Abstract

Objective

Oral health is intricately linked with systemic health. However, the knowledge and practice levels of medical practitioners (MPs) about this concern are extremely variable. The current study, therefore, sought to assess the status of knowledge and practice of MPs concerning the link between periodontal disease and different systemic conditions as well as the efficacy of a webinar as an interventional tool in enhancing knowledge of MPs of Jazan Province of Saudi Arabia.

Methods

This prospective interventional study involved 201 MPs. A 20-item questionnaire on evidence-based periodontal/systemic health associations was used. The participants answered the questionnaire before and 1 month after a webinar training that explained the mechanistic interrelation of periodontal and systemic health. McNemar test was performed for statistical analysis.

Results

Out of the 201 MPs who responded to the pre-webinar survey, 176 attended the webinar and hence were included in the final analyses. Sixty-eight (38.64%) were female, and 104 (58.09%) were older than 35 years. About 90% of MPs reported not being trained on oral health. Pre-webinar, 96 (54.55%), 63 (35.80%), and 17 (9.66%) MPs rated their knowledge about the association of periodontal disease with systemic diseases as limited, moderate, and good, respectively. Post-webinar, these figures improved remarkably: 36 (20.45%), 88 (50.00%), and 52 (29.55%) MPs rated their knowledge as limited, moderate, and good, respectively. Around 64% of MPs had relatively good levels of knowledge about the positive influence of periodontal disease treatment on diabetic patients’ blood glucose levels.

Conclusions

MPs revealed low levels of knowledge on the oral and systemic disease interrelationship. Conducting webinars on the oral–systemic health interrelationship seems to improve the overall knowledge and understanding of MPs.

Key words: Periodontal disease, Systemic disease, Medical practitioners, Webinar study

Introduction

Good oral health status is an essential part of general systemic health, as it can affect one's overall quality of life drastically.1 The World Health Organization states that understanding the link between oral diseases and general health is essential for all medical professionals and that they should play a significant role in diagnosing patients and referring them to dental professionals.2

Periodontal disease (PD) is a bacterial infection of the tooth-supporting structures associated with a host-mediated inflammatory process that ultimately leads to loss of periodontal attachment, unless treated in a proper and timely manner.3 The Global Burden of Disease Study (2016) ranked severe PD as the 11th most prevalent disease worldwide.4 The overall prevalence of PD ranges from 20% to 50%.5 PD is the key leading cause of tooth loss, an impairment that has substantial impact on chewing, nutritional intake, appearance, general health, self-esteem, and quality of life.6 Mounting evidence indicates that PD is associated with systemic diseases. It is thought that PD causes severe impairment of the host's defensive response,7 and accordingly the diagnosis and treatment of PD will help halt the progression of systemic disease as per International Statistical Classification of Disease (ICD).8,9

A plethora of literature has suggested that PD is a possible risk factor underlying various systemic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases,10, 11, 12, 13 rheumatoid arthritis,14 cerebrovascular diseases,15 diabetic mellitus,16,17 obesity,18,19 preterm birth along with low birth weight,20,21 and erectile dysfunction.22 Quite the opposite, but confirming said interrelationship, various studies have found a high prevalence of PD amongst patients who have liver diseases,23 chronic renal failure,24 osteoporosis,25 and various psychiatric disorders.26,27

A recent Cochrane review demonstrates that periodontal intervention can reduce blood glucose levels in diabetic patients28 and adverse pregnancy outcomes.29Periodontal treatment seems to improve endothelial function, decrease atherosclerosis biomarkers, and reduce inflammatory burden; those who do not respond to periodontal treatment have an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease.30

Medical professionals (MPs) might play a pivotal role in promoting oral hygiene amongst their patients. They can disseminate oral health–related information amongst their patients, aiming to encourage them to follow good dental health care regimens. In order to do so, MPs first have to acquire the needed knowledge about oral health and its potential effects on general health and then convert this knowledge into a daily practice of patient education.31, 32, 33, 34 In light of the foregoing, an immediate need exists to assess the level of knowledge and comprehension of this problem amongst MPs in order to develop an integrated practice structure for the prevention and effective management of PD and its systemic consequences.

This issue requires an immediate educational campaign and communication to bridge the gap between dentists and MPs, promote patients’ health, and avoid serious complications.34 Webinars are recognised as an effective tool for interaction between disciplines and are crucial in health education, disease prevention, and clinical counselling.35 No study has, to our knowledge, been organised in the Jazan region of Saudi Arabia that evaluated and enhanced the knowledge of MPs through a webinar-based educational training programme. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the knowledge of MPs regarding the relationship between periodontal and systemic diseases as well as the efficacy of a webinar as an interventional tool in enhancing knowledge and understanding amongst them.

Materials and methods

Population

The study was of interventional design and targeted all licensed MPs of different government or private sectors working in Jazan Province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The Jazan University Standing Committee (REC42/1/079, HAPO-10-Z-001) on the Ethics of Scientific Research approved the study, and the principles of the Helsinki Declaration were followed.

Development of the questionnaire

The questionnaire was modified from previously published questionnaires on the association between PD and systemic conditions.33,34,36 The questionnaire was drafted in English and included an introduction detailing the purpose and design of the study and the email contact of the researcher, in case of any query and/or need for clarification, in addition to a clear statement ensuring the confidentiality of the data and indicating that participation is voluntarily. It was structured as a closed-ended questionnaire covering the following: first, the participants’ age, sex, education level, specialties, and number of years in practice, as well as their demographic information and email for subsequent communication regarding the planned webinar; second, questions on knowledge of the medical professionals on the interrelationship of PD and systemic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disorders, osteoarthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus and about their knowledge pertaining to periodontal treatment and its impact on preterm delivery and low birth weight (see Table 2); third, a section addressing the oral health advice practices of professionals, including the significance of regular dental checkups, screening, and referral to a dentist; and, fourth, a question about whether the professionals are comfortable in performing an oral examination.

Table 2.

Medical practitioners’ knowledge responses in both pre-webinar and post-webinar questionnaire survey.

| Question | Response | Pre-webinar responses, No. (%) | Post-webinar responses, No. (%) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you think that gum bleeding, recession of gums and tooth loss signs and symptoms of PD? | Don't know | 8 (4.55) | 1 (0.57) | .045 |

| No | 10 (5.68) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Yes | 158 (89.77) | 175 (99.43) | ||

| Do you believe PD worsen diabetes mellitus? | Don't know | 10 (5.68) | 0 (0.00) | >.05 |

| No | 11 (6.25) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Yes | 155 (88.07) | 176 (100) | ||

| Is active PD have an influence on the diabetic patient glucose level? | Don't know | 29 (16.48) | 11 (6.25) | >.05 |

| No | 7 (3.98) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Yes | 140 (79.55) | 165 (93.75) | ||

| Do you believe periodontal therapy affect the diabetic patient's blood sugar levels? | Don't know | 49 (27.84) | 12 (6.82) | <.001 |

| No | 15 (8.52) | 4 (2.27) | ||

| Yes | 112 (63.64) | 160 (90.91) | ||

| Can periodontitis be regarded as a distinct risk factor for myocardial infarction. | Don't know | 68 (38.64) | 17 (9.7) | <.001 |

| No | 52 (29.55) | 5 (2.8) | ||

| Yes | 56 (31.82) | 154 (87.5) | ||

| Is periodontal therapies effective in lowering systemic inflammatory markers? | Don't know | 52 (29.55) | 17 (9.66) | <.001 |

| No | 16 (9.09) | 5 (2.84) | ||

| Yes | 108 (61.36) | 154 (87.50) | ||

| Do you think that pregnant women with active PD have a higher risk of having babies born prematurely and with low birth weight? | Don't know | 112 (63.64) | 26 (14.77) | <.001 |

| No | 22 (12.50) | 6 (3.41) | ||

| Yes | 42 (23.86) | 144 (81.82) | ||

| Is it safe to have elective dental procedures performed during the second trimester of pregnancy? | Don't know | 55 (31.25) | 2 (1.14) | <.001 |

| No | 27 (15.34) | 7 (3.98) | ||

| Yes | 94 (53.41) | 167 (94.89) | ||

| Are you concerned that PD could lead to an early death? | Don't know | 127 (72.16) | 31 (17.61) | <.001 |

| No | 10 (5.68) | 5 (2.84) | ||

| Yes | 39 (22.16) | 140 (79.55) | ||

| Is there evidence linking PD to an increased risk of autoimmune diseases like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis? | Don't know | 84 (47.73) | 32 (18.18) | <.001 |

| No | 35 (19.89) | 12 (6.82) | ||

| Yes | 57 (32.39) | 132 (75.00) | ||

| Are there any oral consequences of obesity and metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents? | Don't know | 112 (63.64) | 8 (4.55) | <.001 |

| No | 7 (3.98) | 2 (1.14) | ||

| Yes | 57 (32.39) | 166 (94.32) | ||

| Do you think anxiety and depression may contribute to the risk of oral disease? | Don't know | 124 (70.45) | 16 (9.10) | <.001 |

| No | 5 (2.84) | 3 (1.70) | ||

| Yes | 47 (26.71) | 157 (89.20) | ||

| Is there an association between PD and chronic renal failure patients? | Don't know | 113 (64.20) | 47 (26.70) | <.001 |

| No | 15 (8.52) | 6 (3.41) | ||

| Yes | 48 (27.27) | 123 (69.89) | ||

| Do you believe PD plays a role in carcinogenesis of the head and neck region? | Don't know | 111 (63.07) | 57 (32.39) | <.001 |

| No | 5 (2.84) | 4 (2.27) | ||

| Yes | 60 (34.09) | 115 (65.34) | ||

| How well-informed are you about PD and its connection to other underlying illnesses? | Limited | 96 (54.55) | 36 (20.45) | <.001 |

| Moderate | 63 (35.80) | 88 (50.00) | ||

| Good | 17 (9.66) | 52 (29.55) |

McNemar test was applied with a P value <.05 and was considered statistically significant.

PD, periodontal disease.

Dissemination of the pre-webinar questionnaire

A link to a Google Form for the said self-administered questionnaire was disseminated by the authors and their friends who were MPs working in Jazan region via online social media such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. In addition, the same link was sent to members of the Saudi Medical Society via email. (MOH) in the Jazan region. Reminders via the same channels were sent 1 and 2 weeks later.

Conducting the webinar

Two weeks after the last reminder, and after the data of the pre-intervention questionnaire were collected, a webinar was conducted. Briefly, the participants who responded to the pre-intervention questionnaire were invited to participate via email in a webinar (via Zoom link) for 1 hour on the interrelationship between PD and systemic diseases. The webinar material was prepared by 2 of the authors (SP and MA). The webinar was in the form of a PowerPoint presentation and highlighted the significance of the bidirectional relationship between oral and systemic health, with special emphasis on PD, based on updated published evidence. The webinar clarified many doubts related to the bidirectional link between systemic and PD.

Dissemination of the post-webinar questionnaire

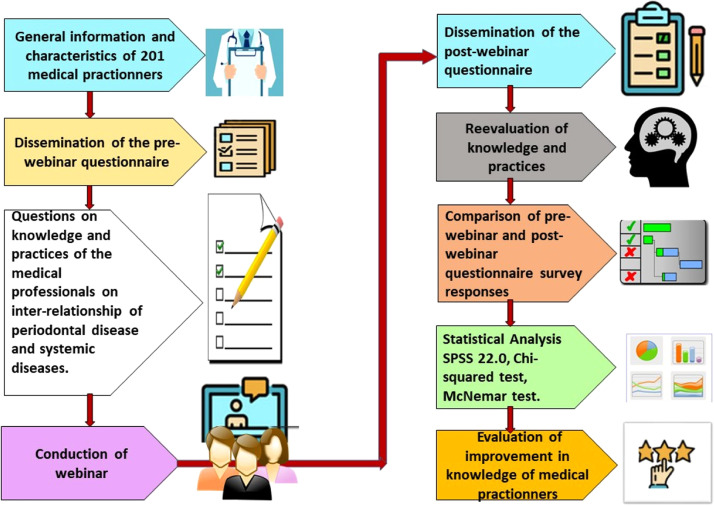

One month after the interactive webinar, all participants who attended were emailed the link to the same questionnaire. The matching of the responses of the pre- and post-webinar questionnaires was done based on the reported email. The study layout is explained in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Study layout.

Statistical analysis

The data of the pre- and post-webinar responses were obtained as a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, from which they were imported into a statistical programme. Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 22.0 (IBM Corp.). For each stage of the study, the Chi-squared test was applied to assess the association of the obtained knowledge with different variables. For the paired data (pre and post), the comparison was done using the McNemar test.

Results

After dissemination and 2 reminders, 201 medical professionals responded to the pre-webinar questionnaire. Of them, 176 attended the webinar and responded to the post-webinar questionnaire. Out of the 201 respondents to the pre-webinar questionnaire, 62% were male and 38% were female. Approximately similar proportions (61% and 39%, respectively) attended the webinar and completed the post-webinar questionnaire. With regard to the age groups (<25, 25–35, 36–45, and 46–60 years), the participants were distributed as 8.46%, 30.85%, 24.38%, and 36.32%, respectively, in the pre-webinar questionnaire, and as 9.66%, 31.25%, 21.59%, and 37.50%, respectively, in the post-webinar questionnaire. Ninety participants (44.78%) in the pre-webinar questionnaire were Saudi, and the remaining 111 (55.22%) were non-Saudi. The corresponding figures in the post-webinar were 81 (46.02%) and 95 (53.98%) Saudi and non-Saudi, respectively.

Work experience was categorised as <2 years, >2 to 5 years, >5 to 10 years, and >10 years, and the reported proportions by the respondents to the pre-webinar questionnaire were 12.94%, 5.47%, 45.27%, and 36.32%, respectively, whilst the proportions in the post-webinar questionnaire were 13.64%, 5.68%, 44.89%, and 35.80%, respectively. About 16.42%, 54.23%, and 29.35 of the participants reported working at private, government, and teaching institutes, respectively. These proportions did not change markedly in the post-webinar questionnaire (15.91%, 52.27%, and 31.82% ,respectively). The general practitioners, specialists, and consultants represented 21.39%, 48.26%, and 30.35%, respectively. These proportions did not markedly change in the post-webinar questionnaire (21.59%, 49.43%, and 28.98%, respectively). Only 21 (10.45%) of the pre-webinar participants reported receiving training on periodontal/oral health in school. The figures did not markedly change in the post-webinar questionnaire (18 [10.23%]; Table 1).

Table 1.

General information and characteristics of participants.

| Variable | Respondents to the pre-webinar survey, No. (%) (N = 201) | Respondents to post-webinar surveys, No. (%) (N = 176) |

|---|---|---|

| Age groups, y | ||

| ≤25 | 17 (8.46) | 17 (9.66) |

| 25–35 | 62 (30.85) | 55 (31.25) |

| 36–45 | 49 (24.38) | 38 (21.59) |

| 56–60 | 73 (36.32) | 66 (37.50) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 125 (62.19) | 108 (61.36) |

| Female | 76 (37.81) | 68 (38.64) |

| Nationality | ||

| Saudi | 90 (44.78) | 81 (46.02) |

| Non-Saudi | 111 (55.22) | 95 (53.98) |

| Years of experience | ||

| ≤2 | 26 (12.94) | 24 (13.64) |

| >2–5 | 11 (5.47) | 10 (5.68) |

| > 5–10 | 91 (45.27) | 79 (44.89) |

| >10 | 76 (36.32) | 63 (35.84) |

| Place of work | ||

| Private | 33 (16.42) | 28 (15.9) |

| Government | 109 (54.23) | 92 (52.27) |

| Teaching institute | 59 (29.35) | 56 (31.82) |

| Professional Degree | ||

| General Practitioner | 43 (21.39) | 38 (21.59) |

| Specialist | 97 (48.26) | 87 (49.43) |

| Consultant | 61 (30.35) | 51 (29.98) |

| Receiving training on periodontal/oral health in medical school | ||

| Yes | 21 (10.45) | 18 (10.23) |

| No | 180 (89.55) | 158 (89.77) |

Table 2 presents detailed comparisons of pre- and post-webinar responses to the knowledge questions. The knowledge improved in all questions, but the improvement was significant in 12 out of 15 questions. Uncertainty (“don't know” response) dominated in the pre-webinar responses. In the post-webinar questionnaire, the responses revealed good knowledge; such uncertainty was dispelled. Significantly, fewer MPs in the pre-webinar questionnaire (90% compared to 99% in the post-webinar questionnaire) reported that gum bleeding, receding gums, mobile teeth, and tooth loss are all signs of PD (P = .045). Regarding the statement “periodontal treatment influences the glucose level of diabetic patients,” the correct responses significantly increased from 63.64% in the pre-webinar questionnaire to 90.91% in the post-webinar questionnaire. Up to 32% of MPs in the pre-webinar questionnaire reported that PD is an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction. This increased significantly (87.50%) in the post-webinar questionnaire. Such improvements were significant too (P < .001) for the knowledge of the participants regarding whether “periodontal treatment aids in reducing systemic inflammatory markers” (61% vs 87%); “PD might lead to preterm delivery and low birth weight” (24% vs 82%); “the second trimester of pregnancy was the best time for performing the elective dental treatment” (53% vs 95%); “PD might increase the risk of premature death” (22% vs 80%); “PD is a risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus” (32% vs 75%); “there are oral consequences of obesity and metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents” (32% vs 94%); “depression might contribute to the risk of oral diseases” (27% vs 89%); “the association of PD with renal failure” (27% vs 70%); and “the role of PD in the pathogenesis of head and neck carcinogenesis” (34% vs 65%). Of 176 MPs, 96 (54.55%), 63 (35.80%), and 17 (9.66%) rated their knowledge on PD and its relationship to systemic diseases as limited, moderate, and good, respectively, in the pre-webinar questionnaire. The corresponding figures in the post-webinar questionnaire showed significant changes: 36 (20.45%), 88 (50.00%), and 52 (29.55%) rated their knowledge as limited, moderate, and good, respectively.

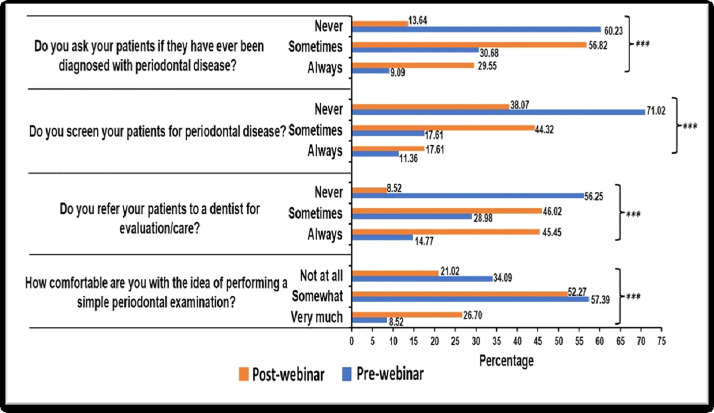

The improvement in knowledge extended to the practice as shown in Figure 2. Up to 60%, 71%, 57%, and 34% of the respondents reported that they “don't ask their patients whether they have ever been diagnosed with PD,” “don't screen their patients for PD,” and “don't refer their patients to a dentist for periodontal evaluation” and “whether they are comfortable with performing simple periodontal examination,” respectively. The corresponding figures in the post-webinar questionnaire were statistically reduced to 14%, 38%, 9%, and 21%, respectively. The responses “sometimes” and “always” increased, indicative of good practice.

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of practitioners’ practice regarding periodontal examination and patients.

Discussion

Within the context of the health care system, the provision of care by MPs is considered very important.37 The knowledge, awareness, attitudes, and practices of MPs regarding oral health represents a critical factor that can either encourage or hinder the development of a holistic health approach.38,39 In order to provide evidence-based care, both dental and medical professionals are required to treat the body as a whole and acknowledge the importance of interdisciplinary referrals. Despite that numerous studies have demonstrated the interrelationship between systemic conditions and periodontitis,25,40, 41, 42 there is a lack of knowledge and understanding amongst MPs about this interrelationship, in line with an unexpected mismatch between the scientific evidence and the practiced behaviours.2,34 Hence, there is an imperative need to examine MPs’ practices, knowledge, and awareness of this relevant issue in the Jazan region of Saudi Arabia.

The present study findings show that the knowledge of 54.55% of the MPs regarding the interrelationship between PD and systemic health is limited. This aligns closely with other studies that have reported comparable results. The present study is consistent with a similar cross-sectional study amongst medical and dental practitioners in Saudi Arabia,34 which found that 52.1% of MPs had low levels of awareness and knowledge, whilst general dentists’ practices and awareness were noticeably better. Similarly, a study conducted in India revealed that only 14% of MPs think that PD can lead to cardiovascular disease.43 In contrast, 93% of MPs in a Pakistani study accepted the possibility that poor oral health could lead to cardiovascular disease.31

A cross-sectional study conducted amongst French general MPs33 revealed fair knowledge concerning the interrelationship between PD and systemic diseases: 75% reported that they knew about the interrelationship of PD and diabetes; 53% to 59% reported that there is an effect of PD on heart disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and respiratory infections; and 35.18% and less than 15% reported that PD is an identifiable risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis and Alzheimer's disease, respectively. Furthermore, 74.31% of practitioners rarely or never inquired about patients’ periodontal health.33

Although 89.55% of MPs in the present study reported having no training in PD or oral health, the majority of MPs appear to be aware of the connections between PD and diabetes. Comparable results were obtained in Turkey: Only 28% of medical doctors claimed receiving instructions regarding the relationship between systemic diseases and PD during their early or ongoing training, whilst two-thirds believed that PD has an effect on diabetes. Indeed, the studies which link PD and diabetes date back to the 1970s. In fact, PD is recognised as the sixth complication of diabetes; the latter is also thought to be a risk factor for the former.44 As mounting evidence does exist that PD, and its treatment, have a varying impact on systemic health,32 MPs should be familiar with the pathophysiology, complications, and treatment methods for these 2 chronic diseases. The International Diabetes Federation and the World Dental Federation have promoted an increased awareness of the link between diabetes mellitus and oral health amongst health care professionals. Our study revealed that 63.64% of MPs possessed an average level of knowledge regarding the impact of periodontal therapy on the glucose levels of diabetic patients. However, a previous study conducted in India2 reported that all endocrinologists who partook in the study were aware of such an interrelationship, and compared to general practitioners, they recommend regular dental visits for their diabetic patients. Our corresponding figures improved significantly from 63.64% on the pre-webinar questionnaire to 90.91% on the post-webinar questionnaire.

More than 80% of the respondents to the pre-webinar questionnaire in our study reported not being comfortable carrying out a basic periodontal examination on their patients, never inquiring whether a patient has been diagnosed with periodontal disease, and never referring patients to a dentist for periodontal evaluation (Figure 2). Probably due to the lack of knowledge and practice, MPs prescribe antibiotics and pain medications for patients with dental pain who visit primary health care centres rather than performing definitive dental care, a matter which contributes to the problems of antibiotic resistance and opiate dependency.45 In contrast to our findings, another study showed that 59% of MPs reported enquiring about dental and oral diseases amongst their medical patients. MPs should inquire about oral health and go above and beyond if there are signs of bad breath or an infection in the mouth.

Limitations

This study used a self-reported questionnaire, a tool that has been criticised for many inherited shortages like false reporting and recall bias. Because this was a survey-based study, there might be participation bias, as participants who are interested in the topics are more likely to participate. Unfortunately, this is an unresolved problem in the questionnaire study. The sample size was small despite several reminders sent in an attempt to obtain a larger sample. Another limitation is that there was not enough time to capture the changes in the MPs’ practices; what the MPs reported in this context may reflect the improvement in their knowledge instead of reflecting real practice. A third limitation is that some may have doubts about the content of the webinar lecture, although 2 specialists (one in periodontology and one in oral medicine) prepared it according to the most recent evidence in context of interrelationship between PD and systemic diseases.

Conclusions

The study unveiled that MPs had low to moderate levels of knowledge and practice about the interrelationship between periodontal and systemic health and that conducting a webinar was pivotal in improving their knowledge and practice in this context.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Ethics Committee of the College of Dentistry Jazan University. Also, we would like to thank every medical practitioner for giving their valuable time and efforts to respond pre-webinar survey, attend the webinar, and again respond to the post-webinar survey.

Author contributions

Sameena Parveen: conceptualisation, methodology, writing–original draft. Ahmed Shaher Al Qahtani: writing–review and editing, investigation, resources. Esam Halboub: writing–review and editing. Reem Ali Ahmed Hazzazi: investigation, resources. Imtinan Ahmed Hussain Madkhali: investigation, resources. Aalaa Ibrahim Hussain Mughals: investigation, resources. Safeyah Abdulrahman Ali Baeshen: investigation, resources. Aamani Mohammed Moaidi: investigation, resources. Mohammed Sultan Al-Ak'hali: data curation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pihlstrom BL, Hodges JS, Michalowicz B, Wohlfahrt JC, Garcia RI. Promoting oral health care because of its possible effect on systemic disease is premature and may be misleading. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149:401–403. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obulareddy VT, Nagarakanti S, Chava VK. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors of medical specialists for the relationship between diabetes and periodontal disease: a questionnaire survey. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7:175. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_425_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century–the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(Suppl 1):3–23. doi: 10.1046/j..2003.com122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nazir M, Al-Ansari A, Al-Khalifa K, Alhareky M, Gaffar B, Almas K. Global prevalence of periodontal disease and lack of its surveillance. ScientificWorldJournal. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/2146160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas JT, Thomas T, Ahmed M, et al. Prevalence of periodontal disease among obese young adult population in Saudi Arabia—a cross-sectional study. Medicina (B Aires) 2020;56:197. doi: 10.3390/medicina56040197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parveen S. Impact of calorie restriction and intermittent fasting on periodontal health. Periodontol 2000. 2021;87:315–324. doi: 10.1111/prd.12400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee PH, McGrath CPJ, Kong AYC, Lam TH. Self-report poor oral health and chronic diseases: the Hong Kong FAMILY Project. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41::451–458. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richards D. Oral diseases affect some 3.9 billion people. Evid Based Dent. 2013;14:35. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zardawi F, Gul S, Abdulkareem A, Sha A, Yates J. Association between periodontal disease and atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases: revisited. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;7 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.625579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck J, Garcia R, Heiss G, Vokonas PS, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1123–1137. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedewald VE, Kornman KS, Beck JD, et al. The American Journal of Cardiology and Journal of Periodontology editors’ consensus: periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1021–1032. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.097001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lockhart PB, Bolger AF, Papapanou PN, et al. Periodontal disease and atherosclerotic vascular disease: does the evidence support an independent association? A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:2520–2544. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31825719f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaur S, White S, Bartold M. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012;10:1–12. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2012-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khader YS, Albashaireh ZSM, Alomari MA. Periodontal diseases and the risk of coronary heart and cerebrovascular diseases: a meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1046–1053. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.8.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iacopino AM. Periodontitis and diabetes interrelationships: role of inflammation. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:125–137. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lalla E, Papapanou PN. Diabetes mellitus and periodontitis: a tale of two common interrelated diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7:738–748. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hegde S, Chatterjee E, Rajesh KS, Arun Kumar MS. Obesity and its association with chronic periodontitis: a cross-sectional study. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8:222. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_40_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suvan J, D'Aiuto F, Moles DR, Petrie A, Donos N. Association between overweight/obesity and periodontitis in adults. A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e381–e404. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.da Silva HEC, Stefani CM, de Santos Melo N, et al. Effect of intra-pregnancy nonsurgical periodontal therapy on inflammatory biomarkers and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2017;6:197. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0587-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pitiphat W, Joshipura KJ, Gillman MW, Williams PL, Douglass CW, Rich-Edwards JW. Maternal periodontitis and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zadik Y, Bechor R, Galor S, Justo D, Heruti RJ. Erectile dysfunction might be associated with chronic periodontal disease: two ends of the cardiovascular spectrum. J Sex Med. 2009;6:1111–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Maweri SA, Ibraheem WI, Al-Ak'hali MS, Shamala A, Halboub E, Alhajj MN. Association of periodontitis and tooth loss with liver cancer: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;159 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grubbs V, Vittinghoff E, Taylor G, et al. The association of periodontal disease with kidney function decline: a longitudinal retrospective analysis of the MrOS dental study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:466–472. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esfahanian V, Shamami MS, Shamami MS. Relationship between osteoporosis and periodontal disease: review of the literature. J Dent (Tehran) 2012;9:256–264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alakhali MS, Ibraheem WIM, Al-Maweri SA, Neami SIA, Alhuraysi FM. Oral health status of female hospitalized psychiatric patients in Jazan: a case-control study. Braz Dent Sci. 2021;24:6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu F, Wen Y-F, Zhou Y, Lei G, Guo Q-Y, Dang Y-H. A meta-analysis of emotional disorders as possible risk factors for chronic periodontitis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e11434. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simpson TC, Clarkson JE, Worthington HV, et al. Does treatment for gum disease help people with diabetes control blood sugar levels? Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004714.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Middleton P, Esposito M, Glenny A-M. Treating periodontal disease for preventing adverse birth outcomes in pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005297.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmlund A, Lampa E, Lind L. Poor response to periodontal treatment may predict future cardiovascular disease. J Dent Res. 2017;96::768–773. doi: 10.1177/0022034517701901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mian F, Hamza SA, Wahid A, Bokhari SA. Medical and dental practitioners’ awareness about oral-systemic disease connections. J Pak Dent Assoc. 2018;26:151–157. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alhazmi YA, Parveen S, Alfaifi WH, et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice of diabetic patients towards oral health: a cross-sectional study. World J Dent. 2022;13:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dubar M, Delatre V, Moutier C, Sy K, Agossa K. Awareness and practices of general practitioners towards the oral-systemic disease relationship: a regionwide survey in France. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26:1722–1730. doi: 10.1111/jep.13343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al Sharrad A, Said KN, Farook FF, Shafik S, Al-Shammari K. Awareness of the relationship between systemic and periodontal diseases among physicians and dentists in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait: cross-sectional study. Open Dent J. 2019;13 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sivaramalingam J, Rajendiran KS, Mohan M, et al. Effect of webinars in teaching–learning process in medical and allied health science students during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. J Educ Health Promot. 2022;11:274. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1450_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bahammam MA. Periodontal health and diabetes awareness among Saudi diabetes patients. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:225–233. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S79543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maxey HL, Norwood CW, Weaver DL. Primary care physician roles in health centers with oral health care units. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:491–504. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2017.04.170106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leeder S, Corbett S, Usherwood T. General practice registrar education beyond the practice: the public health role of general practitioners. Aust Fam Physician. 2016;45:266–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grol SM, Molleman GRM, Kuijpers A, et al. The role of the general practitioner in multidisciplinary teams: a qualitative study in elderly care. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:40. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0726-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nazir MA. Prevalence of periodontal disease, its association with systemic diseases and prevention. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2017;11:72–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tonetti MS, Van Dyke TE, Working Group 1 of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop Periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(Suppl 14):S24–S29. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gomes-Filho IS, da Cruz SS, Trindade SC, et al. Periodontitis and respiratory diseases: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2020;26:439–446. doi: 10.1111/odi.13228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia RI, Cadoret C, Henshaw M. Multicultural issues in oral health. Dent Clin North Am. 2008;52 doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2007.12.006. 319–vi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taşdemir Z, Alkan BA. Knowledge of medical doctors in Turkey about the relationship between periodontal disease and systemic health. Braz Oral Res. 2015;29:55. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2015.vol29.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen LA. Expanding the physician's role in addressing the oral health of adults. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:408–412. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]