Abstract

Objective

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychiatric hospitalizations in Ontario are unknown. The purpose of this study was to identify changes to volumes and characteristics of psychiatric hospitalizations in Ontario during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A time series analysis was done using psychiatric hospitalizations with admissions dates from July 2017 to September 2021 identified from provincial health administrative data. Variables included monthly volumes of hospitalizations as well as proportions of stays <3 days and involuntary admissions, overall and by diagnosis (mood, psychotic, addiction, and other disorders). Changes to trends during the pandemic were tested using linear regression.

Results

A total of 236,634 psychiatric hospitalizations were identified. Volumes decreased in the first few months of the pandemic before returning to prepandemic volumes by May 2020. However, monthly hospitalizations for psychotic disorders increased by ∼9% compared to the prepandemic period and remained elevated thereafter. Short stays and involuntary admissions increased by approximately 2% and 7%, respectively, before trending downwards.

Conclusion

Psychiatric hospitalizations quickly stabilized in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, evidence suggested a shift towards a more severe presentation during this period.

Keywords: COVID-19, psychiatric hospitalizations, mental health services

Abrégé

Objectif

Les répercussions de la pandémie de la COVID-19 sur les hospitalisations psychiatriques en Ontario ne sont pas connues. La présente étude a pour but d’identifier les changements des volumes et des caractéristiques des hospitalisations psychiatriques en Ontario durant la pandémie de la COVID-19.

Méthodes

Une analyse de séries chronologiques a été effectuée à l’aide des hospitalisations psychiatriques et des dates d’admission de juillet 2017 à septembre 2021, identifiées d’après les données administratives provinciales de la santé. Les variables comprenaient les volumes d’hospitalisation mensuels ainsi que les proportions des séjours de < 3 jours et les hospitalisations involontaires, en général et selon le diagnostic (troubles de l’humeur, psychotiques, de dépendance et autres). Les changements des tendances durant la pandémie ont été vérifiés à l’aide de la régression linéaire.

Résultats

236 634 hospitalisations psychiatriques ont été identifiées. Les volumes ont diminué dans les premiers mois de la pandémie avant de revenir aux volumes pré-pandémiques en mai 2020. Cependant, les hospitalisations mensuelles pour des troubles psychotiques ont augmenté de ∼9% comparé à la période pré-pandémique et sont demeurées élevées par la suite. Les brefs séjours et les hospitalisations involontaires ont augmenté d’approximativement 2% et 7%, respectivement, avant de tendre vers le bas.

Conclusion

Les hospitalisations psychiatriques se sont rapidement stabilisées en réponse à la pandémie de la COVID-19. Toutefois, les données probantes ont suggéré une évolution vers une présentation plus grave durant cette période.

Introduction

For Ontarians in need of psychiatric inpatient treatment, the COVID-19 pandemic fundamentally altered the nature of and experiences receiving care.1,2 Inpatient treatment practice standards for psychiatric conditions, which include communal living and group-based therapies, were disrupted as institutions rapidly implemented new infection control procedures designed to limit the spread of the novel coronavirus.1,3 Outside of hospitals, changes to help-seeking due to fear of hospital-acquired infection,4–6 worsening mental health in the populace consequent to the pandemic,7,8 and shifts to virtual outpatient care3,9,10 were additional factors that may have fundamentally altered the need for and receipt of inpatient care for psychiatric conditions during the earliest months of the pandemic. However, little is known about the impact of the pandemic on the volumes and nature of psychiatric hospitalizations. Given the ongoing strain to the Ontario hospital system brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, the paucity of information around volumes and characteristics of psychiatric hospitalizations represent a pertinent blind spot for systems planning that needs addressing to ensure this critical system of care remains functioning in this period of ongoing uncertainty. The primary objective of this study was to assess changes in trends of psychiatric hospitalizations before and during the pandemic, both for the overall volume of hospitalizations and by clinically relevant diagnostic groups (i.e., mood disorders, psychotic disorders, substance-related and addictive disorders, and all other conditions). As a secondary objective, we examined changes in trends of the clinical characteristics of the hospitalizations, including the proportions of (i) hospitalizations with short stays (i.e., stays <3 days), and (ii) hospitalizations where admission was involuntary.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

Psychiatric hospitalizations with admission dates from July 1, 2017, to September 30, 2021, were identified in the Ontario Mental Health Reporting System (OMHRS), a database containing assessments of patients admitted to adult mental health beds within the province of Ontario, Canada. Data from the OMHRS was acquired from ICES. ICES is an independent, nonprofit research institute whose legal status under Ontario's health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyse health care and demographic data, without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement. Patient-level linkages to other ICES data holdings were done to acquire additional patient characteristics, including the Registered Persons Database for sociodemographic information. Linkages were performed using unique, encoded identifiers developed at ICES. ICES is a prescribed entity under Ontario's Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA). Section 45 of PHIPA authorizes ICES to collect personal health information, without consent, for the purpose of analysis or compiling statistical information with respect to the management of, evaluation or monitoring of, the allocation of resources to or planning for all or part of the health system. Likewise, projects that use data collected by ICES are exempt from institutional research ethics board review.

An initial 246,303 unique episodes were identified in the OMHRS. Thereafter, records were excluded if they involved (1) a patient younger than 16 or older than 105 years of age, or with missing data on age (1,128 records), (2) missing information on sex (0 records), (3) a patient who did not reside in Ontario during the analysis period (232 records), (4) a forensic patient (3,117 records), (5) invalid data (e.g., patient death recorded prior to admission) (148 records), or (6) a patient admitted for a neurocognitive disorder (5,044 records). These exclusions resulted in a final tally of 236,634 episodes of hospitalization with time spent in a mental health bed.

Variables

We examined sociodemographic variables that are known to affect health-care use11–14; these included age, sex, neighbourhood-level income quintile, and rurality, which was measured using the Rurality Index of Ontario 15 (with scores of 40+ defined as rural). Hospitalizations were categorized using the patients’ primary Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) diagnosis drawn from the patient's discharge diagnosis, or, if the discharge diagnosis was missing, their provisional diagnosis at admission (see Supplemental Table S1 for relevant diagnostic codes). Categories included (1) mood disorders, (2) psychotic disorders, (3) substance-related and addictive disorders, and (4) all other diagnoses (e.g., anxiety disorders, stressor-related disorders, personality disorders, and eating disorders). Hospitalizations with stays <3 days were coded as short stays (yes/no). Involuntary admission status was drawn from the initial assessment for the episode of hospitalization and included individuals remanded into care at the behest of a clinician for psychiatric assessment under the Mental Health Act 16 (yes/no).

Analysis

To describe changes in hospitalizations occurring at the beginning of the pandemic, counts and proportions of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics for the hospitalizations in March, April, and May 2020 were calculated. These months were selected as they encompassed the period when the Government of Ontario first introduced extensive lockdown and social distancing measures. For comparison, summary statistics were also calculated for March through May 2019 and 2021.

We used a time series approach to identify changes to volumes and characteristics of monthly psychiatric hospitalizations identified during the observation window. Counts of hospitalizations were aggregated by month, as were proportions of short stays and involuntary admissions. Linear regression models were fit to estimate changes to trends, and associated 95% confidence intervals, before and during the pandemic. The models were constructed around breakpoints that occurred during the first few months of the pandemic, where volumes of hospitalizations changed considerably. All analyses were done using Stata 15 software (StataCorp LLC., College Station, Texas).

Results

Descriptive characteristics of hospitalizations in March, April, and May 2019, 2020, and 2021 are found in Table 1. We observed drops in volumes of hospitalizations in 2020 (12,096), compared to 2019 (14,181), though volumes in 2021 (14,692) were broadly similar to those in 2019. Changes to diagnosis were also observed, including large drops in volumes of hospitalizations for mood disorders and for the “other disorders” category between 2019 and 2020 (1200 and 500 less in March 2020, respectively), before returning to similar volumes in 2021. Conversely, volumes of hospitalizations for psychotic and substance use disorders saw only modest drops (∼100 less each) in March, April, and May 2020 compared to 2019. Moreover, evidence of heightened volumes in 2021 compared to the prepandemic period was observed for psychotic disorders (9% higher than in 2019) and substance use disorders (10% higher than in 2019) for the included months. As a result, psychotic and substance use disorders made up a larger proportion of hospitalizations from March to May 2020 and 2021, compared with the same period in 2019. Likewise, the proportions of hospitalizations where admission was involuntary (78.4%) or with a stay of <3 days (34.1%) were higher in 2020 compared to 2019 (involuntary admission: 74%; short stay: 31.5%). Finally, the proportion of hospitalizations where the patient was male was larger in March 2020 compared to March 2019, before decreasing in 2021 (50.6%, 54.5%, and 51.8% for 2019, 2020, and 2021, respectively).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics for Inpatient Psychiatric Admissions in Months of March, April, and May in 2019, 2020, and 2021.

| Variable | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Column % | N | Column % | N | Column % | |

| Total volume | 14,181 | — | 12,096 | — | 14,692 | — |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 7,010 | 49.4 | 5,501 | 45.5 | 7,083 | 48.2 |

| Male | 7,171 | 50.6 | 6,595 | 54.5 | 7,609 | 51.8 |

| Age groups | ||||||

| 16 to 17 | 237 | 1.7 | 129 | 1.1 | 265 | 1.8 |

| 18 to 21 | 1,594 | 11.2 | 1,340 | 11.1 | 1,617 | 11.0 |

| 22 to 24 | 1,329 | 9.4 | 1,130 | 9.3 | 1,282 | 8.7 |

| 25 to 44 | 6,276 | 44.3 | 5,680 | 47.0 | 6,973 | 47.5 |

| 45 to 64 | 3,694 | 26.0 | 2,974 | 24.6 | 3,495 | 23.8 |

| 65 to 84 | 984 | 6.9 | 800 | 6.6 | 1,011 | 6.9 |

| 85 to 105 | 67 | 0.5 | 43 | 0.4 | 49 | 0.3 |

| Neighbourhood income quintile | ||||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 4,708 | 33.2 | 4,154 | 34.3 | 4,973 | 33.8 |

| Q2 | 3,097 | 21.8 | 2,683 | 22.2 | 3,061 | 20.8 |

| Q3 | 2,394 | 16.9 | 2,002 | 16.6 | 2,550 | 17.4 |

| Q4 | 2,007 | 14.2 | 1,587 | 13.1 | 2,024 | 13.8 |

| Q5 (highest) | 1,803 | 12.7 | 1,483 | 12.3 | 1,923 | 13.1 |

| Missing | 172 | 1.2 | 187 | 1.5 | 161 | 1.1 |

| Rurality† | ||||||

| Rural | 1,088 | 7.7 | 806 | 6.7 | 1,044 | 7.1 |

| Non-rural | 12,734 | 89.8 | 10,970 | 90.7 | 13,276 | 90.4 |

| Missing | 359 | 2.5 | 320 | 2.6 | 372 | 2.5 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Mood disorders | 4,781 | 33.7 | 3,505 | 29.0 | 4,531 | 30.8 |

| Psychosis disorders | 3,884 | 27.4 | 3,752 | 31.0 | 4,231 | 28.8 |

| Substance-related and addictive disorders | 2,534 | 17.9 | 2,408 | 19.9 | 2,802 | 19.1 |

| Other disorders | 2,982 | 21.0 | 2,431 | 20.1 | 3,128 | 21.3 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Involuntary stays | 10,493 | 74.0 | 9,485 | 78.4 | 11,271 | 76.7 |

| Short stays‡ | 4,469 | 31.5 | 4,127 | 34.1 | 4,883 | 33.2 |

† Rural is defined as a score of 40+ on the Rurality Index of Ontario.

‡Stays <3 days.

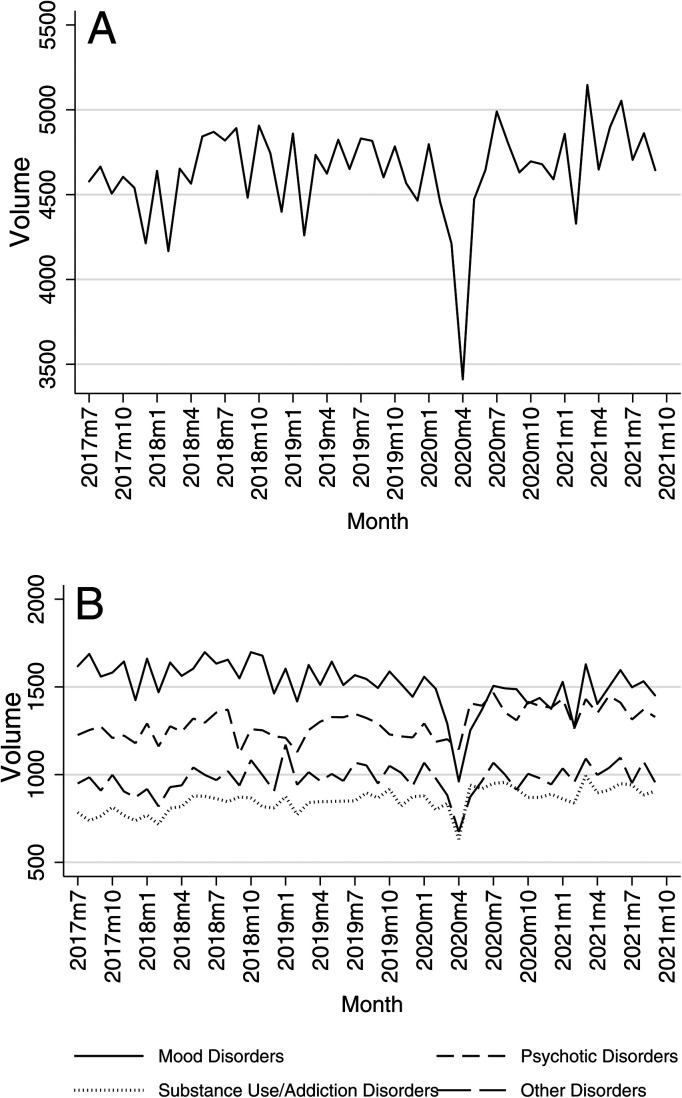

The findings of these descriptive analyses are supported by our time series analysis. Though a large drop in the overall volume of hospitalizations was observed in March and April 2020 (Figure 1A), monthly trends before (β for trend: 3.96, 95% CI: −3.78 to 11.71) and after (β for trend: 9.84, 95% CI: −12.14 to 31.83) this breakpoint did not differ in a significant fashion (β for change in slope: 5.88, 95% CI: −15.66 to 27.43). However, this overall trend was not consistent across diagnoses (Figure 1B). Hospitalizations for mood disorders decreased in the period prior to the pandemic (β for trend: −3.20, 95% CI: −6.22 to −0.19), before sharply dropping in the months between March and May 2020. However, after rebounding in June 2020, monthly trends were no longer decreasing (β for trend: 5.29, 95% CI: −5.07 to 15.66). Hospitalizations for psychotic disorders increased by an average of about 100 hospitalizations (∼9%) during the pandemic compared to the period immediately prior to the pandemic, though trends during these 2 periods did not differ in a significant fashion (β for change in slope: 1.57, 95% CI, −5.25 to 8.38). Hospitalizations for substance-related and addictive disorders increased in the period prior to the pandemic (β for trend: 3.31, 95% CI, 1.72 to 4.90), before experiencing a sharp decrease in March and April 2020. However, after rebounding in May 2020, the increasing trend in hospitalizations for substance-related and addictive disorders was no longer observed (β for trend: −0.91, 95% CI, −5.31 to 3.49). Finally, hospitalizations for all other conditions increased prior to the pandemic (β for trend: 3.14, 95% CI, 0.62 to 5.66), before dropping over the months between March and May 2020, thereafter returning to volumes similar to prepandemic. In the period after the breakpoint, hospitalizations no longer increased in a significant fashion (β for trend: 2.66, 95% CI, −4.04 to 9.35).

Figure 1.

Volumes of psychiatric hospitalizations in Ontario, Canada from July 2017 to September 2021, overall (A) and by diagnosis (B).

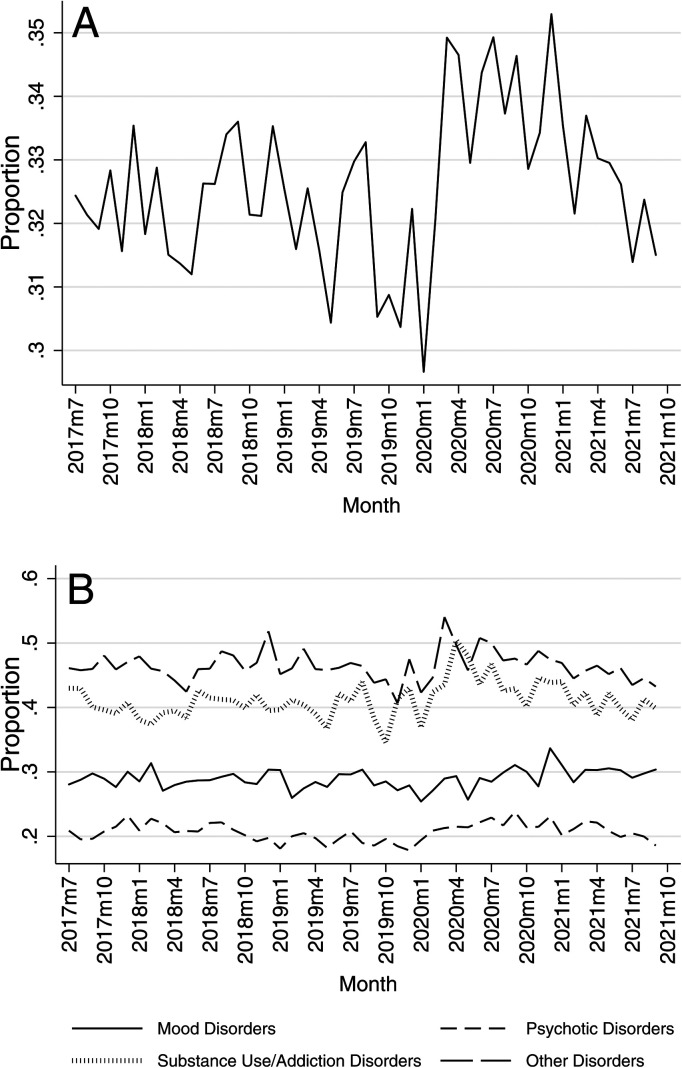

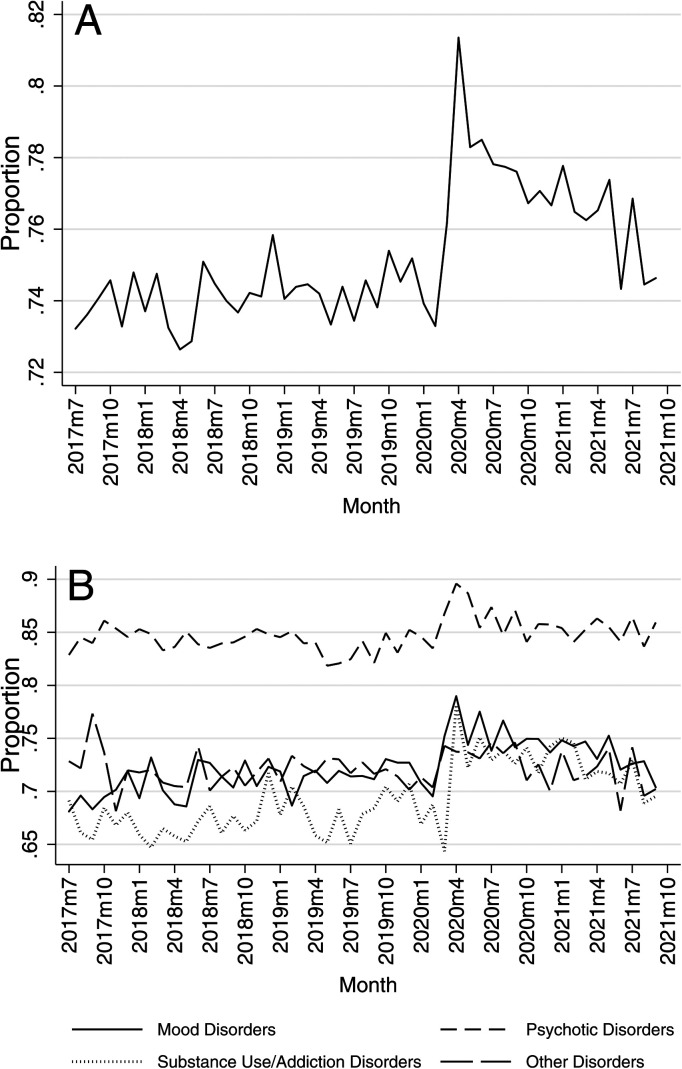

The proportion of hospitalizations with a short stay (Figure 2A) increased by 2% in March 2020 and thereafter began to decline (β for trend: −0.0015, 95% CI, −0.0022 to −0.0008). This trend was similar across all diagnoses (Figure 2B), save for hospitalizations for mood disorders, which began slowly increasing by 0.1% a month during the pandemic without an initial spike (β for trend: 0.0009, 95% CI, 0.0001 to 0.0021). Likewise, the proportion of hospitalizations where the admission was involuntary (Figure 3A) saw a sharp increase (∼7%) beginning in March and April 2020, before entering into a period of decline in May 2020 (β for trend: −0.0021, 95% CI, −0.0029 to −0.0013). Similar trends for involuntary admissions were observed across the diagnostic group (Figure 3B), save for admissions for psychotic disorders; among this group, there was a small ∼2% increase during the pandemic, with no evidence of a significant negative trend in the period during the pandemic (β for trend: −0.0006, 95% CI, −0.0018 to 0.0007).

Figure 2.

Proportion of psychiatric hospitalizations with stays <3 days in Ontario, Canada from July 2017 to September 2021, overall (A) and by diagnosis (B).

Figure 3.

Proportion of psychiatric hospitalizations where admission was involuntary in Ontario, Canada from July 2017 to September 2021, overall (A) and by diagnosis (B).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated changes in trends of psychiatric hospitalizations in Ontario during the COVID-19 pandemic using a time series approach. Similar to several international studies,17–20 we identified a large drop in volumes of hospitalizations in the earliest months of the pandemic. However, this drop was short-lived, as volumes returned to levels similar to prepandemic levels by May 2020. Furthermore, disruptions to the volumes of hospitalizations during subsequent periods of lockdown that began in December 2020 and April 2021 were not apparent, suggesting that the inpatient system of care for psychiatric conditions had adapted quickly to maintain accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nevertheless, our findings point to several clinically significant changes to the underlying nature of hospitalizations during the peripandemic period and beyond, in particular increases in volumes of hospitalizations for psychotic disorders as well as increased proportions of involuntary admissions. As suggested by global evidence,18,19,21,22 the drop in volumes of admissions in the earliest months of the pandemic was partially explained by voluntary help seekers avoiding care in hospital settings. Within Ontario, this reduction was likely driven by individuals with conditions such as mood disorders delaying care, as evidenced by the large decrease in volumes of hospitalizations for these conditions in the first few months of the pandemic. These factors consequently biased hospitalizations during the peripandemic period toward patients with a more severe presentation.

The increased proportion of involuntary admissions may reflect the success of the system of care in addressing challenges for those experiencing the most pressing need. It is unknown if delays/avoidance in seeking care in hospital for the resulting “missing” proportion of voluntary admissions was associated with worsening mental health for individuals who would have otherwise sought care in a hospital if not for the pandemic. As noted previously, new challenges to help-seeking such as fear of hospital-acquired infection and shelter-in-place requirements may have acted to disincentivize access to care in hospitals for those seeking care voluntarily.4–6 Thus, research investigating behavioural changes to help-seeking for mental health conditions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic would be beneficial to understanding if voluntary help-seekers saw worsening symptoms during the pandemic.

The continued elevated volumes of hospitalizations for psychotic disorders even as overall volumes returned to prepandemic levels may suggest that individuals living with these disorders face new challenges stemming from the pandemic. Though evidence from Ontario has found that primary care visits for these conditions in the first year of the pandemic were largely maintained virtually, 23 those unable to make the shift to virtual care may have had their continuity of care disrupted, 3 which has been found to be a predictor of future relapses. 24 Additionally, the possibility that those living with severe psychotic conditions would face challenges due to new norms requiring extended periods of isolation has been previously raised, given the known role of community social support in supporting care outside of the hospital. 3 The extent to which the breakdown of community supports has exacerbated severe mental illness (and thus the need for hospitalization) is unknown, though this is one plausible explanation for the increase in the volume of hospitalizations that we observed.

Given the complex and costly needs of those living with psychotic disorders (e.g., high and often poorly managed multimorbidity, higher costs, and long lengths of stay when hospitalized),25–28 the sustained 9% rise in hospitalizations for these conditions represents a challenge for a hospital system facing increasingly acute staffing and budgetary shortfalls. Thus, further research is warranted to investigate the causes of these increases in hospitalizations for psychotic disorders, including whether there has been a clinical deterioration for those with severe mental health conditions during the pandemic period.

Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this study is the use of data comprising all psychiatric hospitalizations in dedicated mental health beds in Ontario occurring over the observation period, thus providing a systems view of hospitalizations before and during the pandemic. Furthermore, our analysis provided insights into specific trends experienced across important diagnostic groups, including an increased volume of hospitalizations for psychotic disorders. Thus, while our analysis primarily confirms existing data around peripandemic reductions in hospitalization volumes, the granularity provided by our analysis across diagnoses may help identify care issues for high-risk patients undergoing hospitalization, particularly for those experiencing severe mental illness such as psychosis, given that hospitalizations for these disorders remained elevated to the end of our observation window. This study has several limitations. Our analysis used hospital administrative data that was not intended for research purposes; this may have led to measurement limitations. For example, diagnosis ascertainment was based on routine administrative coding, which may be prone to data entry errors and may not entirely reflect validated clinical assessment. Additionally, we may have missed trends subsequent to our observation period, which did not cover the entirety of the COVID-19 pandemic; this may be an important omission given the possible impacts of the emergence of the super infectious Omicron variants in late 2021 as well as the removal of most public health restrictions in Ontario in early 2022. Finally, our analysis did not include stays for psychiatric conditions spent in nonmental health beds, which make up an additional small volume of monthly hospitalizations for these conditions, and which are recorded in a separate database from the OMHRS.

Conclusion

Despite the social and institutional upheaval brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, the system of inpatient hospital-based care for mental health and substance use conditions in Ontario responded quickly, returning to volumes characteristic of the prepandemic period by late spring of 2020. However, changes to the underlying makeup of conditions for which individuals were admitted as well as characteristics of these hospitalizations point to a shift towards more severe presentations during this period.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cpa-10.1177_07067437231167386 for Adult Psychiatric Hospitalizations in Ontario, Canada Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic by Bryan Tanner, MSc, Paul Kurdyak, MD, PhD and Claire de Oliveira, PhD in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC). This document used data adapted from the Statistics Canada Postal CodeOM Conversion File, which is based on data licensed from Canada Post Corporation, and/or data adapted from the Ontario Ministry of Health Postal Code Conversion File, which contains data copied under license from ©Canada Post Corporation and Statistics Canada. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI) and the Ontario Ministry of Health. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed in the material are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the funding or data sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario Ministry of Health is intended nor should be inferred.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Paul Kurdyak and Claire de Oliveira contributed to the study's conception and design. Analyses were performed by Bryan Tanner. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Bryan Tanner and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ORCID iDs: Bryan Tanner https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8250-623X

Paul Kurdyak https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8115-7437

Data Availability Statement: The dataset from this study is held securely in the coded form at ICES. While legal data sharing agreements between ICES and data providers (e.g., healthcare organizations and government) prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet prespecified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS (email: das@ices.on.ca). The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Hanafi S, Dufour M, Dore-Gauthier V, Prasad MSR, Charbonneau M, Beck G. COVID-19 and Canadian psychiatry: la COVID-19 et la psychiatrie au Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2021;66(9):832-841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moesmann Madsen M, Dines D, Hieronymus F. Optimizing psychiatric care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;142(1):70-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kozloff N, Mulsant BH, Stergiopoulos V, Voineskos AN. The COVID-19 global pandemic: implications for people with schizophrenia and related disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46(4):752-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong LE, Hawkins JE, Langness S, Murrel KL, Iris, P, Sammann A. Where are all the patients? Addressing COVID-19 fear to encourage sick patients to seek emergency care. NJEM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westgard BC, Morgan MW, Vazquez-Benitez G, Erickson LO, Zwank MD. An analysis of changes in emergency department visits after a state declaration during the time of COVID-19. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(5):595-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baugh JJ, White BA, McEvoy D, et al. The cases not seen: patterns of emergency department visits and procedures in the era of COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:476-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:531-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vigo D, Patten S, Pajer K, et al. Mental health of communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(10):681-687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Childs AW, Klingensmith K, Bacon SM, Li L. Emergency conversion to telehealth in hospital-based psychiatric outpatient services: strategy and early observations. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glazier RH, Green ME, Wu FC, Frymire E, Kopp A, Kiran T. Shifts in office and virtual primary care during the early COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ. 2021;193(6):E200-EE10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen R. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magaard JL, Seeralan T, Schulz H, Brutt AL. Factors associated with help-seeking behaviour among individuals with major depression: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts T, Miguel Esponda G, Krupchanka D, Shidhaye R, Patel V, Rathod S. Factors associated with health service utilisation for common mental disorders: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting Andersen’s behavioral model of health services use: a systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. GMS Psycho-Soc-Med. 2012:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krajl B. Measuring rurality—RIO2008 BASIC: Methodology and results. Toronto, ON: OMA Economics Department; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preti A, Rucci P, Santone G, et al. Patterns of admission to acute psychiatric in-patient facilities: a national survey in Italy. Psychol Med. 2009;39(3):485-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romer TB, Christensen RHB, Blomberg SN, Folke F, Christensen HC, Benros ME. Psychiatric admissions, referrals, and suicidal behavior before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark: a time-trend study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;144(6):553-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dvorak L, Sar-El R, Mordel C, Schreiber S, Tene O. The effects of the 1(st) national COVID-19 lockdown on emergency psychiatric visit trends in a tertiary general hospital in Israel. Psychiatry Res. 2021;300:113903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonello F, Zammit D, Grech A, Camilleri V, Cremona R. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health hospital admissions: comparative population-based study. BJPsych Open. 2021;7(5):E141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boldrini T, Girardi P, Clerici M, et al. Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on admissions to general hospital psychiatric wards in Italy: reduced psychiatric hospitalizations and increased suicidality. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;110:110304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies M, Hogarth L. The effect of COVID-19 lockdown on psychiatric admissions: role of gender. BJPsych Open. 2021;7(4):E112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clerici M, Durbano F, Spinogatti F, Vita A, De Girolamo G, Micciolo R. Psychiatric hospitalization rates in Italy before and during COVID-19: did they change? An analysis of register data. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37(4):283-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stephenson E, Yusuf A, Gronsbell J, et al. Disruptions in primary care among people with schizophrenia in Ontario, Canada, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Psychiatry. 2022:7067437221140384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puntis SR, Rugkasa J, Burns T. The association between continuity of care and readmission to hospital in patients with severe psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(12):1633-1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen E, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Ani C, et al. Schizophrenia hospitalization in the US 2005–2014: examination of trends in demographics, length of stay, and cost. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(15):e25206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Oliveira C, Mason J, Kurdyak P. Characteristics of patients with mental illness and persistent high-cost status: a population-based analysis. CMAJ. 2020;192(50):E1793-EE801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang A, Amos TB, Joshi K, Wang L, Nash A. Understanding healthcare burden and treatment patterns among young adults with schizophrenia. J Med Econ. 2018;21(10):1026-1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tulloch AD, Fearon P, David AS. Length of stay of general psychiatric inpatients in the United States: systematic review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(3):155-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cpa-10.1177_07067437231167386 for Adult Psychiatric Hospitalizations in Ontario, Canada Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic by Bryan Tanner, MSc, Paul Kurdyak, MD, PhD and Claire de Oliveira, PhD in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry