Abstract

Felodipine is a calcium channel blocker with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Researchers have stated that oxidative stress and inflammation also play a role in the pathophysiology of gastric ulcers caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The aim of this study was to investigate the antiulcer effect of felodipine on indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers in Wistar rats and compare it with that of famotidine. The antiulcer activities of felodipine (5 mg/kg) and famotidine were investigated biochemically and macroscopically in animals treated with felodipine (5 mg/kg) and famotidine in combination with indomethacin. The results were compared with those of the healthy control group and the group administered indomethacin alone. It was observed that felodipine suppressed the indomethacin-induced malondialdehyde increase (P<0.001); reduced the decrease in total glutathione amount (P<0.001), reduced the decrease superoxide dismutase (P<0.001), and catalase activities (P<0.001); and significantly inhibited ulcers (P<0.001) at the tested dose compared with indomethacin alone. Felodipine at a dose of 5 mg/kg reduced the indomethacin-induced decrease in cyclooxygenase-1 activity (P<0.001) but did not cause a significant reduction in the decrease in cyclooxygenase-2 activity. The antiulcer efficacy of felodipine was demonstrated in this experimental model. These data suggest that felodipine may be useful in the treatment of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastric injury.

Keywords: felodipine, indomethacin, inflammation, oxidative stress, peptic ulcer

Introduction

Indomethacin is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) belonging to the arylalkanoic family derived from 2-arylacetic acids [1]. The effects of indomethacin result from the inhibition of prostaglandin (PG) synthesis [2]. Therefore, indomethacin is used in the treatment of inflammatory diseases such as chronic rheumatoid arthritis, periarthritis, osteoarthritis, spondylosis deformans, and acute gout [1]. Cytoprotective PGs are produced by cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), and inflammatory PGs are produced by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) [3]. Whereas COX-1 is responsible for maintaining physiological functions such as gastrointestinal system protection, COX-2 is the inducible enzyme responsible for inflammatory events [4, 5]. This information indicates that the toxic effect of indomethacin on the stomach is related to COX-1 inhibition. It is understood from the literature that, apart from COX-1 enzyme inhibition, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are one of the major components in the pathogenesis of indomethacin-induced gastric injury [6, 7]. In addition, calcium (Ca2+) has been reported to play a role in the pathogenesis of indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers [8]. Previous studies have shown that aggressive factors leading to gastric ulcers cause increased permeability of the gastric mucosa and intracellular Ca2+ accumulation [9]. Elevation of intracellular Ca2+ levels is assumed to be an important step in the pathogenesis of oxidative damage [10]. Researchers have stated that the increase in COX-2 activity and decrease in COX-1 activity are directly proportional to the increase in intracellular Ca2+ amount [11, 12]. All this information indicates that a Ca2+ channel antagonist drug may be useful in the treatment of indomethacin induced gastric ulcer.

Felodipine, whose effect we investigated against indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers in this study, is a dihydropyridine derivative L-type Ca2+ channel blocker (CCB) drug used in the treatment of hypertension [13]. Studies show that felodipine is more vasoselective than commonly used CCBs such as amlodipine and nifedipine [14]. Studies have stated that the cardioprotective effect of felodipine may be due to its antioxidant activity [15]. In addition, felodipine has been reported to inhibit ROS in endothelial cells [16]. Studies investigating the effect of felodipine on indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers were not found in the literature. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the effect of felodipine on experimental ulcers induced by indomethacin in rats and to compare it with the effects of famotidine.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Twenty four, albino Wistar rats weighing between 250 and 265 g were used in the experiment. The animals were obtained from the Erzincan Binali Yıldırım University Medical Experimental Application and Research Center (Erzincan,Türkiye). The animals were housed and fed in a suitable laboratory environment at normal room temperature (22°C) under appropriate conditions (12 h of light and 12 h of darkness). Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the National Guidelines for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the local animal ethics committee of Erzincan Binali Yıldırım University, Erzincan, Türkiye (Ethics Committee No.: 2023/03, dated March 30, 2023).

Chemicals

The indomethacin used in the experiment was obtained from Deva Holding (Istanbul, Türkiye). Felodipine was obtained from Astra Zeneca PLC (Istanbul, Türkiye). Thiopental sodium was obtained from İ.E ULAGAY (Istanbul, Türkiye).

Experimental groups

The rats used in the experiment were divided into four groups: the healthy control (HC) group, the indomethacin-alone (IND) group, the felodipine + indomethacin (Fel+IND) group, and the famotidine + indomethacin (Fam+IND) group.

Ulcer tests in rats

The Fel+IND (n=6) group was fasted for 12 h (free to drink water) and administered felodipine orally to the stomach at a dose of 5 mg/kg. Famotidine (20 mg/kg) was administered orally to the Fam+IND (n=6) group using the same method. Distilled water was given orally to the HC (n=6) and IND (n=6) groups as a solvent. One hour after the drugs and distilled water were administered, indomethacin was administered to all rat groups (except HC) at a dose of 20 mg/kg using the same method. Six hours after indomethacin administration, all animals were sacrificed with high-dose (50 mg/kg) thiopental anesthesia, and their stomachs were removed. The inner surface of the removed stomach was evaluated macroscopically. The width of the ulcer areas was determined using a magnifying glass and millimeter paper [7]. Afterward, stomach tissues were biochemically examined.

Biochemical analysis

Preparation of samples: After gastric tissue samples were washed with physiological saline, they were pulverized in liquid nitrogen and homogenized. Supernatants were used for analysis.

Malondialdehyde (MDA), total glutathione (GSH), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and protein determination: Detection of SOD, GSH, and MDA in gastric tissues was performed with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (product nos. 706002, 703002, and 10009055, respectively; Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI, USA). CAT determination was made according to the method proposed by Goth [17]. Protein determination was determined spectrophotometrically at 595 nm according to the Bradford method [18].

Measurement of COX activity: Gastric tissue COX levels were measured using a COX activity analysis kit (item no. 760151; Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Tissues were thoroughly washed with Tris buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.16 mg/ml heparin and then stored at −80°C until analysis. Tissue was homogenized in 5 ml of cold buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM EDTA) per gram and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The protein concentration in the supernatant was then measured using the Bradford method. The COX activity analysis kit measures the peroxidase activity of COX. This is tested colorimetrically by monitoring the appearance of oxidized N, N, N’, N’-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine at 590 nm. COX-2 activity was determined using the COX-1-specific inhibitor [19]. Results for COX-1 and COX-2 activity are given in units per milligram of protein. COX activity in tissue was expressed as nmol/min/mg protein (U/mg protein).

Statistical analysis: IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0, released 2013 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. The results are presented as mean ± SD. The significance of differences between the groups was determined using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test followed by Tukey’s analysis. The statistical level of significance for all tests was considered to be <0.05.

Results

Biochemical findings

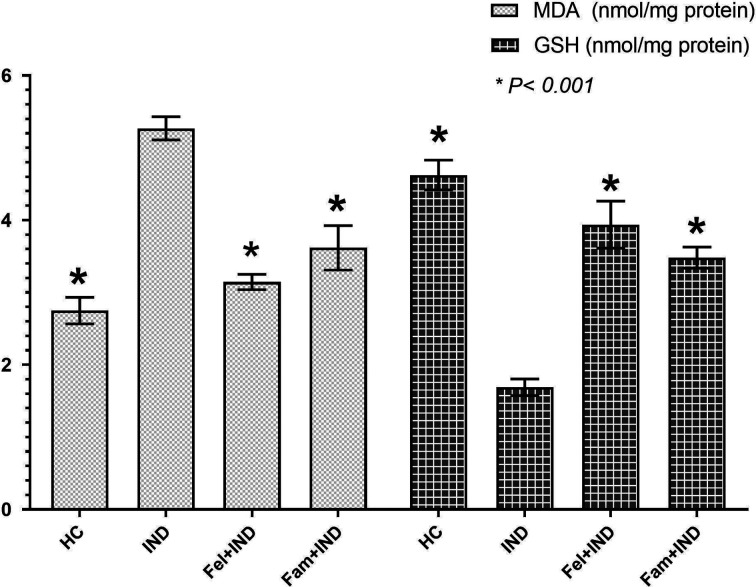

As can be seen in Table 1, the amount of MDA in the gastric tissue of rats in the IND group was significantly increased compared with the HC, Fel+IND, and Fam+IND groups, whereas the amounts of GSH, SOD, and CAT were found to be lower (Figs. 1 and 2). There was also a statistically significant difference between the HC and Fel+IND and HC and Fam+IND groups in terms of MDA, GSH, SOD, and CAT levels (Table 1).

Table 1. Biochemical findings in the groups.

| Parameters | HC Group | IND Group | Fel+IND Group | Fam+IND Group | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA (nmol/mg protein) | 2.75 ± 0.18a | 5.27 ± 0.16b | 3.15 ± 0.11a,c | 3.62 ± 0.31a,b | <0.001 |

| GSH (nmol/mg protein) | 4.62 ± 0.21a | 1.69 ± 0.12b | 3.94 ± 0.33a,b | 3.48 ± 0.15a,b | <0.001 |

| SOD (u/mg protein) | 7.22 ± 0.16a | 3.43 ± 0.11b | 6.51 ± 0.12a,b | 6.17 ± 0.33a,b | <0.001 |

| CAT (u/mg protein) | 6.85 ± 0.10a | 3.16 ± 0.15b | 6.37 ± 0.51a,c | 6.10 ± 0.08a,c | <0.001 |

| COX-1 (u/mg protein) | 5.16 ± 0.06a | 1.67 ± 0.22b | 4.72 ± 0.24a,c | 3.99 ± 0.35a,b | <0.001 |

| COX-2 (u/mg protein) | 0.27 ± 0.05a | 0.12 ± 0.02b | 0.15 ± 0.03b | 0.27 ± 0.043a | <0.001 |

| Number of Ulcers (n) | 0.00 ± 0.00a | 18.5 ± 1.87b | 2.00 ± 0.89a,c | 3.00 ± 1.27a,b | <0.001 |

| Ulcerated Area (mm2) | 0.00 ± 0.00a | 40.67 ± 2.50b | 0.55 ± 0.19a | 0.73 ± 0.16a | <0.001 |

HC: healthy control group; IND: indomethacin group; Fel+IND: felodipine + indomethacin group; Fam+IND: famotidine + indomethacin group; MDA: malondialdehyde; GSH: glutathione; SOD: superoxide dismutase; CAT: catalase; COX-1: cyclooxygenase-1; COX-2: cyclooxygenase-2. aStatistically significant difference of the groups in comparison to the IND group (P<0.001). bStatistically significant difference of the groups in comparison to the HC group (P<0.001). cStatistically significant difference of the groups in comparison to the HC group (P<0.05).

Fig. 1.

MDA and GSH levels of the groups. HC: healthy control group; IND: indomethacin group; Fel+IND: felodipine + indomethacin group; Fam+IND: famotidine + indomethacin group; MDA: malondialdehyde; GSH: glutathione. * Statistically significant difference of the groups in comparison to the IND group (P<0.001).

Fig. 2.

SOD and CAT levels of the groups. HC: healthy control group; IND: indomethacin group; Fel+IND: felodipine + indomethacin group; Fam+IND: famotidine + indomethacin group; SOD: superoxide dismutase; CAT: catalase. * Statistically significant difference of the groups in comparison to the IND group (P<0.001).

Between the Fel+IND and Fam+IND groups, there was a statistically significant difference in terms of MDA (P=0.003), GSH (P=0.007) and SOD (P=0.036). However, there was no significant difference in terms of CAT levels (P=0.312).

Tissue COX-1 and COX-2 activity

As presented in Table 1, COX-1 activity in the gastric tissue of rats in the IND group was significantly decreased compared with the HC, Fel+IND, and Fam+IND groups (Fig. 3). There was also a statistically significant difference in COX-1 activity between the HC and Fel+IND and HC and Fam+IND groups (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

COX-1 levels of the groups. HC: healthy control group; IND: indomethacin group; Fel+IND: felodipine + indomethacin group; Fam+IND: famotidine + indomethacin group; COX-1: cyclooxygenase-1. * Statistically significant difference of the groups in comparison to the IND group (P<0.001).

Whereas COX-2 activity in the gastric tissue of rats in the IND group was significantly decreased compared with the HC and Fam+IND groups, no statistically significant difference was found between the IND and Fel+IND groups (Table 1, Fig. 4). There was also a statistically significant difference in COX-2 activity between the HC and Fel+IND groups. There was no statistically significant difference between the HC and Fam+IND groups in terms of COX-2 activity (Table 1). However, there was a statistically significant difference between the Fel+IND and Fam+IND groups in terms of both COX-1 (P<0.001) and COX-2 activity (P<0.001).

Fig. 4.

COX-2 levels of the groups. HC: healthy control group; IND: indomethacin group; Fel+IND: felodipine + indomethacin group; Fam+IND: famotidine + indomethacin group; COX-2: cyclooxygenase-2. * Statistically significant difference of the groups in comparison to the IND group (P<0.001).

Evaluation of gastric ulcers

Gastric lesions in the groups were evaluated by the number of ulcers and ulcerated areas (Figs. 5a–d). The number of ulcers in the IND group was found to be significantly higher than in the HC, Fel+IND, and Fam+IND groups (Table 1, Fig. 6). There was also a statistically significant difference in the number of ulcers between the HC and Fel+IND and HC and Fam+IND groups (Table 1). Similarly, the ulcerated area measured in the IND group was significantly increased compared with the HC, Fel+IND, and Fam+IND groups (Table 1, Fig. 7). However, no statistically significant difference was found between the HC and Fel+IND and HC and Fam+IND groups (Table 1). Additionally, no statistical difference was observed between the Fel+IND and Fam+IND groups in terms of the number of ulcers (P=0.498) and the ulcer area (P=0.994).

Fig. 5.

Macroscopic photographs of rats’ stomachs. (a) Gastric tissue of the HC group, mucosa with no lesion or redness. (b) Gastric tissue of the IND group, severely hemorrhagic ulcerated mucosa surface. (c) Gastric tissue of the Fel+IND group, minor injuries with normal mucosa. (d) Gastric tissue of the Fam+IND group, minor injuries with normal mucosa. HC: healthy control group; IND: indomethacin group; Fel+IND: felodipine + indomethacin group; Fam+IND: famotidine + indomethacin group.

Fig. 6.

Number of ulcers in groups. HC: healthy control group; IND: indomethacin group; Fel+IND: felodipine + indomethacin group; Fam+IND: famotidine + indomethacin group. * Statistically significant difference of the groups in comparison to the IND group (P<0.001).

Fig. 7.

Ulcerated areas in groups. HC: healthy control group; IND: indomethacin group; Fel+IND: felodipine + indomethacin group; Fam+IND: famotidine + indomethacin group. *Statistically significant difference of the groups in comparison to the IND group (P<0.001).

Discussion

NSAIDs are widely used in the treatment of painful and inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. These agents suppress PG synthesis by inhibiting the COX enzyme [4, 5]. However, NSAID use is associated with gastrointestinal complications such as mucosal lesions, bleeding, and peptic ulcer formation [6, 7]. In this study, the antiulcer effect of felodipine was investigated using an indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer model in rats. Our experimental results showed that indomethacin caused significant ulceration in gastric mucosa, which was consistent with the literature. It was observed that felodipine suppressed indomethacin-induced MDA increase, reduced the decrease in GSH amount, reduced the decrease in SOD and CAT activities, and significantly inhibited ulcers at the tested dose. In this experiment, felodipine at a dose of 5 mg/kg reduced the indomethacin-induced decrease in COX-1 activity but did not cause a significant reduction in the decrease in COX-2 activity.

The selective COX-2 inhibitor nimesulide is known to prevent NSAID-induced ulcers, whereas celecoxib and rofecoxib, which are more selective to COX-2, cannot prevent these ulcers [20]. These data suggest that the gastrointestinal adverse effects of classical NSAIDs cannot be associated with COX-1 inhibition alone. The literature states that an increase in toxic oxidants and a defect in the antioxidant system may play an important role in the occurrence of gastric damage due to indomethacin [21].

The effects of indomethacin on MDA, GSH, SOD, and CAT levels in the gastric tissue of animals in our study indicate that indomethacin causes oxidative stress by changing the oxidant/antioxidant balance in the gastric tissue in favor of oxidants. Oxidative stress has been defined as “an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants in favor of oxidants” and leads to dysregulation in redox signaling and control, as well as biological damage at the molecular level [22]. The findings of the current study suggest that the group administered indomethacin alone consumed antioxidants to neutralize ROS in the gastric tissue, which indicates that oxidative damage develops in the gastric tissue.

Excessive increases in ROS production cause lipid peroxidation (LPO). MDA is one of the most frequently researched, reliable, and popular products of oxidative stress and LPO. An increase in MDA is associated with biological damage, and a decrease is associated with protection [23,24,25]. In the current study, the increase in the amount of MDA in the gastric tissue of animals administered indomethacin is consistent with the literature and indicates oxidative stress [21, 26].

In addition, in the gastric tissue of animals administered indomethacin, GSH levels were decreased. GSH is a tripeptide compound consisting of glutamate, cysteine, and glycine and contains an active thiol group that can be easily oxidized and dehydrogenated. In this way, GSH is an antioxidant molecule that provides electrons for antioxidant enzymes and eliminates and cleans ROS [24, 27]. GSH protects gastrointestinal tissue lipids from oxidative damage. Many studies have reported that the GSH level decreases in gastric tissue damaged by indomethacin [21, 28]. The reduction in indomethacin-related GSH decrease observed in this study in the groups treated with felodipine and famotidine is consistent with the macroscopic findings and the literature.

Another member of the system that forms the first line of defense against oxidative stress is SOD. SOD catalyzes the dismutation of the superoxide anion radical to hydrogen peroxide. The hydrogen peroxide, which is an oxidant molecule, is then converted to water and oxygen by CAT or glutathione peroxidase [29]. In our study, SOD activity was significantly lower in the gastric tissue of animals administered indomethacin. The felodipine significantly reduced the decrease in SOD activity, similar to famotidine. According to the literature, SOD activity is lowest in damaged tissue and highest in healthy tissue [29]. In addition, the relationship between SOD activity and PG synthesis has been considered in the literature, and it has been stated that this relationship may be a possible mechanism of indomethacin-induced ulcers [30].

CAT is an enzyme found in peroxisomes that catalyzes the formation of water and molecular oxygen from hydrogen peroxide. In our study, administration of indomethacin decreased SOD and GSH as well as CAT activity. The decrease in CAT activity has been attributed to the overproduction of radicals that are substrates for this enzyme and the high consumption of the enzyme. Studies in gastric ulcer models support this information [31]. In our study, felodipine significantly reduced the decrease in CAT activity, similar to famotidine.

Felodipine has been reported to decrease LPO and MDA levels in various tissues in human and animal studies while increasing the effectiveness of antioxidants such as GSH, SOD, and CAT [32,33,34]. Antioxidant effects of CCBs have been observed, especially in CCBs with highly lipophilic chemical structures [35]. In the literature, it has been reported that felodipine reduces inflammation, in addition to its positive effects on oxidants and antioxidants [33, 34]. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNLs) play an important role in the development of inflammation and tissue damage by releasing ROS and various inflammatory mediators. The increase in intracellular calcium is responsible for the activation of PMNLs. Researchers have suggested that activated PMNLs have a role in the pathogenesis of indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers [36]. The positive effects of felodipine on PMNL activation and inflammatory markers may play a role in its antiulcer activity. The relationship between oxidative stress and inflammation is also known. Oxidative stress activates inflammatory markers, and inflammation and inflammatory markers induce ROS production [37, 38]. In addition, it has been stated that inflammation is associated with intracellular calcium level [39]. This information obtained from the literature supports our experimental results demonstrating the antiulcer efficacy of felodipine.

Felodipine inhibited indomethacin-induced reduction in COX-1 activity. However, it failed to prevent indomethacin-induced reduction of COX-2. COX-1 is a structural enzyme found in tissues and cells, producing protective PGs, responsible for maintaining normal cellular functions [3,4,5]. Suppression of COX-1 activity may result in decreased PG synthesis, which may damage the gastric mucosal barrier. We did not find any studies revealing the effect of felodipine on the COX enzyme in gastric tissue. However, in studies with other calcium channel blockers, findings consistent with our results revealing the relationship of felodipine with COX-1 and COX-2 have been reported [28]. In addition, it has been suggested that calcium channel blockers inhibit gastric basal and stimulated acid secretion and gastric motility and protect the gastric mucosa by increasing gastric blood flow [40].

Our study has some limitations. The histopathological effects of felodipine in gastric tissue and how felodipine affects proinflammatory cytokine levels were not evaluated. Evaluation of these parameters could have contributed to the study.

Indomethacin caused significant oxidative damage in gastric tissue and changed the oxidant and antioxidant balance in favor of oxidants. It also significantly reduced COX-1 activity. Felodipine prevented the development of indomethacin-induced oxidative stress. In addition, it reduced the indomethacin-induced decrease in COX-1 enzyme activity. However, it had no effect on COX-2 enzyme activity. These data suggest that felodipine may be useful in the treatment of NSAID-induced gastric injury. More detailed studies are needed in the future to clarify the antiulcer mechanism of action of felodipine.

References

- 1.Svoboda R, Koutná N, Košťálová D, Krbal M, Komersová A. Indomethacin: Effect of Diffusionless Crystal Growth on Thermal Stability during Long-Term Storage. Molecules. 2023; 28: 1568. doi: 10.3390/molecules28041568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Summ O, Evers S. Mechanism of action of indomethacin in indomethacin-responsive headaches. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013; 17: 327. doi: 10.1007/s11916-013-0327-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bokhtia RM, Panda SS, Girgis AS, Samir N, Said MF, Abdelnaser A, et al. New NSAID Conjugates as Potent and Selective COX-2 Inhibitors: Synthesis, Molecular Modeling and Biological Investigation. Molecules. 2023; 28: 1945. doi: 10.3390/molecules28041945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdellatif KRA, Abdelall EKA, Elshemy HAH, El-Nahass ES, Abdel-Fattah MM, Abdelgawad YYM. New indomethacin analogs as selective COX-2 inhibitors: Synthesis, COX-1/2 inhibitory activity, anti-inflammatory, ulcerogenicity, histopathological, and docking studies. Arch Pharm (Weinheim). 2021; 354: e2000328. doi: 10.1002/ardp.202000328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Süleyman H, Demircan B, Karagöz Y. Anti-inflammatory and side effects of cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Pharmacol Rep. 2007; 59: 247–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albayrak A, Polat B, Cadirci E, Hacimuftuoglu A, Halici Z, Gulapoglu M, et al. Gastric anti-ulcerative and anti-inflammatory activity of metyrosine in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 2010; 62: 113–119. doi: 10.1016/S1734-1140(10)70248-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dengiz GO, Odabasoglu F, Halici Z, Suleyman H, Cadirci E, Bayir Y. Gastroprotective and antioxidant effects of amiodarone on indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers in rats. Arch Pharm Res. 2007; 30: 1426–1434. doi: 10.1007/BF02977367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abu-Amra E, Abd-EL Rehim SA, Lashein FM, Seleem AA, Shoaeb HSI. The protective role of bradykinin potentiating factor on gastrointestinal ulceration induced by indomethacin in experimental animals. Int J Adv Res (Indore). 2015; 3: 311–322. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szabo S, Trier JS, Brown A, Schnoor J. Early vascular injury and increased vascular permeability in gastric mucosal injury caused by ethanol in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1985; 88: 228–236. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(85)80176-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalogeris T, Baines CP, Krenz M, Korthuis RJ. Cell biology of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2012; 298: 229–317. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394309-5.00006-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi H, Chaiyamongkol W, Doolittle AC, Johnson ZI, Gogate SS, Schoepflin ZR, et al. COX-2 expression mediated by calcium-TonEBP signaling axis under hyperosmotic conditions serves osmoprotective function in nucleus pulposus cells. J Biol Chem. 2018; 293: 8969–8981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yazaki M, Kashiwagi K, Aritake K, Urade Y, Fujimori K. Rapid degradation of cyclooxygenase-1 and hematopoietic prostaglandin D synthase through ubiquitin-proteasome system in response to intracellular calcium level. Mol Biol Cell. 2012; 23: 12–21. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e11-07-0623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bansal AB, Khandelwal G. Felodipine. Treasure Island: StatPearls: 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhein S, Salameh A, Berkels R, Klaus W. Dual mode of action of dihydropyridine calcium antagonists: a role for nitric oxide. Drugs. 1999; 58: 397–404. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958030-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandhi H, Patel VB, Mistry N, Patni N, Nandania J, Balaraman R. Doxorubicin mediated cardiotoxicity in rats: protective role of felodipine on cardiac indices. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2013; 36: 787–795. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2013.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi J, Zheng JB, Ai WT, Yao XW, Liang L, Cheng G, et al. Felodipine inhibits ox-LDL-induced reactive oxygen species production and inflammation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Mol Med Rep. 2017; 16: 4871–4878. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Góth L. A simple method for determination of serum catalase activity and revision of reference range. Clin Chim Acta. 1991; 196: 143–151. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(91)90067-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976; 72: 248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulmacz RJ, Lands WE. Requirements for hydroperoxide by the cyclooxygenase and peroxidase activities of prostaglandin H synthase. Prostaglandins. 1983; 25: 531–540. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(83)90025-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suleyman H, Cadirci E, Albayrak A, Halici Z. Nimesulide is a selective COX-2 inhibitory, atypical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Curr Med Chem. 2008; 15: 278–283. doi: 10.2174/092986708783497247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albayrak A, Alp HH, Suleyman H. Investigation of antiulcer and antioxidant activity of moclobemide in rats. Eurasian J Med. 2015; 47: 32–40. doi: 10.5152/eajm.2014.0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sies H, Berndt C, Jones DP. Oxidative Stress. Annu Rev Biochem. 2017; 86: 715–748. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-045037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsikas D. Assessment of lipid peroxidation by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) and relatives in biological samples: Analytical and biological challenges. Anal Biochem. 2017; 524: 13–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2016.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akbaş N, Suleyman B, Mammadov R, Yazıcı GN, Bulut S, Süleyman H. Effect of taxifolin on cyclophosphamide-induced oxidative and inflammatory bladder injury in rats. Exp Anim. 2022; 71: 460–467. doi: 10.1538/expanim.22-0030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gursul C, Ozcicek A, Ozkaraca M, Mendil AS, Coban TA, Arslan A, et al. Amelioration of oxidative damage parameters by carvacrol on methanol-induced liver injury in rats. Exp Anim. 2022; 71: 224–230. doi: 10.1538/expanim.21-0143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumtepe Y, Borekci B, Karaca M, Salman S, Alp HH, Suleyman H. Effect of acute and chronic administration of progesterone, estrogen, FSH and LH on oxidant and antioxidant parameters in rat gastric tissue. Chem Biol Interact. 2009; 182: 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forman HJ, Zhang H, Rinna A. Glutathione: overview of its protective roles, measurement, and biosynthesis. Mol Aspects Med. 2009; 30: 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altuner D, Kaya T, Suleyman H. The protective effect of lercanidipine on indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers in rats. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2020; 63: e20190311. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Branicky R, Noë A, Hekimi S. Superoxide dismutases: Dual roles in controlling ROS damage and regulating ROS signaling. J Cell Biol. 2018; 217: 1915–1928. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201708007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Missiry MA, El-Sayed IH, Othman AI. Protection by metal complexes with SOD-mimetic activity against oxidative gastric injury induced by indomethacin and ethanol in rats. Ann Clin Biochem. 2001; 38: 694–700. doi: 10.1258/0004563011900911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.da Silva DM, Martins JLR, de Oliveira DR, Florentino IF, da Silva DPB, Dos Santos FCA, et al. Effect of allantoin on experimentally induced gastric ulcers: Pathways of gastroprotection. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018; 821: 68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.12.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai CL, Xing ZH, Li MY, Tan HY, Zhang C. Effect of felodipine on lipid peroxidation damage in patients with hypertension. 2004; 8: 8230–8231. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Majeed ML, Ismael SH, Mahdi LH. The hypolipidemic effect of felodipine and its ability to improves atherosclerosis induced in experimental rabbits. Pharm Glob. 2015; 6: 1. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swayeh NH, Abu-Raghif AR, Qasim BJ. The protective effects of felodipine on methotrexate-induced hepatic toxicity in rabbits. Iraqi J Med Sci. 2016; 14: 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Godfraind T. Antioxidant effects and the therapeutic mode of action of calcium channel blockers in hypertension and atherosclerosis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005; 360: 2259–2272. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murakami K, Okajima K, Harada N, Isobe H, Liu W, Johno M, et al. Plaunotol prevents indomethacin-induced gastric mucosal injury in rats by inhibiting neutrophil activation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999; 13: 521–530. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00481.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumari N, Dwarakanath BS, Das A, Bhatt AN. Role of interleukin-6 in cancer progression and therapeutic resistance. Tumour Biol. 2016; 37: 11553–11572. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5098-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han F, Li S, Yang Y, Bai Z. Interleukin-6 promotes ferroptosis in bronchial epithelial cells by inducing reactive oxygen species-dependent lipid peroxidation and disrupting iron homeostasis. Bioengineered. 2021; 12: 5279–5288. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.1964158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Didion SP. Cellular and oxidative mechanisms associated with interleukin-6 signaling in the vasculature. Int J Mol Sci. 2017; 18: 2563. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nielsen ST, Sulkowski TS. Protection by the calcium antagonist Wy-47,037 against stress ulceration in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988; 29: 129–132. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90285-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]