Abstract

Background

Cell culture conditions during manufacturing can impact the clinical efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell products. Production methods have not been standardized because the optimal approach remains unknown. Separate CD4+ and CD8+ cultures offer a potential advantage but complicate manufacturing and may affect cell expansion and function. In a phase 1/2 clinical trial, we observed poor expansion of separate CD8+ cell cultures and hypothesized that coculture of CD4+ cells and CD8+ cells at a defined ratio at culture initiation would enhance CD8+ cell expansion and simplify manufacturing.

Methods

We generated CAR T cells either as separate CD4+ and CD8+ cells, or as combined cultures mixed in defined CD4:CD8 ratios at culture initiation. We assessed CAR T cell expansion, phenotype, function, gene expression, and in vivo activity of CAR T cells and compared these between separately expanded or mixed CAR T cell cultures.

Results

We found that the coculture of CD8+ CAR T cells with CD4+ cells markedly improves CD8+ cell expansion, and further discovered that CD8+ cells cultured in isolation exhibit a hypofunctional phenotype and transcriptional signature compared with those in mixed cultures with CD4+ cells. Cocultured CAR T cells also confer superior antitumor activity in vivo compared with separately expanded cells. The positive impact of CD4+ cells on CD8+ cells was mediated through both cytokines and direct cell contact, including CD40L-CD40 and CD70-CD27 interactions.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that CD4+ cell help during cell culture maintains robust CD8+ CAR T cell function, with implications for clinical cell manufacturing.

Keywords: Receptors, Chimeric Antigen; Cell Engineering; CD8-Positive T-Lymphocytes; CD4-CD8 Ratio; Immunotherapy, Adoptive

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

Selection of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, expanding in separate cultures, and infusing at a defined ratio overcomes the negative impact of contaminating myeloid cells that occurs with manufacturing chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell products from unselected peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). However, this adds cost and complexity to manufacturing. Additionally, while the impact of CD4+ cell help on CD8+ cells in vivo is known, whether CD4+ cells impact CD8+ cell function in ex vivo T cell cultures, in the absence of antigen presenting cells, has not been well studied.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study provides new insights that CD8+ CAR T cells expanded in the absence of CD4+ cell help exhibit a hypofunctional phenotype, and that this is rescued by coculture with CD4+ cells, which impact CD8+ cell function and phenotype through cytokines as well as cell-contact dependent mechanisms, including CD40L-CD40 and CD70-CD27 interactions.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Our data suggest that the function of separately cultured CD8+ CAR T cells can be improved by coculturing with CD4+ cells. Additionally, together with previous data demonstrating benefits of CD4+ and CD8+ selection over the use of unselected PBMC, our results suggest that combining CD4+ and CD8+ cells at a defined ratio at culture initiation may be a more effective method of CAR T cell manufacturing than the most common methods currently in use.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy has demonstrated promising but inconsistent potency in the treatment of hematological malignancies,1–5 with sustained remissions remaining elusive for the majority of patients. Since phenotypic features of infused CAR T cells correlate with clinical potency,6–9 optimizing cell culture conditions may improve the function of infused cells.

Several previous studies have demonstrated advantages of generating CAR T cell products from selected T cells rather than unselected peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). One limitation of using unselected PBMC is that contaminating myeloid cells negatively impact cultured T cells,10 11 a problem that can be overcome by starting manufacturing with enriched T cells.11–13

In addition to improving manufacturing yields, T cell selection also appears to increase the potency of the final product. CD3+ enrichment generates CAR T cells with a higher fraction of naïve and central memory phenotype and improved cytotoxic function compared with products generated from unselected PBMC.14 In the clinical setting, products made from CD4/CD8-selected cells were associated with improved CAR T cell expansion, peak cytokine levels, and clinical responses compared with those generated from unselected PBMCs.12 Additionally, T-cell selection minimizes the risk that contaminating tumor cells are transduced with the CAR construct, potentially leading to antigen masking and subsequent relapse by functionally antigen-negative disease.15

Controlling the relative fractions of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in the infused product may have additional benefits. Patients with B-cell malignancies have highly variable ratios of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in the blood6 16 and in CAR T cell products.6 12 In animal models, infusing separately cultured CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cells at a defined ratio significantly improves antitumor activity compared with unselected T cells.16 17 In the clinical setting (lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel)), defined-ratio products yield clinical safety and efficacy outcomes that compare favorably with unselected CAR T cell products.1 2 4

The apparently superior efficacy of liso-cel compared with tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel),18–20 another CD19-targeted 4-1BB-containing CAR T cell product that involves simple CD3+ enrichment during manufacturing, supports the concept of a more controlled CD4:CD8 ratio of infused CAR T cells. Although a CD4:CD8 ratio of 1:1 yielded the best results in animal models, 3:1 and 1:3 (but not 9:1 or 1:9) ratios led to improved survival compared with unfractionated cells,17 suggesting that there is an optimal effective range of CD4:CD8 ratios.

Collectively, these data supported our decision to manufacture clinical products through parallel CD4+ and CD8+ cell cultures, subsequently formulated for infusion at a 1:1 ratio, in a phase 1/2 clinical trial evaluating third-generation CD20-targeted CAR T cells (NCT03277729).21 22 Surprisingly, we observed suboptimal growth of CD8+ cell cultures from the initial patients in this trial. Based on the physiological role played by CD4+ cells during CD8+ cell priming and clonal expansion under some conditions,23–25 we hypothesized that CD8+ cell proliferation may be impaired in the absence of CD4+ support during ex vivo cell culture and explored the impact of combining CD4+ and CD8+ cells at various defined ratios at the initiation of cell manufacturing. We report here that CD8+ cells manufactured in separate cultures exhibit inferior ex vivo expansion, a hypofunctional phenotype, and aberrant gene expression signature, all of which can be avoided through coculture with CD4+ cells. The mechanisms underlying these findings involved both cytokine-mediated and contact-dependent mechanisms involving CD40L-CD40 and CD70-CD27 interactions.

Results

CD8+ expansion and final cell product composition depend on initial CD4:CD8 ratio

To evaluate the impact that combining CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at different ratios at culture initiation has on expansion and CD4:CD8 composition of the final CAR T cell product, we isolated CD4+ and CD8+ cells from cryopreserved PBMCs collected from healthy donors and patients with relapsed B-cell lymphomas. The cells were activated, mixed at various CD4:CD8 ratios, transduced with 1.5.3-NQ-28-BB-z (third-generation anti-CD20 CAR) lentiviral vector, restimulated at day 7 with an irradiated CD20+ cell line to boost growth and enrich CAR+ cells, and harvested at days 14–15, concordant with the manufacturing process used at the initiation of our ongoing clinical trial. We measured expression of CD4, CD8, and truncated CD19 (tCD19, a marker of transduction encoded in the lentiviral vector26 (online supplemental figure 6D) by flow cytometry and counted cells at day 7 prior to restimulation and at the end of production on day 14.

jitc-2023-007803supp002.pdf (21MB, pdf)

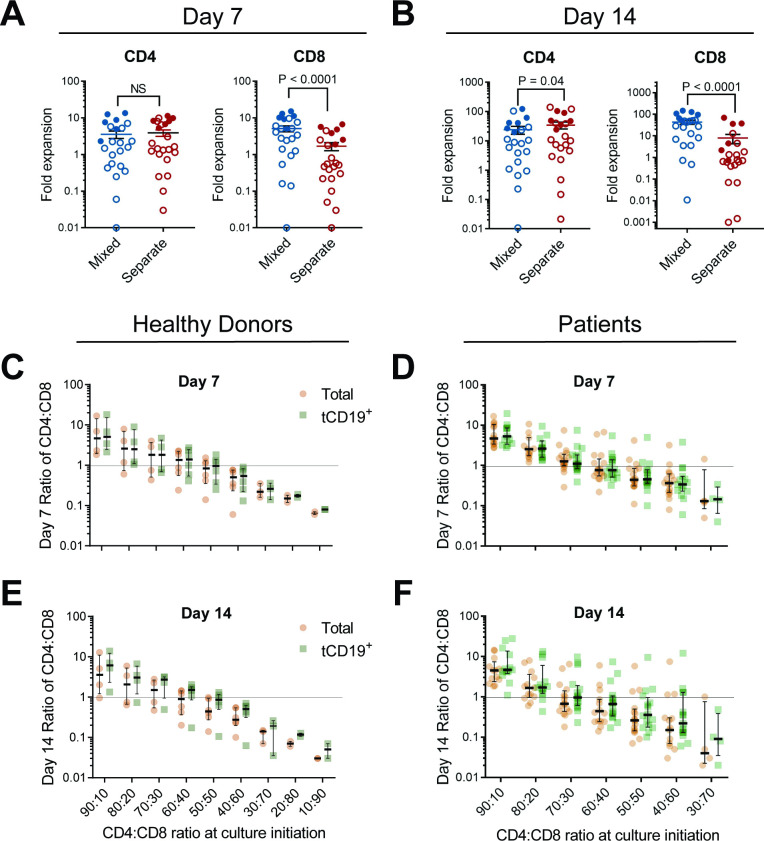

We observed significantly higher fold expansion at both day 7 and day 14 of CD8+ CAR T cells mixed with CD4+ cells compared with CD8+ cells cultured in isolation, for both healthy donors and patients (figure 1A,B, online supplemental figure 1). The expansion of CD8+ cells was positively correlated to increasing fractions of CD4+ cells, and CD4+ cell expansion was largely unaffected by coculture. The fraction of CD4+ and CD8+ cells at the end of manufacturing was proportional to the starting ratios (figure 1C–F, online supplemental figure 2).

Figure 1.

Effect of coculture of CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cells on cell growth and composition of cell products. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were isolated from apheresis products from healthy donors or patients, activated by anti-CD3/CD28 beads, cultured as either CD4+ cells only, CD8+ cells only, or a 60:40 CD4:CD8 ratio of mixed cells. Cells were transduced with 1.5.3-NQ-28-BB-z anti-CD20 CAR lentiviral vector and restimulated on day 7 with irradiated CD20+ LCL cells. At day 7 prior to restimulation and again at day 14, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for CD4, CD8, and tCD19 transduction marker expression. The fold expansion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets expanded in separate (red) or in mixed (blue) cultures is shown for cells harvested (A) at day 7 prior to restimulation (n=23: 17 patients (open circles) and 6 healthy donors (filled circles)), or (B) at day 14 following restimulation (n=22: 16 patients (open circles) and 6 healthy donors (filled circles)). Bars represent the median±SEM. For C–F, cells were cultured as in A, B but at a variety of CD4:CD8 ratios from healthy donors (n=4 for 90:10, 80:20, and 70:30, n=6 for ratios 60:40, 50:50, and 40:60, n=3, for 30:70, n=2 for 20:80 and 10:90) or lymphoma patients (n=13 for day 7 ratios 90:10 and 80:20, n=17 for 70:30, 60:40, 50:50, and 40:60, n=5 for 30:70; day 14 n was equivalent to day 8 n−1). The ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ cells at day 7 (C, D) or day 14–15 (E, F) for total T cells (orange) or gated on tCD19+ T cells (green) is shown. The median ratios with IQR are shown along with individual values. NS, not significant.

The final CD4:CD8 ratios of the transduced (tCD19+) T cells were similar to those of the total cell population (figure 1C–F), excluding the possibility that there were differences in transduction efficiency between CD4+ and CD8+ cells. The starting ratio that yielded a final median CD4:CD8 ratio of tCD19+ cells closest to 1 was 50:50 for healthy donors both at day 7 (0.96) and day 14 (0.86), and 70:30 for patients at both day 7 (1.1) and day 14 (0.97) (figure 1C–F).

The superior CD8+ cell expansion in the presence of CD4+ cells allowed us to modify the manufacturing process to eliminate the restimulation step and shorten the cell culture time to 8–9 days. Using this process, we similarly found that CD8+ CAR T cells expanded in mixed cultures exhibited approximately a threefold higher median expansion than cells cultured in the absence of CD4+ cells (online supplemental figure 3).

To evaluate whether these results were a function of the CD20 third generation CAR construct, we repeated the experiments using a second-generation CD19-targeted CAR (hCD19-BB-z). We similarly observed significantly higher fold expansion in mixed cultures of CD8+ T cells transduced with the CD19 CAR or even an empty vector, comparable to the effect with the CD28-41BB CD20-targeted CAR (online supplemental figure 4). We conducted additional experiments using second-generation CAR T cells with a CD28 costimulatory domain. As with the previous experiments, we found that CD8+ T cells modified with the 1.5.3-NQ-28-z CD20 CAR exhibited significantly higher fold expansion when cocultured with CD4+ cells than when cultured separately (online supplemental figure 5).

Impact of mixed cultures on CAR T cell immunophenotype

Given these profound effects of CD4+ cells on CD8+ CAR T cell expansion, we inquired whether CD8+ cells might also exhibit phenotypic and functional differences. As noted above, we employed two manufacturing processes: (1) a process of 14–15 days involving a restimulation step with CD20+ target cells at day 7 and (2) a process of 8–9 days without a restimulation step. While we have since adopted the second process for use both in the laboratory and in our clinical trial, the first process provides an opportunity to assess CAR T cell phenotype following antigen encounter, as occurs after cell infusion. We, therefore, present immunophenotypic and functional results for both processes throughout this report.

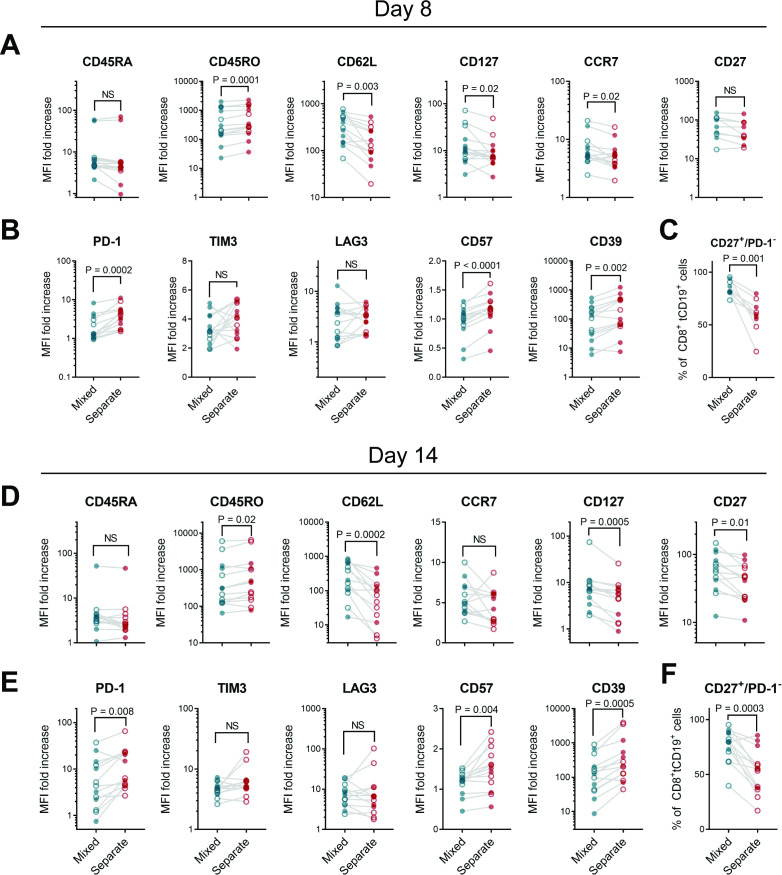

At both day 8 (without restimulation) or day 14 (following CD20+ restimulation), CD8+ CAR T cells cultured in the absence of CD4+ cells exhibited lower postexpansion levels of markers associated with memory and a less-differentiated state, and higher levels of exhaustion and terminal differentiation markers, compared with cocultured cells (figure 2A,B,D,E, online supplemental figure 6). CD19 CAR T cell products with a higher fraction of CD27+/PD-1– cells within the CD8+ T cell subset have been shown to yield clinical remissions more frequently in patients with CLL.6 We found that percentages of CD27+/PD-1– CD8+ cells were significantly increased in mixed CD4:CD8 cultures compared with CD8+ CAR T cells expanded separately (figure 2C,F). CD4+ CAR T cell immunophenotypes were largely similar regardless of the culture method (online supplemental figure 7). We observed a similar pattern of decreased memory markers and higher exhaustion markers among hCD19-BB-z CAR CD8+ T cells (online supplemental figure 8) and 1.5.3-NQ-28-z CAR T cells (online supplemental figure 9) from isolated cultures, indicating that these differences were not specific to CD20 CAR constructs, and were seen in CAR T cells across a variety of costimulatory domains (CD28-only, 4-1BB-only, or CD28-4-1BB).

Figure 2.

Phenotypic differences between CD8+ CAR T cells cultured alone or those cultured with CD4+ T cells. CD4+ or CD8+ enriched PBMC from healthy donors (filled circles) or patients (open circles) were stimulated, then either mixed at a 60:40 CD4:CD8 ratio or maintained in separate cultures, then transduced with 1.5.3-NQ-28-BB-z CD20 CAR lentiviral vector. (A–C) Cells were harvested on day 8 of cell culture without restimulation, or (D–F) restimulated with irradiated CD20+ LCL cells on day 7 and harvested on day 14. Markers of memory and differentiation (A, D), exhaustion (B, E), or percentage of CD27+ PD1─ cells (C, F) were measured by flow cytometry. Gating strategy and representative histograms are shown in online supplemental figure 6. Data represent the fold increase in geometric mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) over isotype control, gated on viable CD8+ tCD19+ CAR T cells at day 7 (n=14: 5 patients and 9 healthy donors for A, B and n=9: 4 patients and 5 healthy donors for (C) or at day 14 (n=13: 7 patients and 6 healthy donors). P values were determined using paired two-tailed t-tests for markers meeting criteria for normality based on D’Agostino and Pearson or Shapiro-Wilk tests, or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test for markers not meeting normality criteria. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; NS, not significant; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Hypofunctional phenotype of CD8+ CAR T cells expanded in absence of CD4+ cells

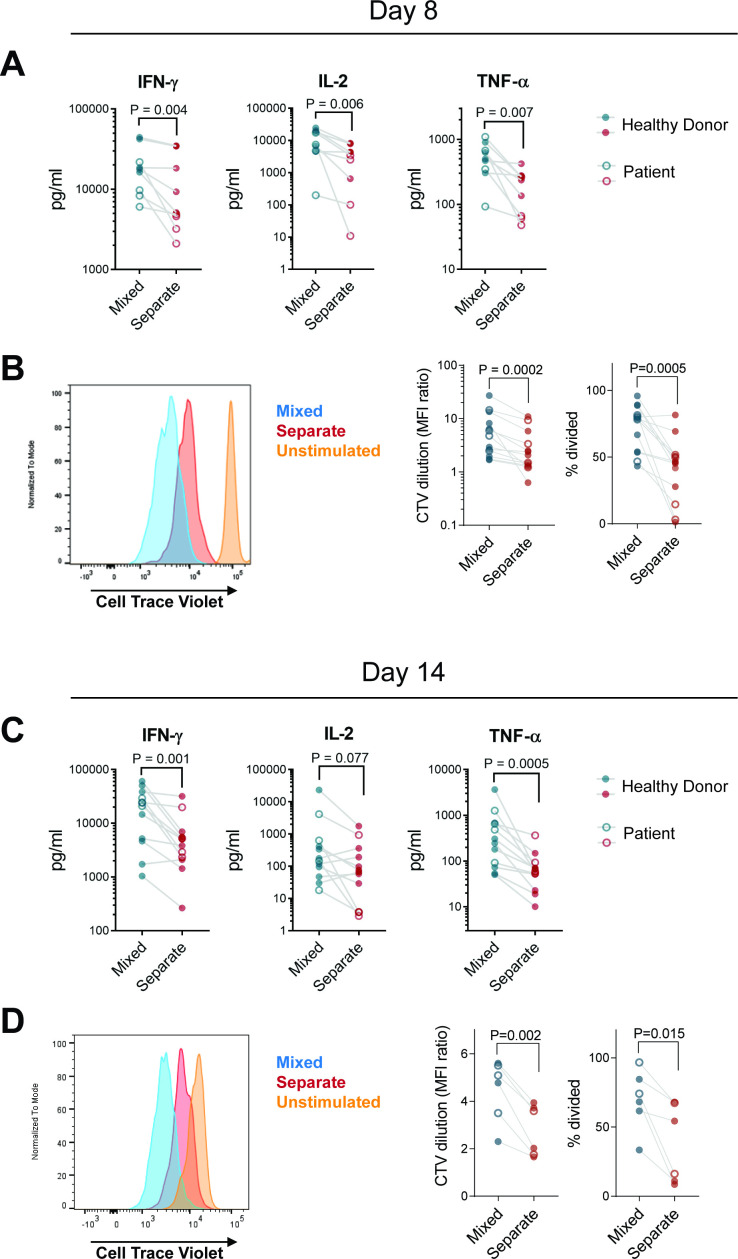

At both day 8 and day 14, FACS-sorted CD8+ CAR T cells (1.5.3-NQ-28-BB-z) cultured without CD4+ cells secreted significantly lower levels of IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α on stimulation with CD20+ Raji lymphoma cells than those expanded in mixed cultures (figure 3A,C). Likewise, proliferative capacity of CD8+ CAR T cells was lower when cultured without CD4+ cells (figure 3B,D). In contrast, cytokine secretion and proliferative capacity of CD4+ cells were minimally impacted regardless of culture method (online supplemental figure 10). The hCD19-BB-z and 1.5.3-NQ-28-z transduced cells similarly exhibited lower levels of cytokine secretion (though TNF-α for hCD19-BB-z and IFN-γ for 1.5.3-NQ-28-z did not reach statistical significance) and less proliferation in CD8+ CAR T cells cultured in the absence of CD4+ cells (online supplemental figures 11,12E,G). We also evaluated granzyme B secretion and cytotoxicity in second-generation CD20 CD8+ CAR T cells but found no differences between CD8+ CAR T cells expanded separately versus in CD4+ coculture (online supplemental figure 12F,H), indicating that these cells are not fully dysfunctional but retain cytotoxic function despite impaired cytokine secretion and proliferative capacity.

Figure 3.

CD8+ CAR T cells cultured in the absence of CD4+ cells have impaired cytokine secretion and proliferation in vitro. CD4+ and CD8+ enriched PBMC from patients (open circles) or healthy donors (filled circles) were stimulated, then either mixed at a 60:40 CD4:CD8 ratio or maintained in separate cultures, transduced with 1.5.3-NQ-28-BB-z CD20 CAR, and expanded. Cells were harvested on day 8 without restimulation (A, B) or restimulated with irradiated CD20+ LCL cells on day 7 and harvested on day 14 (C, D). FACS-sorted CD8+ tCD19+ T cells labeled with Cell Trace Violet (CTV) were incubated with irradiated CD20+ Raji-ffLuc cells (1:1 ratio). (A, C) supernatants were harvested at 24 hours and the indicated cytokines were measured by Luminex assay (n=9: 4 patients and 5 healthy donors for day 7; n=12: 4 patients and 8 healthy donors for day 14). (B, D) proliferation of the sorted cells after 4 days based on CTV dilution was assessed by flow cytometry. representative histograms are shown in the left panel, and summary data of geometric MFI ratio of unstimulated to stimulated cells and % divided cells are shown in the right panels (n=13: 4 patients and 9 healthy donors for day 7; n=6: 2 patients and 4 healthy donors for day 14). P values were determined using paired two-tailed t-tests for samples meeting criteria for normality based on D’Agostino and Pearson or Shapiro-Wilk normality test, or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed RANK test for samples not meeting normality criteria. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

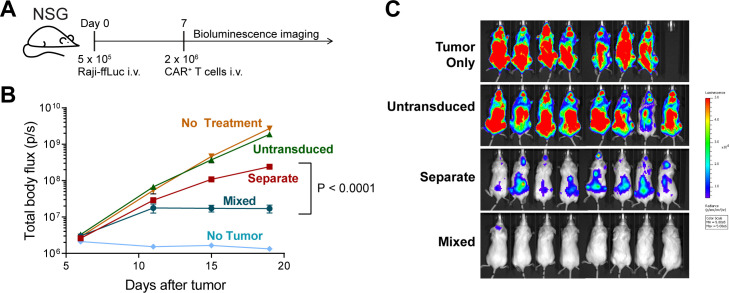

To evaluate the impact of separate versus mixed CD4+/CD8+ CAR T cell cultures on in vivo anti-lymphoma activity, we employed a CD20+ Raji mouse xenograft model, using suboptimal CAR T cell doses to distinguish differences in activity, since larger cell doses are curative using separate cell cultures infused at a 1:1 ratio.26 We found that mice treated with third-generation CD20 CAR T cell products manufactured in CD4+/CD8+ cocultures exhibited superior tumor control compared with mice treated with equivalent doses of CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cells expanded separately and infused at a 1:1 ratio (figure 4, online supplemental figure 13).

Figure 4.

Impact of mixed versus separate CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cell cultures on in vivo antitumor activity. NSG mice (n=8 per experimental group, n=5 for untransduced and no treatment groups, n=1 for no tumor group) bearing 7 day Raji-ffLuc tumors, received a suboptimal dose of 2×106 tCD19+ 1.5.3-NQ-28-BB-z CD20-targeted CAR T cells cultured at a 60:40 CD4:CD8 ratio or expanded in separate parallel CD4+ and CD8+ cultures and formulated at a 1:1 ratio prior to injection. The mixed cells were at a 1:1.9 CD4:CD8 ratio at the time of infusion. Untransduced T cells expanded in mixed cultures were included as a control. Mice were imaged twice weekly by bioluminescence imaging. (A) Experimental schema. (B) Average tumor burden per group over time as measured by total body bioluminescence. The mean luminescence values±SEM are shown. The tumor burden over time was greater in the separate group compared with the mixed group based on a two-way repeated measures ANOVA, time x treatment group, F (3, 42)=34.64, p<0.0001; time factor, F (1.158, 16.21)=40.05, p<0.0001; treatment group factor, F (1, 14)=37.24, p<0.0001. (The overall model including no treatment, untransduced, separate, and mixed groups showed: time x treatment group, F (9, 84)=21.49, p<0.0001; time factor, F (1.054, 29.51)=76.63, p<0.0001; treatment group factor, F (3, 28)=35.70, p<0.0001; for one mouse who died between day 15 and day 19 in the no-treatment group, the day 15 body flux value was carried forward as the day 19 value). (C) Dorsal images of each mouse at day 19 are shown. ANOVA, analysis of variance; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor.

Altered gene expression profiles of CD8+ cells expanded in absence of CD4+ help

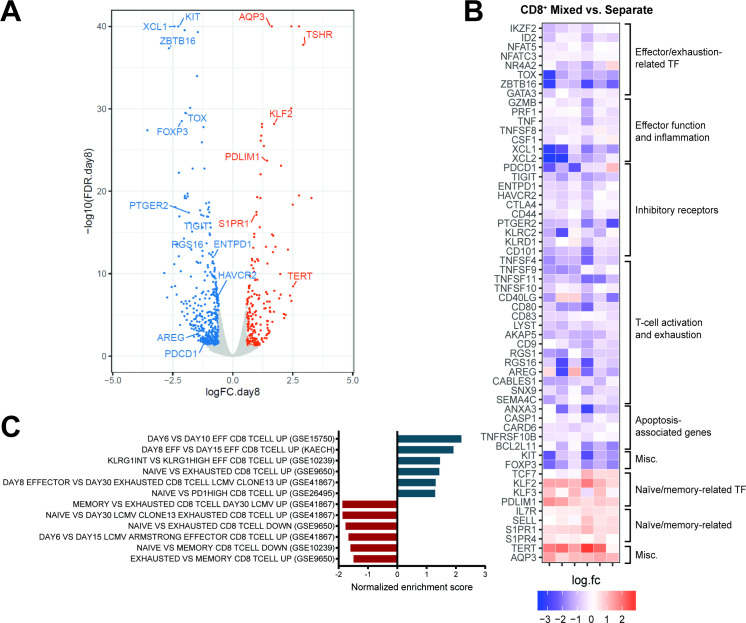

In view of the marked differences in ex vivo expansion, immunophenotype, and function between CD8+ cells from mixed versus separate cultures, we hypothesized that the hypofunctional phenotype of CD8+ CAR T cells generated in the absence of CD4+ help is driven by an altered transcriptional program. We, therefore, analyzed transcriptional profiles of FACS-sorted CD8+ CAR T cells expanded in mixed cultures with CD4+ cells compared with those in separate CD8-only cell cultures. At both day 8 of cell culture, and at day 14 (7 days after restimulation), there were large numbers of differentially expressed genes (false discovery rate<0.05 and fold change ≥1.5), indicating profoundly different gene expression patterns. At both timepoints, CD8+ CAR T cells cultured separately expressed significantly higher levels of genes associated with exhaustion and dysfunction, and lower levels of genes associated with memory formation compared with CD8+ cells expanded in cocultures. Differentially expressed genes were strongly correlated between day 8 and day 14 (figure 5A,B, online supplemental figure 14A–C and dataset S1). A broad array of costimulatory molecules and inhibitory receptors were upregulated in the separately cultured CD8+ cells, a characteristic of dysfunctional T cells.27 Full RNA-seq gene expression data from day 8 and day 14 are available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE245427, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE245427).28

Figure 5.

CD8+ CAR T cells cultured in presence or absence of CD4+ T cells exhibit distinct transcriptional signatures. Gene expression profiles of flow-sorted CD8+ tCD19+ 1.5.3-NQ-28-BB-z CAR T cells cultured either with CD4+ cells (“mixed”) or alone (“separate”) were evaluated by bulk RNA-seq on day 8 (n=6: 2 patients and 4 healthy donors). (A) Volcano plot of false discovery rate (FDR) (–log10) versus fold change (log2) showing differentially expressed genes between mixed versus separate CD8+ CAR T cells (FDR<0.05 and |log2FC|≥0.585 [≥1.5 fold change]), with upregulated and downregulated genes shown in orange and blue, respectively. (B) Heat map of fold change (log2) of selected genes (all with FDR<0.05) between mixed versus separate CD8+ CAR T cells in the 6 individual subjects. (C) Normalized enrichment scores from GSEA using selected gene sets related to CD8 naïve, memory, effector, and exhausted cells from the MSigDB C7 database, using the rankings of differential expression p values for all the genes. Positive/negative scores indicate enrichment of the gene sets in upregulated or downregulated genes when comparing mixed versus separate CD8+ CAR T cells. The FDR was ≤0.06 for all the gene sets shown here. GEO datasets are indicated in parentheses. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis;

jitc-2023-007803supp001.xlsx (137.9KB, xlsx)

We assessed which pathways were over-represented by the differentially expressed genes. At day 8, CD8+ CAR T cells expanded in the presence of CD4+ cells exhibited stronger TCR signaling, CD28 costimulation, and IFN-γ signaling, and lower levels of G-protein coupled receptor signaling and IL-10 signaling (online supplemental figure 15). At day 14 following restimulation, CD8+ cells from mixed cultures were distinguished primarily by upregulation of pathways associated with proliferation and cell cycle (online supplemental figure 14D). We also performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using the rankings of differential expression p values for all the genes. At day 8, consistent with our immunophenotypic findings, CD8+ CAR T cells from mixed cultures overexpressed genes that are upregulated in less differentiated CD8+ T cells (figure 5C). At day 14, the GSEA results were more heterogeneous, with mixed CD8+ T cells sharing upregulated genes with less differentiated cells from some gene sets and more differentiated or exhausted cells from other gene sets (online supplemental figure 14E), possibly reflecting the overlap of genes differentially expressed in both activated and exhausted states.

Mechanisms underlying improved CD8+ cell growth in CD4+ cocultures

Because cytokines impact CD8+ cell proliferation29 and promote expansion of naïve and/or memory T cells,30 we hypothesized that some of the observed differences between separate versus mixed CD8+ cells might be mediated by cytokines secreted by CD4+ cells. We measured the concentrations of several cytokines in CD4-only, CD8-only, or mixed cultures at early timepoints during cell culture (days 1 and 4) and found that mixed cultures had higher levels of IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, and IL-15 than CD8-only cultures at day 1, and higher levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-21 at day 4 (online supplemental figure 16).

We next performed experiments to evaluate the relative effects of soluble versus cell contact-dependent factors of CD4+ cells on CD8+ cells. Both-generation second and third-generation CD20-targeted CD8+ CAR T cells separated from CD4+ cells by a transwell insert exhibited inferior expansion to CD8+ cells in fully mixed cultures, but superior to CD8+ cells cultured in complete isolation (online supplemental figures 17A and 18A), suggesting that both cytokine-mediated and cell contact-dependent mechanisms contribute to ex vivo expansion. However, on antigen stimulation of CD8+ CAR T cells, improved proliferative capacity was only observed in fully mixed cultures, indicating that cell-cell contact was required (online supplemental figures 17B and 18B). The impact of soluble factors on cytokine secretion was less clear, with third generation CD8+ CAR T cells in transwell cultures demonstrating increased TNF-α and granzyme B, but not IL-2 or IFN-γ (online supplemental figure 17C,D) compared with cells in separate cultures, but no differences in cytokine secretion with second-generation CD8+ CAR T cells (online supplemental figure 18C,D).

With respect to immunophenotypic signatures, we evaluated the memory and exhaustion markers previously found to be significant between mixed versus separate CD8+ CAR T cells (figure 2A,B, online supplemental figure 9C,D) and found no significant difference in these markers between cells expanded in separate cultures or in transwell cultures for either second or third generation CD8+ CAR T cells (online supplemental figures 17E,F and 18E,F). Instead, differences were only observed between transwell and fully mixed cultures, indicating that soluble factors from CD4+ cells were not solely responsible for the observed phenotypic differences but rather that direct cell-cell contact was required. Cumulatively, these results suggested that although soluble factors from CD4+ cells contribute to superior CD8+ cell expansion ex vivo and possibly cytokine secretion, cell contact-dependent mechanisms are required for the improved function and less differentiated phenotype of CD8+ CAR T cells cultured with CD4+ cells.

In light of previous reports that activated CD8+ cells express CD40, and that CD40 ligation may provide a direct costimulatory signal independent of the well-known effects of CD40L on antigen-presenting cells (APCs),31–33 we hypothesized that the contact-dependent effect of CD4+ cells on CD8+ cells might be mediated through CD40L-CD40 interactions. We also hypothesized that given the improved outcomes reported in patients with higher levels of CD27+ cells,6 that CD70-CD27 interactions may also contribute. We first measured expression of these markers over time and found that in addition to the expected strong upregulation of CD40L on CD4+ cells on days 1–4, there was also a small but significant concurrent upregulation of CD40 on CD8+ cells (online supplemental figure 19). CD8+ cells also expressed robust levels of CD27, and both CD4+ and CD8+ cells expressed CD70, which was upregulated after activation, but present even on resting cells prior to stimulation.

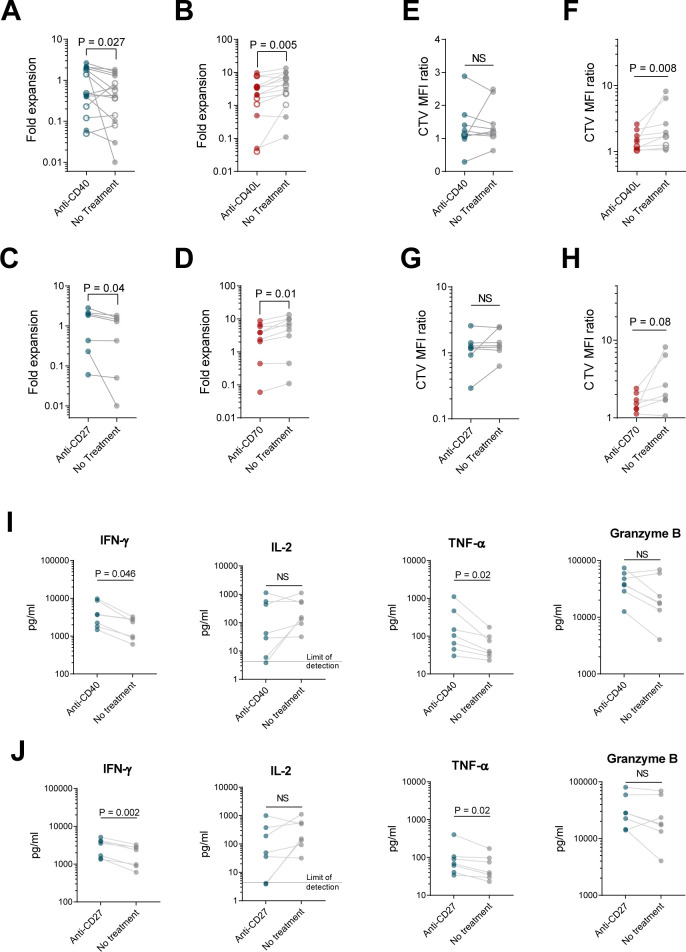

We then tested the impact of CD40 and CD27 signaling on ex vivo expansion, phenotype, and function, using antagonistic anti-CD40L or anti-CD70 antibodies in mixed CD4+/CD8+ cultures to block receptor-ligand interactions, or by using agonistic anti-CD40 or anti-CD27 antibodies in isolated CD8+ cultures. Anti-CD40L or anti-CD70 antibodies significantly impaired CD8+ CAR T cell expansion in mixed cultures, and agonistic CD40 or CD27 antibodies increased CD8+ cell expansion in separate cultures (figure 6A–D), suggesting that CD40 and CD27 signals contribute to improved CD8+ ex vivo expansion.

Figure 6.

CD4+ cells augment CD8+ T cell growth and function through both CD40L-CD40 and CD27-CD70 interactions. CD8+ cells from healthy donors (filled circles) or patients (open circles) were activated with αCD3/CD28 beads, cultured separately (A, C, E, G, I, J) or at a 60:40 ratio with CD4+ cells (B, D, F, H), transduced with 1.5.3-NQ-28-BB-z CD20 CAR lentivirus, and expanded in the presence of plate-bound agonistic anti-CD40 (A, E, I), plate-bound agonistic anti-CD27 antibody (C, G, J), soluble antagonistic anti-CD40L (B, F), or soluble antagonistic anti-CD70 antibody (D, H). (A–D) Fold expansion of CD8+ cells at day 8 is shown. (E–H) At day 8, cells were harvested, labeled with Cell Trace Violet (CTV), and restimulated with irradiated CD20+ Raji-ffLuc cells (1:1 ratio). Proliferation of the CD8+ cells after 4 days based on CTV dilution was measured by flow cytometry, with geometric MFI ratio of stimulated to unstimulated cells shown. (I–J) Supernatants from E, G were harvested 24 hours after restimulation, and levels of the indicated cytokines were measured by Luminex. Data represent mean values (±SEM). For (A), n=15 (6 patients and 9 healthy donors); for (B), n=14 (5 patients and 9 healthy donors); for (C), n=7 healthy donors; for (D), n=9 healthy donors; for (E, F, I), n=9 (2 patients and 7 healthy donors); for (G, H, J), n=7 healthy donors. P values were determined using paired two-tailed t-tests for samples meeting criteria for normality based on D’Agostino and Pearson or Shapiro-Wilk normality test, or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test for samples not meeting normality criteria. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; NS, not significant.

We found that neither blocking CD40L/CD40 or CD70/CD27 interactions between CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cells with antagonistic antibodies, nor treatment of CD8+ cells with agonistic anti-CD40 or anti-CD27, recapitulated the phenotypic changes observed between separate versus mixed-culture CD8+ cells (online supplemental figure 20). However, antagonistic anti-CD40L or anti-CD70 antibodies reduced the proliferative capacity of CD8+ CAR T cells in mixed cultures (figure 6F,H). Agonistic anti-CD40 or anti-CD27 antibodies did not impact proliferative capacity, IL-2 secretion, or granzyme B secretion of CD8+ CAR T cells but did increase IFN-γ and TNF-α secretion (figure 6E,G,I,J). Taken together, the data suggest that CD40 and CD27 signals on CD8+ CAR T cells received from CD40L and CD70 on CD4+ cells contribute to the improved ex vivo expansion and effector function observed in cocultured CD8+ CAR T cells but do not explain the less differentiated phenotype, which appears to require both soluble factors as well as direct cell contact with CD4+ cells.

Discussion

The various methods of T cell selection, activation, provision of supplemental cytokines, and culture duration currently used in CAR T cell manufacturing likely impact T cell function,6–9 16 17 34–36 but the optimal conditions are not known. T-cell enrichment avoids the deleterious effects of contaminating myeloid cell subsets and minimizes the risk of transducing circulating tumor cells that can occur with unselected PBMC.11 12 15 Infusion of CAR T cells at a defined CD4:CD8 ratio leads to superior outcomes in preclinical studies compared with products generated from unselected PBMC,16 17 and while no direct comparisons have been made in human clinical trials, CAR products with defined 1:1 ratios compare favorably with those generated from unselected PBMC.1 2 4 However, the need to generate, maintain, and qualify two separate cultures for each patient adds cost and complexity to the manufacturing process and increases the risk of a nonconforming product.

In this study, we evaluated whether CAR T cell manufacturing could be improved by combining CD4+ and CD8+ cell at a defined ratio at the initiation of cell cultures. It is well established that, in vivo, CD4+ cells play an important role in CD8+ T cell priming, memory formation and maintenance, effector differentiation, and sustaining functionality during chronic antigen exposure,32 37–40 and that these effects are primarily mediated through APCs. However, the direct impact of CD4+ cells on CD8+ cells during ex vivo CAR T cell culture, which does not depend on APCs, has not been well characterized. Our results reveal that CD4+ coculture with CD8+ cells markedly enhances not only CD8+ cell ex vivo expansion, but also phenotype and function. CD8+ cells cultured in the absence of CD4+ cells have a more exhausted phenotype, correlating with inferior in vitro proliferation, cytokine secretion, and in vivo antitumor activity. Importantly, these findings were reproducible across a variety of types of CAR constructs.

The observed phenotypic and functional differences were driven by distinct transcriptional programs. CD8+ cells cultured alone expressed lower levels of genes associated with memory formation and higher levels of genes associated with exhaustion and terminal differentiation. Cocultured CD8+ cells, by contrast, had an early effector phenotype consistent with their superior in vitro and in vivo function. These differential gene expression patterns persisted following restimulation with target cells, suggesting that formation of the hypofunctional transcriptional program is durable and occurs early during cell culture. The results of the mouse experiments, in which equal numbers of CD4+ cells were infused along with the CD8+ cells, further suggest that the hypofunctional phenotype is epigenetically imprinted during cell manufacturing and is not rescued by the provision of CD4+ help at the time of infusion, but future studies are needed to evaluate this possibility. Despite their diminished capacity for cytokine secretion and proliferation, CD8+ cells cultured in isolation retained at least short-term cytotoxic function, consistent with a terminal effector phenotype rather than one that is fully dysfunctional.

The impact of CD4+ cells on CD8+ cells in culture was mediated through both soluble factors and contact-dependent mechanisms. In CD8+ cell cultures containing CD4+ cells, we observed higher levels of cytokines known to improve CD8+ T cell proliferation and promotion of a memory phenotype, including IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, IL-15, and IL-21, suggesting that cytokines contributed to the distinct CD8+ cell phenotypes in mixed cultures. However, direct contact between CD4+ and CD8+ cells was required for full preservation of CD8+ cell functionality, which was mediated, at least in part, through both CD40L-CD40 and CD70-CD27 interactions. Because CD40L and CD70 expressed on CD8+ cells were insufficient to provide an adequate costimulatory signal in isolated CD8+ cultures, we postulate that these signals come from activated CD4+ cells.

CD40L, which is primarily observed on activated CD4+ cells, is transiently expressed and engages its cognate receptor, CD40, on various immune cells to help propagate antigen-specific immune responses. The critical signals provided by CD4+ cells in vivo during CD8+ T cell priming and memory development23 38 41 depend in large part on CD40L-CD40 interactions, through licensing of cognate APCs.23 42 However, CD40 is also expressed at low levels on activated T cells and can play a costimulatory role.32 33 43 Indeed, direct CD40L-CD40 interactions between CD4+ and CD8+ cells can enhance memory function in CD8+ cells, independent of CD40 on APCs.32 Our data suggest that CD40 ligation on CD8+ CAR T cells by CD40L on CD4+ cells provides an important costimulatory signal that, together with soluble factors from CD4+ cells, increases ex vivo expansion and contributes to a more functional phenotype.

This costimulatory role of CD40 in CD8+ cells appears to be important primarily in non-infectious settings or under conditions in which T cells receive suboptimal activation signals.43 Other studies conducted in the setting of infection show that CD40 is not required for normal T cell function and memory formation in CD8+ cells, perhaps because in a state of inflammation, other signals bypass the requirement for CD40 signaling.44 45 Thus, a costimulatory role for CD40 on CD8+ cells may be limited to sterile conditions such as cell culture, where additional inflammatory cues are lacking. It is also possible that the need for CD4+ help in CD8+ cell cultures could be overcome through the provision of optimal combinations of exogenous cytokines.

CD27 is a costimulatory receptor expressed by naïve CD8+ cells that is important for T cell memory, antitumor responses, and resistance to apoptosis.46–49 The ligand for CD27 is CD70, which is transiently expressed on activated B and T cells as well as mature dendritic cells, and was confirmed to be expressed on CD4+ and CD8+ cells in our CAR T cell cultures. Our results suggest that CD27 signaling in CD8+ cells following ligation with CD70 from CD4+ cells contributes to improved ex vivo expansion and effector function.

Our experiments isolating the impact of soluble factors from CD4+ cells, or CD40L-CD40 or CD70-CD27 interactions, did not recapitulate the memory-like immunophenotype of cocultured CD8+ cells. This suggests that the less differentiated transcriptional program is preserved either through integrated signals from some combination of cytokines, CD40, and CD27, or through as-yet unidentified ligand-receptor interactions between CD4+ and CD8+ cells.

Our findings help to inform the design of CAR T cell manufacturing processes, for which the optimal conditions remain undefined. Starting with unselected PBMC is expedient but has drawbacks as previously discussed. Infusing a defined CD4:CD8 ratio may have advantages but is more cumbersome, expensive, and, as our data suggest, may yield CD8+ cells that could be further functionally improved through CD4+ coculture. We recognize that a limitation of our study is that we did not compare products generated from selected but unfractionated T cells with those generated from defined CD4:CD8 ratios at culture initiation. We did not include unselected T cells as a control since the goal of the project was to optimize our own process rather than compare all existing methods. However, in addition to the aforementioned advantages of T cell selection, it is also uncertain whether the same beneficial effect of CD4+ cells on CD8+ cells would occur in products generated from patients with very low CD4+ cell fractions; starting at a defined ratio ensures that adequate numbers of CD4+ cells are present to support optimal CD8+ cell function.

In summary, our data provide insights into the biology of CD8+ CAR T cells that should be considered when designing a CAR T cell production platform. We found that CD8+ CAR T cells cultured in the absence of CD4+ cells or cytokines other than IL-2 acquire a hypofunctional phenotype driven by a distinct transcriptional program that persists after restimulation with target antigen and is not rescued by CD4+ cells at the time of cell infusion. Coculture of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in a defined ratio at culture initiation bypasses these problems, and we demonstrate that the salutary effects of the CD4+ cells are mediated by both cytokines and contact-dependent mechanisms, including CD40L-CD40 and CD70-CD27 interactions. CD8+ CAR T cells cultured with CD4+ cells exhibit superior ex vivo expansion, facilitating shorter culture times, and a final CD4:CD8 ratio in the cell product that is proportional to the ratio at culture initiation. Based on these results, we have modified the cell manufacturing process in our ongoing clinical trial, with promising preliminary activity associated with this change.21 22

Methods

Culturing of CAR T cells using various CD4:CD8 ratios

PBMCs were obtained by apheresis from healthy donors or patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell lymphomas. For healthy donors, PBMCs were enriched for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by positive selection with CliniMACS beads (Miltenyi), cryopreserved, and thawed 1 day prior to the planned experiment. Cryopreserved patient apheresis products were thawed 1 day prior to the planned experiment, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were positively and negatively selected, respectively, using EasySep immunomagnetic selection (Stemcell Technologies) on the day of stimulation.

On day 0 of culture, selected CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were washed, activated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads at a 3:1 bead:cell ratio, and then mixed (or not) to generate the various CD4:CD8 ratios shown in the figures. Cultures were established at a total cell number of 1×106 cells/well in 24-well tissue culture plates and cultured in T-cell culture medium (RPMI1640 media with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% L-glutamine, and 50 IU/mL rhIL-2 (Stemcell Technologies)). One day following stimulation, T cells were transduced by centrifugation at 2100 rpm for 60 min at 32°C with concentrated lentiviral supernatant encoding third-generation 1.5.3-NQ-28-BB-z anti-CD20 CAR,26 second-generation 1.5.3-NQ-28-z CAR,26 fully human CD19-BB-z CAR (hCD19-BB-z),50 or empty vector,26 supplemented with polybrene (5 µg/mL). On day 4, magnetic beads were removed.

In some experiments, cells were restimulated at day 7 by coculturing with irradiated CD20+ lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL) cells at a 1:1 ratio of LCL to T cells, and further expanded until harvest at day 14 or 15. In other experiments, cells were harvested at day 8 or 9 without an LCL restimulation step. For cells manufactured with the 14–15 days process, cells were counted at day 7 prior to restimulation and at days 14–15, and with the non-restimulation process, cells were counted at days 8 or 9. At the same time points for counting, cells were also evaluated for immunophenotype, transcriptional profile, and function as described in more detail below and in online supplemental methods.

Cytokine production and proliferation

Truncated CD19+ (tCD19+) CD4+ and tCD19+ CD8+ T cells were sorted from CD20 CAR vector-transduced T cell cultures at 8 or 14 days after culture initiation, and stimulated with irradiated CD20 expressing Raji-ffLuc cells at a 1:1 stimulator to responder ratio. After 24 hours of coculture, supernatants were harvested. Cytokine levels were also measured in culture supernatants from stimulated and transduced CD4-only, CD8-only, and 70:30 CD4:CD8 mixed CAR T cell cultures at early time points (days 1, 4), with supernatants collected before media change. Levels of secreted IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ were quantified from supernatants using a Luminex microbead sandwich immunoassay. Assays were read on a Luminex 200 instrument (Millipore) and analyzed with Luminex xPonent software (V.4.3, V.4.2, or V.3.1). To investigate cell proliferation, sorted cells were labeled with 5 µmol/L CellTrace Violet (CTV) (Molecular Probes, ThermoFisher) and stimulated with irradiated CD20 expressing Raji-ffLuc cells for 96 hours. Dye dilution of CTV-labeled cells was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Transwell cell culture experiments

CD8+ and CD4+ cells were isolated by immunomagnetic selection, activated, and expanded either as separate CD4+ and CD8+ cell cultures of 1×106 cells each, or a mixed 60:40 CD4:CD8 cell culture. Cells were transduced with 1.5.3-NQ-28-BB-z anti-CD20 CAR lentivirus 1 day after bead stimulation. For the transwell group, immediately following T cell transduction, 0.6×106 CD4+ cells were plated to the lower compartment of 24 well plate, and 0.4×106 CD8+ cells were placed in an upper transwell compartment (Corning). The cells were scaled up to 12-well transwell plates as needed when cell density increased. At day 7, cells were harvested, counted, and evaluated by flow cytometry for expression of CD4, CD8, and tCD19. Proliferation, cytokine secretion, and phenotype were also assessed using the methods described above.

Online supplemental methods include flow cytometry, cytotoxicity, RNA-seq, evaluations of CD40L-CD40 and CD70-CD27 interactions, and in vivo experiments.

Statistics

Statistical comparisons of two experimental groups were made using GraphPad Prism software, using two-tailed paired t-tests for datasets meeting normality criteria by Shapiro-Wilk or D’Agostino-Pearson testing, and Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests for paired data not meeting normality criteria. For comparisons of tumor burden over time between treatment groups in the mouse experiments, we used a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance. For all comparisons, values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Footnotes

SYL and DHL contributed equally.

Contributors: SYL and DHL designed and performed all experiments and analyzed data. SYL also contributed to writing the manuscript. WS, FW, RSB and SL analyzed the gene expression data. FC-C performed experiments and analyzed data. HRM generated the CD19 CAR construct. RR provided subject cells and analyzed data. SO’S, DJG and MS analyzed data. BT designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. SYL and BGT are guarantors of the data. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by funding from: Kleberg Foundation, Fred Hutch Gala, Fred Hutch IIRC, NIH R01 CA230520, NIH R01 CA076287, Mustang Bio, Shared Resources of the Fred Hutch/University of Washington Cancer Consortium (P30 CA015704).

Competing interests: BT has licensed intellectual property to and collected royalties from Mustang Bio; has received research funding from Mustang Bio and Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS)/Juno Therapeutics; and has served as an advisor for Mustang Bio and Proteios Technology. DJG has received research funding, has served as an advisor and has received royalties from BMS/Juno Therapeutics; has served as an advisor and received research funding from Seattle Genetics; has served as an advisor for GlaxoSmithKline, Celgene, Janssen Biotech, and Legend Biotech; and has received research funding from SpringWorks Therapeutics, Sanofi, Cellectar Biosciences, and Neoleukin Therapeutics. MS has received research funding from Mustang Bio, BMS, Pharmacyclics, Genentech, AbbVie, TG Therapeutics, BeiGene, AstraZeneca, Genmab, MorphoSys/Incyte, Vincerx and has consulted for AbbVie, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Pharmacyclics, BeiGene, BMS, MorphoSys/Incyte, Kite, Eli Lilly, Mustang Bio, Regeneron, ADC therapeutics, Fate Therapeutics and MEI Pharma.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. All data associated with this study are present in the paper or online supplemental materials available with the online version of this article. The RNA-seq data are accessible on a public depository (accession number GSE245427), which can be found on the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE245427. For other original data, please contact tillb@fredhutch.org.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center IRB #3942 and #9738. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell Lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. Lancet 2020;396:839–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31366-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, et al. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:31–42. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30864-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2018;378:439–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2019;380:45–56. 10.1056/NEJMoa1804980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raje N, Berdeja J, Lin Y, et al. Anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy bb2121 in Relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1726–37. 10.1056/NEJMoa1817226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraietta JA, Lacey SF, Orlando EJ, et al. Determinants of response and resistance to CD19 Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Med 2018;24:563–71. 10.1038/s41591-018-0010-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finney OC, Brakke HM, Rawlings-Rhea S, et al. CD19 CAR T cell product and disease attributes predict leukemia remission durability. J Clin Invest 2019;129:2123–32. 10.1172/JCI125423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Locke FL, Rossi JM, Neelapu SS, et al. Tumor burden, inflammation, and product attributes determine outcomes of axicabtagene ciloleucel in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv 2020;4:4898–911. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monfrini C, Stella F, Aragona V, et al. Phenotypic composition of commercial anti-CD19 CAR T cells affects in vivo expansion and disease response in patients with large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2022;28:3378–86. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-0164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elavia N, Panch SR, McManus A, et al. Effects of starting cellular material composition on chimeric antigen receptor T-cell expansion and characteristics. Transfusion 2019;59:1755–64. 10.1111/trf.15287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stroncek DF, Ren J, Lee DW, et al. Myeloid cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cell concentrates inhibit the expansion of chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Cytotherapy 2016;18:893–901. 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah NN, Highfill SL, Shalabi H, et al. CD4/CD8 T-cell selection affects chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell potency and toxicity: updated results from a phase I anti-CD22 CAR T-cell trial. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:1938–50. 10.1200/JCO.19.03279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stroncek DF, Lee DW, Ren J, et al. Elutriated lymphocytes for manufacturing chimeric antigen receptor T cells. J Transl Med 2017;15:59. 10.1186/s12967-017-1160-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noaks E, Peticone C, Kotsopoulou E, et al. Enriching leukapheresis improves T cell activation and transduction efficiency during CAR T processing. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2021;20:675–87. 10.1016/j.omtm.2021.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruella M, Xu J, Barrett DM, et al. Induction of resistance to chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy by transduction of a single leukemic B cell. Nat Med 2018;24:1499–503. 10.1038/s41591-018-0201-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sommermeyer D, Hudecek M, Kosasih PL, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells derived from defined CD8(+) and CD4(+) subsets confer superior antitumor reactivity in vivo. Leukemia 2016;30:492–500. 10.1038/leu.2015.247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moeller M, Haynes NM, Kershaw MH, et al. Adoptive transfer of gene-engineered CD4+ helper T cells induces potent primary and secondary tumor rejection. Blood 2005;106:2995–3003. 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cartron G, Fox CP, Liu FF, et al. Matching-adjusted indirect treatment comparison of Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies for third-line or later treatment of Relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma: Lisocabtagene Maraleucel versus Tisagenlecleucel. Exp Hematol Oncol 2022;11:17. 10.1186/s40164-022-00268-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bishop MR, Dickinson M, Purtill D, et al. Second-line tisagenlecleucel or standard care in aggressive B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2022;386:629–39. 10.1056/NEJMoa2116596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamdar M, Solomon SR, Arnason J, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel versus standard of care with salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation as second-line treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (TRANSFORM): results from an interim analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2022;399:2294–308. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00662-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shadman M, Yeung C, Redman MW, et al. Third generation CD20 targeted CAR T-cell therapy (MB-106) for treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2020;136(Supplement 1):38–9. 10.1182/blood-2020-136440 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shadman M, Yeung CC, Redman M, et al. High efficacy and low toxicity of MB-106, a third generation CD20 targeted CAR-T for treatment of relapsed/refractory B-NHL and CLL. Transplantation and Cellular Therapy 2022;28:S182–3. 10.1016/S2666-6367(22)00386-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett SRM, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, et al. Induction of a CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte response by cross-priming requires cognate CD4+ T cell help. J Exp Med 1997;186:65–70. 10.1084/jem.186.1.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carvalho LH, Sano G-I, Hafalla JCR, et al. IL-4-Secreting CD4+ T cells are crucial to the development of CD8+ T-cell responses against malaria liver stages. Nat Med 2002;8:166–70. 10.1038/nm0202-166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J-CE, Livingstone AM. Cutting edge: CD4+ T cell help can be essential for primary CD8+ T cell responses in vivo. J Immunol 2003;171:6339–43. 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SY, Olsen P, Lee DH, et al. Preclinical optimization of a CD20-specific chimeric antigen receptor vector and culture conditions. J Immunother 2018;41:19–31. 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams JB, Horton BL, Zheng Y, et al. The Egr2 targets LAG-3 and 4-1BB describe and regulate dysfunctional antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment. J Exp Med 2017;214:381–400. 10.1084/jem.20160485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SY. CD8+ chimeric antigen receptor T cells manufactured in absence of CD4+ cells exhibit hypofunctional phenotype. NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus Repository 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butler MO, Imataki O, Yamashita Y, et al. Ex vivo expansion of human CD8+ T cells using autologous CD4+ T cell help. PLoS One 2012;7:e30229. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rochman Y, Spolski R, Leonard WJ. New insights into the regulation of T cells by gamma(c) family cytokines. Nat Rev Immunol 2009;9:480–90. 10.1038/nri2580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armitage RJ, Tough TW, Macduff BM, et al. CD40 ligand is a T cell growth factor. Eur J Immunol 1993;23:2326–31. 10.1002/eji.1830230941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bourgeois C, Rocha B, Tanchot C. A role for CD40 expression on CD8+ T cells in the generation of CD8+ T cell memory. Science 2002;297:2060–3. 10.1126/science.1072615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munroe ME, Bishop GA. A costimulatory function for T cell CD40. J Immunol 2007;178:671–82. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghassemi S, Nunez-Cruz S, O’Connor RS, et al. Reducing ex vivo culture improves the anti-leukemic activity of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells. Cancer Immunol Res 2018;6:1100–9. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Yee C. IL-21 mediated Foxp3 suppression leads to enhanced generation of antigen-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Blood 2008;111:229–35. 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Y, Zhang M, Ramos CA, et al. Closely related T-memory stem cells correlate with in vivo expansion of CAR.CD19-T cells and are preserved by IL-7 and IL-15. Blood 2014;123:3750–9. 10.1182/blood-2014-01-552174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahrends T, Spanjaard A, Pilzecker B, et al. CD4+ T cell help confers a cytotoxic T cell effector program including coinhibitory receptor downregulation and increased tissue invasiveness. Immunity 2017;47:848–61. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janssen EM, Lemmens EE, Wolfe T, et al. CD4+ T cells are required for secondary expansion and memory in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Nature 2003;421:852–6. 10.1038/nature01441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith CM, Wilson NS, Waithman J, et al. Cognate CD4(+) T cell licensing of dendritic cells in CD8(+) T cell immunity. Nat Immunol 2004;5:1143–8. 10.1038/ni1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zander R, Schauder D, Xin G, et al. CD4(+) T cell help is required for the formation of a cytolytic CD8(+) T cell subset that protects against chronic infection and cancer. Immunity 2019;51:1028–1042. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borrow P, Tishon A, Lee S, et al. CD40L-deficient mice show deficits in antiviral immunity and have an impaired memory CD8+ CTL response. J Exp Med 1996;183:2129–42. 10.1084/jem.183.5.2129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bennett SRM, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, et al. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature 1998;393:478–80. 10.1038/30996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fanslow WC, Clifford KN, Seaman M, et al. Recombinant CD40 ligand exerts potent biologic effects on T cells. J Immunol 1994;152:4262–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee BO, Hartson L, Randall TD. CD40-deficient, influenza-specific CD8 memory T cells develop and function normally in a CD40-sufficient environment. J Exp Med 2003;198:1759–64. 10.1084/jem.20031440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun JC, Bevan MJ. Cutting edge: long-lived CD8 memory and protective immunity in the absence of CD40 expression on CD8 T cells. J Immunol 2004;172:3385–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hendriks J, Gravestein LA, Tesselaar K, et al. CD27 is required for generation and long-term maintenance of T cell immunity. Nat Immunol 2000;1:433–40. 10.1038/80877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang J, Kerstann KW, Ahmadzadeh M, et al. Modulation by IL-2 of CD70 and CD27 expression on CD8+ T cells: importance for the therapeutic effectiveness of cell transfer Immunotherapy. J Immunol 2006;176:7726–35. 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keller AM, Xiao Y, Peperzak V, et al. Costimulatory ligand CD70 allows induction of CD8+ T-cell immunity by immature dendritic cells in a vaccination setting. Blood 2009;113:5167–75. 10.1182/blood-2008-03-148007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ochsenbein AF, Riddell SR, Brown M, et al. CD27 expression promotes long-term survival of functional effector-memory CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in HIV-infected patients. J Exp Med 2004;200:1407–17. 10.1084/jem.20040717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mirzaei HR, Jamali A, Jafarzadeh L, et al. Construction and functional characterization of a fully human anti-CD19 Chimeric antigen receptor (huCAR)-Expressing primary human T cells. J Cell Physiol 2019;234:9207–15. 10.1002/jcp.27599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2023-007803supp002.pdf (21MB, pdf)

jitc-2023-007803supp001.xlsx (137.9KB, xlsx)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. All data associated with this study are present in the paper or online supplemental materials available with the online version of this article. The RNA-seq data are accessible on a public depository (accession number GSE245427), which can be found on the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE245427. For other original data, please contact tillb@fredhutch.org.