Abstract

Background: This study was conducted to determine the mortality rate and the years of life lost (YLL) due to unintentional poisoning in Fars province in the south of Iran.

Study Design: A cross-sectional study.

Methods: In this study, data from all of the deaths due to unintentional poisoning in the south of Iran between 2004 and 2019 was extracted from the population-based Electronic Death Registry System (EDRS). The Joinpoint Regression method was used to examine the trend of the crude mortality rate, the age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR), and the YLL rate.

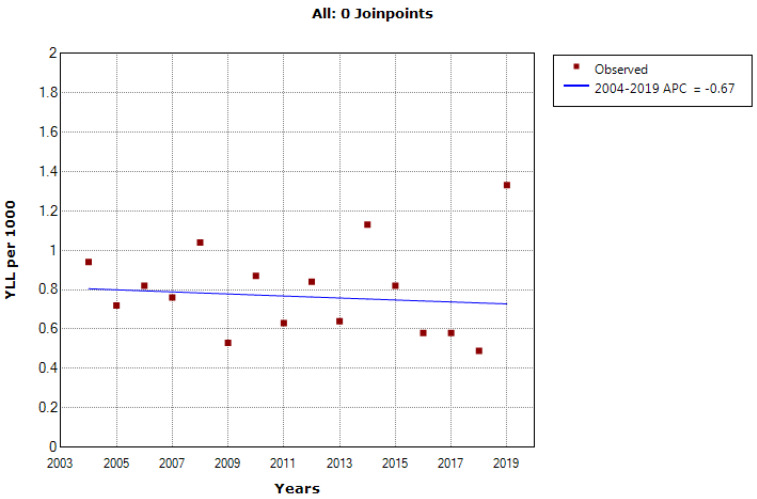

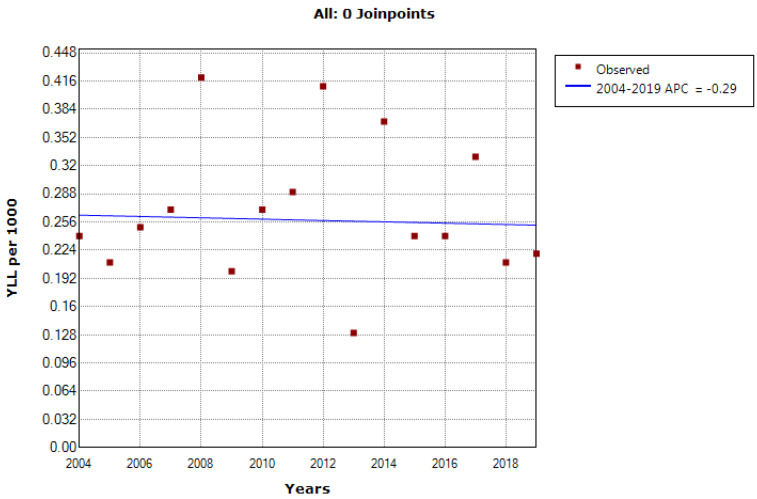

Results: During the 16-year study period (2004-2019), 1466 deaths due to poisoning occurred in Fars province. Of this number, 75.2% (1103 cases) were in men, and 37.5% (550 cases) were in the age group of 15-29 years. The total YLL due to poisoning during the 16-year study period were 25149 and 8392 in men and women, respectively. According to the joinpoint regression analysis, the 16-year trend of YLL rate due to premature mortality was stable. Moreover, the annual percent change (APC) was -0.7% (95% CI: -4.0 to 2.7, P=0.677) for males and - 0.3% (95% CI: -3.8 to 3.3, P=0.862) for females.

Conclusion: The trend of crude mortality rate, ASMR and YLL due to unintentional poisonings was stable. Considering the high rate of mortality and YLL due to unintentional poisoning in the age group of 15-29 years, it is essential to take necessary actions in this age group.

Keywords: Unintentional poisoning, Mortality rate, Years of life lost, Joinpoint regression, Iran

Background

Poisoning is one of the most common injuries and the most common causes of hospitalization in emergency hospitals.1 The increase in the rapid process of industrialization and, subsequently, the increase in the number and types of chemicals have led to a greater prevalence of unintentional poisoning in different societies.2 In low- and middle-income countries, these poisonings can be much more serious following the consumption of kerosene, herbal medicines, insecticides, or herbicides.3 It affects all races and all ages and remains a leading cause of unintentional injury which may lead to permanent disability requiring long-term medical care.2 In 2020, adolescent deaths from unintentional drug overdoses surpassed deaths from cancer, among other leading causes of death.4 In 2015, the total cost of drug poisoning deaths among adolescents and young adults was estimated at $35.1 billion United States.5 In 2015, unintentional poisonings caused 86,400 deaths worldwide, with a mortality rate of 1.2 per 100 000.6 In an analysis of vital statistics in Canada (except one province) conducted from 2001 to 2007, unintentional poisonings were one of the three leading causes of death from unintentional injuries, and the rate of these poisonings was higher in men than in women.7 From 1999 to 2016 in the United States, changes in unintentional poisoning death rates showed increases for all racial/ethnic and age subgroups, most notably among whites in the 20-34 age group, and it also had a large increase in women, although it was less than men.8 In an epidemiological study related to unintentional poisoning with carbon monoxide (CO) gas in northwest Iran, the proportion of unintentional poisoning related to CO in relation to all poisonings was 11.6%.9

Unintentional poisonings are significantly preventable and are important for public health. Years of life lost (YLL) is an epidemiological estimate of premature death. However, the burden caused by unintentional poisoning in low-income countries and different regions has not been well investigated.10 Therefore, various studies are vital for planning, preventive interventions, and optimizing the distribution of available resources. This study was conducted to determine the mortality rate and the YLL from unintentional poisoning in Fars province in the south of Iran.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Fars province during 2004-2019. We extracted all deaths from unintentional poisonings from the population-based Electronic Death Registry System (EDRS) by age, gender, and year of death and based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10. The codes used in this study were X40-X49. In the population-based electronic death registration system, all available sources were used to detect, record, and collect information about death, and then deaths that were repeated in records were excluded from the study. Inclusion criteria included death due to unintentional poisoning and being a resident of Fars province.

The total estimated population of Fars province has been estimated using the basic data of health centers and the population and housing census from 1996 to 2016, taking into account the annual growth of the population. For standardization, the standard population of 2013 for countries with low and moderate incomes was used.11

Statistical analysis

First, crude and age-standardized mortality rates (ASMR) of unintentional poisonings were calculated according to gender and year of death during the study years. Then, to calculate YLL, the standard life table was used, life expectancy for different age and gender groups was determined, and the number of deaths due to unintentional poisoning in each age and gender group was estimated based on the following relationship calculation12:

YLL = N Ce(ra)/ (β + r)2 [e -(β + r)(L + a)[-(β + r) (L + a)-1] – e–(β + r)a [–(β + r) a-1]]

N = Number of deaths in a specified age and gender group

L = Life expectancy of death cases again in that age and gender group

r = Discounting Rate, which equals 0.03.

β = A conventional rate in calculating age value which equals 0.04.

C = An adjusted constant value that equals 0.1658.

a = The age on which death occurred

e = A constant value considered as 2.71.

First, the YLL were calculated according to 18 age groups: 0-4, 5-9, 10-14, up to 85 years old, and then based on age groups 0-4, 5-14, 15-29, 30-44, 45-59, 60-69, 70-79, and over 80 years were shown in a figure.

The analysis of the number of YLL due to premature death from unintentional poisonings was performed using the YLL template of 2015 (https://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.searo.60760?lang=en), World Health Organization (WHO) in Excel version 2016 spreadsheet software.

To examine the trend of crude, ASMR, and YLL rate for different years, joinpoint regression based on the log-linear model was used. The joinpoint regression analysis describes changing trends over successive segments of time and the amount of increase or decrease within each segment. The resulting line segment between joint points is described by the annual percent change (APC) that is based on the slope of the line segment and the average annual percent change (AAPC). The joinpoint regression program 4.9.1.0 carried out the analysis for the trend, and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The protocol of this study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. All aspects of the study were conducted according to the university’s code of ethics.

Results

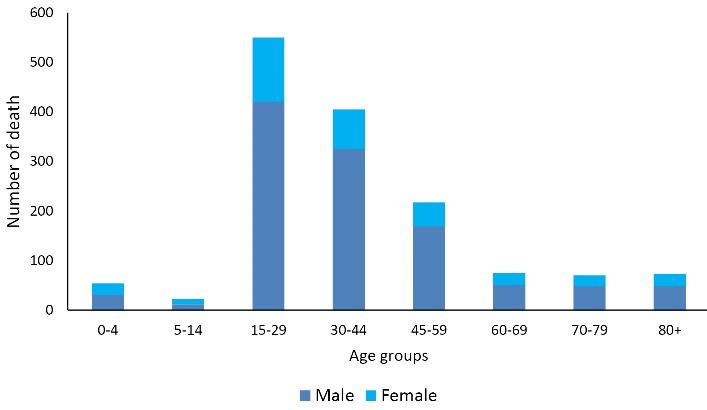

During the 16-year study period (2004-2019), 1466 deaths due to poisoning occurred in Fars province. Of this number, 75.2% (1103 cases) were in men, and 37.5% (550 cases) were in the age group of 15-29 years. As can be seen in Table 1, the crude mortality rate due to poisoning in men increased from 4.73 (per 100 000 population) in 2004 to 5.84 per 100 000 population in 2019 (P for trend = 0.593, AAPC = -0.8%) and in women from 0.90 (per 100 000 population) in 2004 to 1.07 (per 100 000 population) in 2019. Furthermore, the ASMR had a stable trend in men from 4.73 per 100 000 in 2004 to 4.73 per 100 000 in 2019 (AAPC = -1.4%, P for trend = 0.349), and it increased from 0.83 per 100 000 population in 2004 to 0.96 per 100 000 in 2019 (AAPC = 0.8%, P for trend = 0.635) in women (Table 1). Moreover, the highest and lowest number of deaths in both genders were in the age groups of 15-29 years and 5-14 years, respectively (Figure 1).

Table 1. Crude and ASMR per 100 000 population and YLL due to poisoning by gender and year in Fars province during 2004-2019 .

| Year | No. of Death | Crude Mortality Rate | ASMR (95% CI) | YLL | ||||||

| No. | (Per 1000) | |||||||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| 2004 | 80 | 16 | 4.73 | 0.90 | 4.73 (3.79,5.67) | 0.83 (0.39,1.27) | 1749 | 427 | 0.94 | 0.24 |

| 2005 | 57 | 16 | 3.07 | 0.89 | 2.90 (2.10,3.70) | 0.88 (0.44,1.32) | 1351 | 385 | 0.72 | 0.21 |

| 2006 | 65 | 18 | 3.51 | 0.99 | 3.30 (2.44,4.15) | 0.93 (0.47,1.39) | 1520 | 456 | 0.82 | 0.25 |

| 2007 | 63 | 21 | 3.37 | 1.14 | 3.12 (2.29,3.95) | 0.99 (0.50,1.48) | 1435 | 507 | 0.76 | 0.27 |

| 2008 | 83 | 32 | 4.39 | 1.72 | 3.77 (2.82,4.72) | 1.64 (1.04,2.23) | 1977 | 790 | 1.04 | 0.42 |

| 2009 | 48 | 19 | 2.51 | 1.01 | 2.28 (1.56,2.99) | 0.95 (0.50,1.41) | 1014 | 383 | 0.53 | 0.20 |

| 2010 | 72 | 20 | 3.74 | 1.05 | 3.12 (2.26,3.99) | 0.98 (0.51,1.44) | 1680 | 517 | 0.87 | 0.27 |

| 2011 | 57 | 23 | 2.93 | 1.19 | 2.68 (1.92,3.44) | 1.28 (0.79,1.77) | 1227 | 560 | 0.63 | 0.29 |

| 2012 | 77 | 39 | 3.91 | 2.00 | 3.51 (2.64,4.39) | 1.81 (1.18,2.44) | 1667 | 803 | 0.84 | 0.41 |

| 2013 | 54 | 13 | 2.70 | 0.66 | 2.44 (1.72,3.16) | 0.59 (0.23,0.95) | 1288 | 267 | 0.64 | 0.13 |

| 2014 | 97 | 33 | 4.79 | 1.66 | 4.36 (3.40,5.31) | 1.47 (0.90,2.03) | 2290 | 748 | 1.13 | 0.37 |

| 2015 | 71 | 22 | 3.46 | 1.09 | 3.01 (2.20,3.81) | 1.00 (0.54,1.45) | 1691 | 493 | 0.82 | 0.24 |

| 2016 | 55 | 23 | 2.64 | 1.13 | 2.39 (0.61,1.54) | 1.07 (0.61,1.54) | 1210 | 489 | 0.58 | 0.24 |

| 2017 | 54 | 27 | 2.59 | 1.33 | 2.40 (1.70,3.09) | 1.34 (0.84,1.85) | 1218 | 679 | 0.58 | 0.33 |

| 2018 | 47 | 19 | 2.24 | 0.93 | 2.03 (1.39,2.68) | 0.93 (0.51,1.36) | 1029 | 438 | 0.49 | 0.21 |

| 2019 | 123 | 22 | 5.84 | 1.07 | 4.73 (3.70,5.76) | 0.96 (0.51,1.41) | 2803 | 450 | 1.33 | 0.22 |

| Total | 1103 | 363 | 3.50 | 1.17 | 3.13 (2.93,3.34) | 1.12 (1.00,1.24) | 25149 | 8392 | 0.79 | 0.27 |

| P-value | - | - | 0.593 | 0.658 | 0.349 | 0.635 | - | - | 0.677 | 0.862 |

Note. ASMR: Age-standardized mortality rate; YLL: Years of life lost; No: Number; CI: Confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Number of deaths due to unintentional poisoning by gender and age groups

Temporal trends of poisoning mortality by age groups

In the 0–44 age group, the poisoning mortality rate had decreasing trends in men (AAPC = –0.4%, P = 0.833) and women (AAPC = –1.2%, P = 0.511), but these trends were not statistically significant. In the 45–59 age group, there were increasing trends in men (AAPC = 1.9%, P = 0.384) and women (AAPC = 4.7%, P = 0.019), which were not statistically significant. Moreover, in the 60–74 age group, there were decreasing trends in men (AAPC = -6.01%, P = 0.091) and women (AAPC = -1.2%, P = 0.568), but these trends were not statistically significant. Likewise, in the + 75 age group, there were decreasing trends in men (AAPC = -6.3%, P = 0.081) and women (AAPC = -4.4%, P = 0.327), but these trends were not statistically significant.

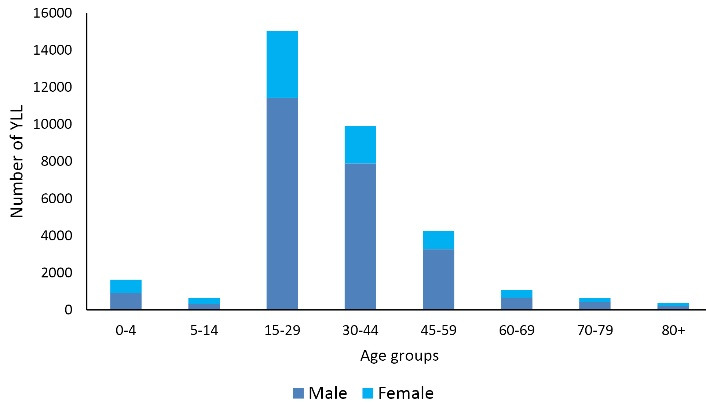

Temporal trends of poisoning years of life lost rate

As depicted in Table 1, the total YLL due to poisoning during the 16-year study period was 25149 (0.79 per 1000 people) in men, 8392 (0.27 per 1000 people) in women, and 33541 (53.0 per 1000 people) in both genders (Male/female gender ratio = 2.99). The average number of YLLs due to unintentional poisoning was 22.8 years in men and 23.1 years in women, and the highest and lowest YLLs in both genders were in the age groups of 15-29 years and above 80 years, respectively, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

YLL due to unintentional poisoning by gender and age groups.

Note. YLL: Years of life lost

According to the joinpoint regression analysis, the 16-year trend of the YLL rate due to premature mortality was stable. The APC was -0.7% (95% confidence interval [CI]: -4.0 to 2.7, P = 0.677) for males and -0.3% (95% CI: -3.8 to 3.3 P = 0.862) for females. The model did not show any joinpoint; hence, the AAPC was the same as the APC (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

The trend of the number of YLL due to unintentional poisoning in men during 2004-2019. Note. YLL: Years of life lost

Figure 4.

The trend of the number of YLL due to unintentional poisoning in women during 2004-2019. Note. YLL: Years of life lost.

Discussion

The present study was conducted to investigate the mortality rate and YLL caused by unintentional poisoning in Fars province during 2004-2019. During the 16-year study period, 1,466 deaths due to poisoning occurred in Fars province, and the total YLL was estimated to be 25 149. In other studies, these numbers were reported to be higher. For example, in the United States, a total of 21 689 youth (aged 10–24) died of unintentional drug overdoses, and youth experienced a total of 1 227 223.58 YLLs during the 5-year study period (2015–2019).13 In China. the number of unintentional poisoning deaths decreased from 43,601 (in 1990) to 22,274 (in 2015), and the death rate decreased from 4.1 per 100 000 to 1.6 per 100 000 which indicates a decrease of 61.8%,2 while in our study, the trend of crude mortality in both genders was increasing. In the evaluation of patients who died from aluminum phosphide (rice tablets) in two years in Iran, the trend of crude mortality showed an increasing trend.14 Additionally, Hempstead and Phillips reported that the mortality rate from unintentional drug poisoning also increased by approximately 126% from 2005 to 2016.15 The high rate of mortality due to poisoning can have various causes such as improper use of medicine,16 use of pesticides,17 changes in the availability of drugs,18 access to medical centers, weak pre-hospital care, and the like,19 so there is an important point that poisoning requires a disinfection method to be done as soon as possible.20

One study reported that the ASMR of death from acute pesticide poisoning decreased from 5.8 per 100 000 in 2006 to 1.6 per 100 000 in 2014 which was greater in men,21 but in our study, this measurement was stable in men and increased in women. There may be several reasons for the declining trend of mortality. For example, better access to health care services may have occurred due to increased urbanization22 or weak to non-existent surveillance system for poisoning exposures and inappropriate definition of poisoning cause undercounting.23 Another study demonstrated that men have more ASMR of death due to unintentional poisonings than women.15 In line with our study, Onyeka demonstrated a higher YLL rate in men compared to women.24 Higher mortality and consequently more YLL in men could be because this group has more access to toxic substances.25 Other research has suggested that the higher death rate in men than in women may be due to their greater involvement in risky behaviors such as working with tools, burning fuel, or consuming alcohol or working more at risky conditions.9

Unlike our study, YLL due to poisoning increased during the 16-year study period in both genders, but in Tang’s study, there was a downward trend until 2015.2 A study conducted in Mexico on YLL of alcohol revealed that YLL in men and women peak in the age groups of 45-49 years and 50-54 years, respectively.26 Besides, in a study conducted in Iran, the results illustrated that during 10 years (2004-2013), the age group of 15-29 had the highest amount of YLL in both genders,27 and the present study also obtained similar results in this regard. It may indicate increased mortality in future years for all ages,4 and the highest burden of disease will be on the shoulders of the youngest and most active people in society; hence, taking measures to reduce or better manage patients will have a great impact on social welfare.27 On the other hand, this age group is considered to be an active part of the society, and they are facing more dangers due to their greater presence in society and higher risk-taking.

The findings of this study have important implications for policymaking and the development of appropriate poisoning interventions. If resources are limited, YLL may particularly help policymakers target premature death subpopulations and set top priorities for programs related to the prevention of premature death.28 For example, uninformed and incorrect social attitudes toward the recreational use of prescription opioids may be a reason for the widespread use of drugs. Furthermore, despite the common belief that poisoning is solely the result of heavy alcohol or drug use, the findings of Yoon and colleagues’ study suggested that poisoning is more likely due to chronic substance use disorders and mood and anxiety disorders.29 Greater symptom severity or the availability of psychiatric medications can lead to higher risks for accidental poisoning in people with a major mental health disorder.2 Therefore, it is suggested that poison control centers with telephonic advice services should be readily available to handle poisoning cases with confidence,19 or people should be provided with sufficient training regarding the correct way and amount of using medicine or chemicals.30 Additionally, it is important to know that research and policy attention to poisoning has been relatively low compared to the magnitude of the problem, especially among young people, so further studies are recommended.

A limitation of the present study was that YLL was not evaluated throughout Iran due to the unavailability of the necessary data. In addition, the data used in this study were not sufficient to determine the specific risk factors of unintentional poisoning in South Asian countries. However, this study has a large sample size and an extensive time period for data analysis.

Highlights

During the 16 years of study (2004-2019), 1466 deaths occurred in Fars province due to Unintentional poisoning.

The total YLL due to poisoning during the 16-year study period were 25,149 in men and 8392 in women.

According to the joinpoint regression analysis, the 16-year trend of YLL rate due to premature mortality was stable in both genders.

Conclusion

During the study period, the trend of crude and standardized mortality rates and YLL due to unintentional poisonings has been stable. Considering the high rate of mortality and YLL due to unintentional poisoning in the age group of 15-29 years, it is essential to take necessary actions in this age group.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Health Vice-chancellor at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Habibollah Azarbakhsh, Alireza Mirahmadizadeh.

Data curation: Fatemeh Jafari, Jafar Hassanzadeh.

Formal analysis: Habibollah Azarbakhsh.

Funding acquisition: Alireza Mirahmadizadeh.

Investigation: Alireza Mirahmadizadeh.

Methodology: Habibollah Azarbakhsh.

Project administration: Jafar Hassanzadeh, Seyed Parsa Dehghani.

Software: Habibollah Azarbakhsh.

Supervision: Habibollah Azarbakhsh.

Validation: Habibollah Azarbakhsh, Fatemeh Jafari, Hamed Karami.

Visualization: Jafar Hassanzadeh, Seyed Parsa Dehghani.

Writing–original draft: Habibollah Azarbakhsh, Fatemeh Jafari, Hamed Karami, Seyed Parsa Dehghani.

Writing–review & editing: Habibollah Azarbakhsh, Fatemeh Jafari, Seyed Parsa Dehghani, Hamed Karami, Jafar Hassanzadeh, Alireza Mirahmadizadeh.

Competing Interests

The authors announce that they have no conflict of interests in the publication of this study. The Local Ethics Committee approval was also obtained.

Funding

None.

Please cite this article as follows: Azarbakhsh H, Jafari F, Dehghani SP, Karami H, Hassanzadeh J, Mirahmadizadeh A. Trend analysis of deaths with unintentional poisoning and years of life lost in the South of Iran: 2004-2019. J Res Health Sci. 2023; 23(3):e00588. doi:10.34172/jrhs.2023.123

References

- 1.GBD 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1603–58. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31460-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang Y, Zhang L, Pan J, Zhang Q, He T, Wu Z, et al. Unintentional poisoning in China, 1990 to 2015: the global burden of disease study 2015. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(8):1311–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2017.303841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer S, Eddleston M, Bailey B, Desel H, Gottschling S, Gortner L. Unintentional household poisoning in children. Klin Padiatr. 2007;219(5):254–70. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermans SP, Samiec J, Golec A, Trimble C, Teater J, Hall OT. Years of life lost to unintentional drug overdose rapidly rising in the adolescent population, 2016-2020. J Adolesc Health. 2023;72(3):397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali B, Fisher DA, Miller TR, Lawrence BA, Spicer RS, Swedler DI, et al. Trends in drug poisoning deaths among adolescents and young adults in the United States, 2006-2015. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80(2):201–10. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2019.80.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459-544. 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Chen Y, Mo F, Yi QL, Jiang Y, Mao Y. Unintentional injury mortality and external causes in Canada from 2001 to 2007. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2013;33(2):95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Kerr WC. Shifting patterns of disparities in unintentional injury mortality rates in the United States, 1999-2016. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2021;45:e36. doi: 10.26633/rpsp.2021.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nazari J, Dianat I, Stedmon A. Unintentional carbon monoxide poisoning in Northwest Iran: a 5-year study. J Forensic Leg Med. 2010;17(7):388–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bose A, Konradsen F, John J, Suganthy P, Muliyil J, Abraham S. Mortality rate and years of life lost from unintentional injury and suicide in South India. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11(10):1553–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sankoh O, Sharrow D, Herbst K, Whiteson Kabudula C, Alam N, Kant S, et al. The INDEPTH standard population for low- and middle-income countries, 2013. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:23286. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.23286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azarbakhsh H, Sharifi MH, Hassanzadeh J, Dewey RS, Janfada M, Mirahmadizadeh A. Diabetes in southern Iran: a 16-year follow-up of mortality and years of life lost. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2023;43(4):574–80. doi: 10.1007/s13410-022-01125-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall OT, Trimble C, Garcia S, Entrup P, Deaner M, Teater J. Unintentional drug overdose mortality in years of life lost among adolescents and young people in the US from 2015 to 2019. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(4):415–7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.6032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Pajoumand A. Two years epidemiological survey of aluminum phosphide poisoning in Tehran. Iran J Toxicol. 2007;1(1):35–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hempstead K, Phillips J. Divergence in recent trends in deaths from intentional and unintentional poisoning. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38(1):29–35. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan N, Pérez-Núñez R, Shamim N, Khan U, Naseer N, Feroze A, et al. Intentional and unintentional poisoning in Pakistan: a pilot study using the emergency departments surveillance project. BMC Emerg Med. 2015;15(Suppl 2):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-227x-15-s2-s2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turabi A, Danyal A, Hasan S, Durrani A, Ahmed M. Organophosphate poisoning in the urban population; study conducted at national poison control center, Karachi. Biomedica. 2008;24(2):124–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coffin PO, Galea S, Ahern J, Leon AC, Vlahov D, Tardiff K. Opiates, cocaine and alcohol combinations in accidental drug overdose deaths in New York City, 1990-98. Addiction. 2003;98(6):739–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan NU, Mir MU, Khan UR, Khan AR, Ara J, Raja K, et al. The current state of poison control centers in Pakistan and the need for capacity building. Asia Pac J Med Toxicol. 2014;3(1):31–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goldfrank LR, Hoffman RS. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. McGraw-Hill; 2006.

- 21.Ko S, Cha ES, Choi Y, Kim J, Kim JH, Lee WJ. The burden of acute pesticide poisoning and pesticide regulation in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(31):e208. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mittal N, Shafiq N, Bhalla A, Pandhi P, Malhotra S. A prospective observational study on different poisoning cases and their outcomes in a tertiary care hospital. SAGE Open Med. 2013;1:2050312113504213. doi: 10.1177/2050312113504213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan NU, Fayyaz J, Khan UR, Feroze A. Importance of clinical toxicology teaching and its impact in improving knowledge: sharing experience from a workshop. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63(11):1379–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onyeka IN, Beynon CM, Vohlonen I, Tiihonen J, Föhr J, Ronkainen K, et al. Potential years of life lost due to premature mortality among treatment-seeking illicit drug users in Finland. J Community Health. 2015;40(6):1099–106. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cha ES, Khang YH, Lee WJ. Mortality from and incidence of pesticide poisoning in South Korea: findings from National Death and Health Utilization Data between 2006 and 2010. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pérez-Pérez E, Cruz-López L, Hernández-Llanes NF, Gallegos-Cari A, Camacho-Solís RE, Mendoza-Meléndez M. Years of life lost (Yll) attributable to alcohol consumption in Mexico City. Cien Saude Colet. 2016;21(1):37–44. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232015211.09472015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asadi R, Afshari R. Ten-year disease burden of acute poisonings in northeast Iran and estimations for national rates. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2016;35(7):747–59. doi: 10.1177/0960327115604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azarbakhsh H, Hassanzadeh J, Dehghani SS, Janfada M, Sharifi MH, Mirahmadizadeh A. Trend analysis of homicide mortality and years of life lost in the south of Iran, 2004-2019. J Res Health Sci. 2023;23(1):e00573. doi: 10.34172/jrhs.2023.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoon YH, Chen CM, Yi HY. Unintentional alcohol and drug poisoning in association with substance use disorders and mood and anxiety disorders: results from the 2010 Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Inj Prev. 2014;20(1):21–8. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ford MD. Unintentional poisoning in North Carolina: an emerging public health problem. N C Med J. 2010;71(6):542–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]