dermatitis |

| ‐ | ‐ | Lichen simplex |

| ‐ | ‐ | Occupational dermatitis |

| ‐ | ‐ | Prurigo |

Those studies using terms in the 'not atopic eczema' category, such as 'allergic contact eczema', were excluded. Those studies using terms in the 'possible atopic eczema' category, such as 'childhood eczema', were scrutinised by one or more authors and only included if the description of the participants clearly indicated atopic eczema (i.e. itching and flexural involvement).

Types of interventions

Dietary supplements, such as vegetable and fish oils, vitamins, selenium, and zinc. The comparators are no treatment, placebo, or any other active intervention.

Evening primrose oil (EPO) and borage oil are excluded in this review as they are being covered in a separate Cochrane Review (Boehm 2003), and the protocol has been published in The Cochrane Library. Probiotics have been covered in a separate Cochrane review (Boyle 2008).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

(a) Short‐term (within six weeks). Changes in participant‐rated or parent‐rated symptoms of atopic eczema, such as pruritus (itching) or sleep loss. (b) Degree of long‐term (over six months) control, such as reduction in number of flares or reduced need for other treatments.

Secondary outcomes

(a) Global severity as rated by the participants or their physician. If this outcome was not available then the following was used: (b) Global changes in composite rating scales using a published named scale. Where this was not possible, we used the following: (c) The author's modification of existing scales or new scales. Also: (d) Quality of life (Chren 1997; Finlay 1996). (e) Palatability. (f) Adverse events including long‐term consequences on growth.

Tertiary outcome measures

Changes in individual signs of atopic eczema as assessed by a physician, e.g. erythema (redness), purulence (pus formation), excoriation (scratch marks), xerosis (skin dryness), lichenification (thickening of the skin), fissuring (cracks), exudation (weeping serum from the skin surface), pustules (pus spots), papules (spots that protrude from the skin surface), vesicles (clear fluid or 'water blisters' in the skin), crusts (dried serum on skin surface), infiltration/oedema (swelling of the skin), and induration (a thickened feel to the skin).

Search methods for identification of studies

We aimed to identify all relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases up to 8th July 2010:

the Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register using the search strategy in Appendix 1;

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library using the search strategy in Appendix 2;

MEDLINE (from 2005) using the search strategy in Appendix 3;

EMBASE (from 2007) using the search strategy in Appendix 4;

PsycInfo (from 1806) using the search strategy in Appendix 3;

AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine, from 1985) using the search strategy in Appendix 3;

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Literature Information database, from 1982) using the search strategy in Appendix 5;

ISI Web of Science (which contains the Science Citation Index); and

The GREAT (Global Resource for EczemA Trials) database.

The UK and US Cochrane Centres (CCs) have ongoing projects to systematically search MEDLINE and EMBASE for reports of trials, which are then included in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. Searching has currently been completed in MEDLINE to 2004 and in EMBASE to 2006. Further searching has been undertaken for this review by the Cochrane Skin Group to cover the years that have not been searched by the UK and US CCs.

A final prepublication search for this review was undertaken on 14th September 2011. Although it has not been possible to incorporate RCTs identified through this search within this review, relevant references are listed under Studies awaiting classification. They will be incorporated into the next update of the review.

Ongoing Trials

We searched the following ongoing trials registries on 14th April 2011, using the following search terms: 'atopic eczema', 'atopic dermatitis', 'supplements', 'vitamins', 'zinc', 'essential fatty acids', and 'selenium'.

The metaRegister of Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com).

The US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

The Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au).

The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry platform (www.who.int/trialsearch).

The Ongoing Skin Trials Register (www.nottingham.ac.uk/ongoingskintrials).

Searching other resources

Reference from published studies

The bibliographies of included and excluded RCTs were checked for possible references to further RCTs.

Language

No language restrictions were imposed.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (FB‐H and CJ) identified titles and abstracts from the searches. If it was clear that the study did not refer to a randomised controlled trial of a supplement for the treatment of established atopic eczema then it was excluded. The same two authors independently assessed each study to determine whether it met the pre‐defined selection criteria. Any differences were resolved through discussion with a third author (HW).

Data extraction and management

Two authors (FB‐H and CJ) independently performed data extraction using a specially designed data extraction form. Any differences in opinion were resolved by a third author (HW). One author (FB‐H) checked and entered the data into RevMan 5.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The 'Risk of bias' assessment included an evaluation of the following components for each included study, since there is some evidence that these are associated with biased estimates of treatment effect (Juni 2001):

(a) the method of generation of the randomisation sequence; (b) the method of allocation concealment ‐ it was considered 'adequate' if the assignment could not be foreseen; (c) who was blinded/not blinded (participants, clinicians, outcome assessors) if this was appropriate; and (d) how many participants were lost to follow up in each treatment group, whether reasons for losses were adequately reported, and whether all participants were analysed in the groups to which they were originally randomised.

In addition, we have reported on the following:

(e) the degree of certainty that the participants had atopic eczema; (f) the baseline comparability of the participants for age, sex, and eczema severity; and (g) assessment of compliance with treatment.

To avoid investigator bias or error, two authors (FB‐H and CJ) independently examined all papers.

Measures of treatment effect

The results are expressed as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes, and difference in means (MD) with 95% CI for continuous outcomes. Where it was not possible to perform a meta‐analysis, the data has been summarised narratively.

Unit of analysis issues

We found one cross‐over study. We would have analysed data from the first phase of this cross‐over study separately before pooling, especially since cross‐over studies may not be appropriate for dietary supplements. However, this study gave no figures, and, therefore, it is described narratively.

Dealing with missing data

If participant dropout led to missing data, we conducted an intention‐to‐treat analysis. For dichotomous outcomes, participants with missing outcome data were regarded as treatment failures and included in the analysis. For continuous outcomes, we would have considered using the last recorded value carried forward of participants with missing outcome data; however, these circumstances did not occur.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic. Data were synthesised using meta‐analysis techniques if the I² statistic was less than 80%.

Assessment of reporting biases

We had planned to test publication bias by the use of a funnel plot if adequate data had been available for similar types of intervention.

Data synthesis

For studies with a similar type of active intervention, a meta‐analysis was performed to calculate a weighted treatment effect across trials using a fixed‐effect (DerSimonian and Laird) model. Where it was not possible to perform a meta‐analysis, the data were summarised for each trial.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Only two studies were pooled statistically.

If substantial heterogeneity (I² statistic > 50%) had existed between studies for the primary outcome, we would have investigated reasons for heterogeneity.

Had there been adequate information, we would have performed a subgroup analysis for infants (under 1 year old) and children (aged 1 to 16 years) versus adults.

Where participant‐rated symptoms were reported on categorical Likert scales (e.g. no improvement, mild improvement, good improvement, excellent), we dichotomised the data by defining a cut‐off at 'good to excellent improvement'.

Had enough studies used SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis), we would have split eczema severity into mild, moderate, and severe (where mild is 0 to 15, moderate is 15 to 40, and severe is > 40).

Other

Where there was uncertainty, we planned to contact trial authors for clarification. However, no clarification was needed from the trial authors. A consumer was part of the review team to ensure the relevance and readability of the final review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The electronic searches identified a total of 120 studies, of which the full text was sought for 18 studies. After reading the full text, 11 studies were included, 6 were excluded, and 1 was found to be an ongoing study.

Included studies

Eleven RCTs were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review (Bjorneboe 1989; Callaway 2005; Ewing 1991; Fairris 1989; Gimenez‐Arnau 1997; Javanbakht 2011; Koch 2008; Mabin 1995; Sidbury 2008; Soyland 1994; Yang 1999). A total of 596 participants were included in these studies, details of which are listed in the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables. The studies, which allowed participants to continue with what they were prescribed to mimic what would normally happen in practice, fell into the following main categories:

1. Fish oil 2. Zinc 3. Selenium 4. Vitamin D and vitamin E 5. Pyridoxine hydrochloride 6. Sea buckthorn oil 7. Hempseed oil 8. Sunflower oil 9. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplementation

Design

1. Fish oil We found three RCTs ‐ two were a two‐arm parallel group design (Bjorneboe 1989; Soyland 1994), and one was a three‐arm parallel group design (Gimenez‐Arnau 1997):

fish oil versus placebo (olive oil)

fish oil versus placebo (corn oil)

linoleic acid (from sunflower oil) versus fish oil versus placebo

2. Zinc We found one RCT, and it was a two‐arm parallel group design (Ewing 1991):

zinc versus placebo capsules

3. Selenium We found one RCT, and it was a three‐arm parallel group design (Fairris 1989):

selenium versus selenium plus vitamin E versus placebo

4. Vitamin D and E We found two RCTs ‐ one was a two‐arm parallel group design (Sidbury 2008), and the other was a four‐arm parallel group design (Javanbakht 2011):

vitamin D versus placebo

vitamin D plus vitamin E placebo versus vitamin E plus vitamin D placebo versus vitamins D plus vitamin E versus vitamin D and E placebos

5. Pyridoxine hydrochloride We found one RCT, and it was a two‐arm parallel group design (Mabin 1995):

pyridoxine hydrochloride versus placebo

6. Sea buckthorn oil We found one RCT, and it was a three‐arm parallel group design (Yang 1999):

sea buckthorn seed oil versus sea buckthorn pulp oil versus placebo

7. Hempseed oil We found one RCT, and it was a cross‐over study (Callaway 2005):

hempseed oil versus placebo (olive oil)

8. Sunflower oil We found one RCT, and it was a three‐arm parallel group design (Gimenez‐Arnau 1997):

linoleic acid (from sunflower oil) versus fish oil versus placebo

9. DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) We found one RCT, and it was a two‐arm parallel group design (Koch 2008):

DHA versus isoenergetic (equal energy content) control of saturated fatty acids

Sample Sizes

The number of participants in the studies ranged from 20 (Sidbury 2008) to 145 (Soyland 1994).

Setting

The studies were conducted in Norway (Bjorneboe 1989; Soyland 1994), Finland (Callaway 2005; Yang 1999), the UK (Ewing 1991; Fairris 1989; Mabin 1995), Spain (Gimenez‐Arnau 1997), Iran (Javanbakht 2011), Germany (Koch 2008), and the USA (Sidbury 2008).

Excluded studies

Six studies were excluded after reading the full text; the reasons for exclusion are listed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables.

Studies awaiting classification

One study (Bautista 2010) was identified when the prepublication search was conducted. Details of this are listed in a 'Characteristics of studies awaiting classification' table.

Ongoing studies

One ongoing study was identified (NCT00879424); details of this study are listed in a 'Characteristics of ongoing studies' table.

Risk of bias in included studies

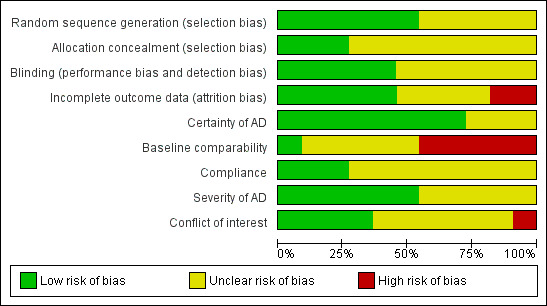

The methodological quality graph, Figure 1, shows the review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all of the included studies.

1.

Methodological quality graph: Review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

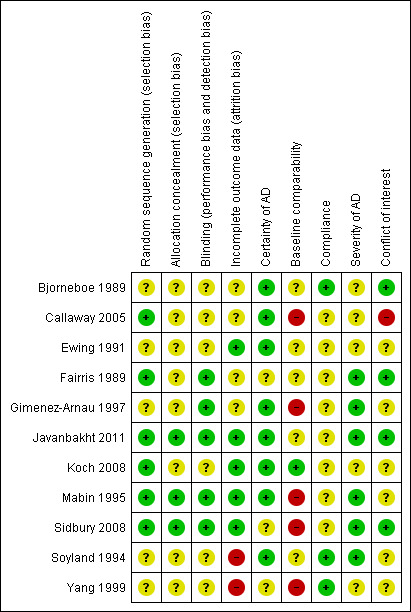

The methodological quality summary, Figure 2, shows the review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

2.

Methodological quality summary: Review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

In five studies the method of randomisation was not described or was unclear. Six studies clearly described the method of randomisation (Callaway 2005; Fairris 1989; Javanbakht 2011; Koch 2008; Mabin 1995; Sidbury 2008).

Only three studies clearly demonstrated adequate concealment of allocation (Javanbakht 2011; Mabin 1995; Sidbury 2008).

Blinding

One study blinded participants and the outcome assessor (Sidbury 2008). One study blinded participants and clinicians (Javanbakht 2011). One study blinded the participants only (Fairris 1989). Two studies blinded the outcome assessor only (Gimenez‐Arnau 1997; Mabin 1995). These studies were judged at low risk of bias for this domain.

Blinding was unclear in six studies.

Incomplete outcome data

Analysis should be performed according to the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) principle, thus, avoiding bias (Altman 1991; Sackett 1979). However, in many of the studies, analysis of outcomes was carried out only in those participants who completed the study.

Only one small study (n = 11) had no loss to follow up and analysed by intention‐to‐treat (Sidbury 2008). This study was judged at low risk of bias, as were four other studies that stated numbers and reasons for participants lost to follow up (Ewing 1991; Javanbakht 2011; Koch 2008; Mabin 1995).

One study (Fairris 1989) only gave the total number of participants, and it was not clear how many were evaluable in each arm. There was also no mention of ITT. One study (Gimenez‐Arnau 1997) did not mention loss to follow up, possibly due to a highly‐selected population. It was not clear if the analysis was by ITT. These two studies were judged as an unclear risk of bias, as were two other studies that mentioned dropouts, but carried out a per‐protocol (PP) analysis (Bjorneboe 1989; Callaway 2005).

Two studies were judged at high risk of bias for this domain. For the first study (Soyland 1994), 25 participants did not complete the study with no reasons given. In the second study (Yang 1999), 37% of the participants were lost to follow up and a PP analysis was undertaken.

Other potential sources of bias

Degree of certainty that participants had atopic eczema (AE)

The certainty of AE was clear for eight studies that used criteria by Hanifin and/or Rajka. Three studies did not state how they diagnosed atopic eczema (Fairris 1989; Sidbury 2008; Yang 2000).

Baseline comparability of the participants for age, sex, and eczema severity

Only one study (Koch 2008) clearly described baseline comparability and was judged at low risk of bias for this domain.

One study only gave baseline comparability for disease severity (Fairris 1989), so it was judged as unclear.

Four studies (Bjorneboe 1989; Ewing 1991; Javanbakht 2011; Soyland 1994) only gave baseline comparability for participants completing the supplementation, so they were judged as unclear.

Three studies gave no baseline comparability of participants (Callaway 2005; Gimenez‐Arnau 1997; Yang 1999), so they were judged at high risk of bias. The study by Sidbury 2008 gave no details of baseline comparability, and Mabin 1995 mentioned that it had large differences in sex distribution at baseline, so these two studies were judged at high risk of bias.

Assessment of compliance

Compliance was clear in only three studies (Bjorneboe 1989; Soyland 1994; Yang 1999).

Severity of atopic eczema

Severity of atopic eczema was clear for six studies (Fairris 1989; Gimenez‐Arnau 1997; Javanbakht 2011; Mabin 1995; Sidbury 2008; Soyland 1994).

Scales

The rationale for scale development, such as that used in the Fairris study in eczema, is very subjective, despite sounding very quantitative. It is probably not appropriate to use such ordinal data in a quantitative way as several of the studies have done. Furthermore, few of the scales used have been tested adequately for validity, repeatability, and responsiveness to change (Schmitt 2007).

Conflict of interest

Conflict of interest was high for only one study (Callaway 2005), low for four studies (Bjorneboe 1989; Fairris 1989; Javanbakht 2011; Sidbury 2008), and unclear for six studies (Ewing 1991; Gimenez‐Arnau 1997; Koch 2008; Mabin 1995; Soyland 1994; Yang 1999).

Effects of interventions

In this section we have addressed our prespecified outcome measures (Types of outcome measures) in relation to the intervention types we listed in the Included studies section.

1. Fish oil

Two studies were in adults with moderate/severe atopic eczema (Bjorneboe 1989; Soyland 1994). A third study was in adults with severe atopic eczema (Gimenez‐Arnau 1997). Two of these studies were considered sufficiently similar to pool for individual signs of AE (Bjorneboe 1989; Soyland 1994).

The first study (Bjorneboe 1989) was a parallel study of 31 adults (16 to 56 years) over a 12‐week period, which compared extract of fish oil (each capsule also contained an antioxidant, vitamin A, and vitamin D) to an isoenergetic (same energy value) placebo supplement containing olive oil. The main outcomes, which were symptom scores evaluated by the physician, were erythema, scale, visibility, severity, excoriation, weeping, lichenification, and the area affected. Symptom scores evaluated by participants were erythema, visibility, itch, scale, and effect on daily living.

The second study (Soyland 1994) was a parallel study of 145 adults (18 to 64 years) comparing fish oil (each capsule also contained an antioxidant) to a placebo (corn oil). The main outcomes, which were total symptom scores as rated by physicians and participants at 16 weeks, were effects of daily life as rated by the participants, and changes in individual signs of AE as assessed by a physician.

With regard to our primary outcome (a) 'Short‐term (within six weeks). Changes in participant‐rated or parent‐rated symptoms of atopic eczema, such as itching (pruritus) or sleep loss', no data were available for either study.

With regard to our primary outcome (b) 'Degree of long‐term (over six months) control, such as reduction in number of flares or reduced need for other treatments', there was no significant difference in topical steroid use for the Bjorneboe 1989 study. Only the mean and ranges were given: fish group, 95.8 g (40 to 250 g); and placebo, 77.7 g (10 to 200 g). In the Soyland 1994 study, there was no significant difference in antihistamine or mild topical steroid use ‐ this was only mentioned in the text.

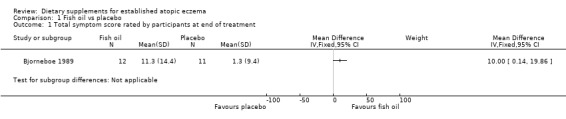

With regard to our secondary outcome (a) 'Global severity as rated by the participants or their physician', analysis of total symptom score as rated by the participant in the first study (Bjorneboe 1989) showed significantly higher overall improvement in the fish oil group, compared to the control group (one study; MD 10.00, 95% CI 0.14 to 19.86) (see Analysis 1.1). Analysis of total symptom score as rated by the physician showed no significant difference in overall improvement when fish oil was compared to placebo. No figures were given for this.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fish oil vs placebo, Outcome 1 Total symptom score rated by participants at end of treatment.

In the Soyland 1994 study, the total symptom scores rated by the physician and the participant after treatment significantly improved in both groups; no figures were given for the difference between groups ‐ only mean values were given per group with no standard deviations (fish group, 3.1; and placebo, 3.2).

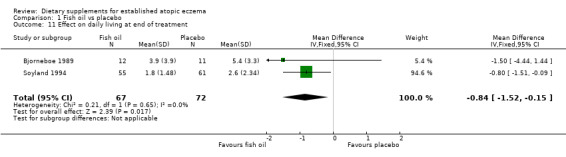

With regard to our secondary outcome (d) 'Quality of life', there was a significant difference in effect of daily living as evaluated by participants at the end of treatment in favour of fish oil (treatment group), compared to placebo (pooled analysis; 2 studies; MD ‐0.84, 95% CI ‐1.52 to ‐0.15) (see Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fish oil vs placebo, Outcome 11 Effect on daily living at end of treatment.

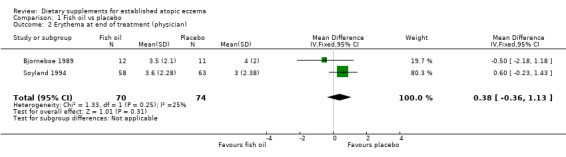

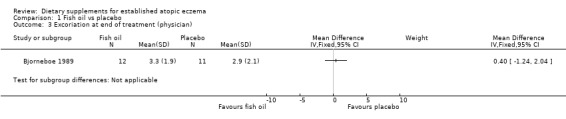

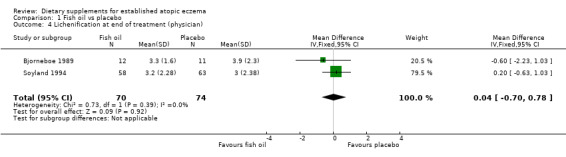

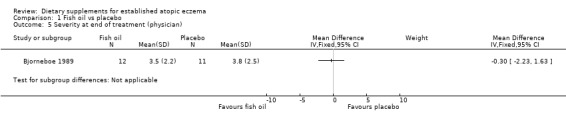

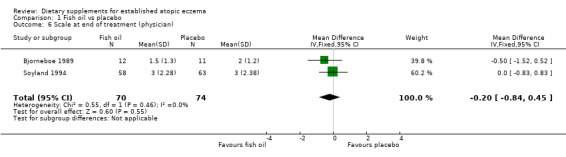

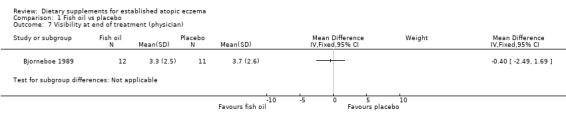

With regard to our tertiary outcome measure 'Changes in individual signs of atopic eczema as assessed by a physician', no significant difference was found for erythema (pooled analysis; 2 studies; MD 0.38, 95% CI ‐0.36 to 1.13) (see Analysis 1.2), excoriation (1 study; MD 0.40, 95% CI ‐1.24 to 2.04) (see Analysis 1.3), lichenification (pooled analysis; 2 studies; MD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.70 to 0.78) (see Analysis 1.4), severity (1 study; MD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐2.23 to 1.63) (see Analysis 1.5), scale (2 studies; MD ‐0.2, 95% CI ‐0.84 to 0.45) (see Analysis 1.6), and visibility (1 study; MD ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐2.49 to 1.69) (see Analysis 1.7).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fish oil vs placebo, Outcome 2 Erythema at end of treatment (physician).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fish oil vs placebo, Outcome 3 Excoriation at end of treatment (physician).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fish oil vs placebo, Outcome 4 Lichenification at end of treatment (physician).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fish oil vs placebo, Outcome 5 Severity at end of treatment (physician).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fish oil vs placebo, Outcome 6 Scale at end of treatment (physician).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fish oil vs placebo, Outcome 7 Visibility at end of treatment (physician).

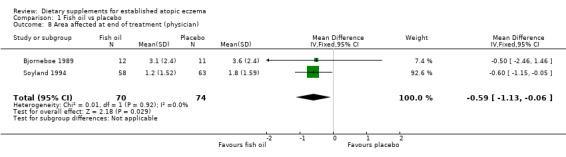

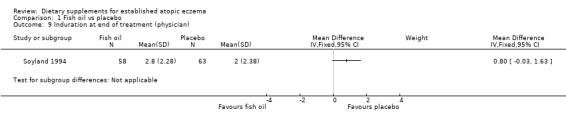

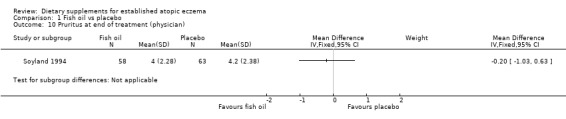

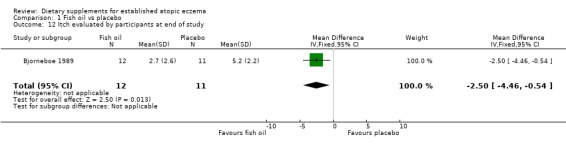

There was a significant difference in the area affected (pooled analysis; 2 studies; MD ‐0.59, 95% CI ‐1.13 to ‐0.06) (see Analysis 1.8) in favour of fish oil. No significant difference was found for induration (1 study; MD 0.8, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 1.63) (see Analysis 1.9) or pruritus (1 study; MD ‐0.2, 95% CI ‐1.03 to 0.63) (see Analysis 1.10). Results for itch at the end of treatment, as rated by the participant, significantly favoured the fish oil group (1 study; MD ‐2.50, 95% CI ‐4.46 to ‐0.54) (see Analysis 1.12).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fish oil vs placebo, Outcome 8 Area affected at end of treatment (physician).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fish oil vs placebo, Outcome 9 Induration at end of treatment (physician).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fish oil vs placebo, Outcome 10 Pruritus at end of treatment (physician).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Fish oil vs placebo, Outcome 12 Itch evaluated by participants at end of study.

Our secondary outcomes (b), (c), (e), and (f) were not addressed by Bjorneboe 1989 or Soyland 1994.

The third study (Gimenez‐Arnau 1997) was a three‐armed parallel study of 48 adults, which compared linoleic acid (from sunflower) versus fish oil versus placebo (oleic acid). The main outcomes were disease severity assessed by the Rajka score and eczema extension assessed by the Rule of Nines. Only six‐week data were given for all three groups due to a high dropout rate in the vegetable oil and placebo group. No numbers were given per arm.

With regard to our primary outcome (a) 'Short‐term (within six weeks). Changes in participant‐rated or parent‐rated symptoms of atopic eczema', such as itching (pruritus) or sleep loss', no data were given for short‐term changes in participant‐rated or parent‐rated symptoms.

With regard to our secondary outcome (b) 'Global changes in composite rating scales using a published named scale', significant differences were reported in the text of Gimenez‐Arnau 1997 in the percentage of Rajka score and Rule of Nine reduction between participants treated with linoleic acid and fish oil, and also between linoleic acid and placebo (oleic acid).

There were no data given for our prespecified tertiary outcome measures in the study by Gimenez‐Arnau 1997.

Neither our primary outcome (b), nor our secondary outcomes (a), (c), (d), (e), and (f), were addressed by Gimenez‐Arnau 1997.

2. Zinc

One parallel study (Ewing 1991) of 50 children (1 to 16 years) compared zinc sulphate versus placebo over 8 weeks. The main outcomes were extent of eczema estimated from percentage surface area of body affected by eczema, severity graded by degree of erythema on an arbitrary scale from one to five, and the surface area affected when multiplied by severity score, which was expressed as a combined disease severity score.

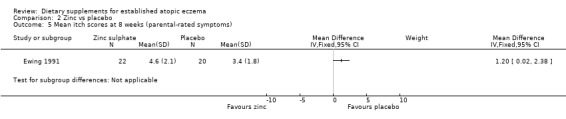

With regard to our primary outcome (a) 'Short‐term (within six weeks). Changes in participant‐rated or parent‐rated symptoms of atopic eczema, such as itching (pruritus) or sleep loss', there was no significant difference in mean itch score at four weeks (no figures given). However, the mean itch score was significantly higher in the zinc group at 8 weeks (MD 1.20, 95% CI 0.02 to 2.38) (see Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Zinc vs placebo, Outcome 5 Mean itch scores at 8 weeks (parental‐rated symptoms).

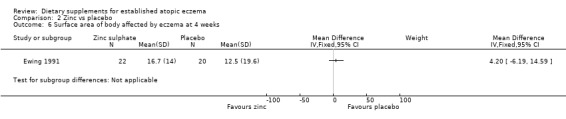

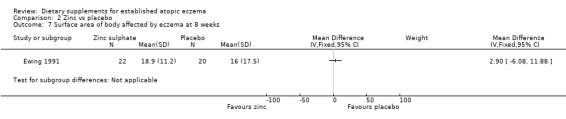

With regard to our secondary outcome (b) 'Global changes in composite rating scales using a published named scale', there was no significant difference in surface area of body affected by eczema at 4 weeks (MD 4.20, 95% CI ‐6.19 to 14.59) (see Analysis 2.6) or 8 weeks (MD 2.90, 95% CI ‐6.08 to 11.88) (see Analysis 2.7).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Zinc vs placebo, Outcome 6 Surface area of body affected by eczema at 4 weeks.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Zinc vs placebo, Outcome 7 Surface area of body affected by eczema at 8 weeks.

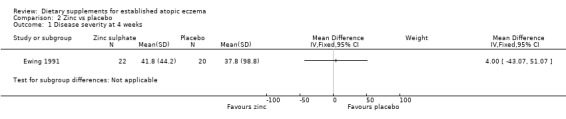

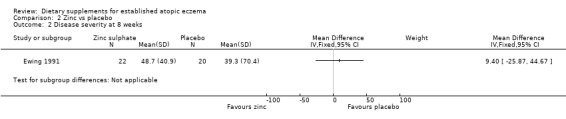

With regard to our secondary outcome (c) 'The author's modification of existing scales or new scales', there was no significant difference in combined disease severity score at 4 weeks (MD 4.00, 95% CI ‐43.07 to 51.07) (see Analysis 2.1) or 8 weeks (MD 9.40, 95% CI ‐25.87 to 44.67) (see Analysis 2.2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Zinc vs placebo, Outcome 1 Disease severity at 4 weeks.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Zinc vs placebo, Outcome 2 Disease severity at 8 weeks.

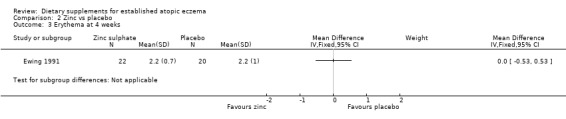

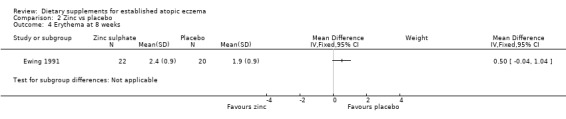

With regard to our tertiary outcome measure 'Changes in individual signs of atopic eczema as assessed by a physician, e.g. erythema (redness)', there was no significant difference in erythema as assessed by the physician at 4 weeks (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.53 to 0.53) (see Analysis 2.3) or 8 weeks (MD 0.50, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 1.04) (see Analysis 2.4).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Zinc vs placebo, Outcome 3 Erythema at 4 weeks.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Zinc vs placebo, Outcome 4 Erythema at 8 weeks.

Our primary outcomes (b) and (c); and our secondary outcomes (a), (b), (d), (e), and (f) were not addressed by Ewing 1991.

3. Selenium

One 3‐arm parallel group design study (Fairris 1989) of 60 adults compared selenium versus selenium plus vitamin E versus placebo over 12 weeks. The main outcomes were disease severity by separate assessment of the head plus neck, arms, trunk plus legs; and the degree of inflammation, lichenification, and scaliness on a scale of zero to four, adding the three values and multiplying them to give a weighted total score.

There were no data available for any of our prespecified primary and tertiary outcomes. None of our secondary outcomes were addressed apart from (a).

For our secondary outcome (a) 'Global severity as rated by the participants or their physician', there were no significant differences between mean severity score in the 3 groups at 12 weeks ‐ only means given with no standard deviations or number of participants per arm (selenium, 13.7; selenium plus vitamin E, 15.3; and placebo, 14.5).

4. Vitamin D and vitamin E

Two RCTs studied vitamin D and vitamin E: one four‐arm parallel group design (Javanbakht 2011) and one two‐arm parallel group design (Sidbury 2008).

The first study (Javanbakht 2011) was a 4‐arm parallel group design of 52 adults (13 to 45 years), which compared vitamin D plus vitamin E placebo versus vitamin E plus vitamin D placebo versus vitamins D plus vitamin E versus vitamin D and E placebos over 60 days. The main outcomes were severity of eczema using SCORAD.

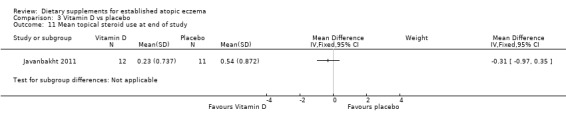

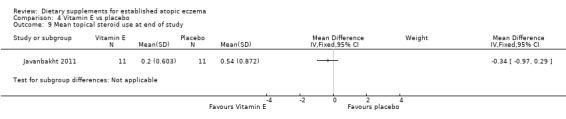

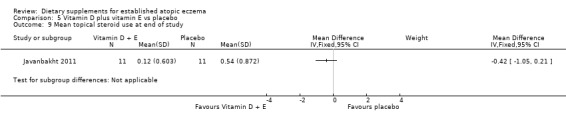

With regard to our primary outcome (b) 'Degree of long‐term (over six months) control, such as reduction in number of flares or reduced need for other treatments', there was no significant difference in the use of topical steroids for vitamin D (MD ‐0.31, 95% CI ‐0.97 to 0.35) (see Analysis 3.11), vitamin E (MD ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐0.97 to 0.29) (see Analysis 4.9), or vitamin D plus E (MD ‐0.42, 95% CI ‐1.05 to 0.21) (see Analysis 5.9) when compared to placebo.

3.11. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vitamin D vs placebo, Outcome 11 Mean topical steroid use at end of study.

4.9. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 9 Mean topical steroid use at end of study.

5.9. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vitamin D plus vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 9 Mean topical steroid use at end of study.

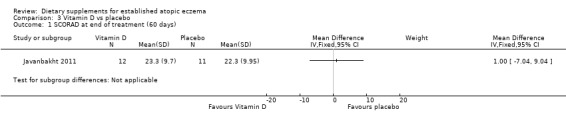

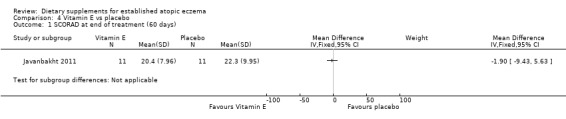

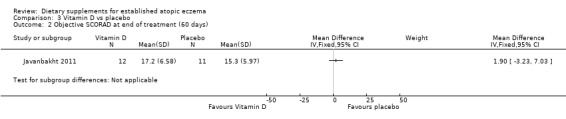

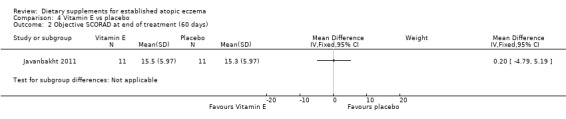

With regard to our secondary outcome (b) 'Global changes in composite rating scales using a published named scale', there was no significant difference in SCORAD at the end of treatment when vitamin D was compared to placebo (MD 1.00, 95% CI ‐7.04 to 9.04) (see Analysis 3.1), or when vitamin E was compared to placebo (MD ‐1.90, 95% CI ‐9.43 to 5.63) (see Analysis 4.1). There was no significant difference in objective SCORAD at the end of treatment when vitamin D was compared to placebo (MD 1.90, 95% CI ‐3.23 to 7.03) (see Analysis 3.2), or when vitamin E was compared to placebo (MD 0.20, 95% CI ‐4.79 to 5.19) (see Analysis 4.2).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vitamin D vs placebo, Outcome 1 SCORAD at end of treatment (60 days).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 1 SCORAD at end of treatment (60 days).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vitamin D vs placebo, Outcome 2 Objective SCORAD at end of treatment (60 days).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 2 Objective SCORAD at end of treatment (60 days).

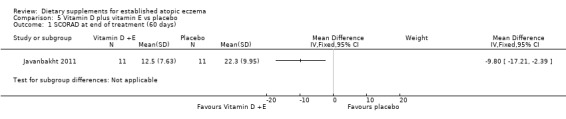

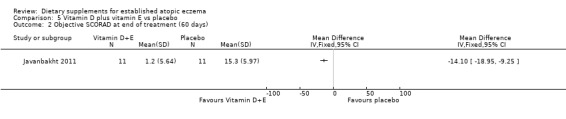

However, there was a significant difference in favour of vitamin D plus E compared to placebo for SCORAD at the end of treatment (MD ‐9.8, 95% CI ‐17.21 to ‐2.39) (see Analysis 5.1) and objective SCORAD at the end of treatment (MD ‐14.10, 95% CI ‐18.95 to ‐9.25) (see Analysis 5.2).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vitamin D plus vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 1 SCORAD at end of treatment (60 days).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vitamin D plus vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 2 Objective SCORAD at end of treatment (60 days).

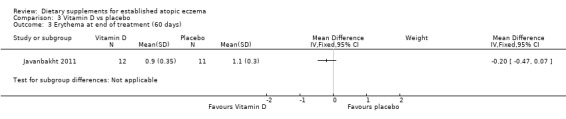

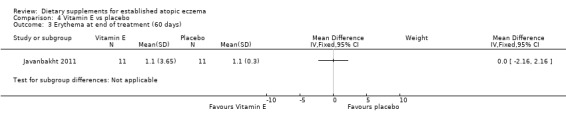

With regard to our tertiary outcome measure 'Changes in individual signs of atopic eczema as assessed by a physician', there were no significant differences in erythema as assessed by the clinician at the end of treatment for vitamin D versus placebo (MD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.47 to 0.07) (see Analysis 3.3), or vitamin E versus placebo (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐2.16 to 2.16) (see Analysis 4.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vitamin D vs placebo, Outcome 3 Erythema at end of treatment (60 days).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 3 Erythema at end of treatment (60 days).

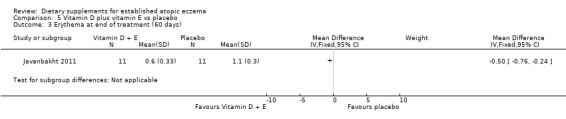

There was a significant difference in erythema for vitamin D plus E versus placebo (MD ‐0.5, 95% CI ‐0.76 to ‐0.24) (see Analysis 5.3).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vitamin D plus vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 3 Erythema at end of treatment (60 days).

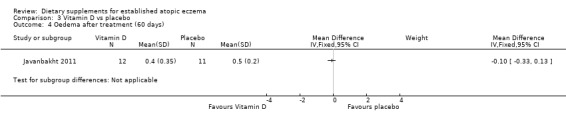

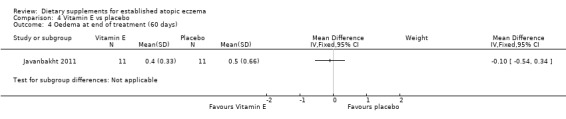

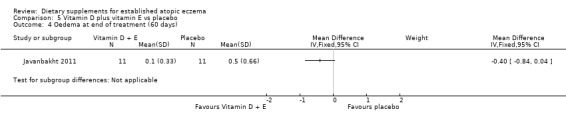

There was no significant difference in oedema as assessed by the clinician at the end of treatment for vitamin D versus placebo (MD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.33 to 0.13) (see Analysis 3.4), vitamin E versus placebo (MD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.54 to 0.34) (see Analysis 4.4), or vitamin D plus E versus placebo (MD ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐0.84 to 0.04) (see Analysis 5.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vitamin D vs placebo, Outcome 4 Oedema after treatment (60 days).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 4 Oedema at end of treatment (60 days).

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vitamin D plus vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 4 Oedema at end of treatment (60 days).

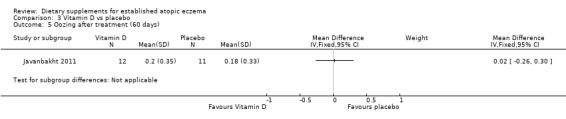

There was no significant difference in oozing as assessed by the clinician at the end of treatment for vitamin D versus placebo (MD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.30) (see Analysis 3.5).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vitamin D vs placebo, Outcome 5 Oozing after treatment (60 days).

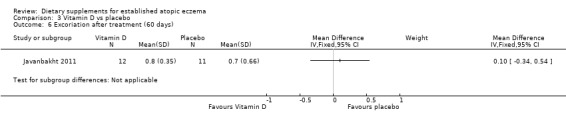

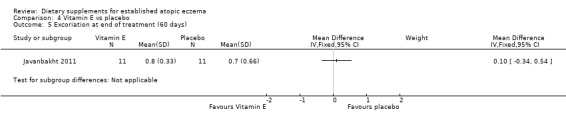

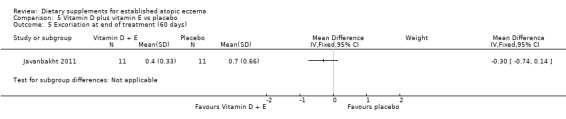

There was no significant difference in excoriation as assessed by the clinician at the end of treatment for vitamin D versus placebo (MD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.34 to 0.54) (see Analysis 3.6), vitamin E versus placebo (MD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.34 to 0.54) (see Analysis 4.5), or vitamin D plus E versus placebo (MD ‐0.3, 95% CI ‐0.74 to 0.14) (see Analysis 5.5).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vitamin D vs placebo, Outcome 6 Excoriation after treatment (60 days).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 5 Excoriation at end of treatment (60 days).

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vitamin D plus vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 5 Excoriation at end of treatment (60 days).

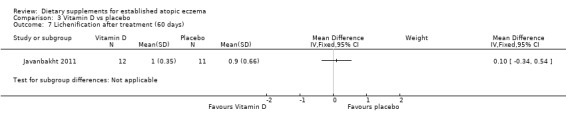

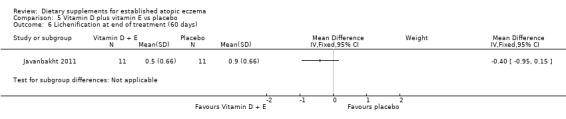

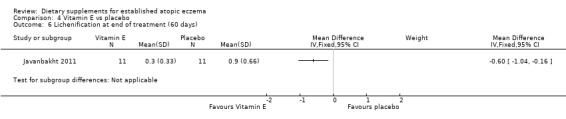

There was no significant difference in lichenification for vitamin D versus placebo (MD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.34 to 0.54) (see Analysis 3.7), or vitamin D plus E versus placebo (MD ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐0.95 to 0.15) (see Analysis 5.6). However, there was a significant difference in lichenification when vitamin E was compared to placebo (MD ‐0.60, 95% CI ‐1.04 to ‐0.16) (see Analysis 4.6).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vitamin D vs placebo, Outcome 7 Lichenification after treatment (60 days).

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vitamin D plus vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 6 Lichenification at end of treatment (60 days).

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 6 Lichenification at end of treatment (60 days).

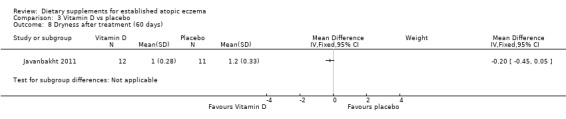

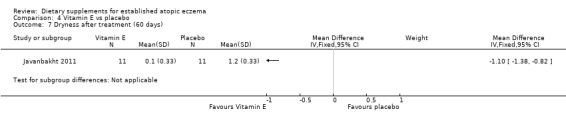

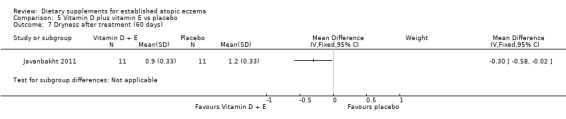

There was no significant difference in dryness for vitamin D versus placebo (MD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.45 to 0.05) (see Analysis 3.8), but dryness was significantly better in the vitamin E group compared to placebo (MD ‐1.10, 95% CI ‐1.38 to ‐0.82) (see Analysis 4.7), and significantly better in the vitamin D plus E group when compared to placebo (MD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐0.58 to ‐0.02) (see Analysis 5.7).

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vitamin D vs placebo, Outcome 8 Dryness after treatment (60 days).

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 7 Dryness after treatment (60 days).

5.7. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vitamin D plus vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 7 Dryness after treatment (60 days).

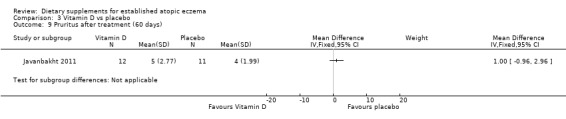

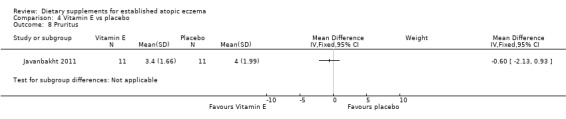

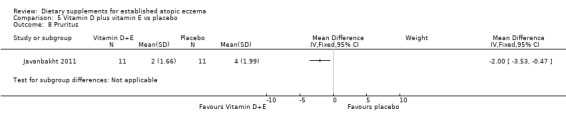

There was no significant difference in pruritis for vitamin D versus placebo (MD 1.00, 95% CI ‐0.96 to 2.96) (see Analysis 3.9), or vitamin E versus placebo for pruritus (MD ‐0.60, 95% CI ‐2.13 to 0.93) (see Analysis 4.8). Pruritis was significantly better in the vitamin D and vitamin E group compared with placebo (MD ‐2.0, 95% CI ‐3.53 to ‐0.47) (see Analysis 5.8).

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vitamin D vs placebo, Outcome 9 Pruritus after treatment (60 days).

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 8 Pruritus.

5.8. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vitamin D plus vitamin E vs placebo, Outcome 8 Pruritus.

Javanbakht 2011 did not address our primary outcomes (a) or (c); or our secondary outcomes (a), (c), (d), (e), and (f).

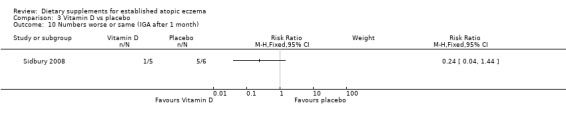

The second study (Sidbury 2008) compared vitamin D versus placebo in 11 children (aged 2 to 13 years) with mild AE over 1 month. The main outcome was the Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) after one month.

There was no data available for any of our prespecified primary and tertiary outcomes or any of our secondary outcomes except (a).

With regard to our secondary outcome (a) 'Global severity as rated by the participants or their physician', there was no significant difference in Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) for the number of participants who stayed the same or got worse after 1 month of treatment (RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.04 to 1.44) (see Analysis 3.10).

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vitamin D vs placebo, Outcome 10 Numbers worse or same (IGA after 1 month).

There was no significant difference in the change of mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores between the 2 groups (2.4, 95% CI, ‐8.4 to 3.7) (P = 0.40).

5. Pyridoxine hydrochloride (vitamin B6)

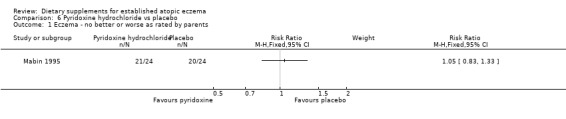

One study (Mabin 1995) of 48 children (older than 12 months) compared pyridoxine hydrochloride with placebo over 4 weeks. The main outcomes were global severity and parental‐rated symptoms of eczema after 4 weeks.

For our primary outcome (a)'Changes in participant‐rated or parent‐rated symptoms of atopic eczema', there was no significant difference in parental‐rated symptoms of eczema between the 2 groups at the end of treatment (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.33) (see Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Pyridoxine hydrochloride vs placebo, Outcome 1 Eczema ‐ no better or worse as rated by parents.

For our secondary outcome (a) 'Global severity as rated by the participants or their physician', there was no significant difference between the groups in global severity after 4 weeks ‐ only medians and ranges were given in the text: vitamin B6 = 109 (16 to 334) and placebo = 77 (13.3 to 346).

There were no data available for our prespecified primary outcomes (b) and (c), all our secondary outcomes except (a), and for our tertiary outcome measures.

6. Sea buckthorn oil

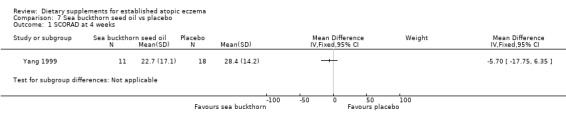

One study (Yang 1999) of 78 adults compared sea buckthorn seed oil versus sea buckthorn pulp oil versus placebo over 4 months. The main outcome was severity of atopic eczema measured by SCORAD.

There were no data available for any of our prespecified primary and tertiary outcomes, or any of our secondary outcomes except (b).

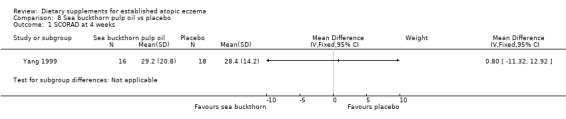

For our secondary outcome (b)'Global changes in composite rating scales using a published named scale', there was no significant difference in SCORAD at 4 weeks for sea buckthorn oil versus placebo (MD ‐5.70, 95% CI ‐17.75 to 6.35) (see Analysis 7.1), or for buckthorn pulp versus placebo (MD 0.80, 95% CI ‐11.32 to 12.92) (see Analysis 8.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Sea buckthorn seed oil vs placebo, Outcome 1 SCORAD at 4 weeks.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sea buckthorn pulp oil vs placebo, Outcome 1 SCORAD at 4 weeks.

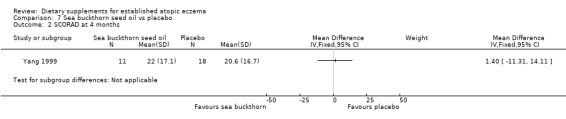

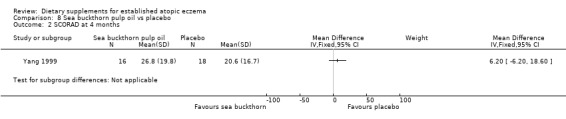

There was no significant difference in SCORAD at 4 months for sea buckthorn oil versus placebo (MD 1.40, 95% CI ‐11.31 to 14.11) (see Analysis 7.2), or for buckthorn pulp versus placebo (MD 6.2, 95% CI ‐6.2 to 18.6) (see Analysis 8.2).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Sea buckthorn seed oil vs placebo, Outcome 2 SCORAD at 4 months.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sea buckthorn pulp oil vs placebo, Outcome 2 SCORAD at 4 months.

7. Hempseed oil

One cross‐over study (Callaway 2005) of 20 adults (aged 25 to 60 years) compared hempseed oil versus placebo (olive oil), with 2 8‐week intervention periods and a 4‐week washout. The main outcome was severity of atopic dermatitis measured by participants' perceptions of changes in skin dryness and itchiness.

Subjective decreases in both skin dryness and itchiness were statistically significant after hempseed oil intervention (P = 0.027 and 0.023, respectively, as intra‐group comparisons). No such improvements were observed after olive oil intervention.

None of our prespecified primary, secondary, or tertiary outcomes were addressed by this study.

8. Sunflower oil

One study (Gimenez‐Arnau 1997) of 48 adults with chronic or severe atopic eczema, compared linoleic acid from sunflower oil versus fish oil versus placebo over 12 weeks. The main outcome was disease severity assessed by Rajka and eczema extension assessed by the Rule of Nines.

There were no data available for any of our prespecified primary and tertiary outcomes, or for our secondary outcomes except for (b).

For our secondary outcome (b) 'Global changes in composite rating scales using a published named scale', the text quoted a significant difference in the per cent reduction of the Rajka score and the Rule of Nines between sunflower oil and fish oil and between sunflower oil and placebo; however, no numbers were given for the number of participants in each arm.

9. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplementation

One study (Koch 2008) of 53 adults with atopic eczema compared DHA versus an isoenergetic control over 8 weeks. Global reduction in SCORAD was measured at eight weeks.

There were no data available for our prespecified primary outcomes or for our secondary outcomes except (b).

For our secondary outcome (b), the paper reported a significant reduction in SCORAD from baseline to eight weeks for the DHA group, but not for the isoenergetic control group.

For our tertiary outcomes, the paper reported that the diminished SCORAD in the DHA group was mainly attributed to the significant reduction of the affected areas from 12 (2 to 41 SCORAD points (median, range) at baseline to 7 (2 to 25) at week 8 (P = 0.02 calculated using Wilcoxon test for nonparametrical, paired data).

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review identified 11 randomised controlled trials of dietary supplements for the treatment of established atopic eczema. Two studies assessed fish oil versus olive oil or corn oil placebo. Oral zinc sulphate was compared to placebo in one study, and other single RCTs compared selenium versus selenium plus vitamin E versus placebo, vitamin D versus placebo, vitamin D versus vitamin E versus vitamins D and E together versus placebo, pyridoxine versus placebo, sea buckthorn seed oil versus sea buckthorn pulp oil versus placebo, hempseed oil versus placebo, sunflower oil (linoleic acid) versus fish oil versus placebo, and DHA versus control (saturated fatty acids of the same energy value).

Most of the studies evaluated were far too small in size to exclude even large treatment differences, so it is not surprising that most have failed to show any treatment differences. Such small studies are similarly unable to conclude that the treatments were ineffective due to the lack of precision of effects estimates inherent in such small studies.

Some of the interventions tested were quite complex in terms of combination of various products that might have had opposing beneficial or harmful effects. For example, the study by Bjorneboe included a combination of n‐3 and n‐6 fatty acids along with vitamins A, D, and E. At such an early stage of research, it is probably better to explore the effects of single compounds in placebo‐controlled studies so that each can be retained or eliminated as appropriate.

The three studies (Bjorneboe 1989; Gimenez‐Arnau 1997; Soyland 1994) looking at fish oil versus placebo found no significant differences for any of the primary outcomes. However, pooled analysis of two of the studies (Bjorneboe 1989; Soyland 1994) found that fish oil significantly improved the effect on daily living compared to placebo (our secondary outcome looking at quality of life). This analysis also found a significant difference in area affected at the end of treatment as assessed by the physician (one of our tertiary outcomes). One study evaluated itch at the end of the study and found that fish oil significantly improved itch compared to the placebo group (Bjorneboe 1989). The largest of the fish oil supplementation studies did not show any benefit over placebo (Soyland 1994).

One small study (Ewing 1991) of poor methodological quality failed to show the benefit of zinc supplementation in atopic eczema. The study found no significant difference between zinc sulphate and placebo in the severity of eczema at eight weeks in children. In addition, parental‐rated mean itch score was significantly better in the placebo group compared to the zinc group.

One small study (Fairris 1989) of poor methodological quality failed to show any benefit of selenium supplementation or selenium plus vitamin E supplementation over placebo.

Two studies (Javanbakht 2011; Sidbury 2008) found no benefit of vitamin D over placebo. One study (Javanbakht 2011) found no benefit of vitamin E over placebo, but found a significant difference in SCORAD at the end of treatment in favour of vitamin D plus E over placebo. A more recent study comparing vitamin E to placebo and the combination of vitamin E and D to placebo found no benefit of either vitamin E or D compared to placebo.

One study (Mabin 1995) of pyridoxine (vitamin B6) provided insufficient evidence to assess pyridoxine in people with atopic eczema. The study found no significant difference between pyridoxine and placebo in the severity of eczema at four weeks.

One study (Yang 1999) found no significant difference in SCORAD at four weeks in adults when sea buckthorn seed oil was compared to placebo or sea buckthorn pulp oil was compared to placebo.

One study (Callaway 2005) found no benefit of hempseed oil over placebo in adults.

One study (Gimenez‐Arnau 1997) found no benefit of sunflower oil over placebo in adults with chronic or severe atopic eczema. This study quoted a significant difference in the per cent reduction of Rajka score and Rule of Nines when sunflower oil was compared to fish oil and when sunflower oil was compared to placebo; however, we were unable to substantiate this since the number of participants in each arm was not given.

Quality of the evidence

Eleven poor quality studies were included in this review involving 596 participants: 3 fish oil supplement diets, 1 zinc supplement diet, 1 selenium supplement diet, 2 vitamin D supplement diets, 1 vitamin E supplement diet, 1 pyridoxine hydrochloride (vitamin B6) supplement diet, 1 sea buckthorn oil supplement diet, 1 hempseed oil supplement diet, and 1 sunflower oil supplement diet.

All three of the fish oil studies in adults were of poor methodological quality; two of the studies were in adults with moderate to severe atopic eczema and the third study was in adults with severe atopic eczema. Concealment of allocation was unclear in all three studies. None of the studies looked at short‐term (within six weeks) changes in participant‐rated or parent‐rated symptoms of atopic eczema, such as itching or sleep loss. None of the studies looked at reduction in the number of flares; however, one study reported a reduction in the use of topical steroids, and one study reported no difference in the use of topical steroids or antihistamine use.

Only three studies clearly demonstrated adequate concealment of allocation (Javanbakht 2011; Mabin 1995; Sidbury 2008). Blinding was unclear in over half of the studies. Only one small study (Sidbury 2008) had no losses to follow up and analysed by intention‐to‐treat. For two studies, the number of participants in each arm was not given. Only one study (Koch 2008) clearly described baseline comparability, whereas the other studies just gave comparability for participants completing the supplementation. Compliance was only clear in three studies. The severity of atopic eczema was only clear in seven of the studies; however, for most of the studies (73%) the certainly of atopic eczema was clear.

Whilst the promotion of various products claiming various skin benefits not supported by good evidence might be commonplace in the world of dietary supplements, we did not find any major concerns regarding conflicts of interest in the trials identified in this review. The inclusion of those studies where conflicts of interest with commercial organisations were declared did not alter our overall conclusions. The field of dietary supplements for health benefit is a large and complex one, which some have tried to summarise using "balloon race" depictions: http://www.informationisbeautiful.net/visualizations/snake‐oil‐supplements/

Potential biases in the review process

It is possible that we could have missed some published studies in our searches or that we are unaware of other unpublished studies. No potential biases were identified in relation to the review process.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results of this review are in agreement with a previous HTA review (Hoare 2000).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Disappointingly, we have not found any convincing evidence of the benefit of dietary supplements in eczema. It is not possible for us to claim that all of the supplements that were examined in this review are not effective, because all of the studies were of low quality and most were much too small (underpowered) to exclude even relatively moderate treatment benefits.

Whilst this review cannot exclude the possibility that dietary supplements may play a role in improving eczema, the absence of positive evidence means that they cannot be recommended to the public or for clinical practice at present.

Two small studies on fish oil suggest a possible modest benefit, but many outcomes were explored, and a convincingly positive result from a much larger study with a publicly registered protocol is needed before clinical practice can be influenced. In addition, one study comparing vitamin D plus E to placebo found a significant improvement of SCORAD at the end of treatment where vitamin D or vitamin E alone had not. This study was small, and a larger study is needed to confirm these results. There is also a real need to look closely at adverse events. It is unclear if these small but statistically significant differences are clinically worthwhile in the absence of better information on the scales used.

Whilst it is possible that some may argue that at least supplements do not do any harm, high doses of vitamin D may give rise to serious medical problems, and the cost of long‐term supplements may also mount up.

Implications for research.

The grounds for recommending further clinical trial research in this field are limited. Whilst it is true that public interest in supplements of various sorts for chronic diseases is quite high, the main lack of anything positive to date may reflect poorly‐designed, poorly‐reported, and underpowered studies. There needs to be a stronger theoretical, biological, epidemiological, and experimental rationale before recommending further research in this area. Much attention has already been focused on evening primrose oil with no clear sign of benefit (Williams 2003), although another Cochrane review will address this specific topic (Boehm 2003). Given the presence of at least some positive secondary/tertiary outcomes in two of the studies that have explored fish oil, and that there is at least some good theoretical basis why they might play a role in dampening down the inflammatory pathway, a much larger placebo‐controlled and well‐designed study might be worthwhile. Although recent evidence has suggested that increased vitamin D intake may play a role in altering immune responses (Schwalfenberg 2011) and in protecting atopic diseases, such as asthma, we are not aware of any convincing role in eczema prevention or treatment (Miyake 2010; Miyake 2011). There is, however, some emerging data on the role of vitamin D in possibly modifying immune responses in eczema (the sunshine hypothesis, Searing 2010), and one recent study has shown a possible link between eczema severity and low vitamin D levels.

Another study has shown that vitamin D supplementation could reverse some of the defects in the innate immune system associated with atopic eczema, such as the capacity to increase the production of broad spectrum antimicrobial peptides like cathelicidin, which may in turn decrease the risk of secondary infections (Hata 2008).

It is also worth pointing out that many of the "placebos" used substances, such as olive oil, which might not be inert, thereby, reducing the chances of finding a true biological effect in the tested interventions. Future researchers should think carefully about the nature of placebos that are used in such studies.

The clinical data is not sufficiently strong to warrant a large trial in this area yet, although it is an area worth following up. As for the other dietary supplements, we are unconvinced that there is sufficient biological or clinical data to suggest that further clinical trials are needed, although we would be happy to revise such a statement in the future if a new and convincing critical mass of evidence emerges.

Future studies should use outcome measures that are more readily clinically interpretable and should be informed by the outcome of the Harmonizing Outcomes for Eczema (HOME) project (Schmitt 2010; Schmitt 2011).

The measurement of surface area involvement is just one example of lack of consistency that could be addressed by harmonisation of outcome measures. Some have used terms such as 'eczema extent', 'eczema extension', 'area affected', and 'affected areas' in unclear ways; and it is equally unclear how and whether extent should be combined with other signs of eczema, such as oedema, redness, and scaliness.

Because little is known about how these supplements could work at a biologic level in allergic disease, little is known about their duration of action. This means that they are probably unsuitable for testing in cross‐over designs where each participant is given both treatments to try, because the effect of taking the first treatment may hang over into the next treatment phase.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 May 2015 | Amended | Two erroneous links in the plain language summary have been fixed. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2005 Review first published: Issue 2, 2012

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 May 2014 | Review declared as stable | A search of the GREAT (The Global Resource of Eczema Trials) database in February 2013 found just 1 study on Vitamin D supplementation, and another search of the GREAT database in May 2014 found only a few papers. Thus, this review has been marked stable because most of the papers were on probiotics and prebiotics, which are dealt with in another Cochrane review, and the paper on vitamin D is unlikely to move the existing vitamin D data in the review on in any meaningful way. An update has not been considered necessary for two successive years. Our Trials Search Co‐ordinator will run a new search in 2015 to re‐assess whether an update is needed. |

| 15 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Notes

A search of the GREAT (The Global Resource of Eczema Trials) database in February 2013 found just 1 study on Vitamin D supplementation, and another search of the GREAT database in May 2014 found only a few papers. Thus, this review has been marked stable because most of the papers were on probiotics and prebiotics, which are dealt with in another Cochrane review, and the paper on vitamin D is unlikely to move the existing vitamin D data in the review on in any meaningful way. An update has not been considered necessary for two successive years. Our Trials Search Co‐ordinator will run a new search in 2015 to re‐assess whether an update is needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Finola Delamere and Weija Zhang for their contribution to the published protocol.

The editorial base would like to thank the Key Editor, Urba Gonzalez, Jo Leonardi‐Bee and Sarah Garner who were our Statistics and Methods Editors respectively, Eric Simpson who was a clinical referee, and another clinical referee who wishes to remain anonymous. We also wish to thank Kim Thomas who was our consumer referee.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register search strategy

((atopic AND eczema) OR (atopic AND dermatitis) OR (besnier* AND prurigo) OR (neurodermatitis) OR (infant* AND eczema) OR (childhood AND eczema) OR eczema) AND ((fat* and acid*) or (linoleic and acid*) or (arachidonic and acid*) or (eicosapentanoic and acid*) or eicosanoid* or (fish and oil*) or pyridoxine or (vitamin* and B6) or (vitamin* and E) or (zinc and salt*) or (zinc and compound*) or selenium or (diet* and supplement*))

Appendix 2. Cochrane Library search strategy

#1(atopic dermatitis) or (atopic eczema) or (eczema*) or (neurodermatitis) or (infantile eczema) #2(child* eczema*) or (Besnier's prurigo) #3MeSH descriptor Neurodermatitis explode all trees #4MeSH descriptor Eczema explode all trees #5MeSH descriptor Dermatitis, Atopic explode all trees #6(#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5) #7(fat* acid*) or (fish oil*) or (diet* near supplement*) or (pyridoxine) or (vitamin B6) #8(zinc compound*) or (zinc and salt*) or(selenium) or (vitamin E) #9(linoleic acid*) or (arachidonic acid*) or (eicosapentanoic acid *) or (eicosanoid*) #10MeSH descriptor Fish Oils explode all trees #11MeSH descriptor Fatty Acids explode all trees #12MeSH descriptor Linoleic Acids explode all trees #13MeSH descriptor Arachidonic Acid explode all trees #14MeSH descriptor Vitamin B 6 explode all trees #15MeSH descriptor Vitamin E explode all trees #16MeSH descriptor Selenium explode all trees #17MeSH descriptor Zinc, this term only #18(#7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17) #19(#6 AND #18) #20SR‐SKIN #21(#19 AND NOT #20)

Appendix 3. MEDLINE (OVID) search strategy

(This search strategy also used for AMED and PsycInfo).