Abstract

BACKGROUND

Social media addiction (SM) is a widespread and severe problem in today’s world. It is associated with both self-esteem (SE) and general belongingness (GB). There are many studies related to these associations in the literature, but in this research an attempt was made to explain this mechanism based on social comparison theory. The aim of this study is to examine the indirect effect of social comparison (SC) on the relationship among SM, SE, and GB.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

The sample consisted of 311 university students studying at a state university in Turkey. Data were gathered by using a demographic information form, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, the General Belongingness Scale, the Social Comparison Scale, and the Social Media Addiction Scale-Student Form. The mediator effect of SC was determined via structural equation modelling.

RESULTS

The results indicate that SC has an indirect effect on the relation between SM and SE. Similarly, SC has an indirect effect on the relation between SM and GB.

CONCLUSIONS

People tend to compare themselves with other individuals, and this SC process can be made very easily and quickly via social media tools. Moreover, social media sites offer plenty of opportunities for SC, and this comparison consists of sometimes upward SC and sometimes downward SC processes. Downward and upward SC processes can regulate individuals’ emotions, SE, and GB levels in social media either in a negative or positive way. The mediating role of SC in the relationship between SM, SE, and GB can be examined in terms of these upward and downward SC processes.

Keywords: social media addiction, social comparison, downward social comparison, self-esteem, belongingness

BACKGROUND

The purpose of this study is to examine the mediating effect of social comparison on the relationship between social media addiction, and self-esteem and general belongingness. In today’s world, social network sites are a crucial part of individuals’ life, and social media addiction is a widespread and severe problem. Also, individuals may receive some beneficial effects from ordinary social media usage, but especially social media addiction might influence self-esteem and belongingness of individuals in a negative way. There are many studies related to social media, and self-esteem and general belongingness. In this research, we tried to be explain the relationships among social media addiction, self-esteem, and general belongingness. Most of the studies in the literature focuses only on the relationships among these variables; however, in this study, the mechanisms underlying these relationships were investigated from the downward and upward social comparison perspectives, and this investigation may create more explicit understanding of the relations among social media addiction, self-esteem, and belongingness.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Social media usage has been gradually increasing around the world. Beside this enormous usage, the number of social media accounts and varieties are also increasing, e.g. Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, and so on. Notably, most people are using their social media accounts through their smartphones, and these types of devices make social media more accessible. According to the social media statistics, more than three billion people are actively using social media accounts every day (Global Digital Report, 2019). These social network sites allow people to create a private profile for themselves and these people can contact each other via social media. They can share their photos, videos, and ideas. Furthermore, people can see and learn about photos, videos, and ideas of others through social media.

The effect of social media usage on individuals is a controversial issue in the academic world. Some studies have indicated that social media sites can cause a type of addiction and this may influence individuals in a negative way (for instance, lower life satisfaction, depression, lower self-esteem) (e.g., Burke et al., 2010; Hawi & Samaha, 2017; Krasnova et al., 2013) while others claim that social media usage can supply some benefits for its users such as higher self-esteem, higher sense of belonging, and lower loneliness (e.g., Ellison et al., 2007; Gonzales & Hancock, 2011; Seidman, 2013). However, there is a vital difference at this point. On one hand, ordinary social media usage may trigger some positive results such as higher self-esteem, sense of belonging or more positive interpersonal relationships. On the other hand, addictive usage of social media could have negative effects on self-esteem and sense of belonging. The focus of this study is the effects of social media addiction on self-esteem and general belongingness. There is a negative relationship among social media addiction, self-esteem, and belongingness (e.g., Andreassen et al., 2017). However, these relationships can also be twofold. Individuals who want to satisfy their self-esteem and belongingness needs may use social media as an opportunity (getting “likes”, escape from the lower sense of belonging and self-esteem) (Andreassen et al., 2017; Kırcaburun et al., belongingness. Also, these relations will be examined from the perspective of social comparison theory.2019). For this reason, this study aims to examine the effect of social media addiction on self-esteem and general

The results of the studies on social media addiction and self-esteem indicate that there is a negative relationship between social media addiction and self-esteem (e.g., Błachnio & Przepiorka, 2019; Cherie, 2017; Hawi & Samaha, 2017). For instance, in a study related to Facebook addiction and self-esteem, it was found that Facebook addiction is related to a lower level of self-esteem (Błachnio et al., 2016). Similarly, Andreassen et al. (2017) stated that lower self-esteem was associated with higher social media addiction score. Moreover, it is evident that there is a relationship between social media and the need to belong. Seidman (2013) stated that satisfying the need to belong and acceptance are major motivations for Facebook usage, and individuals who use social media might increase their self-esteem and sense of belongingness. Furthermore, there are some studies which detected positive relationships between social media and the need to belong (e.g., Casale & Fioravanti, 2018; Hodgins, 2015; Rashid et al., 2019). Nonetheless, these results should be considered differently according to ordinary usage of social media and social media addiction, because addictive usage might trigger some interpersonal troubles and withdrawal (Chen et al., 2003). An addicted person would like to create a relationship which satisfies his need to belong, but social media addiction could be blocking their meaningful interpersonal relationships in real life, and this may diminish the level of general belongingness. Studies indicate that there is a negative relationship between belongingness and problematic social media usage (Kırcaburun et al., 2019). This may also indicate that addictive social media usage could influence individuals’ level of belongingness in a negative way, rather than satisfying their general belongingness.

Self-esteem and need to belong are basic human needs, and people have desire to satisfy these psychological needs (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Williams, 2007). At this point, the Internet might provide an abundant opportunity to fulfil these needs. Most people would like to comprehend their capacities, ideas, and their appearance by comparing themselves to other people, and this process is called “social comparison” (Festinger, 1954). In today’s world, these comparisons could be made through social media accounts in a quicker way. Social media sites offer plenty of opportunities for social comparison (Vogel et al., 2014). A question might arise at this point: “Why does social media usage lead to an increase in the self-esteem and general belongingness levels of some people, while reducing these levels in others?”. This question could be answered by the help of downward and upward social comparisons.

Many people compare themselves with others, but these comparisons may consist of sometimes downward social comparisons, and sometimes upward social comparisons. Downward social comparison means that one compares oneself with people below in terms of traits which are important from their perspective, while upward social comparison means that one compares oneself with people higher in terms of traits which are important from their perspective (e.g., Crocker et al., 1987; Jang et al., 2016; Wills, 1981). Downward social comparison could be beneficial for individuals in a way that people who make downward social comparison in social media may have higher self-esteem and general belongingness levels than other individuals may. On the other hand, people who make upward social comparison in social media may have lower levels of self-esteem and general belongingness. A study indicated that participants who have a more upward social comparison on Facebook could have lower self-esteem (Vogel et al., 2014). Similarly, another study showed that there could be a positive relationship between Facebook usage and negative social comparison levels (de Vries & Kühne, 2015). In the Johnson and Knobloch-Westerwich (2014) study, the participants in negative mood arranged their moods by making more downward social comparisons. As a result, social media could be beneficial for emotion regulation.

In addition, a positive relationship among Facebook usage, social comparison frequency on Facebook, and higher levels of social comparison could cause higher depression and anxiety levels (Lee, 2014). Vogel et al. (2015) proposed that people who have high social comparison orientation may have lower levels of self-esteem and they may have more negative emotions after being exposed to social comparison on Facebook. Moreover, these researchers emphasize that upward social comparison on social media could cause more negative effects.

Moreover, individuals make upward social comparison on Instagram. This upward social comparison may trigger lower levels of self-esteem and lower levels of life satisfaction. Furthermore, the study indicated that participants who have lower self-esteem and lower life satisfaction tend to make upward social comparison on Instagram (Sözkesen & Biçer, 2018). Still, individuals having a low social comparison orientation on Instagram usage may have a lower level of loneliness (Yang, 2016). Most of the studies have examined social comparison on social media only for Facebook, but in these days Instagram and other popular social media platforms have been paid attention by researchers as well.

Individuals might compare themselves with other people according to their appearance, personality, success, and relationship. The viewpoint of comparison could also be crucial because appearance could be much more substantial for some individuals, while others could give more importance to personality issues. Fardouly et al. (2015) examined how social comparison on Facebook might have effects on a woman’s body image perception. In this study, female participants were randomly assigned to either ten minutes of browsing their Facebook page or control website pages. Participants who spent time on Facebook reported more negative mood compared to the control group. As a result, in general, individuals could make upward or downward social comparison on social media. These comparisons could increase or decrease their self-esteem or levels of sense of belonging.

In the present study, the aim is to investigate the indirect (mediating) effects of social comparison in the relationship among social media addiction, self-esteem, and general belongingness. It is obvious that there is a relationship among social media addiction, self-esteem, and general belongingness. Many studies have been conducted on these relationships. However, the purpose of this study is to explain the underlying mechanism of these associations, and it will be examined with the help of the social comparison theory.

Some individuals may use social media in a dependent manner, while others may use it at a normal level. According to the individuals’ manner of usage, the outcome of social media usage might change. Still, addictive social media usage may decrease individuals’ self-esteem and belongingness level, while people who use social media at an average level could have some positive results such as higher self-esteem and belongingness. Hawi and Samaha (2017) stated that social media addiction is negatively related to self-esteem. Furthermore, this relationship is independent from culture, and individuals who have lower self-esteem tend to spend more time on social media (Hawi & Samaha, 2017). The downward and upward social comparison may help us to explain the relationship between the use of social media at a dependent level and self-esteem and belongingness. Excessive social media usage may influence individuals’ self-esteem and belongingness in a negative way. Thus, these individuals would like to regulate their emotions. At that point, emotion regulation comes into play, and people who have lower self-esteem and sense of belongingness may regulate their emotions through downward social comparison in social media. Making the downward social comparison on social media could evoke some positive emotions. The negative impact of the addictive usage of social media on belongingness and self-esteem may diminish even if it does not entirely disappear. Amaro et al. (2019) found that belongingness and downward social comparison were associated positively. Also, Gibbons and Gerrard (1989) stated that individuals who have low self-esteem improve their mood states via downward social comparison information. Thus, especially the downward social comparison process may help to regulate mood and emotions. By the help of this process, the negative effects of excessive social media usage on self-esteem and belongingness may be diminished. As expressed above, previous research related to social media and social comparison forms the basis for the aim of this study. In this context, the mediating role of social comparison in the relationship between social media addiction and self-esteem, and in the relationship between social media addiction and general belongingness, was investigated. The hypotheses are given below.

H1: Social comparison is a mediator variable in the relationship between social media addiction and self-esteem.

H2: Social comparison is a mediator variable in the relationship between social media addiction and general belongingness.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The study was conducted with university students studying at a state university in Turkey in the fall of 2018-2019. In total, 311 participants aged 18-38 years were included (M = 20.96, SD = 2.44). Two-hundred twenty-one females (71.1%) and 90 males (28.9%) participated. Ethical permission from the Deanery of the Faculty was obtained for the study. Participants were given an extra five points as an incentive for their courses. Additionally, it was confirmed that all participants use at least one social media account. Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, YouTube, Snapchat, Pinterest, Swarm, and Tinder are counted as social media accounts.

DATA COLLECTION TOOLS

Demographic Information Form. A personal information form was used including questions about age and gender of the participants.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was developed by Rosenberg (1965) and a Turkish validity and reliability study was carried out by Çuhadaroğlu (1986). It is a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree) and consists of 10 items. (e.g., “I am able to do things as well as most other people”). The scale’s validity rate is .71, and test-retest reliability is .75.

Nonetheless, the adaptation study of this scale was carried out in 1986. For this reason, exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis were conducted in the sample of this study, as well. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted by using varimax rotation to determine the factor structure of this scale. The value of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) coefficient was .88, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity result was 1272.79 (p <. 001). Results of the analysis showed that the scale has a two factor structure, and these factors explain 62.15% of the total variance. Factor loadings of the scale’s items varied between .64 and .82. Cronbach’s α coefficient was calculated as .85 for the first factor and .82 for the second factor. After this analysis, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted with structural equation modelling, and fit indexes were as follows: χ2/df = 2.77, GFI = .93, AGFI = .89, CFI = .95, IFI = .96, RMSEA = .08, SRMR = .06. These results showed that the two factor structure, which is found in this study, is appropriate. These two factors were used as an observed variable, and a latent variable, self-esteem, was created. The total score was also used in the correlation analysis.

The General Belongingness Scale. This scale was developed by Malone et al. (2012) and a Turkish validity and reliability study was conducted by Duru (2015). The scale has two factors, which are acceptance (e.g., “When I am with other people, I feel included”) and rejection (e.g., “I feel as if people do not care about me”). It is a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) and consists of 12 items. Cronbach’s α score for the whole scale was found to be .92, for the acceptance subscale .89, and for the rejection subscale .91. In this study, Cronbach’s α coefficient was calculated for the whole scale as .92, for the acceptance subscale as .89, and for the rejection subscale as .90. The scale’s item-total correlation values varied from .48 to .79. Test-retest reliability scores were calculated for the whole scale as .84, for the acceptance sub-dimension as .70, and for the rejection sub-dimension as .75. Duru (2015) pointed out that scale’s rejection items can be reversed and a general belongingness score could be obtained. The general belongingness score was used for the correlation analysis in the current study. In structural equation modelling, two subscales (rejection and acceptance) were used as observed variable and a latent variable, general belongingness, was created.

Social Comparison Scale. Social Comparison Scale was developed by Allan and Gilbert (1995), and Turkish validity and reliability study was carried out by Şahin and Şahin (1992). The scale consists of two poles (e.g., “weaker-stronger”, “unconfident-more confident”). The scale has a 6-point Likert scale and consists of 18 items. The scale could be applied to both adolescents and adult samples. Higher scores mean positive self-schema and lower scores mean negative self-schema. The scale was translated into Turkish according to the standard translation rules. However, new items were added to the scale by Savaşır and Şahin (1997) during the translation process. As in the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale, this scale was also adapted into Turkish in 1997. For this reason, the scale’s exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis were conducted in this study’s sample as well. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted by using varimax rotation to determine the factor structure of the scale. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) coefficient was found to be .87, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity result was 1909.76 (p < .001). The results showed that the scale has a three factor structure, and these three factors explained 48.52% of the total variance. The factor loadings of the scale’s items varied between .38 and .85. Cronbach’s α coefficient was calculated as .85 for the first factor, for the second factor as .78, and for the third factor as .65. After this analysis, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted with structural equation modelling, and fit index values were as follows: χ2/df = 3.12, GFI = .91, AGFI = .87, CFI = .90, IFI = .91, RMSEA = .08, SRMR = .06. These results showed that the three factor structure is appropriate. These three factors were used as an observed variable, and a latent variable, social comparison, was created. The total score was used in the correlation analysis.

Social Media Addiction Scale-Student Form. The Social Media Addiction Scale-Student Form was developed by Şahin (2018) to determine social media addiction levels of high school and university students. It is a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) and consists of 29 items. (e.g., “I am eager to go on social media”, “A life without social media becomes meaningless for me”). According to the exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, the scale has a four-factor structure, but it also gives the total social media addiction score. This total score was used in the current research. Cronbach’s α coefficient value for the whole scale was .93. In this study, Cronbach’s α coefficient for the whole scale was .92. Moreover, the scale’s test-retest ratio was .94. For this scale, higher scores mean higher social media addiction levels. Moreover, the scale’s four factors were used as an observed variable, and a latent variable, social media addiction, was created.

PROCEDURE

At the very beginning, an informed consent form containing the details about the study was given to the participants. Participants who had volunteered for the study approved this form. Four questionnaire booklets were prepared considering the order effect. Participants fulfilled the demographic information form at the end of questionnaire booklets. The study took approximately 25 minutes.

RESULTS

In this section, the results of the statistical analysis will be given. Firstly, descriptive statistics are given in Table 1. Social media addiction, self-esteem, general belongingness, and social comparison scores of the participants are examined by t-test in terms of gender. The results showed that there are no statistical differences in terms of gender. In addition, the relationships among the variables are given in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| N | M age | SM | SE | GB | SC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | M | 221 | 20.84 | 68.26 | 31.41 | 35.15 | 80.56 |

| SD | 2.72 | 17.03 | 5.10 | 6.92 | 13.57 | ||

| Male | M | 90 | 21.29 | 65.16 | 32.41 | 35.48 | 81.76 |

| SD | 1.48 | 16.83 | 4.87 | 7.11 | 15.94 | ||

| Total | M | 311 | 20.96 | 67.36 | 31.70 | 35.24 | 80.91 |

| SD | 2.44 | 17.00 | 5.05 | 6.97 | 14.28 | ||

| t | 1.46 | –1.58 | –0.38 | –0.67 | |||

| p | .145 | .114 | .708 | .502 | |||

Note. N – total number of cases, SM – social media addiction, SE – self-esteem, GB – general belongingness, SC – social comparison.

Table 2.

Relationships among variables used in the study

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM | – | |||

| SE | -.36*** | – | ||

| GB | -.33*** | -.48*** | – | |

| SC | -.22*** | -.45*** | -.45*** | – |

Note. SM – social media addiction, SE – self-esteem, GB – general belongingness, SC – social comparison; *** p < 0.001

There exist negative significant relationships among self-esteem, general belongingness, social comparison, and social media addiction. There also exist positive significant relationships among self-esteem, general belongingness, and social comparison.

The predictive relationships among self-esteem, general belongingness, social comparison, and social media addiction were examined through structural equation modelling (SEM). A latent variable, social media addiction, was created by using the social media addiction scale’s sub-dimensions, and SEM analysis was carried out in this way. Similarly, three latent variables (social comparison, self-esteem, and general belongingness) were created. In total, two models were created. In the first model, the indirect effect of social comparison was examined in the relationship between self-esteem and social media addiction. In the second model, the indirect effect of social comparison was examined in the relationship between general belongingness and social media addiction. The first model’s fit index values were as follows: χ2/df = 2.52, p < .001, GFI = .96, AGFI = .92, CFI = .97, IFI = .97, TLI = .95, SRMR = .06, RMSEA = .07, 95% CI [–.39, –.10]. The fit indexes of the first model and bootstrap confidence intervals are within acceptable limits, and do not contain zero. The model is shown in Figure 1.

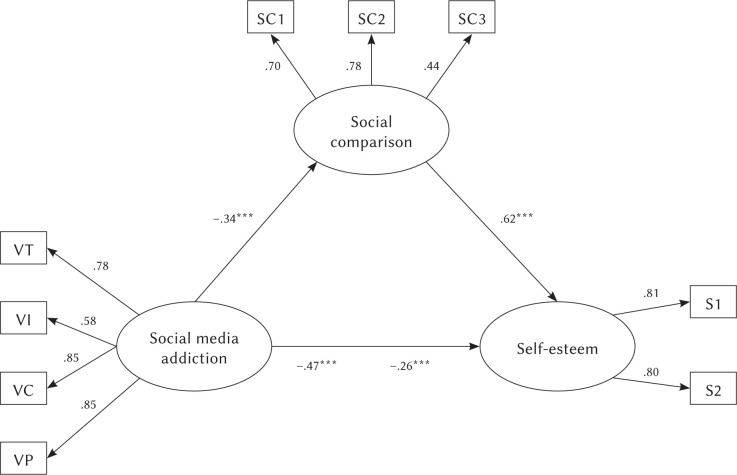

Figure 1.

Structural equation modeling in the relationship between social media addiction, self-esteem and social comparison

Note. VT (virtual tolerance), VI (virtual information), VC (virtual communication), VP (virtual problem) are components of the Social Media Addiction Scale. SC1, SC2, and SC3 are components of social comparison. S1 and S2 are components of Self-Esteem Scale. These dimensions were obtained as a result of exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses made on the Social Comparison and Self-Esteem Scale. That is why it is named S1 or SC1. All subdimensions were used as an observed variable and latent variables such as social media addiction, social comparison, and self-esteem were created. ***p < .001.

According to the results obtained from the first model, social media addiction predicts self-esteem in a negative way (β = –.26, t = –4.11, p < .001). Similarly, social media addiction predicts social comparison in a negative way (β = –.34, t = –4.63, p < .001), and social comparison also predicts self-esteem in a positive way (β = .62, t = 7.52, p < .001). It was determined that social media addiction affects the self-esteem indirectly (β = –.21, p < .001) through the social comparison variable. These results showed that the social comparison level plays a role as a partial mediator variable in the relationship between social media addiction and self-esteem (see also Table 3).

Table 3.

Structural equation modeling in the relationship between social media addiction, self-esteem and social comparison

| Dependent variable | Predictive variable | Total effect | Direct effect | Indirect effect | SE | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-esteem | Social media addiction | –.47 | –.26 | –.21 | .03 | –4.11*** |

| Social comparison | Social media addiction | –.34 | –.34 | .00 | .07 | –4.63*** |

| Self-esteem | Social comparison | .62 | .62 | .00 | .04 | 7.52*** |

Note. SE – standard error, ***p < .001.

Table 4.

Structural equation modeling in the relationship between social media addiction, general belongingness and social comparison

| Dependent variable | Predictive variable | Total effect | Direct effect | Indirect effect | SE | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General belongingness | Social media addiction | –.46 | –.27 | –.19 | .07 | –4.17*** |

| Social comparison | Social media addiction | –.34 | –.34 | .00 | .08 | –4.73*** |

| General belongingness | Social comparison | .55 | .55 | .00 | .08 | 6.93*** |

Note. SE – standard error. ***p < .001.

The second model’s fit index values were found to be as follows: χ2/df = 3.49, p < .001, GFI = .94, AGFI = .90, CFI = .94, TLI = .91, IFI = .94, SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .08, 95% CI [–.33, –.08]. The fit indexes of the second model and bootstrap confidence intervals are within acceptable limits, and do not contain zero. The model is shown in Figure 2.

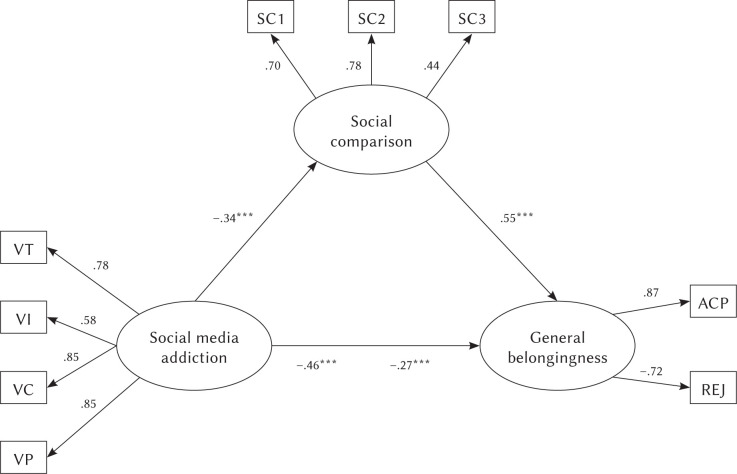

Figure 2.

Structural equation modeling in the relationship between social media addiction, general belongingness and social comparison

Note. VT (virtual tolerance), VI (virtual information), VC (virtual communication), VP (virtual problem) are components of the Social Media Addiction Scale. SC1, SC2, and SC3 are components of social comparison. ACP (acceptance) and REJ (rejection) are components of General Belongingness Scale. All subdimensions were used as an observed variable and latent variables such as social media addiction, social comparison, and general belongingness were created. ***p < .001.

According to the results obtained from the second model, social media addiction predicts general belongingness in a negative way (β = –.27, t = –4.17, p < .001). Similarly, social media addiction predicts social comparison in a negative way (β = –.34, t = –4.73, p < .001), and social comparison also predicts general belongingness in a positive way (β = .55, t = 6.93, p < .001). It was determined that social media addiction affects general belongingness indirectly (β = –.19, p < .001) through the social comparison variable. These results showed that the social comparison level plays a role as a partial mediator variable in the relationship between social media addiction and general belongingness.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present study was to examine the indirect effect of social comparison in the relationship among social media addiction, self-esteem, and general belongingness. Correlation analysis showed that there is a negative and significant relationship among social media addiction, self-esteem, and general belongingness. Moreover, there is a positive and significant relationship among social comparison, self-esteem, and general belongingness. The results revealed that there is a mediating role of social comparison in the relationship between social media addiction and self-esteem. Lastly, there is a mediating role of social comparison in the relationship between social media addiction and general belongingness.

Many studies have been carried out to examine the relations among social media addiction, self-esteem, and general belongingness; but the current study tries to explain the mechanism behind these associations. Also, this mechanism was examined based on the social comparison theory. The social comparison process consists of both downward social comparison and upward social comparison. When people tend to make upward social comparison on social media, their self-esteem and general belongingness levels could be damaged by an upward social comparison process (Bäzner et al., 2006; de Vries & Kühne, 2015; Vogel et al., 2014). Contrary to these expectations and the current results, a tendency to make downward social comparison on social media might affect individuals’ self-esteem and general belongingness in a positive way (Brown et al., 2007; Yang, 2016). The hypothesis of this study could underlie this framework.

In the current study, participants’ social comparison scores were found to be quite high (see also Table 1). The maximum score in the Social Comparison Scale is 108, and the minimum score is 18. In addition, the average score of the participants was found to be about 81 in the total sample. That is, our participants mostly had a positive self-schema about themselves. Individuals who participated in this study might tend to make downward social comparison in social media. The downward social comparison process provides some advantages for individuals who use this mechanism. To illustrate, individuals who make downward social comparison in social media might have higher self-esteem and general belongingness levels compared to other individuals who make upward social comparison. The findings of the current study support this idea as well. Hence, the indirect effect of social comparison in the relationship among social media addiction, self-esteem, and general belongingness could be explained from the perspective of the social comparison theory.

Social media addicts could have a lower level of self-esteem and general belongingness. Thus, there could be a negative relationship among social media addiction, self-esteem, and general belongingness in the current study. The results of the current study showed that participants tend to make downward social comparison (see also Table 1). In the downward social comparison process, individuals may compare themselves with other individuals who are lower in terms of various features (Jang et al., 2016; Wills, 1981). Also, individuals who use social media addictively could have lower levels of self-esteem. Nonetheless, they could make downward social comparison in their social media sites, and this process might regulate levels of their self-esteem. Similar explanations could be put forward for the “need to belong” concept. People can regulate their emotions with the downward social comparison process in social media. This situation can lead to higher levels of self-esteem or general belongingness, and indeed, individuals may regulate their emotions via social media (Johnson & Knobloch-Westerwich, 2014; Monacis et al., 2020; Pera, 2018).

Studies have revealed that being online could affect people cognitively. For example, because online social environments resemble real-world social processes and these types of environments may affect individuals to become alerted through this way, social lives of these individuals, including self-concepts and self-esteem, may create a new interaction with the internet (Firth et al., 2019). In the current study, individuals are stimulated through social comparison in the relationship between self-esteem and social media addiction by performing their social processes through the relevant online environments. In this way, it could change general belongingness levels of individuals through such online social processes.

Further, individuals’ psychological needs could be satisfied through social media, since getting “likes” in social online environments might be perceived as social rewards (Lindström et al., 2019). In a similar study, the effect of “online social currency” in social media is indicated as a secondary reinforcement that could increase the tendency of individuals to compare themselves with others (Rosenthal-von der Pütten et al., 2019). In the current study, the effect of this “currency” could be given as a basis for social comparisons of individuals.

There exist some limitations of the current study as well. Firstly, this study was based on self-report, and so participants might be likely to give socially acceptable answers to the questions in the scales. Therefore, the data should be evaluated by considering this possibility. In addition, there was no gender balance among participants since most of them were female. This may lead to gender bias; for this reason, readers should consider the possibility of gender bias when assessing the results.

In addition, negative automatic thinking and social media use seem to be positively related (Aksu et al., 2019). In this case, social media usage levels may cause individuals to produce these kinds of thoughts and it may increase social media usage. On the other hand, individuals’ metacognitive beliefs and self-regulation about their own thoughts may also have an effect on their use of social media (Casale et al., 2018). In this respect, it may be appropriate for future studies to focus especially on negative automatic thoughts and metacognitive factors.

Most of the studies on social comparison and social media are related to Facebook. The studies about image-based social media accounts such as Instagram are expected to be substantial in the future. Moreover, experimental studies could give much more exploratory information about the social comparison process on social media since almost all people are using at least one social media account nowadays. Even now, most of the people are busy making downward or upward social comparison on social media. For these reasons, it is crucial to comprehend the role of social comparison in social media activities, and effects of this role on psychological needs of individuals.

Footnotes

TO CITE THIS ARTICLE – Kavaklı, M., & Ünal, G. (2021). The effects of social comparison on the relationships among social media addiction, self-esteem, and general belongingness levels. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 9(2), 114–124.

References

- Aksu, M. H., Yigman, F., Unver, H., & Ozdel, K. (2019). The relationship between social problem solving, cognitive factors and social media addiction in young adults: a pilot study. Journal of Cognitive-Behavioral Psychotherapy and Research, 8, 164–169. 10.5455/JCBPR.59882 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allan, S., & Gilbert, P. (1995). A Social Comparison Scale: Psychometric properties and relationship to psychopathology. Personality and Individual Differences, 19, 293–299. 10.1016/01918869(95)00086-L [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro, L. M., Joseph, N. T., & de los Santos, T. M. (2019). Relationships of online social comparison and parenting satisfaction among new mothers: The mediating roles of belonging and emotion. Journal of Family Communication, 19, 144–156. 10.1080/15267431.2019.1586711 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen, C. S., Pallesen, S., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 287–293. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. 10.1037//0033-2909.117.3.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäzner, E., Brömer, P., Hammelstein, P., & Meyer, T. D. (2006). Current and former depression and their relationship to the effects of social comparison processes. Results of an Internet based study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 93, 97–103. 10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Błachnio, A., & Przepiorka, A. (2019). Be aware! If you start using Facebook problematically you will feel lonely: Phubbing, loneliness, self-esteem, and Facebook intrusion. A cross-sectional study. Social Science Computer Review, 37, 270–278. 10.1177/0894439318754490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Błachnio, A., Przepiorka, A., & Pantic, I. (2016). Association between Facebook addiction, self-esteem and life satisfaction: a cross-sectional study. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 701–705. 10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D. J., Ferris, D. L., Heller, D., & Keeping, L. M. (2007). Antecedents and consequences of the frequency of upward and downward social comparisons at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102, 59–75. 10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.10.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, M., Marlow, C., & Lento, T. (2010, April). Social network activity and social well-being. Paper presented at ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Retrieved from 10.1145/1753326.1753613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casale, S., & Fioravanti, G. (2018). Why narcissists are at risk for developing Facebook addiction: The need to be admired and the need to belong. Addictive Behaviors, 76, 312–318. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale, S., Rugai, L., & Fioravanti, G. (2018). Exploring the role of positive metacognitions in explaining the association between the fear of missing out and social media addiction. Addictive Behaviors, 85, 83–87. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. H., Weng, L. J., Su, Y. J., Wu, H. M., & Yang, P. F. (2003). Development of a Chinese Internet Addiction Scale and its psychometric study. Chinese Journal of Psychology, 45, 279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Cherie, M. (2017). Relationship between Facebook use, self-esteem and life satisfaction among students in Addis Ababa University School of Commerce (Master thesis). Addis Ababa University.

- Crocker, J., Thompson, L. L., McGraw, K. M., & Ingerman, C. (1987). Downward comparison, prejudice, and evaluations of others: Effects of self-esteem and threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 907–916. 10.1037//0022-3514.52.5.907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çuhadaroğlu, F. (1986). Self-esteem in adolescents (Unpublished expertise thesis). Hacettepe University.

- de Vries, D. A., & Kühne, R. (2015). Facebook and self-perception: Individual susceptibility to negative social comparison on Facebook. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 217–221. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duru, E. (2015). Genel Aidiyet Ölçeğinin Psikometrik Özellikleri: Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması [The psychometric properties of the General Belongingness Scale: a study of reliability and validity]. Turkish Psychological Counselling and Guidance Journal, 5, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12, 1143–1168. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fardouly, J., Diedrichs, P. C., Vartanian, L. R., & Halliwell, E. (2015). Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image, 13, 38–45. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140. 10.1177/001872675400700202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Firth, J., Torous, J., Stubbs, B., Firth, J. A., Steiner, G. Z., Smith, L., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Gleeson, J., Vancampfort, D., Armitage, C. J., & Sarris, J. (2019). The “online brain”: How the Internet may be changing our cognition. World Psychiatry, 18, 119–129. 10.1002/wps.20617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, F. X., & Gerrard, M. (1989). Effects of upward and downward social comparison on mood states. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 8, 14–31. 10.1521/jscp.1989.8.1.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Global Digital Report (2019, April 15). Digital in 2019. Retrieved from https://wearesocial.com/global-digital-report-2019

- Gonzales, A. L., & Hancock, J. T. (2011). Mirror, mirror on my Facebook wall: Effects of exposure to Facebook on self-esteem. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14, 79–83. 10.1089/cyber.2009.0411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawi, N. S., & Samaha, M. (2017). The relations among social media addiction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in university students. Social Science Computer Review, 35, 576–586. 10.1177/0894439316660340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins, C. (2015). Investigating the relationship between Facebook and self-esteem, the need to belong and extraversion (Bachelor of arts degree thesis). Dublin Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, K., Park, N., & Song, H. (2016). Social comparison on Facebook: Its antecedents and psychological outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 147–154. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B. K., & Knobloch-Westerwick, S. (2014). Glancing up or down: Mood management and selective social comparisons on social networking sites. Computers in Human Behavior, 41, 33–39. 10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kırcaburun, K., Kokkinos, C. M., Demetrovics, Z., Király, O., Griffiths, M. D., & Çolak, T. S. (2019). Problematic online behaviors among adolescents and emerging adults: Associations between cyberbullying perpetration, problematic social media use, and psychosocial factors. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17, 891–908. 10.1007/s11469-018-9894-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova, H., Wenninger, H., Widjaja, T., & Bruxmann, P. (2013, February). Envy on Facebook: a hidden threat to users’ life satisfaction? Paper presented at the 11th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik, Leipzig, Germany. Retrieved from https://boris.unibe.ch/47080/

- Lee, S. Y. (2014). How do people compare themselves with others on social network sites? The case of Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 32, 253–260. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindström, B., Bellander, M., Chang, A., Tobler, P. N., & Amodio, D. M. (2019). A computational reinforcement learning account of social media engagement. PsyArXiv. 10.31234/osf.io/78mh5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malone, G. P., Pillow, D. R., & Osman, A. (2012). The General Belongingness Scale (GBS): Assessing achieved belongingness. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 311–316. 10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monacis, L., Griffiths, M. D., Limone, P., Sinatra, M., & Servidio, R. (2020). Selfitis behavior: Assessing the Italian version of the Selfitis Behavior Scale and its mediating role in the relationship of dark traits with social media addiction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 5738. 10.3390/ijerph17165738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pera, A. (2018). Psychopathological processes involved in social comparison, depression, and envy on Facebook. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 22. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, U. K., Ahmed, O., & Hossain, M. A. (2019). Relationship between need for belongingness and Facebook addiction: Mediating role of number of friends on Facebook. International Journal of Social Science Studies, 7, 36–43. 10.11114/ijsss.v7i2.4017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE). In J. Ciarrochi & L. Bilich (Eds.), Acceptance and commitment therapy. Measures Package (pp. 61–62). School of Psychology, University of Wollongong. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal-von der Pütten, A. M., Hastall, M. R., Köcher, S., Meske, C., Heinrich, T., Labrenz, F., & Ocklenburg, S. (2019). “Likes” as social rewards: Their role in online social comparison and decisions to like other people’s selfies. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 76–86. 10.1016/j.chb.2018.10.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Şahin, C. (2018). Social Media Addiction Scale-Student Form: The reliability and validity study. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology–TOJET, 17, 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Şahin, N. H., & Şahin, N. (1992, June). Adolescent guilt, shame, and depression in relation to sociotropy and autonomy. Paper presented at the World Congress of Cognitive Therapy, Toronto.

- Savaşır, I., & Şahin, N. H. (eds.) (1997). Bilişsel-davranışçı terapilerde değerlendirme: Sık kullanılan ölçekler [Assessment in cognitive-behavioral therapies: Frequently used scales]. Türk Psikologlar Derneği Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman, G. (2013). Self-presentation and belonging on Facebook: How personality influences social media use and motivations. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 402–407. 10.1016/j.paid.2012.10.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sözkesen, M. E., & Biçer, S. (2018). Social comparison, self-esteem and life satisfaction on Instagram: a review on Fırat University. The Journal of the Faculty of Communication of the University of Akdeniz, 29, 302–326. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Okdie, B. M., Eckles, K., & Franz, B. (2015). Who compares and despairs? The effect of social comparison orientation on social media use and its outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 249–256. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Roberts, L. R., & Eckles, K. (2014). Social comparison, social media, and self-esteem. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 3, 206–222. 10.1037/ppm0000047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 425–452. 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills, T. A. (1981). Downward comparison principles in social psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 90, 245–271. 10.1037/0033-2909.90.2.245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C. C. (2016). Instagram use, loneliness, and social comparison orientation: Interact and browse on social media, but don’t compare. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19, 703–708. 10.1089/cyber.2016.0201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]