Abstract

α-l-Arabinofuranosidases I and II were purified from the culture filtrate of Aspergillus awamori IFO 4033 and had molecular weights of 81,000 and 62,000 and pIs of 3.3 and 3.6, respectively. Both enzymes had an optimum pH of 4.0 and an optimum temperature of 60°C and exhibited stability at pH values from 3 to 7 and at temperatures up to 60°C. The enzymes released arabinose from p-nitrophenyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside, O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-(1→3)-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→4)-d-xylopyranose, and arabinose-containing polysaccharides but not from O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→2)-O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-(1→3)-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→4)-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→4)-d-xylopyranose. α-l-Arabinofuranosidase I also released arabinose from O-β-d-xylopy-ranosyl-(1→4)-[O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-(1→3)]-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→4)-d-xylopyranose. However, α-l-arabinofuranosidase II did not readily catalyze this hydrolysis reaction. α-l-Arabinofuranosidase I hydrolyzed all linkages that can occur between two α-l-arabinofuranosyl residues in the following order: (1→5) linkage > (1→3) linkage > (1→2) linkage. α-l-Arabinofuranosidase II hydrolyzed the linkages in the following order: (1→5) linkage > (1→2) linkage > (1→3) linkage. α-l-Arabinofuranosidase I preferentially hydrolyzed the (1→5) linkage of branched arabinotrisaccharide. On the other hand, α-l-arabinofuranosidase II preferentially hydrolyzed the (1→3) linkage in the same substrate. α-l-Arabinofuranosidase I released arabinose from the nonreducing terminus of arabinan, whereas α-l-arabinofuranosidase II preferentially hydrolyzed the arabinosyl side chain linkage of arabinan.

Recently, it has been proven that l-arabinose selectively inhibits intestinal sucrase in a noncompetitive manner and reduces the glycemic response after sucrose ingestion in animals (33). Based on this observation, l-arabinose can be used as a physiologically functional sugar that inhibits sucrose digestion. Effective l-arabinose production is therefore important in the food industry. l-Arabinosyl residues are widely distributed in hemicelluloses, such as arabinan, arabinoxylan, gum arabic, and arabinogalactan, and the α-l-arabinofuranosidases (α-l-AFases) (EC 3.2.1.55) have proven to be essential tools for enzymatic degradation of hemicelluloses and structural studies of these compounds.

α-l-AFases have been classified into two families of glycanases (families 51 and 54) on the basis of amino acid sequence similarities (11). The two families of α-l-AFases also differ in substrate specificity for arabinose-containing polysaccharides. Beldman et al. summarized the α-l-AFase classification based on substrate specificities (3). One group contains the Arafur A (family 51) enzymes, which exhibit very little or no activity with arabinose-containing polysaccharides. The other group contains the Arafur B (family 54) enzymes, which cleave arabinosyl side chains from polymers. However, this classification is too broad to define the substrate specificities of α-l-AFases. There have been many studies of the α-l-AFases (3, 12), especially the α-l-AFases of Aspergillus species (2–8, 12–15, 17, 22, 23, 28–32, 36–39, 41–43, 46). However, there have been only a few studies of the precise specificities of these α-l-AFases. In previous work, we elucidated the substrate specificities of α-l-AFases from Aspergillus niger 5-16 (17) and Bacillus subtilis 3-6 (16, 18), which should be classified in the Arafur A group and exhibit activity with arabinoxylooligosaccharides, synthetic methyl 2-O-, 3-O-, and 5-O-arabinofuranosyl-α-l-arabinofuranosides (arabinofuranobiosides) (20), and methyl 3,5-di-O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside (arabinofuranotrioside) (19).

In the present work, we purified two α-l-AFases from a culture filtrate of Aspergillus awamori IFO 4033 and determined the substrate specificities of these α-l-AFases by using arabinose-containing polysaccharides and the core oligosaccharides of arabinoxylan and arabinan.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Substrates.

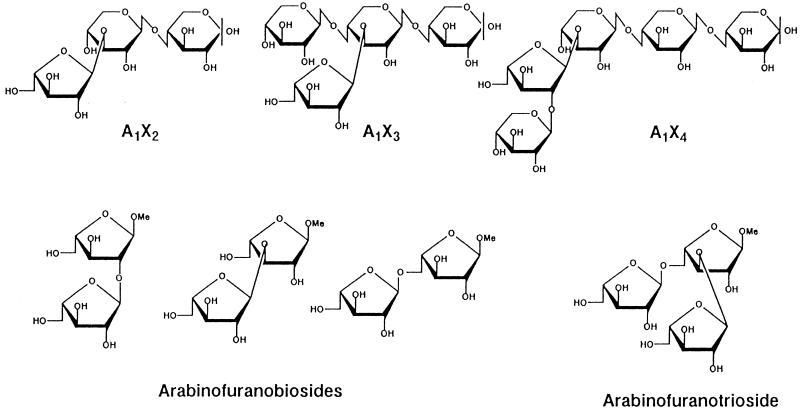

p-Nitrophenyl-α-l-arabinopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-xylopyranoside, and larch wood arabinogalactan were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, Mo.). Gum arabic was obtained from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan). Nihon Syokuhin Kakoh Co., Ltd. (Fuji, Japan), supplied corn hull arabinoxylan, and debranched arabinan (linear 1→5-linked arabinan) was obtained from Megazyme Pty., Ltd. (North Rocks, Australia). Sugar beet arabinan and arabinoxylooligosaccharides were prepared by methods described previously (24, 25, 49). p-Nitrophenyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside (PNP-α-l-Araf) was synthesized by the method of Kelly et al. (21). Methyl 2-O-, methyl 3-O-, and methyl 5-O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-α-l-arabinofuranosides (arabinofuranobiosides) and methyl 3,5-di-O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside (arabinofuranotrioside) were synthesized by methods described previously (19, 20). Figure 1 shows the structures of arabinoxylooligosaccharides and arabinooligosaccharides.

FIG. 1.

Structures of arabinoxylooligosaccharides, arabinofuranobiosides, and arabinofuranotrioside.

α-l-AFase assay and measurement of protein.

Each assay mixture contained 0.5 ml of a 2 mM PNP-α-l-Araf solution, 0.4 ml of McIlvaine buffer (0.2 M Na2HPO4, 0.1 M citric acid) (pH 4.0), and 0.1 ml of enzyme solution. The reaction was carried out at 50°C for 10 min and was stopped by adding 1.0 ml of a 0.2 M Na2CO3 solution, and the amount of p-nitrophenol (PNP) released was then determined at 408 nm (standard method). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme which released 1 μmol of PNP from PNP-α-l-Araf per min under these conditions.

The α-l-AFase activities with PNP glycosides were determined like the activity with PNP-α-l-Araf was determined except that various PNP glycosides were used.

The protein concentration during purification of the enzyme was measured by determining the absorbance at 280 nm and assuming that an absorbance at 280 nm of 1.0 was equal to a concentration of 1 mg per ml. The protein concentration was also determined by the method described by Smith et al. (34) by using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Preparation of the crude enzyme.

A. awamori IFO 4033, which was purchased from the Institute of Fermentation, Osaka (Osaka, Japan), was cultured in five 500-ml shaking flasks containing 100 ml of medium consisting of 2.0% arabinoxylan, 0.6% peptone, 0.3% yeast extract, 1.0% KH2PO4, and 0.05% MgSO4 · 7H2O. Preparations were cultivated on a reciprocal shaker (125 oscillations per min) at 35°C for 90 h. The culture broth was then filtered through filter paper (type 2; Toyo Roshi Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and the culture filtrate was used as the crude enzyme preparation.

Purification of α-l-AFases.

All purification procedures were performed at 6°C.

(i) Step 1 (both fractions).

The culture filtrate obtained as described above was dialyzed against deionized water, and the dialyzed enzyme was applied to a column (30 by 200 mm) containing ECTEOLA-Cellulose (Wako) equilibrated with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 4.5). The column was then washed with the same buffer, and the enzyme was eluted from the column with a linear 0 to 0.5 M NaCl gradient (total volume, 2,000 ml) at a flow rate of 100 ml per h. The eluate was fractionated into 20-ml portions. The α-l-AFase was separated into two fractions, fraction I (α-l-AFase I) (fraction tubes 41 through 49) and fraction II (α-l-AFase II) (fraction tubes 56 through 75). Fraction I was dialyzed against deionized water, while fraction II was concentrated by ultrafiltration (type YM 10 membrane filter; Amicon Inc., Beverly, Mass.).

(ii) Step 2 (fraction I).

The dialyzed fraction I (α-l-AFase I) was applied to an SP-Sephadex C-50 column (37 by 750 mm) equilibrated with McIlvaine buffer (pH 2.5). After the column was washed with the same buffer, the enzyme was eluted from the column with a pH 2.5 to 5.0 gradient (total volume, 1,000 ml) at a flow rate of 50 ml per h. The eluate was collected in 10-ml portions. The active fractions, fractions 40 to 44, were combined and dialyzed against deionized water.

(iii) Step 3 (fraction I).

The dialyzed enzyme (α-l-AFase I) was applied to a Mono S HR 5/5 column (5 by 50 mm) which had been equilibrated with a 1/5 dilution of McIlvaine buffer (pH 2.5). After the column was washed with the same buffer, the enzyme was eluted from the column with a pH 2.5 to 4.25 gradient (total volume, 60 ml) at a flow rate of 1 ml per min. The eluate was fractionated into 1-ml portions. The active fractions, fractions 47 to 50, were combined and dialyzed against deionized water, and the final preparation was used as purified α-l-AFase I.

(iv) Step 2 (fraction II).

Concentrated fraction II (α-l-AFase II) was applied to an Ultrogel AcA 44 column (40 by 700 mm) equilibrated with 0.2 M NaCl in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5). An elution flow rate of 15 ml per h was used, and the eluate was fractionated into 10-ml portions. The fractions with α-l-AFase activity (fraction tubes 47 through 53) were combined and dialyzed against deionized water. The final preparation obtained was used as purified α-l-AFase II.

PAGE.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was carried out in a 12% polyacrylamide gel by the method of Laemmli (27). The protein was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 and then destained with 10% acetic acid in 30% methanol. The molecular weight of the enzyme was determined by SDS-PAGE by using molecular weight markers (SDS-PAGE Standard Low; Bio-Rad). The N-terminal amino acid sequences of α-l-AFases I and II were determined with a model HP G1005A protein sequence system.

The method described previously (48) was used to determine the isoelectric points of α-l-AFases I and II. The protein was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250, and the isoelectric focusing calibration kit (pH 2.5 to 6.5; Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) was used as the standard proteins for the pI measurements.

Enzymatic properties.

The effects of pH on the activity and stability of α-l-AFases were determined in a series of McIlvaine buffers with pH values from 2 to 8. The activity of α-l-AFase was assayed by the standard method. To measure the stability of α-l-AFases, preparations were preincubated in the absence of substrate for 120 min at 30°C. The residual activity was then assayed by the standard method.

The effects of temperature on the activity and stability of α-l-AFases were determined with a series of water baths at temperatures ranging from 30 to 80°C. The activity of α-l-AFase was assayed by the standard method. To measure the stability of the α-l-AFases, preparations were preincubated at pH 4.0 for 120 min, and the residual activity was then assayed.

α-l-AFase activity with arabinose-containing poly- or oligosaccharides.

Each reaction mixture contained 0.5 ml of an α-l-AFase solution (0.3 U), 0.4 ml of McIlvaine buffer (pH 4.0), and 0.1 ml of 1% substrate (arabinoxylan, arabinogalactan, gum arabic, arabinan, or debranched arabinan). After 24 h of incubation at 30°C, the reducing power formed from each substrate was measured by the Somogyi-Nelson method (35).

The α-l-AFase activity experiments with arabinoxylooligosaccharides were identical to the activity experiments with polysaccharides except that the concentration of each arabinoxylooligosaccharide used was 10%. After 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of incubation at 30°C, the reaction mixtures were heated in a boiling water bath for 10 min to stop the reaction. One microliter of each mixture was used for thin-layer chromatography to characterize the hydrolysis products. Chromatography was performed by using the ascending method with HPTLC Alufolien Cellulose (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and a 1-butanol–pyridine–water (6:4:3, vol/vol/vol) solvent system. The sugars on each plate were detected by heating the plate at 140°C for about 5 min after it was sprayed with a 1% methanol solution of p-anisidine hydrochloride.

Reaction mixtures that contained 0.1-ml portions of 10% arabinofuranobioside or arabinofuranotrioside solutions instead of polysaccharides were used to determine the activity with arabinooligosaccharides. After 0, 10, 20, and 30 min of incubation at 50°C, the reducing power formed from methyl α-l-arabinofuranobioside was determined by the Somogyi-Nelson method (35). Also, after 3 h of incubation at 30°C, reaction mixtures containing methyl arabinofuranotrioside were applied to a C18 column [LiChrospher 100 RP-18 (5 μm); Cica-Merck, Darmstadt, Germany] that had been preequilibrated with 1.7% CH3CN at a flow rate of 0.5 ml per min. The eluted sugars were detected with a reflective index detector.

Glycosyl linkage composition of α-l-AFase-digested arabinans.

The reaction mixture described above containing 1% arabinan was incubated for 3 h at 30°C. Then 100 μl of the mixture was applied to a Superdex peptide HR 10/30 (Pharmacia) column which had been equilibrated with 200 mM HCOONH4 buffer (pH 7.0) to remove the arabinose. The arabinan hydrolysate was pooled and lyophilized. The glycosyl linkage composition of the arabinan hydrolysate was determined by using a modification of the Hakomori procedure (9). The polysaccharide was per-O-methylated with methylsulfinyl methyl potassium and iodomethane, and the resulting products were isolated by using Sep-Pak C18 cartridges (44). The glycosyl linkage composition was then determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry of the resulting partially methylated, partially acetylated alditol acetate derivatives (47).

RESULTS

Purification and enzymatic properties of the α-l-AFases.

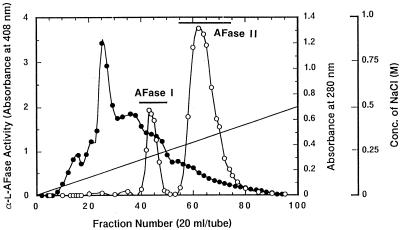

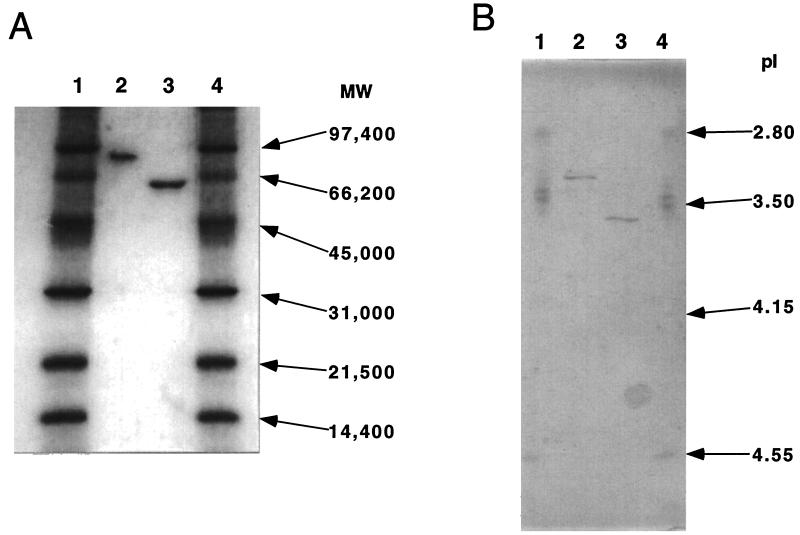

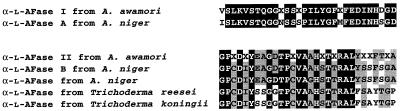

A. awamori IFO 4033 produced two extracellular α-l-AFases. Purification of α-l-AFases I and II from A. awamori IFO 4033 is summarized in Table 1. These two enzymes were completely separated by ECTEOLA-Cellulose column chromatography (Fig. 2). Each of the purified enzymes was resolved as a single band by SDS-PAGE when the bands were visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 staining (Fig. 3). The molecular weights of α-l-AFases I and II were estimated to be 81,000 and 62,000, respectively, by SDS-PAGE. The α-l-AFase I pI was 3.3, and the α-l-AFase II pI was 3.6 (Fig. 3). Figure 4 shows the amino acid sequences of the amino termini of α-l-AFases from various sources. The amino acid sequences of α-l-AFases I and II were quite different but exhibited high levels of homology to the amino acid sequences of A. niger α-l-AFases A and B, respectively. Both α-l-AFase I and α-l-AFase II exhibited maximum activity at pH 4.0. Both enzymes were also slowly inactivated at pHs above 7.0 and below 3.0. The maximum activity for each enzyme occurred at 60°C; however, the enzymes were inactivated at temperatures above 60°C (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Summary of the purification of α-l-AFases I and II from A. awamori

| Step | Total activity (U) | Total protein (mg) | Sp act (U/mg) | Purification (fold) | % Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture filtrate | 943 | 1,628 | 0.58 | 1 | 100 |

| ECTEOLA-Cellulose (α-l-AFase I) | 185 | 29 | 6 | 10 | 20 |

| ECTEOLA-Cellulose (α-l-AFase II) | 867 | 16 | 54 | 92 | 93 |

| SP-Sephadex C-50 (α-l-AFase I) | 113 | 0.32 | 353 | 609 | 12 |

| Mono S HR 5/5 (α-l-AFase I) | 18 | 0.046 | 391 | 674 | 2 |

| Ultrogel AcA 44 (α-l-AFase II) | 545 | 5 | 109 | 188 | 58 |

FIG. 2.

ECTEOLA-Cellulose column chromatography. The experimental conditions used are described in Materials and Methods. ○, α-l-AFase activity; •, absorbance at 280 nm; —, NaCl gradient. The bar indicates fractions that were pooled.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE and isoelectric focusing of α-l-AFases from A. awamori IFO 4033. (A) SDS-PAGE of α-l-AFases I and II. Lanes 1 and 4, standard proteins (2 μg each), including phosphorylase b (molecular weight, 97,000), bovine serum albumin (66,200), ovalbumin (45,000), carbonic anhydrase (31,000), soybean trypsin inhibitor (21,500), and lysozyme (14,400); lane 2, purified α-l-AFase I (2 μg); lane 3, purified α-l-AFase II (2 μg). (B) Isoelectric focusing of α-l-AFases I and II. Lanes 1 and 4, standard proteins (1 μg each), including pepsinogen (pI 2.80), amyloglucosidase (pI 3.5), glucose oxidase (pI 4.15), and soybean trypsin inhibitor (pI 4.55); lane 2, purified α-l-AFase I (1 μg); lane 3, purified α-l-AFase II (1 μg).

FIG. 4.

N-terminal amino acid sequences of α-l-AFases from A. awamori IFO 4033. The search for amino acid sequences homologous to the amino acid sequences of α-l-AFases was performed with MPsrch (mpsearch@dna.affrc.go.jp). The amino acid residues that are identical in three sequences are shaded. The amino acid residues that are completely conserved are indicated by white letters on a black background. α-l-AFase A from A. niger (accession no. A27979) belongs to glycosyl hydrolase family 51; α-l-AFase B from A. niger (A27977), α-l-AFase from A. niger (U39942), α-l-AFase from Trichoderma reesei (Z69252), and α-l-AFase from Trichoderma koningii (U38661) belong to family 54.

Substrate specificities.

Both enzymes from A. awamori IFO 4033 hydrolyzed PNP-α-l-Araf but did not hydrolyze p-nitrophenyl-α-l-arabinopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-xylopyranoside, and p-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (data not shown).

Table 2 shows the levels of hydrolysis of arabinan, debranched arabinan, arabinoxylan, arabinogalactan, and gum arabic by the α-l-AFases from A. awamori IFO 4033. Differences in the amounts of arabinose produced from these substrates were observed for the two enzymes.

TABLE 2.

Activities of α-l-AFases from A. awamori with arabinose-containing polysaccharides

| Substrate | Arabinose content (%) | % Hydrolysisa

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| α-l-AFase I | α-l-AFase II | ||

| Arabinan | 81.3 | 36.3 | 67.4 |

| Debranched arabinan | 88.0 | 25.6 | 23.3 |

| Arabinoxylan | 41.0 | 20.6 | 16.0 |

| Arabinogalactan | 18.2 | 41.3 | 20.2 |

| Gum arabic | 37.7 | 10.3 | 8.1 |

Levels of hydrolysis were estimated by assuming that the total arabinose content was 100%. The experimental conditions used are described in Materials and Methods. After 24 h of incubation at 30°C, the reducing powers formed from the polysaccharides were measured by the Somogyi-Nelson method (35). The glycosyl compositions of the substrates were as follows: arabinan, Ara-Gal-Rha (81.3:13.1:3.1); debranched arabinan, Ara-Gal-Rha-GalUA (88:4:2:6); arabinoxylan, Ara-Xyl (41.0:59.0); arabinogalactan, Ara-Gal-Rha (18.2:80.1:1.7); and gum arabic, Ara-Gal-Rha (37.7:44.6:17.7).

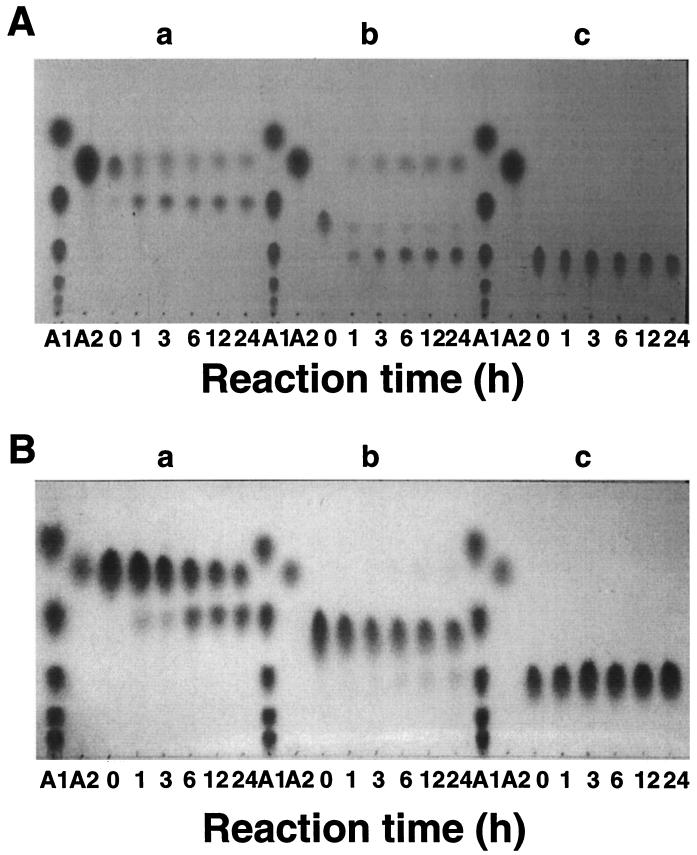

Figure 5A shows the course of hydrolysis of O-α-l-arabino-furanosyl-(1→3)-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→4)-d-xylopyranose (A1X2), O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→4)-[O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-(1→3)]-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→4)-d-xylopyranose (A1X3), and O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→2)-O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-(1→3)-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→4)-O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→4)-d-xylopyranose (A1X4) by α-l-AFase I from A. awamori IFO 4033. α-l-AFase I released arabinose from A1X2 and A1X3 (Fig. 5Aa and Ab) but not from A1X4 (Fig. 5Ac). Figure 5B shows the course of hydrolysis of A1X2, A1X3, and A1X4 by α-l-AFase II from A. awamori IFO 4033. α-l-AFase II completely hydrolyzed A1X2 and only slightly hydrolyzed A1X3 (Fig. 5Ba and Bb), but arabinose was not liberated from A1X4 (Fig. 5Bc).

FIG. 5.

Activities of α-l-AFases from A. awamori IFO 4033 with arabinoxylooligosaccharides. (A) α-l-AFase I. (B) α-l-AFase II. (a) A1X2. (b) A1X3. (c) A1X4. Lanes A1, authentic xylose to xylohexaose from top to bottom; lanes A2, authentic arabinose. Authentic xylose to xylohexaose was prepared by the method described previously (26). The experimental conditions used are described in Materials and Methods. After 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of incubation at 30°C, 1 μl of each reaction mixture was subjected to thin-layer chromatography.

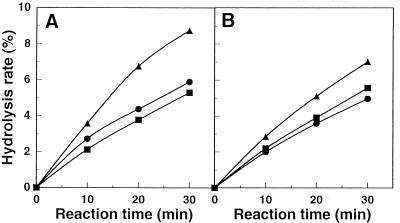

Figure 6 shows the time course of hydrolysis of arabinofuranobiosides by A. awamori IFO 4033 α-l-AFases. Arabinofuranobiosides were hydrolyzed to arabinose and methyl α-l-arabinofuranoside by α-l-AFases I and II. The order of α-l-AFase I hydrolysis of the substrate linkages was (1→5) linkage > (1→3) linkage > (1→2) linkage, and the rates of hydrolysis for 30-min reactions were 8.7, 5.9, and 5.3%, respectively (Fig. 6A). The order of α-l-AFase II hydrolysis of the substrate linkages was (1→5) linkage > (1→2) linkage > (1→3) linkage, and the rates of hydrolysis for 30-min reactions were 7.0, 5.6, and 5.0%, respectively (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Hydrolysis of arabinofuranobiosides. (A) α-l-AFase I. (B) α-l-AFase II. ■, methyl 2-O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside; •, methyl 3-O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside; ▴, methyl 5-O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside. The experimental conditions used are described in Materials and Methods. After 0, 10, 20, and 30 min of incubation at 50°C, the reducing powers formed from arabinose disaccharides were measured by the Somogyi-Nelson method (35).

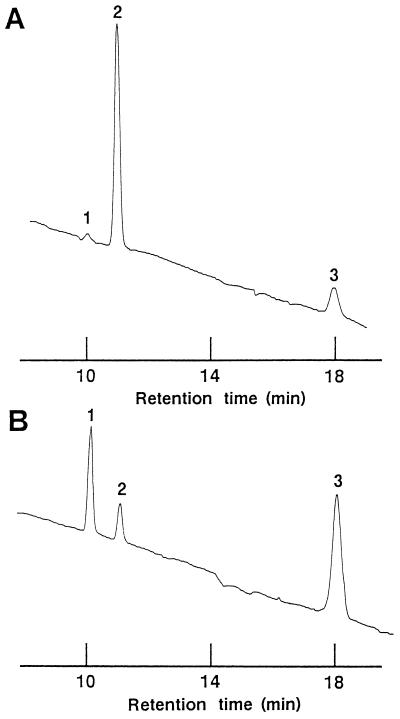

Figure 7 shows the activities of α-l-AFases from A. awamori IFO 4033 with arabinofuranotrioside. α-l-AFase I showed greater hydrolysis of the (1→5) linkage than of the (1→3) linkage (Fig. 7A), whereas α-l-AFase II exhibited a higher hydrolysis rate for the (1→3) linkage than for the (1→5) linkage (Fig. 7B). A total of 92.4% of the trisaccharide was hydrolyzed by α-l-AFase I and 44.2% was hydrolyzed by α-l-AFase II during 3-h incubations.

FIG. 7.

Activities of α-l-AFases from A. awamori IFO 4033 with arabinofuranotrioside. (A) α-l-AFase I. (B) α-l-AFase II. Peak 1, methyl 5-O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside; peak 2, methyl 3-O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside; peak 3, methyl 3,5-di-O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside. The experimental conditions used are described in Materials and Methods. After 3 h of incubation at 30°C, the reaction mixtures containing methyl arabinofuranotrioside were applied to a C18 column.

Table 3 shows the glycosyl linkage compositions of arabinan and α-l-AFase-digested arabinan. α-l-AFase I hydrolyzed arabinan from the nonreducing terminus, and α-l-AFase II preferentially hydrolyzed the arabinosyl side chain of arabinan.

TABLE 3.

Glycosyl linkage compositions of arabinan and enzyme-digested arabinan

| Glycosyl linkage | mol% in:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabinan | Digested arabinan

|

||

| α-l-AFase I | α-l-AFase II | ||

| T-Arafa | 30.1 | 28.3 | 13.1 |

| 3-linked Araf | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| 5-linked Araf | 28.8 | 33.5 | 70.9 |

| 3,5-linked Araf | 28.5 | 33.1 | 8.7 |

| 2,5-linked Araf | 8.5 | 2.6 | 4.4 |

| T-Arap | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

T, nonreducing terminus; Araf, arabinofuranoside; Arap, arabinopyranoside.

DISCUSSION

Rombouts et al. (31) reported that A. niger produced two extracellular α-l-AFases, α-l-AFase A and α-l-AFase B. The substrate specificities of these enzymes have been elucidated for arabinofuranose-containing polysaccharides, 1→5-linked arabinofuranooligosaccharides (31), and various kinds of arabinoxylooligosaccharides (22). Flipphi et al. have cloned the genes of these α-l-AFases (6–8). These α-l-AFases were classified into glycosyl hydrolase families 51 (α-l-AFase A) and 54 (α-l-AFase B) on the basis of amino acid similarities. It is known that the substrate specificity of α-l-AFase A is quite different from that of α-l-AFase B (31). Based on the differences in the substrate specificities of these enzymes, Beldman et al. classified them as Arafur A (α-l-AFase A) and Arafur B (α-l-AFase B) (3). Arafur A is defined as the enzyme which does not exhibit activity with arabinose-containing polysaccharides. In contrast, Arafur B exhibits activity with the polymers.

α-l-AFase A released arabinose from A1X2 and A1X3 (22), as did α-l-AFase I from A. awamori IFO 4033 (Fig. 5A). The N-terminal amino acid sequences of these enzymes were also very similar (Fig. 4). These results show that α-l-AFase I and α-l-AFase A are similar.

α-l-AFase B from A. niger preferentially hydrolyzed arabinofuranosyl side chains from arabinan (31) and released arabinose from A1X2 but not from A1X3 (22). α-l-AFase II from A. awamori IFO 4033 also hydrolyzed arabinosyl side chains in preference to the 1→5-arabinofuranosyl backbone (Table 3). In addition, α-l-AFase II released arabinose from A1X2 and only small amounts of arabinose from A1X3 (Fig. 5B). It is clear that these results are very similar to the results obtained for α-l-AFase B. These types of enzymes are produced by several other organisms, including A. niger K1 (14), A. niger (Megazyme) (29), radishes (10), and B. subtilis (45). The optimum pH of α-l-AFase II from A. awamori was 4.0, and the molecular weight was 62,000 (Fig. 3); these data are almost identical to the data for α-l-AFase B from A. niger (31). The isoelectric point of α-l-AFase II, pI 3.6, was quite different from the pI obtained for α-l-AFase B (pI 4.5 to 5.5) (31). The amino-terminal amino acid sequence of α-l-AFase II (Fig. 4) was, however, very similar to the amino-terminal amino acid sequence of α-l-AFase B (5).

The arabinans analyzed so far are highly branched, with (1→5) links between the main-chain residues, many of which have substitutions at the O-2 and/or O-3 position of single- or multiple-unit side chains (1). Methyl 2-O-, 3-O-, and 5-O-arabinofuranosyl-α-l-arabinofuranosides and methyl 3,5-di-O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside are therefore good substrates for elucidation of the substrate specificity of α-l-AFases.

α-l-AFase I acted on methyl arabinofuranobiosides in the following order: (1→5) linkage > (1→3) linkage > (1→2) linkage (Fig. 6A). The rates of hydrolysis of the arabinofuranobiosides by α-l-AFase II occurred in the following order: (1→5) linkage > (1→2) linkage > (1→3) linkage (Fig. 6B). The Km values for branched arabinan and debranched arabinan for α-l-AFase B from A. niger were 3.7 × 10−3 and 2.9 × 10−3 mol/liter, respectively (31). These results indicate that α-l-AFase B has a slightly higher affinity for the α-(1→5) linkages than has been observed in α-l-AFase II from A. awamori. The linkage preferences in arabinofuranobiosides of α-l-AFases I and II from A. awamori were quite different from those of the α-l-AFases from B. subtilis 3-6 [(1→2) linkage > (1→3) linkage > (1→5) linkage] (16) and from Scopolia japonica [(1→3) linkage > (1→5) linkage] (40).

By using a branched arabinose trisaccharide, we found that α-l-AFase I hydrolyzed the (1→5) linkage faster than it hydrolyzed the (1→3) linkage (Fig. 7A) and that α-l-AFase II hydrolyzed the (1→3) linkage faster than it hydrolyzed the (1→3) linkage (Fig. 7B). Our results are consistent with the enzymatic mode of action with arabinan (Table 3), as follows. α-l-AFase I hydrolyzed arabinan gradually from the nonreducing terminus; in contrast, α-l-AFase II preferentially hydrolyzed the monosaccharide arabinosyl side chains of arabinan. Based on these results, it is apparent that the linkages cleaved preferentially in the branched arabinose trisaccharide by α-l-AFase II are not necessarily related to the linkages cleaved in the various arabinose disaccharides.

α-l-AFases are potentially important for arabinose production from hemicelluloses, and we demonstrated in this study that α-l-AFases from A. awamori IFO 4033 may play a role in this process. We investigated the substrate specificities of α-l-AFases with a limited number of substrates, and it appears that a more effective approach for production of arabinose will be necessary for elucidation of the detailed structure of arabinan and the α-l-AFases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Derek Watt and Pauric J. McGinty, an STA fellow of the National Food Research Institute, for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bacic A, Harris P J, Stone B A. Structure and function of plant cell walls. In: Preiss J, editor. The biochemistry of plants. Vol. 14. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 297–371. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beldman G, Searl-van Leeuwen M J F, De Ruiter G A, Siliha H A, Voragen A G J. Degradation of arabinans by arabinanases from Aspergillus aculeatus and Aspergillus niger. Carbohydr Polym. 1993;20:159–168. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beldman G, Schols H A, Piston S M, Searl-van Leeuwen M J F, Voragen A G J. Arabinans and arabinan degrading enzymes. Adv Macromol Carbohydr Res. 1997;1:1–64. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crous J M, Pretorius I S, van Zyl W H. Cloning and expression of the alpha-l-arabinofuranosidase gene (ABF2) of Aspergillus niger in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;46:256–260. doi: 10.1007/s002530050813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernández-Espinar M T, Peña J L, Piñaga F, Vallés S. α-l-Arabinofuranosidase production by Aspergillus nidulans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;115:107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flipphi M J A, van Heuvel M, van der Veen P, Visser J, de Graaff L H. Cloning and characterization of the abfB gene coding for the major α-l-arabinofuranosidase (ABF B) of Aspergillus niger. Curr Genet. 1993;24:525–532. doi: 10.1007/BF00351717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flipphi M J A, Visser J, van der Veen P, de Graaff L H. Cloning of the Aspergillus niger gene encoding α-l-arabinofuranosidase A. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;39:335–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00192088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flipphi M J A, Visser J, van der Veen P, de Graaff L H. Arabinase gene expression in Aspergillus niger: indications for coordinated regulation. Microbiology. 1994;140:2673–2682. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-10-2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hakomori S. A rapid permethylation of glycolipid and polysaccharide catalyzed by methylsulfinyl carbanion in dimethyl sulfoxide. J Biochem. 1964;55:205–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hata K, Tanaka M, Tsumuraya Y, Hashimoto Y. α-l-Arabinofuranosidase from radish (Raphanus sativus L.) seeds. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:388–396. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.1.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henrissat B, Bairoch A. Updating the sequence-based classification of glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem J. 1996;316:695–696. doi: 10.1042/bj3160695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaji A. l-Arabinosidases. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem. 1984;42:383–394. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaji A, Tagawa K. Purification, crystallization and amino acid composition of α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Aspergillus niger. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;207:456–464. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2795(70)80008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaji A, Tagawa K, Ichimi T. Properties of purified α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Aspergillus niger. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;171:186–188. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(69)90118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaji A, Tagawa K, Matsubara K. Studies on the enzymes acting on araban. VIII. Purification and properties of arabanase produced by Aspergillus niger. Agric Biol Chem. 1967;31:1023–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaneko S, Kusakabe I. Substrate specificity of α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Bacillus subtilis 3-6 toward arabinofuranooligosaccharides. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1995;59:2132–2133. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaneko S, Shimasaki T, Kusakabe I. Purification and some properties of intracellular α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Aspergillus niger 5-16. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1993;57:1161–1165. doi: 10.1271/bbb.57.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaneko S, Sano M, Kusakabe I. Purification and some properties of α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Bacillus subtilis 3-6. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3425–3428. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3425-3428.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaneko S, Kawabata Y, Ishii T, Gama Y, Kusakabe I. The core trisaccharide of α-l-arabinofuranan: synthesis of methyl 3,5-di-O-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside. Carbohydr Res. 1995;268:307–311. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(94)00327-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawabata Y, Kaneko S, Kusakabe I, Gama Y. Synthesis of regioisomeric methyl α-l-arabinofuranobiosides. Carbohydr Res. 1995;267:39–47. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(94)00290-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly M A, Sinnott M L, Widdows D. Preparation of some aryl α-l-arabinofuranosides as substrates for arabinofuranosidase. Carbohydr Res. 1988;181:262–266. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kormelink F J M, Gruppen H, Voragen A G J. Mode of action of (1→4)-β-d-arabinoxylan arabinofuranohydrolase (AXH) and α-l-arabinofuranosidases on alkali-extractable wheat-flour arabinoxylan. Carbohydr Res. 1993;249:345–353. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(93)84099-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroon P A, Williamson G. Release of feruric acid from sugar-beet pulp by using arabinanase, arabinofuranosidase and an esterase from Aspergillus niger. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 1996;23:263–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kusakabe I, Ohgushi S, Yasui T, Kobayashi T. Structures of the arabinoxylo-oligosaccharides from the hydrolytic products of corn cob arabinoxylan by a xylanase from Streptomyces. Agric Biol Chem. 1983;47:2713–2723. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kusakabe I, Yasui T, Kobayashi T. Some properties of araban degrading enzymes produced by microorganisms and enzymatic preparation of arabinose from sugar beet pulp. Nippon Nogeikagaku Kaishi. 1975;49:295–305. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kusakabe I, Yasui T, Kobayashi T. Preparation of crystalline xylooligosaccharides from xylan. Nippon Nogeikagaku Kaishi. 1975;49:383–385. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthew J A, Wyatt G M, Archer D B, Morgan M R A. Purification of a sugar beet pectin modifying enzyme system from Aspergillus niger by antibody affinity column chromatography. Carbohydr Polym. 1991;16:381–390. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCleary B V. Comparison of endolytic hydrolases that depolymerize 1,4-β-d-mannan, 1,5-α-l-arabinan, and 1,4-β-d-galactan. In: Leatham G F, Himmel M E, editors. Enzymes in biomass conversion. Washington, D.C: American Chemical Society; 1991. pp. 437–449. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramón D, van der Veen P, Visser J. Arabinan degrading enzymes from Aspergillus nidulans: induction and purification. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;113:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rombouts F M, Voragen A G, Searl-van Leeuwen M F, Geraeds C C J M, Schols H A, Plinik W. The arabinanases of Aspergillus niger—purification and characterisation of two α-l-arabinofuranosidases and an endo-1,5-α-l-arabinanase. Carbohydr Polym. 1988;9:25–47. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez-Torres P, Gonzalez-Candelas L, Ramon D. Expression in a wine yeast strain of the Aspergillus niger abfB gene. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;145:189–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seri K, Sanai K, Matsuo N, Kawakubo K, Xue C-Y, Inoue S. l-Arabinose selectively inhibits intestinal sucrase in an uncompetitive manner and reduces glycaemic response after sucrose ingestion in animals. Metabolism. 1996;45:1368–1374. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(96)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith P K, Krohn R I, Hermanson G T, Mallia A K, Gartner F H, Provenzano M D, Fujimoto E K, Goeke N M, Olson B J, Klenk D C. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Somogyi M. Notes on sugar determination. J Biol Chem. 1952;195:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tagawa K. Kinetic studies of α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Aspergillus niger. I. General kinetic properties of the enzyme. J Ferment Technol. 1970;48:730–739. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tagawa K. Kinetic studies of α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Aspergillus niger. II. Stability of the enzyme. J Ferment Technol. 1970;48:740–746. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tagawa K, Kaji A. Preparation of l-arabinose-containing polysaccharides and the action of an α-l-arabinofuranosidase on these polysaccharides. Carbohydr Res. 1969;11:293–301. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tagawa K, Terui G. Studies on the enzymes acting on araban. IX. Culture conditions and process of arabanase production by Aspergillus niger. J Ferment Technol. 1968;46:693–700. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka M, Abe A, Uchida T. Substrate specificity of α-l-arabinofuranosidase from plant Scopolia japonica calluses and a suggestion with reference to the structure of beet arabinan. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;658:377–386. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(81)90308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Veen P, Arst H N, Jr, Flipphi M J A, Visser J. Extracellular arabinases in Aspergillus nidulans: the effect of different cre mutations on enzyme levels. Arch Microbiol. 1994;162:433–440. doi: 10.1007/BF00282109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Veen P, Flipphi M J A, Voragen A G J, Visser J. Induction, purification and characterization of arabinanases produced by Aspergillus niger. Arch Microbiol. 1991;157:23–28. doi: 10.1007/BF00245330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Veen P, Flipphi M J A, Voragen A G J, Visser J. Induction of extracellular arabinases on monomeric substrates in Aspergillus niger. Arch Microbiol. 1993;159:66–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00244266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waeghe T J, Darvill A G, McNeil M, Albersheim P. Determination, by methylation analysis, of the glycosyl-linkage compositions of microgram quantities of complex carbohydrates. Carbohydr Res. 1983;123:281–304. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weinstein L, Albersheim P. Structure of plant cell walls. IX. Purification and partial characterization of a wall degrading endoarabanase and arabinosidase from Bacillus subtilis. Plant Physiol. 1979;63:425–432. doi: 10.1104/pp.63.3.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wood T M, McCrae S I. Arabinoxylan-degrading enzyme system of the fungus Aspergillus awamori: purification and properties of an alpha-l-arabinofuranosidase. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;45:538–545. doi: 10.1007/BF00578468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.York W S, Darvill A G, McNeil M, Albersheim P. Isolation and characterization of plant cell walls and cell wall components. Methods Enzymol. 1985;118:3–40. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshida S, Kawabata Y, Kaneko S, Nagamoto Y, Kusakabe I. Detection of α-l-arabinofuranosidase activity in isoelectric focused gels using 6-bromo-2-naphthyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1994;58:580–581. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshida S, Kusakabe I, Matsuo N, Shimizu K, Yasui T, Murakami K. Structure of rice-straw arabinoglucuronoxylan and specificity of Streptomyces xylanase toward the xylan. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54:449–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]